FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd v Clipso Electrical Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 60

ORDERS

First Applicant SCHNEIDER ELECTRIC (AUSTRALIA) PTY LIMITED Second Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent MAZEN ABDUL KADER Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons within 21 days.

2. Stand over for further directions on Tuesday, 7 March 2017.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

[1] | |

[16] | |

3 The Attack upon the Reliability of the Evidence of Mr Abdul Kader | [49] |

[95] | |

[100] | |

[103] | |

[138] | |

[139] | |

[147] | |

[149] | |

6.2 Did the Clipso dolly switch suggest a connexion with the applicants? | [156] |

[167] | |

[171] | |

[189] | |

[194] | |

[198] | |

[215] | |

[221] | |

[233] | |

[234] | |

[246] | |

[252] | |

[258] | |

[259] | |

[263] |

1 This is a trade mark and passing off case about the trade mark CLIPSAL, which is applied by the applicants to light switches and other electrical accessories. The first respondent trades under the mark CLIPSO. The general area of dispute will be obvious.

2 The first applicant, Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd, was originally called Gerard Industries Proprietary Limited. The first use of the CLIPSAL trade mark dates back to 1920 when the first applicant’s founder, Mr Alfred Gerard, developed an adjustable one-size metal conduit fitting. This product apparently provided electrical contractors with a solution to what was said to be the long-standing problem of size variations in metal conduits caused by their being sourced from different nations without a uniform approach to the issue of metal conduit size. It was said of this product that it ‘clips all sizes’, and Mr Gerard therefore called these conduit fittings ‘Clipsal’. The fittings were, by all accounts, a great success. It is not entirely clear what the trading entity was in 1920, but it is known that in 1931 Mr Gerard caused to be incorporated Gerard Industries Proprietary Limited, which kept that corporate style until 2004, when it changed its name to Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd (the first applicant).

3 The marketing director of the applicants, Mr Christopher Quinn, gave evidence that the first applicant had used the CLIPSAL trade mark continuously since 1920, but this seems unlikely given that the first applicant did not exist until 1931. It may be, it most likely is, that the business existed in some other form at this earlier time. What is clear is that the business being conducted under the CLIPSAL mark was expanding. Mr Alfred Gerard’s son, Mr Geoffrey Gerrard, had been responsible for the development in 1930 of the first Australian designed and manufactured switch and the use, in around 1950, of thermoplastics for the manufacture of electrical accessories. The switches, in particular, were very popular. In the 1950s and 1960s more products were developed, such as combined switch socket outlets and vertical combination switched sockets.

4 Although the evidence was not entirely clear on this point, it seems that this increasing range of electrical accessories was marketed largely under the CLIPSAL mark. This business has over time become very substantial. By 31 December 2013 there were, according to Mr Quinn, approximately 14,668 different products produced by the applicants under the name CLIPSAL. In 2011, sales in Australia were in excess of $500 million. These products included goods in categories relating to electrical accessories, lighting, network connectivity and data communications products, cable management products, industrial items, integrated systems and health solutions.

5 According to Mr Quinn, the word mark CLIPSAL has been applied by the first applicant (or its predecessor in title) to the goods manufactured by it since 1920 which, subject to the matter I mention at paragraph [2], I accept. Gerard Industries first registered the word mark CLIPSAL as a trade mark on 27 February 1945, but that mark is not the mark that the applicants rely upon in this proceeding. Instead, they point to registered trade mark no. 506651, which was first registered by the first applicant from 13 March 1989 for the word mark CLIPSAL in respect of ‘All goods in class 9 including telephone apparatus and equipment and accessories therefor included in this class’.

6 I return in more detail below to the issue of how the applicants have used the trade mark in Australia, but it will suffice for now to observe two features of that use. First, the CLIPSAL mark has been affixed in various ways to the products which have been produced by the applicants. Secondly, the applicants principally sell their products to wholesalers. Indeed, as will appear, because many of the products produced by the applicants can by law only be installed by a licensed electrician, there are comparatively few private consumers in the market for those products. There is a significant issue in this case as to how much the demand from contractors is, in fact, reflective of the demand generated by end-consumers. This impacts on the issue of whether the demand for the applicants’ products coming from electrical contractors is really just a form of referred demand from consumers and that, in turn, may have an effect upon the identification of the relevant market participants. I return to this topic below.

7 In December 2003, the first applicant was acquired by Schneider Electric SA, after which it became a member of the Schneider Electric Group. The Schneider Electric Group is a French-based multinational.

8 The title position with respect to the CLIPSAL trade mark no. 506651 was a little obscure. Mr Quinn gave evidence that ownership of the mark (amongst others) had come to Schneider Electric SA in 2003 when it acquired the first applicant, which I took to be a loose statement about ownership through a corporate vehicle. This was at paragraph 17 of his affidavit. At paragraph 78 he said that the mark (amongst other things) had been assigned by Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd to Schneider Electric (Australia) Pty Ltd effective 31 December 2011. The present registration for trade mark no. 506651 records Schneider Electric (Australia) Pty Limited as its owner, but does not record the date upon which this came to be. A printout of the relevant registration itself produced on 5 April 2013 (which was attached to the pleading) records that Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd is the owner, which rather suggests that for some reason the assignment deposed to by Mr Quinn may not have been registered immediately or, indeed, for quite some time. In any event, throughout the times relevant to this litigation, one of the applicants was the registered owner of the CLIPSAL trade mark no. 506651. That being so, the timing of when the transfer occurred is not material to the outcome of the litigation.

9 It is then necessary to say something about ‘Bakelite’ and ‘dolly switches’, which are essential concepts in understanding certain aspects of the dispute between the parties. As to ‘Bakelite’: the broad range of electrical goods manufactured by the applicants includes a category widely known in the trade as ‘Bakelite’. Bakelite includes switches, power points, and mechanisms and accessories. The evidence did not disclose whence came the name ‘Bakelite’, but it seems likely that it is derived from an earlier time when light switches were made from Bakelite, an early plastic made from formaldehyde and phenol. Much of the evidence in the case about the activities of electrical contractors, electrical wholesalers and end-users was concerned with Bakelite in this sense. Despite that, there were still significant aspects of the evidence, particularly those concerned with the constitution of the market and the identification of the relevant trade channels, which were not, by any means, limited to Bakelite.

10 The applicants’ principal case concerned the CLIPSAL word mark no. 506651, but it had a second case on infringement based on a registered shape mark as well. This mark was registered trade mark no. 982758. It was registered in class 9 in respect of ‘Electrical wiring accessories which incorporate a rocker switch; electric switches including dimmer switches; and switched power outlets’. The endorsement on the registration reads:

The Trade Mark consists of the 3-dimensional shape of the switch dolly as shown in the accompanying representations of the mark attached to the application form; the portion of the cover plate shown in dotted lines and from which the switch dolly protrudes, forms no part of the Trade Mark.

11 The attachment consists of a photocopy of a photograph of a switch and some diagrams. The diagrams are not informative but the photograph is. Unfortunately, the photograph has not been reproduced well in the evidence. However, it is clearly a photograph of the applicants’ ordinary light switch, which is a very familiar object in everyday life. During the course of the trial a multitude, perhaps a host, of these switches was tendered. To give a better idea of the shape in the registration, I now include a copy of the grainy photograph:

12 To be clear, it is the shape of the switch which is the trade mark. Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (‘Trade Marks Act’) defines a trade mark to be ‘a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.’ It may not be altogether natural to think of a sign as including a mere shape but the term ‘sign’ is itself a defined one in the Act, and the definition in s 6 extends the idea expressly to shapes. I will call the registered trade mark no. 982758 the ‘Dolly Switch’ mark.

13 The same title issue as between the two applicants which arises in relation to the CLIPSAL word mark also arises in relation to the Dolly Switch mark. For the same reasons, it is immaterial.

14 It was the applicants’ case in relation to the Dolly Switch mark that the respondents had infringed it by, amongst other things, offering for sale switches and sockets with a very nearly identical shape. This sale of Bakelite with a similar switch to the applicants’ mark in a prominent position was alleged, necessarily, to be a use of the switch as a trade mark. Below at [149]-[155], I reject this proposition. The use by the respondents of a switch in the shape of a switch was not use by them of a mark to distinguish their goods. It was instead what it appeared to be, namely, a light switch.

15 These introductory remarks will sufficiently identify the intellectual property involved in the case.

16 It is now useful to set out the position of the respondents more fully. There were two respondents, Clipso Electrical Pty Ltd and its director, Mr Abdul Kader. In their case, the respondents elected to rely upon only the evidence of one substantive witness, Mr Abdul Kader. They also called an expert witness, Dr Cox and three peripheral witnesses, a law clerk and two investigators. As will be seen, Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence was largely, although not entirely, directed to demonstrating the innocence of the circumstances which led him originally to adopt the CLIPSO name.

17 The applicants were, of course, strongly critical of Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence; indeed, they went so far as to denounce most of his account as simply untruthful or, in some parts, as fabricated. Not all of the issues in the proceeding are, however, affected one way or the other by whether Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence is, or is not, accepted. For example, some of the issues concerning substantive identicality as between the CLIPSAL and CLIPSO marks are untouched by whether Mr Abdul Kader innocently happened on the word CLIPSO or not. However, there are many other issues in relation to which Mr Abdul Kader’s reliability as a witness is central. These include direct issues such as the applicants’ contention that the second respondent had acted in bad faith in seeking registration of the CLIPSO mark in the first place. They also include less direct issues such as submissions that the likelihood of the respondents’ conduct in using the CLIPSO name being misleading or deceptive was that much augmented if it were shown, as the applicants submitted it had been, that the respondents had always intended to mislead, or at least confuse, the market by the first respondent’s use of CLIPSO.

18 It is convenient to put the broadsides against Mr Abdul Kader’s credit to one side – at least for now – and to focus in the first instance on the respondents’ version of events, untarnished by the subsequent challenges made to this account.

19 Mr Mazen Abdul Kader was born in 1969. During the course of his cross-examination in this Court, a question arose early on as to his ability to speak English with sufficient fluency to deal with the questioning to which he was to be subjected. It is necessary to record, therefore, and so that that issue may more fully be treated when the time arises, the otherwise extraneous fact that Mr Abdul Kader was born in Lebanon and is not a native English speaker. He first travelled to Australia at the age of 17 – I infer around 1987 – and upon arrival began a course to improve his English. This course he left after approximately four weeks as his teachers told him that he had reached a level beyond which they could not teach. Since that time, he has depended upon his interactions with English speakers to improve his ability to speak English. He felt he was able to read, write and converse in English, although he still had some difficulties in understanding and communicating in spoken English. I return to assess this evidence below at [63].

20 Mr Abdul Kader has over time run a number of businesses. Upon his arrival in Australia, aged 17, he started his first job as a contract cleaner, a job he performed for three years. During this time he was promoted to a supervisor with responsibility for some 16 shopping centres. In 1990 he left this job and set up his own business cleaning offices, shopping centres and hotels which he called ‘Cleantroll’. A year later he obtained a car dealer’s licence and ran a business selling cars for a number of years under the name ‘TMB’.

21 Whilst running TMB Mr Abdul Kader set up, at some point which the evidence does not entirely make clear, a business importing phone systems and parts from Kuala Lumpur under the name ‘Polycom’ (not to be confused with the technology multinational of the same name). He also used the Polycom business to export electronic goods such as DVD players and televisions to Lebanon. Over time this trade dropped off, as I understand until 2005, when I infer it had become minimal.

22 In 2005 he met an electrical contractor who was working on his brother’s house. He was called Mr Mac Ismail. Mr Ismail told Mr Abdul Kader that he had heard from Mr Abdul Kader’s brother that he, Mr Abdul Kader, was involved in the import trade into Australia. He said that he, Mr Ismail, had just become involved in a large project at Rhodes (a suburb in Sydney on the Parramatta River near Strathfield, once an industrial area but more recently rendered residential), and found himself in need of a large quantity of Bakelite power points. In subsequent dealings between the two men, Mr Ismail told Mr Abdul Kader that he was presently obtaining his Bakelite power points from a supplier called HPM for a price of $12 per unit, and that if Mr Abdul Kader could better that price, he would give him the business which Mr Ismail estimated at around $120,000.

23 Mr Abdul Kader says that he had contacts in China which arose from his prior business activities. As a result of these contacts he was put in touch with a man described as ‘Edward’, but whose actual name was Mr Dinghau Zhang. Together with his brother, Mr Changhua Zhang, Edward operated a manufacturing company in China called Hall Electrical Appliances Manufacturing Co Limited. It seems that Edward was indeed able to assist, and Mr Abdul Kader placed an order with him for about $120,000 worth of power points. One curiosity of this evidence is the fact that Mr Ismail ordered $120,000 worth of power points from Mr Abdul Kader, who then placed an order with Edward for $120,000 worth of power points. It is not entirely clear to me how Mr Abdul Kader could make a profit from selling $120,000 worth of power points for $120,000. However, no party made anything about this and it may be put to one side.

24 Mr Abdul Kader was pleased with this transaction, and formed the view that he could run a profitable business importing electrical accessory products from China into Australia. Further discussions with Edward ensued in 2005 and 2006.

25 Mr Abdul Kader says that the power points he imported from Edward had the mark ‘HEM’ on them (HEM is not to be confused with the HPM power points for which Mr Ismail had been paying $12). It is not clear on the evidence what the origins of the mark ‘HEM’ are, although it may be a partial acronym of Hall Electrical Appliances Manufacturing Co (although that would suggest ‘HEAM’ not ‘HEM’).

26 In any event, Mr Abdul Kader suggested, and Edward agreed, that given the growth of the venture he, Mr Abdul Kader, would now set up a business under the HEM name. Mr Abdul Kader was concerned that Edward might go behind his back, and therefore obtained from him assurances that he would not do so. I infer that the concern that Mr Abdul Kader had was the possibility that Edward might use another importer to sell HEM power points into the Australian market.

27 Consequent upon those events, and I infer in around 2005 to 2006, Mr Abdul Kader set up the HEM Electrical Accessories business, with the avowed purpose of importing HEM branded electrical accessories into the Australian market. The business appears to have been successful. By mid-2007, Mr Abdul Kader had set up distribution outlets in Southport in Queensland, Dural and Castle Hill in New South Wales, and in Western Australia (evidence given under cross-examination suggested that these distributorships may have been more in the nature of joint ventures with independent third parties). On 20 December 2006, Mr Abdul Kader applied for registration of the mark ‘HEM’, and not long after he opened a showroom at Revesby along with a warehouse. On 30 May 2007, HEM Group Australia Pty Ltd was incorporated, and Mr Abdul Kader became one of its directors, along with a Mr Bilal Ali El Akde, who apparently provided financial assistance to Mr Abdul Kader in setting up the company. According to Mr Abdul Kader, he and Mr El Akde have not spoken since 2012, which was said to explain why Mr El Akde had not been called to give evidence in the proceeding.

28 For a time the business of HEM Group appears to have flourished. In 2007, HEM Group and Hall Electrical concluded an agreement whereunder HEM Group would import Hall Electrical’s electrical products emblazoned with the HEM mark for a period of six months for distribution through the centres at Revesby and Castle Hill in New South Wales, Southport in Queensland and Osbourne Park in Western Australia.

29 At around the same time, it seems that Mr Abdul Kader wished to conclude an exclusive import agreement with Hall Electrical, but unfortunately Edward appeared not to be interested in doing so. Mr Abdul Kader says that in order to protect his own interests against the evasions of Edward, he decided to apply to register another trade mark, ROYO. According to his affidavit, Mr Abdul Kader’s plan was to continue importing HEM products from Hall Electrical but, and here I quote from paragraph 32 of Mr Abdul Kader’s affidavit, ‘to also start manufacturing some electrical products under a different brand, ROYO.’ Evidence subsequently given by Mr Abdul Kader suggested that what he had in mind was not the manufacture of such goods by himself, but instead by other manufacturers in China.

30 Despite Mr Abdul Kader’s doubts about the sincerity of Edward, he was nevertheless able to conclude an exclusive distribution agreement with Hall Electrical in December 2007. Under it, HEM Group was to import US$600,000 worth of stock per year from 1 January 2008.

31 Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence is that despite the exclusive distribution agreement, Edward double-crossed him. He says that he came into possession of an email from Edward to one of Mr Abdul Kader’s own distributors about a meeting that was to take place between them. Afterwards, it appeared to Mr Abdul Kader that the distributors were attempting to deal directly with Edward, thereby cutting him out. An unsatisfactory telephone call with Edward ensued, and Mr Abdul Kader then travelled to China to see if he could sort out the problem on the ground. He could not. He was told his contract was worthless because it was only enforceable in the courts of New South Wales. Disappointed by the actions of Edward, Mr Abdul Kader then placed orders with another Chinese manufacturer to produce electrical accessories under the name ROYO. However, in 2008 this venture was brought to a close when the registration of the ROYO mark was refused.

32 It is at this point that the CLIPSO mark enters the story. In light of the events with Edward and the failure to secure the registration of ROYO, Mr Abdul Kader says that he again needed to formulate a new brand name. He identifies in his evidence a time in May 2008 as the time that he first conceived the CLIPSO name.

33 That conception took place as follows. Mr Abdul Kader was aware of the IP Australia website and the lists of goods it contains for each class of goods within the register of trade marks. In particular, he was aware of the list for class 9 goods as a result of his efforts to secure registration of the word marks HEM and ROYO in that class.

34 As it happens, the list of class 9 goods has approximately 10,000 entries in it. Mr Abdul Kader says that as he read through the list he noticed the word ‘clip’ was mentioned in it. He himself had heard the word ‘clip’ used frequently in the electrical accessories market. In his affidavit he identified three such uses:

the name of a number of specific products such as a cable clip;

as a reference to a type (or I infer kind) of product such as a ‘clip-in’ mechanism. This related to products which clipped on to other products; and

as a description of an action such as ‘clips on to’.

35 As a result he believed that the words ‘clip’ and ‘clips’ were common words in relation to electrical accessory products. He determined therefore to use the words in his new brand.

36 Inspired by his earlier selection of ROYO, Mr Abdul Kader decided that he would put the letter ‘o’ on the end of ‘clip’ or ‘clips’. I deal later in these reasons with the evidence of Dr Felicity Cox, an Associate Professor of Linguistics at Macquarie University. But it is useful to note at this stage that one aspect of her evidence was the interesting fact that the common Australian practice of colloquially implying familiarity with an object by putting a letter such as ‘o’ on the end of it (e.g. ‘kiddo’ for ‘kid’) is known as a hypocoristic. Later in these reasons, I wrestle with the issue of whether CLIPSO is a hypocoristic.

37 In the end, Mr Abdul Kader preferred CLIPSO, in part because it sounded short, snappy and catchy. He then carried out a search on the internet in relation to the word CLIPSO, and the only reference (the only significant reference, I think) was to a company in France which made ceiling coverings. Having done that, he then ascertained through the ATMOSS search engine that the word CLIPSO was not registered in any class.

38 He next attended to the creation of a logo based on the word CLIPSO. This he appears to have done in late October 2008 by consulting a business in Punchbowl called ‘Compuhouse’. As a result, by 22 October 2008 Mr Abdul Kader possessed a logo for the CLIPSO mark.

39 He then prepared an application for the registration of a trade mark which he lodged on 27 October 2008. He was informed approximately a month later that the registration had been approved. In fact, the word CLIPSO was registered in class 9 in relation to a broad range of goods, mostly associated with switches, on 27 October 2008.

40 Mr Abdul Kader does not deny that prior to the lodging of the CLIPSO registration application in his own name he was aware of the CLIPSAL name. His specific affidavit evidence about this was as follows (at paragraph 62):

Prior to applying to register the CLIPSO trade mark, I had an awareness of the ‘Clipsal’ name but I do not recall knowing much, if anything about the CLIPSAL brand. I had not seen the CLIPSAL brand or the logo. At the time I applied to register the CLIPSO trade mark, I believed that HPM was the only large manufacturer and distributor of electrical accessory products as I had heard about the HPM brand often in my dealings with electricians and wholesalers at HEM Group’s show room.

41 The day after he was notified of the successful trade mark application, Mr Abdul Kader had a further discussion with his business partner, Mr El Akde, in which he relayed his success in securing the registration of the mark CLIPSO. Upon being told the good news, Mr El Akde queried whether Mr Abdul Kader had not perhaps heard of Clipsal. To this Mr Abdul Kader said he replied:

I didn’t even think about them. IP Australia has approved it. If there was a problem it would have been rejected like ROYO and HEM were. We’ve got to keep moving. We have so many orders now. IP Australia think it is ok, otherwise they wouldn’t register it. I don’t think there’s a problem.

42 Mr El Akde’s query did not deter Mr Abdul Kader from the use of the CLIPSO mark which he had, by then, just succeeded in registering. Indeed, his evidence was that by October 2008, he had an urgent need to use the CLIPSO mark. That urgency arose because as at that date HEM Group had around $600,000 to $700,000 of orders for products, but no brand physically to affix to them.

43 I have experienced some difficulty in understanding why that might be so. The evidence that Mr Abdul Kader gave suggested that the difficulty with Edward and Hall Electrical was not a refusal to supply the accessories, or even a termination of the distribution agreement. Rather, it was a failure on the part of Hall Electrical to honour the exclusive nature of the arrangement. I can perhaps understand why Mr Abdul Kader might not have wanted to have persisted with an import arrangement which was not exclusive, but Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence did not suggest that he had terminated the agreement for that reason. Ultimately, I think I must conclude that it is to be inferred from Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that through some process, unclear to me, the arrangement with Hall Electrical had been terminated.

44 Making that assumption, Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that he needed a new brand in October 2008 makes more sense. He decided that the new brand should in principle be operated by a new entity. This entity, which was to become Clipso Electrical Pty Ltd, did not come into existence until December 2008. Prior to that time, Mr Abdul Kader says the business was in part conducted by his other business, HEM Group.

45 It was in these circumstances that the Clipso business came into existence. Mr Abdul Kader gave evidence about two aspects of the business which it is now useful shortly to describe. The first concerns the structural or administrative arrangements which were put in place to facilitate the manufacture, import and distribution of the Clipso products. The second concerns the marketing steps taken by the respondents to promote that business.

46 As to the business structure, from about November 2008 it seems that Mr Abdul Kader was able to procure the services of Hepol Electric Enterprises in Wenshou in China as a manufacturer. Mr Abdul Kader met with someone from this company called ‘Steven’ in China to provide him with the relevant Clipso materials. By January 2009, the issue of packaging had been resolved. It is a little difficult to be clear but it seems, on Mr Abdul Kader’s account, that Hepol produced the accessories in question for around six months only. After that, in around mid-2009, Mr Abdul Kader seems to have set up his own manufacturing operation in China under the name Ningbo Clipso Electric Co Ltd. Since then the business has expanded. Mr Abdul Kader gave evidence that, as required by law, the electrical accessories thus imported by the respondents were properly approved by the relevant authorities. The applicants disputed this. I deal with this issue later.

47 In terms of marketing activities, Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence was that these included the maintenance of a website, the Clipso packaging itself and its product catalogues, four volumes of which found their way into evidence. These were distributed to electrical wholesalers. Mr Abdul Kader said that he did little advertising and relied upon word of mouth in the electrical accessories market.

48 Correspondingly, it was his evidence that Clipso was not marketed to the general public. He regarded his market as consisting of electrical contractors and electrical wholesalers. It was illegal for non-qualified persons to install his accessories and he did not sell directly to the public. He did not think that electrical contractors or wholesalers were confused between Clipso and Clipsal, and he was unaware of any complaints to that effect.

3. The Attack upon the Reliability of the Evidence of Mr Abdul Kader

49 The credit of Mr Abdul Kader was one of the central themes during the trial. The applicants’ basic proposition was that Mr Abdul Kader had decided to choose the name CLIPSO precisely because of its similarity to CLIPSAL, and precisely because he wished to exploit the applicants’ reputation. If made good, that proposition would serve on two fronts. First, it would establish that the CLIPSO mark had been registered in bad faith, thereby providing a ground for its removal from the register. Secondly, it would corroborate the raft of allegations concerning the misleading nature of the CLIPSO mark, because it was said (perhaps by me during argument) that it might more readily be inferred that the use of CLIPSO was, in various ways, misleading if it had always been Mr Abdul Kader’s intention to mislead.

50 It is implicit in the applicants’ submissions on bad faith that acceptance of them would entail the wholesale rejection of the detailed account Mr Abdul Kader has given of how he happened upon the name CLIPSO and his reasons for doing so. It would mean that a significant portion of his evidence on this issue was not just incorrect, but knowingly false.

51 Such a finding would be a strong one indeed, and would involve a most serious traduction of Mr Abdul Kader’s credit. Given the extent and deliberate nature of the falsity which is alleged against him, it is as well to recall that the seriousness of the conclusions for which the applicants contend must be kept in mind in assessing their correctness. Put another way, it would be surprising and quite out of the ordinary for a party to this kind of litigation entirely to fabricate an account of how a brand came to be formulated: cf. s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336. In what follows, I keep that firmly in mind.

52 A critical step along the way to resolving this issue is the observation that a central part of Mr Abdul Kader’s account appears to me to be very, very unlikely, although perhaps not altogether impossible. The observation concerns his evidence that he knew very little, if anything, about the Clipsal brand at the time that he applied for registration of CLIPSO.

53 The difficulty arises from two sets of facts. The first is the fact that by the time Mr Abdul Kader came to be applying for the registration of the CLIPSO mark in October 2008, he had been importing electrical accessories into the Australian market from China since 2005, and had distributed the Bakelite products thus obtained through his distribution outlets in Queensland, Western Australia and New South Wales. Mr Abdul Kader accepted during cross-examination that by this time his business had expanded significantly, and that he had a ‘huge’ market. Further, he had regular contact with electricians in his showroom.

54 The second set of facts concerns the position of the applicants in the electrical accessories market. Evidence was given by their marketing director, Mr Quinn, that approximately 90% of electrical wholesalers in Australia sold goods under the name of CLIPSAL. Indeed, Clipsal is the market leader in the Australian electrical switches and sockets market according to an electrical wholesaler, Mr Micholos, who was called by the applicants. He thought that Clipsal products accounted for 90% of the light switches and power points sold in his business. Mr Quinn’s more precise testimony was that in around 2013 to 2014, Clipsal held 77% of the market, and the next biggest brands, HPM and Legrand, held 11%. The applicants’ market share was worth around $523 million in 2011 according to Mr Quinn. Reflecting that large share was the fact that the applicants spent approximately $13 million on marketing in 2010. None of this was really in dispute, a fact which, in another part of the case to which I return, led Mr Abdul Kader to submit that the CLIPSAL mark was indeed so famous in the trade that there was no likelihood of anyone (or at least any electrical contractor) being deceived by the CLIPSO mark (and yet seemingly not so famous that he himself had heard of it).

55 It is, I think, inconceivable that in the three years that Mr Abdul Kader was importing Bakelite products into Australia, he could have remained as ignorant of the clear market leader, Clipsal, as he endeavoured to suggest. Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that he regarded HPM as the only large brand in the electrical accessories market just cannot be correct. Mr Abdul Kader was involved in the conduct of a large importation and distribution business in the very same market for over three years.

56 Mr Williams SC, for the respondents, valiantly sought to emphasise that the electricians that Mr Abdul Kader had dealt with (such as Mr Ismail at Rhodes) had only used HPM products, and suggested that this explained why he was not familiar with the Clipsal brand. He simply had not encountered any electricians who used Clipsal products. However, this evidence is unbelievable. Mr Abdul Kader’s business of importing and distributing substantial quantities of Bakelite products into the Australian market through multiple distributors makes the idea that in three years he did not become aware of the Clipsal brand literally incredible.

57 The second reason to reject Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence was that he gave false evidence as to whether his products were sold from the first respondent’s website. At paragraph 75 of his affidavit, Mr Abdul Kader gave evidence about this website. It is maintained at www.clipso.com.au. It is the operating website for the first respondent’s business. Mr Abdul Kader gave evidence that the website did not permit purchases to be made on-line. Why would this matter? Had it appeared that the first respondent had, in fact, marketed or sold its products on-line then it would have meant, potentially at least, that it was selling to end-consumers. That contention would have undermined a central plank in its case that its products were only sold to electrical contractors and wholesalers (who could not, on the respondents’ thesis, be misled).

58 The screenshots provided by Mr Abdul Kader of the first respondent’s website provide some support for the idea that sales were not made by means of that website. None of them appears to have involved the usual processes associated with ordering goods on-line. However, in another part of his evidence (where Mr Abdul Kader was attempting to prove that he had used the slogan ‘Clip it to your daily life’ on the website in 2011), he attached a screenshot which contains a logo with a shopping trolley on it adjacent to the words ‘FREE shipping on ORDERS’. This is inconsistent with the idea that orders could not be placed.

59 Mr Abdul Kader’s answer to this when challenged about it under cross-examination was to suggest that the screenshot related to a Chinese website. Two aspects of that explanation are unsatisfactory. First, the domain name on the screenshot is www.clipso.com.au, which is an Australian domain name. Secondly, the purpose of Mr Abdul Kader’s reference to this screenshot was to illustrate this aspect of his affidavit evidence:

99. The slogan ‘clip it to your daily life’ was printed in the first edition catalogue and can be seen under the CLIPSO mark on the cover and the inside cover, which are at page 65 and 66 of MAK-1 (TAB 14). In addition to the brochure, we also included this slogan on our website www.clipso.com.au at this time. Screenshots of the www.clipso.com.au website, from 2 May 2011 (taken from the Wayback Machine) showing the slogan present under the CLIPSO mark can be seen at page 275 of MAK-1 (TAB 18).

(Emphasis in original.)

60 The screenshot is the document at page 3425 of the Court Book. Mr Abdul Kader’s suggestion that it was from a Chinese site makes no sense in the context of this paragraph.

61 Further, and worse, Mr Abdul Kader was confronted with a statutory declaration that he had himself sworn in 2010. It contains a discussion of the first respondent’s website. At paragraph 13 it says that ‘The Website allows customers to people (sic) to purchase the products online in (sic) and they are delivered to addresses in Australia.’ The statutory declaration was admitted into evidence as Exhibit 59. At page 26 of the declaration there are more screenshots of the website as it appeared in 2010. It contains the same free shipping logo as the earlier screenshot. It also clearly displays a tab marked ‘Online Order’.

62 Mr Abdul Kader was confronted with this earlier statutory declaration under cross-examination. In summary: he denied lying in his declaration but stood by his evidence that he had not sold products from the website. As part of one of his answers, he appeared to suggest that the person who had prepared the statutory declaration might have been responsible. I was not persuaded by any of this. I do not accept Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence about it.

63 This is a convenient juncture to mention, as I foreshadowed earlier in these reasons, the question of Mr Abdul Kader’s competency with English. It was clear that his spoken English was not that of a native speaker, but I am satisfied that he understood what was being asked of him. It is true that many of the questions he was asked in cross-examination were at times difficult to follow. I am nevertheless quite confident that on each point Mr Abdul Kader knew precisely what the cross-examiner was groping towards. In that regard, I should record that I regarded Mr Abdul Kader as astute and more than able to deal with the cross-examination. For completeness, I also observed that Mr Abdul Kader was prone to exaggerate his language difficulties on occasions when the questions asked of him raised some difficulty.

64 In those circumstances, I was satisfied that Mr Abdul Kader was lying to me about the topic of on-line sales.

65 I therefore reject Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence as to how he came to choose the CLIPSO name. He was perfectly aware at the time he sought to register the CLIPSO mark in October 2008 of the applicants’ products and of the Clipsal brand. His evidence that he was not was, I regret, false. This does not directly entail that his evidence as to how he came to select the Clipso name itself was false. It is logically possible that he could have been fully aware of the applicants’ products and the Clipsal brand, but nevertheless came up with the Clipso name by the means that he suggested. However, away from the domain of the theoretical, I do not regard this as at all likely, and I find that it did not occur. In particular, if Mr Abdul Kader had been fully aware of the applicants’ products and their Clipsal brand, as I am abundantly satisfied he was, it is factually difficult to imagine him creating the CLIPSO name by reference to the goods in the class 9 list.

66 Save where Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence is uncontroversial or corroborated by documents or independent testimony, I do not accept it. He was an unreliable witness.

67 A number of other credit attacks were made upon Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence. I have reached the conclusion that I should not accept his evidence (other than on the basis just indicated) without recourse to them. Lest, however, any of my reasoning in that regard should prove frangible on appeal, I will record my conclusions on these separate points.

68 The first of these concerns Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence of how he came to happen upon the word ‘clip’. It will be recalled, no doubt, that his evidence in this regard was that he was familiar with the class 9 list as a result of his actions in relation to the HEM and ROYO marks. He had looked at it and noticed the word ‘clip’. He had also heard the word used by electricians and wholesalers.

69 During a sleepy part of the trial the complete 2016 list of class 9 goods made its way into evidence. It contains approximately 10,000 items. The word ‘clip’ appears only eight times in this list. Three of these entries relate to ‘nose clips’ and two are for ‘film clips’. Assiduous attention by those appearing for the applicants to the trade mark applications lodged by Mr Abdul Kader for ‘HEM’ and ‘ROYO’ indicated that the word ‘clip’ did not appear in the HEM application, and only twice in the ROYO application.

70 These matters were said to make Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence unsupportable. It simply could not be correct that he had noticed the word ‘clip’ from examining the class 9 list. Furthermore, in his statutory declaration of 4 May 2010, which was sworn in support of certain opposition proceedings, Mr Abdul Kader gave an account of the background to his selection of the CLIPSO name which was at variance with the version now advanced. Paragraphs 4 and 5 were as follows:

4. A common product sold in the electrical industry is a “clip”, which is an electrical device that clamps onto a power source permitting the transference of electrical currents through the clip to anther device. The term ‘clip’ refers to a number of different styles of clips including, but not limited to, “automotive clips” “battery clips” “cable clips” and “alligator clips”.

5. In determining the name and trade mark I considered a type of products (sic) we would be selling (including clips), the industry usage of the term ‘clip’ and the target demographics. Using this information I derived the name Clipso by adding the letter “o” to the word “clips”.

71 Of course, the class 9 list in evidence was, as Mr Williams correctly submitted, the current class 9 list and not the list as it was in October 2008. However, I can see no reason why there would be any substantial difference between them at least so far as the word ‘clip’ is concerned. No effort was expended in showing that they were different, and I am not prepared to reject this argument on the basis that there might theoretically have been a change.

72 I therefore accept the applicants’ submissions about these matters. The advancement in the earlier statutory declaration of a different version of the source of the word ‘clip’, and the scarcity of the word ‘clip’ in the class 9 list, combine to mean that I do not think Mr Abdul Kader’s account of where he got the CLIPSO idea is plausible. It is another reason to conclude that his evidence is unreliable.

73 The second of the additional credit matters was this. It was said that in 2008 Mr Abdul Kader would have driven down Canterbury Road between his home and his work. If he had done so, he would have necessarily driven past the applicants’ warehouse. Outside of that warehouse was a sign with the Clipsal logo which, it was submitted, Mr Abdul Kader could hardly have failed to have noticed. This meant that his evidence that he had never seen the brand could not be correct.

74 The applicants developed the point this way. Mr Abdul Kader had lived on Greenacre Road since 1998, and drove along Canterbury Road because both the HEM and Clipso offices were on Canterbury Road (as indeed was the Clipsal office). In travelling from his home to his work, he would have needed to have gone past the Clipsal sign. Against this, it was submitted that the sign was, perhaps, not so big.

75 Canterbury Road is a substantial and significant road in Western Sydney. I accept without hesitation that Mr Abdul Kader would have driven along it countless times given the location of his home and his place of work. It is inevitable that he was familiar with the Clipsal sign. Though perhaps not obvious when passed but once, this could not be the case after many trips. Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that he had not been familiar with the Clipsal brand before seeking registration of CLIPSO in October 2008 is false. He was familiar with it because he had driven past the Clipsal sign many times.

76 The third of the additional matters concerned a product not yet mentioned in these reasons, the respondents’ CLIPSMART product. This product was the subject of a patent infringement proceeding originally encompassed within the present case, however, the parties reached a settlement of it. The applicants had relied on two patents, referred to as the 133 Patent and the 135 Patent. In the patent infringement allegations, the respondents pleaded in their defence to the amended statement of claim that ‘until receipt of the letter from the Applicants’ solicitor dated 6 July 2015, the Respondents were not aware of, and had no reason to believe, that patents for the inventions [a USB charging module] disclosed in the 133 Patent and the 135 Patent existed’: paragraph 72(f). Yet the first respondent had, in fact, lodged objections to the 135 Patent on 3 October 2014, which was well before the date of the letter of 6 July 2015.

77 It was said by the applicants that the defence was certified and, indeed, it was certified by the respondents’ solicitor, Mr Breene. Of course, a certified defence is not the same as a verified defence, and this defence certainly was not verified. No doubt, this places limits upon what can be inferred from it. In particular, an unverified pleading cannot constitute an admission: Salena Estate Wines Pty Ltd v Devito (2005) 92 SASR 360 at 368. In this case it seems to me, however, that I can infer that the source of paragraph 72(f) is likely to have been instructions given by the respondents. Although Mr Abdul Kader gave evidence that his son helped him with applications of this kind, this does not diminish my sense that Mr Abdul Kader is very likely to have been the source of the instruction which gave rise to paragraph 72. I would not understand the son’s role of providing assistance to his father as supplanting Mr Abdul Kader’s decision-making role.

78 That would appear to create a conflict between the instructions that I am prepared to infer he gave and the fact that he had lodged earlier objections to the 135 Patent. To this there might be said to be two answers. First, the conflict might be explicable because of the son’s role in assisting with applications of this kind. I would not accept this. As the applicants correctly submitted, the fact that his son was helping Mr Abdul Kader with such matters in fact increased the likelihood of Mr Abdul Kader thereby having a clearer understanding. Secondly, it might be said that at the time of the letter of 6 July 2015, the 135 Patent was not formally in force because it had not been certified. This unattractive proposition may be answered by observing that paragraph 72(f) is not naturally to be read as involving a statement about the legal validity of the 135 Patent.

79 In those circumstances, there is an inconsistency between, on the one hand, Mr Abdul Kader’s instructions that a defence should be filed alleging that the respondents were unaware of the 135 Patent until 6 July 2015 and, on the other, his objection to that very patent nearly two years earlier on 3 October 2014. This reflects negatively upon him.

80 The fourth of the additional matters concerns the operation of an eBay account under the name ‘clipso_direct’. It can certainly be inferred that from this account Clipso products were offered to the public by someone. However, it was not proven to my satisfaction that the account was operated by the respondents or anyone associated with them. I am not prepared to infer from the name alone or the products sold on the website that it was operated by Mr Abdul Kader.

81 The fifth of the additional matters the applicants put forward was the claim that it could be shown that Mr Abdul Kader had dishonestly procured product approvals for some of his products from an electrical regulator. This contention was of some complexity. The first step was to observe that it was Mr Abdul Kader’s contradictory evidence that he had first produced his new Clipso products not only in June 2008 but also in October/November 2008. In Mr Abdul Kader’s favour, I propose to conclude that this inconsistency is clerical, or at least non-substantive, in origin. In my view, given the timing of the trade mark application in October 2008, the October/November 2008 dates are more likely. I do not think that Mr Abdul Kader would have committed to the production of Clipso goods until he was certain that he could use the CLIPSO name.

82 Taking the October/November 2008 date as the relevant one, Mr Abdul Kader then gave evidence that at the time that he designed the new switch (a topic I return to below), he used it on all the switch and socket products produced by HEM Group and Clipso thereafter. The significance of this apparently innocuous fact lies in the corollary flowing from it, viz., that the switches and sockets from that time forward were physically different from the switches and sockets which HEM Group, at least, had been producing up to that time. From the second respondent’s perspective, what was involved was not just a new name affixed to a pre-existing HEM Group product but rather, and instead, a new name affixed to a new product.

83 It will be recalled that in this change over period between HEM Group and Clipso, Mr Abdul Kader had used both entities in relation to getting the new Clipso products to market. Consistently with that evidence, Mr Abdul Kader testified that in November 2008, he applied to the electrical regulator in Victoria, Energy Safe Victoria, for modifications to the certificates held, I think, by HEM Group, but only in relation to a name change to Clipso. The consequence of only seeking a name change in respect of the product was that no new regulatory inspection of the switches and sockets was necessary. On its face, it appears that the respondents relied upon old certificates in relation to the HEM Group goods to obtain certification of the new, and different, Clipso goods.

84 Certificates for products containing these new switches were issued in August 2010. There is no evidence of any such certificates for these new goods before that time. This episode persuades me that Mr Abdul Kader was willing to mislead the electrical regulator, which is consistent with my earlier conclusion that he was willing to mislead this Court. In cross-examination, Mr Abdul Kader was taken to the Clipso 2009/2010 product guide, and shown switches which appeared to be certified under the old certificates. As I have already indicated, that was inconsistent with the fact that the regulator had only been told that there had been a name change (in light of his evidence that the Clipso switches were physically different to their predecessors). The only way for Mr Abdul Kader to escape that inconsistency was to deny that the switches in the product guide were the same product. This he bravely did at T-403, where he suggested under cross-examination that the switches depicted in the guide had a different switch mechanism. But if certified under the old certificates, this must have meant that they contained the old HEM Group switch, in which case Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that once he designed the new switch it was used on all products from that time on, cannot be true.

85 I am satisfied that Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence about this is unreliable and that he is lying about aspects of it. Which aspects he lied about it is difficult to discern. Perhaps he did in fact put the CLIPSO mark on old HEM Group switches and it is his evidence about how the switch was changed when Clipso came along which is false; maybe he really did only put the CLIPSO mark on the newly designed switches, in which case he lied to the regulator that all that was involved was a name change. In either case, Mr Abdul Kader is lying.

86 The upshot is that I accept that these additional matters (apart from the eBay ‘clipso_direct’ matter) each reveal Mr Abdul Kader to be an unreliable witness. I would have been willing to reject his evidence on the basis of any one of them.

87 The conclusion that Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence is unreliable does not, however, logically impel the conclusion that the opposite of his evidence is true. What it means, strictly, is that his evidence does not establish what he seeks to show and that he has lied about it. The former leaves an evidentiary vacuum. What can be drawn from the latter?

88 As many cases in the criminal law show, the fact that an accused person gives false evidence does not necessarily prove that they are guilty of the alleged crime, for they may have other reasons to lie unrelated to the commission of the crime. As was said in Edwards v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 193 at 211:

Moreover, the jury should be instructed that there may be reasons for the telling of a lie apart from the realization of guilt. A lie may be told out of panic, to escape an unjust accusation, to protect some other person or to avoid a consequence extraneous to the offence. The jury should be told that, if they accept that a reason of that kind is the explanation for the lie, they cannot regard it as an admission. It should be recognized that there is a risk that, if the jury are invited to consider a lie told by an accused, they will reason that he lied simply because he is guilty unless they are appropriately instructed with respect to these matters. And in many cases where there appears to be a departure from the truth it may not be possible to say that a deliberate lie has been told. The accused may be confused. He may not recollect something which, upon his memory being jolted in cross-examination, he subsequently does recollect.

If the telling of a lie by an accused is relied upon, not merely to strengthen the prosecution case, but as corroboration of some other evidence, the untruthfulness of the relevant statement must be established otherwise than through the evidence of the witness whose evidence is to be corroborated. If a witness required to be corroborated is believed in preference to the accused and this alone establishes the lie on the part of the accused, reliance upon the lie for corroboration would amount to the witness corroborating himself. That is a contradiction in terms.

(Footnotes omitted.)

89 In this case, I can detect no reason that Mr Abdul Kader would have lied to me about his rationale for creating the CLIPSO name other than that he wished to conceal the true position, which he knew might expose the respondents to liability.

90 If Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence in the case were the only evidence, so that his deceit was itself the only proof that he had selected the CLIPSO name deliberately to exploit the applicants’ mark, it would not be sufficient. The learned author of Cross on Evidence (Heydon JD, Cross on Evidence (10th ed, Lexis Nexis Butterworths, 2015)) observes at [15210] that something more than a mere (dishonest) denial in the witness box is necessary to make good the opposite case. He refers to a statement of Lowe J in Edmunds v Edmunds [1935] VLR 177 at 186 (a divorce case):

… by no torturing of the statement “I did not do the act” can you extract the evidence “I did do the act”. The truth is that there must be evidence aliunde to support the petitioner’s case, before you can use an untrue denial of the parties charged as affording corroboration of that case.

91 However, there is evidence available which could reasonably form the basis for an inference that Mr Abdul Kader selected the CLIPSO mark to exploit the applicants’ reputation in the Bakelite category. That evidence consists of at least two elements:

the fact, as I have found, that Mr Abdul Kader was well aware of the Clipsal brand in relation to Bakelite; and

putting the matter neutrally for the time being, the fact that CLIPSO has a certain resemblance to CLIPSAL. (I return to this topic later in these reasons).

92 That being so, I am entitled to treat Mr Abdul Kader’s dishonest evidence as to how he selected the CLIPSO name as corroborative of the inference to be drawn from those two matters. In my opinion, it is strongly corroborative of that inference.

93 I deal at [171]-[188] with the various similarities between the branding of Clipso and Clipsal. It is enough for present purposes to say that I have concluded that they are deceptively similar, whether looked at in isolation or in the context of the product packaging.

94 In those circumstances, I find as a fact that Mr Abdul Kader selected the name CLIPSO because it resembled CLIPSAL. The reason he did this was because he wished members of the public, electrical wholesalers and electrical contractors to think that there was some association between the Clipso products and the applicants’ products. I draw the inference that this intent was directed at the general public and not just those in the industry because of the fact, as I have found, that Mr Abdul Kader did sell the Clipso products from the first respondent’s website, which was accessible to the general public.

4. Facts relating to the Market

95 There were several factual debates between the parties about the nature of the market for electrical accessories.

96 The first of these debates concerned whether the relevant market was to be seen as involving the broad class of electrical products of the kind enumerated in class 9, or whether it was instead to be seen as limited to a narrower range of Bakelite products. There were several reasons why this debate was significant. One reason was because whilst it was true, generally speaking, that most Bakelite products could only be installed by an electrician, this was not true of the whole of the larger market for electrical accessories. In relation to electrical accessories which did not have to be installed by electricians (for example, electrical switch timers), it was more likely that members of the public would be purchasing the goods themselves.

97 Secondly, even in what I will broadly refer to as the Bakelite market, there was a dispute as to who the market participants actually were. The respondents argued that the vast majority of people involved in the acquisition of switches and sockets were electrical contractors and electrical wholesalers. They denied that any reasonable number of end-consumers ever purchased such products. The relevance of this debate was its service as an entry point for the respondents’ broader argument that the Clipsal brand was so well known to electrical contractors and wholesalers that there was no sensible chance of anyone being misled by CLIPSO. On this view of affairs, to see that one was buying a Clipso product was to know that one was not buying a Clipsal product. As I have already observed, the pursuit of this argument by the respondents was an uneasy bedfellow with Mr Abdul Kader’s evidence that, despite having imported Bakelite into Australia for three years prior to registering CLIPSO and distributing product under it, he was quite unaware of the existence of the clear market leader, Clipsal.

98 The applicants’ response to this nevertheless was threefold. First, end-consumers did actually purchase Bakelite products. Secondly, even in those cases where electrical contractors did the actual purchasing, often enough – particularly at the premium end of the market where some of the Clipsal products were situated – end-consumers who were designing homes would be controlling the decisions as to which switches and sockets would be purchased. In that more complex sense they, too, were to be seen as part of the market. Thirdly, the applicants submitted that even if all that were wrong, their marks, whilst famous, were not so famous that it would be obvious that a similarly branded product was a different product as, for example, might happen with a can of Coca-Cola and a can of Coca-Bola.

99 It is useful to deal with these issues in the order set out above.

4.1 A market for electrical goods generally or Bakelite?

100 One needs to be careful with issues such as this to be clear why one is asking the question. Insofar as the applicants’ trade mark infringement suit is concerned, the 506651 CLIPSAL mark was registered in respect of all goods in class 9. The various questions which arise in the context of that infringement suit that touch upon the effect of the mark on the purchasers of the relevant goods will necessarily have to be considered against a backdrop of all of the goods in class 9. On the other hand, when it comes to the infringement case based on the shape mark no. 982758, the goods in question will be limited to those in class 9 which, as per the registration, are electrical wiring accessories incorporating a rocker switch and so on.

101 A potentially different result obtains in relation to the passing off case and the case alleging breaches of the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’). There the emphasis is on the capacity of the respondents’ conduct to mislead those persons who may reasonably be regarded as acquiring the applicants’ products. No doubt, this will include persons who wish to purchase Bakelite.

102 In both cases, it will be necessary to examine the respondents’ submission that the only people in these markets are electrical contractors or electrical wholesalers. Here the argument was that such professionals could not have been misled by the respondents’ conduct. I deal with that argument below by rejecting it and accepting that insofar as the passing off and ACL cases are concerned, the relevant class of consumer consists not only of industry participants, but also a small group of end-consumers who actually buy switches and sockets for themselves, and another not insignificant group who dictate or otherwise influence the purchasing activities of electrical contractors, architects and builders et cetera engaged on their behalf. The capacity of this non-professional segment of the market to be misled by the word CLIPSO (and the related packaging and logo) needs to be assessed with the proposition in mind that the CLIPSAL mark has a reputation not only in relation to Bakelite but in relation to other electrical accessories too.

4.2 Who are the market participants?

103 This issue arises in relation to the trade mark infringement actions, the claims under the ACL for misleading and deceptive conduct and also those for passing off. It is generated by the fact that the respondents contend that certain categories of persons in the market, such as electricians, would not have been misled by the brand CLIPSO into thinking they were buying Clipsal products on account of their familiarity about, and expertise with, electrical accessories.

104 There is a preliminary, and perhaps obscure, issue as to the reasonableness of the consumers in the market regardless of their expertise. There are statements in cases about trade mark infringement that the issue of deception is to be assessed by asking about the impact of the impugned conduct on ordinary purchasers of the products: see Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 595 per Kitto J.

105 On the other hand, there are statements in relation to consumer claims under the ACL for misleading and deceptive conduct that suggest that the focus is on the impact of the impugned conduct on the ordinary and reasonable consumer or potential consumer: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 656 [53] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ, 661 [78] per Gageler J; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (‘Parkdale’) at 199 per Gibbs CJ.

106 So far as passing off is concerned, the focus is upon the impact of the conduct upon purchasers but excluding from that class ‘careless or indifferent persons’: Norman Kark Publications Ltd v Odhams Press Ltd [1962] RPC 163 at 168 per Wilberforce J (as he then was), cited with approval in the dissenting reasons of Gummow J in 10th Cantanae Pty Ltd v Shoshana Pty Ltd (1987) 79 ALR 299 at 315.

107 I am inclined to the view that the class of purchasers deprived of its careless or indifferent members is the same class as the class of ordinary and reasonable purchasers contemplated for ACL purposes. Although the policy underpinning the ACL provisions is consumer protection whilst that underpinning passing off is the protection of traders, that difference does not provide any principled basis for identifying the classes of person affected by a representation in any different way. On the other hand, the difference between the two actions may well be material when it comes time to consider what kind of representation might be necessary. In particular, there may be subtle distinctions to be drawn between misrepresentations for passing off purposes and misleading and deceptive conduct or conduct likely to have that effect for the purposes of the ACL.

108 For present purposes, it is sufficient to know that the three different actions I have to consider require the market composition issues to be considered not only by reference to ordinary purchasers but also by reference to ordinary reasonable purchasers. In this case, however, I am not satisfied that the position of these two classes is any different. There may be cases where the difference I have just mentioned matters but this is not one of them. The two classes are, in this case, the same.

109 The more substantial issue was generated by the respondents’ argument about who was in the market. All of the various strains of the argument ran into the same conceptual location, which was a contention that the fame of the CLIPSAL name was such that no reasonable electrical contractor or wholesaler would or could be misled by the CLIPSO mark (or packaging or logo) into thinking that what was being purchased was related to Clipsal. All of the applicants’ claims in relation to Bakelite were therefore to be seen as failing because the notional class of ordinary consumers or ordinary reasonable consumers of Bakelite products did not include persons, such as retail consumers, who lacked this specialised knowledge.

110 As the applicants’ case was developed, the class of consumers of Bakelite products was to be seen as including both a sub-group of retail consumers who purchased Bakelite products for themselves and another sub-group of retail consumers, typically engaged in home renovation projects, who were heavily involved in the decision as to which kind, or what brand, of power switch or socket the relevant engaged electrical contractor was to install.

111 An attempt was made in some of the applicants’ evidence to assess just what percentage of the overall market was constituted by end-consumers themselves buying the products. For example, Mr Quinn, of whom mention has already been made, thought that end-consumers were responsible for around 6% of all Bakelite purchases in Australia. The cross-examination of Mr Quinn uncovered several methodological deficiencies in the process by which he had arrived at the 6% figure. I do not propose to set these deficiencies out. The reason for this is that whilst I accept that the respondents’ criticisms of this evidence are well-founded at the level of a numerical analysis, I do not accept that the applicants have failed to show that end-consumers are market participants in the two senses discussed.

112 The reasons for this relate largely to the marketing activities of the applicants, which are very extensive. About those it is now necessary to say a few words.

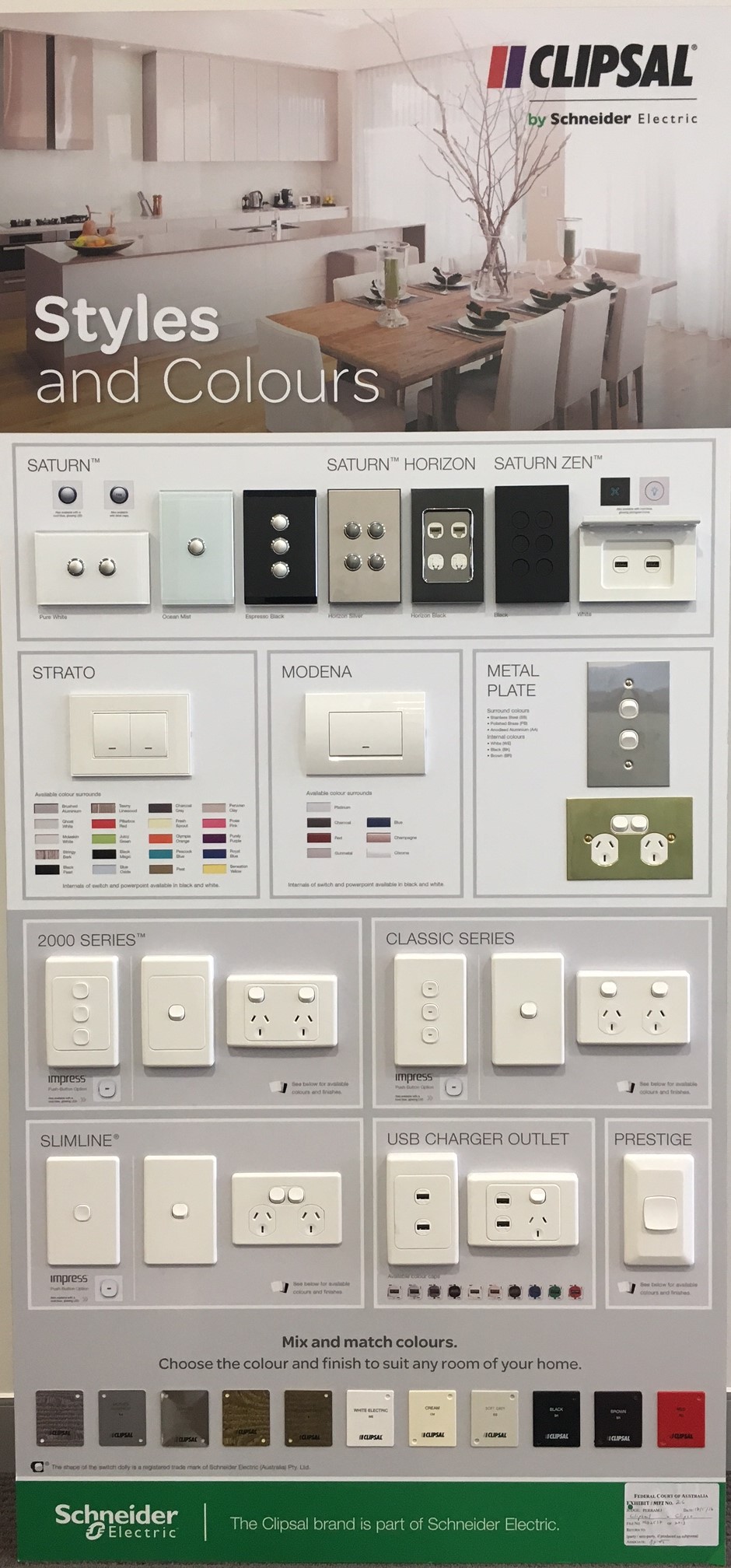

113 For at least ten years or so the applicants have pursued a marketing strategy of causing end-consumers to make decisions about the brand of switch and socket products they wish to see purchased by their electricians. This strategy has been pursued by seeking to market the applicants’ switch and socket products directly to the public. This has included the use of extensive display boards and other point-of-sale paraphernalia (one of which became Exhibit 26). Exhibit 26 is around 1.5m x 0.8m and is festooned with light switches (a photograph of it appears below at [159]). It is plainly directed at persons making design decisions and includes an attractive range of switches, colours and options. These display boards are placed in various outlets such as display centres. Another form of marketing has been a magazine entitled ‘The Essential Checklist’, which has been in production since 2003. One of these (or an extract from it) became Exhibit 33. A quick perusal of this work shows immediately that it is directed to consumers and not the trade. For example, on the front page there are headlines such as ‘Styles and colours to suit your décor’ and ‘How to keep your family safe and secure’. Plainly, these are not directed at the trade. A perusal of the inside of the magazine shows the same thing. For example, at page l4 this story appears:

If you’re building, renovating or improving your home, a licensed electrician will need to be called in at some stage.

However, in most cases, when you are dealing directly with a builder or design professional (i.e. architect), you may never get to speak to the electrician about what you need.

Don’t let others decide

Often electricians are forced to make assumptions about your lifestyle, and guess how you might live in your new home.

If you’re prepared to take your chances that the electrician will guess right, then there’s no need to get involved in planning your electrical requirements. Of course the licensed electrician will do a good job of providing you with a basic wiring installation. However, don’t you deserve your home to be just how you want it? What’s more, it’s likely they’ll use Australia’s own high quality Clipsal electrical accessories – but isn’t it best to be sure?

114 Since 2005, the applicants have also provided a service known as ‘Clipspec’. Clipspec is software that the applicants provide to persons operating various outlets through which its products are sold. It permits the delivery to consumers of what was referred to by Mr Quinn as ‘Clipspec consultations’. Such consultations allow for an interactive planning experience for the consumer. The various outlets include Clipsal’s ‘Powerhouse’ displays, builders’ showrooms, the showrooms of Beacon Lighting (although this has now been discontinued), some electrical contractors and third party businesses who provide advice on designing electrical systems to customers. The process involves the consultant using the Clipspec software with customers to provide information about Clipsal goods. These sessions can last up to two hours. There is no need to expand upon this further. The basic point, which I accept, is that Clipspec is a marketing innovation directed at end-consumers and not the trade.

115 The reference above to Clipsal Powerhouses is a reference to a further marketing innovation. These are display centres operated by the applicants around Australia. There are six. These allow the general public to see the products in situ, and to speak with a consultant if need be. Clipsal has offered Clipspec consultations from these centres since 2006. There are analogous displays by the applicants at trade shows. Similar public-directed marketing activities were also to be seen on the applicants’ YouTube Channel, and through the arrangement it had had with Beacon Lighting.

116 Most important perhaps is the applicants’ website at www.clipsal.com, screenshots of which were in evidence. It was divided on its home page into a section for consumers and another for trade.

117 All of this material shows that the applicants go to considerable lengths to persuade end-consumers to get involved in the decisions about which switches and sockets are to be installed. Mr Quinn gave evidence of his work as the Director of Marketing at Schneider Australia. Around 70% of his time was devoted to the CLIPSAL mark. He had 33 staff, 17 of whom worked exclusively on the Clipsal brand and nine of whom had roles encompassing both the Clipsal brand and that of Schneider. It is obvious that these marketing activities are extensive. In 2013, the applicants spent approximately $13 million on them. Mr Quinn described part of these activities in these terms:

58. Clipsal views the increased involvement of end consumers in the decision-making process as an opportunity to create demand for its premium products. For many years, part of Clipsal’s marketing strategy has been to encourage electrical contractors to “upsell” premium Clipsal Goods to their customers. In the last ten or so years, Clipsal has also started to focus a large part of its marketing on end consumers, the intention being that they will make the decision to purchase, or cause to be purchased, Clipsal Goods (and, in particular, premium Clipsal Goods). In this sense, Clipsal is aiming to create demand for premium products at the traditional end of the supply chain, and either for end consumers to make the purchase themselves or to drive their demand backwards through the supply chain to electrical contractors.

118 He explained the significance of that increased demand as arising for the following reasons:

60. Based on my knowledge and experience, including as outlined at paragraphs 11 and 12 above, end consumers take a different approach to decision-making than electrical contractors when it comes to electrical products. Whilst electrical contractors, who are almost exclusively male, have traditionally focused on factors such as reliability, quality and confidence that a job will be long-lasting, end consumers are more focused on aesthetics and, depending on the product, technological features. Both classes are likely to be focused on pricing issues. For both classes, brand is also important: for contractors it has always been important, whilst it is becoming increasingly important for end consumers.

61. The growing relevance in the last ten or so years of end consumers in the market for electrical products is part of a broader increase in interest in renovation, including “do-it-yourself” (DIY) work. This can be seen in the increased popularity of home shows, generally conducted at trade and exhibition centres. I discuss Clipsal’s participation in home shows further at paragraphs 141 to 142 below. Home renovation television shows have also become an increasingly popular genre in television, and reflect the increasing interest of homeowners in renovating and building their own homes.

(Emphasis in original.)

119 The evidence disclosed that in the 2011 year net sales for Clipsal products (not just Bakelite) totalled $522,910,727. From this one may infer that this is a substantial business, in which a marketing staff of 33 is hardly to be seen as surprising.

120 The point of this digression is that it is reasonable to infer that the strategy of seeking to increase demand at the consumer end and then driving that demand back up the supply chain is likely to have influenced end-consumer decisions to some extent.

121 The critical question, however, is by how much. It does not seem to me that the effect of the strategy pursued by Clipsal can be readily measured. In the case of those consumers who simply give instructions on the kind of switches and sockets they wish to have adorn their new homes, the actual purchase order may be concealed beneath multiple layers of contractors or professionals. The instruction may be given to an architect who may produce plans which instruct a builder who may then instruct an electrical subcontractor. I can imagine no mechanism by which it might be readily ascertained from the simple fact that the electrical contractor purchased a Clipsal accessory that this was the result of the exercise of decision-making further along the supply chain. So too, whilst I accept the bona fides of those of the applicants’ witnesses who tried to estimate how many purchasers in wholesale shops were tradespeople and how many were end-consumers, there are elements of this which must be purely speculative. The critical point at which it breaks down, in particular, is that whilst people who appear by reason of apparel to be tradespeople most likely are, it does not necessarily follow that someone who does not appear to be a tradesperson is not.

122 However, the evidence of these witnesses (the marketing director, Mr Quinn, a store manager of an electrical wholesaler, Mr Kalimnios and the electrical wholesaler, Mr Micholos) nevertheless persuades me that the applicants’ efforts in bringing end-consumers into the process as part of its supply chain strategy are likely to have had some success. The evidence of Mr Kalimnios and Mr Micholos (referred to later in these reasons) was attacked on the basis that the firm for which they worked, P&R Electrical, was not independent of the applicants. It is not surprising that an electrical wholesaler might have a substantive commercial relationship with the market leader in electrical accessories, but I would not describe such a relationship as lacking independence. In any event, I do not think that the evidence of either man was adversely affected by this matter.