FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Olympic Committee, Inc. v Telstra Corporation Limited [2016] FCA 857

Table of Corrections | |

2 August 2016 | Paragraph [22], eighth line – Amend to read “required to provide Telstra with an opportunity to “re-work”…” |

Paragraph [64], first to second line – Replace “Evidence was led by Telstra, in the form of documents subpoenaed from Seven, which demonstrate” with “Documentary evidence was led by Telstra, which demonstrated” | |

2 August 2016 | Paragraph [99], third line – replace “subpoena” with “notice” |

2 August 2016 | Paragraph [107], first line – replace “Telstra contended” with “The AOC contended” |

2 August 2016 | Paragraph [107], second line – replace “Telstra submitted” with “The AOC submitted” |

2 August 2016 | Paragraph [113], second line – replace “relied on by Telstra” with “relied on by the AOC” |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, INC. (ABN 33 052 258 241) Applicant | ||

AND: | TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED (ACN 051 775 556) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding, including any reserved costs, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WIGNEY J:

1 This matter concerns allegations of so-called “ambush marketing” against Telstra Corporation Limited. Those allegations arise out of various promotions and advertisements that are themed around the forthcoming 2016 Summer Olympic Games to be held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in August 2016.

2 For many years Telstra was a licenced “team sponsor” of the Olympic Games and was permitted to promote itself by association with the Australian Olympic Team and the Olympics. It no longer holds any such rights. It has, however, entered into an agreement with Seven Network (Operations) Ltd, pursuant to which it sponsors or is a “partner” of Seven’s Olympic broadcast.

3 Telstra has recently commenced an extensive marketing and advertising campaign which, on just about any view, is focused or themed around the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games. The applicant, the Australian Olympic Committee, seeks to halt that campaign. It contends that the promotions and advertisements contravene the Olympic Insignia Protection Act 1987 (Cth) and are misleading and deceptive contrary to s 18 and ss 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law. Telstra says, in effect, that there is nothing wrong with the campaign and refuses to halt it.

4 The central question in resolving this dispute is this: do the Telstra promotions and advertisements suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra is a sponsor of, or provided sponsor-like support to, bodies and teams associated with the Rio Olympic Games? Or do they simply suggest that Telstra sponsors Seven’s broadcast of the Rio Olympic Games and promote the ability of Telstra customers to access the premium version of Seven’s “Olympics on 7” app?

5 The AOC initially sought interlocutory injunctions restraining Telstra from running the promotions and campaigns. Sensibly, the parties ultimately sought and were granted an urgent final hearing. The case has been conducted and decided within a very short timeframe. These reasons should be read and understood in that context.

Facts

6 The main facts are not in dispute. The only real factual issue concerns whether the “supreme” governing body of the “Olympic Movement”, the International Olympic Committee, had effectively approved some of the terminology employed by Telstra in its campaign. Ultimately, however, the only real controversy is the scope and effect of the IOC approvals.

The Olympic Games and the “Olympic property”

7 The modern Summer Olympic Games are held every four years. They are probably the largest and most widely recognised and recognisable sporting event in the international sporting calendar. For better or for worse, they are also a very big business.

8 The Olympic Games and all associated intellectual property are owned by the IOC. So says the Olympic Charter, which is a form of constitution or statute of the Olympic Movement and the IOC. Amongst other things, the Olympic Charter codifies the rules and bye-laws adopted by the IOC and defines the main reciprocal rights and obligations of the IOC and the other constituents of the so-called Olympic Movement: the International Sports Federations and the National Olympic Committees.

9 The AOC is the National Olympic Committee for Australia. On a slightly more mundane level, the AOC is a non-profit association incorporated under the Associations Incorporation Act 1981 (Vic).

10 Fascinating as it may be, a discussion of the precise legal status of the Olympic Charter must await another day. It is common ground that the Olympic Charter relevantly defines the respective rights and obligations of the IOC and the AOC, as Australia’s National Olympic Committee, to use and protect property associated with the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement. The rights and obligations defined in the Olympic Charter are, of course, subject to Australia’s domestic laws. It is nevertheless relevant to consider certain provisions in the Olympic Charter. That is because, amongst other things, they put into context the various agreements that were entered into between the IOC and Seven, and Seven and Telstra, in relation to the Rio Olympic Games.

11 Rules 7 to 14 of the Olympic Charter deal with the rights over the Olympic Games and “Olympic properties”. Stripped of its loftier ideals and language, the rules relevantly provide as follows:

The IOC is the owner of all rights in and to the Olympic Games and Olympic properties, which rights have the potential to generate revenues (rule 7.1);

The rights relating to the Olympic Games relevantly include rights relating to the exploitation and marketing of the Olympic Games and the broadcasting, transmission, reproduction, display, dissemination, making available or otherwise communicating to the public of the Olympic Games (rule 7.2);

The Olympic properties (see rule 7.4) include the Olympic symbol (described in rule 7.8), the Olympic flag (described in rule 9), the Olympic motto (described in rule 10), the Olympic emblems (described in rule 11), the Olympic anthem (described in rule 12), the Olympic flame and torches (described in rule 13) and the Olympic designations, which include any visual or audio representation of any association, connection, or other link with the Olympic Games, the Olympic Movement, or any Constituent thereof (rule 14); and

All rights to the Olympic properties, as well as all rights to the use thereof, belong exclusively to the IOC, including the use for any profit-making, commercial and advertising purposes (rule 7.4).

12 The bye-laws to rules 7 to 14 (which concern the Olympic designations) relevantly provide (in simplified terms) as follows:

The IOC may take all appropriate steps to obtain the legal protection for itself, on both a national and international basis, of the rights over the Olympic Games and over any Olympic property (bye-law 1.1);

Each National Olympic Committee is responsible to the IOC for the observance, in its country, of rules 7 to 14 and the bye-laws to rules 7 to 14 and shall take steps to prohibit any use of the Olympic properties which would be contrary to those rules or bye-laws (bye-law 1.2);

Each National Olympic Committee should also endeavour to obtain, for the benefit of the IOC, protection of the Olympic properties (bye-law 1.2);

The Olympic properties may be exploited by the IOC in the country of a National Olympic Committee provided that, amongst other things, the relevant National Olympic Committee shall receive half of all net income from any such exploitation (bye-law 2.2); and

The IOC, in its sole discretion, may authorise the broadcasters of the Olympic Games to use, relevantly, the Olympic properties to promote the broadcasts (bye-law 2.3).

13 The IOC and, in Australia, the AOC have for many years entered into sponsorship and affiliation arrangements and agreements with national and multinational companies. There are many different levels and categories of sponsorships. The common feature is that, for varying levels of consideration, companies that enter into such sponsorship arrangements are generally able to promote themselves by association with the Olympic Games or teams participating in the Games. Sponsorship arrangements entered into by the AOC almost invariably include the grant of a licence to use Olympic designations or Olympic properties, including expressions such as “Olympic”, “Olympics” and “Olympic Games”.

14 As might be expected, both the IOC and the AOC earn significant revenue from such sponsorship and licencing arrangements. Equally unsurprisingly, they jealously protect their rights and the rights of their sponsors.

15 For many years, Telstra had been an Australian Olympic team sponsor in the telecommunications category. As part of that sponsorship arrangement, the AOC granted Telstra the exclusive rights in that category to promote itself by association with the Australian Olympic team and the AOC. Telstra was also licenced to use, in that context, Olympic properties, including expressions such as “Olympic”, “Olympics” and “Olympic Games”.

16 The sponsorship arrangements between the AOC and Telstra came to an end in 2012. Telstra no longer has any sponsorship or sponsorship-like arrangements with the AOC. Nor is it licenced to use, for promotional or commercial purposes, expressions such as “Olympic”, “Olympics” or “Olympic Games”. The AOC’s current sponsorship and licencing arrangements in the telecommunications category are with Telstra’s main competitor, Optus Mobile Pty Ltd. Those arrangements are applicable to promotions involving the Rio Olympic Games.

Agreements between the IOC and Seven, and between Seven and Telstra

17 On 26 June 2014, the IOC and Seven entered into an agreement in relation to broadcast rights which included the rights in relation to the Rio Olympic Games. Pursuant to that agreement, the IOC relevantly granted Seven the sole exclusive rights to broadcast and exhibit the Rio Olympic Games in Australia. The broadcast and exhibition rights included broadcast not only by television, but also broadcast by means of devices such as mobile phones and “tablet” devices.

18 Importantly, the terms of Seven’s agreement with the IOC also provided that Seven was permitted to commercially exploit its broadcast rights by, amongst other things, selling broadcast sponsorships and advertising in connection with the broadcast and exhibition of the Games. Seven was not permitted, however, to grant any of its broadcast sponsors the right to use Olympic properties, including the words “Olympic”, “Olympics” and “Olympic Games”, or any terms or expressions implying sponsorship of the Olympic Games for any purpose. Seven’s broadcast sponsors were, however, authorised to use phrases such as “[Seven’s] Olympic Games telecast is made possible/brought to you by [Seven’s] telecast sponsors/partners…” or any equivalent phrase approved in writing by the IOC.

19 In June 2016, Seven entered into an agreement with Telstra, pursuant to its rights under the agreement with the IOC, to sponsor Seven’s broadcast of the Rio Olympic Games. Under the agreement between Seven and Telstra, Telstra was entitled to use certain “designations”, as agreed by the parties and approved by the IOC, in its marketing, advertising and promotional material. The designations included “Seven’s Olympic Games broadcast is supported by Seven’s official technology partner, Telstra”.

20 Importantly, Seven’s agreement with Telstra also provided that Seven would provide “Premium Content” to eligible Telstra customers. Premium content included 36 additional “streams” of live events from the Rio Olympic Games via a website and a mobile phone and tablet application, or “app”, built and operated by Seven. Telstra agreed that any promotion or marketing by it of the availability of the premium content to its customers was governed by the “Term Sheet”.

21 The Term Sheet provided that Seven would build, fund, maintain, host and operate, relevantly, a Rio 2016 Olympic Games mobile and tablet app called “Olympics on 7”. The Olympics on 7 app housed both free and premium program content for the Rio Games. The free content was to be accessible by the general public regardless of their internet services provider. The premium content was also accessible by the general public, but only upon payment of a one-off access fee. Telstra mobile customers could access the premium content free of any transaction charge once they provided “authentication” details. Telstra was required to fund, build, host and maintain an authentication “landing page” on its website for that purpose.

22 The Term Sheet also contained provisions dealing with promotions. Amongst other things, Telstra was permitted to promote and advertise the Olympics on 7 app and the free premium content available to its customers. Telstra’s promotion and marketing of the Olympics on 7 app was, however, subject to prior approval by Seven. Perhaps more importantly, the Term Sheet provided that if Seven reasonably considered that it was required to seek IOC approval as a result of Telstra using “Olympic Indicia”, or if the overall impression was that Telstra was an official sponsor or affiliated with the Rio Games or the AOC/IOC, Seven was either required to provide Telstra with an opportunity to “re-work” the promotion or marketing to avoid the need for IOC approval, or promptly seek “consent” from the IOC.

23 As will be seen, there was evidence that Seven did seek and obtain the IOC’s approval or consent in relation to the form of Telstra’s proposed authentication “landing page” for the Olympic on 7 app. There was, however, nothing to suggest that Seven sought or obtained the IOC’s approval or consent in relation to the form or content of any other advertisement or promotion.

24 It is tolerably clear from these provisions in the Term Sheet that Telstra must have been well aware that there were limits or restrictions in relation to its advertising, marketing and promotion of the Olympics on 7 app. In particular, Telstra must have been aware that its advertisements, marketing and promotions could not represent, or convey the impression, that it was an official sponsor or affiliated with the Rio Games or the IOC or AOC, at least without the consent of the IOC.

Telstra’s Olympic marketing brief

25 That point was equally apparent from the documentary evidence concerning Telstra’s Olympics marketing brief or campaign. That evidence suggested that Telstra wanted to “use the partnership with Channel 7 to standout in the malaise of Olympic sponsors – when we’re not an Olympic sponsor (yet our major competitor is)?” Telstra wanted to “‘own’ an association with the Games”, but equally well knew that it had to do so “without implying any official association with the Olympics themselves”. Indeed, the marketing material revealed that Telstra knew well that the “Olympic don’ts” included, “Can’t say ‘Olympics’ ‘Games’ ‘Rio’ ‘Gold’ ‘Silver’ ‘Bronze’”.

26 In short, Telstra was well aware that, in exploiting its commercial arrangements with Seven, it had to walk a fine line. It could promote the fact that it sponsored, or was a partner of, Seven’s Olympic broadcast. It could not, however, suggest or imply that it sponsored, or was affiliated with any Olympic body. The critical question is whether any of Telstra’s advertisements, promotions or marketing material crossed that line.

The impugned advertisements and promotions

27 It was agreed between the parties that there were 34 separate types of advertisements, promotional or marketing communications or materials that fell within the terms of the AOC’s application for relief. It is possible to group those 34 separate items into seven categories: first, Telstra’s “Rio” television advertisements concerning access to Olympic coverage on mobile devices using the Telstra network; second, advertisements concerning a Samsung mobile phone promotion; third, videos available on third party websites concerning access to Olympic coverage on mobile devices via the Telstra network; fourth, Telstra catalogues that included promotions relating to access to Olympic coverage; fifth, Telstra’s authentication “landing page”; sixth, retail or point of sale material; and seventh, Telstra’s Keeping in Touch or “KIT” email, and other digital materials.

Telstra’s “Rio” television advertisements

28 There were three versions of Telstra’s television advertisement concerning the use of the Telstra network to watch the Rio Olympic Games on mobile devices. Each of them is 30 seconds long and involves the same images and the same musical soundtrack. The musical soundtrack is a version of Peter Allen’s well-known song “I Go to Rio”. The visual images include: a father and son driving in the country, the son watching what appears to be an Olympic gymnastics event on a mobile phone or tablet and then leaping a gate like a gymnast; rowers in a rowing shed watching an event on a mobile phone; children doing taekwondo and watching an event on a tablet device; girls watching soccer on a tablet before playing a game of soccer; and two elderly swimmers at an oceanside lap pool watching swimming on a mobile phone before swimming laps. In some instances the “7” logo appears on the mobile or tablet devices that are depicted advertisements.

29 There are some important differences between the three versions of the advertisements. Those differences mainly concern the content of the voiceover and the written messages or statements in the advertisement.

30 The first of the advertisements (the Rio TVC) has the following voiceover: “[t]his August, for the first time ever, watch every event in Rio live with the Olympics on 7 app and Telstra, on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. At one stage the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network” appear on the screen. Towards the end of the advertisement the Telstra logo and the words “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage” and “Olympics on 7” appear on the screen. The “7” is in the form of Seven’s fairly well-known logo.

31 Evidence led by Telstra showed that Seven sought the IOC’s consent to use the statement “Telstra … Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”. The IOC’s consent or approval was communicated to Seven in late May or early June 2016.

32 The facts agreed between Telstra and the AOC suggest that the Rio TVC was broadcast between 3 and 7 July 2016 and once by error on 8 July 2016. There is no suggestion that Telstra intends to re-broadcast this advertisement.

33 In the second advertisement (the revised Rio TVC) the voiceover is different. The voiceover is: “this August all Telstra mobile customers will have free premium access to every event live on Seven’s Olympics on 7 app. Enjoy the action on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. The other important difference is that for the first approximately 20 seconds of the advertisement the words “Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams” (the disclaimer) appear in fairly prominent white script at the bottom of the screen. After about 20 seconds the prominent words “Telstra is Seven’s broadcast partner” appear on the screen and the disclaimer disappears. Those words are then replaced by the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network”. At the foot of the screen the words “Based on national average mobile speeds” and “Data charges will apply” appear in script much the same size as the disclaimer.

34 The revised Rio TVC was broadcast from 6.00 pm on 11 July to the evening of 12 July 2016. There is no suggestion that Telstra intends to re-broadcast this advertisement.

35 The third version of the advertisement (the further revised Rio TVC) is very similar to the second. The only noticeable difference is that the disclaimer appears for approximately 27 seconds, almost the entire duration of the advertisement. It is only at the very end of the advertisement, when the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network” appear, that the disclaimer is replaced by the words “Based on national average mobile speeds. Data charges will apply”.

36 The further revised Rio TVC was broadcast from the evening of 12 July to 17 July 2016. It is also scheduled to be broadcast again from 31 July 2016.

The Telstra Samsung promotion advertisements

37 There are also three versions of Telstra’s television advertisement promoting a data plan referable to a particular Samsung mobile phone. Only the third version is intended to be re-broadcast.

38 The first version (the Telstra Samsung TVC) again has the “I Go to Rio” soundtrack. It includes some of the film images used in the Rio TVCs: the two rowers in a rowing shed watching a sporting event on a mobile phone before going for a row; and the two elderly swimmers watching a swimming race beside an oceanside swimming pool before swimming laps. The voiceover is in the following terms: “with Telstra, score a massive 10 gigs of data on the Samsung Galaxy S7, for just $95 a month for 24 months on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. The words displayed over the images at first state “10GB data for $95/mth for 24 months, includes 4GB bonus min. cost $2,280”, and then change to say “Australia’s fastest mobile network.”

39 It is notable that the Telstra Samsung TVC does not expressly refer to the Rio Olympics or the Olympic Games, either in the voiceover or the written messages. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the advertisement is Olympic themed. The “I Go to Rio” song is an obvious reference to the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games, particularly when accompanied by images of rowers and swimmers (albeit that the swimmers, at least, are obviously not Olympic swimmers) watching sporting events on a mobile phone.

40 This advertisement was broadcast between 3 July and 5:00 pm on 8 July 2016. It was also broadcast in four New South Wales and one Australian Capital Territory sports stadiums, during one netball and four rugby league games.

41 The second Telstra Samsung advertisement (the revised Telstra Samsung TVC) is essentially the same as the first. The only difference is that, for the first 7 seconds of the 15 second duration of the video, the disclaimer “Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams” appears at the foot of the screen in fairly prominent script.

42 The revised Telstra Samsung TVC was broadcast from 9 July to the evening of 12 July 2016.

43 The third Samsung advertisement (the further revised Telstra Samsung TVC) is the same as the second, other than that the disclaimer appears for slightly longer (11 seconds). This version was broadcast from the evening of 12 July to 17 July 2016 and is intended to be re-broadcast from 7 August 2016. It was also broadcast in two sports stadiums in New South Wales and Western Australian during four rugby league games.

Website videos

44 There are four versions of a video advertisement which was (and apparently still is) displayed on third party websites prior to the commencement of other video media.

45 The first version (the original soccer pre-roll) utilises the video images used in the Rio TVCs of the girls playing soccer and watching soccer on a mobile device. The soundtrack is the “I Go to Rio” song and the voiceover is the same as the original Rio TVC. The advertisement also uses the same written messages as the Rio TVC: “Australia’s fastest mobile network” and “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”.

46 This version of their website video was utilised during the period 3 to 7 July 2016.

47 The second version (the revised soccer pre-roll) is similar to the first. There are two main changes. First, the voiceover is changed to the voiceover used in the revised Rio TVC: “this August all Telstra mobile customers will have free premium access to every event live on Seven’s Olympics on Seven app. Enjoy the action on Australia’s fastest mobile network.” Second, the disclaimer appears at the foot of the screen during the first 11 seconds of the 15 second duration of the advertisement. This version first appeared on 13 July 2016 and is still utilised on various websites.

48 The third version (the original farm pre-roll) uses some of the same video images as the Rio TVC’s: the father and son driving in the country and the boy leaping a gate like a gymnast; and the children in a taekwondo class watching an event on a tablet. The voiceover is the same as the Rio TVC and original soccer pre-roll, as are the words displayed on the screen. Once again the “I Go to Rio” soundtrack is used. This version of the video was used between 3 and 7 July 2016.

49 The fourth version (the revised farm pre-roll) was modified in the same way that the revised soccer pre-roll was modified. The voiceover is the same as the revised Rio TVC and the disclaimer appears at the foot of the screen for the first 11 seconds of the advertisement. This version of the video was first utilised on 13 July and continues to be available on various websites.

Telstra catalogues

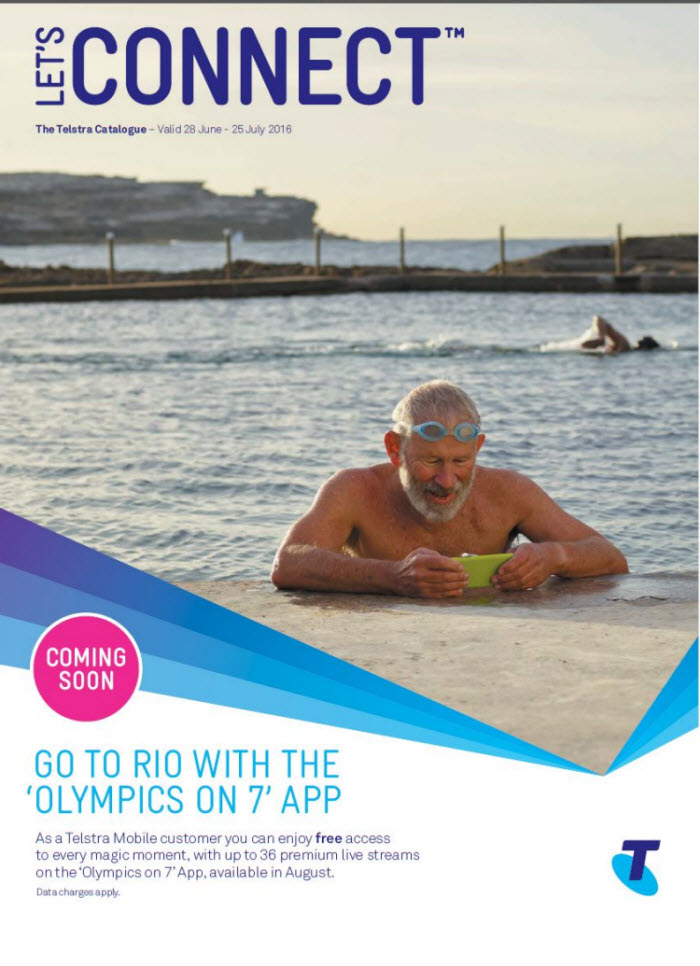

50 There are effectively two different catalogues that contain material challenged by the AOC.

51 The first was Telstra’s retail catalogue for July 2016. It was distributed in various ways from 28 June 2016. Telstra has advised that it cannot be withdrawn from distribution. A version of this catalogue was also distributed in National Broadcast Network (NBN) launch areas in early July 2016. It is apparently not intended to be redistributed.

52 The front cover of the July catalogue includes a photo image of one of the elderly swimmers featured in the Rio TVCs. He is leaning out of an oceanside pool and looking at a mobile device. The words “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” appear prominently. The following words then appear: “As a Telstra mobile customer you can enjoy free access to every magic moment with up to 36 premium live streams on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, available in August.”

53 A copy of this cover is annexed to these reasons.

54 On the second page inside the catalogue there is an image of young female soccer players grouped together looking at a tablet device. The words “catch every magic moment” appear in prominent script. The following words then appear:

For the first time ever, watch every goal scored, every record broken and every medal won.

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, you can catch more of the action than ever before, with premium access to up to 36 live streams of Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games.

And as a Telstra Mobile customer, you’ll get premium access for free!

So get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App and go to Rio this August.

To find out more go to telstra.com/7rio

Data charges apply.

55 The second catalogue is Telstra’s retail August catalogue. It has been distributed in various ways since 26 July 2016. It may be inferred that it cannot be recalled. On the sixth page of the catalogue there is a full page image of a taekwondo instructor with a number of children wearing taekwondo outfits. The instructor is holding a tablet device which he and the children appear to be watching. In the top left hand corner the following words appear in prominent script, “Go to Rio, free” followed by smaller script, “Every Telstra Mobile customer can go to Rio with free premium access”. In a box in the bottom left hand corner the following appears:

There’s never been a better time to connect to Australia’s best mobile network, you’ll be sure to get the most from your new phone.

‘Olympics on 7’ App

Watch every sport and every game live from Seven’s coverage of Rio. Telstra Mobile customers can catch every magic moment with free premium access to up to 36 live streams on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App.

Download 1 August 2016.

Find out more at telstra.com/7rio

Data charges apply.

Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams.

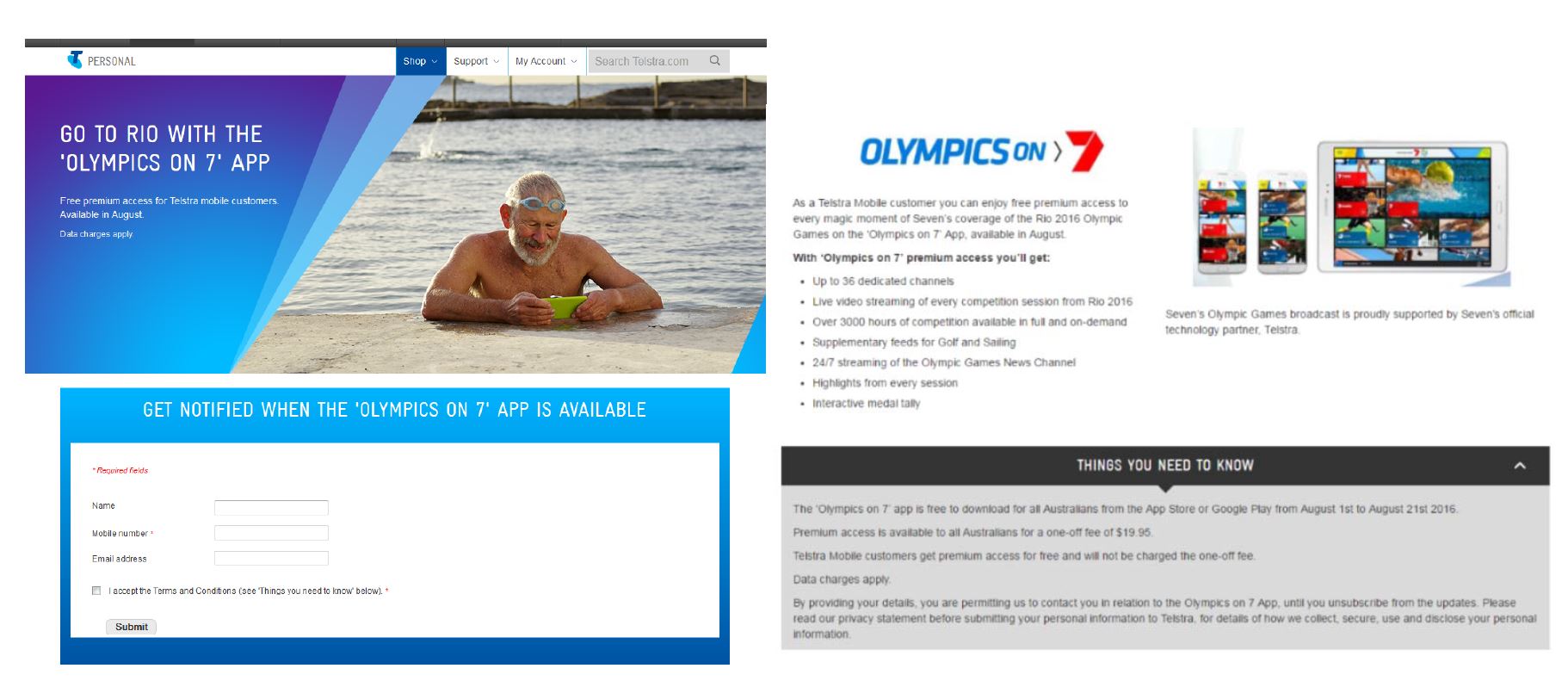

Telstra’s authentication “landing page”

56 It will be recalled that under the terms of its agreement with Seven, Telstra was required to set-up an “authentication” website landing page. On that page, persons who were confirmed as Telstra subscribers or customers could sign up for premium access to Seven’s Olympics on 7 app.

57 Three versions of the landing page were set up by Telstra. The first version was accessible on Telstra’s website for the period 28 June 2016 to 7 July 2116. That page included a prominent image of the elderly swimmer looking at his mobile device poolside adjacent to the prominent script: “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” followed by the words, in smaller script: “Free premium access for Telstra mobile customers”.

58 The page also included a prominent graphic of the words “Olympics on ›7” utilising Seven’s “7” logo. Under that graphic the following words appear:

As a Telstra Mobile customer you can enjoy free premium access to every magic moment of Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, available in August.

With ‘Olympics on 7’ premium access you’ll get:

• Up to 36 dedicated channels

• Live video streaming of every competition session from Rio 2016

• Over 3000 hours of competition available in full and on-demand

• Supplementary feeds for Golf and Sailing

• 24/7 streaming of the Olympic Games News Channel

• Highlights from every session

• Interactive medal tally

59 Adjacent to those images there are images of two mobile phones and a tablet device containing what appear to be images of Olympic athletes or events. Under those images the followings words appear: “Seven’s Olympic Games Broadcast is proudly supported by Seven’s official technology partner, Telstra”.

60 Under the banner “Things you need to know” the following writing appears:

The ‘Olympics on 7’ app is free to download for all Australians from the App Store or Google Play from August 1st to August 21st 2016.

Premium access is available to all Australians for a one off fee of $19.95.

Telstra Mobile customers get premium access for free and will not be charged the one off fee.

Data charges apply.

By providing your details, you are permitting us to contact you in relation to the Olympics on 7 App, until you unsubscribe from the updates. Please read our privacy statement before submitting your personal information to Telstra, for details of how we collect, secure, use and disclose your personal information.

61 An image of the original landing page is annexed to these reasons.

62 On 7 July 2016, the content of the landing page was changed in two ways. First, the position of the “Olympics on 7” graphic was moved so it appeared under the images of a mobile phone (now only one) and tablet. Second, the words that originally appeared under those images no longer appear. Instead, the disclaimer, in reasonably prominent script, appears under the ‘Olympics on 7’ graphic. This version of the landing page remained available until 12 July 2016.

63 On 12 July 2016, the landing page was changed again, albeit in a fairly minor way. In this version, which is the current version, the disclaimer appears in two places. It appears under the prominent script “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App”, as well as immediately above the “Things you need to know” banner. An image of the current version of the landing page is annexed to these reasons.

64 Documentary evidence was led by Telstra, which demonstrated that the IOC had approved an earlier “mock” version of the landing page. That version did not contain the image of the swimmer. It did, however, include virtually all of the written content of the original version of the page that was available on Telstra’s website from 7 July. It did not include the disclaimer. The evidence demonstrated that the mock webpage was submitted to the IOC by Seven on 16 June 2016 and was approved by the IOC, subject to minor and, for the purposes of this proceeding, immaterial provisos, on 23 June 2016.

Retail point of sale materials

65 The retail point of sale materials appeared at various times from 28 June 2016 in certain Telstra branded stores and Telstra third party dealer stores. It comprised digital menu boards and media fountains, A4 posters, A5 tear pads and other materials. It is unnecessary to detail these items at length.

66 The common features of this material include: still images of the elderly swimmer or taekwondo class or young female soccer players taken from the Rio TVCs or website material; the words “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and variations of the written message that Telstra mobile customers were able to get free access to the Olympics on 7 app containing live streams of Seven’s Coverage of the Rio Olympic Games. From 26 July 2016, all of the materials have included the disclaimer in fairly prominent script.

Other digital materials

67 The agreed facts included seven additional samples of digital materials that either appeared on third party websites or were emailed to Telstra mobile or Telstra business customers. It is unnecessary to detail all of those items. In its submissions, the AOC focused on only two.

68 On 1 July 2016, Telstra consumer mobile customers were sent a “KIT” (Keeping in Touch) email. It included the following introductory words:

For the first time ever, watch every minute of every event live from Seven’s Coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. With free premium access to up to 36 live streams of the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, you won’t miss any of the action. Data charges will apply.

69 The email then featured the image of the taekwondo class, the headline words “Get free premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and then the following written detail:

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, you can catch more of the action than ever before. And as a Telstra mobile customer you’ll get premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App for free, so you can cheer on your heroes right in the palm of your hand.

Get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App this August. Data charges will apply.

70 On 30 June 2016 eligible Telstra business customers were sent a “Business ideas e-newsletter”. One page of the newsletter featured an image of a tradesman viewing a tablet device alongside the heading “Get free premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and then the following words:

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, Telstra mobile customers can catch more of the action than ever before. Sign up for an eligible service and [you’ll] get premium access for free, letting you cheer on your heroes and watch records tumble, right in the palm of your hand. Get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App and go to Rio this August.

(emphasis in original)

The Olympic Insignia Protection Act Claim

71 The AOC contended that each of the Telstra advertisements, promotions or marketing, with the exception of the Telstra Samsung TVCs, contravened s 36 of the Olympic Insignia Protection Act, or OIP Act.

72 Section 36 of the OIP Act provides as follows:

(1) A person, other than the AOC, must not use a protected olympic expression for commercial purposes.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply to the use by a person of a protected olympic expression if:

(a) the person is a licensed user; and

(b) the protected olympic expression is an expression that the person is licensed to use; and

(c) that use is in accordance with the terms and conditions of the licence.

73 Section 24 provides that, relevantly, each of the words “Olympic”, “Olympics” and “Olympic Games” are protected Olympic expressions.

74 Sections 23 and 38 provide, in effect, that a licence for the purpose of s 36 is a licence granted by the AOC to a person to use all, or any one or more, of the protected Olympic expressions. The AOC is to maintain a register of licences. Section 23 provides that a licenced user means a person in relation to whom a licence is in force.

75 There is no dispute that the AOC did not issue a licence to Telstra to use any of the Olympic expressions during the time that any of the relevant advertisements, promotions or marketing materials were broadcast or otherwise made available. At no relevant time was Telstra a licenced user for the purposes of the OIP Act. Telstra advanced an argument that it was effectively licenced to use the Olympic expressions based on the IOC’s approval or consent of the “mock” Telstra website. That argument is addressed later.

76 Section 30 of the OIP Act sets out two situations in which a person is said to use a protected Olympic expression for commercial purposes. Only the first situation, which is set out in s 30(2), appears to be relevant to Telstra’s advertisements, promotions and marketing. Section 30(2) provides as follows:

(2) For the purposes of this Chapter, if:

(a) a person (the first person) causes a protected olympic expression to be applied to goods or services of the first person; and

(b) the application is for advertising or promotional purposes, or is likely to enhance the demand for the goods or services; and

(c) the application, to a reasonable person, would suggest that the first person is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for:

(i) the AOC; or

(ii) the IOC; or

(iii) a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(iv) the organising committee for a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(v) an Australian Olympic team; or

(vi) a section of an Australian Olympic team; or

(vii) an individual member of an Australian Olympic team;

then:

(d) if the expression is applied in Australia—the application is use by the first person of the expression for commercial purposes; or

(e) if:

(i) the expression is applied to goods outside Australia; and

(ii) the goods are imported into Australia for the purpose of sale or distribution; and

(iii) there is a designated owner of the goods;

the importation is use by the designated owner of the expression for commercial purposes.

77 Section 28 relevantly provides that an expression is taken to be applied to services if the expression is used in an advertisement that promotes the services, or in a catalogue, brochure, business letter, business paper or other commercial document that relates to the services.

78 Section 29 defines “sponsorship-like support” in the following terms:

(1) For the purposes of this Chapter, a person provides sponsorship-like support for:

(a) the AOC; or

(b) the IOC; or

(c) a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(d) the organising committee for a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(e) an Australian Olympic team; or

(f) a section of an Australian Olympic team; or

(g) an individual member of an Australian Olympic team;

if, and only if, the person provides support on the understanding (whether express or implied) that the support is provided in exchange for a right to associate:

(h) the person; or

(i) goods or services of the person;

with the committee, games, team, section or individual concerned.

(2) A right mentioned in subsection (1) need not be legally enforceable.

(3) An exchange mentioned in subsection (1) may be wholly or partly for the right mentioned in that subsection.

79 There was essentially no dispute that Telstra applied Olympic expressions (“Olympic”, “Olympics”, and “Olympic Games”) to its services within the meaning of s 28 of the OIP Act. Nor was there any apparent dispute that the relevant applications of the Olympic expressions were for advertising or promotional purposes, or were likely to enhance the demand for Telstra’s services. The relevant services were, in broad terms, Telstra’s telecommunications services.

80 The real question is whether, in each case, the application of the expression or expressions “to a reasonable person, would suggest that [Telstra] is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for”, relevantly, the AOC, IOC, the Rio Olympic Games or the Australian Olympic team or any section or member of it. That question involves an objective test. The question is what the application of the Olympic expressions would suggest to a reasonable person. The word “suggest” must bear its ordinary meaning, which includes, in this context, to “bring before a person’s mind indirectly or without plain expression; to call up in the mind (another thing) through association or connection of ideas” (Macquarie Dictionary); and “make known indirectly; hint at, intimate; imply, give the impression” (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary). The relevant application must be considered in the context of the relevant advertisement catalogue, brochure or commercial document to which it is applied.

81 There is little point in over-intellectualising the relevant test, or putting a gloss on it by employing essentially synonymous expressions. Indeed, that would be a distraction. Nor is there any basis or warrant for reading into the relevant test other requirements or elements drawn from, for example, the jurisprudence concerning misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law.

82 Equally, there is nothing to be gained from having regard to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Act that inserted s 36 and associated provisions into the OIP Act. The Explanatory Memorandum said that the new provisions were intended to combat so-called “ambush marketing”. That expression is a distraction. At the end of the day the statutory test is quite clear. It is simply a matter for the Court to make a factual finding concerning what the relevant application of the Olympic expression would, in context and in all the relevant circumstances, suggest to a reasonable person. The question of what would be suggested to a “reasonable” person necessarily involves a value or normative judgment about which there may well be legitimate differences of opinion. That is particularly so given that the question of what may or may not be suggested by a combination of images and words, and in some cases sounds, is inherently impressionistic.

83 Before addressing or applying the “reasonable person” test to each of the relevant advertisements, it is necessary to first address Telstra’s submission based on the IOC’s approval of Telstra’s webpage.

IOC approval

84 Telstra contended that the evidence showed that it had been a party to “an authorisation, licencing and/or approval arrangement with the IOC”. This, Telstra contended, provided a complete answer to the AOC’s claims, including the claim under the OIP Act. Telstra contended that since the alleged affiliation between Telstra and the IOC, AOC or other Olympic body had been authorised, any suggestion of the affiliation would not be misleading.

85 There are two answers to that submission. First, the evidence did not go so far as establishing that Telstra was a party to an authorisation, licencing and/or approval arrangement with the IOC. It was Seven that sought and obtained the IOC approval, as it was required to do pursuant to its contract with the IOC. Telstra was not relevantly a party to the approval. The approval was also only in respect of the landing page. It did not cover or relate to the advertisements or other marketing and promotional material. It did not extend to the approval of any words or expressions used in different contexts.

86 Second, and more fundamentally for the purposes of the OIP claim, even if Telstra was a party to any such arrangement with the IOC, it does not follow that it had acquired a licence from the AOC for the purposes of the OIP Act. Whatever the IOC may have approved, it did not amount to a licence from the AOC to use any of the Olympic expressions (ss 23 and 38 of the OIP Act) and Telstra was not a licenced user (s 23) for the purposes of s 36 of the OIP Act. Any authorisation by the IOC was essentially irrelevant to whether Telstra’s applications of the Olympic expressions were for commercial purposes.

The Rio TVC

87 The following points may immediately be made in relation to the Rio TVC. While the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games undoubtedly provided the underlying broad theme or story of the advertisement, the advertisement itself makes no express mention or reference to the IOC, AOC or the Australian Olympic Team or any section or member of it, let alone any express reference to any sponsorship or sponsorship-like association between Telstra and any of those bodies. No current or former Olympic athletes appear in the advertisements. The advertisements do not include any image of the Olympic symbol, flag or emblem. The word “Olympics” is used twice: once in the voiceover as part of the expression “Olympics on 7 App”; and once in writing, again as part of the expression “Olympics on 7”. The expression “Olympic Games” is used once in the context of the phrase “Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”.

88 The more specific theme or story of the advertisement concerns everyday Australians involved in sport watching Rio Olympic events on a mobile phone or tablet. The broad message is that events at the Rio Olympics can be watched live on such devices using the Telstra network. The hypothetical reasonable person may be taken to know that media and telecommunications companies ordinarily cannot broadcast live sporting events unless they have somehow paid for the rights to broadcast the event. Does the advertisement thereby suggest to the reasonable person that Telstra had some form of sponsorship-like arrangement with the IOC, AOC, or some other Olympic body?

89 The AOC contended that the Rio TVC would suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra had some form of endorsement or approval of, or some form of sponsorship, affiliation, licencing or other sponsorship-like arrangement with the Olympics. It contended that it was necessary to consider the general thrust of Telstra’s overall campaign. The advertisements also needed to be considered in the context of other surrounding facts and circumstances. Those surrounding facts and circumstances included: Telstra’s association with Seven, the official Olympic broadcaster; advertisements broadcast by Seven that refer to Telstra as Seven’s “Technology Partner”; and the fact that Telstra was the Australian Olympic Team’s sponsor for many years in respect of prior Olympic Games.

90 Telstra contended that the Rio TVC’s did no more than convey that Telstra had a sponsorship-like relationship with Seven, which in turn held the broadcasting rights in relation to the Rio Games. Telstra emphasised that the words “Olympics” and “Olympic Games” are only used in the context of a compound verbal expression or compound written expression linked with Seven or Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games. No Olympic symbols or emblems are employed in the advertisement.

91 The critical question in relation to the advertisement is whether it makes it sufficiently clear that Telstra’s sponsorship-like arrangement is with Seven, not any Olympic body. Does it make it sufficiently clear that Telstra customers can watch the Rio Games on their mobile devices using the Telstra network because Telstra is Seven’s partner or sponsor, not because it has any arrangement with any Olympic body?

92 The original Rio TVC is somewhat borderline in that regard. The voiceover refers to watching Rio events live with the “Olympics on 7 App and Telstra”. The hypothetical reasonable person cannot necessarily be taken to know that the Olympics on 7 app was an app owned by Seven through which Seven was licenced or authorised to broadcast its coverage of the Rio Games. The immediate use of the words “and Telstra” after the reference to the Olympics on 7 app tends to suggest that Telstra had some connection or involvement with the app. There was, therefore, a degree of ambiguity, or at least a lack of clarity, concerning Telstra’s connection with the app and the Olympic broadcast available on it.

93 The nature of Telstra’s connection with the app and the Olympic Games broadcast is, however, clarified to an extent in the last few seconds of the advertisement. That is when the words “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage” and “Olympics on 7”, using Seven’s logo, appear. Those words tend to suggest that Telstra’s relationship in relation to the broadcast is with Seven, not any Olympic body.

94 Whilst the original Rio TVC is perhaps borderline, on balance it does not cross the line and suggest that Telstra was a sponsor of the Olympics or any Olympic body. While there is a degree of ambiguity concerning Telstra’s connection to the broadcast rights, it cannot be considered, on the balance of probabilities, that the use of the Olympic expressions would suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor, or was the provider of sponsor-like support to any Olympic body. What ultimately was suggested was that Telstra sponsored (or was a partner of) Seven’s coverage and that Seven’s coverage could be accessed on Seven’s app using the Telstra network.

95 It should be added that it is doubtful that it is relevant, as the AOC contended, to consider the advertisements in the much broader context of Telstra’s overall campaign, or Seven’s own advertisements, or facts such as Telstra’s past formal sponsorship of the Australian Olympic Team. It is doubtful that the hypothetical reasonable person would necessarily know about, or recollect, Telstra’s previous sponsorship of the Australian Olympic Team, let alone turn his or her mind to that fact when viewing the commercial. As for Seven’s advertisements, if anything, they simply confirm that Telstra’s sponsorship arrangement is with Seven. That would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra also sponsored an Olympic body.

96 Two other categories of evidence relied on by the AOC should also briefly be addressed. First, the AOC relied on internal Telstra marketing and promotions material, including a marketing brief and a “Rio Games creative brief”. Those documents plainly reveal that Telstra intended to exploit its commercial agreement with Seven as a way of associating itself, for marketing purposes, with the Olympic Games. The AOC submitted, in effect, that those documents effectively demonstrated that Telstra intended that its marketing and advertisements would suggest a sponsorship-like arrangement with the IOC, AOC or other Olympic bodies.

97 It might well be the case that evidence of a party’s intention to employ an Olympic expression to convey to the public that it had a sponsorship-like arrangement with an Olympic body could be relevant in determining whether the use of the expression would suggest that connection to a reasonable person. That is not to say that intention is a necessary element in proving a contravention of s 36 of the OIP Act. Rather, as is the case with misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law (considered in more detail later), proof of an intention to convey an impression may make it easier to find that the impression was in fact conveyed.

98 In any event, the marketing material does not clearly show an intention on the part of Telstra to suggest that it had a sponsorship-like relationship with the Olympics. It is probably best to be wary about reading too much into marketing-speak used by “creative agencies”. Nevertheless, the marketing brief revealed that Telstra wanted to be associated in some way with the Olympics: it wanted to create an overarching “brand idea” and “platform that brings to life Telstra’s brand positioning of ‘empowering people to thrive in the connected world’ through the context of sports and the Olympic [G]ames” (whatever that may mean). Telstra also wanted to “own an association with the Games”. Equally, however, the material revealed that Telstra well understood that, because it was not a sponsor, there were limits to what it could say or imply. The challenge of the brief was to “utilise our entitlements [arising from the agreement with Seven] without implying any official association with the Olympics themselves”. On balance, the marketing material does not show that Telstra deliberately set about implying something which it knew it could not lawfully imply. It is fairly clear, however, that Telstra wished to push the envelope as far as it could.

99 The second category of evidence that the AOC relied on, or sought to rely on, was characterised by Telstra as being some sort of “survey” evidence. In fact, it comprised a business record, which Telstra produced on notice, that appeared to record the responses of eight consumers, categorised by reference to their age and family circumstances (“Gen X” or “Gen Y”; “older fam”, “younger fam” or “DINKS”), to questions about some of Telstra’s advertisements. Telstra objected to the tender of the document on the ground that it was irrelevant.

100 The document is relevant, although only marginally so. Evidence which tended to show that Telstra advertisements using protected Olympic expressions in fact led some consumers to believe that Telstra was in a sponsorship-like relationship with an Olympic body or bodies might be relevant to the question whether the advertisements transgressed the objective test in ss 30 and 36 of the OIP Act: that the advertisements would suggest a sponsor or sponsorship-like connection to a reasonable person. That is not to say that proof that consumers were relevantly misled is necessarily an element in proving a contravention of s 36 of the OIP Act. The situation is again somewhat analogous to an action under s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law where (as discussed later) proof that consumers were actually misled or deceived is not necessary, but may nonetheless be relevant.

101 The survey-like evidence, however, is deserving of little weight in all the circumstances. The main difficulty is that it is unclear exactly what advertisements the interviewees were shown and asked to comment on. It is also unclear exactly what questions, and what other information, if any, was provided to the interviewees or what assumptions they were asked to make.

102 In any event, only one of the eight interviewees indicated that the advertisement that they were shown suggested to them that there might have been some sponsorship-like arrangement between Telstra and the Olympic Games. That interviewee said: “you can watch the games with Telstra, maybe they are a sponsor of the Olympic Games or something”. The same interviewee also said: “I think you have to see it a few times before you understand what it is” and “the 7 app is there, maybe it goes to their website, I didn’t understand the connection to be honest”. Those responses tended to show, at most, a degree of confusion on the part of the interviewee. They were far from emphatic and did not significantly advance the AOC’s case. Perhaps more significantly, while the other seven interviewees plainly saw the advertisement as indicating that they could watch the Olympics using the Telstra network, none said that they inferred that Telstra must therefore have been a sponsor of the Olympics.

103 On balance, the marketing evidence and the supposed survey evidence is of little weight in determining whether the Rio TVC contravened s 36 of the OIP Act. There could be little doubt that Telstra’s marketers intended that the campaign, including the Rio TVC, would convey an association of sorts between Telstra and the Rio Olympic Games. In all the circumstances, however, the association conveyed is ultimately an association between Telstra and Seven’s Olympic Games broadcast and Olympic Games app, rather than an association with any Olympic body or team. The conclusion remains that the Rio TVC would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor of, or provided sponsorship-like support to, any Olympic body.

The revised Rio TVC

104 While the original Rio TVC was perhaps borderline, the position is somewhat clearer in relation to the revised and further revised Rio TVCs. That is the case for three reasons.

105 First, the revised voiceover in those advertisements makes the association between Telstra and the Olympic telecast that can be viewed via the mobile network much clearer. It is made tolerably clear that the broadcast is made available on “Seven’s Olympics on 7 App”. It is thus made clear that it is Seven’s Olympic broadcast and Seven’s app.

106 Second, the disclaimer appears in relevantly prominent script for the majority of the duration of the advertisements. The disclaimer makes it clear that Telstra is not an official sponsor of any Olympic body. As discussed in slightly more detail later in the context of Telstra’s Australian Consumer Law case, a disclaimer will not necessarily erase or reverse what is or may otherwise be a misleading or deceptive message conveyed by an advertisement, particularly a television commercial. Nevertheless, in determining whether the advertisement would convey the impugned suggestion to a reasonable person, the entire advertisement must be viewed as a whole. That includes the disclaimer.

107 The AOC contended that the disclaimer was inadequate because it said only that Telstra was not an “official” sponsor. The AOC submitted that the limitation to disclaiming an “official” Olympic sponsorship “begs the question” and in fact reinforced the notion that there was or may have been some other type of sponsorship arrangement. It is, however, doubtful in all the circumstances that the hypothetical reasonable person would necessarily react to or interpret the disclaimer in that way. While it may be accepted that a reasonable person would be aware that there are many different types and levels of sponsorship, it is doubtful that, having seen the disclaimer, a reasonable person would think that Telstra might nonetheless have some sort of “unofficial” sponsorship. Indeed, it is somewhat difficult to imagine any meaningful form of unofficial sponsorship that might realistically exist in this context. It should also be noted that, when the AOC issued a statement concerning the Telstra advertisements, it too used the word “official” in describing what Telstra was not. The statement relevantly said: “To be clear, Telstra is not a sponsor of Australia’s Olympic Team and has no official role with the Olympic Movement” (emphasis added).

108 It might be accepted that the disclaimer would have been clearer in the circumstances if it did not use the word “official”. Read in context, and in all the circumstances, however, the disclaimer was capable of reversing or erasing any impression that might otherwise have been conveyed by the advertisement that Telstra was a sponsor of, or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for any Olympic body.

109 Third, the written message concerning Telstra’s connection with the broadcast is simplified and made clearer. It is simply said that “Telstra is Seven’s broadcast partner”. Thus, it is made tolerably clear (particularly when this is read in the context of the revised voiceover and disclaimer) that the Olympic coverage is able to viewed using Telstra’s mobile network because customers can access Seven’s app which carries Seven’s broadcast. Telstra’s sponsorship-like support is to Seven, not any Olympic body.

110 In all the circumstances, including the contextual facts and circumstances considered in the context of the original Rio TVC, it cannot be concluded that the revised Rio TVCs (to which Olympic expressions were applied) would suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of, sponsorship-like support for any Olympic body.

Website videos

111 The findings that have been made in relation to the Rio TVC and revised and further revised TVCs apply equally to the website videos. The original soccer pre-roll and the original farm pre-roll videos convey very similar messages to the original Rio TVC. They employ the same soundtrack, imagery, voiceover and written messages. Like the original Rio TVC, these videos are borderline in terms of whether they would suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor of, or provided sponsor-like support to any Olympic body. On balance, however, for essentially the same reasons as those given in relation to the Rio TVCs, it cannot be concluded to the requisite standard that they would.

112 The position is again clearer in relation to the revised versions of these videos. Like the revised Rio TVCs, those videos employ voiceovers and written messages that spell out the relationship between Telstra, Seven and Seven’s Olympic broadcast in much clearer terms. They also include the disclaimer in prominent script. In all the circumstances it could not be concluded that the videos would suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of, sponsorship-like support for any relevant Olympic body.

113 It should be noted that in reaching these findings regard has again been had to the broader contextual facts and circumstances relied on by the AOC. That includes the broader Telstra campaign and the marketing and survey materials.

114 It is clear that, through these videos Telstra sought to connect itself with, and derive some marketing benefit from, the Olympic Games. It did so, however, by connecting itself with Seven’s coverage of the Games and Seven’s app. It did not go so far as to suggest any sponsorship-like relationship with any Olympic body.

Telstra catalogues

115 As with the Rio TVCs, it is again noteworthy that the Telstra catalogues only employ the protected Olympic expressions in the context of either Seven’s app or Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games. The word “Olympics” is used twice, both times as part of the expression “Olympics on 7 App”. The word “Olympic” is used once in the context of the phrase “Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games”.

116 The front cover of the July catalogue refers to the Olympics on 7 app without any real explanation. On the second page, however, it is made tolerably clear that the Olympics on 7 app is simply a means of accessing Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games, and that Telstra customers are able to get premium access to the app for free. That would not convey to a reasonable person that Telstra customers were able to get access to the app, or the broadcast, because of some sponsorship-like association between Telstra and any Olympic body. Rather, at most it would suggest that Telstra customers could get access because of an arrangement between Telstra and Seven. The position is even clearer in the August catalogue, which prominently includes the disclaimer.

117 In all the circumstances, the application or use of the protected Olympic expressions in the Telstra catalogues would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor of, or provided sponsorship-like support to, any Olympic body.

Telstra’s authentication “landing page”

118 The findings that have been made in relation to the Telstra catalogues apply equally to the landing page. The protected Olympic expressions are, in each case, employed as part of, or in the context of, the Olympics on 7 app or Seven’s Olympic Games coverage. Read and viewed as a whole, the landing page conveys in sufficiently clear terms that the Olympics on 7 app is Seven’s app and contains Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games. Telstra customers can access Seven’s app and Seven’s coverage because Seven’s broadcast is “supported” by Telstra. The message conveyed is that Telstra’s sponsorship-like support is to Seven and Seven’s Rio Games coverage, not to any Olympic body.

119 That position is made even clearer in the later iterations of the landing page, which include the disclaimer in prominent script.

120 In all the circumstances, it is unnecessary to consider the implications, if any, of the fact that Seven had procured the IOC’s approval of the substantive content of Telstra’s landing page. On one view, the fact that the IOC did not see any issue with the content of the page might support the conclusion that the page would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra provided sponsorship-like support to any Olympic body. Surely if it did, the IOC would not have approved the page and would have drawn this to Seven’s attention.

121 In any event, putting aside the IOC’s approval of the page, in all the circumstances it cannot be concluded that the landing page conveyed the impugned suggestion. It would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra provided sponsorship-like support to any Olympic body.

Point of sale and other digital material

122 It is unnecessary to deal separately, or in any detail, with each of the retail point of sale and other digital materials. The considerations that have been referred to and discussed earlier in the context of the television advertisements, website videos, catalogues and the landing page apply equally to all items in these categories. The findings that have already been made apply to these items.

123 These materials would suggest to a reasonable person no more than the fact that Telstra’s customers can get free access to the Seven’s coverage of the Rio Olympic Games on their mobile devices via the Olympics on 7 app. In conveying that message Telstra no doubt intended to capitalise on, or exploit, in a marketing sense, the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games. It does not follow that these materials suggest that Telstra has a sponsorship-like arrangement with any Olympic body. They do not.

Conclusion in relation to the AOC’s OIP Act claim

124 The AOC has not proved, on the balance of probabilities, that Telstra contravened s 36 of the OIP Act. None of the advertisements, videos, catalogues, emails or online materials, or other marketing or promotional materials that employ the Olympic expressions would suggest to a reasonable person, that Telstra is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of, sponsorship-like support to any relevant Olympic body.

The AOC’s Australian consumer LAW claim

125 The AOC contended that Telstra’s advertisements and other marketing or promotional materials, considered individually or collectively, conveyed a false or misleading representation, or involved misleading or deceptive conduct. As a result, the AOC alleged that Telstra contravened either or both of s 18 or ss 29(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law.

126 Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law provides as follows:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

127 Section 29(1)(g) and (h) is in the following terms:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation; or

128 The AOC’s case that Telstra breached either or both of s 18 or ss 29(g) or (h) of the Australian Consumer Law was, in many respects very similar to its case based on the OIP Act. It hinged on the proposition that the relevant advertisements, marketing or promotional material, either individually or together, conveyed a representation, or had a tendency to lead the audience of that material to assume, that Telstra (or its services) had some form of endorsement, approval sponsorship, affiliation, or licencing arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games, the AOC, the IOC, the Australian Olympic team or the Olympic Movement generally.

129 Telstra did not suggest that the advertisements, marketing and promotions were engaged in otherwise than in trade or commerce. Nor was there any material dispute that any representation that may be found to have been made in or by the advertisements, marketing or promotional material, was relevantly connected with the promotion of services supplied by Telstra. The issue was whether, viewed individually or collectively, the advertisements, marketing or promotions conveyed the alleged representation. More fundamentally, there was also essentially no dispute that if the alleged representation was conveyed, or if the advertisements, marketing and promotions led consumers to assume that Telstra or its services were somehow endorsed, sponsored or affiliated with the Olympics as alleged, it would be a false or misleading representation, or constitute misleading or deceptive conduct. Telstra plainly had no sponsorship or affiliation with any Olympic body. Nor were its services approved or endorsed by any relevant Olympic body.

Relevant principles

130 The applicable principles in relation to actions for misleading or deceptive representations or conduct under s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law or cognate provisions are well settled and well-known. The parties were in furious agreement about those principles. The real issue in this matter is the application of those principles to the facts and circumstances of the case.

131 It is accordingly unnecessary to discuss the relevant principles in any great detail. Nor is it necessary to recite a long list of cases as authority for the various principles. The leading authorities are well known. It must also be said that many of the principles concerning misleading and deceptive conduct that are discussed in the authorities are really just common-sense or logical guides to the approach that should be taken in deciding what is, at the end of the day, a question of fact.

132 The principles relevant to the resolution of this matter may be summarised in simple terms as follows:

Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law is not limited to misleading and deceptive representations. The question is whether the respondent’s conduct, which may include acts, omissions, statements or silence, is misleading or likely to mislead or deceive: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 655 [49] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

Conduct is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead a person into error, or to believe what is in fact false. Conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility that it will have that effect: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87-88. It is insufficient for the impugned conduct to only cause confusion or wonderment: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 87 [106] citing the judgment of a majority of the Full Court in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 170; (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 201 (per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ).

The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is an objective question of fact that is to be determined on the basis of the conduct of the respondent as a whole viewed in the context of all relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. Viewing isolated parts of the conduct of a party “invites error”: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty (2004) 218 CLR 592 at 625 [109] (per McHugh J); Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 341-342 [102] (per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

The question involves the characterisation of the relevant conduct. Evidence that persons have in fact been misled or deceived by the conduct is not an essential element, however, it can in some cases be relevant and material: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198 (per Gibbs CJ).

The tendency of the conduct or representation to mislead or deceive is to be considered or tested against the ordinary or reasonable members of the class to whom the representation was made or the conduct directed. The question is whether a substantial, or at least a reasonably significant, number of that class is likely to be misled or deceived: see Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380 at [336]-[342]. The focus on ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class of consumers means, in effect, that possible extreme, unreasonable or illogical reactions can be put to one side.

It is not necessary to prove that the respondent intended to mislead or deceive, however evidence of such an intention may constitute evidence that the conduct was likely to succeed in misleading or deceiving, and may make a finding of contravention more likely: Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 at 666 (per Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ) .

Where the conduct or representation is in the form of an advertisement, the “dominant message” or “general thrust” of the advertisement is important. It is nevertheless important to have regard to the whole advertisement because context is or may be important. It may also be relevant to have regard to the external context in which a consumer is likely to view an advertisement: TPG Internet at 653-655 [45]-[49] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

In considering whether a representation involving association is conveyed by an advertisement, it must be kept in mind that even vague suggestions are capable of evoking or conveying an association. The association need not be indicated in a manner which is very obvious, but can consist of a subtle or pervasive suggestion: Pacific Dunlop Limited v Hogan (1989) 23 FCR 553 at 586 (per Burchett J); Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation v The South Australian Brewery Co Limited (1996) 66 FCR 451; Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1047 at [17]-[18].

Where the conduct or representation is in the form of words, it would be wrong to fix on some words and ignore others which may provide relevant context and give meaning to the impugned words. It is necessary to have regard to the whole document: Butcher at 638-639 [152] (per McHugh J).

In assessing or characterising the relevant conduct or representation, it is necessary to have regard to any relevant disclaimer. The substance, effect and prominence of the disclaimer must be considered in the context of the conduct or representation as a whole: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation [2007] FCA 1904; (2007) 244 ALR 470 at 494 [116] citing the judgment of the Full Court in Keen Mar Corp Pty Ltd v Labrador Park Shopping Centre Pty Ltd [1989] FCA 54.

The question must ultimately be whether any disclaimer communicates information in such a way or in such a manner that the effect of any otherwise misleading conduct or representation is reversed or erased: Butcher at 638-639 [152] (per McHugh J). A disclaimer in a document or on a website may be more effective than one on, for example, a television advertisement as the latter is likely to be more transient, ephemeral or less noticeable: TPG Internet at 654 [47] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

There may be some circumstances where an express disclaimer inconsistent with the message otherwise conveyed will not prevent the conduct or representation from being misleading or deceptive, or might even reinforce that message: Telstra at [114]. Each case must be considered having regard to its own facts and circumstances.

Was Telstra’s “Go to Rio” campaign misleading or deceptive?

133 The Rio TVCs and website videos should be approached on the basis that the class of likely viewers is very broad and wide-ranging. It would include highly educated, articulate and shrewd members of the public, as well as less experienced and perhaps even unsophisticated or gullible persons. It would include people who were interested in the Rio Olympic Games and its sponsors, but also persons who would be utterly disinterested in such matters. It would include Telstra customers and the tech-savvy, but also people who may not even use a mobile phone, let alone use apps to watch sporting events. Some of the other marketing and promotional materials were most likely directed at a narrower audience. For example most of the digital materials, including the KIT email and the authentication landing page were directed at existing Telstra network customers.

134 It is important to approach the Rio TVCs on the basis that the people within the relevant class of consumer who were likely to view them would generally be unlikely to minutely and critically scrutinise every aspect of the advertisements. The advertisements are likely to be viewed casually and subject to distraction, not intensely and in isolation. The viewer would most likely only take in the main message or theme of the advertisements. Some of the sounds and images used in the advertisements are also somewhat fleeting or transitory. Others are more likely to linger. The musical soundtrack is perhaps most likely to fall into the latter category. The appearance of the “7” logo on the screens of the mobile devices depicted in the advertisement are perhaps likely to fall into the former category.

135 The critical question, in general terms, is whether Telstra’s advertisements, marketing and promotions, conveyed, or were likely to convey, to reasonable persons in the class to whom they were directed or likely to be received, that Telstra had some form of sponsorship, licencing or affiliation arrangement with a relevant Olympic body. If that message or representation was conveyed, it was misleading and deceptive and Telstra’s conduct in causing the advertisement to be published or disseminated was misleading and deceptive.