FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 4) [2016] FCA 1174

File number: | QUD 536 of 2013 |

Judge: | GREENWOOD J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – consideration of contended contraventions of ss 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 121 and 123 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) CONSUMER LAW – consideration of contended contraventions of ss 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) CONSUMER LAW – consideration of contended contraventions of s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) CONSUMER LAW – consideration of contended contraventions of s 76 of the National Credit Code, Schedule 1 to the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) |

Legislation: | National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth), ss 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 121, 123, 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 National Consumer Credit Protection (Transitional and Consequential Provisions) Act 2009 (Cth), ss 167 and 169, Schedule 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), ss 12CB, 12CC Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 36 |

Cases cited: | Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (2016) 90 ALJR 835; [2016] HCA 28 Maxwell v Murphy (1957) 96 CLR 261 Jones v Dunkell (1959) 101 CLR 298 Hamilton v Whitehead (1988) 166 CLR 121; (1989) 7 ACLC 34 Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 Re Waterfront Investments Group Pty Ltd (in liq) (2015) 105 ACSR 280; [2015] NSWSC 18 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SensaSlim Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 5) (2014) 98 ACSR 347. |

Date of last submissions: | 10 April 2015 |

Registry: | Queensland |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | 1850 |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Mr H Copley, Australian Securities and Investments Commission |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Dr R Spence |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Dr R Spence, Integrity Criminal Legal |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | CHANNIC PTY LTD (ACN 141 145 753) (and others named in the Schedule) First Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant is directed to submit to the Court within 14 days proposed declarations and orders to be made in conformity with the findings in the reasons for judgment published today.

2. The costs of and incidental to the proceeding are reserved for later determination.

3. The parties are directed to file submissions in relation to the costs of the proceedings within 21 days.

4. The question of the determination of a pecuniary penalty in respect of the various contraventions is to be determined in a separate proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GREENWOOD J:

PART 1: The Statutory Background

1 In 2009, the Commonwealth Parliament enacted the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (the “NCCP Act”). Schedule 1 to the NCCP Act is the National Credit Code.

2 Sections 3 to 337 of the NCCP Act (essentially the entirety of the NCCP Act) and the National Credit Code (having effect as a law of the Commonwealth; s 3, NCCP Act) commenced on 1 April 2010 (by Proclamation), subject to transitional arrangements contained in the National Consumer Credit Protection (Transitional and Consequential Provisions) Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Transitional Provisions Act”).

3 Prior to the enactment of the NCCP Act and the Transitional Provisions Act, the States and Territories had made provision for, put simply, a statutory regime for the regulation of transactions and arrangements concerning the provision of credit or advice about credit, to consumers, described in s 4(1) of the Transitional Provisions Act, as the “old Credit Code”. The object of Schedule 1 of the Transitional Provisions Act is to provide a “smooth transition” from the old Credit Code “of a referring State or Territory” to the new National Credit Code under the NCCP Act whilst accommodating the principles set out at Item 2(1)(a) and (b) of Schedule 1 of the Transitional Provisions Act.

4 That transition was effected by Schedule 1 to the Transitional Provisions Act. Relevantly for present purposes, Items 1 to 21 of Schedule 1 commenced on 1 April 2010. Item 19 of Schedule 1 provides that Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act, which addresses the topic of “responsible lending conduct” applies on and after 1 January 2011 being a date described as the “Chapter 3 start date” (rather than 1 April 2010). Notwithstanding the Chapter 3 start date of 1 January 2011, Item 19(2) of Schedule 1 provides that 31 sections of Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act apply in relation to particular conduct in the period commencing on 1 July 2010 and ending on 1 January 2011 (when Chapter 3 generally starts).

5 Thus, the relevant interim transitional period is 1 July 2010 to 1 January 2011.

6 Relevantly for present purposes, ss 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 of Chapter 3 applied from 1 July 2010 in relation to particular conduct and so too ss 115, 116, 117, 118 and 123 of Chapter 3 from 1 July 2010.

7 Sections 113, 114 and 121 apply from 1 January 2011.

8 Chapter 2 of the NCCP Act casts an obligation on all persons who engage in “credit activities” to be licensed under the NCCP Act and in general a person cannot engage in a credit activity if the person does not hold an “Australian credit licence” within the meaning of s 35 of the NCCP Act.

9 Schedule 2 to the Transitional Provisions Act addresses the topics of “transitional authorisation” of persons to engage in credit activities and “prohibitions” upon engaging in credit activities in the period 1 July 2010 to 31 December 2010 and also from 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2011. Part 3 of Schedule 2 addresses the topic of “registration” of persons who engage in credit activities and the application process for registration in the period 1 April 2010 to 30 June 2010 (among other matters).

10 Item 36(2) of Schedule 2 provides that ss 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 of the NCCP Act apply to a “registered person” during the period 1 July 2010 to 1 January 2011 as if all references to a licensee in those provisions were references to a registered person or a licensee and, on the same footing, ss 115, 116, 117, 118 and 123 apply in the same period to a registered person.

11 Sections 113, 114 and 121 apply from 1 January 2011.

12 It is now necessary to say something about these provisions, in context, as they applied at the time of the conduct in issue.

13 The NCCP Act was introduced to prescribe conduct of relevant participants where: “credit products in the market has made it much less straightforward for consumers to determine whether a product is suitable for their needs and [has] increased their dependence on intermediaries” and “[a]s a result there are considerable information asymmetries that justify regulatory intervention”: Revised Explanatory Memorandum for the National Consumer Credit Protection Bill 2009 (the “REM”), p 28.

14 As to the obligations cast upon credit providers by the NCCP Act, the REM for the Bill at [3.25] says this:

The primary obligations in relation to the provision of credit (for example, lending); or the provision of credit assistance (for example, suggesting a particular credit contract or assisting with a particular credit contract) are: to make an assessment that the loan is not unsuitable for the consumer; and to assess that the consumer has the capacity to meet the financial obligations under the contract without substantial hardship.

15 As already mentioned, Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act is concerned with the topic of “responsible lending conduct” and Part 3-2 applies to licensees who are credit providers. Section 128 provides that a licensee must not enter into a credit contract with consumer, who will be the debtor under that contract, on a day (called the “credit day”) unless the licensee has, within 90 days before the credit day: made an assessment that accords with s 129 and covers the period in which the credit day occurs; and made the inquiries and verification required by s 130. The words in italics represent the essential elements of the section.

16 A credit contract is a contract under which credit is or may be provided to which the National Credit Code applies: s 5, NCCP Act; ss 4 and 5, National Credit Code. It is uncontroversial in these proceedings that each loan contract as recited at [73] of these reasons is a credit contract. It is also uncontroversial that the borrower described at [73] of these reasons is a consumer: s 5, NCCP Act.

17 The assessment required by s 128 of the NCCP Act is an assessment that specifies the period the assessment covers and one that assesses whether the credit contract, if entered in that period, will be unsuitable for the consumer: s 129(a) and (b), NCCP Act.

18 As to the inquiries required by s 128, the licensee must do five things before making the assessment in accordance with s 129. Those five things, by s 130(1)(a) to (e) are:

(a) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; and

(b) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and,

(c) take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation; and

(d) make inquiries prescribed by the regulations about any matter prescribed by the regulations; and

(e) take any steps prescribed by the regulations to verify any matter prescribed by the regulations.

19 The assessment of whether the credit contract is unsuitable for the consumer is in some respects taken out of the hands of the licensee (or is, at least, the subject of additional statutory considerations) as s 131 provides that the licensee “must assess” the credit contract as unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time of assessment, it is likely, that, relevantly, the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract or could only comply with those obligations with substantial hardship (if the contract is entered in the period covered by the assessment); or the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if entered in the period covered by the assessment: s 131(2).

20 Section 131(4) sets out the only information to be taken into account for the purposes of s 131(2).

21 If the consumer requests a copy of the assessment before entering into the credit contract, the licensee must give a copy of it to the consumer before entering into the contract: s 132.

22 A credit contract with a consumer “is unsuitable” for the consumer if, at the time it is entered, relevantly: it is likely that the consumer will be unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under it or could only comply with those obligations with substantial hardship; or, the contract does not meet the consumer’s requirements or obligations: s 133(2). If, having regard to s 133(2), a credit contract is unsuitable for a consumer (who will be a debtor under it), the licensee must not enter into the contract: s 133(1).

23 In determining whether the credit contract is unsuitable under s 133(2), the only information to be taken into account is information that satisfies both of the following integers: (a) the information about the consumer’s financial situation, requirements or obligations; (b) the information the licensee had reason to believe was true or would have had reason to believe was true if the licensee had made the inquiries or verification under s 130: s 133(4).

24 Apart from obligations cast upon credit providers, Division 4 of Chapter 3 (Part 3-1) casts obligations upon credit assistance providers.

25 A person provides credit assistance to a consumer if, by dealing directly with the consumer (or his or her agent) “in the course of, as part of, or incidentally to”, a business carried on by the person (or another person), the person, relevantly: suggests that the consumer apply for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider (s 8(a), NCCP Act); or assists the consumer to apply for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider (s 8(d), NCCP Act)).

26 The obligations cast upon such a person are very similar to the obligations cast upon a credit provider.

27 By s 115(1) a licensee must not provide credit assistance to a consumer on a day (called the “assistance day”) by, relevantly, suggesting that the consumer apply, or assisting the consumer to apply, for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider (s 115(1)(a)) unless the licensee has within 90 days before the assistance day: made a preliminary assessment which accords with s 116(1) and which covers the period proposed for the entering of the contract (s 115(1)(c)); and made the inquiries and undertaken the verification in accordance with s 117 (s 115(1)(d)).

28 The preliminary assessment must specify the period the assessment covers (s 116(1)(a)) and assess whether the credit contract, if entered into, will be unsuitable for the consumer (s 116(1)(b)).

29 As to the inquiries and verification required by s 115(1)(d), the licensee must, before making the preliminary assessment do five things required by s 117(1) and they are:

(a) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; and

(b) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and

(c) take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation; and

(d) make inquiries prescribed by the regulations about any matter prescribed by the regulations; and

(e) take any steps prescribed by the regulations to verify any matter prescribed by the regulations.

30 The credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time of the preliminary assessment, it is likely that, relevantly: the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract or could only comply with them with substantial hardship (s 118(2)(a)); or the credit contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives (s 118(2)(b)), if, in either case, the contract is “entered in the period proposed for it to be entered”.

31 If the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer, by reason of the s 118(2) factors, the licensee “must”, for the purposes of the preliminary assessment under s 116(1), “assess that the contract will be unsuitable for the consumer”: s 118(1).

32 The credit contract also will be unsuitable for the consumer if at the time the licensee provides the credit assistance it is likely that, relevantly, first, the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract or could only comply with those obligations with substantial hardship, or, second, the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or obligations, if in either case, the contract is entered into in the period proposed for it to be entered: s 123(2)

33 Section 123(1) provides that a licensee must not provide credit assistance to a consumer by suggesting that the consumer apply, or by assisting the consumer to apply, for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider if the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer under s 123(2): s 123(1).

34 Sections 113, 114 and 121 of Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act commenced on 1 January 2011. Section 113(1) provides that a licensee must, as soon as practicable after it becomes apparent to the licensee that it is likely to provide credit assistance to a consumer in relation to a credit contract, give the consumer the licensee’s credit guide in accordance with s 113(2). Section 113(2) sets out approximately 16 matters the licensee’s credit guide must address.

35 Section 114 provides that a licensee must not provide credit assistance of the kind described, relevantly, at s 114(1)(a), unless the consumer has been given a quote in accordance with s 114(2), the consumer has signed and dated the quote or otherwise accepted it and has been given a copy of the “accepted quote”.

36 Section 121 provides that the licensee must at the same time as providing credit assistance to a consumer (by, relevantly, suggesting that the consumer apply, or by assisting the consumer to apply, for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider), give the consumer a credit proposal disclosure document that satisfies the mandatory requirements of s 121(2).

37 Section 76(1) of the National Credit Code provides, relevantly, that the Court may, if satisfied on the application of a debtor or mortgagor, that, in the circumstances relating to the relevant credit contract or mortgage at the time it was entered into, the contract or mortgage was unjust, re-open the transaction that gave rise to the contract or mortgage. Section 76(2) provides, relevantly, that in determining whether a term of a particular credit contract or mortgage is unjust in the circumstances relating to it at the time it was entered into (or changed), the Court is to have regard to the public interest and to all the circumstances of the case and may have regard to 16 matters set out at (a) to (p) of s 76(2), including “any … relevant factor”. In determining whether a credit contract is unjust, the Court is not to have regard to any injustice arising from circumstances that were not reasonably foreseeable when the contract was entered into: s 76(4).

38 The position in relation to the application of s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the “ASIC Act”) requires a little elaboration. In the period, relevantly, 2010 and up to and including 31 December 2011, s 12CB of the ASIC Act provided that a person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply (or possible supply) of financial services to a person, engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable: s 12CB(1). “Financial services” in this section is a reference to financial services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use: s 12CB(6). The statutory “requirement” of s 12CB(1) requires the Court to consider the conduct of the supplier of the financial service in “all the circumstances”: Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (2016) 90 ALJR 835; [2016] HCA 28, Keane J at [294]. See, however, the circumstances falling within s 12CB(4)(a), below.

39 Without limiting the matters to which the Court may have regard for the purpose of determining whether a supplier of a financial service to a consumer has contravened s 12CB(1), s 12CB(2) sets out five matters to which the Court may have regard. They are these:

(a) the relative strengths of the bargaining positions of the supplier and the consumer; and

(b) whether, as a result of conduct engaged in by the supplier, the consumer was required to comply with conditions that were not reasonably necessary for the protection of the legitimate interests of the supplier; and

(c) whether, the consumer was able to understand any documents relating to the supply or possible supply of the services; and

(d) whether any undue influence or pressure was exerted on, or any unfair tactics were used against, the consumer or a person acting on behalf of the consumer by the supplier or a person acting on behalf of the supplier in relation to the supply or possible supply of the services; and

(e) the amount for which, and the circumstances under which, the consumer could have acquired identical or equivalent services from a person other than the supplier.

40 For the purpose of determining whether a person has contravened s 12CB(1), the Court must not have regard to “any circumstances” that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time of the alleged contravention: s 12CB(4)(a).

41 So far as the supply of financial services is concerned, s 12CC(1) prohibits (as the section stood up to and including 31 December 2011) a person from engaging in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable, in connection with the supply (or possible supply) of those services to another person (other than a listed public company), where the acquisition of the service is or would be for the purpose of trade or commerce (that is, a business transaction rather than a consumer transaction): s 12CC(1)(a) and s 12CC(6).

42 Without “in any way” (a phrase not present in s 12CB(1)) limiting the matters to which the Court may have regard in determining whether a person has contravened s 12CC(1), the Court may have regard to 12 matters set out at s 12CC(2)(a) to (k). Apart from the particular matter of the business capacity of the recipient of the service for the purposes of s 12CC(1), the factors at s 12CC(2)(a) to (e) are in the same terms as the factors recited at s 12CB(2)(a) to (e) in relation to consumer transactions.

43 However, ss 12CB and 12CC were amended effective from 1 January 2012 giving rise to the “new s 12CB” and the “new s 12CC” of the ASIC Act, with the result that the earlier provisions were, in effect, unified in a single statutory prohibition upon unconscionable conduct.

44 The new s 12CB prohibits a person from engaging in conduct, in trade or commerce, that is, in connection with the supply of financial services (relevantly for these proceedings), unconscionable, in all the circumstances.

45 The new s 12CB and the prohibition within it no longer retains the prior distinction between the supply of financial services “of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use” (a consumer transaction: the old ss 12CB(1) and 12CB(5)) on the one hand, and the supply of financial services in business transactions (the old ss 12CC(1) and 12CC(6)) on the other hand.

46 Although the language of the new s 12CB(1), as to the supply of financial services, is in similar terms to the earlier s 12CB(1), it is nevertheless an entirely new provision not limited to what might loosely be called consumer transactions yet applying to them according to the integers of the new section and also other supply circumstances.

47 The new s 12CC(1) sets out 12 matters to which the Court may have regard in determining whether a person has contravened the new unified s 12CB(1) in the supply of financial services, without limiting the matters to which the Court may have regard. In other words, the 12 matters recited at s 12CC(1) are non-exhaustive. The 12 matters set out in the new s 12CC(1)(a) to (l) are essentially in the same terms as those set out in the earlier s 12CC(2)(a) to (k) although those earlier factors were expressly considerations relevant to possible contraventions of the bifurcated version of the prohibition as it applied to financial supply transactions to business recipients.

48 As mentioned, that distinction is now gone.

49 The new s 12CB(4) sets out the intention of the Parliament with respect to the new s 12CB.

50 The new s 12CB(3) provides (like the earlier s 12CB(4)(a)), that in determining whether a person has contravened s 12CB(1), the Court must not have regard to any circumstances that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time of the alleged contravention. The new s 12CB(3)(b) provides that in determining whether a person has contravened the new s 12CB(1), the Court “may have regard to conduct engaged in, or circumstances existing, before the commencement of this section” [emphasis added]: that is, prior to 1 January 2012. The earlier s 12CB contains s 12CB(4)(b) which is in the same terms as s 12CB(3)(b) except, of course, that subsection operates by reference to the commencement date of the earlier s 12CB.

51 Orthodoxy requires that the relevant prohibition (as a matter of substantive law) against which the conduct of Channic is to be considered is s 12CB as it stood (in relation to conduct up to 31 December 2011) at the time of the contended contraventions informed by the matters at s 12CB(2) as it stood, among any other considerations the Court regards as relevant to the conduct, “in all the circumstances”. The new ss 12CB(1) and 12CC(1) apply to the conduct of the first respondent occurring on and from 1 January 2012. Section 7(2)(b) and (c) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) provide that if an Act amends an Act or part of an Act, the amendment does not affect the previous operation of the affected Act (or part) or affect any liability accrued or incurred under the amended Act. The general rule of the common law is that a statute changing the law ought not, unless the intention appears with reasonable certainty, to be understood as applying to facts or events that have already occurred in such a way as to confer or impose or otherwise affect liabilities which the law had defined by reference to past events (leaving aside the application of the difficult distinction between substantive rights and liabilities on the one hand and procedural and remedial matters on the other hand): Maxwell v Murphy (1957) 96 CLR 261 at 267, Dixon CJ.

52 Having regard to new s 12CB(3)(b), a question arises of whether the new ss 12CB and 12CC evince a parliamentary intention to apply retrospectively to conduct prior to 1 January 2012. Obviously enough, the new s 12CB in some respects looks back to earlier facts or events in the sense that s 12CB(3)(b) enables the Court to have regard to conduct engaged in, or circumstances existing before 1 January 2012. This provision does not mean, however, that the content of the prohibition in the new s 12CB(1) applies to conduct prior to 1 January 2012. It simply means that in determining whether a person has contravened the new s 12CB(1) by engaging in unconscionable conduct, in all the circumstances, on and from 1 January 2012, the Court may have regard to conduct occurring before that date or circumstances existing before that date.

53 There is no express or inferential intention to apply the new s 12CB or s 12CC to facts or events prior to 1 January 2012.

54 That being so, a further question arises, in relation to the application of the pre-amendment provisions, of whether the seven further factors set out in s 12CC(2) as applying to “business transactions” nevertheless relevantly inform the question of whether a person has contravened s 12CB(1), as the five factors set out at s 12CB(2) (see [39] of these reasons) are non-exhaustive considerations which do not operate to limit the matters to which the Court may have regard for the purpose of determining whether a person has engaged in unconscionable conduct in the supply of financial services.

55 It seems to me that those additional seven factors at s 12CC(2) may well be matters to which the Court may have regard in determining whether a contravention of s 12CB(1) has occurred in all the circumstances of the case. Those matters may give “guidance” as to the content of the notion of unconscionability. They may assist in setting a framework for the values that lie behind the notion of the relevant conscience of the supplier of the financial service to a consumer. In that regard, see the observations of Allsop CJ in Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (2015) 236 FCR 199; [2015] FCAFC 50 at 285. Allsop CJ also took the view that the factors contained in the new s 12CC(1) also inform the content of the notion of the relevant conscience of the parties. As already mentioned, the 12 factors in the new s 12CC(1) are in substantially the same terms as the 12 factors in the earlier provision, s 12CC(2)(a) to (k). The statute, by s 12CB(2) gives particular attention to the five factors identified at [39] of these reasons although those matters, do not limit, expressly, the matters to which the Court may have regard for the purpose of determining whether a person, in trade or commerce, has engaged in unconscionable conduct in the supply of financial services. Those other matters that might be taken into account include the additional matters mentioned at s 12CC(2)(f) to (k) where relevant and material having regard to the circumstances of engagement between the supplier of the financial service and the individual consumer. These reasons are arranged in the following way according to the following topics:

PART | SUBJECT MATTER | PAGE |

Part 1 | The statutory background | 1 |

Part 2 | The originating application and some related matters | 12 |

Part 3 | The position reached by the parties on the face of the pleadings | 17 |

Part 4 | The questions to be addressed so far as the NCCP Act is concerned | 37 |

Part 5 | The admissions | 40 |

Part 6 | The evidence of Ms Adele Kingsburra | 46 |

Part 7 | The Kingsburra documents | 72 |

Part 8 | The evidence of Mr Kevin Humphreys | 79 |

Part 9 | The evidence of Ms Prunella Kathleen Harris | 96 |

Part 10 | The evidence of Ms Kerryn Gerthel Smith | 122 |

Part 11 | The evidence of Mr William Damien Noble (called “Damien”) and Ms Joan Cecily Noble | 146 |

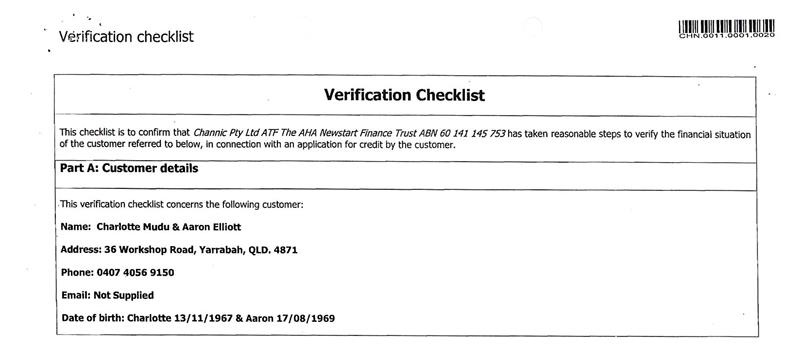

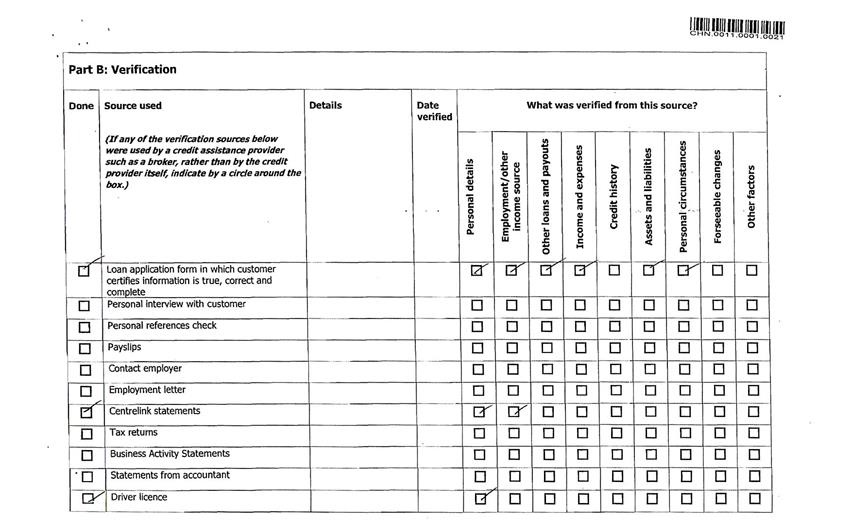

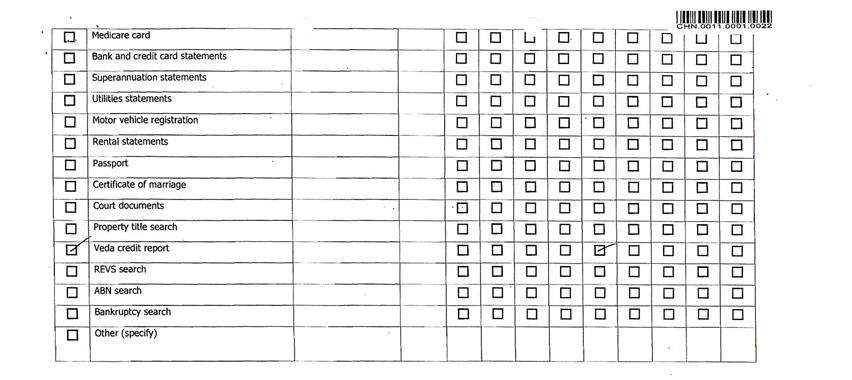

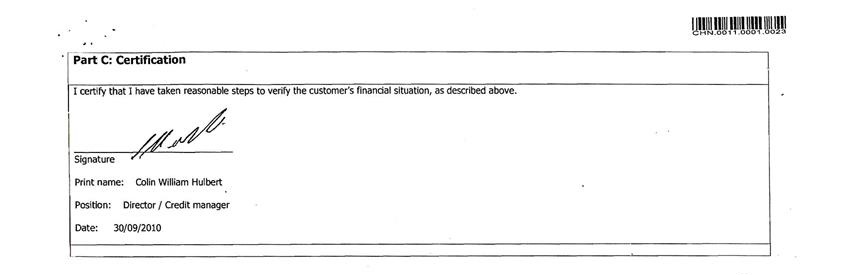

Part 12 | The evidence of Ms Charlotte Mudu | 169 |

Part 13 | The evidence of Ms Donna Gayle Yeatman | 186 |

Part 14 | The evidence of Ms Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah | 201 |

Part 15 | The evidence of Ms Rhonda Lorraine Brim | 215 |

Part 16 | The evidence of Mr Vance Henry Gordon and Ms May Estell Stanley | 235 |

Part 17 | The evidence of Ms Leandrea Rose Raymond | 245 |

Part 18 | The precision in the evidence and the conduct of the proceedings | 258 |

Part 19 | The evidence of Mr Colin Hulbert | 259 |

Part 20 | The evidence of Mr Hulbert given in cross-examination | 279 |

Part 21 | The evidence of Mr Kevin Foo | 310 |

Part 22 | The evidence of Mr Michael Southon | 311 |

Part 23 | The evidence of Ms Tegan Green | 323 |

Part 24 | The evidence of Mr Shayne Muldoon and Ms Felilta Sky Eckermann | 335 |

Part 25 | The evidence of Ms Heidi Stafford | 344 |

Part 26 | The evidence of Ms Marnie Toohey | 353 |

Part 27 | The evidence of Ms Bobbie-Jo Lourie | 365 |

Part 28 | The evidence of Ms Angel Pokia | 374 |

Part 29 | The evidence of Mr Wayne McKenzie | 382 |

Part 30 | The evidence of Ms Georgina Bataillard | 394 |

Part 31 | The evidence of Mr Haydn Cooper | 399 |

Part 32 | The evidence of Mr Spiro Vasilakis | 400 |

Part 33 | Assessment of the evidence and conclusions on the questions in issue | 427 |

PART 2: The Originating Application and some related matters

56 By its originating application, the applicant, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”) seeks the following declarations, injunctions and orders against the respective respondents.

57 The first respondent is Channic Pty Ltd (“Channic”).

58 As against Channic, ASIC seeks three declarations.

59 First, a declaration pursuant to s 166 of the NCCP Act that Channic has contravened ss 128, 130, 131 and 133 of the NCCP Act.

60 Second, a declaration that credit contracts entered into by Channic with consumers as described in the statement of claim were unjust within the meaning of s 76 of Schedule 1 to the NCCP Act otherwise described as the National Credit Code: as to the credit contracts see [73] of these reasons.

61 Third, a declaration that Channic, by engaging in the conduct recited in the statement of claim, engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 12CB of the ASIC Act.

62 The first two declarations form the basis upon which ASIC seeks the imposition of civil pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 167 of the NCCP Act on Channic for contraventions of ss 128, 130, 131 and 133 of the NCCP Act.

63 ASIC seeks an injunction pursuant to s 177 of the NCCP Act to restrain Channic from further contraventions of those sections of the NCCP Act and an injunction pursuant to s 12GD of the ASIC Act to restrain Channic from further engaging in unconscionable conduct within the meaning of s 12CB of the ASIC Act in relation to Channic’s credit contracts with the consumers described in the table at [73] of these reasons or in relation to Channic’s entry into any future credit contracts.

64 ASIC also seeks orders pursuant to s 76 of the National Credit Code that each of the credit contracts made between Channic and the borrowers described at [73] of these reasons be reopened and the borrowers be further relieved of any liability to Channic in relation to the credit contracts, the credit contracts be set aside ab initio and/or Channic repay to each of the borrowers the amounts paid by each of them under the respective credit contracts.

65 The second respondent is Cash Brokers Pty Ltd (“CBPL”).

66 As against CBPL, ASIC seeks a declaration that CBPL has contravened ss 113, 114, 115, 117, 118, 121 and 123 of the NCCP Act.

67 ASIC also seeks the imposition of civil pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 167 of the NCCP Act on CBPL for contraventions of ss 113, 114, 115, 117, 118, 121 and 123 of the NCCP Act. ASIC seeks an injunction under s 117 of the NCCP Act to restrain CBPL from further contravening these provisions in relation to the entry by CBPL into any future credit contracts.

68 The third respondent is Mr Colin William Hulbert.

69 At the time of the pleaded conduct, Mr Hulbert was the sole shareholder, sole director and controlling mind of Channic. He was also the duly authorised agent of that entity. He was the sole director of and a shareholder in CBPL. He was the controlling mind of that company and its duly authorised agent. As against Mr Hulbert, ASIC seeks a declaration that Mr Hulbert has contravened ss 113, 114, 115, 117,118, 121, 123, 128, 130, 131 and 133 of the NCCP Act. ASIC also seeks the imposition of civil pecuniary penalties on Mr Hulbert for contraventions of those sections of the NCCP Act. ASIC seeks an injunction restraining Mr Hulbert from further contravening those sections of the Act.

70 The originating application is supported by an extensive statement of claim (220 pages) setting out all of the material facts concerning the contended conduct contraventions. The allegations made by ASIC fall into three categories. ASIC describes, as the “principal category”, those contended contraventions consisting of breaches of the responsible lending obligations under Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act by Channic and CBPL and the involvement of Mr Hulbert in those contraventions.

71 The second category consists of allegations of unconscionable conduct under s 12CB of the ASIC Act by Channic.

72 The third category consists of allegations that the loan contracts were “unjust transactions” under s 76 of the National Credit Code.

73 By its statement of claim, ASIC contends that contravening conduct occurred on the part of Channic in connection with steps taken (or not taken) by it in relation to transactions concerning the following consumers (in the order of the pleading) who entered into loan contracts (credit contracts) with Channic on the following dates in relation to the purchase of the following motor vehicles and that contravening conduct occurred on the part of CBPL in the provision of credit assistance to those consumers (except for Leandrea Rose Raymond) concerning those credit contracts:

Borrower | Vehicle | Loan Contract Date |

Adele Dorothea Kingsburra | 1997 Hyundai Elantra SE Sedan | 13 July 2010 |

Prunella Kathleen Harris | 1997 Ford Fairmont Ghia EL Sedan | 20 September 2010 |

Vance Henry Gordon & Estell May Stanley | 1993 Holden Barina Hatchback | 29 September 2010 |

Rhonda Lorraine Brim | 1990 Ford Spectron Station Wagon | 22 September 2010 |

Kerryn Gerthel Smith | 2001 Holden Commodore VX Station Wagon | 15 April 2011 |

Joan Cecily Noble & William Damien Noble | 1995 Mitsubishi Pajero GLX | 2 March 2011 |

Muriel Grace Elizabeth Dabah & Estelle Harris | 1998 Toyota Camry Conquest V2OR Sedan | 16 July 2010 |

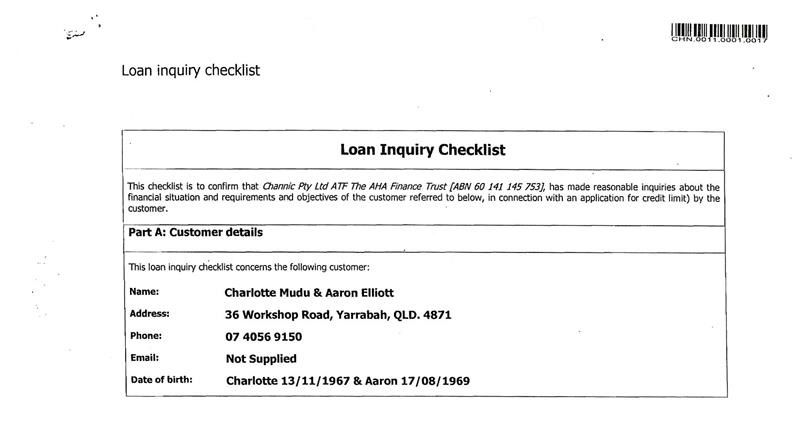

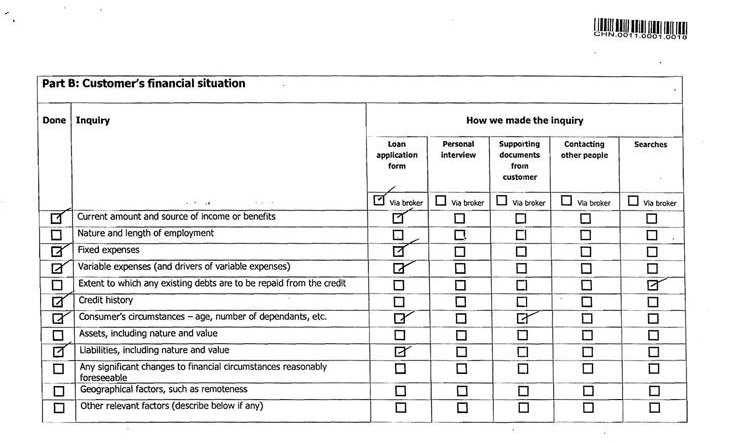

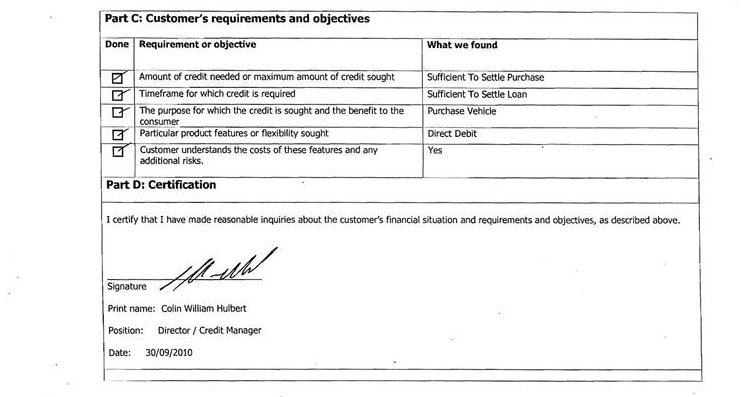

Charlotte Mudu & Aaron Elliott | 1994 Holden Apollo Sedan | 14 December 2010 |

Donna Gayle Yeatman & Farren Yeatman | 1997 Holden Commodore Executive VT Sedan | 16 September 2010 |

Leandrea Rose Raymond | 1996 Hyundai Excel Hatchback | 25 June 2012 |

74 All the vehicles were purchased by the consumers from an entity called ANG Hulbert & Associates Pty Ltd (“ANG”) trading as either “SuperCheap Auto” or “SuperCheap Car Sales” which conducted the business of selling used motor vehicles initially from premises at 484 Mulgrave Road, Earlville (a suburb of Cairns) in Queensland and then from 132 Spence Street, Parramatta Park (Cairns) in Queensland. Mr Hulbert was the sole director, sole shareholder and controlling mind of ANG.

The early history of the matter

75 The history of the matter is a little unusual in the following sense.

76 The respondents are represented (and were represented in the conduct of the trial) by Dr Robert Spence who conducts practice as a solicitor under the description “Integrity Criminal Legal” of Elizabeth Street, Sydney. On 3 October 2013, Dr Spence wrote an open letter to ASIC in which he said this in relation to these proceedings framed by the originating application and the statement of claim:

I confirm that I am the solicitor acting for the Respondents in this matter. Mr Anthony Collins, barrister-at-law has a received a brief to appear in this matter.

Mr Hulbert has confirmed on behalf of the Respondents that they do not wish to contest any of the orders set out in the application filed in the Queensland Federal Court by the Applicant.

I am obliged for your co-operation in agreeing to communicating directly with Mr Collins in relation to these proceedings.

77 On 8 October 2013 the matter came before the Court for the first time for directions. All of the respondents were represented by Mr A.P.J. Collins of counsel. ASIC was represented by Mr Derrington QC. An affidavit was read by ASIC’s counsel exhibiting Dr Spence’s letter of 3 October 2013: affidavit Scott Edward Seefeld sworn 8 October 2013. ASIC also relied on an affidavit of Jamie William Black sworn 3 October 2013.

78 Mr Derrington observed that the statement of claim had been served (on 20 August 2013) but no defence had been filed and that it appeared that the respondents did not intend to file a defence as they had chosen not to contest the matters of fact set out in the statement of claim: T, p 3, lns 5-10; T, p 2, lns 22-23, 8 October 2013. Thus the matter would proceed to a hearing in which the questions of fact were to be uncontested. Mr Derrington correctly described the statement of claim as “both long and complicated” (T, p 3, ln 30). That is so because it asserts a lengthy factual matrix against the respondents involving all claims in respect of all consumers coupled with an accessorial liability claim against Mr Hulbert in respect of the Channic contraventions. It was contemplated that a less complicated statement of agreed facts would be formulated upon which the Court could and would rely. The statement of agreed facts was to be supported by written submissions. A discussion took place about possible dates for hearing the matter, preferably over a single day. Mr Collins seemed to embrace those propositions and suggested that the matter would conclude inside one day, on the footing as suggested.

79 Thereafter, the parties attempted to agree upon a statement of facts to be put to the Court. It seems that a document of approximately 123 pages had been formulated on behalf of ASIC setting out all the relevant factual matters. Mr Collins described the document as containing approximately 800 facts based on a pleading containing over 400 paragraphs. Emphasis was placed by ASIC upon the earlier unqualified unequivocal acceptance of the statement of claim with no defence having been filed.

80 Mr Collins explained at the further directions hearing on 4 February 2014 that there were “aspects” of the statement of claim and “aspects” of the proposed agreed statement of facts that were perceived by the respondents to be not “strictly accurate”. Mr Collins observed that since agreement had not been reached about the proposed statement of facts, ASIC had proposed, prior to the directions hearing, that the respondents put on a defence: T, p 6, lns 30-33, 4 February 2014. As to the statement of claim, Mr Collins observed that “the vast majority are accepted, some are accepted but with slight nuances or qualifications”. Mr Collins also observed that he did not “want it to be said that there’s some sort of about-face” because “the vast majority will be accepted”: T, p 8, lns 8-9; 17-18. Proposed directions were then discussed for the filing of a defence. The scope of the matters which would then be in issue would be revealed.

81 As things transpired, Mr Collins ceased to act for the respondents.

82 Dr Spence thereafter acted for them.

83 A defence was put on by Dr Spence. It was struck out as being embarrassing in the technical sense with leave given to re-plead in conformity with the Federal Court Rules 2011. An amended defence was then filed. By the defence, Dr Spence pleaded to not only the material facts but each of the individual particulars in the lengthy and complicated statement of claim. Accordingly, the amended defence is also a lengthy and complicated document.

84 By the amended defence a range of matters are admitted by the respondents. Many other matters are denied or the subject of a contention that the matters are not within the knowledge of the respondents. Statements were put on. All of ASIC’s witnesses were required for cross-examination by Dr Spence. The proceeding proceeded to trial.

85 It is now necessary to address aspects of the factual matters which are admitted on the pleadings and identify the range of questions now in controversy. In doing so, I will simply recite the relevant matters without attributing each of them to paragraphs of the respective pleadings.

PART 3: The position reached by the parties on the face of the pleadings

86 Unless otherwise mentioned, the following matters (relevant to all material times in the proceeding) are admitted and thus not in issue.

87 ASIC has standing to bring the proceeding for the relief it seeks.

88 ANG engaged in the business of selling used motor vehicles. It advertised under the prominent name “SUPER CHEAP” followed by the words “Car Sales” (“Supercheap”). Mr Hulbert was its sole director, sole shareholder and controlling mind. Supercheap operated its used car sales business from at least 16 June 2010 to 20 September 2011 at and from premises at 484 Mulgrave Road, Earlville Cairns (the “first premises”) and from 21 September 2011 at and from premises at 132 Spence Street, Parramatta Park, Cairns (the “second premises”).

89 Channic engaged in the business of providing credit for profit. It did so as trustee for the “AHA New Start Finance Trust”. Mr Hulbert was the sole director, controlling mind and authorised agent of Channic. The company search shows that Mr Hulbert was Channic’s sole shareholder.

90 CBPL was engaged in the business of brokering credit for profit. Mr Hulbert was the sole director, controlling mind and authorised agent of CBPL. The company search shows that he was CBPL’s sole shareholder.

91 Channic and CBPL conducted their respective business undertakings at and from the first premises until 20 September 2011 and then at and from the second premises.

92 The usual operation of those three businesses involved used cars being offered for sale or sold to members of the public by Supercheap. The sale of the cars would usually be financed by loans. Supercheap would be the seller and would convey title to the vehicle to the consumer. Channic would provide loans to customers to buy the vehicles. ASIC contends that CBPL would “purport” to broker a loan from Channic to assist a customer to purchase the vehicle. The respondents contend that CBPL “actually” brokered such loans from Channic. ASIC says that CBPL only arranged loans from Channic. The respondents say that CBPL arranged loans with other credit providers and that Supercheap sold cars financed by other lenders.

93 Mr Kevin Humphreys was either an employee of, or contractor to, Supercheap. He was Supercheap’s agent. He was also either an employee of, or a contractor to, CBPL. He was CBPL’s agent. The respondents deny he was an employee or an agent of, or a contractor to, Channic.

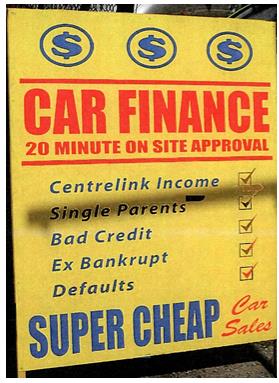

94 Supercheap took out written advertisements by which it said that finance was offered to buyers: with a 20 minute on-site approval; to persons in receipt of Centrelink income; to persons with bad credit histories; and to ex-bankrupts. Supercheap advertised its business by means of a large sign outside its business premises visible to passers-by as set out below (Applicant’s Tender Bundle, Vol 1, Tab 4):

95 The respondents deny that the business activities of Supercheap, Channic and CBPL were likely to attract persons who were: unable to obtain or unlikely to seek loans from major banking institutions due to a poor credit history or because they perceived themselves or perceived as having a poor credit history; in need of an inexpensive vehicle and an inexpensive loan; lacking in commercial experience; unlikely to understand or appreciate legal documentation not drafted in simple English; unlikely to be able to evaluate whether the terms of any loan were fair or commercial.

96 On or about 16 June 2010, Channic made an application for registration and was registered as a credit provider under the Transitional Provisions Act. On 13 December 2010, Channic applied for an Australian Credit Licence under the NCCP Act and on 31 January 2011 that licence was granted. Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act applied to Channic, in the period relevant to these proceedings, either as if it was a licensee or because it was a licensee Each loan contract entered into by Channic with each borrower described in the statement of claim (and described at [73] of these reasons) constituted the provision of credit for the purposes of s 5 of the NCCP Act. See also s 3(1) of the National Credit Code.

97 On or about 18 June 2010, CBPL made an application for registration and was registered as a credit assistance provider under the Transitional Provisions Act. On 22 December 2010, CBPL applied for an Australian Credit Licence under the NCCP Act and on 24 February 2011 that licence was granted. Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act applied to CBPL, in the period relevant to these proceedings, either as if it was a licensee or because it was a licensee.

98 As to the “credit broking activities” of CBPL, each buyer of a car with whom CBPL dealt, was a consumer within the meaning of the NCCP Act. CBPL dealt directly with each buyer in the course of or as part of its business. Each “loan contract” in respect of which CBPL provided credit assistance to the borrower was a credit contract within the meaning of s 4 of the National Credit Code. As to the credit providing activities of Channic, each buyer of a car with whom Channic dealt was a consumer within the meaning of the NCCP Act. Channic provided credit by the provision of a loan to the buyer of the car.

99 I propose to now illustrate the position in relation to the first of the consumer buyers of a car, Ms Kingsburra, who engaged with Channic and CBPL, by identifying the pleaded position (admissions and matters in contention) concerning her circumstances and then examine the evidence of Ms Kingsburra and the particular documents immediately relevant to Ms Kingsburra (which, in the main, characterise the method adopted by CBPL and Channic in the conduct of their respective undertakings). I will then examine the evidence of the respondents.

Ms Adele Dorothea Kingsburra

100 As to the pleaded position, the following facts are admitted except where otherwise indicated.

101 Ms Kingsburra attended the first business premises (484 Mulgrave Road) on 6 July 2010 for the purpose of purchasing a car for one of her sons, paying a deposit as part of the purchase price and paying the remaining part of the purchase price by instalments. At the first business premises on 6 July 2010, Mr Humphreys for Supercheap, showed Ms Kingsburra a 1997 Hyundai Elantra Sedan. ASIC contends that Mr Humphreys told her that he had used the car, sometimes, for his own personal purposes; it had no problems; and the existing paint damage to it could be fixed cheaply. The respondents say that they have no knowledge of what was said by Mr Humphreys to Ms Kingsburra.

102 ASIC says that Mr Humphreys told Ms Kingsburra that the purchase price was $8,990.00, a deposit of $1,500.00 would be required and if Ms Kingsburra wanted “mag wheels” an extra $200.00 deposit would be required. These matters, however, are admitted by the respondents even though these matters also fall within the knowledge of Mr Humphreys.

103 Ms Kingsburra agreed, with Mr Humphreys, to buy the car for $8,990.00 by paying a deposit of $1,500.00 (plus $200.00 for the mag wheels) with the balance to be paid by instalments. The respondents say the deposit was $1,700.00 for the car and it included mag wheels.

104 On 10 July 2010, Ms Kingsburra returned to the first business premises. ASIC says she paid a deposit of $1,500.00 plus $200.00. The respondents say she paid a deposit of $1,700.00. ASIC says Mr Humphreys told Ms Kingsburra she would have to return to the premises on another day to collect the vehicle.

Ms Adele Dorothea Kingsburra and Cash Brokers Pty Ltd

105 ASIC says that on 6 July 2010, Mr Humphreys inquired of Ms Kingsburra as to various aspects of her financial situation. On 6 July 2010, Mr Humphreys substantially completed or filled out a “Credit Application Form” in the name of Ms Kingsburra. ASIC says this was done, by CBPL, by Mr Humphreys. ASIC says that Mr Humphreys “caused” Ms Kingsburra to sign the Credit Application Form. The point of distinction pleaded by the respondents is that they say that the Credit Application Form was “offered” to Ms Kingsburra (by CBPL) “for her signature” and “she signed it”.

106 ASIC says that Mr Humphreys advised Ms Kingsburra to obtain a statement from Centrelink showing the amount of her regular Centrelink social security payments so as to support the application for credit for the purchase of the car and advised her to obtain also a letter from her partner stating that he paid her board of $150.00 per fortnight, to further support the credit application. The respondents plead that they have no knowledge of these matters although Mr Hulbert pleads that he believes that the person paying board to Ms Kingsburra was not her partner.

107 ASIC contends that Mr Humphreys told Ms Kingsburra that her weekly repayment instalment would be $120.00; did not advise Ms Kingsburra of any brokerage payable to CBPL or that she was entering into a brokerage agreement with CBPL; did not tell Ms Kingsburra that brokerage payable to CBPL would be added to the amount of the credit which she would be obtaining; and, did not tell Ms Kingsburra that there was a legal entity, CBPL, acting as a broker, separate from the lender, Channic, and the seller of the car, Supercheap. As to each of these matters, the respondents do not admit the facts and say that the matters are not within their knowledge.

108 ASIC says that on 6 July 2010, Mr Humphreys for CBPL prepared a document called a “Preliminary Test” which purported to be a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 115 of the NCCP Act of whether a loan to Ms Kingsburra of $7,290.00 would be unsuitable for her and which purported to analyse the capacity of Ms Kingsburra to repay a loan of $7,290.00. The respondents admit these matters except that they say that the Preliminary Test document is dated 7 July 2010.

109 The respondents also admit that Mr Humphreys for CBPL: did not include any brokerage fee in the amount of the credit assumed by the Preliminary Test; wrote a letter to Channic, on behalf of Ms Kingsburra, applying for a loan of $7,290.00 with weekly repayments of $119.45 (accepted, for the purposes of the admission, as the “Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan”; also referred to later in these reasons as “CB/KPL”); and delivered the Preliminary Test, Credit Application Form and the letter to Channic, to Channic, thereby applying for that loan on behalf of Ms Kingsburra.

110 ASIC says that by doing the things described at [108] and [109] of these reasons, CBPL “suggested” to Ms Kingsburra that she “apply” for a “particular” credit contract with a “particular” credit provider. The respondents say that this matter is not within their knowledge.

111 The respondents, however, admit that: CBPL “assisted” Ms Kingsburra to apply for a particular credit contract (the Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan) with a particular credit provider (Channic) and on 6 July 2010 CBPL provided “credit assistance” to Ms Kingsburra within the meaning of s 8 and s 115 of the NCCP Act.

112 On 13 July 2010, subsequent to providing credit assistance to Ms Kingsburra on 6 July 2010, CBPL, by Mr Humphreys, received from Ms Kingsburra a copy of a Centrelink Statement dated 12 July 2010 and a signed statement from Mr Garry Gilmartin that he paid board each week to Ms Kingsburra of $150.00.

113 ASIC asserts that at no time prior to purporting to make a preliminary assessment, if any, in relation to Ms Kingsburra on 6 July 2010 did CBPL make any or any reasonable inquiries as to Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives in relation to the Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan. CBPL, it is said, failed to inquire as to the amount of the loan which Ms Kingsburra required; the interest rate which she required; the length of time over which Ms Kingsburra intended that any credit provided would be repaid; and whether or not Ms Kingsburra required the loan for a purpose of paying brokerage of any kind which would be chargeable on the loan transaction. The respondents do not admit these matters and say that each matter is a fact not within the knowledge of the respondents.

114 ASIC also asserts that at no time prior to purporting to make a preliminary assessment, if any, in relation to Ms Kingsburra on 6 July 2010 did CBPL make any reasonable inquiries as to Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. CBPL, it is said, failed to inquire as to the usual weekly, fortnightly or monthly expenses of Ms Kingsburra; the amount of money which Ms Kingsburra usually had available each week, fortnight or month which might be available for repaying a loan. The respondents do not admit these matters and say that each matter is a fact not within the knowledge of the respondents. CBPL, it is said, also failed to inquire as to Ms Kingsburra’s “actual living expenses” but instead applied an amount of $2,925.00 as her monthly expenses in the Preliminary Test document using a “standardised formula”, as set out in the Preliminary Test document, of $1,300.00 per month for a de facto or married couple and $325.00 for each of Ms Kingsburra’s five dependents. The respondents do not admit these factual matters and say that each of them is not within their knowledge.

115 However, the respondents admit that CBPL “used a standardised formula as particularised”.

116 It is also said that at no time prior to 6 July 2010 when purporting to make a preliminary assessment did CBPL take any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. This matter is denied by the respondents.

117 However, the respondents admit that CBPL could not have undertaken any or any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation as the preparation of the Preliminary Test and the provision of credit assistance to Ms Kingsburra occurred on 6 July 2010 but the Centrelink statement and the statement from Mr Gilmartin were not obtained by CBPL until, at the earliest, 13 July 2010: para 25.3 and para 25.3(a) of the statement of claim and the amended defence. I mention, on this occasion, the paragraph references because it seems to me that Dr Spence was probably seeking to deny a failure by the respondents to take any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation but admit, simply, the facts about CBPL having received the Centrelink Statement and Mr Gilmartin’s statement no earlier than 13 July 2010.

118 The respondents deny that CBPL did not otherwise obtain information which would evidence or support (that is to say, verify) the information provided by Ms Kingsburra as to her financial situation.

119 ASIC says that CBPL did not verify Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses but instead applied an amount of $2,925.00 as her monthly living expenses for the purposes of the Preliminary Test using the standardised formula of $1,300.00 per month for de facto or married couple and $325.00 for each of Ms Kingsburra’s five dependents. The respondents deny that CBPL failed to verify Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses. The respondents admit that CBPL used a standardised formula as alleged by ASIC but say that that use “did not supplant the verification that [CBPL] made in respect of Yeatmans’ actual living expenses”. I proceed on the basis that the respondents were intending to refer to Ms Kingsburra at this point in their pleading.

120 The respondents deny that CBPL contravened s 117 of the NCCP Act.

121 However, the respondents admit that at the time of the provision by CBPL of credit assistance to Ms Kingsburra, CBPL had not, within 90 days before the day on which the credit assistance was provided, or at all, made any preliminary assessment that was in accordance with s 116(1) of the NCCP Act and that the Preliminary Test did not specify the period it covered. Although there is a misdescription at para 27.1b of the amended defence (which refers to para 27.1a of the statement of claim rather than para 27.1b), it seems clear enough that the respondents also admit that the preliminary test did not contain an assessment of whether the Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan would be unsuitable: para 27.1b, amended defence.

122 There is no misdescription as to para 27.2a and the respondents admit that CBPL had not, within 90 days before the day on which credit assistance was provided, or at all, made any preliminary assessment that “covered the period that was proposed for the entering into the credit contract”. They admit that the “period which should have been covered by any preliminary assessment was the period during which it was proposed the credit contract would be entered into”. The respondents seem to admit (although there may be another misdescription of para of the statement of claim in the amended defence), that CBPL had not within 90 days before the day on which the credit assistance was provided, or at all, undertaken the inquiries and verification required by s 117 of the NCCP Act.

123 The respondents also admit that CBPL, by providing credit assistance to Ms Kingsburra, contravened s 115(1) of the NCCP Act.

124 ASIC says that the Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan was unsuitable for Ms Kingsburra because at the time CBPL provided credit assistance it was likely that Ms Kingsburra would be unable to comply with her financial obligations under the loan or would only be able to comply with those obligations with substantial hardship; Ms Kingsburra’s accounts were regularly overdrawn; the accounts were rarely in credit; and in the ordinary course, any social security payments paid into Ms Kingsburra’s account were withdrawn on or about the day on which the money was deposited. All of these matters are denied by the respondents. The respondents also deny that Ms Kingsburra had a number of recurring expenses such as repayments of cash advances made to her by “Cash Converters”. The respondents deny that Ms Kingsburra had a number of recurring expenses but admit that Ms Kingsburra was making payments on a loan previously provided by Cash Converters.

125 The respondents admit that in purporting to assess the unsuitability of the Cash Brokers/Kingsburra Proposed Loan, CBPL failed to take into account the cost per month of the motor vehicle insurance that Ms Kingsburra would be required to obtain pursuant to any loan agreement she entered into with Channic and also failed to take into account an estimate of the additional costs Ms Kingsburra would incur due to owning and maintaining a motor vehicle.

126 The respondents deny that the CB/KPL did not meet Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives. They deny that CBPL failed to make reasonable inquiries about Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives in relation to any finance she would obtain to assist in the completion of the purchase of the car and they deny that they “could not have been aware of” Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives for that purpose. They deny that the CB/KPL ought to have been assessed as “unsuitable” for Ms Kingsburra and deny that in failing to do so they contravened s 118(1) of the NCCP Act. They deny that CBPL contravened s 123(1) of the NCCP Act by suggesting that Ms Kingsburra apply for the CB/KPL and by assisting Ms Kingsburra to apply for that loan.

Ms Adele Dorothea Kingsburra and Channic

127 The respondents admit that on 6 July 2010, Channic prepared a document called a “Credit Suitability Assessment” (“CSA”) which: stated that it was made on 6 July 2010; was purportedly made in accordance with ss 128 and 129 of the NCCP Act; purported to assess the suitability of a loan to Ms Kingsburra from Channic in an amount of $8,301.50 for a period of 110 weeks at an interest rate of 48% (called the “Kingsburra Proposed Loan”); purported to assess that a loan in such terms was not unsuitable for Ms Kingsburra and that it met her needs and objectives during the period of the loan; and which stated that the period covered by the assessment was from 6 July 2010 to 6 August 2010.

128 The respondents admit that Ms Kingsburra returned to the first premises on 13 July 2010 where she completed a contract to purchase the car with the assistance of credit from Channic.

129 The respondents admit that on 13 July 2010, Ms Kingsburra entered into a loan agreement (the “Kingsburra Loan”) with Channic in writing comprising a document entitled Consumer Loan Contract and Mortgage No: 5030 (also called in these reasons the “Credit Contract”).

130 The respondents admit that pursuant to the Kingsburra Loan, Channic agreed to lend and Ms Kingsburra agreed to borrow an amount of $8,301.50 at an annual interest rate of 48% over a loan period of 110 weeks with amounts payable each week of $119.45 and a final payment of $114.30 with the first repayment to be made on 19 July 2010 and that on settlement of the loan, a sum of $990.00 would be paid to CBPL as brokerage and the sum of $7,290.00 would be paid to Supercheap for the purchase of the 1997 Hyundai Elantra motor vehicle.

131 ASIC says that at no time prior to preparing the Kingsburra CSA on 6 July 2010 (or at all) did Channic make any or any reasonable inquiries as to Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives in and for the proposed Kingsburra Loan. Channic failed, it is said, to inquire as to the amount of the loan Ms Kingsburra required; the interest rate she required; the length of time over which she intended that any credit provided would be repaid; and whether or not Ms Kingsburra required the loan for a purpose of paying brokerage of any kind which would be a charge on the loan transaction. As to all of these matters, the respondents do not admit the facts and say that each fact is not within the knowledge of the respondents and they further say, as to each fact, that “Kevin Humphreys prepared the Credit Suitability Assessment in respect of Ms Kingsburra”.

132 As to the question of inquiries, ASIC also says that at no time prior to preparing the Kingsburra CSA on 6 July 2010 or otherwise did Channic make any reasonable inquiries as to Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. Channic, it is said, failed to inquire as to: Ms Kingsburra’s weekly, fortnightly or monthly expenses; the amount of money which Ms Kingsburra usually had available at the end of each week, fortnight or month which might be available for repaying a loan; Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses and instead relied upon the Preliminary Test prepared by CBPL which applied an amount of monthly expenses of $2,925.00 based on the standardised formula contained in the Preliminary Test as earlier mentioned. As to each of these matters the respondents again say that these matters of fact are not within their knowledge and that Mr Humphreys prepared the Kingsburra CSA. As to the matter of applying the monthly amount of $2,925.00 based on the formula rather than conducting an inquiry into Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses, the respondents say that Mr Humphreys prepared the Kingsburra CSA and thus any failure to inquire into actual living expenses is not within the knowledge of the respondents but, nevertheless, the respondents admit that Channic “used a standardised formula [as alleged]”.

133 As to the question of verification, ASIC says that at no time prior to preparing the Kingsburra CSA on 6 July 2010 or at all did Channic take any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. Channic, it is said, first, could not have undertaken any or any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation as the CSA was completed on 6 July 2010 but the Centrelink Statement and the statement from Mr Gilmartin were not obtained by Channic until 13 July 2010. Second, Channic did not otherwise obtain information or material which would evidence or support the information provided by Ms Kingsburra as to her financial situation. Third, Channic did not verify Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses but instead relied on the Preliminary Test prepared by CBPL which applied a standardised formula as earlier described.

134 As to the matters at [133], the respondents deny that Channic failed to take any reasonable steps to verify Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. They deny that the CSA was completed on 6 July 2010 and say that it was completed on 7 July 2010. They do not admit that the Centrelink Statement and Mr Gilmartin’s statement were not obtained by Channic until 13 July 2010 and add “that that is not a matter of fact within the knowledge of the respondents”. They deny that Channic did not otherwise obtain information in verification of Ms Kingsburra’s financial situation. They do not admit that Channic failed to verify Ms Kingsburra’s actual living expenses although that is said to be a matter not within their knowledge because Mr Humphreys prepared the Kingsburra CSA. The respondents admit, however, that Channic “had reference to a standardised formula”, as particularised, but say that reference to the formula “was not such that it supplanted the verification undertaken by [Channic].

135 The respondents deny that Channic contravened s 130(1) of the NCCP Act.

136 The respondents admit that at the time of provision by Channic of credit to Ms Kingsburra, Channic had not, within 90 days before the day on which the credit was provided, or at all, undertaken the inquiries and verification required by s 130 of the NCCP Act. The respondents also admit that Channic, by providing credit to Ms Kingsburra, contravened s 128 of the NCCP Act.

137 ASIC says that Ms Kingsburra was a person who would be unable to comply with her financial obligations under the Kingsburra Proposed Loan or would only be able to comply with those obligations with substantial hardship for the reasons described in para 40.1 of the statement of claim (which repeats the matters at para 29 of the statement of claim) which are those matters described at [124] of these reasons.

138 The respondents deny that the Kingsburra Proposed Loan did not meet Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives. They deny that Channic had not made reasonable inquiries about Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives in relation to any finance obtained by her from Channic to assist in the completion of the purchase of the car. They deny that they could not have been aware of Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives for the finance. They deny that the requirements and objectives of Ms Kingsburra for the loan were that the loan be for an amount of $7,290.00 representing the difference between the cost of the car at $8,990.00 and the amount of $1,700.00 which was paid as a deposit. They deny that the requirements and objectives of Ms Kingsburra for the loan did not include any amount to be used to pay brokerage in obtaining the loan from Channic. They deny that the Kingsburra loan was for $8,301.50 in circumstances where Ms Kingsburra only required a loan of $7,290.00. They deny that Ms Kingsburra did not require or seek an amount of $990.00 to be included in the loan for brokerage. They deny that Ms Kingsburra was unaware that the loan amount included brokerage of $990.00. Although there is a misdescription at para 40.2(e) of the amended defence (which refers to 40.2(d) of the statement of claim rather than 40.2(e)) it seems clear that the respondents also deny para 40.2(e) of the statement of claim.

139 As to the notion that Channic, in making its assessment, relied upon the Preliminary Test prepared by CBPL and in doing so took into account a formula or standardised amount “as representing” Ms Kingsburra’s actual living costs and expenses resulting in an applied amount of $2,925.00 comprising $1,300.00 per month for a de facto or married couple and an additional $325.00 per month for each of Ms Kingsburra’s five dependents, the respondents say this. They deny that matter. However they then admit that CBPL made reference to a standardised formula as asserted but say that the use of that formula did not result in the Preliminary Test “being not referrable to the actual living costs and expenses of Ms Kingsburra”. As to the numbers, the respondents deny the formulation of the numbers pleaded against them and say that the formula used was based on Ms Kingsburra being a single person and not in a de facto relationship and they say that the relevant numbers derived from the formula were $2,575.00 being $950.00 per month for a single person and $325.00 for each dependent.

140 The respondents deny that they failed to take into account only the information which satisfied integers (a) and (b) of s 131(4) of the NCCP Act.

141 The respondents deny that Channic should have assessed the Kingsburra Proposed Loan as being unsuitable for Ms Kingsburra as a loan which would not have met Ms Kingsburra’s requirements and objectives. They deny that, in failing to assess the loan as unsuitable, they contravened s 131(1) of the NCCP Act. They deny that the loan was unsuitable. They deny that Channic contravened s 133(1) of the NCCP Act by entering into the Kingsburra Loan.

The unconscionable conduct aspects of the matter

142 The respondents deny that the provision of the loan to Ms Kingsburra by Channic was the provision of a “financial service” as that expression is used in s 12BAB of the ASIC Act.

143 The respondents admit that the Kingsburra Loan was entered into by Channic in the course of trade and commerce and they admit that Ms Kingsburra was desirous of acquiring a car and had, as her only source of income, the receipt of social security payments.

144 The respondents do not admit and have no knowledge of whether Ms Kingsburra had the care of eight children or was a person of limited education, as alleged.

145 They admit that Ms Kingsburra was a resident of the Yarrabah Aboriginal Community.

146 They have no knowledge of whether, as alleged, Ms Kingsburra had very limited ability to negotiate and to protect her own interests when dealing with people outside of her community.

147 As to the contention that Ms Kingsburra had limited knowledge of, or experience in relation to, financial transactions, the respondents deny that matter and say that Ms Kingsburra had some experience in financial transactions as she had previously obtained personal loans from a credit provider, Cash Converters.

148 As to whether Ms Kingsburra was not aware of the market values of used motor vehicles, as alleged, the respondents say that that is not a matter of fact within their knowledge. As to whether Ms Kingsburra was unable to ascertain for herself whether or not a motor vehicle was or was not in a reasonable condition, the respondents say that that is not a matter of fact within their knowledge. Two other matters are asserted by ASIC to which the respondents have pleaded the same response. The first is that Ms Kingsburra was not used to reading and understanding transactional documents relating to loans and purchases and second, she would require advice and explanations to be given in relation to the effect of commercial documents.

149 The respondents deny that Channic, by Mr Humphreys and/or Mr Hulbert, was aware of or believed that persons in the position of Ms Kingsburra were unlikely to be able to acquire a loan from any mainstream bank, building society or other similar financial institutions. The respondents admit that Channic, by Mr Humphreys or Mr Hulbert, held expertise in the selling of motor vehicles. The respondents deny that that they were aware that the vehicle being sold to Ms Kingsburra was worth substantially less than the amount which Ms Kingsburra had agreed to pay for it.

150 The respondents admit that the vehicle was sold by Supercheap to Ms Kingsburra for an amount of $8,990.00 in circumstances where Supercheap had acquired the vehicle for $500.00 and had expended $1,091.00 on reconditioning it, representing total expenditure by Supercheap of $1,591.00. Although the respondents admit those matters, they say that the overheads per vehicle sold by Supercheap were between $3,000.00 and $4,000.00.

151 The respondents deny that Channic was in a substantially superior bargaining position to Ms Kingsburra in the negotiation of the sale and purchase of motor vehicles and the financing of the purchase of a motor vehicle.

152 The respondents admit that on 13 July 2010, at the time when the Kingsburra loan was entered into, Mr Hulbert placed a 22 page document (as earlier described), the Kingsburra Loan Contract, in front of Ms Kingsburra. As to the notion that Mr Hulbert turned the pages of the document without giving Ms Kingsburra any proper opportunity to read any of the pages, Mr Hulbert admits that he turned the pages of the loan contract but denies that Ms Kingsburra was not given any proper opportunity to read any of the pages. Mr Hulbert further says that prior to turning the pages, he told Ms Kingsburra that she should read the loan contract and that she could read the loan contract at the premises (the first premises) or take the loan contract away from the premises to read. Mr Hulbert says that Ms Kingsburra declined, in the exercise of her free will, to read the document at the premises or elsewhere.

153 As to the notion that Mr Hulbert instructed Ms Kingsburra to initial the foot of each page of the contract (which she did), the respondents deny that any such instruction was given but say that the loan contract was offered to Ms Kingsburra (although at this point of the pleading there is a mistaken reference to Ms Harris) for her to initial each page and they admit that she did initial each page.

154 As to the notion that Mr Hulbert instructed Ms Kingsburra as to where to place her signature on pages 8, 9 and 22 (which she did), the respondents deny any such instruction and say that the loan contract was offered to Ms Kingsburra for her signature at those pages and she signed on those pages.

155 As to the notion that Mr Hulbert did not explain the document to Ms Kingsburra or did not fully explain it to her, the respondents deny that matter and say that Mr Hulbert referred Ms Kingsburra to the following matters contained within the loan contract: the amount of credit; the annual percentage rate; the amount of interest payable; the number of repayments; the amounts of repayments; the date of the first and last repayments; the frequency of the payments; the total amount of repayments; the comparison interest rate; the term of the loan; the amount of the brokerage fee; the amount of the “REVS” encumbrance fee; the amount of direct debit fees; the missed payment fee; the default notice fee; the debt recovery fee; the details as to the vehicle the subject of the loan; the “Important Note” to borrowers and the two “boxed” warnings to the borrower, immediately above the location for the borrowers and witness signature. Mr Hulbert pleads that he provided Ms Kingsburra with a summary of the key provisions of the loan contract and told her that if there was anything in the contract which she did not understand, it would be explained to her.

156 As to the notion that Mr Hulbert did not advise Ms Kingsburra to read the document or to seek legal advice in relation to it, the respondents deny that matter and Mr Hulbert pleads, again, that he advised Ms Kingsburra to read the loan contract and that he said she could read it at the premises or take it away to read but that Ms Kingsburra elected not to read the document at the premises or elsewhere. Mr Hulbert says that he told Ms Kingsburra that she should seek legal advice about the contents of the loan contract but that she declined to obtain such legal advice, in the exercise of her free will.

157 As to the notion that Mr Hulbert did not explain the interest rate of 48% per annum, did not identify the amount being borrowed, did not identify the total amount that would be repaid and did not identify an amount representing brokerage forming part of the loan, all such matters are denied.