FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Moroccanoil Israel Ltd v Aldi Foods Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 823

ORDERS

BETWEEN: | MOROCCANOIL ISRAEL LTD Applicant/Cross-Respondent | |

AND: | ALDI FOODS PTY LTD (ACN 086 210 139) (IN ITS CAPACITY AS GENERAL PARTNER OF ALDI STORES (A LIMITED PARTNERSHIP)) First Respondent/First Cross-Claimant ALDI PTY LIMITED (ACN 086 493 950) (IN ITS CAPACITY AS LIMITED PARTNER OF ALDI STORES (A LIMITED PARTNERSHIP)) Second Respondent/Second Cross-Claimant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | ||

PENAL NOTICE

TO: THE PROPER OFFICER, ALDI FOODS PTY LTD (ACN 086 210 139)

THE PROPER OFFICER, ALDI PTY LTD (ACN 086 493 950)

You will be liable to imprisonment, sequestration of property or other punishment if you:

(a) refuse or neglect to do any act within the time specified in this Order for the doing of the act; or

(b) disobey the order by doing an act which this Order requires you to abstain from doing.

Any other person who knows of this order and does anything which helps or permits you to breach the terms of this order may be similarly punished.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. By exhibiting, offering for sale, selling, supplying, advertising, and/or promoting each of the:

(a) Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1);

(b) Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 2);

(c) Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo; and

(d) Moroccan Argan Oil Dry Shampoo

products, in conjunction with the word “Naturals” (including on the packaging and labelling of the products depicted in cells 1–7 and 11 of the Schedule to these orders), the First and Second Respondents (together, the Aldi Partnership) have represented to the Australian public that each of the products referred to in 1(a) to (d) above contains only or substantially natural ingredients (individually and collectively, the Natural Representations).

2. The Natural Representations are misleading.

3. By making the Natural Representations the Aldi Partnership has:

(a) engaged in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL); and

(b) made misleading representations as to the composition of the products referred to in 1(a) to (d) above, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL.

4. By exhibiting, offering for sale, selling, supplying, advertising, and/or promoting each of the products referred to in 4(a) to (g) below, including by use of the packaging and labelling depicted in cells 1–10 and 12–15 of the Schedule, the Aldi Partnership has represented to the Australian public that:

(a) the argan oil in the formulation of the Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1):

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) helps strengthen hair;

(iii) restores shine and provides long term conditioning; and

(iv) used regularly leaves hair shiny and healthy;

(b) the argan oil in the formulation of the Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) helps strengthen hair and restore shine;

(iii) helps protect hair from styling, heat and UV damage;

(iv) leaves hair soft and silky; and

(v) makes hair feel healthier, soft and silky making it easier to style;

(c) the argan oil in the formulation of the Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) helps strengthen hair and restore shine;

(iii) helps protect hair from styling, heat and UV damage;

(iv) leaves hair soft and silky; and

(v) makes hair feel healthier, soft and silky making it easier to style;

(d) the argan oil infused in the bristles of the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Brushes:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product; and

(ii) aids in delivering shine and hydration;

(e) the argan oil infused in the heating element of the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Dryer:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) delivers high shine and protection;

(iii) provides heat protection against breakages and split ends caused by using heated styling tools; and

(iv) provides conditioning for a smooth and silky styling finish;

(f) the argan oil infused in the ceramic heating plates of the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Straightener:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) protects and nourishes dry or damaged hair;

(iii) provides heat protection against breakages and split ends caused by using heated styling tools; and

(iv) provides conditioning for a smooth and silky styling finish; and

(g) the argan oil infused in the barrel of the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Curler:

(i) makes a material contribution to the performance of the product;

(ii) protects and nourishes dry or damaged hair;

(iii) provides heat protection against breakages and split ends caused by using heated styling tools; and

(iv) provides conditioning for a smooth and silky styling finish

(individually and collectively, the Argan Oil Representations).

5. The Argan Oil Representations are false.

6. By making the Argan Oil Representations, the Aldi Partnership has engaged in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The reasons distributed confidentially to the parties on 24 July 2017 be withdrawn.

2. As and from four (4) weeks from the date of these orders, the Aldi Partnership, whether by itself, its partners, employees, servants, agents, or otherwise, be permanently restrained from exhibiting, offering for sale, selling, supplying, advertising, and/or promoting in Australia:

(a) the following products depicted in cells 1–7 and 11 of the Schedule:

(i) Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1);

(ii) Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 2);

(iii) Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo; and

(iv) Moroccan Argan Oil Dry Shampoo

(or the same products by another name) in conjunction with the word “Naturals” or as natural or substantially natural, whether in packaging, on labelling, or otherwise; and

(b) the following products depicted in cells 1–10 and 12–15 of the Schedule:

(i) Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1);

(ii) Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo;

(iii) Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner;

(iv) the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Brushes;

(v) the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Dryer;

(vi) the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Straightener; and

(vii) the Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Curler

(or the same products by another name) in conjunction with the Argan Oil Representations, whether in packaging, on labelling, or otherwise.

In this order, “the same products” means products containing the same ingredients in the same percentages as the products depicted in the Schedule.

3. The application otherwise be dismissed, save for:

(a) the question of damages and compensation in respect of the contraventions of the ACL by the Aldi Partnership; and

(b) the question of costs.

4. Pursuant to s 92(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), the Registrar of Trade Marks be directed to remove the following goods in class 3 from the registration of Trade Mark Registration No 1221017 (the First Trade Mark):

skin care products in this class; skin cleansers; skin toners; skin moisturizers; anti-aging cream; eye cream; beauty masks; body creams; hand creams; non-medicated foot cream; eye makeup; foundation makeup; lip liner, lipsticks and lip balms; eyeliners; blushes; eye shadow; nail enamels; toiletries and cosmetics including shaving preparations, shaving creams and soaps, after shave creams and lotions, body massage creams and oils, soaps, bath oils and shower gels, talcum powders; antiperspirants; dentifrices; sunscreen and suntan oils and creams; fragrances in this class, including perfumes, colognes, essences and essential oils.

5. Pursuant to s 92(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), the Registrar of Trade Marks be directed to remove the following goods in class 3 from the registration of Trade Mark Registration No 1375954 (the Second Trade Mark):

shaving preparations, shaving creams and soaps, after shave creams and lotions.

6. The cross-claimants’ Notice of Cross-Claim filed 15 September 2015 be otherwise dismissed, save for the question of costs.

7. Within five (5) business days, the applicant serve a copy of these orders on the Registrar of Trade Marks.

8. The time for any application for leave to appeal from any of these orders be extended pursuant to r 35.13(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) to 4.00 pm on 21 September 2017.

9. The exhibits be returned to the parties 28 days after the final disposition of the proceedings, including applications for leave or special leave to appeal and any appeals.

10. Within 28 days the applicant file and serve submissions in relation to costs.

11. Within 14 days thereafter the respondents file and serve their submissions in response.

12. Any submissions in reply be filed and served 7 days later.

13. Pursuant to s 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), in order to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, until further order the following information not be published or disclosed to any person apart from the parties and their lawyers:

(a) The numbers and amount referred to in [363];

(b) The amount referred to in [364];

(c) The percentages referred to in [472] and [473];

(d) All words after “Oval Cushion Brush” in the second sentence, and all words after “Radial Brushes” in the third sentence of [569];

(e) The amounts mentioned in the first sentence and the percentage referred to in the second sentence of [570]; and

(f) The amounts referred to in the second sentence of [571].

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Schedule

1. Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1)

| 2. Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1)

|

3. Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1/Version 2)

| 4. Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1)

|

5. Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo

| 6. Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo

|

7. Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo

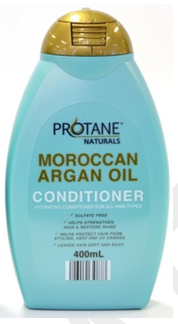

| 8. Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner

|

9. Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner

| 10. Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner

|

11. Moroccan Argan Oil Dry Shampoo

| |

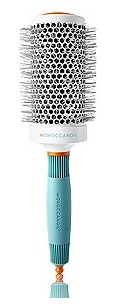

12. Moroccan Argan Oil Brushes

| |

13. Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Dryer

| |

14. Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Straightener

| |

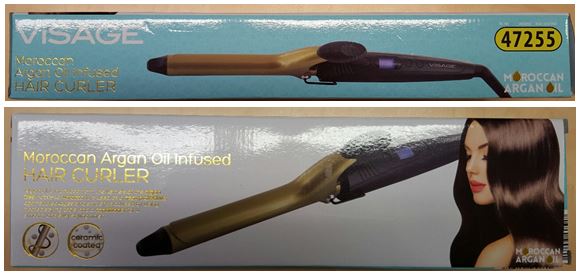

15. Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Curler

| |

ORDERS

NSD 1297 of 2015 | ||

Applicant | ||

AND: | ALDI FOODS PTY LIMITED (ACN 086 210 139) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | KATZMANN J | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 JULY 2017 | |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The decision of the Registrar given by her delegate on 9 October 2015 be set aside.

3. The respondent’s notice of opposition to the applicant’s Australian trade mark application no. 1463962 be dismissed.

4. The applicant’s trade mark, moroccanoil, proceed to registration.

5. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the appeal and of the opposition proceeding below.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of contents

[3] | |

THE FACTS | [8] |

The MIL Business | [9] |

The MIL Trade Marks | [11] |

MIL’s Get-Up | [21] |

The Aldi business | [25] |

Aldi’s Get-Up | [29] |

The development of the Aldi Product Range | [40] |

Consumer complaints | [54] |

The expert evidence | [79] |

THE APPLICATION TO RELY ON TENDENCY EVIDENCE | [103] |

The alleged tendency | [111] |

Did MIL give Aldi reasonable notice of its intention? | [114] |

Does the evidence have significant probative value? | [119] |

Conclusion | [130] |

THE TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT CASE | [131] |

Has Aldi used the sign “Moroccan Argan Oil” as a trade mark? | [137] |

Is the sign “Moroccan Argan Oil”, as used, deceptively similar to the MIL registered trade marks? | [166] |

Are the Aldi Hair Brushes and Aldi Hair Tools goods in respect of which the MIL trade marks are registered or goods of the same description? | [221] |

Has Aldi established that the use of the signs as Aldi did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion? | [228] |

If infringement is made out, is Aldi liable to pay additional damages under s 126(2) of the Trade Marks Act? | [229] |

Conclusion | [230] |

ALDI’S CROSS-CLAIM FOR RECTIFICATION OF THE REGISTER | [231] |

The legislative basis for the claim for cancellation of the MIL marks | [232] |

The claim for cancellation | [233] |

The issues | [234] |

Are the Trade Marks capable of distinguishing MIL’s goods from the goods of others? | [235] |

The claim for removal for non-use | [262] |

Conclusion | [325] |

THE CLAIMS MADE UNDER THE AUSTRALIAN CONSUMER LAW | [326] |

The first ACL claim — relationship | [330] |

The allegations | [330] |

The legislative provisions | [333] |

The issues | [335] |

The legal principles | [338] |

The question of reputation | [347] |

What was MIL’s reputation? | [350] |

Were any of the alleged representations made? If so, were they false, misleading or deceptive etc? | [370] |

The representations | [371] |

Did Aldi copy a MIL trade mark or the MIL get-up? | [376] |

Conclusion | [431] |

The second ACL claim — “naturals” | [432] |

The dispute | [432] |

Were the alleged representation made? | [439] |

Is the representation misleading or deceptive? | [464] |

Conclusion | [485] |

The third ACL claim — performance benefits | [486] |

The Aldi Oil Treatment, Shampoo and Conditioner | [488] |

Did Aldi represent that argan oil made a material contribution to the performance benefits of these products? | [488] |

Are the representations false, misleading or deceptive? | [499] |

The Aldi Hair Brushes and Hair Tools | [541] |

Were the representations made? | [549] |

Are the representations false or misleading? | [566] |

Conclusion | [587] |

PASSING OFF | [588] |

THE APPEAL | [589] |

The proceeding before the Registrar of Trade Marks | [589] |

The nature of the appeal | [603] |

The evidence of the lexicographers | [605] |

Professor Zuckermann’s evidence | [609] |

Ms Butler’s evidence | [623] |

Issues | [630] |

Is the moroccanoil word mark inherently adapted to distinguish MIL’s goods in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered from the goods of other persons? | [633] |

Is the moroccanoil word mark to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish and otherwise capable of registration? | [678] |

Is the moroccanoil word mark otherwise capable of registration? | [717] |

Conclusion | [719] |

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS | [720] |

COSTS | [724] |

FINALISATION OF REASONS | [725] |

ORDERS | [727] |

The application for further injunctive relief | [728] |

The corrective notice | [741] |

Agreed declarations and orders | [747] |

1 “Like brands, only cheaper” is both an advertising slogan used by the German supermarket giant, Aldi, and its business model. This proceeding brings these business practices into sharp focus, as its genesis lies in concerns that some of Aldi’s products are not just “like brands” but deceptively like a particular brand and so contravene Australian trade mark and consumer protection laws. That brand is Moroccanoil.

2 The focus of the case is on both the labelling and get-up of Aldi’s “Moroccan Argan Oil” hair care products, brushes and tools, each of which contains some amount of argan oil. Argan oil is the oil extracted from the nut of the argan tree, a tree native to Morocco, which has apparently been used for centuries by Moroccan women as a hair and beauty product. It is reputedly rich in antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and vitamin E.

3 Some years ago two enterprising Israelis established a business selling a product containing argan oil under the sign “Moroccan Oil”.

4 In 2006, on a visit to a hairdressing salon in Israel, a Canadian tourist, Carmen Tal, received a hair treatment with a product called “Moroccan Oil”. Ms Tal was so taken with the product that she purchased all the bottles in the salon and began to distribute it in North America. She later acquired the worldwide rights to the product, including exclusive distribution, manufacturing, customer information, goodwill, and intellectual property. “Moroccan Oil” became “Moroccanoil”, the trade dress was redesigned, and the product took off like wildfire. In October 2007 a new company — Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (MIL) — was incorporated, and a range of hair care and beauty products became available for sale in a number of countries under the brand name moroccanoil. MIL’s hair care products, including an oil treatment, shampoo and conditioner, were launched in Australia in September 2009.

5 The business has been remarkably successful. moroccanoil hair care products are currently offered for sale in almost 80 countries. In over 20 of those countries MIL has expanded its line into skin care. In the wake of its success a number of other companies began selling hair and beauty products containing argan oil. Amongst them are the respondents (Aldi). Aldi sells a range of hair care products under the name “Moroccan Argan Oil”. Each of those products is also branded “protane® naturals” (protane naturals) or visage® (visage). MIL sued Aldi, contending that by its use of the “Moroccan Argan Oil” sign Aldi has infringed MIL’s registered trade marks, engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law, contained in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL), and is liable in tort for passing off. Aldi denied the allegations and retaliated with a cross-claim seeking the cancellation of the MIL trade marks.

6 The MIL registered marks are composite marks. The word mark moroccanoil is not registered in Australia. On 7 December 2011 MIL applied to the Registrar of Trade Marks to have the word mark registered but its application was unsuccessful. MIL appealed and the appeal was heard together with MIL’s trade mark infringement/ACL/passing off application.

7 I shall deal first with the trade marks infringement case and cross-claim, then the ACL and passing off case, and finally the appeal. But before doing so, it is necessary to set out some salient facts.

8 Some of the facts are agreed, some are not in dispute. Unless otherwise indicated, the summary below is uncontroversial.

9 MIL is an Israeli company. Since about late 2007, it has produced and sold hair care products in Israel, and, through distributors, in various other countries including Australia. In Australia sales of MIL products are effected exclusively through Privity Pty Ltd, trading as Haircare Australia. As at the time of the hearing the products were distributed to approximately 4,012 accounts. As at 21 August 2015 there were 24 active authorised online resellers in Australia.

10 MIL’s products have been marketed and advertised in Australia by various means including: since about January 2013, through MIL’s websites (www.moroccanoil.com and www.moroccanoil.com/australia); since about July 2012, on MIL’s Facebook page; by press releases sent by email to subscribers; in print and online media publications; and in editorial articles in print and online media publications. Publications in which advertisements have been placed in Australia and overseas include: Vogue, Instyle, Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, Russh, Marie Claire and L’Officiel.

11 MIL is the registered proprietor of two Australian trade marks. The First Trade Mark bears the registration number 1221017. It has a priority date of 24 January 2008. It looks like this:

12 The Second Trade Mark bears the registered number 1375954. It has a priority date of 4 August 2010. It looks like this:

13 Both the First and Second Trade Marks are registered in class 3 in relation to the following goods:

Hair care products, including oil, mask, moisture cream, curly hair moisture cream, curly hair mask, curly and damaged hair mask, rassoul mask, argan and saffron shampoo, hair loss shampoo, dandruff shampoo, dry hair shampoo, hair loss ampoules, dandruff ampoules, gel, glisten spray, mousse, conditioner, hair spray; skin care products in this class; skin cleansers; skin toners; skin moisturizers; anti-aging cream; eye cream; beauty masks; body creams; hand creams; non-medicated foot cream; eye makeup; foundation makeup; lip liner, lipsticks and lip balms; eyeliners; blushes; eye shadow; nail enamels; toiletries and cosmetics including shaving preparations, shaving creams and soaps, after shave creams and lotions, body massage creams and oils, soaps, bath oils and shower gels, talcum powders; antiperspirants; dentifrices; sunscreen and suntan oils and creams; fragrances in this class, including perfumes, colognes, essences and essential oils.

(Emphasis added.)

14 In the period between their respective filing dates and 15 August 2015, however, MIL did not use either the First Trade Mark or the Second Trade Mark in respect of any of the goods emphasised in the previous paragraph.

15 On 7 December 2011 MIL filed an application to register the word mark moroccanoil (the Third Trade Mark).

16 The application was made in class 3 in relation, amongst other goods, to:

Hair care products, including oil, mask, moisture cream, curly hair moisture cream, curly hair mask, curly and damaged hair mask, argan and saffron shampoo, hair loss shampoo, dandruff shampoo, dry hair shampoo, gel, mousse, conditioner and hair spray.

17 The Third Trade Mark was accepted for possible registration in respect of the above-listed goods and the official notice of acceptance was published in the Australian Official Journal of Trade Marks on 18 October 2012.

18 On 16 January 2013 Aldi filed a notice of opposition.

19 On 9 October 2015, a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks refused the application on the basis that the ground of opposition under s 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) was established. In short, he found that the Third Trade Mark, which I shall generally refer to as the word mark, was a sign that was not inherently adapted to distinguish MIL’s goods and was not otherwise registrable under s 41(6).

20 MIL filed a notice of appeal on 29 October 2015.

21 “Get-up” refers to the style, appearance and trade dress of goods. In JB Williams Co v H Bronnley & Co Ltd (1909) 26 RPC 765 at 773 (CA), Fletcher Moulton LJ defined the get-up of an article as “a capricious addition to the article itself”. It includes colours, shapes, and packaging.

22 MIL asserted, and I accept, that the get-up of its product and packaging is distinctive. In its own words, it “includes the predominant use of turquoise blue with white writing and a prominent letter M in orange on the product labelling and packaging”, featuring, in the case of its hair care products, one or both of the First and Second Trade Marks, and, in the case of its moroccanoil Treatment (MIL Oil Treatment), dark brown glass bottles (described in submissions as “apothecary-style”).

23 The table below depicts the get-up of the MIL Oil Treatment from 2010 until the time of the hearing.

Table 1: MIL Oil Treatment

Period of use | Product packaging |

From September 2009 to around July 2010 |

|

From around July 2010 to late 2010 |

|

Between 2011 and 2012 | |

From 2012 to the present |

|

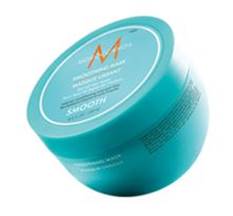

24 Images of the other MIL products currently sold in Australia are displayed in Annexure A to these reasons. Descriptions of the products appear in Annexure B.

25 The two respondents are, respectively, the general and limited partners of the Aldi stores (the Aldi Partnership). The Aldi Partnership is the partnership through which Aldi conducts its business in the Australian market.

26 From about 26 September 2012, the Aldi Partnership has periodically offered for sale and sold in Australia hair care products depicted in the tables in paragraphs 29, 30, 34, and 35 below (collectively, the Aldi Product Range). Images of the products in the Aldi Product Range also appear in Annexure A to these reasons, and descriptions of the products appear in Annexure B.

27 With two exceptions, all products in the Aldi Product Range were sold in “Special Buy” promotions. Special Buy products are heavily discounted. They are offered for sale for a limited time on the basis of limited stock and are sold until stock runs out. They are displayed for sale in a dedicated Special Buy area located in the central section of each Aldi store in what one of Aldi’s witnesses described as “the wire cage section”.

28 At all material times the vast majority of products sold in Aldi stores have been Aldi exclusive brand products. As at 30 October 2013, around 8.4% of the core and seasonal goods offered for sale in Aldi stores across Australia did not fall into that category. Twelve months later, the figure was slightly larger at 8.99%. By 30 October 2015, it had risen to 9.45%.

29 From about 26 September 2012, the Aldi Partnership has periodically offered for sale and sold in Australia a hair treatment product containing argan oil (the Aldi Oil Treatment). The table below depicts the variants of the packaging for this product. The product was offered for sale (and sold) in a number of “Special Buy” promotions commencing on the dates indicated in the table.

Table 2: Aldi Oil Treatment

Dates offered for sale | Product packaging |

26 September 2012 2 January 2013 11 May 2013 |

|

25 September 2013 1 January 2014 23 April 2014 |

|

24 September 2014 31 December 2014 25 April 2015 |

|

23 September 2015 |

|

30 The next table depicts the variants of the packaging for other products in the range as sold in the Special Buy promotions commencing on the dates indicated.

Table 3: PROTANE NATURALS Product Range

Product | Date offered for sale | Product packaging |

protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo / Conditioner (each 400ml) | 26 September 2012 2 January 2013 11 May 2013 |

|

25 September 2013 1 January 2014 23 April 2014 |

| |

24 September 2014 31 December 2014 |

| |

protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Renewing Treatment Mask (240 ml) | 25 September 2013 1 January 2014 |

|

24 September 2014 31 December 2014 25 April 2015 |

| |

23 September 2015 |

| |

protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Heat Protection Spray (250 ml) | 23 April 2014 |

|

31 December 2014 |

| |

protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Hair Spray (213 g) | 23 September 2015 |

|

protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Dry Shampoo (178 g) | 23 September 2015 |

|

31 The products depicted in the above tables are goods in respect of which the First and Second Trade Marks are registered.

32 From 10 April 2015 to approximately 8 December 2015 the protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo and Conditioner were sold as part of Aldi’s “core range” in the following packaging:

33 Core range products are available for sale every day and are regularly stocked in Aldi stores. The Shampoo and Conditioner were sold on shelves in the health and beauty sections, usually on the back wall of the store.

34 The table below depicts the hair brushes included in the Aldi Product Range (Aldi Hair Brushes). Each of these products was sold in the Special Buy promotions commencing on the dates indicated.

Table Four: Aldi Hair Brushes

Date offered for sale | Product/Product Packaging |

25 April 2015 |

|

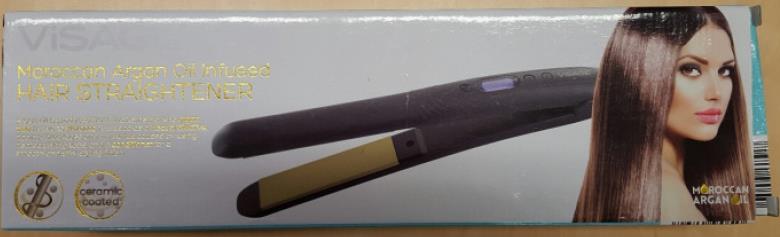

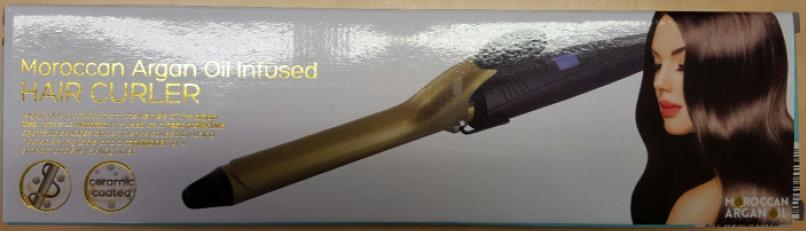

35 The next table depicts the Hair Dryer, Hair Straightener and Hair Curler forming part of the Aldi Product Range (Aldi Hair Tools). Each of these products was offered for sale in the Special Buy promotions beginning on the dates indicated.

Table 5: Aldi Hair Tools

Product | Date offered for sale | Product Packaging |

visage Moroccan Argan Oil Infused Hair Dryer | 17 September 2014 23 September 2015 |

|

visage Moroccan Argan Oil Infused Hair Straightener | 17 September 2014 23 September 2015 |

|

visage Moroccan Argan Oil Infused Hair Curler | 17 September 2014 23 September 2015 |

|

36 As at 15 September 2015 the Aldi Oil Treatment was being sold in 374 Aldi stores in metropolitan and regional centres of New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, and Victoria.

37 Items from the Aldi Product Range have been advertised in a variety of ways: through catalogues in the case of its Special Buy promotions; on the Aldi website at the domain name aldi.com.au; in newsletters; on Aldi’s Facebook page during the period from 31 December 2013 to 23 September 2014; and in NSW, on 23 and 24 April 2015, in a television commercial.

38 The catalogues were distributed to members of the Australian public through Aldi’s stores and delivered to homes in the above-mentioned States and Territories. Each month in the period from July 2013 to September 2015 the Aldi website received between about 900,000 and 1.5 million visits from Australian IP addresses. The newsletters were sent by email to consumers who subscribed to a mailing list via the Aldi website or microsites operated by Aldi for limited promotional periods in connection with the respective Special Buy promotion(s) in which they were sold. As at December 2015 there were approximately 295,000 consumers on the Aldi website mailing list.

39 On 8 December 2015, however, the protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo and Conditioner were replaced by shampoo and conditioner labelled “protane naturals Argan Oil of Morocco”. By January 2016 Aldi had substituted the name “Argan Oil of Morocco” for “Moroccan Argan Oil” on all of the products in the range and, with the exception of the shampoo, also changed the colour of the packaging.

The development of the Aldi Product Range

40 Evidence about the development of the Aldi Product Range was given on Aldi’s behalf by Meagan Spinks.

41 Ms Spinks began working for Aldi in July 2011. She was employed as a buying assistant in the Corporate Buying Department under the supervision of Deborah Heng, the buying director. Ms Spinks was responsible, among other things, for hair care products. In that role she assisted in the development of new products.

42 Ms Spinks said that, once “a new and interesting trend” is identified, she seeks out what “other competitor products” are available on the market that are part of the trend. She said that in her experience Aldi’s practice was to introduce its own “version” of a product in “an on-trend product category”. In developing “Aldi versions” of these products, the packaging used by competitors is considered in order to ensure that the Aldi “house brand” packaging was “consistent with” the trend. As part of this process, a “benchmark” product is selected from a range of “on-trend products”. The purpose of identifying a benchmark, Ms Spinks explained, is to enable Aldi to identify “cues” that customers may associate with “the product type generally” and then adapt them. In cross-examination she clarified that by cues she meant colour; wording associated with the benchmark product, including product description; claims of benefits associated with the product; and packaging. Ms Spinks was at pains to point out that, when undertaking that process herself, she “consciously set out to ensure that the product being developed is dissimilar to the benchmark product as a brand”. In this respect she adverted to the prominent use of the Aldi brand name protane. The object of the exercise, she said, was to ensure that the Aldi product was consistent with Aldi’s “main ‘pitch’ to its customers”, captured in its advertising slogan: “Like Brands. Only Cheaper”.

43 According to Ms Spinks, this was the process deployed in the development of the Aldi Product Range.

44 By mid to late 2011 Ms Spinks concluded that health and beauty products containing argan oil were “on trend”. At the time, she said that the following products containing argan oil were available in Australia:

Organix Moroccan Argan Oil, Shampoo and Conditioner (and possibly other products in the Organix range);

MIL’s moroccanoil products, including at least the MIL Oil Treatment, Shampoo and Conditioner;

Pure Oil of Marrakesh;

Dontay Aria Argan Gold range of products, including at least an oil treatment, shampoo and conditioner;

Maijan Moroccan Argan Oil;

One & Only Argan Oil treatment by Babyliss;

Showpony Moroccan Argan Oil;

NAK Aromas Oil, including at least an oil treatment, shampoo and conditioner;

BabylissPro, including at least an oil treatment, shampoo and conditioner; and

Lee Stafford ArganOil of Morocco.

45 This evidence was not contested and I accept it. In cross-examination, Ms Spinks acknowledged that the MIL Oil Treatment was the market leader in oil treatment products.

46 It is not clear that Ms Spinks was aware of all these products at the time Aldi developed the Aldi Product Range. What is clear is that she was aware at that time of MIL’s products and of the Organix range. She said she had used both the MIL Oil Treatment and the Organix range before her marriage in 2010 and had seen MIL products in magazines and hairdressing salons, sometimes in the windows of the salons.

47 By late October or early November 2011 Ms Heng instructed Ms Spinks to proceed with the development of a range of argan oil hair care products to be sold under the protane naturals brand. To this end Ms Spinks contacted a number of Aldi’s suppliers and invited them to submit proposals for a number of products including a “Moroccan oil ALDI Private Label Protane” product. She received several responses and, in consultation with Ms Heng, settled on one in particular.

48 Ms Spinks then set about preparing product advice statements and arranged for the development of the packaging and labelling. In settling on the artwork for the Aldi products, however, she said that she was concerned to ensure that they looked “sufficiently different”. She deposed that her preferred option answered that description. She nominated 11 points of difference in particular:

(1) the prominent M and the name moroccanoil appearing in white in a vertical position on the MIL product;

(2) the rectangular label on the MIL product in contrast to the “semi-circular top” on the Aldi label;

(3) the presence of the protane logo on the Aldi product, indicating a different brand;

(4) differences in the layout of the text on the labels: all horizontal on the Aldi label and a mixture of vertical and horizontal on the MIL label;

(5) the greater prominence on the MIL label of the word moroccanoil in comparison to the phrase “Moroccan Argan Oil” on the Aldi label;

(6) differences in the respective fonts;

(7) the use of ticks instead of bullet points on the Aldi label;

(8) the use of black and white in the marketing text on the MIL label in contrast to the use of black only in the text on the Aldi label;

(9) the use of a sticker joining the lid to the bottle on the MIL product;

(10) the fact that the Aldi product was to be sold with a pump attached whereas the pump for the MIL product was separate; and

(11) MIL’s use of a glass bottle when the Aldi product was to be sold in a plastic bottle.

49 Ms Spinks suggested that the phrase “Moroccan Argan Oil” be in lower case (including the “M”) “so that it is not the same as the brand” in order to avoid “legal issues”, although she frankly acknowledged in her affidavit that she did not regard the change of case to be “all that significant”. In the first and second versions of the Aldi Oil Treatment the phrase appeared in this way but in the third and fourth versions of the product upper case letters were deployed and an oil drop was substituted for the first “o” in “Moroccan” and the “o” in “Oil”.

50 Ms Spinks also said that when the colour choice was made, the colour selected was different from the colour in the get-up of the MIL Oil Treatment.

51 In cross-examination Ms Spinks agreed that Aldi’s policy objective was “to match the clear market leader in quality attributes including size and packaging design cues”. Ms Spinks said that it was her intention to replicate the benchmark product but in a way that would distinguish the Aldi product. She said that her rule of thumb was to have “at least 10 points of difference”. She said that her intention was to make the Aldi product look like other products but not exactly like them. Her aim, she claimed, was to ensure that, if the Aldi product was sitting side by side on a shelf with the MIL product, you could tell them apart — notwithstanding that the products are never sold in that way. This was presumably the “sufficient difference” to which she referred in her affidavit.

52 Little evidence was given about the development of the appliances. Ms Spinks said that this was outside her area of responsibility and within the portfolio of another buying director, Chris Raju. She said that Ms Heng told her in about 2013 that she had spoken to Mr Raju, he said that “he could do a range of heated hair styling tools which have argan oil infused in them” and that it would be a good idea to have them sold together with protane naturals Moroccan Argan Oil products in the same Special Buy promotion. She asked Ms Spinks to help Mr Raju’s buying assistants to source the oil and to send her a copy of the latest artwork for use in their products. Ms Spinks said that she provided the assistant with some examples of the artwork for the packaging for the “Protane Oil Range” but nothing more.

53 No evidence was given by either Ms Heng or Mr Raju, and Aldi offered no explanation for their absence. Ms Spinks testified that Ms Heng was alive and well and living in Sydney. I infer that nothing either of them could say would have assisted Aldi’s case.

54 Daniel Gavin Baker, Aldi’s Quality Assurance and Corporate Responsibility Director, gave evidence about Aldi’s electronic record of “feedback” received from customers. Mr Baker deposed that he had reviewed the database at the request of Aldi’s solicitors to see if there was any record indicating that a consumer had confused or otherwise associated any product in the “Moroccan Argan Oil” line with products sold by MIL under the moroccanoil brand. In fact, he delegated that task to the Customer Department Manager, Rania Faraq, who produced a report, which was annexed to Mr Baker’s affidavit. The report showed that there was none. Mr Baker was not required for cross-examination and there is no reason to disbelieve him. Indeed, MIL accepted his evidence. Accordingly, I find that from the time Aldi launched the Aldi Product Range until April 2016, when Mr Baker’s affidavit was filed, Aldi did not receive a single report that a customer had confused any of the products in the range with any MIL product.

55 MIL, on the other hand, adduced evidence from a number of witnesses of apparent “confusion”.

56 Evidence of “confusion” was given by three MIL employees: Violet Sainsbury, MIL’s International Education Manager in the Asia Pacific; Abbie Williamson, an International Brand Manager for MIL; and Kayla Juhasz, MIL’s Director of Brand Managers International and former Brand Manager for Australia and New Zealand. Evidence of this kind was also given by three hair stylists: Nicole Abela, Orla Fogarty, and Courtney Jane Spreen.

57 Further evidence was also given by two employees of Haircare Australia, the sole distributor of MIL products in Australia. They included the NSW State Manager, Thierry Fayard, and a sales representative, Christopher Clegg.

58 Direct evidence of apparent confusion, if not deception, was led from one Mony Royds, a mother of young children, who described an episode when she purchased the Aldi Oil Treatment and Shampoo, claiming to have mistaken them for MIL’s products.

59 Ms Sainsbury reported that from the time she started working for MIL in 2012 and, in particular, during the period from 2012 to the end of 2014 when she was conducting in-salon education, she became aware of “many instances” of consumers mentioning that they had purchased “the MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL Products” from an Aldi supermarket. She was unable to recall any details, however, except for one occasion when she was setting up for an in-salon education class. On that occasion, Ms Sainsbury said, a client of the salon said to her as she was leaving: “Oh, I saw Moroccanoil at Aldi”. Ms Sainsbury disabused her, assuring her that “the MOROCCANOIL Products are not sold at supermarkets”.

60 Mr Fayard deposed that in September 2012 one of Haircare Australia’s customers telephoned to complain that clients had seen the MIL Oil Treatment advertised at Aldi at a cheaper price. Mr Fayard did not keep a record of the conversation and could not recall the identity of the caller. Although he handled inquiries from between 500 and 600 salons, had no record of the conversation, and could not recall the caller’s identity, he said that he recalled a conversation to the following effect:

Caller: “Thierry, I am very disappointed. I have been told by clients of mine that they have seen the MOROCCANOIL Treatment product advertised at Aldi at a cheaper price. If you are going to supply Aldi with the MOROCCANOIL Treatment product, I don't want to deal with your company anymore.”

Fayard: “Hold on. I can guarantee you that we aren't supplying Aldi with the MOROCCANOIL Treatment product. Let me look in to this for you. I will get back to you as soon as I can.”

61 Mr Fayard also said that, within about a month of that call, he received similar complaints from “four or five other customers” in NSW and that “10 to 20” salon owners or employees complained to him about the Aldi Oil Treatment at around the time they were offered for sale as “Special Buys” at Aldi stores in the State. Once again, however, he was unable to recall the names of the people or their businesses.

62 On 11 May 2013 a post appeared on the website www.productreview.com.au concerning the MIL Moisture Repair Shampoo. It read:

This is a great shampoo & conditioner & if you are lucky enough to get it when it is in special at Aldi’s, grab plenty. It is a real bargain. I got some today & should keep me going until the next catalogue. It really does make a difference to you hair, but I couldn’t afford to pay the top dollars. Aldi’s is the same product but quarter then price. Thanks Aldi.

+ It makes my hair feel thick and shiny

63 Mr Clegg, a sales representative at Haircare Australia, visited the Evolve Salon between July and September 2013. Mr Clegg deposed to speaking there with Nerina Schiliro, the mother of the owner of the salon, who told him that they had not been selling many Moroccanoil products recently because Aldi was selling them at a much cheaper price. When Mr Clegg remonstrated with her that Aldi did not sell Moroccanoil products, she insisted that it did, telling him that a customer had told her that she had bought the MIL Oil Treatment from Aldi.

64 In April 2014 after being shown the full range of MIL products at the Zowie Evans Hairdressing salon in Melbourne, a client of Courtney Spreen reported seeing Moroccanoil products at Aldi.

65 Three months later, in July 2014, a client of the salon “Stylize Professional Haircut and Colour” in Little Lonsdale Street in Melbourne, told Abbie Williamson that she had recently bought products in Aldi that “look like MOROCCANOIL products”.

66 Between 15 and 17 July 2014 five salon owners or employees in regional Victoria reported to Ms Williamson that they had clients who told them they had purchased the MIL Oil Treatment from Aldi stores. Consequently, she visited five Aldi stores in Melbourne and purchased some of its Moroccan Argan Oil products. On or about 17 July 2014 she emailed Sarah Linder (of MIL) in Israel, notifying her of these conversations and of her purchases.

67 The following year, in May 2015, during the Sydney Fashion Weekend, which curiously ran for four days, Ms Williamson said that she was told by “at least three clients a day” that they had either bought from Aldi or had seen in Aldi stores, the MIL products, in particular, the MIL Oil Treatment, but also the MIL Shampoo, Conditioner and Mask. Ms Williamson deposed that the conversations were to the following effect:

Comment #1: “I have definitely bought this at Aldi.”

Comment #2: “What I bought from Aldi has the same colour blue packaging and dark brown bottle.”

Comment #3: “They look the same.”

Comment #4: “I didn't know that the MOROCCANOIL Product was available in Aldi until I saw it when I was shopping there recently.”

Comment #5: “Your products are cheaper in Aldi.”

68 Ms Williamson not only disabused these “clients” but encouraged them to photograph the MIL products so that they knew exactly what to look for when they were in a salon.

69 Other MIL employees had similar experiences at the same event.

70 At least five women at this event told Nicole Abela, who was working at the MIL booth (known as the “Moroccanoil Styling Suite”), that they had purchased or seen certain MIL products at Aldi stores.

71 On 16 May 2015 Courtney Spreen, who was also working in the Moroccanoil Styling Suite, asked a woman in her mid-20s whose hair she was styling whether she had used the MIL Oil Treatment before, the woman replied: “Yes, I used to get that from Aldi”.

72 The same day, Kayla Juhasz had a conversation in the Moroccanoil Styling Suite with a woman who insisted that she had purchased both the MIL Oil Treatment and the MIL mask from Aldi and that during the conversation the woman was pointing to those products on the display stand. That conversation was to the following effect:

Ms Juhasz: “Hi, my name is Kayla. Have you heard of MOROCCANOIL?”

Woman #1: “Yes, I've got MOROCCANOIL.”

Ms Juhasz: “Great. Where is the salon you buy it from?”

Woman #1: “No, I buy it from Aldi.”

Ms Juhasz: “MOROCCANOIL Products are only available for sale at salons and are not available for sale at Aldi. If you like, I can provide you with a toll free number to assist you to locate your nearest MOROCCANOIL stockist. Can I ask you which products you purchased?”

Woman #1: “I'm sure that I bought the products from Aldi. I bought the oil and the Mask as well. I bought it for my daughter, she absolutely loves it.”

73 Ms Juhasz said that she also had a conversation with another woman who told her that she bought her daughter the MIL Oil Treatment. Ms Juhasz said that she pointed out the MIL Oil Treatment to the woman’s daughter who told her that it had been recommended by her hairdresser and that she had it at home: “it’s the same brown bottle”. When Ms Juhasz asked where she had bought it, her mother replied that she had bought it at Aldi. When Ms Juhasz told her that the product was not available for sale at Aldi, the mother replied:

Does that mean the one I bought wasn’t the real MOROCCANOIL product? I thought it was a lot cheaper, but thought it must have been on sale.

74 In July 2015 Mony Royds, purchased the Aldi Oil Treatment and Shampoo from Aldi's Leichhardt store believing that they were MIL products.

75 Some time earlier Ms Royds had purchased the MIL Oil Treatment once and used it regularly for a while. She said that she was also aware of other MIL products, including shampoos and conditioners, but had never bought any. One weekend in July 2015, accompanied by her husband and two young children, she was shopping at an Aldi store in Leichhardt, an inner western suburb of Sydney, when she spotted what she believed to be MIL products. She said that the store was “very busy and crowded and difficult to navigate with a trolley”. As she headed towards the section of the store where the toiletry items were displayed, she said she noticed from a distance “a block of turquoise blue products” located just below eye level on one of the shelves. She said she thought immediately of the MIL products and that when she drew closer to the turquoise blue products, she saw the words “Moroccan” and “Oil” on their labels, she concluded that the products on display were the MIL Oil Treatment and a MIL Shampoo. She recognised that the branding and get-up of the products were different, but she thought that the MIL products might have undergone “some rebranding exercise (as brand name products tend to do from time to time) because the shade of blue on the packaging of the products was slightly different from the shade of blue that [she] recalled seeing in the past”. Without any further thought, she put (what she later discovered were) the Aldi Oil Treatment and the Aldi Shampoo into her trolley. She estimated that she spent less than a minute in this part of the store before moving on. She said that she did not recall seeing the prices but assumed that they would be less than the prices of the products in a salon. She paid no attention to the receipt on purchase.

76 Every day for the following two weeks Ms Royds used the Aldi Oil Treatment on her daughter’s hair, still thinking she was using the MIL Oil Treatment. She only realised her mistake two weeks after purchase when she noticed “an unpleasant chemical smell” when using the Aldi Shampoo for the first time. She said:

28 Once I noticed the smell, I inspected the packaging of the Aldi MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL Shampoo product more closely and formed the view that I had not in fact bought a MOROCCANOIL Shampoo product, but a cheaper imitation, which had the words “Protane Naturals” printed on the label.

29 I did not notice the words “Protane Naturals” in the store as the black text of “Protane Naturals” did not jump out at me. The words “MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL” did. The words “Protane Naturals” are also quite small when compared to the words “MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL”. Given the chemical smell of the product, I thought that “Protane” might be a chemical ingredient used in the Aldi MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL Shampoo or a brand name, but did not think much more about it at the time.

30 Once I had realised that I had not purchased a MOROCCANOIL Shampoo Product, I also inspected what I now know to be the MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL Treatment Product more closely. At this point, I realised that the product that I was using in my daughter's hair was not the MOROCCANOIL Original Treatment Product …

77 On 26 August 2015, while Ms Royds was having her hair coloured by Ms Abela at LSG Creative, they had a conversation to the following effect:

[Ms Royds]: “Nicole, I have been using an argan oil product on my daughter’s hair and it has become ridiculously dry and flaky.”

[Ms Abela]: “What product have you been using? You know the MOROCCANOIL Products won’t do that.”

[Ms Royds]: “No, it wasn’t the original, sorry. It was the Aldi version of the MOROCCANOIL Original Treatment Product. I tried to use the oil to detangle the knots in my daughter’s hair and it gave her a really dry scalp.”

[Ms Abela]: “Well the MOROCCANOIL Products are not sold at Aldi, they are only available for sale at salons.”

[Ms Royds]: “I’m aware of that now. The blue was almost exactly the same as the MOROCCANOIL Products. It really did look the same on the shelf![”]

[Ms Abela]: “Alright, don’t throw the product away. I’d actually like to see it. Can I see it when I come to your house next?”

[Ms Royds]: “I already threw the Aldi MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL Treatment product away. I won’t be using it again. I bought the Aldi MOROCCAN ARGAN OIL shampoo though. I can show it to you when you come around for my birthday party.”

78 The final piece of evidence upon which MIL relies to establish confusion came from Ms Fogarty. On or around 23 September 2015 she was using the MIL Oil Treatment on a client’s hair. When she asked the client whether she had used it before, the client told her she had and that she had bought it from Aldi. Although she had a clear memory of the discussion with the client, she could not identify her and, since the client had not previously attended the salon and had not made an appointment, she had no documents to assist her recollection in this respect.

79 Expert evidence was adduced in three specialist areas: lexicography, marketing, and industrial chemistry. With the exception of the lexicographers who were prevented by logistical difficulties from doing so, the expert witnesses in each field testified in concurrent session.

80 The two lexicographers, Ghil’ad Zuckermann and Susan Butler, gave evidence touching upon the use of the terms “Moroccanoil” and “Moroccan Oil” as at the priority dates for the three MIL trade marks. A summary of Professor Zuckermann and Ms Butler’s experience and qualifications is set out below at [606] and [607] respectively.

81 Four marketing experts gave evidence about marketing practices and consumer behaviour.

82 MIL adduced evidence from Mr Paul Blanket and Professor Pascale Quester. It would be fair to describe Mr Blanket as a marketing practitioner and Professor Quester as a marketing academic.

83 Mr Blanket is the principal of the company First Impressions Pty Ltd, which, since 1987, has carried on business providing marketing, advertising and promotional consulting services to industry and government. Mr Blanket has a both a Bachelor and a Master of Commerce Degree (Marketing) from the University of New South Wales and completed the University of Melbourne’s Management Program as well as the FCB Advanced Advertising Program in Chicago run by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is also a Fellow of the Australian Marketing Institute and is a Certified Practising Marketer.

84 Mr Blanket formerly worked as a Group Account Director with the advertising agency Foote, Cone & Belding, and has worked in various marketing positions at Unilever Australia Pty Ltd. He described his work as involving advising on the development of new products and brands or “repositioning” an existing product or brand in a particular market. As part of his commercial experience, Mr Blanket was involved in or commissioned approximately 100 qualitative and quantitative research studies for brands such as British Airways, Vitasoy, Melitta Coffee, New Zealand Natural Ice Cream, Randstad Recruitment, Australian Egg Corporation and Waste Service New South Wales.

85 Mr Blanket is also a lecturer in advertising and marketing at the Macquarie Graduate School of Management, having lectured in various courses since 1992 including “Advertising and Promotions Management” and “Marketing Management”.

86 Professor Quester is the inaugural Professor of Marketing and Head of Discipline (Marketing) in the School of Commerce (now the Adelaide Business School) at the University of Adelaide. She holds a Bachelor of Business Administration from Audencia in Nantes, one of the top three business schools in France, a Master of Arts in Marketing from Ohio State University in the United States of America, and a PhD in Marketing from Massey University in Palmerston North, New Zealand. She is also a Certified Practising Marketer, a Fellow of the Australian Marketing Institute, a Distinguished Fellow of the Australia and New Zealand Academy of Marketing, and Founder of the Franco-Australian Centre for International Research in Marketing.

87 Professor Quester has been employed by the University of Adelaide since at least 1991, initially as a lecturer in marketing in the Graduate School of Management, then senior lecturer and later Associate Professor in Marketing in the School of Commerce, before being appointed in 2002 to her current position. Over the years she has held appointments as a Visiting Professor in a number of universities in France. She has taught various aspects of marketing and a course in consumer behaviour to both undergraduate and postgraduate students. Amongst many publications bearing her name, she is co-author of several leading textbooks on marketing and consumer behaviour. She is the lead author of Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Marketing Strategy, first published in 1994 and now in its 7th edition, and of Marketing: Creating and Delivering Value, first published in 1994 and now in its 5th edition. For a number of years she has been a member of the editorial boards of several marketing journals.

88 In addition to her academic achievements, Professor Questor is the Director of Hexagon, which, since 1997, has carried on business providing to both government and industry consulting services on consumer behaviour, marketing, advertising, and promotion as well as teaching material on consumer behaviour and marketing. From time to time she has also taken on small scale projects advising local firms on their marketing strategy.

89 Aldi led evidence from Jill Klein and John Heath Roberts, both marketing academics.

90 Professor Klein is a Professor of Marketing at the Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne, and has occupied that chair since 2009. Since 2015 she has spent half her time as a Professorial Fellow at Melbourne Medical School. She is a member of the Association for Consumer Research and the Society for Consumer Psychology. She currently lectures, amongst other things, in advanced consumer behaviour and decision making. She has conducted research in, amongst other things, how people form impressions of other people and products. Professor Klein has published many papers in the area, including in top tier social psychology and marketing journals. Recently, she has conducted research on consumer perceptions of brand labelling on packages to understand how consumers understand a sub-brand label.

91 From 1990 to 1997, Professor Klein was an Assistant Professor of Marketing at Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University, then one of the top business schools in the United States of America. During this period she also spent time as a Visiting Professor at various universities in in Australia, the United States, and elsewhere.

92 Professor Klein’s commercial experience includes consulting and executive education with international firms such as Ericsson, AstraZeneca, Servier, Syngenta, Toshiba, Adidas, Clemenger (an advertising agency) and Accenture. Her executive education teaching covers topics such as consumer behaviour and psychology, including brand image, consumer memory, information processing and consumer decision-making.

93 Professor Roberts is Professor of Marketing at the University of New South Wales School of Business. He is also a Fellow of the London Business School, Shanghai’s Fudan University, the Australian Academy of Social Sciences, the Australia and New Zealand Academy of Marketing, the Australian Institute of Management, the Australian Marketing Institute, the Australian Institute of Advertising, and the Australian Market and Social Research Society. He has worked as an academic since 1984 but he also has managerial experience, for example, in marketing, as Market Planning Director of Telecom Australia (now Telstra), then Australia’s largest company, in consulting as founder and Chairman of Marketing Insights (now part of Nielsen Research), and in market research as a Senior Research Officer in the Sampling and Methodology Branch of the Australian Bureau of Statistics. His areas of expertise include branding, forecasting and models of consumer behaviour, quantitative modelling, and marketing practice, including in the area of packaged goods.

94 His work has been recognised and acclaimed in numerous respects.

95 Professor Roberts also has extensive consulting experience for various companies, including IBM, DHL, Cerebos, Philips Electronics, Unilever, Kellogg (notably concerning “leverage points in the consumer decision process”), and MobilCom.

96 MIL led evidence from two industrial chemists, Dr Graeme Haley and Richard Williams. Dr Haley’s evidence went to the second and third ACL claims (the naturals claim and the performance benefits claim). Mr Williams was retained by MIL late in the piece and his evidence was restricted to the Aldi Hair Brushes and Hair Tools.

97 Dr Haley is an industrial chemist with 36 years’ experience in Australia and overseas formulating and manufacturing a wide variety of hair care products, with particular expertise in shampoos, conditioners, treatments, and hair styling products. He has a Bachelor of Science (Honours) majoring in polymer science and a PhD from the University of New South Wales, and a Graduate Diploma in Administration from the University of Technology Sydney. In 1993 he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Australian Chemical Institute a professional body for chemical scientists in Australia, and he is a member of the Australian Society of Cosmetic Chemists. He is the author of the Australian chapter of the Cosmetic, Toiletry and Fragrance Association International Regulatory Resource Manual (6th ed.) published in 2007.

98 Dr Haley has held various technical positions in companies that formulate and manufacture hair care products, including Beecham Australia Pty Ltd, Rexona Pty Ltd (working on the development of sunsilk and pears hair care products), and various companies associated with Unilever. Today Dr Haley is a director and consultant of Engel, Hellyer & Partners Pty Ltd, a consultancy firm that provides advice and other services to industry bodies in relation, amongst other things, to hair care products and their labelling. Dr Haley is also a member of two committees of Standards Australia, which concern the standardisation of labelling of personal care and hair care products in Australia.

99 Mr Williams has a Bachelor of Science from the University of New South Wales majoring in pure and applied chemistry and a Diploma of Environmental Studies from Macquarie University. While he does not have a PhD, he boasts 46 years’ experience in the hair care industry, most of which involved all aspects of production of hair care products, from concept to marketing. He said that a substantial part of his work as an industrial chemist has required him to use his knowledge and experience in chemical formulation to create hair care products based on a design and marketing brief. He is also a Fellow of the Australian Society of Cosmetic Chemists. From November 2007 until September 2012 he was the Research and Development Manager for NxGen Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd in Sydney and since then he has been the business director and principal scientist for Cosmopeutics International, a consultancy specialising in the development, regulation and production of high quality cosmetics and beauty therapies, amongst other things. He has also lectured from time to time in cosmetic chemistry, including in the formulation of cosmetic products.

100 Mr Williams formulated approximately 2000 personal care products across his career, of which a third have been hair care products. Approximately 50 of these products contained argan oil, including shampoos, conditioners, and treatment products, and, in early May 2016, when he swore his affidavit, he was in the process of formulating approximately 20 more.

101 Aldi relied on evidence given by Dr Paul Wynn-Hatton. Dr Wynn-Hatton works as a consultant to chemical manufacturing companies, and has experience in providing specialist advice on cosmetic products including hair care products. He has a Bachelor of Science (Honours) and a PhD in organic chemistry from the University of Sydney. Throughout his career he has been a member of the Australian Society of Cosmetic Chemists, the Royal Australian Chemical Institute and the Association of Therapeutic Goods Consultants.

102 Dr Wynn-Hatton’s experience in hair care products began in 1992 when he was employed by Reckitt & Colman. He worked there until 1997 on the review and improvement of the formulations of the Decore range of products. He later worked for a number of other companies including Glaxo Smith Kline, Pax Australia, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, where he worked on developing new claims for the Herbal Essences range of hair care products.

THE APPLICATION TO RELY ON TENDENCY EVIDENCE

103 On 18 May 2016 MIL gave notice under s 97(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) of its intention to adduce “evidence of character, reputation, conduct or tendency to prove that the [r]espondents have, or had, a tendency to act in a particular way, or to have a particular state of mind”.

104 Section 97(1) relevantly provides that evidence answering this description is not admissible to prove that a person has or had a tendency to act in a particular way or has a particular state of mind unless:

(a) the party seeking to adduce the evidence gave reasonable notice in writing to each other party of that intention; and

(b) the court thinks that the evidence will, either by itself or having regard to other evidence adduced or to be adduced by the party seeking to adduce the evidence, have significant probative value.

105 Paragraph (1)(a) does not apply in the circumstances set out in subs (2), but it is not suggested that any of those circumstances obtains here.

106 If the evidence is not admissible to prove the alleged tendency, then it cannot be used to prove it, even if it is relevant for another purpose: Evidence Act, s 95.

107 The rule in s 97(1), known as “the tendency rule”, does not apply to evidence that relates only to the credit of a witness. Nor does it apply to evidence of the character, reputation or conduct of a person or to a tendency that a person has or had if that character, reputation, conduct or tendency is a fact in issue: see s 94. But MIL did not submit that the evidence answered any of these descriptions.

108 The High Court explained in IMM v The Queen (2016) 257 CLR 300 at [45]:

The use of the term “probative value” and the word “extent” in its definition rest upon the premise that relevant evidence can rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue to different degrees. Taken by itself, the evidence may, if accepted, support an inference to a high degree of probability that the fact in issue exists. On the other hand, it may only, as in the case of circumstantial evidence, strengthen that inference, when considered in conjunction with other evidence.

109 The evidence in question is contained in annexure PJD-100 to the affidavit of Paul James Dimitriadis, one of MIL’s solicitors, affirmed on 24 December 2015. It consists of photographs of a number of Aldi’s “house brand” products alongside well-known brands, purchased from other supermarkets, which the Aldi products are said to closely resemble.

110 Aldi objected to the evidence. It contended that it was not given reasonable notice of MIL’s intention and that the evidence lacks significant probative value. Alternatively, it invited the Court to exercise its discretion to reject it because of the danger that its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that it might be unfairly prejudicial, be misleading or confusing, or cause or result in undue waste of time (see s 135). The parties did not seek a ruling at the time the evidence was adduced and were content for the matter to be dealt with in the judgment.

111 The tendency sought to be proved by this evidence was described in MIL’s notice as follows:

[Aldi] adopt and implement policies and strategies, and engage in consequential conduct, by which they copy, for use on Aldi house brand products, elements of the get-up of Third Party Branded Products, and, further or alternatively, do so intending that consumers will be attracted to purchasing the Aldi house brand products by the presence of similar diagnostic cues to those that make the Third Party Branded Products attractive to the same consumers.

(Emphasis added.)

112 In written submissions, however, MIL put the matter somewhat differently. Now, the evidence was said to be “a link in the process of proving that Aldi deliberately copied the get-up including trade marks of MIL’s branded products and/or it did so because those branded products had a reputation”.

113 Necessarily, this means that MIL’s contention is that the evidence in question would support a finding that:

(a) Aldi has a tendency to copy elements of the get-up of other brands;

(b) because of that tendency, it is more likely that it copied elements of MIL’s get-up on the products the subject of the proceeding; and/or

(c) Aldi’s purpose was to appropriate or capitalise on the reputation of the other brands.

Did MIL give Aldi reasonable notice of its intention?

114 In contrast to the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) (UCPR), the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) merely prescribe the form of the notice; they do not prescribe what constitutes reasonable notice. Some guidance might come, however, from the NSW position. There, notice must be given 21 days before the proceeding is fixed for trial: see UCPR, r 31.5.

115 The evidence in question was served in December 2015. On 10 May 2016 Aldi notified MIL that it would object to the Court receiving it. It appears that this was the trigger for the issue of the tendency notice for it was eight days later, on 18 May 2016, that the notice was sent. This was months after the time had expired for Aldi to serve its evidence, 12 working days before the trial was due to start, five months after MIL had filed and served its evidence in chief, three months after it served its evidence in reply, and 9 months after the proceeding was fixed for trial.

116 In my view the notice was not reasonable. It should have been given at the latest when MIL served Mr Dimitriadis’ evidence. That would have given Aldi a reasonable opportunity to investigate the allegation, interview relevant witnesses, and file evidence. In the absence of any indication as to the use to which MIL intended to put annexure PJD-100, it was no answer for MIL to say, as it did, that Aldi had been in possession of the evidence for six months. The evidence was prima facie inadmissible.

117 Furthermore, the notice itself was inadequate. A properly drafted notice should “explicitly identify the tendency sought to be proved” (Gardiner v R (2006) 162 A Crim R 233 at [128] per Simpson J), outline the specific conduct and its circumstances, and enable the party whose conduct is in question to meet the evidence: Martin v New South Wales [2002] NSWCA 337 at [91] (Giles JA). The description of the tendency in the notice lacked the necessary degree of specificity. As Aldi submitted, it did not clearly identify that MIL intended to argue that Aldi deliberately copied third party get-up on the basis suggested in MIL’s written submissions, namely, with the intention of appropriating the reputation of other brands or misleading consumers. Neither, I might add, did it identify the fact or facts in issue to which the evidence was said to relate.

118 For this reason alone I consider that annexure PJD-100 should not be admitted.

Does the evidence have significant probative value?

119 No evidence is admissible unless it is relevant (Evidence Act, s 56). Evidence is not relevant unless, if it were accepted, it could rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue in the proceeding (s 55).

120 The first task then is to identify the fact or facts in issue which the evidence has been adduced to prove.

121 MIL pointed to the allegations made in the current pleading that:

in adopting the sign “Moroccan Argan Oil” used on or in relation to each of the allegedly infringing products, Aldi “deliberately copied” the moroccanoil sign and/or one or both of its two registered trade marks;

the get-up of the Aldi Oil Treatment and the box in which it was packaged were both “deliberately copied” from the MIL counterpart;

the get-up of all of the products in the Aldi Product Range was “deliberately copied” from the get-up of the MIL products; and that

in each case Aldi acted in this way for the purpose of appropriating part of MIL’s trade or reputation or that of the authorised distributors and resellers of the MIL products; and

Aldi “flagrantly” infringed the MIL trade marks.

122 Each of these matters is denied. It follows that each is a fact in issue.

123 I accept that evidence that Aldi has a tendency to copy the get-up of other successful brands in order to appropriate part of their trade or reputation would at least be indirectly relevant to the question of whether it copied MIL’s get-up. If evidence that has been or will be given shows that Aldi copied the get-up of other well-known brands, that could rationally affect the assessment of the probability that it copied MIL’s. While there is no direct evidence in any of these other cases of “deliberate copying”, the similarity in the appearance of each of the 13 Aldi products and its respective third-party branded counterpart might support an inference to this effect. For the inference to be drawn, however, it would be necessary to point to evidence that the third-party branded products came on the market before Aldi’s and to show that the third-party brands had a reputation in the market at the time Aldi copied from them.

124 Evidence was adduced in cross-examination of Ms Spinks that three of the third-party brands — Old El Paso, Garnier Fructis and Lynx — are well-known, but there was no evidence to that effect about the other 10. Be that as it may, I accept that it is common knowledge at least in Sydney, which it is not reasonably open to question, that the other brands (Heinz, SPC, Kellogg’s, Colgate, Palmolive, Sanitarium, CSR, Pantene, Panadol and Arnott’s) are also well-known and well-established brands.

125 The evidence discloses that the first Aldi supermarket in Australia opened in 2001. On the other hand, there is no evidence as to when the third-party branded products came on the market.

126 Similarities in get-up are immaterial to a trade mark infringement claim. For this reason, even if the evidence supports the alleged tendency, the tendency could not be relevant to that claim, let alone be of significant probative value. The alleged tendency however, is, potentially relevant to the first ACL and passing off claims. But is it of significant probative value?

127 “Probative value” refers to the extent to which the evidence could rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of the fact in issue (Evidence Act, Dictionary). “Significant” in the context of the expression “significant probative value” means “important” or “of consequence” though less than “substantial”: R v Lockyer (1996) 89 A Crim R 457 at 459 (Hunt CJ at CL).

128 The assessment of whether the evidence in question has significant probative value involves two considerations: first, the extent to which the evidence supports the alleged tendency and second, the extent to which the tendency is capable of rationally affecting the assessment of the probability of the existence of these facts in issue: see Hughes v R [2017] HCA 20 at [41] (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane and Edelman JJ), and [89] (Gageler J).

129 As Aldi submitted, tendency evidence is generally used to prove, “by a process of deduction, that a person acted in a particular way, or had a particular state of mind, on a relevant occasion, when there is no, or inadequate, direct evidence of that conduct or that state of mind on that occasion”: Elomar v R [2014] NSWCCA 303; (2014) 300 FLR 323 at [360]. Here, however, there was direct evidence from Ms Spinks of the development process in relation to the goods in question. The evidence MIL wished to adduce as “tendency evidence” consisted merely of samples and images of other, unrelated products. It did not include any evidence as to how or why the get-up for the particular products was selected. It takes the evidence given by Ms Spinks no further. Consequently I am not persuaded that the evidence in question has significant probative value.

130 For these reasons the evidence is inadmissible to prove either alleged tendency. It is unnecessary in the circumstances to deal with Aldi’s alternative argument.

THE TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT CASE

131 Section 120 of the Trade Marks Act relevantly provides that:

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; …

…

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

132 “Use of a trade mark in relation to goods” is defined in s 7 as “use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods”.

133 The parties agree that the Aldi Oil Treatment and the Aldi Product Range (except the Aldi Hair Brushes and Aldi Hair Tools) are goods in respect of which both MIL trade marks are registered.

134 MIL alleges that Aldi has used the sign “Moroccan Argan Oil” as a trade mark upon or in relation to the containers and packaging of the Aldi Product Range, the packaging of the Aldi Hair Tools, and the handle and swing-tag of the Aldi Brushes, that they are used in relation to goods in respect of which the First and Second Trade Marks are registered or in relation to goods of the same description, and that the Aldi marks were deceptively similar to MIL’s two registered marks.

135 The following issues arise for consideration:

(1) whether Aldi has used the sign “Moroccan Argan Oil” as a trade mark in respect of the relevant products;