FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1047

Table of Corrections | |

4 September 2017 | In [42] the names of the individual consumers have been removed and replaced with initials. |

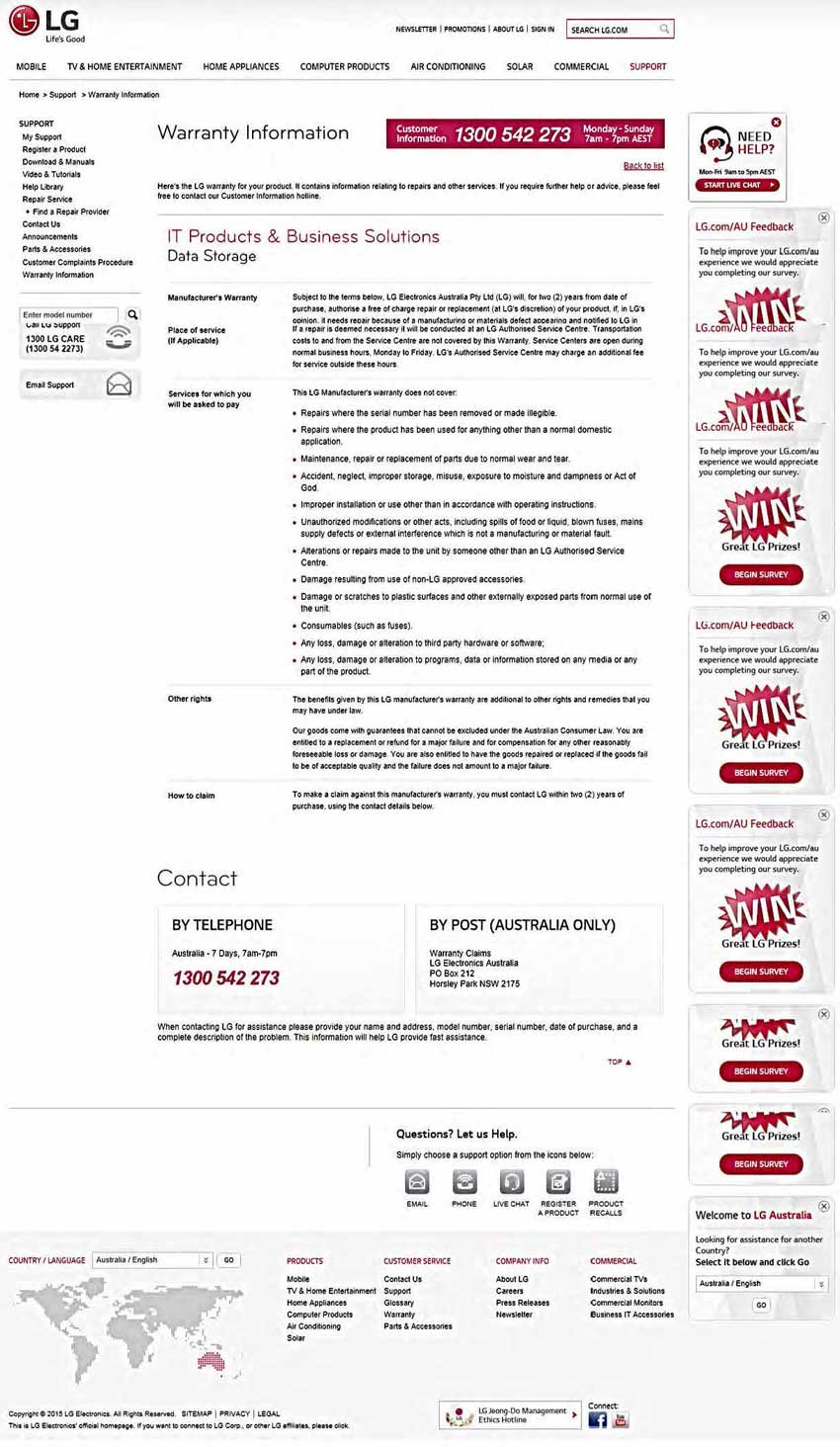

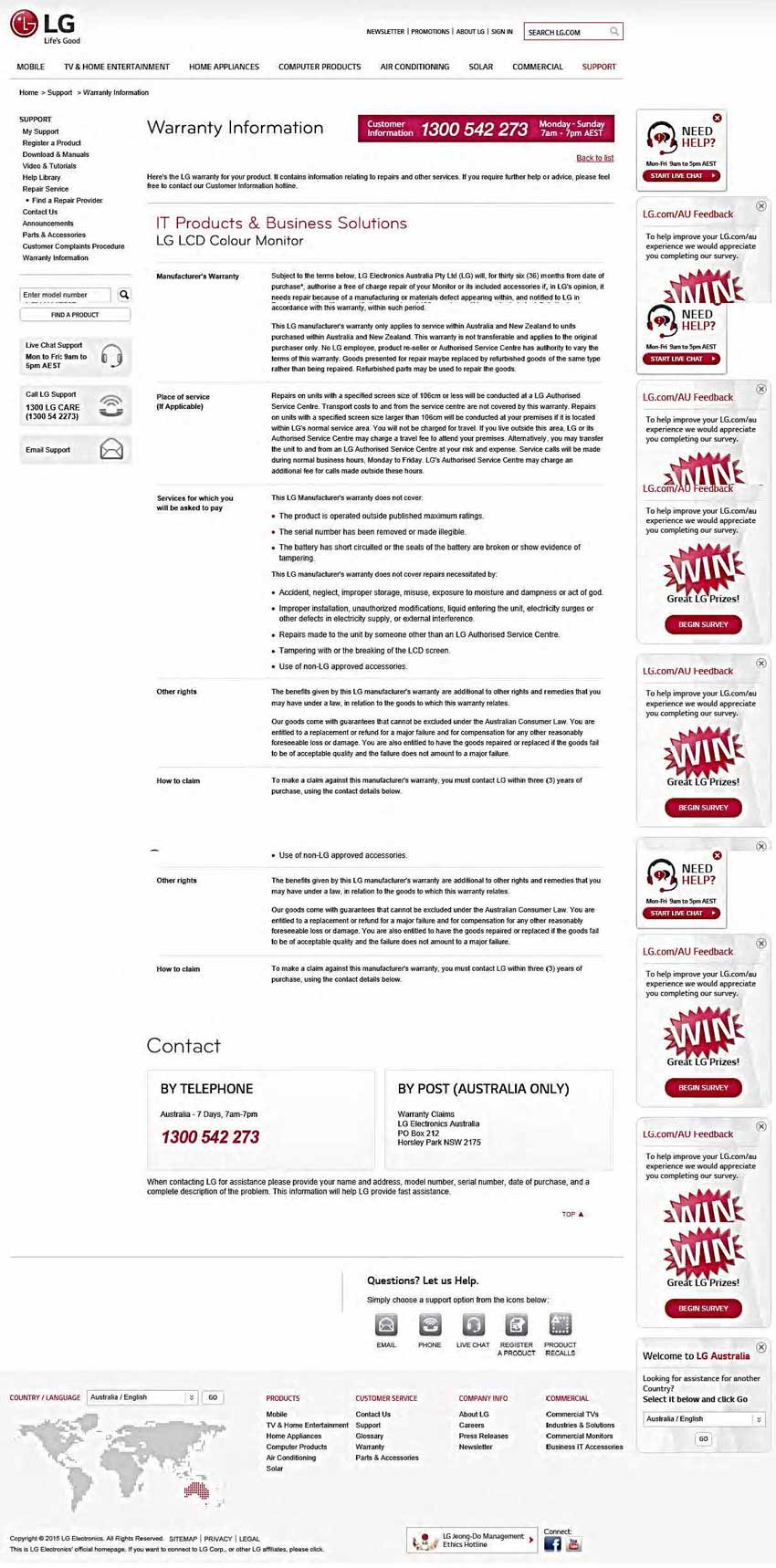

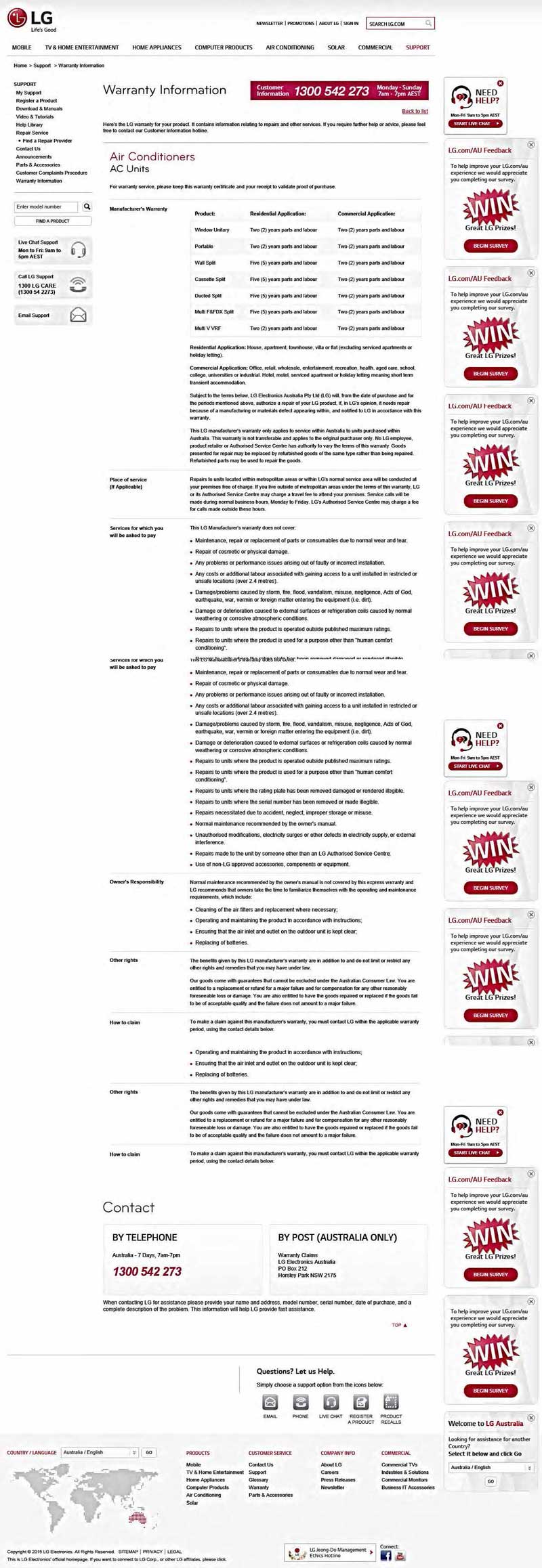

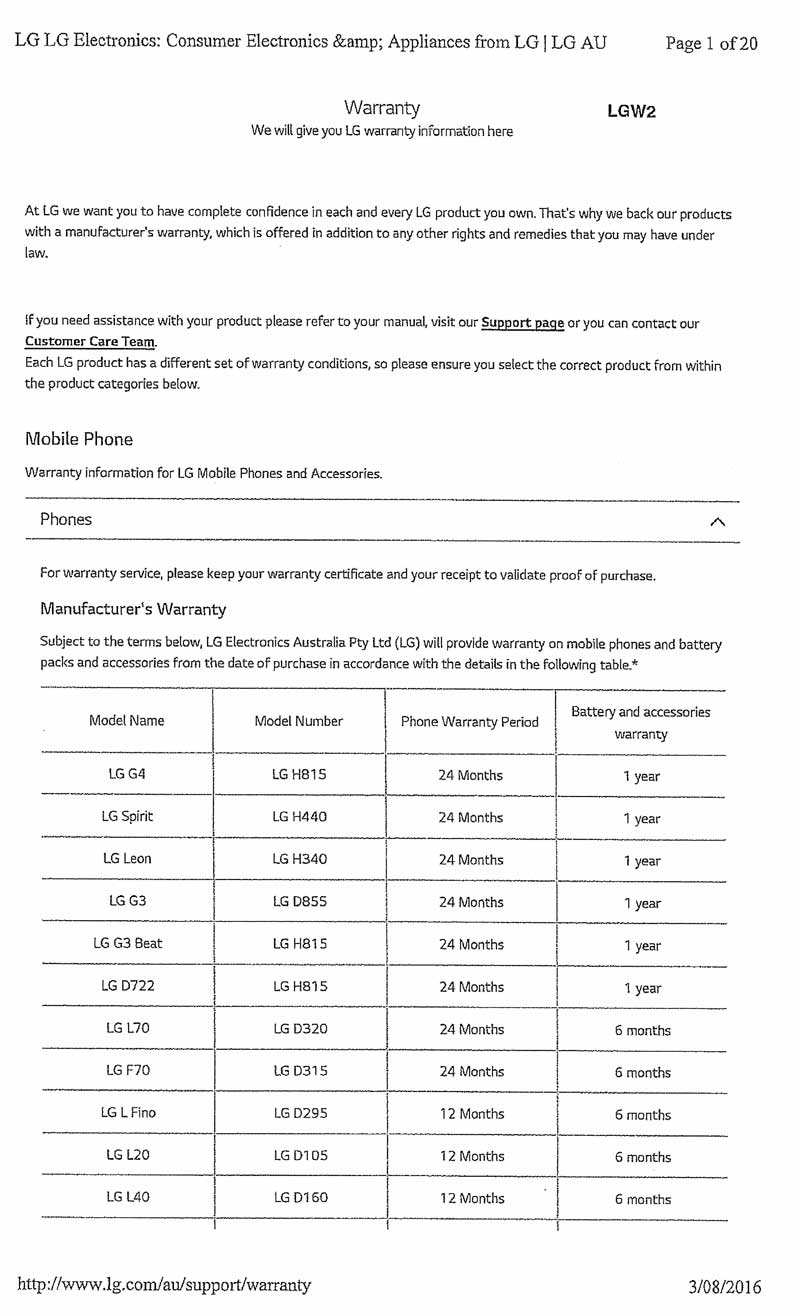

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | LG ELECTRONICS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 1 September 2017 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. Unless any party notifies the Court in writing within seven days that it desires to contest this order as to costs, the Applicant pay the Respondent’s costs to be taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MIDDLETON J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding, the applicant (‘ACCC’) seeks declarations, injunctive relief, pecuniary penalties, disclosure orders, adverse publicity orders and compliance program orders against LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd (‘LG’). This relief is sought under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and ss 224, 232, 246 and 247 of the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’), consisting of Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘CCA’).

2 In summary, the ACCC alleged that LG had engaged in misleading conduct in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL. The ACCC claims that LG had misled consumers, retailers and repairers as to the applicability of the ACL in circumstances where LG’s goods were eventually found to be defective.

3 Each of the relevant consumers in this proceeding had purchased a LG television which subsequently experienced a defect after the expiry of the warranty provided by LG (the ‘LG warranty’). The ACCC alleged that LG had communicated with those consumers, retailers and repairers as though the LG warranty was the only source of their rights in relation to the defects, whilst refraining from making any express reference to the ACL. The ACCC claimed that this was a misleading “half-truth” in light of the fact that the ACL provided consumers with certain rights in respect of defective goods (namely, the consumer guarantees in Div 1 of Pt 3-2) (‘consumer guarantees’).

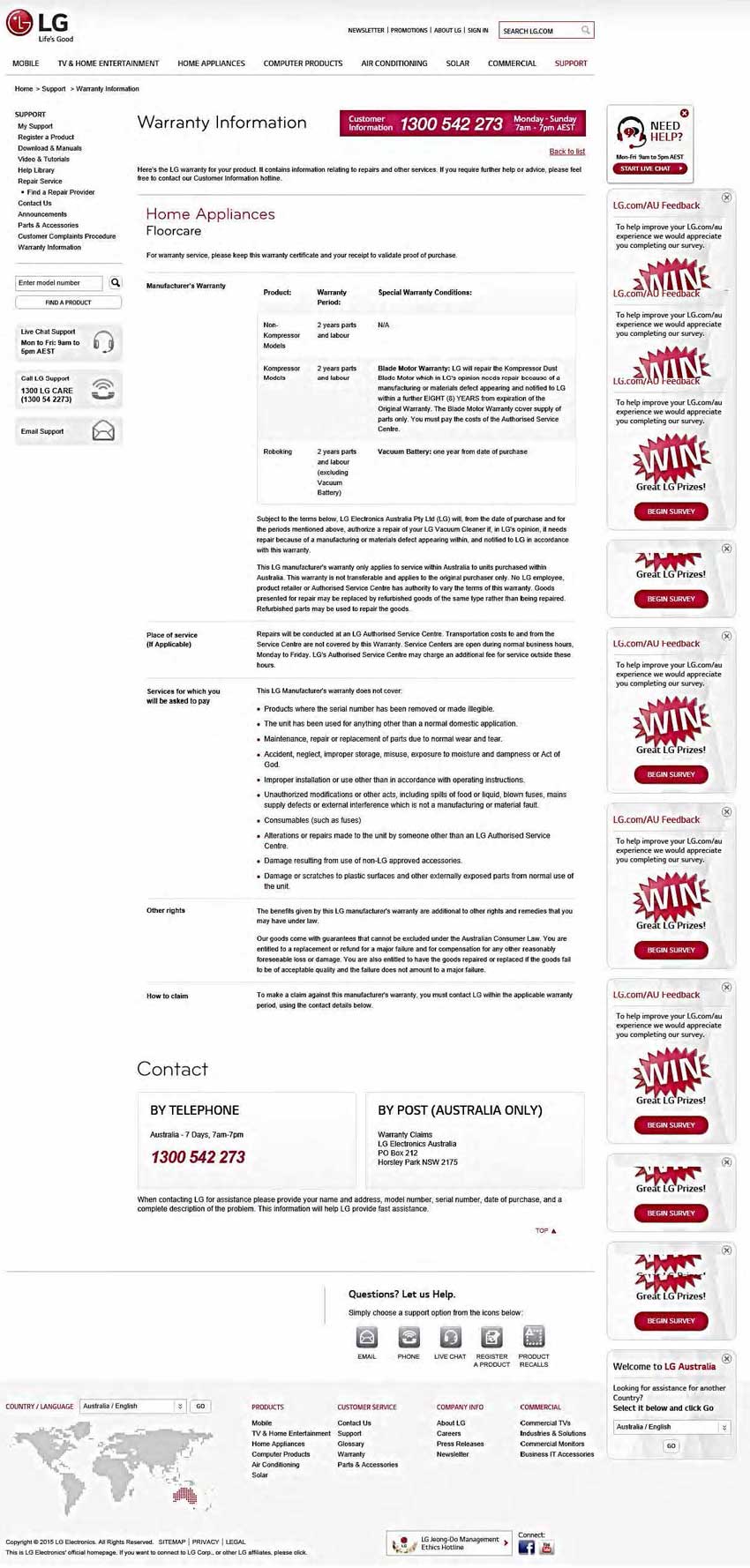

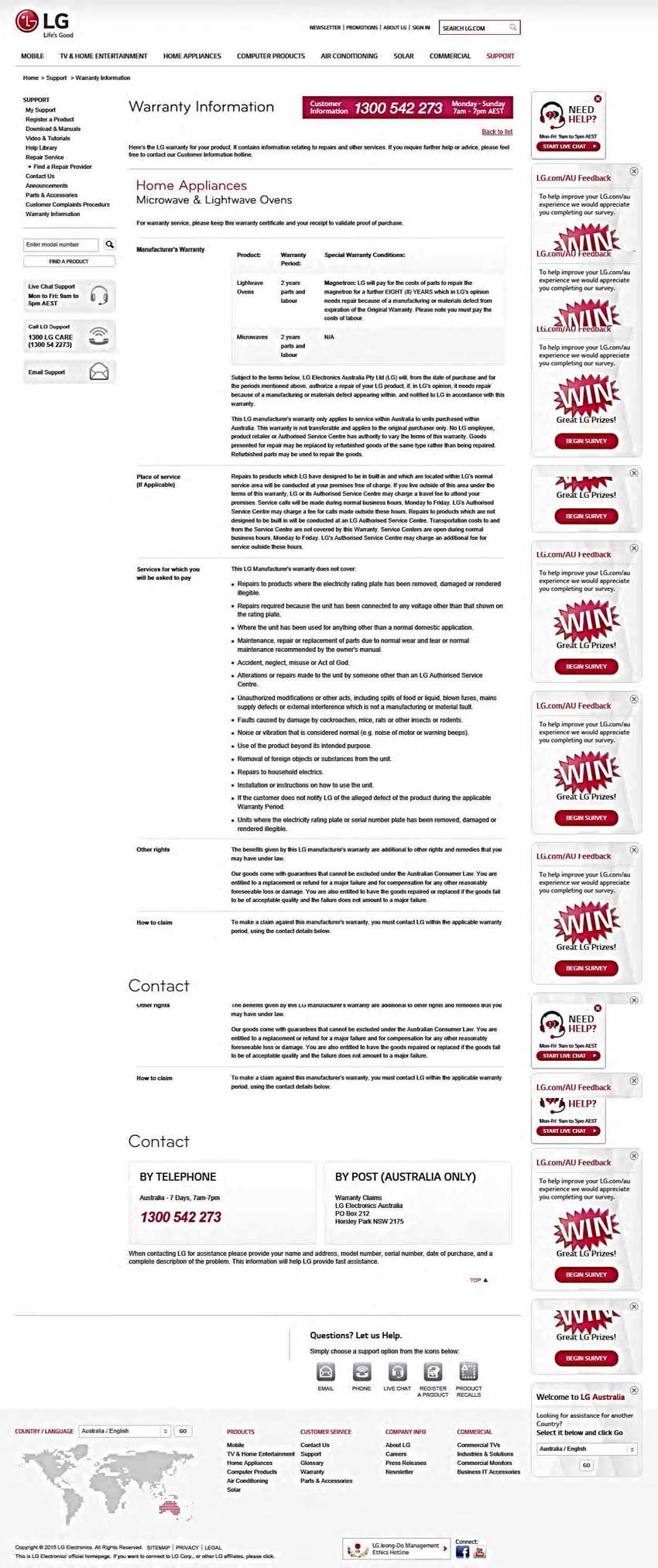

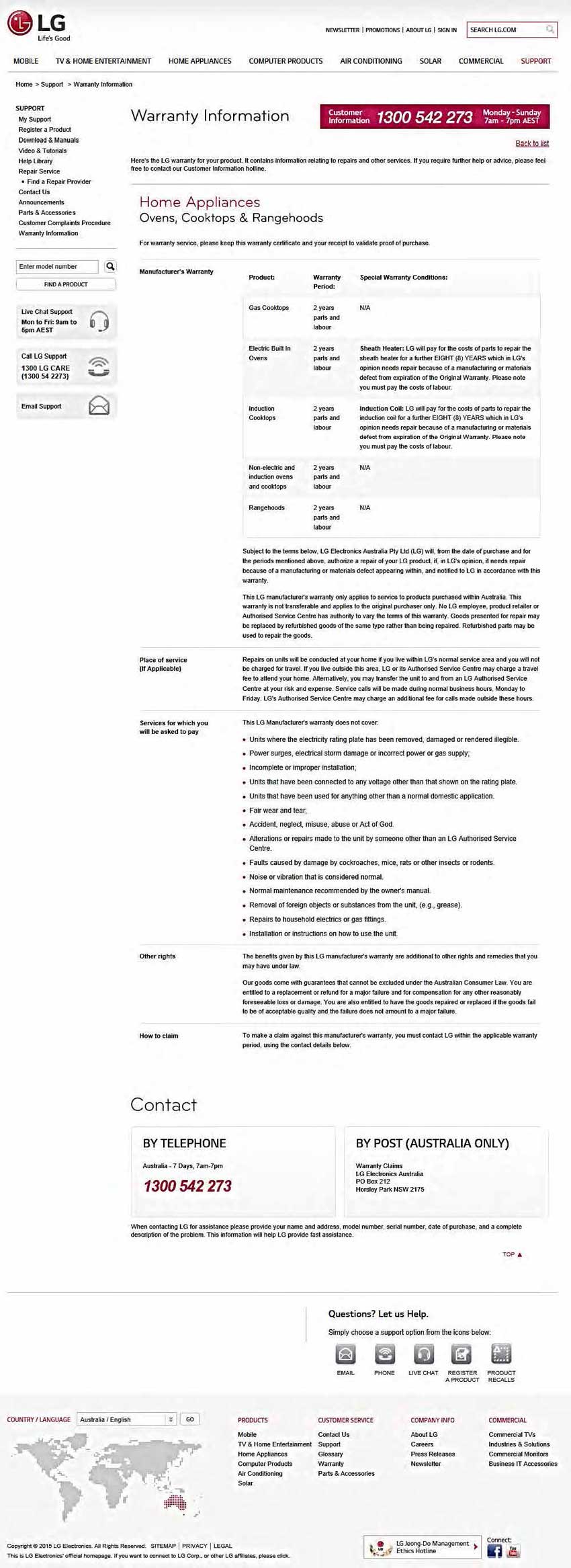

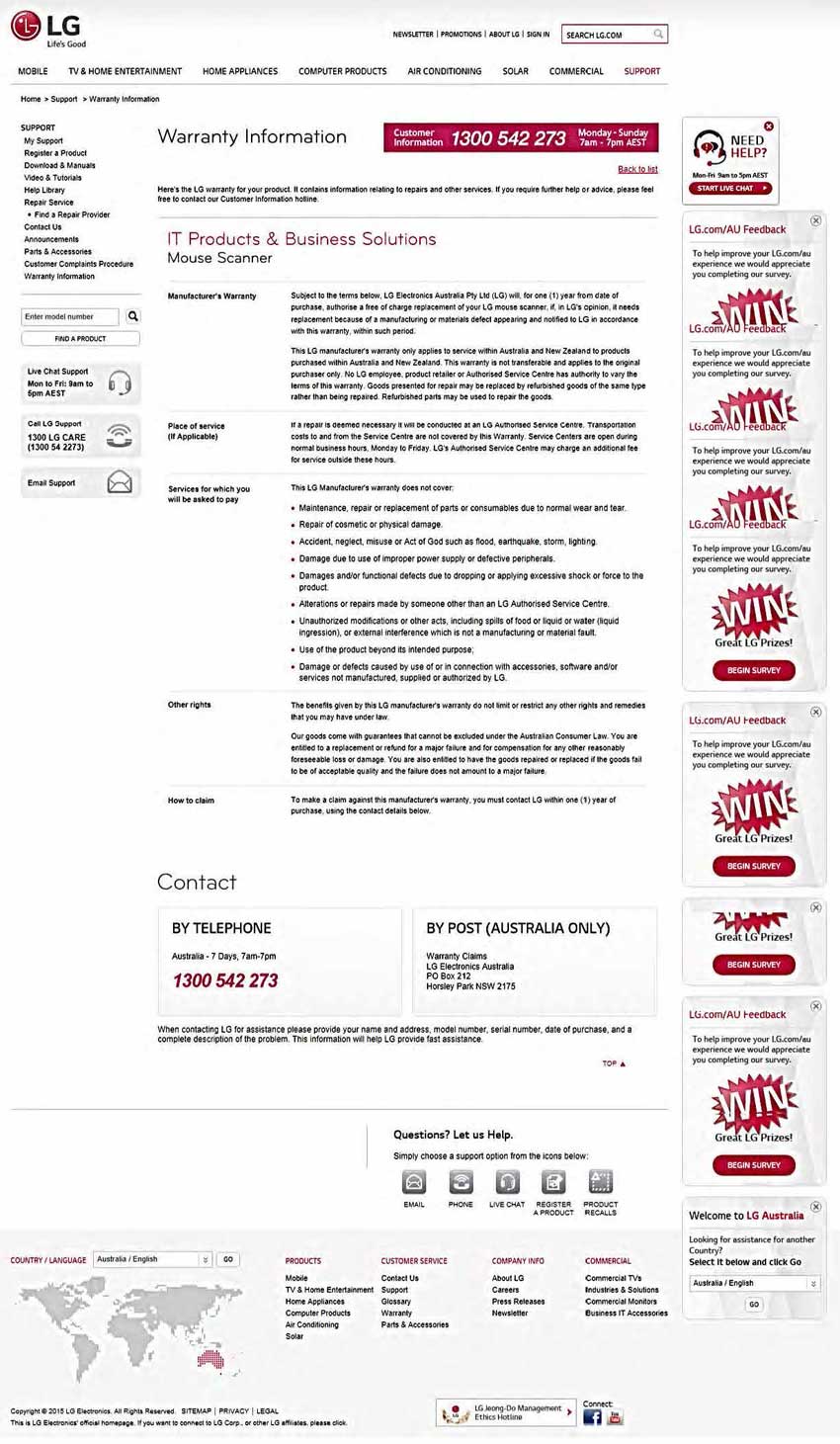

4 The ACCC also alleged that LG had engaged in misleading conduct by communicating this same half-truth through the text displayed on its website.

5 This proceeding is not the occasion to discuss the interplay of corporate morality, community expectations and the law. Nor is this a proceeding to call upon principles of morality to extend the law in relation to the liability of manufacturers to consumers, as famously Lord Atkin did in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 at 580. However, even Lord Atkin in the same speech appreciated that there is a difference between the scope of moral wrongdoing and that of legal liability. Whatever view a person may have as to the appropriateness of LG’s behaviour as alleged in this proceeding in the context of generally assisting aggrieved customers, this is not the issue before the Court. The only matter the Court ultimately needs to determine is the legal liability of LG as alleged in this penalty proceeding by the ACCC.

6 The relevant facts and the context of the communications made by LG are essentially not in dispute. The Statement of Agreed Facts and relevant texts of the website are attached to these Reasons. Apart from the Statement of Agreed Facts relied upon by the parties, and the documentation referred to (which is not in contest), the evidence given by way of affidavit and cross-examination (subject to some qualification) does not raise any issues of credit or relevant factual disputation. The main qualification relates to the expert evidence relied upon by the parties, to which I will return.

7 It is the characterisation of each communication, in the context of the pleaded case, that needs to be considered by the Court. Putting aside the allegations relating to the website, the purpose of the approach made by each consumer to LG (either directly or indirectly) is a starting point for determining the reasonable expectations of that consumer. I stress that the emphasis is on “reasonable expectations”, as distinct from any general desire on the part of a consumer to be provided with assistance from LG.

8 There is no direct evidence that any of the consumers asked to be advised of their rights generally. Communications were made with a call centre (not an information centre) of LG for the purpose of asking LG for assistance. The responses by LG should be viewed in light of that purpose to the extent known by LG and the actual enquiry made by the consumer and communicated to LG. It is not alleged that LG had a responsibility to volunteer information to consumers and advise generally about the ACL, unless to not do so would amount to a half-truth in the various ways alleged in this proceeding. If, for instance, a specific enquiry was made to LG by a consumer as to his or her legal rights in relation to a faulty LG television, then if LG decided to respond, it would be a half-truth to only refer to the LG warranty. On the other hand, if a very specific enquiry was made by a consumer only concerning the LG warranty or asking for a TV to be replaced or repaired, I would not consider a confined response to that specific enquiry to be misleading even if no mention was made of the ACL. It thus seems to me that in relation to each consumer the issue is to determine the correct characterisation of the relevant communications, taking into account the context of these communications.

9 The pleadings of the ACCC refer to various individual statements made by various representatives of LG, each one alleged in essence to be a half-truth, and to that extent misleading. There can be a danger in this approach. It is important to look at each statement in the context of the other statements made by the LG representatives, in addition to the queries raised by each consumer. Therefore, whilst the Court has considered each pleaded representation as presented by the ACCC, it has not considered each representation in isolation. A similar approach was taken by Moshinsky J in Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v The Good Guys Discount Warehouses (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 334 ALR 600 at [159]-[160] (‘Good Guys’).

10 It is also important to remember that this is not a proceeding alleging unconscionable conduct on the part of LG. LG was entitled to consider any claim made by a consumer on the terms it was made, and to require that the claim be substantiated. It should not be forgotten that LG offered assistance to the consumers even though the LG warranty had expired. Admittedly, that assistance was given by LG even though LG knew that the ACL may have provided that consumer with another legal remedy, or LG may have had a possible obligation to act in a particular way to a consumer under the ACL.

11 It also may have been a simple matter for LG to inform consumers of their ACL rights, or even good corporate practice. Nevertheless, these are not relevant considerations in the determination of the issues raised in this proceeding. Whilst the relevant provisions of the ACL alleged to have been contravened by LG in this proceeding establish a “norm of conduct” with which corporations must comply, it is essential to focus attention on the conduct of the alleged wrongdoer, and determine whether that conduct was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive.

APPLICABLE lAW

12 As I have indicated, the ACCC’s pleaded case alleges that LG engaged in multiple contraventions of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL by making certain representations to consumers, retailers and repairers about their rights under the ACL. It is useful to first consider the operation of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) before turning to a consideration of a consumer’s rights under the ACL.

Misleading and deceptive conduct – s 18 and s 29(1)(m)

13 Section 18 contains the following text:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

14 Section 29(1)(m) contains the following text:

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(m) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3-2); …

General principles relating to misleading conduct and representations

15 Whether or not particular conduct is misleading is a question of fact to be determined having regard to the context in which the conduct takes place and the surrounding facts and circumstances: Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202. Conduct will be misleading or deceptive if it induces or is capable of inducing error, taking into account the effect of the conduct as a whole: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (‘Parkdale’) at 198-9; see also Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1572 at [63].

16 Whether a representation was made, and if it was made, whether it constituted contravening conduct, is to be assessed objectively looking at the conduct as a whole: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [38]-[39]; see also Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd v .au Domain Administration Ltd (2004) 139 FCR 215 at [17]. When the question is whether conduct has been likely to mislead or deceive it is unnecessary to prove anyone was actually misled or deceived: Parkdale at 198; see also Good Guys at [211]. However, (whilst not directly relevant to this proceeding) conduct is unlikely to be causative of loss if it does not actually mislead or deceive: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [25]-[29] (‘Campbell’).

17 In relation to the differences between s 18 and s 29, Gordon J concluded there was no relevant distinction between the phrases “misleading or deceptive” on the one hand and “false or misleading” on the other: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]; see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [40] per Allsop CJ. Furthermore, in terms of s 29, the word “representation” is interpreted broadly and includes a statement, made orally or in writing or by implication from words: Given v Pryor (1979) 39 FLR 437 at 441.

Reasonable expectations of disclosure

18 The ACCC’s submissions sought to establish support for the following proposition: in circumstances where there is a reasonable expectation of disclosure of particular information, non-disclosure of that information can be characterised as misleading or deceptive.

19 The case of Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 357 (‘Miller’) involved misleading and deceptive conduct by silence (under the predecessor section, s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)). French CJ and Kiefel J made the following observations about “reasonable expectations” at [19]-[20]:

The language of reasonable expectation is not statutory. It indicates an approach which can be taken to the characterisation, for the purposes of s 52, of conduct consisting of, or including, non-disclosure of information. That approach may differ in its application according to whether the conduct is said to be misleading or deceptive to members of the public, or whether it arises between entities in commercial negotiations. An example in the former category is non-disclosure of material facts in a prospectus.

In commercial dealings between individuals or individual entities, characterisation of conduct will be undertaken by reference to its circumstances and context. Silence may be a circumstance to be considered. The knowledge of the person to whom the conduct is directed may be relevant. Also relevant, as in the present case, may be the existence of common assumptions and practices established between the parties or prevailing in the particular profession, trade or industry in which they carry on business. The judgment which looks to a reasonable expectation of disclosure as an aid to characterising non-disclosure as misleading or deceptive is objective. It is a practical approach to the application of the prohibition in s 52.

20 Apart from the allegations concerning the website, this is a proceeding concerning conduct directed to various individuals. The conduct is to be assessed keeping in mind the specific instances and context of the alleged wrongful conduct. On this basis, relevant factors that inform an understanding of what might constitute “reasonable expectations” as referred to in Miller in a particular scenario include:

the circumstances and context of the conduct;

the knowledge of the person to whom the conduct is directed (at least to the extent it relates to the content, context and circumstances of the conduct);

the existence of common assumptions and practices established between the parties; and

the existence of common assumptions and practices prevailing in the particular profession, trade or industry.

21 However, in Miller their Honours were careful to note that the notion of “reasonable expectations” must remain tethered to the concept of misleading or deceptive conduct as proscribed by the words of the statute (at [21]):

To invoke the existence of a reasonable expectation that if a fact exists it will be disclosed is to do no more than direct attention to the effect or likely effect of non-disclosure unmediated by antecedent erroneous assumptions or beliefs or high moral expectations held by one person of another which exceed the requirements of the general law and the prohibition imposed by the statute. In that connection, Robson A-JA in the Court of Appeal spoke of s 52 as making parties “strictly responsible to ensure they did not mislead or deceive their customer or trading partners”. Such language, while no doubt intended to distinguish the necessary elements of misleading or deceptive conduct from those of torts such as deceit, negligence and passing off, may take on a life of its own. It may lead to the imposition of a requirement to volunteer information which travels beyond the statutory duty “to act in a way which does not mislead or deceive”.

22 Similar comments were made by White J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1369 at [264]:

the test of reasonable expectation is not satisfied by an appeal to “vague and general notions of fairness or some concept of optimal disclosure”. Some principled basis for the reasonable expectation must be identified. Any duty by AGL to disclose information, and any reasonable expectation by consumers that it would disclose information, must have its origin in matters which are independent of the ease of the means by which the duty can be discharged or the expectation satisfied, if it exists.

23 I make one other observation on the context and circumstances that need to be considered. As indicated in Miller, the knowledge of the person to whom the conduct is directed may be relevant as one of the matters to take into account in considering the content, context and circumstances of the impugned conduct. The awareness of the entity said to have been engaged in the impugned conduct of that person’s knowledge will also be relevant as a circumstance to take into account in considering the impugned conduct. Of course, conduct may be misleading even if a person is not misled, and even if there is no loss or damage caused by the conduct. In this regard, it is not necessary and would be an irrelevant enquiry (in this proceeding) to consider the effect of the conduct on the consumers: see Campbell at [25]-[29] per French CJ and Good Guys at [211] per Moshinsky J.

Representations as to applicable obligations

24 It is apparent from a number of recent decisions that representations which do not reflect the representor’s possible obligations arising under the consumer guarantee provisions may contravene s 29(1)(m) (and s 18) of the ACL – although I note that the contraventions in the following proceedings were admitted in each instance: see, eg Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hewlett-Packard Australia Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 653; Australian Consumer and Competition Commission v Salecomp Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1316; Australian Consumer and Competition Commission v HP Superstore Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1317; and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chopra [2015] FCA 539.

25 The recent decision of Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bunavit Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 6 also involved admitted contraventions. However, Dowsett J made some pertinent statements in relation to denials of liability at [29]:

Obviously enough, broad denials of liability by a supplier may mislead a consumer as to his or her rights. Even if such conduct does not have that effect, it may lead the consumer to conclude that persistence will involve too much trouble, with too little assurance of a satisfactory outcome.

26 However, his Honour expressed some concerns about the approach adopted by the parties in that particular case. The supplier had admitted that its statements that it owed no particular obligations to a consumer seeking redress were misleading because (as the parties accepted) the supplier “could” have owed or “possibly” owed those obligations. Despite the parties’ agreement in this respect, his Honour considered that their understanding as to what constituted misleading conduct was problematic. His Honour considered that if he were to grant declaratory relief in that form, such a statement of the law might (continued at [29])

cause considerable difficulty in day-to-day dealings between retailers and consumers. There will, from time to time, be unjustified claims for repair, replacement or refund. It would be unfair, and therefore unwise, to penalise a retailer for a bona fide denial of liability which later turns out to be wrong. That approach might lead a retailer to concede liability where none exists. Such statements will usually be oral and, on many occasions, imprecise. A denial of liability may be couched in ambiguous terms, in that it may be expressed and/or understood as relating to either the case in hand or to the general extent of the retailer’s liability.

27 His Honour later expanded upon his concerns whilst noting the “curiosity of the alleged misconduct” (at [34]):

I do not fully understand how a statement of opinion as to a possible obligation, a mixed question of law and fact, can be demonstrably false, misleading or deceptive simply because the relevant party “could” be obliged to provide certain remedies, or might “possibly” have had an obligation to do so. The proposition seems to assume that a statement that there is no obligation is false, misleading or deceptive if there may be such an obligation, in some unspecified circumstances, not necessarily related to the present case, or only possibly related to it.

28 These preceding paragraphs have considered the general principles in relation to misleading conduct, the concept of a reasonable expectation of disclosure, and recent case law in relation to a supplier denying liability. Despite this analysis, I note that one is limited in the extent to which the concept of misleading conduct can be unpacked. As Black CJ noted in Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky (1992) 39 FCR 31 at 32, regardless of the idiosyncrasies of a particular case:

the question is simply whether, having regard to all the relevant circumstances, there has been conduct that is misleading or deceptive or that is likely to mislead or deceive.

Consumer rights under the ACL

29 The consumer guarantees in Div 1 of Part 3-2 of the ACL include, relevantly for this proceeding, a guarantee that if a person supplies goods to a consumer in trade or commerce, those goods will be of acceptable quality: s 54 (the ‘guarantee as to acceptable quality’). The phrase “acceptable quality” is further defined in s 54(2) and s 54(3):

(2) Goods are of acceptable quality if they are as:

(a) fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied; and

(b) acceptable in appearance and finish; and

(c) free from defects; and

(d) safe; and

(e) durable;

as a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods), would regard as acceptable having regard to the matters in subsection (3).

(3) The matters for the purposes of subsection (2) are:

(a) the nature of the goods; and

(b) the price of the goods (if relevant); and

(c) any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods; and

(d) any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods; and

(e) any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods.

30 The consumer guarantees cannot be restricted, modified or excluded by contract: s 64.

Actions against suppliers

31 If a consumer guarantee is breached, the entitlements of the person to whom the goods were supplied will vary depending on the circumstances. Section 259 of the ACL sets out the following remedies:

259 Action against suppliers of goods

(1) A consumer may take action under this section if:

(a) a person (the supplier ) supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to the consumer; and

(b) a guarantee that applies to the supply under Subdivision A of Division 1 of Part 3-2 (other than sections 58 and 59(1)) is not complied with.

(2) If the failure to comply with the guarantee can be remedied and is not a major failure:

(a) the consumer may require the supplier to remedy the failure within a reasonable time; or

(b) if such a requirement is made of the supplier but the supplier refuses or fails to comply with the requirement, or fails to comply with the requirement within a reasonable time--the consumer may:

(i) otherwise have the failure remedied and, by action against the supplier, recover all reasonable costs incurred by the consumer in having the failure so remedied; or

(ii) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection.

(3) If the failure to comply with the guarantee cannot be remedied or is a major failure, the consumer may:

(a) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection; or

(b) by action against the supplier, recover compensation for any reduction in the value of the goods below the price paid or payable by the consumer for the goods.

(4) The consumer may, by action against the supplier, recover damages for any loss or damage suffered by the consumer because of the failure to comply with the guarantee if it was reasonably foreseeable that the consumer would suffer such loss or damage as a result of such a failure.

(5) Subsection (4) does not apply if the failure to comply with the guarantee occurred only because of a cause independent of human control that occurred after the goods left the control of the supplier.

(6) To avoid doubt, subsection (4) applies in addition to subsections (2) and (3).

(7) The consumer may take action under this section whether or not the goods are in their original packaging.

32 The term “major failure” is defined in s 260. Section 261 sets out how suppliers may remedy a failure to comply with a guarantee where the failure is not a major failure. Section 262 sets out when consumers are not entitled to reject goods, and s 263 sets out the consequences of a consumer rejecting said goods.

Actions against manufacturers

33 In relation to the guarantee of acceptable quality, s 271 of the ACL provides that an affected person in relation to goods that are not of acceptable quality (see s 54) may, by action against the manufacturer of the goods, recover damages from the manufacturer. Section 274 also provides for the indemnification of suppliers in certain circumstances where they are not responsible for the failure to comply with a consumer guarantee.

Overall position in relation to suppliers and manufacturers

34 Without setting out all the provisions of the ACL, the position as to the obligations of suppliers and manufacturers under the ACL is as follows.

35 In the event of a major failure of a good, the consumer is only entitled to a remedy against:

(1) the supplier if, pursuant to s 259(3) and s 259(4) of the ACL:

(a) the consumer notifies the supplier that they reject the goods and of the grounds of rejection and (pursuant to s 263) the consumer returns the goods to the supplier unless they have been already returned or such return would involve significant cost – unless one of the circumstances set out in s 262 applies in which case the consumer is not entitled to reject the goods; or

(b) the consumer takes action against the supplier for compensation for a reduction in the value of the goods below the price paid or payable and for any loss and damage that was reasonably foreseeable; and

(2) the manufacturer, pursuant to s 271 of the ACL, such remedy being limited to an entitlement to recover damages by bringing an action against the manufacturer, if:

(a) the consumer is affected by a failure to comply with a consumer guarantee under the ACL; and

(b) the exemptions in s 271(2) and s 271(4) do not apply.

36 However, in the event that the consumer has required the goods to be repaired or replaced in accordance with an express manufacturer’s warranty, then the consumer is not entitled to commence an action against the manufacturer unless the manufacturer has not remedied the failure within a reasonable time.

37 It is clear that there are specific remedies provided for in the ACL which a consumer might have against the supplier but not against the manufacturer. I should mention that s 272 of the ACL does not provide for a remedy against a manufacturer but provides for the measure of damage which the consumer can claim against the manufacturer in the event that the consumer is able to take action against the manufacturer under s 271.

38 The onus of proving that the good has suffered a major failure, or there is otherwise a breach of one of the consumer guarantees, is on the person making the allegation. There is no prohibition under the ACL, or otherwise, on a manufacturer requiring that a consumer prove or demonstrate or (at first instance) pay for an assessment or test which might prove or demonstrate the nature and cause of the defect alleged where the nature or cause of the defect is otherwise not known.

FURTHER PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS

39 It is useful to make some further preliminary observations and summarise some relevant matters already touched upon applicable to all the allegations and which form the basis of my later considerations:

(1) The LG televisions came with an ACL consumer guarantee as to acceptable quality, which includes a criterion of durability.

(2) In respect of a good failing to be of acceptable quality, the ACL does not prevent a requirement being imposed by LG that the consumer pay costs associated with the assessment or repair of the goods (at the first instance).

(3) The consumer guarantee as to acceptable quality cannot be excluded, restricted or modified by contract.

(4) The consumer guarantee as to acceptable quality is not limited by the period of any express warranty offered by a supplier.

(5) The ACL does not prohibit the taking of action by a consumer under s 259 or s 271 after the express manufacturer’s warranty has expired.

(6) This proceeding is not about the responsibility of LG to inform or generally advise the public about consumer entitlements. This proceeding does not contain allegations that the behaviour of LG was intended to discourage or had the effect of discouraging consumers from enforcing their rights or as involving high pressure tactics to force or encourage consumers to accept an inappropriate remedy. This proceeding also does not involve the allegation that there was an independent obligation on LG to make full disclosure of all material facts, or that the communications were made in bad faith, or that there was an independent duty of full and frank disclosure of material facts and instances relevant to the consumer weighing up a proposal put by LG. Nor is this a proceeding where the ACCC alleges that LG made baseless representations to induce the consumer into accepting its offer, or a deliberate refusal to acknowledge the issues which were the subject of a consumer’s claims.

(7) This proceeding does not involve any allegations of unconscionable conduct. Specifically, this proceeding does not concern any allegation that LG engaged in a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour that was unconscionable in contravention of s 21 of the ACL.

(8) Where LG communicated with repairers and retailers, it was the intent of LG that the information contained in that communication would be passed on to the relevant customers.

(9) To the extent LG did engage with specific consumers, either directly or indirectly, the significance of them not mentioning the existence of rights under the ACL and their possible availability must be considered in the context of that engagement.

(10) Retailers in particular – and to the extent I explain later, consumers – would be aware of the ACL, and this is relevant as part of the context and content of LG’s conduct. It is important to recall that this is a penalty proceeding, and the Court must be satisfied to the degree of proof necessary keeping in mind s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

(11) The evidence indicates that LG, in receiving an assessment report from an authorised dealer on a faulty LG TV, would assume, unless otherwise expressly indicated, that the fault with the relevant TV was not obviously caused by installation or the customer. Otherwise, the assessment reports did not indicate the cause of the fault.

CONSIDERATION

40 The ACCC’s pleaded case involved a considerable number of different alleged contraventions in relation to a variety of persons. As such, it is important to establish a coherent structure for my analysis of the facts. I will do so by having regard to the structure adopted by the ACCC in its pleaded case. However, as I have indicated, no one pleaded representation or statement can be viewed in isolation.

41 The ACCC’s pleaded case can be viewed as being in two parts. First, the ACCC alleges that LG contravened s 18 and s 29(1)(m) by making various representations when communicating with specific consumers, retailers and repairers. Secondly, the ACCC alleges that LG contravened those provisions by making representations to the world at large via the content displayed on its website. Whilst this second part of the case is relatively confined, the first part of the case involves a consideration of many different representations alleged to have been made by LG to many different consumers, retailers and repairers. Because of this, I intend to organise my consideration of those representations, and will do so by reference to each of the seven LG televisions purchased by the relevant consumers. For each of the seven LG televisions, with the qualification I have mentioned of viewing the conduct in context, I will consider whether the alleged representations of LG in relation to those televisions were misleading pursuant to s 18 or s 29(1)(m).

42 Therefore, I will use the following headings to structure my forthcoming analysis:

(1) Television purchased by SS and CS.

(2) Television purchased by CW.

(3) Television purchased by JF.

(4) Television purchased by MM.

(5) Television purchased by PG and MG.

(6) Television purchased by RH.

(7) Television purchased by DW and SW.

43 I will use the following heading for my analysis of the second part of the ACCC’s case regarding representations said to have been made via content displayed on LG’s website:

(8) The content displayed on LG’s website.

44 Throughout these Reasons I will also make use of the convenient shorthand used by the ACCC to describe the various types of representations made by LG. These were (collectively, the ‘ACL Representations’):

Assessment Cost Representation – a representation by LG that when a LG good had any defect after the expiry of the LG warranty, the consumer was only entitled to a remedy if the consumer paid for the costs of assessing the failure.

Limited Warranty Representation – a representation by LG that the remedies available in respect of the failure of LG goods which had any defect were limited to the LG warranty.

Goodwill Representation – a representation by LG that when a LG good had any defect after the expiry of the LG manufacturer’s warranty, LG had no further obligations with respect to the LG good, and any step it took in relation to the LG good was an act of goodwill.

Repair Only Representation – a representation by LG that when a LG good had any defect after the expiry of the LG manufacturer’s warranty, the consumer was only entitled to have that good repaired, regardless of the nature of the defect.

Labour Cost Representation – a representation by LG that when a LG good had any defect after the expiry of the LG manufacturer’s warranty, the consumer was liable for the labour costs of the repair.

45 However, there are risks involved in relying on generic, second-hand characterisations of specific conduct. Therefore, whilst these shorthand labels are convenient, they will not comprise a substitute for analysis of the specific facts in relation to each alleged contravention. Further, as will become apparent, whilst each ACL Representation is alleged separately, in essence the central complaint of the ACCC can be (and should be) dealt with taking all the individual ACL Representations in context. Taking into account the evidence relied upon by the ACCC (which in some respects were the notes of conversations), isolated references to one or two words, or even sentences, should be treated with caution, when the task is to view LG’s conduct in context.

46 I observe that the ACCC put the overall context of the representations in closing submissions as follows:

The context for the communications in 2014 was that:

a. a consumer had purchased an LG television (LGTV);

b. the TV had developed a fault shortly after the period of the express LG Manufacturer’s Warranty (LG Warranty);

c. in each case, the fault rendered the LGTV effectively unusable and was a ‘major failure’ as that term is defined under the ACL;

d. the consumer had contacted LG about the defect seeking a solution;

e. the LGTV was assessed by an authorised LG repairer who had determined what component had failed, and in no instance assessed the fault as having been caused by the consumer;

f. the ACL consumer guarantee as to acceptable quality applied to the LGTVs;

g. LG knew the ACL consumer guarantee applied to the TVs and that the consumers had or may have had rights by reason of it;

h. LG approached its communications with the consumer on the basis that unless the consumer raised the ACL, it was not invoked and/or not applicable; and

i. LG consciously communicated with the consumers as if the only relevant matter was the LG warranty itself.

(Original emphasis.)

47 I accept these submissions, with these following important and significant qualifications and observations.

48 In relation to the rights under the ACL pertaining to each relevant customer, all that can be said on the evidence is that the customer may have had the ability to seek damages against LG, or relief against a supplier. It is not possible to conclude, in relation to each relevant customer, whether LG or a supplier were legally liable to any of the relevant customers. In any event, this is not the approach I understood the ACCC to be taking in this proceeding, namely to undertake the task of demonstrating such a liability existed in fact. The ACCC, in different formulations, sought to place responsibility upon LG for falsely representing that the only relevant source of a consumer’s rights was the LG warranty. The ACCC in its closing outline of submissions, in discussing the reasonable expectations of consumers, stated as follows:

This reasonable expectation did not arise only where a consumer had demonstrated that the LG good had a major or minor failure to comply with the consumer guarantee, or where a consumer had made a claim for relief under those provisions. It applied in any circumstance where the consumer, or a retailer or repairer, had made enquiries of LG as to a potentially defective good, where the consumer guarantees might potentially have application.

(Original emphasis.)

49 As the ACCC further submitted, the false and misleading conduct alleged against LG could have been prevented if (for instance) LG said: “The Australian Consumer Law applies to these goods and you may have rights to a refund, repair or replacement by reason of its application” (or words to that effect). Alternatively, the ACCC submitted that LG could have made a statement in line with reg 90(2) of the Competition and Consumer Regulations 2010 (Cth) (the ‘Regulations’), which provided:

‘Our goods come with guarantees that cannot be excluded under the Australian Consumer Law. You are entitled to a replacement or refund for a major failure and compensation for any other reasonably foreseeable loss or damage. You are also entitled to have the goods repaired or replaced if the goods fail to be of acceptable quality and the failure does not amount to a major failure’.

50 I observe that this is a requirement under s 102(2)(a) of the ACL, which (as the parties accepted) does not apply in terms to LG and the instances relating to this proceeding.

51 It can be accepted that LG approached its communications with the consumers on the basis that faults occurring outside the manufacturer’s warranty period were probably not manufacturing defects. Whether this is a correct assumption or not, LG was entitled to require a consumer to satisfy LG that a claim was accurate and substantiated. Even if a claim was made under the ACL, LG would have been entitled to accept or reject the claim, taking the consequences for either approach. LG would have been entitled to ask a consumer to substantiate a claim. Undoubtedly the evidence of Catherine Warwood, acting supervisor of LG’s Direct Dealer Support Team (the ‘DDS team’) (which was responsible for dealing with queries from retailers of LG products across Australia), indicated a perhaps uninformed approach to the application of the ACL. It may also be that the offers made by LG had no regard to the LG warranty – however, this is not the subject of allegations against LG. This is not a proceeding about the internal processes of LG in dealing with consumers, or to examine the factors or considerations LG or the DDS team took into account in considering a claim; nor is this a proceeding that investigates whether the communications with the retailers or consumers involved bona fide offers of assistance or ex gratia payments.

52 It was accepted by the ACCC that LG, in response to a claim made to it, could have simply referred consumers to retailers, or if a consumer approached a retailer, LG could have asked the retailer to deal with the consumer. The gist of the ACCC’s allegations is that since LG ‘entered the fray’ (as LG did), LG’s conscious decision not to mention the ACL was a half-truth as the implication was that the only relevant source of a consumer’s rights was the manufacturer’s warranty: by consciously omitting to mention the ACL in the context of the consumer’s requests, LG made a representation as to the non-existence of a consumer’s rights outside the manufacturer’s warranty.

53 It can readily be accepted that a half a truth may be worse than a blatant lie. A half-truth may beguile the receiver of the half-truth into a false sense that he or she is receiving the whole truth and nothing but the truth – and hence is under the understanding, and reasonable and legitimate expectation, that the person giving the information is presenting all the information necessary for the recipient to act accordingly.

54 In the area of prospectus disclosure, where there is a duty of full disclosure, Lord Macnaghten in Gluckstein v Barnes [1900] AC 240 at [250]-[252] (‘Gluckstein’), whilst not going so far as I have just indicated, bespoke of the dangers of half a truth in the following terms:

My Lords, it is a trite observation that every document as against its author must be read in the sense which it was intended to convey. And everybody knows that sometimes half a truth is no better than a downright falsehood. Is the statement in the prospectus which I have just read as to the price which the vendors had to pay for the property true or false? In the letter it is true. The vendors had bid 140,000l. for the property, and had formally agreed to pay that sum for it. But for all that, the sum of 140,000l. was not the sum they were going to pay, and they knew that well enough. They had provided themselves with counters, obtained at little cost, which in reckoning the price would be taken, as they knew, at their face value, so that the price of the property to them would be only about 120,000l. Is that what Mr. Gluckstein and his associates meant the public to understand? Surely ordinary persons reading the prospectus, and attracted by the hopes of profit held out by it, would say to themselves, “Here is a scheme which promises well. The gentlemen who are putting the property on the market know something about it, for they were the sole directors and managers of ‘Venice in London,’ which was a very profitable speculation. They have had the whole property valued by well-known auctioneers, who say that it is worth more than is asked for it. True, they secure a profit of 40,000l. for themselves, but then they disclose it frankly, and it is not all clear profit. There is interest to be paid, and all the expense of forming the company. And they have actually agreed to pay 140,000l. down. That sum, they tell us, is ‘payable in cash.’” You will observe those last words, “payable in cash.” Their introduction is almost a stroke of genius. That slight touch seems to give an air of reality and bona fides to the story. Would anybody after that suppose that the directors were only going to pay 120,000l. for the property, and pocket the difference without saying anything to the shareholders? “But then,” says Mr. Gluckstein, “there is something in the prospectus about ‘interim investments,’ and if you had only distrusted us properly and read the prospectus with the caution with which all prospectuses ought to be read, and sifted the matter to the bottom, you might have found a clue to our meaning. You might have discovered that what we call ‘interim investments’ was really the abatement in price effected by purchasing charges on the property at a “discount.” My Lords, I decline altogether to take any notice of such an argument. I think the statement in the prospectus as to the price of the property was deliberately intended to mislead the shareholders and to conceal the truth from them.

55 The position in this proceeding as pleaded by the ACCC is far removed from that which confronted Lord Macnaghten, where his Lordship dealt with a clear duty already existing to disclose the price, such that a half-truth going to that very issue (price) needed to be disclosed.

56 In this proceeding it is important to focus on the relevant conduct of LG having regard to the allegations of the ACCC and the reasonable expectation of each consumer (in the context of their communications), so as to determine whether LG should have disclosed the existence of the ACL and the ‘potential’ remedy available under that statutory provision so as not to mislead or deceive or likely mislead or deceive the consumer. I emphasis ‘potential’ because this is the real complaint made by the ACCC.

57 I am satisfied that all consumers would have received a LG warranty card at the time of purchase (which occurred at least a year before the faults occurred), which made reference to the ACL in line with reg 90(2) of the Regulations. However, I find that on the evidence most (if not all) of the consumers would have had, at the time of communicating about the faulty TVs, only a very general knowledge about the ACL and its existence. Nevertheless in viewing LG’s conduct, it is relevant that all consumers had been informed (as the law required) of the ACL, and LG would have been aware this occurred at least at the time of purchase. Further, LG had no reason to assume that a consumer was not aware of the ACL.

58 I do add by way of some qualification to the above statement, that the communications with some consumers (for example CW, JF, MM, PG, DW and SW) indicate that these consumers had a more immediate or heightened awareness of the effect of the ACL, but not to the somewhat complicated nature of the remedial relief possibly available to them as outlined above in these Reasons by reference to the various statutory provisions. Nevertheless, this state of knowledge by consumers is relevant as part of the content and context of LG’s conduct. So too is the knowledge of retailers; a retailer would be expected to have some knowledge (to different degrees) of the ACL and a retailer’s obligations thereunder. LG had no reason to assume that a retailer was not aware of the ACL.

59 The conscious approach of LG to its communications with the retailer or consumer was to respond to the enquiry in the context of that specific enquiry. By this I mean that unless the ACL was raised, LG would not mention it or bring it to a consumer’s attention. However, there is no evidence that LG knew or was itself aware that consumers were unaware of the existence of the ACL. In some specific instances consumers did know of or mention the ACL in specific terms.

60 Having made these observations, I return to other submissions of the ACCC, where it continued to submit as follows;

Having chosen to engage with those consumers in respect of the faults with their LGTVs, it was required to do so – and there was a reasonable expectation that it would do so – in a way that was not misleading. That meant referring to the ACL.

LG’s communications were, deliberately, entirely focused on the expired LG Warranty as if it were the only repository of consumer rights. The communications denied the existence of the consumer guarantees.

…

LG engaged in a consistent course of conduct, making one or more representations which had the effect of:

a. misinforming or misleading consumers about the applicable consumer guarantees and their rights, or remedies that applied in respect of the goods; and

b. frustrating their attempts to obtain remedies that applied in respect of the goods.

61 It is also useful to make some observations on these submissions. Again the content of the actual communications is important in the context of the pleaded allegations. Further, although submitted by the ACCC, the ACCC does not need to show that the “communications denied the existence of the consumer guarantees”. The pleaded case is merely that LG only represented half the picture as to consumer rights by not referring to the ACL, and this was misleading as tending to indicate to consumers that their only remedy was by recourse to the manufacturer’s warranty (or LG’s goodwill).

62 The reference to LG’s conduct having the effect of frustrating the relevant consumer’s attempt to attain remedies that applied in respect of the TVs was not pleaded, nor is it a necessary component of the allegations made as to the representations and their misleading nature.

63 I will now turn to an analysis using the structure earlier described. However I do not repeat in relation to each separate allegation the findings and observations I have made above. These findings and observations impact upon my characterisation of the conduct of LG in each individual instance as alleged.

Television purchased by SS and CS

Facts

64 On 26 January 2013, SS and CS purchased a LG television for $670 from The Good Guys Joondalup in Western Australia (‘CS television’). At the time of purchasing the television, they were given a LG warranty card which set out their rights under the manufacturer’s warranty and noted that they had other rights including rights under the ACL. The wording is that prescribed by s 102 of the ACL and reg 90(2) of the Regulations. By 9 May 2014, the CS television developed a fault where the right side of the screen was solarised and a different colour. This was assessed by an authorised LG repairer, Perth Digital Pty Ltd, who determined that the CS television had a faulty panel. Perth Digital prepared a quote which described the fault as follows:

FAULT – right side of screen solarized and different colour. then once TV for prolonged period screen sc

…

PANEL IS FAULTY

65 On 1 July 2014, Thai Nguyen of Perth Digital emailed this quote to the DDS team of LG. Nguyen’s email stated: “Customer have asked me to forward this to you and if you would cover this under warranty”. On 8 July 2014, Ms Warwood of LG sent CS an email stating (the ‘CS Statement’):

LG are happy to assist with the cost of Parts Only, labour would be covered by your own cost.

Please let me know if you wish to proceed.

66 On 9 July 2014, CS sent Ms Warwood an email stating: “We would be very happy to proceed. Thank you for your assistance in this matter”. LG subsequently paid the cost of parts for the CS television, whilst CS and SS paid the labour costs for its repair.

The ACCC’s claim

67 The ACCC alleges that in making the CS Statement, LG made both the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to CS, in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL. I do not accept these allegations.

68 It is important to consider the CS Statement in the specific context of the requests. The enquiry only related to the “warranty”. It did not ask for any action by LG other than as to that enquiry. Whilst LG was not accepting liability under the warranty (although this is not made clear in the communication), LG did make an offer by way of a payment they were prepared to make. In the context of the pleaded representations, I do not conclude that LG represented that CS and SS were only entitled to have the TV repaired and were liable for the labour costs of repair. Upon this specific enquiry, LG was under no obligation to otherwise inform the consumer of the existence of the ACL or its availability to their position. On the evidence before the Court, I cannot be satisfied that there was a tendency to lead the relevant consumer into error. I also cannot be satisfied, in the context of the enquiry, there would have been any ‘reasonable expectation’ of disclosure of the nature alleged by the ACCC. The consumer may have been assisted and better informed by being told the ACL was available but this is a different matter. It is not alleged in the pleadings of the ACCC in this proceeding that the rejection of the claim was baseless.

69 I also observe that just because CS and SS were “happy to proceed” does not allow me to draw the inference that they were actually misled. There have been many reasons for their contentment, and their acceptance of the assistance given by LG could have occurred even if they had full knowledge and understanding of the operation of the ACL and its applicability to their circumstances. There is not enough evidence before the Court to conclude that CS or SS were actually misled in the way alleged by the ACCC. Of course, a consumer being actually misled is not a necessary element of the allegations made by the ACCC, although it is a relevant factor to consider in determining whether conduct has a likelihood of being misleading.

Television purchased by CW

Facts

70 On 5 August 2012, CW purchased a LG television for $800 from Rezzie Betta in New South Wales (‘CW television’). At the time of purchasing the television, he was given a LG warranty card which set out his rights under the manufacturer’s warranty and noted that he had other rights including those under the ACL. On about 8 June 2014, the CW television developed a fault in that it had sound but no picture.

71 CW had been in contact with Fair Trading (NSW) before this time, or at least by 10 June 2014, and was probably aware of his statutory rights at a very general level.

72 On 8 June 2014, an unidentified person (whom the parties presumed was CW) spoke to Sheerah Corea of LG regarding the CW television. The customer relationship management record of that conversation stated (the ‘first Third CW Statement’):

advised that the tv is no longer covered in warrantv and we cannot tell if this was an issue related to the old one. since ASC (KUrri) did the repair before it is best to have this evaluated again and asked for the recommendation to have this fix.

explained that theres a lot to considered to what happened to the product (1 vr) after the last repair.

told that he might be liable for the repair cost and advised to get a recommendation forom the ASC for this repair.

73 On 13 June 2014, CW spoke to “User 1 CICAH” of LG, as follows (the ‘second Third CW Statement’):

CUSTOMER INSISTS THAT A NAME GEORGE FROM LG, TOLD HIM THAT HIS PRODUCT CAN ONLY BE CHANGE OVER.

*ADVISED THE CUST. THAT WE CAN DO ONLY CHANGE OVER IF THE PRODUCT STILL IN MANUFACTURER’S WARRANTY AND IF HIS PRODUCT HAS DONE MULTIPLE REPAIRS

74 On 13 June 2014, CW also spoke to Katie Varian of LG. The customer relationship management record includes the following notation in relation to that conversation (the ‘First CW Statement’):

THE CUSTOMER CALLED DDS DIRECTLY WANTING A REPLACEMENT FOR HIS TV.

I ADVISED THE UNIT IS OUT OF WARRANTY AND WILL NEED TO BE ASSESSED FIRST TO CONFIRM IF A MANUFACTURING FAULT. WHICH WOULD BE AT THE CUST EXPENSE. THEN WE COULD POSSIBLY LOOK AT ASSITING THE CUST BUT NO GUARNTEE. THE CUST DID NOT WANT TO DO THAT TOLD ME HE WOULD LOOK INTO IT AND HUNG UP.

75 Around the same time various emails were sent between Rezzie Betta (the retailer) and LG. On 24 June 2014, following these emails, Maxine Vaifale of LG emailed Joe Monas of Rezzie Betta stating (the ‘Second CW Statement’):

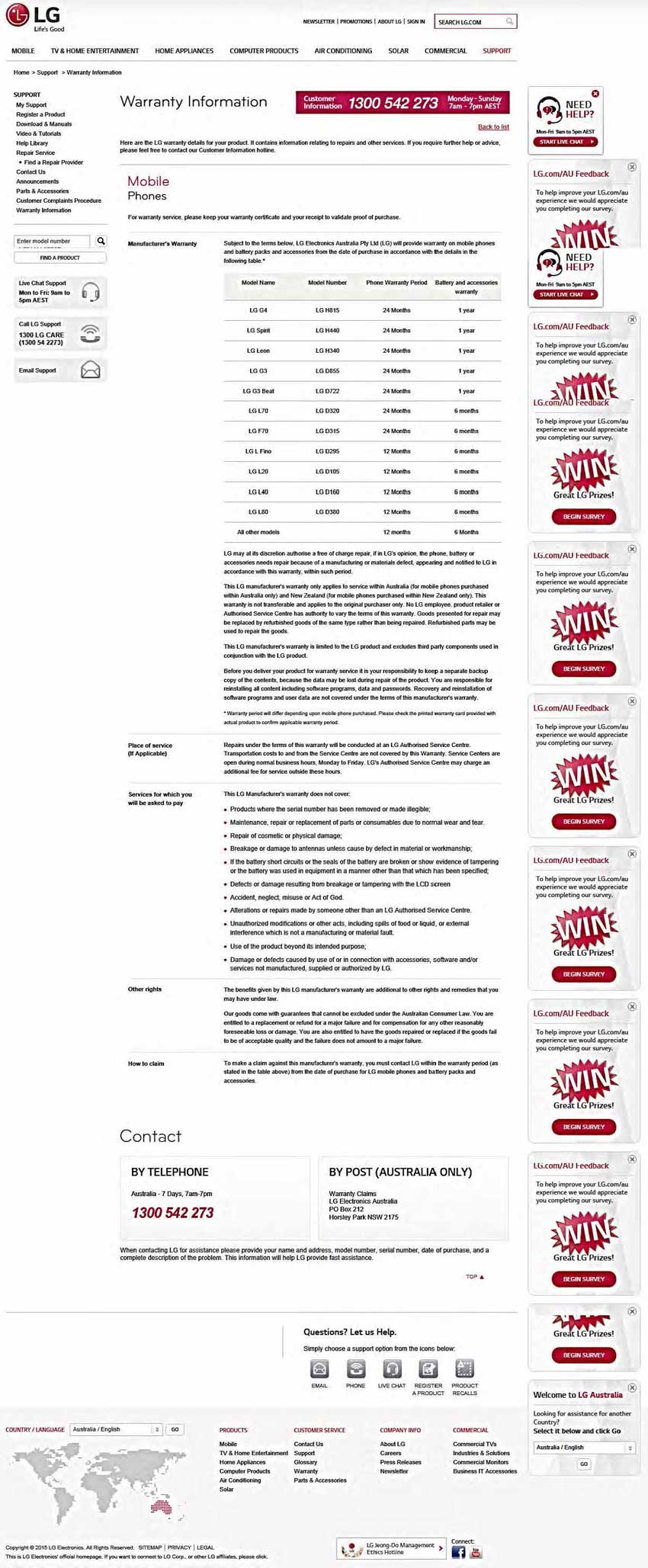

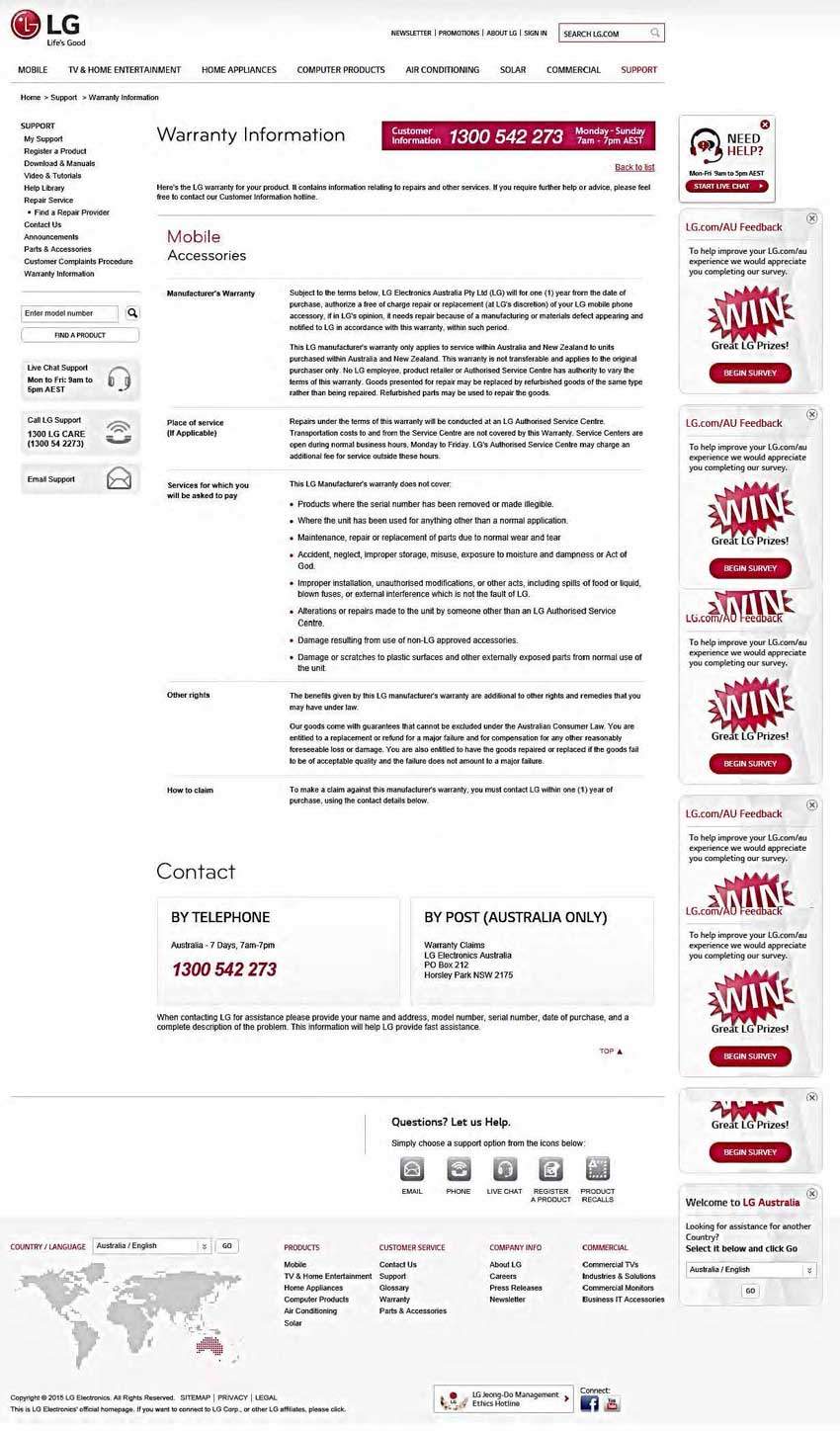

I have confirmed the details with Jorge & the service centre.

The customer’s unit is 10 months outside the manufacturer’s express warranty therefore the customer will need to organise an out of warranty assessment with the ASC, service centre are willing to do the assessment however customer refuses to pay the assessment fee.

If the customer is seeking out of warranty assistance they will need to have the unit assessed at their own cost in order for the assessment report to be sent through to LG’s in house techs who will review and advise in regards to out of warranty assistance.

Hope this helps.

76 On 25 July 2014, Ms Vaifale of LG emailed Meagan of Rezzie Betta stating (the ‘Fourth CW Statement’):

At this point in time, LG have made the decision to cover PARTS only for the customers out of warranty unit as a goodwill gesture due to the below facts;

- Unit is 11 months outside of the manufacturer’s express warranty

- No previous repair/history on customers unit

- This would be the first confirmed fault

- Part is readily available

However the cost of labour will be at the customer’s expense.

77 For clarity, the labelling of the CW statements is out of order because whilst they are listed chronologically above, they were put in a different order in the pleadings.

The ACCC’s claim

78 The ACCC alleges that:

in making the First CW Statement, LG made the Assessment Cost Representation to CW;

in making the Second CW Statement, LG made the Assessment Cost Representation and the Limited Warranty Representation to Rezzie Betta (the retailer);

in making the Third CW Statements, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation to CW; and

in making the Fourth CW Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation, the Goodwill Representation, the Repair Only Representation, and the Labour Cost Representation to Rezzie Betta–

–each of which was in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL.

79 I do not accept these allegations. In my view, it is not possible to treat these statements in isolation – they all are part of a course of conduct that only makes sense in the context of looking at each statement as a continuum of communication between LG and the consumer.

80 The statements made were made in the context of explaining LG’s position on the basis the television was out of warranty and that CW wanted a replacement from LG. At no time was LG liable in any event to refund, repair or replace the television (which was a liability of the supplier). LG may have had a liability to pay damages.

81 CW wanted practical assistance from LG, seeking to persuade LG to replace the television. This was the topic that LG addressed, and there was no implied suggestion that the statements were comprehensive statements of CW’s legal entitlements. LG had no obligation to advise upon CW’s general entitlement to remedies or relief. The requirement to produce some evidence of fault was not inappropriate or misleading, once it is appreciated the statements were made in the context I have explained.

82 I am not persuaded that in the nature of the enquiry there was any ‘reasonable expectation’ of the consumer to be told that the ACL applied to the goods, and that the consumer may have certain rights (not just against LG but also the supplier). Nor can it be said that LG’s deliberate focus on the express warranty (the topic of discussion) tended to lead the consumer into relevant error – the consumer was looking for specific assistance from LG and was provided with that assistance. LG did state what it “can do”, but these words should not be taken out of context. All that was meant, and reasonably understood by the recipient, was that LG was willing to act in a certain way. The context is that of a negotiation, one side asking for a particular course of action, the other side, responding as to what it was effectively prepared to do on the basis of the claim made.

83 The reference to “out of warranty” and “goodwill” gesture do not indicate any half-truth in the context of the enquiry. The TV was out of the LG warranty’s period. Without acknowledging that the TV was faulty due to a lack of durability, or accepting liability (whatever remedy that may provide), LG was entitled to indicate that as a goodwill gesture it was willing to assist in the way it offered to the consumer without further enquiry on LG’s part and further action by the consumer.

Television purchased by JF

Facts

84 On 13 August 2012, JF purchased a LG television for $1,750 from Hartley Wells Betta Home Living (‘Hartley Wells’) in Victoria (‘JF television’). At the time of purchasing the television, he was given a LG warranty card which set out his rights under the manufacturer’s warranty and noted that he had other rights including those under the ACL. By June 2014, the JF television had developed a fault, in that it had sound but no picture.

85 On 10 June 2014, Gavin Van Eede of Hartley Wells emailed LG stating that “[i]f he [JF] pushes this with consumer affairs he will win” and asked if the JF television could be assessed free of charge, given its age and cost.

86 Tracie Astin of LG forwarded this correspondence on to the DDS team and later followed up with an email pointing out that “[w]e do not need the customer contacting Consumer Affairs”. Ms Astin then emailed Ms Warwood and said “[a]lso the customer is claiming that under consumer affairs he is entitled to 2 years warranty”.

87 On 12 June 2014, Ms Warwood replied by email to Ms Astin stating: “Never heard of that. I know it is what is deemed reasonable which varies depending on who the person is”.

88 At some point before 24 June 2014, Ms Astin emailed Mr Van Eede. The email from Ms Astin to Mr Van Eede stated (the ‘First JF Statement’):

I left a message for you yesterday afternoon but you were unavailable. Direct Dealer Support have said;

At this point in time the TV the customer will need to have the TV inspected by the authorised repairer: JD DELL T/AS GARDNER ELECT/03 5662 2861/03 5662 5008/3953/SPARROW LANE, LEONGATHA, VIC to confirm that the fault is in fact a manufacturing defect.

The TV is now 10 months outside the manufactures warranty with no prior repairs claimed under the manufactures warranty. If LG look at assisting with the full cost of repair once the fault has been confirmed I will be more than happy to look at reimbursement of the assessment fee as well.

So please instruct the customer to take the TV to Gardener Electrics in Leongatha. Once the fault has been detected then a decision will be made if LG will cover the repair and the assessment fee will be reimbursed. There is no need for a job number he can just take the unit directly to Gardners.

Any questions please call me. I will be in a few meetings today but will have access to voicemail so can call you back later in the day if need be. Or alternatively you can call Direct Dealer Support for assistance.

89 JF subsequently had the television assessed by Gardner Electronics and sent the assessment report to LG. After receiving the assessment report, Ms Astin emailed Mr Van Eede and stated (the ‘Second JF Statement’):

However LG have reviewed the customer’s request for out of warranty assistance and at this point in time the cost of the repair will be at the customers expense due to the below factors;

- Unit is 10 months oow

- no prev repair/history on the unit

- both parts are readily available to complete repair

- Minor repair

Sorry Gavin but due to the above reasons the repair will not be covered by LG.

90 After some further correspondence, Ms Astin emailed Mr Van Eede on 3 July 2014 and stated (the ‘Third JF Statement’):

Dealer Support have come back and agreed to pay for the repair but not the labour charge. Since the unit is 10 months out of warranty I think this is a good outcome. What do you think?

LG have reviewed customers request and at this point in time as the unit is 10 months outside the manufacturer’s express warranty with no prev repair, we can offer to cover parts only – however labour is still at the customer’s expense.

91 On 4 July 2014, Ms Vaifale of LG emailed Gardner Electronics and stated (the ‘Fourth JF Statement’):

Hi All,

Just an FYI.

At this point in time LG have agreed to cover parts under warranty – however the cost of the labour will be at the customers expense.

You will be receiving and email from our warranty department with details in regards to the authority.

The ACCC’s claim

92 The ACCC alleges that:

in making the First JF Statement, LG made the Assessment Cost Representation and the Limited Warranty Representation to Hartley Wells (the retailer);

in making the Second JF Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation to Hartley Wells;

in making the Third JF Statement, LG made the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to Hartley Wells; and

in making the Fourth JF Statement, LG made the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to Gardner Electronics (the repairer)–

–each of which was in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL.

93 I do not accept these allegations. I will turn to consider each statement but again each statement must be put in context with each of the other statements.

The First JF Statement

94 The email was to the effect that after the television was assessed, LG would then be able to determine if they would meet the full cost of repair and, if so, if the assessment fee would be reimbursed. LG was indicating it would consider repair and reimbursement once it was in receipt of further information about the fault. The email is not representing that JF was only entitled to a certain remedy – it was a statement made by LG responding to the claim on the basis of the information LG had at the time. Again, there is a danger in relying on individual words in an email (such as “look at”, “a decision will be made”) which distracts from the nature and purpose of the initial communication by the consumer and the response by LG.

The Second JF Statement

95 The Second JF Statement is alleged to have given rise to the Limited Warranty Representation; that is, a representation that the remedies available to JF were limited to the LG manufacturer’s warranty. The email simply said what LG was prepared to do “at this point in time”. This statement was a statement of LG’s position to reject the consumer’s request for assistance. The email gave reasons for that rejection. The email did not purport to represent to the retailer or the consumer what the consumer’s rights were.

96 I again reiterate that there is no allegation in this proceeding that this statement was not a bona fide rejection of a claim, or that LG did not honestly hold the opinion that the consumer was not entitled to relief from it.

97 Whilst the email states definitely that the repair “will be” at the customers’ expense, again these words must be taken in context of the email. These words do not mean that there is not still on offer a potential change of position that could be made by LG in response to the claim. Again, the statement was representing what LG was willing to do in the circumstances at that time and on the basis of the information in LG’s possession.

The Third JF Statement

98 Again this statement should be characterised as an offer to deal with the consumer. Whilst there should not necessarily be a focus on individual words, the email uses the word “offer” and asks whether the retailer agrees that it is a good outcome. This was the whole gist of the communication.

99 It is also to be recalled that the consumer had not shown to LG that the fault gave rise to a liability for LG under the ACL.

100 I also do not infer that JF was actually misled as suggested by the ACCC. As I have already indicated, there are many reasons why an offer might be accepted even if the consumer knew that the offer did not provide all of their potential entitlements under the ACL. If the consumer had known of his rights, he may well have known of the difficulties he faced in proving his position and obtaining the relief he was after. One likelihood is that the consumer would come to LG looking for a resolution and this was one that he was content with, even with full knowledge of his rights under the ACL.

The Fourth JF Statement

101 As with the Third JF Statement, the Fourth JF Statement is alleged to give rise to representations that JF:

(1) was only entitled to have the product repaired, regardless of the nature of the defect (the Repair Only Representation); and

(2) was liable for the labour costs of the repair (the Labour Cost Representation).

102 As with the other statements, putting them in context, LG had come to an agreement with the consumer “[a]t this point in time”, focussing on the specific enquiry for assistance. I do not infer, as the ACCC has submitted, that JF was actually misled, just because he accepted the “offer” for reasons already explained: even if he knew of his potential remedies under the ACL, he may still have accepted that offer.

Television purchased by MM

Facts

103 On 14 July 2012, MM purchased a LG television for $889 from Kambo’s in Western Australia (‘MM television’). At the time of purchasing the television, he was given a LG warranty card which set out his rights under the manufacturer’s warranty and noted that he had other rights including those under the ACL. On about 8 September 2014, the MM television developed a fault in that it had sound but no picture. MM took the television to an authorised LG repairer, Smartvision, who determined that the television required a replacement display panel and that the panel had a damaged ribbon cable.

104 All relevant communications were conducted through the retailer.

105 MM sent an email attaching the purchase receipt and a quotation to Kambo’s, stating:

I have been advised to contact you in regards to our 127cm LG Plasma TV we purchased from your store in Canning Vale on 14/07/2012. Attached is a copy of our purchase receipt and a copy of the service report explaining the fault and a quote for the cost of repair.

We feel that having to replace the entire display panel in just over a 2 year period, falls well below what you expect as a reasonable lifetime for the product. Our expectation would be to discuss either repair or full refund.

106 On 10 September 2014, Kambo’s forwarded this email to LG. On 12 September 2014, Ms Vaifale of LG emailed Kambo’s and stated (the ‘First MM Statement’):

At this point in time LG can offer to cover the cost of parts however labour will be at the customers expense due to the unit being 14 month outside of the manufacturer’s warranty with no previous repair and this would be the first confirmed fault with the unit.

Hope this helps

107 On 18 September 2014, Ms Vaifale emailed Kambo’s again and stated (the ‘Second MM Statement’):

LG management have re-reviewed & declined customers request, at this point in time LG are happy to assist with covering parts only however labour will be at the customers expense due to the below factors;

- The unit is 14 months outside of the manufacturers express warranty

- No previous repair/history with the customers unit

- This would be the first fault

- Part is readily available to complete the repair.

108 MM knew he could approach the Department of Commerce, Consumer Protection Division to obtain information about his legal rights. MM gave evidence that no-one had given him advice about repair or full refund, and that he knew to some extent about his right to have something repaired or refunded.

The ACCC’s claim

109 The ACCC alleges that:

in making the First MM Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation, the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to Kambo’s (the retailer); and

in making the Second MM Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation, the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to Kambo’s–

–each of which was in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL.

110 I do not accept these allegations. In my view, it is again not possible to treat these statements in isolation.

111 This approach of LG is similar to that previously discussed. LG considered a specific request, made an offer and it was accepted. Unless there is placed upon LG some additional obligation to disclose the existence of the ACL, which may or may not have provided a remedy which MM may have wanted to pursue, I cannot conclude the conduct of LG involved a half-truth as alleged by the ACCC. Whilst MM in accepting the “offer” stated that he felt there was no other option, I cannot be satisfied that the statements relevantly misled MM, even though he ended up paying the costs of parts to repair his television. The comments I have made in the other situations on this issue are also relevant to this consumer’s situation.

Television purchased by PG and MG

Facts

112 On 5 March 2011, PG and MG purchased a LG television for $2,663.05 from Good Guys South Wharf in Victoria (‘PG television’). By 11 August 2014, the PG television had developed a fault, namely that there was a vertical line of failed pixels.

113 On 11 August 2014, PG telephoned LG and spoke to Ethel Chavez. The notation in LG’s customer relationship management record notes that “customer want to have it repair” and “provide IMPULSE AUDIO VISUAL – 03 9317 4040”. On 27 August 2014, Ms Vaifale also made a note about that earlier call in the customer relationship management record:

11/08/2014 customer called through to CIC to report the current fault – however due to the unit being 5 months outside of the manufacturer’s warranty with no previous repair we requested customer to have the unit assessed (at their own expense) to at least confirm fault & confirm if it is a manufacturing fault.

114 What was said during that phone call was a point of contention between the parties. However I accept, as the ACCC claimed, that a LG representative said to PG (the ‘First PG Statement’):

You will have to pay a call out fee even if the television is under warranty. We can repair the television and refund the call out fee if it is within warranty. If the problem with the television was caused by you, it won’t be refunded and you will have to pay for the repair.

115 Additionally I accept, as the ACCC claimed, that a LG representative also said to PG in subsequent telephone conversations (the ‘Third PG Statement’):

The customer service representative said: “Your television is out of warranty. You will have to pay to have it fixed.”

I said: “The television is faulty. It is not relevant that it is out of warranty. If you purchase a television, it should be repaired or replaced if it fails within a reasonable period after it is purchased.”

The customer service representative said: “We cannot repair the television for you, because it is out of warranty. Here are the details of the technician we would recommend. However, you will have to pay for the repairs.

116 On 29 August 2014, Lisa Kilner of LG emailed Fab Decesaris of The Good Guys Hoppers Crossing (‘The Good Guys HC’) and stated (the ‘Second PG Statement’):

DDS have come back with the following –

I’ve found customer’s details in our system (in regards to current fault and previously in 2011 about 3D glasses) – however no service history at all on the unit (this would be the first actual fault/repair)

11/08/2014 customer called through to CIC to report the current fault – however due to the unit being 5 months outside of the manufacturer’s warranty with no previous repair we requested customer to have the unit assessed (at their own expense) to at least confirm fault & confirm if it is a manufacturing fault.

At this point in time, as per above notes – we would request customer to get the unit assessed firstly, once the unit has been assessed service report can come through to LG and from there we can review and advise of any out of warranty assistance.

In this instance we can book a service call in with the customer – any genuine faults will be at LG’s expense.

Let me know what way you want to go with it.

117 Ms Kilner subsequently emailed Mr Decesaris again on 12 September 2014 and stated (the ‘Fourth PG Statement’):

Response with regards to this –

have made the decision to offer to cover parts only on the repair however the labour will still be at the customers expense as the unit is 6 months outside of the manufacturer’s express warranty & this would be the first confirmed fault with the unit

Therefore LG will cover the parts however labour will be at the customers expense as it is outside of manufacturers warranty.

The ACCC’s claim

118 ACCC alleges that:

in making the First PG Statement, LG made the Assessment Cost Representation to PG;

in making the Second PG Statement, LG made the Assessment Cost Representation and the Limited Warranty Representation to The Good Guys HC (the retailer);

in making the Third PG Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation to PG; and

in making the Fourth PG Statement, LG made the Limited Warranty Representation, the Repair Only Representation and the Labour Cost Representation to The Good Guys HC–

–each of which was in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL.

119 I do not accept these allegations. In my view, it is again not possible to treat these statements in isolation. At a very general level, I do not characterise any of the statements as being other than the expression (definitive as it may be) as to the position (negotiable or otherwise) of LG in terms of what it was prepared to offer. Whether it is expressed to be a “final position” (as characterised by the ACCC) is not pertinent, if viewed as a negotiation and offer by LG. LG was entitled to so conduct itself, recalling there is no allegation in this proceeding of bad faith, deliberate falsehood going to ultimate liability, or other unconscionable conduct.

120 This approach of LG is similar to that previously discussed. LG considered a specific request, made an offer and it was accepted. Unless there is placed upon LG some additional obligation to disclose the existence of the ACL, which may or may not have provided a remedy which PG may have wanted to pursue, I cannot conclude the conduct of LG was in contravention of the ACL as a half-truth as alleged by the ACCC.

Television purchased by RH

Facts

121 On 8 December 2012, RH purchased a LG television for $2,126 from JB Hi-Fi Osborne Park in Western Australia (‘RH television’). By 2 June 2014, the RH television had developed a fault, namely a big grid pattern on the screen and black lines. RH took the RH television to an authorised LG repairer, Perth Digital, who determined it had a faulty panel.

122 On 30 June 2014, Thai Nguyen of Perth Digital emailed LG and stated: “Customer claimed you will be covering this unit under warranty”. On 3 July 2014, Ms Warwood of LG replied to Mr Ngyuen by email and stated (the ‘First RH Statement’):

LG have no mention to this customer that we are assisting OOW.

The TV is currently 7months out of the manufactures warranty with no prior repairs claimed with, the customer needs to get the TV assessed [at their cost] at this point in time to confirm if the fault is in fact a manufacturing defect or not & send report back to LG for review.