FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Tomvald v Toll Transport Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1208

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to file and serve within fourteen days a table setting forth either:

(i) an agreed quantum of compensation to be payable to Mr Tomvald;

or, in the event of a failure to agree:

(ii) a table setting forth the matters upon which there is disagreement and the reasons for any disagreement.

2. Subject to Order 1, the parties are to bring in Short Minutes of Orders to give effect to these reasons within fourteen days.

3. Liberty is reserved to either party to have the matter re-listed on 48 hours’ notice in writing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 In August 2016 Mr Joshua Tomvald filed in this Court an Originating Application and Statement of Claim. The First Respondent was named as Toll Transport Pty Ltd (“Toll Transport”). The Second and Third Respondents were named as Mr Adam Jones and Ms Tamara Green respectively, but the proceedings against the Second and Third Respondents were discontinued.

2 Mr Tomvald is a 26 year old freight handler.

3 The identity of his employer has changed over time. As from 2007 it would appear that he was initially employed by Toll Personnel Pty Ltd. That company traded as “Toll People”. In October 2012 he was offered “an appointment as a Freight Handler on a casual basis with Toll Pty Ltd … one of the Toll Group of companies”. By letter dated 26 May 2015 Mr Tomvald was, however, notified of “a proposed change to [his] employer company”. As at that date, the letter notifying him of the proposed change identified his current employer as Toll Ipec Pty Ltd. The same letter informed him that from 1 July 2015, his employer company would become “Toll Transport Pty Limited … the group’s primary operating entity in Australia”.

4 Although the precise identity of his employer may well have changed over time, the fact remains that he has been employed by one or other of the Toll Group of companies as a freight handler for a period of almost a decade.

5 In April 2016 Mr Tomvald approached Toll Transport and sought to convert his position as a casual employee to a permanent position. He claimed an entitlement to a permanent position employed for 38 hours per week. Toll Transport offered him a permanent part-time position for only 30 hours per week.

6 That offer was not acceptable to Mr Tomvald. He commenced this proceeding. He claims (inter alia) that he has a right to convert from casual employment to permanent employment on a “like for like” basis. Previously he worked Monday to Friday commencing normally at 4.00am and generally did an 8 hour shift. He wants a like position on a permanent basis. He also claims that Toll Transport have contravened a number of provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”). In all, nine contraventions are alleged. Mr Tomvald seeks declaratory relief, compensation and orders for the imposition of penalties with any penalties to be payable to Mr Tomvald.

7 It has been concluded that contraventions 2, 5, 6, 7 and 9 have been made out.

8 A Notice of Cross-Claim filed in November 2016 by Toll Transport, it has been further concluded, falls away and need not be considered given the conclusion that Mr Tomvald was not a permanent employee but remained a casual employee. The Cross-Claim was filed to cover the position that may have emerged had it been concluded that Mr Tomvald was a permanent employee and had therefore received additional payments only payable to a casual employee. That Cross-Claim sought (inter alia) the recovery of those overpayments said to have been made to Mr Tomvald for the period from 22 October 2012 up to the present, together with interest.

9 It should be noted at the outset that the pleadings in the present matter whereby the competing claims for relief were advanced for resolution did not proceed smoothly. The initial Statement of Claim was filed on 4 August 2016. Leave was granted to file an Amended Statement of Claim on 15 November 2016. One of the amendments then effected was to claim declaratory relief as to Mr Tomvald having been employed on a permanent basis by Toll Transport as from October 2012. The date such employment was said to have commenced assumed relevance: it affected both the Enterprise Agreement which covered his employment; and it occasioned Toll Transport to file its Cross-Claim seeking the recovery of moneys paid to Mr Tomvald in excess of that to which he was entitled if he was in fact a permanent employee.

10 The hearing commenced on 28 November 2016. But it then emerged for the first time that Mr Tomvald had been employed by a number of Toll related companies over the years and had only been employed by Toll Transport as from 1 July 2015. Both the Statement of Claim and Amended Statement of Claim had identified the wrong entity as the employer for periods prior to 1 July 2015. Such fundamental errors should not have occurred. A Further Amended Statement of Claim was filed on the third day of the hearing.

THE FAIR WORK ACT

11 Although it is necessary to subsequently refer to other provisions of the Fair Work Act, those provisions which assume central relevance are ss 50, 340, 341, 345, 360, 361, 545 and 546.

12 The text of each of these provisions assumes relevance, as does the question as to the need for Mr Tomvald to discharge the onus of proof imposed upon him and potentially the onus placed upon Toll Transport to discharge the onus of proof imposed upon it, assuming s 361 applies.

13 Section 50 provides as follows:

Contravening an enterprise agreement

A person must not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement.

14 Sections 340, 341, 345, 360 and 361 all appear in Pt 3-1 of the Fair Work Act, which is headed “General protections”. Section 340 provides as follows:

Protection

(1) A person must not take adverse action against another person:

(a) because the other person:

(i) has a workplace right; or

(ii) has, or has not, exercised a workplace right; or

(iii) proposes or proposes not to, or has at any time proposed or proposed not to, exercise a workplace right; or

(b) to prevent the exercise of a workplace right by the other person.

(2) A person must not take adverse action against another person (the second person) because a third person has exercised, or proposes or has at any time proposed to exercise, a workplace right for the second person’s benefit, or for the benefit of a class of persons to which the second person belongs.

Section 341(1) defines a “workplace right” as follows:

Meaning of workplace right

(1) A person has a workplace right if the person:

(a) is entitled to the benefit of, or has a role or responsibility under, a workplace law, workplace instrument or order made by an industrial body; or

(b) is able to initiate, or participate in, a process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument; or

(c) is able to make a complaint or inquiry:

(i) to a person or body having the capacity under a workplace law to seek compliance with that law or a workplace instrument; or

(ii) if the person is an employee—in relation to his or her employment.

15 Section 345 provides as follows:

Misrepresentations

(1) A person must not knowingly or recklessly make a false or misleading representation about:

(a) the workplace rights of another person; or

(b) the exercise, or the effect of the exercise, of a workplace right by another person.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply if the person to whom the representation is made would not be expected to rely on it.

16 Sections 360 and 361 of the Fair Work Act are directed to the question of proof that a person takes action “for a particular reason” or “with a particular intent” – as is the case in respect to contraventions of ss 343 and 355. Section 360 provides as follows:

Multiple reasons for action

For the purposes of this Part, a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason.

Section 361 is the “reverse onus of proof” provision and is as follows:

Reason for action to be presumed unless proved otherwise

(1) If:

(a) in an application in relation to a contravention of this Part, it is alleged that a person took, or is taking, action for a particular reason or with a particular intent; and

(b) taking that action for that reason or with that intent would constitute a contravention of this Part;

it is presumed that the action was, or is being, taken for that reason or with that intent, unless the person proves otherwise.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply in relation to orders for an interim injunction.

17 Section 535 of the Fair Work Act provides as follows:

Employer obligations in relation to employee records

(1) An employer must make, and keep for 7 years, employee records of the kind prescribed by the regulations in relation to each of its employees.

(2) The records must:

(a) if a form is prescribed by the regulations—be in that form; and

(b) include any information prescribed by the regulations.

(3) The regulations may provide for the inspection of those records.

18 Section 545 of the Fair Work Act provides in relevant part as follows:

Orders that can be made by particular courts

Federal Court and Federal Circuit Court

(1) The Federal Court … may make any order the court considers appropriate if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened, or proposes to contravene, a civil remedy provision.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), orders the Federal Court … may make include the following:

(a) an order granting an injunction, or interim injunction, to prevent, stop or remedy the effects of a contravention;

(b) an order awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention;

(c) an order for reinstatement of a person.

19 Section 546 provides in relevant part as follows:

Pecuniary penalty orders

(1) The Federal Court … may, on application, order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate if the court is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil remedy provision.

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(2) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is an individual—the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2); or

(b) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2).

Payment of penalty

(3) The court may order that the pecuniary penalty, or a part of the penalty, be paid to:

(a) the Commonwealth; or

(b) a particular organisation; or

(c) a particular person.

Mr Tomvald’s onus of proof

20 At least two questions arise in respect to the onus of proof imposed upon Mr Tomvald.

21 First, an allegation that an employer has contravened a “civil remedy provision” of the Fair Work Act is an allegation as to “quasi-criminal” conduct: e.g., Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (No 3) [2002] FCA 1294 at [53], (2002) ATPR ¶41-901 at 45,414 per Goldberg J; BHP Coal Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2013] FCA 1291 at [68] to [69], (2013) 239 IR 363 at 388 to 389 per Collier J. Due regard must thus be had to the gravity of the allegations being made. In that context, s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) provides as follows:

Civil proceedings: standard of proof

(1) In a civil proceeding, the court must find the case of a party proved if it is satisfied that the case has been proved on the balance of probabilities.

(2) Without limiting the matters that the court may take into account in deciding whether it is so satisfied, it is to take into account:

(a) the nature of the cause of action or defence; and

(b) the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding; and

(c) the gravity of the matters alleged.

The standard of proof referred to in s 140(2) is a restatement of the standard of proof referred to by Dixon J (as his Honour then was) in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362 (see Liquor Hospitality and Miscellaneous Union v Arnotts Biscuits Ltd [2010] FCA 770 at [13], (2010) 188 FCR 221 at 225 per Logan J).

22 Second, in those circumstances where it is alleged that Toll Transport took action “for a particular reason or with a particular intent”, s 361 casts upon Toll Transport the onus to prove “otherwise”. But to engage the benefit conferred by s 361, Mr Tomvald must adduce evidence that is “consistent with the hypothesis” that the action was taken for the reason or intent alleged: General Motors-Holden’s Pty Ltd v Bowling (1976) 51 ALJR 235 at 241 per Mason J (as his Honour then was). When addressing a predecessor provision to s 361 (namely s 5(4) of the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth)), Mason J in Bowling there concluded (at 241):

Section 5 (4) imposed the onus on the appellant of establishing affirmatively that it was not actuated by the reason alleged in the charge. The consequence was that the respondent, in order to succeed, was not bound to adduce evidence that the appellant was actuated by that reason, a matter peculiarly within the knowledge of the appellant. The respondent was entitled to succeed if the evidence was consistent with the hypothesis that the appellant was so actuated and that hypothesis was not displaced by the appellant. To hold that, despite the sub-section, there is some requirement that the prosecutor brings evidence of this fact is to make an implication which in my view is unwarranted and which is at variance with the plain purpose of the provision in throwing on to the defendant the onus of proving that which lies peculiarly within his own knowledge.

The “reverse” onus of proof – s 361

23 When addressing s 346 of the Fair Work Act and the prohibition there contained against the taking of “adverse action” because (inter alia) a person was not a member of an industrial association, in Board of Bendigo Regional Institute of Technical and Further Education v Barclay [2012] HCA 32, (2012) 248 CLR 500, French CJ and Crennan J observed in respect to that provision and s 361 (at 506):

[5] The task of a court in a proceeding alleging a contravention of s 346 is to determine, on the balance of probabilities, why the employer took adverse action against the employee, and to ask whether it was for a prohibited reason or reasons which included a prohibited reason.

Their Honours continued (at 517):

[44] There is no warrant to be derived from the text of the relevant provisions of the Fair Work Act for treating the statutory expression “because” in s 346, or the statutory presumption in s 361, as requiring only an objective enquiry into a defendant employer’s reason, including any unconscious reason, for taking adverse action. The imposition of the statutory presumption in s 361, and the correlative onus on employers, naturally and ordinarily mean that direct evidence of a decision-maker as to state of mind, intent or purpose will bear upon the question of why adverse action was taken, although the central question remains “why was the adverse action taken?”

[45] This question is one of fact, which must be answered in the light of all the facts established in the proceeding. Generally, it will be extremely difficult to displace the statutory presumption in s 361 if no direct testimony is given by the decision-maker acting on behalf of the employer. Direct evidence of the reason why a decision-maker took adverse action, which may include positive evidence that the action was not taken for a prohibited reason, may be unreliable because of other contradictory evidence given by the decision-maker or because other objective facts are proven which contradict the decision-maker’s evidence. However, direct testimony from the decision-maker which is accepted as reliable is capable of discharging the burden upon an employer even though an employee may be an officer or member of an industrial association and engage in industrial activity.

Justices Gummow and Hayne also relevantly observed in respect to both the term “because” and s 360 (at 534 to 535):

[100] The application of s 346 turns on the term “because”. This term is not defined. The term is not unique to s 346. It appears in s 340 (regarding workplace rights), s 351 (regarding discrimination), s 352 (regarding temporary absence in relation to illness or injury) and s 354 (regarding coverage by particular instruments, including provisions of the National Employment Standards).

[101] The use in s 346(b) of the term “because” in the expression “because the other person engages … in industrial activity”, invites attention to the reasons why the decision-maker so acted. Section 360 stipulates that, for the purposes of provisions including s 346, whilst there may be multiple reasons for a particular action “a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason”. These provisions presented an issue of fact for decision by the primary judge.

…

[103] With respect to what became s 346 of the Act, para 1458 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 stated:

“Clause 360 provides that for the purposes of Part 3-1, a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason. The formulation of this clause embodies the language in existing section 792 which appears in Part 16 of the [Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth)] (Freedom of Association) and includes the related jurisprudence. This phrase has been interpreted to mean that the reason must be an operative or immediate reason for the action (see Maritime Union of Australia v CSL Australia Pty Ltd [[2002] FCA 513 at [54] to [55], (2002) 113 IR 326 at 342 per Branson J]). The ‘sole or dominant’ reason test which applied to some protections in the [Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth)] does not apply in Part 3-1.”

(Emphasis added.) The phrase “operative or immediate reason” used in CSL is relevantly indistinguishable from the phrase “a substantial and operative factor” used by Mason J in Bowling.

[104] In light of the legislative history of s 346 and the intention of Parliament outlined above, the reasoning of Mason J in Bowling is to be applied to s 346. An employer contravenes s 346 if it can be said that engagement by the employee in an industrial activity comprised “a substantial and operative” reason, or reasons including the reason, for the employer’s action and that this action constitutes an “adverse action” within the meaning of s 342.

See also: Victoria (Office of Public Prosecutions) v Grant [2014] FCAFC 184 at [32], (2014) 246 IR 441 at 447 to 448 per Tracey and Buchanan JJ. Upon proof that an employee has exercised a “workplace right”, it is then presumed that that action was taken for the reason alleged unless the employer proves to the contrary: Kennewell v MG & CG Atkins [2015] FCA 716 at [52] per Tracey J; Tsilibakis v Transfield Services (Australia) Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 740 at [14] per White J. The rationale for s 361 casting the onus in this way is that the facts lie peculiarly within the knowledge of the employer: General Motors-Holden’s Pty Ltd v Bowling (1976) 51 ALJR 235 at 241 per Mason J; RailPro Services Pty Ltd v Flavel [2015] FCA 504 at [23], (2015) 242 FCR 424 at 432 per Perry J; Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Hall [2017] FCA 274 at [22] per Flick J.

24 With respect to the separate question as to the standard of proof to be applied when seeking to rebut the presumption, it was common ground between Mr Tomvald and Toll Transport that the standard as at that point in the analysis is the balance of probabilities. This approach is consistent with both the observations of French CJ and Crennan J in Board of Bendigo and with the following observations of Gray J in National Tertiary Education Union v Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology [2013] FCA 451, (2013) 234 IR 139 at 146:

[20] … Further, s 360 of the Fair Work Act recognises expressly that action may be taken for more than one reason. What the party seeking to rebut the presumption must do is to establish on the balance of probabilities that the alleged improper reason was not a reason for the taking of action. Generally (although as a matter of logic, not necessarily) the evidence as to the state of mind of the decision-maker or decision-makers will include evidence as to what are claimed to be the actual reasons for the decision. Even if the reasons advanced as actual reasons for the decision are accepted as such, the absence of evidence that there were no additional reasons, or that the actual reasons did not include the alleged proscribed reasons, will usually result in a failure to rebut the presumption.

THE 2013 ENTERPRISE AGREEMENT & QUESTIONS OF INTERPRETATION

25 Mr Tomvald’s employment has over the years been covered by various awards and two Enterprise Agreements – one being the Toll Group and Transport Workers Union Fair Work Agreement 2011-2013 and the other being the Toll Group – TWU Enterprise Agreement 2013-2017 (the “Enterprise Agreement”).

26 His employment with Toll Transport commenced on 1 July 2015.

27 Prior reliance upon the earlier 2011 Agreement largely fell away with the filing of the Further Amended Statement of Claim. Thereafter, it was common ground that it was the 2013 Enterprise Agreement which assumed immediate relevance.

28 Particular provisions of the Enterprise Agreement are relied upon by Mr Tomvald. Questions arose as to the manner in which those provisions are to be interpreted.

The provisions relied upon

29 Although the Enterprise Agreement should be construed in its entirety, some particular provisions assume greater prominence than others. Those provisions are the following.

30 Clause 2 sets forth as follows the objects of the Enterprise Agreement:

2. Objects

The objects of this Agreement include the following:

(a) promoting job security, effective workplace representation and training for Transport Workers;

(b) enhancing the safety and fairness of Toll’s operations;

(c) maintaining the safety net and enhancing fair working conditions for Transport Workers;

(d) enhancing the productivity and efficiency of Toll’s operations; and

(e) subject to reasonable practical requirements, such as adequately servicing industry peaks, promoting job security through the full utilisation of full-time permanent Transport Workers before the engagement of part-time, casual, labour hire or outside hire workers.

31 Clause 4.1 relevantly sets forth as follows the coverage of the Enterprise Agreement:

4.1 General

This Agreement applies to and is binding on Toll, all Transport Workers and the Union.

The phrase “Transport Workers” is defined in cl 3 as follows:

Definitions

…

Transport Worker means any person who is eligible to be a member of the Union and who is employed by Toll in Australia in any of the classifications contained in the Award or in the Local Agreements.

32 Clause 6(a) of the Enterprise Agreement provides as follows:

This Agreement incorporates the Award, provided that Part A of this Agreement and the Local Agreements will prevail over the Award to the extent of any inconsistency. An inconsistency will not arise simply because the Award provides a more beneficial entitlement to a Transport Worker than that contained in Part A of this Agreement.

The “Award” is defined for the purposes of the Enterprise Agreement in cl 3 as follows:

Definitions

…

Award means:

(i) the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2010; and

(ii) the Road Transport (Long Distance Operations) Award 2010.

33 Clause 12.6 of the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2010 (the “Award”) – the clause dealing with the “right to elect” to convert from casual employment to permanent employment – provides as follows:

Conversion of casual employment

(a) A casual employee, other than an irregular casual employee who has been engaged by a particular employer for a sequence of periods of employment under this award during a period of 12 months will thereafter have the right to elect to have their contract of employment converted to full-time employment or part-time employment if the employment is to continue beyond the conversion process.

(b) An employer of such an employee must give the employee notice in writing of the provisions of this clause within four weeks of the employee having attained such period of 12 months.

(c) The employee retains the right of election under this clause even if the employer fails to comply with clause 12.6(b).

(d) A casual employee who does not, within four weeks of receiving written notice, elect to convert their contract of employment to full-time employment or part-time employment will be deemed to have elected against any such conversion.

(e) Any casual employee who has the right to elect under clause 12.6(a), upon receiving notice under clause 12.6(b), or after the expiry of the time for giving such notice, may give four weeks notice in writing to the employer that they seek to elect to convert their contract of employment to full-time or part-time employment, and within four weeks or receiving such notice the employer must either consent to or refuse the election but must not unreasonably so refuse.

(f) A causal employee who has elected to be converted to a full-time employee or a part-time employee in accordance with clause 12.6(e) may only revert to casual employment by written agreement with the employer.

(g) If a casual employee has elected to have their contract of employment converted to full-time or part-time employment, the employer and the employee, subject to clause 12.6(e), must discuss and agree upon:

(i) which form of employment the employee will convert to, that is, full-time or part-time; and

(ii) if it is agreed that the employee will become a part-time employee, the number of hours and the pattern of hours that will be worked, as set out in clause 12.4(b).

(h) An employee who has worked on a full-time basis throughout the period of casual employment has the right to elect to convert their contract of employment to full-time employment and an employee who has worked on a part-time basis throughout the period of casual employment has the right to elect to convert their contract of employment to part-time employment, working the same number of hours and times of work as previously worked, unless other arrangements are agreed upon between the employer and employee. Upon such agreement being reached, the employee will convert to full-time or part-time employment. Where, in accordance with clause 12.6(e) an employer refuses an election to convert, the reasons for doing so must be fully stated to and discussed with the employee concerned and a genuine attempt made to reach agreement.

(i) An irregular casual employee is one who has been engaged to perform work on an occasional or non-systematic or irregular basis.

34 Clause 14 of the Enterprise Agreement provides as follows:

Consultation on workplace change

(a) If Toll is considering workplace changes that are likely to have a significant effect on Transport Workers, it will consult with the Union and any Transport Workers who will be affected by any proposal.

(b) As soon as practicable Toll must discuss with the Union and relevant Transport Workers the introduction of the change, the effect the change is likely to have on the Transport Workers, the number of any redundancies, the persons or class of persons likely to be affected and any reasonable alternatives to the change or redundancy. Toll must discuss measures to avert or mitigate the adverse effect of the change on the Transport Workers.

(c) Toll will give prompt and genuine consideration to matters raised about the change by the affected Transport Workers and the Union.

(d) As soon as a final decision has been made, Toll must notify the Union and the Transport Workers affected, in writing, and explain the effects of the decision.

(e) In the event that a Dispute arises in respect to any decision, proposal or consideration to effect any change, the parties agree to follow the disputes procedure in clause 15, and until the Dispute is resolved in accordance with that procedure the status quo before the Dispute arose will be maintained and work will continue without disruption.

(f) A reference to a change that is “likely to have a significant effect on Transport Workers” includes but is not limited to:

(i) the termination of the employment of Transport Workers; or

(ii) major change to the composition, operation or size of Toll’s workforce or to the skills required of Transport Workers; or

(iii) the elimination or diminution of a significant number of job opportunities (including opportunities for promotion or tenure); or

(iv) the significant alteration of hours of work; or

(v) the need to retrain Transport Workers; or

(vi) the need to relocate Transport Workers to another workplace; or

(vii) the restructuring of jobs.

(g) With the prior approval of Toll and subject to clause 39, the Union may enter Toll’s premises in order to consult with Transport Workers regarding a workplace change.

35 Clause 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement relevantly provides as follows:

… where a casual Transport Worker has been directly employed by Toll or engaged through a labour hire company to perform work for Toll on a regular and systematic basis for more than 6 months, the Transport Worker may elect to become a permanent Transport Worker, on a like for like basis, within the specific business unit at which the Transport Worker is engaged, in accordance with the Award.

Principles of interpretation

36 The general approach to the manner in which industrial instruments such as the present Enterprise Agreement are to be construed is well-settled.

37 An oft-repeated formulation of that general approach is that provided as follows by Madgwick J in Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184:

Legal principles

It is trite that narrow or pedantic approaches to the interpretation of an award are misplaced. The search is for the meaning intended by the framer(s) of the document, bearing in mind that such framer(s) were likely of a practical bent of mind: they may well have been more concerned with expressing an intention in ways likely to have been understood in the context of the relevant industry and industrial relations environment than with legal niceties or jargon. Thus, for example, it is justifiable to read the award to give effect to its evident purposes, having regard to such context, despite mere inconsistencies or infelicities of expression which might tend to some other reading. And meanings which avoid inconvenience or injustice may reasonably be strained for. For reasons such as these, expressions which have been held in the case of other instruments to have been used to mean particular things may sensibly and properly be held to mean something else in the document at hand.

But the task remains one of interpreting a document produced by another or others. A court is not free to give effect to some anteriorly derived notion of what would be fair or just, regardless of what has been written into the award. Deciding what an existing award means is a process quite different from deciding, as an arbitral body does, what might fairly be put into an award. So, for example, ordinary or well-understood words are in general to be accorded their ordinary or usual meaning.

See also: Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Linfox Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 829 at [30], (2014) 318 ALR 54 at 58 per Tracey J; Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Hail Creek Coal Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 532 at [6] per Logan J; Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Port Kembla Coal Terminal Ltd (No 2) [2015] FCA 1088 at [240], (2015) 253 IR 391 at 436 per Murphy J; Australian Workers’ Union v Cleanevent Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1477 at [13] per Flick J.

38 It is also well-settled that the words of an award are not to be construed “in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities”: City of Wanneroo v Australian Municipal, Administrative, Clerical and Services Union [2006] FCA 813 at [57], (2006) 153 IR 426 at 440. French J (as his Honour then was) observed as follows in that case (at 438 to 439):

[53] The construction of an award, like that of a statute, begins with a consideration of the ordinary meaning of its words. As with the task of statutory construction regard must be paid to the context and purpose of the provision or expression being construed. Context may appear from the text of the instrument taken as a whole, its arrangement and the place in it of the provision under construction. It is not confined to the words of the relevant Act or instrument surrounding the expression to be construed. It may extend to ‘… the entire document of which it is a part or to other documents with which there is an association’. It may also include ‘… ideas that gave rise to an expression in a document from which it has been taken’.

His Honour continued on to observe (at 440):

[57] It is of course necessary, in the construction of an award, to remember, as a contextual consideration, that it is an award under consideration. Its words must not be interpreted in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities – City of Wanneroo v Holmes (1989) 30 IR 362 at 378-379 and cases there cited. There is a long tradition of generous construction over a strictly literal approach where industrial awards are concerned – see eg Geo A Bond and Co Ltd (in liq) v McKenzie [1929] AR 499 at 503-4 (Street J). It may be that this means no more than that courts and tribunals will not make too much of infelicitous expression in the drafting of an award nor be astute to discern absurdity or illogicality or apparent inconsistencies. But while fractured and illogical prose may be met by a generous and liberal approach to construction, I repeat what I said in City of Wanneroo v Holmes (at 380):

‘Awards, whether made by consent or otherwise, should make sense according to the basic conventions of the English language. They bind the parties on pain of pecuniary penalties.’

A PERMANENT OR CASUAL EMPLOYEE

39 At the very outset of the case advanced on behalf of Mr Tomvald is the preliminary question as to whether he is a:

permanent; or a

casual

employee.

40 Mr Tomvald claims that he is already a “permanent employee”. If he is a “permanent employee” any question as to his “right” to convert from casual to permanent becomes unnecessary to resolve.

41 It is concluded that:

contrary to the submission advanced on behalf of Toll Transport, there is no “pleading” impediment to Mr Tomvald seeking declaratory relief as to his being a “permanent employee”

but that:

that question is resolved adversely to Mr Tomvald – he is not a “permanent employee”.

That being the conclusion reached, it is accordingly necessary to go on to resolve the questions which arise out of his claimed exercise of the “right” to convert from his status as a casual employee to that of a permanent employee.

The absence of any pleading impediment

42 The pleading which raises the question as to the status of Mr Tomvald’s employment is para [5] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim. That paragraph pleads as follows (without alteration):

5. Between October 2012 and the present day, tThe Applicant has been employed by Toll Transport:

(a) on a casual basis; or

(b) alternatively, on a permanent basis.

In response to this amended pleading, para [5] of the Further Amended Defence pleads as follows:

5. In response to the allegation in paragraph 5 of the Further Amended Statement of Claim, the Respondent:

(a) admits the allegation in paragraph 5(a) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim, save that the Respondent asserts that the Applicant’s casual employment by the Respondent began on 1 July 2015 22 October 2012;

(b) denies the allegation in paragraph 5(b) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim; and

(c) says that paragraph 5(b) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim is inconsistent with paragraph 5(a) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim and does not arise as a contention given that the Respondent admits paragraph 5(a).

The pleading point relied upon by Toll Transport is that the admission that Mr Tomvald is a casual employee precludes any further ability on the part of Mr Tomvald to pursue a claim that he is already a permanent employee or for this Court to resolve that alternative claim.

43 That submission is rejected.

44 The purpose of a pleading is to “state with sufficient clarity the case that must be met”: Banque Commerciale SA (in liq) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 286 to 287 per Mason CJ and Gaudron J. As to what is sufficient to inform the other party of the case it has to meet, Greenwood, McKerracher and Reeves JJ in Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 explained that:

[13] … courts do not, at least in the current era, take an unduly technical or restrictive approach to pleadings such that, among other things, a party is strictly bound to the literal meaning of the case it has pleaded. The introduction of case management has, in part, been responsible for this change in approach …

See also: Sherrin Hire Pty Ltd v Sherrin Rentals Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1107 at [44] per Edelman J. Pleadings, it may further be noted, “are but a means to an end, not an end in themselves”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singapore Airlines Cargo Pte Ltd [2009] FCA 510 at [95], (2009) 256 ALR 458 at [97] 472 to 473 per Jacobson J.

45 There is no uncertainty occasioned by para [5] as to the case being advanced on behalf of Mr Tomvald: it was being asserted that he was either a permanent employee or a casual employee. The admission made by Toll Transport that he was a casual employee cannot preclude Mr Tomvald also advancing for resolution his alternative claim to be a permanent employee.

46 The lack of any uncertainty on the part of Toll Transport as to this alternative claim for declaratory relief is only reinforced by the very fact that it was the amendment to insert the alternative claim that occasioned the filing of the Cross-Claim.

47 The alternative manner in which Mr Tomvald was advancing his claim was also a matter canvassed during the case management of the present proceeding and the basis upon which the hearing was conducted.

Permanent or casual – questions of principle

48 There is no definition in the Enterprise Agreement of the phrase “casual employee”.

49 The Fair Work Act does not set forth any definition of a “casual employee”.

50 But cl 6(a) of the Agreement “incorporates the Award”. And cl 12.5(a) of the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2010 defines a casual employee as “an employee engaged as such and paid by the hour”.

51 The test to be applied when determining whether an employee is casual or permanent has attracted differing views.

52 One approach is to focus upon the substance of the relationship. One characteristic of casual employment, on this approach, is the ability of an employer to offer employment on a particular day and the ability of an employee to choose to work: Reed v Blue Line Cruises Ltd (1996) 73 IR 420 at 425 per Moore J. His Honour was there sitting in the former Industrial Relations Court. In that case, Mr Reed’s employment by Blue Line Cruises had been terminated. In determining whether Mr Reed’s employment fell within the relevant provisions of the then Industrial Relations Act 1988 (Cth), Moore J concluded that that question depended upon whether he was a “casual employee” as that expression had been used in reg 30B of the Industrial Relations Regulations (Cth). In resolving that question, his Honour observed (at 424 to 425):

In Australian domestic law, the expressions “casual employee” or “casual employment” are expressions with no fixed meanings. In my view, it would be wrong in principle, to treat the character ascribed by an award to particular employment and adopted by the parties, as determining conclusively the character of the employment for the purposes of reg 30B which reflects employment described in Art 2(2) of the [Convention concerning Termination of Employment at the Initiative of the Employer].

…

What then, is likely to have been the feature of the employment at the time of the engagement that would characterise it as an engagement on a casual basis? Plainly it involves a notion of informality or flexibility in the employment following the engagement.

His Honour then set out a number of dictionary definitions and continued (at 425):

A characteristic of engagement on a casual basis is, in my opinion, that the employer can elect to offer employment on a particular day or days and when offered, the employee can elect to work. Another characteristic is that there is no certainty about the period over which employment of this type will be offered. It is the informality, uncertainty and irregularity of the engagement that gives it the characteristic of being casual.

To similar effect are the following observations of Wilcox, Marshall and Katz JJ in Hamzy v Tricon International Restaurants [2001] FCA 1589, (2001) 115 FCR 78 at 89:

[38] … The essence of casualness is the absence of a firm advance commitment as to the duration of the employee’s employment or the days (or hours) the employee will work. But that is not inconsistent with the possibility of the employee’s work pattern turning out to be regular and systematic.

See also: Williams v MacMahon Mining Services Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1321 at [33] to [36], (2010) 201 IR 123 at 130 to 131 per Barker J. In Re Secure Employment Test Case [2006] NSWIRComm 38, (2006) 150 IR 1 at 57 the Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales also looked as follows to the substance of the relationship between employer and employee:

[231] The concept of a “casual” which has emerged through historical employment practice and industrial jurisprudence and which has now long been defined and regulated in awards in this State is essentially one in which: the employee has a short term engagement; shifts are irregular and unpredictable; the employee is not obliged to accept an offer to work a particular shift; the employee’s employment technically commences at the beginning of a particular shift and ceases at the end of that shift; the employee is paid a loading as compensation for, amongst other things, annual leave and other benefits “accrued” during each shift worked; and the employee has no expectation of being rostered for another shift.

53 What begins as “casual employment” may, however, change over time. Indeed, in Ledger v Stay Upright Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 659, Buchanan J commented upon the conclusion of Moore J in Reed v Blue Line Cruises as follows:

[61] … In Reed, Moore J was influenced against a conclusion of casual employment by the apparent regularity and eventual overall period of Mr Reed’s engagement. However, his Honour stressed that he was assigning a meaning to the notion of casual employment for the purpose of the Convention concerning Termination of Employment at the Initiative of the Employer, which was a meaning different, probably, from the meaning for the purpose of award coverage.

[62] It is clear that his Honour accepted that the appropriate characterisation of the nature of employment is one which must be determined by reference to what is known at the commencement of the engagement. It must be accepted that, over time, repetition of a particular working arrangement may become so predictable and expected that, at some point, it may be possible to say that what began as discrete and separate periods of employment has become, upon the tacit understanding of the parties, a regular ongoing engagement (for an example of historical interest, see Cameron v Durning [1959] AR (NSW) 142). On the other hand, retention of the same initial arrangements (month-to-month rostering, imprecision of days and hours, timesheets recording actual hours, absences or unavailability at the discretion of the employee) may indicate that the parties have chosen to perpetuate those initial arrangements – i.e. casual engagement with an entitlement to pay arising as and when work is actually performed.

[63] In my view, in the present case the second approach is the one which the evidence as a whole suggests. Even though the initial arrangements came to be repeated for many years, I see nothing to indicate that the parties agreed to change the specified nature of the engagement or that there was any later mutual intent that the engagement should be other than casual, as was clearly stated in each initial contract. The parties themselves have conducted the case on the basis that such a change did not occur.

54 Another possible approach which has been expressed, albeit in the context of considering whether a casual employee was an employee engaged as such, is to focus upon the terms of engagement. On that approach the label attached to the employment at the outset is conclusive as to the status thereafter of the employment relationship: Telum Civil (Qld) Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2013] FWCFB 2434, (2013) 230 IR 30. A Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission there concluded that the specification of casual employment in federal awards had diverged from the earlier general law position. In so concluding the Full Bench said (at 36) (without alteration):

[25] [Re Metal, Engineering and Associated Industries Award, 1998 – Part 1 (2000) 110 IR 247] demonstrates how and why the specification of casual employment in Federal awards had diverged from the (ill-defined) general law position to a position where, by the time of award modernisation process, for many, if not most, Federal awards, an employee was a casual employee if they were engaged as a casual (that is, identified as casual at the time of engagement, perhaps with a requirement of a writing) and paid a casual loading. The Full Bench recognised that this approach had led to a position where employees with regular and systematic hours on an ongoing basis could still be “casual employees” under a Federal award.

55 The potential divergence of views expressed was considered by White J in Fair Work Ombudsman v Devine Marine Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1365. There under consideration was cl 12 of an award which referred to “[f]ull-time employment” as “[a]ny employee not specifically engaged as being a part-time or casual employee” and cl 14 which referred to an “employer when engaging a casual”. His Honour reviewed the authorities, including Blue Line Cruises and Hamzy, and concluded as follows (adopting the construction in Telum Civil):

[144] It is sufficient in my opinion to state that, in the present case, the former construction draws support from two considerations and should be adopted. First, the term “specifically engaged” in cl 12 indicates that the focus is on the agreement of the parties at the commencement of the employment as to the character of the employment. Secondly, the requirement in cl 14.3 for the observance of formality at the time of engagement of a casual employee suggests that the word “engaged” is directed to the agreement made between the parties rather than to the manner and circumstances in which the employee does in fact carry out his or her work.

[145] In my opinion, neither Mr James nor Mr Kouka can be regarded as casual employees on this understanding of the definition in cl 14.1. Nothing was said to them at the time of their engagement about being casuals. It cannot be concluded therefore that they were “engaged” as casuals. They gave no evidence that they had, subjectively, regarded themselves as casuals. Further, and in any event, they were not paid as casuals.

[146] The better characterisation of their employment is that of full-time employees working pursuant to a contract with a fixed term. Accordingly, this claimed contravention of the Award fails.

56 Subsequent to his decision in Devine Marine Group, White J had a further occasion to consider whether an employee was a “casual” employee in Fair Work Ombudsman v South Jin Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1456. Contraventions of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) and the Fair Work Act were there alleged. One part of the case turned on whether employees were casual employees with the consequence that they were entitled to the casual loading then prescribed. In that context, his Honour observed:

[66] Although casual employment is common, its precise definition has proved elusive. In its original conception, casual employees were those whose work was intermittent or irregular (Doyle v Sydney Steel Co Ltd (1936) 56 CLR 545 at 555) so that the employees did not know when completing one period of work if, or when, they would be employed again. Casual employees were generally thought to be engaged under a series of separate and distinct contracts with each contract terminating on the completion of the task or period for which they were engaged. Being generally paid by the hour, their employment could be terminated on an hour’s notice.

His Honour then proceeded to refer to (inter alia) Reed v Blue Line Cruises and Hamzy and continued:

[71] In addition to these features of casual employment, the authorities indicate that the characterisation of a worker’s employment as casual, or otherwise, is essentially a question of fact in which no single criterion is likely to be decisive. Instead, regard must be had to a number of matters, including the way in which the parties themselves regarded their relationship, any commitment by the employer or the worker to ongoing employment, the regularity or otherwise of the worker’s hours or days of work, how the worker was notified of each period of work, the payment of an hourly rate for the hours actually worked, any indication that the hourly rate was intended to encompass leave entitlements, the absence of payment of the benefits associated with employment of an indefinite nature such as paid annual leave, sick leave and public holidays, and whether the employer and worker were able to refuse to offer or accept, as the case may be, further work.

(Citations omitted.)

Reference was then made to the terms of the award there in question. In the end, it was concluded that some employees were casual employees and some were full-time employees. No reference was made by his Honour to his earlier decision in Devine Marine – presumably upon the basis that that decision was not apposite to the different question required to be answered in South Jin.

57 It was submitted on behalf of the Applicant in the present case that Devine Marine should not be followed for any of three reasons, namely:

the fact that the views expressed were expressed without the benefit of submissions;

the conclusion reached is not consistent with a long history of authorities which stresses the need to consider the substance of the employment relationship rather than matters of form; and

if the conclusion be correct, it has the potential to lead to the undesirable consequence that an employee may be regarded as a “casual employee” for the purposes of the application of an industrial agreement but a “permanent employee” for the purposes of determining (for example) leave entitlements.

It is, with respect, not self-evident that there is such a stark divergence of principle in the authorities as was suggested in submissions. Each of the authorities is readily explicable by reference to the issues sought to be resolved and (in particular) whether the issue to be resolved focused upon the basis upon which the employee was initially engaged.

58 But it is unnecessary to resolve the extent to which there is any divergence in the approaches pursued by these decisions. On the facts of the present case, it is concluded that Mr Tomvald:

was “engaged” as a casual employee;

his employment had the character of casual employment; and

he remained throughout employed as a casual employee.

Whichever approach is pursued the result is the same: subject to his right to “convert”, Mr Tomvald was and remained a “casual” employee. He was initially “engaged” as a casual and, notwithstanding the length of his employment, he remained a “casual” employee.

The facts – the terms of engagement & the work performed

59 There is no document which unequivocally records the basis upon which Mr Tomvald was engaged either as at:

2007 by Toll Personnel Pty Ltd; or

1 July 2015 by Toll Transport.

60 However, a letter dated 26 May 2015 from the Toll Group advised Mr Tomvald of the change in the identity of his employer from Toll Ipec Pty Ltd to Toll Transport. That letter attached a document headed “Payroll Transfer Project – Q&As” which stated in part as follows (without alteration):

What will be the impact on employees?

There will be no negative impact on employees. In particular:

1. Employees’ terms, conditions of employment and all leave entitlements will not change. The same enterprise agreements, awards and contracts of employment will continue to apply. No change to these aspects will occur as a result of the change in employer.

2. There will be no change to an employee’s duties or place of work.

3. Your new legal entity employer will recognise employees’ prior service with their current employer for all purposes.

4. Your new legal entity employer will take on all of accrued leave entitlements, including personal leave.

5. Your new legal entity employer will recognise any leave arrangements for which approval has been obtained prior to 1 July 2015.

In short, it will be “business as usual”. The only change will be the name of a person’s employer.

Prior to that letter, it would appear that Mr Tomvald was employed by Toll Ipec Pty Ltd. There was, however, no document before the Court which recorded the basis upon which Mr Tomvald was employed by Toll Ipec Pty Ltd.

61 An earlier letter dated 11 October 2012 does, however, records an offer to appoint Mr Tomvald as a “Freight Handler on a casual basis with Toll Pty Ltd”. That letter continued on to state:

1. Terms of Engagement and Duties

1.1 You are engaged as a casual employee and your responsibilities are set out in the position description in the attached Schedule.

1.2 You will be employed by the hour and each engagement will constitute a separate contract of employment on the same terms and conditions as are set out in this document. Starting and finishing times are to be agreed with Toll and are established to suit the operational requirements of Toll.

1.3 Your employment as a casual employee may be terminated at the conclusion of your rostered engagement by the provision of notice of such termination at the earliest possible opportunity or by the paying of an amount equivalent to the pay for that rostered engagement. Nothing in this Agreement shall affect the legal right of Toll to terminate your employment without notice or pay in lieu of notice if you are guilty of misconduct, or dishonesty, or persistently or materially breach the terms and conditions of your employment or commit any other act or omission which justifies summary termination.

1.4 You will perform all acts, duties and obligations usually associated and consistent with your job title and position description and comply with all lawful directions given to Toll. Toll may assign you to undertake the duties of another position, either in addition to or instead of your normal duties, it being understood that you will not be required to perform duties which are not reasonably within your capabilities. In addition, Toll may require you (as part of your duties of employment) to perform duties or services for any related body corporate where such duties or services are of a similar status to or consistent with your position with Toll. If there is a change in your position or in your responsibilities, your terms and conditions of employment will remain the same except where specific variations are agreed.

That offer was accepted by Mr Tomvald on 17 October 2012.

62 To the extent that an inference can be drawn from such an incomplete account of the offers of employment made to Mr Tomvald, and to the extent that the terms upon which Mr Tomvald was “engaged” are conclusive, it is concluded that Mr Tomvald was initially engaged as a casual employee.

63 It is further concluded that Mr Tomvald remained a casual employee throughout his employment with any one or other of the Toll Group of companies. Separate from any consideration given to the terms upon which he was engaged, the substance of his employment, on balance, has the character of casual employment and not permanent employment.

64 In reaching that conclusion, reliance has been placed (inter alia) upon Mr Tomvald’s own assessment of the character of his employment. This was an issue pursued in his cross-examination on a number of occasions. It suffices to refer to the following exchange between Mr Tomvald and Counsel for Toll Transport. At the outset, Mr Tomvald was taken to the October 2012 letter and there was the following exchange:

So as far as you’re aware, Mr Tomvald, the only formal letter which spoke of terms and conditions really goes back to the letter which was dated 2012 that I took you to earlier? — Yes.

And you understood that those terms and conditions continued to apply to your engagement within the IPEC business division? — Yes, sir.

And, in fact, you continued to receive the casual rates that applied under whatever agreement applied to your employment? — Yes, sir.

…

And you’ve continued to work during that whole period as a casual freight handler? — Yes, sir.

He was then taken to his second affidavit and questioned as to his reasons for seeking permanent employment as follows:

If I can just ask you to go to paragraph 7, you talk there about the reason why you were keen on a permanent job and you say, “Even though I knew that that would mean I would lose my 25 per cent casual loading” – so it was clear in your mind that, as a casual employee, you were getting this additional loading on top of whatever rates might have applied? — Yes, sir.

And, in your mind, the real concern was that while the going was good for a long period of time, you understood that as a casual, to quote your words, “I can lose my job at any time”? — Yes, sir.

And I don’t have to be paid a redundancy? — Yes, sir.

And, indeed, that was your understanding also back at 2007 when you were first engaged as a casual employee? — Yes.

And again when you were offered employment on a casual basis with Toll Proprietary Limited in 2012 – again, you had this concern in the back of your mind? — Yes, sir.

And that’s, you say, a concern that has always been in the back of your mind, including currently? — Yes.

That as a casual employee, you stood the risk of losing your job without any notice? — Yes.

That you wouldn’t get any redundancy? — Yes.

A little later Mr Tomvald was taken to his first affidavit and questioned on the topic of the hours he worked as follows:

And if I can just come back to the work that you do at Toll – now, paragraph 6 of your first statement, if I can go back to that, you say:

I had no finishing time. That would vary depending on the work. Although my hours varied from day to day, I was usually rostered for seven or more hours per shift.

Now, I asked you about that a moment ago, but just so that I’m clear, the overtime that you did, there were days when there was no overtime required or offered? — Yes, sir.

And there were other days where there may be some overtime required. And if it was offered, you would readily put your hand up for it? — Yes, sir.

But at the beginning of each day, you wouldn’t know what amount of overtime you may get for that particular shift? — No, sir.

And, of course, you understood that for the overtime there were increased rates based on whatever the casual rate applied to you? — Yes, sir.

So it was certainly more beneficial to do overtime with those casual rates? — Yes, sir.

65 Although it may be that an employee is under a mistaken apprehension as to the status of his employment and mistakenly believes that he is a casual and not a permanent employee, there was no such uncertainty or mistaken apprehension in the mind of Mr Tomvald. He recognised that he was a casual employee whose hours of work depended upon the availability of work and he was, moreover, content to be a casual employee because of the increased rates of pay that were payable to such employees.

66 Although other facts may have supported a case that he was a permanent employee, such as the manner in which his applications for leave were processed, it is concluded on balance that Mr Tomvald was a casual employee, including from the time when he was employed by Toll Transport from 1 July 2015.

THE RIGHT TO CONVERT FROM CASUAL TO PERMANENT EMPLOYMENT

67 Albeit the last of the contraventions pleaded, it was the ninth contravention which assumed primary importance for Mr Tomvald.

68 The ninth contravention alleged by Mr Tomvald is that Toll Transport refused to convert his employment to permanent employment “on a like-for-like basis”. This allegation obviously assumes that there is a right on the part of Mr Tomvald to convert his employment from casual to permanent and seeks to focus specific attention upon both the source of that right and the nature of the permanent employment to which he says he is entitled.

69 Paragraphs [29] through to [48] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim set forth the contraventions alleged. Paragraph [48] pleads as follows (without alteration):

Contravention 9: failure to convert on a like-for-like basis

48. By refusing to convert the Applicant’s employment to permanent employment working the same hours he worked during the twelve months prior to 18 May 2016, Toll Transport contravened clause 21(e) of the Agreement and 12.6 of the Award (as incorporated into the Agreement by clause 6(a) of the Agreement).

The principal relief sought, as set forth in the Further Amended Statement of Claim, is a declaration that “Toll Transport is obliged to convert the Applicant’s employment to full-time permanent employment”. An order is also sought for the payment of compensation and an order for the imposition of penalties.

70 The claim by Mr Tomvald is that Toll Transport has not complied with the right conferred by cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement and cl 12.6 of the Award and thereby contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act. Any penalty imposed should, he maintains, be made payable to him.

71 It is concluded that cl 21(e) does confer a right to convert to full-time permanent employment. Permanent full-time employment is employment for a period of 38 hours per week. Mr Tomvald sought to exercise that right on 25 May 2016 and was wrongfully denied the employment to which he was entitled when Mr Jones emailed Mr Selig on 27 May 2016 offering permanent employment of 30 hours per week. The offer made to Mr Tomvald, accordingly, fell short of offering him the full-time permanent employment of 38 hours per week to which he was entitled.

The source of the right to convert

72 The source of the right to convert from casual employment to permanent employment is identified by Mr Tomvald as being found in cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement and cl 12.6 of the Award.

73 There is one obvious difference between the two clauses.

74 Clause 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement provides for a right of election “where a casual Transport Worker has been directly employed by Toll … on a regular and systematic basis for more than 6 months”. Clause 12.6(a) of the Award refers to a “right to elect” conferred on a “casual employee, other than an irregular casual employee who has been engaged … for a sequence of periods of employment under this award during a period of 12 months”.

75 But that difference assumes no present relevance. Mr Tomvald had been regularly employed for a period in excess of twelve months when he sought to exercise the right to covert.

The facts – the hours worked

76 Mr Tomvald’s position is that it was on 25 May 2016 that he insisted upon his right to convert from a casual position to a permanent position. It was also his position that if an analysis is undertaken of his work with Toll Transport in the period prior to May 2016, that analysis exposes the fact that:

he worked most days from Monday to Friday, exceptions being in respect to public holidays and a period of about five weeks when he was on leave and taking a holiday in Europe;

on average he worked an 8 hour shift commencing at 4.00am; and

with very limited exceptions he worked at the premises of Toll Transport at the Bungarribee facility, the exceptions being isolated occasions on which he was required to work at a different location, being the Sharp location.

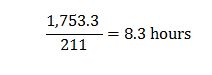

77 Based upon information provided by Toll Transport, Mr Selig – the godfather of Mr Tomvald and a consultant with the Workplace Advisory Group – calculated that during the period from 18 May 2015 to 13 May 2016, Mr Tomvald worked 1,753.3 hours in total over 211 shifts. Mr Selig then performed the following calculation:

This calculation exposed the average number of hours said to have been worked per shift and excluded from the calculation the days Mr Tomvald did not work, being days such as public holidays, days when he was absent and days when he was on leave. Mr Selig also calculated that the average number of ordinary hours worked per shift was 7.2 hours.

78 But Mr Selig’s calculations may be left to one side.

79 It was during the course of final submissions that concurrence was reached between the parties as to the “raw facts” of relevance to the hours worked. A table was helpfully prepared which set forth what was agreed between the parties as to the hours worked for the 12 month period prior to May 2016, namely:

Total hours | 1,770.80 |

Total ordinary hours | 1,570.60 |

Total shifts (excl. OT shifts) | 210 |

Per shift | |

Average hours per shift | 8.43 per shift |

Average ordinary hours per shift | 7.48 per shift |

Per week | |

Average hours per week (52 weeks) | 34.05 per week |

Average ordinary hours per week (52 weeks) | 30.20 per week |

Per working week | |

Average hours per week (46 weeks) | 38.5 per week |

Average ordinary hours per week (46 weeks) | 34.14 per week |

This table, it will be noted, shows the total number of ordinary hours worked and the total number of shifts as being 210 (rather than 211). The table substantially corroborates the account given by Mr Tomvald as to the hours and regularity of the work he performed.

A like for like basis

80 It is against this factual background and the terms of cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement that the offer made to Mr Tomvald is to be considered.

81 The offer as initially contemplated in the letter dated 18 May 2016 seeking “Expressions of Interest for Permanent Part-time Positions” was an offer for positions “made up of 4 hour, 5 hour and 6 hours shifts”. The offer as ultimately made to Mr Tomvald, as communicated in an email sent on 27 May 2016 was for “30 hours a week” which was said to be “in line with Cl. 21(e) of the Toll Group – TWU Enterprise Agreement and the award”.

82 The basis upon which “expressions of interest” were first sought and the subsequent offer were made and the calculations undertaken by Toll Transport at the time the offer was made need to be revisited when consideration is given to whether Toll Transport made the offer “because” of the exercise of any “workplace right”. For present purposes, what matters is whether the offer as made was in accordance with the entitlement conferred by cl 21(e).

83 It is concluded that the offer did not reflect the right conferred by cl 21(e) to convert to permanent employment on a “like for like basis”.

84 Clause 21(e) is not a clause without difficulty of construction, not the least of which is the meaning to be ascribed to the phrase “a like for like basis”.

85 No difficulty of application arises in respect to the introductory terms of cl 21(e). At the time he sought to exercise the right to convert, Mr Tomvald had been “directly employed by Toll ... to perform work for Toll on a regular and systematic basis for more than 6 months”.

86 Nor is there difficulty in accepting that the clause conferred a right to “elect to become a permanent Transport Worker”.

87 Some initial difficulty is encountered by reason of the fact that neither the Award nor the Enterprise Agreement defined “permanent Transport Worker”. Clause 12 of the Award set forth the three bases upon which an employee may be engaged, being “full-time, part-time or casual”, under the heading “[t]ypes of employment”. A full-time employee was there defined as “an employee who is engaged to work an average of 38 ordinary hours per week”. But cl 12 did not refer to a position described as a “permanent Transport Worker”. The reference to 38 hours per week, however, has a parallel in cll 3 and 22 of the Enterprise Agreement, which define a “Permanent Part-Time Transport Worker” as (inter alia) one who is rostered to work less than 38 hours per week. Clause 3 of the Enterprise Agreement defines the phrase “Transport Workers” but does not define “permanent Transport Worker”.

88 Notwithstanding such limited ambiguity as may be occasioned by the absence of an express definition of the phrase “permanent Transport Worker”, it is readily apparent that such a person is an employee who is not a casual employee and who works not less than 38 hours per week.

89 The concluding phrase found within cl 21(e), namely “in accordance with the Award”, also presents some difficulty. Clause 12.6 of the Award also addresses “[c]onversion of casual employment”. That clause sets forth both procedural and substantive provisions addressing both the procedure to be followed (e.g., cl 12.6(b)) and the substantive right to convert (cl 12.6(a)). But that to which the right conferred by cl 21(e) is qualified is expressed to be “the Award” as a whole. The right to convert conferred by cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement, it is concluded, covers the field as to the right to convert to the exclusion of cl 12.6. Other than providing some limited assistance as to the meaning of the phrase “permanent Transport Worker” employed in cl 21(e), the concluding phrase within cl 21(e) has little other work to do.

90 The greatest difficulty of construction, and the difficulty which consumed the bulk of oral submissions, was the meaning to be given to the phrase “like for like”. That phrase is not defined.

91 Casual employees, like Mr Tomvald, were persons who did not have the security of a permanent position and who were subject to employers choosing to offer either work or no work and were persons who could choose to work if they so wished (cf. Reed v Blue Line Cruises Ltd (1996) 73 IR 420). Casual employees were also employees who (inter alia):

received a salary loading not received by permanent employees; and

were not entitled to holiday leave or sick leave.

A “like for like” conversion from casual employment to a permanent position, obviously enough, required some transition from the rights and entitlements of a casual employee to those of a permanent employee. A “like for like” conversion would not entitle a casual worker to take with him all of those rights and entitlements which casual workers possess but which are not possessed by a permanent worker. Conversely, conversion from the position of a casual employee to that of a permanent employee would carry with it some new and additional benefits that were not possessed by casual employees.

92 Subject to such general observations, it is considered imprudent to attempt any rigid definition of the phrase “like for like”. The phrase is to be interpreted in the same manner as other provisions of an industrial agreement, namely “with a practical bent of mind” and in the manner which it was “likely to have been understood in the context of the relevant industry”: Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184 per Madgwick J. The phrase is to be understood as requiring a comparison between the nature and extent of the work previously performed by a casual employee with that of a permanent employee performing much the same work. It is a phrase which necessarily has to be applied to the facts and circumstances of each individual employee and the workplace in which work is performed.

93 Although a mathematical calculation (such as that performed by Mr Selig) may help to inform the application of the phrase to the facts of a particular employee, at the end of the day it remains a matter for practical judgment.

94 On the facts of the present case, the nature and extent of the ordinary hours worked by Mr Tomvald was that of an employee who regularly worked a little less than 8 ordinary hours per shift and about 34 hours per week. If reference is made to the actual number of hours worked, being ordinary hours together with overtime, he worked a little more than 8 hours per shift and a little more than 38 hours per week. For the purpose of these calculations, the average weekly hours worked are calculated on the basis of Mr Tomvald working 46 weeks per year, which is considered appropriate given that a casual worker is not entitled to sick leave or holiday leave. A permanent employee who takes sick leave and holiday leave would also work for 46 weeks per year.

95 The comparison, it is accepted, may not be mathematically precise. But mathematical precision is not required. It is a tool which merely assists in reaching an informed decision when comparing competing positions. Nor should it be expected, in an industrial context, that a detailed auditing of actual hours worked be undertaken before reliance can be placed upon cl 21(e).

96 To meet the requirements of cl 21(e) to convert his employment on a “like for like” basis, Mr Tomvald was entitled to a permanent full-time position.

97 A position which offered “4 hour, 5 hour and 6 hour shifts” fell short of that entitlement. On any view of the facts, Mr Tomvald was regularly working Mondays to Fridays for periods in excess of 6 hours per shift.

98 The right which is conferred upon an employee by cl 21(e) is not to be constrained by that which an employer may be prepared to offer. Clause 21(e) confers a valuable right upon a casual employee who can bring himself within the benefit of that clause. That right is not merely a right to convert to a permanent position; it is also a right to convert to a permanent position on a “like for like basis”. It is not a matter within the sole province of an employer to offer less than the right conferred.

99 No case was sought to be advanced that a permanent full-time position was not available for Mr Tomvald.

The contravention of s 50

100 Toll Transport has contravened cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement.

101 The contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act has, accordingly, been made out.

102 Having resolved the principal matter dividing the parties, namely Mr Tomvald’s right to “covert” and the last of the contraventions of the Fair Work Act relied upon, it is nonetheless necessary to consider the remaining contraventions.

NOTIFICATION

103 The first of the contraventions alleged by Mr Tomvald asserts a failure to notify him of the provisions of cl 21(e) of the Agreement and cl 12.6 of the Award.

104 Paragraph [29] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim thus pleads as follows (without alteration):

Contravention 1: failure to notify of conversion rights

29. Toll Transport did not notify the Applicant in writing of the provisions of clause 21(e) of the Agreement and 12.6 of the Award (as incorporated into the Agreement), after six months’ regular and systematic employment.

This pleading should be considered in the context of the relief claimed in para [52(a)] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim. That paragraph sought declaratory relief expressed as follows (again without alteration):

Declarations that Toll contravened:

(a) section 50 of the FW Act, clause 21(e) of the agreement and clause 12.6 of the Award (as incorporated into the Agreement by clause 6(a) of the Agreement) by failing to notify the Applicant of the provisions of clause 21(e) of the Agreement and 12.6 of the Award (as incorporated into the Agreement by clause 6(a) of the Agreement) after six months’ regular and systematic employment;

105 Clause 12.6(a) of the Award provides for the “right to elect”; cl 12.6(b) provides that an “employer … must give the employee notice in writing … within four weeks of the employee having attained such period of 12 months”, 12 months being the period after which the right to convert accrued under the Award.

106 This contravention, as frankly acknowledged by Counsel on behalf of Mr Tomvald, placed him in a dilemma: if the right to convert is that conferred by cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement, cl 12.6 of the Award assumes little (if any) relevance and the alleged first contravention would most probably fail; if the “right to elect” is that conferred by cl 12.6 of the Award, cl 12 remains the operative source of the entitlement to convert and the alleged first contravention remains “in play”.

107 If forced to make a choice, Counsel for Mr Tomvald submitted that he would prefer to place reliance upon cl 21(e) of the Enterprise Agreement and lose the allegation of a failure to notify in accordance with cl 12.6(b) of the Award.

108 Any incorporation of the Award into the Enterprise Agreement is to be found either in:

clause 21(e) itself; or in

clause 6 of the Enterprise Agreement.