FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft v Generic Health Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 250

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and submit agreed short minutes of order reflecting these reasons for judgment within 14 days, including directions if the issue of costs is not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

THE CLAIMS

1 The applicants (referred to below together as Bayer and separately as Bayer AG and Bayer Australia) claim damages against the respondents (together, Generic Health) for patent infringement.

2 In the reasons for judgment in Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 279; (2013) 100 IPR 414 (the principal decision) I found that Generic Health had infringed claims 3 and 11 of Australian Patent No 780330 for a pharmaceutical combination of ethinylestradiol (EE) and drospirenone (DRSP) for use as a contraceptive. Pursuant to the patent, Bayer manufactured and sold in Australia the oral contraceptive known as Yasmin. Generic Health infringed the patent by manufacturing and selling the oral contraceptive known as Isabelle. I made orders on 8 May 2013 which included the following, but which were stayed pending the outcome of a foreshadowed appeal:

3. Generic Health (whether by itself, its directors, officers servants, agents or howsoever otherwise) be restrained from infringing claims 3 and 11 of the Patent by importing, selling, supplying, and offering to sell and supply the Isabelle Product (or keeping it for any such purpose) in Australia during the term of the Patent without the licence or authority of the Applicants.

4. Lupin (whether by itself, its directors, officers servants, agents or howsoever otherwise) be restrained from authorising any person to exploit the invention claimed in claims 3 and 11 of the Patent by importing, selling, supplying, and offering to sell and supply the Isabelle Product (or keeping it for any such purpose) in Australia during the term of the Patent without the licence or authority of the Applicants.

…

7. Generic Health and Lupin pay to the Applicants damages (including additional damages pursuant to section 122 (1A) of the Patents Act 1990, if any) or, at the Applicants' option, an account of profits, to be assessed pursuant to the procedure contemplated in order 10(a) or order 10(b).

3 A subsequent appeal was dismissed (Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; (2014) 222 FCR 336), as was an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court (Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] HCATrans 261).

4 Bayer elected for damages rather than an account of profits. Bayer’s total claim is for damages of $25,751,336 plus interest. This claim is based on an assessment of Bayer’s lost profits in which each sale of Isabelle and of Petibelle, a generic version of Yasmin which Bayer introduced after Isabelle was removed from sale, is taken to be a lost sale of Yasmin. Bayer’s lost profits are based on its standard costings for the production and sale of Yasmin including for determining its fixed and variable costs.

5 Generic Health contends that this amount would over-compensate Bayer on the grounds that:

(1) Section 115(1)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Patents Act) precludes any award of damages to Bayer for any infringements before 14 December 2012 (the date on which the patent was amended) because Bayer has not satisfied the Court that its original specification, before amendment, was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge as required by that provision. The parties referred to this as the good faith issue.

(2) It should not be found that each sale of Isabelle and of Petibelle is a lost sale of Yasmin. At least some, and perhaps a substantial number, of sales of Isabelle were not in substitution for Yasmin. Further, the claim for damages in respect of Petibelle should be rejected based on the requirements of causation and remoteness of damage and, if maintainable at all, would relate to a relatively short period of time, measured in months not years. The parties referred to this as the one for one issue.

(3) Bayer’s standard costings should not be applied without also applying a discount for the risk that Bayer’s costs in producing the additional number of Yasmin tablets for sale would have been greater than the standard costings contemplate. The parties referred to this as the costings issue.

THE BASIC FACTS

6 The basic facts are not in dispute.

7 Yasmin was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (the ARTG) on 6 July 2001 and first sold in Australia in August 2002.

8 In September 2008 Bayer launched its Yaz oral contraceptive and diverted its marketing efforts from Yasmin to Yaz. Yaz is also based on a combination DRSP and EE, but the amount of EE in Yaz is less than in Yasmin and is in a different form. As a result, Yaz is not suitable for all women because the lesser amount of EE may give insufficient cycle control, which I infer is one reason that Yasmin remained (and remains) on the market.

9 On 8 April 2011 Bayer obtained a registration on the ARTG for Petibelle, a generic version of Yasmin, but did not put Petibelle on the market.

10 In October 2011 the Therapeutic Goods Administration (the TGA) issued a safety update to the effect that Yasmin may be associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to other combined oral contraceptives.

11 On 23 January 2012 Generic Health started to sell Isabelle in Australia in packets of 3 x 28 tablets. Isabelle was registered on the ARTG on the basis of bioequivalence to Yasmin.

12 On 15 February 2012 Bayer commenced this proceeding against Generic Health and applied for an amendment of the patent.

13 In February 2012, the initial stocks of Isabelle ran out and could not be replenished to fill back orders until around March/April 2012. Stocks of Isabelle ran low again in May 2012 and were not replenished until August 2012.

14 In September 2012 Bayer launched Yaz Flex and diverted its marketing efforts from Yaz to Yaz Flex. Yaz Flex is the same formulation as Yaz.

15 On 14 December 2012 Yates J allowed the amendment of the patent (Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft v Generic Health Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 1510; (2012) 99 IPR 59 (referred to below as the amendment decision).

16 On 19 June 2014, after the appeal from my orders was dismissed, Generic Health was required to cease selling Isabelle immediately and did so.

17 On 26 June 2014 Bayer started to sell Petibelle in Australia. Bayer did not market Petibelle other than by a letter dated 20 June 2014 to doctors and pharmacists informing them of the availability of Petibelle.

THE GOOD FAITH ISSUE

Statutory provisions

18 Section 115(1) of the Patents Act provides that:

(1) Where a complete specification is amended after becoming open to public inspection, damages shall not be awarded, and an order shall not be made for an account of profits, in respect of any infringement of the patent before the date of the decision or order allowing or directing the amendment:

(a) unless the court is satisfied that the specification without the amendment was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge; or

(b) if the claim of the specification that was infringed is a claim mentioned under subsection 114(1).

19 Section 115, in terms, qualifies the power of the Court under s 122(1) of the Patents Act which is as follows:

The relief which a court may grant for infringement of a patent includes an injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the court thinks fit) and, at the option of the plaintiff, either damages or an account of profits.

20 Bayer does not press its claim for additional damages to be awarded under s 122(1A).

The amendments

21 In the amendment decision Yates J described the amendments at [24] in these terms:

The amendments, as they relate to claims 3, 11, 27 and 32:

(a) limit the dosage of drospirenone to 3 mg (the 3 mg feature);

(b) confine the composition or preparation to a tablet form (the tablet feature); and

(c) specify that the stated dissolution test is performed in 900 ml of water (the 900 ml feature).

22 The amendments to claims 3 and 11 of the patent which Yates J allowed on 14 December 2012 were as shown below:

3. A pharmaceutical composition in oral dosage form comprising;:

from 2 mg to 4 mg 3 mg drospirenone and 0.01 mg to 0.05 mg of ethinylestradiol, together with one or more pharmaceutically acceptable carriers or excipients, wherein the oral dosage form is a tablet, and

wherein at least 70% of said drospirenone is dissolved from said composition within 30 minutes, as determined by USP XXIII Paddle Method II using 900 ml of water at 37°C as the dissolution media and 50 rpm as the stirring rate.

…

11. A pharmaceutical preparation consisting of a number of separately packaged and individually removable daily dosage units placed in a packaging unit and intended for oral administration for a period of at least 21 consecutive days, wherein said daily dosage units are in tablet form and comprises a combination of 3 mg of drospirenone in an amount of from 2 mg to 4 mg and ethinylestradiol in an amount from 0.01 to 0.05 mg, wherein at least 70% of said drospirenone is dissolved from said dosage units within 30 minutes, as determined by USP XXIII Paddle Method II using 900 ml of water at 37°C as the dissolution media and 50 rpm as the stirring rate.

Principles

23 I accept many of the principles the parties proposed ought to be applied in resolving the issue whether I should be satisfied that “the specification without the amendment was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge”, with the consequence that “damages shall not be awarded in respect of any infringement of the patent before” 14 December 2012, the date of the decision allowing the amendment of the patent.

24 I accept that the onus of proof lies on Bayer to satisfy the Court that the “specification without the amendment was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge”. I do not accept Bayer’s submission that, as a principle of general application, good faith and reasonable skill and knowledge “is to be assumed in the patentee’s favour in the absence of internal or external evidence to the contrary”. The submission is based on an observation of Greene MR during the course of argument in Molins and Molins Machine Co Ltd v Industrial Machinery Co Ltd (1938) RPC 31 at 33. While it may be that the absence of internal or external evidence makes it appropriate to infer good faith and reasonable skill and knowledge having regard to all of the circumstances of the particular case, the exercise is one of inference, and not of assumption.

25 In common with Windeyer J in Pracdes Pty Ltd v Stanilite Electronics Pty Ltd (1995) 35 IPR 277 at 281, I do not consider General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1975] RPC 203 to stand for any contrary proposition. A number of important propositions were made in General Tire but they do not include a suggestion that under the equivalent provision in the UK (which is not in identical terms to s 115(1) of the Patents Act) the patentee did not bear the onus of proof. That said, a number of the observations in the Court of Appeal’s reasons in General Tire at 269-270 are relevant to the Australian context:

(1) It is not the case that the drafter of the patent necessarily must be called in order to discharge the onus of proof.

(2) “If a patent agent puts forward something of which he has no knowledge, which suffers from some fatal imperfection in the patent field we do not consider that, when the patent office accepts it without demur, it can be said that it was framed otherwise than in good faith. It is, after all, the function of a patent agent to argue in honesty for the width of the application”.

(3) “It is to be observed that the withdrawal of a claim does not necessarily involve that admission that that claim cannot be or could not ever have been sustained as valid. It is common practice to include in good faith a wider claim so as to have the benefit of a wider search in the Patent Office. It is also common practice for an applicant to decide that in terms of commerce a narrower claim suffices, and therefore to drop a wider claim which will not serve him commercially and may land him in opposition litigation. On the question of good faith it is not to be expected that the patentee should in evidence first raise up and then exorcise the ghost of every possible defect in the unamended claim: if he destroys the defects that are suggested, that suffices”.

26 This latter proposition must be right. If there is no suggestion that an unamended specification has been framed other than in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge, the onus does not mean that the patentee must adduce evidence attempting to guess in which respect it might be alleged that the court should not be satisfied under s 115(1)(a).

27 I accept also that by the terms of s 115(1)(a) it is the specification as a whole without the amendment which must be framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge.

28 Given that the framing of the specification in the present case involved work overseas and in Australia, I accept that the statutory question is to be answered considering the framing of the specification as a whole, both overseas and in Australia.

29 I accept that statements in UK decisions need to be understood in the different statutory context there applicable and, in particular, the fact that s 63(2) of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) included a provision that where a patent has been found to be “only partially valid”, the Court should not grant relief by way of damages “except where the plaintiff… proves that the specification for the patent was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge”. There is no equivalent provision in the Patents Act.

30 Nevertheless, I also accept Bayer’s proposition based on Molins at 44 and General Tire at 269 that a patent invalid but for the amendments may nevertheless have been framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge. In Molins the unamended patent would have been invalid for lack of novelty by reason of an earlier patent described at 44-45 as a German document 48 years old at the date when the patent was applied for of which the patentee knew nothing. Greene MR said that if the patentee did not know anything about the prior art then the original claim was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge. This said, it must also be the case that the validity of the unamended specification is at least relevant to the issues of framing in good faith and reasonable skill and knowledge.

31 I do not consider that a further submission of Generic Health may be taken at face value. The submission is this:

Secondly, consistently with s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), in order to meet the s 115(1)(a) test, clear and cogent proof is required. This is because of: (1) the nature of the cause of action – the amendment of a patent claim is an “indulgence to the patentee” (Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 117 IPR 415 at [312] per Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ), and having been granted that indulgence and having then obtained a finding of infringement of the amended patent, a patentee is then able to seek pecuniary remedies for infringement, subject only to the protection afforded by s 115; and (2) the nature of the claim – if Bayer is able to satisfy the s 115(1)(a) test, this is likely to sound in a substantial award of damages for the period before 14 December 2012 (ie millions of dollars).

32 First, given that s 115 is concerned only with monetary compensation for infringement, the size of any particular claim cannot affect the proper principles to be applied. Second, the reference to a need for “clear and cogent proof” may act as an inappropriate gloss on the ordinary civil standard of proof of on the balance of probabilities (s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth)) and the capacity to take into account all relevant matters to determine whether that standard has been met in the particular case (s 140(2) of the Evidence Act). Third, references to the need for “clear and cogent proof” are common in the context of allegations such as fraud. As explained in Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66; (1992) 110 ALR 449 at 449-450 (footnotes excluded):

The ordinary standard of proof required of a party who bears the onus in civil litigation in this country is proof on the balance of probabilities. That remains so even where the matter to be proved involves criminal conduct or fraud. On the other hand, the strength of the evidence necessary to establish a fact or facts on the balance of probabilities may vary according to the nature of what it is sought to prove. Thus, authoritative statements have often been made to the effect that clear or cogent or strict proof is necessary “where so serious a matter as fraud is to be found”. Statements to that effect should not, however, be understood as directed to the standard of proof. Rather, they should be understood as merely reflecting a conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct and a judicial approach that a court should not lightly make a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, a party to civil litigation has been guilty of such conduct.

33 It is not immediately apparent that the context established by s 115(1) of the Patents Act has much in common with an allegation of fraud or other dishonest conduct.

34 Other principles are relevant to the question of proof. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hellicar [2012] HCA 17; (2012) 247 CLR 345 at [250], Heydon J summarised a number of propositions, which Generic Health set out as follows:

(a) In Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65, Lord Mansfield CJ stated:

“It is certainly a maxim that all evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted.”

(b) In Ho v Powell [2001] NSWCA 168; (2001) 51 NSWLR 572 at [14]–[15] Hodgson JA stated:

“in deciding facts according to the civil standard of proof, the court is dealing with two questions: not just what are the probabilities on the limited material which the court has, but also whether that limited material is an appropriate basis on which to reach a reasonable decision...

In considering the second question, it is important to have regard to the ability of parties, particularly parties bearing the onus of proof, to lead evidence on a particular matter, and the extent to which they have in fact done so”.

(c) In Shalhoub v Buchanan [2004] NSWSC 99 at [71] Campbell J stated:

“failure of a party who bears an onus of proof to call an available witness who could cast light on some matter in dispute can be taken into account in deciding whether that onus is discharged, in circumstances where such evidence as has been called does not itself clearly discharge the onus. This is an application of Lord Mansfield's maxim”.

(d) In Cook’s Construction Pty Ltd v Brown & Anor [2004] NSWCA 105; (2004) 49 ACSR 62 at [42], Hodgson JA stated:

“where a party has to prove something and prima facie has available evidence that would directly deal with the question, a court will be very hesitant in drawing an inference in that party's favour from indirect and second-hand evidence, when the party doesn't call the direct evidence that prima facie it could have called, at least unless some explanation is given, or the circumstances themselves provide an explanation”.

35 Further, in Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; (2011) 243 CLR 361 the reasons of Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ at [63] referred to the well-known observations of Handley JA in Commercial Union Assurance Co of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom Pty Ltd (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 at 418-419 as at least being authority for this proposition:

The rule in Jones v Dunkel [(1959) 101 CLR 298] is that the unexplained failure by a party to call a witness may in appropriate circumstances support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case. That is particularly so where it is the party which is the uncalled witness. The failure to call a witness may also permit the court to draw, with greater confidence, any inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness, if that uncalled witness appears to be in a position to cast light on whether the inference should be drawn. These principles have been extended from instances where a witness has not been called at all to instances where a witness has been called but not questioned on particular topics. Where counsel for a party has refrained from asking a witness whom that party has called particular questions on an issue, the court will be less likely to draw inferences favourable to that party from other evidence in relation to that issue. That problem did not arise here. The plaintiff's counsel did ask the plaintiff relevant questions.

36 I adopt Generic Health’s summary in respect of the good faith requirement as follows:

(a) In order to establish the good faith requirement, the plaintiff must prove that the specification was framed honestly with a view to obtaining a monopoly to which, on the material known to him or her, he or she believed he or she was entitled: Hallen v Brabantia [Hallen Co v Brabantia (UK) Ltd [1990] FSR 134] at 143; Chiron Corp v Organon Teknika Ltd [1994] FSR 458 at 467 (English Patents Court) (Chiron v Organon).

(b) The inclusion of something known by the framers of the patent specification to be detrimental to it may be evidence of a lack of good faith: General Tire at 269 per curiam (English Court of Appeal).

(c) The patentee has to establish that in the original specification it “meant and intended to claim that which [it] had invented and no more. I will not say that that is an exclusive definition, but that is an illustration”: Kane [Kane and Pattinson v J Boyle & Co (1901) 18 RPC 325] at 338.

37 I adopt also Generic Health’s summary in respect of the reasonable skill and knowledge requirement to the following extent (which excludes statements I consider to be no more than the result of the particular facts of the case):

(a) The words “reasonable skill and knowledge” require the specification as framed to be in the form in which a person, with reasonable skill in drafting patent specifications and a knowledge of the relevant law and practice, would produce given the patentee's knowledge of the invention: Chiron v Organon at 467-468.

(b) Where the draftsperson was not properly instructed, the “patentee cannot be in a better position than the patentee who properly instructs the draftsman”: Chiron v Organon at 468.

…

(d) Any mistake must be considered in the context of the whole specification, making allowance for any difficulty the drafter had and the importance of the passage containing the mistake: Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd. & Ors v Kirin-Amgen Inc. & Ors [2002] EWHC 471 at [84]-[85], [87]-[89] (English Patents Court) (Kirin-Amgen (EPC) affirmed by the Court of Appeal in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Transkaryotic Therapies Inc [2002] RPC 31) (English Court of Appeal) (Kirin-Amgen (UKCA))).

(e) In Kirin-Amgen (UKCA) at [151]-[152], the UK Court of Appeal held that the relevant knowledge must encompass the knowledge of the person that formed the basis of the information in the specification. Thus where a specification contained an obvious mistake due to work done by a contractor, however skilled, the patentee had to shoulder the burden of establishing that the specification was framed with reasonable skill and knowledge.

38 Otherwise:

(1) I agree with Generic Health that the issue under s 115(1)(a) does not involve an exercise of discretion but is a question of fact – whether in all of the circumstances the court is satisfied that the specification without the amendment was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge.

(2) The parties must be right that the patentee will not always need to call evidence from people involved in the drafting of an unamended specification. As Generic Health put it:

…the extent to which it is necessary to adduce evidence from those involved in drafting the pre-amendment specification depends on the circumstances of the case.

(3) It must also be right that the mere fact that those involved in drafting the unamended specification give evidence does not necessarily discharge the onus of proof. Again, as Generic Health put it:

… there are also cases in which the onus has not been discharged in circumstances where: (1) the patentee and the draftsperson have been called to give evidence (see e.g. Pracdes … and Rediffusion Simulation Ltd v Link-Miles Ltd [1993] FSR 369 at 381-385); and (2) where the draftsperson has been called to give evidence, and their instructions were also in evidence (see eg Ronson Products Ltd v Lewis & Co [1963] RPC 103). There is no “well-settled” principle on who should or should not be called to give evidence. That matter is heavily fact-dependent.

The earlier decisions

39 To the extent Bayer contended that Generic Health was estopped by the amendment decision from alleging that Bayer had not discharged its onus of proof under s 115(1)(a) of the Patents Act, I disagree. As Generic Health submitted, the amendment decision was not concerned with the question posed by s 115(1)(a). Justice Yates did not express any concluded view on the validity of the unamended claims of the patent (at [28]). Nor is it clear that his Honour’s conclusion that Bayer was not precluded from obtaining the amendment by reason of “covetous claiming” involved an essential finding on which his allowance of the amendment depended so as to give rise to an issue estoppel (Blair v Curran (1939) 62 CLR 464 at 532; see also EI Du Pont de Nemours & Co v Imperial Chemical Industries PLC [2007] FCAFC 163; (2007) 163 FCR 381 at [86]).

40 This said, the position of Bayer before Yates J is not irrelevant to the s 115(1)(a) issue. At [221] his Honour recorded that:

Bayer Pharma does not concede that, without amendment, the dissolution test claims of the Australian patent would not be fairly based on the matter described in the specification. Without deciding that question, I have accepted that Bayer Pharma’s stated position in that regard is one that is genuinely held by it on grounds that appear to be capable of being argued objectively and reasonably.

41 Given that finding, it would not be unreasonable to expect that if Generic Health, a party to the amendment decision, wished to assert in this proceeding that Bayer did not genuinely hold such a view it would take such evidentiary opportunities as were available to it to lay the foundation for that contrary proposition. As explained below, Generic Health did not do so.

42 Further, it is also not irrelevant that Yates J rejected an argument that Bayer had engaged in “covetous claiming”. As Yates J explained at [215]:

In the context of amendment applications, the notion of “covetous claiming” is properly understood as the deliberate obtaining or maintenance of patent claims where the patentee knows that those claims are of unjustified width…

43 At [218] (noting that Eremad Pty Ltd, like Generic Health, opposed the amendments) his Honour said:

I do not find it to be exceptionable that a patentee or patent applicant would seek to keep the scope of its patent claims as broad as possible in order to fully protect its invention as it perceives it to be. Similarly, I do not find it to be exceptionable that, for pragmatic reasons, a patentee or patent applicant might be prepared to compromise on, and resile from, its desired position and not seek to vindicate to the fullest its patent rights or entitlements, as it perceives them to be. The question is whether, in so doing, the patentee or patent applicant, improperly, has sought to prosecute or maintain claims of unjustified width. Contrary to the implication in Eremad’s submissions in this vein, I do not regard Bayer Pharma’s conduct, as revealed by the evidence, to involve it seeking to prosecute or maintain claims which it knows to be either impermissibly or indefensibly wide. In my view, none of the material relied upon by Eremad in this regard shows any untoward or inappropriate conduct on the part of Bayer Pharma which, on the present state of the evidence, would warrant criticism of Bayer Pharma by the court.

44 Test the proposition of irrelevance this way. Assume Yates J had found that Bayer engaged in covetous claiming. It is not difficult to imagine that Generic Health would have relied on that finding to support its case that the unamended specification was not framed in good faith. The fact that his Honour was asked but refused to make that finding is also potentially relevant to the s 115(1)(a) issue. Again, given the finding of no covetous claiming by Bayer in the amendment decision, if Generic Health wished to assert in this proceeding that Bayer had engaged in covetous claiming and for that reason had not framed the unamended specification in good faith, it would not be unreasonable to expect Generic Health to have taken such evidentiary opportunities as were available to it to lay the foundation for that proposition. And again, as explained below, Generic Health did not do so.

45 This said, Generic Health must also be right that the tests for “covetous claiming” and the requirement of good faith under s 115(1)(a) are not the same, so that the finding of Yates J cannot be taken to be a finding that the unamended specification was framed in good faith. Good faith is a broader concept than “covetous claiming”, not the least by reason of the compelling force of the observation in WAFV of 2002 v Refugee Review Tribunal [2003] FCA 16; (2003) 125 FCR 351 at [52] that “bad faith is not necessarily the obverse of good faith. Good faith requires more than the absence of bad faith”.

46 I also agree with Generic Health that its case under s 115(1)(a) does not involve an illegitimate attempt to re-argue the lack of fair basis case which was rejected in the principal decision. As Generic Health submitted, the principal decision concerned only the validity of the amended claims, not the unamended claims. Again, this said, I do consider that Generic Health’s submission that various circumstances related to the earlier decisions are irrelevant considerations, which can carry no probative value in resolving the issues under s 115(1)(a), goes too far.

47 Accordingly, it is not necessarily irrelevant that Generic Health did not challenge the unamended claims on the ground of lack of fair basis when it had the opportunity to do so and otherwise did challenge the claims. For example, depending on all of the circumstances, this fact may tend to support a finding that it was by no means obvious to any person, let alone to Bayer, that the unamended claims were invalid for lack of fair basis. For the same reason, the lack of any objection to the patent during Patent Office examination procedures is not necessarily irrelevant merely because “the test for fair basis (or the overseas equivalent) is different from the s 115(1)(a) test”. What Generic Health is right about is that these factors are not relevant by reason of any discretionary consideration. There is no discretion under s 115(1)(a) and thus Generic Health’s culpability or otherwise in entering the market knowing of the patent, and of the proposed amendments, is immaterial. These factors and others like them may be relevant, because they may tend to prove or disprove the relevant question of fact – whether the specification without the amendment was framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge. Beyond this, the language of relevant and irrelevant considerations is not well adapted to the issue to be resolved, because questions of fact usually involve the drawing of or refusal to draw inferences having regard to the entire evidentiary matrix.

Australian patent attorneys – common ground

48 With two reservations, I accept that the evidence given by the Australian patent attorneys, Dr McCann and Ms Sinclair, about the functions of a patent attorney provides a useful context for the assessment of the issues under s 115(1)(a) of the Patents Act.

49 The first reservation is this. The specification does not state that side effects will be avoided at the maximum dosage level. It says:

it has surprisingly been found that a hitherto undisclosed minimum dosage level of drospirenone is required for reliable contraceptive activity. Similarly, a preferred maximum dosage has been identified at which unpleasant side effects, in particular excessive diuresis, may substantially be avoided.

50 To the extent that Ms Sinclair’s evidence assumed, or was to the effect, that the patent promised that side effects would be avoided at the maximum dosage level, I disagree. The use of “may” and “substantially” in this part of the specification qualifies the promise. Side effects may substantially be avoided, no more and no less.

51 The second reservation is this. In the principal decision I concluded that the skilled addressee would read the dosage range of 2 to 4mg of DRSP as subject to the accepted variance in quantities for pharmaceutical products as in force at the priority date (at [104]). The accepted variance was ± 7.5% (at [102]).

52 Subject to this, I generally accept many of the submissions of both parties about the effect of the evidence of Dr McCann and Ms Sinclair about the functions of a patent attorney. The following propositions, which I accept, are based on and adopt parts of those submissions.

53 Patent drafting is a collaborative process between the inventors or client and the patent attorney, who each bring different skills and information to the process. As Ms Sinclair said, the drafting of a patent is a “balancing act” between the commercial, legal and technical position of the patent applicant. As Dr McCann said, claim drafting involves an exercise in judgment as to how broadly an invention can be defined.

54 It is common for patentees to seek to claim a range of the dosage of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

55 With respect to technical matters such as the appropriate dosage range for a pharmaceutical it is typical and reasonable for a patent attorney to rely on information provided to him and her by the inventor/client. That is not to say that a patent attorney will “simply parrot the instructions one is given” and, as Ms Sinclair said, instructions should be reviewed “with a critical eye to make sure that they’re not going to potentially cause issues in the future”. However, there is no doubt that a patent attorney also, as Dr McCann said, must:

rely on the client because they have the expertise. You have the scientific background, but they have the detailed expertise, and so you have to rely heavily on the client. That’s usually the case…

56 When a range is claimed, the patent attorney expects that the client will have a sound basis for an honest belief in the range claimed. The belief may be based on experimental evidence or a plausible expectation of the skilled addressee that the invention would work throughout the range defined. Ms Sinclair’s conventional practice is to try to understand whether any trial data meets this objective and, in the event of doubt, she “would go back to my client and ask the question of whether or not they wanted to include that within the range, given that it may have legal consequences at a later date if they did”. Similarly, Dr McCann considered it prudent for a patent attorney to “understand fully the appropriate width of the invention”. As he put it, “somebody” had to form the “state of mind” necessary to establish a “reasonable or sound basis” for a “prediction” that an outer limit of a range has the “appropriate properties” of the invention. However, generally, that is for the client as it is not up to a patent attorney, when drafting a patent specification, to make “sound predictions” of a technical nature unless they have particular technical expertise in a specific area,

57 I take from this evidence that it necessarily follows that the concepts of reasonable skill and knowledge are to be assessed, recognising that competent practice and the application of reasonable skill and knowledge to the framing of a specification as a result of the interactions between patent attorney and client themselves involve a range. The standard set by s 115(1)(a) for the framing of the specification is one of reasonable skill and knowledge, not the highest possible level of skill and knowledge on the part of either the attorney or the client.

58 Dr McCann and Ms Sinclair are highly experienced patent attorneys.

59 Dr McCann has been a registered Australian patent and trade mark attorney since 1988 and currently is the lead lecturer for three patents related subjects in the Master of Intellectual Property at the University of Technology, Sydney. He has worked in the patents area since 1982 first as a technical assistant and then as a principal of Spruson and Ferguson, a patent and trade mark attorneys firm in Sydney. Before this, he worked as a research and development chemist. He holds a PhD completed in 1979, his PhD thesis focusing on photoelectrochemistry. After he completed his PhD he worked as a research associate primarily in the field of photoelectrochemistry at semiconductor electrodes.

60 Ms Sinclair holds a Bachelor of Science majoring in organic chemistry. She has been registered as a patent attorney in Australia since 1994. She is currently a principal of Watermark Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys. She has been an Examiner for the Professional Standards Board for Patent and Trade Marks Attorneys in the subject Patent Systems. She has also been a Fellow of the Academy of Education of the Institute of Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys. Since 2013 she has been a Senior Fellow in the Faculty of Law, University of Melbourne, and teaches aspects of the course Patent Practice and Interpretation and Validity of Patent Specifications. She was appointed to the Professional Standards Board for Patent and Trade Marks Attorneys for two terms between 2008 and 2013.

61 Given the high levels of expertise of Dr McCann and Ms Sinclair, including that of Dr McCann as a research and development chemist, it is not necessarily the case that the standards they apply to their own practice (that is, their answers to question of what they would consider or might do) set the boundaries of competent practice for a patent attorney. If anything, their personal practices are likely to exceed the minimum standards of competence.

The 2-4mg range

Generic Health’s case

62 According to Generic Health, the documents discovered by Bayer do not disclose what occurred in respect of the selection of the dosage range of 2-4mg of DRSP in the unamended specification (subsequently amended to 3mg of DRSP). Dr Broesamle (an internal witness called by Bayer) has remained silent about the selection of the 2-4mg dosage range, and Dr Ulrich, who worked with Dr Broesamle and was involved in communications with the European patent attorneys, Plougmann and Vingtoft (P&V), has not given evidence. Given the lack of explanation of the documents and their ambiguity, no inference that might be drawn in Bayer’s favour from the face of the documents should be drawn. As Generic Health put it:

The “most natural inference” when a party fails to obtain evidence in chief from a witness on a topic is “that the party fears to do so” because it “would have exposed facts unfavourable to the party”: see eg Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v ACCC (2007) 162 FCR 466 at [230] (Weinberg, Rares and Bennett JJ); in Zaccardi v Caunt [2008] NSWCA 202 at [27] per Campbell JA (Allsop P (as his Honour then was) and Barr J agreeing); Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia Limited v Ferrcom Pty Limited (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 at 418E per Handley JA. That form of inference has frequently been drawn by this Court. Indeed, as has been quoted with approval in Ferrcom at 419 per Handley JA and by the Full Court in Braverus Maritime Inc v Port Kembla Coal Terminal Ltd [2005] FCAFC 256 at [160] (Tamberlin, Mansfield and Allsop JJ),

“the omission to interrogate a friendly witness in respect to facts presumably within his knowledge is more significant than the failure to call such a person as a witness, and that the presumption that the testimony would not have been favourable to the party’s case is stronger than the one which arises from the failure to produce such a person as a witness.”

Given the sparse evidence in chief provided by Dr Broesamle concerning the framing process, the Court should draw an inference that such evidence as he could have given would not have assisted Bayer.

Further, given: (1) Dr Broesamle’s silence in his evidence-in-chief, including with respect to the Broesamle Notes, the other documents in evidence in respect of whom the author has not been identified and the framing process generally; (2) that matters concerning the framing process are peculiarly within Bayer’s knowledge; and (3) that matters concerning the framing process may have more readily been addressed by witnesses who did not give evidence (including, perhaps, Ms Ulrich), no criticism can be levelled at Generic Health for not cross-examining Dr Broesamle on his recollection of the framing process or the various documents before the Court: Ozecom v Hudson Investment Group [2007] NSWSC 1441 at [56].

63 As such, there is (said Generic Health) an “evidentiary vacuum” about the 2-4mg range. Given that “Generic Heath’s power to contradict the version of events put forward by Bayer depends wholly on, and is constrained by, the documents, and witnesses, that Bayer has put forward”:

… the forensic difficulties lie with the party bearing the onus of proof; it is a “legal error” to attempt to place at the other party’s “doorstep” the “difficulties flowing” from the evidentiary vacuum: McHugh v Australian Jockey Club Ltd (2014) 314 ALR 20 at [20] per Perram J, White J agreeing.

64 According to Generic Health, amongst other things:

(1) The documents produced by Bayer are ambiguous and incomplete. In particular, a “fax with details regarding DRSP” sent by Ms Ulrich between 17 March 1999 and 26 August 1999 – a potentially important document given the chronology set out above – is not in evidence

(2) There is no evidence that Bayer had relied upon any testing for dosages above 3mg for the purposes of formulating the patent specification.

(3) There is no evidence that the framers of the patent at P&V were advised by Bayer personnel that the therapeutically effective range for DRSP was 2 to 4mg or that relevant Bayer personnel formed a state of mind that there was a reasonable or sound basis for this dosage range.

(4) There is nothing to suggest that a report known as the 9274 report was considered in the process of framing the specification for the patent.

(5) The documentary record indicates a concern within Bayer as to whether side effects could be avoided at a dosage range of 4mg of DRSP.

(6) The evidence indicates Bayer’s doubts about the efficacy of the dosage amount of 2mg of DRSP.

Evidentiary assessment

65 In deciding questions of proof, context is critical. It is not possible to weigh up the capacity of a party to adduce evidence or whether the evidence that has been adduced is an appropriate basis upon which to reach a reasonable decision that the burden of proof has been discharged, without understanding the context. Aspects of the evidence, particularly but not exclusively those which are not in dispute, provide important contextual information in this case which assist in a rational assessment of issues of proof.

66 Generic Health’s submissions gloss over certain important matters and, as a result, present an unrealistic picture of the kind of evidence which Bayer might have adduced. It is necessary that those important matters be identified.

67 First, Bayer is a large international pharmaceutical group which manufactures, distributes and markets a range of pharmaceutical products across many countries including Australia. Yasmin, for example is manufactured in Germany by Bayer AG and marketed in Australia by Bayer Australia. The Bayer group of companies includes Schering AG following a merger in 2006.

68 Second, and as a result of the first proposition, in his former role as Senior Patent Counsel employed by Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH (and formerly by Schering AG) Dr Broesamle was responsible for the managing, filing and prosecution of “a significant number of patents within [Bayer’s] patent portfolio around the world”, one only of which was International Patent Application No PCT/ICB00/01213 filed on 31 August 2000 (the PCT application) from which the patent took its priority date and which included the claims which were subsequently amended.

69 Third, Dr Broesamle was a highly qualified chemist and patent attorney well before the PCT application was prepared. He holds a PhD completed in 1983 and had worked as a patent attorney at Schering AG since November 1987. Moreover, since that time his particular responsibility has included fertility control and hormone replacement therapy, with his work in respect of DRSP starting in 1989, 10 years before the PCT application was being prepared.

70 Fourth, to this must be added the fact that Schering AG (and thus, relevantly, Bayer, given the merger between the two entities) had been working with DRSP since 1976. For example, use of DRSP as a diuretic was disclosed in Schering AG patent specification no. DE2652761. Schering AG patent specification no. DE3022337 referred to the “gestagen-like activity of [DRSP] and its consequent utility as a contraceptive agent is described at dosage levels of 0.5-50mg of DRSP per day. It is also noted that the mechanism of action of the compound is very similar to that of the natural corpus luteum hormone progesterone, and that it does not give rise to increased blood pressure…”. Schering AG’s research in respect of DRSP continued with numerous studies and patents involving DRSP thereafter involving numerous dosage ranges for various purposes. Dr Broesamle, as noted, became responsible for this patent portfolio in 1989.

71 Fifth, Dr Broesamle’s job description of Senior Patent Counsel was accurate. Despite Generic Health’s contentions to the contrary about the role of Dr Ulrich, Dr Broesamle’s evidence was consistent. He, not Dr Ulrich, was in charge of the managing, filing and prosecution of Bayer’s patents. Dr Ulrich and he worked as a team but he was senior to Dr Ulrich. As he put it:

…definitely I was, you know, the more experienced ... senior part, because I worked on the drospirenone business from the beginning and Dr Ulrich, she only stepped in here for some years

72 This is consistent with Dr Broesamle’s unchallenged affidavit evidence to this effect:

The final decision concerning any issue in relation to the patent family was…made by me in consultation with … [Bayer’s] Head of Patents and Licensing…

73 He also gave evidence that since 2000 a substantial proportion of his work involved DRSP.

74 Sixth, the claims of the patent were based on those in the PCT application, which was itself based on two priority documents, European and US patent applications, filed on 31 August 1999. The framing of the PCT application and the priority documents on which it was based thus occurred in 1999/2000, some sixteen years ago. In these circumstances, and given the significant number of patents for which he was responsible, the fact that Dr Broesamle could not recall why a letter from P&V was addressed to Dr Ulrich rather than him is to be expected. Consistent with his lack of recall of the circumstances surrounding the letter from P&V to Dr Ulrich in August 2009, Dr Broesamle said in his affidavit of 25 August 2016:

Whilst I remember attending a number of meetings and telephone discussions with P&V in relation to the Yasmin invention, I did not have a clear recollection of attending a meeting on 14 January 1999 or what was discussed at that meeting…

75 Seventh, one thing Dr Broesamle could recall and gave positive evidence about was that he decided to amend the patent because he formed the view that it was desirable to do so for “an abundance of caution” given Generic Health’s challenge to the validity of the patent based on lack of fair basis. The amendments were not sought because of any view that the claims might be invalid. Dr Broesamle repeated this in his oral evidence and it was not put to him that the amendments were sought because Bayer believed the unamended claims were, or might be, invalid.

76 Some other matters also need to be taken into account:

(1) When asked why the letter from P&V sent in August 1999 was addressed to Dr Ulrich, Dr Broesamle could not remember why that might be so. He said he might have been on vacation but rejected the suggestion that his focus might have shifted away from the PCT application and reiterated that he was more senior to Dr Ulrich and Dr Ulrich and he worked as a team. This is consistent with his unchallenged evidence that any “final decision concerning any issue in relation to the patent family was…made by [him] in consultation with … [Bayer’s] Head of Patents and Licensing”.

(2) Generic Health did not challenge Dr Broesamle’s lack of recall of the meeting of 14 January 1999. Nor did it suggest to Dr Broesamle that he had any recollection of any of the “number of meetings and telephone discussions with P&V in relation to the Yasmin invention” which he said he attended. Nor for that matter did it suggest to Dr Broesamle that he had not in fact attended or been privy to a number of meetings and telephone discussions with P&V in relation to the Yasmin invention.

(3) Generic Health did not challenge Dr Broesamle’s status as a highly qualified chemist and patent attorney who, since 1987, was specifically responsible within Schering AG (and then Bayer) for fertility control and hormone replacement therapy and, since 1989, had been involved with Schering AG’s work and had been responsible for its DRSP patents. In the face of unchallenged evidence about his expertise and experience, Generic Health did not suggest to Dr Broesamle that in his role as Senior Patent Counsel he failed himself to act as a competent patent attorney in respect of the framing of the PCT application

(4) In the face of Dr Broesamle’s unchallenged evidence that he considered P&V to be a highly reputable patent attorney firm which, in his experience, had completed all work with a high level of skill and care and in accordance with his instructions and expectations, Generic Health did not suggest to Dr Broesamle that in his role as Senior Patent Counsel he failed to hold P&V to the high standards of competence which he expected from them in respect of the PCT application.

77 Given this, what inferences ought to be drawn? Before this question is answered, it should be said that some other principles, identified by Bayer, are also relevant but appear not to have been given any weight in Generic Health’s contentions.

78 First, a patent is to be construed through the eyes of the skilled addressee. As such, it cannot be said that something has been “omitted” or is “missing” from a patent if the skilled addressee, relying on the common general knowledge, would supply the feature.

79 Second, a patentee is entitled to base a claim on a sound prediction. As Bayer said, referring to Olin Mathieson Chemical Corp v Biorex Laboratories Ltd [1970] RPC 157 at 193:

It is settled that a patentee is free to select the boundaries of its invention and that a selection will be sound and valid provided that a challenger is not able to discharge its onus of demonstrating that the range includes embodiments that are not useful or are old or obvious.

80 Third, it is obvious from the internal Bayer reports discussed below that, as in Asahi Kasei Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha v W R Grace & Co (1991) 22 IPR 491 at 520, we are not dealing with “a field of science where relevant properties suddenly emerge or disappear as a precise numerical point is reached”.

81 Fourth, in NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd (1992) 24 IPR 1 at 27 it was said that:

It is not a legitimate objection that the specification does not disclose the experimental and statistical basis for the chosen STD and e.n values. It does not have to. The obligation of the patentee is to instruct the skilled addressee how to perform the invention. The patentee is not obliged to explain how the invention was made or the theoretical basis underlying any stipulated integer: see Blanco White, Patents for Inventions, 5th ed, 1983, para 4-505.

82 I also accept Bayer’s submission that:

It cannot be a requirement that for a claim to be “framed in good faith and with reasonable skill and knowledge”, the drafter must frame a claim to a higher standard than the Court requires for the claim to be valid.

83 I turn now to certain inferences which I consider should be drawn on the evidence.

84 Dr Broesamle must have been involved in giving instructions on numerous pharmaceutical compositions over many years. Dosage ranges are commonplace in patents for pharmaceutical compositions, as the Schering AG patents involving DRSP before the PCT application was prepared, disclose. The notion that any person, Dr Broesamle or Dr Ulrich or anyone else, could reliably recall instructions to a patent attorney about aspects of one patent application from sixteen years ago would stretch credulity.

85 Given his role and expertise, it is difficult to imagine that Dr Broesamle did not familiarise himself with the research and patents obtained by Schering AG for DRSP when he became involved with the work on DRSP in 1989 or at least before giving instructions to P&V about the priority documents for the PCT application in 1999. While he did not say so expressly, Dr Broesamle himself is a patent attorney and was responsible for all final decisions about the DRSP patent family (in consultation with the Head of Patents and Licensing). As such, I have no difficulty inferring that Dr Broesamle, consistently with the evidence given by Dr McCann and Ms Sinclair about competent patent attorney practice, would have familiarised himself with the information about DRSP available which included all of the earlier Schering AG research and patents. Even if this specific inference is not drawn, as explained below, there are a number of reasons not to assume or infer that Dr Broesamle, as the responsible person, either gave no instructions to P&V or gave instructions knowing nothing of the research which Schering AG had completed before Dr Broesamle requested P&V to prepare the priority documents for the PCT application.

86 Generic Health’s contentions to the contrary are highly improbable once the full context of the evidence is understood.

87 In particular, it cannot fairly be said that Dr Broesamle “has chosen to remain silent on the critical issues in the framing process” when the compelling inference from the full context is that Dr Broesamle could recall only attending numerous meetings and having numerous discussions with P&V about the Yasmin invention and no more. While Dr Broesamle said this expressly about only one meeting, on 14 January 1999, this must be considered with:

his evidence of lack of recollection about the August 1999 letter;

his role in Bayer, as described;

his responsibility for fertility control since 1987;

his work with DRSP since 1989;

his evidence about the substantial number of patent applications for which he was responsible;

the fact that since 2000 the DRSP family of patents (around the world) has been a substantial part of his work;

Generic Health not challenging his expertise, experience, competence, responsibilities, or views about P&V’s high competence and skills as patent attorneys;

Generic Health not challenging the fact that he attended or was involved in numerous discussions with P&V about the PCT application;

Generic Health not challenging his evidence that he did not recall what was discussed at the meeting on 14 January 1999; and

Generic Health not putting to Dr Broesamle its interpretation of notes of apparent meetings and discussions with P&V about the PCT application.

88 When these matters are considered it is apparent that the suggestion that it should be inferred that Dr Broesamle deliberately remained silent about things because his evidence would not have assisted Bayer, is in the realm of far-fetched and fanciful. Moreover, Generic Health never put to Dr Broesamle the proposition that he was effectively withholding relevant evidence from the Court or had deliberately remained silent or recalled more than he had said in his affidavits. Generic Health sought to justify this on the ground that a cross-examiner is only obliged to cross-examine about the evidence a witness actually gives. This may be accepted. But the first problem for Generic Health is that if it is going to be submitted that a witness has deliberately withheld information in evidence or had deliberately remained silent or recalled more than he had said in his affidavits because what he recalled would not assist the case, then at least that proposition must be put. It was not put. The second problem for Generic Health is that the evidence which Dr Broesamle actually gave in this case supports the inference that the reason he did not give evidence about the instructions he gave or what the documents meant was what would be expected in the ordinary course - he had no independent recollection of the framing of one patent application amongst many some sixteen years ago and thus could add nothing useful to the documents themselves which he had located and produced. Indeed, it might be thought that if Dr Broesamle had purported to give evidence about what instructions he gave in 1999 and what documents created in 1999 were intended to mean, such evidence would have been of dubious value given the well-known problems associated with attempts to refresh memory and avoid reconstruction, the latter with its inevitable tendency towards the self-serving no matter the honesty of the witness.

89 In the circumstances identified I do not accept that it was essential for Bayer to have sought leave to adduce further evidence in chief from Dr Broesamle by asking him whether he recalled anything about the preparation of the PCT application other than what was contained in his affidavit. Dr Broesamle was called on the first day of the hearing. Nothing to that time would have suggested to Bayer that Generic Health’s case would involve a contention that Dr Broesamle could give any useful evidence beyond that which he had given in his affidavits but had deliberately remained silent for fear that any evidence he gave, about either his instructions or the documents, would not assist Bayer’s case. That submission was only made in closing by Generic Health. The submission is to be weighed, not only in the context set out above, but also against the fact that Bayer ensured Dr Broesamle was available for cross-examination on his affidavits, which included an affidavit as to discovery, despite the need for Dr Broesamle (who, by the time of the hearing had retired from Bayer) to travel from Germany to do so. To the contrary, in all of the circumstances, the proper inference to be drawn is that Generic Health deliberately did not ask Dr Broesamle anything about his recollection or what the documents (including those he had prepared) meant for fear that Dr Broesamle’s memory might be revived in some respect and Bayer’s case thereby assisted.

90 I also reject Generic Health’s submissions to the effect that I should not draw any inference from any document that might favour Bayer because Dr Broesamle (or others) did not give evidence about the meaning of the document. The fact that the document was created at least 16 or more years ago provides a rational basis for inferring that nothing Dr Broesamle or anyone else could have said about the document would be other than potentially self-serving reconstruction. Further, Generic Health never put to Dr Broesamle, the person who gave evidence, that he was responsible for managing the PCT application and all patents within the DRSP family, any suggestion either that the documents which he had located and produced had any meaning different from that on their face or that he was refraining from giving evidence about any document for fear it would not assist Bayer’s case. As a result, Generic Health’s contentions that I should infer that any evidence that could have been given about various documents would not have assisted Bayer’s case, cannot be accepted. Contrary to Generic Health’s submission, the present case is not comparable to Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals Ltd [2016] FCA 169; (2016) 117 IPR 252. As I noted in Gilead at [515] Idenix did not call any witness who had any involvement in the relevant process in that case. Bayer, however, has called the person who was responsible for managing the preparation, filing and prosecuting the PCT application on which the patent was based.

91 This is not to say that I would construe any document more favourably to Bayer than might otherwise be the case. It is to say only that, despite Dr Broesamle’s silence about his instructions and the meaning of documents, I do not accept that the proper inference, as Generic Health would have it, is that the reason for “Bayer’s failure” to obtain evidence in chief from Dr Broesamle on the topic is that Bayer “fears to do so” because it “would have exposed facts unfavourable” to it. That inference against Bayer is not available in circumstances where Dr Broesamle was called, he was undoubtedly the relevant witness to give evidence having regard to his role, and nothing to that effect was put to him. The inference also becomes improbable in the face of the substantial number of patents for which Dr Broesamle was responsible, his particular responsibility for all fertility and hormone patents, his unchallenged expertise in chemistry and patents law, his unchallenged evidence of P&V’s expertise in pharmaceutical patents, his unchallenged evidence of attending many meetings and having numerous discussions with P&V, and his unchallenged and unsurprising evidence of lack of any memory of the circumstances surrounding the August 1999 letter from P&V and of the meeting of 14 January 1999.

92 Where this leaves me, of course, is with the documents themselves. Consistent with my observations above, the documents are to be approached mindful of the overall context. There is no basis to construe the documents in a manner for or against Bayer in the event of ambiguity. There is also no basis to draw or not draw inferences for or against Bayer from the documents. In the circumstances of this case, the meaning of and inferences to be drawn from the documents are not to be approached with any predisposition of the kind which informed my reasoning in Gilead.

93 Nor, for the same reasons as given above, can any significance be given to the fact that Dr Ulrich (who returned to Bayer and currently works there) was not called to give evidence. Dr Broesamle was the person who made the decisions about the PCT application, not Dr Ulrich. The submission of Generic Health that Dr Broesamle did not suggest that Dr Ulrich was “incapable of handling the matters in his absence” is beside the point. There is no evidence that Dr Broesamle was absent during any particular period. The fact that correspondence was sent between Dr Ulrich and P&V is immaterial given Dr Broesamle’s evidence that he, not Dr Ulrich, was the responsible decision-maker for the entire patent family (in consultation with a person other than Dr Ulrich), and that while he and Dr Ulrich worked as a team, he was Dr Ulrich’s senior.

94 Further, given that Bayer called Dr Broesamle there is no scope for the submission that Bayer has not explained why it did not call Dr Ulrich. Bayer did not have to explain not calling a person who reported directly to Dr Broesamle given that he was called. Thus, there was no “failure” to call Dr Ulrich. There is no reason to infer that Dr Ulrich would be in any better position than Dr Broesamle to give evidence about the PCT application (or priority documents leading up to it). The fact that Dr Ulrich was the recipient of the August 1999 letter is of no significance once it is accepted that Dr Broesamle had the senior role and was the relevant decision-maker and that Dr Ulrich worked with Dr Broesamle as a team.

95 The same reasoning applies to Generic Health’s submission that Bayer failed to call other people involved in the drafting process, including people from P&V. The answer to the submission is that the most relevant person was Dr Broesamle because it was he who was responsible within Bayer for managing the PCT application (and related priority documents) and it was he who had the final decision-making capacity in consultation with Bayer’s Head of Patents and Licensing, and Dr Broesamle was called. The question why Bayer did not call other people to give evidence about the same issue does not arise in these circumstances.

96 Nor do I consider it open to Generic Health to submit that a document which has not been produced (a facsimile from Dr Ulrich to P&V referred to in the August 1999 letter from P&V to Dr Ulrich) founds an inference against Bayer in respect of the missing document having regard to Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 303, 312 and 320-332. This is because Dr Broesamle’s unchallenged evidence was that he had made reasonable enquiries and that there were no other documents than the documents discovered, which included the March and August 1999 letters but not the missing letter from in between these dates. While it is true that Dr Broesamle subsequently located some further documents, he explained that they had been inadvertently overlooked. In the face of this unchallenged evidence it cannot be submitted that the failure to tender the missing document is “unexplained” or that Bayer did not tender it for fear it might harm its case, and thus there can be no inference that the missing document would not have assisted Bayer. It is simply a missing document.

97 Other than this it is apparent from the evidence that Dr Broesamle’s view of the high level of skill and competence of P&V was justified. As Dr McCann said:

The choice of the combination of Ms Birgit Thalso-Madsen and Dr Marianne Johansen, given their combined backgrounds in organic chemistry and pharmaceutical sciences, together with their patent qualifications and experience as European Patent Attorneys, to draft the priority documents appear to me to be one that falls into an ideal overall combination of technical backgrounds, competency and experience for the subject matter in suit, being broadly speaking, a pharmaceutical formulation comprising a combination of two organic chemicals for contraception.

98 The next issue is the documents which are in evidence.

Documentary evidence

99 As explained below there is force in Bayer’s submission that Generic Health’s case “is based on the flawed premise that the universe of information available to those involved in the process of drafting the Patent priority documents is solely that contained in the summary reports summarised in” a table which was prepared within Bayer immediately before instructions were given to obtain patent protection for the Yasmin formulation. As Bayer also said:

Such an approach is artificial and ignores the reality of the drug development process at a pharmaceutical company. It overlooks the background research work against which the invention was made and the accumulated knowledge of the properties and characteristics of DRSP known to the drug discovery team members resulting from an ongoing 10 year research and development project investigating potential uses of DRSP including as an OC or in Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT).

100 The documents fall into three categories, the documents relating to the preparation of the PCT application (and related priority documents), other documents created within Bayer which pre-date the PCT application, and the PCT application itself (including documents referred to in the PCT application).

101 Documents relating to the preparation of the PCT application: Dr Broesamle explained that in late 1998 the then Head of Patents at Schering AG directed him and Dr Ulrich to engage P&V to obtain patent protection for the Yasmin formulation of DRSP and EE. Dr Broesamle believed that P&V had particular expertise in the preparation of pharmaceutical formulation patents and he had confidence in the quality and soundness of P&V’s work, his experience always having been that P&V complete their work with a high level of skill and care and in accordance with his instructions.

102 The PCT application (on which the Australian patent was based) was based on two priority documents, being US and European patent applications which were filed on 31 August 1999. To prepare those priority documents, Dr Broesamle instructed P&V, but others from Schering AG were also involved in the process including Dr Ulrich and three of the named inventors, Mr Hilmann, Dr Heil, and Dr Lipp. The PCT application based on the priority documents was filed on 31 August 2000. In accordance with its instructions P&V then instructed Australian patent attorneys (FB Rice & Co initially and then Davies Collison Cave) to obtain patent protection in Australia. The Australian application was filed on 14 March 2002 and granted on 30 June 2005 and was based on the PCT application, subject to an amendment made in 2004, before the grant of the patent, to ensure consistency with the European Patent application then also being prosecuted based on the PCT application. The amendment is relevant to the dissolution test issue which is dealt with separately below.

103 The first document which I infer is of direct relevance to the preparation of the priority documents and thus the PCT application is dated August 1998. It is a table identifying five reports in respect of different formulations of DRSP and EE including 0.5, 1, 2, and 3mg of DRSP. From the fact that the table identifies the status and availability of each report, I infer that Schering AG was collating information it considered of obvious relevance to the patents for DRSP for which it subsequently applied. I infer that Schering AG was at least aware of all of the information in these five reports when it gave instructions to P&V for the framing of the specifications for the priority documents and PCT application.

104 Another document headed “Open questions for patent application regarding DRSP” contains the following:

1) DRSP: EE (ratio) contraceptive

[Dr Hethecker]

DRSP: EE (ratio) hormonal disorders

[Dr Schurmann]

- therapeutic effect (optimal)

- side effects (minimal)

105 From this I infer that Schering AG was considering the ratio of, relevantly, DRSP to EE to achieve the optimal therapeutic effect and minimal side effects for contraceptive purposes (and separately for hormonal disorders). I infer that they were doing so for the purposes of seeking patent protection for the Yasmin formulation given the timing and the content of the document.

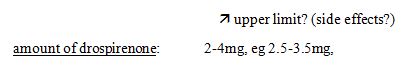

106 There is a typed document dated 13 November 1998 which appears to have been prepared by Mr Hilmann and Dr Heil, two of the three named inventors. It refers to an active ingredient of drospirenone in the range of 0.5 to 7.0mg, with a handwritten note beside this stating “lower limit 2mg for ovulation inh” which must mean 2mg as the lower limit for ovulation inhibition (a figure to be expected once the reports, discussed below, are considered). I infer from this that Schering AG was considering the dosage range and held the view that 2mg was the lower limit for ovulation inhibition.

107 There is also a handwritten document which identifies the structure and characteristics of DRSP and contains other information which resembles the information in the priority documents and PCT application. It identifies the invention as involving:

(a) Amount of drospirenone (and estradiol) for therap. effect (contraceptive without increased blood pressure).

(b) quick release in gastiric environ of sparingly sol.subst…

108 As both of these concepts find their way into the priority documents and PCT application, I infer that these notes were prepared for the purpose of instructing P&V and that the substance of them, if not the notes themselves, was communicated to P&V.

109 After summarising a number of the reports referred to in the table discussed above, the notes record this:

110 There was debate about the significance of the arrow and question marks in this note. The real significance of the document is that it discloses active consideration by Schering AG of the dosage range of DRSP, I infer, for therapeutic effect and of the upper limit consistent with the objective of minimising side effects. The range being considered to achieve those objectives was 2 to 4mg. Insofar as the arrow might be of any relevance, there is good reason to reach the same conclusion as Dr McCann that, in the context of the research about DRSP and the intention to obtain protection for the Yasmin formulation, it is likely that what was being asked was whether side effects could be avoided at a dose of about 4mg. This is consistent with a subsequent suggestion by P&V for a higher (5mg) dose as the upper end of the range which, it may be inferred, Schering AG subsequently rejected. It is also consistent with Dr McCann’s evidence that a patent attorney, properly, would always look for the higher range. As Dr McCann put it:

…But there’s another way that a patent attorney would normally look at it – is, “Can we get higher than four milligrams?” Right? The scientist has said, “Look, the range is two to four milligrams”, and the patent attorney says, “Well, can we get six milligrams?”, or, “Can we get five milligrams?”.

Yes?---Is there basis for going further than that? And so the question marks there that I – the way I would, sort of, look at them is more in that light as a patent attorney, rather than there’s a question mark about four milligrams necessarily. You know, I – as a patent attorney, I would say, you know, “Can we get more, and is there basis for getting more without getting – without – that we can we support?”, if you like.

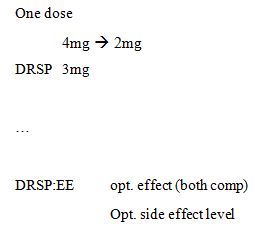

111 One document that Dr Broesamle located after he completed his discovery affidavit is an undated two page handwritten document. Dr Broesamle did not write these notes but recognised that the paper on which they are written was commonly used at Schering AG at the relevant time (14 January 1999). The notes are in two columns, one headed “Anti Contraceptive” and one headed “Hormonal Replacement”. Both sides refer to DRSP and EE. Under the first column there is stated:

112 From this I can comfortably infer at least the following:

(1) The document relates to the preparation of the priority documents for the PCT application.

(2) The document was created by someone within Schering AG or P&V.

(3) Schering AG or P&V was considering the optimum dosage of DRSP and EE for two compositions, the first being contraceptive and the second hormonal.

(4) The dosage range for DRSP being considered in order to achieve the optimum effect and the optimum side effect level was 2 to 4mg or 3mg.

113 Dr Broesamle then located some notes in his own handwriting immediately behind a letter from P&V dated 19 January 1999. Dr Broesamle’s handwritten notes, partly in German, include the following:

DRSP – Meeting

3 mg DRSP

…

OC | HRT |

DRSP 3mg - (4-2) | DRSP 2,3,4mg |

… | … |

114 Given that this is in Dr Broesamle’s handwriting this document confirms that he was considering the dosage range for DRSP for contraceptive and hormonal replacement therapy purposes. Given the similarity between this and the document above I infer that they are notes of the same meeting. I thus infer that Dr Broesamle was considering 2 to 4mg or 3mg as the dosage range for DRSP for contraceptive purposes for optimum effect and side effect (which must mean minimised) level.

115 The next document is a letter from P&V to Dr Ulrich and Dr Broesamle dated 14 January 1999 which thanks them for a “pleasant and interesting meeting in Berlin on 14 January 1998 [sic]”. The letter continues:

We look forward to cooperating with your [sic] regarding the drawing up of a new patent application and expect to receive further material from you by the end of January.