FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Warrie (formerly TJ) (on behalf of the Yindjibarndi People) v State of Western Australia [2017] FCA 803

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 3, “before the trial and then adopted” has been replaced with “before the trial. All of those parties, except Yamatji, adopted” | |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 3, a final sentence has been added: “Yamatji submitted, but did not dispute any of the matters for which the applicant contended.” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 48, “dreaming mediation” has been replaced with “dreaming meditation” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 52, second dot point, “Aboriginies” has been replaced with “Aborigines” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 79, “a sister” has been replaced with “an aunt” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 81, “grab a water and blow” has been replaced with “grab a water [sic] and blow” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 87, “her sister, Lorraine Coppin”, has been replaced with “her daughter, Lorraine Coppin” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 159, “photography shows” has been replaced with “photography show” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 241, the two spaces between “said :” have been deleted |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 262, the word “argum`ent” has been replaced with “argument” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 327, “seriously comprised” has been replaced with “seriously compromised” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 380, “finding did negate” has been replaced with “finding did not negate” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 391, “internal diversion” has been replaced with “internal division” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 469, “a[]” has been replaced with “[a]” |

21 August 2017 | In paragraph 491, “who was an anthropologist working for WMYAC” has been replaced with “who was an independent anthropologist engaged by the parties for the mediation” |

ORDERS

WARRIE (FORMERLY TJ) (ON BEHALF OF THE YINDJIBARNDI PEOPLE) AND OTHERS (AS PER THE SCHEDULE) Applicant | ||

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA AND OTHERS (AS PER THE SCHEDULE) First Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties consult and seek to agree and prepare a draft determination of native title for the Court to make under s 225 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to give effect to the reasons for judgment delivered today.

2. The proceeding be listed for case management on 17 August 2017 at 11.30am.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

[6] | |

[7] | |

[11] | |

[30] | |

[33] | |

[40] | |

[40] | |

[45] | |

[46] | |

[149] | |

[152] | |

[160] | |

[161] | |

[161] | |

[162] | |

[169] | |

[171] | |

[179] | |

[179] | |

[184] | |

Are any of the 1982, 1989 and 1992 licences within s 47B(1)(b)(ii)? | [193] |

[194] | |

[204] | |

[208] | |

[211] | |

[217] | |

[229] | |

[231] | |

Occupation – evidence of activities in areas 1 to 4 and the Reserve | [234] |

[253] | |

[258] | |

[289] | |

[303] | |

[304] | |

Leave to amend sought by the State and FMG – The Yindjibarndi’s submissions | [325] |

[326] | |

[333] | |

[334] | |

[342] | |

[349] | |

[390] | |

[391] | |

[391] | |

[399] | |

[403] | |

[409] | |

[420] | |

[422] | |

[450] | |

The evidence of the claim group members about recognition of the Todd respondents as Yindjibarndi | [454] |

[490] | |

Do the Yindjibarndi recognise the Todd respondents as Yindjibarndi? | [504] |

[507] | |

[516] |

RARES J:

1 The Yindjibarndi people inhabited an area of the Pilbara in north-western Western Australia since before British sovereignty or European settlement. They lived on Yindjibarndi country until around the middle of last century. On 9 July 2003, this claimant application was filed. In it the applicant claims, on behalf of the Yindjibarndi, that it is entitled to a determination of native title under s 225 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) over a part of that area (the claimed area).

2 In Moses v Western Australia (2007) 160 FCR 148, the Full Court of this Court made an amended determination of native title in respect of a large area of land to the north (the Moses land) of the claimed area (the 2007 determination). The Full Court amended the original determination that Nicholson J had made earlier on 2 May 2005 (Daniel v State of Western Australia) [2005] FCA 536) (the 2005 determination). His Honour ordered there that Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (YAC) hold the Yindjibarndi’s native title rights and interests in the Moses land in trust for the Yindjibarndi people. Nicholson J had published his substantive reasons for that determination on 3 July 2003 in which he held, relevantly, that the Yindjibarndi held non-exclusive native title rights over the Moses land: Daniel v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 666.

3 Three sets of respondents took an active role in the trial of this proceeding, namely, the first respondent, the State of Western Australia, the second respondent, FMG Pilbara Pty Ltd, Fortescue Metals Group Ltd, and The Pilbara Infrastructure Pty Ltd which are all members of the Fortescue Metals Group (together FMG), and the sixth respondent, Phyllis Harris (née Todd), Lindsay Todd and Margaret Todd (I will refer to the three individuals collectively as “the Todd respondents”). Companies in the Rio Tinto mining group, Hamersley Exploration Pty Ltd and Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd (the Rio parties), as well as Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd and Georgina Hope Rinehart (the Hancock parties), and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation participated in the settling of the agreed issues in dispute before the trial. All of those parties, except Yamatji, adopted substantively the same position on those issues as the State. Yamatji submitted, but did not dispute any of the matters for which the applicant contended.

4 There are six substantial issues that must be decided, namely:

(1) Have the Yindjibarndi proved that they are entitled to a native title right to control access (or exclude others), equivalent to a right of exclusive possession, over so much of the claimed area in which no extinguishing, or partially extinguishing, act has occurred (the exclusive possession issue)?

(2) Were any of miscellaneous licence 47/47 or six exploration licences, E47/54, E47/473, E47/474, E47/475, E47/585 or E47/1349, “a permission or authority … under which the whole or any part of the land and waters in the area is to be used … for a particular purpose” within the meaning of s 47B(1)(b)(ii) so as to extinguish native title rights and interests over the land and waters any such licence covered (the extinguishment issue)?

(3) Have the Yindjibarndi established that one or more members of the claim group occupied, at the time that the claimant application was filed on 9 July 2003, each of the Yandeeyara Reserve 31428 (within the meaning of s 47A(1)(c) of the Native Title Act) and four parcels of unallocated Crown land (UCL) (within the meaning of s 47B(1)(c)) (the occupation issue)?

(4) If yes to issue 1, are the Yindjibarndi precluded from obtaining a determination of native title that they have a right of such exclusive possession because of the 2005 and 2007 determinations that they had only a right of non-exclusive possession over the Moses land (the abuse of process issue)?

(5) Are the Todd respondents members of the Yindjibarndi (the Todd issue)?

(6) To what other native title rights and interests are the Yindjibarndi people entitled and how should the native title holders be described (the relief issue)?

5 The applicant and the State initially agreed that, in the final determination, the description the “Yindjibarndi people” would sufficiently describe the group of persons who hold the common or group rights comprising native title. However, in final submissions the Yindjibarndi sought that their composition be described by reason of their descent from 27 apical ancestors.

The structure of these reasons

6 I will explain the background to this proceeding, including what Nicholson J and the Full Court relevantly decided in making the 2005 and 2007 determinations. I will then deal with each of the six issues in turn. Before doing so, I should indicate that I propose to make findings of fact based on my having seen and heard the witnesses, most of whom gave evidence in September 2015 on country or in Roebourne. The remaining witnesses gave evidence in Perth in September 2016, including the expert anthropologists called by the Yindjibarndi, Dr Kingsley Palmer, and by the Todd respondents, Professor David Trigger. I do not propose, however, to catalogue or summarise every item of evidence since the role of a trial judge is to find the material facts, stating reasons for matters that are contentious.

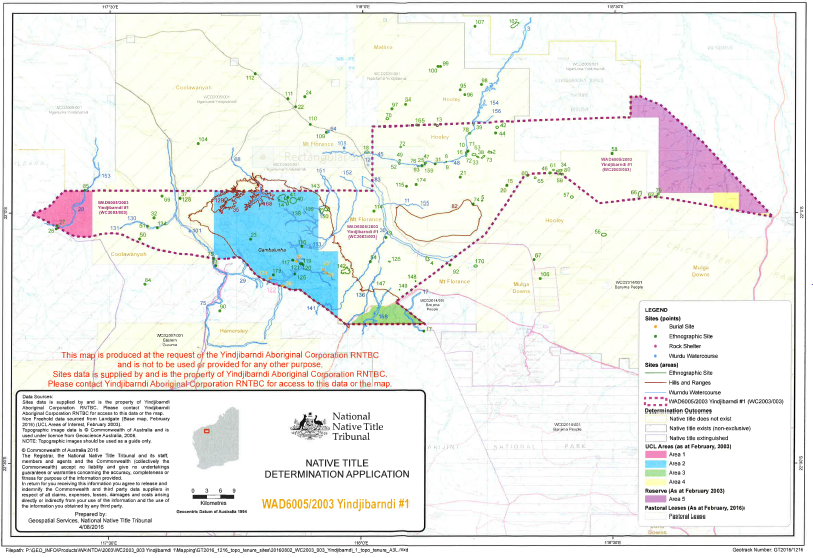

7 The claimed area comprises some areas over which there are current pastoral and mining leases as well as other areas, comprising the Reserve and other unallocated Crown land. The pastoral leases are held by lessees of stations called Coolawanyah (that extends over the north-western boundary of the claimed area into the Moses land), Mount Florance (that also extends, to the east of Coolawanyah, over the mid-part of the northern boundary into the Moses land), Hooley (that is to the east and north-east of Mount Florance) and Mulga Downs (that is to the south-east of Mount Florance and extends over the southern boundary into Banjima country). The claimed area also extends in the north-east over the Mungaroona Range Nature Reserve 31429, the creation of which, the Yindjibarndi accept, extinguished native title in accordance with the decision in Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1.

8 The mining interests are held by FMG, the Hancock parties and the Rio parties. FMG has an operating iron ore mine, known as the Solomon Hub mine, located in UCL 7 within the claimed area. That is near a sacred site and fresh water spring that the Yindjibarndi call Bangkangarra and that FMG has named “Satellite Spring”.

9 The State and (except as to the Reserve and an adjacent UCL) FMG argue that ss 47A(2) and 47B(2) of the Act do not apply to preserve native title rights and interests of the Yindjibarndi over the area covered by the Reserve, the UCLs, or miscellaneous licence and the six exploration licences. There is also a narrow set of issues as to whether native title in various locations in the claimed area has been extinguished by, first, the miscellaneous licence, and, secondly, any or all of the exploration licences.

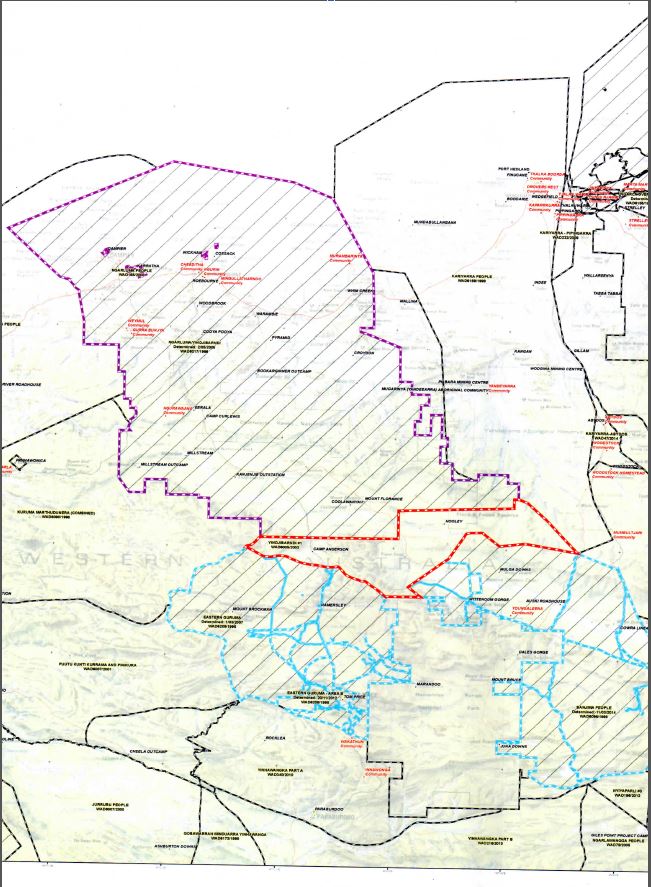

10 Reproduced below is a map that enables an understanding of the physical locations of the claimed area (enclosed in red), the Moses land to its north (enclosed in purple), the land and waters in the Eastern Guruma consent determinations that the Court made in 2007 and 2012 (enclosed in light blue to the south, on the west of the claimed area) (Hughes (on behalf of the Eastern Guruma People) v State of Western Australia [2007] FCA 365; Hughes on behalf of the Guruma People (No 2) v State of Western Australia [2012] FCA 1267), and the land and waters that the Court determined as those of Banjima people in 2014 (enclosed in light blue to the south, on the east of the claimed area) (Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2014] FCA 201 per Barker J; Banjima People v State of Western Australia (2015) 231 FCR 456 per Mansfield, Kenny, Rares, Jagot and Mortimer JJ).

The 2005 and 2007 determinations

11 In the proceeding that resulted in the 2005 determination, Nicholson J heard three separate, overlapping claims, the first was a combined claim made by both the Ngarluma people and the Yindjibarndi people, the second was a claim, that his Honour described as the Yaburara Mardudhunera claim, in respect of land and waters to the north of the Moses land and that has no present relevance (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [99]-[103]), and the third was a claim made by a group that called itself the “Wong-Goo-TT-OO” (WGTO) applicant.

12 Nicholson J decided that the Ngarluma people had non-exclusive native title rights and interests in the northern part of the Moses land, that the Yindjibarndi had non-exclusive native title rights over the southern part (down to the boundary that is contiguous with the claimed area) and that they both shared non-exclusive rights over an area in the middle. In the 2007 determination, the Full Court made some variations to the 2005 determination, which are not material for present purposes.

13 Relevantly, after the appeal, the 2007 determination, that the Full Court made, provided in pars 4 and 7:

4. The native title rights and interests:

(a) do not confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of others; and

(b) are not exercisable otherwise than in accordance with and subject to traditional laws and customs for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes (including social, cultural, religious, spiritual and ceremonial purposes).

…

7. Subject to paragraphs 4 and 8 to 15 inclusive, the Yindjibarndi People have the following non-exclusive native title rights and interests in relation to the [Moses land]:

(a) A right to access (including to enter, to travel over and remain);

(b) A right to engage in ritual and ceremony (including to carry out and participate in initiation practices);

(c) A right to camp and to build shelters (including boughsheds, mias and humpies) and to live temporarily thereon as part of camping or for the purpose of building a shelter;

(d) A right to fish from the waters;

(e) A right to collect and forage for bush medicine;

(f) A right to hunt and forage for and take fauna (including fish, shell fish, crab, oysters, goanna, kangaroo, emu, turkey, echidna, porcupine, witchetty grub and swan but not including dugong or sea turtle);

(g) A right to forage for and take flora (including timber logs, branches, bark and leaves, gum, wax, Aboriginal tobacco, fruit, peas, pods, melons, bush cucumber, seeds, nuts, grasses, potatoes, wild onion and honey);

(h) A right to take black, yellow, white and red ochre;

(i) A right to take water for drinking and domestic use;

(j) A right to cook on the land including light a fire for this purpose;

(k) A right to protect and care for sites and objects of significance in the [Moses land] (including a right to impart traditional knowledge concerning the area, while on the area, and otherwise, to succeeding generations and others so as to perpetuate the benefits of the area and warn against behavior which may result in harm, but not including a right to control access or use of the land by others).

(emphasis added)

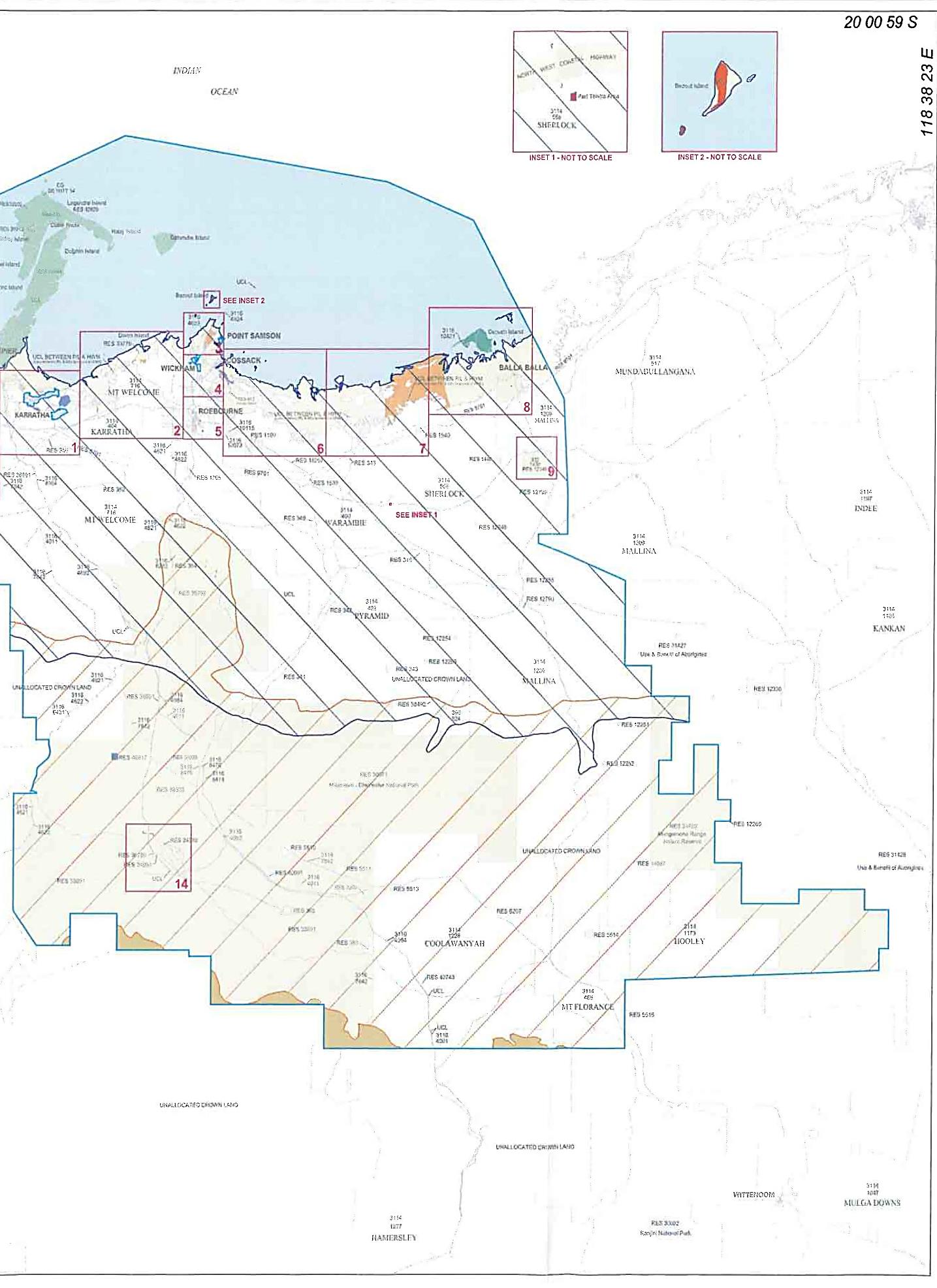

14 The final form of the Moses land determined by the Full Court and delineation of areas of non-exclusive native title rights is, relevantly, in the portion of the map reproduced below, the orange hatching indicating the Yindjibarndi area and the blue hatching, the Ngarluma area, with the shared area shown at the intersection of the hatchings.

15 However, the 2007 determination did not include any rights for the Yindjibarndi to control access to, or use of, land and waters in, or to take or use, for commercial purposes, the resources of, the claimed area.

16 All of the parties that participated in the trial, together with Yamatji, the Rio and Hancock parties, agreed that the Yindjibarndi had the following non-exclusive native title rights in the land and waters in the claimed area in the amended agreed statement of issues filed on 28 August 2015, based on the 2007 determination (the non-contentious rights):

(a) the right to access and move about the area (including to enter, travel over and remain);

(b) the right to hunt in the area (including fish, shell fish, crab, oysters, goanna, kangaroo, emu, turkey, echidna, porcupine, witchetty grub and swan, but not including dugong or sea turtle);

(c) a right to fish in the area;

(d) a right to camp upon and within the area, to build shelters there (including boughsheds, mias and humpies) and to live temporarily thereon as part of camping or for the purpose of building a shelter;

(e) a right to engage in ritual and ceremony (including to carry out and participate in initiation practices);

(f) a right to take black, yellow, white and red ochre; and

(g) a right to take water for drinking and domestic use.

17 The Yindjibarndi claimed several other rights, some of which elaborated the language of some of the non-contentious rights. The respondents who were active at the trial did not accept that any elaboration of the language in which the Yindjibarndi expressed the rights that they claimed in this proceeding, including, critically, a right to control access and or to exclude others, could differ in substance or be more expansive than their rights as settled in pars 4 and 7 of the 2007 determination. The opposition had two foundations, first, the 2007 determination had the legal effect of precluding the Yindjibarndi asserting an entitlement to, or obtaining, any determination that they had any native title rights and interests different to those decided in the contested trial and appeal that had produced the binding and conclusive judicial order being the 2007 determination, and, secondly, if the first foundation failed, the Yindjibarndi had to prove the existence of any additional rights.

18 The first foundation of the opposition is the nub of the abuse of process issue. As a matter of common sense, if the Yindjibarndi are entitled to a determination that they have the right to control access to the claimed area, that will entitle them to a determination that they have a right equivalent to exclusive possession, which in turn will equate to the full rights of ownership of an estate in fee simple: Banjima 231 FCR at 468-473 [27]-[40]; Ward 213 CLR at 64-65 [14].

19 The key finding that, relevantly, Nicholson J made in determining the Yindjibarndi’s claim before him was, in respect of the right to control access, as follows (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [292]):

Such evidence as there is as set out on this matter in Appendix B establishes only that within Yindjibarndi land and Ngarluma land some Yindjibarndi first [sic] applicants claim the right to control access to identified portions of Yindjibarndi land. My impression of the evidence was that while there is evidence of surviving practice to seek permission to enter land considered to be Ngarluma or Yindjibarndi land, when that occurs it is a matter of respect rather than in recognition of a right to control. There is no exercise presently of this aspect of right claimed. (emphasis added)

20 In Appendix B to his Honour’s reasons he said (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [1318], [1319]):

1318 Woodley King identified himself as Ngurrara for Millstream area (T 297). He said that only the right people can speak for Yindjibarndi country (T 288). He said that old people had said that ‘Aboriginal coming from other area’ must seek permission from the local Ngurrara. A non-Yindjibarndi person would need the permission of the Yindjibarndi Jindawurrina ‘mob’ to settle in that area (T 225) or to take part in ceremony under the control of the Yindjibarndi (T 165). Dora Solomon said that if the government wanted to build something at Buminji-na they would need to consult Woodley King. He would speak with the other Yindjibarndi people (T 1040-41). …

1319 Elsie Adams testified to needing Cheedy’s permission to enter and camp on Hooley (T 379). Cheedy Ned testified that he ‘speaks for’ Hooley, and would tell anyone asking about Millstream to talk to Woodley King (T 1231). Any Yindjibarndi person not from Hooley would need his permission to build a house or forage there (T 1233-1234). Pansy Cheedy said if the government wished to develop something on Hooley station they should speak to the person ‘who is closer to … belongs to, the land’. She named her sister Sylvia Cheedy, her father, Cheedy Ned. They in turn should talk to all the other Yindjibarndi people (T 1379-80). (emphasis added)

21 In the time since Nicholson J characterised this evidence of a “practice” of seeking permission as “a matter of respect rather than in recognition of a right to control”, Full Courts have developed the law, commencing with the reasoning of French, Branson and Sundberg JJ in Griffiths v Northern Territory (2007) 165 FCR 391 esp at 428-429 [127].

22 For the moment, in order to set the context in which the exclusive possession and abuse of process issues arise here, it suffices to refer to their Honours’ finding that “if control of access to country flows from spiritual necessity because of the harm that ‘the country’ will inflict upon unauthorised entry, that control can nevertheless support a characterisation of native title rights and interests as exclusive”. They continued (165 FCR at 429 [127]):

The relationship to country is essentially a “spiritual affair”. It is also important to bear in mind that traditional law and custom, so far as it bore upon relationships with persons outside the relevant community at the time of sovereignty, would have been framed by reference to relations with indigenous people. The question of exclusivity depends upon the ability of the appellants effectively to exclude from their country people not of their community. If, according to their traditional law and custom, spiritual sanctions are visited upon unauthorised entry and if they are the gatekeepers for the purpose of preventing such harm and avoiding injury to the country, then they have, in our opinion, what the common law will recognise as an exclusive right of possession, use and occupation. The status of the appellants as gatekeepers was reiterated in the evidence of most of the indigenous witnesses and by the anthropological report which was ultimately accepted by his Honour. We would add that it is not necessary to exclusivity that the appellants require permission for entry onto their country on every occasion that a stranger enters provided that the stranger has been properly introduced to the country by them in the first place. Nor is exclusivity negatived by a general practice of permitting access to properly introduced outsiders. (emphasis added)

23 The evidence before me, as I will discuss below, provided a detailed explanation about why a non-Yindjibarndi or a stranger, called a “manjangu”, needed permission to enter Yindjibarndi land. That explanation was consistent with the concept of spiritual necessity giving rise to a right of exclusive possession.

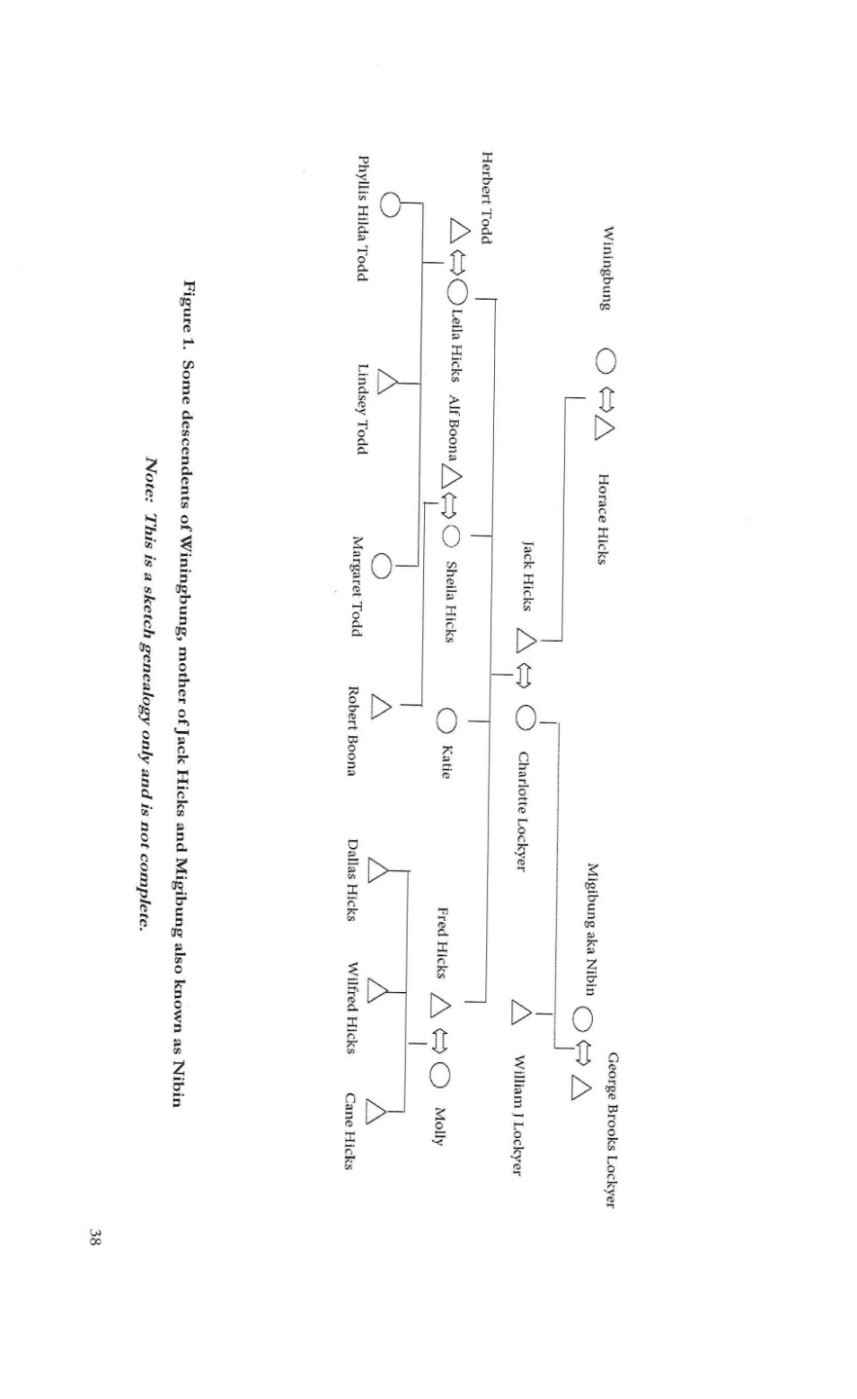

24 The WGTO applicant comprised persons who, Nicholson J found, claimed, relevantly, to have native title in some land and waters that the WGTO applicant asserted they shared with the Yindjibarndi. As a result of an amendment on 6 August 1998, the WGTO applicant consisted of, among others, one of the Todd respondents, Phyllis Harris, and her sister Myline Todd (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [34]). The WTGO applicant asserted that its native title in the Karratha (or Thaluntha) area, which included an archipelago now called “the Burrup”, derived “through cognatic descent from the families of Jack Hicks and his wife Charlotte (Wittingbung)”: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [34], [104]-[107]. The WGTO name was not a traditional name of any group of Aboriginal people, but rather it was a name that the persons comprising the applicant making that claim (as at the final hearing, being Betty Dale, Tim Douglas, Wilfred Hicks, Dallas Hicks, Ernie Ramirez and Cane Hicks) had chosen for the purpose of those proceedings: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 [50]. It is not necessary to describe how the WGTO applicant claimed that they had native title over any Yindjibarndi land and waters or how those rights and interests were shared (cf. Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [78]-[83]).

25 The Todd respondents are related to Wilfred Hicks. Relevantly, Nicholson J found that although they claimed as WGTO, each of Tim Douglas, Wilfred and Dallas Hicks acknowledged themselves as Ngarluma and the Ngarluma accepted that they had that status: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [246]. His Honour found that the “Hicks family have Yindjibarndi ancestry” and that “[i]f, however, they have rights as Yindjibarndi persons, it as [sic] part of the overall connection of the Yindjibarndi with Yindjibarndi country and not through their personal connection”: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [509]. He explained that the Hicks family claimed to be Ngarluma and claimed native title rights through both the genealogical line of their father, who was Yindjibarndi, and their mother, a Ngarluma person whose rights coincided with those of the Douglas family: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [1452].

26 As explained in the evidence before me, persons who have one Yindjibarndi and one Ngarluma or other indigenous parent can elect once for all whether they become part of the people of either parent. Nicholson J found that there was “considerable confusion among the [WGTO] applicants as to the actual structure of the genealogy”. He noted that the Hicks claimants before him claimed native title through their father, Fred Hicks, their mother, Molly Hicks, and their paternal grandmother, Charlotte Hicks (née Lockyer). (For consistency, I have referred to her below, usually, as Charlotte Lockyer.) His Honour said, but did not make a finding, that: “It is asserted that Jack Hicks’ mother was Winningbung, a full blood Aboriginal, and that Charlotte Hicks’ mother was Mikibung” and that both Jack and Charlotte “were said to be Yindjibarndi”. He noted that two witnesses had said that Fred Hicks was Yindjibarndi. His Honour found that Molly Hicks and her mother, Rosie Clifton, were Ngarluma: Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [1453].

27 In the event, Nicholson J dismissed the WGTO claim. He also held that the relevant native title claim group could be described by their language group rather than by criteria such as descent from apical ancestors: Daniel v State of Western Australia (2004) 138 FCR 254 at 267 [53]. The 2005 determination defined, in terms that the Full Court approved on appeal, the Yindjibarndi people as “Aboriginal persons who recognised themselves as, and are recognised by other Yindjibarndi people as, members of the Yindjibarndi language group”.

28 A central question in the Todd issue is whether, on the evidence adduced in these proceedings, one or both of the mothers of Charlotte Lockyer or her husband, Jack Hicks, was Yindjibarndi.

29 On 15 May 2017, after I had reserved my decision on 14 September 2016, YAC filed a revised native title determination application in respect of the 2007 determination under s 61(1) of the Act in proceeding WAD 215 of 2017. There, YAC seeks orders that, in effect, would give it exclusive, rather than non-exclusive, native title over the Moses land.

30 The Native Title Act contains several provisions that are relevant to the consideration of whether the Yindjibarndi’s claim for a determination of native title that includes a right to control access to, or exclude others from, the claimed area and the abuse of process issue based on that claim’s apparent inconsistency with the 2005 and 2007 determinations. Those provisions include:

4 Overview of Act

Recognition and protection of native title

(1) This Act recognises and protects native title. It provides that native title cannot be extinguished contrary to the Act.

…

10 Recognition and protection of native title

Native title is recognised, and protected, in accordance with this Act.

11 Extinguishment of native title

(1) Native title is not able to be extinguished contrary to this Act.

…

13 Approved determinations of native title

Applications to Federal Court

(1) An application may be made to the Federal Court under Part 3:

(a) for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title; or

(b) to revoke or vary an approved determination of native title on the grounds set out in subsection (5).

…

Variation or revocation of determinations

(4) If an approved determination of native title is varied or revoked on the grounds set out in subsection (5) by:

(a) the Federal Court, in determining an application under Part 3; or

(b) a recognised State/Territory body in an order, judgment or other decision;

then:

(c) in the case of a variation – the determination as varied becomes an approved determination of native title in place of the original; and

(d) in the case of a revocation – the determination is no longer an approved determination of native title.

Grounds for variation or revocation

(5) For the purposes of subsection (4), the grounds for variation or revocation of an approved determination of native title are:

(a) that events have taken place since the determination was made that have caused the determination no longer to be correct; or

(b) that the interests of justice require the variation or revocation of the determination.

Review or appeal

(6) If:

(a) a determination of the Federal Court; or

(b) an order, judgment or other decision of a recognised State/Territory body;

is subject to any review or appeal, this section refers to the determination, order, judgment or decision as affected by the review or appeal, when finally determined.

…

61 Native title and compensation applications

Applications that may be made

(1) The following table sets out applications that may be made under this Division to the Federal Court and the persons who may make each of those applications:

….

Applications | ||

Kind of application | Application | Persons who may make application |

Revised native title determination application | Application, as mentioned in subsection 13(1), for revocation or variation of an approved determination of native title, on the grounds set out in subsection 13(5). | (1) The registered native title body corporate; or (2) The Commonwealth Minister; or (3) The State Minister or the Territory Minister, if the determination is sought in relation to an area within the jurisdictional limits of the State or Territory concerned; or (4) The Native Title Registrar. |

…

80 Operation of Part

The provisions of this Part apply in proceedings in relation to applications filed in the Federal Court that relate to native title.

…

82 Federal Court’s way of operating

Rules of evidence

(1) The Federal Court is bound by the rules of evidence, except to the extent that the Court otherwise orders.

…

86 Evidence and findings in other proceedings

(1) Subject to subsection 82(1), the Federal Court may:

(a) receive into evidence the transcript of evidence in any other proceedings before:

(i) the Court; or

(ii) another court; or

(iii) the NNTT; or

(iv) a recognised State/Territory body; or

(v) any other person or body;

and draw any conclusions of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper; and

(b) receive into evidence the transcript of evidence in any proceedings before the assessor and draw any conclusions of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper; and

(c) adopt any recommendation, finding, decision or judgment of any court, person or body of a kind mentioned in any of subparagraphs (a)(i) to (v).

(2) Subject to subsection 82(1), the Federal Court:

(a) must consider whether to receive into evidence the transcript of evidence from a native title application inquiry; and

(b) may draw any conclusions of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper; and

(c) may adopt any recommendation, finding, decision or determination of the NNTT in relation to the inquiry.

(emphasis added)

Division 2 – Key concepts: Native title and acts of various kinds etc.

223 Native title

Common law rights and interests

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Hunting, gathering and fishing covered

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), rights and interests in that subsection includes hunting, gathering, or fishing, rights and interests.

Statutory rights and interests

(3) Subject to subsections (3A) and (4), if native title rights and interests as defined by subsection (1) are, or have been at any time in the past, compulsorily converted into, or replaced by, statutory rights and interests in relation to the same land or waters that are held by or on behalf of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, those statutory rights and interests are also covered by the expression native title or native title rights and interests.

Note: Subsection (3) cannot have any operation resulting from a future act that purports to convert or replace native title rights and interests unless the act is a valid future act.

Subsection (3) does not apply to statutory access rights

(3A) Subsection (3) does not apply to rights and interests conferred by Subdivision Q of Division 3 of Part 2 of this Act (which deals with statutory access rights for native title claimants).

Case not covered by subsection (3)

(4) To avoid any doubt, subsection (3) does not apply to rights and interests created by a reservation or condition (and which are not native title rights and interests):

(a) in a pastoral lease granted before 1 January 1994; or

(b) in legislation made before 1 July 1993, where the reservation or condition applies because of the grant of a pastoral lease before 1 January 1994.

…

225 Determination of native title

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease – whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Note: The determination may deal with the matters in paragraphs (c) and (d) by referring to a particular kind or particular kinds of non-native title interests.

(italic bold emphasis in original)

31 Relevantly, for the purposes of s 82(1) of the Native Title Act, s 91(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) provides:

Exclusion of evidence of judgments and convictions

91(1) Evidence of the decision, or a finding of fact, in an Australian … proceeding is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact that was in issue in that proceeding.

32 Importantly, s 8(1) of the Evidence Act provides that that Act “does not affect the operation of the provisions of any other Act”. And, s 9(1) preserves the operation of an Australian law (including a law of the Commonwealth) so far as that law “relates to a court’s power to dispense with the operation of a rule of evidence or procedure in an interlocutory proceeding”.

Assessment of evidence as to laws and customs

33 The adducing and assessment of the evidence of individuals as to the existence, continuity and observance of traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed must take account of several factors, in addition to those ordinarily applicable in a court’s resolution of issues of fact. First, the indigenous inhabitants of Australia did not have any written record of their history, laws or customs. Accordingly, those matters passed down orally from indigenous generation to generation, and recordings in such contemporaneous written records that European settlers or others made of their interactions with, or observations of, indigenous people. Secondly, indigenous societies did have forms of social organisation, in at least some of which, among other matters, one or more individuals in a community or group had principal responsibility for interpreting or possessing knowledge of the traditional laws and customs. As with any situation involving human recollection of a particular fact (including the content of traditional laws or customs passed down orally over generations within not just the wider society but a family unit), there will be differences in recollections, perhaps compounded by their recitation in discrete groups, so that to expect complete coherence in individual accounts of those matters today would be unrealistic. Indeed, it would be contrary to the lived experience of life. Thirdly, indigenous peoples are very often no longer living on their country or able, continuously, to observe their traditional lives. Rather, European settlement brought about substantial dispossession of most indigenous societies from not only their traditional land and waters, but, in some instances, of the individual members from each other. In those circumstances, the Australian common law must make appropriate allowances for practical adaptation of traditional laws and customs, as well as the potentially differing understandings of individuals within a claim group about their content and contemporaneous acknowledgment or observance.

34 Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ discussed some of these matters in construing the definition of native title in s 223(1) of the Act in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 at 443-445 [43]-[48], with the agreement of McHugh J at 468 [134].

35 The State and FMG argued that the differences in accounts of individual witnesses as to the pre-sovereignty laws and customs and their contemporary acknowledgment and observance should lead to a finding that the Yindjibarndi had failed to prove that they had, or continue to have, a right to control access to the claimed area so as to establish a determination that they have exclusive possession of that part of their traditional land and waters.

36 Ultimately, as with any other litigation involving disputed facts, the party seeking to establish a positive finding in his, her or its favour must satisfy the Court, in accordance with s 140(1) of the Evidence Act, that the case has been proved on the balance of probabilities. In doing so, the Court can take into account the nature of the asserted claim, the subject matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the case alleged (see s 140(2)). Here, it is germane that the Yindjibarndi claim a right of exclusive possession of land and waters that has significant consequences for them, the State, FMG and the public generally. Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ also discussed these matters in Yorta Yorta 214 CLR at 444-447 [45]-[56].

37 In the present case, there is no doubt that the Yindjibarndi comprise a society that continuously have acknowledged laws and observed customs that have united them since before European settlement or British sovereignty. (I will use the expression “sovereignty” to refer to the time at which any native title rights and interests that the common law then recognised (and are now capable of recognition) had to exist or be possessed under the Yindjibarndi’s traditional laws and traditional customs.) That is the necessary conclusion from the findings of Nicholson J that underpinned the Court’s power to make the 2005 and 2007 determinations in favour of the Yindjibarndi. All active parties in this proceeding accept that the Yindjibarndi’s rights and interests that also apply in the claimed area are no less extensive than those comprised in the 2007 determination.

38 The evidence adduced at the trial satisfied me, as I will explain below, that the Yindjibarndi acknowledge laws and observe customs that have united, and continue to unite, them as a society continuously since before sovereignty.

39 An important instance of that acknowledgment and observance is that the Yindjibarndi observe the defining ritual of making uninitiated (mostly young) males pass formally into manhood by “going through the [Birdarra] law” in an annual ceremony. The secret men’s evidence given at Bangkangarra during the hearing comprised a portion of that ceremony. That included a performance of dancing and singing portions of the Bundut (or Burndud) in a language that is no longer spoken in the Pilbara. The Bundut is not a secret men’s song, unlike other evidence given on that occasion. The participants understood and explained in the confidential hearing the spiritual and other significance of the dances and songs that they performed. The use of now no longer spoken language in such a ceremony can be compared to the use in many nations, including Australia, in the Roman Catholic church of Latin rituals until the mid-20th century when services were permitted in the domestic language.

(1) THE EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION ISSUE

40 The applicant, the State, FMG, the Rio parties, the Hancock parties and the Todd respondents filed statements of their contentions. In those, FMG, the Rio parties and the Hancock parties substantively adopted the position of the State, with the exception of the abuse of process issue, that only the State and FMG pursued. The statements of contention and the agreed statement of issues, read together, identified the following admitted facts, namely that:

the Yindjibarndi constitute a society that has continued to exist, since before the assertion of sovereignty in 1829, as a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of a body of traditional laws and customs under which they possess native title rights and interests;

the Yindjibarndi’s native title rights and interests are held by them as communal rights and interests and it is unnecessary to establish connection on a subgroup or estate basis;

the Yindjibarndi have a connection with the claimed area within the meaning of s 223(1)(b) of the Act;

members of the Yindjibarndi language group occupied and used the claimed area, as of right, under a body of laws that they acknowledged and customs that they observed, and they possessed rights and interests in relation to, and had a connection with, the claimed area;

the Yindjibarndi have continued, substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty, to acknowledge and observe a body of traditional laws and customs under which they possess, as a group, rights and interests in relation to their traditional land and waters, including the claimed area and the Moses land (collectively Yindjibarndi country), and by those laws and customs have a connection with Yindjibarndi country;

rights and interests in relation to Yindjibarndi country are gained primarily by cognatic descent, under the traditional laws and customs as presently acknowledged and observed by the Yindjibarndi;

the Yindjibarndi consider that Yindjibarndi country, including the claimed area, is redolent with spirituality, commemorated by senior male members through mytho-ritual traditions, and, in particular, their unique Birdarra law;

the right to rehearse the spirituality of Yindjibarndi country (including, of course, the claimed area) and manage its geographic and physical manifestations rests primarily with those Yindjibarndi qualified to do so;

the exercise of rights to use Yindjibarndi country requires knowledge of the country and its resources;

under traditional laws and customs as presently acknowledged and observed, a person who does not belong to Yindjibarndi country and cannot assert rights to it, is identified by use of the word “manjangu”;

the Yindjibarndi language is a common point of identity reference for those Yindjibarndi individuals who claim native title rights and interests in the claimed area;

persons identifying as Yindjibarndi, in general (I have used the qualification “in general” because the State and FMG do not admit that each and every Yindjibarndi person acknowledges and observes the Birdarra), acknowledge and observe the mytho-ritual religious observance called Birdarra;

the observance of the Birdarra includes singing the Bundut, which is a series of songs and accompanying exegesis that is performed in connection with male rituals;

the Yindjibarndi understand that, first, the Bundut relates directly to Yindjibarndi country, including the claimed area, by associating the various subjects of the songs with named places in the countryside, and secondly, the singing of those songs unites a singer with the part of the country that is the subject of the songs in such a way that the country can “feel” the singer, and the singer can “feel” the country and keep it alive;

much of the information about the Birdarra and associated rituals is esoteric and its dissemination is restricted to ritually qualified men. Generally, women do not discuss any matters relating to the Birdarra;

the Yindjibarndi continue to practice the Birdarra law (that they sometimes call “the Law” or “initiation”) and commonly do so at the “Woodbrook Law Ground”, near Roebourne, where many Yindjibarndi now reside.

41 The statements of each active party’s contentions identified the issues in dispute and formed the basis on which the parties prepared their evidence for the trial. On the second day of the hearing on country I rejected the attempts of the State and FMG to cross-examine witnesses, that the applicant called, on matters that those two parties had admitted in their contentions. The disallowed line of questioning sought to challenge, in particular, the admitted fact that it was unnecessary for the Yindjibarndi to establish connection on a subgroup or estate basis. That was because all active parties had admitted that, first, the Yindjibarndi held their native title rights and interests communally and, secondly, “it is unnecessary to establish connection on a subgroup or estate basis”: TJ (on behalf of the Yindjibarndi People) v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2015] FCA 1358. Nonetheless, as will appear below, the State and FMG structured some of their arguments around evidentiary issues relating to the existence or exercise of some rights or interests based on subgroups or estates. The applicant’s witnesses’ evidence in chief had been prepared on the basis of the admission that it was unnecessary to establish connection on a subgroup or estate basis.

42 There is no dispute that, even though most Yindjibarndi now live outside the claimed area, Nicholson J’s finding, that they had “remarkably maintained a strong sense of connection to their lands” that remained unbroken, also applied in respect of the claimed area (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [421]-[422]). I am in no doubt, from the whole of the evidence before me, that this deep sense of connection continues to be true of the Yindjibarndi’s relationship to their country, of which the claimed area forms part. While this finding addresses, in part, s 223(1)(b) of the Native Title Act, that is not, however, sufficient of itself to establish the existence or formal expression of any native title rights and interests that the Yindjibarndi may have in the claimed area beyond the admitted existence of the non-exclusive rights in the 2007 determination. In Ward 213 CLR at 64-65 [14], Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said:

As is now well recognised, the connection which Aboriginal peoples have with “country” is essentially spiritual. In Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd [(1971) 17 FLR 141 at 167], Blackburn J said that: “the fundamental truth about the aboriginals’ relationship to the land is that whatever else it is, it is a religious relationship … There is an unquestioned scheme of things in which the spirit ancestors, the people of the clan, particular land and everything that exists on and in it, are organic parts of one indissoluble whole”. It is a relationship which sometimes is spoken of as having to care for, and being able to “speak for”, country. “Speaking for” country is bound up with the idea that, at least in some circumstances, others should ask for permission to enter upon country or use it or enjoy its resources, but to focus only on the requirement that others seek permission for some activities would oversimplify the nature of the connection that the phrase seeks to capture. The difficulty of expressing a relationship between a community or group of Aboriginal people and the land in terms of rights and interests is evident. Yet that is required by the NTA. The spiritual or religious is translated into the legal. This requires the fragmentation of an integrated view of the ordering of affairs into rights and interests which are considered apart from the duties and obligations which go with them. The difficulties are not reduced by the inevitable tendency to think of rights and interests in relation to the land only in terms familiar to the common lawyer. Nor are they reduced by the requirement of the NTA, now found in par (e) of s 225, for a determination by the Federal Court to state, with respect to land or waters in the determination area not covered by a “non-exclusive agricultural lease” or a “non-exclusive pastoral lease”, whether the native title rights and interests “confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others”. (emphasis added)

43 Their Honours held that the question whether s 223(1)(a) is satisfied, in any given case, is one of fact requiring the identification of, first, the asserted traditional laws and customs and, secondly, the rights and interests in relation to land and waters that are possessed under those laws and customs. They recognised that answering that question “may well depend upon the same evidence as is used to establish connection of the relevant peoples with the land and waters”, since the requisite connection under s 223(1)(b) must be “by those laws and customs” (Ward 213 CLR at 66 [18]). They emphasised that s 223(1)(a) and (b) provide that the traditional laws and customs, and not the common law, are the source of any native title rights and interests (213 CLR at 66-67 [19]-[21]).

44 Recognition of a law or custom of one indigenous people by another indigenous people in relation to seeking permission to enter, or conduct activities (such as hunting) on, land or waters, and the spiritual or other purpose or consequence of seeking or failing to have that permission, can demonstrate the normative effect of the law or custom: Banjima 231 FCR at 473 [40] per Mansfield, Kenny, Rares, Jagot and Mortimer JJ.

45 Nicholson J gave detailed consideration to the historical background that related to and affected the three separate claims and evidence before him. He made the following findings in Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [192]-[201] that were not in dispute and that I adopt, together with his Honour’s findings at [152]-[190], under s 86(1)(c) of the Native Title Act:

192 The Ngurawaana Group Inc. which succeeded in having an alcohol rehabilitation community set up at Daniels Well, formerly part of the Millstream Pastoral lease was established in 1983 by Yindjibarndi elders, led by Woodley King. In 1982 that lease had been purchased by the State and led to the creation of the Millstream – Chichester National Park in 1984.

193 On 28 September 1983 John Peter Pat died of closed head injuries in the juvenile cell of the police station lock up in Roebourne, aged almost seventeen. He had been assaulted to varying degrees by arresting police officers who were later acquitted of his manslaughter. He became for Aboriginal people nationwide a symbol of injustice and oppression. International media attention focussed both on his death and the conditions in Roebourne. (These statements come from the Report of the Inquiry into the Death of John Peter Pat by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, 1991, p 1-2). The Pat family are members of the first applicants’ claim group and identify as Yindjibarndi. The Commissioner found that Roebourne’s Aboriginal people, including some Ngarluma people, had redefined their places of belonging in terms of the stations so that station life to some extent allowed the continuation of traditional social relations and a certain maintenance of autonomy (p 280). He said the impact of the mining boom had changed Roebourne from the administrative and commercial centre for the region into a neglected backwater (at p 283).

194 The Harding Dam was opened in 1985. Aboriginal people active against it brought about the establishment of the Ngurin Mirlimirli Maya Resource Centre (‘the Ngurin Centre’) in Roebourne in 1985, becoming the focus for politically active Aborigines. Its membership was drawn from Roebourne, Woolshed and Ngurawaana. Yindjibarndi was spoken at the meetings. In the same year an Aboriginal Medical Service (‘Mawarnkarra’) was established in Roebourne.

195 Roebourne therefore became the major centre for the claim areas’ Aboriginal population, leading to social, political and cultural change there. Dr Green wrote of these changes:

‘The move into Roebourne contributed to the emergence of politically influential incorporated Aboriginal organisations which have directed community action into areas of social and cultural concerns, such as alcohol rehabilitation, land acquisition and the preservation of sites of significance. The acquisition of pastoral leases, such as the Mt Welcome station, and concerns over particular interests in Bumingina (the former Tablelands police station), the Millstream aquifer and the Harding River (Dam) are among the issues that continue to engage Aboriginal people located in Roebourne.’ (Green).

196 In 1989 the State Equal Opportunity Commission examined local government services in Western Australia. It found significant inequalities in the distribution of funds and services among, on the one hand, Karratha, Dampier, Hearson Village and Wickham and, on the other, Roebourne (Pat Report, p 293).

197 The historical record shows Aboriginal populations in each of the claim areas numbering in the vicinity of 300 – 400 throughout the first half of the 20th Century. Roebourne’s Aboriginal population increased from 476 in 1965 to 1200 in 1985 and included many more children.

198 The historical record also shows that, with the advent of station life and of enclosures, stocking and a different land use, there were consequent impacts on plant and animal life which significantly reduced the opportunity for Aboriginal people to live on their land. The establishment of government ration stations, issuing food and blankets, in the early 20th Century both nurtured indigent Aborigines and contributed to their isolation from the country. Police action up to the 1940s in returning Aborigines to stations where they had work had the same effect.

IMPACTS OF THE LAW

199 Likewise the historical record discloses the impact of the law on Aborigines in Western Australia and hence in the claim areas. The content of that law in the 19th Century was influenced by the policies of the Imperial Government to Aborigines as reflected in its ‘Instructions as to the office of Governor’ to the first Governor Stirling in 1831 and his earlier Proclamation in 1829. These sought to equate Aborigines and Europeans before the law. However:

‘Practical objections to this ideal almost immediately obtruded and in the following century the goal almost receded from view in the usage of legislation which was enacted to deal with the Aborigines. The keynote of policy became their protection from themselves, by shielding them from responsibility and imposing rigid personal controls.’

(Report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Affairs by His Honour Judge Furnell, July 1974, p 20)

200 By mid-century legislation had been introduced to protect Aborigines in relation to matters such as pearl fishing and their access to land upon the grant of a pastoral lease (34 Vic. No 14 of 1871 and Land Act Regulations 1887 respectively). The Aborigines Protection Act 1886 (WA) established the Aborigines Protection Board. On the Constitution Act 1890 coming into force it withheld control of Aborigines from the self-governing legislature, although seven years later it was vested in the Western Australian Government (61 Vic, No 5 of 1898). That control was strongly asserted by the Aborigines Act 1905 (WA) and the Aborigines Act Amendment Act 1936 (WA) authorising removal of children and providing for other controls over Aboriginal people. Writing in 1941, Hasluck described the 1936 Act as having given the Aboriginal ‘a legal status that was more in common with that of a born idiot than any other class of British subject’. (Hasluck, pp 160-161). In 1974 the Royal Commission found of the same Act (at 23) that it:

‘… did more than any other to emphasise the second-class citizenship status accorded to Aborigines and it imposed restrictions and controls upon them which would not have been tolerated by any other section of the community, even though many of these provisions were intended to be protective in nature. The effect of them was to make the Aborigines … resentful of authority, particularly the police and the Department itself, and either belligerently anti-social or dejectedly apathetic.’

The historical records show such removals continuing until as late as 1946. Marriages of non-Aboriginals to female Aborigines required permission. The Natives (Citizenship Rights) Act 1944 (WA) allowed Aborigines to claim citizenship but on the basis they gave up tribal associations. The State legal regime had therefore moved from a form of benevolent protection to one which had discouragements to maintenance of Aboriginal connection with the land through traditional laws acknowledged and customs observed. (See E Russell, ‘A History of the Law in Western Australia’, University of Western Australia Press, p 313–325).

201 The establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 also brought with it a legal regime with distinctive impact on Aborigines. From 1901 until 1967 the federal Constitution excluded ‘Aboriginal natives’ from population counts. Pensions or allowances were not payable to Aborigines with more than one-half of Aboriginal blood. Voting eligibility for Aborigines did not commence federally until 1962 and in the State until 1971. (emphasis added)

The exclusive possession issue – the facts

46 Michael Woodley is a senior lawman, called a tharngungarli or tharngu in Yindjibarndi, because he is one of the most knowledgeable in the Birdarra law. He is the grandson of Woodley King, a respected Yindjibarndi elder as Nicholson J found (Daniel [2003] FCA 666 at [192] in the quotation above and [1442]), and is now a Yindjibarndi elder in his own right. Michael Woodley gave detailed and reliable evidence of Yindjibarndi law and custom in both their historical and contemporary forms. He spent more than 20 years learning about Yindjibarndi culture from his grandfather, Woodley King, with whom he lived on the Moses land at Ngurrawaana, after finishing primary school in Roebourne. Michael Woodley’s grandfather was principally responsible for his education after primary school together with other male and female Yindjibarndis.

47 In June 2000, Michael Woodley and his wife Lorraine Coppin established Juluwarlu to collect, record, document, publish and broadcast the language, history and culture of the Yindjibarndi people.

48 Michael Woodley learnt from “the old Yindjibarndi Law Bosses” and old Yindjibarndi women the ceremonies, songs and stories for Yindjibarndi, which sites and areas in Yindjibarndi country had significance because of cultural beliefs, the galharra relationship rules, the ancient language used in law ceremonies and the dreaming meditation, called Buyawarri, that Yindjibarndi “use to receive the knowledge from our country”.

49 Galharra is a system of rules that is the most important part of the Birdarra law. It is used to divide all things Yindjibarndi, animate and inanimate, into four groups: banaga, burungu, garimarra and balyirri. Thus, not only do people have a galharra, sometimes referred to in the evidence as “a skin” or “section”, but so do all things, including animals, plants and places where water is, as well as the sun, moon and stars, fire, wind and water.

50 Galharra dictates how one person in a group must behave in relation to all people and things in both that group and each of the other three. That is because, in Michael Woodley’s words:

Galharra is the centre of everything; it tells each of us what we must do and what we must not do in our relationships with each other and in our relationships with our country and its resources.

51 Galharra contains rules as to whom a Yindjibarndi can marry and whom he or she must avoid, for whom they must care or by whom they must be cared for, their roles and responsibilities at ceremonies and to, or by whom, deference is due. When a child is born, he or she will have a galharra group that cannot be the same as that of either parent. In turn, the child will have to marry a spouse with another galharra that is ascertained by following the system of rules. A fundamental aspect of galharra is the system of rules, called nyinyadt, for sharing resources in Yindjibarndi country. Michael Woodley said that nyinyadt “is the social fabric of Yindjibarndi … it is a social contract under which every Yindjibarndi person is entitled to share in the bounty of Yindjibarndi country and prosper”. If a Yindjibarndi does not comply with, or will not acknowledge, nyinyadt, “they become cursed by the country … and it is a death warrant. A slow and painful death follows to demonstrate what happens to greedy and selfish individuals who challenge or go against nyinyadt”.

52 Michael Woodley explained that the Birdarra law is a system of cultural beliefs and values that includes:

Yindjibarndi country is “a sacred domain inhabited by the spirits of our old people and by Marrga … powerful creative spirit beings who gave form to everything that is Yindjibarndi in the … creation times …”;

Minkala (the Yindjibarndi name for God) gave the Birdarra law to the Marrga, whom Minkala sent to Earth to create the Pilbara, as it is today, and to bring law to the Ngaardangarli (being the Pilbara Aborigines);

after a time, the Marrga foresaw their own passing and they gathered together all of the Ngaardangarli at Gumunha (also known as Gregory’s Gorge), who then all spoke a common language (now preserved in the songs in the Bundut), were of one group and had no responsibility for any particular law or part of the country. At this gathering the Marrga “divided the Ngaarda into different groups and put each group into a domain”. The Marrga gave each group its language and law, commanded the respective group to speak for their domain in their particular language and to look after their domain in accordance with the given law for it;

Yindjibarndi country is the domain that the Marrga created for the Yindjibarndi people. That domain includes all the Moses land and the claimed area;

neighbouring Ngaardangarli groups refer to the Birdarra law and the Bundut (which are exclusive to the Yindjibarndi) as “thurdunha” (the big sister, or “sitting on top”, of all other law). In contrast, Yindjibarndi do not use that expression, but instead refer to their respective neighbour’s law as the “top” law. Michael Woodley explained that in this way, “we each show respect for each other’s law”;

the Marrga (being creation spirits) still live in Yindjibarndi country “along with the spirits of our old people; and … they watch us always to make sure we look after our country [in] the proper way, in accordance with the Birdarra Law”. There are pictures of the Marrga throughout Yindjibarndi country carved in rocks and painted in caves and rock shelters to serve as reminders that the Marrga are still there and watching to make sure the Yindjibarndi look after their country;

under the Birdarra law:

if we look after our country [in] the proper way, our country must look after us and provide for us; this is the promise of Minkala (God), which was told to us by the Marrga. However, if we break the Birdarra Law, or allow others to break it, we suffer; our people get sick or die, or the country dries up and we can’t get what we need to go on living. (emphasis added)

53 Michael Woodley explained the spiritual connection that the Yindjibarndi have with their country in the following way:

Yindjibarndi people, Yindjibarndi language and Yindjibarndi country (and all that is within, from both past and present) are not different things, but related parts of one thing called “Yindjibarndi”, which came into existence in the Ngurranyujunggamu. I do not feel or see myself as something that is separate and different from Yindjibarndi country because my spirit comes from my country and is always connected to it. It’s the same for all Yindjibarndi. This is why, if Yindjibarndi country is hurt because the Birdarra Law is not followed, Yindjibarndi people suffer. The Yindjibarndi people were commanded by the Marrga to look after Yindjibarndi country, in accordance with the Birdarra Law, and we are held accountable for everything anyone does in Yindjibarndi country. (emphasis added)

54 I am satisfied, having considered all of the evidence, that this explanation of spiritual connection reflects both important traditional laws, that the Yindjibarndi acknowledged, and traditional customs, that they observed, at the time of sovereignty and continue to acknowledge and observe today. The explanation neatly captures the essence of the relationship of the Yindjibarndi to their country and their spiritual obligation, embedded in their traditional laws and customs, to protect that country, including from the presence and activities on it of strangers (or manjangu) unless the stranger(s) first obtain(s) permission from Yindjibarndi people.

55 In addition, I am satisfied that, if a stranger were free to enter Yindjibarndi country without permission, under those Yindjibarndi normative laws and customs that have continuously applied over the same time period, he or she could “hurt” the country by violating the Birdarra law, even if unintentionally; for example, by entering a sacred or restricted place, or taking something, such as a resource or animal, from the country. And, those laws and customs thus require the Yindjibarndi to protect their country from a manjangu gaining access to it or its living or inanimate resources without permission of a Yindjibarndi elder.

56 Moreover, I am satisfied by all of the evidence that the Yindjibarndi have continuously (since before sovereignty) acknowledged traditional laws and observed traditional customs relating to the presence, role and power of the spirits of the Marrga and “old people” in and over Yindjibarndi country.

57 Michael Woodley explained that Yindjibarndi country is the ngurra or home of the Yindjibarndi people. There are 13 areas, also called ngurras, into which Yindjibarndi country is divided, and each ngurra is itself divided by a wundu (being a watercourse) that gives the ngurra its name. Each ngurra is divided into four parts, one for each of the galharra groups, the banaga and burungu on one side of the watercourse and the garimarra and balyirri on the other. The divisions also have importance for ceremonial activities.

58 Ngurra is the home of the Ngurrarangarli, being the human beings from the ngurra. Under the Birdarra law, the Yindjibarndi believe that the spirits of the Ngurrarangarli come from, belong to, and ultimately return after an individual’s death to, their ngurra. Michael Woodley said that even when Yindjibarndi people are separated from their ngurra through their daily activities, “our spirits remain connected to our ngurra”. He said that each ngurra had its own spiritual energy that was very powerful. He also said that each ngurra held the spirits of ancestors who had belonged to it and those spirits watched over the ngurrara (meaning country owner) “to make sure we are following our law. If we do, they look after us and help us; if we don’t, they can grab us and hurt us”.

59 Each ngurra has its own sacred site or sites, called a thalu, where the Yindjibarndi perform cultural ceremonies. For example, the Yindjibarndi believe that Manggurla thalu, which is close to Bangkangarra, is a fertility site accessible to both men and women for increasing the number of children. They perform a ritual there for that purpose. Michael Woodley’s grandfathers taught him how to perform the ritual, which he has since done on about two occasions. Moreover, whenever he visits the locale, he either goes to that thalu directly, or points it, and its significance, out to the other Yindjibarndi men and women whom he is with to teach them. In addition, when taking young Yindjibarndi men to learn secret men’s business, such as occurs at Bangkangarra, the older men continue to show the younger ones sites, like thalus, and explain their importance.

60 Other thalus are used for collection of ochre (yarna) and sacred stones (gandi), or for healing (mowan), or propagation of honey (marliya). Indeed, as Michael Woodley said “[t]here are thalu for everything in Yindjibarndi country”. He said that it was the duty of the senior Yindjibarndi lawmen, including himself, to visit different parts of Yindjibarndi country regularly to perform thalu ceremonies to “let the country know we are still here, that we haven’t forgotten our country, and that it should not forget us”. Michael Woodley’s grandfathers also taught him the correct ritual to perform for the relevant site on these visits. He has visited, among other places, the claim area every year to perform these rituals since he was taught them.

61 A lawman must be the correct galharra to work or perform rituals at any particular thalu and he must be painted up with local ochre. He must ask the Marrga at the site for permission to break a branch or leaves off a tree to use in brushing the thalu from side to side while calling out to the country in Yindjibarndi language. The Yindjibarndi believe that by working the various thalus the senior lawmen protect and control all creatures in Yindjibarndi country, such as fish in the rivers and birds, as well as bush foods and medicines. Michael Woodley collects ochre regularly from a number of sites in the claim area.

62 The Mount Florance and Coolawanyah pastoral leases straddle part of the boundary between the Moses land and the claimed area. The leases include, principally (around their centre), a flat plain (Yawarnganha) that is within the claimed area, and lies between the Hamersley Range (Gambulanha) to the south and the Chichester Range (Birdarrdamra) to the north.

63 The past and current pastoral lessees of that area have respected the Yindjibarndi’s continuing practice of their traditional laws and customs on the pastoral lessees’ land and waters. The Yindjibarndi make arrangements with the pastoral lessees to ensure that their visits or activities do not clash with pastoral activities. When on the pastoral lease areas, the Yindjibarndi in the past have, and now continue to, camp, hunt, fish, collect bush tucker, bush medicines and perform religious ceremonies.

64 Michael Woodley explained that Yawarnganha has particular importance for the Yindjibarndi. That is because it is the only area in Yindjibarndi country where, first, sacred trees called wirndamarra grow and, secondly, they can hunt emu for their yulbirriri thurru ritual. He said that the wood from wirndamarra is used to make certain sacred objects that identify Yindjibarndi people with their law and country “so [that] no other group can steal our lands”. The yulbirriri thurru ritual is performed by grandfathers with their newly initiated grandsons. The grandson must hunt for an emu on the Yawarnganha plain and once he has one, he must take it to a yulbirriri thurru area, chosen by his grandfather, that surrounds the mouth of a watercourse that flows out of the Hamersley Range (Gambulanha) into the Yawarnganha, near the base of the escarpment. The Yindjibarndi name for the escarpment, Gumbayirranha, means “a face-to-face reflection of each other”. The ritual requires the young man to show his face for the first time to the face of Gambulanha.

65 The Yindjibarndi believe that when they look face to face at Gambulanha they reflect one another or, in Michael Woodley’s words:

the Range and its knowledge is the Yindjibarndi and his knowledge – it’s like looking into a mirror and seeing a true reflection of yourself and all the fine features of your face that you must care for and protect: a head that holds the key to the all Yindjibarndi knowledge; a mouth that speaks and sings to you; an eye looking over and seeing everything; an ear that hears everything that the birds, plants, animals and the ngurrara are saying. And a brain that controls all Yindjibarndi movements on country and responds by activating all sorts of unanswerable events that Yindjibarndi put down to natural chain of events. A similar experience can happen at a site called Gambajuju [which is near, but to the north of, Bangkangarra within the claim area].

The yulbirirri thurru ritual is carried out where the waters flow out of Gambulanha for the young man’s safety, it allows him to be seen by the spirits of our country, so that the religious knowledge can find him, without the risk of being grabbed by them. To this end the grandfather teaches his grandson how to cook the emu on hot stones and then covers his body with the emu oil. The yulbirrirri thurru ritual makes the young man and country one, so that he can receive the knowledge and be accepted by all the elements of the country as a birirri (man).

The Yawarnganha plain is named after the hot stones that are used to cook the emu; and these stones can be found only in the river along the Mangudunha – this is a hunting and gathering ground and is like a cause-way located between the Range and the Fortescue River. (emphasis added)

66 Angus Mack explained that there were places in Yindjibarndi country, including numerous ones in the claimed area, that were dangerous. For example, he said that Jilinjilin, near Mt Parsons (in the vicinity of the northern boundary of the claimed area toward its centre was dangerous because there were spirits there, although he went on to say “there are spirits everywhere. There’s no particular place that has no spirits”. If a manjangu entered Yindjibarndi country without permission, he said that the spirits “can come there and … do bad things with them”. Angus Mack said that the consequence could be serious harm and that the spirits “could cripple you” and “hit your body” from the inside:

because what they do, spirits, they take your soul. They lock it up in the country. That’s what I meaning by you will deteriorate somewhere else, at town, or … you can go from here good but … if manjangu come into Yindjibarndi country, and they go, the spirit will grab their spirit - will grab the spirit and … the person wouldn’t know that. You will go back to … where you come from … you will slowly deteriorate and pass away. That’s how it does that spiritually. And … the buyawarri, the dream, well a lot of people … experienced it. (emphasis added)

67 He said that he learnt this when he “went through the law because you need to know that … to be … a lawman … to look after those sites”. Angus Mack also said that if a manjangu first sought permission, then the Yindjibarndi would perform a ceremony to ascertain the person’s intentions and whether he or she were genuine and did not wish to harm or cause a threat to them or their country.

68 Angus Mack said that if a manjangu came onto Yindjibarndi country without permission and took, for example, a kangaroo, then he or she would be punished by one or both of the spirits or a lawman (who may have been informed of the visit or activity by the spirits). He said that the lawman gets his power from the spirits who know the person who entered or acted without permission. He gave confidential evidence, which I accept, about his knowledge of an occasion when a senior lawman had punished a manjangu who came onto Yindjibarndi country without permission. I found that evidence, which was not challenged, compelling as to the significance to Yindjibarndi of their spiritual beliefs.

69 Angus Mack also explained that neighbouring Pilbara indigenous peoples, such as the Banjima, Guruma, Eastern Guruma and Nyiyiparli, observe (and traditionally observed in the past) similar traditional laws and customs in respect of when, for example, a Yindjibarndi wishes to access their country and when any member of those other peoples wants to access Yindjibarndi country. That was consistent with the observations of Prof Radcliffe-Brown and Dr Palmer to which I refer at [90]-[95] below. I infer that this observance has existed since before sovereignty.

70 Angus Mack said that, if a person failed to seek permission in the correct manner, “back in the day you would get speared or punished by tribal punishment”. He said:

Today we still carry the Law, we don’t go helping ourselves to other people’s country because it’s the Law that was handed down by the Marrga to us Yindjibarndi people. We don’t go in other people’s country because there are rules that we don’t go into other people’s country. You feel the rules in your wirrart (soul), it changes and tells you, “I’m in somebody else’s ngurra, somebody else’s country.” That’s how you feel inside, like “I’m doing the wrong thing here,” and your own wirrart will tell you, “I’m breaking the Law here”. (emphasis added)