FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fair Work Ombudsman v Yogurberry World Square Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1290

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT DECLARES:

1. The First Respondent, Yogurberry World Square Pty Ltd, contravened the following civil remedy provisions:

(a) section 45 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”), by failing to classify Mr M Kim, Ms Lee, Ms Cho, and Ms K Kim (together, the “Employees”) as prescribed by clause 16.1 of the Fast Food Industry Award 2010 (the “Fast Food Award”);

(b) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay Mr M Kim and Ms K Kim the minimum rates of pay as prescribed by clause 17 of the Fast Food Award;

(c) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay Ms Cho and Ms Lee the minimum junior rates of pay as prescribed by clause 18 of the Fast Food Award;

(d) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees casual loading as prescribed by clause 13.2 and sub-clause 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award;

(e) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees additional penalty amounts for work performed between 9.00pm and midnight on Monday to Friday as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(a)(i) of the Fast Food Award;

(f) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees Saturday penalty rates as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award;

(g) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees Sunday penalty rates as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(c)(ii) of the Fast Food Award;

(h) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of Mr M Kim, Ms Cho and Ms Lee public holiday penalty rates as prescribed by clause 30.3 of the Fast Food Award;

(i) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to engage each of the Employees for a minimum of three hours on all shifts as prescribed by clause 13.4 of the Fast Food Award;

(j) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees a special clothing allowance as prescribed by sub-clause 19.2(b)(ii) of the Fast Food Award;

(k) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make superannuation contributions on behalf of each of the Employees, as prescribed by clause 21.2 of the Fast Food Award;

(l) sub-section 323(1) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of Ms Cho, Ms Lee and Ms K Kim in full;

(m) sub-section 535(1) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make and keep records for Mr M Kim in the period from in or about July 2014 to 21 September 2014, as prescribed by the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Regulations);

(n) sub-section 535(2) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make and keep records for each of the Employees which included information prescribed by sub-regulations 3.32(d), 3.32(e), 3.32(f), 3.33(1)(a), 3.33(1)(b), 3.33(3), and 3.37(1) of the Fair Work Regulations; and

(o) sub-section 536(1) of the Fair Work Act by failing to provide pay slips to each of the Employees within one day of paying an amount to them in relation to the performance of work.

2. The Second Respondent, YBF Australia Pty Ltd, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, as set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above, in the period from in or about July 2014 to in or about December 2014.

3. The Third Respondent, CL Group Pty Ltd, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, as set out in Declarations 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(i), 1(j), 1(k), 1(l), 1(n) and 1(o) above, in the period from in or about January 2015 to 17 May 2015.

4. The Fourth Respondent, Ms Soon Ok Oh, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above, in the period from or about July 2014 to 17 May 2015.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, the Second and Third Respondents jointly, at their expense, are to engage a third party with qualifications in accounting or workplace relations to undertake an audit of compliance with the Fair Work Act and the Fast Food Award on the following terms:

(a) the audit period will be the period commencing on the date of this Order and ending six months after the date of this Order (the “Audit Period”);

(b) the audit is to be completed within two months of the date of this Order (“Audit Completion Date”);

(c) the audit will apply to all employees and persons otherwise engaged to perform work for any store in Australia trading under the “Yogurberry” brand and for which the Second and Third Respondents have responsibility as the master franchisor and payroll company respectively, at any time during the Audit Period (collectively, the “Yogurberry Employees”);

(d) according to each Yogurberry Employee's classification of work, category of employment and hours of work worked during the Audit Period, the audit will assess compliance with the following obligations:

(i) wages and work related entitlements under the Fast Food Award; and

(ii) record keeping and pay slip obligations in Division 3 of Part 3-6 of the Fair Work Act; and

(e) within 30 days of the Audit Completion Date, the Second and Third Respondents will jointly provide to the Applicant:

(i) a copy of the audit report which will include a statement of the methodology used in the audit; and

(ii) written details of any contraventions identified in the audit, the steps the Second and Third Respondents will take to rectify any identified contravention(s) and by when the rectification will occur.

2. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, the Second, Third and Fourth Respondents are to engage, at their own expense, a person or organisation with professional qualifications in workplace relations, to provide training to the Second to Fourth Respondents (and any other person holding the position of Director or Company Secretary of the Second and Third Respondents at the date of this Order):

(a) within three months of the date of this Order; and

(b) that covers obligations on employers under the Fast Food Award, the Fair Work Act and the Fair Work Regulations.

3. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, within 30 days of completing the training set out in Order 2 above, the Second, Third and Fourth Respondents are each to provide to the Applicant, in writing:

(a) the date on which the training was completed;

(b) the name of the person or organisation that conducted the training; and

(c) the details of the methods of delivery of the training and the content of the training.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT:

4. The First Respondent is to pay a penalty of $75,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its contraventions set out in Declaration 1 above.

5. The Second Respondent is to pay a penalty of $25,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j)and 1(k) above, in the period from in or about July 2014 to in or about December 2014;

6. The Third Respondent is to pay a penalty of $35,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(i), 1(j), 1(k), 1(l), 1(n) and 1(o) above, in the period from or about January 2015 to 17 May 2015; and

7. The Fourth Respondent is to pay a penalty of $11,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for her involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above in the period from in or about July 2014 to 17 May 2015.

8. Pursuant to sub-section 546(3)(a) of the Fair Work Act, each of the Respondents is to pay the respective penalty amount to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth.

9. Each of the Respondents is to pay the respective penalty amount within 28 days of these Orders.

10. The Respondents are to pay the costs of the Applicant.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 On 30 June 2016 there was filed in this Court an Originating Application and a Statement of Claim. The Applicant was the Fair Work Ombudsman. The four Respondents named in that proceeding were Yogurberry World Square Pty Ltd (“Yogurberry World Square”), YBF Australia Pty Ltd (“YBF Australia”), CL Group Pty Ltd (“CL Group”) and Ms Soon Ok Oh.

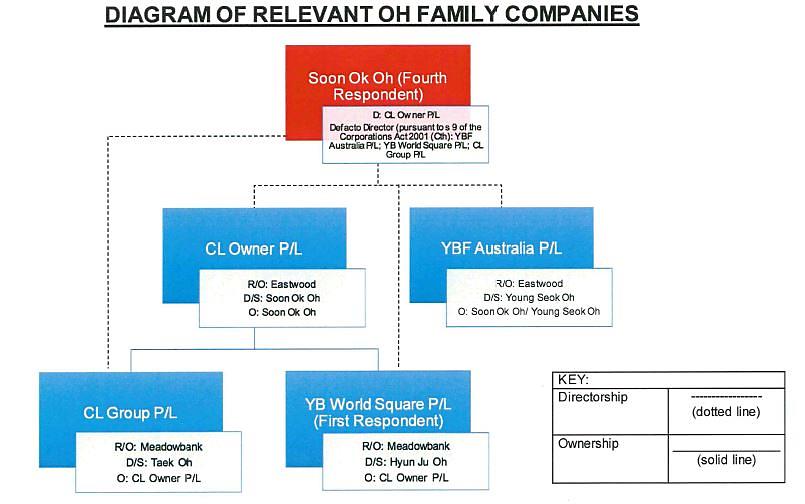

2 Each of the corporate Respondents was part of a group of family companies. All Respondents were involved in the operation of a business, trading under the Yogurberry brand name. The business sells take-away frozen yoghurt and drinks.

3 In very summary form, the proceeding brought by the Fair Work Ombudsman alleged that in respect of four former employees of Yogurberry World Square there had been:

contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”) involving failures under the Fast Food Industry Award 2010 (the “Fast Food Award”) to pay (inter alia) minimum rates of pay, casual loading and penalty rates;

contraventions of the Fair Work Act involving failure to pay wages in full by the making of unlawful deductions; and

contraventions of the Fair Work Act involving a failure to keep records and to issue pay slips as prescribed by the Fair Work Regulations 20009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Regulations”).

4 A Statement of Agreed Facts was filed on 18 August 2016.

5 Although Yogurberry World Square was the employer, all Respondents admit an involvement in the contraventions alleged. The relationship between the Respondents was helpfully summarised in the following diagram prepared by the Fair Work Ombudsman:

6 Other than the quantum of penalties to be imposed, all other relief has been agreed, including the declaratory relief which is sought and an order requiring the audit of YBF Australia and CL Group.

7 It is the quantification of the penalties to be imposed (and the manner in which those penalties are to be quantified) which presently divides the parties. And even that dispute narrowed down during the course of the hearing to a fairly confined issue. The appropriate quantification of penalties urged upon the Court in respect to each of the Respondents by the Fair Work Ombudsman (on the one hand) and the Respondents (on the other hand) may be summarised as follows:

Fair Work Ombudsman | Respondents | |

Yogurberry World Square | $67,702.50 – $96,390 | $40,000 – $50,000 |

YBF Australia | $22,950 – $32,130 | $12,500 – $15,000 |

CL Group | $33,851.25 – $48,195 | $15,000 – $20,000 |

Soon Ok Oh | $9,180 – $12,852 | $8,000 – $10,000 |

The general principles to be applied

8 There was agreement between the parties as to the general principles which guide the exercise of the discretionary power to impose penalties and the quantum of those penalties.

9 Given that agreement, there is no necessity to canvass the many authorities which outline the principles to be applied.

10 At the outset, it must nevertheless be recalled that there are broadly three purposes for imposing penalties for breaches of industrial law: punishment, deterrence and rehabilitation: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46, (2015) 90 ALJR 113 at 126 to 127 French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ there observed:

[53] Civil penalty proceedings are civil proceedings and therefore an adversarial contest in which the issues and scope of possible relief are largely framed and limited as the parties may choose, the standard of proof is upon the balance of probabilities and the respondent is denied most of the procedural protections of an accused in criminal proceedings.

[54] Granted, both kinds of proceeding are or may be instituted by an agent of the state in order to establish a contravention of the general law and in order to obtain the imposition of an appropriate penalty. But a criminal prosecution is aimed at securing, and may result in, a criminal conviction. By contrast, a civil penalty proceeding is precisely calculated to avoid the notion of criminality as such.

[55] No less importantly, whereas criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation, the purpose of a civil penalty, as French J explained in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd, is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance:

Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Trade Practices Act]. … The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

See also: Ponzio v B & P Caelli Constructions Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 65 at [93], (2007) 158 FCR 543 at 559 (approved in Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCAFC 59 at [68] to [69], (2015) 229 FCR 331 at 358 to 359); Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Upton [2015] FCA 672 at [9] per Gilmour J; Fair Work Ombudsman v South Jin Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 832 at [16] per White J.

11 The task of fixing the quantum of penalty, it has been repeatedly acknowledged, is a process of “instinctive synthesis”: Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8 at [26] to [28] and [54]; (2008) 165 FCR 560 at 567 to 568 and 572 per Graham J. Notwithstanding this “instinctive synthesis”, many decisions of this Court have attempted to give greater content to, or greater clarification of, the reasoning process to be followed by providing a list — albeit in a non-exhaustive manner — of those considerations which may assume relevance. In Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080 at [14]; (2007) 166 IR 14 at 18 to 19 Tracey J, for example, set forth one such list as follows:

the nature and extent of the conduct which led to the breaches;

the circumstances in which that conduct took place;

the nature and extent of any loss or damage sustained as a result of the breaches;

whether there had been similar previous conduct by the respondent;

whether the breaches were properly distinct or arose out of the one course of conduct;

the size of the business enterprise involved;

whether or not the breaches were deliberate;

whether senior management was involved in the breaches;

whether the party committing the breach had exhibited contrition;

whether the party committing the breach had taken corrective action;

whether the party committing the breach had co-operated with the enforcement authorities;

the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigation and enforcement of employee entitlements; and

the need for specific and general deterrence.

As his Honour has subsequently pointed out, “[e]ach of these considerations has the potential to have both an ameliorative and aggravating impact in the course of the instinctive synthesis”: Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (No 2) [2015] FCA 407 at [91]. See also: Australian Federation of Air Pilots v HNZ Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 755 at [28] per Mortimer J; Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Bragdon (No 2) [2015] FCA 998 at [12] per Flick J.

12 Although there was substantial agreement between the parties, there was some divergence between the parties as to the application to the facts of the following considerations, namely:

deterrence;

the fact that Ms Soon Ok Oh had limited English capabilities; and

the fact that those employees who had been underpaid were vulnerable individuals.

The issue of central relevance, however, which divided the parties at the end of the hearing focussed upon:

the manner in which the penalties should be quantified.

Each of these matters should briefly be addressed.

The contraventions involved

13 The Fair Work Ombudsman alleged 15 contraventions.

14 In respect to Yogurberry World Square, these contraventions were summarised in the following table which set out the nature and number of the contraventions alleged, the maximum penalty that could be imposed and the source of the power to impose the penalty as follows:

No. | Provisions contravened | Description of contravention | Max penalty (body corporate) | Max penalty (individual) | Reference for maximum penalty | Contraventions / employees |

1 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Classification Failure to classify Employees under Fast Food Award: cl 16.1 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

2 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Minimum wages Failure to pay minimum rates of pay: cl 17 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 2 employees |

3 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Junior wages Failure to pay junior rates of pay: cl 18 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 2 employees |

4 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Casual loading Failure to pay casual loading: cll 13.2 and 25.5(b) to the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

No. | Provisions contravened | Description of contravention | Max penalty (body corporate) | Max penalty (individual) | Reference for maximum penalty | Contraventions / employees |

5 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Evening penalty rates Failure to pay evening penalty rates for work between 9pm and midnight cl 25.5(a)(i) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

6 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Saturday penalty rates Failure to pay Saturday penalty rates: cl 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

7 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Sunday penalty rates Failure to pay Sunday penalty rates: cl 25.5(c)(ii) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

8 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Public holiday penalty rates Failure to pay public holiday penalty rates: cl 30.3 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

9 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Minimum shifts Failure to engage Employees for minimum of three hours per shift cl 13.4 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

10 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Special clothing allowance Failure to pay special clothing allowance for laundering uniforms cl 19.2(b)(ii) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

11 | FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Superannuation Failure to make superannuation contributions cl 21.2 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 2 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

12 | FW Act s 323(1) | Failure to pay in full Failure to pay in full (by making unlawful deductions) | $51,000 per breach | $10,200 per breach | FW Act Item 10 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 3 employees |

13 | FW Act s 535(1) | Record-keeping Failure to keep records prescribed by the FW Regulations | $25,500 per breach | $5,100 per breach | FW Act Item 29 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 1 employee |

14 | FW Act s 535(2) | Record-keeping Failure to keep records with information prescribed by regulations 3.32(d), 3.32(e), 3.32(f), 3.33(1), 3.33(3) and 3.37(1) of the FW Regulations | $25,500 per breach | $5,100 per breach | FW Act Item 29 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

15 | FW Act s 536(1) | Pay slips Failure to issue pay slips | $25,500 per breach | $5,100 per breach | FW Act Item 29 of subsection 539(2) | Multiple contraventions for 4 employees |

The table also identified s 539 of the Fair Work Act as the source of the power to impose a penalty.

15 Annexures to the submissions filed on behalf of the Fair Work Ombudsman again set forth in similar table format the manner of calculation of the penalties sought to be imposed in respect to each of the other Respondents – including the “discounts” that were considered appropriate by reason of the co-operation of the Respondents and an assessment as to whether the contraventions were considered to be in the “low range” or “low to mid-range” of seriousness.

16 Using the numbering set forth in the Table in respect to Yogurberry World Square, it was admitted that:

YBF Australia was only involved in Yogurberry World Square’s contraventions numbered 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and 11, and only in the period from July 2014 to December 2014;

CL Group was involved in all of Yogurberry World Square’s contraventions numbered 1 to 15, but only in the period from January 2015 to 17 May 2015; and

Ms Soon Ok Oh was only involved in Yogurberry World Square’s contraventions numbered 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and 11, for the entire contravention period from July 2014 to 17 May 2015.

It was also common ground that:

contraventions 2 and 3 were to be regarded as constituting a single “course of conduct”.

Deterrence – specific & general

17 The facts of the present case give rise to the need separately to consider both specific and general deterrence when quantifying the penalty to be imposed.

18 As a matter of general principle, it is well-recognised that a principal purpose of ordering the payment of a financial penalty is “to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act”: Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd (1991) ATPR 41–076 at 52,152; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761 at [75], (2011) 282 ALR 246 at 265 per Perram J; Global One Mobile Entertainment Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 134 at [125] per Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ; DP World Sydney Ltd v Maritime Union of Australia (No 2) [2014] FCA 596 at [18], (2014) 318 ALR 22 at 27 per Flick J; Minister for the Environment v Karstens [2015] FCA 649 at [23] per Jagot J. The quantification of an appropriate penalty, accordingly, focuses attention upon the conduct of the contravener and upon the public interest in deterring others from engaging in like conduct. A penalty, it has been said, “must be fixed at a level that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by a contravener and by others who might be tempted to follow suit”: Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCA 1213 at [24] per Tracey J. In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20, (2012) 287 ALR 249 at 265 Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ have stated:

[62] There may be room for debate as to the proper place of deterrence in the punishment of some kinds of offences, such as crimes of passion; but in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. The primary judge was right to proceed on the basis that the claims of deterrence in this case were so strong as to warrant a penalty that would upset any calculations of profitability. The purpose of Optus’s conduct was to generate sales, and hence, profits. The advertising deployed by Optus was calculated to win business from its rivals. The same share of business might not have been attracted by a more balanced presentation of the advantages of the plans. There is no reason to doubt that Optus knows its business sufficiently well that it is safe to proceed on the footing that its course of conduct in the campaign reflected informed calculation. While one cannot isolate the profits attributable to the campaign, it is necessary and desirable to impose a penalty which is apt to affect in a substantial way the profitability of Optus’s misconduct.

[63] Generally speaking, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention. The primary judge did not engage in a surgical exercise calculated to deprive Optus of the profits referable to the increase in business generated by the campaign. It cannot seriously be suggested that this Honour was concerned to engage in an exercise in “profit stripping”. To so describe his Honour’s approach is to distract from the legitimate claims of deterrence in a case like the present: (2012) 287 ALR at 265.

19 The facts of the present case which give rise to the need for deterrence may be traced back to at least September 2013. On 3 September 2013 the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman wrote to Mr Young Soek Oh, the husband of Ms Soon Ok Oh, a “Letter of Caution”. The “Background to Investigation” which was set forth in that letter referred to “investigations in relation to Yogurberry’s compliance with record keeping obligations as prescribed by the FW Act and Yogurberry’s compliance with meeting employee entitlements, including hourly rates of pay, accrual and payment of annual leave entitlements, as prescribed by the FW Act and Fast Industry Award 2010 [sic]”. That letter thereafter stated as follows:

Based on the information and evidence provided, the FWO has formed the view that Yogurberry has contravened the following Commonwealth workplace laws in relation to annual leave entitlements, making and keeping records and issuing pay slips to employees:

1. YBF Australia Pty Ltd has contravened NES section 90(2) of the FW Act by failing to pay employees identified in Point 11 above, annual leave entitlements (including annual leave loading) upon termination of their employment.

The total underpayments arising from this contravention were calculated to be $5,946.63.

On this basis YBF Australia Pty Ltd has also contravened section 44 of the FW Act by contravening a NES.

On Friday 9 August 2013, YBF Australia Pty Ltd rectified the contravention by way of payment of $5,946.63 to the identified employees.

2. YBF Australia Pty Ltd has contravened section 535(1) of the FW Act by failing to make and keep records of annual leave accrued, taken and/or paid to all current and former employees pursuant to Regulation 3.36 of the Fair Work Regulations.

On this basis, the FWO issued Infringement Notice No: 7050 for the Penalty Amount of $1,700.00. This was subsequently paid on Wednesday 28 August 2013.

3. YBF Australia Pty Ltd has contravened section 536(1) of the FW Act by failing to give each of its employees pay slips.

On this basis, the FWO issued Infringement Notice No: 7051 for the Penalty Amount of $850.00. This was subsequently paid on Wednesday 28 August 2013.

A “Formal Caution” was set forth in the letter, which concluded with a statement that in the event of further contraventions, “the fact that YBF Australia Pty Ltd has already been issued with a Letter of Caution will be a factor the FWO will take into account in deciding whether it is in the public interest to commence civil proceedings in respect of those further contraventions”.

20 Thereafter, on 13 February 2014 there was an exchange of e-mails between Mr Young Seok Oh and the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman again concerning amounts owing to employees. The e-mail from Mr Oh acknowledged that “we cannot provide the records of the work roster due to the change of management and the time elapsed, which is more than a year”. The response from the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman referred to the need to keep records for 7 years and the fact that the Fair Work Ombudsman regarded an hourly rate of pay of $12 for casual employees as “unacceptable” where the adult casual rate pursuant to the Fast Food Award was in excess of $20.

21 In about June 2015 the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman served a “Notice to Produce Records or Documents”. A response provided by the accountants for the Respondents stated (inter alia) that:

time records for specified periods were “missing due to the change of the internal accountant”;

wage payment records for specified periods were “missing due to the change of the internal accountant”; and

remittance advices verifying payments made to each employee were “N/A”.

Such records and documents which were otherwise provided were, to say the least, scant.

22 Other employee records as were produced to the Fair Work Ombudsman appeared to take the form of handwritten notations in an exercise book, with no detail provided as to such matters as the surname or the tax file number of the employee.

23 No further information was available in respect to either the employees the subject of the 2013 investigation or the employees who were underpaid in the present proceeding.

24 The inescapable inferences that are available on the limited available facts, and the inferences which should be drawn, are that the Respondents:

have since at least 2013 been on notice as to the need and importance of keeping proper records in respect to employees; and

have deliberately refrained from keeping such records.

It is a further inescapable inference that the reasons why the Respondents deliberately refrained from keeping records include:

the objective of frustrating any attempt on the part of the Fair Work Ombudsman to monitor the payment to employees of their lawful entitlements; and

the objective of gaining personal financial benefit by cloaking the quantum of payments made to employees from scrutiny.

Those inferences only assume greater importance by reason of the fact that:

the employees concerned were vulnerable employees, being persons who spoke little English or (at least) did not speak English as their first language, persons who were young and from overseas.

No reliance can be placed by the Respondents upon any assertion that they too had difficulties in communicating in English or by reason of their being from South Korea, in circumstances where:

the Fair Work Ombudsman repeatedly offered the Respondents translation facilities;

and where:

the failure to comply with the regulatory requirements, which had repeatedly been brought to their attention, stood in stark contrast to the detail of the corporate restructure that the Respondents carried out in 2013.

25 The need for specific deterrence in respect to the Respondents thus assumes considerable importance.

26 The need for general deterrence arises by reason of the fact that the employees concerned were employed in the “fast-food” industry, where:

employees are commonly employed on a casual basis;

and where:

employees are commonly vulnerable by reason of their age, limited education and limited English communication skills.

27 Albeit only one of the considerations to be taken into account in fixing the quantum of penalties, the relevance of both specific and general deterrence assumes some considerable importance on the facts of the present case. The importance of general deterrence includes the need to ensure that any penalty that may be imposed is not seen as “the cost of doing business”.

Co-operation

28 Again, as a matter of general principle, the co-operation of a respondent with a regulator is relevant to quantifying the penalty to be imposed for a contravention. But, as noted by Stone and Buchanan JJ in Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70, (2008) 168 FCR 383 at 405:

[76] … a discount should not be available simply because a respondent has spared the community the cost of a contested trial. Rather, the benefit of such a discount should be reserved for cases where it can be fairly said that an admission of liability: (a) has indicated an acceptance of wrongdoing and a suitable and credible expression of regret; and/or (b) has indicated a willingness to facilitate the course of justice.

29 The facts of the present case which give rise to the need to give specific attention to the relevance of the co-operation of the Respondents with the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman arises by reason of the fact that:

there has been filed an extensive Statement of Agreed Facts, which details the facts which give rise to the admitted contraventions of the Fair Work Act and the Regulations. Included within that Statement is agreement as to the form of relief recommended by the parties in respect to declaratory relief and agreement as to an audit of the corporate Respondents. The quantum of the penalties to be imposed, of course, is not the subject of agreement; and

no real detail has been provided as to the financial circumstances of the Respondents.

It is the latter fact which occasions concern.

30 There was, in particular, no agreed statement of fact – or other evidence – going to such matters as:

any Profit and Loss Statement for any of the Respondents for any period of time;

any income tax returns for any particular year for any of the Respondents disclosing taxable income;

any bank statement disclosing any account balances as were held by any of the Respondents.

Such searches as were undertaken by the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman nevertheless disclosed some assets, including realty, held by one or other of the Respondents.

31 Again, an inescapable inference available on the facts, and the inference which should be drawn, is that:

the Respondents own some personal property and realty.

More disturbing is the inescapable inference that:

the Respondents have deliberately not disclosed any information of relevance to their financial status;

and have done so for the purpose of:

withholding from scrutiny their true financial position, potentially including the extent to which their contraventions have improved their financial position.

32 On the facts of the present case, Counsel for the Respondents accepted that the proposed reduction made by the Fair Work Ombudsman of 25% by reason of the co-operation of the Respondents was in the right “ball park”. Counsel for the Respondents may have wished for a greater reduction; but the reduction as quantified by the Fair Work Ombudsman is appropriate.

33 Given the matters in respect to which the Respondents have withheld co-operation as to those matters touching upon their financial circumstances, it is respectfully considered that a reduction of 25% is appropriate; certainly no greater reduction should be made. Although the Respondents have accepted liability, the failure to provide co-operation in respect to their financial circumstances only reflects an unwillingness to co-operate in respect to the financial consequences flowing from that acceptance of liability.

34 The stated assumption throughout the case, and an assumption in respect to which Counsel for the Respondents was expressly asked to address if it were incorrect, was that whatever the penalty to be imposed on one or other of the Respondents would be jointly met. During the course of final submissions Counsel on behalf of the Respondents proffered an undertaking on behalf of Ms Soon Ok Oh to pay any penalty imposed upon the First or Third Respondents “within a year” of any penalty being imposed.

The Ombudsman’s manner of quantifying penalties

35 With reference to the facts of the present case, Counsel for the Fair Work Ombudsman in the body of his Outline of Submissions set forth a summary of the range of penalties sought in respect to each of the Four Respondents. Annexed to those submissions were a series of four annexures which set forth in greater detail the penalty sought in respect to each contravention and in respect to each Respondent.

36 Yogurberry World Square was involved in each contravention. The annexure in respect to that Respondent grouped the second and third contraventions together and then set forth the range within which a penalty was sought.

37 A similar format of annexure provided in respect to YBF Australia provided, by way of example, as follows:

Provisions contra-vened | Description of contravention | Max penalty | Discount proposed | Maximum after discount | Range of penalty sought | Total penalty sought | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay minimum rates of pay: cl 17 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay junior rates of pay: cl 18 of the Fast Food Award | ||||||||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay casual loading: cll 13.2 and 25.5(b) to the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay evening penalty rates for work between 9pm and midnight cl 25.5(a)(i) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 5-10% | $1,912.50 - $3,825 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay Saturday penalty rates: cl 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay Sunday penalty rates: cl 25.5(c)(ii) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay public holiday penalty rates: cl 30.3 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to pay special clothing allowance for laundering uniforms cl 19.2(b)(ii) of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 5-10% | $1,912.50 - $3,825 | |||||||||||

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modern Award) | Failure to make superannuation contributions cl 21.2 of the Fast Food Award | $51,000 | 25% | $38,250 | 15-20% | $5,737.50 - $7,650 | |||||||||||

Provisions contra-vened | Description of contravention | Max penalty | Discount proposed | Maximum after discount | Range of penalty sought | Total Penalty Sought | |||||||||||

TOTAL | $408,000 | $306,000 | $38,250 - $53,550 | ||||||||||||||

Further totality discount (40%) | $15,300 - $21,420 | ||||||||||||||||

TOTAL AFTER DISCOUNT | $408,000 | $306,000 | $22,950 - $32,130 | ||||||||||||||

A doubling up of moral responsibility & objective seriousness?

38 Two matters which varied in emphasis throughout the hearing, but which ultimately emerged as common ground, were:

the proposition that it was of central importance to ensure that any penalty imposed on one or other of the Respondents did not operate such as to impose a “double punishment” for the one contravention and that multiple contraventions may be regarded in some circumstances as a single “course of conduct”; and

any penalties imposed must be regarded in their “totality” to ensure that the penalties imposed were not disproportionate to the gravity of the contraventions.

Each of these propositions should be briefly explored – but it was the manner in which penalties were sought to be apportioned between each of the Respondents that ultimately divided the parties.

39 As a matter of general principle, Counsel for the Respondents was on sound ground in relying upon the following observations of Tracey J in Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCA 1213:

[19] Where, as in the present proceeding, multiple contraventions arise from a series of related events which constitute a course of conduct principles of proportionality and consistency come into play in determining the appropriateness of the penalty …

[20] The ultimate penalty “must be proportionate to the offence and in accordance with the prevailing standards of punishment” …

[21] Consistency requires that “[l]ike cases should be treated in like manner”: Wong v R (2001) 207 CLR 584 at 591 (Gleeson CJ). The consistency principle does not require a detailed factual comparison between past cases and that presently under consideration with a view to fixing a higher or lower penalty depending on the outcome of the comparative analysis …

[22] It is also necessary to ensure that a respondent is not punished twice for the same conduct. The principle was explained by the Full Court in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 269 ALR 1 at 12 as follows:

It [the “course of conduct” principle] is a concept which arises in the criminal context generally and one which may be relevant to the proper exercise of the sentencing discretion. The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factually specific enquiry. Bare identity of motive for commission of separate offences will seldom suffice to establish the same criminality in separate and distinct offending acts or omissions.

(original emphasis)

[23] This principle is to be applied separately from and anterior to the final check constituted by the application of the totality principle … It does not necessarily require the application of a single penalty for all of the contravening conduct …

40 Reference should also be made to s 557(1) of the Fair Work Act which provides as follows:

For the purposes of this Part, 2 or more contraventions of a civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (2) are, subject to subsection (3), taken to constitute a single contravention if:

(a) the contraventions are committed by the same person; and

(b) the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct by the person.

In Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39, (2010) 269 ALR 1 at 12 to 13 Middleton and Gordon JJ said of the principles relevant to whether conduct constitutes a “single course of conduct”:

[39] … a “course of conduct” or the “one transaction principle” is not a concept peculiar to the industrial context. It is a concept which arises in the criminal context generally and one which may be relevant to the proper exercise of the sentencing discretion. The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factually specific enquiry.

…

[41] … the principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, the court must ensure that the offender is not punished twice for the same conduct. In other words, where two offences arise as a result of the same or related conduct that is not a disentitling factor to the application of the single course of conduct principle but a reason why a court may have regard to that principle, as one of the applicable sentencing principles, to guide it in the exercise of the sentencing discretion …

[42] A court is not compelled to utilise the principle …

[Emphasis in original]

41 The “totality principle” was addressed as follows by Goldberg J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53:

The totality principle is designed to ensure that overall an appropriate sentence or penalty is appropriate and that the sum of the penalties imposed for several contraventions does not result in the total of the penalties exceeding what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct involved … But that does not mean that a court should commence by determining an overall penalty and then dividing it among the various contraventions. Rather the totality principle involves a final overall consideration of the sum of the penalties determined …

As Spender J pointed out in McDonald v R [(1994) 48 FCR 555 at 556]:

Implicit … is that the sentence for each offence should be “properly calculated” in relation to the offence for which it is imposed.

It is explicit in this statement that a sentencer or penalty fixer must, as an initial step, impose a penalty appropriate for each contravention and then as a check, at the end of the process, consider whether the aggregate is appropriate for the total contravening conduct involved …

In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL Sales Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1030 Middleton J likewise referred to the “totality principle” being a “final consideration” as follows:

[61] Lastly, I must consider the totality principle, parity and deterrence.

[62] With respect to the totality principle, it is trite law that the total penalty for related offences should not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved … Put another way, the totality principle involves a final consideration of the sum of the penalties determined …

See also: Maritime Union of Australia v Fair Work Ombudsman [2016] FCAFC 102 at [39] at per Tracey and Buchanan JJ.

42 Neither of these principles was put in issue by the Fair Work Ombudsman.

43 It was the manner of application of these principles to the quantification of penalties which was put in issue by Counsel for the Respondents. Of particular concern to the Respondents was to ensure that “the particular [Respondent’s] role in the contravention” should be borne in mind to “avoid inappropriately double counting matters that have been taken into account in relation to another Respondent”.

44 On the approach of the Respondents, each of the Tables prepared by the Fair Work Ombudsman in respect to each of the Respondents erred in:

setting forth the maximum penalty that could be imposed and in respect to that maximum a percentage to reflect the fact of co-operation; and

setting forth a range of penalty in respect to the maximum penalty as discounted.

To so approach the process of quantification, it was urged on behalf of the Respondents:

gave inappropriate prominence to the maximum penalty that was prescribed by the Legislature for each of the contraventions; and

gave too little prominence to the “objective seriousness” of the conduct which constituted the contravention.

The approach of the Fair Work Ombudsman, it was submitted on behalf of the Respondents, failed to properly take into account the “moral responsibility” of each Respondent – the fact that a particular contravention led in fact to a comparatively modest underpayment of entitlements, it was submitted, put the “moral responsibility” of the offending Respondent at the very lower end of the penalty regime. The problem with approaching the calculation by reference to the maximum penalty and thereafter applying a “discount” for co-operation, as it was submitted, was to start the process of calculation at the wrong end. Where a contravention led to a comparatively modest underpayment of an entitlement, the starting point in the process of calculation – so the Respondents contended – should be a comparatively modest penalty to which there was thereafter subjected to any reduction for co-operation. The approach of the Fair Work Ombudsman, it was urged on behalf of the Respondents, was “too mathematical” and diverted attention from the actual conduct which constituted the contravention.

45 During the course of closing submissions, Counsel for the Respondents settled upon a submission that the order in which any quantification of penalty was to be approached was to:

calculate the maximum penalty and to thereafter weigh-up against that maximum the “objective seriousness” of the offending conduct; and

apply to the resulting calculation a discount to reflect co-operation.

Counsel for the Respondents accepted that:

the starting point for any process of quantification was the maximum penalty set by the Legislature;

and that, however calculated:

the “totality principle” was a final check on the overall penalty.

46 But this difference in approach, it is respectfully considered, is in many cases – if not all cases – a difference without substance. So much follows from the fact that it matters not – at least in the present case – in which order the calculation is performed.

47 On the approach of the Respondents, assuming a maximum penalty of $50,000; that the “objective seriousness” of the contravention is somewhere towards the lower end of the maximum penalty that could be imposed; and that there should be a reduction of 25% for co-operation, the Respondents’ process of calculation would be as follows:

Maximum penalty | Objective seriousness (including a consideration of adverse inferences) | Discount for co-operation (e.g., 25%) | Penalty |

$50,000 | $12,500 | $3,125 | $9,375 |

If the Fair Work Ombudsman’s approach were to be pursued, the comparable hypothetical calculation could be as follows:

Maximum penalty | Less discount for co-operation (e.g., 25%) | Range of penalty (25%) | Penalty |

$50,000 | $37,500 | $9,375 | $9,375 |

The same “end result” follows because – on the assumptions made – it matters not in which order the process of calculation is undertaken.

48 The substance of the Respondents’ case lay not at all in the order in which the process of calculation was undertaken but in an assessment of the “objective seriousness” of the contravention.

49 As an instance of the divergent approaches, on the approach of the Fair Work Ombudsman it was submitted that an appropriate penalty to be imposed on YBF Australia for its failure to pay casual loadings pursuant to cll 13.2 and 25.5(b) to the Fast Food Award was in the range of $5,737.50 to $7,650; on the approach of the Respondents the appropriate penalty was $2,000 to $3,000, calculated in their submissions as follows:

Provisions of Award/ FW Act | Description of contravention | Under-payment (If any) | Max penalty | Discount | Max after discount | Specific objective seriousness and factors | Range of penalty sought | Total penalty sought |

FW Act s 45 (breach of Modem Award) | Failure to pay casual loading: cll 13.2 and 25.5(b) to the Fast Food Award | $4,742.17 (total) | $51,000 | 25% |

| Low range: • The Respondent relies upon the factors in the YWS table as far as they relate to and can be attributed to the Second Respondent and are not double counted i.e, If matters have already been taken into account caution should be exercised in how and whether those matters are taken into account again. Factors going to the objective seriousness of offending include: • YBF Australia was the party specifically reminded in 2014 about casual wages and that $12 per hour was not acceptable • YBF Australia was the party with effective control of the World Square Store for July-December 2014, and ability to set wages and conditions • YBF is the head office and master franchisor of Yogurberry in Australia • Involvement in contraventions only for 6 month period |

|

$2000- $3000 |

These revised calculations were, self-evidently, based upon the format provided in the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Annexure, deleting the steps in the method of calculation shunned by the Respondents.

50 The difference between the parties as to the approach to be pursued ultimately distilled down to the Respondents’ submission that the “objective seriousness” of the contraventions was significantly less than that advanced on behalf of the Fair Work Ombudsman.

51 That submission of the Respondents is rejected. It pays too little regard (in particular) to:

the conduct of the Respondents in not retaining records, and the adverse inferences that have been drawn as against the Respondents in respect to that conduct;

the failure of the Respondents to co-operate in respect to the provision of any financial information, and the adverse inferences that have been drawn against the Respondents occasioned by that failure; and

the need for specific deterrence.

The conduct of the Respondents, both in respect to the contraventions that have been admitted and in respect to the limited co-operation extended to the Fair Work Ombudsman leads to the conclusion that the Respondents simply regard the prospect of a penalty being imposed as the “cost of doing business”. That approach to their business undertakings should be firmly rejected. Warnings previously given by the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman have not met with any apparent change in attitude on the part of the Respondents; the quantum of penalties advanced on behalf of the Respondents, it is respectfully concluded, would serve as little future deterrence.

52 Although these matters, it is respectfully concluded, lead to the rejection of the overall quantum of penalties urged upon the Court by the Respondents, care must be taken to ensure that these particular matters are considered in the context of the facts in their entirety, including the co-operation of the Respondents in the preparation of the Statement of Agreed Facts.

53 With reference to the Respondents’ submission that the “particular [Respondent’s] role in the contravention” should be constantly borne in mind to “avoid inappropriately double counting matters that have been taken into account in relation to another Respondent”, it is noted that:

from about November 2013 to July 2015, the First Respondent, Yogurberry World Square, was the entity which employed all of the employees at the World Square Yogurberry store;

prior to the period the subject of this proceeding, the Second Respondent, YBF Australia, directly operated the World Square Yogurberry store, and was the employer of that store’s employees. Thereafter, YBF Australia had knowledge of, and participated in establishing rates of pay, making payment of wages, determining hours of work, and dealing with employment-related matters in respect to the employees;

in November 2013 the Third Respondent, CL Group, was also set up and became responsible for accounting, payroll, operational and logistical functions for Yogurberry stores in Australia. Thereafter, CL Group also had knowledge of, and participated in establishing rates of pay, making payment of wages, determining hours of work, and dealing with employment-related matters in respect to the employees; and

the Fourth Respondent, Soon Ok Oh, was the sole director and company secretary of CL Owner Pty Ltd, being the company which owned Yogurberry World Square, and was an “officer” of the three corporate Respondents. Ms Oh was the person who set the rates of pay to employees, gave instructions to the manager of the World Square store, and occasionally gave directions to the employees personally.

54 The penalties that have been imposed, it is concluded, take into account this submission.

CONCLUSIONS

55 Although specific reference has been made to a number of considerations relevant to the quantification of penalties, each of the considerations referred to in Kelly have been considered. Specific reference has been made to a number of discrete considerations by reason of the fact that these considerations were the ones which assumed particular prominence during the course of the hearing.

56 On the facts of the present case, and only after consideration has been given to the facts in their totality, it is concluded that:

deterrence as a factor in the quantification of penalties assumes particular relevance;

as does, albeit to a lesser extent:

the total failure on the part of the Respondents to co-operate in respect to disclosing any detail of their financial circumstances.

57 It is considered that the penalties which should be imposed, in respect to each of the Respondents is as follows:

Yogurberry World Square $75,000

YBF Australia $25,000

CL Group $35,000

Soon Ok Oh $11,000

Bearing in mind the caution to ensure that any penalty is appropriate, the application of the “totality” principle as a “final check” only reinforces the conclusion that these are the penalties that should be imposed.

58 It is further considered that each of the declarations as jointly recommended by the parties should be made, together with the order for the audit of the corporate Respondents. An order requiring an audit to be undertaken has previously been made in Fair Work Ombudsman v Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1034. Katzmann J there concluded (without alteration):

[1134] The Ombudsman sought orders requiring GPS to undertake (or engage an appropriately qualified third party to undertaken) an audit of its compliance with the FW Act and to provide the audit report (including a statement of the methodology) to the Ombudsman. She asked that the report be accompanied by details of any contraventions, the steps GPS would take to rectify the contraventions, and the time by which the rectification will occur.

[1135] She also sought orders requiring GPS to engage qualified professionals to provide training to the company about its obligations, and to provide the details of that training to her.

[1136] In the light of GPS’s flagrant disregard for the law in the face of numerous attempts by the Ombudsman to bring its legal obligations to its attention, these orders are eminently sensible.

The circumstances in which such an order should be made should not be confined, nor was her Honour seeking to confine the circumstances, to those in which there has been a “flagrant disregard for the law”. On the facts of the present case, adverse inferences have been drawn as to the reasons and objectives sought to achieved by the Respondents which could equally be characterised as a “flagrant disregard for the law”. An order requiring an audit to be undertaken may also be made where, for example, the full extent of the contraventions committed by a respondent may be unknown or where an audit is required to identify the deficiencies of a respondent which need to be remedied.

59 There is no difficulty, it should be recalled, with a regulator and a respondent making submissions as to penalty and the form of orders to be made, and no difficulty with a Court making orders pursuant to a proposed minute of consent orders: e.g., Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Padbury Mining Ltd [2016] FCA 990 at [61] to [65] per Siopis J.

60 There is no reason why the Respondents should not pay the costs of the Fair Work Ombudsman.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT DECLARES:

1. The First Respondent, Yogurberry World Square Pty Ltd, contravened the following civil remedy provisions:

(a) section 45 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”), by failing to classify Mr M Kim, Ms Lee, Ms Cho, and Ms K Kim (together, the “Employees”) as prescribed by clause 16.1 of the Fast Food Industry Award 2010 (the “Fast Food Award”);

(b) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay Mr M Kim and Ms K Kim the minimum rates of pay as prescribed by clause 17 of the Fast Food Award;

(c) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay Ms Cho and Ms Lee the minimum junior rates of pay as prescribed by clause 18 of the Fast Food Award;

(d) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees casual loading as prescribed by clause 13.2 and sub-clause 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award;

(e) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees additional penalty amounts for work performed between 9.00pm and midnight on Monday to Friday as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(a)(i) of the Fast Food Award;

(f) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees Saturday penalty rates as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(b) of the Fast Food Award;

(g) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees Sunday penalty rates as prescribed by sub-clause 25.5(c)(ii) of the Fast Food Award;

(h) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of Mr M Kim, Ms Cho and Ms Lee public holiday penalty rates as prescribed by clause 30.3 of the Fast Food Award;

(i) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to engage each of the Employees for a minimum of three hours on all shifts as prescribed by clause 13.4 of the Fast Food Award;

(j) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of the Employees a special clothing allowance as prescribed by sub-clause 19.2(b)(ii) of the Fast Food Award;

(k) section 45 of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make superannuation contributions on behalf of each of the Employees, as prescribed by clause 21.2 of the Fast Food Award;

(l) sub-section 323(1) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to pay each of Ms Cho, Ms Lee and Ms K Kim in full;

(m) sub-section 535(1) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make and keep records for Mr M Kim in the period from in or about July 2014 to 21 September 2014, as prescribed by the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Regulations);

(n) sub-section 535(2) of the Fair Work Act, by failing to make and keep records for each of the Employees which included information prescribed by sub-regulations 3.32(d), 3.32(e), 3.32(f), 3.33(1)(a), 3.33(1)(b), 3.33(3), and 3.37(1) of the Fair Work Regulations; and

(o) sub-section 536(1) of the Fair Work Act by failing to provide pay slips to each of the Employees within one day of paying an amount to them in relation to the performance of work.

2. The Second Respondent, YBF Australia Pty Ltd, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, as set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above, in the period from in or about July 2014 to in or about December 2014.

3. The Third Respondent, CL Group Pty Ltd, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, as set out in Declarations 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(i), 1(j), 1(k), 1(l), 1(n) and 1(o) above, in the period from in or about January 2015 to 17 May 2015.

4. The Fourth Respondent, Ms Soon Ok Oh, was involved, pursuant to section 550 of the Fair Work Act, in the contraventions committed by the First Respondent, in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above, in the period from or about July 2014 to 17 May 2015.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, the Second and Third Respondents jointly, at their expense, are to engage a third party with qualifications in accounting or workplace relations to undertake an audit of compliance with the Fair Work Act and the Fast Food Award on the following terms:

(a) the audit period will be the period commencing on the date of this Order and ending six months after the date of this Order (the “Audit Period”);

(b) the audit is to be completed within two months of the date of this Order (“Audit Completion Date”);

(c) the audit will apply to all employees and persons otherwise engaged to perform work for any store in Australia trading under the “Yogurberry” brand and for which the Second and Third Respondents have responsibility as the master franchisor and payroll company respectively, at any time during the Audit Period (collectively, the “Yogurberry Employees”);

(d) according to each Yogurberry Employee's classification of work, category of employment and hours of work worked during the Audit Period, the audit will assess compliance with the following obligations:

(i) wages and work related entitlements under the Fast Food Award; and

(ii) record keeping and pay slip obligations in Division 3 of Part 3-6 of the Fair Work Act; and

(e) within 30 days of the Audit Completion Date, the Second and Third Respondents will jointly provide to the Applicant:

(i) a copy of the audit report which will include a statement of the methodology used in the audit; and

(ii) written details of any contraventions identified in the audit, the steps the Second and Third Respondents will take to rectify any identified contravention(s) and by when the rectification will occur.

2. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, the Second, Third and Fourth Respondents are to engage, at their own expense, a person or organisation with professional qualifications in workplace relations, to provide training to the Second to Fourth Respondents (and any other person holding the position of Director or Company Secretary of the Second and Third Respondents at the date of this Order):

(a) within three months of the date of this Order; and

(b) that covers obligations on employers under the Fast Food Award, the Fair Work Act and the Fair Work Regulations.

3. Pursuant to sub-section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act, within 30 days of completing the training set out in Order 2 above, the Second, Third and Fourth Respondents are each to provide to the Applicant, in writing:

(a) the date on which the training was completed;

(b) the name of the person or organisation that conducted the training; and

(c) the details of the methods of delivery of the training and the content of the training.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT:

4. The First Respondent is to pay a penalty of $75,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its contraventions set out in Declaration 1 above.

5. The Second Respondent is to pay a penalty of $25,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j)and 1(k) above, in the period from in or about July 2014 to in or about December 2014;

6. The Third Respondent is to pay a penalty of $35,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for its involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(i), 1(j), 1(k), 1(l), 1(n) and 1(o) above, in the period from or about January 2015 to 17 May 2015; and

7. The Fourth Respondent is to pay a penalty of $11,000 pursuant to sub-section 546(1) of the Fair Work Act for her involvement in the contraventions set out in Declarations 1(b), 1(c), 1(d), 1(e), 1(f), 1(g), 1(h), 1(j) and 1(k) above in the period from in or about July 2014 to 17 May 2015.

8. Pursuant to sub-section 546(3)(a) of the Fair Work Act, each of the Respondents is to pay the respective penalty amount to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth.

9. Each of the Respondents is to pay the respective penalty amount within 28 days of these Orders.

10. The Respondents are to pay the costs of the Applicant.

I certify that the preceding sixty (60) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Flick. |