FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Drake (No 2)

[2016] FCA 1552

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | PETER CHARLES DRAKE (and others named in the Schedule) First Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application against each of the first, second, and third respondents be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the first, second, and third respondents to be taxed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

EDELMAN J:

TABLE OF KEY PERSONNEL AND ABBREVIATIONS

ASIC | Australian Securities and Investments Commission. The applicant in this proceeding. |

BARNETT, Luke | Development Manager of the Maddison Estate development at LMIM with a background in mechanical engineering and land development. A member of the PAM team since November 2011. He reported to Mr Tickner and, once Mr Tickner left, to Mr Fischer and Mr King. He resigned on 22 May 2013. |

DARCY, Lisa | Initially the fifth respondent. Part way through the trial, ASIC abandoned its case against Ms Darcy. She was Executive Director of LMIM from September 2003 until her resignation on 21 June 2012. Ms Darcy was CFO until recruiting and training Mr Fischer for the role in March 2008. She was also the chair of the MPF Credit Committee and a member of the LMIM board. Whilst at LMIM, Ms Darcy worked closely in the process of instructing legal, signing off on serviceability analysis for all fund loans (including MPF loans), and assisting with Mr Drake’s personal finances. She worked closely with Mr Drake, and was the main contact with Ernst & Young. |

DRAKE, Peter | The first respondent. The Executive Director, sole owner and CEO of LMIM. Chairman of the LMIM board, and a voting member of the MPF Credit Committee. Sole director, secretary and shareholder of LMIM Asset Management Pty Ltd. Sole director and secretary of Maddison Estate. Ultimate beneficial ownership of the shares in Maddison Estate was held by the corporate trustee (LMIM Asset Management Pty Ltd, of which Mr Drake was the sole director and secretary) of a discretionary trust, the beneficiaries of which included Mr Drake. From April 2010, director of Coomera Ridge Pty Ltd. |

ERNST & YOUNG | The auditors of all of LMIM’s funds except for the MPF. Ernst & Young and WPIAS worked with the PAM team and the finance team to look at the feasibilities of development projects. Ernst & Young produced a draft and then final report concerning Maddison Estate, commissioned by Suncorp, in July and then September 2011. |

ESTATE MASTER | A proprietary software program used by the PAM team to prepare feasibility reports. Estate Master required the input of numerous variables and various assumptions such as escalation rates from which it calculated a net present value of the development. |

FISCHER, Grant | An accountant with qualifications in commerce. The CFO of LMIM from March 2008 to August 2012, where he was responsible for the overall financial management of LMIM and its managed investment schemes. As CFO, Mr Fischer had a finance team working for him comprising between five and 11 staff. He reported directly to Mr Drake. Mr Fischer was an Executive Director of LMIM from 14 March 2012 to 12 August 2012, and a member of the MPF Credit Committee. Thereafter, he worked as a consultant to LMIM until January 2013. He only attended one formal LMIM board meeting as a director (on 13 July 2012). |

KING, Scott | An acquisition manager with qualifications in property valuation and economics, and applied finance and investment. Employed as a Development Manager in the PAM team from November 2010 to February 2013. Worked on several projects at LMIM, including ad-hoc involvement in the Maddison Estate development. His involvement included assisting Mr Barnett with the feasibility review in June 2012 after the departure of Ms Scott, at the request of Mr Drake and Mr Fischer. Mr King was a voting member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

KINGSTON, Bronwyn | Employed in LMIM as a paralegal in the commercial lending department, and then in the PAM team. Her role included the provision of organisational and administrative support to the MPF Credit Committee. |

KOP, David | Employed by Suncorp as a Relationship Manager in the property finance department. This position entailed helping Suncorp resolve its portfolio of “non-core” loans via repayment when Suncorp decided to exit the property loan market. Mr Kop was responsible for the management of the Suncorp loan to Maddison Estate from September 2011 to 2013. Mr Kop’s main contacts at LMIM were Mr Tickner and Mr Fischer. |

KURBATOFF, Mark | Employed by Suncorp as a Relationship Manager in the development finance section. Mr Kurbatoff was responsible for the management of the Suncorp loan to Maddison Estate from December 2010 to September 2011 (when it was transferred to Mr Kop). |

LANDMARK WHITE | Commissioned by Young Land Corporation and Suncorp to conduct valuations of Pimpama Land. The valuations were contained in reports dated 6 March 2008 and 28 July 2008. |

LM COOMERA PTY LTD | LM Coomera Pty Ltd was the predecessor company of Maddison Estate. It was incorporated on 14 September 2007. |

LMA | LM Administration Pty Ltd. Incorporated in 1992. Trustee of the LMA Trust. LMA entered into an agreement on 1 July 2005 with LMIM whereby LMA agreed to provide LMIM with services for LMIM’s funds management operations (including the employment of staff). |

LMA TRUST | LM Administration Trust, created on 30 June 2003. LMA was the trustee of the LMA Trust. |

LM GROUP | The LM Group was comprised of various related companies, including LMIM, Oceanboard Pty Ltd, LMA, Maddison Estate, LM Coomera Holdings Pty Ltd and LMIM Asset Management Pty Ltd. LMIM was the principal company of the LM Group. |

LMIM | LM Investment Management Ltd. LMIM was a responsible entity for a number of managed investment schemes, and, in particular, the responsible entity and the trustee of the MPF. Mr Drake was the Executive Director, sole owner and CEO of LMIM. LMIM was made up of a number of teams, including the PAM team (led by Mr Tickner), the finance team (led by Ms Darcy and then Mr Fischer), the marketing team (led by Ms Mulder), the global operations team (led by Ms Phillips), the portfolio management team (led by Mr van der Hoven and Mr Petrik), the foreign exchange team (led by Mr van der Hoven), and the in-house legal team. |

LMIM ASSET MANAGEMENT PTY LTD | LMIM Asset Management Pty Ltd was incorporated on 14 September 2007. Mr Drake was its sole director, secretary and shareholder. It held ultimate beneficial ownership of the shares in Maddison Estate. |

LOUGH, Caroline | Paralegal in the PAM team. |

MADDISON ESTATE DEVELOPMENT | A large residential and recreational development located at Pimpama on the Gold Coast. The plan for Maddison Estate was to sell blocks of vacant land via community title in a large setting which would consist of high tech recreational venues and a town centre. Maddison Estate was previously known as LM Coomera, One, and Arrowtown. |

MADDISON ESTATE | Maddison Estate Pty Ltd. A company related to LMIM who was the receiver of the loan that is the subject of these proceedings. The loan was for a large development project on the Gold Coast (see Maddison Estate). |

McDONALD, Greg | Worked for LMIM as a Development Manager. He was a member of the PAM team, and worked on the Maddison Estate development. |

McCALLUM, Ann | Employed in LMIM as a loans analyst in the PAM team. She was a member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

MPF | The Managed Performance Fund. The MPF was established around 2002 as an unregistered managed investment scheme which operated as a unit trust. LMIM was the trustee of the fund. The MPF was only open to investment by wholesale or sophisticated investors. On 1 November 2011, the MPF information memorandum described it as having 90% of its assets invested in Australian commercial loans. The largest of the commercial loans, $142 million, was a single loan of more than half of the size of the fund. The MPF was governed by the MPF Constitution. |

MPF Credit Committee | A committee of the MPF which assessed loans proposed as investments for the MPF and considered any required action for existing loans. The committee met as required and sometimes informally. Meetings were often preceded by an emailed information synopsis. On 19 May 2011, the committee was comprised of Ms Darcy (the chair), Mr Drake, Mr van der Hoven, Mr Tickner, Ms Mulder, Mr King, Mr McDonald, and Mr Fischer. By 2013, there were six voting members: Ms Mulder, Mr Drake, Mr van der Hoven, Ms Phillips, Mr King, and Mr Petrik. The MPF Credit Committee was alternatively described as “CC”, “Credit Committee”, “MPF Credit Committee”, “MPF Investment Committee” and “MPF Investment CC”. |

MPF Constitution | A deed between LMIM and the members of the MPF as they were constituted from time to time, which governed the MPF. The original MPF Constitution was dated December 2001. Variations were made periodically until October 2012. |

MULDER, Francene | The second respondent. Employed by LMA from 1999. She was appointed as Executive Director and Marketing Director of LMIM in September 2006. Not as actively involved in the asset management side of MPF as other directors. Her involvement was more with client communication. Member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

PAM team | The Property Asset Management (PAM) team which assisted LMIM. The team was headed by Mr Tickner, although Mr Fischer took over for three to four months after Mr Tickner retired as director in 2012. It had at most 25 staff with lending, development, town planning and general property skills. The PAM team was divided into three parts, individually responsible for: (i) identifying investment opportunities for the funds; (ii) assessing the assets and working to progress the projects; and (iii) administering the loans. The PAM team reported to the various committees, including the MPF Credit Committee. In early 2011 to late 2012 the PAM team included Mr Tickner (as the head of the team), Mr Fischer, Mr Parker, Mr King, Mr Barnett, Mr McDonald, Mr Young, Ms Scott, Ms Chalmers, Ms Kingston, Ms Lough, and Ms McCallum. |

PARKER, Michael | A Commercial Lending Manager in the PAM team. He was responsible for considering and obtaining funding opportunities, proposing them to credit committees, and (if the MPF Credit Committee agreed) contracting with and lending money to developers. Mr Parker was a member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

PETRIK, Andrew | Employed in LMIM as Portfolio Manager in about 2009, taking over from Mr van der Hoven. He was a member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

PHILLIPS, Katherine | Employed in the London office of LMIM until around 2011. She was an Executive Director of LMIM from 13 July 2012 to 20 June 2013, as well as head of global operations. Ms Phillips liaised with all LM offices and staff on a regular basis in relation to fund and business operational issues, and was also heavily involved in marketing. She was a voting member of MPF Credit Committee. |

SUNCORP | Suncorp-Metway Limited. Holder of a first mortgage in relation to its loan for the Maddison Estate development. |

SCOTT, Katherine | An accountant with approximately 18 years’ experience. Initially employed by Young Land Pty Ltd, then by LMA from January 2010 to May 2012. She worked in the finance team as a management accountant, and then later moved into the PAM team. |

TICKNER, Simon | Initially the fourth respondent. Part way through the trial, ASIC abandoned its case against Mr Tickner. He worked for LMIM from 2002 as Business Development Manager. He was a member of the MPF Credit Committee, Executive Director of LMIM and head of the PAM team from September 2008 until he resigned on 13 July 2012. After his resignation, Mr Tickner was re-employed as a consultant for the PAM team. |

VAN DER HOVEN, Eghard | The third respondent. Employed by LMA in 2003 as Portfolio Manager until around 2009 or 2010. Executive Director of LMIM from 22 June 2006 until 30 June 2013. A voting member of the MPF Credit Committee. |

WILLIAMS, Reginald | Accountant. Managing partner of WPIAS. Worked on the WPIAS audit of the MPF financial statements in 2011 and 2012 and attended the meeting on 17 July 2012. |

WOOLLEY, Hugh | Funds investment manager with over 31 years’ relevant financial services experience. Called by ASIC to give expert evidence. |

WPIAS | Williams Partners Independent Audit Specialists. Accountants with specialised experience in building, construction, aged care and the audit of managed funds. Specialised knowledge of the Gold Coast property market. Engaged to audit the financial reports for the MPF for the years ended 30 June 2011 and 30 June 2012. WPIAS’ main contact from LMIM was Mr Fischer. |

YOUNG, David | From November 2006 to April 2010, Mr Young was a director of Young Land Corporation Pty Ltd and Coomera Ridge Pty Ltd. From April 2010 until January 2012, he was a consultant on the Maddison Estate Development and worked in the PAM team. |

1 This trial concerned allegations by ASIC of breach of directors’ duties against five directors of a corporate trustee of a managed investment scheme. This introduction explains, in very broad outline, the reasons why I have dismissed ASIC’s case in its entirety. The reason why ASIC’s case is dismissed requires an appreciation of how ASIC ran its case, and the rejection of the entirety of the evidence of the principal expert called by ASIC.

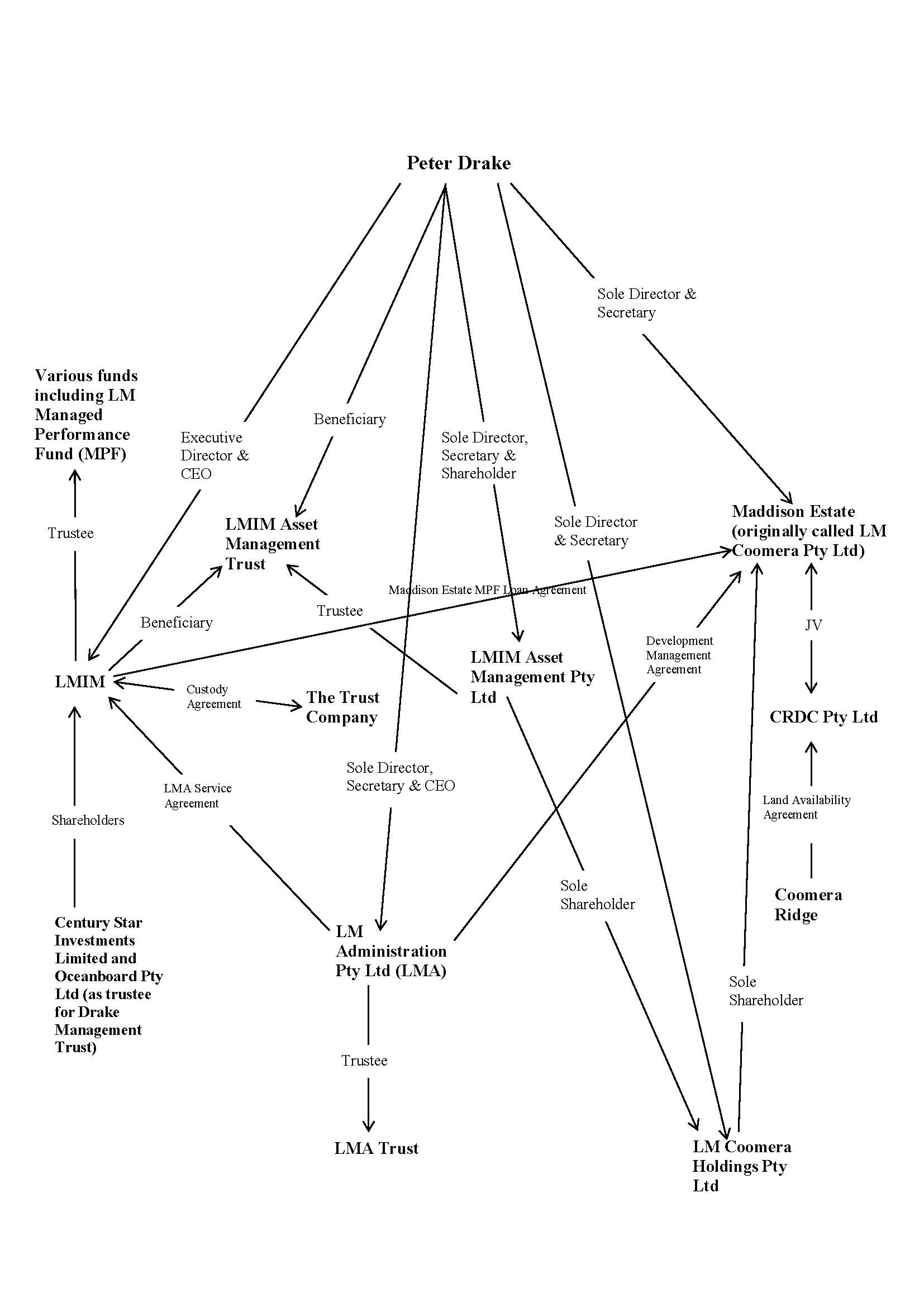

2 ASIC’s case, in very broad outline, was concerned with an investment made by LM Investment Management Ltd (LMIM) as a responsible entity and trustee of numerous funds. LMIM had offices all over the world from which its funds were marketed. Its main office was on the Gold Coast.

3 One of LMIM’s funds was an unregistered managed investment scheme established in 2002, the LM Managed Performance Fund (the MPF). This was an aggressive fund with reasonably high risk. It was aimed at wholesale and sophisticated investors who accessed the fund through financial planners. As one of the former directors of LMIM explained, the MPF was a fund that could have a number of assets including second mortgages and direct property interests. It had a very broad investment mandate. It was marketed as an aggressive fund with higher returns than what was on offer from some other funds including other funds managed by LMIM. After the global financial crisis, some of the MPF loans required a focus upon development because the borrowers in those loans had begun to default on their mortgages. The MPF investments were marketed through means which included information memoranda. The sophisticated investors would have been immediately aware from the information memoranda and investment application that the fund was far from low risk. For instance, on 1 November 2011, the MPF information memorandum described the MPF as having 90.75% of its assets invested in Australian commercial loans. The largest of the commercial loans, $142 million, was a single loan of more than half of the size of the fund. That is the loan which is the subject of these proceedings.

4 The particular investment by LMIM (as trustee for the MPF) with which this case is concerned was a loan made to a related company which became called Maddison Estate. The loan, secured by two mortgages, was for a large development project on the Gold Coast (the Maddison Estate development). The interest rate was eventually set at 25%. The interest rate was designed to ensure that Maddison Estate, which was a special purpose vehicle, did not obtain any of the profit from the development. ASIC did not allege that the loan involved any breach of duty although ASIC alleged that it was, in effect, a disguised equity participation in a development.

5 The loan from LMIM to Maddison Estate (the Maddison Estate loan) was made in November 2007 with an initial limit of $40 million. In 2008 the limit of the loan was increased to $58 million. In 2009 the limit was increased to $70 million. In 2010 it was increased to $95 million. In 2011 it was increased to $115 million. Again in 2011 it was increased to $180 million. Then, in August 2012, it was increased to $280 million (the August 2012 Variation).

6 aSIC did not allege that the loan was imprudent. Nor did ASIC allege that the loan was made by the directors of LMIM without care and diligence. Nor did ASIC allege that there was any breach of duty arising from the approval of the loan variations in 2008, 2009 or 2010. After the conclusion of the evidence, ASIC also abandoned any allegation of breach arising from the loan variation in 2011, and therefore abandoned the whole of its case against the fourth and fifth respondents, Mr Tickner and Ms Darcy respectively. ASIC’s case against the remaining three respondent directors of LMIM, Mr Drake, Ms Mulder, and Mr van der Hoven (the first, second and third respondents respectively), was solely based upon the variation which increased in the loan limit in 2012.

7 The abandonment of ASIC’s case against Mr Tickner and Ms Darcy, and its case concerning the 2011 loan variation, was likely due to the evidence of ASIC’s final witness, the expert witness Mr Woolley. As I explain later in these reasons, Mr Woolley’s evidence was, in the literal sense, incredible. Senior counsel for ASIC very properly accepted that the Court should not accept any of the evidence from Mr Woolley other than where it was essentially unchallenged. Even on those points where there was little or no challenge, ASIC placed very limited reliance upon Mr Woolley. My concerns with Mr Woolley’s evidence were so serious that I do not accept his evidence on any contested matter, even if it was not the subject of any substantial cross-examination. Mr Woolley’s evidence did not merely cause a substantial impairment of ASIC’s case in relation to the 2011 variation. It created substantial gaps in the whole of ASIC’s case.

8 The decision by ASIC not to allege any breach of duty in making the loan, or any breach of duty in any of the series of variations to the loan limit before 2012, was likely to have been based on the nature and terms of the MPF. As I have explained, the fund was reasonably high risk and was only open to wholesale or sophisticated investors who invested through financial advisers.

9 ASIC’s allegations against the three remaining directors were that the directors breached their duties of care and diligence under s 180(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in causing or permitting LMIM to approve the August 2012 Variation. This breach by each director was based on the allegation that each caused LMIM to breach its duties by failing to act as a prudent trustee and that each exposed LMIM to a foreseeable risk of harm, namely civil proceedings by unitholders in the MPF.

10 ASIC’s case concerning why LMIM did not act as a prudent trustee shifted a number of times which made it very difficult to follow. The shifting nature of ASIC’s case was perhaps due to ASIC’s case having been dependent upon Mr Woolley’s evidence. At times during the trial it appeared that ASIC’s case was either that the breach by LMIM, or (at least) a crucial part of the breach by LMIM, was its failure to obtain an independent feasibility report before approving the August 2012 Variation. For instance, ASIC’s expert, Mr Woolley, said that “other than obtaining an independent feasibility analysis of the anticipated future cash flows from the Maddison Estate development, no further inquiries or steps needed be taken by a prudent trustee” ([211], see also [223]-[225]). During oral submissions, senior counsel for ASIC accepted that the allegation of a lack of an independent feasibility report was “crucial” to ASIC’s case (ts 648). Presented in this way, this was an allegation of imprudence by LMIM in the process of approving the August 2012 Variation.

11 An allegation of imprudence in process is a different case from one which alleges imprudence in outcome. In the course of argument, the example I gave to senior counsel was as follows (ts 724). Suppose, in 1976, a trustee decided to invest a large part of a trust fund in a stock beginning with the letter “A”. The trustee seized randomly upon a stock named “Apple”. Suppose also that, at the same time, the world’s most brilliant analysts would have reached the same conclusion by a prudent process of careful data analysis. Objectively, the decision by the trustee was not imprudent but the process of reaching it was imprudent.

12 At other points during the hearing, senior counsel for ASIC submitted that ASIC’s case was not, or was not merely, a process case. It may be that ASIC presented its case in this alternative way because, as senior counsel recognised, imprudence merely in process would have required a “leap” to reach the conclusion that there was a risk of action by unitholders which was a pleaded basis for the breach (ts 724). Unitholders would be likely to bring an action only if there was a prospect of recovering compensation, which requires proof of causative loss. It is extremely unlikely that they would bring a costly civil action merely to expose defects in a process relating to a past decision that caused no loss. Hence, senior counsel for ASIC ultimately put ASIC’s case on the basis that the imprudence by LMIM was making the decision to approve the August 2012 Variation. In other words, ASIC’s allegation was imprudence in the outcome.

13 The difficulty with the submission about imprudence in outcome (ie imprudence in the decision taken) is that ASIC never explained what a prudent trustee in LMIM’s position would have done. ASIC constantly reiterated that LMIM should not have made a decision to approve the August 2012 Variation. But despite numerous requests for ASIC to explain what decision should have been made, ASIC did not present any such case.

14 There were two possible alternatives concerning what a prudent trustee in LMIM’s position should have done instead of approving the application to vary the limit of the loan. ASIC did not present a case on either basis. The first alternative was that the decision whether to approve the August 2012 Variation application, on the same or different terms, should have been deferred. The second alternative was that the August 2012 Variation application should have been refused.

15 An explanation of what a prudent trustee would have done required ASIC to examine whether a prudent trustee would have taken one of these alternatives. That required an assessment of the circumstances in which LMIM as trustee for the MPF found itself on 7 August 2012 when the MPF Credit Committee was asked to approve an extension of the loan limit of an additional $100 million. Those circumstances included the following:

(1) Maddison Estate already owed more than $150 million to LMIM as trustee for the MPF (the precise amount is very difficult to determine due to retrospective entries in the loan accounts arising from later transactions);

(2) the bank financing the loan, Suncorp-Metway Limited (Suncorp), had a prior security to LMIM, securing a debt of around $22 million;

(3) Suncorp wanted to exit its loan but LMIM had not been able to find a replacement funder;

(4) an “as is” valuation in July 2011 of the land acquired for the Maddison Estate development had assessed the value at between $35 million and $40 million, so a foreclosure by Suncorp would leave little, if any, of the $150 million or more for LMIM as trustee for the MPF;

(5) work had commenced on site, but until refinancing was obtained, the work could not continue in the absence of further funding from LMIM;

(6) Mr Fischer, the CFO of LMIM and one of ASIC’s key witnesses, had told others that the best prospect of recovery of the Maddison Estate loan was to find another funder to take out MPF’s position. The goal was for this to occur after completion of Stage 1 of the development which required further LMIM funds; and

(7) the use of the additional $100 million loan would only involve around $16.5 million of funds actually leaving the MPF, because the remainder was capitalised interest and other additions to the loan (including a loan re-establishment fee), which would increase the amount of the loan but would not involve any existing funds being spent.

16 ASIC mentioned very few of these circumstances. Instead, ASIC focused heavily upon matters such as: (i) the number of previous loans (none of which was alleged to involve a breach of duty); (ii) the absence of any explanation for why the additional increases in limit had not previously been foreseen; (iii) delays in the progress of the development; (iv) a hotly disputed report by Ernst & Young (which was not tendered for the truth of its contents); and (v) the LMIM process in relation to feasibility reports which supported the additional $100 million loan, including the lack of what was described by ASIC as an “independent feasibility report”.

17 A consideration of all of the relevant circumstances in August 2012, on the limited evidence before the Court including the position in which LMIM found itself, suggests that if a prudent trustee had to make a decision either to approve the loan variation or to refuse it then approval would have been given.

18 The alternative of deferral is not as simple although, unfortunately, the details of this alternative were not explored in evidence or submissions. If ASIC had brought its case on the basis that the decision to grant the August 2012 Variation should have been deferred (for example, until an independent feasibility report was obtained or so that the proposal could be amended such as to reduce the limit of the loan), then it would need to have led evidence and made submissions concerning the nature of the deferral and the considerations relevant to that decision by a prudent trustee in LMIM’s position. Putting to one side ASIC’s failure to explain precisely what was meant by an “independent feasibility report”, what would the cost be for an independent feasibility report? How long would such a report take to produce? What were the risks to LMIM in the meantime, including the possibility of default under the loan from the first mortgagee? Could those risks have been managed pending the deferred decision? The answer to these questions would all inform an explanation of what a prudent trustee in LMIM’s position would have done. But none of these matters was explored. To the extent that it is possible to assess any of these options, I conclude that there are also significant reasons which might suggest that deferral might not have been a prudent option.

19 Apart from these factual obstacles to ASIC’s case of imprudence by LMIM as trustee, there was a significant legal obstacle. The legal obstacle was that the trust instrument had excluded the duty to act prudently. ASIC submitted that in Queensland, although not in any other State which has similar legislation upon which the Queensland legislation was modelled, this duty could not be excluded. I do not accept that submission. Further, the failure of ASIC to prove that any loss was caused by any act of imprudence is a further reason why ASIC’s claim based on breach of trust must be dismissed.

20 In broad terms, therefore, ASIC’s case in relation to the alleged breaches by all three respondents of directors’ duties of skill and diligence must be dismissed because (i) no breach of trust was proved, and (ii) no reasonable alternative open to LMIM or the directors was proved. Further, to the extent to which there was information before the Court to assess the alternative choices, ASIC failed to prove that a reasonable director of a company in LMIM’s circumstances, with the responsibilities of each respondent, would have refused to approve the August 2012 Variation.

21 Separately to the allegations of breach of s 180(1) of the Corporations Act, ASIC also made another allegation against Mr Drake. This allegation was that by causing or permitting the August 2012 Variation in a manner which caused LMIM to commit a breach of trust against the MPF, Mr Drake acted for an improper purpose, and to gain an advantage for himself and a different trust. The improper purpose and advantage was increasing the cash flow to a separate trust from which he withdrew funds to maintain an extravagant lifestyle.

22 This “improper purpose” allegation was also tied to ASIC’s allegation of breach of trust. The failure of the breach of trust claim means that the improper purpose case must also fail. In any event, however, ASIC failed to prove the improper purpose.

23 The application against each of the remaining three respondent directors of LMIM must be dismissed.

ASIC’S PLEADED CASE AGAINST THE REMAINING THREE RESPONDENT DIRECTORS

24 In one respect, ASIC’s case in relation to all breaches was consistent, although the premise of ASIC’s case might be doubted. ASIC consistently alleged that in order for each of the directors to be liable for breach of their duties to LMIM it was necessary for LMIM to have committed a breach of trust. In other words, and as I explain further below, in order for the directors to have breached s 180(1) of the Corporations Act, ASIC’s case was that it first needed to prove a breach of trust by LMIM as trustee.

ASIC’s pleaded case concerning s 180(1) of the Corporations Act

25 ASIC pleaded that the directors breached their duties under s 180(1) of the Corporations Act because they caused or permitted LMIM to commit a breach of trust, and exposed LMIM to a foreseeable risk of harm, namely civil proceedings by unitholders in the MPF. ASIC essentially pleaded that this foreseeable risk of harm was greater than that to which a director, exercising his or her powers and discharging duties with the required care and diligence, would have permitted.

26 As for that part of the s 180(1) plea that the directors “caused or permitted LMIM to commit a breach of trust”, ASIC’s case was that LMIM breached its duty to exercise the care, diligence, and skill that a prudent person engaged in the profession or business of acting as a trustee or investing money would exercise in managing the affairs of other persons. This duty was pleaded in two ways: (i) as a statutory duty under s 22(1)(a) of the Trusts Act 1973 (Qld) (Trusts Act), and (ii) as an equitable duty.

27 In some respects ASIC’s case was opaque. The matters which were not clear were (i) how LMIM breached its duties as trustee, and (ii) how each respondent breached his or her duties as director under s 180(1) of the Corporation Act. Each is addressed separately later in these reasons. It suffices to observe at this point that at times ASIC alleged that it was not required to prove how any breach had occurred.

28 As to LMIM’s alleged breach of its duties as trustee, ASIC pleaded:

(1) numerous circumstances that existed at the time of the August 2012 Variation ([147]-[151]);

(2) that in those circumstances, LMIM exposed the MPF to a foreseeable risk of capital loss by approving the August 2012 Variation ([153]); and

(3) that in those circumstances, the degree of risk to which the MPF was exposed was greater than the risk to which a trustee exercising its powers of investment with the degree of care, diligence and skill that a prudent person engaged in the business of acting as a trustee or investing money would permit the MPF to be exposed ([154]).

29 Separately from those circumstances, ASIC also pleaded that:

(4) a trustee exercising its powers of investment with the degree of care, diligence and skill that a prudent person engaged in the business of acting as a trustee or investing money would have obtained an independent feasibility analysis of the anticipated future cash flows from the Maddison Estate development ([152]).

30 Early in ASIC’s case, I asked questions about the nature of ASIC’s pleaded case. ASIC appeared to plead two cases concerning the alleged breach of trust by approving the August 2012 Variation. The first case was a process case. It was an allegation that, irrespective of whether the August 2012 Variation would have been approved by a prudent trustee, the breach consisted of the failure by LMIM to follow a prudent process in making its decision to approve the variation. The second case was an outcome case. It was an allegation that the approval itself was imprudent (ts 87).

31 After a short adjournment, senior counsel for ASIC explained that the two aspects of the alleged breach were “cumulative”, and that only a single breach of trust was alleged. The single breach of trust alleged was the act of approving the August 2012 Variation. ASIC’s case was that the failure to obtain an independent feasibility report was just one factor which contributed to the breach. So, even if an independent feasibility report might have concluded that approval was a reasonable option, the other circumstances were still such that approval should not have been given (ts 89-90).

32 Several points about ASIC’s pleading should be noted:

(1) ASIC did not plead any possible alternative course that a prudent trustee would have adopted other than not to approve the August 2012 Variation. ASIC did not allege that a prudent trustee would have deferred the decision, preferring to wait to obtain an independent feasibility report. Nor did ASIC plead that a prudent trustee would have refused to approve the August 2012 Variation. ASIC’s case was that a prudent trustee would not, in the circumstances, have made the decision to approve the August 2012 Variation but it refused to say which of the two possible alternatives a prudent trustee would have taken.

(2) A crucial circumstance relied upon by ASIC as a reason why a prudent trustee would not have approved the August 2012 Variation was LMIM’s failure to obtain an independent feasibility report (ts 647-648). The absence of the independent feasibility report was important to ASIC’s case because its absence was said to increase the foreseeable risk of capital loss.

(3) Although ASIC’s case was that a prudent trustee would not have approved the August 2012 Variation, ASIC did not deny that a variation to allow the same further $100 million loan would not have been made in any event. ASIC did not lead any evidence about what an independent feasibility report might have concluded. In other words, ASIC accepted that it was possible that an independent feasibility report might have concluded that a reasonable course would have been to grant a variation permitting the proposed variation.

33 In closing submissions, ASIC submitted as follows ([274]):

ASIC’s case on breach of trust is simply this. A prudent trustee in [the] circumstances would not have approved the advance. The approval of that advance breached the duty prescribed by s 22 of the Trusts Act and exposed the MPF to a foreseeable risk of capital loss, being the risk of default by the borrower if the estimated cash flows generated by the development did not eventuate.

ASIC’s pleaded case of Mr Drake’s improper purpose

34 ASIC pleaded its allegations of Mr Drake’s contravention of s 181(1) and s 181(2) of the Corporations Act as based upon a plea of improper purpose. That plea was expressed in ASIC’s statement of claim as follows ([167]):

in causing and/or permitting LMIM to approve the August 2012 Variation and agreeing to advance to Maddison Estate a further $100 million in a manner which caused LMIM to commit a breach of trust against MPF, [Mr Drake] exercised his powers and discharged his duties as a director and officer of LMIM for the purpose of maximising the cash flow available to LMA as trustee for the [LMA] Trust to fund the loans to [himself] (Improper Purpose).

35 This improper purpose is pleaded as amounting to a failure by Mr Drake to exercise his powers and discharge his duty as a director and officer of LMIM in good faith in the best interests of LMIM or for a proper purpose; and improper use by Mr Drake of his position as a director of LMIM to gain an advantage for himself and for the LMA Trust (defined below).

Relevant entities, persons, and relationships

Outline of the various entities

36 On 31 January 1997, LMIM was incorporated. Mr Drake was appointed as director of LMIM at the time of incorporation. In June 2006 and September 2006 respectively, Mr van der Hoven and Ms Mulder were also appointed as directors of LMIM.

37 Separate from LMIM was another company, called LM Administration Pty Ltd (LMA), which was the trustee for the LM Administration Trust (the LMA Trust) which was created on 30 June 2003.

38 LMA (as trustee for the LMA Trust) and LMIM entered into a service agreement (LMA Service Agreement). The service agreement was provided in Sch 1 to be effective from 1 July 2005 although, curiously, the cover page bore the date 1 July 2010. In the LMA Service Agreement, LMA agreed to provide LMIM with services for LMIM’s funds management operations. Those services included the provision of staff, equipment, and other services for the proper management and administration of LMIM’s business including matters such as payment of operating costs, debt collection, preparation of financial statements, and contract negotiation. The cost for the services was agreed to be (i) a percentage of LMA’s total expenses, and (ii) all management fees earned by LMIM as the manager of its managed investment schemes.

39 The personnel who assisted LMIM (but were employed by LMA not LMIM) were organised into teams. There was a lack of clarity in some of the evidence and submissions concerning who employed these various personnel. I accept the evidence of Mr Fischer and Ms Mulder that employees were employed by LMA and not by LMIM (see also the LMA Service Agreement which I discuss below). Further, ASIC’s statement of claim, in paragraph [10], alleged that LMA employed Mr Drake, Ms Mulder, Mr van der Hoven, Mr Tickner, Ms Darcy, Mr Barnett, Mr Fischer, Mr King, and Ms Chalmers.

40 One of the teams which assisted LMIM was the Property Asset Management (PAM) team which contained employees of a related company, LMA. The PAM team was led by Mr Tickner. Another team was the finance team led by Ms Darcy and then Mr Fischer. A third was the marketing team led by Ms Mulder. A fourth was the global operations team led by Ms Phillips. A fourth was the portfolio management team led by Mr van der Hoven and Mr Petrik. A fifth was the foreign exchange team led by Mr van der Hoven. And a sixth was the in-house legal team.

41 The PAM team had around 25 staff. Their skills included areas of lending, development, town planning and general property. The team was divided into three parts responsible for: (i) identifying investment opportunities for the funds; (ii) assessing the assets and working to progress the projects; and (iii) administering the loans. The PAM team reported to the various committees, including the MPF Credit Committee (discussed further below). In 2012, when Mr Tickner retired as a director, Mr Fischer became the leader of the PAM team.

42 On 4 December 2001, LMIM entered a deed which produced a constitution for the MPF. The MPF Constitution was expressed as a deed between LMIM and the members, as they were constituted from time to time, of the MPF. The MPF was described as the “Scheme”. It was a unit trust to which members could subscribe by application following an offer or invitation to subscribe. The MPF Constitution was amended on a number of occasions after 4 December 2001.

43 On 4 May 2007, the MPF entered into a loan agreement granting a loan to Mr Drake. Although the loan agreement document was not in evidence at trial, its existence can be inferred from a variation deed that was in evidence. Mr Drake immediately drew down $8 million of the loan. By 30 June 2011, he had drawn down more than $15 million ($15,226,498.65).

44 On 14 September 2007, LMIM Asset Management Pty Ltd was incorporated. Mr Drake was its sole director, secretary and shareholder.

45 On 14 September 2007, Maddison Estate was incorporated. It was then known as LM Coomera Pty Ltd.

46 The MPF was only open to investment by wholesale or sophisticated investors. As Mr van der Hoven explained, the MPF funds were only sold to investors via a network of financial advisers. LMIM conducted “Introducer Days” in Australia and overseas at which presentations would be given by directors and other LMIM staff.

47 It is important to reiterate the point I made in the introduction to these reasons that the sophisticated investors and their advisers would have been immediately aware from the few pages of the information memorandum and investment application that investment in the MPF involved considerable risk. Returns, however, were high. They were around 25% per annum. As an example, the 1 November 2011 MPF information memorandum and application form for investors contained six pages of information entitled “About the LM Managed Performance Fund” and “LM Managed Performance Fund”. Those pages explained that the MPF invested in “commercial loans, direct real property, and cash” and had around $274 million of assets. Those $274 million of assets included around $248 million invested in Australian commercial loans. The largest of the commercial loans was described as being $142 million, more than half of the size of the fund.

48 The MPF investment decisions were made by an LMIM committee called the MPF Credit Committee.

49 Mr Drake, Ms Mulder, and Mr van der Hoven were all members of the committee. Ms Darcy was the chair until her resignation from LMIM on 21 June 2012. Other persons who were members of the credit committee included Ms McCallum (a member of the PAM team who served as a loans analyst) and Mr Parker (who was responsible for obtaining loans). Paralegal staff from the PAM team, Ms Chalmers and Ms Kingston, would organise and facilitate the meetings, and would take minutes. Development managers would also attend the committee meetings from time to time.

50 The role of the MPF Credit Committee was to assess loans proposed as investments for the MPF and to consider any required action for existing loans. The procedure involved preparation of a synopsis paper which was circulated to the committee members at the meeting. The meeting papers generally also included a feasibility model prepared by the development manager from the PAM team. The MPF Credit Committee would review the information and if a decision could not be made, the meeting was adjourned.

51 There were documentary guidelines and procedures for the MPF Credit Committee. One guideline was that “LM Directors require that all [MPF Credit Committee] decisions are to be made at a meeting as opposed to email voting (unless the topic for decision is a very simple, non-material matter)”. However, occasionally a decision would need to be made without a physical meeting and members would vote electronically through their email response.

52 In an information memorandum and application dated 1 November 2011, Mr Drake’s position and responsibilities were described as follows:

Peter Drake

Chairman and Chief Executive Officer

Peter founded LM in 1998, after 20 years’ experience in Australia’s financial services and life insurance sectors. As 100 per cent shareholder and CEO, Peter is principally responsible for the strategic vision, direction and structured growth of LM. Since its inception, Peter has been actively involved with LM’s expansion to ten international offices, now servicing beyond 60 countries. Peter is particularly active in the design and marketing of LM’s Australian dollar and currency hedged investment products. Working closely with LM’s Portfolio Manager to manage the growth of funds under management, Peter also plays an integral role in LM’s Funds Management Committee. With significant experience in direct property and joint venture property developments across Australia, Peter is also a member of LM’s Credit/Investment Committee, responsible for approving and setting the conditions of loans within LM’s mortgage portfolio. Peter’s vision of an innovative and prudential funds manager holds true as LM continues its dynamic growth in Australia’s financial services, business and property sectors. Peter is a member of LM’s Credit/Investment Committee, Funds Management Committee and Property Research and Analysis Committee.

A similar biography was provided in other information memoranda produced by LMIM from 2009 to 2012.

53 Mr Drake can comfortably be described as the prime mover behind the Maddison Estate development. The extent of his control is plain from the diagrammatic relationship of all of the relevant entities, set out later in these reasons. But his involvement was far more comprehensive than these formal roles. As I explain below, the Maddison Estate development became closely associated with his conception and vision for it, including as Mr Barnett described, Mr Drake’s desire to have a development which was different from anywhere else in the world.

54 In the same information memorandum and application described above in relation to Mr Drake, Mr van der Hoven’s position and responsibilities were described as follows:

Eghard Van Der Hoven

Executive Director, Portfolio Manager

In 2003 Eghard joined LM as Portfolio Manager, responsible for the monitoring and ongoing performance of LM’s various funds. As Executive Director, Eghard’s sound understanding of the investment industry spanning almost 20 years includes extensive experience in stock broking, auditing, investment analysis, business strategy and policy planning. As the Chair of LM’s Funds Management Committee, Eghard is responsible for joint decisions in relation to the asset allocation, geographic spread allocation, cash flow, delivery rate forecasting and budgeting of LM’s funds. He holds a Master of Commerce, majoring in Economics, and a Bachelor of Commerce (Hons) in Economics, from University of Pretoria, South Africa. Eghard is a member of LM’s Property Research and Analysis Committee, Credit/Investment Committee and Arrears Committee.

55 Mr van der Hoven commenced employment with LMA (the service provider to LMIM) in late 2003 as Portfolio Manager, and held this position until around 2009. As Mr van der Hoven explained, as Portfolio Manager he was primarily responsible for monitoring and managing the funds’ cash flows and measuring their profitability (which could determine the distribution rate that could be paid to investors). Mr van der Hoven was the Portfolio Manager of the MPF until Mr Petrik took over in about 2009. Despite this, Mr van der Hoven continued to be involved in the portfolio management process.

56 On 22 June 2006, Mr van der Hoven was appointed as Executive Director of LMIM. Also around this time, he was appointed as the head of LMIM’s Foreign Exchange team. His focus shifted to managing the foreign exchange activity of the various funds. He explained that his role as Executive Director did not change his core focus on portfolio management and foreign exchange management. However, he consequently became more involved in other parts of the business.

57 As an Executive Director, Mr van der Hoven sat on the board of directors and reported to the board on foreign exchange dealing, and was involved in making company decisions that were brought to the attention of the board. Mr van der Hoven was a voting member of the MPF Credit Committee and other committees including the Property Research and Analysis Committee.

58 Mr van der Hoven was paid a salary and bonuses. His bonus was calculated as 2.5% of the profit of the LM Group. Mr Fischer explained that the bonus was paid from the operating cash flow of the LM Group. ASIC submitted, without dispute, that his salary and bonuses (relevant to the business judgment rule upon which he relied) were as follows, with his salary apparently calculated by subtracting his bonus from total taxable income:

(1) 2010: salary $209,460; bonus $95,574;

(2) 2011: salary $244,066; bonus $129,811; and

(3) 2012: salary $244,047; bonus $236,786.

59 Mr van der Hoven gave evidence. He was cross-examined vigorously, although fairly. He was measured in his evidence and I consider that he was entirely truthful and, to the extent to which he could recall detail, reliable.

60 ASIC submitted that parts of Mr van der Hoven’s evidence had been contrived after he observed Ms Mulder give evidence before him. In particular, it was submitted that Mr van der Hoven’s affidavit evidence had referred only to auditors assessing the Maddison Estate development’s feasibility generally. In cross-examination, Mr van der Hoven’s evidence about his belief concerning the auditors became more precise. He said that he believed that the auditors were reviewing escalation rates (ts 683). ASIC submitted that this precision came only after he had heard similar questions asked in cross-examination of Ms Mulder.

61 Mr van der Hoven was a respondent to very serious allegations. He was present for much of the court hearing, which was entirely appropriate and to be expected given the gravity of the allegations against him. He could not possibly be criticised for observing Ms Mulder give evidence. I do not understand ASIC’s submission to have suggested this. However, ASIC’s submission misconstrues Mr van der Hoven’s increased precision in his answers as a basis upon which it could be said that his evidence had been moulded following his observations of Ms Mulder’s questions. I do not accept this submission about a witness who presented as honest and measured. As I explain later in these reasons, there is also an independent basis to accept Mr van der Hoven’s evidence concerning his belief in the role of the auditors.

62 In the 1 November 2011 information memorandum and application, Ms Mulder’s position and responsibilities were described as follows:

Francene Mulder

Executive Director, General Manager Distribution/Product

Francene commenced with LM in 1999, following a 20 year career in the commercial, legal and securities sectors. Prior to joining LM, Francene held managerial positions focused on the areas of commercial mortgages, conveyancing and the property sector. Specific experience in mortgage securities and the marketing of financial products provided a solid background for Francene to successfully undertake her role within LM. As Executive Director, Francene is primarily responsible for the marketing and expansion of distribution of LM’s products on a wholesale and retail basis, throughout Australia and international markets. Francene takes an active role in the direction of all client communication, company communication, corporate literature and service. Francene is also a member of LM’s Property Research and Analysis Committee, Funds Management Committee, Credit/Investment Committee and Arrears Committee.

63 Ms Mulder explained that after secondary school, she commenced work at various law firms, primarily in conveyancing and then general mortgages. In August 1999 she commenced working as marketing manager at LMIM within a small treasury division, although she was employed by LMA.

64 After having worked at LMIM for 7 years, Ms Mulder was appointed as Executive Director and Marketing Director of LMIM on 30 September 2006. Ms Mulder explained her duties as follows:

I was appointed Executive Director and Marketing Director of LMIM on 30 September 2006. As Marketing Director, I managed the marketing/business development teams, communications team, and the team that put the product disclosure statements together. After transitioning from Marketing Manager to Director I was still heavily involved in dealing with daily marketing activities. As such, though I was a member of various committees, I travelled frequently and often did not attend committee meetings. During this time, LMIM established further satellite offices and I was involved in assisting the teams with growing market presence in regions those offices were servicing.

…

In my role as Director, Marketing Manager and in publishing information intended for financial advisors relating to disclosure or particular assets of the fund, I was reliant on information reported to me by the finance team and the CFO. In a similar manner, I was reliant on information reported by the PAM Team in credit committee meetings in relation to fund assets… LM had processes and experienced senior people in place in each department and I was comfortable with that and relied on their expertise to assist me in making decisions as a Director and Marketing Manager. I discuss this in further detail below with respect to Maddison Estate.

I was an active working director. LM was a large organisation and my daily involvement was within the Marketing and Communications teams.

65 As Ms Mulder explained, her main focus from 2011 until the end of 2012 was the First Mortgage Income Fund. During this time, the other directors were working across the other areas of the business to allow Ms Mulder to focus on the First Mortgage Income Fund. Ms Mulder explained that she generally did not read valuations, loan documents, feasibility models or advices as that was not her area of expertise or her role. She said, and I accept that she believed, that it was the role of the expert individuals in the specialised in-house PAM team to understand these documents and to present the relevant information to decision-makers. She trusted their experience and expertise.

66 Like Mr van der Hoven, Ms Mulder was paid a salary and bonuses (calculated in the same way as Mr van der Hoven’s). ASIC submitted, without dispute, that her salary and bonuses (relevant to the business judgment rule upon which she relied) were as follows (again, apparently by calculating salary by deducting bonus from total taxable income):

(1) 2010: salary $178,620; bonus $104,142;

(2) 2011: salary $244,066; bonus $129,811; and

(3) 2012: salary $208,784; bonus $236,786.

67 Ms Mulder gave evidence. She was also cross-examined vigorously, although again fairly. ASIC submitted that an inference should be drawn that Ms Mulder was deliberately evading being committed on any matter of detail beyond what she relies upon for her defence. I do not accept this submission. I have no doubt at all that Ms Mulder was a thoroughly honest witness and that she answered all questions truthfully and to the best of her ability. Like Mr van der Hoven she had a limited recollection of matters that were discussed at MPF Credit Committee meetings. To the extent that she did recall those meetings, I consider that her answers were truthful and reliable.

The Maddison Estate joint venture

68 On 12 September 2007, the MPF Credit Committee considered a proposal for a $36.75 million loan by the MPF to a special purpose vehicle, LM Coomera JV Pty Ltd, for the Maddison Estate development. This was the genesis of the loan which was at the heart of the proceedings in this case.

69 A synopsis dated 11 September 2007 was sent to the MPF Credit Committee describing how LM Coomera JV Pty Ltd would on-lend funds to a company in the Young Land Group called Coomera Ridge Pty Ltd (Coomera Ridge) under joint venture agreements, or to another joint venture special purpose vehicle as part of the Young Land Group. Coomera Ridge had an entitlement to 31 parcels of land at Coomera, sometimes described as the “Pimpama Land”.

70 The 11 September 2007 synopsis explained that the proposal was for the MPF to enter a joint venture with a company owned by Mr Young (a director of the Young Land Corporation) to develop and sell the Pimpama Land into a residential subdivision comprising approximately 1532 residential lots (combining (i) some land sales, and (ii) some house and land packages). Mr van der Hoven explained that the expected gross revenue was said to be $577.8 million, and that the expected net profits to each joint venturer was said to be $65 million.

71 The security for the loan was described as “generally secured by way of second mortgage”, and a fixed and floating charge over all of the assets of the joint venture special purpose vehicle company.

72 On 13 and 14 September 2007, the members of the MPF Credit Committee approved the proposal for a loan of $36.75 million. The loan, which somehow became $40 million, was made from the MPF to a company which became known as Maddison Estate.

73 On 19 November 2007, several agreements gave effect to the joint venture:

(1) a joint venture development agreement was entered into by Maddison Estate and CRDC Pty Ltd (CRDC). CRDC was incorporated in September 2007 by Mr Young for the purpose of participating in a joint venture with Maddison Estate to develop the Pimpama Land. Mr Young was CRDC’s sole director and secretary until October 2010. The agreement provided for the equal sharing of proceeds and provision of $40 million by Maddison Estate. It was signed by Mr Drake for Maddison Estate and by Mr Young for CRDC. Curiously, it provided for a contribution from Maddison Estate of $40 million;

(2) a land availability agreement was entered into by Maddison Estate (signed by Mr Drake), Coomera Ridge, and CRDC (both signed by Mr Young); and

(3) a development management agreement was entered into by Maddison Estate, CRDC, and Young Land Project Management Pty Ltd (Young Land Project Management) to engage Young Land Project Management as the development manager.

74 As Mr Young had conceived it, the Maddison Estate development was for: (i) initial sales of land only; (ii) subsequent sales of house and land packages; and (iii) eventual sales of town houses and units. The plan involved approximately 1,458 dwellings on 700 residential lots with another 700 attached dwellings. This plan had obtained preliminary development approval from the Gold Coast City Council on 16 November 2009. It received final approval on 6 May 2010.

75 However, by 2010, the property market on the Gold Coast and other parts of Queensland had declined, in part due to the global financial crisis. Mr Young’s companies, including Young Land Project Management, were unable to meet their liabilities. Mr Young became personally bankrupt. Mr Young and Mr Drake agreed that Maddison Estate and CRDC would terminate the joint venture. Around April 2010, a number of agreements were entered to terminate the joint venture.

76 around the time of the termination of the joint venture:

(1) Maddison Estate entered into a development management agreement with LMA (LMA Development Management Agreement). LMA agreed to provide development services, effectively replacing Young Land Project Management. Mr Young, Mr Fischer and other former employees of Young Land Project Management were employed by LMA. Under the LMA Development Management Agreement, LMA would receive a monthly development management fee which commenced at $250,000 (plus GST) a month, and increased to $300,000 (plus GST) a month from July 2011. The LMA Development Management Agreement provided that the agreement would terminate on 30 June 2015.

(2) Mr Young transferred his interest in the Maddison Estate development to Mr Drake, and Mr Drake became the sole director of Coomera Ridge.

77 Also following termination of the joint venture, Maddison Estate was substituted as the sole borrower under the Suncorp loan facility (explained further below).

78 Some of these matters, and the relationships between the relevant entities, are represented in the diagram below.

The loans to the joint venture

The Suncorp loan in January 2008

79 In January 2008, Suncorp extended a finance facility to Maddison Estate and CRDC with a limit of $6,464,000. The facility was secured in part by first ranking charges over the assets and undertakings of Maddison Estate and CRDC.

80 On 23 January 2008, $5,836,377.50 was drawn down under the Suncorp loan facility. The loan facility was subsequently increased. By October 2011 the loan was drawn down to around $34 million. However, by March 2012 it had been reduced to $26 million.

81 Young Land Corporation and Suncorp commissioned valuations of the Pimpama Land on an “as is” basis. The valuations by Landmark White were dated 6 March 2008 and 28 July 2008 respectively. The valuations valued the Pimpama Land at around $54 million in March 2008, and $72.5 million in July 2008. The 28 July 2008 valuation noted that the total area of the 32 parcels of land was 109 hectares. It observed that at the date of valuation all of the properties were being used as rural homesteads and that a number of the lots had limited development potential due to town planning restrictions.

The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement on 13 November 2007

82 On 13 November 2007, LMIM as trustee for the MPF entered a loan agreement with Maddison Estate (the Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement). In that agreement, LMIM agreed to lend $40 million to Maddison Estate to give effect to the joint venture.

83 The date for repayment was the date when LMIM demanded payment from Maddison Estate. The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement did not provide for any guarantor. It provided that Maddison Estate would indemnify LMIM against any expense, loss, loss of profit, damage or liability which LMIM may suffer as a consequence of any default by Maddison Estate.

84 The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement provided for an interest rate to be determined by LMIM on the basis that Maddison Estate should have no distributable income at the end of each financial year. Interest instalments were to be paid monthly. The interest rate provision (Item 6) provided:

Such rate as is determined by [LMIM] in its absolute discretion from time to time (with the intent that such rate results in [Maddison Estate] having no distributable income at the end of each financial year), or in default of such determination by the Lender, 18% per annum.

85 The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement was executed by Mr Drake and Ms Darcy as directors of LMIM. It was executed also by Mr Drake as the sole director of Maddison Estate.

86 One of the recitals provided that LMIM entered into the agreement only in its capacity as trustee for the MPF.

87 The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement did not initially provide for any security. Security was subsequently provided under a deed of variation on 11 November 2008 where Maddison Estate agreed to provide a charge over “all the property, assets and undertaking of [Maddison Estate] of whatsoever nature and kind and wheresoever situated, present and future”.

88 On 20 May 2010, the interest rate was varied to be a “rate of 25% per annum, provided that such rate may be adjusted in the absolute discretion of the Lender on each anniversary of the loan, to equal the market rate for loans of such nature, to be determined by the Lender in its absolute discretion. If no adjustment is made the rate will remain at 25%”. The interest rate was set at 25% to ensure that Maddison Estate did not make a profit. Legal advice was received about the propriety of the interest rate increase in light of Mr Drake’s potential conflict of interest.

The variations to the Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement and the feasibility reports

89 The Maddison Estate loan limit could not have been intended to cover all of the costs of the Maddison Estate development and capitalised interest. There was little evidence on this point. ASIC asserted that the variations to the limit showed that LMIM’s “track record of properly forecasting development and other costs and adhering to budgeted projections was abysmal”. In contrast, Ms Mulder and Mr van der Hoven submitted that there was no evidence that the loan and variations were required to be a “once only loan”.

90 The evidence does not reveal whether the MPF Credit Committee ever considered the extent to which the initial limit and subsequent variations would need to be increased again in the future. Any conclusion about what maximum limit would be needed might have been extremely difficult to reach. One reason for the uncertainty is that the scope and detail of the project changed as it progressed and it seems that these changes were welcomed. Another reason for the uncertainty is that the limit of the loan would depend on how long the development took, which would be extremely difficult to estimate. The longer that the development took, the more capitalised interest would add to the loan amount. At 25%, the capitalised interest only on a $60 million loan would require $15 million per annum. A third reason for uncertainty is that LMIM’s exit plan, at least from late 2011, was to be bought out. This could only occur when a purchaser could be found to whom the debt could be assigned. When that occurred, no further limit would be needed by LMIM.

91 There are strong reasons why the initial limit, and variations, might reasonably not have been expected to be the permanent limit to the loan. It is notable that the independent lender, Suncorp, was prepared to lend with an initial limit of $6.4 million in January 2008 but to allow that limit to increase to around $34 million by October 2011.

92 One reason why the initial loan, and subsequent variations might not have been expected to be permanent is that the synopsis dated 17 September 2008, which supported an increase of the loan from $40 million to $58 million, described the purpose of the loan to be to “acquire 32 parcels of land, consolidate and re-develop into a residential Master Planned community comprising approx 1500 dwellings”. The synopsis explained that the “total purchase price of the land lots is $73M + fees + stamp duty + interest”. Even with the Suncorp loan, the first extension to $58 million would barely cover the costs associated with acquiring all 32 parcels of land, still less the costs of the massive development until revenue streams began. The synopsis also observed that the initial $40 million loan did not apply to ongoing costs, and that the increase to $58 million was necessary “to allow for ongoing budgeted payments” (emphasis added).

93 The inference that at least some of the limits which were varied by subsequent variations were not expected to be permanent is also supported by the fact that some of the variations were expressed as applying only for a particular period. For instance, the September 2011 variation was agreed on the basis that it would only provide the funding required until the end of March 2012. There was no evidence that any of the members of the MPF Credit Committee considered it surprising at that time that the additional $65 million limit was needed although it would only provide short term funding for six months (to the end of March 2012) up to a limit of $180 million. At least in relation to this variation, rather than suggesting an “abysmal” track record of forecasting as ASIC had submitted, the MPF Credit Committee was potentially quite accurate. By the end of March 2012, the loan balance of the Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement was $177,766,781.23 (to the extent that the loan balance can be relied upon despite retrospective additions to it based on later events).

94 The Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement was varied on the following occasions:

(1) An increase from $40 million to $58 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 18 September 2008) by a deed of variation entered on 11 November 2008. The variation took effect on 18 September 2008.

(2) An increase from $58 million to $70 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 5 August 2009) by a deed of variation entered on 6 October 2009. The variation took effect on 30 July 2009.

(3) An increase from $70 million to $95 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 25 February 2010) with a deed of variation executed on 14 April 2010. The variation took effect from 11 December 2009.

(4) An increase from $95 million to $115 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 28 July 2010) with a deed of variation executed on 28 June 2011. The variation took effect on 14 February 2011.

(5) An increase from $115 million to $180 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 25 September 2011) with a deed of variation executed on 19 October 2011. The variation took effect on 15 February 2011.

(6) An increase from $180 million to $280 million (with MPF Credit Committee approval on 7 August 2012) with a deed of variation executed on 1 July 2012 (the August 2012 Variation). The variation took effect on 30 June 2012.

95 Prior to each variation of the loan, feasibility reports were prepared and used to provide a synopsis for the MPF Credit Committee.

96 The feasibility reports were prepared by the PAM team using a proprietary software program called “Estate Master”. Estate Master required the input of numerous variables from which it calculated a net present value of the development. The variables which were inputted by members of the PAM team included projected revenue data, projected expense data and various assumptions such as escalation rates (the rates by which the value of lots might escalate in price during the timeframe of the development).

97 Ms Phillips explained that the revenue and expense inputs were not all externally obtained. Some, such as sales prices and valuations, were researched from independent reports and other research such as market sales prices, real estate agents, and sales reports. Those valuations were scrutinised by the board of LMIM in informal meetings.

98 Other inputs were externally obtained. Mr Barnett gave evidence that information was derived from external consultants concerning council fees, consultants’ fees and construction cost estimates from engineers and landscape architects. Mr Young also said in his affidavit and in his oral evidence that he obtained estimates of development costs from companies such as Mortons Urban Solutions (ts 413).

99 Mr King explained that apart from these cost and revenue inputs, the escalation rate was the remaining variable (although discount rates also needed to be applied to the model). As Mr Barnett explained, the escalation rates are an increment by which the value of the property is multiplied to estimate the amount by which the value of the property will improve over time. The increment is applied annually to estimate the amount by which property will increase in value from year to year. The values of property to be released through Stage 1 were the baseline. The escalation rates were applied to that baseline.

100 Mr Barnett said that it was usual to obtain the escalation rates from an independent property analyst. He and Mr King used a report from BIS Shrapnel entitled “The Outlook for Residential Land in Gold Coast”. Mr Barnett also subsequently referred to sales revenue escalation rates from a third party property consultant called RP Data.

The abandonment of the allegations concerning the September 2011 loan variation

101 From the inception of the case until shortly after ASIC’s evidence concluded, ASIC alleged breaches by the respondents in relation to the September 2011 loan variation. Although the allegations were abandoned, it is necessary to explain the background to that variation in a little more detail because ASIC continued to rely on that background in a slightly opaque submission that, although the variation was not said to be a breach of duty, it could somehow cast a shadow over the August 2012 Variation which was said to be a breach of duty.

102 By 18 September 2011, the loan balance of the Maddison Estate loan was around $140 million. This exceeded the previously approved limit of $115 million. A synopsis dated 22 September 2011 sought an increase to $200 million. The members of the MPF Credit Committee discussed, and approved, an increase in the limit of the advance from $115 million to $180 million a few days later.

103 On 25 September 2011, Mr Tickner sent an email to the members of the MPF Credit Committee (including the respondents) which attached the 22 September 2011 synopsis. The email said:

Attached is the synopsis regarding the increase to the maximum Approved Loan Amount.

This was discussed by ST LD PD EVH and FM and agreed to an amount of $180M based upon the funding required until end March 2012 on the basis of anticipated project related costs, Suncorp’s amortisation requirements interest and also MPF’s interest.

Can you please confirm your acceptance by voting.

104 The initials refer to, respectively, Mr Tickner, Ms Darcy, Mr Drake, Mr van der Hoven, and Ms Mulder. However, Ms Mulder’s evidence was that this loan was approved at a meeting when she was in Hong Kong, and too unwell to attend the meeting. I accept Ms Mulder’s evidence. In any event, Ms Mulder would have become aware of the approval shortly afterwards.

105 In the synopsis which was provided to the MPF Credit Committee to assist them in considering the variation to the loan, it was observed that the loan balance was more than $140 million (which exceeded the approved limit of $115 million). The synopsis noted that development approval had been granted and further applications were being made for the first stage of subdivision, although the number of proposed dwellings and lots would be subject to further feasibility and cash flow analysis once the approvals progressed. It was also noted that Suncorp held a first mortgage which secured a $38 million debt. It was observed that Suncorp was not continuing with development loans, was reducing all of its facilities, and had requested a paydown of the loan facility of $2 million a month for the six months which commenced in August 2011. The increase in the loan would “cover the principal reductions ($2M per month) and interest on the Suncorp loan (approx $350K p/m), interest on the MPF facility (currently $2.5M p/m and capitalising) and development costs for Stage 1 completion”.

106 ASIC’s claim initially alleged that the September 2011 loan variation was a breach of trust by LMIM, and a breach of s 180(1) of the Corporations Act by the directors. But, after the evidence of Mr Woolley, ASIC abandoned this allegation. Nevertheless, ASIC’s pleading and submissions still relied upon circumstances surrounding the September 2011 variation which had previously been pleaded in the context of the allegations of breach of trust, in particular:

(1) the respondents’ possession of a report produced by Ernst & Young in January 2011 which was critical of the development;

(2) the respondents’ knowledge of the Landmark White preliminary valuation for Suncorp in July 2011 which assessed the “as is” value of the Pimpama Land as between $35 million and $40 million based on its “highest and best use”;

(3) LMIM’s previous increases in the loan from $40 million in November 2007; and

(4) the respondents’ awareness that construction on the development had yet to commence.

107 ASIC was right to abandon the allegations of breach in relation to the September 2011 loan variation. But it continued to rely upon these circumstances in relation to the August 2012 Variation. I do not consider that they cast any great shadow upon the decision to approve the August 2012 Variation. In particular: (i) the Ernst & Young report was not relied upon for the truth of its contents, which were hotly disputed by the respondents at the time and subsequently; (ii) the Landmark White preliminary valuation was on an “as is” basis but the land was not intended to be sold “as is”; (iii) the previous increases in the loan – which were not said to be any unreasonable breach of duty – show, at best, that the development had proceeded more slowly than expected because, as ASIC submitted, “a major portion of each of the previous loan increases, since November 2007, was also the result of capitalising interest”; and (iv) as I explain later, although construction had not commenced in September 2011 there were dramatic changes to the project between September 2011 and August 2012 and it had begun to move apace.

The parties to the August 2012 Variation

108 The variation in August 2012 was the final variation. It increased the loan to $280 million. It was executed by Maddison Estate (as borrower), The Trust Company (PTAL) Ltd (The Trust Company) (as lender), and Coomera Ridge (as mortgagor). It was not executed by LMIM. The reasons for that are as follows.

109 On 4 February 1999 a custody agreement was entered into between LMIM and The Trust Company (then named Permanent Trustee Australia Ltd) (Custody Agreement). The Custody Agreement was amended numerous times after 1999, but relevantly it was amended on 1 November 2011 to include the assets of the MPF.

110 The 1 November 2011 amending deed to the Custody Agreement was between LMIM and The Trust Company. It provided in Recital E that LMIM and The Trust Company agreed to amend the Custody Agreement to appoint The Trust Company as custodian of the MPF. It was common ground that this was a legal assignment of LMIM’s legal interest as lender in its position as trustee for the MPF. The Custody Agreement obliged The Trust Company to hold the assets of LMIM, clearly identified by reference to the relevant Scheme, separately from The Trust Company’s assets (cl 4.9). The Trust Company was also authorised to act (cl 5.2):

on Instructions in writing which bear or purport to bear the signature or a facsimile of the signature of any of the Client’s Authorised Persons or Instructions provided by electronic means using the security codes or procedures agreed between Permanent and the Client.

111 Since the Custody Agreement vested the assets of the MPF in The Trust Company on 1 November 2011, the final deed of variation of the Maddison Estate MPF Loan Agreement was executed by The Trust Company as lender. All other previous deeds of variation had been executed by LMIM as lender.

112 The final deed of variation was signed by Mr Franklin for The Trust Company (“Manager Property Infrastructure and Custody Services”) and by Mr Drake for Maddison Estate and Coomera Ridge, with the word “Sole” handwritten in parentheses after the word “Director” below his signature.

113 Although the deed of variation was prepared by the property department of LMIM (ts 347) after the MPF Credit Committee meeting on 7 August 2012, LMIM was not a party to the deed. It may have been intended that LMIM should be a party because of the provisions of cl 15 which refer to LMIM’s obligations under this deed. For instance, cl 15.1 provided that: