FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 2, penultimate sentence, the word “Tribunal” has been replaced with the word “Commission”. |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent JACKSON POWELL Second Respondent CALUM THWAITES Third Respondent | |

INTRODUCTION:

1 The applicant (“Ms Prior”) seeks an extension of time in which to apply for leave to appeal against a decision of a Judge of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (the “Circuit Court”). The matter has attracted considerable media attention. The present application involves complex procedural questions, as well as difficult factual and legal considerations. In view of the widespread public interest in the matter, I shall deal with some aspects in more detail than I might otherwise have done.

MS PRIOR’S CLAIM

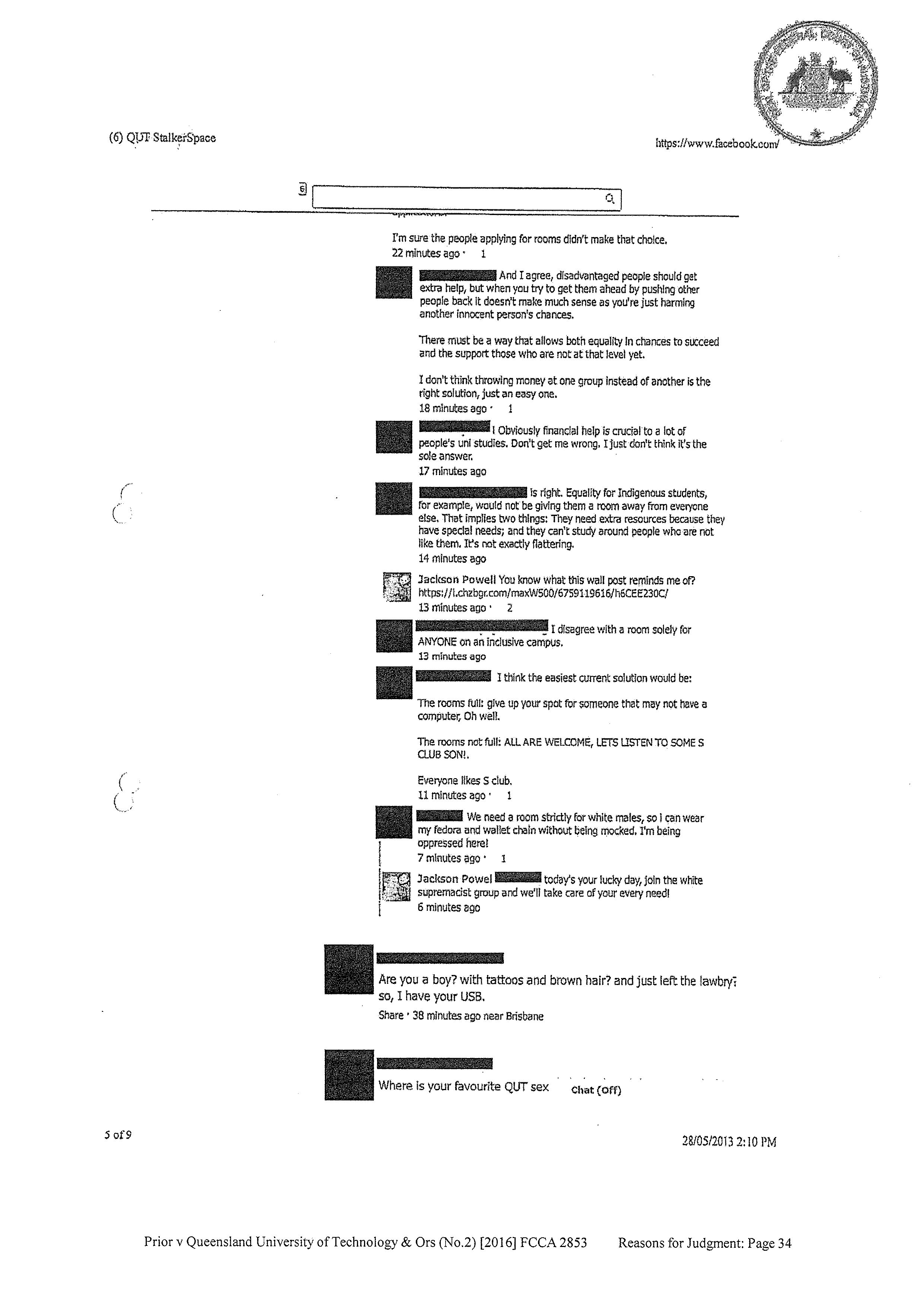

2 Ms Prior claims that the present respondents (“Mr Wood”, “Mr Powell” and “Mr Thwaites”, collectively the “respondents”) each infringed s 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (the “Racial Discrimination Act”). Ms Prior was, at the time of the alleged infringements employed by the Queensland University of Technology (“QUT”). The respondents were, or had been students at that university. QUT is a party to the principal proceedings, but not to the present application. On 27 May 2014 Ms Prior made a complaint to the Australian Human Rights Commission (the “Commission”) pursuant to s 46P of the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth). The conduct giving rise to such complaint had occurred on 28 May 2013. Proceedings in the Commission were terminated on 25 August 2015. The Circuit Court proceedings were commenced on 23 October 2015.

3 Sections 18B, 18C and 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act provide:

18B Reason for doing an act

If:

(a) an act is done for 2 or more reasons; and

(b) one of the reasons is the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of a person (whether or not it is the dominant reason or a substantial reason for doing the act);

then, for the purposes of this Part, the act is taken to be done because of the person’s race, colour or national or ethnic origin.

18C Offensive behaviour because of race, colour or national or ethnic origin

(1) It is unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if:

(a) the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people; and

(b) the act is done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.

...

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), an act is taken not to be done in private if it:

(a) causes words, sounds, images or writing to be communicated to the public; or

(b) is done in a public place; or(c) is done in the sight or hearing of people who are in a public place.

(3) In this section:

public place includes any place to which the public have access as of right or by invitation, whether express or implied and whether or not a charge is made for admission to the place.

18D Exemptions

Section 18C does not render unlawful anything said or done reasonably and in good faith:

(a) in the performance, exhibition or distribution of an artistic work; or

(b) in the course of any statement, publication, discussion or debate made or held for any genuine academic, artistic or scientific purpose or any other genuine purpose in the public interest; or

(c) in making or publishing:

(i) a fair and accurate report of any event or matter of public interest; or

(ii) a fair comment on any event or matter of public interest if the comment is an expression of a genuine belief held by the person making the comment.

4 The respondents deny any breach of s 18C and, in the alternative, seek to invoke the protection of s 18D.

5 As I understand it, Ms Prior’s case is as pleaded in her amended points of claim (the “points of claim”). At paras 5-14 she sets out the relevant incidents as follows:

5. The Applicant was at all material times:

(a) an employee of the second respondent;

(b) identified as an aboriginal person;

(c) engaged in a course of study with the second respondent;

(d) performing the role of Administration Officer in the first respondent's Oodgeroo Unit, Garden's Point campus in accordance with her duties as outlined in the Position Description.

6. The Oodgeroo Unit is a unit within the First Respondent established to:

(a) help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to enter university;

(b) offer academic, personal and cultural support to students;

(c) conduct academic research in Indigenous studies, knowledge and associated areas of interest;

(d) provide an indigenous perspective to the First Respondent through teaching and learning; and

(e) organise events for staff, students and the general public.

7. At the Gardens Point campus, the Oodgeroo Unit has offices, and provides facilities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students including, computer labs, printing and photocopying facilities. The Oodgeroo Unit also provides quiet places for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students to study, work with tutors, and to meet with other students in a culturally safe space.

8. The Applicant works as part of the Professional Services Team within the Oodgeroo Unit, which provides operational and administrative support to students and staff of the Oodgeroo Unit.

9. The Applicant's role in the Oodgeroo Unit is to act as the first point of contact for staff and student visitors to the Oodgeroo Unit's facilities at the Gardens Point campus. The Applicant's role requires that she work alone in the reception area of the Oodgeroo Unit performing this function.

10. The Applicant's role also:

(a) has responsibility for the reception area of the Oodgeroo Unit's facilities at the Gardens Point campus;

(b) has responsibility for the meeting rooms at the Oodgeroo Unit's facilities at the Gardens Point campus;

(c) manages the tutorial room, including the bookings for the tutorial room;

(d) monitors usage of the meeting rooms, tutorial room and computer lab;

(e) maintains the office computers and stationary; and

(f) provides general assistance to students and tutors using the facilities.

11. The computer lab in the Oodgeroo Unit and the Gardens Point campus is provided for use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students only.

12. On 28 May 2013 three men entered the computer lab in the Oodgeroo Unit at the Gardens Point campus.

13. The Applicant advised the three men that they were in the Oodgeroo Unit, which was an indigenous space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait students studying at the First Respondent. The Applicant asked the three men whether they were Indigenous. The three men told the Applicant that they were not Indigenous. The Applicant advised the man that there were other places at the Gardens Point campus where they could access computer facilities and asked the men to leave ("the Computer Lab Incident").

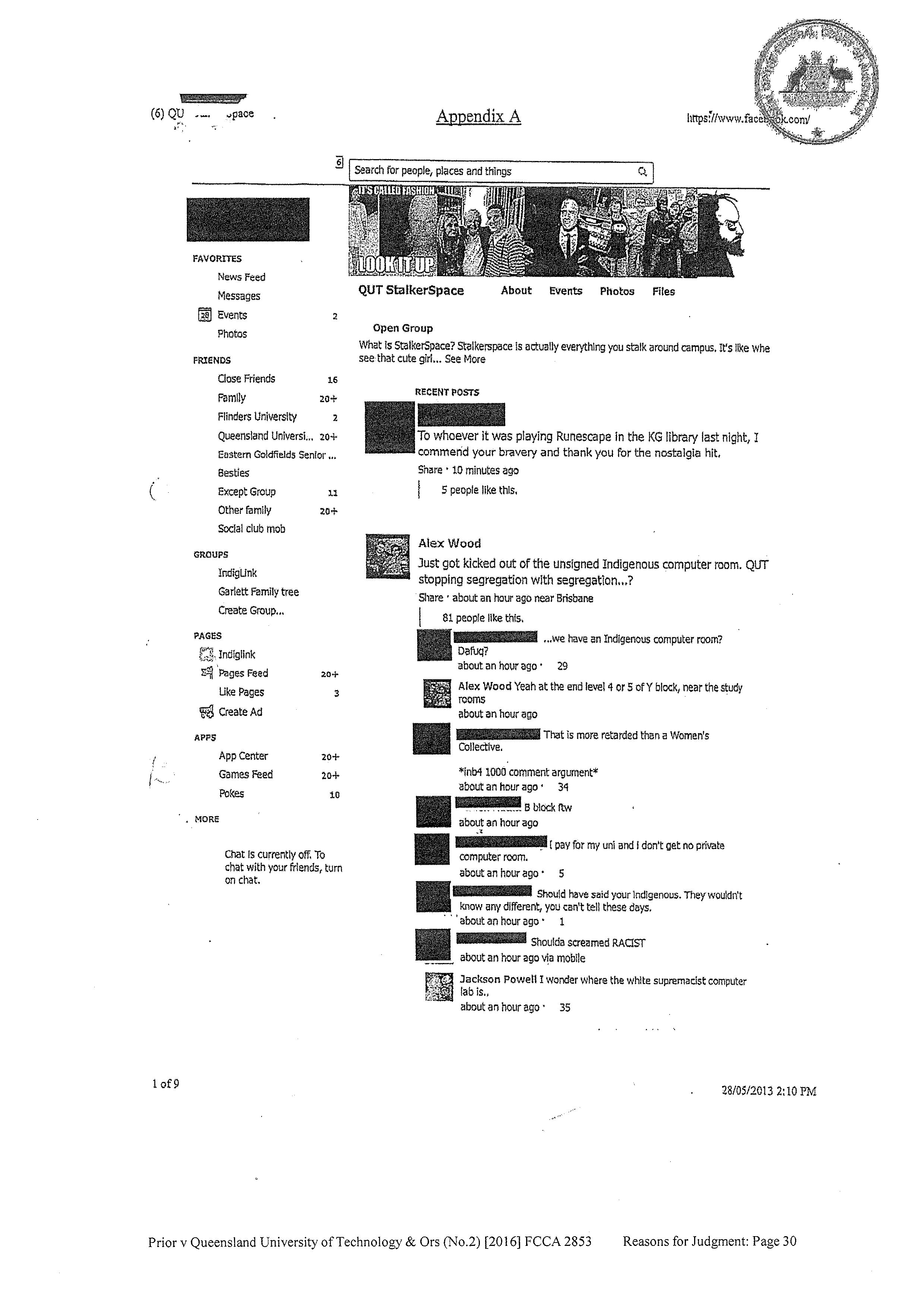

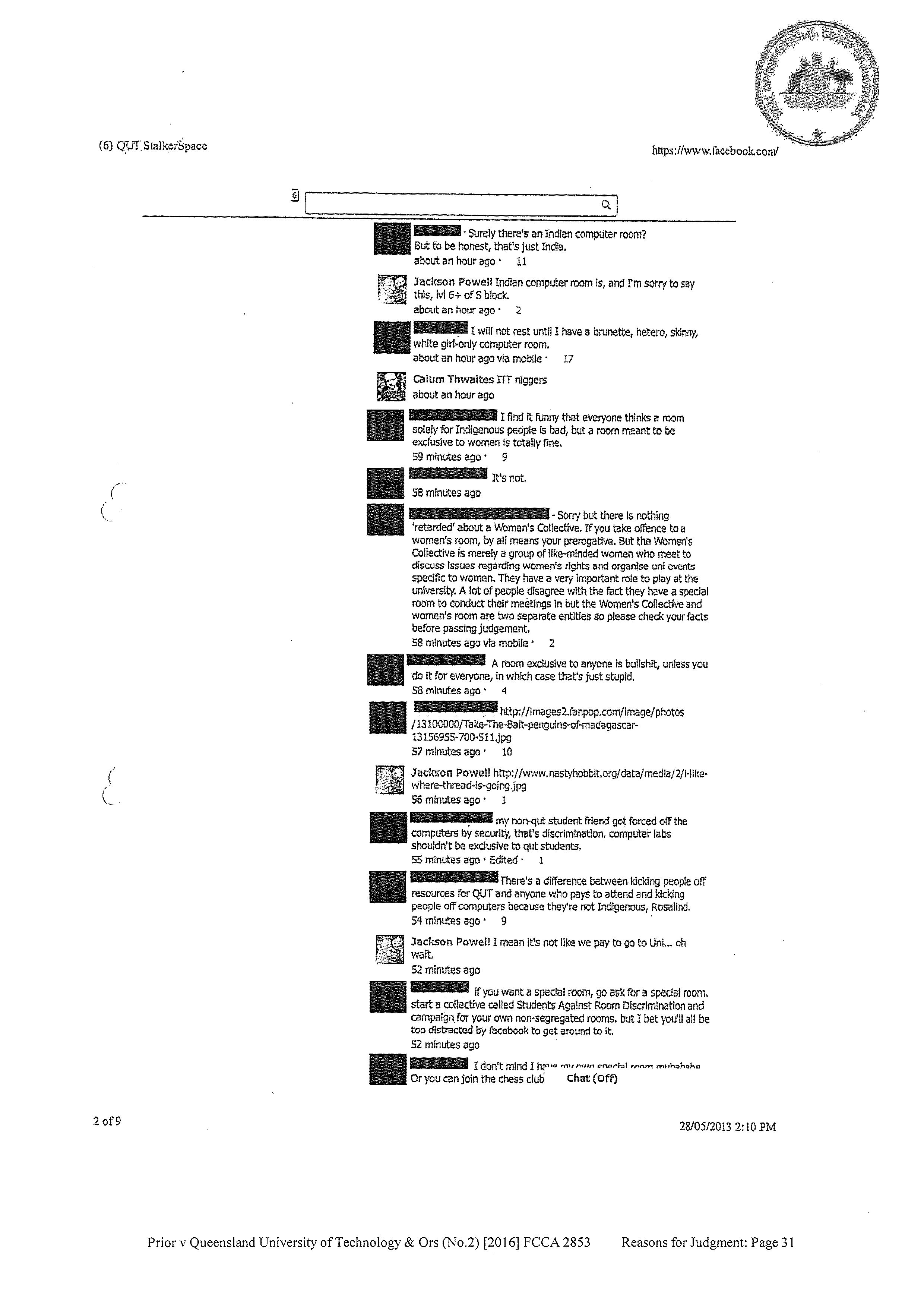

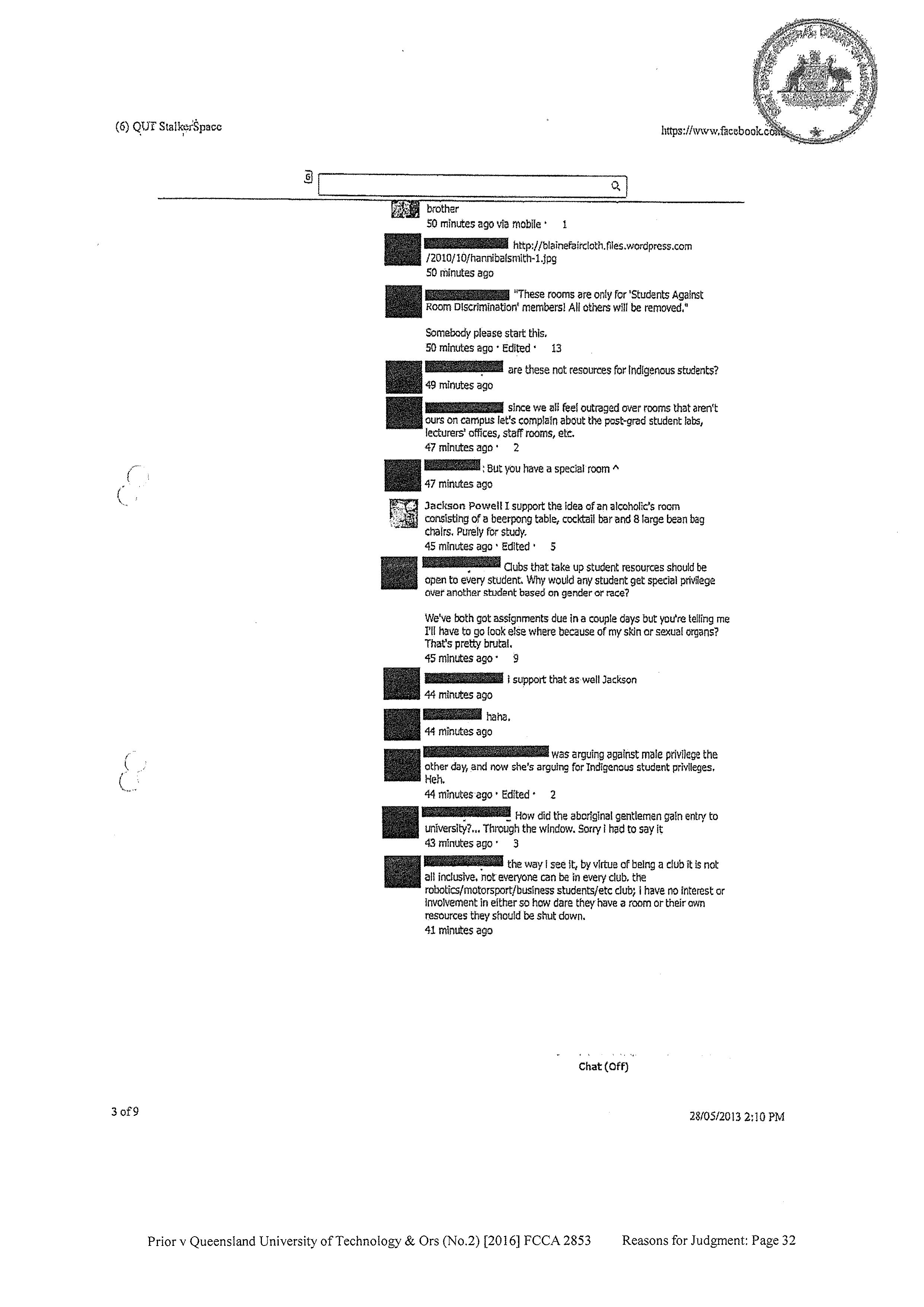

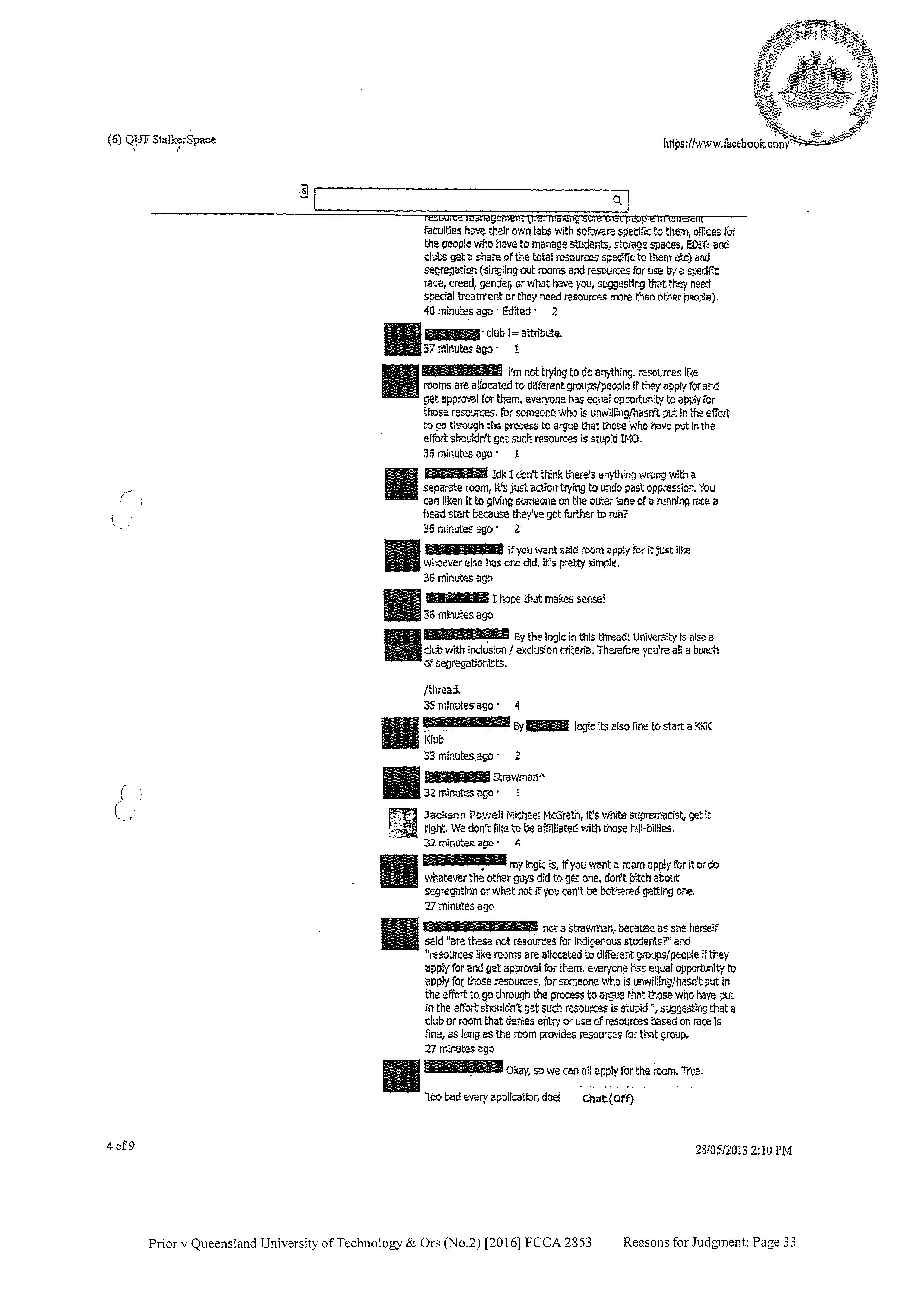

14. One hour after the Computer Lab Incident, information was posted on a Facebook page called "QUT Stalker Space" ("Stalker Space") regarding the Computer Lab Incident:

(a) a post by the fourth respondent, Alex Wood, stated "Just got kicked out of the unsigned Indigenous computer room. QUT stopping segregation with segregation".

(b) The sixth respondent, Jackson Powell, posted the following:

(i) "I wonder where the white supremacist computer lab is"

(ii) (in response to a post) it's white supremacist, get it right. We don't like to be affiliated with those hill-billies"

(iii) (responding to the ninth respondent)"Chris Lee ... today's your lucky day, join the white supremacist group and we'll take care of your every need".

(d) the seventh respondent, Calum Thwaites, posted "ITT niggers".

6 At para 15 Ms Prior pleads that the computer lab incident and the posts made her feel that indigenous students could not have a culturally safe space to study, and that she was very upset. Ms Prior then pleads other events which relate to her claims against other respondents. At paras 21 and 22 she pleads:

21. The Applicant left work at the Oodgeroo Unit on 29 May 2013 and went home sick.

22. By email addressed to the Second Respondent and cc'd to Professor Lee Hong dated 30 May 2013 the Applicant advised:

(a) the Computer Lab Incident Posts, Dr Hayes' Posts and the Further Posts were very stressing for her personally;

(b) she had left the campus the previous day due to stress;

(c) she did not feel safe attending her workplace and believed it was a workplace safety issue;

(d) she felt that she may be subject to verbal or physical attack by the people who posted the Computer Lab Posts and the Further Posts, or people associated with them if she returned to work at the Oodgeroo Unit;

(e) she was seeking assurances in relation to her workplace safety prior to returning to work at the Oodgeroo Unit.

7 At para 46 Ms Prior pleads:

46. The Applicant contends that each of the posts comprising the Computer Lab Incident Posts and [other posts not involving Messrs Wood, Powell and Thwaites]:

(a) were writings communicated to the public and, therefore, done otherwise than in private;

(b) were reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate the Applicant and/or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students of the First Respondent and/or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people;

(c) were done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students of the First Respondent entitled to use the facilities of the Oodgeroo Unit; and

(d) were therefore made in contravention of section 18C(1) of the Act.

8 At paras 52 and 53 Ms Prior pleads:

52. The Applicant has suffered loss and damage as a result of the First to Tenth Respondents’ contraventions of the Act, namely:

(a) offense [sic], embarrassment humiliation and psychiatric injury;

(b) ongoing fear for her safety;

(c) future economic loss as a consequence of the Applicant being forced to take unpaid sick leave unlawful discrimination by the First Respondent as set out in these contentions;

(d) loss of training further education course opportunity.

53. The Applicant seeks the following remedies:

(a) the First to Tenth Respondents provide a public apology to the Applicant;

(b) the First to Tenth Respondents pay the Applicant compensation for 'loss or damage suffered by the Applicant caused by the contraventions of the Act, namely;

(i) $100,000.00 for general damages;

(ii) damages for past economic loss being the Applicant’s lost wages from 29 May 2013 to 6 September 2015;

(iii) future economic loss being the Applicant's reduced salary from 7 September 2015 to a date determined by the Court;

(c) interest at the rate of 9% simple interest per annum on the amount of compensation.

9 His Honour attached to his reasons the “message thread” in which the impugned posts appeared, commencing with that of Mr Wood, deleting only the names of persons not presently involved in this case. I shall also adopt that course. This document was exhibit 1 below. I shall refer to it in that way. Exhibit 1 on appeal is the transcript of proceedings below.

THE LAW

10 The operation of s 18C was considered by Kiefel J in Creek v Cairns Post Pty Ltd (2001) 112 FCR 352, which decision was substantially applied by the Full Court in Toben v Jones (2003) 129 FCR 515. In order to determine whether conduct infringes s 18C, one must ask, pursuant to s 18C(1)(a), whether the action in question is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate an identified person or group of people. One must then ask, pursuant to s 18C(1)(b) whether the act was done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the person or group. In Creek, her Honour said at [12] and [13], concerning s 18C(1)(a):

12 The first enquiry of s 18C is whether the act in question, here the publication of the photograph of the applicant, can in the circumstances be regarded as reasonably likely to offend or humiliate a person in the applicant’s position. The test is, as Drummond J observed in Hagan v Trustees of the Toowoomba Sports Ground Trust [2000] FCA 1615 ... , necessarily objective. For this enquiry what brought about the action constituting the “behaviour” in question and what the applicant felt are not relevant.

13 It is necessary first to consider the perspective under consideration, which is to say the hypothetical person in the applicant’s position or the group of which the applicant is one. A reference to the person’s race may be too wide a description in some cases. That would be so here, where Aboriginal peoples’ views, about being portrayed as having a more traditional lifestyle, will differ depending upon where and in what circumstances they live. In that respect I consider the perspective suggested by the applicant’s counsel in submissions to be apposite, namely that of an Aboriginal mother, or one who cares for children, and who resides in the township of Coen. Such a person would, in my view, feel offended, insulted or humiliated if they were portrayed as living in rough bush conditions in the context of a report which is about a child’s welfare. In that context it is implied that that person would be taking the child into less desirable conditions. The offence comes not just from the fact that it is wrong, but from the comparison which is invited by the photographs. That is, I consider, how a reasonable reader would have viewed the photographs. So far as concerns the respondent’s submission that a reader would simply look at the people involved in the drama, it is not just the faces of the parties which are shown in the photographs. A background is also provided to them and in each case it conveys what might be taken as the parties’ lifestyle. A comparison is in my view invited.

11 At [14]-[16] her Honour said:

14 The respondent submitted that only very serious and offensive behaviour was intended as the subject of s 18C. This can be seen from the heading to the Part, which requires the behaviour to be based on racial hatred, the Second Reading Speech and the Explanatory Memorandum to the Racial Hatred Bill 1994. The Memorandum said that the Bill addressed concerns highlighted by the findings of the “Inquiry into Racist Violence and the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody” and in doing so, the Bill intended to close a gap in the legal protection available to the victims of extreme racist behaviour.

15 It needs to be borne in mind, when reviewing speeches or writings about the Bill, that in addition to providing for the civil prohibition which became s 18C, it was then intended to create three criminal offences relating to inciting racial hatred or threatening racial violence. Those proposed offences did not however survive the federal legislative process and do not appear as sections in the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) as was intended. The Memorandum went on:

“The Bill is intended to strengthen and support the significant degree of social cohesion demonstrated by the Australian community at large. The Bill is based on the principle that no person in Australia need live in fear because of his or her race, colour, or national or ethnic origin.”…

“The Bill maintains a balance between the right to free speech and the protection of individuals and groups from harassment and fear because of their race, colour or national or ethnic origin. The Bill is intended to prevent people from seriously undermining tolerance within society by inciting racial hatred or threatening violence against individuals or groups because of their race, colour or national or ethnic origin.”

The s 18C provision was described as “… the proposed prohibition on offensive behaviour based on racial hatred …”.

16 Pursuant to the section the nature or quality of the act in question is tested by the effect which it is reasonably likely to have on another person of the racial or other group referred to in par (b) of the subsection. To “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” are profound and serious effects, not to be likened to mere slights. Having said that, the court would of course be conscious of the need to consider the reaction from that person or group’s perspective. If par (a) of the subsection is established, as it is here, it is necessary then to consider the additional requirement relating to the reason for the act.

12 Concerning s 18C(1)(b) her Honour said at [17]-[28]:

17 The title says that the prohibition is against behaviour which is based on racial hatred, but the heading to the section simply refers to the reason for it being “race, colour or national or ethnic origin.” This is reiterated in s 18B, which deals with acts being done for more than one reason. So long as one of those reasons is one of the four listed in the subsection, the act in question is taken to be for that reason.

18 Headings are to be taken as part of the statute (s 13(1) Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth)). Drummond J in Hagan considered that the heading to Part IIA should be taken into account as part of the statutory context, referring to CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd (1997) 187 CLR 384, 408, where it was said that the modern approach to statutory interpretation was to consider context at the outset and this included the mischief which, it could be discerned, the statute intended to remedy. Whilst one may accept that hatred of other races is an evil spoken of in the statute, I do not consider that the heading creates a separate test - one which requires the behaviour to be shown as having its basis in actual hatred of race. Sections 18B and 18C make it plain that the prohibition will be breached if the basis for the act was the race, colour, national or ethnic origin of the other person or group. Whilst the reason for the behaviour in question may be a matter for enquiry, and this is a topic I will shortly turn to, the intensity of feeling of the person whose act it is, is not necessary to be considered, although in some cases it might shed light on what is otherwise inexplicable behaviour.

19 There have been differences of view expressed about the meaning of phrases such as “on the ground of” and “by reason of” in the context of discrimination legislation, and as to whether they require a causal connexion between the act complained of and the characteristic or attribute of the person identified in the legislation, which is to say the reason for the conduct. In some judgments it has been held that it does not matter if intention or motive are absent. This was the view expressed by Deane and Gaudron J in Australian Iron & Steel Pty Ltd v Banovic (1989) 168 CLR 165, 176. Their Honours were dealing with provisions of the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) (s 24(1) and s 24(3)) which are similar to s 9 and s 9(1A) RDA. Section 24(1) provided that a person discriminated against another if, “on the ground of his sex”, or “a characteristic that appertains generally to” or “is generally imputed to persons of his sex, he treats him less favourably than in the same circumstance, or circumstances which are not materially different, he treats or would treat a person of the opposite sex”. Section 24(3) provided for indirect discrimination. And in Waters v Public Transport Corporation (1991) 173 CLR 349, 359, Mason CJ and Gaudron J considered that s 17(1) of the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (Vict), which refers to discrimination “on the ground of the status or by reason of the private life of the other person”, required only that the material difference in treatment be based on the status or private life of that person, notwithstanding an absence of an intention or motive on the part of the alleged discriminator that is related to the status or private life of the person less favourably treated. Such views are in line with R v Birmingham City Council, ex parte Equal Opportunities Commission [1989] AC 1155 (HL) referred to in Waters (and see also James v Eastleigh Borough Council [1990] 2 AC 751 (HL)).

20 Their Honours’ reasoning was also that the first of the discrimination provisions, similar in effect to s 9 RDA set out above, extend to acts of indirect discrimination. In cases of indirect discrimination motive or intention play no part. The judgments of Dawson and Brennan JJ in Banovic (184, 171) and Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ in Waters (392-3, 401-2) however hold that provisions like ss 9 and 9(1A) RDA are mutually exclusive of each other. Such a conclusion is not directly relevant to any issue here concerning s 18C RDA, but it may well explain the construction placed on phrases such as “on the ground of” and “by reason of” by Mason CJ, Deane & Gaudron JJ. McHugh J in Waters (400-1) considered that the examples given by Deane and Gaudron JJ in Banovic, where intention or motive could not be said to be a necessary condition of liability, were cases falling within the concept of indirect discrimination dealt with under the separate subsection. His Honour expressed the following, contrary view of the meaning to be given to the words of the requirement:

“The words “on the ground of the status or by reason of the private life of the other person” in s. 17(1) require that the act of the alleged discriminator be actuated by the status or private life of the person alleged to be discriminated against.

…

The words “on the ground of” and “by reason of” require a causal connexion between the act of the discriminator which treats a person less favourably and the status or private life of the person the subject of that act (“the victim”). The status or private life of the victim must be at least one of the factors which moved the discriminator to act as he or she did.”

21 His Honour went on to say that, whilst those determining whether discrimination has occurred are not bound by “the verbal formula” which the alleged discriminator has used, if they would in any event, have acted in the way they did or if they acted genuinely on a non-discriminatory ground, they cannot be said to have acted “on the ground of the status or by reason of the private life” of the victim.

22 In my view this accords with the reasoning of Dawson J in Banovic, which described the enquiry as one as to the “true basis” or “true ground” of the action in question. His Honour also held that the subsection was not to be supplied [sic] subjectively, which I take to mean not by reference only to what the person whose conduct in question provides as a ground or basis for the action. The enquiry considers what was in truth likely to have given rise to it, when regard is had to all the circumstances, and this would include the nature of the conduct and the words and expressions used.

23 Such an approach would also seem to me to address the concerns expressed by Deane and Gaudron JJ (Banovic, 176) that discrimination legislation operates with respect to unconscious acts and that it is not necessary that there be a conscious appreciation, on the part of the discriminator, of their actions. Accepting this, it is not apparent that a search for the true reason would limit the application of the legislation. A statement by their Honours appears to accept that this is the proper enquiry (at 176-177):

“And there may be other situations in which habits of thought and preconceptions may so affect an individual’s perception of persons with particular characteristics that genuinely assigned reasons for an act or decision may, in fact, mask the true basis for that act or decision. Thus, in the ascertainment of the true basis of an act or decision it may well be significant that there is some factor, other than the ground assigned, which is common to all who are adversely affected by that act or decision. In certain situations that common factor may well be seen to be the true basis of the act or decision. And that may also be the case where some factor is identified as common to a significant proportion of those adversely affected.”

24 In my respectful view the approach taken by McHugh J gives meaning to words such as “on the ground of” and “because of”. The need to have regard to the plain words of the sections was discussed in some detail by Lockhart J in Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission v Mt Isa Mines Ltd (1993) 46 FCR 301, 322. Beyond that the matter is one of factual enquiry.

25 In Australian Medical Council v Wilson & Ors (1996) 68 FCR 46, 58 (Full Court) Heerey J referred to the judgment of Doyle CJ in Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement v State of South Australia (1995) 64 SASR 551, 553 where his Honour held that the enquiry under s 9 RDA:

“… is into whether the racial distinction is a material factor in the making of the relevant decision or the performing of the relevant act.”

26 I do not understand this view to be contrary to that of McHugh J. Whilst Doyle CJ had said that it did not mean that the inquiry is one as to motive, his Honour later refers to the question whether race is exposed “as the true basis of the decision”.

27 I should add that Lockhart J in Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission v Mt Isa Mines (321-2) equated the words “by reason of” with “because of”, “due to”, “based on”, “or words of similar import which bring something about or cause it to occur”; although it seems to me that “because of” perhaps marks out the causal requirement more clearly. I am aware that Weinberg J in Macedonian Teachers’ Association of Victoria Inc v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (1998) 91 FCR 8, 30 has expressed the view that “based on” in s 9(1) RDA encompasses a broader, and perhaps a non-causative relationship, but it is not necessary for me to deal with that question further here (and see also Australian Medical Council v Wilson).

28 In the present case the question is whether anything suggests race as a factor in the respondent’s decision to publish the photograph. ...

(Footnotes omitted.)

13 Clearly, the process to be undertaken in considering both s 18C(1)(a) and s 18C(1)(b) is evaluative. In that sense, minds may differ concerning the likely effect of relevant conduct, and as to whether such conduct was done because of the race, colour, or national or ethnic origin of a particular person or group of people.

HISTORY OF THE PROCEEDINGS

14 As I have said, the proceedings below were commenced on 23 October 2015. Ms Prior delivered points of claim on 14 January 2016. By applications dated 10, 15 and 18 February 2016, Messrs Thwaites, Wood and Powell respectively applied to have the proceedings against each of them dismissed or stayed. Concerning the state of the matter at the time of the hearing of those applications, the primary Judge said:

9. Mr Wood, Mr [Powell] and Mr Thwaites have each filed defences to Ms Prior’s application. They each take many points in answer to Ms Prior’s claims. For the purposes of these summary dismissal applications, however, they do not rely on each of the matters they have raised by way of defence.

10 On 2 March, 2016 Ms Prior filed an affidavit sworn by her. That affidavit comprises the evidence-in-chief upon which she intends to rely at the trial of these proceedings and was filed in accordance with the Court’s directions. The applicant did not rely upon that affidavit at the hearing of the summary dismissal applications. Rather, she relied upon an affidavit by her solicitor filed on 4 March, 2016 and an affidavit by the third respondent filed on 7 March, 2016.

11. Mr Wood has filed his affidavit of evidence-in-chief. He does not deny posting the messages to the “QUT Stalker Space” Facebook page that Ms Prior alleges that he posted.

12. Mr Powell has filed his affidavit of evidence-in-chief. He does not deny posting the messages to the “QUT Stalker Space” Facebook page that Ms Prior alleges that he posted. He takes issue with the timing of those posts attributed by Ms Prior, but nothing seemingly turns upon that.

13. Mr Thwaites has filed his affidavit of evidence-in-chief. He denies posting the messages to the “QUT Stalker Space” Facebook page that Ms Prior attributes to him. His case is, amongst other matters, that another person has posted the relevant message pretending to be him.

15 At paras [14]-[17] his Honour summarized the basis upon which Messrs Wood, Powell and Thwaites sought to have Ms Prior’s claim dismissed or stayed as follows:

14. Mr Wood seeks to have Ms Prior’s proceeding against him stayed or dismissed on the basis that Ms Prior’s claim for relief against him has no reasonable prospect of success or alternatively, on the basis that:

a. the proceeding or claim for relief is frivolous or vexatious; or

b. the proceeding or claim for relief is an abuse of the process of the Court.

15. He seeks relief pursuant to rule 13.10 of the Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001. In the further alternative, he argues that Ms Prior’s amended points of claim filed on 14 January 2016 be struck out, with leave for her to replead her case. In his written submissions, Mr Wood poses eight questions that arise in the context of his application, but in my view they can be conveniently summarised into four propositions for which he contends, namely

a. Ms Prior does not have any reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding because Mr Wood’s Facebook statement:

i. is not reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate her or the groups she nominates in her amended points of claim; and

ii. was not published because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of Ms Prior or of some or all of the people in the groups nominated by her.

b. Ms Prior does not have any reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding on the basis that Mr Wood’s Facebook statement was made in circumstances which engage s.18D of the of the Racial Discrimination Act.

c. Ms Prior’s proceeding against him is frivolous or vexatious; and

d. Ms Prior’s proceeding against him is an abuse of process.

16. Mr Powell contends that Ms Prior’s proceedings against him should be summarily dismissed for three reasons, namely:

a. there is no arguable case that the words published by Mr Powell were reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate the members of either of the “groups” identified by Ms Prior in subparagraph 46(b) of her amended points of claim;

b. there is no arguable case that Mr Powell posted those words “because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin” of the “group” identified in subparagraph 46(c) of the amended points of claim; and

c. there is no arguable case to negate the exemption under section 18D of the Act.

17. Mr Thwaites contends that he has simply no case to answer. It is alleged that he posted the words “ITT Niggers” to the QUT Stalker Space Facebook page. He denies that he posted those words, or indeed, any words at all. In circumstances where Ms Prior has filed all the evidence-in-chief upon which she intends to rely at the trial of these proceedings and Mr Thwaites contends that she produces no evidence at all that establishes that he published the relevant post, he says her claim against him should be dismissed without the necessity for a trial.

SUMMARY JUDGMENT

16 Pursuant to s 17A of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia Act 1999 (Cth) (the “Circuit Court Act”), the Circuit Court may give judgment in favour of a respondent if the Court is satisfied that the applicant has no reasonable prospect of success in the proceedings. Such a judgment is called a “summary judgment” to distinguish it from a judgment given after a full hearing. Rule 13.10 of the Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001 provides that the Circuit Court may stay or dismiss proceedings if it is satisfied that the applicant has no reasonable prospect of success, the claim is frivolous or vexatious, or the claim is an abuse of process. Obviously, the operation of this rule goes beyond the circumstances contemplated by s 17A. In these proceedings, the primary Judge ordered that the proceedings be dismissed as against each respondent pursuant to r 13.10(a), that is, upon the basis contemplated by s 17A(2) of the Circuit Court Act.

17 As I have said, summary judgment involves the disposal of proceedings without a full trial. Such proceedings, in one form or another, have been available for many years and in most courts. In the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the “Federal Court Act”), there are similar provisions to those contained in s 17A of the Circuit Court Act. They are contained in s 31A, which provision was considered by the High Court in Spencer v The Commonwealth (2010) 241 CLR 118 at [51]-[56]. The majority (Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ) discussed tests which have been adopted in connection with other summary judgment regimes. Their Honours made it clear that judgment may be granted pursuant to s 31A even if it could not be said that the case was so clearly untenable that it could not possibly succeed. Their Honours said at [58]-[60]:

58 How then should the expression "no reasonable prospect" be understood? No paraphrase of the expression can be adopted as a sufficient explanation of its operation, let alone definition of its content. Nor can the expression usefully be understood by the creation of some antinomy intended to capture most or all of the cases in which it cannot be said that there is "no reasonable prospect". The judicial creation of a lexicon of words or phrases intended to capture the operation of a particular statutory phrase like "no reasonable prospect" is to be avoided. Consideration of the difficulties that bedevilled the proviso to common form criminal appeal statutes, as a result of judicial glossing of the relevant statutory expression, provides the clearest example of the dangers that attend any such attempt.

59 In many cases where a plaintiff has no reasonable prospect of prosecuting a proceeding, the proceeding could be described (with or without the addition of intensifying epithets like "clearly", "manifestly" or "obviously") as "frivolous", "untenable", "groundless" or "faulty". But none of those expressions (alone or in combination) should be understood as providing a sufficient chart of the metes and bounds of the power given by s 31A. Nor can the content of the word "reasonable", in the phrase "no reasonable prospect", be sufficiently, let alone completely, illuminated by drawing some contrast with what would be a "frivolous", "untenable", "groundless" or "faulty" claim.

60 Rather, full weight must be given to the expression as a whole. The Federal Court may exercise power under s 31A if, and only if, satisfied that there is "no reasonable prospect" of success. Of course, it may readily be accepted that the power to dismiss an action summarily is not to be exercised lightly. But the elucidation of what amounts to "no reasonable prospect" can best proceed in the same way as content has been given, through a succession of decided cases, to other generally expressed statutory phrases, such as the phrase "just and equitable" when it is used to identify a ground for winding up a company. At this point in the development of the understanding of the expression and its application, it is sufficient, but important, to emphasise that the evident legislative purpose revealed by the text of the provision will be defeated if its application is read as confined to cases of a kind which fell within earlier, different, procedural regimes.

(Footnotes omitted.)

18 In Jefferson Ford Pty Ltd v Ford Motor Company of Australia Ltd (2008) 167 FCR 372, Gordon J identified six principles said to guide the exercise of the power to grant summary judgment pursuant to the Federal Court Act. First, at [124] her Honour noted that, s 31A prescribes a less stringent test for the grant of summary judgment than those applicable under earlier regimes. Her Honour was there making the point which is addressed in the passage from the judgment in Spencer to which I have referred above. Gordon J observed that Parliament’s purpose, in enacting the section, was to strengthen the Court’s power to dispose of unmeritorious matters, and to strengthen the Court’s power to manage proceedings, thus assisting in reducing cost and delay.

19 Secondly, her Honour said at [126], concerning an application for summary judgment (by a plaintiff or applicant), that the assessment of reasonable prospects involved the following steps:

1. identification of the cause of action pleaded;

2. identification of the pleaded facts said to give rise to that cause of action;

3. a review of the evidence (if any) tendered in support of the claim for judgment;

4. identification of the defence pleaded;

5. identification of any facts pleaded which are said to give rise to the defence; and

6. a review of the evidence (if any) tendered in defence of the claim.

20 These steps may readily be adapted so as to apply to a case in which a defendant or respondent seeks summary judgment against a plaintiff or applicant.

21 Thirdly, Gordon J noted that the moving party bears the onus of persuading the Court that the opponent has no reasonable prospect of success. However, once the moving party has established a prima facie case to that effect, the opposing party must respond by pointing to specific factual or evidentiary disputes which make a trial necessary. General denials will not be a sufficient basis for resisting summary judgment.

22 Fourthly, the decision to grant summary judgment is made as a question of law and reviewed as such by an appellate court. The word “may” is used in an “empowering” sense rather than as denoting the exercise of a discretion. Below, I say more about this matter.

23 Fifthly, where there is a real issue of fact relevant to a pleaded cause of action, it is unlikely that the proceedings will have no prospect of success.

24 Sixthly, in discerning whether a real issue of fact exists, the Court must draw all reasonable inferences in favour of the non-moving party.

the approach on appeal

25 In her Honour’s fourth point, Gordon J addressed the approach to an appeal against a decision granting summary judgment. As I understand it, when her Honour referred to the grant of such judgment as being a matter of law, she meant that it involved a decision, to which the decision-maker was led by a consideration of the facts and the law. Minds may differ as to the assessment of the evidence. However such a decision will reflect the relevant court’s view of the evidence and the application of the law to that evidence. That situation differs from cases in which a judge exercises a true discretion. That process involves a choice between available outcomes, based upon the judge’s assessment of the factors which, pursuant to the law creating the discretion, are relevant to its exercise. Gordon J meant that the grant or refusal of summary judgment fell into the former, and not the latter category.

26 In either case, the approach to any appeal will be that prescribed by the High Court in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 per Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ at 504-505 as follows:

The manner in which an appeal against an exercise of discretion should be determined is governed by established principles. It is not enough that the judges composing the appellate court consider that, if they had been in the position of the primary judge, they would have taken a different course. It must appear that some error has been made in exercising the discretion. If the judge acts upon a wrong principle, if he allows extraneous or irrelevant matters to guide or affect him, if he mistakes the facts, if he does not take into account some material consideration, then his determination should be reviewed and the appellate court may exercise its own discretion in substitution for his if it has the materials for doing so. It may not appear how the primary judge has reached the result embodied in his order, but, if upon the facts it is unreasonable or plainly unjust, the appellate court may infer that in some way there has been a failure properly to exercise the discretion which the law reposes in the court of first instance. In such a case, although the nature of the error may not be discoverable, the exercise of the discretion is reviewed on the ground that a substantial wrong has in fact occurred.

THE PRIMARY JUDGE’S REASONS

27 His Honour directed himself as to the way in which he should deal with the applications and, at [28], observed:

There was some incongruity in the way in which the fourth, sixth and seventh respondents on the one hand and the applicant on the other hand, approached the present applications. The respondents’ approach was to invite the Court to consider all of the evidence relied upon by the parties in the present applications and to conclude that the applicant had no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting her claim. The applicant, on the other hand, seems to have approached the applications as applications to strike out her amended points of claim or have the proceedings dismissed on the basis that her pleading did not disclose a reasonable cause of action.

28 His Honour was, in effect, suggesting that Ms Prior’s approach was inconsistent with that taken in Spencer.

29 The primary Judge then set out the relevant parts of ss 18C and 18D and identified a number of propositions by reference to the cases. I should say that for the purposes of this application, the respondents do not rely upon s 18D. There may well be an argument that ss 18C and 18D must be read together, not separately. See Sutherland Shire Council v Folkes (2015) 331 ALR 494 at [49]-[53]. At [32] his Honour observed:

The two common arguments raised by both Mr Wood and Mr Powell are that:

a. the words attributed to each of them in their Facebook posts are not reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate Ms Prior or the groups of people identified by her in her amended points of claim; and

b. in any event there is no causal connection between the words published by each of them and of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of either Ms Prior or the groups of people nominated by her in her amended points of claim.

30 His Honour observed at [37]-[41]:

37. ... The task of the Court in a case of group offence is to identify a hypothetical representative of the group or groups to whom it was suggested the impugned conduct was directed: Eatock v Bolt at [250] and the authorities there cited. The Court must carry out the necessary assessment by reference to that hypothetical representative. Where it is alleged that the impugned conduct is directed at both an identified person and a group of people and the claim made is that both the identified person and the group of people were reasonably likely to have been offended, the conduct should be analysed from the point of view of a hypothetical representative of the group of people and in relation to each of the identified persons where a personal offence claim has been made.

38. As cases like Creek v Cairns Post, Eatock v Bolt and Clarke v Nationwide News (above) demonstrate, where a group offence claim is made, it is the task of the Court to formulate the characteristics of the hypothetical representative of the group or groups concerned. No party addressed me on that matter. No party suggested what characteristics might attend a hypothetical representative of the groups identified by Ms Prior in her amended points of claim. Contrary to the position taken by the submissions for Mr Powell and Mr Wood, for her to succeed in her claim, it would be sufficient for Ms Prior to prove that the impugned words were reasonably likely in all of the circumstances to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a hypothetical representative of one or other of the groups she has identified.

39. Moreover, the necessary assessment is not to be carried out by reference to “an objective application of community standards”. That approach was expressly rejected by Bromberg J in Eatock v Bolt at [253]:

It is the values, standards and other circumstances of the person or group of people to whom s 18C(1)(a) refers that will bear upon the likely reaction of those persons to the act in question. It is the reaction from their perspective which is to be assessed ... . Further, to import general community standards into the test of the reasonable likelihood of offence runs a risk of reinforcing the prevailing level of prejudice. To do that would be antithetical to the promotional purposes of Part IIA. Such an approach has been rejected in relation to sexual harassment ... . Sexual harassment legislation is the arena from which the words “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” were deliberately borrowed ... .

40. The real issue for determination is whether Ms Prior has reasonable prospects of prosecuting her claim that the impugned words were reasonably likely to have the proscribed effect contended for by her. The submissions made by senior counsel for Mr Powell emphasise the point that Ms Prior has not filed any evidence to the effect that anyone was actually offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by Mr Powell’s words. In that circumstance, Mr Powell argues that the absence of evidence that anyone was actually offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated is “a compelling reason to assume that this was not a “reasonably likely” outcome”.

41. But when considering whether the impugned conduct might be regarded as reasonably likely to contravene the prescription of s. 18C(1)(a), what the applicant felt, in response to the conduct, is not relevant: Creek v Cairns Post at [12]. Indeed, evidence that someone was offended, insulted, humiliated, or intimidated by the relevant conduct is entirely unnecessary: Eatock v Bolt (above) at [241] and authorities there cited. In my view, the absence of evidence to that effect cannot be, either as a matter of law, “a compelling reason to assume that [the proscribed effect] was not a “reasonably likely” outcome”.

31 The primary Judge then considered the separate cases against Messrs Wood and Powell.

Mr Wood

32 Mr Wood’s post was the first in the thread set out in exhibit 1 below. It reads as follows:

Just got kicked out of the unsigned Indigenous computer room. QUT stopping segregation with segregation ... ?".

33 The primary Judge considered that the first sentence was factually accurate and unlikely to infringe s 18C(1)(a), whilst the second sentence was a statement of opinion “arguably posed as a question”. Whilst the primary Judge considered that the word “segregation” had negative connotations, he considered that such negativity was directed towards QUT. At para 45 his Honour said:

Taken together the two sentences carry a negative connotation with a racial undertone that derives from the propositions carried within the sentences that QUT has a computer room from which people who are not indigenous are excluded by reason of their race or ethnicity.

34 The primary Judge then dismissed a number of submissions made by Mr Wood and Mr Powell. His Honour noted that Ms Prior advanced both “a personal offence claim” and a “group offence claim”. I understand his Honour to have been using the term “offence” to include “insult”, “humiliation” and “intimidation”.

35 Ms Prior, by her points of claim, had claimed to be “a person” who was likely to have been offended by the various posts as contemplated by s 18C(1)(a). She identified two groups which were likely to have been so offended, namely:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students of QUT (the “student group”); and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (the “wider group”).

36 Kiefel J had observed in Creek at [13], that a group description by reference to race alone may be too wide. In that case, the Court was concerned with Aboriginal people. Her Honour considered that Aboriginal views might differ, depending upon where a particular person lived, and the circumstances in which he or she lived. In the present case, at [46] his Honour seems to have concluded that a group comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students of QUT was too broad to be adopted for the purposes of s 18C(1). I infer that his Honour considered that the identification of the wider group suffered from the same vice. His Honour observed that no party had suggested, “any perspective from which the impugned words might properly be considered”. I understand his Honour to have meant that no attempt had been made to describe the standpoint of a person in the position of Ms Prior or a representative of either identified group.

37 At [47]-[49] his Honour said:

47. The facts and circumstances of each case in which it is alleged that s18C(1)(a) has been transgressed must guide the correct identification of the reasonable victim in each case Clarke v Nationwide News at [64]. But in every case, the hypothetical person or member of the relevant group from whose perspective the relevant conduct is to be considered will be a person who:

a. exhibits characteristics consistent with what might be expected of a member of a free and tolerant society Eatock v Bolt at [255]; Clarke v Nationwide News at [59];

b. meets the description of an ordinary or reasonable member or members of the identified group. “That is so because a group of people may include the “sensitive as well as the insensitive, the passionate and the dispassionate, the emotional and the impassive”. For that reason it is necessary to consider only the perspective of the ordinary or reasonable member or members of the group, not those at the margins of the group whose view may be considered unrepresentative.” Eatock v Bolt at [251] and Clarke v Nationwide News at [62].

48. All the parties before me emphasise that the relevant assessment needs to be undertaken in light of all of the circumstances, including the social, cultural, historical and other circumstances attending the person or the people in the relevant group. However, beyond the factual matters that I have described at the commencement of these reasons and having regard to the course of the Facebook posts, set out in exhibit 1 in these proceedings, no party, particularly Ms Prior suggested that there were, or was likely to be, any other relevant circumstances that would inform the relevant assessment.

49 In my view, it is not reasonably likely that a hypothetical person in the position of the applicant, or a hypothetical member of the groups identified by Ms Prior who is a reasonable and ordinary member of either of the groups who exhibits characteristics consistent with what might be expected of a member of a free and tolerant society and who is not at the margins of those groups would feel offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by Mr Woods words. This is so because:

a. Mr Wood’s words were directed to QUT and its actions; and

b. Mr Wood’s words were rallying against racial discrimination.

38 As I understand this conclusion, it is based upon the assumptions made by his Honour at [47] (set out above), and the absence of any evidence as to the likely effect of the words on either a notional person in Ms Prior’s position (apart from her evidence as to her own reaction) or on a notional representative of either group.

39 At a later stage I shall say something about the proposition that any relevant group for the purposes of s 18C(1), should exhibit, “characteristics consistent with what might be expected of a member of a free and tolerant society”.

40 The primary Judge then considered the operation of s 18C(1)(b), concluding that the reasons for the post were those identified by Mr Wood in his evidence. His Honour sets out such evidence at [51] as follows:

51. On 15 February, 2016 Mr Wood filed an affidavit deposed by himself in which he sets out the reasons for his Facebook post. In that affidavit, he gives three reasons for his Facebook post, namely:

a. his moral abhorrence to racial discrimination and his concern that “racial segregation was policy administered on the campus of my university”;

b. his concern that his HECS fees were being applied to provide a facility which excluded particular racial or ethnic groups from using; and

c. his concern that the first respondent’s policy impacts upon the opportunity for interaction between students from different backgrounds which he considered to be invaluable and an important aspect of his university education.

41 His Honour also noted that Mr Wood had sworn that he had not known of Ms Prior’s race or ethnicity. I am not sure that this proposition is supported by the evidence, but it seems that the case was conducted on that basis.

42 His Honour concluded that in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, Mr Wood’s sworn evidence established a prima facie case for granting summary judgment. His Honour also concluded that even if the post was “capable of being seen as offensive or insulting, or amounting to humiliation or intimidation”, it could not amount to more than a “mere slight” and was thereafter not capable of constituting the conduct described in s 18C(1)(a).

43 This view seems to have been derived from, but may misstate the words used by Kiefel J in Creek at [16]. Her Honour did not mean that conduct found to be offensive, insulting, humiliating or intimidating might be dismissed as a “mere slight”. Rather, her Honour meant that a mere slight could not reasonably have an offensive, insulting, humiliating or intimidating effect. In any event, his Honour clearly understood that conduct which was a “mere slight” would not engage s 18C. In any event, Ms Prior does not suggest that she wishes to appeal on that basis.

44 At [58] the primary Judge concluded that Mr Wood had established that Ms Prior had no reasonable prospect of success against him.

Mr Powell

45 As may be seen from exhibit 1 below, there was another post by Mr Wood upon which Ms Prior does not directly rely. There were a number of posts by other persons whose names have been redacted. Some of those posts were arguably racist. None was particularly insightful. Mr Powell then posted:

I wonder where the white supremacist computer lab is ...

46 Mr Powell made three further posts upon which Ms Prior does not rely. I need not set out their contents. Mr Powell’s next relevant post reads, in context, as follows:

... [author redacted] By the logic in this thread: University is also a club with inclusion/exclusion criteria. Therefore you’re all a bunch of segregationists.

...

By ... [author redacted] logic its also fine to start a KKK Klub ...

...

Jackson Powell Michael McGrath, it’s white supremacist, get it right. We don’t like to be affiliated with those hill-billies.

...

47 Later posts addressed arguments for and against the provision of facilities for discrete groups. In the course of those posts Mr Powell posted a further statement upon which Ms Prior does not rely. It is, in any event, incomprehensible. Other posts followed, including the following:

... [author redacted] We need a room strictly for white males, so I can wear my fedora and wallet chain without being mocked. I’m being oppressed here!

Mr Powell then posted:

... today’s your lucky day, join the white supremacist group and we’ll take care of your every need.

...

48 At [62] his Honour explained the term “white supremacist” as follows:

The reference in each of those posts to “white supremacist” is plainly a reference to a racist ideology that promotes the belief that “white” people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds and that “white” people should politically, economically and socially rule people of other racial backgrounds. To ordinary and reasonable members of a free and tolerant society such an idea is plainly offensive and insulting.

49 The primary Judge correctly observed that “words and concepts” which are ordinarily insulting or offensive may not engage s 18C(1)(a) if the circumstances in which such words and concepts are such that they are not reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate “in the way envisaged by that subsection”. The reference to the word “envisaged” is, I infer, a reference to the observations by Kiefel J in Creek at [16], as set out above. The primary Judge concluded that the relevant posts were, “a poor attempt at humour”, which may have been in “bad taste”, or which, “could potentially be regarded as distasteful by some persons”. However his Honour concluded that it was not reasonably likely that a person in Ms Prior’s position or that of a reasonable and ordinary member of either group would feel offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by Mr Powell’s conduct. His Honour considered that such person would exhibit characteristics consistent with those which might be expected of, “a member of a free and tolerant society and who is not at the margins of those groups”.

50 Having concluded that the posts would not offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate, his Honour focussed specifically upon the risk of intimidation. The notion of white supremacy, at face value, concerns questions of colour rather than race. However there can be no doubt that racial differences are very much part of it. Having acknowledged that the doctrine of white supremacy is plainly oppressive and insulting, his Honour concluded that in the present circumstances, use of that term was not intimidating.

51 His Honour then turned to s 18C(1)(b), pointing out that Ms Prior did not claim to have met Mr Powell, and that he had sworn that he had never met her. Mr Powell had also asserted that his posts were intended to express his disapproval of “racial or ethnic discrimination”, not of the fact that any student was of a “particular race, colour, or national or ethnic origin”. At [69] the primary Judge observed that there was no evidence which contradicted Mr Powell’s evidence. That proposition, it might be thought, overlooked any inferences available from his relevant conduct. However his Honour immediately made it clear that there was no such oversight. He said that Mr Powell’s evidence “near ties” any such inference. The words “near ties” can only be a typographical error, the intended word being “negatives”. His Honour also found that if the posts were capable of being seen as offensive or insulting or amounting to humiliation or intimidation, they could properly be described as mere slights. I have commented previously upon this line of reasoning. Again, Ms Prior does not seek to appeal on this basis. In those circumstances, his Honour concluded that Ms Prior had no reasonable prospect of success in prosecuting her claim against Mr Powell.

Mr Thwaites

52 In Mr Thwaites’ case no question presently arises as to whether the posting, allegedly made by him, contravened s 18C(1). The question before the Circuit Judge was whether Ms Prior had any reasonable prospect of proving that he posted the text. In support of his application for summary judgment, Mr Thwaites asserted by affidavit that:

until December 2015, he had not seen any of the posts referred to by Ms Prior in her points of claim;

he did not make the post as pleaded in the points of claim; and

the relevant Facebook account was not his.

53 Mr Thwaites gave a reasonably detailed explanation as to the circumstances in which somebody else may have opened an account in his name and posted the relevant text. He had obviously made significant attempts to investigate the matter. Ms Prior seems not to have done so. She offered no evidence concerning the alleged authorship, pointing only to Mr Thwaites’ name and photograph on the relevant post. Counsel for Ms Prior conceded that she had no other evidence as to the authorship of the post, either at the time of the hearing below, or at the time of the hearing before me. Mr Thwaites contended that the post could not, itself, prove authorship.

54 At [73]-[79] his Honour said:

73. In his affidavit filed on 11 February, 2016 Mr Thwaites deposes that he did not post the message. He descends into particularity in his evidence. He provides evidence that demonstrates, on a prima facie basis, that he did not post and could not have posted the relevant message.

74. As senior counsel for Mr Thwaites concedes the fact that he deposes that he did not post the message attributed to him would not suffice to entitle him to summary dismissal of Ms Prior’s claim if there were any evidence to the contrary – however slight or tenuous, just so long as it was not demonstrably implausible or unreliable. However, as he points out, there is none.

75. Ms Prior’s case rests solely on the fact that the name of Mr Thwaites is associated with the relevant message as its author and the inferences that might be drawn from that. But that fact that his name appears upon the post is not evidence of his authorship. Senior counsel for Mr Thwaites submits that in legal cognisance, the message posted in the name of Mr Thwaites is an unproved document, conceptually no different from a typescript letter with a typescript “signature”, or a document created by cutting letters from newspaper headlines and pasting them on a blank page. Until there is proof regarding the document’s true authorship, its contents have no probative value; and, for that very reason, one cannot prove the document’s authorship solely from the document itself. To put matters in a slightly different way: the issue is whether or not Mr Thwaites was responsible for the contents of the document. Until that is proved, the document is merely unsourced documentary hearsay, placed on the computer screen through the agency of Facebook. If it is proved that Mr Thwaites was responsible, then the document can be tendered against him. But the document, itself, cannot afford such proof, since its admissibility as an admission against interest depends on its authorship first being proved from another source.

76. I accept those submissions.

77. As I have already recorded, the authorities make it clear that, on an application like the present one, where the party seeking summary dismissal files evidence which would entitle that party to judgment, the onus shifts to the party resisting the application to adduce some evidence to the contrary. On the present application, Ms Prior has not adduced any evidence supporting her claim against Mr Thwaites. As senior counsel for Mr Thwaites points out, that failure has occurred in a context where Ms Prior was required to file her evidence in chief by 4:00pm on 1 March, 2016. She did so, but her legal representatives have chosen not to read any part of that evidence in chief on the hearing of the present application.

78. There is no evidence that would put in contest the factual assertions made by Mr Thwaites.

79. In my view he is entitled to summary dismissal of the claim made against him by Mr Prior.

THE PROCEDURE FOR COMMENCING AN APPEAL

55 Pursuant to s 24(1)(d) of the Federal Court Act, this Court has jurisdiction to hear appeals from judgments of the Circuit Court. Pursuant to s 4 of that Act, the word “judgment” means, relevantly:

a judgment, decree or order, whether final or interlocutory.

56 However, pursuant to s 24(1A) of the Federal Court Act, an appeal may only be brought from an interlocutory decision by leave of this Court, or a Judge of this Court. Section 24(1D)(ca) of the Federal Court Act provides that for presently relevant purposes, an order under s 17A of the Circuit Court Act is an interlocutory judgment. The decision under appeal was made pursuant to that section, and so Ms Prior requires leave to appeal against that judgment. Pursuant to r 35.13 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 such an application must be made within 14 days after the date on which the judgment was pronounced. Ms Prior failed to apply within that time. Rule 35.14 provides that she may seek an extension of time in which to apply for leave to appeal. Ms Prior now seeks such an extension of time. If that extension is granted, then she will seek leave to appeal. If the Court grants leave it will, at a later time, hear her appeal.

57 The process may seem complex, but it is designed to ensure that if there is to be any attempt to upset a decision, it is commenced promptly, and to exclude unmeritorious appeals.

extension of time

58 The relevant rules required that Ms Prior file any application for leave to appeal against the primary Judge’s decision within 14 days of 4 November 2016, that is on or before 18 November 2016. Her application for an extension of time was filed on 30 November 2016. The only explanation for the failure to file the application in time appears to have been that Ms Prior’s solicitor was not familiar with the relevant rules. Of course it is a solicitor’s duty to be familiar with such rules. A solicitor is not entitled to rely on casual remarks by the Court concerning time limits. Nor may a solicitor complain about accurate information provided by registry staff, if the solicitor misunderstands the way in which that information applies to the case in hand. Counsel for Ms Prior pointed to the relatively short time that had elapsed between the expiry of the relevant period and the filing of the application for an extension of time. None of the respondents asserts any prejudice resulting from the delay. However I accept the submission made by counsel for Messrs Powell and Thwaites that no real explanation has been offered for such delay, other than that of solicitor’s error.

59 Where there has been delay, the overall history of the matter may be important. I have already pointed out the delays between the occurrence of the conduct in question and the commencement of these proceedings. I should add that Mr Wood and Mr Thwaites only became aware of Ms Prior’s complaint in late July 2015. Mr Powell became aware of it in late August 2015. It seems that Ms Prior’s solicitor, QUT and the Commission all knew that the respondents had not previously been notified of the proceedings in the Commission. To say the least, it is surprising that those parties assumed that it was appropriate to proceed in that way. Although the respondents do not allege prejudice flowing from the delay in applying for leave to appeal, one cannot but wonder why they were so treated.

RELEVANT CONSIDERATIONS

60 In determining whether to grant leave to appeal, the Court will generally consider:

whether in all the circumstances the relevant decision is attended by sufficient doubt to warrant its being considered by an appeal court; and

whether substantial injustice would result if leave were refused, supposing the decision to be wrong.

61 The two considerations may overlap. Each case must be considered on its merits.

62 In considering whether to extend time in which to seek leave to appeal, the Court will consider whether there is sufficient prospect that leave to appeal would be granted as to warrant any such extension. Another consideration is whether there has been an adequate explanation for any period of delay in seeking leave to appeal. Where there has been minimal delay, an extension of time will generally be granted, unless any appeal would be hopeless. The Court will extend time only in order to do justice as between the parties.

PROPOSED grounds of appeal

63 In support of the application to extend time, Ms Prior identified the following proposed grounds of appeal:

1. The learned primary Judge, in finding that the Facebook posts by [Mr Wood] were not reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate [the student group] erred in law in failing to consider whether the hypothetical representative of the [student group] may be offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by the contention by [Mr Wood] that the QUT should not provide them with the benefit of a special measure in the form of a designated computer laboratory.

2. The learned primary judge erred in law in concluding that [Mr Wood] did not make the Facebook posts because of the race of [Ms Prior] or the [student group] based upon the subjective expression of the motive of [Mr Wood], when he should have found that the fact that the room is set apart for persons of a particular race is one of the reasons for the comments being published or that this was an issue that required a trial of the matter.

3. The learned primary judge erred in law in concluding that [Mr Wood] did not make the Facebook posts because of the race of [Ms Prior] by taking into account the fact that [Mr Wood] did not know of [Ms Prior's] race, as evidence supporting the conclusion that the publication was not because of race, when the primary judge ought to have found that the publication was because of the setting aside of a space for the race group and therefore also because of the race of [Ms Prior] or ought to have found that this was an issue which required a trial of the matter.

4. The learned primary judge erred in law by unreasonably concluding that the words published by [Mr Wood] and [Mr Powell] were not reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person in the position of [Ms Prior] or a hypothetical representative of the [student group] because he failed to [consider] the cumulative effect of the whole of the postings in Exhibit 1, including the postings of [Mr Wood] and [Mr Powell] upon a person in the position of [Ms Prior] or a hypothetical representative of the [student group].

5. The learned primary judge erred in law in his conclusion that the words published, in the circumstances in which they were published by [Mr Wood] and [Mr Powell], did not have an intimidatory effect, in that he failed to consider, or demonstrate any consideration of, the effect upon the self-esteem or dignity of members of the [student group] the subject of the publication of the discussion of the idea that they should not be entitled to the benefit of a special measure in the form of the provision of a computer laboratory.

6. The learned primary judge erred in law in arriving at an unreasonable conclusion, without an expressed basis, that references to segregation by [Mr Wood], in the context of a discussion about the entitlement of the [student group] to a designated computer room, was a mere slight, not amounting to humiliation or intimidation, when he should have concluded that it was humiliating and intimidating, in the sense of lowering self-esteem and demeaning the [student group].

7. The learned primary judge erred in law by unreasonably concluding, without an expressed basis, that the reference to a white supremacist computer laboratory by [Mr Powell], in the context of a discussion about the entitlement of the [student group] to a designated computer room, was a mere slight, not amounting to humiliation or intimidation, when he should have concluded that it was humiliating and intimidating, in the sense of lowering self-esteem and demeaning to the [student group], and was aggravated, rather than diminished, by a characterization of the words as having an element of humour.

8. The learned primary judge erred in law by unreasonably concluding that the evidence demonstrates, on a prima facie basis that [Mr Thwaites] did not post and could not have posted the relevant message insofar as stating that the fact his name appear upon the post is not evidence of his authorship when he should have concluded that [Mr Thwaites'] image also appears in relation to the authorship of that post and the image attributed to Mr Thwaites bears a Facebook "tag" in his name and account.

9. The learned primary judge, in refusing to grant [Ms Prior] leave to cross-examine [Mr Thwaites], allowed and relied upon his unchallenged and untested evidence notwithstanding that [Ms Prior] made an application to cross-examine [Mr Thwaites] on the veracity of his affidavit material and therefore erred in failing to allow cross-examination of [Mr Thwaites].

10. In circumstances of the concession by Senior Counsel for [Mr Thwaites] recorded at paragraph 74 of the reasons for decision of the learned primary judge, his Honour erred in failing to allow [Ms Prior] to cross-examine [Mr Thwaites].

11. His Honour erred in stating that "Ms Prior's case rests solely on the fact that the name of Mr Thwaites is associated with the relevant message as its author and the inferences that might be drawn for that" because Ms Prior’s case was that the fact that [Mr Thwaites’] photo accompanied his name identifying the Facebook account as belonging to him.

12. The learned primary judge erred in granting summary dismissal to [Mr Thwaites] in the context of accepting Counsel for [Mr Thwaites'] submissions that "if it is proved that Mr Thwaites was responsible, then the document can be tendered against him," at paragraph 77 of his reasons for decision because the submission demonstrates that the case is not one for summary dismissal but required a trial.

64 In her submissions before me, counsel for Ms Prior advanced three further grounds of appeal. I must consider each ground in order to determine whether any of them raises sufficient doubt about the correctness of the judgment as to justify the grant of leave to appeal, and therefore to grant an extension of time in which to seek such leave.

PROSPECT OF SUCCESS

Mr Thwaites

65 In view of the peculiar nature of Mr Thwaites’ case, I shall deal with his application before dealing with those of Messrs Wood and Powell. In order to do so, I must say something about the conduct of the proceedings at first instance. I may, in some respects, seem to be critical of both the primary Judge and counsel. However the case raised somewhat unusual issues and had received wide publicity, matters which frequently cause problems for judges and counsel. Unfortunately, communications between the legal advisers seem to have become somewhat strained. Further, the primary Judge was apparently under the pressure of other court commitments.

66 In her points of claim Ms Prior pleads against Mr Thwaites:

One hour after the Computer Lab Incident, information was posted on a Facebook page called "QUT Stalker Space" ("Stalker Space") regarding the Computer Lab Incident:

(a) a post by [Mr Wood], stated "Just got kicked out of the unsigned Indigenous computer room. QUT stopping segregation with segregation".

(b) [Mr Powell], posted the following:

(i) "I wonder where the white supremacist computer lab is"

(ii) (in response to a post) it’s white supremacist, get it right. We don’t like to be affiliated with those hill-billies.

(d) [Mr Thwaites], posted "ITT niggers".

67 Mr Thwaites filed a "response" to Ms Prior’s points of claim, asserting that:

I did not make the comment alleged in the application. I expressed this to the applicant during conciliation and to Mary Kelly in 2013 via email.

68 Ms Kelly, an employee of QUT, is also a respondent in the substantive proceedings, but not in the present application. In support of his application for summary judgment dismissing Ms Prior’s application, Mr Thwaites filed an affidavit. In his affidavit, he denied having made the post, asserted that the Facebook account was “impersonating” him, and provided evidence concerning the possible way in which somebody else may have set up a Facebook page using his name and photograph. He also made it clear that he had, on the day in question in 2013, told Ms Kelly that he was not the author of the post.

69 Although, by the time of the hearing below, Ms Prior had filed the evidence upon which she proposed to rely at any trial, none of that evidence was read in opposition to the summary judgment application. Rather, Ms Prior relied upon affidavits by her solicitor, Ms Moriarty, and an affidavit by Ms Hong, another employee of QUT and also a respondent in the substantive proceedings, but not in the present application. Ms Hong’s affidavit is not relevant with reference to Mr Thwaites’ case. Ms Moriarty’s affidavits exhibit correspondence between legal advisers, apparently primarily concerning the conduct of the matter during, and after proceedings in the Commission.

70 Mr Thwaites’ case, both below and on appeal, has been that the existence of the post itself was not evidence of his authorship. Ms Prior seems not to have contradicted that assertion at any time prior to her filing supplementary submissions in response to a matter which I raised with the parties after the hearing of the present application. In her written submissions at first instance counsel for Ms Prior submitted that Mr Thwaites, “maintains that he is not the person who posted the offensive words ...”. Counsel further submitted that Mr Thwaites’ counsel opposed cross-examination of him on the basis that Ms Prior had filed no evidence going to the question of authorship, and that there should therefore be no cross-examination of Mr Thwaites. Counsel for Ms Prior submitted that Mr Thwaites had to be cross-examined on his affidavit in order to, “understand what he was saying and what he was not saying”. She further suggested that he should be cross-examined about the steps which he had taken to report the alleged impersonation. Later in these reasons, I shall deal with the question of cross-examination. In the end, there was no cross-examination.

71 Counsel for Ms Prior did not in the proceedings below, assert that the post was, itself, proof of Mr Thwaites’ authorship. The primary Judge concluded that the content of the post did not prove that Mr Thwaites was the author.

72 Proposed grounds of appeal 8-12 deal with the case as against Mr Thwaites. Proposed grounds 8-11 seem to raise only two criticisms of his Honour’s reasons, namely:

that his Honour failed to consider the fact that Mr Thwaites’ photograph, as well as his name, appeared on the post; and

that his Honour had not permitted cross-examination of Mr Thwaites.