FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Agius v State of South Australia (No 4) [2017] FCA 361

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA & OTHERS Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 April 2017 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Compliance with paragraph 14 of the Orders made by Justice White on 11 November 2016 be extended to 7 August 2017.

2. The interlocutory applications filed by the applicant on 23 January 2017 and 25 January 2017 be dismissed.

3. The proceeding be adjourned to a case management hearing on 10.15 am on 10 May 2017 in the Adelaide registry.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 On 11 November 2016, White J made a series of orders and directions designed to prepare this matter for trial on a separate question, which his Honour stated in those orders, such trial to commence on 3 April 2018 for a period of six weeks.

2 The separate question stated by his Honour concerned whether the applicant can establish connection to the claim area. The question is:

But for any question of extinguishment of native title and the determination of matters required by s225(c), (d) and (e) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

(a) Does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the Kaurna claim area?

(b) In relation to that part of the Kaurna claim area to which the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(i) Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

(ii) What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interest?

3 The orders of White J represented a substantial step towards the resolution of this application, which was filed almost 17 years ago. It will be necessary to say something about the history of this claim, but to state that it has been on foot for almost 17 years without resolution of any substantive issues in the claim itself demonstrates how necessary his Honour’s orders were.

4 By proposed orders sent to chambers on 24 March 2017, but without a formal application, the applicant has applied to vacate the trial dates and alter the timetable for preparation for trial in a way which would have the trial commencing an entire year later, on 3 April 2019, and for a period of 12 rather than six weeks. I heard that application at a case management hearing on 28 March 2017.

5 The basis for the application revolves around the amount of work the applicant submits is necessary ahead of trial, and the doing of that work, in turn, is said by the applicant to be dependent on the success of a funding application. Implicit in the application is the proposition that without the funding sought, no or very little trial preparation will be undertaken. I consider that implication was plain from the evidence and submissions on the hearing of the application.

6 The active respondents, the State and the Commonwealth, appear to have little confidence the applicant will be ready for trial on 3 April 2018, and – it appears to me – for that reason, were not vociferous in their opposition to the postponement of the trial for another year. That said, both those respondents appeared to me to be confident they could have their own cases prepared for a trial starting on 3 April 2018 provided they were adequately informed of the nature of the case they had to meet.

7 For the reasons that follow, the trial date of 3 April 2018 will not be vacated. Nor will the trial be listed for a period of more than six weeks. One substantive modification will be made to the time for filing expert evidence by the applicant, on the basis of some of the evidence adduced in the application.

8 The applicant will be expected to comply with the timetable set, and together with their legal representatives, to work towards commencement of the trial on the date specified by White J. That includes being expected to work cooperatively and proactively with the other active parties – the State and the Commonwealth – to ensure that matters of fact and law in relation to connection which can be agreed, or not disputed, are thoroughly investigated and maximised.

9 Failure to ensure substantial compliance with the timetable may result in adverse consequences for the applicant, up to and including dismissal of the proceeding.

Key aspects of the history of this proceeding

10 This claim was filed with the Court in October 2000. An amended application was filed in July 2001. When the application was filed the applicant was represented by Dwyer Durack. Dwyer Durack withdrew in September 2002. It appears there was a period where the applicant was unrepresented. In 2004, Johnston Withers were retained by the applicant, but subsequently withdrew in 2009. Since 2009, Campbell Law has represented the applicant.

11 This is the last “capital city” claim not determined under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). The claim area covers the most heavily populated area of the State of South Australia, including the city of Adelaide, extending from south of Rapid Bay to Redhill in the north. The eastern boundary of the claim area includes the Adelaide Hills, Clare Valley and Barossa wine regions, while the western boundaries takes in the coastal region from metropolitan Adelaide to Port Wakefield.

12 It does not appear that any substantive steps were taken in the proceeding, so far as the Court was concerned, between July 2001 and 2004.

13 In 2004, the Court’s records show that a directions hearing was held at which the State informed the Court that it would take 12 months to prepare tenure material going back two generations, although some preliminary tenure material could be available in about three months. Later that year, the State requested the Court not to list the matter for trial as Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) processes were producing positive outcomes.

14 It appears negotiations between the parties about tenure issues, and work by the State on tenure, continued through the second half of 2004 and into 2005. A process for the exchange of sample tenure documents (such as perpetual leases and miscellaneous leases) was agreed, so that the applicant could consider whether to accept the extent of extinguishment suggested by the State. I note this is a claim where on any view there has been large scale total extinguishment.

15 Debate about tenure issues continued well into 2005. The Court’s records show that progress seemed to have stalled until the second half of 2006, when the State filed an affidavit deposing to the amount of time which would be needed to compile evidence of current tenure, historical public map images and pastoral “family trees” (12 to 22 weeks) compared with the time which would be taken to provide full historical tenure evidence (eight to 24 months). As I noted above, in 2004, the State had provided an estimate of 12 months, and it seems two years later the estimate of time had increased, and was still only an estimate as to future work.

16 Mansfield J held a call over of the proceeding in September 2006, and listed the matter for a call over in 2007, noting that submissions about what should occur next should be filed. There was a call over in March 2007, but for the rest of 2007 it appears that, if the parties did anything, it was in the nature of sporadic communications about tenure which remained unresolved. This situation continued into 2008, and into 2009. In September 2008, Mansfield J referred the claim to the National Native Title Tribunal for it to identify those parts of the claim area in which native title rights may be extinguished. The National Native Title Tribunal was to report by early 2009 on these matters.

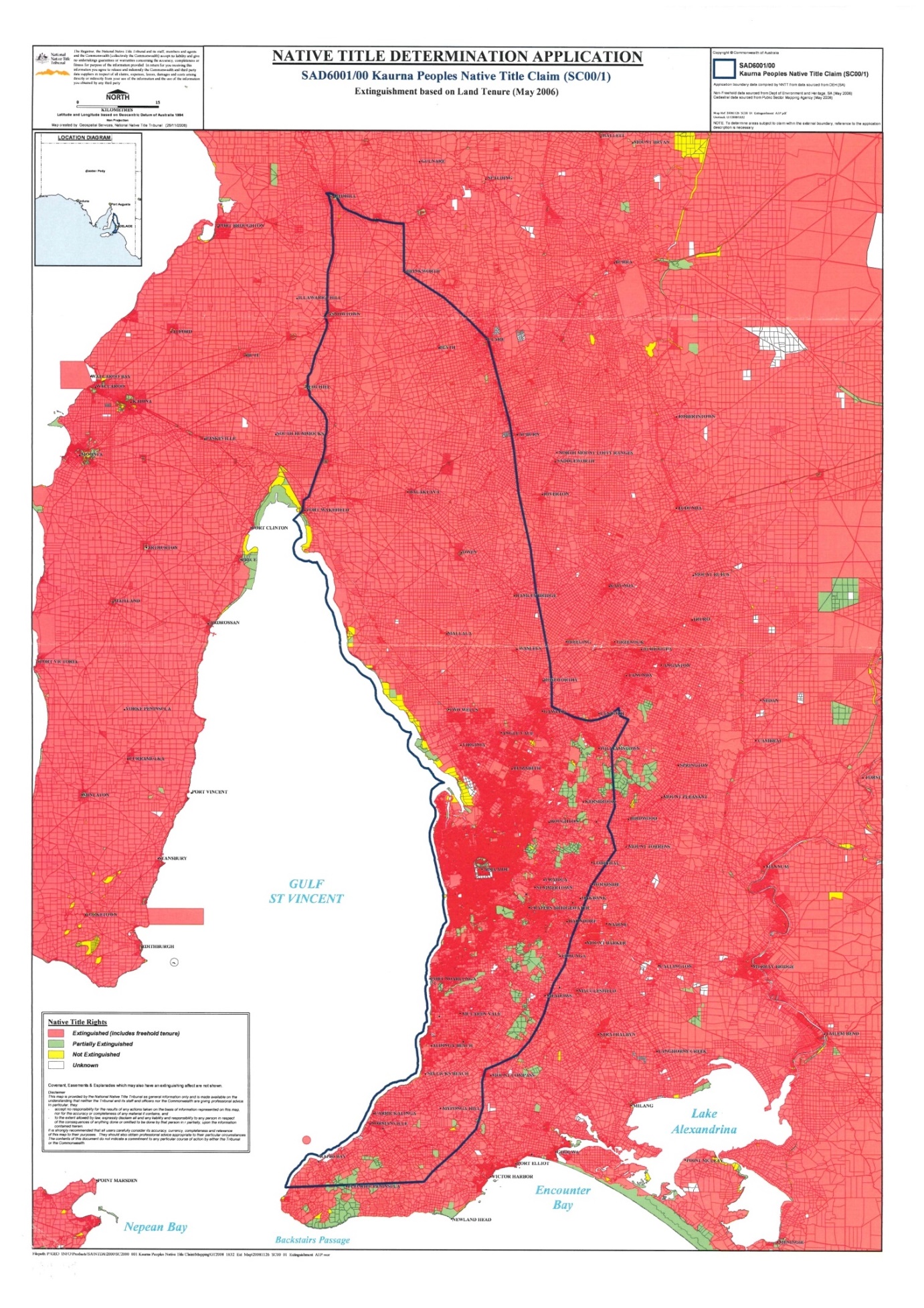

17 In early 2009, as directed, the National Native Title Tribunal reported almost 93% of the claim area was subject to total extinguishment of native title, a little over 3% was partially extinguished, less than 1% was not extinguished and the tenure status of just over 3% of the claim area could not be accurately determined. The scale can be seen on the National Native Title Tribunal map that is Annexure A to these reasons. This report and map are not determinative of the issue of extinguishment, but are certainly indicative.

18 Also in 2009, there were some changes in the operating authority of the Native Title Management Committee elected by the claim group. It would appear that shortly after this event, Mr Tim Campbell of Campbell Law was retained to act for the applicant.

19 On 13 October 2009, the applicant notified the Court of a change of legal representation, and the applicant’s current legal representative, Mr Campbell, became the solicitor on the record from that time.

20 In October 2010, the parties were ordered to file a document setting out the outstanding issues between them and how those issues might best be resolved. In submissions filed in March 2011, the State and the applicant agreed to a pleadings process to clarify issues, and also agreed any outstanding issues on tenure should be referred to the National Native Title Tribunal. By draft minutes of order filed in October 2011, the parties informed the Court they had followed this process “in part” and would progress the matter further once the applicant received funding.

21 I pause in the chronology here to note that this is more than five years ago. It was at that point that the applicant, represented by Mr Campbell, began to tell the Court this matter could not be progressed because of funding.

22 In June 2012, a case management conference was convened to see if the parties could agree on an approach to the tenure aspect of the claim based on the substantial amount of extinguishment. At this case management conference, Mr Campbell informed the Court that the applicant wished to audit the State’s mapping system and sought details of the type of system used and the data relied on. A few months later, a communication to the Court indicated the applicant was seeking funding to engage an expert to assess the State’s tenure mapping system.

23 In October 2012 there was correspondence from the State which appeared to indicate that there would be no further tenure analysis until the applicant secured funding for their proposed investigation into the State’s tenure mapping system.

24 In August 2012, the applicant made an application for preservation evidence on connection to be taken. An affidavit was sworn by Mr Campbell in support of the application. This matter had been raised at the case management conference in June 2012. The applicant sought that preservation evidence be taken from 31 people described as Kaurna elders. Mr Campbell proposed that some of them would give evidence by way of affidavit and some would give evidence orally. He deposed that five days would be necessary to deal with the oral evidence.

25 I infer from the fact of Mr Campbell swearing this affidavit about those 31 witnesses, and applying on behalf of the applicant for evidence to be taken by affidavit, and orally, that he had at this time (August 2012) a reasonable understanding of the evidence those witnesses would give.

26 I note also that on 8 August 2012, Mr Campbell prepared a memorandum on behalf of the applicant, pursuant to the directions of Mansfield J, concerning the position the applicant adopted about the role of water licence holders in the native title claim. In this memorandum Mr Campbell indicated the applicant would not agree that any native title rights in water which were claimed were only non-exclusive, and asserted they would be making claims of exclusive native title rights in water with respect to some bodies of water, as well as indicating a claim of a right to trade resources in water. The memorandum went into some detail about the nature of the applicant’s claimed native title interests in waters within the claim area. Again, this suggests some detailed understanding, and instructions from the applicant, on Mr Campbell’s part about the nature of the claim.

27 The preservation evidence was discussed at a case management conference before a Registrar on 10 September 2012. At this case management conference, Mr Campbell indicated that the number of witnesses from which it was sought to adduce preservation evidence was now seven, rather than 31. Orders were made requiring the filing of further material to support the preservation evidence application.

28 When that material was filed, in a further affidavit affirmed on 25 October 2012, Mr Campbell deposed that preservation evidence was now only sought from five witnesses. It may be the case that some of these elders are now deceased. In case that is the situation, I refrain from reproducing Mr Campbell’s evidence and the names of those elders. Suffice to say Mr Campbell’s evidence disclosed a level of detailed knowledge about those elders, and the kind of evidence they were able to give. I note this was in October 2012, more than four years ago.

29 In October 2012, subject to further confidential affidavits being served, preservation evidence was ordered to be taken from the five claim group members in May 2013. In February 2013, some four months after the order was made, Mr Campbell filed an affidavit deposing to his belief that “[u]rgent funding is required to undertake preservation of evidence for this claim”. He deposed to an application for funding to SANTS in January 2012, an indication from SANTS in August 2012 that the application was unlikely to be approved, and an external funding application to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) would be made by SANTS. He deposed to months of communications, and a lack of response from SANTS. He deposed to being informed in February 2013 that the original application for funding had not been approved and the absence of any further information about an application to FaHCSIA. He deposed to one of the reasons for the funding refusal being that the proceeding was not on the priority list administered by this Court in native title matters.

30 It appears that Mr Campbell’s account of difficulties with funding led to the vacation of the May 2013 preservation evidence hearing dates, and their replacement with dates in July 2013.

31 The applicant was ordered (see orders made 21 February 2013) to provide the State and the Commonwealth, and SANTS, with a list of all anthropological reports in the applicant’s possession, and to provide the actual reports aside from those which were privileged from use in this proceeding. The applicant was also ordered to file summaries of evidence by 1 July 2013.

32 In May 2013, an officer of SANTS (Ms Lucas) filed an affidavit deposing to what had happened about funding. She deposed that FaHCSIA had approved funding in May 2013, but had then told SANTS “funds were not available and SANTS would have to fund the matter out of the existing SANTS budget”. Ms Lucas deposed at [16]-[17] of her affidavit:

16. Order 2.4 seeks material as to whether there are any bars to any funding application being granted by SANTS. SANTS makes the following comments in relation to this order:

(a) SANTS notes that funding will not be available until after 1 July 2013.

(b) SANTS does not fund work undertaken prior to funding approval (retrospective applications).

(c) The actual amount of funding, and the mode of service delivery for the project will be determined in consultation with the instructing solicitor, SANTS’ Principal Legal Officer and Chief Executive Officer.

(d) SANTS will impose conditions on the use of funds prior to funding being approved.

(e) I have been informed and verily believe that those conditions will include, but will not be limited to, the engagement of Mr Andrew Collett as Counsel for the Kaurna people to run the preservation of evidence hearing in this matter.

17. I understand that the hearing is currently listed for 22 July 2013. Should those instructing the Kaurna people feel that the fact that funding will not be finalised prior to 1 July 2013 would mean that an inadequate period of time is available to prepare for the hearing, SANTS supports vacating the proposed date in favour of a later date.

33 Ms Lucas had earlier deposed to the funding arrangements under the Native Title Act, by way of a “Program Funding Agreement” with the Commonwealth government, which is similar to the evidence given by Mr Beckworth before the Court on the current application, in his affidavit affirmed on 28 March 2017 (which I refer to at [72]).

34 The preservation evidence hearing went ahead from 22 to 26 July 2013, with three witnesses.

35 More than a year then went by. Further preservation evidence from another claim group member was taken in September 2014.

36 At the next case management conference in October 2014, discussions appear to have reverted to tenure. The applicant, through Mr Campbell, was still insisting they wished to “audit” the state’s mapping system.

37 The report of listing as sent to the parties records the following:

Mr Campbell advised that he still wished to audit the State’s mapping system and in particular the method adopted by the State. He advised that he had not been able to retain an auditor to carry out this task as he was still awaiting funding for that purpose. The DDR said that had been the position 2 years ago and sought details of what steps had been taken to obtain funding and undertake the audit. Mr Campbell advised that it was not the Court’s role to question him about those steps; that it was the Applicants’ business as to how and when it went about taking those steps.

38 At the next case management hearing in December 2014, Mr Campbell continued to use the proposed “audit” as the explanation for why nothing else had occurred in this proceeding. He then told the Registrar he anticipated having the audit undertaken in April 2015. At this case management hearing, Ms Davis for the Commonwealth informed the Court that the Commonwealth had “almost completed its work on tenure and expected that will be completed after the Christmas period. The Commonwealth intends to provide details of the land in which it is interested to the applicants and the State.”

39 At the February 2015 case management hearing, Mr Campbell informed the Registrar he had not yet appointed an IT consultant and was speaking to a Council about an appropriate person. Ms Davis confirmed the Commonwealth had not yet finalised its list of land in which it is interested.

40 Mansfield J attempted to break the apparent deadlock on tenure by requiring the parties to file a minute of consent orders enabling the National Native Title Tribunal to undertake mapping work concerning tenure. The State raised resource issues, and Mr Campbell continued to ascribe delays to lack of funding. He also informed the Court he had still not appointed any expert to “audit” the State’s mapping system, which he had foreshadowed almost three years ago.

41 The tenure mapping was referred to the National Native Title Tribunal, which engaged in the necessary work and had a portal of the mapping available a few months later. As I note elsewhere in these reasons, the mapping discloses large-scale total extinguishment of native title over the claim area. Mr Campbell said at the case management conference on 30 June 2015 that the applicant accepted that about 98% of the area was extinguished, but nevertheless, he continued to insist the applicant needed funding to conduct an “audit”. The notes of the case management hearing disclose Mr Campbell told the Registrar he would not look at the portal until he received funding. The applicant was ordered to provide to the parties and the Court their position in relation to extinguishment by 1 September 2015.

42 The applicant did not comply with that order. Instead, the applicant filed a memorandum on 2 September 2015, which again sought to defer providing their position in relation to extinguishment until funding was provided for an “audit” of the mapping systems. The memorandum stated:

6. The Applicant’s proposed audit of the tenure mapping systems has not been funded.

7. As a result, the Applicant seeks that the Court convene a Case Management Conference to set a new date for the Applicant to provide the Court and the parties with its position in relation to extinguishment.

43 In March 2016, White J called over the South Australia native title list, including this matter. Mr Campbell continued to agitate about the need for an “audit” of the State’s mapping, but this is the exchange about progress on the connection report:

MR CAMPBELL: Yes, your Honour, but we’ve – in terms of what we think the priority is, is the connection report and tenure will come later. We don’t have funding to look at tenure at this stage.

HIS HONOUR: Why can’t the two go hand in hand? This issue has been sitting there like a sore, it seems to me, for some years now.

MR CAMPBELL: Well, we can apply for funding, your Honour, but it’s more likely I think we will get funding for a connection report if we get funding at all next financial year.

HIS HONOUR: What do you have in mind, that there will be a connection report, maybe that will be resolved in your favour. One would expect it to be resolved in your favour given what we all know as a matter of common knowledge. And what, then you will start looking at this tenure map issue?

MR CAMPBELL: That’s correct, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: So this will all be dealt with seriatim and put it on the long bow, as it were.

MR CAMPBELL: Well - - -

HIS HONOUR: It’s hardly satisfactory, Mr Campbell. You’ve known about this issue for years, it seems to me.

MR CAMPBELL: Well, yes, it’s a very old claim as well, your Honour, but unless there’s funding, this is the – the tenure issue is a major one with this claim of course because of the capital city. So it’s something that is going to – it may take considerable funding but in the meantime there may be a way that it can be done through some kind of audit and some kind of checking that have then - at least we could agree on extinguishment of a number of lots.

44 After a great deal more to-ing and fro-ing in which little detail was provided by Mr Campbell, White J made the following observation, and then moved onto proposals to continue to advance the prosecution of the claim itself:

HIS HONOUR: Right. Mr Campbell, you might have gathered by now that what I’m looking for is some particularity. So there is no point just repeating to me these things at levels of generality. What I am going to do is to make some orders in terms generally of what is set out in paragraph 2. I will come back to some questions about dates in a minute, but I am also going to make orders for you to provide some identification with precision of what it is that you’re concerned about. You’ve had several years, on my understanding, in which to consider whether there is some discrepancy and it’s appropriate that we get to some understanding of what it is that’s involved here so that the State and the Court can have some understanding of where this might go.

Can I come back to paragraph 2? I would like to insert some timelines there. The applicants are to prepare a budget. How long do you need to prepare a budget, Mr Campbell?

MR CAMPBELL; Another 21 days, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: All right. Well, perhaps we will give you to the end of April and I might put in that that is to be submitted by 13 May. SANTS is to, I’m going to make this, determine whether to fund a connection report. How long will SANTS need for that, Mr Beckworth, should I look to you for this?

MR BECKWORTH: Your Honour, we will go through a planning process soon – sorry, once we receive it, by the end of April. May will be our planning process, preparation of the operational plan and putting dollars to applications, your Honour, so perhaps by the end of May.

HIS HONOUR: Well, you may not get it to 13 May on the timetable I’ve got at the minute.

MR BECKWORTH: Yes.

HIS HONOUR: Is end of May still satisfactory?

MR BECKWORTH: That’s fine, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: And that is to determine whether to provide the funding?

MR BECKWORTH: Yes, your Honour, and the level of funding.

HIS HONOUR: Yes.

MR BECKWORTH: It may be that we’re not able to provide the total amount of funding required to produce the report in that financial year. We may have to run it over two financial years.

HIS HONOUR: All right. And then subject to the funding being provided, the applicants will commission the report. When will you have done that by, Mr Campbell?

MR CAMPBELL: Probably by the end of August, your Honour

45 It was on the basis of this discussion that the following orders were made:

1. The Applicants are by 29 April 2016 to prepare a budget for a Native Title Connection report and are by 13 May 2016 to submit that budget to South Australian Native Title Services Ltd.

2. On receipt of the budget provided by the Applicants, South Australian Native Title Services Ltd is by 30 May 2016 to determine whether to fund a connection report in the 2016-2017 Financial Year.

3. Subject to funding being provided to them from South Australian Native Title Services Ltd, the Applicants are by 31 August 2016 to commission a connection report.

4. The State on receipt of the connection report from the Applicants, will consider promptly whether the parties progress the matter to a Consent Determination.

5. The Applicants are by 31 August 2016 to identify to the State and the City of Adelaide with detailed particulars, the aspects of the tenure maps relating to the City of Adelaide provided by the State which they contend are inaccurate.

…

46 I note in particular the order that by 31 August 2016, the applicant was to commission a connection report. That did not occur. By an affidavit affirmed 31 August 2016, Mr Campbell deposed that SANTS provided “only $20,000” in funding for the Kaurna native title application. The email from Mr Beckworth at SANTS annexed to Mr Campbell’s affidavit gives two reasons for that allocation: first, that SANTS itself had received a reduction in funding “compared to last year’s allocation”; and second, that this proceeding was not on the Court’s priority list. The email concluded with Mr Beckworth saying:

Obviously you will need to consider how that level of funding will best be used to advance your clients application.

47 In his affidavit of 31 August 2016, Mr Campbell bluntly stated:

In relation to the orders noted in paragraphs 3(b) and 3(c) above, Campbell Law has not commissioned a connection report as the amount $20,000 is insufficient.

48 While on any view the sum of $20,000 falls short of the sums often expended to secure a “full blown” anthropologist’s report on connection (which are in excess of $100,000), what is notable about Mr Campbell’s evidence is that he relies on the insufficiency of funding as an answer to complete non-compliance with an order of the Court. It is also notable that he does not depose to any alternative plan to do the best he could with the $20,000 to get as far as he could with a connection report. On the view of any reasonable person in the Australian community, the sum of $20,000 is not insignificant. From Mr Campbell’s subsequent evidence, it represents 95 hours of work by an anthropologist.

49 In my opinion, 95 hours of work by an anthropologist could and should have significantly advanced the preparation of a connection report, given the other available material, including genealogies, preservation evidence and information held by Mr Campbell which enabled him initially to inform the Court that 31 witnesses were available for preservation evidence.

50 It is debatable whether the way Mr Campbell elected to spend that $20,000 has brought the connection report any closer to fruition. The election to use a new anthropologist (Mr Maeorg) as well as Dr Draper (who, on the evidence has been working with the Kaurna people on this claim for some time) may have delayed progress. I infer from Mr Campbell’s most recent affidavit that Mr Maeorg may not have been engaged to perform the work that has cost $20,000 until quite recently, and certainly not shortly after 31 August 2016.

51 At a call over in September 2016, White J again pressed Mr Campbell about what steps were being taken to advance the prosecution of this application. Mr Campbell again fell back on the excuse of lack of funding.

52 These are the relevant exchanges:

MR CAMPBELL: To put it in shorthand, with respect to the Crown’s affidavit, your Honour, I think that is a matter of history and if you wish to discuss that I think it more relates to the original order and all I’m – we’re not concerned about the original order. We’re only concerned about the fact that, putting in shorthand, there was a federal election and SANTS funding was – their notification of their funding and then, hence, the notification to us was delayed. So we were unable to carry out your orders, purely because the notification of funding – we now have that and we’re just, in some way, simply asking for further time on the basis that we’ve now got the funding.

HIS HONOUR: Well, Mr Campbell, with all respect, your affidavit doesn’t indicate that it was because of the federal election.

MR CAMPBELL: Well, I was doing that in shorthand, your Honour. Sorry.

HIS HONOUR: Yes.

MR CAMPBELL: Yes.

HIS HONOUR: But, secondly, what it doesn’t do is tell me what you contemplate doing with the 20,000 and how things might be different by 30 November, which is the time to which you seek the extensions.

MR CAMPBELL: Your Honour, we would be spending some of that money on carrying out the amended orders in paragraphs 5 and 6 of your original orders.

HIS HONOUR: But your affidavit doesn’t tell us these things. We shouldn’t have to be trying to tease these things out in this situation. It doesn’t tell me what else your client have done with respect to obtaining funding. It doesn’t tell me whether there’s any – whether you’ve made some assessment of the time you need to take a step and whether that step is going to be completed by 30 November – doesn’t give the court any sorts of assurance, let alone confidence, that something’s going to be different by 30 November. Perhaps instead of pursuing that, Mr Campbell, having these interlocutory applications has led to me looking through the file, and perhaps this might be starting to sound like a mantra from me to some of the parties here, but this is a matter, I notice, that was commenced in 2000. Here we are - - -

MR CAMPBELL: That’s correct, your Honour. Yes.

HIS HONOUR: I think in October 2000. Here we are just on 16 years later and it isn’t easy to identify the progress that has been made, really. There has been a lot of wheel-spinning but not a lot of forward movement, it seems to me, and you’ve been talking about wanting to do something with respect to tenure since at least 2012, yet here we are about four years later – nothing advanced there. It’s just not a situation which I think the court can – just can allow to continue. It’s just not in the public interest. It’s really an affront, really, to the administration of justice.

MR CAMPBELL: I agree entirely, your Honour, and it’s entirely due to the lack of funding. We have done significant pro bono work and we’ve done the preservation of evidence which, obviously, as you would understand, takes greater urgency when we’ve done that, and we’ve still got one contemplated perhaps in the next 12 months.

[Emphasis added.]

HIS HONOUR: I’m alert to the fact that there are other competing demands, but I just don’t think that we can allow this matter just to drift off, and I must say your affidavit didn’t give me any confidence that there was going to be any movement, even if I did grant an extension of time. So I’m wondering whether a different tack might be worthwhile, and that is this: that we explore the possibility of ordering a trial of separate issues or, more colloquially, a two-stage trial. That is we put aside to one side the issue of extinguishment and tenure, which seems to be a concern of yours, and look at other things and identify those as being matters for a first-stage trial – eg, the continuation of connection and maybe there will be other issues which could be conveniently dealt with in a first-stage trial…

But on what I know presently, I query why we couldn’t work towards a trial in this matter in late 2017 or, say, early 2018.

MR CAMPBELL: Well, it’s purely subject to funding, your Honour. There’s a limited amount of pro bono I can do.

HIS HONOUR: Well, there’s a time – there’s a time, Mr Campbell – I understand that, but there comes a time when, after – and I think we might have got to it after 16 years – that - - -

MR CAMPBELL: No, your Honour. I don’t. With respect.

HIS HONOUR: You go on, having interrupted, Mr Campbell.

MR CAMPBELL: Sorry. I don’t, your Honour. This is purely subject to funding.

HIS HONOUR: You don’t what? You don’t what?

MR CAMPBELL: I don’t – of course my clients are concerned that it’s taking 16 years, but it’s quite normal, unfortunately, in South Australia with native title.

HIS HONOUR: What did you say – you started a sentence saying “I don’t” – I’m asking you what that sentence is.

MR CAMPBELL: I don’t agree that it has been purely because of its nature of being filed in 2000 as being out of – of being a lack of – of being something that’s abnormal in this court. That is the nature of it, and I understand and respect the fact that there’s a priority list. We’re not on that priority list; therefore, that helps with the indication to the funding from the Commonwealth and we’ve got very little funding. We’ve had some funding for preservation of evidence, which has been urgent, and that has been before this court in terms of how we would be funded. The applicants rely upon pro bono, predominantly, from me for the last seven years – from my firm, and, your Honour, my instructions are unless we get proper funding we are very, very restricted in the ki[n]d of work we can do.

Now, we have done a lot of work already towards connection but we’re nowhere near ready for a trial, and we were – and we’re still in negotiations on consent of termination, subject to us doing a connection report. Now, that’s a lot of money, which we don’t have, and we’re waiting for that and hopefully be funded in the next financial year. But we’ve got some funding for this year, which we can address with tenure and other matters relating to connection. So, your Honour, it is – I’m being blunt, but that’s the nature of this court in terms of native title. And it’s not good for our clients; they don’t like it because, in the meantime, they see their native title rights being trampled upon, to be quite frank, and there are a lot of issues that we’ve been trying to resolve. We have, I think, about 28 councillors as respondents in terms of native title, and every day there is something that my firm has got to do on a pro bono basis to address native title issues as best we can.

53 It was in response to these remarks by Mr Campbell that White J made the following observations, the first paragraph of which I endorsed in the hearing before me:

HIS HONOUR: Perhaps what you’re getting from me is that I’m not just going to sit and hear just from the bar table generalised assertions about what can and cannot be done without there being some proper evidence that things have been explored. And, Mr Campbell, the other thing is, that strikes me here, is at least there was a time in the legal profession when solicitors took the view, if they were retained in a matter but they were unable to comply with the court’s orders, that they had these choices, I think: (1) would be to tell the client, ‘Unfortunately, I can’t act for you’; (2) is to say, ‘Well, I will continue pro bono’ – it sounds like that’s what you’ve been doing; or (3) to act on some other basis, which involves deferred payment. But it’s not as though the court tolerates a situation where a solicitor says, ‘I don’t have the funds; I’m not going to be complying with court orders.’

MR CAMPBELL: - - - I’m not saying I won’t be complying with the court orders, your Honour. I’m asking for an extension of time.

HIS HONOUR: Yes. - - - Well, I’m addressing at the moment, in particular, an alternative way of doing this and which you seem to reject out of hand. I hadn’t even completed outlining the proposal to you when you started voicing your opposition to it, so perhaps if you’re detecting a bit of judicial resistance, Mr Campbell, it’s because I thought I was being confronted with a closed mind.

MR CAMPBELL: I think you are, your Honour, unfortunately, after such a long time, and it’s not just of the solicitor in front of you or the lawyer in front of you; it’s of the applicants as well. This is a very difficult matter. It’s a capital city claim. It’s a complex matter. It’s the last capital city claim, I think, and it has been going for a long while. In the meantime, we’ve had disenchanted applicants and we’ve had deceased applicants.

HIS HONOUR: All right.

MR CAMPBELL: And we’ve had – obviously, from what I’ve already told you, in terms of the other organisations, there’s lots of matters going on for Kaurna, as you would expect in a capital city, and we are reliant, as I assumed the court would be aware, on SANTS funding only for native title matters.

54 Again, the very clear position Mr Campbell is putting to the Court is that unless and until he and his firm are funded to the extent they consider they should be funded, he will allow the applicant to be in default of Court orders, and indeed will allow the applicant’s obligations, and his own obligations, under s 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) to be virtually ignored.

55 Mr Beckworth for SANTS made the following submissions to White J about what could be done in relation to the connection report:

MR BECKWORTH: Thank you, your Honour. Perhaps I will deal with the second question first. I think our preference with the limited funding that we’ve offered to Mr Campbell is that that was spent on at least the commencement of a connection report. We’ve been concerned for some time that perhaps the cart is before the horse in this case – that we should be concentrating on connection before tenure. As Mr Tonkin said, the State aren’t sure at this stage. We did seek substantially more funding than $20,000 from the Commonwealth for this matter so it was difficult for us to juggle competing priority matters. Obviously, there’s a number of matters we think can be determined in this financial year and Kaurna are not quite there at this stage.

So $20,000 is a start. Connection reports can cost between 100 to 200 – potentially more; I’m not sure in this case what Mr Campbell would be thinking with respect to Dr Draper; but we would see that if the connection report could be started in this financial year it could be finished in the next financial year and provided to the State. That would be our preferred process rather than putting it into a case management process with a trial at the end, unless there were scope there to negotiate that consent determination. Our preference would be to get the money from the Commonwealth and spend it on that process rather than case management conferences and preparation for trial, which is often different type of work than the consent determination process, so - - -

HIS HONOUR: The reason I would like to pursue the possibility of setting in place a timetable is just to give this thing some focus.

MR BECKWORTH: Appreciate that, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: Experience tells us that when people know what the timelines are they work to them and it gives a bit more focus to activity, not just in this area but in most other areas of litigation as well.

56 Also ahead of this hearing, Ms Hoffman for the State deposed in an affidavit to the lack of progress made on the tenure aspects of the March 2016 orders, and re-iterated the lengthy history of this issue, without much real progress.

57 On 7 November 2016, and no doubt in response to some of the observations by White J at the September 2016 case management hearing, Mr Rodney O’Brien, one of the individuals who constitute the applicant in this proceeding, affirmed an affidavit about funding. He deposed to the existence of the Kaurna Yerta Aboriginal Corporation (KYAC), and to it acting as “agent” for the applicant. In evidence before me, Mr Campbell clarified this meant all decisions for the applicant in this proceeding were made through that corporation. How this sits with the obligations of those individuals who constitute the applicant under s 61 and s 62A of the Native Title Act is somewhat unclear, especially since two of the directors of the KYAC are not persons who constitute the applicant.

58 Mr O’Brien deposed:

KYAC receives no funding for any of its activities other than small amounts for specific expenses. The aims and objectives of KYAC under its Rule Book relate specifically to Native Title and generally to benefiting the Kaurna Nation.

KYAC has no money with which to fund the preparation for and trial of this Application.

The Applicants are either in receipt of income from Government pensions or from wages from employment and have no money with which to fund the preparation for and trial of this Application.

I believe that there are no alternative sources of income

59 As I outline below, the circumstances of KYAC were described by Mr Campbell in his evidence on the current application. I note also the assumption inherent in Mr O’Brien’s evidence is that no individual members of the claim group, even if employed, should have to pay for, or even contribute towards, their legal representation. I accept that may sometimes be an expectation in native title matters, but in my opinion it is worth at least noting, because of how different that position is from ordinary litigants in this Court, also often litigating matters of intense personal importance to them.

60 On 9 November 2016, and two days before the next case management hearing scheduled by White J, Mr Campbell filed another affidavit.

61 It is at this point that I note that, had the time, energy and resources which have been put into affidavits in this proceeding been put into the production of a connection report and witness statements, it seems to me there is a real likelihood the case (including any negotiations for consent determination) may have been much further advanced.

62 Mr Campbell deposed:

On 12 October 2016, Campbell Law wrote four letters seeking funding for the Kaurna Native Title Claim. The letters were to:

(a) the Honourable John Rau, Attorney General for South Australia;

(b) the Honourable Kyam Maher, South Australian Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation;

(c) the Honourable George Brandis QC, Attorney General for Australia; and

(d) the Honourable Nigel Scullion, Federal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs.

63 Mr Campbell deposed that he had received a response only from Mr Rau, and annexed that response. Mr Rau informed Mr Campbell that:

As you are aware, native title claims are brought under the Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993 and it is the Commonwealth's acknowledged responsibility to fund claims under its regime.

Funding provided by the Commonwealth Government is ordinarily channelled through South Australian Native Title Services (‘SANTS’) for distribution to native title parties. The matter of insufficient funding should be raised with SANTS in the first instance and, if no additional funding is forthcoming, with the relevant agency in the Commonwealth.

64 Mr Campbell also deposed that he would make an application to SANTS for further funding. In oral submissions to White J, Mr Campbell said that he would be seeking litigation funding from SANTS from 1 July 2017. Mr Campbell relied on this as a reason to oppose the listing of a connection hearing:

…the timing issue that we contend will be much later than the – some of the other – I think at least the first respondent is suggesting as to when work could start. And that’s totally due to funding. And we will be making – as I’ve deposed, we will be making an application as soon as we can to SANTS for litigation funding from 1 July 2017. We will make that application this year. And the Commonwealth, it’s my understanding, will consider that in terms of any orders made today.

65 Incredibly, to any person who has followed to this point the key aspects of the chronology which I have set out since 2000, Mr Campbell then foreshadowed a wholesale and extensive discovery application against the State, the Commonwealth and a large number of local councils.

66 On the trial timetable issue, White J inquired of Mr Campbell whether the applicant had alternative sources of funding, such as income from heritage activities. After protesting at length about the irrelevance of such inquiries, and his lack of knowledge about the availability of any funds payable to members of the claim group under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 (SA) in any event, Mr Campbell referred to a corporation he described as Kaurna Cultural Services Proprietary Limited. He told White J, from the bar table, that he used to act for that company, prior to it being placed in liquidation. He stated:

That [i.e. Kaurna Cultural Services Proprietary Limited] certainly had contracts with, I think, certain ministers and certain organisations. My understanding is that Kaurna Cultural Services Proprietary Limited went into liquidation, and they certainly received funds due to activities of monitors being charged for various projects, such as Seaford Rail.

67 White J made the purposes of his inquiries clear to Mr Campbell:

HIS HONOUR: Well, pretty simple, really, I think: you’re telling me you don’t have the financial means to progress the claim. You’re asking me to put in place an extended timetable because of that inability. I’m querying with you whether there might be alternative sources of funding. That is the relevance.

68 The following exchange on the applicant’s proposed timetable occurred, including his Honour repeating some of the difficult choices he had confronted Mr Campbell with eight months earlier in March 2016:

HIS HONOUR: Why do – just looking at the timetable, why do you need until 1 December 2017 to file a statement of facts, issues and contentions?

MR CAMPBELL: That would be about five months after the funding was received, your Honour. We would need that kind of time to determine the issues.

HIS HONOUR: But you’re acting in the meantime.

MR CAMPBELL: Yes. With very limited funding, your Honour. So they wouldn’t be – yes.

HIS HONOUR: But, Mr Campbell, you and I seem to have these disconnects. It was the case when I was in practice, and I think it is still the practice – I know it is still the practice that when a solicitor accepts instructions in a matter the solicitor accepts certain professional responsibilities. And as long as the solicitor is on the record the solicitor has to discharge those responsibilities. It’s not open to a solicitor to say, well, I’ve accepted instructions, but I’m not going to do anything to progress the matter, because I haven’t been funded. As I said to you on the last occasion, the solicitor probably has three choices. There’s three that occur to me anyway. There might be more, for all I know. One of which is to decline the retainer and to terminate it. Another is to do it pro bono. Another is to do it on the basis of deferred payment of one form or another. But it isn’t – one of them – alternatives isn’t I will do nothing when the matter is in active case management. So it’s not helpful for you to tell me I’m awaiting funding.

MR CAMPBELL: I have - - -

HIS HONOUR: Because that makes me ask, well, what are you doing acting for the applicant then if you’re not going to do the things that are of an ordinary kind that are expected.

MR CAMPBELL: Your Honour, I suppose - - -

HIS HONOUR: So it – coming back to my question before, which was why you would need one – to 1 December to file a statement of facts, issues and contentions – you really could do that by 30 March, could you, in terms of doing the work that’s necessary to prepare such a statement?

MR CAMPBELL: Possibly, your Honour. I can’t commit to that, but possibly, subject to instructions.

69 As it turned out, the applicant did file a document on 30 March 2017 which purported to comply with the Court’s order that the applicant file a statement of facts, issue and contentions. I return to that document below.

70 At this directions hearing, Mr Campbell was seeking a timetable that would have the question of connection go to trial in the first half of 2019. That proposal was rejected by White J. Instead, his Honour fixed this matter for trial on connection by way of a separate question, as I have set out above.

71 In early March 2017, this proceeding was transferred into my docket. I listed the matter for a case management hearing on 28 March 2017 in order to ensure the parties were progressing in their compliance with White J’s orders. Ahead of the case management hearing, and upon reading the transcript of the hearing before White J on 11 November 2016, I made the following directions:

1. On or before 11 am on 28 March 2017, Ms Davis, solicitor for the Commonwealth, is to file and serve an affidavit deposing to the steps which have been taken to draw the Commonwealth’s attention to the funding issues raised by the applicant in this proceeding, as foreshadowed by Ms Davis to Justice White on 11 November 2016, including any responses by or on behalf of the Commonwealth.

2. On or before 11 am on 28 March 2017, Mr Campbell, solicitor for the applicant, is to file and serve an affidavit deposing to the steps which he has taken since 11 November 2016 to secure further funding for the applicant in relation to preparation for the trial fixed to commence on 3 April 2018, including:

(a) Steps to secure funding for legal representations;

(b) Steps to secure funding for expert witnesses in relation to connection;

(c) Steps to secure funding for preparation of lay connection evidence; and

(d) The provision of the transcript of the 11 November 2016 directions hearing to the Commonwealth.

3. On or before 11 am on 28 March 2017, South Australia Native Title Services (SANTS) is to file and serve an affidavit deposing to the work it has undertaken since 11 November 2016 with the applicant in relation to their application for funding, and any steps taken by SANTS since 11 November 2016 to secure extra funding from the Commonwealth for the trial preparation of the applicant’s case for trial as set out in the Court’s directions made on 11 November 2016.

4. The proceeding is to be placed forthwith on the priority list of native title applications in the South Australia District Registry, on the basis that it is listed for the trial of a separate question on connection, commencing on 3 April 2018 for a period of 6 weeks.

Evidence on the application

72 The following affidavits were filed:

Affidavit of Mr Tim Campbell, affirmed on 27 March 2017 deposing to the type and amount of funding required for the applicant, including the need for expert anthropologist and historian reports, the hours of work said by Mr Campbell to be required, and the responses received in relation to the various funding requests. In particular, Mr Campbell deposed, at [34]:

The Application for Special Funding is for the sum of $3,818,272.00. The Application for Special Funding identifies that the following is required in order to prepare the claim for hearing:

(a) Interviewing 80 witnesses by an anthropologist and a lawyer and preparing witness statements will require four days per witness amounting to 320 days;

(b) An expert report by an historian will require 30 hours a week for 50 weeks;

(c) An expert report by an anthropologist will require 30 hours a week for 50 weeks;

(d) A Genealogy report will take 70 days by an anthropologist. There is a genealogy available which was prepared by Neale Draper in 2001 and updated in 2010. I am told by law clerk, Wendy Jollands, that she has installed and looked at the genealogy records on the Campbell Law computer system. She has told me and I verily believe that the genealogy records refer to some 4500 individual records (living and dead). There are 1162 families' records, with 452 unique surnames.

(e) A review of documentary sources will require at least one year of full time work by a lawyer and 6 months of full time work by a law clerk;

(f) Preparation for trial will require 24 weeks;

(g) A trial of 12 weeks (rather than the 6 weeks presently estimated)

Affidavit of Mr Jeffrey Newchurch, a Kaurna elder and the Chair of the Kaurna Nation Cultural Heritage Association Incorporated (KNCHA), sworn on 27 March 2017, deposing to the funding (or lack thereof) available to the applicant;

Affidavit of Ms Sally Davis, an Australian Government Solicitor lawyer representing the Commonwealth, affirmed on 28 March 2017, deposing to the status of any funding application submitted to the Commonwealth. In particular, Ms Davis’ affidavit exhibited correspondence from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) that no funding application had been received by that Department from SANTS in respect of this proceeding;

Affidavit of Mr Andrew Beckworth, the principal legal officer employed by SANTS, affirmed on 28 March 2017, deposing to SANTS’ funding arrangements, and deposing that SANTS received a funding application from Campbell Law on 14 March 2017; and

Affidavit of Mr Nicholas Llewellyn-Jones, the solicitor representing a number of councils in this proceeding, sworn on 28 March 2017, deposing to the proposed procedure for resolving the discovery application. I return to the discovery application later in these reasons.

73 Mr Newchurch’s affidavit deposes:

KNCHA has approximately $25,000 due to it from both its previous solicitors’ trust account and invoices due for consulting services.

KNCHA receives some income from consulting and a limited fee (being 10%) of money received for monitoring of Kaurna sites. The Kaurna cultural monitors are employed by a labour hire company. Their casual rates of pay are set by SA Attorney-General guidelines.

The above funds will be used for the following purposes: board expenses, board member consultation payments, administration costs, contributions to Kaurna funeral expenses, travel expenses, and legal fees for Kaurna heritage matters.

74 He goes on to offer the opinion that the Commonwealth government should pay for the legal costs of the claim.

75 In some ways, Mr Newchurch’s evidence raises more questions than it answers. The association which he chairs is not the corporation which Mr Campbell described to White J. Nor is it the same entity as that covered by Mr O’Brien’s affidavit in November 2016. The relationship (if any) between the three entities is unexplained. In any event, the income of the KNCHA is undisclosed. Why it is the case that “board expenses” and “consultation payments” should be prioritised over the advancement of the native title claim (on which the heritage work depends, in the sense that it is the claim which, at least in part, gives Kaurna people the entitlement to be consulted) is unexplained, and unjustified. The amounts received by Kaurna people (I infer, members of the claim group) as “cultural monitors” under the South Australian heritage legislation, are undisclosed.

76 It would seem to be, for example, that some kind of substantial advance could have been made towards payment of the cost of an anthropological report by some form of contribution from members of the claim group through the cultural heritage activities, if no other funding were available, or not available at that time. I am not satisfied the evidence adduced to this point suggests this was impossible. Rather, it appears never to have been considered, or suggested.

77 As I have noted, Mr Campbell’s affidavit dealt with the funding estimates and the amount of work he proposed to do ahead of the trial in more detail. Not only was the funding request very large (over $3.8 million) but the witness estimates were far in excess of previous indications. The estimates for the anthropology work were far in excess of previous estimates (see [145] below) and appear to take no account of work already done. In order to gain a better understanding of his evidence, and given counsel appearing for the applicant had only recently come into the proceeding and informed the Court he could not assist with further detail by way of instructions, I asked Mr Campbell to clarify a number of issues by giving further evidence orally. He did so, and a number of matters were clarified through his evidence. I refer to them where necessary below.

78 Mr Campbell deposed, in his most recent affidavit, to the remaining three responses he received in relation to his inquiries last year before the November directions hearing. From the Commonwealth Legal Assistance Branch, in answer to his letter to Senator Brandis, Mr Campbell was told he had referred to funds available to respondents, not applicants, and for applicant funding he should contact PM&C. From the State Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation, which portfolio covers the Department of State Development, he was told there was no funding available through that Department. The letter referred to the $20,000 given to the applicant by SANTS. From the office of the federal Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Senator Scullion, Mr Campbell was informed as follows:

As a matter of longstanding policy, the Department does not provide funding for individual native title matters in areas where a native title representative body (NTRB) or native title service provider (NTSP), such as South Australia Native Title Services (SANTS), is operating. ·

In your letter you note SANTS is currently providing assistance for this claim. If SANTS subsequently decides not to provide assistance, your clients may apply to the Secretary for a review of that decision under s 203FB of the Native Title Act 1993 (provided they have first sought an internal review of SANTS’ decision). Depending on the outcome of any such review, funding may be made available under s 203FE(2) of the Act.

79 The references to internal review indicate the bureaucratic structures applicable to these funding decisions and why funding applications need to be reasonable and objectively justifiable, and then pursued with alacrity and tenacity, not left to limp along for years.

80 Not for the last time in these reasons, I will emphasise that what is being dealt with here are public funds, on all sides. Public funds are being employed by the State and the Commonwealth to advance their positions in this litigation. Those funds have now been spent over a period of 17 years and often responding to unfocused and marginally relevant demands and requests. Public funds are being expended by this Court in what the summary above demonstrates has been persistent attempts to have the parties confront the realities of this proceeding and deal with them in a measured and efficient way. Those public funds have been expended over 17 years without, until perhaps a year ago, being able to bring the parties any closer to a resolution of this proceeding – not for lack of effort, but for lack of proactive and responsible approaches by the applicant in particular. Public funds (at least as to preservation evidence and anthropology), of an amount presently unknown to the Court, have been allocated to the applicant. The total public resources already expended on this case are enormous.

81 After the hearing, as she foreshadowed she would, Ms Davis sought and communicated her instructions from PM&C about how long it would take for a funding decision to be made after SANTS’ recommendation was received.

82 A commendably efficient process was foreshadowed, with PM&C suggesting a period in the order of 10 days would be required, which could be expedited if needed.

83 Thus, the primary decision-making on funding should be known to the applicant by the end of April or the start of May 2017.

reasons for refusing the application

84 Determining where to draw lines in case management processes is not an exact science. The overarching purpose in s 37M(1) of the Federal Court Act is the facilitation of the just resolution of disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively, and efficiently as possible. The phrase “just resolution” does not appear alone, but rather in the context of the legislatively mandated attributes of quickness, inexpensiveness and efficiency. The focus on the prudent use of the tremendous public resources involved in running a court system is apparent. The Court must “facilitate” the achievement of that purpose through its case management, and its exercises of power and discretion under the Act and the Rules. As Edelman J pointed out in Hart v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2016] FCA 250 at [6], timeliness is an important aspect of this objective, as is the “efficient use of the judicial and administrative resources available for the purposes of the Court”, this being a consideration emphasised by French CJ in Aon Risk Services Australia Ltd v Australian National University [2009] HCA 27; 239 CLR 175 at [5]. Aon was a case about an adjournment. Effectively, that is the nature of the current application.

85 The Court must do its best to reach a conclusion that is consistent with the overarching objective in s 37M of the Federal Court Act, while ensuring the active parties have a reasonable opportunity to present their respective cases. The latter requirement is not co-extensive with any party’s insistence that it should be able to present a case whatever way a party chooses, and on the timetable the party wishes. If the resources of the civil justice system ever permitted or encouraged this approach (which I doubt), they certainly do not do so now.

86 Existing authorities in the native title jurisdiction of this Court about the interrelationship between case management, judicial power and assertions of lack of funding, tend firmly against the application to delay the trial.

87 In Levinge & Ors v Queensland [2012] FCA 1321; 208 FCR 98, Reeves J said (at [18]-[19]):

The application to vacate the June 2013 trial dates was unsuccessful. That should not have come as a surprise to the applicant because this Court has generally been reluctant to accept a lack of funding, or representation by a party, as a sufficient reason to delay a trial of native title proceedings: see, for example, the observations of the Full Court in Bennell v State of Western Australia [2004] FCAFC 338 at [37]. There is a variety of reasons why this is so. One reason is that native title proceedings do not pertain to funding, or the independent financial affairs of the parties involved in them: see Sambo v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2010] FCA 927 at [47] per McKerracher J and Atkinson v Minister for Lands (NSW) [2010] FCA 1073 at [25] per Jagot J. Another reason is that the Court cannot allow the policies of the Executive Government in relation to the allocation of funding for native title claims to paralyse its processes once its jurisdiction has been properly invoked: see Kokatha Native Title Claim v South Australia [2006] FCA 838 at [10] per Finn J.

If a failure to garner public funding for a claim provides no justification for delaying it, there is all the more reason why a lack of private funding should be rejected as a justification. If that were not so, the management of any litigation so affected would become dependent upon the individual choices made by a particular party in the allocation of its private financial resources. Thus, the Court would lose control over the management of the litigation and its future progress would, instead, be determined by the idiosyncratic choices of a particular party, decisions which obviously could not be the subject of any effective review by the Court. Furthermore, in that state, the litigation could be delayed for long periods, perhaps indefinitely, while the particular party’s financial position waxed and waned. If that party happened to be the moving party before the Court, the potential for injustice to any responding party is obvious. It could mean that a respondent party could be forced before the Court and then locked into litigation indefinitely with all the uncertainty, stress and financial pressure that litigation often causes. Of course, none of these observations should be taken to suggest that the Court will not take into account sudden or unexpected events that affect a party’s ability to progress a piece of litigation, or a reasonable request for more time to undertake a step in litigation arising from pressure of work, illness, or other similar causes. However, while such requests are common place in native title litigation, allowances are still generally treated as the exception, rather than the rule.

88 I respectfully agree with Reeves J’s observations. I also note the statement of Finn J in Kokatha at [10]:

Thirdly, the funding issue is one common to all of the present claimant groups. At earlier directions hearings in this matter I have indicated my view that a lack of funding cannot be relied upon to freeze proceedings otherwise appropriate for and requiring resolution. I have equally expressed my regret at the misfortune faced by applicants because of the funding arrangements being as they are. Whatever the justifications for the policies of the Executive Government in relation to funding native title claims, those policies cannot paralyse the processes of the Court once its jurisdiction has been invoked. In saying this I am not unmindful that claimant groups may well find themselves in a position of utmost difficulty in preparing for trial and that this may well jeopardise their prospects of proceeding in any event. While the Arabunna contend they will be prejudiced by having to prepare for a trial one year hence, I do not consider their position in this respect to be materially different from that of the other two claimant groups.

89 Two of the authorities to which Reeves J referred bear further examination.

90 Atkinson was a case in which Jagot J made self-executing orders which would have had the result of the native title claim being dismissed if the applicant did not comply with trial preparation orders: namely, orders that an amended native title determination application and all material on which the applicant sought to rely in relation to all issues in the proceedings other than extinguishment. The dismissal application was made by the NSW Minister for Lands, who was a respondent to both proceedings, and was made under s 94C of the Native Title Act. Thus, the basis for Jagot J’s decision was different to the circumstances of the Kaurna proceedings. Nevertheless, in my opinion the observations made by Jagot J in accepting the Minister’s arguments and making self-executing orders have relevance to the current proceedings, because in Atkinson the applicants were also relying on funding difficulties as the explanation for why no steps had been taken in compliance with a series of court orders designed to move the Atkinson proceedings towards resolution on connection.

91 The claim in Atkinson had been commenced in 2002, with directions made in March 2005 by Wilcox J that the applicants file and serve expert and lay witness statements and other necessary material by 23 September 2005. The applicants did not comply with those directions, nor with another similar set of directions made by Madgwick J in July 2006, with time being progressively extended on those directions to July 2008. By then, the proceedings were in the docket of Moore J, and his Honour made another set of directions with filing dates in November 2008. Again the applicants did not comply. The Minister accepted the applicants had done their best in attempting to secure funding for legal representation, which on her Honour’s reasons began in earnest in 2009. At [11] to [22] her Honour traced the attempts to secure finding, including a review application to the Secretary of FaHCSIA for a review of the decision of the NTSCORP’s Board in accordance with s 203FB of the Native Title Act.

92 At [24]-[25], Jagot J said:

The applicants’ references to them being punished for diligently pursuing their funding application are misconceived. The Minister’s notices of motion have nothing to do with punishment of the applicants. They represent an attempt by the Minister to ensure that matters before the Court are capable of being progressed, heard and determined in a reasonably orderly and expeditious manner.

The diligence of the applicants in pursuing their funding application is also not to the point. These proceedings are not about funding. These proceedings concern the applicants’ substantive claims for native title over the subject land. The applicants, having been permitted to exhaust every opportunity to obtain funding to support the making of their claims, either are or are not in a position to prosecute those claims in these proceedings. If, as the history of the proceedings suggest, the applicants are not able to do so, then it is contrary to the interest [of] justice to permit the proceedings to consume yet more time and resources with no real end in sight.

93 Her Honour then set out the Minister’s contentions, and her own conclusions (at [26]-[27])

As the Minister submitted:

despite the delivery of material from time to time, the applicants have never been able to file and serve all evidence on which they wish to rely to substantiate the claimed native title rights, despite Court orders being made that they do so from March 2005 onwards;

recent amendments to the Native Title Act disclose the legislature’s intention that, in common with all other applicants, applicants claiming native title rights have a responsibility to advance and resolve claims they have instituted;

the applicants’ continuing failure to comply with Court orders, irrespective of the cause being an inability rather than an unwillingness to do so, involves unreasonable delay prejudicing not only the respondents, but also the due administration of justice; and

no permanent prejudice would be caused to the applicants. Summary dismissal of the proceedings for the applicants’ failure to prosecute their claim would not give rise to any estoppel in subsequent properly constituted and diligently prosecuted proceedings.

The applicants’ arguments to the contrary are not sound. I have dealt with the issues of discretion above. In short, given the history of these proceedings, all material discretionary factors weigh in the Minister’s favour. Otherwise there is no ‘compelling reason’ not to dismiss the applications within the meaning of s 94C(3) of the Native Title Act. The issues that the applicants are unable to resolve relating to the proper claim group, due to lack of funding to investigate the matter fully, is not a ‘compelling reason’ not to dismiss the applications. To the contrary, the history of the proceedings suggests that the applicants have exhausted their attempts to obtain funding on the merits of their applications. They are left at present with the mere possibility of judicial review proceedings to challenge the validity – not the merits – of FHCSIA’s funding decision. There is no basis to speculate that any different decision on the merits of the funding request will be made at any time in the future. On the applicants’ own submissions, the unresolved issues about their claim will remain unresolved without funding. As the prospect of obtaining funding is now purely speculative, the unresolved issues cannot be a reason, let alone a compelling reason, not to dismiss the applications.

94 Her Honour’s observations about the uncertainties of future funding are relevant to the current proceeding, as is her Honour’s general observation about the inappropriateness of the Court basing its exercises of power, including discretionary power, on the status of parties’ public funding.

95 Bennell v Western Australia [2004] FCAFC 338 is a decision of a Full Court of this Court, and included the capital city claim over Perth, although the decision covered 13 claims managed together and described as the “south west regional” native title determination applications. The various claims were being managed by Wilcox ACJ, French and Finn JJ as single judges and their Honours sat as a full court to determine how the various claims, which had been the subject of delay (as I set out below) should go forward in terms of case management.

96 Many of the Noongar claims were commenced in 1998, and were consolidated in 2003. Wilcox J had made orders in July 2004 in the consolidated claim (the “Single Noongar claim”) that expert material be filed by 30 November 2004. The Full Court had affidavit evidence from a historian that the timetable for him to produce his expert report was “extremely concentrated”, having been engaged in May 2004 and as a result his full report would not be ready until January 2005.

97 I pause here to note that the time given to this expert, from engagement to delivery, was six months. Wilcox J’s orders were made in July 2004 – a period of only four months from the deadline for filing. The Kaurna applicant in this proceeding, even if an anthropologist and historian began work only after White J’s directions in November 2016, was given eight months.

98 The evidence on funding was of the same nature as the evidence in this application. That is, the native title representative body (there, South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (SWALSC)) received federal funding via annual agreements, subject to an operational plan, taking into account the native title priority list and other decision-making criteria between claims, with the ability to apply for special funding from the Commonwealth for litigated matters. At [18]-[20] the Full Court set out the exchanges between SWALSC and the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, responsible for the administration of Commonwealth funding of native title applications, which correspondence made it clear any funding was far from certain. The Full Court observed (at [21]) that:

the application for special funding was made very late in the day having regard to the fact that the directions for the hearing of the Perth Metropolitan area claim, which now comprises part of the Single Noongar Claim No 1, were given in July 2004.

99 What the Full Court meant, on the facts, by “very late in the day” was that SWALSC made the application in September 2004. In my opinion, a comparison with Mr Campbell’s funding application approximately three weeks ago, in mid-March 2017, after directions in November 2016, would mean one could describe Mr Campbell’s funding application as extraordinarily late in the day.

100 The Full Court recorded (at [24]) an express submission by SWALSC to the following effect:

If the Perth Metropolitan portion were to proceed to hearing in April 2005 the applicants would be unrepresented as the SWALSC does not have funding or permission from its funding body to represent the applicants in contested litigation.

101 Mr Billington made a similar submission, somewhat in terrorem it seemed to me, in this proceeding. The Full Court in Bennell did not consider such a prospect itself mandated accepting the delays urged by the applicant party, and neither do I.

102 At [34] to [38], after reciting the history of the matter, including the prolonged process of funding applications, the Full Court said:

There is much force in the submission by the State of Western Australia that there has been undue delay in progressing any part of the South West claims to trial and that the Court should not contemplate any further delay in the trial of the Perth Metropolitan part of the land and waters covered by the Single Noongar claim. The difficulties in providing funding asserted by the SWALSC seem, at least to some extent, to be of its own making. Its application for funding this year related to the funding of mediation and although the trial of the Perth Metropolitan area claim was the subject of directions made on 21 July 2004, no application for funding was initiated with the Commonwealth until 30 September. Even then, it elicited a response which required it to address specific conditions for the grant of funds for litigation. Presumably, the SWALSC has, since the RCMC, progressed that application. If it has not, then it should do so immediately.

Counsel for the State made clear that the State’s submission that the Perth Metropolitan area hearing continue did not involve a rigid commitment to the April 2005 dates the subject of directions by Wilcox J which are currently in force. A hearing in May or June would meet the State’s concerns.

There are practical imperatives which weigh in favour of a trial in the earlier part of the second half of next year. In particular, the time that will necessarily be taken in responding to Dr Host’s report which will now not be available until 21 January 2005. In so saying it may be acknowledged, as the State pointed out, that the report of the anthropologist Dr Palmer is likely to prove of greater importance to the case than the historical material.

It is important to make the general point that the programming of native title matters in the Court’s docket cannot be determined by the decisions of funding agencies or the views of representative bodies, the State or any other parties about appropriate priorities. These are all matters to be taken into account in setting realistic timeframes. But if it should happen that want of funding means that some applicants will be unrepresented at trial that is not a bar to proceeding with a trial although it will raise obvious difficulties in the management of the trial process.

Overall we have formed the view that it is in the interests of justice that the hearing of the Perth Metropolitan area claim should proceed early in the second half of next year at a date to be fixed. The SWALSC should, if it has not already done so, apply for litigation funding as soon as practicable.

[Emphasis added.]