FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Britax Childcare Pty Ltd, in the matter of Infa Products Pty Ltd v Infa Products Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) [2016] FCA 848

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties supply a draft form of orders implementing the conclusions contained in this judgment within 14 (fourteen) days from today’s date.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[7] | |

[15] | |

[27] | |

D. THE ADMINISTRATORS’ ESTIMATED RETURN TO CREDITORS AND THE CASTING VOTE | [69] |

[80] | |

[85] | |

[101] | |

[101] | |

Britax’s Second and Third Arguments – Prospects of a Better Recovery in a Liquidation and Public Interest | [125] |

[128] | |

The Second, Third and Fourth Transactions: the Quota Transactions | [171] |

[190] | |

[234] | |

[247] |

BURLEY J:

1 The plaintiff, Britax Childcare Pty Ltd (Britax) and the first defendant, Infa Products Pty Ltd (Infa) were competitors in the market for producing baby products including child safety restraints and booster seats in Australia. From 2009 until 2015 Britax pursued patent infringement proceedings against Infa, alleging infringement of multiple patents. After complex and hard fought litigation, Infa lost the case and, as a direct consequence, on 23 December 2015 decided to appoint administrators (the second and third defendants) (Administrators) whose task was to determine whether Infa should be wound up in liquidation or enter into a Deed of Company Arrangement (Deed). After investigating Infa’s affairs, the Administrators recommended to the creditors that they enter the Deed, whereby creditors are paid a proportionate share of about $800,000.

2 There was disagreement at the creditors’ meeting as to whether or not to enter the Deed and ultimately one of the Administrators (Mr Krejci) exercised his casting vote as Chairman of the meeting to vote in favour of execution of the Deed.

3 Britax argues in this case that the Deed should not have been entered and that Mr Krejci wrongly exercised his casting vote. It contends that the Administrators wrongly concluded that the creditors were better off taking a dividend that was available under the Deed than they would have been if a liquidator undertook investigations into Infa and prosecuted actions for breach of duty against its director, Richard Horsfall, and related entities. In particular, Britax points to five transactions dated from 2011 to 2015 in which Infa sold its assets to related companies. It contends that in doing so Infa engaged in a systematic stripping of its assets for the purpose of defeating Britax’s interests as a creditor and enabling Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (Infa-Secure) to continue, phoenix like, to carry on the business of selling child safety restraints and the like in Australia. It is to be noted that by 2010 Infa had ceased to sell equipment that was the subject of the patent infringement proceedings.

4 Britax commenced these proceedings on 24 March 2016 seeking orders under sections 445D and 600B of the Corporations Act, 2001 (Cth) (the Act) that the Deed be set aside and liquidators be appointed to Infa. On 29 March 2016 the Court ordered that the defendants be restrained from executing a Creditors’ Trust Deed (under the Deed, once the Creditors’ Trust Deed is executed by the Administrators the Deed will come to an end, and Infa will no longer be in administration) upon the provision by Britax of the usual undertaking as to damages and upon its undertaking to pay into Court the sum of $45,000, being the amount that Britax calculates that the remaining creditors would receive under the Deed. In this proceeding, Britax has offered that if the Deed is set aside, the sum of $45,000 will be made available to the other creditors.

5 Broadly speaking, the task of the Court in the present case is to determine whether there is a realistic prospect that there may be a better return to creditors on a winding up than under the Deed. Britax contended that there would be, if Richard Horsfall were pursued for breach of his duties owed to Infa as a result of permitting it to enter into the five transactions, and if the parties to those transactions (and their directors) were also pursued for accessorial liability. At trial Infa relied on the evidence of seven witnesses who explained their role in the transactions. The Administrators called two witnesses, who addressed the investigations that they conducted.

6 Having regard to the material presented, I am not satisfied that Britax has established its case to the requisite standard. Most relevantly, I am not satisfied that there is a realistic prospect that a case against Richard Horsfall for breach of directors’ duties in respect of the five transactions would succeed. Nor do I consider that Mr Krejci was incorrect to exercise his casting vote in favour of the Deed.

7 On 23 December 2015 the Administrators were appointed. On 29 December 2015 they issued a First Report to Creditors (First Report) and on 7 January 2016 the first meeting of creditors was held in accordance with section 436E of the Act. Between 5 January and 21 January 2016, the Administrators received Infa’s Report As To Affairs and also were supplied with the books and records of Infa. On 1 February 2016, the Administrators issued their Second Report to Creditors pursuant to section 439A of the Act (Section 439A Report) which, inter alia, encouraged the creditors at the second meeting to consider adjourning that meeting for a short period to enable them to conduct further investigations into certain transactions, including the five transactions now identified by Britax.

8 The Section 439A Report identified the reasons for failure of Infa as follows:

The Director advised that the Company failed because it lacked the financial resources to fund the ongoing litigation against Britax, which if remained uncontested, would inevitably lead to the insolvency of the Company.

Whilst we agree with the above we note the following:

• The revenue from the lease arrangements and contractor services were utilised to partially fund the ongoing Proceedings from 2011. By late 2015 all remaining assets had been disposed, leaving it no further means of generating income.

• The Company could not secure further loans from related parties to continue to fund the litigation.

9 On 8 February 2016 the second meeting of creditors was held and the creditors resolved to adjourn the meeting for 20 business days to enable further investigations to be conducted.

10 On 26 February 2016 the Administrators issued a Supplementary Report to Creditors (Supplementary Report) which, inter alia, addressed a proposal made by Richard Horsfall and Mr Joyce for a Deed of Company Arrangement (Deed Proposal). The Supplementary Report considered the available information and ultimately recommended that the creditors resolve to enter into the Deed of Company Arrangement and a Creditors’ Trust Deed to which the Deed referred. The Supplementary Report noted the Administrators’ preliminary opinion that Infa had become insolvent on 30 June 2015. That date was accepted as correct by Mr Cheshire SC, senior counsel for Britax, for the purposes of the present hearing. Mr Sexton SC, senior counsel for Infa, contended at the hearing that the date of insolvency was later, although it is not presently necessary to address that contest.

11 On 7 March 2016 the second meeting of creditors was reconvened. Mr Krejci chaired the meeting and admitted all creditors present for the amounts of their debts as recorded in the attendance register of the meeting for the purpose of voting at the meeting and not for dividend purposes. Mr Krejci proposed a resolution that Infa execute the Deed of Company Arrangement. Britax voted against that resolution and all of the other creditors voted in favour of it.

12 The representatives of Britax requested that a poll be taken at the meeting pursuant to regulation 5.6.21 of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (the Regulations).

13 The outcome of the voting was such that Mr Krejci had the option pursuant to regulation 5.6.21(4)(a) of the Regulations to exercise a casting vote in favour of the resolution. He had anticipated this outcome and gave a brief explanation for the reasons, summarised in the Supplementary Report, why he intended to cast his vote in favour of the resolution that Infa execute the Deed. He then proceeded to do so.

14 On 24 March 2016 Infa executed the Deed.

The Administrators’ Investigations

15 Mr Krejci was primarily responsible for carrying out the Administrators’ investigations. He was assisted by Mr Keenan, a director in the employ of BRI Ferrier, as well as a number of other employees. About 30 boxes of material were sent to the Administrators by Infa including a hard drive of electronic records. The investigation began on 23 December 2015 and was completed immediately prior to the issue of the Supplementary Report.

16 The investigations commenced with obtaining and reviewing the books and records of Infa, which included the following:

(a) financial statements and primary financial records;

(b) bank statements;

(c) files relating to the Federal Court of Australia patent proceedings with Britax;

(d) insurance policies;

(e) sale transaction documents;

(f) valuation reports;

(g) a creditor listing;

(h) documents relating to intellectual property (IP);

(i) electronic records received by email; and

(j) a hard drive containing electronic records held in Infa’s server.

17 Mr Krejci formed the view that these books and records were sufficient to satisfy the requirements of section 286 of the Act. He also formed the view that Infa had only ever operated as the Corporate Trustee for the Horsfall Family Trust.

18 Mr Krejci’s review of the books and records of Infa were focussed on identifying the financial history of, and business conducted by Infa, its assets and liabilities, its revenue and income, its creditors and debtors, its secured creditors and the reasons for its failure. In addition, Mr Krecji focussed on identifying:

(a) particular transactions which required further investigation;

(b) the date when Infa became insolvent;

(c) any voidable transactions;

(d) any trading whilst insolvent; and

(e) any claims for breach of directors’ duties.

19 Prior to 1 February 2016, and based on the review of the books and records that Mr Krecji and his staff had conducted, Mr Krejci formed the view that several transactions conducted by Infa required further investigation, including the five transactions identified by Britax in the current proceedings. By 1 February 2016, Mr Krejci formed the view that the Administrators’ investigations into these transactions were incomplete and required the following further matters to be done:

(a) obtain financial information relevant to Infa-Secure and Quota Marketing Pty Ltd (Quota);

(b) obtain financial information relevant to Infa Investments Pty Ltd (Infa Investments), which is the majority shareholder of Infa-Secure;

(c) obtain financial information relevant to Richard Horsfall;

(d) interview Mr Joyce, who was an adviser to Infa and its Director, Richard Horsfall, and related companies including Infa-Secure, Quota and Infa Investments;

(e) interview Anthony Horsfall and Matthew Horsfall, who are the sons of Richard Horsfall and who are directors of Infa-Secure, Quota and Infa Investments;

(f) interview Mr Harkin, of Colin Biggers & Paisley Lawyers (Colin Biggers & Paisley), who was the solicitor for Infa and its related companies including Infa-Secure, HBG IP Pty Ltd, Quota and Infa Investments;

(g) interview relevant employees of Chrysiliou Lawyers, who acted for Infa in the Britax patent proceedings;

(h) interview relevant employees of Norman Waterhouse, who were the solicitors for Britax in the patent proceedings;

(i) make further inquiries as to whether Infa carried a directors’ and officers’ insurance policy; and

(j) obtain a preliminary opinion from Hall & Wilcox lawyers (Hall & Wilcox) as to the potential recoverability arising from the transactions, should Infa be placed into liquidation.

20 On 1 February 2016, the Administrators issued the Section 439A Report which, amongst other things, recommended that the Second Meeting of Creditors be adjourned for a short period to enable the Administrators to conduct further investigations. As noted above, that meeting was adjourned for 20 business days to enable the Administrators to conduct further investigations pursuant to subsection 439A(5) of the Act.

21 Following the adjournment of the meeting, the Administrators conducted further investigations with the assistance of Mr Keenan and other staff of BRI Ferrier. Those investigations accorded with the matters identified at [19] above.

22 On 12 February 2016, Mr Krecji requested Mr Harkin to arrange for the provision of financial records necessary for the Administrators to undertake their investigations into the financial position of Richard Horsfall and relevant parties involved in the identified transactions being Infa-Secure, Quota and Infa Investments. Mr Krecji records in his affidavit that the financial records were provided only on the basis that the Administrators keep the information confidential. Accordingly, that material is referred to in these proceedings but has not been made available to the Court to consider.

23 Pursuant to the terms of the Confidentiality Agreement, Mr Krecji was provided with the following:

(a) an undated letter from Richard Horsfall setting out his personal finances;

(b) an unsigned, unaudited Special Purpose Financial Report of Infa Investments for the year ended 30 June 2015;

(c) a balance sheet of Infa Investments as at 31 January 2016 as extracted from the unsigned, unaudited Special Purpose Financial Report for the period ended 31 January 2015;

(d) an unsigned, unaudited Special Purpose Financial Report of Infa-Secure for the year ended 30 June 2015;

(e) an unsigned, unaudited Special Purpose Financial Report of Quota for the period ended 31 January 2016;

(f) the first three pages of the Master Asset Finance Agreement between the National Australia Bank Limited and Infa-Secure, which includes a guarantee from Richard Horsfall, unsigned and undated;

(g) the management accounts of Infa-Secure for the period ended 31 January 2016, and an email from Mr Harkin on 19 February 2016 providing certain comments regarding the financial position of Infa-Secure; and

(h) a further set of management accounts for Infa-Secure for the period ended 31 January 2016, and an email from Mr Joyce dated 23 February 2016 providing certain comments regarding the financial position of Infa-Secure.

24 Mr Krejci arranged for meetings to take place between his staff and various individuals who had roles within Infa or the companies with whom Infa had conducted the transactions of interest. He records in his affidavit that the interviews were conducted on the basis that they be maintained as confidential and, accordingly, his affidavit did not disclose directly what information was provided. Interviews were conducted with each of Mr Joyce, Anthony and Matthew Horsfall and Mr Harkin.

25 Based on the conduct of these interviews, and, no doubt, the further information provided in the documentation referred to above, Mr Krejci records that he formed the view that Infa’s ability to recover monies from Richard Horsfall would be limited given the financial position of the companies in which he held shares, a lack of evidence to support any claim, the preliminary legal advice that he had received to date, and his experience in litigating recovery procedures generally.

26 In about mid February 2016, the Administrators retained Hall & Wilcox to provide a preliminary opinion as to the potential recoverability of assets, arising from the transactions under scrutiny, should Infa be placed into liquidation. Mr Krecji records receiving a letter of opinion from Hall & Wilcox which was apparently influential in his final opinions. That letter was not produced in evidence by Mr Krecji. Britax attaches some significance to that fact.

C. RELEVANT CORPORATE HISTORY OF INFA

27 Infa was incorporated on 28 March 2000. Upon incorporation, the directors of Infa were Roslyn Horsfall, her husband Richard Horsfall, and their sons James and Michael Horsfall. On 10 May 2005 Michael Horsfall ceased to be a director and on 7 December 2010 James Horsfall and Roslyn Horsfall also ceased to be directors, thus leaving Richard Horsfall as the sole director and secretary.

28 Infa carried on business as a developer and wholesaler of baby products including child restraints and booster seats. It did so in its capacity as Trustee of the Horsfall Family Trust. Until it was restructured in 2011, the business was operated through Infa, with distributions being made to the beneficiaries which included a variety of people including, relevantly, members of the Horsfall Family and Quota.

29 The role of Quota was explained in the evidence of Mr Henderson, who was Infa’s accountant and who, between 2007 and 2011, provided general accounting advice to Infa and the Horsfall Family including advice in relation to the business structure of Infa. Each year the Horsfall Family Trust distributed its income to its beneficiaries who paid tax on their distributions at their personal tax rate. Quota paid income tax at the corporate rate. Distributions made to Quota were mostly left unpaid and were used for the purpose of the Trust to ensure that it had enough cash to operate the business in the next financial year.

30 In mid 2007 Britax first threatened to bring patent infringement proceedings against Infa. It appears from correspondence tendered in these proceedings that at that time Infa received confident advice that it was not likely to infringe any valid claim of the patents then asserted.

31 In December 2007, Mr Henderson gave advice to Richard Horsfall by letter that recommended the restructuring of the business from one single discretionary trust into a number of discretionary trusts which “would allow each of the boys to build up capital in the business within their own discretionary trust”. Mr Henderson also advised that another advantage of this restructure was that “the trusts could invest capital in the business… [which] would free up Richard’s capital and allow him to withdraw it from the business to lend to the boys privately to repay their existing loans”. Mr Henderson explained that this would allow the business to enjoy a tax deduction on its interest payments. No further steps were taken in 2007 or 2008 regarding any restructuring.

32 In March 2009 Britax commenced patent infringement proceedings against Infa. From the outset of the proceedings the advice given to Infa was that its prospects of success were robust.

33 Ms Chrysiliou, a solicitor and patent attorney, specialising in patents, acted for Infa from late 2008. She gave evidence that she provided Infa advice, in part on the basis of counsel’s advice, that it had good prospects of defending the patent infringement proceedings brought by Britax and that any financial exposure was relatively contained. In particular, Ms Chrysiliou’s advice to Richard Horsfall throughout the litigation was that Infa’s costs exposure was limited, as any damages against Infa were likely to be minimal. In cross-examination Ms Chrysiliou accepted that she and counsel had advised Richard Horsfall that Infa was likely to achieve a result that was either a good outcome where any infringed claim was found to be invalid or a “mixed outcome”, that involved some claims of the patents in suit being infringed by some or all of Infa products and some, but not all, of these patents being invalid. Ms Chrysiliou’s written advice of 30 April 2015 was that, regardless of the outcome of the liability part of the trial “[i]t is likely the defence of innocent infringement would greatly narrow the scope of damages or account of profits, depending on the Infa versions which infringe”. Her evidence was that Britax would be “unlikely” to obtain a full award of costs, as a formal offer of settlement had been made that may operate to increase the costs order in favour of Infa. Ms Chrysiliou confirmed that advice to this effect had been given by her to Richard Horsfall on multiple occasions.

34 It is relevant in these proceedings to consider Richard Horsfall’s state of mind as to the prospects of success in the litigation. In this respect I agree with Infa’s characterisation of his evidence which was that he was advised from about 2010 through to 2015 that the likely outcome of the patent infringement proceedings was a “mixed outcome” by which he understood that Infa might have to pay a little money to Britax. Furthermore he was advised of the possibility that each party would pay their own costs and that costs would never be 100% recoverable.

35 On 2 February 2011 the first substantive hearing of the patent case commenced (Construction Hearing). It was limited to the question of construction of the patents and infringement. The trial was completed on 17 February 2011 after 11 sitting days. Judgment was reserved.

The First Transaction – 2011 Sale of Infa’s Goodwill and Stock

36 On 7 February 2011 Infa entered into an agreement whereby it sold its stock and also its goodwill to Infa-Secure. This is identified in the plaintiff’s Amended Points of Claim (Points of Claim) as the First Transaction out of five that it questions in this proceeding.

37 The Points of Claim relevantly contend that the First Transaction was:

(1) entered into five days after the commencement of the Construction Hearing of the patent case, without being disclosed to Britax or to the Court;

(2) made by Infa for the purpose of giving effect to its scheme to divest itself of assets and transfer them to related entities or close associates;

(3) a breach of Richard Horsfall’s fiduciary duties owed to Infa;

(4) an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of section 588FB of the Act;

(5) an insolvent transaction within the meaning of section 588FC of the Act; and

(6) entered into for the purpose of defeating Britax’s ability to enforce any judgment against Infa which would be awarded in its favour and therefore was a transaction to defeat creditors within the meaning of section 588FE(5) of the Act or section 37A of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) (Conveyancing Act).

38 In its First Report the Administrators noted that the First Transaction was a sale to a related party because Richard Horsfall was at the time the sole director of Infa and also the sole director of Infa-Secure. The Section 439A Report summarises the transaction as follows:

The company profitably traded its business during the Proceedings through March 2011 when the company sold the business to Infa-Secure. We are advised that the sale was part of a family succession plan, whereby the control of the business was transferred to [Richard Horsfall’s] son, Matthew Horsfall, the director of Infa-Secure. The Company transferred its goodwill and stock to Infa-Secure for $271K and $1.7M, respectively, the proceeds of which were paid over the 2 following years with the final payment being received in August 2012. The sale price was supported by a valuation report, which is discussed later.

Having transferred the core business to Infa-Secure, the company retained ownership of the trading premises, the plant and equipment and the rights to the IP, where these assets were leased to Infa-Secure on commercial terms.

39 The Section 439A Report notes that the sale price had been based on an external valuation prepared by UBT Accountants and “[w]hilst the valuation report itself is not a comprehensive document in our experience, we do not have any evidence available to us that suggests that the value attributed and paid was inappropriate”. Nevertheless, the Administrators intended to review the sale to test whether fair value had been given because the financial records indicated that the company was trading profitably at the time of sale. To this end, the Administrators state their intention to make inquiries with the valuer to test the methodology used and understand if any further supporting evidence exists. Alternatively, if this were not possible, and subject to the obtaining of funding, the Administrators observed that it may be relevant to seek a comparative valuation. They note, however, that “the lapse in time since the sale (being approximately 5 years ago) may prevent any meaningful critique of the transaction”.

40 The Supplementary Report returned to the First Transaction. As the Administrators’ views in this respect were the subject of criticism by Britax at the hearing, they are reproduced below (emphasis added):

Our review focused on the value the Company obtained for its assets. If the transaction was deemed to be undervalued, a claim could be made for the difference between the sale price and true market value at the time.

Our enquiries indicate that the transaction could not be challenged as an uncommercial transaction as it occurred when the company was likely solvent. Furthermore, it could not be pursued as an unreasonable director related a transaction since it occurred more than 4 years ago, and is therefore time barred. Accordingly, no voidable recoveries are available in a winding up.

However, our enquiries indicate that the Director may have breached his director’s duties under Section 181 by entering into the sale of goodwill and stock to Infa-Secure in 2011 if it could be established that the assets were sold for an improper purpose.

In particular, a number of factors which considered as a whole, may infer that the Director entered into the transaction as a precautionary measure to strip the Company of an income stream that would otherwise be available to, partially or wholly, discharge any liability that may be made in favour of Britax as a result of the Proceedings. Upon interrogating the valuation upon which the sale was based, we are advised that the sale price for the goodwill component may have been undervalued by at least $1M, a claim for which may be capable of being brought against the Director.

To determine whether the sale was at undervalue, a secondary valuation of the business will be required. We have received advice from an experienced valuer that indicates whilst it is possible to obtain a valuation it would have to be based on Company records and industry information that may be difficult to obtain or may no longer be available (as the transaction occurred over 5 years ago). As such significant funding would be required to undertake the exercise, which may ultimately result in a valuation that could be speculative and therefore open to challenge.

Accordingly, it is our view that the Breach of Duty claim would be difficult to prove and, for the reasons set out later herein, would not be commercial to pursue in a winding up.

41 Mr Krejci, gave evidence in the proceedings. He explained that in preparing the Supplementary Report, the opinion of an experienced valuer had been sought. He also said that there was: (a) no evidence to suggest that the valuation was less than market value, (b) his team’s investigations showed no evidence that Richard Horsfall had entered the transaction as part of a “scheme”, (c) there was no direct evidence to support a claim that Richard Horsfall had breached its duties to Infa, (d) a liquidator would be without funds and no offers had been received by creditors to fund any liquidation.

42 The Supplementary Report also adverted to an absence of funds on the part of Richard Horsfall to warrant proceedings against him for the recovery of any substantial amount.

43 Britax submitted that the passage in the quotation above at [40] (“we are advised that the sale price for the goodwill component may have been undervalued by at least $1M”) was an expression of opinion by the Administrator. Infa submitted that this was incorrect and that the Administrators had hypothesised that the transaction may have been at an undervalue, but absent a second valuation (which was unfunded) this could not be determined. Infa also submitted that such a valuation may in any event be inconclusive given the effluxion of time. I agree in this respect with Infa’s submission. It is apparent to me from the full passage quoted above that the Administrators considered that, whilst there was a possibility that the sale was at an undervalue, any conclusion to that effect would require a secondary valuation which would require funding and may, in any event, be speculative.

44 Further, Mr Krejci explained in his affidavit that the $1,000,000 figure was given for illustrative purposes for the sake of testing the likelihood of a commercial recovery value of any claim. His investigations did not reveal any evidence to suggest that the valuation prepared by UBT Accountants was at an undervalue. It was (and remains) his view that in the absence of a second valuation to the contrary, the valuation of $271,000 for goodwill represented fair value.

The Second Transaction – Grant of Security to Quota

45 On 21 December 2011 Quota was granted a second ranking fixed and floating charge over the assets of Infa and was also registered as a second mortgagee of property owned by Infa at 110-114 Old Bathurst Road, Emu Plains (Property) ranking behind the National Australia Bank. The charge was registered on 17 January 2012. The grant of the security to Quota is identified in the Points of Claim as the Second Transaction.

46 The plaintiff alleged in the Points of Claim that the Second Transaction was:

(a) made by Infa for the purpose of elevating the status of Quota from an unsecured creditor to a secured creditor;

(b) not disclosed to Britax or the Court;

(c) made by Infa for the purpose of giving effect to its scheme to divest itself of its assets and transfer them to related entities or close associates;

(d) in breach of Richard Horsfall’s fiduciary duties owed to Infa;

(e) an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of section 588FB of the Act;

(f) an insolvent transaction within the meaning of section 588FC of the Act; and

(g) entered into for the purpose of defeating Britax’s ability to enforce any judgment against Infa which would be awarded in its favour and therefore was a transaction to defeat creditors within the meaning of section 588FE(5) of the Act or section 37A of the Conveyancing Act.

47 Since February 2005 the directors of Quota have been Richard Horsfall’s sons, Steven and Anthony Horsfall.

48 Both the Section 439A Report and the Supplementary Report address the Second Transaction. The latter observed that it was unclear how Infa had benefitted from the granting of security, other than potential, albeit undocumented, forbearance in respect of the debts owed to Quota by Infa. Quota received payments totalling $1,800,000 between the date the security was granted and the commencement of the administration.

49 The Supplementary Report also recorded that the Administrators had been advised that the security registration could not be challenged as an uncommercial transaction on the basis that it occurred when Infa was solvent. Further, it could not be challenged as an unreasonable director-related transaction since it was granted four years and two days prior to the appointment of the Administrators and therefore was time barred.

50 The Supplementary Report then indicated that Richard Horsfall may have breached his duties to Infa by granting Quota the security, given that Quota was a related party (Richard Horsfall and his wife, Roslyn, had a combined 60% direct interest in Quota). Richard Horsfall might therefore have promoted his own interests and Quota’s ahead of those of ordinary unsecured creditors, including Britax. The Supplementary Report notes that in this context the security was granted two years after the commencement of the proceedings and the benefit to the company is “questionable” where no Deed of Forbearance was entered into.

51 Finally, the Supplementary Report observed that if the security was not granted in good faith, the director could be pursued for breach of directors’ duties where a claim totalling $892,000 could be made against him.

The Third Transaction and events leading to 21 December 2015

52 The Points of Claim identify that between December 2011 and December 2015, Quota received payments of approximately $908,000 from Infa. Those payments are described as the Third Transaction.

53 The Points of Claim allege that the Third Transaction was:

(a) not disclosed to Britax or to the Court;

(b) made by Infa for the purpose of giving effect to its scheme to divest itself of its assets and transfer them to related entities or close associates;

(c) in breach of Richard Horsfall’s fiduciary duties owed to Infa;

(d) an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of section 588FB of the Act;

(e) an insolvent transaction within the meaning of section 588FC of the Act; and

(f) entered into for the purpose of defeating Britax’s ability to enforce any judgment against Infa which would be awarded in its favour, or the judgment against Infa which had been awarded in its favour and therefore was a transaction to defeat creditors within the meaning of section 588FE(5) of the Act or section 37A of the Conveyancing Act.

54 The evidence given by Ms Seeder (Infa’s accountant at the time, who had provided accounting services to Infa since 2000), indicates that on occasions in both 2013 and 2014, Infa made repayments of the secured loan (that is, the loan arising from the Second Transaction) of $350,000 to Quota, totalling $700,000. Ms Seeder’s evidence also indicated that in 2013 Infa paid an amount of at least $148,288 to Quota for the tax due on the interest earned from its loan to Infa Products.

55 In other words, Ms Seeder’s evidence was that the criticised payments that comprise the Third Transaction were attributable to payments made by Infa pursuant to the secured loan entered as the Second Transaction.

56 In the period following the Third Transaction, the following relevant events took place:

(a) 9 May 2012 – Middleton J delivers his decision in relation to the question of the construction of the patents – (2012) 290 ALR 47 (Construction Judgment);

(b) 13 August 2013 to 21 February 2014 – the patent infringement hearing resumes (spread over 8 hearing days) addressing issues concerning the validity of the claims of the patents in suit and an issue relating to infringement (Validity Hearing);

(c) 23 March 2015 – the parties are notified that Middleton J intends to deliver judgment in the Validity Hearing;

(d) 11 June 2015 – HBG IP Holding Pty Ltd is incorporated with its directors being Richard Horsfall and his sons, Steven and Anthony;

(e) 30 June 2015 – Middleton J gives judgment in the Validity Hearing – [2015] FCA 651 (Validity Judgment);

(f) 10 August 2015 – Infa obtains Raine & Horne valuation of the Property which estimates its value to be in the range from $4,270,000 to $4,611,600;

(g) 19 August 2015 – Middleton J makes orders that Infa has infringed the Britax patents, certifies the validity of those patents, gives directions for discovery by Infa relevant to the assessment of damages or on account of profits and orders that Infa pay Britax’s costs. The costs order was stayed pending appeal;

(h) 9 September 2015 – Infa files a Notice of Appeal from the Validity Judgment;

(i) 16 September 2015 – a valuation of Infa’s IP is conducted by PKF (NS) Pty Limited giving an estimated value of $524,401 (PKF valuation);

(j) October 2015 – Infa lists the Property for sale;

(k) 17 November 2015 – the Property is sold at auction to Crofur Pty Ltd for $4,550,000. The proceeds of the sale are paid as follows:

(i) $1,722.09 to Sydney Water;

(ii) $550,000 to Quota;

(iii) $9,500 for solicitors’ fees; and

(iv) $3,493,981.11 to the first mortgagee, the National Australia Bank

(l) 10 December 2015 – Jessup J orders that Infa give security for costs in relation to its appeal of $330,000 with $230,000 payable by 24 December 2015.

The Fourth Transaction – Sale of the Property and Distribution to Quota

57 On 17 December 2015, Infa sold the Property to a third party for $4,550,000 and $550,000 was paid to Quota from the proceeds. That payment is identified in the Points of Claim as the Fourth Transaction.

58 Britax alleges in its Points of Claim that the Fourth Transaction was:

(a) not disclosed to Britax or to the Court;

(b) made by Infa for the purpose of giving effect to its scheme to divest itself of its assets and transfer them to related entities or close associates;

(c) in breach of Richard Horsfall’s fiduciary duties owed to Infa;

(d) an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of section 588FB of the Act;

(e) an insolvent transaction within the meaning of section 588FC of the Act; and

(f) entered into for the purpose of defeating Britax’s ability to enforce any judgment against Infa which would be awarded in its favour, or the judgment against Infa which had been awarded in its favour and therefore was a transaction to defeat creditors within the meaning of section 588FE(5) of the Act or section 37A of the Conveyancing Act.

59 The sale of the Property was conducted by public auction, and the price received fell within the upper part of the range estimated in the Raine & Horne valuation. In the Supplementary Report the Administrators expressed the preliminary view that the transaction was valid and would not be subject to any voidable recovery in the case of a winding up.

60 The complaint that Britax makes about the sale is, in essence, that the payment of proceeds to Quota should be investigated and set aside.

61 The evidence of Kunal Shah, Infa’s bookkeeper since 2012, indicates that on 17 December 2015 Quota received payments of $550,000 from the proceeds of the settlement and $384,000 from Infa, which payments were made based on Nirav Shah’s (Infa-Secure’s commercial financial manager) calculation of Infa’s indebtedness to Quota under the Second Transaction.

62 The evidence also indicates that from these funds, Quota lent $500,000 to Richard Horsfall, which was then transferred to the trust account of Colin Biggers & Paisley to be utilised for a fund to be set up in accordance with the Deed (further details of the fund are set out below at [75]).

The Fifth Transaction – Sale of Intellectual Property to HBG IP Holding Pty Ltd (HBG)

63 On 22 December 2015, the day before the Administrators were appointed, Infa sold its last remaining asset, being its IP, for $524,000 to HBG, a company owned in equal parts by Richard Horsfall’s four sons, Steven, Anthony, Matthew and James. HBG was a corporation formed for the purpose of licensing Infa-Secure to use the IP in relation to products that it sold. This is referred to in the Points of Claim as the Fifth Transaction.

64 Britax alleges in its Points of Claim that the Fifth Transaction was:

(a) made by Infa for the purpose of giving effect to its scheme to divest itself of its assets and transfer them to related entities or close associates;

(b) not disclosed to Britax or to the Court;

(c) an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of section 588FB of the Act;

(d) an insolvent transaction within the meaning of section 588FC of the Act; and

(e) entered into for the purpose of defeating Britax’s ability to enforce any judgment against Infa which would be awarded in its favour, or the judgment against Infa which had been awarded in its favour and therefore was a transaction to defeat creditors within the meaning of section 588FE(5) of the Act or section 37A of the Conveyancing Act.

65 The Points of Claim also alleged that the Administrators had estimated that the Fifth Transaction may have been at an undervalue of up to $1,000,000.

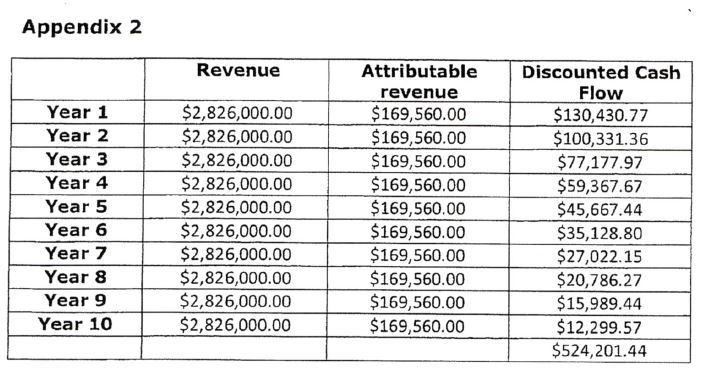

66 The evidence adduced at trial indicated that the Administrators were informed of the proposed Fifth Transaction prior to their appointment and identified it as a transaction warranting scrutiny in each of the First Report, Section 439A Report and Supplementary Report. The latter relevantly reported as follows (emphasis added):

… our enquiries of this transaction focussed on whether the sale price of $524K represented fair value, in circumstances where the IP was not taken to market and the transaction was entered into the day prior to our appointment. We made further enquiries of PKF, who prepared the valuation report on which the sale price is based. The valuers responses were reasonable, and we have not been able to locate any evidence that suggests the IP was sold undervalue.

However, we have received advice that a breach of duties claim could potentially be made against the Director on the basis that he caused detriment to the Company by entering into the transaction in the midst of the ongoing Proceedings and with the knowledge of the imminent appointment of Voluntary Administrators, causing those assets to be out of the control of creditors.

The claim would be based on the loss suffered, should it be proven that the sale price was undervalue, by virtue of engaging an alternate valuer. In this regard, unless a secondary valuation provides a compelling case to have the sale set aside, there will be no reason to pursue the Breach of Duty claim.

Further, it will be difficult to prove the intent on [sic] the Director based on the evidence currently available and hence the prospects of successfully proving this claim are remote.

Regardless, for the purposes of our analysis of potential recoveries in winding up we have assumed that there may be a claim of up to $1M against the Director for a Breach of Duty. However, based on the Director’s personal financial circumstances, a meaningful return is not anticipated.

Should creditors resolve to accept the DOCA [Deed of Company Arrangement] proposal, the IP sale will complete on execution of the DOCA and the proceeds will be paid into the Deed Fund.

67 Evidence was adduced at trial from Mr Immerman, a chartered accountant, who was engaged by Infa-Secure in late 2014 to provide financial modelling services. Mr Immerman was unaware of the Britax litigation when he gave general advice at a “pitch” presentation to Richard Horsfall, Anthony Horsfall, Michael Horsfall and Mr Joyce to the effect that a trading company such as Infa-Secure should not hold valuable assets such as IP and real estate in its own name. He suggested that a new entity be established to hold assets owned by Infa-Secure, subject to the costs of transferring the assets at market value. Subsequently HBG was formed.

68 Richard Horsfall explained:

In or around August 2015 I made the decision to sell the intellectual property held by Infa Products to HBG. I wanted to wind back Infa Products further, it wasn’t of vital importance to Infa Products to hold the intellectual property because it wasn’t trading and I figured that this was one avenue to finance the appeal in the Britax Court Proceedings. My understanding was that this sale would occur at fair value and the sale proceeds would be available as an asset for Infa Products.

D. THE ADMINISTRATORS’ ESTIMATED RETURN TO CREDITORS AND THE CASTING VOTE

69 The Supplementary Report reviewed the prospects of a liquidator being able successfully to conduct investigations against the sole director of Infa (Richard Horsfall) and then pursue claims for breach against him. As set out above at [25], the Supplementary Report was, for a variety of reasons, pessimistic of a liquidator successfully pursuing Richard Horsfall.

70 The Supplementary Report considered the value of pursuing claims against Richard Horsfall in respect of the transactions of interest, given the costs of any investigations and subsequent proceedings. It noted at page 5, in the Executive Summary (emphasis added):

As you will note from the above, all recovery actions would be against the Director, Richard Horsfall, where the gross value of the claims may be in excess of $2.8M (estimates only). Any claims would require fairly involved litigation to be brought by a Liquidator, for which our preliminary legal advice puts the prospects at “fair to reasonable”. It would be necessary to conduct public examinations of the Directors and related persons in order to gather further evidence. The liquidator would need sufficient funding to run the proceedings, and protect his exposure to adverse costs, where no offers have been forthcoming to date. Finally, where we are advised that the Director would defend such actions with the support of his family, and therefore it is our expectation that any claims would need to be successfully prosecuted through judgement [sic], enforcement and the likely bankruptcy of the Director, in order for any value to be extracted.

Putting aside the legal rights, it is essential to consider the commercial value of such claims.

71 It is to be noted that whilst legal advice may have put the prospects at “fair to reasonable” it is apparent from the more detailed review of the transactions reported in the Supplementary Report – some of which is quoted above – that the Administrators considered the prospects of success in recovery against Richard Horsfall to be somewhat lower than that. At the Second Creditors’ Meeting Mr Krejci, as Chairman of the meeting, gave his opinion in explaining his casting vote that “[t]here is considerable doubt about whether the transactions can in fact be impugned”. This view was reinforced and amplified by Mr Krejci in his oral evidence:

--- you say there was no direct evidence to support a claim that Richard Horsfall had breached his duties to Infa in relation to the transaction in 2011?--- Yes.

Do you maintain your opinion that there is no such direct evidence?--- Yes.

You have seen the evidence of professional advisers concerning the advice they gave about the restructure of what might be described as a family business?--- Yes.

And in relation to the transactions involving Quota, you’ve seen the professional advice that was given about 7A loans?--- Yes.

And having regard to all of that evidence as well as the material that Mr Cheshire took you to this morning, assuming unlimited funds to investigate, if you, for example, were the liquidator, what is it precisely that you think might have to be investigated?--- I think a forensic exercise would need to be undertaken of all the – all the documentation to understand whether there is any evidence of parties aiding and abetting or somehow facilitating a director’s breach of duty. So it would be a forensic exercise of going through all the material to see what exists.

And from the 30 boxes plus the hard drive that you’ve already received---?--- Yes.

--- there’s nothing to suggest such a thing, is there?--- No, not in that material.

72 In relation to the commercial value of the claims, the Supplementary Report considered Richard Horsfall’s personal financial position and estimated that in a bankruptcy situation his assets may amount to $550,000. This was based on a confidential disclosure by Richard Horsfall of his asset position to the Administrators. At trial, further information was provided by Richard Horsfall as his assets – Exhibit B. In light of this further information, no suggestion was made by Britax in closing submissions that the Administrators’ estimate in the Supplementary Report was inaccurate. The potential to recover this amount was balanced against the Administrators’ estimate that the liquidators’ costs of examining Richard Horsfall and then prosecuting an action against him would be at least $450,000, resulting in a net recovery of about $100,000.

73 In fact, the evidence adduced at trial as to Richard Horsfall’s assets indicated a high probability that even a successful action against Richard Horsfall would yield a nil return.

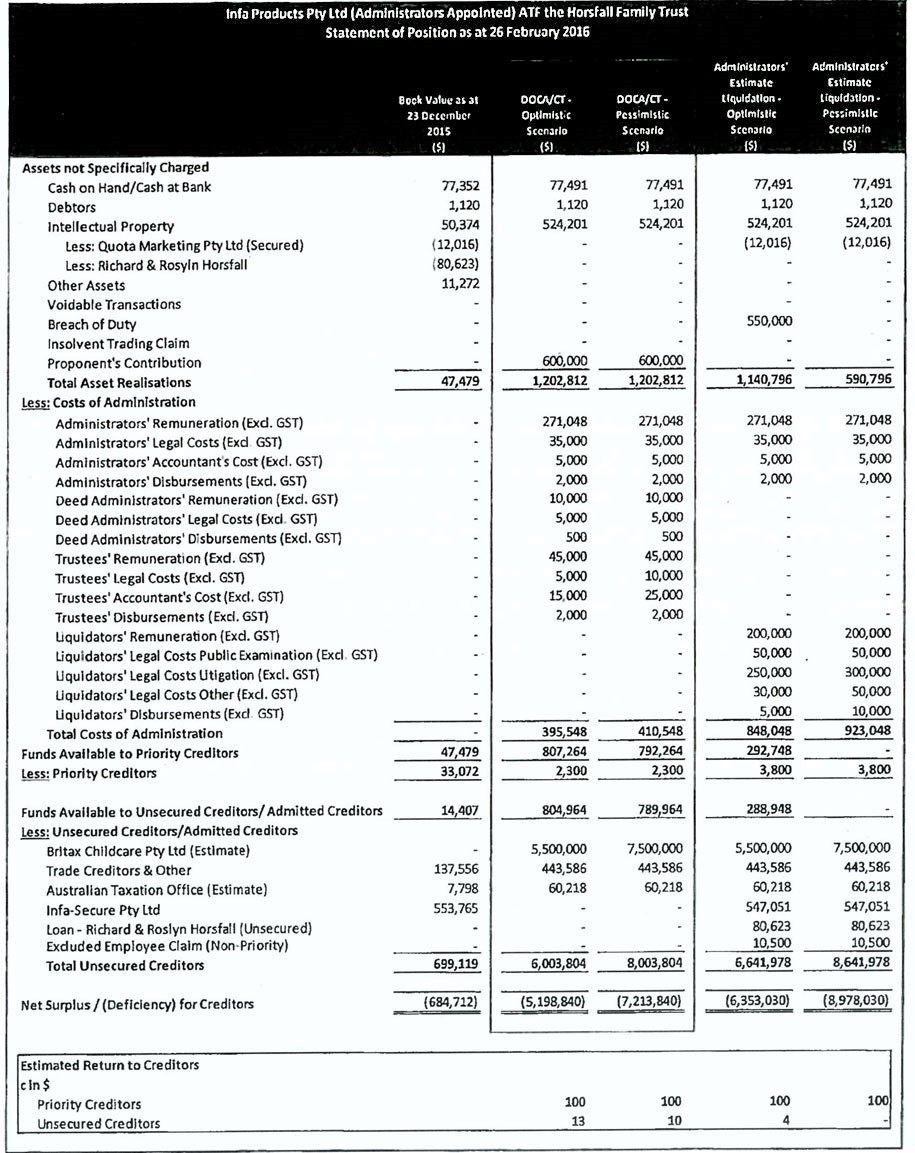

74 The Supplementary Report sets out the following table, providing the Return to Creditors under both a Deed of Company Arrangement scenario and a winding up scenario:

75 The Supplementary Report then provided a summary of aspects of the Deed Proposal, some of which are as follows:

The Deed will incorporate the formation of a Creditors’ Trust which will govern the distribution of assets to creditors.

The Administrators will become the Deed Administrators and the Trustees of the Creditors’ Trust.

Control of Infa will revert to the Director, Richard Horsfall, upon execution of the Deed.

Upon acceptance of the Deed Proposal, Infa will complete the IP Sale Agreement with HBG within 10 days of the resumption meeting and HBG will pay the outstanding balance of $524,000 to Infa. Infa’s only unrelated employee, Mr Wainohu, will be transferred to HBG along with his unpaid employee entitlements, including unpaid superannuation. Accordingly, Mr Wainohu will not have a claim under the Deed or Creditors’ Trust.

The Deed will be executed within 15 days of the resolution passing it (by the time of the commencement of these proceedings, that had taken place).

A fund will be established which will include the Deed Administrator transferring the cash balance from the voluntary administration into the fund, including the proceeds from the completion of the IP Sale Agreement (Deed Fund). The Deed Fund will also include the sum of $600,000 deposited by the Deed Proponants, Richard Horsfall and Mr Joyce. The Administrators estimated that the Deed Fund would hold approximately $1,200,000.

The Creditors’ Trust will be formed shortly after all contributions are received into the Deed Fund which will then become the Creditors’ Trust Fund.

Upon the formation of the Creditors’ Trust, the Deed will be effectuated and all creditors’ claims against Infa will be extinguished and transferred to the Creditors’ Trust. Creditors will then become beneficiaries of the Creditors’ Trust and any distribution of dividends will be paid to creditors as beneficiaries under it.

The Creditors’ Trust Fund will be distributed in the following manner: first, payment of the costs, liabilities, remuneration and disbursements of the Administrators; secondly, payment of priority creditors’ claims to the extent they are not excluded claims of a related party; thirdly, payment of admitted unsecured creditors on a pari passu basis excluding all related parties (and, specifically, Infa-Secure, Richard Horsfall, Roslyn Horsfall and Quota Marketing) which means that claims of approximately $655,000 will not participate in the distribution.

Dividends will be paid in a manner similar to that in a liquidation.

76 On 7 March 2016 the Second Creditors’ Meeting was conducted in accordance with section 439A of the Act and the Supplementary Report was presented to creditors. At the meeting, a representative of Britax indicated that they “had concerns” about the sale by Infa of the Property and the IP, and specifically, were concerned that the Administrators had not obtained a second valuation for the IP. Mr Keenan explained that the Administrators had investigated the Property sale transaction and found it to be reasonable and at arm’s length, and had made investigations of the PKF valuation of the IP. He noted that the Administrators had found that the IP sale was reasonable and there was no basis to have it set aside. Britax’s representative stated at the meeting that his clients had a number of concerns remaining with the Supplementary Report but indicated that they did not wish to particularise those concerns any further at the meeting.

77 A poll was taken at the meeting pursuant to regulation 5.6.21 of the Regulations and voting was as follows:

Poll Results | Number | Value |

In Favour | 12 | $1,114,529.17 |

Against | 1 | $8,593,500.00 |

78 Mr Krejci advised that professional standards required him to exercise his casting vote unless there was good reason not to. He then explained his reasons for exercising a casting vote in favour of the Deed being to the effect that certainty of recovery, the availability of the Deed Fund and the non-participation of related creditors outweighed the potential benefits of a liquidation. In this regard he was doubtful of the commercial value of claims against Richard Horsfall, noting that there was “considerable doubt” whether the transactions can be impugned and that it is not clear whether sufficient evidence could be obtained against Richard Horsfall, and further, it is not clear that the relevant transactions were in a period that would permit recovery.

79 Having regard to the fact that Infa had no business to be preserved and the objectives set out in section 435A of the Act, he considered that there was a need to exercise his casting vote in favour of the Deed.

E. SUMMARY OF BRITAX’S POSITION

80 In closing submissions Britax ultimately argued that the Deed should be set aside for the following reasons.

81 First, it contended that because it is the only creditor with a valid interest in whether the Deed is set aside, it is “entitled to decide whether it wishes to accept its entitlement under the Deed or have the Deed terminated and Infa placed into liquidation”. No creditor other than Britax might suffer prejudice if the Deed is terminated. Accordingly, under section 445D(1)(e), (f) or (g) and section 600B the Court must set the Deed aside.

82 Secondly, the Deed should be set aside pursuant to section 445D(1)(c), (e), (f) and (g) and section 600B because there are prospects of a better recovery for creditors in a liquidation than under the Deed because of available claims against Richard Horsfall for breaches of duties and third party accessories to these breaches. Consideration of this argument involves consideration of each of the five transactions.

83 Thirdly, there is a public interest in investigating the five transactions under a liquidation pursuant to section 445D(1)(e), and (g) and s 600B.

84 Before considering these arguments, it is convenient briefly to summarise some of the relevant legal principles that are relevant.

F. BACKGROUND LEGAL PRINCIPLES

85 The administration of a company’s affairs is provided for in Part 5.3A of the Act. That Part commences with section 435A which provides that its Object is to provide for the business, property and affairs of an insolvent company to be administered in a way that either maximises the chances of the company, or as much as possible of its business, continuing in existence or, if it is not possible for the company or its business to continue in existence, results in a better return for the company’s creditors and members than would result from an immediate winding up of the company.

86 Part 5.3A of the Act was introduced into the Corporations Law in 1992 as a result of the recommendation of the Harmer Committee in 1988 (Australian Law Reform Commission, General Insolvency Inquiry, Report No 45 (Canberra, 1988) (Harmer Report)). The Harmer Report reviewed the existing processes for dealing with company insolvencies on a voluntary basis and noted, at 26 [46], that:

The procedure for a scheme of arrangement is cumbersome, slow and costly and is particularly unsuited to the average private company which is in financial difficulty. The time taken to implement a scheme varies but in general is at least two to three months. The legal and accountancy costs of even a relatively straightforward scheme are substantial.

87 When the Corporate Law Reform Bill 1992 (Cth) was introduced, the Explanatory Memorandum (Explanatory Memorandum, Corporate Law Reform Bill (Cth) 1992) stated (at [449]) that the new Part was intended to provide for speed and ease of commencement of administration, minimisation of expensive and time-consuming court involvement and formal meeting procedures, flexibility of action and ease of transition to other insolvency solutions where an administration does not by itself offer all of the answers.

88 It is with these objectives in mind that section 435A was introduced. The administration process operates in circumstances where those controlling the relevant company have accepted that it is insolvent. It has been accepted that the investigation conducted in the administration process is intended by Parliament to be a “swift and practical” one; In the matter of Mustang Marine Australia Services Pty Ltd (admin apptd) - Perpetual Trustee Company Ltd v Mustang Marine Australia Services Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 1429 (Mustang Marine) at [109]. Consistent with this, the administrator’s investigation is necessarily a preliminary investigation which involves the administrator carrying out his or her investigations in a manner which is modified in light of the tight timeframe and associated constraints provided for by Part 5.3A. An administrator, so constrained, cannot carry out a detailed investigation of at company in the same way as can a liquidator, and accordingly the administrator’s actions must be looked at in the light of that more restricted range of activities which are available to him or her; Mediterranean Olives Financial Pty Ltd v Loaders Traders Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (No 2) [2011] FCA 178; (2011) 82 ACSR 300 (Mediterranean Olives) at [61] – [62].

89 Section 445D(1) of the Act empowers the Court to order that a Deed of Company Arrangement be terminated. That subsection provides:

(1) The Court may make an order terminating a deed of company arrangement if satisfied that:

(a) information about the company’s business, property, affairs or financial circumstances that:

(i) was false or misleading; and

(ii) can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors of the company in deciding whether to vote in favour of the resolution that the company execute the deed;

was given to the administrator of the company or to such creditors; or

(b) such information was contained in a report or statement under subsection 439A(4) that accompanied a notice of the meeting at which the resolution was passed; or

(c) there was an omission from such a report or statement and the omission can reasonably be expected to have been material to such creditors in so deciding; or

(d) there has been a material contravention of the deed by a person bound by the deed; or

(e) effect cannot be given to the deed without injustice or undue delay; or

(f) the deed or a provision of it is, an act or omission done or made under the deed was, or an act or omission proposed to be so done or made would be;

(i) oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, one or more such creditors; or

(ii) contrary to the interests of the creditors of the company as a whole; or

(g) the deed should be terminated for some other reason.

90 The inquiry under section 445D involves two stages, although they are related. The first is whether one of the grounds referred to in subsection (1) is established. The second, which arises only if the first is established, is whether as a matter of discretion, the deed should be terminated; In the matter of Recycling Holdings Pty Limited [2015] NSWSC 1016; (2015) 107 ACSR 406 (Recycling Holdings) at [29].

91 The plaintiff bears the onus of establishing that each of the stages have been satisfied; Mediterranean Olives at [179].

92 In the present case, subsections (c), (e), (f) and (g) of section 445D(1) are said to be relevant and it is contended that these subsections are activated by reason of an analysis which would yield a greater return to creditors upon a liquidation (and prosecution following a liquidator’s investigation) than is currently available under the Deed Fund.

93 The analysis required under section 445D(1) does not require the Court to determine whether the proposed courses of action identified by Britax as potentially available are made out on the balance of probabilities. It is sufficient if the Court is satisfied that there is a “not unrealistic prospect that there may be a return to creditors on a winding up that is better than under the [Deed]”; Mustang Marine at [136]. Put another way, the plaintiff must establish a “serious case for the recovery of assets in a liquidation”; Re Octaviar Ltd (No 8) [2009] QSC 202; (2009) 73 ACSR 139.

94 In Molit (No. 55) Pty Ltd v Lam Soon Australia Pty Ltd (Administrator Appointed) [1997] FCA 395; (1997) 24 ACSR 47 at 51, Branson J adopted the following test set out by Lehane J in Hamilton v National Australia Bank Ltd (1996) 66 FCR 12 at 34) (emphasis added):

In my view the task of the Court in a case such as this is to form a view, on all the material before it, as to whether there is a real prospect that in [sic] a liquidation claim in which (or in the fruits of which) the second secured creditor has an interest could and would be pursued so as to afford to the second secured creditor recovery of more of the debt owed to it than it would obtain under the proposed deed of company arrangement.

95 It has been said that a primary consideration in the exercise of the Court’s discretion under section 445D(1) is the interest of the creditors, indeed, the fact that a majority of creditors favour the Deed is in itself a factor in favour of not terminating it under section 445D; Bidald Consulting v Miles Special Builders; Bidald Consulting v Miles Special Builders [2005] NSWSC 1235; (2005) 226 ALR 510 (Bidald) at [272] (per Campbell J). However, the discretion is to be exercised having regard not only to the interests of creditors as a whole but also to the public interest, an interest that includes considerations of commercial morality and the interests of the public at large; Bidald at [287]. In this regard, Campbell J in Bidald made the following observations (emphasis added):

[290] For a director to avoid public examination about the affairs of the corporation, and the possibility of the type of clawback litigation which is possible in a winding up, by making a payment to creditors, can also be a factor in favour of termination: cf Paton v Campbell Capital Ltd at 32. It is in a relevant sense “detrimental to commercial morality” to dispense with the opportunity which the winding up law provides for the investigation of the affairs of a failed company: Re Data Homes Pty Ltd (in liq) [1972] 2 NSWLR 22 at 26; Emanuele v Australian Securities Commission at FCR 69; ALR 520; ACSR 15.

[291] How much weight is given to the fact that the affairs of the company will not be investigated depends upon whether there are circumstances which suggest that investigation is called for. Sometimes, the fact that only a small dividend will be paid to creditors is itself such a circumstance: Lancaster v NZI Capital Corporation Ltd (Sheppard J, Federal Court of Australia, 3 September 1991 unreported, but quoted and approved in Paton v Campbell Capital Ltd at 32). Sometimes, the fact that it appears that there may be prospects of preference or uncommercial transaction or insolvent trading recoveries can be such a circumstance. In the present case, it is clear that only a small dividend will be paid to creditors, if any dividend at all. There is some basis for believing that insolvent trading recoveries might be possible, but the evidence concerning that topic is fairly slight, and any actual recoveries would depend on a liquidator obtaining the funding to sue.

96 Britax alleges that Mr Krejci did not exercise his casting vote at the creditors’ meeting in accordance with section 600B of the Act.

97 Section 600B provides:

(1) This section applies if, because the person presiding at the meeting exercises a casting vote, a resolution is passed at a meeting of creditors of a company held:

(a) under Part 5.3A or a deed of company arrangement executed by the company; or

(b) in connection with winding up the company.

(2) A person may apply to the Court for an order setting aside or varying the resolution, but only if:

(a) the person voted against the resolution in some capacity (even if the person voted for the resolution in another capacity); or

(b) a person voted against the resolution on the first-mentioned person’s behalf.

(3) On an application, the Court may:

(a) by order set aside or vary the resolution; and

(b) if it does so – make such further orders, and give such directions, as it thinks necessary.

(4) On and after the making of an order varying the resolution, the resolution has effect as varied by the order.

98 In Plumbers Supplies Co-operative Limited v Firedam Civil Engineering Pty Limited [2011] NSWSC 325 Barrett J stated:

[41] The function of the court under s 600B is not simply to come to a decision of its own as to how the casting vote should have been exercised and, if that decision differs from that made by the chairperson, to set aside the resolution and make orders implementing the decision that it thinks should have been made.

[42] The function of the court is, rather, to evaluate the decision-making process in which the chairperson engaged with a view to determining whether the decision was conscientiously made by reference to all relevant considerations appropriately identified and weighed by him or her.

99 Britax also submitted that a number of third parties (such as Infa-Secure, Quota, HBG and their directors) were potentially liable as accessories to breaches of duty by Richard Horsfall.

100 In order to establish accessorial liability, it must be shown that the alleged accessory assisted a fiduciary “with knowledge of a dishonest and fraudulent design on the part of the … fiduciary”: Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89 at [160]; Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244 (Barnes v Addy) at 251-252. Section 79 of the Act also provides that a person is involved in a contravention if, and only if, the person has aided, abetted, counselled or procured the contravention, or has been in any way, by act or omission, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention, or has conspired with others to effect the contravention.

G. SHOULD THE DEED BE SET ASIDE?

Britax’s First Argument – No Prejudice to Other Creditors

101 Britax contends that it is the only creditor that will be prejudiced if the Deed is set aside. It submits that the Administrators have estimated that there will be about $800,000 available to unsecured creditors pursuant to the Deed. Britax is likely to be overwhelmingly the largest creditor, with its debt accepted (for voting purposes only) at $8,593,500 as against all other creditors combined which have their debts admitted (similarly for voting purposes only) at $1,114,529.17. On the basis of the debts admitted for voting purposes, Britax submits that the entitlement of the other creditors under the Deed and Creditors’ Trust will be about $45,000, and $755,000 (or 9% of its entire debt admitted for voting purposes) would be available to Britax. Britax has, in the course of these proceedings, lodged $45,000 into Court on the basis that if these proceedings are successful, the interested unsecured creditors will be paid. Further, Britax has offered an undertaking to pay $200,000 as a contribution to fund any inquiries that the liquidators consider necessary in order to ascertain whether there are any claims to pursue against relevant parties. Accordingly, Britax reasons, it is the only party adversely affected by the setting aside of the Deed. There is no doubt that Infa, having sold all of its assets, can no longer trade and so it has no relevant interest. As a consequence, if Britax considers that there is a likelihood of a better return in a liquidation scenario, then its wishes must be respected and the Court must set aside the Deed.

102 Senior counsel for Britax frankly conceded during argument that he was unable to draw attention to any authority in support of this proposition.

103 Infa disputed this proposition, citing three authorities.

104 In Mediterranean Olives, Dodds-Streeton J noted (at [192]) that the plaintiffs could not establish viable causes of action or negative the administrators’ estimates of the probable nil return to the unsecured creditors on winding up. The plaintiffs submitted, however, that as the administrators’ investigations were inadequate and the Deed of Company Arrangement depended on the support of related creditors, the Court should, if outstanding issues reasonably called for further investigation, “readily uphold their bona fide preference, as the major independent creditors, for liquidation”, at [192]. Her Honour, at [193], said:

As Network and Portinex make clear, however, unless the outcome of the relevant resolution is contrary to the interests of the creditors as a whole, the defeat of a major creditor’s preference by the votes of related creditors is irrelevant.

105 In DCT v Portinex/Silindale/Dalvale [2000] NSWSC 99; (2000) 34 ACSR 391 (Portinex) ACSR 391 Austin J at [137] summarised the position as follows:

This is a case where by far the most substantial unrelated creditor has been outvoted by related creditors and now finds himself bound to arrangements to which he objects. He objects broadly on the grounds that the arrangement unduly benefit the director of the companies and that the administrator has made inadequate investigations. If there were nothing more to the case than this, the creditor may have at least a sound moral case for assistance. But Pt 5.3A clearly contemplates that the wishes of an individual creditor may be overridden, and permits related creditors to take part in the decision to do so, subject to s 600A.

106 In Network Exchange Pty Ltd v MIG International Communications Pty Ltd (1994) 13 ACSR 544; (1994) 12 ACLC 594 (Network Exchange), Hayne J also considered an application by the majority creditor of a company to have the administrator removed. The applicant identified the prejudice to creditors as being the inability of the biggest bona fide creditor to seek appointment of its own choice as administrator to preserve the undertaking of the company (at 549). His Honour found that it was insufficient to demonstrate, for the purposes of section 600A, that the major creditor had a strong and decided preference to have a person of its nomination as administrator of the company (at 550). Infa submitted that that reasoning applied equally to section 445D of the Act.

107 I agree with Infa’s submissions. In particular I conclude that there is no basis for Britax’s argument to apply such that the dominant position of one creditor, if thwarted, would necessarily prevail for the reason only that it is the only party likely to suffer prejudice if the Deed is set aside. I agree that the authorities cited support the proposition that the scheme of Part 5.3A of the Act does not permit the individual will of one creditor, even a creditor entitled to claim a most significant sum in the administration, to set aside the Deed without first establishing that the conditions of one or other of the sub-paragraphs of subsection 445D(1) have been satisfied. Whilst the role within section 445D(1) of the exercise of discretion (“the Court may make an order”) and the grounds identified in the subsections are interrelated, it is clear that the Court must first be satisfied that the requirements of one of the grounds be met: Recycling Holdings at [29]. Britax’s submission fails to take this legislative requirement into account.

108 I am reinforced in this view by examination of the subsections upon which Britax relies being subsection 445D(1)(e), (f) and (g) and section 600B.

109 Section 445D(1)(e) provides that the Court must be satisfied that “effect cannot be given to the Deed without injustice or undue delay”.

110 The subsection draws attention to the effect of the Deed rather than its purpose; Cresvale Far East v Cresvale Securities [2001] NSWSC 89; (2001) 37 ACSR 394 (Cresvale) per Austin J at [188]. The subsection may operate to enable relief where the Deed denied creditors the opportunity for the company to be wound up and voidable transactions investigated and pursued; Cresvale at [190] – [191].

111 In Cresvale, Austin J found (at [136]) that:

… facts would suggest to a reasonable person the real possibility, worthy of further inquiry, that Mr Kirwan may have breached his fiduciary duties or his statutory duties in respect of related party transactions and insider trading

112 On the basis of that finding, his Honour found that the Deed had the effect of foreclosing inquiry into Mr Kirwan’s conduct because, on the facts of that case, it prevented the winding up of the company which sold the assets to Mr Kirwan.

113 The “no prejudice to creditors” argument advanced by Britax does not sit conformably with the language of subsection (e). The desire of one substantial creditor to investigate, without first establishing (as noted by Austin J in Cresvale) a real possibility, worthy of further inquiry, of breach, is not sufficient.

114 Subsection 445D(1)(f) relevantly requires that the Deed or a provision of the Deed is, or would be, oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to one or more creditors or contrary to the interests of the creditors as a whole.

115 In deciding whether a deed is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial within the subsection, the Court will have regard to the following factors:

(1) the objects of Part 5.3A;

(2) the interests of other creditors, the company and the public;

(3) the comparable position of the creditor on a winding up compared with their position under the deed; and

(4) other relevant facts such as the relative position of all creditors under the Deed (that is, whether they are better off), the existence of a collateral benefit to the shareholders and the whole of the effect of the Deed;

TiVo, Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd (subject to deed of company arrangement) [2014] FCA 789; (2014) 9 BFRA 583 (TiVo) at [54], per Gordon J.

116 In the context of the present argument, subsection 445D(1)(f) is of no assistance to Britax. The subsection is prescriptive and, as the above authority indicates, requires at least a comparative analysis of the relative positions of the creditors under the Deed as opposed to a winding up. In this context it is to be noted that Britax’s submission somewhat overemphasises its role in the context of the creditors of the company. Whilst Britax has a dollar value dominance over the other creditors, it was one of 13 creditors who voted at the creditors’ meeting. It would not lightly be assumed that the 12 creditors who voted in favour of the Deed were behaving commercially irrationally or otherwise to protect interests other than their own.

117 Britax’s submission is that by reason of the payments it has offered to the remaining creditors, it is the only party who might be prejudiced if the Deed is set aside. Subsection 445D(1)(f) calls for consideration of whether or not, by entry into the Deed, the plaintiff would be prejudiced. In this argument, Britax points to no specific prejudice, but an absence of prejudice for the other creditors. Paradoxically, Britax relies on potential prejudice to it, not by reason of the Deed, but by reason of setting it aside because of the unknown effect of a liquidation. Put another way, Britax contends that it is prejudiced by not being able to enjoy the unquantifiable opportunity to benefit from a liquidation, which it contends is worth more to it as a creditor than the amount of $755,000 that it estimates that it would be likely to receive under the Deed.

118 Subsection 445D(1)(g) provides that the Deed may be terminated for “some other reason”.

119 This may be available “where the proposal for the [Deed of Company Arrangement] has a fraudulent or wrongful purpose or the [Deed of Company Arrangement] offers an unconscionable premium, contrary to public policy, as a bribe to creditors to support an arrangement under which the conduct of the directors will not be investigated”; TiVo at [58].

120 TiVo (at [59], citing Mediterranean Olives at [197]) also states that “[t]he circumstances in which a [deed] may be terminated are not closed. Each case will depend on its own facts and combination of circumstances, which must be mutually balanced”.

121 Senior counsel for Britax relied heavily upon TiVo, but I do not think that it assists its case. In TiVo the Court found that the public interest demanded that the deed of company arrangement be terminated under section 445D(1)(g) so that an independent third party, namely a liquidator, could conduct an inquiry into what counsel for the company conceded were the “legitimate concerns” (at [65]) raised by the administrator concerning four identified transactions. The facts of that case were significantly different to the present. In particular, the administrator in TiVo had reported no fewer than ten instances of failure by the company to provide information or records relevant to the four identified transactions. Further, the administrator had received no information to assess the asset position of the proposed target of the investigations to ascertain what value may be achieved by the company in the event that they were pursued (at [69], [71] and [72]). As a consequence, Gordon J found that the public interest demanded that the deed be terminated and an independent third party conduct an inquiry in respect of the conceded “legitimate concerns” (at [69]).

122 The argument advanced by Britax is that it would not be necessary to establish any “legitimate concerns” for the interest and desire of Britax as the dominant creditor by value to prevail. For the reasons identified that submission cannot be sustained.

123 Section 600B also provides no support for Britax’s submission. The approach to section 600B mandated by the case law is to weigh up all relevant factors to the casting of the vote, including whether any particular class of creditors will be unfairly prejudiced by the proposal, whether the meeting has been given all relevant information and whether the directors stood to gain an unfair advantage; Cresvale at [109] – [118] esp [117].