FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 5) [2017] FCA 363

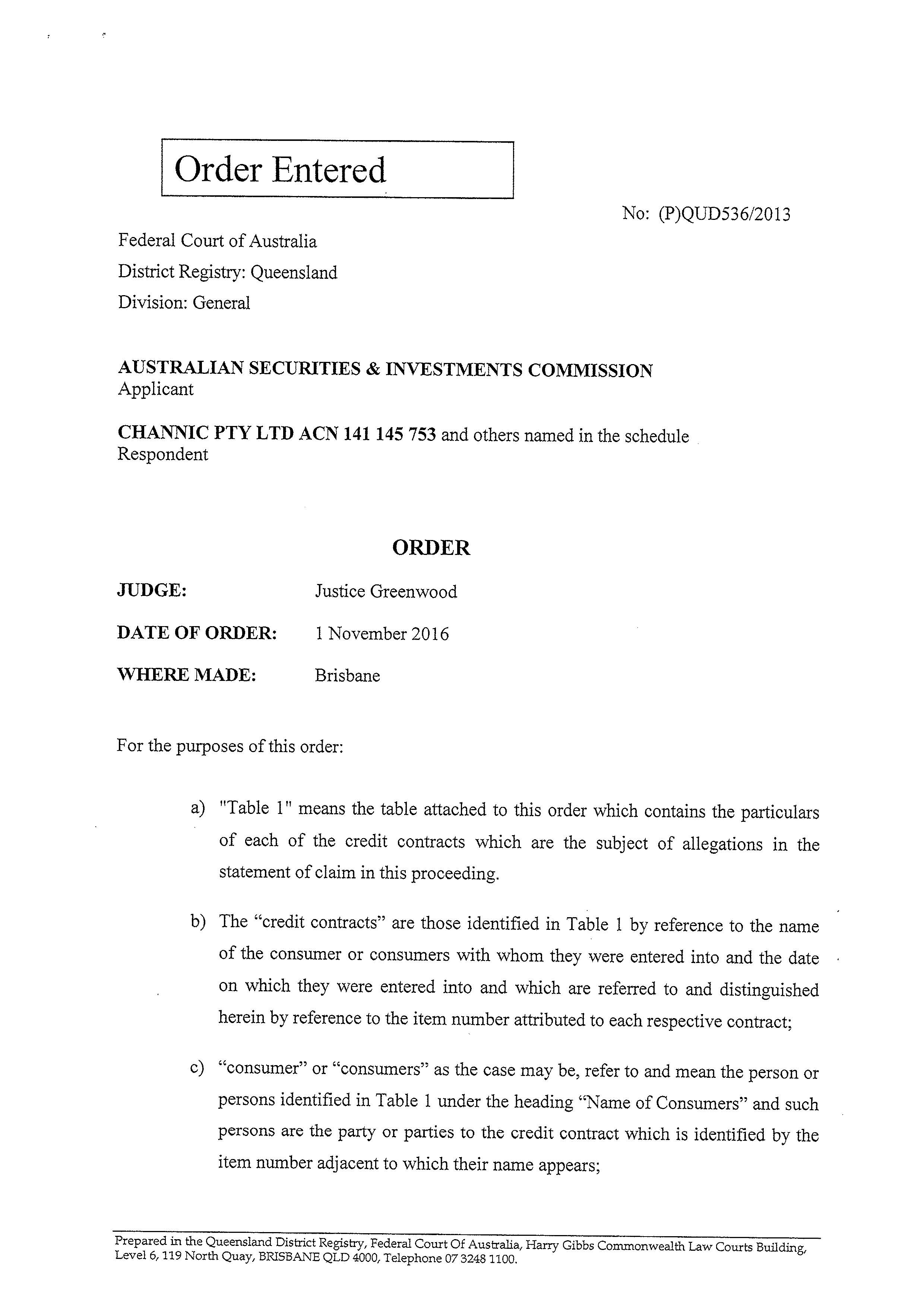

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | CHANNIC PTY LTD (ACN 141 145 753) (and others named in the Schedule) First Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT on 23 March 2017 the Court ordered Channic Pty Ltd to repay, by Orders 1 and 2, particular sums of money to particular consumers the subject of the principal proceedings. The orders of 23 March 2017 are to be read together with the orders made today.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

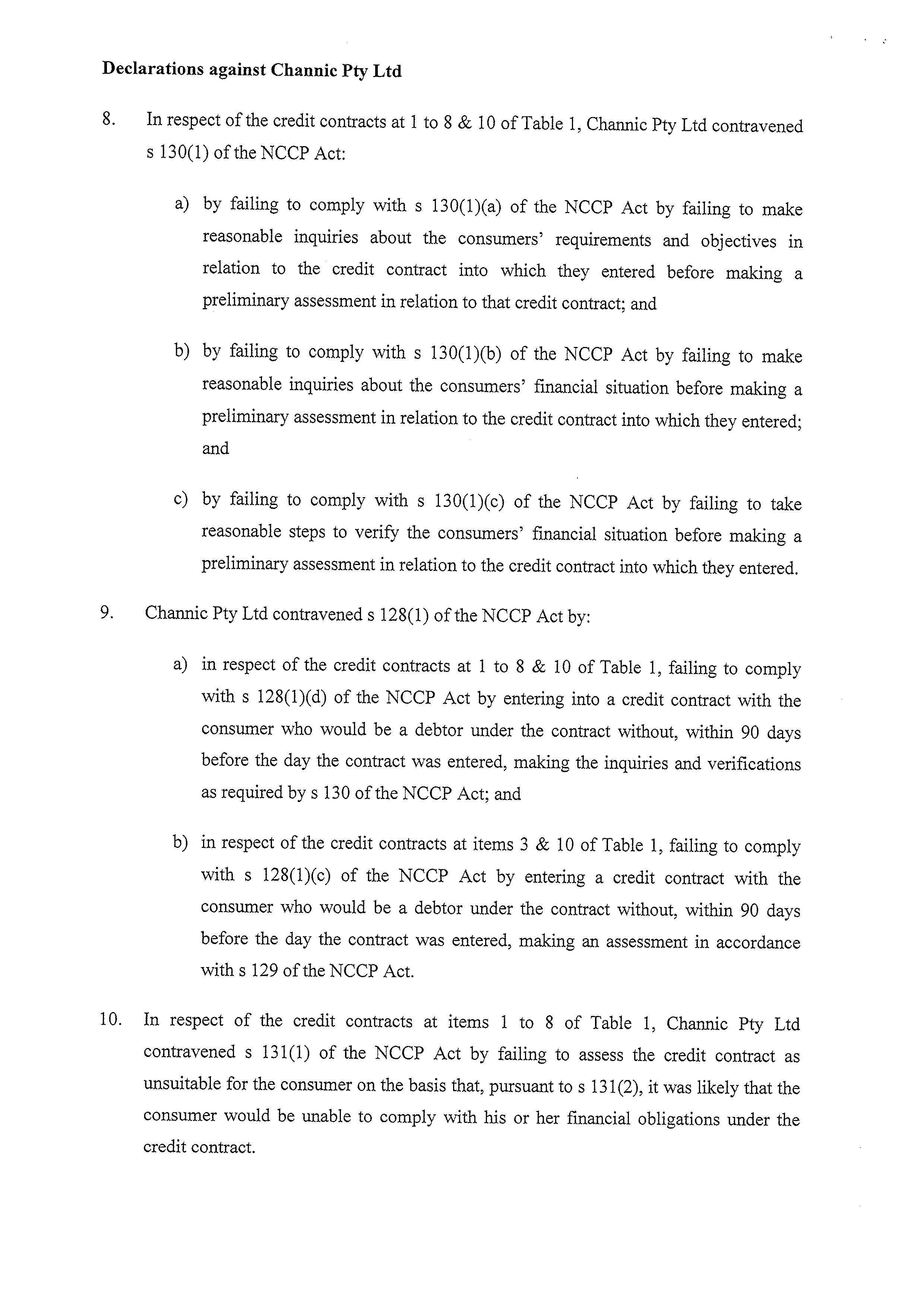

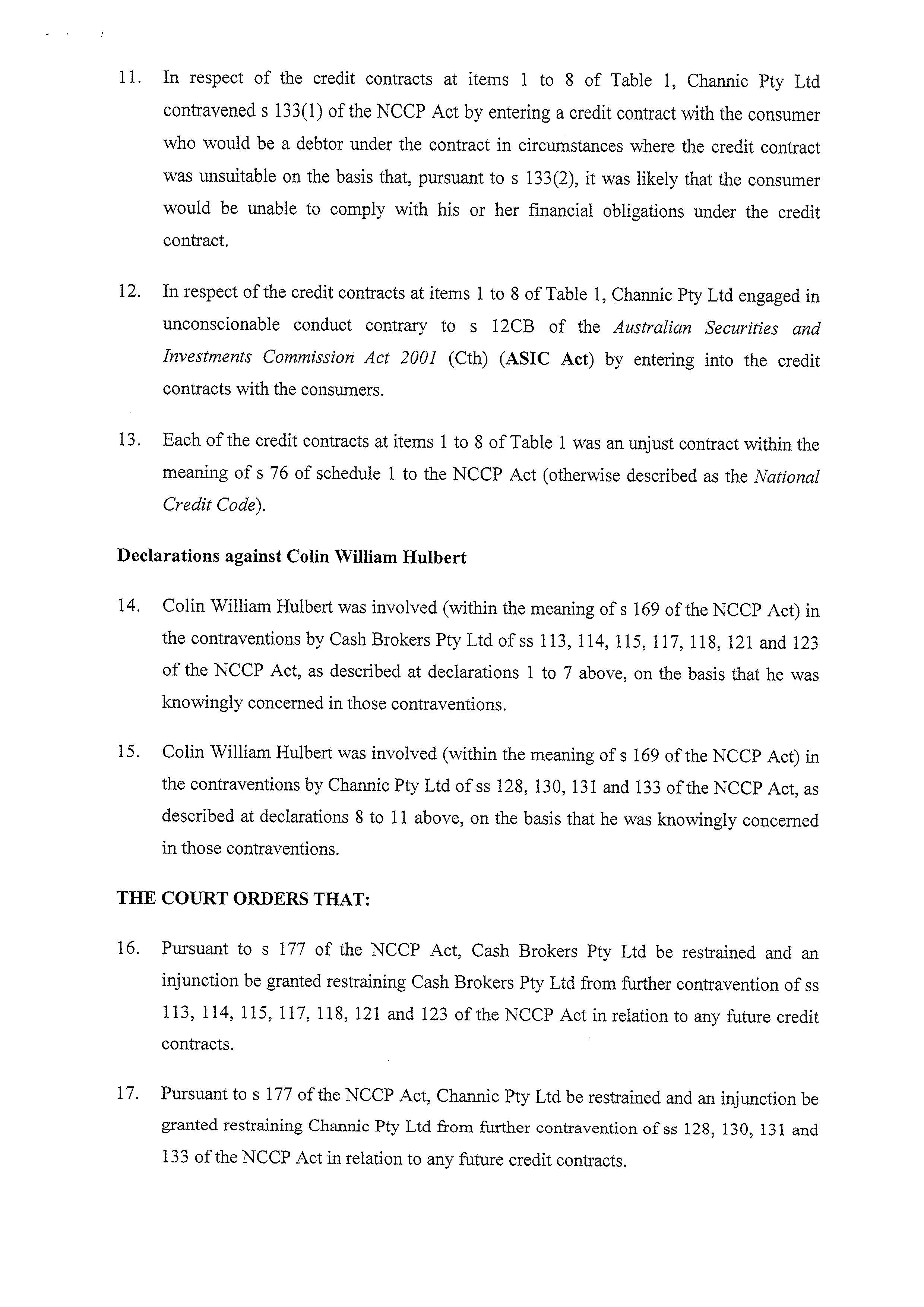

1. Channic Pty Ltd pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth of Australia fixed in the amount of $278,000.00.

2. Cash Brokers Pty Ltd pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth of Australia fixed in the amount of $278,000.00.

3. Colin William Hulbert pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth of Australia fixed in the amount of $220,000.00.

4. The credit contracts set out below are set aside ab initio.

Item | Name of Consumers | Date of Credit Contract |

1 | Adele Dorothea Kingsburra | 13 July 2010 |

2 | Prunella Kathleen Harris | 20 September 2010 |

3 | Rhonda Lorraine Brim | 22 September 2010 |

4 | Kerryn Gerthel Smith | 15 April 2011 |

5 | Joan Cecily Noble & William Damien Noble | 2 March 2011 |

6 | Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah & Estelle Harris | 16 July 2010 |

7 | Charlotte Mudu & Aaron Elliott | 14 December 2010 |

8 | Donna Gayle Yeatman & Farren Yeatman | 16 September 2010 |

5. The consumers described in the schedule in Order 4 are relieved from any liability to Channic Pty Ltd arising out of the credit contracts identified at Items 1 to 8 by reference to the name of each consumer and the date of the credit contract.

6. The respondents pay the costs of the applicant of and incidental to the proceeding fixed in an amount of $420,000.00.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GREENWOOD J:

background

1 On 30 September 2016, the Court published judgment in relation to contentions on the part of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”) concerning a series of alleged contraventions by the respondents of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (the “NCCP Act”) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the “ASIC Act”): Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 4) [2016] FCA 1174 (the “Liability Judgment” (“LJ”)).

2 On 1 November 2016, the Court made a series of declarations in relation to the conduct of Channic Pty Ltd (“Channic”) and Cash Brokers Pty Ltd (“CBPL”). The Court also made declarations in relation to the conduct of Mr Colin William Hulbert. The Court also made restraining orders against Channic, CBPL and Mr Hulbert. I will return to aspects of the declarations later in these reasons. However, these reasons should be read in the context of the declarations and orders made on 1 November 2016 and in order to serve the virtue of convenience, the declarations and orders are attached as Schedule 1 to these reasons.

3 The application was otherwise adjourned for the hearing of proceedings in relation to the imposition of any civil penalties against each of the respondents pursuant to s 167 of the NCCP Act and in order to determine whether orders ought to be made pursuant to s 76 of the National Credit Code.

4 Having regard to the written and oral submissions of ASIC and the respondents, there are a number of matters which are not in controversy. They include the following: the description of the substance of the declarations and orders made on 1 November 2016; the proposition that the relevant consumer contracts ought to be the subject of orders pursuant to s 77 of the National Credit Code pursuant to the exercise of a power to re-open under s 76 of that Code (T, p 59, lns 27-34); the making of orders for the payment by Channic of particular amounts to particular consumers; and the notion that the quantification of the costs payable by the respondents, of and incidental to, the proceeding in a lump sum amount of $470,000.00 is “reasonable” (T, p 69, lns 29-34).

5 As to the matters concerning s 76 and s 77 of the National Credit Code, the Court made the following orders (which were not opposed) on 23 March 2017:

1. Channic Pty Ltd is to repay the following amounts to the consumers listed below:

(a) Adele Dorothea Kingsburra - $13,427.34;

(b) Prunella Kathleen Harris - $1,649.24;

(c) Rhonda Lorraine Brim - $3,763.14;

(d) Kerryn Gerthel Smith - $4,715.00;

(e) Joan Cecily Noble & William Damien Noble - $1,985.60;

(f) Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah & Estelle Harris - $2,998.49;

(g) Charlotte Mudu & Aaron Elliott - $6,325.25; and

(h) Donna Gayle Yeatman & Farren Yeatman - $9,734.55.

2. Further to the amounts in order 1 above, Channic Pty Ltd is to repay the following amounts to the consumers listed below:

(a) Prunella Kathleen Harris - $200.00;

(b) Rhonda Lorraine Brim - $100.00;

(c) Kerryn Gerthel Smith - $1,000.00;

(d) Joan Cecily Noble & William Damien Noble - $1,000.00; and

(e) Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah & Estelle Harris - $800.00.

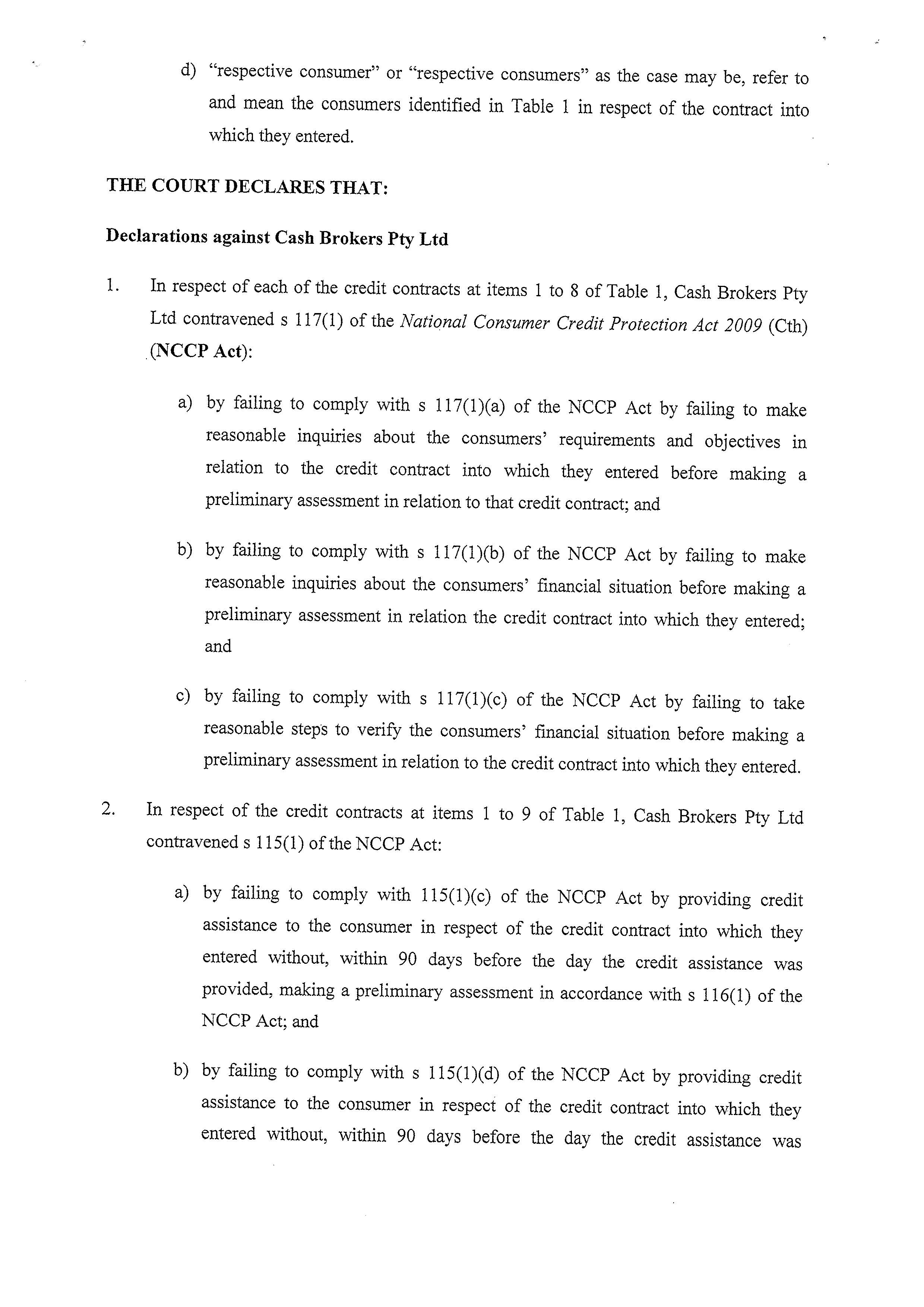

6 As to the substance of the declarations, the Court made declarations to the effect that Channic and CBPL had contravened various aspects of their responsible lending obligations as, respectively, a “credit provider” and “credit assistance provider” under the NCCP Act in relation to 10 consumer credit contracts (identified later in these reasons). The Court further declared that Channic had engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 12CB of the ASIC Act in relation to those consumer credit contracts and that those contracts were “unjust contracts” within the meaning of s 76, Schedule 1, to the NCCP Act (that is to say, the National Credit Code). Declarations were also made that Mr Hulbert was involved in the contraventions of both Channic and CBPL on the footing that Mr Hulbert was “knowingly concerned” in those contraventions.

7 On 28 November 2016, the Court ordered ASIC to file and serve submissions on the question of penalty together with any supporting affidavits, by 10 February 2017. Submissions were filed in relation to the question of the proposed imposition of civil penalties and in relation to the orders to be made under s 76 of the National Credit Code. The respondents filed submissions on these questions on 26 February 2017. ASIC relies upon the affidavit of Mr Hugh Daniel Copley sworn 9 February 2017 and a further affidavit of Mr Copley sworn 9 February 2017 in relation to the quantification of the costs. The quantum of the costs is no longer in issue. The respondents, however, contend that an order for costs in the amount of the unchallenged quantum ought not to be made having regard to three particular considerations. I will address those considerations in the course of these reasons. However, for present purposes, it is enough to note that the quantum of the costs is no longer in issue.

8 The respondents rely upon the affidavit of Mr Hulbert affirmed on 24 February 2017 and I will return to aspects of Mr Hulbert’s affidavit later in these reasons.

9 It should also be noted that the following short description of the findings of substance made in the principal liability judgment are not in issue. The principal questions in issue so far as the respondents are concerned go to the identification of the principles to be applied in determining a civil pecuniary penalty; the scope and depth of the conduct of the respondents in the context of the business activities of CBPL and, in particular, Channic; the application of the “one course of conduct” principle; the application of the “totality principle”; and related matters.

ASPECTS OF THE FINDINGS IN THE PRINCIPAL LIABILITY JUDGMENT

10 As to the substance of the findings made in the principal liability judgment, the following contextual matters at [11] to [29] of these reasons should be noted.

11 Mr Humphreys (acting on behalf of CBPL) failed to obtain detailed information about the expenditure commitments of consumers. Mr Humphreys had no instructions from Mr Hulbert about looking for patterns of expenditure and income in bank statements or about inquiring into deductions recited in Centrelink letters. Mr Humphreys and Mr Hulbert operated on the footing that a standardised formula adopted in the “Preliminary Test” document would be a relevant proxy for obtaining information about the actual expenses of each consumer. The adoption of a notional figure for expenditures did not constitute conduct of “making reasonable inquiries” about the consumer’s financial situation and nor did it satisfy an obligation of “verifying” the consumer’s financial situation: LJ at [1666] and [1736].

12 Neither CBPL (through Mr Humphreys or otherwise) nor Channic (through Mr Hulbert or otherwise) obtained bank statements from seven of the consumers referred to in the pleading: Brim, Harris, the Nobles, the Yeatmans, Kingsburra, Dabah and Mudu. Thus, the bank statements for these consumers were not available for the purposes of undertaking and performing the obligations required of each entity under the NCCP Act: LJ at [1680].

13 To the extent that bank statements were obtained from any of the other consumers, they were not examined for the purposes of determining the expenses of the consumer. Rather, they were examined for the purpose of checking whether the consumer had other loan contracts or whether other income was available to the consumer: LJ at [1687].

14 The “Credit Application Form” used by Channic and CBPL failed to properly isolate the expenses of the consumers. The attempt at identifying “actual expenses” was found to be both “derisory and perfunctory”. The completion of the Credit Application Form could not be taken seriously as an attempt to isolate actual expenses or provide a person with a basis for understanding or inquiring into a consumer’s expenses or the balance between a consumer’s income and his or her expenses with a view to forming an assessment of the “suitability” of the proposed loan: LJ at [1700].

15 As to the brokerage fee to be paid to CBPL, the first occasion upon which consumers may have become aware of any brokerage fee payable to CBPL was at the moment in time when the consumer was called upon to consider and execute the loan contract document with Channic: LJ at [1742].

16 As to the consumer’s requirement for “credit assistance”, CBPL failed to make inquiries about the consumer’s requirements for credit assistance. That assistance would ultimately engage the payment of a “brokerage fee” to CBPL. CBPL failed to make proper inquiries as to whether any brokerage fee was itself to be the subject of “credit assistance” as part of the application to Channic for loan funds which ultimately would be recited in the loan contract with Channic: LJ at [1745]. Although Mr Humphreys for CBPL assisted consumers to apply for credit, Mr Humphreys knew that the application for credit would be sent to Channic and that Channic would charge an interest rate of 48%. In the Liability Judgment, the Court determined that Mr Humphreys did not tell consumers that the interest rate would be 48%: LJ at [1748]. Nor were consumers told of the interest rate until the moment when they were signing the credit contract with Channic, with Mr Hulbert: LJ at [1750].

17 The basis of the remuneration paid to Mr Humphreys (the only basis) was commission payments. The first commission payment was paid to him based on a completed sale of a motor vehicle. The commission payment was payable by the seller, Supercheap. The second commission payment was a finance commission payable to him by Channic on the entry of a consumer (buyer) into a loan contract. This remuneration arrangement had the effect of discouraging Mr Humphreys (and thus CBPL) from bringing the consumer’s actual expenses to account as part of a reasonable inquiry process or as part of a process of taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial position: LJ at [1765].

18 The credit contracts in respect of which CBPL assisted consumers to obtain finance from Channic were unsuitable for those consumers because, having regard to the financial position of each consumer, it was likely that each consumer would be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under the terms and conditions of the Channic loan contract: LJ at [1784].

19 Having regard to the pattern of income and expenditure reflected in the bank statements of the consumers in issue, it would have been clear that the borrowers would not have been able to meet the additional financial obligations of further loan repayments: LJ at [1785].

20 As to the role played by CBPL in acting as a so-called broker, CBPL did not actually “broker” anything in the sense of seeking to identify the best available deal in the market for the particular consumer. That failure was due to the fact that CBPL was only ever going to refer a consumer’s application for credit to Channic, being the entity from which Mr Humphreys would obtain a finance commission in addition to the payment of the commission from Supercheap. The Court found that there was no doubt that Mr Hulbert knew and understood these arrangements and that they would work in the way described: LJ at [1815]. Because Mr Hulbert set the terms of remuneration payable to Mr Humphreys, he knew that the only remuneration Mr Humphreys received was a commission from Supercheap and CBPL.

21 As to Mr Hulbert’s knowledge, he also knew the manner in which Mr Humphreys went about completing the Credit Application Form and the Preliminary Test document. Channic simply relied upon the materials provided to it by CBPL. However, Channic needed, as a matter of statutory obligation, to bring its own inquiring mind to the relevant statutory matters: LJ at [1804].

22 Mr Hulbert engaged with each consumer in relation to the Channic loan contract and its execution. The explanation of the relevant matters contained in the loan contract was given to each consumer as part of a well-rehearsed form of patter described in the Liability Judgment as a “spiel” (a term used by Mr Hulbert). The Court found that it must have been transparently plain to Mr Hulbert that the consumers in issue in the proceedings, to the extent that they understood or comprehended any particular element of the spiel, would have done so in a most transient way with no real comprehension or understanding of the derivation of the amount of credit in question; the interest component in dollar terms; the rate of interest (in a number of cases); the total body of repayments; and other such matters. The Court found that there was no relevant understanding of these matters on the part of the consumers: LJ at [1651].

23 As to the moment in time when consumers were advised of the material matters relating to the loan contract with Channic, it was not until Mr Hulbert conducted his interview with each consumer so as to explain the Channic loan contract and secure its execution, that any of the consumers were informed about the amount of credit; the interest rate; the total amount of interest payable under the terms and conditions of the document; the total number of weekly or fortnightly payments; the amount of those regular payments; the total repayments under the credit contract; the fees and charges; and (apart from Ms Raymond), the amount of brokerage which was, first, payable to CBPL and, second, brought within the credit contract as an amount to be financed by credit. The Court found that Channic could not possibly have conducted reasonable inquiries into the requirements and objectives of each consumer in relation to the particular credit contract and the various elements of its terms and conditions and the obligations each consumer would assume under it: LJ at [1806].

24 As to the interview with Mr Hulbert, the interview was conducted with the consumer not for the purpose of determining the requirements and objectives of the consumer but simply to tell the consumer what was in the contract on the day: LJ at [1807].

25 As to the extent of knowledge of Mr Hulbert about these failures on the part of CBPL and Channic, the Court found that CBPL and Channic were no more than “wafer thin transparent membranes” between the consumer and Mr Hulbert. The Court found that Mr Hulbert knew and understood every aspect of the conduct of CBPL and Channic: LJ at [1821].

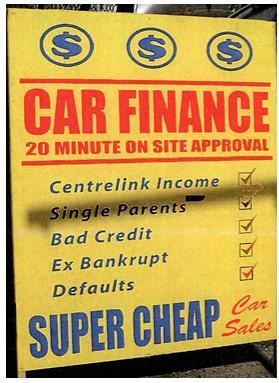

26 As to the circumstances of the consumers in question, the Court found that many of the consumers endured difficult family circumstances, were of limited education and lacked financial literacy: LJ at [1831] and [1832]. The Court found that many of these consumers came to Supercheap as a place of last resort for the purchase of a motor vehicle, believing it to be a place where persons in difficult financial circumstances would be able to buy a motor vehicle through some kind of purchase arrangement: LJ at [1833]; see the image at [94] of the Liability Judgment; and [82] ([11] of these reasons) . Each of the consumers in issue was in very difficult financial circumstances. Plainly enough, they depended upon Centrelink benefits to keep their family going and they expended their benefit receipts virtually immediately once they were obtained: LJ at [1835].

27 The Court found that all of these considerations, taken together, made it plain to Channic that these consumers were in a significantly disadvantaged position as compared with Channic when they came to the question of entering into the credit contract: LJ at [1836]. The Court found that Mr Hulbert must have been aware of these circumstances: LJ at [1837].

28 As to the vehicles, the Court found that there was a significant difference between the sale price of the vehicles sold to the relevant consumer and the cost of that vehicle to Supercheap. The Court found that there was also a significant difference between the sale price and the value of the vehicles: LJ at [1839] and [1840].

29 The Court found that in all the circumstances, Channic’s entry into each credit contract with each consumer with the corresponding assumption by that consumer of the burden of the terms and conditions of the contract, was the expression of unconscionable conduct under s 12CB of the ASIC Act: LJ at [1844].

THE CONTRACTS AND THE CONTRAVENTIONS BY CHANNIC, CBPL AND MR HULBERT

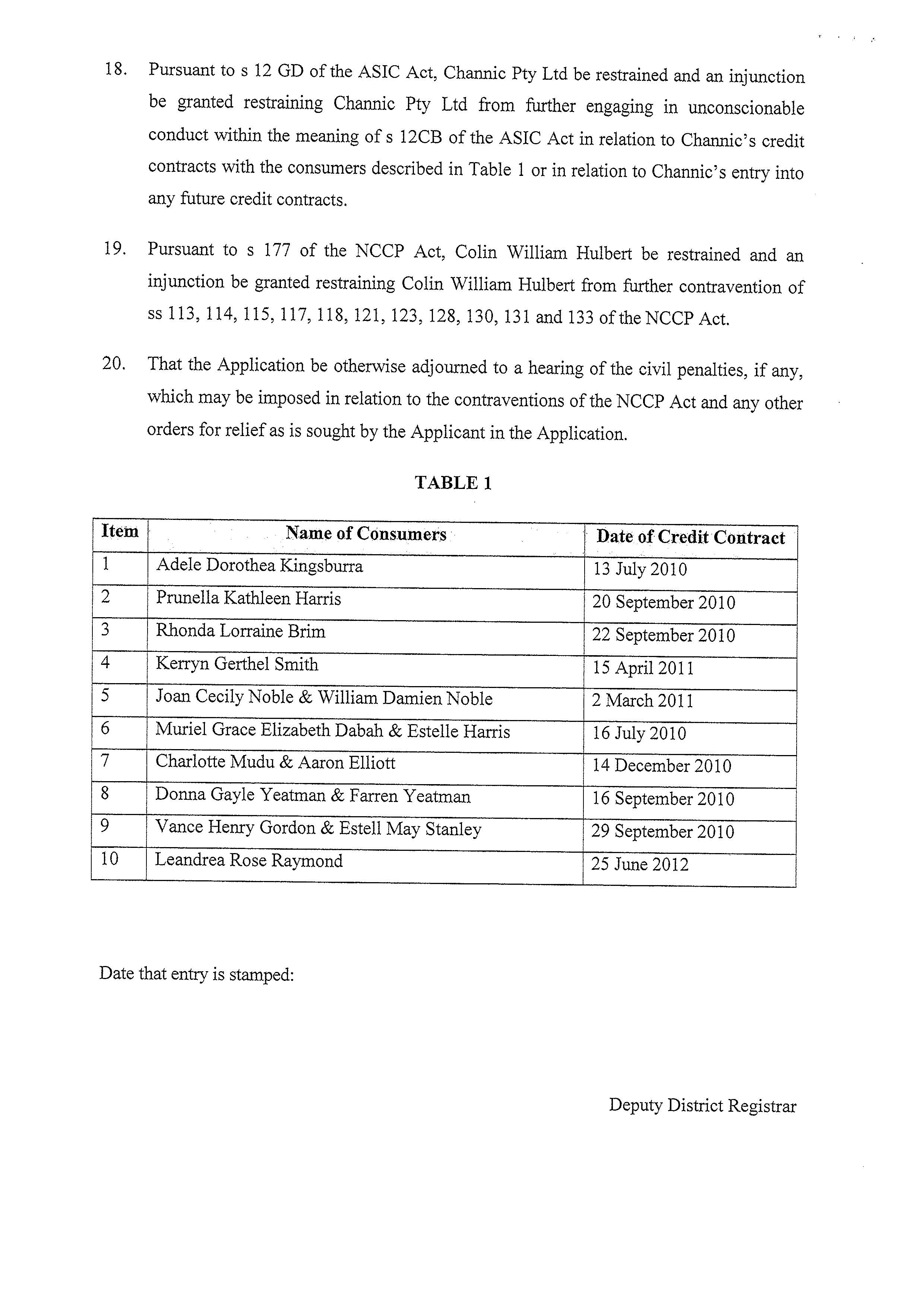

30 The schedule set out below (the “Contracts Schedule”) identifies each of the credit contracts by reference to the name of the consumer or consumers who were parties to the contract with Channic and the date on which each contract was entered into. The declarations of contraventions (see Schedule 1 to these reasons) on the part of CBPL and Channic were made by reference to this schedule.

Item | Name of Consumers | Date of Credit Contract |

1 | Adele Dorothea Kingsburra | 13 July 2010 |

2 | Prunella Kathleen Harris | 20 September 2010 |

3 | Rhonda Lorraine Brim | 22 September 2010 |

4 | Kerryn Gerthel Smith | 15 April 2011 |

5 | Joan Cecily Noble & William Damien Noble | 2 March 2011 |

6 | Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah & Estelle Harris | 16 July 2010 |

7 | Charlotte Mudu & Aaron Elliott | 14 December 2010 |

8 | Donna Gayle Yeatman & Farren Yeatman | 16 September 2010 |

9 | Vance Henry Gordon & Estell Mary Stanley | 29 September 2010 |

10 | Leandrea Rose Raymond | 25 June 2012 |

31 There is no controversy between the parties as to the contraventions by Channic, CBPL and Mr Hulbert. The contraventions by Channic by reference to the relevant legislation, cross-referenced to the relevant contracts, is set out below:

Contravention | Applicable contracts | No. of breaches |

s 130(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 & 10 | 9 |

s 128(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 & 10 | 9 |

s 131(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 133(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 12CB ASIC Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

Total number of civil penalty breaches | 42 | |

32 The contraventions by CBPL by reference to the NCCP Act, cross-referenced to the relevant contracts, is set out below:

Contravention | Applicable contracts | No. of breaches |

s 117(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 115(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 9 | 9 |

s 118(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 123(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 113(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

s 114(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

s 121(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

Total number of civil penalty breaches | 39 | |

33 The contraventions by Mr Hulbert by reference to the NCCP Act, cross-referenced to the relevant contracts, is set out below:

Contravention | Applicable contracts | No. of breaches |

s 130(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 & 10 | 9 |

s 128(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 & 10 | 9 |

s 131(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 133(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 117(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 115(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 9 | 9 |

s 118(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 123(1) NCCP Act | 1 to 8 | 8 |

s 113(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

s 114(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

s 121(1) NCCP Act | 4 & 5 | 2 |

Total number of civil penalty breaches | 73 | |

34 Each of these provisions is a civil penalty provision. Division 2 of Pt 4-1 of Ch 4 of the NCCP Act addresses the topic: “Declarations and pecuniary penalty orders for contraventions of civil penalty provisions”. Section 167(2) provides that if a declaration has been made concerning a contravention of a civil penalty provision (under s 166 of the NCCP Act) by a person, the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty “that the court considers is appropriate (but not more than the amount specified in subsection (3))”. Subsection (3) of s 167 provides that the pecuniary penalty must not be more than the maximum number of penalty units referred to in each civil penalty provision, if the contravener is a natural person. If the contravener is a body corporate, the penalty must not be more than five times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant section.

35 In respect of each of the NCCP Act provisions relevant to these proceedings the maximum penalty for an individual is 2,000 penalty units. By operation of s 167(3)(b), the maximum penalty for a body corporate in respect of each provision in issue is 10,000 penalty units. At the time each contract relevant to these proceedings was entered into, the quantum of a penalty unit was $110.00: s 4AA, Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). Accordingly, the maximum amount of the penalty for each single civil penalty contravention is $220,000.00 for an individual and $1.1 million for a body corporate.

36 Although s 167(2) confers discretionary power upon the Court to order a pecuniary penalty the Court considers appropriate (within the limits set by s 167(3)), the NCCP Act does not recite any statutory considerations to be taken into account in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty to be ordered in the exercise of the power. Nor does the NCCP Act recite any statutory objectives of, or for, any of the provisions the subject of the contraventions in these proceedings. The Explanatory Memorandum (the “EM”) for the Bill (the Credit Bill) for the NCCP Act contains a discussion under the heading “Sanctions and remedies regime” commencing at para 4.16. The role of criminal sanctions is discussed in the EM at paras 4.21 to 4.25 and the role of civil penalties is discussed at paras 4.26 to 4.30. These observations in the EM in relation to civil penalties should be noted:

4.26 Civil penalty sanctions apply in the Credit Bill where the misconduct affects or potentially affects the integrity of the credit market and where there may be an absence of malicious or reckless intention. Civil sanctions have a lower burden of proof than criminal sanctions and are an alternative source of imposing legal obligations and deterring conduct.

4.27 It is also recognised that civil penalties play a useful role for regulating corporate wrongdoing as the amount of the penalty is a disincentive for corporate misbehaviour. They are also used as alternatives to criminal penalties.

4.28 For example, civil penalties are utilised instead of criminal sanctions in some responsible lending requirements, noting that the main ‘harm’ (entering or suggesting an unsuitable credit contract) is being rectified as both an indictable offence and civil penalty. Often breaches of these laws adversely affect the consumer where they have been placed in an ‘unsuitable’ credit product.

[emphasis added]

37 In other words, neither s 167 nor any other section of the NCCP Act sets out considerations of the kind contained in s 76(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) informing the appropriateness of a particular pecuniary penalty: see the qualifying words in s 76(1) in the following terms:

… having regard to all relevant matters including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under [the relevant Part or Parts] to have engaged in any similar conduct.

38 Section 175 of the NCCP Act should also be noted. It is in these terms, relevantly:

175 Civil doubt jeopardy

If a person is ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under a civil penalty provision in relation to particular conduct, the person is not liable to be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under some other provision of a law of the Commonwealth in relation to that conduct.

[emphasis added]

THE NORMATIVE CHARACTER OF THE PROVISIONS

39 It is now necessary to examine the normative character of the conduct proscribed by the relevant sections of the NCCP Act the subject of the declarations as to the contravening conduct of CBPL, Channic and Mr Hulbert.

40 Part 3-1 of Ch 3 of the NCCP Act addresses the following topics in relation to the role and conduct of “credit assistance providers”:

Division 2 – Credit guide of credit assistance providers

Division 3 – Quote for providing credit assistance etc. in relation to credit contracts

Division 4 – Obligations of credit assistance providers before providing credit assistance for credit contracts

Division 5 – Fees, commissions etc. relating to credit contracts

Division 6 – Prohibition on suggesting, or assisting with, unsuitable credit contracts

41 These divisions represent the scheme of the Act in relation to credit assistance providers. CBPL acted as a credit assistance provider in relation to the credit contracts recited as Items 1 to 9 of the Contracts Schedule.

42 As to Div 4, s 115(1) cast an obligation upon CBPL not to provide credit assistance to a consumer on a relevant day (called the “assistance day”) by suggesting that the consumer apply, or assisting the consumer to apply, for a particular credit contract (in this case the Channic loan contract) with a particular credit provider (in this case Channic) unless CBPL has, within 90 days (relevantly) before the assistance day, made a “preliminary assessment” in accordance with s 116(1) of the NCCP Act, and one that covers the period proposed for entering into the credit contract (the s 115(1)(c) requirement) and the credit assistance provider has made the inquiries and undertaken the verification required by s 117(1): the s 115(1)(d) requirement.

43 As to the preliminary assessment contemplated by s 115(1)(c), s 116(1) provides that CBPL was required to make a preliminary assessment that specifies the period covered by the assessment and one that assesses whether the credit contract “will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered [into]”.

44 As to the inquiries to be made and the verification steps to be undertaken, as contemplated by s 115(1)(d), s 117(1) provides that before making the preliminary assessment required by s 115(1)(c) in conformity with s 116(1), CBPL must:

(a) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; and

(b) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and

(c) take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation; and

…

45 The scheme of ss 115, 116 and 117 is plain enough. The so-called “broker” (CBPL) as a credit assistance provider was required to make a preliminary assessment of whether the proposed credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if taken up and in order to make that assessment, CBPL was required to put itself in an informed position by making reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives concerning the contract and the consumer’s financial position. CBPL was then required to verify the consumer’s financial position. All of this was required to be done before making the preliminary assessment. In the absence of these things, CBPL was required not to provide credit assistance on the assistance day. The purpose of these provisions is to cast obligations upon a credit assistance provider as a means of providing a meaningful assessment to the consumer of whether the particular credit contract is suitable or unsuitable for that consumer having regard to the fact of the assessment conditioned by the requirements of, relevantly, s 117(1)(a), (b) and (c). In a normative sense, the scheme of the sections is the protection of the consumer from the burdens of a potentially “unsuitable” credit contract by arming the consumer with an assessment that informs the consumer’s decision-making about entering into the credit contract.

46 CBPL, in relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule, failed to take the steps required of it arising under s 117(1)(a), (b) and (c).

47 As to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 9 of the Contracts Schedule, CBPL failed to comply with s 115(1), by failing to comply with the requirements of s 115(1)(c), by providing credit assistance to each of those consumers in relation to the relevant Channic credit contract without (within 90 days before the credit assistance day) making a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 116(1) of the NCCP Act.

48 CBPL also failed to comply with s 115(1) in relation to each of the credit contracts at Items 1 to 9 of the Contracts Schedule by providing credit assistance to each consumer concerning the Channic credit contract without (within the relevant period) making the inquiries and undertaking the verification required by s 117(1).

49 Section 118(1) (also within Div 4) cast an obligation on CBPL to “assess that the [Channic] contract will be unsuitable for the consumer” for the purposes of the s 116(1) preliminary assessment, if the credit contract was rendered unsuitable by operation of s 118(2). Section 118(2) provides that the contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time of the preliminary assessment, it is likely that the consumer will be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under the contract or could only comply with those obligations with substantial hardship (s 118(2)(a)), or the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives: s 118(2)(b).

50 CBPL, in relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule, contravened s 118(1) by failing to assess each Channic credit contract as “unsuitable” on the basis that the contract was rendered unsuitable under s 118(2) because it was likely that each consumer would be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under the credit contract.

51 The statutory purpose of s 118 is to make plain (and ensure) that at the time of the preliminary assessment, a credit assistance provider assesses the contract as unsuitable once it is likely (assessed at that time) that the consumer will be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under it. The statute recognises that such a contract will be unsuitable because the likelihood, at the date of the preliminary assessment, is that the consumer will fall into breach with all that that entails under, and by reference to, the credit contract.

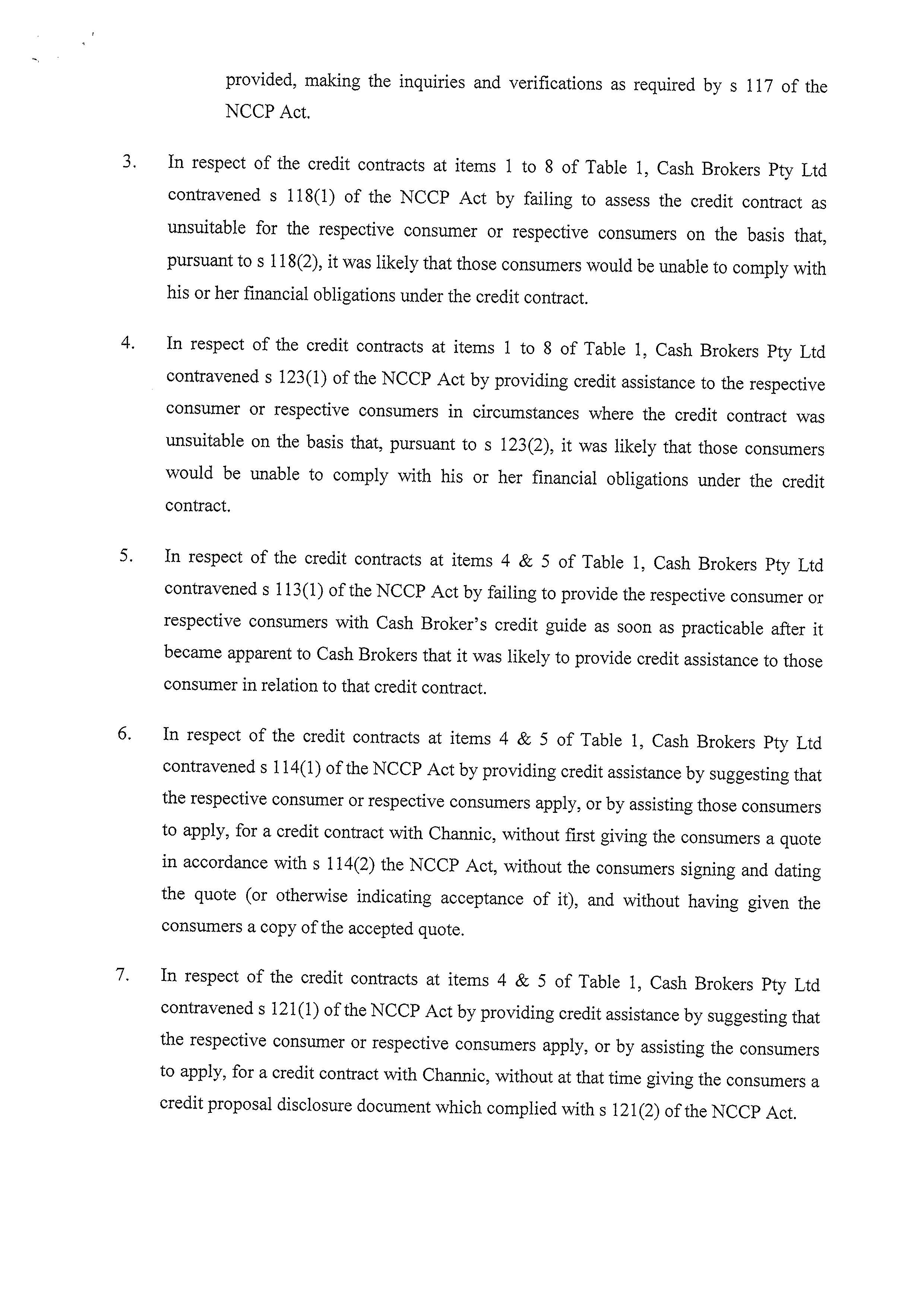

52 Section 113(1) (Div 2) cast an obligation on CBPL to give the consumer its “credit guide” (which is required to meet the requirements of s 113(2)), as soon as practicable after it becomes apparent to CBPL that CBPL is likely to provide credit assistance to a consumer in relation to a credit contract. In respect of the credit contracts at Items 4 and 5 of the Contracts Schedule, CBPL failed to comply with the s 113(1) obligation.

53 Section 114(1) (Div 3) cast an obligation on CBPL not to provide credit assistance to a consumer by suggesting that a consumer apply, or by assisting a consumer to apply, for a particular credit contract (the Channic credit contract) with a particular credit provider (Channic) unless CBPL has given the consumer a quote which meets the requirements of s 114(2), (s 114(1)(d)), and the consumer has signed and dated the quote or otherwise indicated the consumer’s acceptance of it in any manner as prescribed by the Regulations (if at all) (s 114(1)(e)), and CBPL has given the consumer a copy of the accepted quote: s 114(1)(f). In respect of the credit contracts at Items 4 and 5 of the Contracts Schedule, CBPL failed to comply with s 114(1) by providing credit assistance to those consumers without first providing a quote in accordance with s 114(2) and without those consumers having signed and dated a quote or otherwise accepted a quote and without having given the consumers a copy of an accepted quote.

54 Finally, s 121 (Div 5) cast an obligation on CBPL in respect of the credit contracts at Items 4 and 5 of the Contracts Schedule, to give, at the same time as providing credit assistance to a consumer (in relation to the relevant Channic credit contract), a “credit proposal disclosure document” in accordance with s 121(2) of the NCCP Act. CBPL failed to comply with that obligation.

55 As to these matters at [40] to [54] of these reasons, see Declarations 1 to 7, Sch 1.

56 Many of the obligations imposed upon a credit assistance provider reflect a normative corresponding obligation cast upon a credit provider (Channic), adjusted according to the role of a credit provider.

57 Part 3-2 of Ch 3 of the NCCP Act relevantly addresses these topics:

Division 3 – Obligations of credit providers before entering credit contracts or increasing credit limits

Division 4 – Prohibition on entering, or increasing the credit limit of, unsuitable credit contracts

58 Section 128 (Div 3), put simply, cast a prohibition upon Channic entering into a credit contract on a relevant day (called the “credit day”) with a consumer (who will be a debtor under the contract) unless Channic has (within the relevant period) made an assessment in accordance with s 129 of the NCCP Act (s 128(c)) and made the inquiries and undertaken the verification steps required by s 130 of the NCCP Act: s 128(d).

59 Section 129 requires Channic to make an assessment that assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable if entered into by the consumer. Before making that assessment, Channic must, for the purposes of s 128(d), make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract (s 130(1)(a)); make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation (s 130(1)(b)); and take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation (s 130(1)(c)).

60 The same essential statutory obligations “protective” of the consumer in relation to a credit contract imposed upon a credit assistance provider are, unsurprisingly, also imposed upon the credit provider itself. The credit provider, of course, will be a party to the bilateral credit contract with the consumer. The credit provider will enjoy the benefits (and to some degree the burdens of the contract) and so too will the consumer assume the burdens of the credit contract and the relevant benefits it confers.

61 Section 131(1) (Div 3) requires Channic to assess “that the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer” if the contract will be unsuitable by operation of s 131(2). Section 131(2) provides that the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if at the time of the assessment, it is likely that:

(a) the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship, if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in the period covered by the assessment; or

(b) the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in the period covered by the assessment; or

…

62 Section 133(1) (Div 4) relevantly cast an obligation on Channic not to enter into a credit contract with a consumer (who would be the debtor under that contract) if the credit contract is unsuitable by operation of s 133(2). The contract is unsuitable for the consumer under s 133(2) if (among other things), at the time it is entered into, it is likely that the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract (or only do so with substantial hardship).

63 In relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 and 10 of the Contracts Schedule, Channic failed to comply with s 130(1) by failing to comply with s 130(1)(a), (b) and (c).

64 In relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 and 10 of the Contracts Schedule, Channic failed to comply with s 128, by failing to comply with s 128(d), by entering into a credit contract with those consumers (who would become debtors under the contracts) without (within the relevant 90 day period) making the inquiries and undertaking the verification steps required by s 130(1) of the NCCP Act.

65 In relation to the credit contracts at Items 3 and 10 of the Contracts Schedule, Channic failed to comply with s 128, by failing to comply with s 128(c), by entering into a credit contract with those consumers (who would be debtors under the contracts) without (within the relevant 90 day period) making an assessment in accordance with s 129 of the NCCP Act.

66 In relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule, Channic failed to comply with s 131(1) by failing to assess the relevant credit contract as unsuitable for each consumer on the basis that, by operation of s 131(2), it was likely that the consumer would be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under the credit contract.

67 In relation to the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule, Channic failed to comply with s 133(1) of the NCCP Act by entering into a credit contract with each consumer (where each consumer would be a debtor under the contract) in circumstances where the credit contract was unsuitable for the consumer on the footing that s 133(2) operated to render the contract unsuitable as it was likely that the consumer would be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under it.

68 As set out at [33], Mr Hulbert was knowingly concerned in each of the relevant contraventions by CBPL and Channic.

69 As to the “essential character” of these provisions of the NCCP Act in respect of which contraventions have occurred, as they apply to a credit provider and a credit assistance provider, the statutory purpose is to put in place a series of checks and balances at various steps along the way leading to entry (or not) by a consumer into a credit contract with a view to securing an assessment of whether the proposed contract is unsuitable for the consumer having regard to the statutory considerations upon which the assessment is to be made. The purpose of the provisions is also to cast an obligation on a credit provider (as the party most directly engaged with the consumer by reason of the credit contract) not to enter into the credit contract if the contract is unsuitable for the consumer (according to the statutory considerations) and to cast an obligation on a credit assistance provider not to provide credit assistance to the consumer as to entry into a credit contract if the proposed credit contract is unsuitable for the consumer according to the statutory considerations going to the assessment. The balance to be struck is one between the interests of the credit provider (and the credit assistance provider) in providing the relevant services, on the one hand, and the protection of the interests of the consumer/debtor in being a party to only those contracts that are not unsuitable in the statutory sense, on the other hand.

70 In assessing an appropriate pecuniary penalty in respect of the contraventions by each respondent, the Court must keep in mind the essential character of the provisions, the balance the provisions seek to achieve and the underlying purpose the provisions seek to serve.

71 Apart from the NCCP Act considerations, Channic contravened s 12CB of the ASIC Act. The Court found that Channic had engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of that section in relation to the consumer contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule and that those contracts were “unjust contracts” within the meaning of s 76 of the National Credit Code.

THE SECTION 175 CONSIDERATIONS

72 It is now necessary to return to s 175 of the NCCP Act in the context of assessing whether, in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty in respect of each contravention, the same conduct has given rise to more than one contravention of a civil penalty provision. If, for example, CBPL is ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty in relation to “particular conduct” under a civil penalty provision, it is “not liable” to a further pecuniary penalty under “some other provision” of a law of the Commonwealth in relation to “that conduct”, including another civil penalty provision under the NCCP Act: s 175, NCCP Act.

73 I accept that the approach adopted by ASIC on this question is a correct one. It can be illustrated in the following way.

74 Declaration 1, Sch 1, addresses “particular conduct” of CBPL. The first class of conduct concerns a failure by CBPL to comply with s 117(1)(a) by failing to make reasonable inquiries of each of the consumers the subject of the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule about their requirements and objectives in relation to the relevant credit contract into which they entered, before making the preliminary assessment in relation to the relevant credit contract as required by s 115(1)(d). That inquiry is one of the inquiries required by s 117(1) for the purposes of s 115(1)(d).

75 The second class of conduct addressed by Declaration 1 concerns a failure by CBPL to comply with s 117(1)(b) by failing to make reasonable inquiries of each of the same consumers about their financial situation before making a preliminary assessment in relation to the credit contract.

76 The third class of conduct addressed by Declaration 1 concerns a failure by CBPL to comply with s 117(1)(c) by failing to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial information.

77 Each class of conduct is an entirely separate failure or omission by CBPL in respect of each of the credit contracts at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule. Nevertheless, ASIC approaches the matter adopting two positions. First, the contraventions of s 117(1)(a), (b) and (c) have been “grouped together” so as to constitute, for the purposes of determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty, a single contravention. Thus, ASIC urges a pecuniary penalty in relation to a single contravention of s 117(1) in respect of the eight contracts engaged by Declaration 1. However, each of these eight contraventions also gives rise to a failure to comply with s 115(1)(d) because CBPL provided credit assistance to each of the consumers at Items 1 to 8 of the Contracts Schedule without complying with s 117(1). The second element of ASIC’s proposition is that CBPL is not liable to a further pecuniary penalty concerning a contravention of s 115(1) based on the conduct giving rise to non-compliance with s 117(i).

78 However, a contravention of s 115(1) might otherwise arise based upon other “particular conduct”. That is precisely what occurred. CBPL failed to comply with s 115(1)(c), by providing credit assistance to each of the relevant consumers (see Declaration 2(a), Sch 1) in respect of the credit contract they entered into with Channic without (within 90 days before the day credit assistance was provided), making a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 116(1) as required by s 115(1)(c). Thus, a contravention of s 115(1) arose although not based on s 117(1) conduct. In that sense, the “particular conduct” constituting a contravention of s 115(1)(c) does not overlap with conduct the subject of the other declarations.

79 The same approach has been adopted in relation to each of the contraventions by CBPL at [32] and in relation to the conduct of Channic the subject of the contraventions set out at [31] of these reasons.

80 Accordingly, having regard to this approach, a pecuniary penalty Channic or CBPL might be ordered to pay in respect of each of the contraventions set out at [31] and [32] respectively of these reasons does not offend s 175 of the NCCP Act.

the principles to be applied in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty

81 The principles I apply are these:

(1) Section 167(2) confers discretionary power on the Court to impose a pecuniary penalty that the Court “considers appropriate” uninformed by any specific statutory criteria upon which that discretionary judgment might be made.

(2) The statements in the EM suggest that the objective to be achieved in ordering an appropriate pecuniary penalty is one of deterrence.

(3) The NCCP Act draws a distinction between offences and criminal proceedings on the one hand, and civil penalty proceedings attracting a pecuniary penalty, on the other hand.

(4) Whereas criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation, the purpose of a civil penalty proceeding is primarily, if not wholly, protective in promoting the public interest in compliance with the law (in this case the relevant provisions of the NCCP Act relating to credit assistance providers and credit providers): Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 326 ALR 476 (“Fair Work”) per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ at [55]; Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152. Speaking of s 76(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), French J (as his Honour then was) observed that the “principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act” (an observation quoted by the plurality in Fair Work at [55]).

(5) Civil penalties are not retributive: “but like most other civil remedies they are essentially deterrent or compensatory and therefore protective”: Fair Work, the plurality at [59].

(6) By providing for civil penalty proceedings in relation to the relevant provisions in question in these proceedings, the NCCP Act implicitly assumes the application of the general practice and procedure regarding civil proceedings and eschews the application of criminal practice and procedure: Fair Work, the plurality at [62].

(7) In the context of a “calculated contravention of legislation” French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [65] that general and specific deterrence must play a “primary role” in assessing the appropriate penalty “in cases of calculated contravention of legislation where commercial profit is the driver of the contravening conduct”. At [64], their Honours observed that the Full Court of this Court in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249 (“Singtel Optus v ACCC”) at [68] rightly concluded that the Court, in fixing a pecuniary penalty, must make it “clear to [the contravener], and to the market, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention … cannot be regarded as [an] acceptable cost of doing business”.

(8) The Court should leave no room for any impression of weakness in its resolve to impose penalties sufficient to ensure deterrence, not only of the parties engaged in the contravention, but also of others who might be tempted to think about contravening the relevant provisions: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (“NW Frozen Foods”) per Burchett, Kiefel JJ at 294-295.

(9) The contextual factors to be taken into account in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty include these considerations:

(a) the scale of each company in terms of its size, resources, revenues and market power;

(b) the nature, character, content, scope and depth of the contravening conduct;

(c) whether the conduct was deliberate;

(d) whether the conduct was undertaken without regard to the obligations imposed upon CBPL and Channic and the prohibitions imposed upon those corporations;

(e) the consequences of the conduct for those persons affected by the conduct;

(f) whether CBPL, Channic and Mr Hulbert co-operated with the Regulator; whether they caused defences to be withdrawn and whether they acknowledged liability in relation to the contravening conduct;

(g) whether the contravening conduct arose out of the conduct of senior management or the conduct of the guiding mind of each corporation;

(h) whether each corporation (and its guiding mind) has adopted a culture of compliance in relation to obligations arising under the NCCP Act.

(10) Notwithstanding that the civil penalty regime reflected in the NCCP Act, like the civil penalty regime in the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Act 2005 (Cth) the subject of the Fair Work decision, “eschews the application of criminal practice and procedure” and that the notion of “intuitive or instinctive synthesis” is a “uniquely judicial exercise” in the imposition of “punishment” in “criminal proceedings” (Fair Work, the plurality at [56]), nevertheless the exercise of the discretionary judgment required of the Court under s 167(2) of the NCCP Act continues to engage the principles derived from Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357 (“Markarian”) and Wong v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 584 (“Wong v The Queen”). As to those principles, the plurality in Markarian (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) made these observations:

(a) Express legislative provisions apart, neither principle, nor any of the grounds of appellate review, dictates the particular path that a sentencer, passing sentence in a case where the penalty is not fixed by statute, must follow in reasoning to the conclusion that the sentence to be imposed should be fixed as it is. The judgment is a discretionary judgment and, as the bases for appellate review reveal, what is required is that the sentencer must take into account all relevant considerations (and only relevant considerations) in forming the conclusion reached. [27]

(b) It follows that careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick. That having been said, in our opinion, it will rarely be, and was not appropriate for Hulme J here to look first to a maximum penalty, and to proceed by making a proportional deduction from it. That was to use a prescribed maximum erroneously, as neither a yardstick, nor as a basis for comparison of this case with the worst possible case. [31]

(c) In general, a sentencing court will, after weighing all the relevant factors, reach a conclusion that a particular penalty is the one that should be imposed. As Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said in Wong [at [74] – [76]]: “Secondly, and no less importantly, the reasons of the Court of Criminal Appeal suggest a mathematical approach to sentencing in which there are to be ‘increment[s]’ to, or decrements from, a predetermined range of sentences. That kind of approach, usually referred to as a ‘two-stage approach’ to sentencing, not only is apt to give rise to error, it is an approach that departs from principle [and] should not be adopted.” [37]

(d) Following the decision of this Court in Wong it cannot now be doubted that sentencing courts may not add and subtract item by item from some apparently subliminally derived figure … [39]

[emphasis added]

(11) As to the “course of conduct” principle, the principle recognises that where there is an inter-relationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is “essentially” the same criminality. That principle requires careful identification of what is the same criminality. Where two offences arise as a result of the “same conduct” or “related conduct”, the Court may have regard to the principle as one of the principles guiding the exercise of the sentencing discretion. The principle represents “a tool of analysis” which a court is not necessarily compelled to use: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] and [41], Middleton and Gordon JJ.

(12) As to the “totality principle”, the total penalty for each offence ought not to exceed what is regarded as a proper penalty for the entirety of the contravening conduct in question. The totality principle operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed on the contravener, considered overall, are just, fair and appropriate having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct involved. The principle operates as a “final overall consideration”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53, per Goldberg J.

(13) It follows, having regard to (11) and (12) above, that I accept that where a contravener has engaged in a number of contraventions, it may be appropriate, weighing all the relevant considerations, to impose a single penalty in respect of one course of conduct or a penalty in respect of each contravention and in assessing the penalty, the Court will then apply the totality principle as a final overall consideration to ensure that the total penalty in respect of “related contraventions” does not exceed a proper penalty for the entirety of the contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2010) 188 FCR 238, Middleton J at [235]; Singtel Optus v ACCC at [53].

(14) I have also had regard to the observations of the Full Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (2007) 161 FCR 513 at [58]-[62]. I have also had regard to the observations in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2016) 336 ALR 1 at [52]-[121].

(15) As to the “risk/benefit equation”, the Full Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25 per Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ at [151] and [152] said this:

151 All other things being equal, the greater the risk of consumers being misled and the greater the prospect of gain to the contravener, the greater the sanction required, so as to make the risk/benefit equation less palatable to a potential wrongdoer and the deterrence sufficiently effective in achieving voluntary compliance. Tipping the balance of the risk/benefit equation in this way is even more important when the benefit in contemplation is profit or other material gain. It is especially important if there are disadvantages, including increased costs or lesser sales or profits, in complying with legal obligations for those who “decide” to be law-abiding.

152 If it costs more to obey the law than to breach it, a failure to sanction contraventions adequately de facto punishes all who do the right thing. It is therefore important that those who do comply see that those who do not are dealt with appropriately. This is, in a sense, the other side of deterrence, being a dimension of the general deterrence equation. This is not to give licence to impose a disproportionate or oppressive penalty, which cannot be done, but rather to recognise that proportionality of penalty is measured in the wider context of the demands of effective deterrence and encouraging the corresponding virtue of voluntary compliance.

[emphasis added]

82 Having regard to the affidavit of Mr Copley sworn 9 February 2017 and the affidavit of Mr Hulbert affirmed 24 February 2017, I make the following findings of fact (also taking into account some of the earlier findings in the Liability Judgment):

(1) Channic has held an Australian Credit Licence (ACL) effective from 31 January 2011: HDC-36. On 14 June 2016, Mr Hulbert (on behalf of Channic) submitted a form to ASIC requesting cancellation of the licence. On 20 June 2016, ASIC sent an email to Mr Hulbert asking questions of him in relation to Channic’s credit activities as part of ASIC’s consideration of the request for cancellation. On 20 June 2016, Mr Hulbert responded saying that he could not respond until Mr Phillip Smiles returned to work. On 20 July 2016, ASIC sought a response from Mr Hulbert again. On 20 July 2016, Mr Hulbert responded saying that the “[a]pplication should be finalised by end of this week”. Mr Hulbert has not provided the information sought by ASIC. ASIC has not cancelled Channic’s licence. On 30 January 2017, Mr Hulbert contacted ASIC’s Call Centre pursuing his request to cancel Channic’s ACL. On 6 February 2017, ASIC responded to that inquiry by email stating that it was still waiting upon Mr Hulbert’s response to the questions raised by the 20 June 2016 email. At the time of swearing Mr Copley’s affidavit on 9 February 2017, Mr Hulbert had not responded to ASIC’s email request of 20 June 2016.

(2) In “about” October 2014, Channic’s loan book was sold to Cash Providers Australia Pty Ltd (“Providers”), although as at November 2014, Channic continued to operate under its ACL expressing an indication that it was engaged in a process of transferring its rights under Channic credit contracts to Providers. Providers was registered as a company on 19 February 2013. It has the same registered office as Channic and CBPL. Mr Hulbert was a director of Providers until 11 September 2013. Mr Wayne McKenzie was a director from 19 February 2013 until 2 July 2015. Since 2 July 2015, the directors have been Ms Georgina Ghislaine Bataillard and Mr Hulbert’s wife, Ms Juisticia Bontong Hulbert. Ms Bataillard is a person who provided book-keeping services to Channic, CBPL and Supercheap from time to time: LJ at [1544] to [1554]. Bataillard affidavit at paras 2 to 9. The sole shareholder in Providers is Juisticia Bontong Hulbert holding 200 fully paid shares although the documents lodged with ASIC (HDC-34 and HDC-35) by Ms Bataillard on behalf of Providers, recite that the shares are not beneficially held by her. Between 19 February 2013 and 9 March 2016, all of the shares in Providers held by Mr McKenzie and Mr Hulbert were progressively transferred to Juisticia Bontong Hulbert: Copley affidavit paras 6 to 9. Providers obtained an Australian Credit Licence under the NCCP Act effective from 15 March 2016: HDC-46. The licence authorises Providers to “engage in credit activities as a credit provider” by engaging in any one of 12 nominated activities. These activities recited in the licence are precisely the same activities recited in Channic’s ACL: HDC-36. The “key person” nominated in the Channic ACL (CL-2) is Mr Hulbert. The key person recited in the ACL issued to Providers is Georgina Bataillard.

(3) Juisticia Bontong Hulbert holds a “Care Services L2, AP1” classification and accreditation and is employed as a Care Worker by RSL Care RDNS Limited (“RSL Care”). For the financial year to 28 February 2017, Mrs Hulbert has received year to date gross income of $30,809.37 and net income of $26,959.37: Exhibit 58, tendered on behalf of the respondents.

(4) In the two week period 15 February 2017 to 28 February 2017, Mrs Hulbert worked “ordinary time” of 70.59 hours. Assuming that this 14 day period comprises 10 working days of 80 ordinary hours all-up, Mrs Hulbert, as a non-beneficial owner of all of the shares in Providers and a director of Providers is substantially engaged in her employment as a Care Worker for RSL Care. There is no suggestion in any of the evidence that Mrs Hulbert has any experience or qualifications in any of the 12 credit activities recited in the ACL held by Providers.

(5) I am satisfied that notwithstanding Mr Hulbert’s disengagement as a registered shareholder in Providers and as a registered director of that company as and from 11 September 2013, he nevertheless remains engaged at some level in its activities. Plainly enough, Providers has, for all practical purposes, stepped into the shoes of Channic.

(6) CBPL (by Mr Hulbert) lodged with ASIC a request to cancel its ACL with effect from 30 July 2013 on the ground that the licence was “no longer required”. The licence was cancelled by ASIC on and from 31 July 2013: HDC-44 and HDC-45.

(7) Both Channic and CBPL were (when operating) small companies in their scale of operation. Mr Hulbert was the guiding mind of each company. He was the sole shareholder and sole director of each company and the authorised agent for each of them. Mr McKenzie was employed by CBPL as a Loans Adviser: LJ at [1501]; McKenzie affidavit at para 2. There have been two other staff members employed (in all) by either Channic or CBPL: Hulbert principal affidavit at paras 23 and 24.

(8) In the period 13 July 2010 to 25 June 2012 (almost two years), Channic entered into 196 credit contracts. This figure is accepted by the respondents. In the period 1 May 2011 to 31 July 2011, Channic entered into 27 credit contracts: HDC-47, Channic Report, “Loans Issued Over a Given Date Range”. The table below sets out the loans by month, total amount of loans issued and the average loan amount:

Time period | Number of loans issued | Total amount of loans issued | Average loan amount |

May 2011 | 6 | $37,369.00 | $6,228.17 |

June 2011 | 12 | $106,443.00 | $8,870.25 |

July 2011 | 9 | $77,563.00 | $8,618.11 |

Total | 27 | $221,375.00 | $8,199.07 |

(9) The statistics set out in the table at (8) are consistent with the evidence of Mr Hulbert and Mr Humphreys. On a 12 month projection, the number of loans is 108. ASIC contends, and I accept, that during the period relevant to these proceedings Channic was entering into about 100 credit contracts per year. This, no doubt, gives rise to the acceptance by the respondents that over the two year period there were about 196 credit contracts. Assuming an average loan value of $8,199.07, Channic’s business of providing credit by way of credit contracts engaged the provision of loans to the value of $819,907.40 per year across 100 credit contracts. At the lower end of the average loan amount of $6,228.17 (see the May 2011 statistic from the table at (8) of these reasons), the annual loan value amounts to $622,817.00. This range represents the scale of Channic’s business in the relevant period.

(10) As to CBPL, Mr Hulbert operated that company as a way of capturing loan applicants “for Channic” in circumstances where CBPL was not actually engaged in the process of acting as a true broker or assistance provider by seeking out the best market proposal for the relevant consumer. The broking “fee” per transaction was either $500.00 or $550.00 or $990.00. Based on an average fee of $680.00, brokerage fees payable to CBPL would have been $68,000.00 annually on 100 contracts.

(11) As to the position in the market occupied by Channic (and CBPL), the Court noted these matters at [1833], [1836] and [94] in the Liability Judgment:

1833 … Many of these consumers came to Supercheap as, in effect, a place of last resort for the purchase of a motor vehicle. That is not to say that they went to Supercheap because they had been habitually rejected from other purchase transactions at other car yards but rather because the consumers perceived that Supercheap was a place where persons in difficult financial circumstances would be able to purchase a motor vehicle through some kind of purchase arrangement. They had no idea of whether (and were not told about whether), Supercheap would vendor finance the purchase of a car by accepting instalment payments over time or whether there was some kind of related financial “tie-up” by which Supercheap would be able to place a consumer into a purchase arrangement, or otherwise. They knew that they would have to apply for finance. The consumers had no idea of who Channic was (or might be) and no idea of any relationship between Channic and commission payments by Channic to Mr Humphreys.

1836 In these financial circumstances, Supercheap represented, in essence, the only car yard that was able to enable these consumers to purchase a motor vehicle coupled with finance to do so. Some of the consumers were just very pleased to be able to acquire a motor vehicle because they thought they would not be able to do so. The credit contracts were the mechanism by which they were able to acquire a motor vehicle, irrespective of the terms. I am satisfied that all of these considerations taken together made it plain to Channic that these consumers were in a significantly disadvantaged position as compared with Channic when they came to the question of entering into the credit contract.

94 Supercheap took out written advertisements by which it said that finance was offered to buyers: with a 20 minute on-site approval; to persons in receipt of Centrelink income; to persons with bad credit histories; and to ex-bankrupts. Supercheap advertised its business by means of a large sign outside its business premises visible to passers-by as set out below (Applicant’s Tender Bundle, Vol 1, Tab 4):

83 Mr Hulbert says that Channic’s assets are confined to cash at bank of $163.31. He says that for the financial year ending 30 June 2011, Channic suffered a loss of $17,279.00. However, the profit and loss statement (CH-1) for that financial year shows no income received yet contracts were being written in May 2011 and Channic’s ACL was operational from February 2011. Mr Hulbert also says that Channic suffered a loss in the financial year to 30 June 2012 of $85,692.00. The profit and loss statement (CH-2) only shows the expenses line or expenses items in the annexure. Mr Hulbert says that CBPL suffered a loss in the financial year to 30 June 2011 of $576.00; a loss in the financial year to 30 June 2012 of $350.00; and a loss in the financial year to 30 June 2013 of $19,892.00. Again, the attachments to the affidavit (CH-3, CH-4 and CH-5) are entirely inadequate as supporting documents. The attachments in each case are simply one page from a broader document (a tax return in the case of CH-3 and CH-4 and a profit and loss statement in the case of CH-5). The income items are not disclosed in CH-5. The figures are difficult to identity in CH-3 and CH-4.

84 Mr Humphreys gave evidence that of the 10 cars sold per month, eight were the subject of finance applications. If CBPL was the so-called broker engaged on those applications at the rate of 96 per year, its income ought to have ranged annually between $48,000.00 (92 x $500.00) and $95,040.00 (96 x $990.00) or assuming an average fee of $680.00, an amount of $65,280.00. None of the annexures properly explain or demonstrate the income of CBPL or the derivation of CBPL’s income. In those cases where CBPL was engaged, the brokerage fee was financed by Channic and built into the borrower’s credit contract based on a payment by Channic to CBPL of CBPL’s fee invoice.

85 As to Channic, Mr Hulbert says that he intends to cause the company to be wound up on the conclusion of the litigation.

86 As to his own position, Mr Hulbert says that his “taxable income” in the financial year to 30 June 2011 was $30,036.00. Again, the document at CH-8 is only a single page which, in any event, is very difficult to read. Mr Hulbert says that for the financial year ending 30 June 2012, his “taxable income” was $20,113.00. Again, only a single page is produced: CH-9. Mr Hulbert is presently employed by Cash Lenders Pty Ltd (“CLPL”) and receives income of $1,000.00 per week, gross. Mr Hulbert is a co-director of CLPL which was incorporated on 6 February 2013. He holds five of the 200 issued shares. CLPL has assets of $500,000.00. It suffered losses in the financial years ending 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015 although no documents are produced as to those matters. As to Mr Hulbert’s other interests, he is the sole director of a company called Online Trading Pty Ltd (“Online”). He holds all the issued shares. It began trading on 30 May 2015. It has $600.00 cash at bank and has not made a profit since it began trading. Mr Hulbert is a co-director of Lykcol Pty Ltd (“Lykcol”) which was incorporated on 6 February 2013. He holds five of the 220 issued shares. It has a small amount of stock, $1,000.00 cash at bank, a small turnover and no profit has been derived since the start of trading. Mr Hulbert says this at para 49 of his affidavit:

I say that my only income is that received from [CLPL] and that my only other assets are the shares in [CLPL], [Online] and [Lykcol], the total value of which is approximately $10,000 and approximately $2,000 held in a joint bank account with my wife in the Bendigo Bank.

87 Mr Hulbert says that it will be necessary for him to sell his shares in CLPL, Online and Lykcol in order to pay legal costs and tax due to the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”). He says that he also supports his wife, Juisticia and his two daughters now aged 15 and 13.

88 Mr Hulbert suffers from a number of medical conditions. He says this at paras 53 to 56 of his affidavit:

53 I am currently working approximately 30 hours per week but anticipate those hours will be drastically reduced due to my medical condition.

54 I have chronic kidney failure and have recently been fitted with a fistula in preparation for imminent commencement of dialysis.

55 I currently have consultations with [E]ndocrinologist, Dr Lai Wong …

56 I am being treated by Dr Shyam Dheda at the Renal Department at Cairns Base Hospital.

89 Mr Hulbert attaches to his affidavit a report from Dr Dheda dated 17 February 2017. Dr Dheda is a Consultant Nephrologist at the Department of Renal Medicine at the Cairns Base Hospital. Dr Dheda says that Mr Hulbert is suffering from chronic kidney disease and Type 2 Diabetes together with a number of other conditions. Dr Dheda says that Mr Hulbert suffers from “chronic advanced kidney disease” and that although he is not currently requiring dialysis, he will require “this chronic therapy in the future”. Dr Dheda says that in preparation, an artificial blood vessel (fistula) has been created in Mr Hulbert’s arm to enable that to occur. Mr Hulbert also attaches to his affidavit a report from Dr Wong dated 20 February 2017. Dr Wong says that Mr Hulbert suffers from the conditions earlier described but also a condition described as Hyperlipidaemia. Dr Wong also says this:

Over the past year, his kidney function has worsened. He has a forearm fistula and will likely need Haemodialysis at Cairns Base Hospital in the future, which would affect his capacity to work.

90 The essential propositions of the respondents (put by Dr Spence) and particularly Mr Hulbert as the sole shareholder and guiding mind of Channic and CBPL (and on his own behalf) are these.

91 First, Channic has ceased to operate. It has transferred its book to providers and it is soon to be wound up. CBPL has surrendered its ACL and no longer operates as a credit assistance provider. Thus, there is no future conduct or likelihood of any future contravening conduct which would attract any consideration of “specific deterrence”.

92 Second, those corporations have no assets and Channic is to be wound up.

93 Third, Mr Hulbert has no assets of any significance. He has obligations to the ATO and his family. He has no capacity to pay a pecuniary penalty and is very likely within the next few weeks or so, according to Dr Spence on instructions from Mr Hulbert, to cause a trustee to be appointed to his estate under the provisions of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth).

94 Fourth, Mr Hulbert is seriously ill.

95 Fifth, although Mr Hulbert makes no challenge to the reasonableness of the quantum of the costs of the proceedings as set out in Mr Copley’s affidavit of 9 February 2017, Dr Spence says that the imposition of an order to pay lump sum costs of $480,000.00 operates as a “penalty” having regard to Mr Hulbert’s financial position and his ill health.

96 Sixth, Mr Hulbert made some admissions in his pleading and thus showed some degree of co-operation with the Regulator.

97 Seventh, Mr Hulbert’s conduct as the guiding mind of Channic and CBPL (and thus the cause of Channic and CPBL’s conduct of engaging in the contraventions) and his own conduct of being knowingly concerned in the conduct of those two companies, was not “deliberate”. Mr Hulbert did not engage in the conduct, it is said, “knowing” the conduct involved contraventions of obligations cast upon Channic and CBPL under the NCCP Act provisions or that his own conduct involved knowing concern in the particular illegality of the conduct of Channic or CBPL. Rather, the conduct arose, it is said, out of the “relevant state of mind” of Mr Hulbert at the material time. That state of mind is described by Dr Spence (and considered to be so by Mr Hulbert) as (respondents’ written submissions, p 5; oral submissions at T, p 22, lns 10-11):

… one of objective recklessness, the conduct involved in the contraventions having been engaged in without regard to its unlawfulness.

98 Seventh, the scale and extent of the contraventions ought properly be understood as 10 contracts, over the relevant period, out of 196 contracts by companies of very small scale with only a few employees operating out of small scale premises attached to premises for the sale of second-hand cars.

99 Eighth, the damage to the consumers was relatively modest.

100 Ninth, the application of, first, the course of conduct principle and second, the totality principle (taking into account an overall check upon the totality of the contravening conduct) ought to result in a diminished overall pecuniary penalty although no proposition is put by the respondents as to the amount of overall penalty that ought reasonably be imposed in the exercise of the discretion having regard to the factors emphasised by the respondents.

THE IMPOSITION OF A PECUNIARY PENALTY IN RESPECT OF the CONTRAVENTIONS

101 Having regard to all of the considerations described in these reasons, I have reached these conclusions:

(1) First, I accept that Channic no longer operates and is likely to be wound up. I accept that CBPL has ceased to act as a credit assistance provider. I accept that “specific deterrence” has a significantly diminished role to play in discouraging future non-compliance by either of those companies with the relevant provisions of the NCCP Act shown to have been contravened or other provisions of that Act casting other obligations on such participants. However, I do not accept that specific deterrence has no role to play. The community has an interest in the Court recognising and marking its disapproval of the unlawful conduct of the particular participants. Second, the imperative of general deterrence requires the Court to mark its disapproval of the conduct so as to deter non-compliance by others with the normative obligations adopted by the Parliament and contained in the relevant NCCP Act provisions found to have been contravened by Channic and CBPL. Third, Providers has stepped into the shoes of Channic. The imposition of a pecuniary penalty upon Channic (and CBPL) operates to deter Providers (and others) from failing to comply with its normative obligations under the NCCP Act.

(2) I accept that Mr Hulbert is in financial difficulty and that he is chronically ill in the way described by Dr Dheda and Dr Wong. I do not accept that there is little or no role for specific deterrence in the case of Mr Hulbert. First, the Court ought to mark its disapproval of Mr Hulbert’s conduct as described in the Liability Judgment and, to some extent, summarised in these reasons. The conduct represents a total disregard of important normative obligations cast upon Channic and CBPL by the NCCP Act, all designed to protect consumers from entering into “unsuitable” credit contracts with all the financial stress and emotional worry associated with the consequences of having entered into such contracts. Second, I do not accept that Mr Hulbert has no role to play in Providers. The directors are a part-time book-keeper, Ms Bataillard, and Mr Hulbert’s wife who has no background or qualifications in the provision of credit services, or the governance, as a director or otherwise, of the activities of a credit provider. Mrs Hulbert is a qualified care worker. On the other hand, credit contracts are a part of Mr Hulbert’s life experience. Third, matters of specific and general deterrence need to be taken into account in determining the penalty to be imposed upon Mr Hulbert.

(3) I accept that over the two year period 196 contracts were entered into and 10 of them are the subject of these proceedings. Ten credit contracts are the subject matter of a series of contraventions by Channic, CBPL and Mr Hulbert of the identified provisions of the NCCP Act. They are, nevertheless, serious contraventions. Had the contraventions not occurred, the probability is that the consumers identified in the Contracts Schedule would not have entered into contracts “unsuitable” for them.