FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Henley Arch Pty Ltd v Lucky Homes Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1217

File number: | VID 360 of 2015 |

Judge: | BEACH J |

Date of judgment: | 13 October 2016 |

Catchwords: | COPYRIGHT – infringement – artistic work – project home floorplan – whether alleged infringing work objectively similar – whether alleged infringing work reproduced a substantial part – three-dimensional form derived from two-dimensional work – defence of innocent infringement – Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 115(3) – loss of opportunity damages – loss of profits – additional damages – Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 115(4) – claims upheld – cross-claim under contractual indemnity – cross-claim for misleading or deceptive conduct |

Legislation: | Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 10, 13, 14, 21, 31, 32, 35, 115 Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) ss 24AE, 24AF, 24AI |

Cases cited: | Barrett Property Group Pty Ltd v Carlisle Homes Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 375 Clarendon Homes (Aust) Pty Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd (1999) 46 IPR 309; [1999] FCA 1371 Coles v Dormer (No 2) (2016) 330 ALR 151; [2016] QSC 28 Dart Industries Inc v Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 179 CLR 101 Dynamic Supplies Pty Ltd v Tonnex International Pty Ltd (No 3) (2014) 312 ALR 705; [2014] FCA 909 Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd (1999) 87 FCR 415 Facton Ltd v Rifai Fashions Pty Ltd (2012) 287 ALR 199; [2012] FCAFC 9 Flags 2000 Pty Ltd v Smith (2003) 59 IPR 191; [2003] FCA 1067 Futuretronics.com.au Pty Ltd v Graphix Labels Pty Ltd (No 2) (2008) 76 IPR 763; [2008] FCA 746 Golden Editions Pty Ltd v Polygram Pty Ltd (1996) 61 FCR 479 IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458 Luxottica Retail Australia Pty Ltd v Grant (2009) 81 IPR 26; [2009] NSWSC 126 Milwell Pty Ltd v Olympic Amusements Pty Ltd (1999) 85 FCR 436 Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd (2012) 248 CLR 42 Ron Englehart Pty Ltd v Enterprise Constructions (Aust) Pty Ltd (2012) 95 IPR 64; [2012] FCAFC 4 Sellars v Adelaide Petroleum NL (1994) 179 CLR 332 Streetworx Pty Ltd v Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd (2014) 110 IPR 82; [2014] FCA 1366 SW Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 Tamawood Ltd v Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (2015) 112 IPR 439; [2015] FCAFC 65 Tamawood Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd (2004) 61 IPR 378; [2004] FCAFC 78 Tolmark Homes Pty Ltd v Paul (1999) 46 IPR 321; [1999] FCA 1355 |

Dates of hearing: | 29, 30, 31 August, 1, 2, 8 September 2016 |

Date of last submissions: | 27 September 2016 |

Registry: | Victoria |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Copyright and Industrial Designs |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | 295 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr E J C Heerey QC with Mr T D Cordiner |

Solicitors for the Applicant: | Ashurst Australia |

Counsel for the First and Second Respondents: | Mr A W Sandbach RFD |

Solicitors for the First and Second Respondents: | Goldsmiths Lawyers |

Counsel for the Third and Fourth Respondents: | Mr D L Epstein |

Solicitors for the Third and Fourth Respondents: | Legoll Legal |

ORDERS

JUDGE: | BEACH J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 13 OCTOBER 2016 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents pay compensatory damages to the applicant in the sum of $34,400.

2. The first and second respondents pay, collectively, additional damages to the applicant in the sum of $25,000.

3. The third respondent pay additional damages to the applicant in the sum of $10,000.

4. The first and second respondents’ cross-claim against the third and fourth respondents be dismissed.

5. On the third and fourth respondents’ cross-claim against the first and second respondents, the first and second respondents pay damages to the third and fourth respondents quantified in such sum as the third and fourth respondents are liable to pay and do pay to the applicant under order 1 and to pay to the third respondent damages quantified in such sum as to one-half of his liability to the applicant that he pays under order 3.

6. Within 14 days of the date hereof, the applicant file and serve submissions (limited to five pages) on the question of the costs of its originating application and on any pre-judgment interest, if any, allowable.

7. Within 14 days of the receipt of the applicant’s submissions, the respondents file and serve submissions (limited to five pages for the first and second respondents and limited to five pages for the third and fourth respondents) on the topics referred to in order 6 and on the costs of the cross-claims.

8. Within 14 days of the receipt of any respondent’s submission on the costs of any cross-claim, any other respondent may file and serve submissions (limited to three pages) in response.

9. Liberty to apply on reasonable notice.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The applicant (Henley Arch) operates a home building business throughout Australia, trading under various business names. One of these divisions trades under the name of “MainVue Homes”, which markets and constructs homes according to a series of project home designs including the “Amalfi” series.

2 The first respondent (Lucky Homes) also operates a home building business in Victoria, but of a lesser scale to Henley Arch’s Victorian operations. The second respondent (Mr Shafiq) is the managing director and sole shareholder of Lucky Homes. The third and fourth respondents are husband and wife (the Mistrys) and the registered proprietors of Lot 828, Circus Avenue, Point Cook, Victoria (the Circus Avenue property).

3 Henley Arch has contended that it owns the copyright subsisting in an original house design (specifically a floorplan) called the “Amalfi AM532” with the “Avenue” façade applied to the house (the Amalfi Avenue floorplan). The Amalfi Avenue floorplan is said to be an original artistic work.

4 Henley Arch claims that the respondents infringed or authorised the infringement of copyright in the Amalfi Avenue floorplan by preparing or authorising the preparation of a floorplan which involved copying a substantial part of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan and which was objectively similar to the copyright work. It is also said that there has been infringement by the three-dimensional reproduction of the two-dimensional Amalfi Avenue floorplan, ie by the construction of the Mistrys’ residential dwelling on the Circus Avenue property.

5 Henley Arch has sought a declaration that the conduct of the respondents constituted copyright infringement, injunctions against the respondents restraining further infringing conduct, delivery up of the infringing plans, damages and additional damages.

6 Before trial, the Mistrys denied any copyright infringement and claimed that they had an implied licence to use the copyright in the designs. However, those assertions were not pressed at trial. But they contend that they can rely on the defence of innocent infringement under section 115(3) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the Act), and are therefore not liable to Henley Arch. Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq have denied infringement. They assert that there has been no reproduction of a substantial part of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan, whether in two dimensions or three dimensions. But in contrast to the Mistrys’ defence, they do not rely upon any defence of innocent infringement.

7 By way of a cross-claim against the Mistrys, Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq have sought to rely on an express term in the building contract executed between Lucky Homes and the Mistrys under which the Mistrys warranted that any building plans (and the copyright therein) provided to Lucky Homes by the Mistrys were owned by the Mistrys. Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq have contended that the Mistrys breached the relevant warranty and are obliged to indemnify them for any losses suffered if they were found to have engaged in copyright infringement at the suit of Henley Arch.

8 By way of a cross-claim against Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq, the Mistrys have asserted that if they were found to have engaged in non-innocent copyright infringement, then they were the victims of misleading or deceptive conduct on the part of Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq. The Mistrys have also asserted that if they were found liable for copyright infringement and I find that Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq were also engaged in copyright infringement, then they are concurrent wrongdoers under section 24AI of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic), and their liability should be proportionately limited as to the loss or damage suffered by Henley Arch, having regard to the extent of their responsibility and Lucky Homes’ and Mr Shafiq’s responsibility for that loss or damage. This concurrent wrongdoers contention is misconceived as I will later explain.

9 For the following reasons, Henley Arch’s claims for copyright infringement succeed against all respondents. I reject the principal defence of Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq of no reproduction of a substantial part. I also reject the principal defence of the Mistrys of innocent infringement. In my view, as against the respondents, Henley Arch is entitled to an award of compensatory damages in the amount of $34,400. Further, I will award additional damages of $25,000 collectively against Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq and additional damages of $10,000 against Mr Mistry only. Henley Arch has also sought declarations and injunctions, but in my view there is no utility in granting such relief. My reasons adequately set out the principal findings and the basis for those findings. As to injunctions, there is no real prospect of further infringement. As far as the Mistrys are concerned, their home has been built. So far as Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq are concerned, I am satisfied that their infringement of copyright was a once off occasion. Their normal business practice has been to prepare or use house designs designed or procured by themselves (with or without the use of a subcontractor) rather than to use or modify the designs of their competitors. As to each of the cross-claims, I propose to dismiss the cross-claim of Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq but to allow the cross-claim of the Mistrys for reasons that I will later explain.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

10 It is convenient to first set out the background of what transpired.

Development of the Amalfi floorplans

11 Jeff Bugeja is an Australian citizen and had been employed by Henley Arch as a national design manager since December 2009. Mr Bugeja’s duties at Henley Arch consisted of designing new project homes for the Henley Properties Group, which involved drafting floorplans and elevation plans for project homes under the “MainVue” brand, as well as other brand names. Mr Bugeja also oversaw the construction of display homes built in accordance with his designs.

12 Mr Bugeja had been instructed from time to time to prepare a smaller version of a project home, which was based on a certain design, to enable Henley Arch to market and sell a smaller version of the same project home for a smaller lot size and at a lower retail price. Henley Arch generally only builds the larger version for use as a display home.

13 In early April 2010, Lizzie Kind, the chief operating officer of Henley Arch instructed Mr Bugeja to design a new single storey project home for the MainVue brand, which was to be displayed at the Saltwater development in Point Cook. The MainVue brand was to be what Henley Arch described as a “luxury brand”. The design was to be a new concept and not a variation of any earlier Henley Arch project home.

14 In April 2010, Mr Bugeja drew the first sketches of the Amalfi AM632 floorplan. During the course of April to September 2010, Mr Bugeja drew various iterations of the Amalfi AM632 floorplan. Those iterations showed different sizes of the Amalfi AM632 floorplan, with various rooms being differently located. There was a similar design concept between all of these iterations and they became part of the “Amalfi” series of homes.

15 In September 2010, Mr Bugeja produced the Amalfi AM628 floorplan. Further, in January 2011, the Amalfi AM528 floorplan was finalised. The Amalfi AM528 floorplan was based on the AM628 floorplan. Further, during December 2010 to January 2011, Mr Bugeja developed the Amalfi AM532 floorplan. The Amalfi AM532 floorplan was based on the Amalfi AM528 floorplan. The Amalfi AM532 floorplan differed from the Amalfi AM528 floorplan in that an additional bedroom was included at the back of the house. On 19 February 2011, Henley Arch published the Amalfi AM532 floorplan in a brochure which was made available to the public.

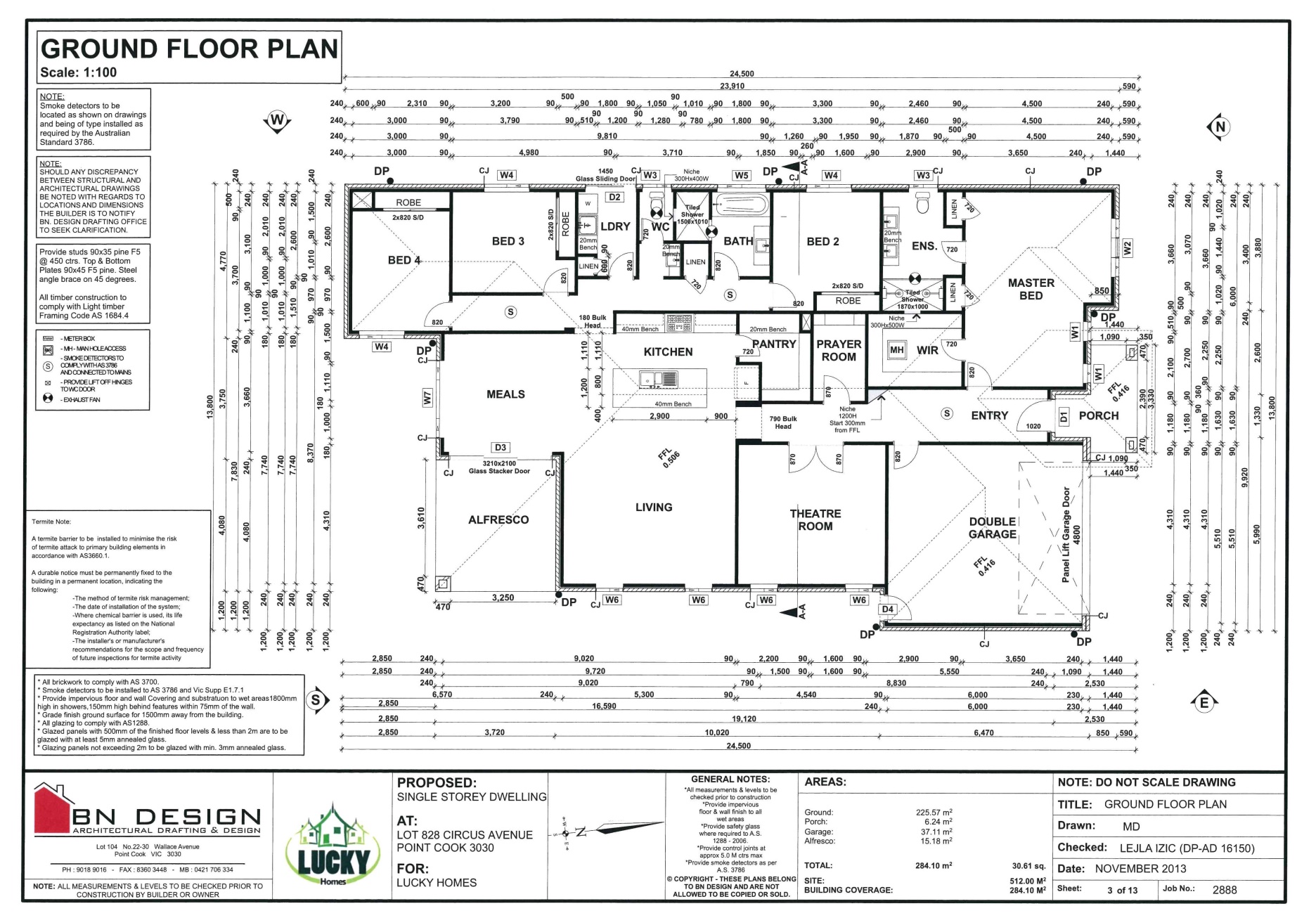

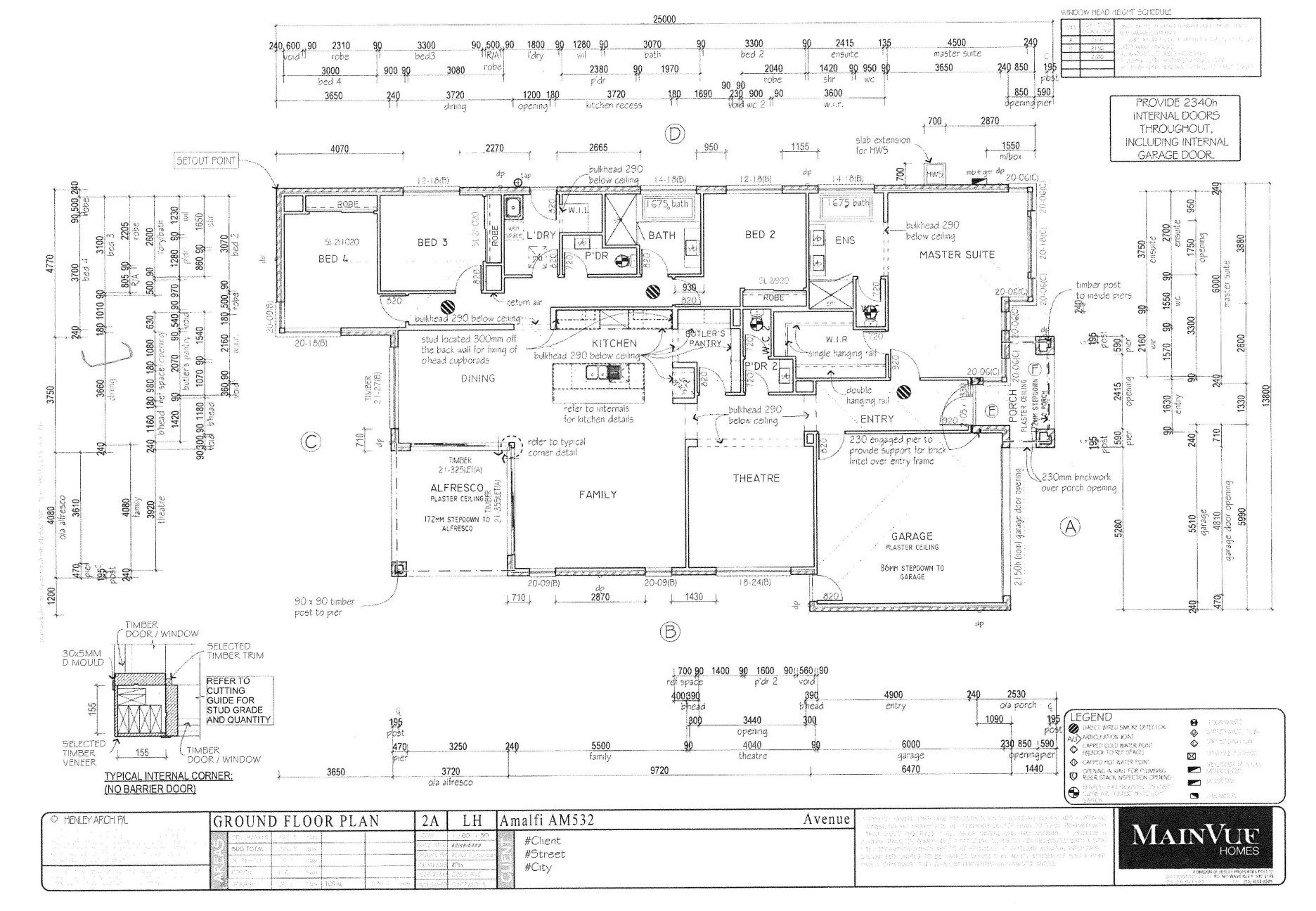

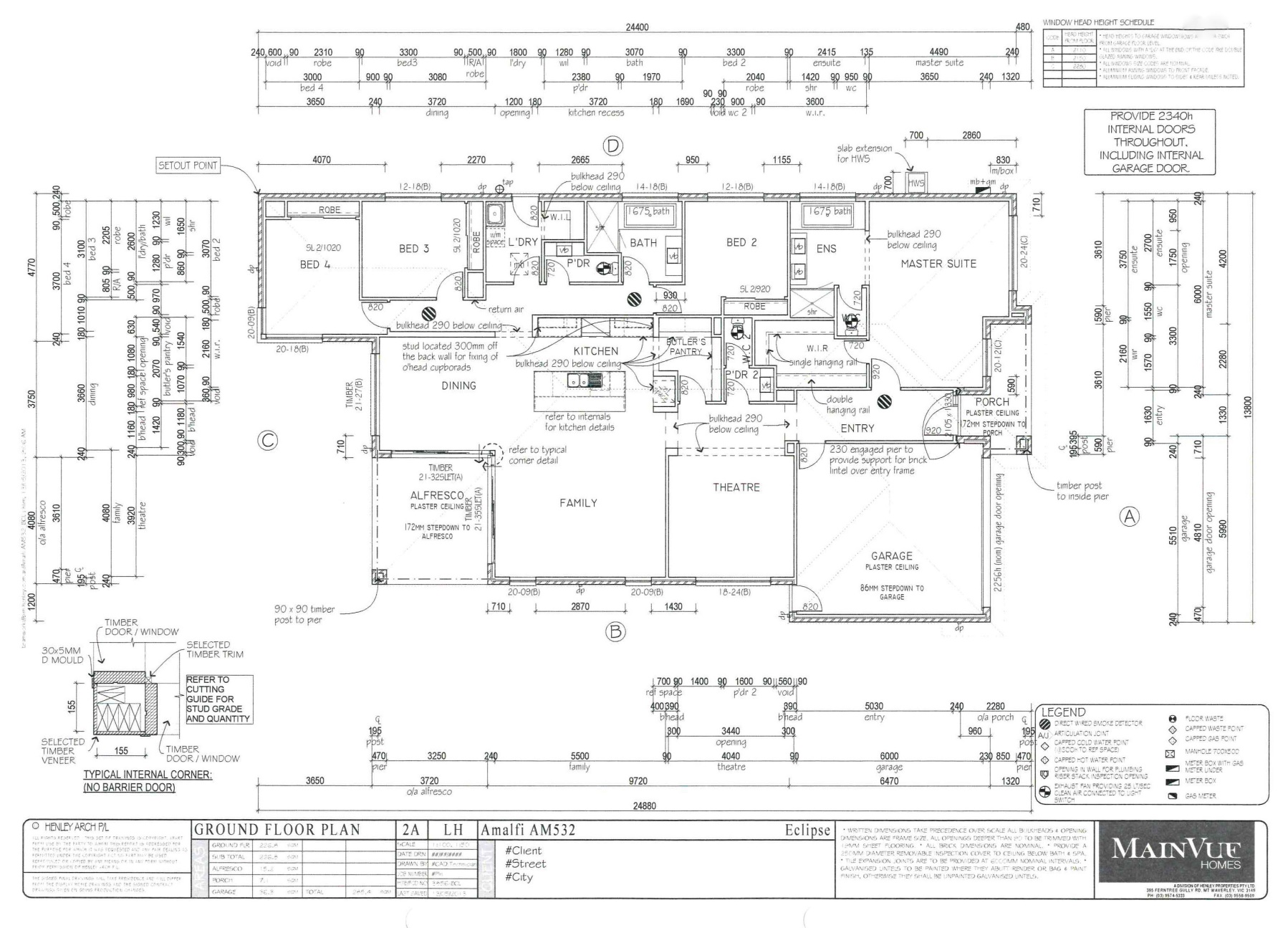

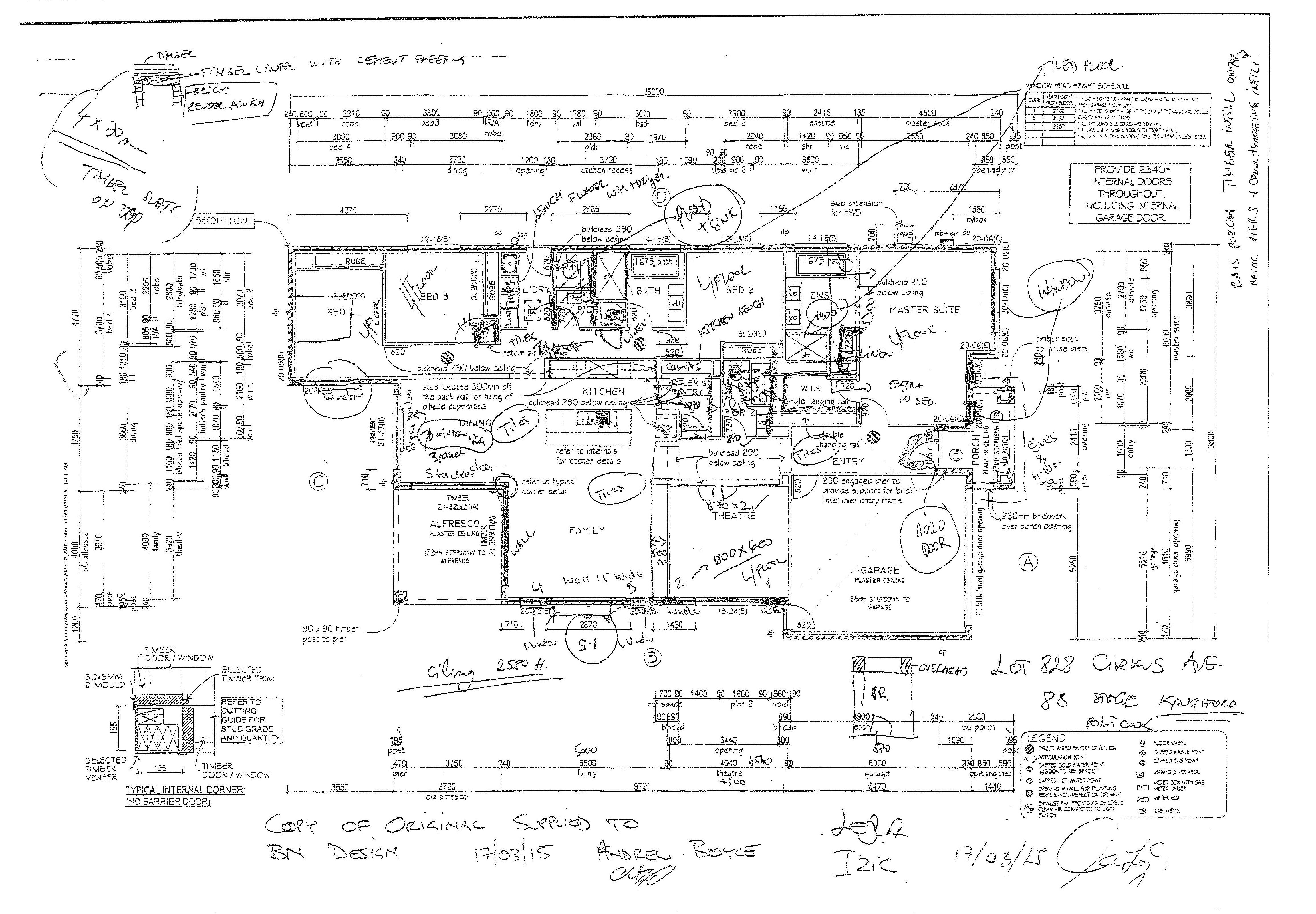

16 Henley Arch’s master plans team produced master drawings of the Amalfi AM532 floorplan. The difference between each of the master drawings of the Amalfi AM532 floorplan was the façade of the house. For example, the AM532 Avenue floorplan applied the “Avenue” façade to the Amalfi AM532 floorplan. A copy of the Amalfi AM532 floorplan with the “Avenue” façade is annexure A to my reasons. Similarly, the AM532 Eclipse floorplan applied the “Eclipse” façade to the Amalfi AM532 floorplan. A copy of the Amalfi AM532 floorplan with the “Eclipse” façade is annexure B to my reasons. The Avenue façade was a more expensive option than the Eclipse façade. The Eclipse façade was offered by Henley Arch as the default or standard option. There were also render options such as “part” or “front” render options, which were available for each of the façade options and involved additional cost to the prospective homeowner.

Dealings between the Mistrys and Henley Arch

17 In 2010 to 2011, the Mistrys purchased and constructed their first house under a house and land package from Henley Arch. According to the evidence led before me, the Mistrys were well contented with Henley Arch’s design and construction work on their first house.

18 On 19 March 2013, the Mistrys entered into a contract of sale to purchase the Circus Avenue property, ie the land only for $279,000; the land was part of a subdivision development known as Stage 8, “Kingsford”, Point Cook. Settlement was to be 10 days after registration of the relevant plan of subdivision and the issue of title. This did not occur until the end of September 2013.

19 On 5 April 2013, the Mistrys visited the MainVue display homes at Saltwater Coast in Point Cook. At this time, the Mistrys expressed interest in having Henley Arch construct a project home for the Circus Avenue property. During that visit to the display homes at Saltwater Coast, the Mistrys paid Henley Arch a deposit of $800.

20 At some stage, although this was denied by Mr Mistry, Henley Arch’s step by step guide was provided to the Mistrys which set out the process involved from the initial consultation with Henley Arch through to the commencement of construction. The guide provided as follows:

(a) Under Step 1, what was contemplated was an initial consultation with a Henley Arch consultant which involved an inspection of a display home of the client’s desired MainVue house. The client then paid Henley Arch a fully-refundable $850 deposit to secure the base house price and for Henley Arch to provide an initial quotation based on the client’s selection of the house, façade and other inclusions including the electrical layout of the chosen home; I note that the Mistrys though only paid $800. Once the client had confirmed their various options to customise their chosen home, Henley Arch issued a final quotation which reflected those selected options. The client then paid Henley Arch a second deposit of $650 prior to signing the final quotation. The payment of the total deposit of $1500 ($850 initial deposit and $650 second deposit) then triggered the creation of a tender document based on the client’s desired options. The $1500 deposit was not refundable once a soil test and site survey had been ordered.

(b) Step 2 involved the client making arrangements to finance the new house. Henley Arch required the client to obtain finance pre-approval. At this stage, Henley Arch confirmed whether the desired house was able to physically fit on the client’s land.

(c) Step 3 involved a colour styling consultation with an interior designer. The purpose of the consultation was to confirm internal and external colour selections.

(d) Step 4 involved Henley Arch issuing the client a tender document which incorporated the client’s choice of façade, catalogue options (such as render options) and an accompanying site plan for the house. Once the client accepted the tender, they were required to pay Henley Arch a further $1650, which was non-refundable, in order for Henley Arch to prepare the working drawings for the construction of the house.

(e) Step 5 involved Henley Arch providing the client with a HIA New Homes Building Contract for review and, if appropriate, execution. Henley Arch arranged with the client an appointment to sign the contract at a MainVue sales office. Once the client signed the contract, they were required to pay a further deposit, being the balance of 3% of the tendered price less the amount of the deposit already paid. The client also needed to provide proof that they had obtained the appropriate finance to meet the value of the contract.

(f) Step 6 involved Henley Arch submitting applications for building permits and finalising the construction drawings. Once the client provided confirmation from the client’s financier that the funds could be released for payments to be progressively made to Henley Arch, construction then commenced.

21 On 30 April 2013, Henley Arch sent the Mistrys a provisional sales quotation which included a proposed siting plan for an Amalfi house (AM532) with an Eclipse façade applied. The provisional sales quotation explained that the proposed Eclipse façade could have a “part render” option which would cost an additional $900 over the base price.

22 In early May 2013, the Mistrys visited the MainVue office of Henley Arch at Williams Landing. It appears that at this time the Mistrys may have obtained a copy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan during this visit.

23 On 10 May 2013, Henley Arch provided the Mistrys a further provisional sales quotation and proposed siting plan for an Amalfi AM532 design with an Avenue façade. The quote stated that applying the Avenue façade would cost an additional $10,400 over the base price.

24 On 21 May 2013, Mr Mistry signed a Henley Arch “sales siting document”. That document showed the word “Avenue” crossed out by hand and replaced with the word “Eclipse”. One can infer that from this time the Mistrys no longer wanted a house with the Avenue façade, but instead one with the “Eclipse” façade. I am also able to infer that one of the reasons that the Mistrys wanted to proceed with the $900 Eclipse façade instead of the $10,400 Avenue façade was due to budgetary constraints in relation to their finances at this time.

25 On 23 May 2013, Henley Arch sent the Mistrys a provisional sales quotation, which was identified as “Version 4”, of $193,900 for the Amalfi AM532 design with the Eclipse façade “part render” option and included a number of amendments (including to price) as required by the Mistrys and the physical parameters of the site itself.

26 Page 10 of the Version 4 sales quotation contained the following text:

I/we acknowledge that information contained or embodied in this sales quotation document and any and all documents (whether in material or electronic form) disclosed (“Information”) to you by or on behalf of Henley Property Group (“Henley”) is and remains at all times confidential to and the exclusive property of Henley.

I/we undertake to use all reasonable endeavours to keep Information secure against unauthorised loss, use or disclosure. I/we also undertake that such Information will be kept confidential and shall be used for the sole purpose for which it was disclosed to you.

27 On 29 May 2013, Henley Arch provided the Mistrys with a further provisional sales quotation (identified as “Version 5”) for the Amalfi AM532 design but with an Eclipse façade “front render” option which cost an additional $3000 above the base price. The quotation also contained various other additional anticipated costs that reflected the Mistrys’ instructions. This document was signed by the Mistrys. The text on page 10 of the Version 5 provisional sales quotation was identical to page 10 of the Version 4 provisional sales quotation. The Mistrys’ signatures appeared immediately below these acknowledgements and undertaking. So, at this time at the latest, the Mistrys knew or, at the least, ought to have known of Henley Arch’s apparent ownership of its various designs and that they were not free to use the floorplans given to them or obtained by them as they saw fit. The Mistrys gave evidence before me, which I will discuss later, that they never read these acknowledgements. This is surprising. But in any event they agreed that if they had read them, they would have understood their general tenor.

28 In June 2013, the Mistrys and Henley Arch had various discussions about the colour scheme to be applied to the proposed house to be built on the Circus Avenue property.

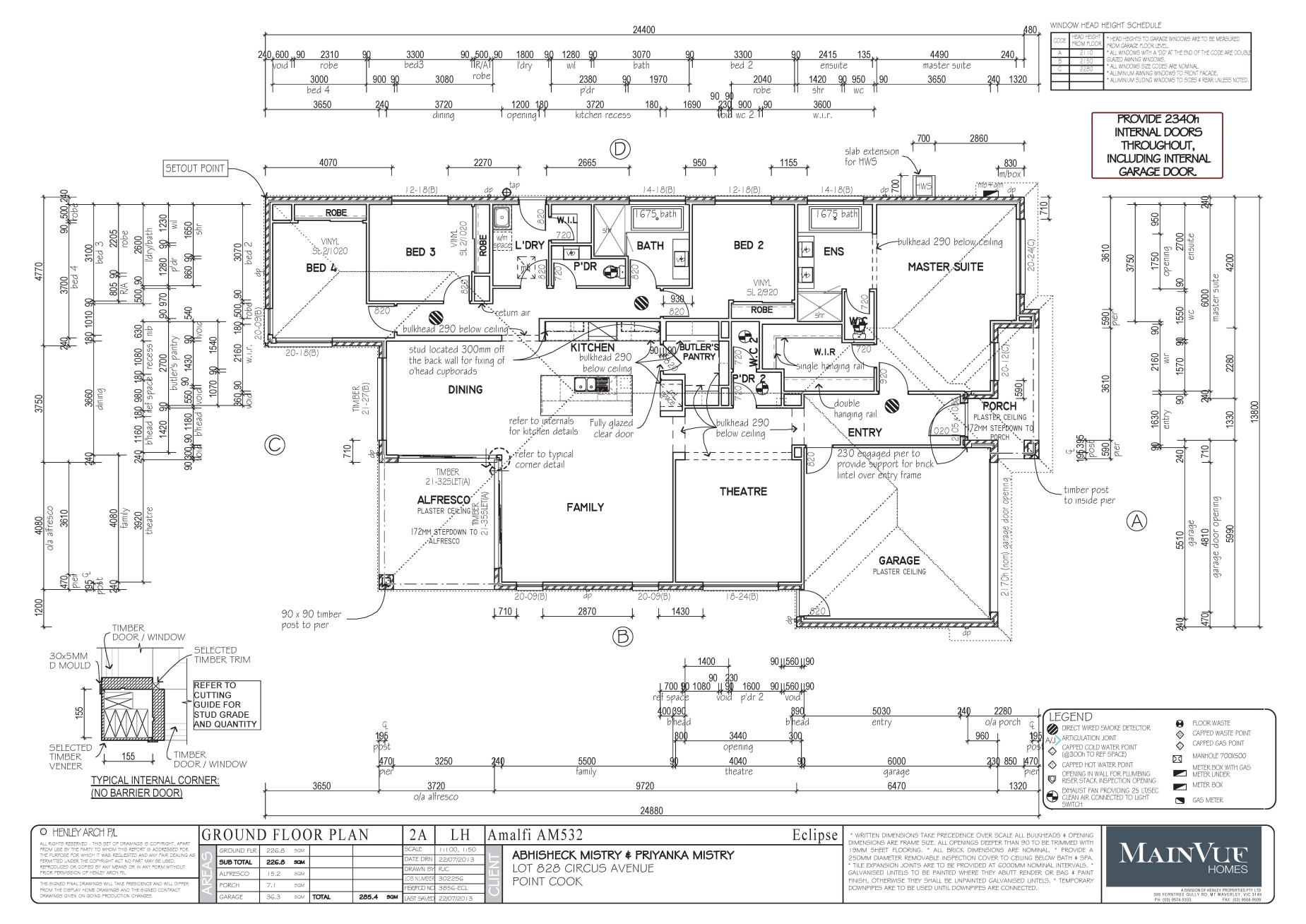

29 On 22 July 2013, Michael Charlesworth, a sales consultant for Henley Arch, emailed the Mistrys a proposed site plan and a floorplan of the Amalfi AM532 with the Eclipse façade “part render” applied. A copy of this floorplan (the Mistrys specific floorplan) is annexure C to my reasons. This floorplan had been prepared by Rosalyn Carter, Henley Arch’s employee, who had used the Amalfi AM532 Eclipse floorplan but incorporated the various amendments requested by the Mistrys and the smaller size required by the site. However, not all of the Mistrys’ requested changes to the base Amalfi AM532 floorplan were included in this floorplan. Usually at this point in the process, Henley Arch did not develop full plans where there was a chance that the client might decide not to proceed to construction or because soil and survey reports were not completed or the land had not yet been “titled”. Henley Arch’s Step by Step Guide under the heading “Step 4 – Tender Agreement” stated that site plans were provided at the tender stage and not working drawings.

30 On 24 July 2013, Henley Arch provided the Mistrys with a document titled “Authorised Tender” and described as “Tender 2” for the house proposed to be built on the Circus Avenue property. This document was signed by the Mistrys either that day or shortly thereafter. The document showed the price for the house ($247,693) to be built in accordance with the Mistrys specific floorplan that had been sent to the Mistrys on 22 July 2013. In accordance with that tender document, the Mistrys paid Henley Arch a deposit of $1650. The tender document contained the following text, which was situated above the Mistrys’ signatures:

I/we acknowledge that information contained or embodied in this tender document and any and all documents (whether in material or electronic form) disclosed (“Information”) to the Owner by or on behalf of the Builder is and remains at all times confidential to and the exclusive property of the Builder.

I/we undertake to use all reasonable endeavours to keep Information secure against unauthorised loss, use or disclosure. I/we also undertake that such Information will be kept confidential and shall be used for the sole purpose for which it was disclosed to the Owner.

31 Between that time and September 2013, further correspondence was exchanged regarding various changes to the tender that the Mistrys wanted. One such request was to convert a particular room, which was then designated to be a powder room, to a prayer room. This was first proposed by the Mistrys at a meeting with Henley Arch on 7 August 2013.

32 On 6 September 2013, Henley Arch provided an authorised tender (Tender 6) to the Mistrys for the Amalfi AM532 with an Eclipse façade “part render” option and various variations to the base house as required by the Mistrys (the September tender). Further, the September tender showed that the “Eclipse – Feature Tiles to 2 Piers (Amalfi Series)” had a price of $2000.91. The September tender also showed that the laundry would have, instead of a standard linen cupboard, a “part broom cupboard and part linen cupboard”. The total price for the house as shown in the September tender was $249,536.93.

33 Later on 6 September 2013, Mr Mistry reminded Henley Arch that he and his wife wished to change the powder room to a prayer room, and asked that the floorplan be amended accordingly.

34 On 9 and 17 September 2013, Mr Charlesworth requested that the Mistrys provide confirmation as to when the transfer of land to the Mistrys of the Circus Avenue property would occur under their land purchase contract.

35 In an email dated 16 September 2013, Mr Mistry wrote to Mr Charlesworth and referred to the September tender saying: “so far what you have given me I am happy with it. So I can sign the contract on that but as per your Step by Step procedure we need to give you 3% of the contract price and also bank letter.”

36 On 17 September 2013, the September tender was signed by the Mistrys and sent to Henley Arch. The September tender contained the following text situated above the Mistrys’ signatures:

I/we acknowledge that information contained or embodied in this tender document and any and all documents (whether in material or electronic form) disclosed (“Information”) to the Owner by or on behalf of the Builder is and remains at all times confidential to and the exclusive property of the Builder.

I/we undertake to use all reasonable endeavours to keep Information secure against unauthorised loss, use or disclosure. I/we also undertake that such Information will be kept confidential and shall be used for the sole purpose for which it was disclosed to the Owner.

37 On 24 September 2013, Mr Mistry asked Mr Charlesworth “how are you coming along with Final drawings and Final Tender? Can you please reply when you get chance?” Mr Charlesworth replied that day saying “Everything is going well … your file is in drafting to make the necessary electrical amendments”.

38 On 25 September 2013, title to the Circus Avenue property was transferred to the Mistrys. As such, and by reason of the position of both parties, the Mistrys could not have entered into a contract to build their home with Henley Arch until 25 September 2013 at the earliest. Henley Arch would not agree to build without the owner having title. The Mistrys could not so contract to build until they had finance in place, but such finance was to be secured by a registered mortgage which could only be given when they had title. The Mistrys did not inform Henley Arch of this title transfer until 7 October 2013.

39 On 1 October 2013, Mr Mistry requested a further update on the status of the contract to build and final drawings, noting that he wished to progress to signing the building contract with Henley Arch and hoped that construction would commence before the end of the year. Mr Charlesworth responded later that morning asking which date Mr Mistry would prefer to set for the contract signing appointment, and expressed his confidence that construction would commence before the end of the year. Mr Charlesworth also asked for confirmation that settlement of the title transfer of the Circus Avenue property had occurred. Following an exchange of emails that afternoon, Mr Charlesworth and Mr Mistry agreed that the Mistrys would sign the building contract with Xavier Pearson of Henley Arch on Saturday 19 October 2013.

40 On 7 October 2013, Mr Mistry requested that the contract signing date be brought forward a week from 19 October 2013 to Saturday 12 October 2013. Mr Charlesworth replied later that day saying that he would check with Mr Pearson as to whether this was possible.

41 On 8 October 2013, Mr Charlesworth advised Mr Mistry that the contract would have to be signed at Henley Arch’s head office at Mount Waverley, and that the appointment would have to be scheduled on a weekday as Mr Charlesworth did not work on Saturdays. Mr Mistry responded by email later that day expressing his confusion; he asserted that he had been told different information by Mr Pearson and Mr Charlesworth. Mr Mistry also stated that he and Mrs Mistry could not sign on weekdays as they worked and had already taken sufficient time off work. Mr Mistry concluded by saying “We need to find some other ways?” As a result, Mr Charlesworth offered to sign after hours on a weekday.

42 On 14 October 2013, Mrs Mistry asked Mr Charlesworth whether he had finalised the “contract, time, date and place” for the signing. Mrs Mistry stated that she and her husband wanted to “have construction started ASAP as land is released and ready to build” and asked whether construction would commence before the year’s end. Further, she asked “if you require anything in this regard please let us know” and signed off: “With many thanks and regards, Priyanka and Abhishek Mistry”.

43 Later that day, Mr Charlesworth informed Mrs Mistry that the signing appointment could be accommodated on a Saturday. He asked whether Saturday 26 October 2013 was a convenient date for signing at either Henley Arch’s head office or its Point Cook sales centre. Mrs Mistry replied that day, thanking Mr Charlesworth for his “prompt reply” and asking to sign the contract on Saturday 2 November 2013 at the Point Cook sales centre. Mrs Mistry also stated “I hope you understand why we want to have things finalised early. Rest all sound good.”

44 On 15 October 2013, Mrs Mistry contacted Mr Charlesworth and indicated that she wanted a further change to the laundry by inserting a single broom cupboard. Mr Charlesworth responded that evening, requesting that the Mistrys confirm a number of matters regarding pricing. He sought confirmation that the Mistrys wanted a “front render” to the façade. Further, he advised that it would cost an additional $1010 for the proposed change to the laundry.

45 Later in the evening of 15 October 2013, Mrs Mistry expressed her confusion to Mr Charlesworth as to how the price of the façade render was calculated. Further, Mrs Mistry expressed her frustration at having her queries relating to the laundry misunderstood, and said that “we are quite upset with the things happening at this moment”. She asked to postpone the signing appointment to 2 November 2013. The full text of her email is as follows:

Hi Michael

Thanks for your reply.

Does that mean, to have full render with tiles on pillar are going to cost $3000 + $2900 = $5900 ???

As we were in impression that pillar and rest render are going to cost us $2000 + $900 = $2900, which is mentioned on tender-6.

Abhishek had asked this question by mail on 15th August 2013 @ 8.22am and you replied back in that regard on 23rd August at 5.10pm saying that “the price for $900 render to front is correct and noted in your render.”

If the cost is going to be $5900 then we would stick with the option we chose at first which is full rendering with two different colors as per color appointment. We won’t have tiling option on pillar.

Laundry option-5 (HPG05060) with single broom cupboard (no charge), we asked at color appointment and it is mentioned in the picture I sent you today as well. The price you have given us is for Option-5A

Abhishek had inquired about laundry option by mail on 26th August 2013 at 9.47am and you replied back on 6th September 2013 at 10:45am saying that: “laundry option-5 is in your tender document, the broom cupboard is no charge however it is an upgrade to select laundry option 5”

My apology but these are the things we had already inquired and got misunderstood.

We are making our dream home and we have our budget to go with. Such situations upset us.

We are been blamed for delaying contract process. After having look to all emails and conversations, I hope you will understand who is delaying this process. We want to have things very clear, not asking for same things again and again and waste your and our time. We just want things clear and smooth, nothing else. We have never paid late or delayed in providing any documents.

There is nothing personal.

Our first home is built by Henley and we are really very happy with it. That’s the reason, we are back with Henley (Mainview).

We are quite upset with the things happening at this moment. I would like to post pond our appointment to 2nd November if that’s alright with you.

Regards

Priyanka & Abhishek Mistry

46 On 16 October 2013, Mr Charlesworth emailed Mrs Mistry a copy of an authorised tender, described as “Tender 8” (the October tender). The October tender provided for the Amalfi AM532 Eclipse “part render” façade, which was the same façade and render option stipulated in the September tender. The October tender showed that the laundry option would cost $610 and that the additional broom cupboard would be free of charge. The total cost of the house under the October tender was $253,982.96.

47 Soon after Mr Charlesworth provided the October tender, Mrs Mistry responded to Mr Charlesworth explaining that she would discuss this tender with Mr Mistry and let Mr Charlesworth know about render options and a contract signing date. Mrs Mistry also noted that the October tender did not include provision for a fly screen as apparently previously requested by Mr Mistry. Mr Charlesworth responded: “I will look into this and have this item [ie the fly screen] added to your tender document. Once you have confirmed your render options I will finalise the tender for you”. The Mistrys did not respond to Mr Charlesworth’s email and made no contact with Henley Arch until late November 2013.

48 The Mistrys’ state of mind as at 16 October 2013 was a major point of contention at trial. Henley Arch contended that at this point in time, the Mistrys showed no unwillingness to continue with Henley Arch and that the only outstanding issue was the Mistrys’ selection of render options. Contrastingly, Mr Mistry contended that at this time, he and his wife had decided not to further engage with Henley Arch and explained his state of mind in the following terms:

I was so disturbed at the time because the things was going on for five months and I had – like, I was – mentally, I was not prepared to talk about those things again because it was just a, like, nightmare kind of thing, like, you know, for five months, so I said – even though he’s giving us everything, but I don’t want to go ahead because I was so frustrated under my financial burden that I couldn’t go ahead with that at all. Yes. That’s what I said to [Mrs Mistry]. And like, because we building our dream home, like, you know, I was – if – I was not ready. She said, “You want to go ahead?” and then we decided we don’t want to go ahead. That’s it.

49 Generally, the Mistrys gave evidence before me that they were very unhappy with Henley Arch’s behaviour in terms of the constant changes, delays and the failure to incorporate their changes in the various tender versions and that it was for that reason that on or around 16 October 2013 they decided not to proceed further with Henley Arch. I must say that I found their evidence concerning their state of mind and motivations at this time to be unreliable if not confected. I will elaborate on this aspect later, but I would at this stage make the following observations.

50 The Mistrys criticised Henley Arch regarding the number of tender versions created over the period of Henley Arch’s engagement. In evidence, Ms Belinda Jane Findlay, General Counsel of Henley Arch, noted that the number in this instance was more than usual. The evidence of Mr Milan Veljanovski, Business Operations Estimating Leader of Henley Arch, was that a normal number of tender documents was somewhere between three and five. The final tender produced for the Mistrys was labelled version “8”. Mr Veljanovski explained the process by which a new tender was produced in the following terms:

So there is a tender presentation, which is based on tender document 1. That usually happens between our tender presenters and a client. From there any changes made on the day automatically goes to a tender document number 2. So tender document number 2, client signs, they pay a deposit and then it’s the next stage. So from there to contract signing there is a four, six week period where a client can actually make amendments to the actual tender. So if that is the case, obviously via email, phone, whatever it may be, those additions are then added in and we have a new tender document.

51 There was evidence of many email exchanges between the Mistrys and Henley Arch regarding amendments or changes requested by the Mistrys. There were also detailed meetings between the parties. Given this evidence, the number of tender versions in this instance was unsurprising. I do not see any objective basis to support the Mistrys’ criticisms of Henley Arch’s conduct.

52 Let me continue with the chronology of the communications between Henley Arch and the Mistrys. On 19 November 2013, Mr Charlesworth emailed Mrs Mistry and stated: “I am yet to receive a response from you regarding your contracts, and also confirmation on your render option presented to you. Can you kindly confirm with me what you would like to do?” The Mistrys did not respond to this email.

53 On 27 November 2013, Mr Charlesworth again followed up with Mrs Mistry and said “I am yet to hear from you regarding your intentions in building with MainVue. Can you please call or respond to my email at your earliest convenience?”

54 On 28 November 2013, Mr Mistry replied to Mr Charlesworth and said “we have decided not to go ahead with MainVue for our next home”. This was the first time the Mistrys had indicated to Henley Arch that they no longer wished to continue with their engagement with Henley Arch. It was also the first communication between the parties since 16 October 2013.

The Mistrys’ engagement of Lucky Homes

55 In mid-October 2013, a friend of Mr Mistry and a former client of Lucky Homes, Asif Iliyas, introduced Mr Shafiq to the Mistrys. On 19 October 2013, the Mistrys had a meeting with Mr Shafiq at the offices of Lucky Homes where the Mistrys apparently informed him that they were experiencing difficulties with Henley Arch. The Mistrys told Mr Shafiq that their difficulties with Henley Arch related to the payment of the deposit monies. At this meeting and unbeknown to Henley Arch, the Mistrys provided a copy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan to Mr Shafiq. It appears that this floorplan dated 9 May 2013 was obtained by the Mistrys at their visit to the MainVue office at Williams Landing in early May 2013. The Mistrys did not provide Henley Arch’s custom-designed floorplan, being the version of the Amalfi AM532 Eclipse floorplan which had been sent to the Mistrys on 22 July 2013, which I have previously referred to as the Mistrys specific floorplan.

56 What exactly occurred at the 19 October 2013 meeting is a key question as between the respondents at least. Indeed, what precisely occurred at this meeting is also relevant to aspects of Henley Arch’s claims as against all respondents.

57 Some of the facts as to what occurred at the 19 October 2013 meeting are not contentious. The Mistrys provided Mr Shafiq with a hardcopy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. That document, which was dated 9 May 2013, included a title block which set out the design name, Amalfi AM532, made reference to “MainVue” and contained Henley Arch’s copyright notice. A version of this is annexure A to these reasons. The Mistrys and Mr Shafiq sat around a table for 45 minutes to an hour and discussed amendments to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan that the Mistrys wanted. Mr Shafiq annotated the plan accordingly, including with coloured highlighting. The Mistrys instructed him to take steps preliminary to building a house on the Circus Avenue property in accordance with the Amalfi Avenue floorplan with the requested amendments they had discussed. But there were significant matters of difference as to what occurred.

58 The Mistrys said that at the 19 October 2013 meeting, they provided Mr Shafiq with an A4-sized hardcopy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. The Mistrys contended that the document provided to Mr Shafiq was in its “original state”, and retained references to the design name (Amalfi AM532), and Henley Arch. Mr Shafiq and Lucky Homes said that at the 19 October 2013 meeting, the Mistrys had provided an A3-sized hardcopy floorplan. Mr Shafiq said that he had photocopied the A3-sized floorplan and reduced it to an A4-sized copy. He said that the Mistrys and him then sat around a table for 45 minutes to an hour and discussed amendments to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan that the Mistrys wanted. Mr Shafiq annotated the A4-sized plan accordingly, including with coloured highlighting.

59 Mr Shafiq said that after all the annotations had been made to the plan, he then photocopied it and enlarged it to A3-size, but copied in black and white. According to Mr Shafiq, he or his staff could have done the photocopying, but later accepted that it was probably more likely that he did the photocopying.

60 Mr Shafiq originally gave evidence that the floorplan provided by the Mistrys did not include a title block which set out the design name and reference to the author or any other distinguishing feature or statement indicating who had prepared that design. However, at trial, Mr Shafiq accepted that the document the Mistrys provided to him did include a title block, and that he saw the name “MainVue” and the copyright notice at the bottom of the plan. Mr Mistry gave evidence that he did not recall whether the title block was removed from the document on which annotations and coloured highlighting were being made.

61 The Mistrys said that they had instructed Mr Shafiq to use the Amalfi Avenue floorplan as an “example” to allow Lucky Homes / Mr Shafiq to prepare a new plan. Mr Shafiq said that the Mistrys had instructed him to build a house on the Circus Avenue property in accordance with that floorplan and no other design. Mr Shafiq explained that he had felt a “bit uncomfortable” that the Mistrys were pushing him to use the Amalfi Avenue floorplan but Mrs Mistry had told him that the plan had “their own ideas and stuff”. The Mistrys said that they sought confirmation from Mr Shafiq that he could make the necessary alterations to the floorplan so that the Mistrys’ house could be built up to a certain price. Mr Shafiq said that he could build the house for $250,000 if there were no further amendments sought after that meeting with him. Mr Shafiq asserted that the Mistrys had instructed him not to prepare a new design from scratch, but instead to engage a draftsperson to make amendments to the floorplan that they had provided to him.

62 The Mistrys said that prior to the 19 October 2013 meeting they were unaware about copyright questions arising in relation to the use of Henley Arch’s floorplans. Mr Mistry said that when they gave Mr Shafiq the floorplan, Mr Shafiq “mentioned there might be a problem, and we ask him what might be the problem and he said the copyright”. Mr Mistry said that he and his wife “were shocked that there might be a possibility” and that they said to Mr Shafiq that they didn’t “want to go ahead if there is any problem”. Lucky Homes and Mr Shafiq agree that Mr Shafiq said to the Mistrys that using the Amalfi Avenue floorplan would “not be a problem” because if they “made 15 to 20 changes” to the original design there would not be a copyright issue. But Mr Shafiq said that he told the Mistrys that the changes must be “substantial”. Mr Mistry could not recall the word “substantial” being used and said that he was told the changes need only be “slight”. I will return to this issue and discuss it in more detail later.

63 Mr Shafiq also said that he asked the Mistrys about the origins of the plan provided to him. He asserted that the Mistrys told him that they had “paid $3000 for these plans” and that “[t]hese are our plans”. Mr Shafiq asserted that he did not consider copyright to be in issue because the Mistrys had “emphatically” stated to him that they had paid for and owned the floorplan or that they had a licence to use it. The Mistrys rejected the assertion that they had told Mr Shafiq that they had paid Henley Arch $3000, had owned the floorplan or had a licence to use it.

64 I will return to the detail of these competing versions and their resolution after I have made observations concerning the reliability or otherwise of the evidence given by the Mistrys and Mr Shafiq.

65 After Mr Shafiq made annotations to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan with the title block absent, which showed the intended variations to the floorplan of the Mistrys’ house (the Shafiq modified floorplan), he required that the Mistrys pay an initial deposit of $1,000 (GST inclusive) to start the procedure for the “design of the house and stuff”. Lucky Homes issued an invoice for that deposit on or around 19 October 2013. The payment was received by electronic funds transfer on 21 October 2013.

Lucky Homes’ engagement of BN Design

66 Lejla Izic is the sole director and shareholder of BN Developments Pty Ltd, which trades as BN Design. BN Design operates a business involved in drafting architecture plans. Ms Izic is a draftsperson at BN Design.

67 Since 2010, BN Design has worked with Lucky Homes on approximately 40 to 50 separate occasions for the design of homes which Lucky Homes had been engaged by homeowners to design and construct. Usually, BN Design prepared a design for the house, being the floorplan and the elevation. This design was usually based on one of BN Design’s pre-drawn house designs and adjusted according to the homeowner’s specific requirements. Ms Izic had been closely involved in and was the chief designer of many of the floorplans and elevations that Lucky Homes had published on its website. BN Design’s main point of contact with Lucky Homes had been Mr Shafiq.

68 On 21 October 2013, Mr Shafiq attended the offices of BN Design. At that meeting, Mr Shafiq provided the A3-sized Shafiq modified floorplan to Ms Izic and instructed her to prepare new drawings based on that floorplan. Ms Izic recalled that the floorplan provided to her had some handwritten annotations with coloured highlighting on it.

69 Ms Izic described the Shafiq modified floorplan as a “pre-drawn, seemingly professionally drawn, floorplan”. When Mr Shafiq provided the plan to Ms Izic, he said that the homeowners had paid “someone” to create the plan, but the homeowners considered that they had been charged too much so decided to find another draftsperson. According to Ms Izic, at no point did Mr Shafiq tell her who the previous draftsperson was or how much the Mistrys had paid for the floorplan.

70 Ms Izic asserted that she did not know, at the time of BN Design’s engagement with Lucky Homes, the name of the owner of the Circus Avenue property. She said that Mr Shafiq did not then mention the homeowner by name.

71 Ms Izic said that she was at first sceptical of the provenance of the Shafiq modified floorplan, but accepted Mr Shafiq’s assertions that the floorplan was owned by the homeowners. Ms Izic also said:

I found it unusual that the floorplan Mr Shafiq brought to me had no title block. In my experience it is usual for professionally designed floorplans to have a title block as it is part of the template in standalone programs, such as ArchiCAD which I use.

I did not follow through with my usual process of insisting on written proof of the ownership of copyright in the floorplan. To the best of my recollection I would have neglected to insist on this step because of the otherwise good and long working relationship I had with Mr Shafiq on previous projects.

72 Ms Izic also recalled that this was the first time that Lucky Homes had provided her with another draftsperson’s plan of a home as a starting point. So far as she was aware, most of the other projects managed by Lucky Homes had been based on one of BN Design’s standard designs. Otherwise BN Design would develop a bespoke design based on a set of requirements from the homeowner.

73 At the 21 October 2013 meeting, Mr Shafiq and Ms Izic discussed the changes to the Shafiq modified floorplan based on Mr Shafiq’s instructions. Ms Izic made handwritten annotations to the Shafiq modified floorplan. At the conclusion of the meeting, Ms Izic (as she recalled) made a copy of the Shafiq modified floorplan she had annotated and gave the original back to Mr Shafiq. Mr Shafiq has denied that he was given or retained a copy of the Shafiq modified floorplan with her annotations (the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan). A copy of the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan is annexure D to these reasons; the Shafiq modified floorplan has been destroyed, as too the precise Amalfi Avenue floorplan that was provided by the Mistrys to Mr Shafiq on 19 October 2013.

74 Between 21 and 29 October 2013, in accordance with Mr Shafiq’s instructions, BN Design drafted a new floorplan for the Mistrys’ house by reference to the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan.

75 On 29 October 2013, BN Design sent to Mr Shafiq a draft floorplan prepared by BN Design.

76 On 19 November 2013, Mr Shafiq emailed the final floorplan prepared by BN Design to Mr Mistry (the BN Design floorplan). A copy of the BN Design floorplan is annexure E to these reasons.

77 Mr Mistry said that he first became aware that Mr Shafiq had provided the Shafiq modified floorplan to BN Design when Henley Arch’s solicitors sent him the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan. I must say that this assertion lacks credibility. Mr Mistry must have known that it was intended that Mr Shafiq would engage a draftsperson. Moreover, Mr Mistry is likely to have also known this when he received the BN Design floorplan on 19 November 2013; it would have been self-evident.

Construction of the house on the Circus Avenue property

78 On 19 November 2013, the Mistrys entered into a building contract with Lucky Homes for the construction of a house on the Circus Avenue property in accordance with the BN Design floorplan (the Building Contract).

79 Clauses 15.0 and 15.1 of the Building Contract provided as follows:

Copyright

15.0 If the Builder constructs the Building Works in accordance with Plans which may incorporate designs which are:

• supplied by the Owner;

• prepared under instruction from the Owner; or

• prepared from sketches supplied by the Owner,

then:

• the Owner warrants that the Owner has the right to use the design and Plans and that no breach of copyright is involved in constructing the Building Works in accordance with the Plans; and

• the Owner indemnifies the Builder in relation to any claim for breach of copyright.

15.1 A claim for breach of copyright brought against the Builder is a breach of this Contract by the Owner.

80 On 28 November 2013, as I have said, the Mistrys informed Henley Arch that they no longer wanted Henley Arch to build a house on the Circus Avenue property.

81 By July 2014, Lucky Homes had completed construction of the house which presently stands on the Circus Avenue property in accordance with the Building Contract. The house was built according to the BN Design floorplan.

CREDIBILITY OF WITNESSES

82 Generally, the witnesses called by Henley Arch (Ms Izic, Ms Findlay and Mr Veljanovski) gave reliable evidence and there were no substantial credit attacks, subject to one matter that I will discuss later concerning Ms Izic. Contrastingly, the evidence given by Mr Shafiq and the Mistrys was not reliable. It is appropriate at this point to make some general observations relevant to my assessment of their unreliability.

83 I did not find Mr Shafiq to be a reliable witness. There are a number of reasons for this including the following:

(a) First, he attempted to have Ms Izic agree at a meeting between them on 17 March 2015 to give incorrect evidence as to the genesis of the work between them as set out in [35] of her statutory declaration and as confirmed in her evidence in chief. Ms Izic was not directly challenged on this version of events. Mr Shafiq, when he gave evidence, belatedly sought to challenge this when cross-examined, but his attempt carried little weight with me. It is worth setting out Ms Izic’s version of events:

Later, on or about 17 March 2015, Mr Shafiq came to see me at my office and at that meeting said words to the effect that “you need to co-operate with us otherwise you will be in big trouble”. At the time, I understood Mr Shafiq’s reference to “us” to be a reference to both himself and the homeowner. Mr Shafiq asked me to agree that certain hand-drawn sketches were the beginning of our conversation and relationship in relation to the project. He said words to the effect “I want you to confirm this [the sketches] was the beginning of our relationship on this project” to which I replied “no, this is the plan you brought me” while handing him a copy of the floorplan he provided to me on 21 October 2013 and as shown in annexure A. He repeated to me words to the effect that “we need to co-operate together”. He said words to the effect that he “did not recall” having provided the floorplan in annexure A to me. I told him words to the effect of “please keep this copy if you like in case you have put your file in the bin”. Annexed and marked C is a copy of the floorplan I handed to Mr Shafiq that day, which I signed and dated, and my staff member, Andrew Boyle, also signed and dated. I considered Mr Shafiq’s behaviour to be quite “shifty”, and I was shocked by his attempt to convince me to accept that the beginning of this project was the two hand drawn sketches, rather than the floorplan supplied to me and shown in annexure A. Mr Shafiq also said words to the effect that “the homeowner is prepared to backdate these sketches and to say these sketches were the start of the project”. I did not retain any copies of the sketches.

(b) Second, in my view Mr Shafiq removed the title block from the floorplan the Mistrys gave to him on 19 October 2013, contrary to his affidavit evidence which suggested that the Mistrys had removed the title block (see his affidavits of both 18 December 2015 and 26 February 2016). The inference that I draw is that this was done by Mr Shafiq in order to avoid questions from Ms Izic. The fact that the copying was not perfect so as to leave a faint reference to part of a name and “Amalfi AM532” down the left hand side in very small print does not substantially affect the drawing of this conclusion. All that it indicates is that Mr Shafiq was sloppy in doing the copying to remove the title block. Further, in my view it was Mr Shafiq who took the Mistrys’ A4 sized copy of the floorplan and increased it to an A3 size and as part of this process removed the title block.

(c) Third, I do not accept his evidence that he did not retain at least a copy of the floorplan with his handwritten notations (ie the Shafiq modified floorplan) and that his only copy was given to Ms Izic. In my view, it is likely that he destroyed this version, perhaps to conceal the full extent of his involvement.

(d) Fourth, Mr Shafiq, through his lawyers, was not forthcoming or frank with a proper explanation of what occurred in his solicitors’ letter of 1 July 2015 in response to Henley Arch’s solicitors’ letter of 9 June 2015. Further, in his solicitors’ letter of 26 March 2015 in response to Henley Arch’s solicitors’ letter of 27 February 2015, Mr Shafiq denied any reproduction of Henley Arch’s copyright works, despite the fact that Ms Izic had provided to Mr Shafiq a copy of the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan on 17 March 2015.

(e) Fifth, many incorrect statements by way of denials were made by Mr Shafiq and Lucky Homes in their pleaded case, whether by way of defence or cross-claim. I can only assume that this was done on the instructions of Mr Shafiq. I will elaborate on this conduct later.

84 I found Mr Mistry to be an even less reliable witness:

(a) First, I thought his evidence to be confected as to the Mistrys’ purported reason as to why they did not proceed with Henley Arch. His assertions of substantial dissatisfaction with Henley Arch and the assertion that Henley Arch was responsible for substantial delays were not supported by the contemporaneous documentation. Mrs Mistry’s reinforcement of her husband’s evidence in this regard also lacked credibility. Further, Mr Mistry’s evidence that he had an unstable emotional state at that time because of Henley Arch’s behaviour is evidence that I treat with some caution. He does not seem to have taken time off work at the relevant time. Moreover, as I have said, Mr Mistry’s assertions concerning the objective behaviour of Henley Arch at the time were not consistent with other objective and contemporaneous material. His asserted emotional state, if he had it, was not sourced to any secure foundation relating to any behaviour of Henley Arch that could be the subject of any criticism.

(b) Second, Mr Mistry’s apparent lack of sophistication and understanding as to the differences between the “Avenue” design and the “Eclipse” design was not credible. He clearly understood the difference. After all, he had a Diploma in Mechanical Enginering from VIT in Bangalore, India together with a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Ballarat. Generally, I infer that the Mistrys proceeded with Lucky Homes because they thought they could get the “Avenue” design for their home (total package) but for the “Eclipse” design price (total package).

(c) Third, Mr Mistry’s evidence in proceedings before the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) to recover the deposit monies paid to Henley Arch was consistently self-serving and against the objective facts.

(d) Fourth, Mr Mistry was the source of instructions given to the Mistrys’ lawyers to respond to Henley Arch’s letters of demand. Many of the statements contained in such responses were incorrect or evasive.

(e) Generally, Mr Mistry’s evidence was self-serving and in most respects unreliable, even though given with apparent earnestness.

85 In relation to the evidence of Mrs Mistry, prior to trial she had not made any affidavit. During the trial, I gave leave for the Mistrys to file and to rely upon a late affidavit from her. She did little more than affirm Mr Mistry’s evidence. To the extent that Mr Mistry’s evidence was problematic, so too was her evidence to the extent that it adopted his evidence. I found her evidence to be no more reliable on contentious aspects than her husband’s evidence.

86 As I have indicated, I found the evidence of each of Mr Shafiq, Mr Mistry and Mrs Mistry to be quite unreliable. That has not presented any serious forensic difficulty where such evidence can be compared and contrasted with the contemporaneous documents or other witnesses. But in relation to what occurred at the meeting on 19 October 2013 between these individuals, I only have their unsatisfactory and competing versions. Accordingly, each such version can only be assessed against the probable scenario to be gleaned from the context and which best rationally fits with all the evidence and the likely inferences that I can draw therefrom.

87 Finally, I should note that it was suggested by the respondents that Ms Izic’s evidence was somehow tainted because she had an incentive to give evidence in favour of Henley Arch in order to avoid being the subject of proceedings for copyright infringement. The respondents went so far as to suggest that her evidence had been coerced. I reject that latter suggestion, although I do accept that she had some interest in giving evidence which assisted Henley Arch. Nevertheless in my view she gave cogent and straightforward evidence that was consistent with the contemporaneous documents and the probable scenario as to what occurred. Moreover, much of her evidence was not challenged in cross-examination, including [35] of her statutory declaration.

SPECIFIC FACTUAL TOPICS

(a) Meeting between the Mistrys and Mr Shafiq – 19 October 2013

88 There was a change in tone in the communications between the Mistrys and Henley Arch on 15 October 2013. Prior to that date, the Mistrys had urged for a date to sign the contract with Henley Arch. However, at this point they sought to postpone the contract signing date. The likely explanation is the following.

89 In mid-October 2013, a friend of Mr Mistry and a former client of Lucky Homes, Asif Iliyas introduced Mr Shafiq and the Mistrys. In the week prior to the meeting of 19 October 2013, Mr Shafiq and the Mistrys spoke on the phone to organise a meeting. It was around this time (ie 15 October 2013) that the Mistrys sought to postpone the contract signing date with Henley Arch. The meeting was organised for 19 October 2013. At that meeting, the Mistrys decided to proceed with Mr Shafiq.

90 At the meeting on 19 October 2013, in addition to Mr Shafiq and the Mistrys being present, Asif Iliyas also attended. Henley Arch has contended that Mr Iliyas would have been able to give evidence on what occurred at the meeting and that I should draw a Jones v Dunkel inference that his evidence would not have assisted the Mistrys (as their friend) and also Mr Shafiq and Lucky Homes (as a former client). I do not propose to draw any such inference as I am not satisfied that the basis for drawing such an inference has been made out. In any event, insofar as any contest between the respondents inter se is concerned, the drawing of any such inference would be of no forensic assistance in resolving the competing versions of what occurred as between them.

91 The Mistrys brought a copy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan to the meeting in A4 size. Mr Shafiq, despite originally denying that the plan had the title block on it and giving evidence that it did not, changed his evidence at trial to accept that it did have the title block on it and that he had seen the name “MainVue” and the copyright notice on the bottom of the plan.

92 Mr Shafiq said that the Mistrys had told him that they had paid $3,000 for the plan they showed him and that “These are our plans”. But the Mistrys reject that they had said this. They also said that they never told Mr Shafiq that the floorplan was theirs or that they had a licence to use it. In my view, the Mistrys are likely to have mentioned that they had paid a deposit of $3000 to Henley Arch, but not that they owned the Amalfi Avenue floorplan or had any licence to use it. I say this because if they had said the latter to Mr Shafiq, it is unlikely that there would have then been the need for the “15 to 20 changes” discussion as I elaborate on later.

93 Mr Shafiq said that the Mistrys made it clear that they wanted a house according to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan and no other design. Mr Shafiq said that it was Mrs Mistry who was pushing for the house to be built according to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan with “their own ideas and stuff”. I accept Mr Shafiq’s evidence on this aspect. Mrs Mistry liked and wanted to proceed with the Amalfi home. Contrastingly, the Mistrys said that they told Mr Shafiq that the plan was simply an example of what they wanted. But in my view this is not credible given their undoubted desire to have the Amalfi home which was their “dream home”.

94 In my view, the Mistrys gave Mr Shafiq the Amalfi Avenue floorplan requesting that Mr Shafiq provide them the Amalfi AM532 house but with the more expensive Avenue façade rather than the Eclipse façade. This was denied by Mr and Mrs Mistry, but that is the most probable explanation for providing the Amalfi Avenue floorplan to Mr Shafiq rather than the Mistrys specific floorplan. If otherwise, it is odd that a plan that they were provided in May 2013 was handed over at the meeting rather than the more recent plans provided by Henley Arch on 22 July 2013. In my view, Mrs Mistry’s evidence that she did not care about the front of the home is not credible. The resulting façade looked similar to the MainVue display homes they had visited, and importantly with the Avenue façade.

95 Mr Shafiq accepted that at the time he was given the Amalfi Avenue floorplan at the 19 October 2013 meeting he was aware that Henley Arch was one of Australia’s largest home builders and that it was also plain to him that Henley Arch claimed copyright in the plan. He was also aware that clients often told a lot of stories and he didn’t believe what they said. Moreover, even on his own version of events as to what the Mistrys told him, he accepted that he had a doubt about whether they truly owned the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. He also accepted that he could have called Henley Arch to verify any assertion of the Mistrys that such a plan was theirs and thereby avoid any copyright problems, but did not do so. He also accepted that he did not ask the Mistrys to provide a document which verified any assertion that they owned the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. He accepted that this would have been easy to do.

96 In my view, and notwithstanding Mr Shafiq’s denial, it is likely that the reason Mr Shafiq did not contact Henley Arch was because he did not want Henley Arch to know that he was intending to use one of their plans. Moreover, the denial is inconsistent with his subsequent conduct in seeking to hide his use of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan.

97 Mr Shafiq said that he told the Mistrys that copyright would not be an issue if they made 15 to 20 alterations to the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. In oral evidence, he said that he had told them that the changes must be “substantial”. Mr Mistry could not recall that word being used and in his affidavit said that he was told the changes need only be “slight”. In my view, the addition of the word “substantial” to Mr Shafiq’s evidence is a convenient addition to his evidence and I do not accept it. I will discuss this issue again later when dealing with the cross-claims.

98 The Mistrys gave evidence that prior to the meeting they were unaware about copyright issues dealing with the use of project home floorplans. Mr Mistry said that when they gave Mr Shafiq the Amalfi Avenue floorplan, Mr Shafiq “mentioned there might be a problem, and we ask him what might be the problem and he said the copyright. … We were shocked that there might be a possibility and we said, like ‘We don’t want to go ahead if there is any problem’”.

99 Mr Mistry accepted that if he was so “shocked”, it would have been reasonable to call a solicitor to check whether Mr Shafiq’s advice was correct, though he said that he simply relied on Mr Shafiq’s advice. Mr Mistry also accepted that it would have been easy to write to Henley Arch to check whether Henley Arch had a problem with what they proposed to do, and that it would have been reasonable to write to Henley Arch in circumstances where he was “shocked” about the copyright issue. At the least, the Mistrys were put on notice of a copyright issue.

100 As to Mr Shafiq, he was not a lawyer but had received some instruction from Victoria University about copyright applying to building plans. He understood as at October 2013 that building plans were subject to copyright and that without permission of the copyright owner one was not allowed to build a house incorporating those plans.

101 It is not credible that Mr Shafiq believed that he could overcome copyright by simply making 15 to 20 alterations to the plan. Moreover, Mr Shafiq accepted that, even with 15 to 20 “substantial changes” he should not have gone ahead without having called Henley Arch. He also accepted that he should have called a solicitor to advise him about whether the assertion by the Mistrys that they owned copyright (if it had been said at all) was correct and whether he was correct to say that making 15 to 20 changes to a plan would avoid copyright infringement. But he did not do so.

102 Mr Mistry gave evidence that the Amalfi Avenue floorplan that the Mistrys provided to Mr Shafiq on 19 October 2013 was in A4 size. Mrs Mistry provided similar evidence. Contrastingly, Mr Shafiq gave evidence that the Mistrys gave him an A3 size.

103 In my view, the Mistrys provided Mr Shafiq with an A4 sized copy of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan and Mr Shafiq photocopied the plan in A3 size, deliberately removing the title block including the identifying marks for MainVue and the copyright notice. Mr Shafiq rejects this and said that he received an A3 plan and made an A4 copy of the plan. But I do not see why the Mistrys would have taken the A4 size and copied it first to A3 size before giving it to Mr Shafiq. That seems unlikely. When asked whether he made the copy personally, Mr Shafiq said he or his staff, then accepted that it was probably more likely that he did the photocopying. It is unlikely that a staff member did this. Mr Shafiq’s evidence was that he employed only one contractor who worked as a site manager on work sites. Furthermore, it is doubtful that such a person would have attended his office on a Saturday, let alone done the photocopying of the plan and then removed the title block.

104 In my view, it is unlikely that the title block was removed accidentally. The more likely explanation was that it was done deliberately and by Mr Shafiq. The title block could not have been accidentally removed from one side of the plan without either other parts of the plan also being cut off (eg if the reduction to A4 had been performed with the copy set at less than 100%, then the image would have been cropped equally around all sides rather than on one side alone) or the copied plan not being centred in the page (eg if the title block had been off the copier glass, the copied image would have the bottom edge of the plan much closer to the edge of the page and more white space across the top). The plausible ways that the title block could have been photocopied off the page, regardless of whether any reduction or increase in the size of the copy was made, was to mask the title block or to photocopy it twice, the first time with the page low on the photocopier to remove the title block and then photocopying the resulting page high in order to shift the plan back into a central position. The first method would involve a deliberate removal of the title block. Further, the probability that the second method was unintentional is low. Generally, no plausible explanation was put forward by Mr Shafiq to explain the removal of the title block. He had a clear motive to remove the title block, namely to reduce the chance of Henley Arch discovering that its plan had been misused or to ensure that Ms Izic did not make further enquiry or at least minimise that risk.

105 In my view, Mr Shafiq’s evidence that he made an A4 copy of the plan, worked on that in colour, and then enlarged it to A3 again in black & white, is contrived to provide an explanation for how the title block could have come to be “accidentally” removed from the plan. Mr Shafiq could not produce the A4 plan with colour markings on it, and claimed that he “threw it away”. In my view, the A4 plan with colour markings never existed. Only the A3 plan with colour markings existed.

106 As to how the colour markings were made, Mr Shafiq sat around the table with the Mistrys for 45 minutes or so taking instructions from the Mistrys and annotating the plan accordingly, including with colour highlighting. Moreover, Mr Mistry paid attention while Mr Shafiq was doing this to the plan. Even if the removal of the title block had been unintentional, it would not have been unknown to each of the persons sitting around the table that the title block had been removed.

(b) Meeting between Mr Shafiq and Ms Izic – 21 October 2013

107 On 21 October 2013, and as I have said, Mr Shafiq met with Ms Izic of BN Design. Ms Izic had attended to approximately forty to fifty drafting jobs for Mr Shafiq and this was the first time that Mr Shafiq had brought to her to be used another draftsperson’s plan of a house as a starting point.

108 In my view, Mr Shafiq brought to the meeting with Ms Izic the A3 sized Shafiq modified floorplan. Mr Shafiq initially accepted this, but then suggested it might not have been in colour, then finally said he did not remember. But he did accept that he gave Ms Izic an A3 copy.

109 Ms Izic recalled that Mr Shafiq told her that the floorplan was the homeowner’s property, having paid someone money to create the design, but that the person had been charged too much. I will return to this later when discussing the cross-claims. Mr Shafiq insisted that the floorplan was what the homeowner wanted and should not be amended by her to better suit the orientation on the land.

110 Ms Izic told Mr Shafiq that he should make sure that the owner was certain that the plan was their property. Mr Shafiq gave evidence that Ms Izic knew that the plan was a MainVue plan, because he mentioned it to her. However, that proposition was not put to Ms Izic and is inconsistent with her evidence. I reject his assertion.

111 At the meeting with Mr Shafiq, Ms Izic made amendments to the Shafiq modified floorplan based on discussions with Mr Shafiq and his directions based on his annotations on the plan. I have set out the detail later in these reasons as to Mr Shafiq’s annotations and Ms Izic’s amendments as reflected on the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan.

112 At the conclusion of the meeting, Ms Izic made a copy of the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan and gave the original back to Mr Shafiq. Mr Shafiq denies this, but I accept Ms Izic’s evidence on this point. It would be highly unusual for a builder not to retain such drawings. It is likely that Mr Shafiq destroyed the Shafiq/Izic annotated floorplan upon being notified of Henley Arch’s concerns so that it could not be used as evidence against him.

(c) The Mistrys’ application to VCAT – mid-2014

113 The Mistrys made an application to VCAT in mid-2014 for the return of the deposit paid to Henley Arch. Henley Arch disputed the refund claim, apart from a small sum that was not the subject of fees incurred in respect of third party services. The refund claim is inconsistent with the idea that the Mistrys paid the deposit to Henley Arch as consideration for the ownership or use of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan. Had the Mistrys believed that they had purchased the floorplan, they would not have believed that they were entitled to recover the entirety of the deposit. The Mistrys at this time (ie mid-2014) asserted that they had received no valuable goods or services from Henley Arch. The Mistrys knew that they did not own and had no licence to use the Amalfi Avenue floorplan or indeed any other of Henley Arch’s plans.

114 At the VCAT hearing on 9 September 2014, Mr Mistry in sworn evidence provided several different versions of when the Mistrys had first met and contracted with Lucky Homes for the construction of the Circus Avenue house. He first said that they had engaged Lucky Homes in March 2014. This was incorrect. The VCAT Member then asked, “When did you approach this builder?” To which Mr Mistry responded, “After I signed – after I cancelled…”, that is, after he cancelled with Henley Arch on 28 November 2013. That evidence was also incorrect. Mr Mistry then went on to say “I just started talking with them, but I didn’t sign anything until the 2014”. That was also incorrect. After being reminded by the Member that the plans for the Circus Avenue house were dated November 2013, Mr Mistry again insisted that he and his wife had not started talking with Lucky Homes until November 2013. That evidence was also incorrect. After further questioning, Mr Mistry agreed that they went to see the builder a “week before” they cancelled with Henley Arch, that is, a week before 28 November 2013. That evidence was inaccurate as well.

115 At no stage at that time did Mr Mistry frankly reveal that the first contact he had with Mr Shafiq was in mid-October 2013, nor did he reveal that a building contract had been signed on 19 November 2013. When it was put to Mr Mistry at the trial before me that he had made false statements to VCAT, he was less than forthcoming, saying that he could not remember the dates. I might say that at the time of giving his VCAT evidence the relevant events were less than a year old. Moreover, all the so-called imperfections of memory were all to his advantage and self-serving. He also refused to accept that he had made any false statements at the VCAT hearing.

116 Further, at the VCAT hearing, Mr Mistry insisted that he had “never seen” Henley Arch’s Step by Step Guide, despite the fact that he had referred to it in an email to Henley Arch. When this matter was put to him at trial, he continued to insist that he had not been provided with the Step by Step Guide. Contrary to this evidence given both to VCAT and myself, Mr Mistry’s email dated 16 September 2013 to Mr Charlesworth demonstrated that he had received and read the Step by Step guide. He referred to the detail of its terms: “so far what you have given me I am happy with it. So I can sign the contract on that but as per your Step by Step procedure we need to give you 3% of the contract price and also bank letter.”

117 Further, Mr Mistry misrepresented the nature of his dealings with Henley Arch to the Member. The Member asked, “so was a building contract ever signed?” Mr Mistry responded, “No. Because we [were] never provided any final tender documents after four months of wait”. That latter evidence was untrue. The Member then asked, “Did you have no dealings with them between 16 October and 27 November?” to which Mr Mistry responded “That’s correct. They didn’t bother even send me or call me”. That evidence was misleading.

118 In my view, Mr Mistry’s evidence before VCAT was less than frank, if not false. It was entirely self-serving and unreliable. Moreover, it is inconsistent with the suggestion that the Mistrys thought they were entitled to use the relevant floorplan. Further, it in part is inconsistent with the “innocent infringement” defence and is also relevant to my consideration of the additional damages question.

(d) Henley Arch’s letters of demand

119 On 26 November 2014, Henley Arch’s lawyers, Ashurst Australia, sent a letter of demand to the Mistrys. The Mistrys, acting together with Mr Shafiq, instructed the Mistrys’ then lawyers, Saundh, Singh & Smith Lawyers (SSSL), to inform Henley Arch by letter on 14 January 2015 that no use had ever been made of the Amalfi Avenue floorplan and that the plan had not been provided to Lucky Homes or Mr Shafiq. This statement was repeated in correspondence from the same lawyers on 5 March 2015.