FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals v Samsung Bioepis AU Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 285

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[13] | |

[13] | |

[28] | |

[35] | |

[38] | |

[41] | |

[47] | |

[57] | |

[57] | |

[58] | |

[59] | |

[67] | |

[73] | |

[98] | |

[129] | |

[133] | |

[146] | |

[157] | |

[167] | |

[172] | |

[177] |

BURLEY J:

1 Etanercept is the active ingredient in ENBREL, which is a biological medicine used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. It is manufactured by the first prospective applicant, Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals. ENBREL has been commercially available since 1998 in the United States of America, since 2000 in the European Union and since 2003 in Australia. The third prospective applicant, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd has since 2003 been the sponsor on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) of etanercept for the products marketed under the name ENBREL. Until recently, ENBREL has been the only product containing etanercept registered on the ARTG.

2 In July 2016 two pharmaceutical products containing etanercept as their active ingredient were registered on the ARTG under the name BRENZYS. The prospective respondent, Samsung Bioepis AU Pty Ltd (SBA) is the sponsor for that registration. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of Samsung Bioepis Co Ltd of Korea (SBK).

3 The prospective applicants (collectively, Pfizer) are concerned that the process by which the BRENZYS products are made (BRENZYS Process) may infringe one or more of three patents that they own. The present application is brought pursuant to r 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) for preliminary discovery of certain confidential documents that SBA has lodged with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which the applicants believe will enable it to decide whether or not to commence proceedings against SBA for patent infringement.

4 Rule 7.23 of the FCR provides:

(1) A prospective applicant may apply to the Court for an order under subrule (2) if the prospective applicant:

(a) reasonably believes that the prospective applicant may have the right to obtain relief in the Court from a prospective respondent whose description has been ascertained; and

(b) after making reasonable inquiries, does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain that relief; and

(c) reasonably believes that:

(i) the prospective respondent has or is likely to have or has had or is likely to have had in the prospective respondent's control documents directly relevant to the question whether the prospective applicant has a right to obtain the relief; and

(ii) inspection of the documents by the prospective applicant would assist in making the decision.

(2) If the Court is satisfied about matters mentioned in subrule (1), the Court may order the prospective respondent to give discovery to the prospective applicant of the documents of the kind mentioned in subparagraph (1)(c)(i).

5 The documents that Pfizer seeks to inspect are confidential. They are certain submodules of the Common Technical Document submitted to the TGA in order for SBA to obtain its ARTG listing for BRENZYS and include documents going to certain processes used to manufacture the BRENZYS product and batch records.

6 In addition, Pfizer seeks an order pursuant to s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) that, to the extent that any of the documents sought pursuant to an order made under FCR 7.23 are not in the possession, custody or power of SBA, that it take all reasonable steps to obtain such documents. This order has been characterised as a “Sabre” order, being one made in accordance with the principles set out in Sabre Corporation Pty Ltd v Russ Kalvin’s Hair Care Company (1993) 46 FCR 428 (Sabre).

7 The potential causes of action in respect of which the applicants seek preliminary discovery are patent infringement claims arising from three standard patents (patents). Patent no. 2005280036 is entitled “Production of TNFR-Ig fusion protein” (036 patent) and is said in the specification to provide an improved system for large scale production of proteins and/or polypeptides in cell culture. Patent no. 2005280034 is entitled “Production of polypeptides” (034 patent). It has substantially the same specification, but differently worded claims. Patent no. 2008242632 is entitled “Use of low temperature and/or low pH in cell culture” (632 patent) and is said to provide methods of improving protein production by cultured cells, especially mammalian cells. Pfizer Ireland is the owner of the 034 and 036 patents. Wyeth LLC, the second applicant, is the owner of the 632 patent. Pfizer submits that the production of documents in accordance with the orders sought will enable them to ascertain whether the BRENZYS Process infringes the claims of the three patents identified.

8 In support of their application, Pfizer relies first on affidavits from Mr Nicholas Tyacke, who is Pfizer’s solicitor and a partner of DLA Piper Australia. He gives evidence about correspondence between the parties prior to the present application and relevant to the steps taken to obtain the information sought in the current application. Secondly, affidavits from Dr Neysi Ibarra who is the Director and Group Leader of Process Development, Manufacturing Science and Technology of Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals. She gives evidence that she has been provided with the Federal Court expert evidence practice note and complied with its terms. Her evidence is about technical aspects of the patents, the process dependence of biological medicines and her opinion that the BRENZYS Process is likely to take each integer of claim 1 of each of the patents-in-suit. Thirdly, an affidavit from Louis Sebastian Silvestri, who is the Assistant General Counsel of Pfizer Inc., the parent company of each of the prospective applicants. He is the person responsible for making the decision on behalf of Pfizer whether to start a proceeding. He gives evidence as to his belief that Pfizer may have the right to obtain relief for infringement of claim 1 of each of the patents and states that his opinion is based upon the affidavit evidence of Dr Ibarra.

9 SBA contests the application. It submits that, in particular, the applicants have failed to satisfy the threshold requirement of FCR 7.23(1)(a) that the applicants reasonably believe that they may have the right to obtain relief. SBA also contends that the applicants have not made “reasonable” inquiries within FCR 7.23(1)(b) and that, in any event, the documents sought by the applicants are excessive and do not conform with the requirements of FCR 7.23(1)(c). It also contends that even if the elements of FCR 7.23(1) are made out, the Court should exercise its discretion to decline the relief sought. SBA does not, however, dispute that, in the event that an order is made pursuant to FCR 7.23 it is appropriate to grant the Sabre style order.

10 In evidence, SBA relies on, first, an affidavit from Mr Benjamin Miller, who is a partner of Ashurst Australia and the solicitor for SBA. He gives evidence critical of the scope of documents being sought in the current application on the basis that most of it, in his view, does not relate to features of the claims of the patents asserted by Pfizer to be material to their prospective case of patent infringement. He does not dispute that documents exist that are relevant to the claim. Secondly, an affidavit of Professor Stephen Mahler who is a bio-engineer who works at the Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (AIBN) which is part of the University of Queensland. He gives expert evidence about the development and production of biological medicines and responds to the affidavit of Dr Ibarra. Thirdly, an affidavit from Professor Peter Gray who is also a bioengineer who works at AIBN. He also gives evidence relevant to technical aspects of biological medicines and responds to Dr Ibarra. Fourthly, an affidavit from Associate Professor Michael Ward who holds the position of Discipline Leader: Pharmacy Education in the School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences of the University of South Australia. He gives evidence relating to biological medicinal products and biosimilars and the ENBREL product information. Fifthly, an affidavit from Young-Phil Lee, head of Cell Engineering in SBK and has since 2012 been responsible for the management of analytical works related to biosimilar development for that company. His evidence addresses the substantial investment that has been made in the development of an etanercept biosimilar product, the steps taken for the development, the confidentiality of the manufacturing processes and the timeline of public announcements regarding the development of the BRENZYS product.

11 In these reasons I consider the question of whether or not Pfizer is entitled as a matter of principle to orders of the type sought. The parties agreed that it is appropriate to hear argument separately on the form of any orders, and the scope of any documentary discovery to be given, after these reasons have been delivered. In the result, that will not be necessary, because, for the reasons set out below, I am not satisfied that Pfizer is entitled to the relief sought.

12 The issues for determination are:

(1) whether the applicants have a reasonable belief that they have the right to obtain relief for patent infringement from SBA in accordance with FCR 7.23(1)(a);

(2) whether the applicants have established that after making reasonable inquiries, they do not have sufficient information to decide whether to start proceedings to obtain relief within FCR 7.23(1)(b);

(3) whether the applicants reasonably believe that SBA has, or is likely to have, in its control documents directly relevant to the right to obtain the relief and that inspection of the documents would assist in making the decision within FCR 7.23(1)(a); and

(4) whether the Court is satisfied that an order for discovery of the kind sought should be given.

13 A biological medicine (also known as a biological, biologic or a biopharmaceutical) is a medicine that contains one or more active substances made by a biological process or derived from a biological source rather than by chemical synthesis. Biological medicines are manufactured in cell culture and include vaccines, gene therapies, and recombinant therapeutic proteins. Recombinant therapeutic proteins are proteins made by genetically engineered living bacterial, animal or plant cells. Biological medicines can consist of relatively small molecules such as human insulin, or large and complex molecules such as mAbs and mAb-soluble receptor therapeutic products (also known as “cepts”). Compared with chemically synthesised small molecule medicines, biological medicines are larger in size and more complex. Cepts are large complex proteins with complicated three dimensional structures. They are inherently difficult to replicate and are sensitive to minor alterations in manufacturing processes and conditions, such as the host cell line, expression vector, master cell line, batch size, cell culture system, harvest process and purification process.

14 Biological medicines are produced in living cells such as bacteria, yeast, insect cells and mammalian cells (host cells). This is made possible by the use of recombinant DNA technology. By using expression vectors or plasmids to introduce foreign DNA into host cells, the expression capabilities of the cells are “hijacked” to express the gene (and therefore the protein) of interest. Host cells containing the gene of interest are cultured in bioreactors and scaled up for industrial production, which, in cell culture, act as “cell factories” producing the protein.

15 The parties agreed that the development of biological medicines can be conceptualised in four broad phases:

(a) cell line development and creation of cell banks (including vector construction and engineering, transfection into the host cell, selection, formation of a stable host pool, and selection of clones);

(b) upstream bioprocessing;

(c) downstream bioprocessing; and

(d) product characterisation and formulation.

16 Cell line development and creation of cell banks (phase (a)) starts with the insertion of the gene of interest into an expression vector and the transfection of the recombinant vector or plasmid into the host cell. This is done in such a way that the host cell will synthesise useful amounts of the therapeutic protein.

17 The particular host cell used will influence the quality attributes of proteins expressed by the cell. That is, the choices made regarding the host cell line and the expression vectors play a role in the quantity and quality of the biological medicines produced. Professor Gray states that even if two biotechnology companies select the same type of cells (e.g., the Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, such as DUXB11 or DG44) as the starting point for their cell line development programs, the cell lines ultimately developed through those programs will be expected to differ from one another, including because of differences in the expression vectors and transfection processes employed. Dr Ibarra disputes that proposition at least insofar as it is relevant to the present application.

18 Various features may be introduced to drive the expression levels of the gene of interest (and therefore the amount of protein of interest produced by the host cell). These are aimed at maximising the production of mRNA, which are then translated into proteins. Further or alternatively, cell line engineering may also be used to increase the total amount of protein produced in the bioreactor harvest (“protein titre”).

19 Following transfection, cells are allowed to grow in cell culture under selection pressure for a period of time, to form a pool of stably transfected cells. Clones are then selected and grown in larger scale to form a “cell line” (that is, a cell culture developed from a single cell and therefore consisting of cells with a uniform genetic make-up). These are then frozen to create a master cell bank (from which working cell banks are derived).

20 Cell lines and expression vectors used in the commercial production of biological medicines are typically treated by the companies which develop and use them as proprietary technologies.

21 Upstream bioprocessing (phase (b)) commences once cell line development has been completed.

22 Cells are grown in cell culture and progressively scaled up for industrial production. At small-scale, most biologics are produced by a suspension culture of CHO cells in sterile, disposable shake flasks, tubes or plates typically ranging from about 1 mL to 3 L. For scale-up, a bioreactor is inoculated at low density and the cell culture is allowed to grow for a period until the cells reach a certain density and enter the “production phase”, when most of the target protein is produced.

23 Factors which need to be taken into account for upstream bioprocess development include: (a) bioreactor mode of operation (batch, fed batch, perfusion etc); (b) the cell culture media composition; (c) nutrient supplementation (“feeding”) protocol for fed-batch; and (d) the bioprocessing or environmental conditions. Further, the processing conditions of any bioreactor will need to take into account various parameters, such as dissolved oxygen concentration (the level of oxygen in the media); osmolality (the solute concentration of the media); pH; temperature; and shear (the process of stirring in a bioreactor generates forces which may shear the cell membranes). The interaction of the factors stated in this paragraph, among other things, will impact on the amount and/or qualities of the proteins produced by the bioreactor.

24 It is not in dispute that the methods claimed in the patents relate to the upstream bioprocessing phase.

25 Downstream bioprocessing (phase (c)) includes all operations occurring after cessation of bioreactor operation, beginning with the harvesting of the bioreactor, and before product characterisation. The goal of downstream processing is to separate contaminants from the active substance (given rise to by the upstream bioprocess) to a predetermined level as described in appropriate regulatory guidelines, as well as to minimise product variants.

26 Product characterisation (phase (d)) involves an examination of all of the quality attributes of the biologic product using a battery of methods. Formulation involves preparing the final therapeutic protein in a form suitable for storage, transportation and administration by injection, including addition of excipients in order to stabilise the product.

27 Glycosylation is the addition of complex sugar structures to the amino acid backbone of the therapeutic protein (which forms one of the largest and most clinically important categories of biological medicines). The composition of glycosylation can vary without changing the underlying amino acid structure of the protein. Glycosylation patterns can be highly complex and may have an influence on the biological activity of the product.

28 In Australia, the regulatory framework for assessing and granting marketing approval for biological medicines, including biosimilars, is administered by the TGA. The TGA “Regulation of biosimilar medicines” (TGA Biosimilar Guidelines) set out the regulatory framework within which the TGA evaluates applications for marketing approval of a biological medicine on the basis of biosimilarity to an already registered reference product. The TGA Biosimilar Guidelines refer to certain guidelines issued by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) including:

(a) CHMP/437/04 Rev1: Guideline on similar biological medicinal products;

(b) EMA/CHPM/BWP247713/2012: Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: quality issues (Quality Guideline); and

(c) EMEA/CHMP/BMWP/42832/2005 Rev 1: Guideline on similar biological medicinal products Containing Biotechnology-Derived Proteins as Active Substances: Non- Clinical and Clinical Issues.

29 The TGA Biosimilar Guidelines define a biosimilar medicine as “a version of an already registered biological medicine (the reference medicine)”. The TGA Biosimilar Guidelines state that:

Both the biosimilar and its reference medicine will have the following similar characteristics (demonstrated using comprehensive comparability studies):

• physicochemical

• biological

• immunological

• efficacy and safety.

30 In his affidavit, Associate Professor Ward sets out the relevant extracts from the regulatory guidelines. By way of example, the Quality Guideline states:

… Biosimilars are manufactured and controlled according to their own development, using state-of-the-art approaches and taking into account relevant and up-to-date information. …

… an extensive comparability exercise with the chosen reference medicinal product will be required to demonstrate that the biosimilar product has a similar profile in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to the reference medicinal product.

It is acknowledged that the manufacturer developing a biosimilar product would normally not have access to all information that could allow an exhaustive comparison with the reference medicinal product, particularly with regards to the manufacturing process. Nevertheless, the analytical data submitted should be such that firm conclusions on the physicochemical and biological similarity between the reference medicinal product and the biosimilar can be made.

31 The TGA Biosimilar Guidelines also assume that changes may be made to the manufacturing processes for biological medicines (whether originator or biosimilar) after regulatory approval has been given, so long as “comparability” requirements are met (comparability exercise). The principles governing the comparability exercise, as applied by the TGA and regulatory authorities in a number of other developed countries, are set out in the International Conference on Harmonization Comparability Guidance on Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject to Change in their Manufacturing Process (ICHQ5E).

32 The ICHQ5E explains:

Manufacturers of biotechnological/biological products frequently make changes to manufacturing processes of products both during development and after approval. Reasons for such changes include improving the manufacturing process, increasing scale, improving product stability, and complying with changes in regulatory requirements. When changes are made to the manufacturing process, the manufacturer generally evaluates the relevant quality attributes of the product to demonstrate that modifications did not occur that would adversely impact the safety and efficacy of the drug product. Such an evaluation should indicate whether or not confirmatory nonclinical or clinical studies are appropriate.

33 The ICHQ5E further states:

The demonstration of comparability does not necessarily mean that the quality attributes of the pre-change and post-change product are identical, but that they are highly similar and that the existing knowledge is sufficiently predictive to ensure that any differences in quality attributes have no adverse impact upon safety or efficacy of the drug product.

34 The comparability exercise formed the basis for the development of the principles by which biosimilar medicines are evaluated by the TGA and regulatory agencies in comparable developed countries.

2.3 Etanercept, ENBREL and BRENZYS

35 Etanercept is a biological medicine used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, plaque psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis. It is a “cept” produced by recombinant DNA technology. Etanercept is a polypeptide and, more specifically, is a dimeric fusion protein (a fusion protein is a protein made from a fusion gene created through the joining of two or more genes that originally coded for separate proteins, such proteins can be created artificially by recombinant DNA technology for use as biological medicines) consisting of the extracellular ligand-binding portion of the human 75 kilodalton tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) linked to the fragment crystallisable region (Fc) of human IgG1.

36 Etanercept is the active ingredient in ENBREL, which is manufactured by Pfizer Ireland. ENBREL has been commercially available since 1998 in the United States of America, since 2000 in the European Union and since 2003 in Australia, and is the reference medicine against which biosimilars must establish compliance with regulatory authorities in order to be marketed. Prior to 2007, foetal bovine serum was used for the manufacture of etanercept for ENBREL. Since 2007 a serum-free process has been used, which uses chemically defined media that does not contain foetal bovine serum. It is this process that Dr Ibarra defines as the “Current Pfizer Process” and to which I refer below as the Pfizer Process. Dr Ibarra gives evidence that the Pfizer Process is the only serum-free process that she knows to have been used for the commercial production of Etanercept.

37 In July 2016, the BRENZYS products were listed on the ARTG. The production information states that etanercept is “produced by recombinant DNA technology in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) mammalian expression system”. It also states that etanercept is manufactured using a serum-free process.

38 Set out below is claim 1 of the 034 patent, with integer numbers added for ease of reference:

1 A method of producing a polypeptide in a large-scale production cell culture comprising the steps of:

2 providing a cell culture comprising;

3 mammalian cells that contain a gene encoding a polypeptide of interest, which gene expressed under condition of cell culture; and

4 a medium containing glutamine and having a medium characteristic selected from the group consisting of:

5 (i) a cumulative amino acid amount per unit volume greater than 70 mM,

6 (ii) a molar cumulative glutamine to cumulative asparagine ratio of less than 2,

7 (iii) a molar cumulative glutamine to cumulative total amino acid ratio of less than 0.2,

8 (iv) a molar cumulative inorganic ion to cumulative total amino acid ratio between 0.4 to 1,

9 (v) a combined cumulative amount of glutamine and asparagine per unit volume of greater than 16 mM, and combinations thereof;

10 maintaining said culture in an initial growth phase under a first set of culture conditions for a first period of time sufficient to allow said cells to reproduce to a viable cell density within a range of 20% – 80% of the maximal possible viable cell density if said culture were maintained under the first set of culture conditions;

11 changing at least one of the culture conditions, so that a second set of culture conditions is applied;

12 maintaining said culture for a second period of time under the second set of conditions and for a second period of time so that the polypeptide accumulates in the cell culture.

39 Claim 1 of the 036 patent, with integer numbers added, is as follows:

1 A method of producing TNFR-Ig in a large-scale production cell culture comprising the steps of:

2 providing a cell culture comprising;

3 mammalian cells that contain a gene encoding TNFR-Ig, which gene expressed under condition of cell culture; and

4 a medium containing glutamine and having a medium characteristic selected from the group consisting of:

5 (i) a cumulative amino acid amount per unit volume greater than 70 mM,

6 (ii) a molar cumulative glutamine to cumulative asparagine ratio of less than about 2,

7 (iii) a molar cumulative glutamine to cumulative total amino acid ratio of less than about 0.2,

8 (iv) a molar cumulative inorganic ion to cumulative total amino acid ratio between about 0.4 to 1,

9 (v) a combined cumulative amount of glutamine and asparagine per unit volume of greater than about 16 mM, and combinations thereof;

10 maintaining said culture in an initial growth phase under a first set of culture conditions for a first period of time sufficient to allow said cells to reproduce to a viable cell density within a range of about 20% – 80% of the maximal possible viable cell density if said culture were maintained under the first set of culture conditions;

11 changing at least one of the culture conditions, so that a second set of culture conditions is applied;

12 maintaining said culture for a second period of time under the second set of conditions and for a second period of time so that the TNFR-Ig accumulates in the cell culture.

40 Claim 1 of the 632 patent, with integer numbers added, is as follows:

1 A method of producing a protein in a cell culture comprising:

2 (a) growing cells in the cell culture at a reduced temperature, wherein the reduced temperature is in a range of 27.0 C to less than 30.0 C; and

3 (b) growing cells in the cell culture at a reduced pH, wherein the reduced pH is in a range of 6.80 to less than 7.00;

4 to reduce production of misfolded proteins and/or aggregated proteins.

2.5 The Cho article and Schiestl article

41 Dr Ibarra draws attention to an article entitled “Evaluation of the structural, physicochemical, and biological characteristics of SB4, a biosimilar of etanercept” by Cho et al (Cho article). The Cho article records that it was written by employees of SBK or its collaborator, Biogen, and the work was funded by SBK. It refers to a product identified as “SB4” which is accepted by SBA to be the BRENZYS etanercept product. Dr Ibarra notes that the Abstract indicates that SB4 was developed as a biosimilar to ENBREL and refers to extensive structural, physicochemical, and biological testing that was performed using state-of-the-art technologies during a side-by-side comparison of the two products.

42 In her evidence in chief at [121], Dr Ibarra notes five relevant matters in relation to the assessment in the Cho article of the similarities between BRENZYS and ENBREL; (a) the amino acid sequences were identical; (b) the characteristics of certain disulfide-linked peptides and their bonds; (c) that a total of 23 peaks corresponding to N-glycan structures were detected by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, and 21 species of N-glycan were identified in SB4. This suggested, according to the authors, that the structure of each N-glycan species on SB4 was identical to that of the corresponding species on the reference product and that there was no N-glycan structure specific only to SB4; (d) that the level of Peak 3 impurity consisting of both aggregates and disulfide-scrambled species, was lower for SB4 than for the reference product; and (e) the overall ability of SB4 to inhibit TNF was similar to that of the reference product. In her reply evidence, Dr Ibarra places significant reliance on (c), to which I refer further below. Matter (d), on its face, is a dissimilarity between BRENZYS and the reference product, while matter (e) simply suggests that the efficacy of both products is ‘similar’. Comparable efficacy is a requirement to establish biosimilarity, and as is addressed below, this is not of itself sufficient to support an inference that the BRENZYS Process takes the integers of the patents.

43 Professor Mahler referred to the Cho article and to the five features identified by Dr Ibarra. In relation to (a) (the amino acid sequences were identical); and (b) (the characteristics of certain disulfide-linked peptides and their bonds), Professor Mahler observes that these similarities do not suggest anything about the particular processing or culture conditions in the bioreactor. The similarities are to be expected because SB4 and the reference product each refer to the same protein. In argument Pfizer accepted that the similarity of features (a) and (b) was unlikely to bespeak similarity of process.

44 In relation to (c) (glycosylation), (d) (Peak 3 impurity) and (e) (overall ability to inhibit TNF), Professor Mahler does not consider that these features provide any meaningful information as to the particular processing or culture conditions in the bioreactor during growth of the cells or production of the protein. The similarities of the products identified in the Cho article are examined at the product characterization stage, after all of the phases of production are complete. Dr Ibarra takes issue with this point, which I return to below.

45 Professor Mahler developed his observations in this regard by reference to an article entitled “Acceptable changes in quality attributes of glycosylated biopharmaceuticals” in Nature Biotechnology 2011 by Schiestl et al (Schiestl article) which is referred to in the materials annexed to Dr Ibarra’s first affidavit. The changes identified in this article arise from the change in the manufacturing process of ENBREL. The Schiestl article says (emphasis added):

The data [for ENBREL] revealed a highly consistent quality profile for batches having expiry dates until the end of 2009. After this time period, batches with a second and changed quality profile appeared on the market in parallel (Fig. 3). Major differences were found in the glycosylation profile. The amount of variants containing the N-glycan G2F decreased from ~50% in the pre-change to ~30% in the post-change material (Fig. 3b, d and Supplementary Fig. 3b, d). The CEX analysis showed a change of the amount of the basic variants, which corresponds primarily to C-terminal lysine variants from 15-30% in the pre-change to 40-60% in the post-change material (Fig. 3a, c and Supplementary Fig. 3a, c). As for the other products … the pre- and the post-change versions of Enbrel were also marketed under the same label.

…

… the data we present here reveal substantial alterations of the glycosylation profile for all tested products. Different lots of… Enbrel also showed changes of the N- and C-terminal heterogeneity. … Because of the abruptness and the magnitude of the observed alterations, they are most probably caused by changes in the manufacturing processes. As the glycosylation profile is defined by the production cell line, growth conditions and the purification sequence, these findings may reflect changes in one or more of these components. The data indicate the magnitude of changes in quality attributes of marketed products. All tested products remained on the market with unaltered labels in the tested time frame, indicating the observed changes were predicted to not result in an altered clinical profile and are therefore acceptable by the health authorities.

46 Professor Mahler agrees with the conclusions expressed in the Schiestl article insofar as they suggest that the changes in the ENBREL product signify a change in the manufacturing process, that the change could be a change in any one of phases (a) (cell line production), (b) (upstream growth conditions) or (c) (downstream processing) and that despite the changes the regulatory authorities were apparently satisfied that the changes did not result in clinically significant differences to the end product.

47 The applicants rely on power conferred on the Court by s 23 of the FCA Act and FCR 7.23. Section 23 provides:

The Court has power, in relation to matters in which it has jurisdiction, to make orders of such kinds, including interlocutory orders, and to issue, or direct the issue of, writs of such kinds, as the Court things appropriate.

48 Rule 7.21 of the FCR provides relevant definitions as follows:

In this Division:

prospective applicant means a person who reasonably believes that there may be a right for the person to obtain relief against another person who is not presently a party to a proceeding in the Court.

prospective respondent means a person, not presently a party to a proceeding in the Court, against whom a prospective applicant reasonably believes the prospective applicant may have a right to obtain relief.

49 The policy underlying FCR 7.23 remains the same as that of its predecessor, Or 15A r 6 of the Federal Court Rules 1979 (Cth), namely that “even where there is a reasonable cause to believe that a person may have a right to relief, nevertheless that person may need information to know whether the cost and risk of litigation is worthwhile” Optiver Australia Pty Ltd v Tibra Trading Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 133; (2008) 169 FCR 435 (Optiver) at [36]. It has been held that the rule should be given the fullest scope its language will reasonably allow. The proper break on any excesses in its use is the discretion of the Court, which is required to be exercised in the particular circumstances of each case; Optiver at [43].

50 In Reeve v Aqualast Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 679 (Reeve) at [63] – [66], in a statement that has been adopted by numerous single judges of this Court, Yates J set out a summary of the applicable principles:

63 It is apparent that r 7.23 proceeds on a tightly structured set of considerations for its application in a given case. Without seeking to supplant the precise language of the rule, and at the risk of some repetition, the prospective applicant must establish:

(a) the existence of a reasonable belief in a right to obtain relief in the Court;

(b) the making of reasonable inquiries directed to obtaining sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain that relief;

(c) an insufficiency of information to enable that decision to be made;

(d) the existence of a reasonable belief that the prospective respondent has or had, or is likely to have or have had, documents –

(i) that are directly relevant to the question whether the putative right to relief exists; and

(ii) whose inspection would assist in making a decision whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain that relief.

64 The language of r 7.23(1) makes clear that the power to order a prospective respondent to give preliminary discovery is contingent upon each of its requirements being established. Even if the prospective applicant establishes these requirements, r 7.23(2) shows that a broad discretion remains in the Court as to whether, and to what extent, discovery should be granted. In this connection the intrusive nature of an order for preliminary discovery should be borne in mind. Nevertheless, the rule is to be construed beneficially so as to be given “the fullest scope that its language will reasonably allow”: St George Bank Ltd v Rabo Australia Ltd [2004] FCA 1360 at [26].

65 In Ebos Group Pty Ltd v Team Medical Supplies Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 862 Flick J held that the general statements of principle set out by Lindgren J in Glencore International AG v Selwyn Mines Ltd (recs and mgrs apptd) (2005) 223 ALR 238 at [9]-[16], respecting preliminary discovery under O 15A r 6 of the Federal Court Rules, remain apposite to an application under r 7.23. In Higgins v Hancock (2011) 199 FCR 393 Jacobson J at [55]-[59] expressed the same view. Those statements of principle, translated to the present context under r 7.23, are as follows:

(a) The test of reasonable belief is an objective test.

(b) The provision does not allow for third party discovery. Preliminary discovery may be ordered only against the person from whom there is reasonable cause to believe the applicant is or may be entitled to obtain relief.

(c) A document relating only to the question whether a judgment against a person is likely to be enforceable is not within the rule and such a document is therefore not discoverable. If the only reason why an applicant has not sufficient information to enable a decision to be made whether to commence a proceeding is that the applicant lacks sufficient information as to the respondent’s capacity to satisfy a judgment, preliminary discovery will not be available.

(d) The measure of any preliminary discovery to be ordered is the extent of information that is necessary, but no more than that which is necessary, to overcome the insufficiency of information already possessed by the applicant after the making of all reasonable inquiries, to enable a decision to be made whether to commence a proceeding.

(e) The stronger the relevant evidence already available to an applicant of its right to obtain relief the weaker will its position be to obtain preliminary discovery.

(f) While a respondent to an application for preliminary discovery is entitled to remain passive, the applicant must place before the Court all of the evidence already available to it relevant to the sufficiency of the information it possesses to enable a decision to be made whether to commence a proceeding. The applicant must not hold back information. This obligation on the applicant to be forthcoming arises from the special and intrusive nature of preliminary discovery and the fact that ordinarily the respondent will not know, or be in a position to expose, the full extent of the information already available to the applicant.

(g) While the notion of reasonable belief may set the threshold “at quite a low level”, there must be some tangible support that takes the existence of the alleged right beyond mere “belief” or “assertion” by the applicant.

66 To these general statements of principle can be added the summary of principles provided by Hely J in St George Bank Ltd v Rabo Australia Ltd [2004] FCA 1360 at [26] as well as the recent discussion by Katzmann J in EBOS Group Pty Ltd v Team Medical Supplies Pty Ltd (No 3) (2012) 199 FCR 533 at [15]-[32], especially as to the similarities and differences between the current and former rules.

51 The primary requirement of FCR 7.23(1)(a) is that the prospective applicant reasonably believes that he or she may have the right to obtain relief. In John Holland Services Pty Ltd v Terranora Group Management Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 679 (John Holland) at [14] Emmett J said (emphasis in original):

The facts that can reasonably ground a suspicion may be quite insufficient to reasonably ground a belief. Objective circumstances that will be sufficient to demonstrate a reason to believe something, point more clearly to the subject matter of the belief than circumstances that will give rise to a mere suspicion. That is not to say that the objective circumstances must establish on the balance of probabilities that the subject matter in fact occurred or exists. Belief is an inclination of the mind towards assenting to, rather than rejecting, a proposition. The grounds that can reasonably induce that inclination of the mind may nevertheless, depending on the circumstances, leave something to surmise or conjecture (George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 at pars [115.6 – 116.4]).

52 A question has arisen on the authorities as to whether the language of FCR 7.23(1)(a) (“reasonably believes”) requires an objective and a subjective belief. In EBOS Group Pty Ltd v Team Medical Supplies Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 48; (2012) 199 FCR 533 at [28] Katzmann J doubted that changes implemented in the current rule were intended to introduce a requirement of a subjective belief. Nevertheless, out of abundant caution and in the absence of higher authority, her Honour proceeded on the basis that evidence of an applicant’s subjective belief was also necessary (at [32]). This approach was adopted by Perry J in ObjectiVision Pty Ltd v Visionsearch Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1087; (2014) 108 IPR 244 (ObjectiVision) at [34]. In the present case, there is no dispute that the requisite subjective opinion is held. The substantive debate concerns whether Pfizer has an objective basis.

53 In St George Bank Ltd v Rabo Australia Ltd [2004] 211 ALR 147; (2004) 211 ALR 147 (St George) at [28] Hely J observed that at its lowest level, subparagraph (a) (of FCR Or 15A r 6) requires that there be reason to believe that the applicant may have the right to obtain relief in this Court. On the facts of that case, Hely J noted at [29] that:

… Whilst St George does not need to go so far as to establish a prima facie case, St George does have to establish that there is reasonable cause to believe that each of the necessary elements of a potential cause of action exists. The evidence must incline the mind to the view that Rabo and/or Rabo CF deliberately withheld material information from St George. The threshold test under sub-paragraph (a) may be set at quite a low level… but, as I have said earlier, it is not sufficient to point to a mere possibility that St George may have a claim, and that claim is completely dependent on the as yet unknown facts.

54 In St George Hely J noted at [26(e)] that whilst uncertainty as to only one element of a cause of action might be compatible with the “reasonable cause to believe” required by subparagraph (a), uncertainty as to a number of such elements may be sufficient to undermine the reasonableness of the cause to believe. Hely J (at [26], citing John Holland) said “[i]f there is no reasonable cause to believe that one of the necessary elements of a potential cause of action exists, that would dispose of the application insofar as it is based on that cause of action”. This statement was subsequently cited by Siopis J in Valra Pty Ltd as Trustee for Abdul Rahim Valibhoy Family Trust v Mag Men Holdings Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 23; 110 ACSR 554 at [62].

55 The above analysis demonstrates that an application for preliminary discovery cannot be sustained without evidence that inclines the mind towards the matters of fact in question (Optiver at [48]; ObjectiVision at [39]). As the Full Court held that in Optiver at [49]:

Before [the primary judge] Tibra argued that there were significant shortcomings in the evidence in this regard. On the appeal, senior counsel for Tibra elaborated on these alleged shortcomings at some length. We do not think it necessary in the circumstances to review these arguments, which in essence go to the ultimate merits of Optiver’s case. Optiver of course accepts that it does not have the evidence to support a case - that is the raison d’être for the present application. However, there is sufficient evidence, irrespective of the shortcomings relied upon by Tibra, to conclude that there is reasonable cause to believe Optiver may have a right to obtain relief. …

56 In the present application, SBA led evidence to challenge the basis upon which Pfizer contended that the requisite objectively held belief arose. To a substantial extent, that evidence raised factual conflicts which it was not possible for me to determine on an application of this kind, there being no cross-examination, among other difficulties. Those difficulties were compounded by the fact that Dr Ibarra gave evidence in reply that generally took issue with the evidence of SBA’s witnesses, and then challenged only specific propositions which were advanced. That had the effect of leaving unclear precisely which matters were the subject of disagreement.

57 Pfizer relies on six contentions which it submits, when considered cumulatively, give rise to the conclusion that it has the requisite belief within FCR 7.23(1)(a). I consider each separately below, and then cumulatively when I express my conclusions.

First contention: some admitted integers

58 Pfizer observes that it is common ground between the expert witnesses that the BRENZYS manufacturing process for etanercept would satisfy the first three integers of claim 1 of each of the 34 and 36 patents and integer 1 of claim 1 of the 632 patent. In my view this point does not go very far. The expert evidence agreed that every process for the manufacture of etanercept would satisfy these integers. Those integers are present by reason of the fact that the protein of interest is etanercept. Accordingly, I regard this factor, taken alone, as neutral.

Second contention: advantage and opportunity

59 Pifzer contends that in the development of the process for making BRENZYS, SBK had incentives, due to the advantages set out in the patents of the claimed processes and the widely recognized importance of those advantages, and the opportunity, given that the patents had been published, to adopt the processes used in the patents.

60 As to the incentive for a party such as SBK to utilise the patents, Pfizer points to the evidence of Dr Ibarra who summarises the effect of the patents. In relation to the 034 and 036 patents, Dr Ibarra says that the process provides an improved system for large-scale production of polypeptides in cell culture, which involves the provision of amino acids, glutamine, asparagine, inorganic ions and concentrations that support relatively high levels of viable cell density and cell production that result in lower accumulation of metabolic waste products. These advantages are, it is said, reflected in the integers of the claims, which provide ranges desirable for media formulations.

61 Professor Mahler’s evidence refers to each of the patents. Dr Ibarra in her evidence in reply does not specifically take issue with the Professor’s evidence concerning the effect of the patents. He understands the 034 patent to be concerned with phase (b), upstream processing and in particular “Media Prep” feeding into the large-scale bioreactors. In particular, he understands it to be primarily directed to batch and fed-batch processes with minimal feeds, although perfusion processes are not necessarily excluded. He points out that although the 034 patent teaches that a culture medium with “one, several or all” of the characteristics set out in integers 5 – 9 of claim 1 of the 034 patent may be used to optimise cell growth he observes that the patent does not teach that a culture medium with one or more of those characteristics will necessarily optimize the conditions of cell grown, viability and/or protein production (including etanercept). Professor Mahler developed this point by reference to an example given in the 034 patent of the use of a medium containing glutamine and having a medium characteristic selected from the group selected from the ranges set out in integers 5 – 9 of claim 1. He notes that the example given demonstrated that the medium having none of the characteristics identified within the ranges in the claim demonstrated a growth rate of relevant cells that was similar to that which did fall within the ranges.

62 In relation to the 036 patent, Professor Mahler notes that it is generally concerned with the same aspects of the biologics production process as the 034 patent.

63 In relation to the 632 patent, the process claimed is said in the specification to produce proteins such as etanercept with less aggregates and fewer misfolded proteins, in circumstances where the presence of such things is said to be undesirable because it may lead to an adverse event upon administration to patients. Dr Ibarra gives evidence that cells grown in cell cultures at temperatures above 30˚C and at a pH above 7 can result in increased cell aggregation and misfolding compared to cells grown in cell cultures within this temperature and pH range.

64 In relation to the 632 patent, Professor Mahler expresses the view that it is also generally concerned with phase (b), upstream bioprocessing, but, unlike the other two patents, more particularly with the bioprocessing or environmental conditions, which take into account dissolved oxygen concentration, osmolality, pH, temperature and shear. He notes that there are many steps in the production process which precede and follow those aspects and which collectively impact on the final product.

65 Professor Mahler takes issue with a suggestion in Dr Ibarra’s affidavit that if the method claimed in claim 1 of the 632 patent is followed there will necessarily be a reduction in aggregates and fewer misfolded proteins. He says that this is not established, in particular because the cell line used in the experiments in the 632 patent is not disclosed and is likely to be a proprietary master cell line which is not available to the public. Different cell lines will behave somewhat differently under various culture conditions. It does not follow that the results in one may be extrapolated to all other master cell lines.

66 I accept that the patents point to advantages in the methods to which they refer. I also accept that these advantages are confined to discrete aspects of the phase (b) part of a process that may, but need not necessarily, be used to produce etanercerpt. In the result, I give a little, but not a great deal of weight to any inference arising from the “desirable” aspect of the patents in suit insofar as it is submitted to provide an “incentive” to a third party to following the process described. The patent claims are not specifically directed to etanercept. Absent other evidence to suggest that the processes described may have been used, the fact that these patents exist does little to indicate that the processes described therein have been utilized in the BRENZYS Process. This point rises little above the proposition that “a patent exists, therefore it must be desirable to adopt the features therein”. I accept, however, that the fact that the patents were published before SBK commenced work on the development of BRENZYS indicates that there was an opportunity for SBK to review them. The affidavit of Mr Lee gives some indication of the size and scope of the work conducted by SBK in developing BRENZYS and it is entirely possible that the patents were obtained in searches.

Third contention: serum free process

67 The product information for the BRENZYS products states that their active ingredient etanercept is manufactured using a “serum free process”. Dr Ibarra states in her evidence that since 2007 the manufacture of etanercept for the ENBREL products has employed a process that is serum free. Her evidence is that the Pfizer Process is the only serum-free process that she knows of that has been used for the commercial production of etanercept. Whilst the Pfizer Process is not publicly known, the patents in suit provide, in Pfizer’s submission, an opportunity for the manufacturer of a biosimilar to emulate the Pfizer Process by adopting aspects of the method of production described and claimed. In this regard, Pfizer points to evidence that indicates that manufacturers are recommended, so far as possible, to look for guidance in the production of a biosimilar from the processes used by the innovator. Such recommendations are to be found in the World Health Organization Guidelines on evaluation of similar bio-therapeutic products.

68 This submission is expressed at a broad level of generality. It is relied upon primarily as one of the several cumulative inferences to suggest that the BRENZYS Process is “similar” to the Pfizer Process.

69 SBA seeks to answer this submission on two levels. First, SBA correctly submits that the fact that BRENZYS is produced using a serum-free medium does not have any specific bearing on whether that process uses features of the claims in issue. As Professors Mahler and Gray observe in their evidence, neither the body of the patents in suit nor the claims require the process to be serum-free. Dr Ibarra accepts that the use of a serum-free process is not per se indicative of the presence of any of the integers of the claims in issue. Accordingly, the fact that the process used is serum free bears no direct relation to the question of whether the integers are present, but only upon the inference that Pfizer asks the Court to make that the BRENZYS Process is similar to the Pfizer Process.

70 Secondly, SBA points to the evidence of Professor Mahler which indicates that a number of patents and papers have been written describing serum-free processes for the production of etanercept/TNFR:Fc fusion proteins. It submits that there is no basis for concluding, just because the BRENZYS Process uses a serum-free medium, that the two processes are “very similar” or that the source for the BRENZYS Process lies in the patents.

71 I consider that there is force in SBA’s submission. Dr Ibarra’s absence of knowledge of another serum-free process in commercial use does not advance Pfizer’s case very far. The processes used by competitors are, the parties agree, kept confidential. Dr Ibarra simply does not know what other processes have been used. Whilst I accept that the evidence of patents and papers demonstrating that others have written about serum-free processes does not mean that a commercially produced form of etanercept has utilised the described processes, it does, in my view, diminish the force of Dr Ibarra’s assumption.

72 In this context I note that Dr Ibarra accepts in her evidence that other processes, unrelated to those in the patents, are theoretically available to produce a serum free product that is biosimilar to ENBREL. Her evidence is simply that she is not aware of any such processes actually being used.

Fourth contention: biosimilarity and glycosylation profiles

73 Pfizer contends that as the BRENZYS products have been determined to be biosimilar to the ENBREL products, and given the similarities identified in the Cho article, this suggests (to Dr Ibarra) that the etanercept in the BRENZYS products may be made by a process that is very similar to the process for manufacturing the etanercept in the ENBREL products. This leads to the fifth of Pfizer’s contentions (which I address below), which is closely related to the fourth, which is that the Pfizer Process falls within the claims of each of the patents in issue, and this permits the inference that the BRENZYS Process may fall within the claims.

74 It is necessary to explain the evidence relevant to this subject.

75 There was no dispute on the evidence that the characteristics of a biological medicinal product are a result of the process used to manufacture it. The parties also agree that the quality, safety and efficacy of biological medicines are linked to the process by which they are manufactured and may be influenced by even minor alterations in the manufacturing processes and conditions used. However, they are at odds as to the conclusions that may safely be drawn from these propositions.

76 SBA contends that the fact that BRENZYS is biosimilar to ENBREL says nothing about how BRENZYS is made. It points to compelling evidence in support of that proposition.

77 An example of a circumstance where one product is biosimilar to another but uses a different manufacturing process may be seen with ENBREL. The process used to manufacture the etanercept in ENBREL changed from the use of a serum based medium to a serum free medium. This yielded the inference, which was drawn by Professor Mahler that even though there was a fairly significant process change, nevertheless ENBREL made using the new process was found by the relevant authorities to be biosimilar to the product made using the serum based medium. In this regard Professor Mahler referred to the Schiestl article, which indicates that acceptable variations for products have remained on the market with an unchanged product label.

78 The Schiestl article indicates, amongst other things, that major differences were to be found in the glycosylation profile of the etanercept produced. It also points to the fact (as the underlined passages in the quotation at [45] above indicate) that glycosylation can be brought about in phase (a) (cell line development), phase (b) (upstream processing) and phase (c) (downstream processing) of the production process. Despite these differences, the TGA has continued to accept ENBREL as a product on the ARTG for the same indications as those for which it was registered before the change in process. In the result, Professor Mahler concludes, the new process for making etanercept using the Pfizer Process is “biosimilar” to the process used for producing serum-based media in the old process.

79 Taken together, these matters support the view (held by each of Professors Gray and Mahler) that the fact that a product is biosimilar does not inform one as to the process by which it is made.

80 Pfizer accepts that SBA’s position represents one available inference, but puts forward another one, which, it submits, is no less available.

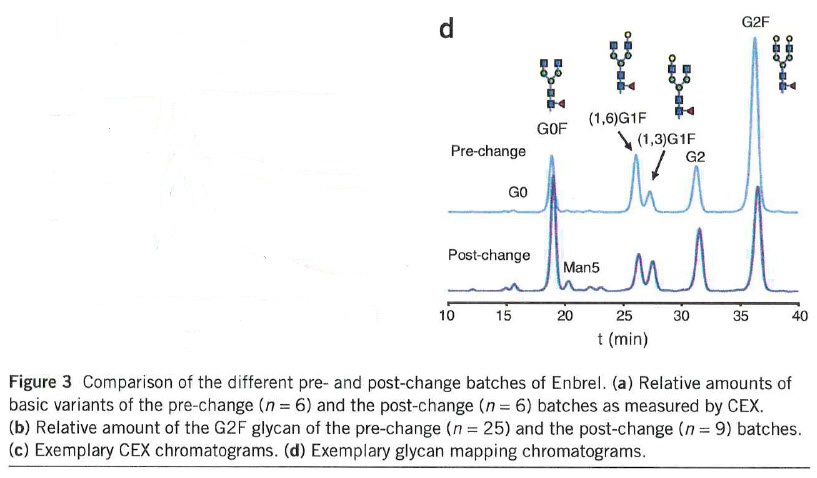

81 It points to the Schiestl article for another purpose. It refers to Fig. 3d in the Schiestl article which is set out below:

82 Pfizer submits that Fig. 3d shows that the size of the peaks in the glycosylation profile “pre-change” and “post-change” is significantly different, although the peaks are located broadly similarly. The significant difference in size supports the proposition, it submits, that a significantly different process was used to make ENBREL.

83 By contrast, the Cho article demonstrates aspects of physicochemical similarity between the etanercept in ENBREL (as produced by the Pfizer serum-free process) and the etanercept in BRENZYS produced by SBA’s serum-free process. The glycosylation profiles reported in Cho are, the experts on all sides agreed, “very similar”. On page 127 of the Cho article , the authors report:

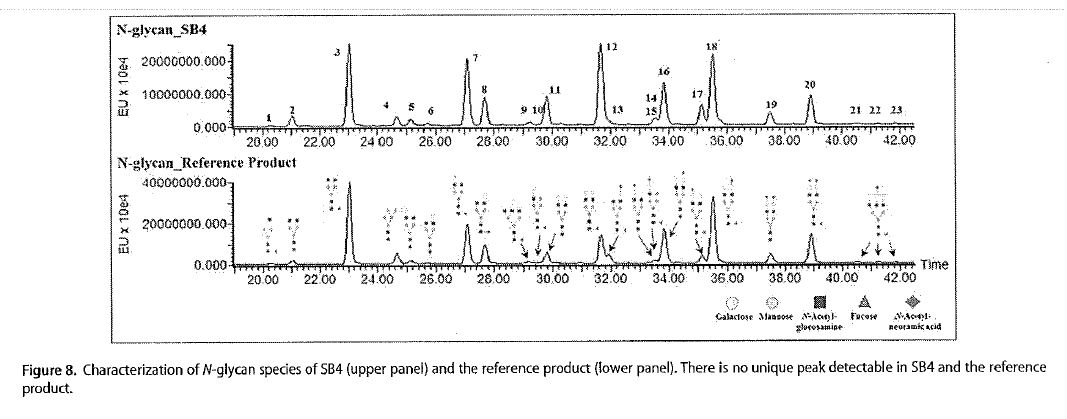

A total of 23 peaks corresponding to N-glycan structures were detected by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) with a fluorescence detector (Fig. 8), and 21 species of N-glycan were identified in SB4 by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Each HILIC peak revealed an identical MS/MS spectrum between SB4 and the reference product [ENBREL]. This result suggested that the structure of each N-glycan species on SB4 was identical to that of the corresponding species on the reference product and that there was no N-glycan structure specific only to SB4. …

84 Figure 8 is as follows:

85 Dr Ibarra concludes that the structure of each N-glycan species was identical to the corresponding species on the reference product (that is, ENBREL). The relative closeness of the glycosylation profiles demonstrated in Cho, when contrasted with the differences exhibited in Schiestl, lead to the available inference, Pfizer submits, that the closeness demonstrates a similarity between the process used to make ENBREL and the process used to make BRENZYS.

86 Professor Gray disagrees with Dr Ibarra’s conclusion. He accepts that the two products were sufficiently similar such that the BRENZYS product has been granted marketing approval by the TGA on the basis of biosimilarity to ENBREL, which indicates to him that the products are expected to have comparable safety and efficacy. But he draws attention to what he describes as minor differences (lower content of high molecular weight aggregates, lower level of impurities and some difference in the glycosylation profiles in the BRENZYS product) as informing him that there will be differences between the processes used in the manufacture of BRENZYS compared to its reference product. Further, Professor Gray notes (as does Professor Mahler and the Schiestl article itself) that the glycosylation profile may be caused by each of phases (a) – (c) of the production process. As I have earlier noted, this distinction has relevance to the present debate because the patents in issue are only directed to aspects of the process that fall within phase (b) (upstream processing).

87 Dr Ibarra takes issue with aspects of Professor Gray’s evidence and says first, that the method claims for each of the 034 and 036 patents include a cell culture medium with one or more of five median characteristics which are expressed as ranges. Whilst differences, such as those observed by Professor Gray in the BRENZYS product, may be associated with differences in the manufacturing process (as Professor Gray contends), they do not cause her to alter her view that the process used in making the BRENZYS product may fall within the ranges set out in the claims.

88 Secondly, Dr Ibarra contends there is a limited ability to influence glycosylation in the downstream process and that although there is a theoretical possibility that the glycosylation may be influenced in phase (a), cell production, that likelihood is significantly diminished by the fact that both Pfizer and SBK use the CHO mammalian ovary cell line in phase (a). Dr Ibarra’s evidence in reply is that in her experience generally cell lines of a similar type would fall within a predictable range of values and respond to environmental conditions in a generally similar manner (because the vast majority of the cell machinery of the two cell lines will be highly similar). Accordingly, Dr Ibarra’s view is that the most likely source of the glycosylation profile is in the process used in phase (b), which is the phase to which the claims of the patents are directed.

89 Taken as a whole, Pfizer submits that this material leads to the result that the substantially similar glycosylation profiles identified in the Cho article permit the inference of a substantially similar manufacturing process being used in the production of the etanercept in BRENZYS. In this context, Pfizer relies heavily on [21] of Dr Ibarra’s second affidavit which is as follows:

In paragraph 144, Professor Gray cites page 312 of the Schiestl paper for the proposition that “the glycosylation profile is defined by the production cell line, growth conditions and the purification sequence”. I note that the Schiestl paper found “major differences” between the glycosylation profiles of the etanercept for ENBREL® manufactured by the previous serum-based process and the Current Pfizer Process, whereas the glycosylation profiles of SB4 (being the Brenzys Products) and the etanercept in ENBREL®, as compared in the Cho Article, are very similar. In subparagraph 72(c), Professor Gray describes the differences between these glycosylation profiles of etanercept made by the Current Pfizer Process and etanercept in the Brenzys Products as “slight”. In my opinion, based on my experience in the manufacture of biological medicines, differences between manufacturing processes producing the same therapeutic protein, are likely to result in differences between the glycosylation profiles of the two resulting proteins. As there is a limited ability to influence glycosylation in downstream processing, the similarity in glycosylation profiles between the etanercept in the Brenzys Products and the etanercept made by the Current Pfizer Process suggests to me that just as the Current Pfizer Process takes each of the integers of claim 1 of each of the ‘034 and ‘036 Patents, the process for manufacturing the Brenzys Products may take the integers of these claims.

90 Although Dr Ibarra noted in her evidence in chief that glycosylation was one of five similarities between the products, the emphasis placed on this similarity did not emerge until her second affidavit, after the evidence of Professors Mahler and Gray had been filed (two of those similarities ((a) and (b)) have since been acknowledged by Pfizer to have no relevance to the question of similarity. Additionally, (d) is in fact a different between the products – see [42] to [44] above).

91 Nothing in the evidence adduced by Dr Ibarra leads to the conclusion that by reason of the similarity of the glycosylation profiles per se one or more integers of the claims in issue are present. Indeed, in annexures NI-12 to NI-14, where Dr Ibarra conducts an integer-by-integer analysis of the claims, no mention is made of the glycosylation profile as being indicative of the presence of any integers.

92 Further, the logic of Dr Ibarra’s conclusion (that because certain glycosylation profiles are very similar, the BRENZYS Process may be within the claims) is difficult to accept. The claims do not refer to glycosylation at all. No evidence suggests that by following the methods claimed in one or more of the patents, a glycosylation profile will be produced that has any particular characteristics or be similar in one way or another to another produced (by a different organization, under different conditions).

93 Accordingly, I find Dr Ibarra’s first answer to Dr Gray’s evidence (going to the ranges within the claims) to be unpersuasive. The better view is that a biosimilar product may be expected to have considerable similarities with the reference product, and those similarities do not provide any indication of the processes by which they are made are similar. The ENBREL experience supports this. Where there are noted to be differences between the end products it is no answer to assert, as Dr Ibarra does, that the claims in suit are to “ranges” of process conditions. No evidence has been adduced to suggest that the end product is referable to the claims at all.

94 Dr Ibarra’s second answer to Professor Gray is that glycosylation may be affected in phase (b) and that because of the common use of CHO mammalian cells it is unlikely to occur in phase (a). That observation does not accord with the teaching of the patents. For instance, in relation to the 632 patent integers 2 and 3 of claim 1 of the 632 patent direct attention to growing cells in a cell culture at a reduced temperature (to a range of 27˚C to less than 30˚C) and a reduced pH (in a range of 6.80 to less than 7.00). However, the examples in the 632 patent indicate that glycosylation is a step which takes place prior to the process steps the subject of the claims. For instance, at [0114] of the 632 patent it says (emphasis added):

… For instance, growing cells at a reduced temperature of 29.5˚C significantly reduced concentration of both misfolded and aggregated TNFR-Fc, while having minimal effects on TBFR-Fc glycosylation.

95 Similar observation was made in relation to reduced pH which at [0123] was said to significantly reduce the proportion of misfolded and aggregated TNFR-Fc protein, “while having minimal effects on glycosylation of TNFR-Fc”.

96 The consequence is that claim 1 of the 632 patent is directed towards minimising an adverse effect on glycosylation, but not the step of glycosylation itself. The 034 and 036 patents barely refer to glycosylation at all. Each patent assumes, naturally enough, that phase (a) has taken place where, the experts agree, the characteristics of the glycosylation profile may be determined. It is not, in my view, persuasive to dismiss the effects of this phase, on the basis that both Pfizer and the BRENZYS process use CHO mammalian cell line. Not only is cell variation within CHO inevitable (as the evidence indicates), in addition, phases (a) and (c) influence glycosylation.

97 Ultimately, Dr Ibarra’s evidence in this respect does not rise above speculation (Pfizer refers to it as an inference) that the similarities observed might mean that the BRENZYS Process is similar to the Pfizer Process. That speculation, in my view, clings tenuously to the coincidences identified in Cho. These coincidences are cogently explained by a far more available inference; that the end products are biosimilar. That fact does not suggest similarity of process.

Fifth contention: Pfizer Process falls within the claims

98 This then leads to the fifth aspect of Pfizer’s submission, which is that the similarities demonstrated in the Cho article permit the inference that the BRENZYS Process is similar to the Pfizer Process and, as the Pfizer Process falls within the relevant claims, it may be inferred that so too does the BRENZYS Process.

99 Each part of this reasoning confronts hurdles.

100 The initial hurdle is to establish a basis for inferring that the BRENZYS Process and the Pfizer Process may be the same or similar. In this regard it is to be noted that Pfizer makes no submission that SBK had access to its own process. To the contrary, the Pfizer Process is confidential. The only means by which it might be inferred that the Pfizer Process was emulated is if SBK had regard to the patents. Yet Pfizer makes no submission that the BRENZYS Process uses any aspect of phases (a), (c) or (d) of the Pfizer Process in making etanercept. There is no basis for inferring that it does. The inference is nevertheless sought that there is a similarity between phase (b) of the BRENZYS Process and phase (b) of the Pfizer Process.

101 Next, Pfizer relies on the evidence of Dr Ibarra that the Pfizer Process falls within the claims in issue. This is a central part of Pfizer’s reasoning, because without it (as I explain further below) there is no basis at all upon which it might be inferred that there is any relationship between the claims asserted and the BRENZYS Process.

102 Objection was taken to several parts of the evidence of Dr Ibarra insofar as she addressed the question of whether or not the Pfizer Process fell within the asserted claims of each of the patents. Although the evidence that was the subject of objection extended to a number of paragraphs, the parties accepted that some examples would suffice for the purpose of ruling as to its admissibility. During the course of the hearing I heard argument on the subject and, at the parties’ suggestion, deferred ruling on the matter until delivery of my reasons. I divert now to consider the question of the admissibility of this evidence.

103 In her first affidavit of 5 January 2017, Dr Ibarra said (emphasis added):

45. As part of my work described above, I have observed that, since 2007, Wyeth Ireland, and then Pfizer Ireland, has manufactured the etanercept for ENBREL® using a serum-free process; that is, a process that uses chemically defined media, and that does not contain foetal bovine serum (the Current Pfizer Process). The Current Pfizer Process has at all times fallen within at least claim 1 of each of the Etanercept Patents.

104 Words to similar effect to those underlined appear elsewhere in Dr Ibarra’s first affidavit. On 6 February 2017 Dr Ibarra affirmed a further affidavit during which she said (emphasis added):

9. I refer to the first two columns of Annexure NI-12 of My First Affidavit, and confirm that I am aware, based upon my personal observations of the Current Pfizer Process in the course of my work, that the Current Pfizer Process has each of the features identified in that table as integers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 of claim 1 of the ‘034 Patent.

105 Dr Ibarra gave similar evidence for each of the 036 and 632 patents. After objection was taken to that evidence, she affirmed a further affidavit on 8 February 2017 in which she referred to her third affidavit of 6 February 2017, gave some evidence as to how she construed some terms within the patents (by reference to the body of the specification) and then gave evidence as to her opinion as to the presence of certain integers. In the context of the 632 patent, her additional evidence also addressed integer 4 of claim 1 and said:

15. I am aware, based upon my personal observations of the Current Pfizer Process in the course of my work, that in the Current Pfizer Process, the etanercept for ENBREL® is produced in a cell culture where the cells are grown at a temperature in a range of 27.0˚C to less than 30.0˚C, and at a pH in a range of 6.80 to less than 7.00, and misfolded proteins and/or aggregated proteins are measured at less than 25% (see also page 1143 in the Cho paper annexed as NI-11 to my First Affidavit, which reports 13.5% to 13.6%) of the protein produced.

106 SBA objects to the relevant portions of Dr Ibarra’s evidence on the basis that it is bare assertion and is inadmissible pursuant to s 76 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) and the principles expressed in Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCS 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705 (Makita) and that, if admitted, it should carry no weight. Dr Ibarra, SBA submits, has not identified the facts and assumptions upon which her opinion is based and no facts or assumptions or details of the Pfizer Process have otherwise been put into evidence. Further, Dr Ibarra does not explain how she has construed the claims of the patents.

107 Pfizer submits first, that the evidence the subject of the objection was not opinion evidence at all but a statement of fact as to the presence of physical features of the process. Dr Ibarra’s intimate experience with the process as a result of her employment enabled her to state matters of fact. Secondly, that s 76 of the Evidence Act does not apply to applications of the present type because the task of the Court is not to determine questions of fact on a binding basis Optiver Australia Pty Ltd v Tibra Trading Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1560; (2007) 163 FCR 554 (Optiver Australia) per Tamberlin J at [4]. Thirdly, that the Court should, in any event, dispense with the application of s 76 of the Evidence Act pursuant to the operation of s 190 of that Act; citing Dallas Buyers Club LLC v iiNet Limited [2015] FCA 317; (2015) 112 IPR 1 (Dallas Buyers Club) at [96] – [99] and Optiver Australia at [22].

108 Claim 1 of each of the three patents-in-suit is set out above. Each of these claims appears in patents going to highly technical subject matter. In my view, it is plain that matters of interpretation and opinion are required to form the view that a particular process falls within the claim. Taking the 632 patent as an example, integer 2 involves “growing cells in the cell culture at a reduced temperature, wherein the reduced temperature is in a range of 27.0˚C to less than 30.0˚C” involves an evaluation of the length of time at which the reduced temperature is sustained – is it the entire period of cell growth or something else? The same may be asked in respect of “reduced pH” in integer 3. Integer 4 plainly involves an evaluation, as senior counsel for Pfizer accepted. Dr Ibarra’s 8 February 2017 affidavit addressed this last point, but not integers 2 or 3. In relation to the 034 patent, integer 10 involves an evaluation and opinion as to what is within 20 – 80% of the “maximal possible viable cell density”. Integer 11 involves an evaluation as to what difference is sufficient to amount to “changing at least one of the culture conditions”. Dr Ibarra’s 8 February 2017 affidavit addressed integer 10 only.

109 Patent cases are replete with examples of terms and patents being the subject of nuanced contention based on the opinion of experts in the field in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed as at the priority date.

110 I am of the view that the paragraphs the subject of objection do constitute opinions which fall within s 76 of the Evidence Act. The principles for giving of opinion evidence apply.

111 Further, Dr Ibarra is giving her opinion that certain facts, being the constituent parts of the Pfizer Process, satisfy the requirements of the claims in issue. Nowhere does Dr Ibarra identify the particular facts that she observed that form the foundation of her opinion. Nor have they been the subject of evidence elsewhere. Instead, Pfizer submits that the integers of each of the claims were themselves identified facts, and that her evidence does no more than to confirm, as a result of her own observations, that those facts are met having regard to her own experience with the Pfizer Process.

112 In Makita at [64] what is expressed to be the basal principle is that what an expert gives is an opinion based on facts. Because of that, the expert must either prove by admissible means the facts on which the opinion is based, or state explicitly the assumptions as to fact on which the opinion is based (at [64]). At [85] Heydon JA (as he then was) observed that so far as the opinion is based on facts “observed” by the expert, they must be identified and admissibly proved by the expert. If it is not, it is not possible to be sure whether the opinion is based wholly or substantially on the expert’s specialised knowledge.

113 In Dasreef Pty Limited v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21; (2011) 243 CLR 588 (Dasreef) at [37], the plurality endorsed the following statement from Makita (at [85]):

… [T]he expert’s evidence must explain how the field of “specialised knowledge” in which the witness is expert by reason of “training, study or experience”, and on which the opinion is “wholly or substantially based”, applies to the facts assumed or observed so as to produce the opinion propounded.

114 Accordingly, I would not be disposed to admit the paragraphs identified in SBA’s objection unless s 76 of the Evidence Act is found not to apply or an exception to the opinion rule set out in s 76 of the Evidence Act is found to apply.