FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 796

ORDERS

HUNTER PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD (ACN 063 521 666) Applicant | ||

AND: | MARTEC PTY LTD (ACN 127 773 077) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 7 days the applicant is to file and serve a draft minute of its proposed orders and notify the respondent whether it proposes to pursue its claim for pecuniary relief.

2. The proceeding stand over to a date to be fixed for making of further orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NICHOLAS J:

Introduction

1 Before me is an application by the applicant for relief in respect of the respondent’s alleged infringement of the applicant’s Australian certified design registration No. 340171 (“the Registered Design”) for a ceiling fan hub. The Registered Design was applied for on 9 December 2011 (“the priority date”) and registered under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (“the Act” or “the 2003 Act”) on 6 January 2012.

2 The respondent does not dispute the validity of the Registered Design but it denies that it has infringed. All questions concerning the applicant’s entitlement to pecuniary relief will be heard and determined, if necessary, after the issue of infringement has been decided.

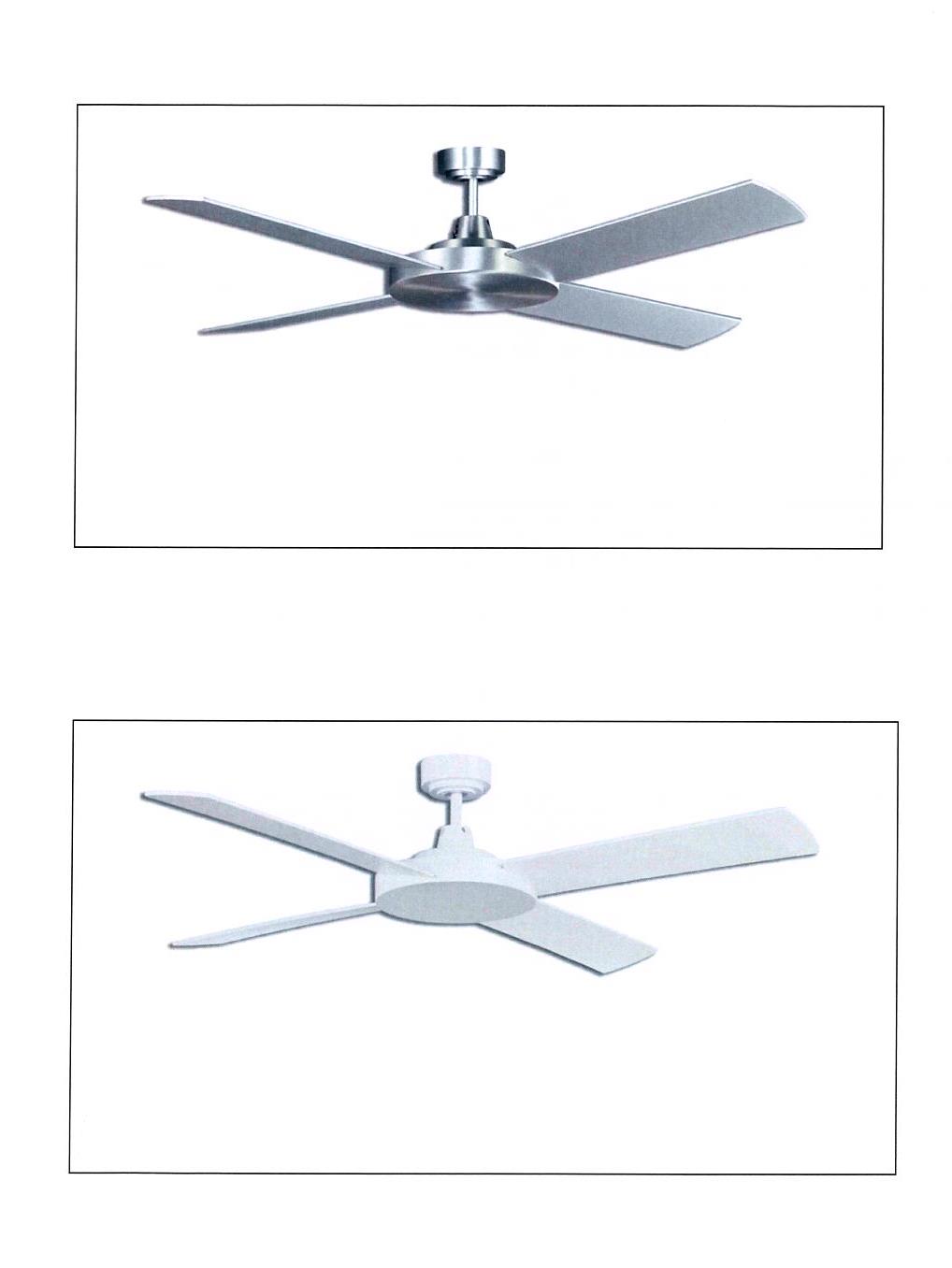

3 The respondent markets a product known as the Martec Razor (“the Razor”) which it admits it has imported for sale and sold. The applicant alleges that the Razor incorporates a ceiling fan hub that embodies a design that is substantially similar in overall impression to the Registered Design.

The Registered Design

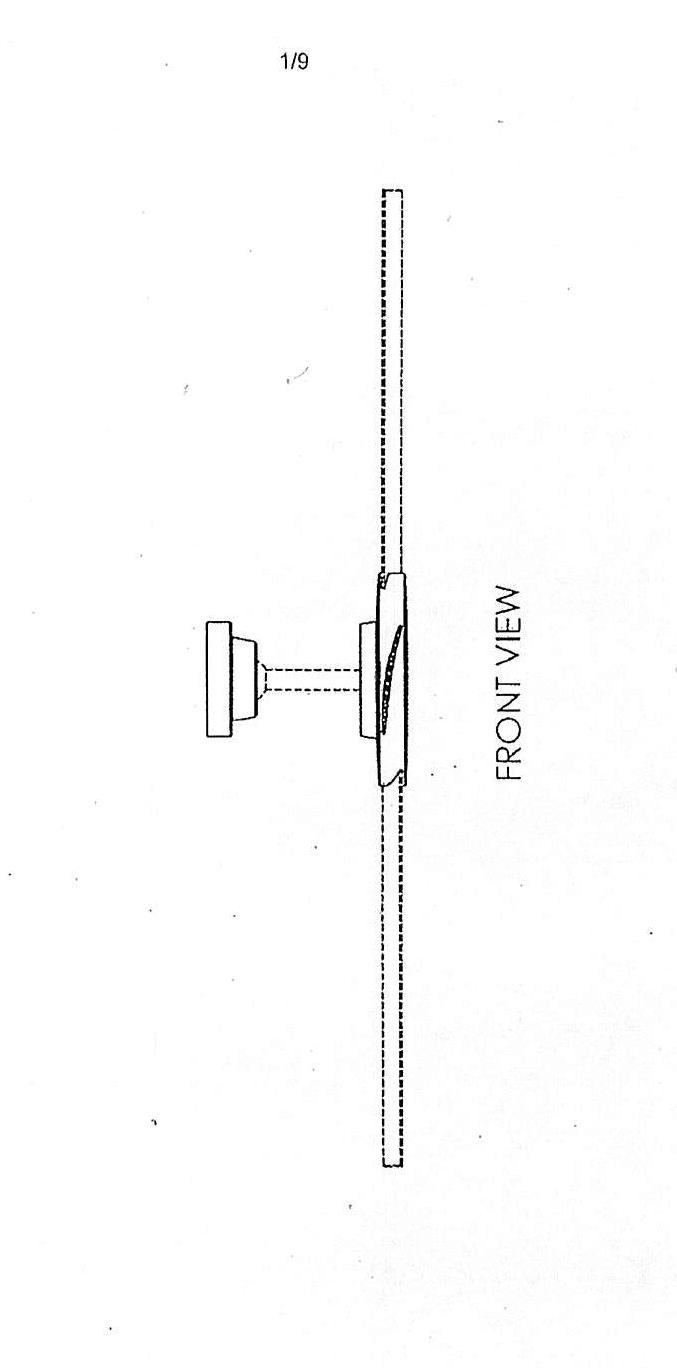

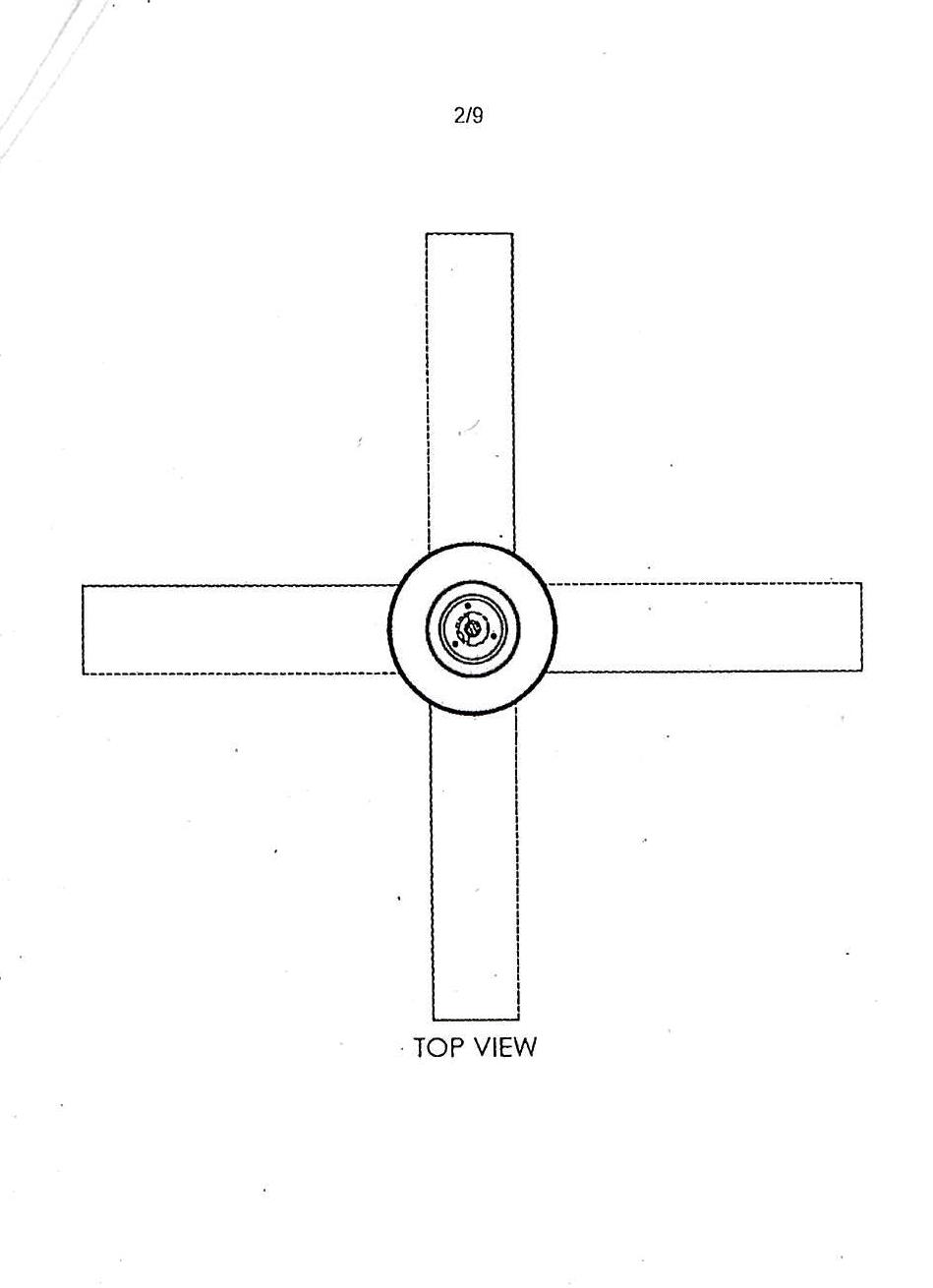

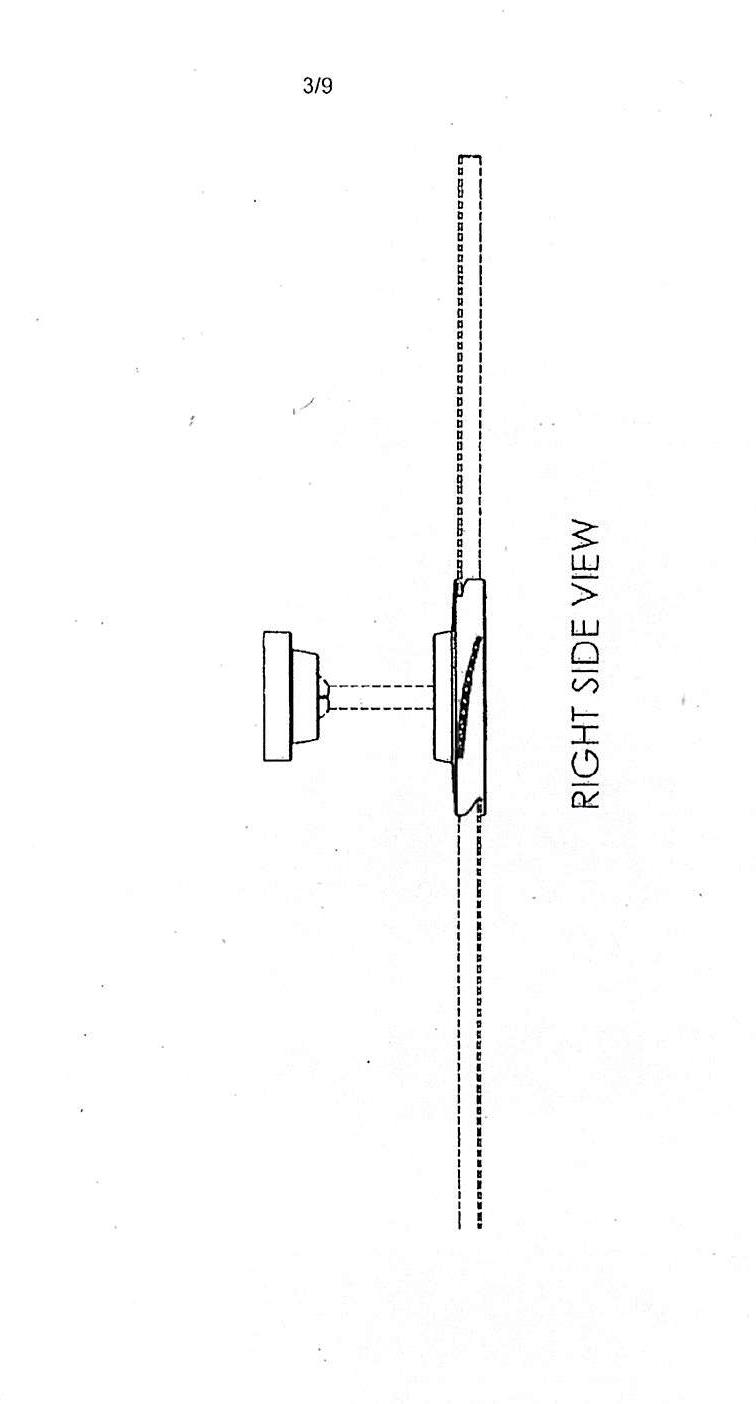

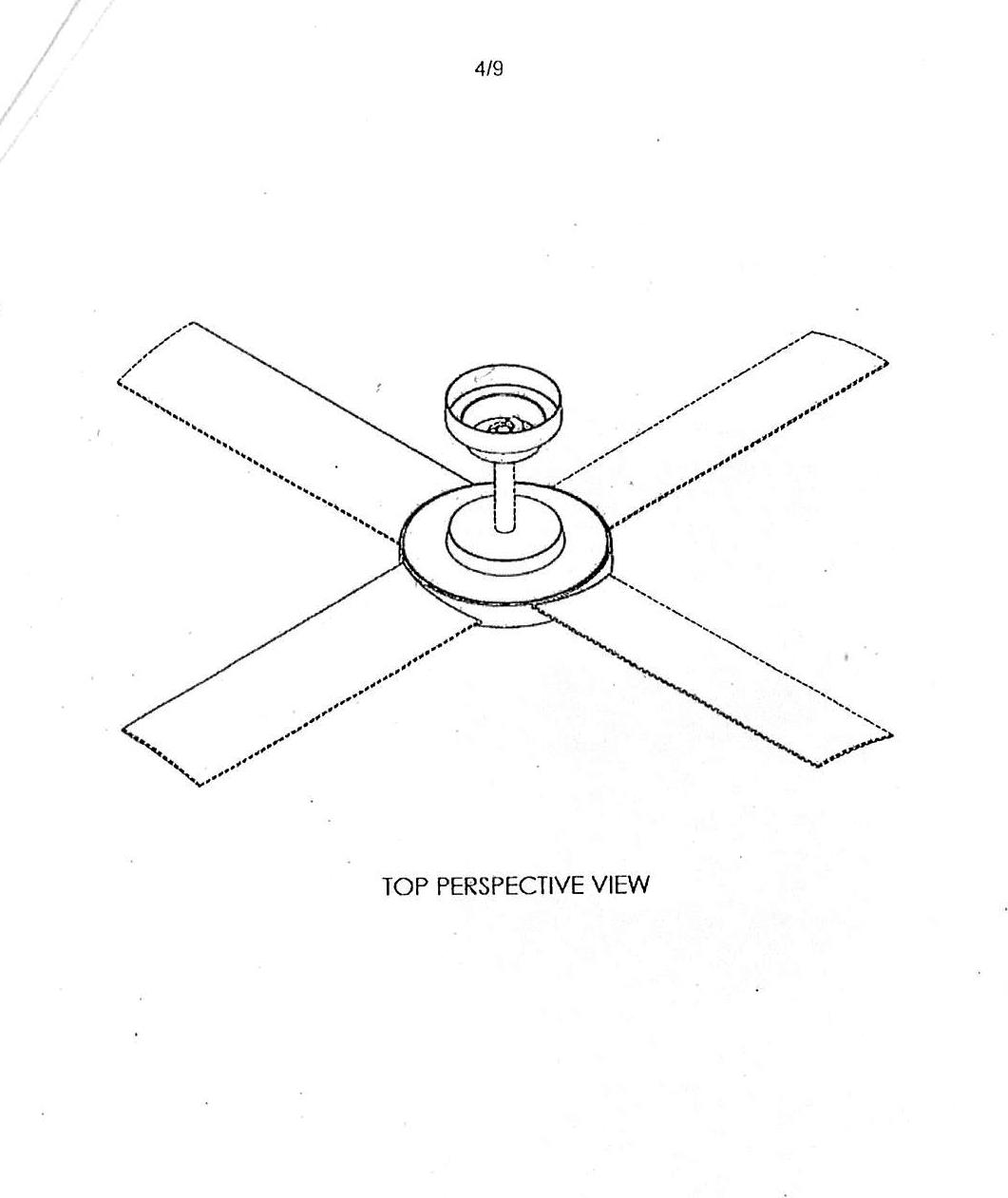

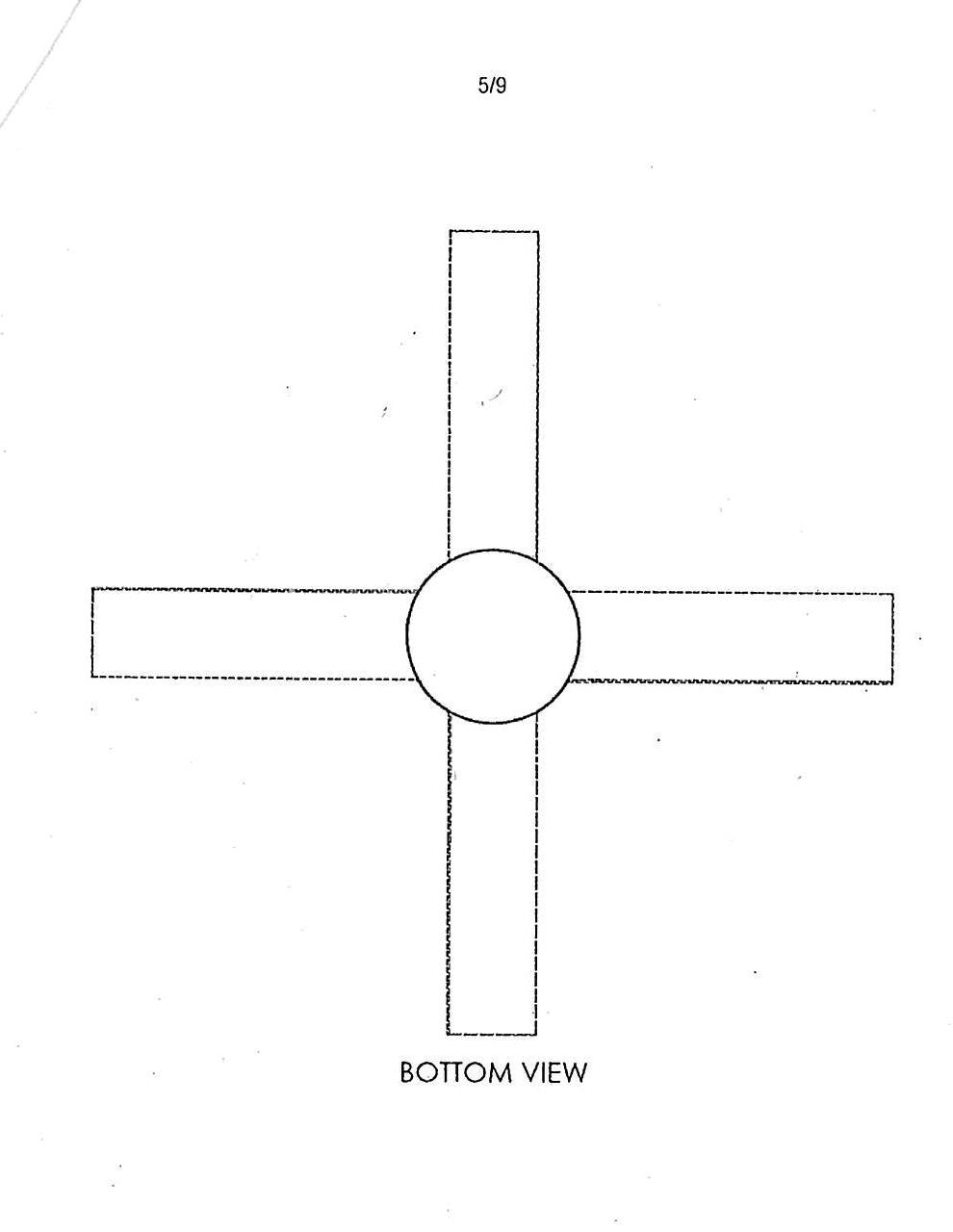

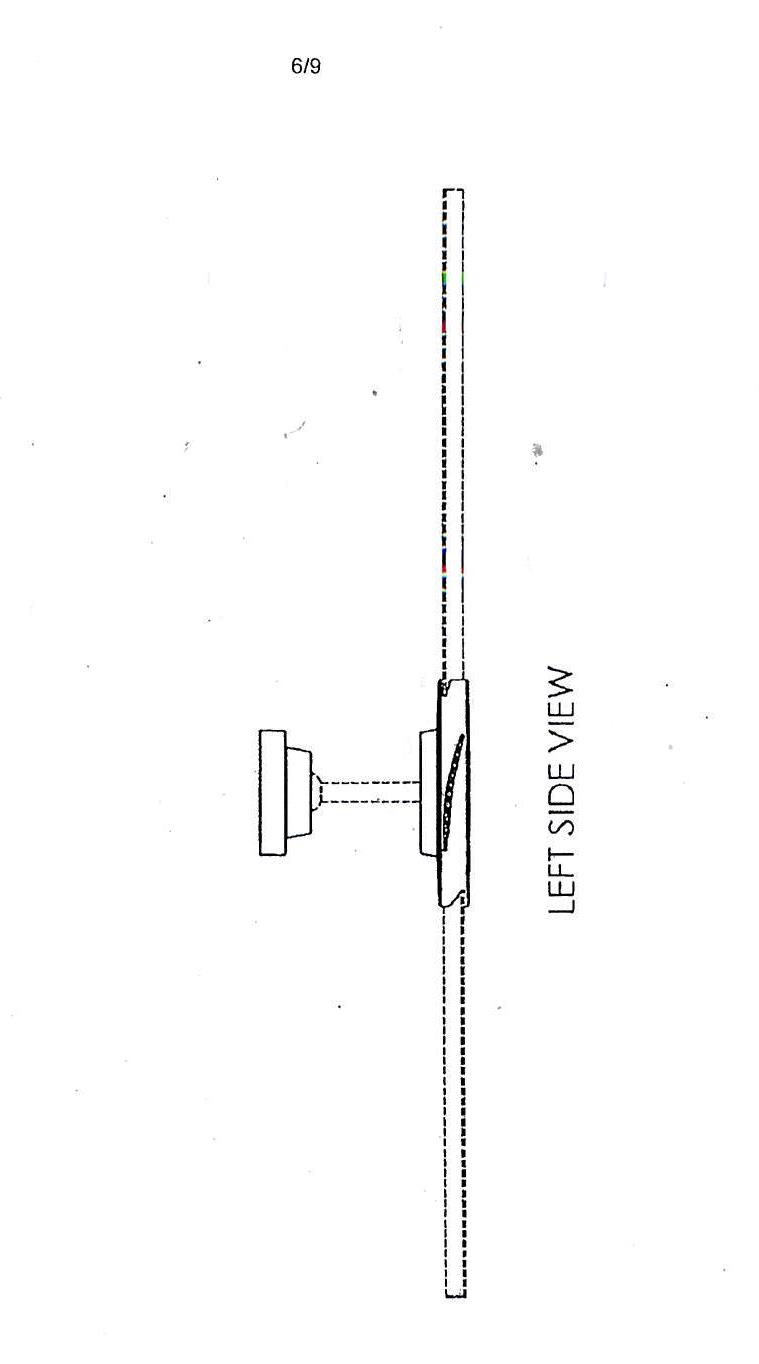

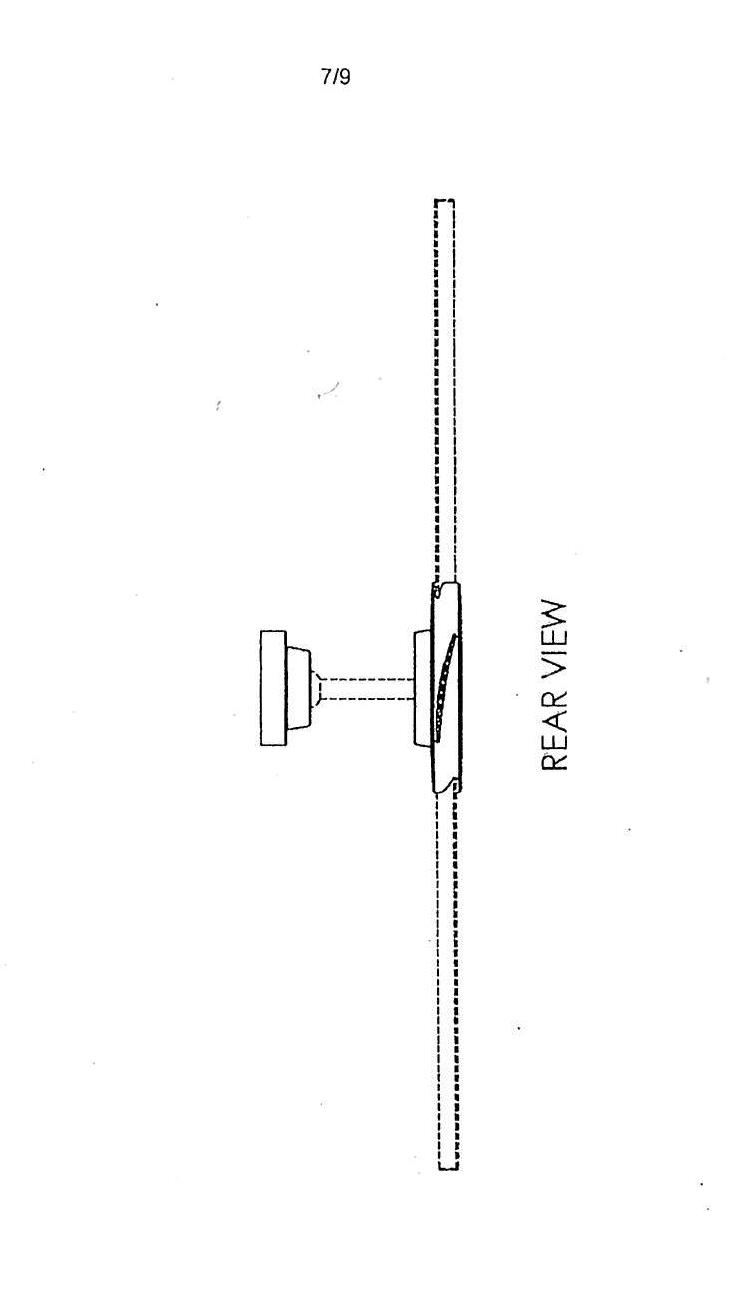

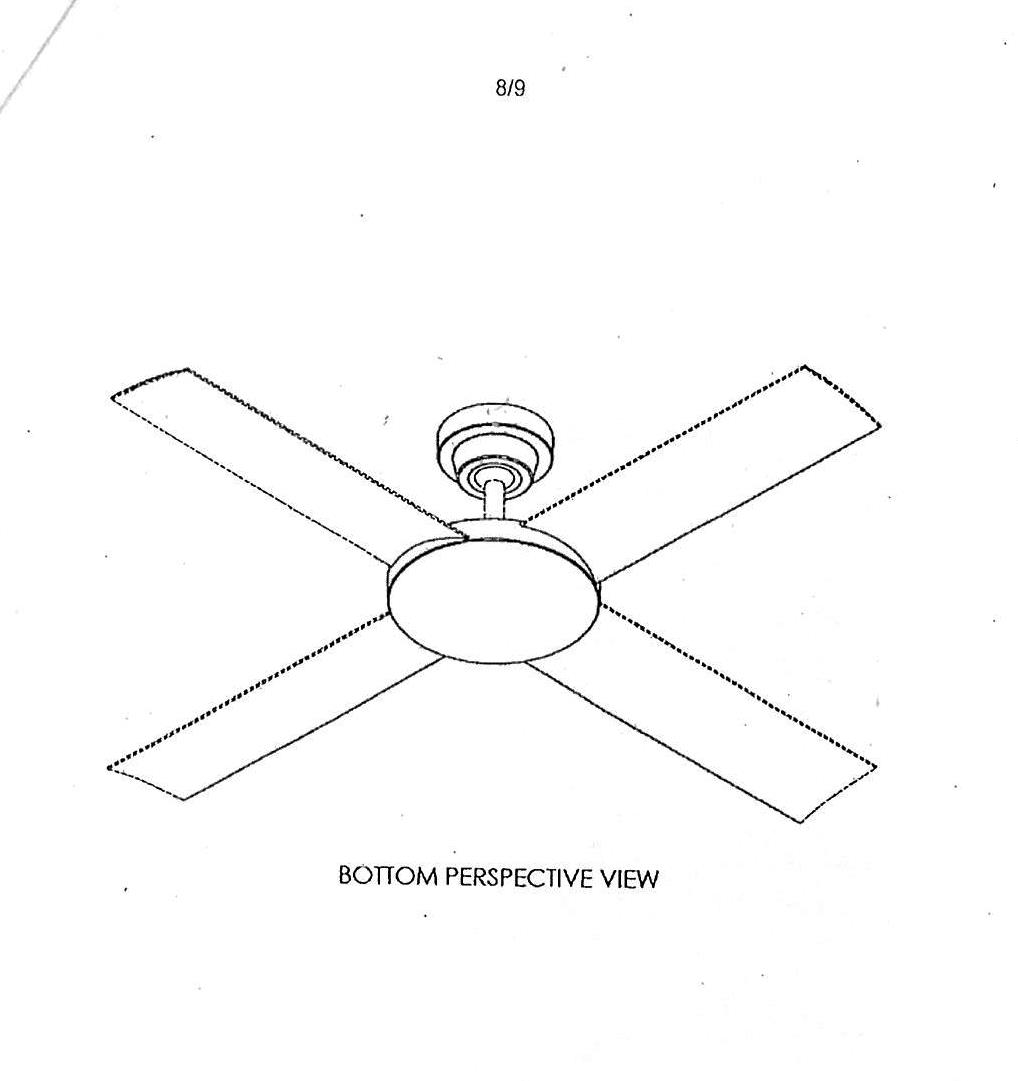

4 The Registered Design is depicted in nine drawings lodged in respect of the design application. The design application also includes a statement of newness and distinctiveness (“the statement of newness”) which states:

Newness and distinctiveness is claimed in the features of shape and/or configuration of the hub of a ceiling fan represented in solid lines in the attached drawings. In assessing newness and distinctiveness, no regard should be had of the shape and configuration of the fan blades as represented in broken lines, nor the number of fan blades.

5 Copies of the nine drawings depicting the ceiling fan hub of the registered design are included in Appendix 1 to these reasons and will be described as follows:

The Razor

6 The Razor is available in two finishes (brushed aluminium and white) which are depicted in Annexure A to the applicant’s originating application, and which are reproduced in Appendix 2 to these reasons. Nothing turns on the fact that the Razor comes in two finishes.

7 Appendix 3 to these reasons includes:

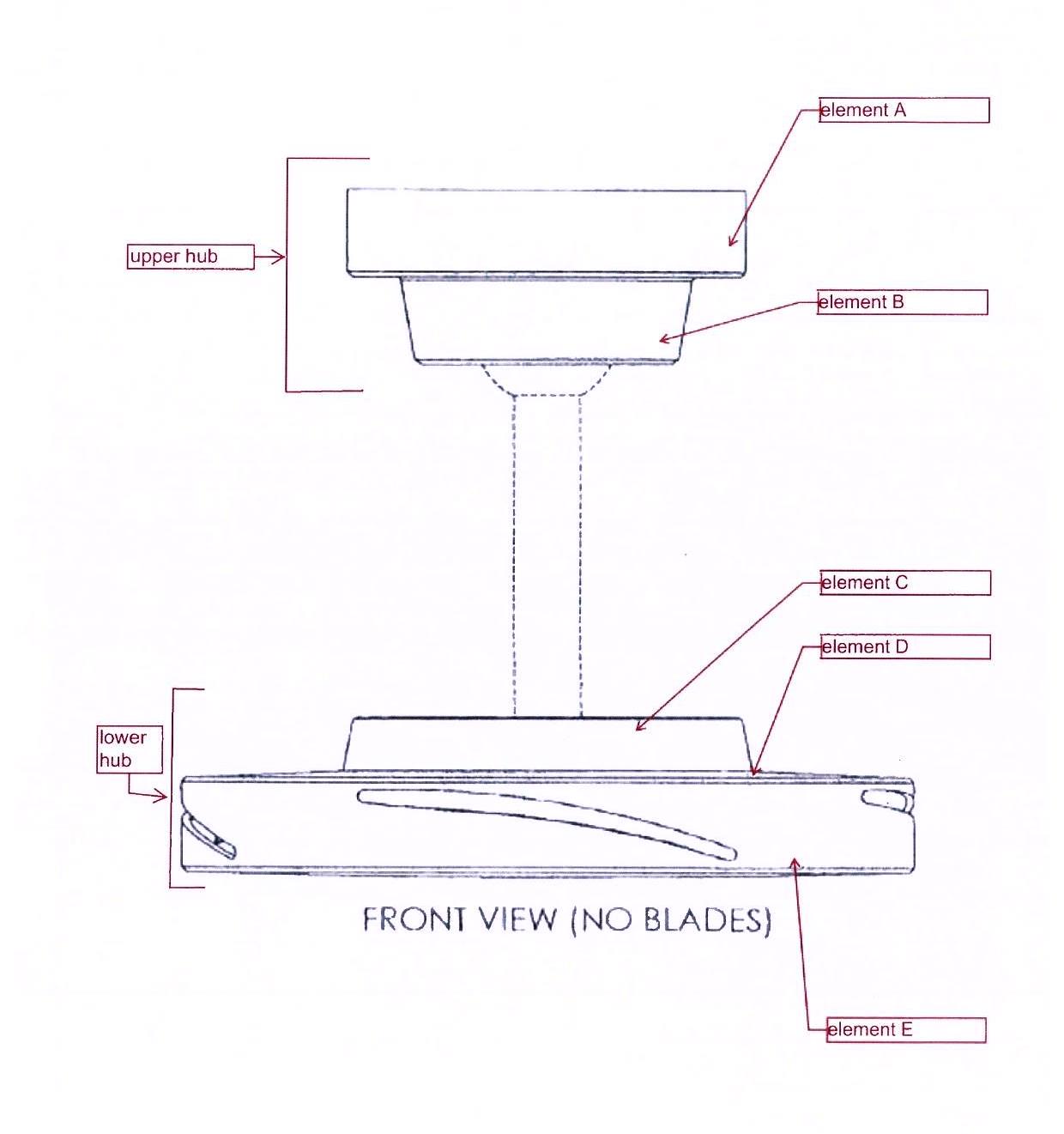

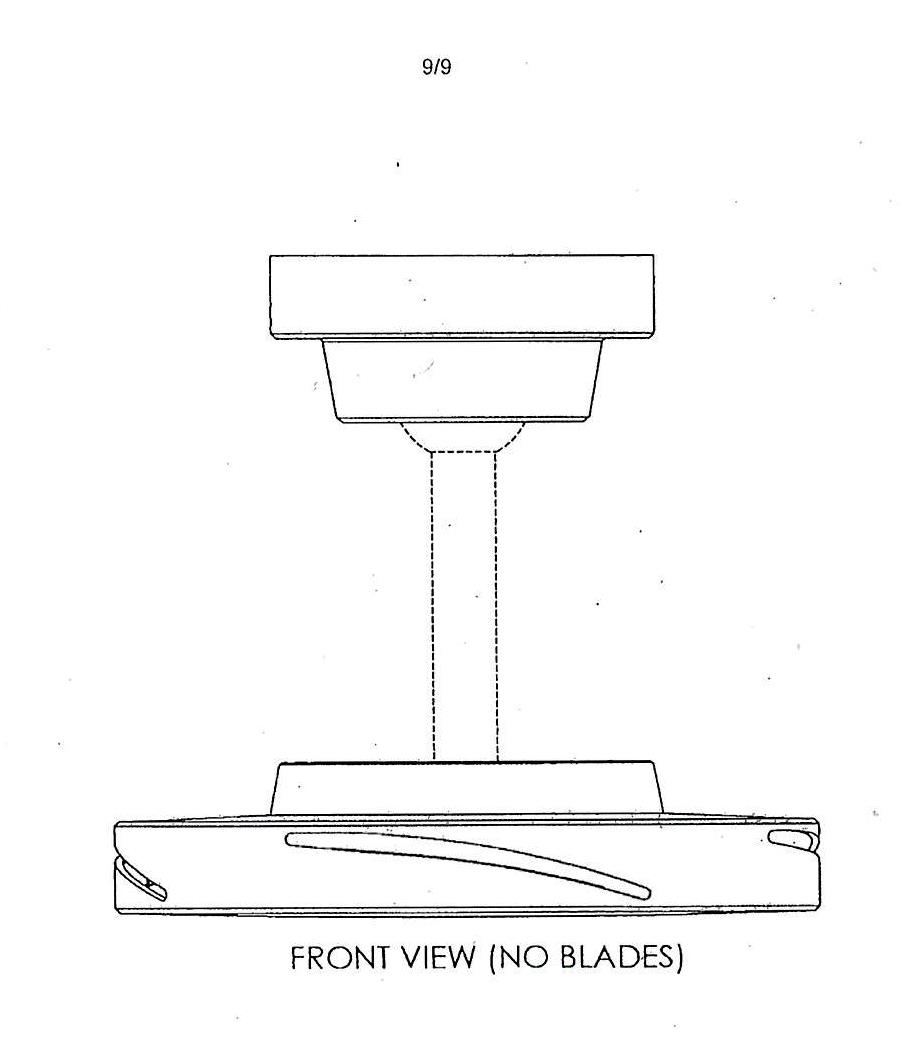

an annotated reproduction of Sheet 9/9 that identifies the upper hub and lower hub of the Registered Design and elements designated A-E (inclusive) that are discernible in this view viz. front view, no blades;

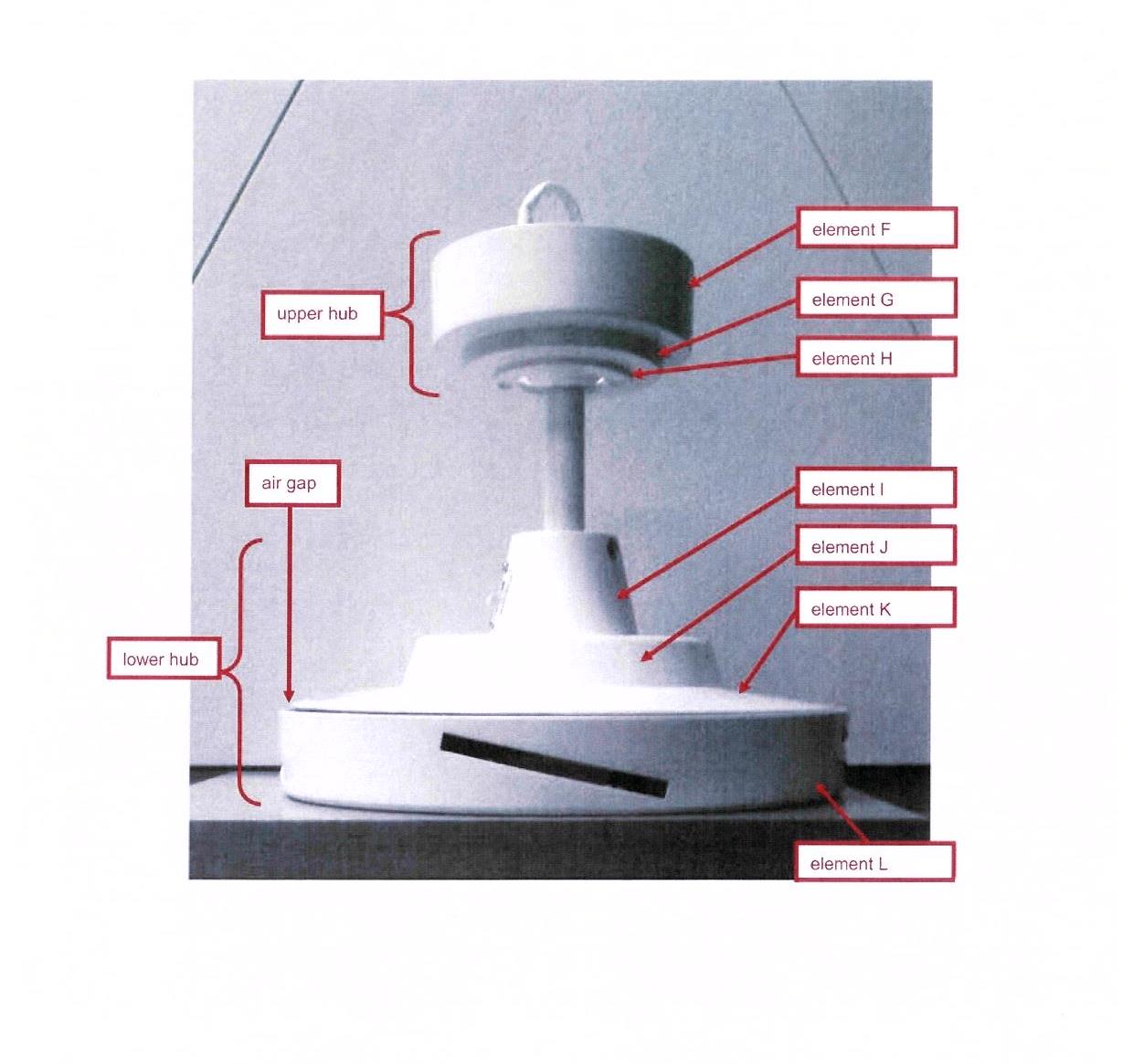

an annotated photograph of the Razor that identifies the upper hub and lower hub, the “air gap”, and elements designated F-L (inclusive) that are discernible in this view viz. front view, no blades.

8 These annotated documents were prepared by the applicant’s expert witness, Mr Tiller, whose evidence is discussed later in these reasons. In these reasons I have adopted the same designations (Elements A-E for the Registered Design and Elements F-L for the Razor) as used by Mr Tiller and as shown in Appendix 3.

The Relevant Statutory Provisions

9 Section 5 of the Act includes the following definition of “design”:

design, in relation to a product, means the overall appearance of the product resulting from one or more visual features of the product.

10 Section 7 of the Act includes the following definition of “visual feature”:

(1) In this Act:

visual feature, in relation to a product, includes the shape, configuration, pattern and ornamentation of the product.

(2) A visual feature may, but need not, serve a functional purpose.

(3) The following are not visual features of a product:

(a) the feel of the product;

(b) the materials used in the product;

(c) in the case of a product that has one or more indefinite dimensions:

(i) the indefinite dimension; and

(ii) if the product also has a pattern that repeats itself—more than one repeat of the pattern.

(emphasis original)

11 Section 10 of the Act confers on the registered owner of a registered design various exclusive rights including the right to make or offer to make a product which, in relation to which the design is registered, embodies the design (s 10(1)(a)), or to import for sale (s 10(1)(b)) or sell or offer for sale (s 10(1)(c)) any such product.

12 Section 71 of the Act relevantly provides:

(1) A person infringes a registered design if, during the term of registration of the design, and without the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design, the person:

(a) makes or offers to make a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; or

(b) imports such a product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(c) sells, hires or otherwise disposes of, or offers to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, such a product; or

(d) uses such a product in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) keeps such a product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d).

…

(3) In determining whether an allegedly infringing design is substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design, a court is to consider the factors specified in section 19.

…

13 Section 19 is in Chapter 2, Pt 4, Div 2 of the Act which is entitled “Substantial similarity in overall appearance”. Section 19 provides:

19 Factors to be considered in assessing substantial similarity in overall impression

(1) If a person is required by this Act to decide whether a design is substantially similar in overall impression to another design, the person making the decision is to give more weight to similarities between the designs than to differences between them.

(2) The person must also:

(a) have regard to the state of development of the prior art base for the design; and

(b) if the design application in which the design was disclosed included a statement (a statement of newness and distinctiveness) identifying particular visual features of the design as new and distinctive:

(i) have particular regard to those features; and

(ii) if those features relate to only part of the design—have particular regard to that part of the design, but in the context of the design as a whole; and

(c) if only part of the design is substantially similar to another design, have regard to the amount, quality and importance of that part in the context of the design as a whole; and

(d) have regard to the freedom of the creator of the design to innovate.

(3) If the design application in which the design was disclosed did not include a statement of newness and distinctiveness in respect of particular visual features of the design, the person must have regard to the appearance of the design as a whole.

(4) In applying subsections (1), (2) and (3), the person must apply the standard of a person who is familiar with the product to which the design relates, or products similar to the product to which the design relates (the standard of the informed user).

(5) In this section, a reference to a person includes a reference to a court.

(emphasis original)

14 The expression “prior art base” that appears in s 19(2)(a) is defined in s 15(2) of the Act. The prior art base relevantly includes designs publicly used in Australia and designs published in a document within or outside Australia before the priority date.

The Witnesses

Mr Robert Tiller

15 Mr Tiller is an experienced industrial design consultant who gave evidence for the applicant. He graduated from the University of South Australia in 1988 with a Bachelor of Design, Industrial Design. Between 1988 and 1997 he worked with a number of manufacturing companies in the area of product design. Mr Tiller established his own consultancy in 1997. He has experience in the design of a wide range of products including domestic appliances such as toasters, irons, mixmasters, frypans, clothes dryers, power boards, power points and BBQs. He made clear in his first affidavit that he had never designed or been involved in the design of a ceiling fan or ceiling fan hub. However, he did say that he was very familiar with ceiling fans and their parts as a result of seeing them in houses and other buildings (including his home) and selecting and purchasing ceiling fans from time to time.

16 For the purposes of making his first affidavit Mr Tiller was provided by the applicant’s solicitors with various two dimensional reproductions of eight ceiling fans that form part of the prior art. He identified these eight ceiling fans as follows:

(a) Prior Art Design A: the Vortex-3 52” (“Vortex”);

(b) Prior Art Design B: the HPM WATCF14J (“Rexel”);

(c) Prior Art Design C: the Futura 122cm (“Futura”);

(d) Prior Art Design D: the Hunter Pacific Concept 1 (“Concept 1”);

(e) Prior Art Design E: the Hunter Pacific Concept 2 (“Concept 2”);

(f) Prior Art Design F: the Airfusion Climate 52 DC (“Airfusion”);

(g) Prior Art Design G: the Sycamore (“Sycamore”);

(h) Prior Art Design H: the Grenada (“Grenada”),

(collectively, the “Prior Art Designs”).

17 In his oral evidence Mr Tiller said that he had at some previous time purchased a Concept 1 and a Concept 2 which are installed in his house.

18 In Mr Tiller’s opinion, the Registered Design and the Razor have a very similar shape and configuration, each having a sleek, thin and flat aesthetic. In his opinion the differences between them are relatively few, and they concern parts of the design that provide minimal visual impact to the overall design aesthetic. He also said that many of the similarities he observed between the two designs are not present in the Prior Art Designs.

19 Mr Tiller identified the following similarities between the Registered Design and the Martec Razor :

(a) The first element of the upper hub of the Registered Design (Element A) and the first element of the upper hub of the Martec Razor (Element F) are both cylinders and are very similar in size, shape and proportion (and may perhaps be the same);

(b) The first element of the lower hub of the Registered Design (Element C) and the second element of the lower hub of the Martec Razor (Element J) are both conical shapes and are very similar in size, shape and proportion (and may perhaps be the same);

(c) The shallow conical bowl of the lower hub of the Registered Design (Element D) and the shallow conical bowl of the Martec Razor (Element K) are very similar in size, shape and proportion (and may perhaps be the same);

(d) The third element of the lower hub of the Registered Design (Element E) and the fourth element of the lower hub of the Martec Razor (Element L):

(i) appear to be the same in size, shape and proportion;

(ii) both have a chamfered lower edge furthest from the ceiling, which appear to be the same;

(iii) both have angled cut-outs for the fan blades;

(iv) both have a flat underside furthest from the ceiling; and

(e) The lower hub of the Registered Design and the lower hub of the Martec Design both have air gaps between the shallow conical bowl and the lower cylindrical portion.

20 Mr Tiller identified the following differences in design between the Registered Design and the Razor:

(a) The conical shape in the upper hub of the Registered Design (Element B) is different from the two cylindrical shapes in the upper hub of the Martec Razor (Elements G and H);

(b) The Registered Design does not have the conical shape in the lower hub that is present in the Martec Razor (Element I);

(c) The fourth element of the lower hub of the Martec Razor (Element L) does not have a chamfer on its upper edge; and

(d) The second element of the lower hub of the Martec Razor (Element K) has screw holes and concentric slots, which are not visible on the Registered Design.

21 Mr Tiller’s comparison of the Registered Design and the Razor focused upon the front view of the former and what I would broadly characterise as the front view of the Razor. In his oral evidence, he suggested that this view of the Razor was not a true front view, because as I understood his evidence, the device is not in a precisely vertical orientation relative to the camera with which the photograph was taken. Even so, Mr Tiller accepted that the presence of the conical canopy cover (Element I) in the Razor is a conspicuous difference between it and the Registered Design.

22 In Mr Tiller’s oral evidence it became apparent that he attached considerable importance to the close similarity between the lower motor housing for each of the two fan hubs, especially Element E and Element L. He accepted that the lower hub of the Razor had a bulkier appearance than that of the Registered Design, but did not accept that it would be perceived in this way. He emphasised that the Registered Design and the Razor are both designed to be fixed to a ceiling, with the fan being viewed from an upwardly projecting angle, and that Element L of the Razor (Element E for the Registered Design) would then be the dominant visual element. He explained that the upper edge of Element L would create a visual barrier which may, as I understood his evidence, obscure Element I (the canopy cover) from view. He accepted in cross-examination that this view was not based upon a view of a Razor that had been installed, but was instead based upon his own visualisation of how the Razor would appear when installed on a ceiling. He considered that the lower hub, taken as a whole, for both the Registered Design and the Razor would be considered “thin”.

Mr William Hunter

23 Mr Hunter is a mechanical engineer who was called by the respondent. He graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering Science (Mechanical) in 1982 and a Masters of Engineering Science (Mechanical) in 1985 from the University of Melbourne. Mr Hunter has worked in a variety of engineering related fields including managing the consumer products and packaging business unit of Invetech Australia. Mr Hunter made three expert reports.

Mr Hunter’s first report

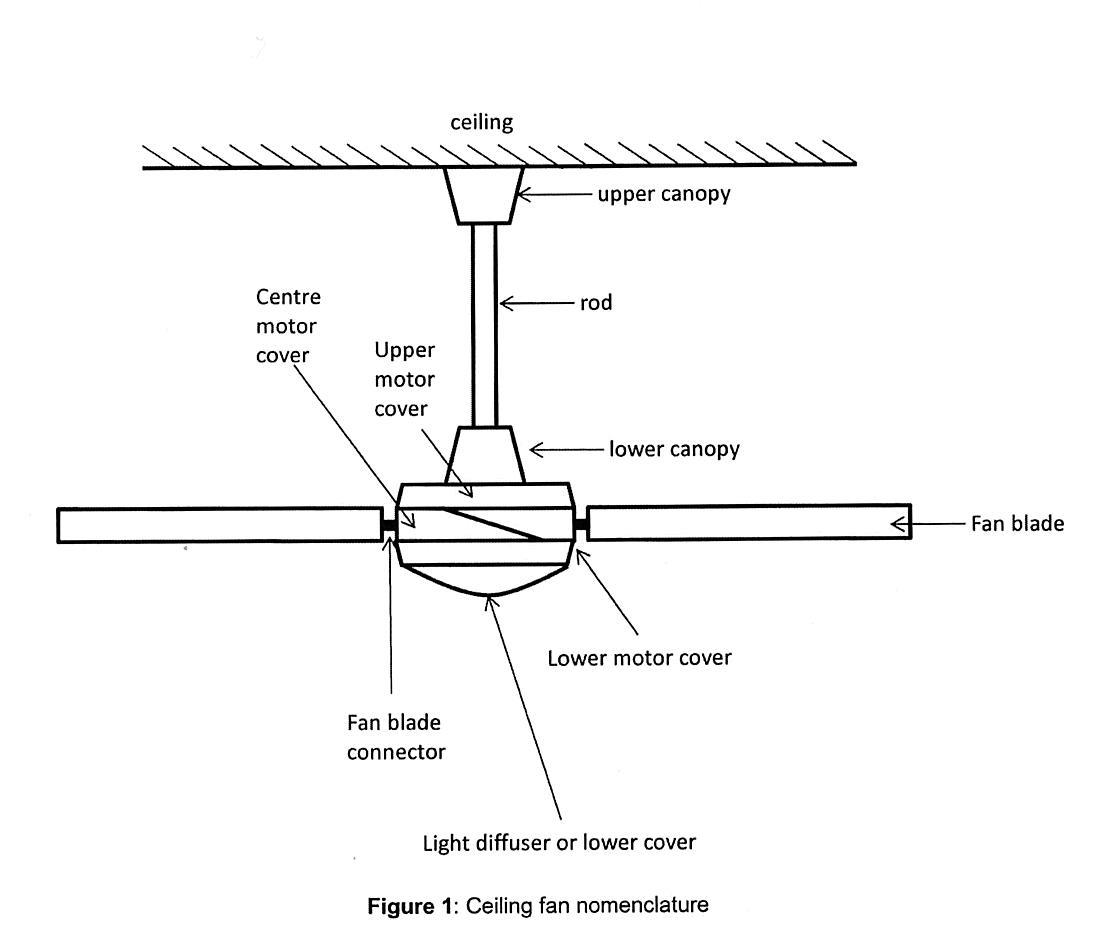

24 Mr Hunter’s first report was primarily concerned with ceiling fan design. He included in the report the following diagram (Figure 1) in which he identified the various parts of a typical ceiling fan:

25 He explained that the various components identified in his Figure 1 are not always used (eg. the lower canopy) and some components may be integrated together as a unitary component (eg. the upper motor cover may be integrated with the lower and centre motor covers). None of this evidence was controversial.

26 Mr Hunter referred in his first report to the various ceiling fans (though not by name) including the Vortex (Prior Art Design A), the Futura (Prior Art Design C), the Concept 1 (Prior Art Design D), the Airfusion (Prior Art Design F), the Sycamore (Prior Art Design G) and the Grenada (Prior Art Design H). He described a number of considerations relevant to ceiling fan design including the need for an upper canopy cover to shield components (including AC wiring and connectors) around the point where the fan is fixed to the ceiling. He also referred to the following considerations that constrain the design of the upper canopy:

the shape of the upper canopy is necessarily going to be a surface of revolution (ie. a body of round cross-section);

the upper canopy must be hollow and possess the internal volume to cover the fan body mounting bracket;

the lower aperture of the upper canopy must be of a relatively small diameter to cover the relatively small diameter mounting rod;

the upper aperture of the upper canopy must be of a larger diameter to cover the fan body to mounting rod bracket.

27 He said that the geometrics of the upper canopy will transition in a conical shape (eg. “bell” shapes, hemispheres or cylinder shapes) from widest at the ceiling end of the upper canopy to narrowest at the fan end of the upper canopy.

Mr Hunter’s second report

28 Mr Hunter’s second report included an analysis of the upper canopy, the upper motor cover and the lower motor cover of the Registered Design as depicted in Sheet 9/9. He identified the upper canopy as consisting of two parts, an upper squat cylindrical portion which transitioned into a lower truncated cone portion, widening toward the ceiling. He sought to confirm some of these observations by taking measurements applying a metal rule to Sheet 9/9 and calculated a diameter-to-height ratio of the upper cylindrical portion of 5:1 and an included angle of 17.5° for the lower truncated cone portion of the upper canopy. Mr Hunter described the overall external visual shape of the upper canopy as a compound of a cylinder (Element A) and truncated cone (Element B).

29 Turning to the upper motor cover, Mr Hunter described it as having an upper truncated cone portion (Element C) that is fairly squat with a relatively high diameter-to-height ratio and an included angle which he calculated at 21°. He calculated the lower cone portion (Element D) to have an included angle of 176° and noted that this is very close to a flat surface. He described the upper motor cover as a shape which is a compound of two truncated cones.

30 Mr Hunter also referred to the lower motor cover (Element E) which he described as having a very slight spherical radius, and he suggested that this surface would reflect light differently from a flat surface. Looking at the Registered Design as a whole, Mr Hunter said that it was sleek and contemporary in shape with a component body height that minimises the visual intrusion of the fan body into the room space.

31 Mr Hunter provided a similarly detailed account of the shape of the Razor including measurements of the diameter-to-height ratios of the upper cylindrical portion (Element F), the middle cylindrical portion (Element G) and the lower cylindrical portion (Element H). He calculated these to be 3:2, 10:1 and 17:5 respectively. He described the overall visual appearance of the upper canopy as a compound of three stepped cylinders, each progressively reducing in diameter.

32 Mr Hunter described the upper motor cover as comprising a lower canopy portion (Element I), a middle truncated cone portion (Element J), and a lower truncated cone portion (Element K). He calculated the included angle of each of these portions as 26°, 27° and 162°. He described the upper motor cover as a shape which is a compound of three truncated cones. According to Mr Hunter, the lower motor cover consists of a cylindrical portion (Element L) with a flat bottom surface (which he confirmed by placing his rule along the surface). He measured the dimensions of the cylindrical portion and calculated that it had a height-to-diameter ratio of 7:2. He also drew attention to the cut-out apertures (which receive the fan blades) which he said were of a specific shape that would suit flat angled fan blades only.

33 Mr Hunter’s second report next proceeded to identify the similarities and the differences between the Registered Design and the Razor. In Mr Hunter’s opinion the primary differences include:

The Razor has an upper canopy shape that is visually significantly different from that of the Registered Design. He referred here to the various differences he previously identified including his measurement of diameter-to-height ratios and included angles.

The Razor has an upper motor cover shape visually significantly different from the Registered Design. The Razor’s upper motor cover includes three truncated cones with varying included angles which, in his opinion, contributed to the significantly different visual appearance.

The Razor has a visually different lower motor cover with differently shaped cut-out apertures. In particular the bottom surface in the Registered Design is slightly spherical. The cut-out apertures shown in the Registered Design are curved as opposed to straight. The bottom of the lower motor cover of the Razor is flat rather than spherical.

34 Mr Hunter was asked to comment on the relative distinctiveness of the Registered Design when compared to the Razor and the Prior Art Designs. In his report he expressed the opinion (which was not objected to) that it was highly unlikely that the Registered Design and the Razor could not be easily visually distinguished by an observer. He also expressed the view in his second report that neither the Registered Design nor the Razor are visually similar to the Prior Art Designs.

Mr Hunter’s third report

35 Mr Hunter’s third report responds to Mr Tiller’s affidavit. It shows that there are a number of matters upon which both experts agree including Mr Tiller’s description of the Prior Art Designs, and the fact that, as at the priority date, a designer of a ceiling fan hub would have had substantial freedom to innovate. On many other points Mr Hunter disagreed with Mr Tiller. Many of the points of disagreement relate to matters that are relatively insignificant including, for example, whether the bottom surface of the lower motor cover was flat or, as Mr Hunter maintained, slightly spherical.

36 In cross-examination Mr Hunter stated that he was not provided with all of the Prior Art Designs for the purpose of expressing his opinions and he did not think that he received Prior Art Design E (Concept 2) even though, as I read his evidence, he expressly refers to it in his third report. Mr Hunter was asked in cross-examination whether the Prior Art Designs have a motor cover that resembles the Registered Design. He suggested that Prior Art Design E (Concept 2) had a motor cover that had considerable similarity to the motor cover of the Registered Design. However, in his third report Mr Hunter appears to have accepted that Prior Art Design E (Concept 2) had a bulkier and heavier appearance than the Registered Design.

37 Mr Hunter was also cross-examined with a view to establishing that a person of average height, standing on the floor of an average size room, would be unlikely to see the lower canopy (Element I), the middle truncated cone portion (Element J) or the lower truncated cone portion (Element K). Evidence given by Mr Hunter in this part of his cross-examination was guarded and qualified, although that is not intended by me as a criticism of his evidence. The generality of a number of some of the questions he was asked on this topic invited qualified answers. As a result, I did not find this evidence particularly helpful.

The Relevant Principles

38 The question that must be decided under s 71(1) is whether the Razor embodies a design that is substantially similar in overall impression to the Registered Design. Since the word “design” is defined for the purposes of the Act to mean the “overall appearance” of the product resulting from its “visual features” the question whether two designs are substantially similar is to be decided on the basis of a visual comparison of the shape and configuration of the two designs. In deciding this question the Court must have regard to the requirements of s 19 of the Act.

39 The question whether two designs are substantially similar is ultimately a question for the Court to decide applying the standard of the “informed user”. The informed user is a notional person who is taken to be familiar with the product to which the design relates or products similar to the product to which the design relates. The informed user will also be taken to have a familiarity with the Registered Design and the product that is alleged to infringe based upon a careful and deliberate visual inspection. Section 19 of the Act contemplates that the Court will have regard to all the similarities and the differences between the visual features of the two designs in coming to its ultimate conclusion. Hence, the relevant comparison cannot be based upon a fleeting or casual inspection of the drawings or object in question or some “imperfect recollection” of either of them. That is not to deny that the comparison to be undertaken is essentially impression based. I therefore respectfully agree with the following statement of Yates J in Multisteps Pty Ltd v Source and Sell Pty Ltd (2013) 214 FCR 323 at [55]:

… although the test is based on impression, it is not based merely on a casual comparison between designs for a given article. There needs to be a studied comparison based on the prescriptions of s 19 of the Designs Act. Thus, the notion of “imperfect recollection” — familiar in trade mark law — has no application when determining design similarity …

40 In the present case the informed user should also be taken to be a person who has an understanding of the manner and extent to which the design of a ceiling fan hub is dictated by function: Procter & Gamble Co v Reckitt Benckiser (UK) Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 936; [2008] FSR 8 at [29].

41 It is, of course, necessary to focus on the overall impression created by the two designs. This is done not by ignoring matters of detail, but by assessing the impact of particular visual features, including any matters of detail, on the overall impression created by each of the two designs. It is the overall impression that constitutes the critical measure of comparison. In Vinidex Tubemakers Pty Ltd v Griffen Brook Pty Ltd (1991) AIPC 90-839 Foster J said (at 37,954):

Clearly a balanced consideration is required, one that focuses upon the total impression created by the respective material, but does not ignore matters of detail, particularly where those matters appear readily on inspection.

His Honour was dealing with an allegation of “obvious imitation” under the Designs Act 1906 (Cth) (“the 1906 Act”) but I think His Honour’s observation also provides useful guidance for assessing whether two designs are “substantially similar in overall appearance” under the 2003 Act.

42 The change of language from “fraudulent or obvious imitation” (see s 30(1) of the 1906 Act) to “substantially similar in overall impression” as a criterion of liability for infringement was a key component of a collection of measures aimed at ensuring that liability for infringement of a registered design was not avoided merely because an allegedly infringing product had an appearance that differed in minor and insignificant respects from that of the registered design. As to the words “substantially similar in overall impression” the Australian Law Reform Commission (“ALRC”) in its report on Designs, ALRC Report No 74, “Designs”, 1995 (“the ALRC Report”), said (at para 6.7):

The courts have used and interpreted the expression ‘substantially similar’ on many occasions in the context of infringement of intellectual property. It is desirable to use words with which practitioners and the courts are familiar. The word ‘substantially’ is preferred to ‘significantly’ because ‘substantially’ has already been interpreted in a copyright context to be a qualitative and not quantitative term. The qualitative test is useful to determine designs infringement without importing a copying criterion. A qualitative test will assist the courts in evaluating the importance of the similarities and differences between competing designs. The recommended words are also less onerous than ‘obvious imitation’ which requires striking similarity and implies copying. The phrase ‘overall impression’ is preferred because it encourages the court to focus on the whole appearance of competing designs instead of counting the differences between them.

(citations omitted)

The reference to copyright law in this context is particularly significant in light of s 19(2)(c) of the Act about which I will say more shortly.

43 Section 19(1) of the Act requires the Court to give more weight to the similarities between the designs than to the differences between them. This requirement was the subject of a recommendation by the ALRC. The ALRC stated (at para 6.24 of the ALRC Report) that the focus on similarities would help to overcome the narrow approach of limiting protection to one individual and specific appearance of the article bearing the design.

44 Section 19(2)(a) requires the Court to have regard to the state of the development of the prior art base for the design. This is the approach that was usually taken under the 1906 Act but s 19(2)(a) explicitly requires that this be done. The approach under the 1906 Act was explained in Dart Industries Inc v Décor Group Pty Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 403 by Lockhart J at 409:

The scope of a registered design must be determined with reference to the background of the prior art at the priority date and questions of infringement and novelty or originality are connected. In Hecla Foundry Co v Walker, Hunter & Co (1889) 14 App Cas 550 Lord Herschell said at 555: “ ... one may be able to take into account the state of knowledge at the time of registration, and in what respects the design was new or original, when considering whether any variations from the registered design which appear in the alleged infringement are substantial or immaterial.”

Where novelty or originality is discovered in slight variations, there cannot be infringement without a very close resemblance between the registered design and the article alleged to be an infringement of the design. Lloyd-Jacob J in Rosedale Associated Manufacturers Ltd v Airfix Products Ltd [1956] RPC 360 at 364 said that the court would have regard to what was “known and old”, and: “ ... if the particular features which provide a novel conception have not been reproduced in the alleged infringement, the similarity of appearance between the article complained of and the registered design if present must necessarily reside in the common possession of characteristics which are free to everybody to employ.” See also Macrae Knitting Mills Ltd v Lowes Ltd (1936) 55 CLR 725 per Dixon J at 731 and L J Fisher & Co Ltd v Fabtite Industries Pty Ltd (1978) 49 AOJP 3611 per Fullagar J at 3620.

Small differences between the registered design and the prior art will generally lead to a finding of no infringement if there are equally small differences between the registered design and the alleged infringing article. On the other hand, the greater the advance in the registered design over the prior art, generally the more likely that a court will find common features between the design and the alleged infringing article to support a finding of infringement […]

(some citations omitted)

45 Section 19(2)(b) requires the Court to have regard to any particular visual features of the design identified in any statement of newness and distinctiveness included in the design application. If the design application includes such a statement identifying any such visual features, then the Court is required to have “particular regard” to those features. Again, this is the approach that was usually taken under the 1906 Act but the 2003 Act now includes an explicit requirement to this effect: cf. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Pty Ltd v Avion Engineering Pty Ltd (1991) 103 ALR 239 at 246-247.

46 Section 19(2)(c) requires that if only part of the design is substantially similar to another design, the Court must have regard to the amount, quality and importance of that part in the context of the design as a whole. This is significant in two respects. First, it assumes that a product may be substantially similar in overall impression to a registered design even though a particular part of the product is not substantially similar to the corresponding part of the registered design. Secondly, it requires the Court to make a qualitative rather than a purely quantitative assessment of the visual similarities and differences between the two designs when deciding upon the question of infringement in much the same way as it must when applying the test of substantiality in the field of copyright law.

47 Section 19(2)(d) also requires the Court to have regard to the freedom of the creator of the design to innovate. This reflects what has been a long standing concern that registered designs not impede the natural and ordinary growth of industry by preventing others from making products that have features of shape and configuration that are common to a trade: see Le May v Welch (1884) 28 Ch D 24 at 34, Phillips v Harbro Rubber Co (1918) 35 RPC 276 at 282-3 and other authorities referred to by Lockhart J in Conrol Pty Ltd v Meco McCallum Pty Ltd (1996) 34 IPR 517 at 527-530.

The Comparison

48 In order to comply with the requirement imposed by s 19(1) it is necessary for the Court to identify the similarities and the differences between the two designs.

The Registered Design

49 The Registered Design is for a ceiling fan hub that consists of what I will refer to as an upper and lower hub. The upper hub consists of a two piece stepped circular component. The upper piece (Element A) is cylindrical in shape. The lower piece (Element B) is a cone-like shape with a wide flat top that transitions into the upper piece and a slightly narrower flat base. The upper hub is configured so that the ceiling fan rod can pass through its vertical axis. The upper hub conveys the appearance of a slightly bulky circular piece with a wide flat upper surface that transitions approximately half-way along its vertical length from a cylindrical into a conical shape that narrows toward a flat base.

50 The lower hub appears to consist of what I would describe as a three piece stepped circular body with a lower portion that has a wide, flat cylindrical base (Element E) and an upper portion that is slightly cone shaped and that gradually narrows and transitions into a flat surface that forms the top of the lower hub (Element C). The surface of the lower portion (Element D) upon which the upper portion appears to sit is curved in shape, but the curve is very slight and appears to be substantially flat to the eye. In the Registered Design the lower hub strikes the eye as having a shape and configuration that is slender and light weight, with clean lines and elegant proportions. The upper hub of the Registered Design appears to be bulkier in appearance but is still well proportioned with the upper piece and the lower piece also exhibiting the same clean lines, and a stylish simplicity of appearance similar to what is seen in the lower hub.

The Razor

51 Looking at the upper hub of the Razor, it consists of three rather than two concentric pieces. Two of these are located beneath the uppermost piece, and both of these pieces are cylindrical rather than cone shaped.

52 The Razor has a lower hub that would appear to be very similar to the lower hub of the Registered Design were it not for the presence of the lower canopy. To my eye, the Razor’s lower hub, due to the presence of the lower canopy, does not exhibit the same degree of simplicity and elegance of appearance as the Registered Design. The presence of the lower canopy makes the Razor look slightly heavier and bulkier than the Registered Design at least when viewed from “side on” (as in sheets 6/9, 7/9 and 9/9).

53 The elevation of the surface separating the upper and lower pieces of the lower hub in the Registered Design (Element D) gradually increases towards the centre where it meets the uppermost piece of the lower hub. The corresponding surface on the Razor (Element K) does the same.

54 The shape of the cut-out apertures which are designed to receive the fan blades are different. The apertures in the Registered Design are curved whereas the apertures in the Razor are straight. In both cases they are located in the same position extending in a generally diagonal and downward direction from left to right.

The Prior Art

55 The state of development of the prior art base is apparent from the eight different prior art designs in relation to which the expert witnesses gave evidence. I will make some brief observations concerning each of those designs.

Prior Art Design A (Vortex)

56 This design creates a very different visual impression to both the Registered Design and the Razor. The upper hub is in the shape of a hemisphere. Beneath it there is a lower hub that includes a prominent bell-shaped canopy. The appearance of the lower hub is tall and bulky rather than flat and sleek. One does not see the same clean lines and flat lower surface found in either the Registered Design or the Razor. They are visually very different to the Vortex.

Prior Art Design B (Rexel)

57 Most of what I have said about the Vortex applies to this design although the upper hub is in the shape of a bell rather than a hemisphere. The lower hub also includes a prominent bell-shaped canopy. Overall, this design lacks the sleekness and symmetry of the Registered Design’s and the Razor’s stepped concentric shapes.

Prior Art Design C (Futura)

58 The upper canopy of the Futura is bowl shaped and does not have the stepped concentric shapes that characterise the upper hub of the Registered Design and the Razor. The lower hub includes a canopy much like that seen in the Razor. However, the Futura does have the stepped concentric shapes beneath the lower canopy that one sees in the Razor, and it also appears to have a more rounded lower surface rather than the generally flat surface that one sees at the bottom of the lower hub in the Registered Design and the Razor.

Prior Art Design D (Concept 1)

59 This design has an upper hub that is generally bowl shaped, without the stepped appearance of the upper hub of the Registered Design. The lower hub of the Concept 1 includes a cone shaped canopy that transitions into a large, bulky motor cover. The depictions of the Concept 1 in evidence show it with a rounded lamp lens located at its underside but the promotional literature for the products suggests that it was also available with a flat lens. The shape of the upper and lower hubs is quite different to those of the Registered Design and the Razor.

Prior Art Design E (Concept 2)

60 There is a physical example of the Concept 2 in evidence. It has a conical shaped upper hub that does not have the stepped configuration of either the Registered Design or the Razor. At the top of the lower hub is a cone shaped canopy that connects to a slopping, bowl shaped upper motor cover that connects to a large and bulky lower motor cover. The lower hub of the Concept 2 resembles that of the Futura.

Prior Art Design F (Airfusion)

61 The Airfusion has a stepped upper hub made up of stepped cylindrical shapes that closely resemble the upper hub of the Razor. The lower hub of the Airfusion is tall and bulky in appearance. It does not have the sleekness of the Registered Design or the Razor.

Prior Art Design G (Sycamore)

62 The Sycamore is a very distinctive ceiling fan with a single hub that is generally bullet shaped in appearance. It has a highly distinctive appearance quite unlike all the other designs.

Prior Art Design H (Grenada)

63 The Grenada has an upper hub that is also conically shaped with at least one step. The lower hub appears to be large and bulky. The representation of the Grenada that is in evidence is of poor quality and it is difficult to see all of its features. It is sufficient to say that the lower hub lacks the sleekness of the stepped configuration of the Registered Design and the Razor.

Overall Assessment

64 As previously explained, it is necessary to focus on the overall impression created by the two designs. Precise mathematical comparisons or analyses of measurements or ratios have no role to play in determining whether or not the two designs create an overall impression that is substantially similar. In this regard, I did not find evidence of that nature from Mr Hunter of any real assistance. The overall impression created by a design arises from looking at a registered design or a product made to a particular design rather than measuring it.

65 I am mindful that I must give more weight to the similarities between the designs rather than the differences between them.

66 As to the upper hubs, both designs utilise concentric shapes. The circumference of each of the uppermost cylindrical shapes is generally, but not precisely, located on the same vertical axis as the upper motor cover of each design. In both cases the upper motor cover tapers slightly inwards in the upward direction at what appears to be close to the same angle.

67 As to the lower hubs, the upper and lower motor covers in the Registered Design (Elements A, B) and in the Razor (Elements J, L) are similarly proportioned and have a generally sleek and flat appearance. I attach particular importance to these similarities because it is the lower hub to which the eye is likely to be drawn when an apparatus made to the design is installed in a ceiling as part of a complete ceiling fan and it is the base of the lower hub that will contribute most to the overall appearance of what will present as a sleek and elegantly configured apparatus. In my view this is a relevant consideration given the terms of s 19(2)(c) of the Act.

68 The lower canopy in the Razor is a significant point of difference between it and the Registered Design. Another significant point of difference is the configuration of the upper hub of the Razor which consists of one cylindrical shape with a relatively wide diameter (Element F) and two other cylindrical shapes immediately below it (Elements G, H), that are of a much smaller diameter. The third such shape (Element H) is very small and makes only a slight contribution to the overall visual impression conveyed by the Razor.

69 The two main differences between the designs reside in the absence of any lower canopy in the Registered Design and the differently configured upper hub. Other differences between the Razor and the Registered Design to which I have previously referred, and upon which much of Mr Hunter’s evidence focused, make little contribution to overall visual impression created by the two designs. I refer here, in particular, to the shape of the cut-out apertures, the differences in the degree to which the upper surface of the lower motor covers (Elements D, K) slope, and the flatness of the bottom surface of the lower motor covers (Elements E, L). In my view, the informed user would perceive these differences as minor, and as not having any significant impact on the overall visual impression conveyed by each of the two designs.

70 I have had regard to the matter of freedom to innovate. The variety of designs that form part of the prior art base show that a designer of a ceiling fan hub has freedom to innovate. The configurations of both the Razor and the Registered Design are to a considerable extent dictated by the function they are designed to perform but, as the prior art shows, there are still many different ways in which a ceiling fan hub can be configured ranging from a relatively conventional design (eg. Rexel) to something much more distinctive (eg. Sycamore). Neither expert suggested that there was any significant restriction on the freedom of a designer of ceiling fan hubs to create new and innovative designs.

Conclusion

71 In my opinion the Razor is substantially similar in overall impression to the Registered Design. Although they exhibit a number of obvious differences in shape and configuration, these differences are in my view insufficient to displace what I consider to be significant and eye-catching similarities that create an overall impression of substantial similarity.

72 The applicant is entitled to declaratory and injunctive relief and will be directed to file and serve a draft minute of the orders it seeks. The applicant will also be directed to notify the respondent whether it proposes to pursue its claim for pecuniary relief. The proceeding will stand over to a date to be fixed for the purpose of making further orders.

73 Orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding seventy-three (73) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Nicholas. |

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3