FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Billiton Nickel West Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 991

ORDERS

CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MINING AND ENERGY UNION Applicant | ||

AND: | BHP BILLITON NICKEL WEST PTY LTD First Respondent STACEY SCAFFARDI Second Respondent MICAHEL CONSTABLE Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 The facts of the present case are not in question.

2 Two organisers employed by the Western Australian Divisional Branch of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (Messrs Doug Heath and Troy Smart) were at the relevant time holders of entry permits which had been issued under s 512 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”).

3 On 12 October 2015 Messrs Heath and Smart gave notice of entry to premises in Kwinana in Western Australia occupied by the First Respondent, BHP Billiton Nickel West Pty Ltd. The working hours of the nickel refinery operating at those premises were twenty-four hours per day. Persons who performed work at those premises included crane drivers whose interests were represented by the CFMEU. Those crane drivers were working consecutive 12-hour shifts from 6.00am to 6.00pm and 6.00pm to 6.00am. Messrs Heath and Smart wanted to enter the premises to hold discussions with those employees between 5.15am and 6.30am.

4 Messrs Heath and Smart were refused entry. They were told that no breaks were scheduled for those employees at that time.

5 The CFMEU commenced this proceeding in March 2017 claiming a contravention of s 501 of the Fair Work Act.

6 The proceeding is to be dismissed. Section 484 of the Fair Work Act did not authorise the entry of Messrs Heath and Smart for the purposes of holding discussions between 5.15am and 6.30am. There was accordingly no contravention.

7 An earlier application seeking to transfer the proceeding from the New South Wales Registry of this Court to its Western Australia Registry pursuant to s 48 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) was refused. The matter had been commenced in Sydney and could just as easily be resolved in Sydney as in Perth.

The Fair Work Act

8 All provisions of immediate relevance to the resolution of the present dispute are to be found in Part 3-4 of the Fair Work Act. That Part is headed “[r]ight of entry”.

9 The object of Part 3-4 is set forth as follows in s 480:

Object of this Part

The object of this Part is to establish a framework for officials of organisations to enter premises that balances:

(a) the right of organisations to represent their members in the workplace, hold discussions with potential members and investigate suspected contraventions of:

(i) this Act and fair work instruments; and

(ii) State or Territory OHS laws; and

(b) the right of employees and TCF award workers to receive, at work, information and representation from officials of organisations; and

(c) the right of occupiers of premises and employers to go about their business without undue inconvenience.

10 Division 2 within Part 3-4 is headed “[e]ntry rights under this Act”. It has a number of Subdivisions. Subdivision A is headed “[e]ntry to investigate suspected contravention”. Within that Subdivision, s 481 confers a right of entry upon a permit holder to enter premises to investigate a suspected contravention of the Fair Work Act. Section 482 specifies the rights that may be exercised whilst a permit holder is on the premises to investigate a suspected contravention. Subdivision AA is headed “[e]ntry to investigate suspected contravention relating to TCF award workers”. Sections 483A and 483B similarly confer a right of entry to investigate a contravention and specify the rights that may be exercised whilst a permit holder is on the premises for that purpose.

11 Subdivision B is headed “[e]ntry to hold discussions”. That Subdivision comprises only one section, s 484, which provides as follows:

Entry to hold discussions

A permit holder may enter premises for the purposes of holding discussions with one or more employees or TCF award workers:

(a) who perform work on the premises; and

(b) whose industrial interests the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent; and

(c) who wish to participate in those discussions.

12 Subdivision C is headed “[r]equirements for permit holders”. Within Subdivision C, s 490 specifies “[w]hen right may be exercised”. That section provides as follows:

When right may be exercised

(1) The permit holder may exercise a right under Subdivision A, AA or B only during working hours.

(2) The permit holder may hold discussions under section 484 only during mealtimes or other breaks.

(3) The permit holder may only enter premises under Subdivision A, AA or B on a day specified in the entry notice or exemption certificate for the entry.

13 Division 4, also within Part 3-4 is headed “[p]rohibitions” and it is within that Division that s 501 appears. That section provides as follows:

Person must not refuse or delay entry

A person must not refuse or unduly delay entry onto premises by a permit holder who is entitled to enter the premises in accordance with this Part.

The confined factual context – the purpose expressly identified

14 It is these provisions which are to be applied to the facts presented.

15 Unlike a factual context in which there may be uncertainty as to the right sought to be exercised or the purpose, the Applicant in the present proceeding has expressly identified the “right” sought to be exercised and the “purpose” sought to be pursued.

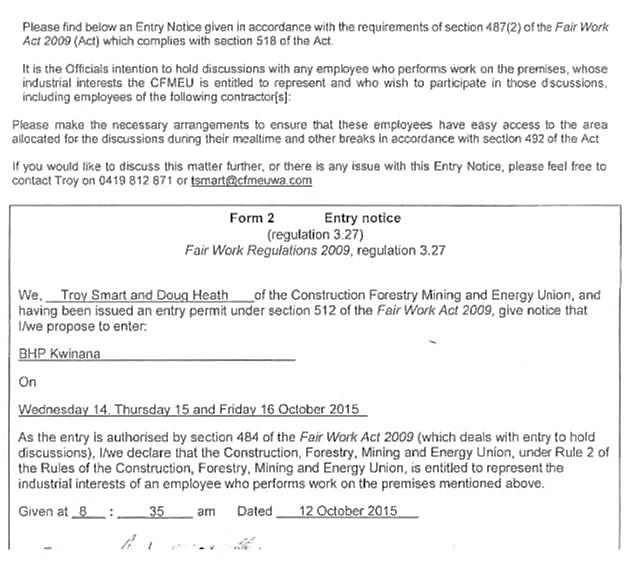

16 The entry notice given to the occupier on 12 October 2015 as required by s 487 of the Fair Work Act thus provided in relevant part as follows:

It will be noted that it is there stated that “[i]t is the Officials intention to hold discussions with any employee who performs work on the premises, whose industrial interests the CFMEU is entitled to represent and who wish to participate in those discussions”. Although the notice appears to be incomplete in that it does not specify the “following contractor[s]”, the purpose of seeking entry is expressly stated. The entry notice also expressly states that “the entry is authorised by section 484 of the Fair Work Act”.

17 Clarification was sought on 13 October 2015 of “who the ROE will be for ie is this for BHP B Nickel West Employees or for Contractors and if so who?” The clarification sought was provided by Mr Heath on the same day. The response also stated (without alteration) that the “intent at this stage is to make visit members and potential members for the period 0515 and 0630 and during their crib and meal breaks”.

18 Later on the same day, namely 13 October 2015, Messrs Heath and Smart were advised that “[t]here are no breaks, crib or meal times between 0515 – 0630 and you will not be able to facilitate a ROE at this time”. A letter attached to that email identified the “crib times for employees” as being:

Smoko - 9am, 3pm

Lunch Midday.

19 Mr Heath responded that he was nevertheless entitled to exercise his right of entry. In support of that claim, Mr Heath made reference to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 (Cth) and responded (in part) as follows:

I refer to your letter of 13th October regarding the Right of Entry Notice issued by Troy Smart and myself.

CFMEU Officials can exercise their right of entry before employees commence their shift. The Fair Work Act 2009 (Act) makes clear that a right of entry may be exercised during working hours and during mealtimes or other breaks. For guidance as to what is meant by ‘other breaks’ I refer you to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008, and specifically para. 1962. Here it makes clear that other breaks, would include holding discussions before or after an employee’s shift, provided the discussions are held within the working hours of the premises.

I have been advised that work for our members starts at 6:00 and we have no reason to doubt this, nevertheless, the premises are quite clearly in operation prior to this as a multitude of people on the premises have commenced work for the day.

Given our intention to have our first meeting with members and prospective members at 0515, Mr Smart and I will be on site at 0500 for our visitor induction. Can you please advise site personnel of this to ensure we are inducted in time for us to exercise our Right of Entry.

(Emphasis in original.)

The response to Mr Heath, also on 13 October 2015, rejected this claim as follows:

BHP Billiton agree that you may exercise right of entry and hold discussions with your members “only during mealtimes or other breaks”. However, we do not agree that, in the case of this site, the period before and after the relevant employee’s shift is an “other break” for the purposes of section 490(2) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

It is the text of the Act that is relevant, and it is clear and unambiguous in this case. One can obviously not be on a “break” from work, if one has not started work. The Explanatory Memorandum provides an example which may apply in some cases. However, there is no designated break before or after the relevant employee’s shifts on this site.

Therefore, you and Mr Smart may attend the site to perform your inductions at 5.00am. However, you may only hold discussions between the mealtimes and other breaks of the relevant employees, being 9.00am, 12.00pm and 3.00pm as referred to in my previous letter. If you wish to hold discussions with the relevant employees outside of those times, you may of course do so separately and not on site, this includes the car park and smoking hut.

20 The issue dividing the parties was thus clearly identified. It was accepted that Messrs Heath and Smart could exercise their right of entry. However the Respondents position was that Messrs Heath and Smart could only “hold discussions” at the three times specified. The Respondents denied that there was a right to enter the premises for the purposes of holding discussions prior to or after an employee’s shift.

Other breaks

21 In its written Outline of Submissions, the Applicant expressed the question to be resolved as being whether the phrase “other breaks” in s 490(2) is confined to “breaks” during an employee’s hours of work or – as the Applicant would have it – is a phrase “capturing all non-working times of employees that are not mealtimes”. During oral submissions, the ambit of the phrase “during meal times or other breaks” was differently expressed and expressed in terms of referring to those “[t]imes during the working hours of the premises [sought to be entered] when … employees … who are at the premises are not required to work or perform paid work”.

22 It was the latter formulation which more accurately captured the question sought to be resolved by the Applicant. But, even so reformulated, the question (with respect) failed to identify with precision the class of employees with whom discussions were to be held and expressed the question more globally than was presented by the facts of the present case.

23 As was manifest from their responses to the entry notice sent to them on 12 October 2015, the Respondents denied the existence of the right asserted by Messrs Heath and Smart.

24 To resolve the impasse dividing the parties it is, with respect, necessary to draw a line between when the right of entry could be exercised and when discussions could be held.

25 Section 490(1), on this approach, clearly constrains the time at which “a right under Subdivision A, AA or B” can be exercised – including the right conferred by s 484 to hold discussions – to a time “during working hours”. Section 484, being the sole provision within Subdivision B, together with the rights conferred under Subdivisions A and AA, can only be exercised “during working hours”. Section 490(1), at its most obvious, does not entitle a permit holder to seek entry to premises when the premises are shut, when no work is being undertaken and indeed when no-one is present. On the facts of the present case, the “working hours” were twenty-four hours per day (cf. Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union v Australian Food Corporation Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1709 at [67] to [69]; [76] to [79]; [98] to [99], (2001) 116 FCR 19 at 31 per Wilcox J; 32 to 33 per Hill J; 35 per Carr J).

26 Section 490(2), on this approach, says nothing as to when the right of entry conferred by s 484 could be exercised but is confined to a specification of that time when a permit holder who has exercised his right of entry can “hold discussions”, that constraint being that discussions can only be held “during mealtimes or other breaks”.

27 Sections 490(1) and 490(2) self-evidently employ different language and each sub-section performs a different function or imposes a different constraint – the former being expressed in terms of “during working hours”; the latter being expressed in terms of “mealtimes or other breaks”.

28 On the part of those seeking to enter premises pursuant to s 484 to hold discussions, there may in some factual circumstances be uncertainty as to whether the employees with whom they are entitled to hold discussions would be present on site, whether any such employees who may be present are working or when their “mealtimes or other breaks” are to take place. But any such uncertainty may not preclude a lawful exercise of the right of entry conferred by s 484 at any time “during working hours”. The absence of any such employees or the fact that no employees may wish to participate in discussions or the fact that there may be no “mealtimes or other break” during which discussions may take place does not preclude a lawful exercise of the right of entry conferred by s 484 at a time constrained by s 490(1). The purpose for which the right has been exercised, namely to hold discussions, may go unfulfilled because (for example) no employees can be found who wish to hold discussions or because no discussions in fact take place; but the lawfulness of the exercise of the right of entry would remain.

29 That which would exceed the authority conferred by s 484, and that which would not be a lawful exercise of the right, would be an entry onto a premises ostensibly to hold discussions but in fact for some entirely different purpose divorced from the “purpose” prescribed by s 484, namely for the “purposes of holding discussions”. It would equally be an excess of the authority conferred by s 484 to seek to enter premises for the “purposes of holding discussions” when the premises are closed (and hence contrary to s 490(1)) as it would be to seek entry at a time when it is known that there are no employees on site whose interests they are entitled to represent or to enter premises at a time when it is known that employees who may wish to hold discussions with the permit holders are in fact performing scheduled work (and hence contrary to s 490(2)).

30 All such possible exercises of the right conferred by s 484, however, do not arise on the facts of the present case.

31 On the facts of the present case, Messrs Heath and Smart accepted that the employees with whom they wished to hold discussions may well have been on site as from about 5.15am but also accept that at that time the employees with whom the discussions were to be held had not commenced their scheduled working day. Section 484, it is concluded, conferred no right of entry in such circumstances. Discussions could only be held with those employees, consistent with the constraint imposed by s 490(2), “during mealtimes or other breaks”. Prior to the commencement of the working day, s 484 conferred no right of entry to hold discussions with those workers before they commenced their shift. Messrs Heath and Smart, on the facts of the present case, did not seek to enter the premises for any other “purpose”.

32 Even though a right of entry may be exercised “during working hours” (s 490(1)) and even in the case of a site such as the present which operates twenty-four hours per day, s 484 cannot be construed as conferring a right of entry to hold discussions with employees outside of their scheduled working hours even though other employees with whom discussions are not to be held may also be working. Section 490(2) is a specific constraint directed to that point of time when a permit holder may hold discussions with those employees whose industrial interests the permit holder is entitled to represent and those employees the sole target of the exercise of the right conferred. The fact that other employees whose interests the permit holder does not represent may also be working at the point of time when entry is sought does not expand the time during which discussions may be held.

33 The right conferred by s 484 is not a right conferred at large; it is a right relevantly confined to holding discussions with a confined class of employees, namely those whose industrial interests the permit holder is entitled to represent, and further is a right confined to holding discussions with that class of employees “during [their] mealtimes or other breaks”.

34 Contrary to the submissions of the Applicant, so much it is respectfully considered follows from the natural and ordinary meaning of the statutory language employed in ss 484 and 490; the manner in which the construction of those provisions should be approached; and the reasons for decision of this Court in Central Queensland Services Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 43.

35 As to the first of these considerations, that the statutory language dictates the conclusion reached necessarily follows from:

the constraints imposed by s 484, namely the constraints to hold discussions with a specified class or employees;

the contrast between the phrase employed in s 490(1), namely “during working hours”, and the phrase employed in s 490(2), namely “during mealtimes or other breaks” (Central Queensland Services [2017] FCAFC 43 at [35] per Tracey and Reeves JJ). “[M]ealtimes or other breaks” is a phrase which would include a “smoko” break and breaks occasioned by inclement weather (cf. Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Bolton (No 2) [2016] FCA 817 at [5] to [6] and [38], (2016) 261 IR 452 at 455 to 457 and 466 per Collier J);

the natural and ordinary meaning of the phrase “mealtimes or other breaks”, namely a phrase which characterises the times during which the right can be exercised as being those times when an employee may be at work but not physically engaged in discharging the responsibilities for which he has been employed; and

the constraint implicit in the term “breaks”, namely a term which implicitly conveys the notion that there is a “break” in something which is otherwise happening, it not being possible to have a “break” during the working hours of an employee before the working hours of that particular employee or class of employee commences of after they have finished.

Such a conclusion, it is further considered, does no disservice to the object and purpose of the statutory right of entry. Such a construction permits the exercise of the right conferred by s 484 “during working hours” but does not permit the exercise of the right during those hours when it is accepted that there are no employees with whom discussions can be held. No statutory authority, of course, is needed for Messrs Heath or Smart to hold discussions with the employees whose interests they are entitled to represent (or, indeed, any other employee or person) outside their normal working hours and whilst such employees or persons are not on the premises of the occupier or employer. The sole concern of ss 484 and 490 is to confer a right of entry upon premises to hold discussions with employees during their normal working hours but at a time when they are on a meal break or “other break”.

36 Other constraints imposed by the legislation itself and which also support the confined nature of the right of entry conferred and the deliberate attempt by the Legislature to “balance” (s 480) the interests of those seeking to exercise the rights and the rights of occupiers, include the fact that the rights conferred by such provisions as s 484:

are conferred only upon those persons to whom a permit has been granted, being persons who must be “fit and proper” to hold such a permit (s 512) and upon a person who may have the right suspended or revoked (s 507);

can only be exercised for stated purposes, such as “holding discussions” with those employees “whose industrial interests the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent” (s 484);

may be the subject of conditions imposed (ss 507 and 515); and

requires the giving of notice (s 487).

37 As to the next consideration, provisions such as s 484 which make lawful an entry upon premises that which would otherwise be an unlawful trespass in the absence of the consent of the occupier, are to be construed as conferring no greater right than the statutory language itself permits: Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union v Fair Work Australia [2012] FCAFC 85, (2012) 203 FCR 389. In that case, this view was expressed as follows (at 405 and 407):

[56] The right of entry conferred by s 484 is thus not an untrammelled right. It is a right subject to both express and implied constraints. One express constraint is that the right of a permit holder is one that must be exercised for one or other of the “purposes” set forth in s 484. Another express constraint is that the right of entry is subject to any “reasonable request” that may be made by the occupier of the premises that the permit holder seeks to enter. A further express constraint is that contained within s 490(2) limiting discussion to meal and lunch breaks. An implied constraint is that the right must be exercised so as to promote the object of Pt 3-4 as set forth in s 480.

[57] Like other rights of entry conferred by the Fair Work Act … s 484 is a statutory right which diminishes the common law rights of an occupier.

…

[63] … There is much to be said for the view that the statutory right of entry conferred on a permit holder by s 484 should not be construed as conferring any greater right than is necessary to achieve the statutory objective. The common law rights of an occupier, on this approach, are only to be diminished to the extent absolutely necessary to give effect to the right conferred. Subject only to the requirement that an occupier make a “reasonable request”, the balance that the Legislature has sought to achieve between granting a statutory right of access and the consequent diminution of the common law rights of an occupier is thereby struck.

Justice Tracey agreed. Justice Jessup delivered his own reasons for reaching the same conclusion. The statutory right of entry is a legislative attempt to balance the objects and purposes in conferring the right as against the rights of an occupier. See also: Maritime Union of Australia v Fair Work Commission [2015] FCAFC 56 at [14] to [15], (2015) 230 FCR 15 at 20 to 21 per North, Flick and Bromberg JJ. Although the rights conferred are “beneficial ones [which] should be construed with an eye on the important role of organisations in protecting their members” (Independent Education Union of Australia v Australian International Academy of Education Inc [2016] FCA 140 at [109] per Jessup J), they remain rights which are not “untrammelled” by legislative constraints. This approach to the construction of provisions such as s 484 sits comfortably with the well-accepted proposition that “clear and unambiguous words” are required before common law rights are abolished or modified: cf. Bropho v Western Australia (1990) 171 CLR 1 at 17 per Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ. “Statutory authority to engage in what otherwise would be tortious conduct”, it has been said, “must be clearly expressed in unmistakable and unambiguous language”: Coco v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 427 at 436 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Gaudron and McHugh JJ. See also: Momcilovic v The Queen [2011] HCA 34 at [43], (2011) 245 CLR 1 at 46 to 47 per French CJ.

38 The present construction of ss 484 and 490, it is finally considered, is also supported by the decision in Central Queensland Services [2017] FCAFC 43. In that decision, Jessup J noted that the “legislature has … confined the right to hold discussions under s 484 to ‘mealtimes or other breaks’”: [2017] FCAFC 43 at [6]. Similarly, Tracey and Reeves JJ there also noted that “discussions may only be held during meal times or other breaks”: [2017] FCAFC 43 at [35]. It was in that context that their Honours made their observations as follows in respect to the contrast in language between s 490(1) and s 490(2):

[35] … It is also necessary to bear in mind that s 492 is intended to apply to two distinct categories of persons and during two different time periods. That is, it includes a circumstance where a union official wishes to have discussions with a union member (s 484), and a situation where a union official wishes to have discussions with any person (not necessarily a member of his/her union) about a suspected contravention of the [Fair Work Act] (s 482(1)(b)). Furthermore, while the former discussions may only be held during meal times or other breaks (s 490(2)), the latter interviews may be held during the whole working day (s 490(1)). In our view, there is therefore no indication in s 480, or in the provisions of Part 3-4 more broadly, that one of the purposes or objects of that Part of the [Fair Work Act] is to prevent permit holders from interfering with the performance of work when they enter a workplace.

To accept the construction now sought to be placed upon s 490(2) by the CFMEU could be seen as running contrary to the observations of Tracey and Reeves JJ.

39 Section 484 is, accordingly, not a right to enter premises for whatever purposes a permit holder may wish to pursue or a right to enter premises at whatever times a permit holder may unilaterally chose.

The Explanatory Memorandum

40 Counsel for the Applicant sought to buttress his case by reference to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 (Cth).

41 That Explanatory Memorandum provided, in relevant part, as follows:

Clause 484 – Entry to hold discussions

1938. This clause authorises a permit holder to enter premises for the purpose of holding discussions with persons at the premises if one or more of those persons:

• perform work on the premises;

• are entitled to be represented by the permit holder’s organisation; and

• wish to participate in those discussions.

1939. The Bill limits when discussions can be held to mealtimes or other break periods. Discussions cannot occur during paid work time (see subclause 490(2)).

…

Clause 490 – When right may be exercised

1960. This clause specifies the time during which entry rights under this Division can be exercised.

1961. Entry to premises to hold discussions or to investigate a suspected contravention may only occur during working hours (see subclause 490(1)). Working hours refers to the actual operating hours of the premises that the permit holder wishes to enter. In addition, permit holders may only enter on a day specified in the entry notice or the exemption certificate for the entry (see subclause 490(3)).

1962. When entering for discussion purposes under Subdivisions B, a permit holder may only hold the discussion during mealtimes or other breaks (subclause 490(2)). Discussions cannot occur during paid work time. An example of other breaks would include holding discussions before or after an employee’s shift, provided the discussions are held within the working hours of the premises.

1963. If a permit holder seeks to hold discussions outside break times, she or he would not be authorised to enter or remain on the premises because of the operation of clause 486.

Particular reliance was sought to be placed upon para [1962]. The facts presented in the current proceeding, it was submitted on behalf of the Applicant, was the very example contemplated in para [1962] as being a lawful exercise of the right of entry. So much may be assumed.

42 There are nevertheless two difficulties confronting reliance being placed upon the Explanatory Memorandum in the present circumstances, namely:

although it is not necessary to first ascertain an ambiguity before recourse may be had to secondary material (cf. CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd (1997) 187 CLR 384 at 408 per Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Exchange Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 226 at [11], (2005) 148 FCR 132 at 136 per Tamberlin, Finn and Conti JJ), reliance may be placed upon secondary material such as the Explanatory Memorandum to “determine the meaning” (for example) of a provision which is “ambiguous or obscure” (Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 15AB(1)(b)). In the present case it is not considered that there is any ambiguity or obscurity in meaning and the meaning and application of ss 484 and 490 can be resolved by reference to the natural and ordinary meaning of the words employed by the Legislature; and

reliance cannot be placed upon secondary material to alter the meaning to be given to the natural and ordinary meaning of the words employed by the Legislature. The words of an Explanatory Memorandum or the “words of a Minister”, it has been said, “must not be substituted for the text of the law” (Re Bolton; Ex parte Beane (1987) 162 CLR 514 at 517 to 518 per Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ. In the case of an Explanatory Memorandum, see: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v QR Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 652 at [22] per Logan J).

“The function of the Court is to give effect to the will of Parliament as expressed in the law”: Re Bolton; Ex parte Beane (1987) 162 CLR 514 at 518 per Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ. See also: Power Rental Op Co Australia, LLC v Forge Group Power Pty Ltd (in liq) (rec and mgr appointed) [2017] NSWCA 8 at [90] per Ward JA (Bathurst CJ and Beazley P agreeing).

43 Reliance, it is thus respectfully concluded, cannot be placed upon the Explanatory Memorandum, or even if it can, such reliance cannot displace the natural and ordinary meaning of the words employed by ss 484 and 490 so as to authorise the entry upon the premises sought by Messrs Heath and Smart.

Conclusions

44 On the facts of the present case, Messrs Heath and Smart could not exercise the right conferred by s 484 either because:

although they could enter the site at 5.15am, that being a time “during [the] working hours” of the premises (s 490(1)), they could not enter the site for their stated purpose, namely to hold discussions with the employees or a class of employees whose interests they were entitled to represent. At that point of time, and indeed prior to 9.00am, no such employee had a “break” during which such discussions could be conducted (s 490(2));

or, albeit expressing the former reason differently:

section 484 did not authorise entry upon the premises for the purposes of holding discussions with such employees prior to their scheduled working hours commencing.

45 Any purported exercise of power at times when the right could not be exercised would properly be characterised as either not authorised or as an abuse of power. No exercise of a right “during [the] working hours” of the premises could be countenanced which permitted the exercise of the right at a point of time when those exercising the right accepted that their stated purpose of then holding discussions could not be achieved. On the facts of the present case, the only times at which discussions could be held for the purposes of ss 484 and 490(2) were 9.00am, midday and 3.00pm. Presently left to one side are cases where there may be genuine uncertainty as to when employees start or finish work or when “mealtimes or other breaks” may occur.

46 Not that it assumes any immediate relevance, but it should nevertheless be noted that no suggestion was advanced in the present proceeding on behalf of the Applicant that the refusal of the right of entry prior to the employees’ commencement of working hours frustrated or otherwise inhibited those seeking to exercise the statutory right of entry from holding discussions with those employees at other times.

47 There has been no contravention of s 484 of the Fair Work Act.

48 The Application should be dismissed.

THE ORDER OF THE COURT IS:

The proceeding is dismissed.

I certify that the preceding forty-eight (48) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Flick. |