FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Derodi Pty Ltd

[2016] FCA 365

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | DERODI PTY LTD ACN 003 413 063 First Respondent HOLLAND FARMS PTY LTD ACN 002 019 427 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

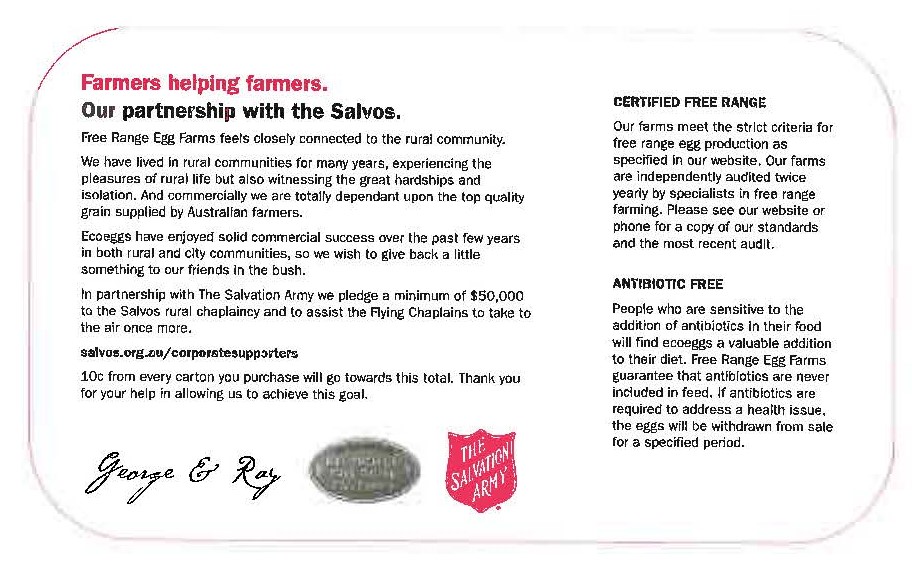

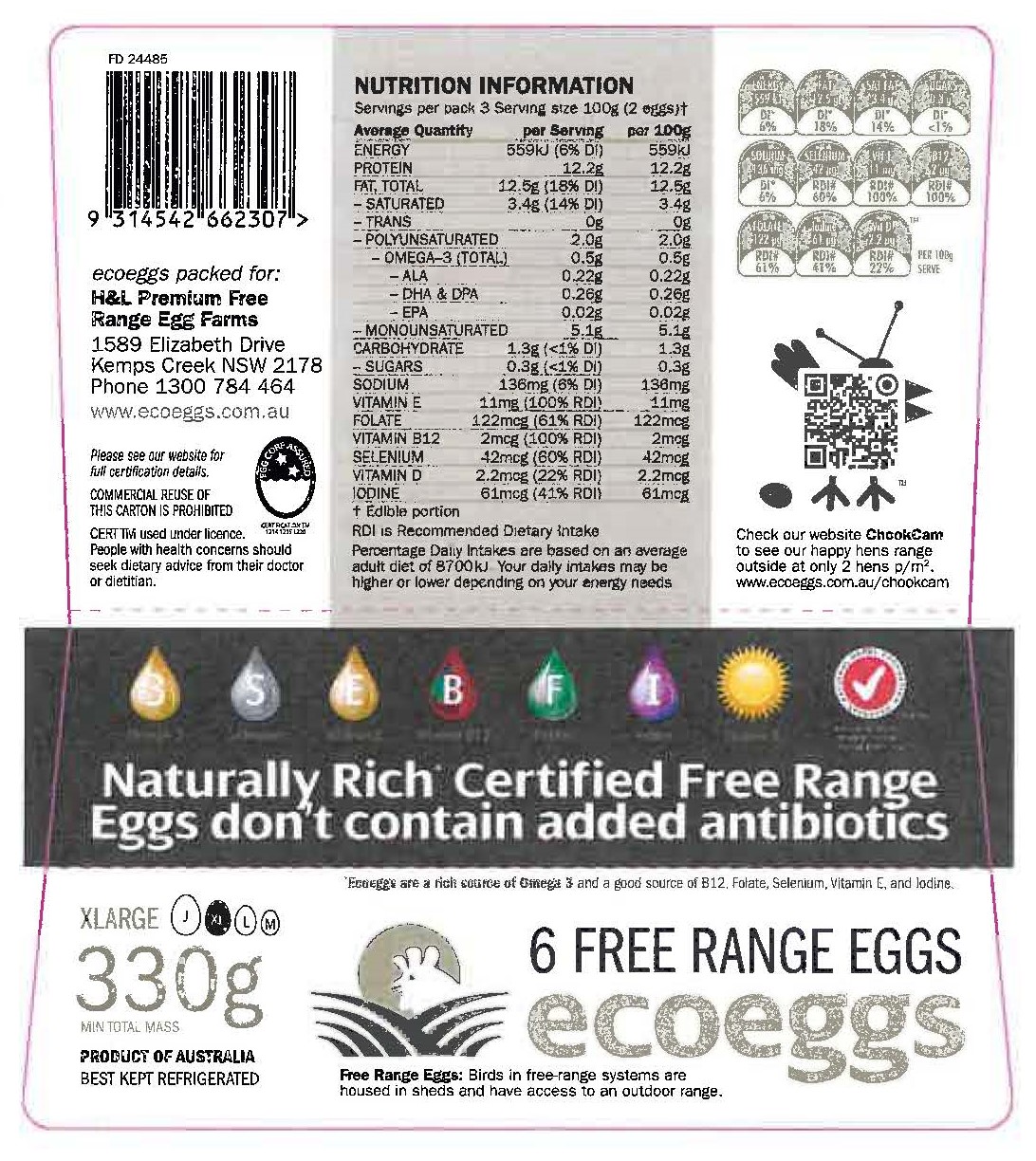

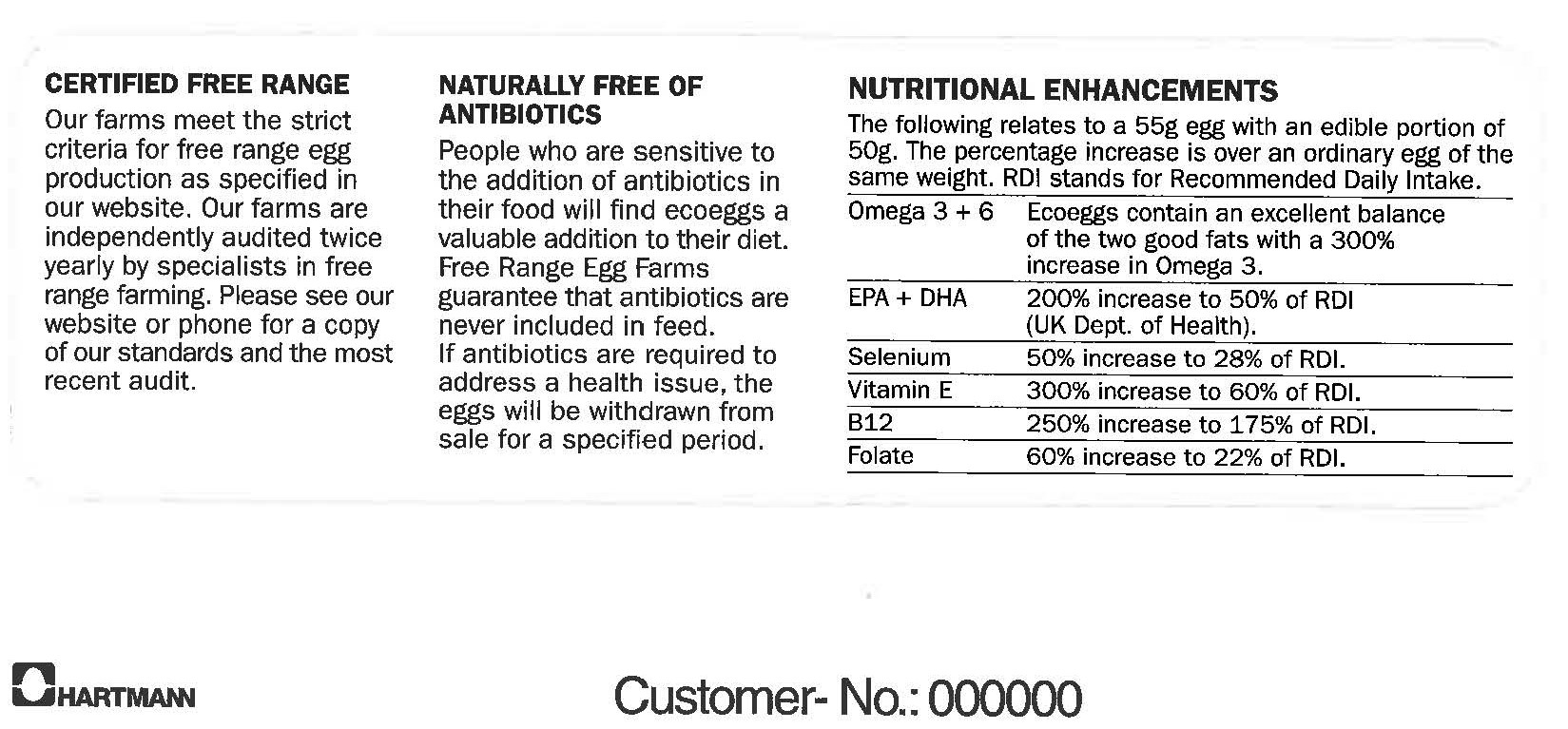

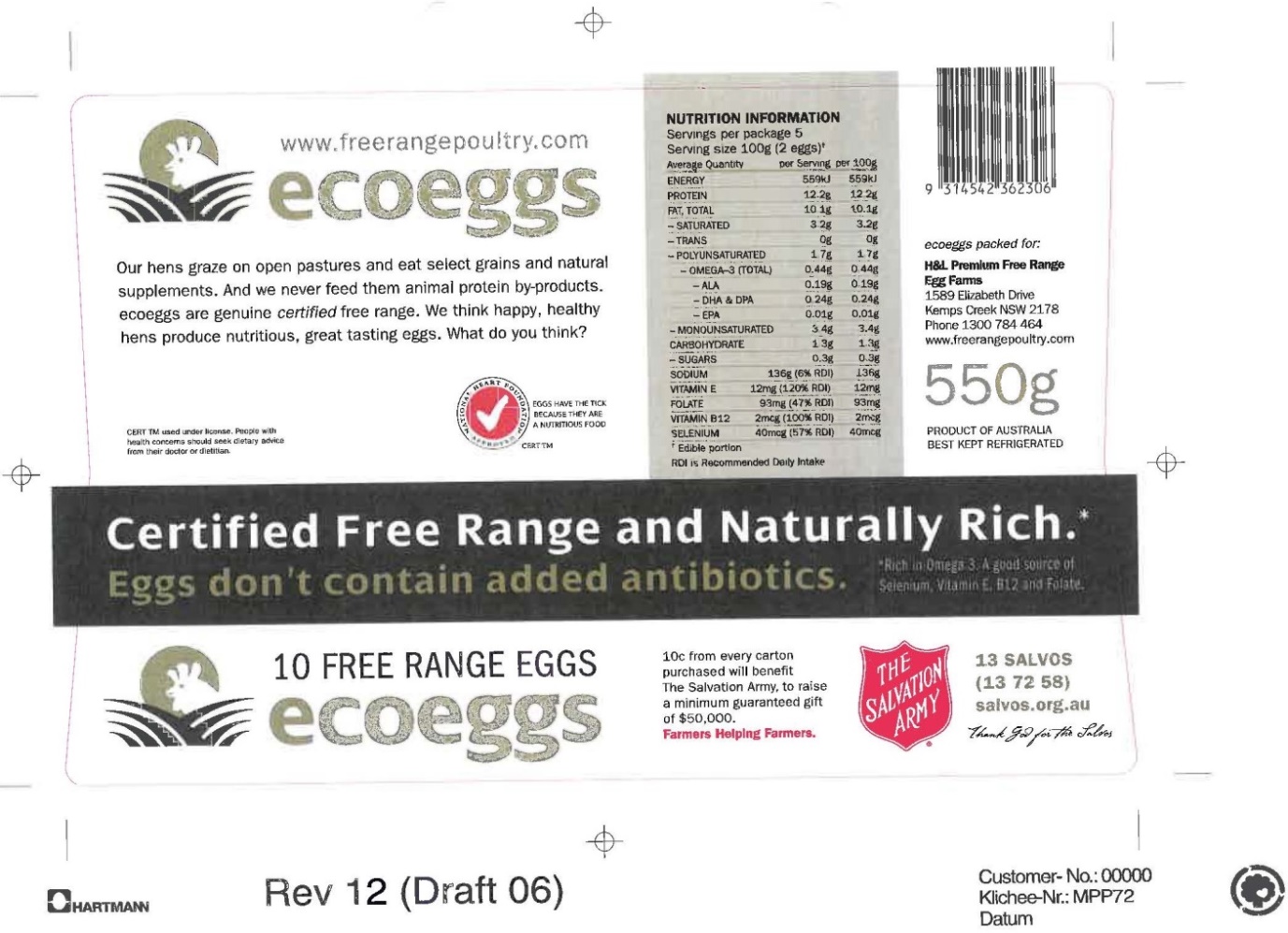

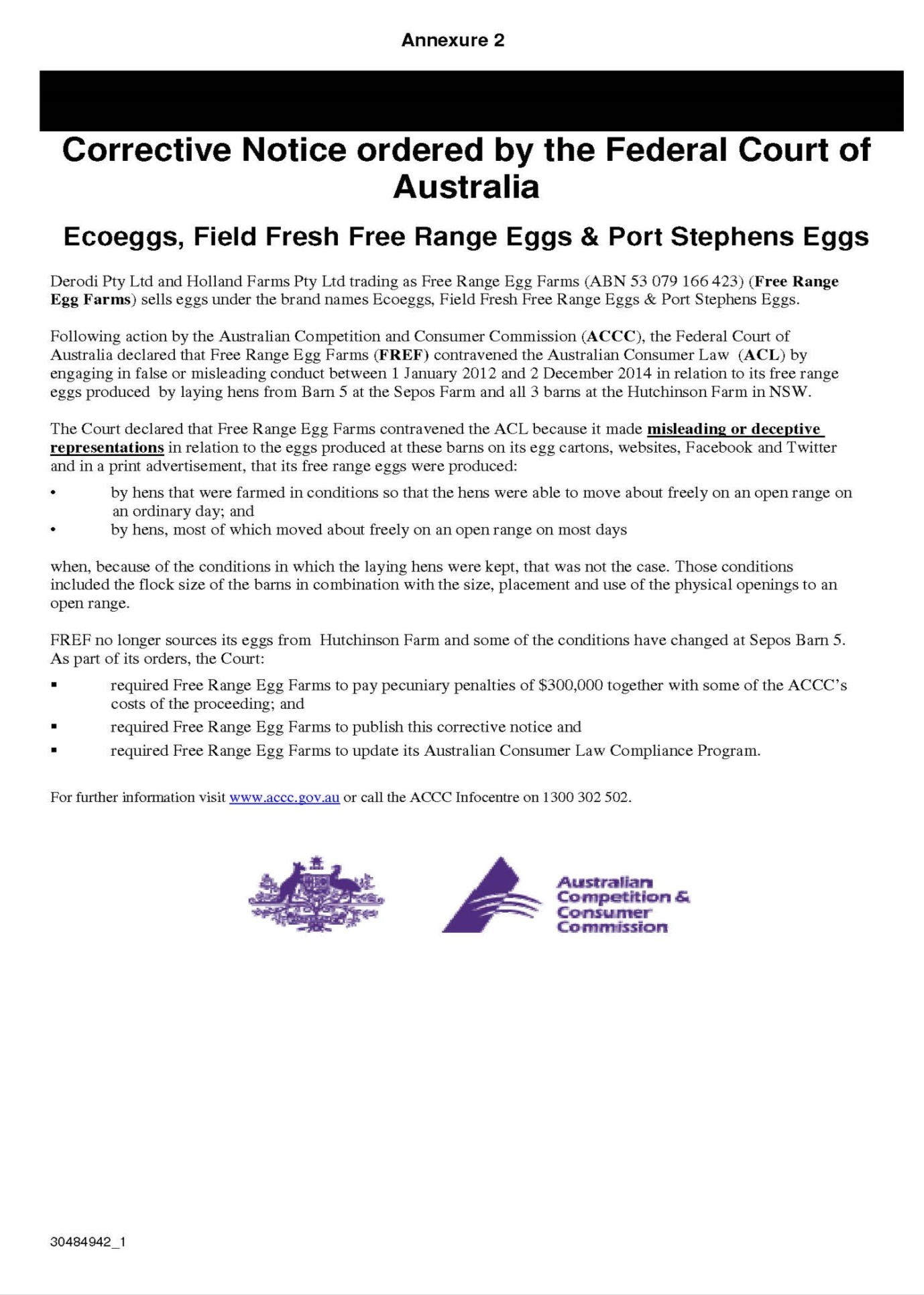

(a) by supplying for sale or causing to be supplied for sale eggs produced by laying hens from Barn 5 on the property in New South Wales known as the Sepos Farm and all three barns on the Hutchinson Farm and packaged in the forms of those cartons depicted in Annexure 1 to these orders, from 1 January 2012 to 2 December 2014 (Free Range Egg Cartons); and

(b) by advertising and promoting the eggs sold in the Free Range Egg Cartons by publishing the websites www.ecoeggs.com.au, www.fieldfresheggs.com.au, www.portstephenseggs.com.au on Facebook, Twitter and in an issue of Prevention Magazine:

in each instance represented to consumers that the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced:

(c) by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day (where an “ordinary day” is every day other than a day when on the open ranges weather conditions endangered the safety or health of the laying hens or predators were present or the laying hens were being medicated); and

(d) by laying hens most of which moved about freely on an open range on most days,

when, in fact, eggs from Barn 5 at the Sepos Farm and all of the barns at the Hutchinson Farm contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons during the period 1 January 2012 to 2 December 2014 were produced by laying hens most of which were not able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day and did not move about freely on an open range on most days, and the respondents thereby in trade or commerce:

(e) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010);

(f) in connection with the supply or possible supply of eggs, and the promotion of the supply of the eggs, made misleading representations that the eggs were of a particular quality, or have had a particular history, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law; and

(g) engaged in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of the eggs, in contravention of s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary penalty

2. The respondents pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $300,000 pursuant to s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law. That pecuniary penalty is to be paid in equal monthly instalments over a period of 12 months commencing 1 month from the date of this order.

Publication orders

3. The respondents, at their own expense within 21 days of the date of this order, publish a corrective advertisement, in the form of Annexure 2 to these orders, in the Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and the Daily Telegraph, and further, ensure that each advertisement shall:

(a) occupy 20cm by 26cm of the page;

(b) be in a text which is Arial font and which is:

(i) for the headline, no less than 18-point and bolded; and

(ii) for the remaining text, not less than 12-point; and

(c) be placed within the first 10 pages of each of the newspapers.

Compliance order

4. The respondents, at their own expense in relation to the business known as Free Range Egg Farms:

(a) within 3 months of the date of this order, establish an Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program which meets the requirements set out in Annexure 3 to these orders; and

(b) maintain and administer the Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program for a period of 3 years from the date on which it was established.

Costs

5. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding fixed in the sum of $35,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[7] | |

[7] | |

The farm conditions at Barn 5 of Sepos Farm from 2012 to 2014 | [13] |

The farm conditions at the Hutchinson Farm from 2012 to 2014 | [17] |

[23] | |

[26] | |

[29] | |

[30] | |

[32] | |

[34] | |

[36] | |

[40] | |

[41] | |

[42] | |

[49] | |

[49] | |

[50] | |

[53] | |

[59] | |

[61] | |

[64] | |

[65] | |

[66] | |

[68] | |

[70] | |

The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended | [72] |

[75] | |

[79] | |

1 Derodi Pty Ltd (Derodi) and Holland Farms Pty Ltd (Holland) trade in partnership as Free Range Egg Farms. That partnership can be conveniently described as FREF. Later in these reasons I deal with the significance for penalty of this joint treatment.

2 FREF’s business includes purchasing chicken eggs from farmers and supplying those eggs to retailers. This proceeding is concerned only with circumstances of the production and marketing of FREF’s eggs over nearly three years from 1 January 2012 until 2 December 2014, from two farms in New South Wales: the Hutchinson Farm at Booral and the Sepos Farm in Allworth.

3 FREF marketed their eggs from the Hutchinson Farm and the Sepos Farm as “free range”. That description is well known to consumers. Its meaning includes the notion that the eggs are neither laid by hens confined to barns nor by hens housed in cages. Many consumers are prepared to pay a substantial premium for free range eggs.

4 The free range labelling of FREF’s eggs was prominent, as can be seen in the Annexures to these reasons. A discerning consumer might have conducted an internet search and visited the websites based upon the brand label on the carton. One such website featured an image of a chicken against a background of sky and field, overlayed with the words, “taste freedom” and descriptions such as “the video shows our happy hens coming out in the morning, dust bathing, running around” and “thanks to our live ChookCam you can clearly see the hens enjoying their outside time, digging, dust bathing and running around”. The website for the brand Ecoeggs also contained statements including that “ecoeggs are genuine certified free range eggs” and “are you really buying ecoeggs free range? Each ecoegg is stamped for authenticity which gives you the confidence that you are buying our certified free range eggs”. There were statements including that “all our ecoeggs farms provide ... an average maximum of 2 hens [per square metre] outside range area during the day”.

5 The representations made by FREF were misleading. The Hutchinson Farm barns and the relevant barn at the Sepos Farm had between 8 and 11 hens per square metre. The hens were not given access to the outdoor ranges until they were 26 to 32 weeks old. Even then, access was limited in various ways. As FREF admits, its representations contravened ss 18, 29(1)(a) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law.

6 Since the commencement of this proceeding FREF has continued to sell eggs labelled as “free range” branded with labels including ‘ecoeggs’, ‘Port Stephens Free Range’, and ‘Field Fresh Free Range Eggs’. But substantial changes have been made. FREF continued to acquire eggs from Sepos Farm once the operation was altered to ensure that the hens are free range. FREF has implemented a substantial compliance program. FREF also significantly cooperated with the ACCC in relation to these proceedings, including agreeing to all proposed remedies. Ultimately, although the penalty proposed by both parties to this proceeding may be on the low side, I am satisfied that it is an appropriate penalty based upon the material before the Court. These are my reasons for reaching that conclusion and the conclusion that the other orders for declarations, publication orders, compliance orders, and costs are appropriate.

The circumstances of the misleading free range claims

7 Between 2012 and October 2014, Derodi and Holland both had single directors. Those directors were Mr Leach of Derodi and Mr Holland of Holland. They were responsible for the running of each company including the marketing and promotion of the eggs that they purchased.

8 In early 2012, FREF (the partnership of Derodi and Holland) employed Mr Scott as a Farming Manager. Mr Scott’s roles included managing FREF’s relationships with its contract farms and ensuring that FREF’s contract farms were performing adequately.

9 FREF purchased eggs from four farms in New South Wales including the Hutchinson Farm and the Sepos Farm. These farms were audited by the Australian Egg Corporation Limited (AECL) under the Egg Corp Assured (ECA) quality assurance program. The AECL allowed the producers of eggs that were audited, including the four farms, to use an ECA Certification Trade Mark. But the ECA program did not deal with whether eggs were free range.

10 At the relevant time from 2012 until 2014, the Hutchinson Farm and Barn 5 of Sepos Farm produced a very large number of eggs. The eggs purchased by FREF from those sources amounted to 2.36% of the Australian free range egg market. Although FREF purchased eggs from four farms, the three barns from Hutchinson Farm and Barn 5 from Sepos Farm were a substantial source of FREF’s eggs which were marketed as free range (respectively 25% and 8%).

11 FREF’s contractual arrangements with the companies associated with the Hutchinson Farm and the Sepos Farm involved (i) FREF owning the chickens (and almost all the eggs produced by those chickens) at each farm, (ii) FREF providing advice to each farm on planning and poultry husbandry, and (iii) the companies associated with Sepos Farm and Mr Hutchinson (for Hutchinson Farm) being paid a fee for their services.

12 FREF marketed the eggs that it obtained from the Hutchinson Farm and Barn 5 of Sepos Farm as “free range”.

The farm conditions at Barn 5 of Sepos Farm from 2012 to 2014

13 From 1 January 2012 to 2 December 2014, Barn 5 at Sepos Farm housed approximately between 16,207 and 18,629 laying hens. The barn was 138.6 metres by 12.2 metres and had an internal stocking density of between 9.58 and 11.02 laying hens per square metre (95,848 to 110,172 laying hens per hectare). Its floor area was 1690.9 square metres.

14 Barn 5 had four pop holes on one side which were 3.8 metres wide by 54 centimetres high. These were 90 centimetres from the ground and were accessed by ramps and slats. They were open between 12.30pm and 9.00pm but were kept closed for around 125 days each year.

15 Barn 5 also had nesting boxes which were 1.04 metres wide with “walkover” gaps spaced intermittently along them, and a feeding system between the centre nest boxes and the external side walls of the barn.

16 From 1 January 2012 until June 2013, there was an open range adjacent to Barn 5 which was 2,429 square metres. In June 2013 this open range area was extended to 5,289 square metres. However, the hens’ access to this open range area was limited. The hens were not given access to the outdoor ranges until 90% of them had commenced laying eggs. This was generally when the hens were 26 to 32 weeks old. When access was given, the hens were rotated so that on most days they only received access to approximately half of the outdoor range. Electric fencing was used at particular times to prevent the hens from entering parts of the range.

The farm conditions at the Hutchinson Farm from 2012 to 2014

17 From at least 1 January 2012 to 2 December 2014, the Hutchinson Farm had three barns with the following approximate dimensions and content.

18 Barn 1 housed between 13,597 and 16,385 laying hens. It was 121 metres by 12 metres. It had between 9 and 11 laying hens per square metre (91,578 to 110,356 laying hens per hectare).

19 Barn 2 housed between 14,827 and 16,821 laying hens. It was 126 metres by 12 metres. It had between 9 and 11 laying hens per square metre (96,149 to 109,080 laying hens per hectare).

20 Barn 3 housed between 12,910 and 15,651 laying hens. It was 126 metres by 12 metres. It had between 8 and 10 laying hens per square metre (83,454 to 101,173 laying hens per hectare).

21 Barn 1 had four smaller pop holes (3.6 metres wide by 38 centimetres high) and Barns 2 and 3 had two slightly larger pop holes (7.2 metres wide by 35 to 55 centimetres high). The pop holes were between 60 and 106 centimetres off the ground, and were accessible by ramps with rubber conveyor belting. The rubber became hot during warmer temperatures and slippery during wet weather. The pop holes were open between the hours of 12:30pm and 9:00pm.

22 From 2012, there were open ranges adjacent to the barns on Hutchinson Farm. The open ranges adjacent to each barn were between 3,700 and 7,500 square metres. They did not have any outdoor structures that provided shade. Each new flock of hens was only given access to the outdoor range once 90% of the hens had commenced laying eggs, which would generally be when the hens were 26 to 32 weeks old.

23 The ACCC alleges, and FREF admits, that there were significant periods when the hens in the barns at Hutchinson Farm and Barn 5 of the Sepos farm were confined, or not ranging. Those periods included times when the pop holes were not opened.

24 In particular, in relation to the Hutchinson Farm, from 2012 until 2014 the hens in Barn 1 did not have access to any outdoor range until those hens were 59 weeks old and had been laying eggs for 38 weeks.

25 There were also other periods where hens were confined such as from 26 November 2012 until 24 July 2013. FREF’s explanation for the periods in which the hens did not have access to any outdoor range was on the basis of adverse weather conditions and work done for the formation of a dam next to Barn 1.

FREF’s supply and marketing of the eggs as “free range”

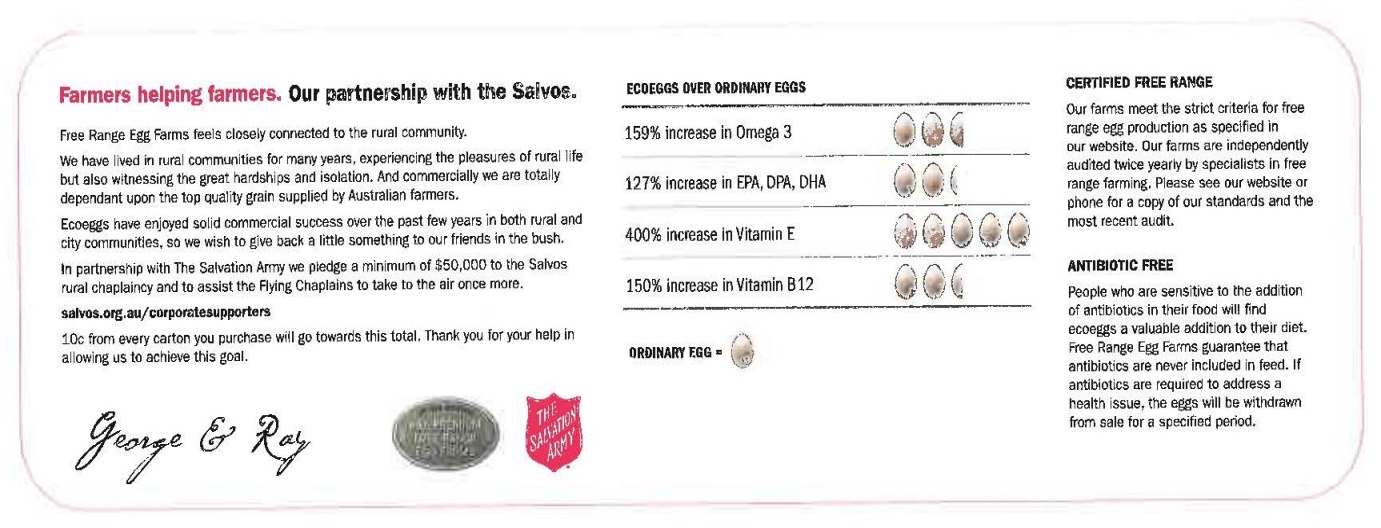

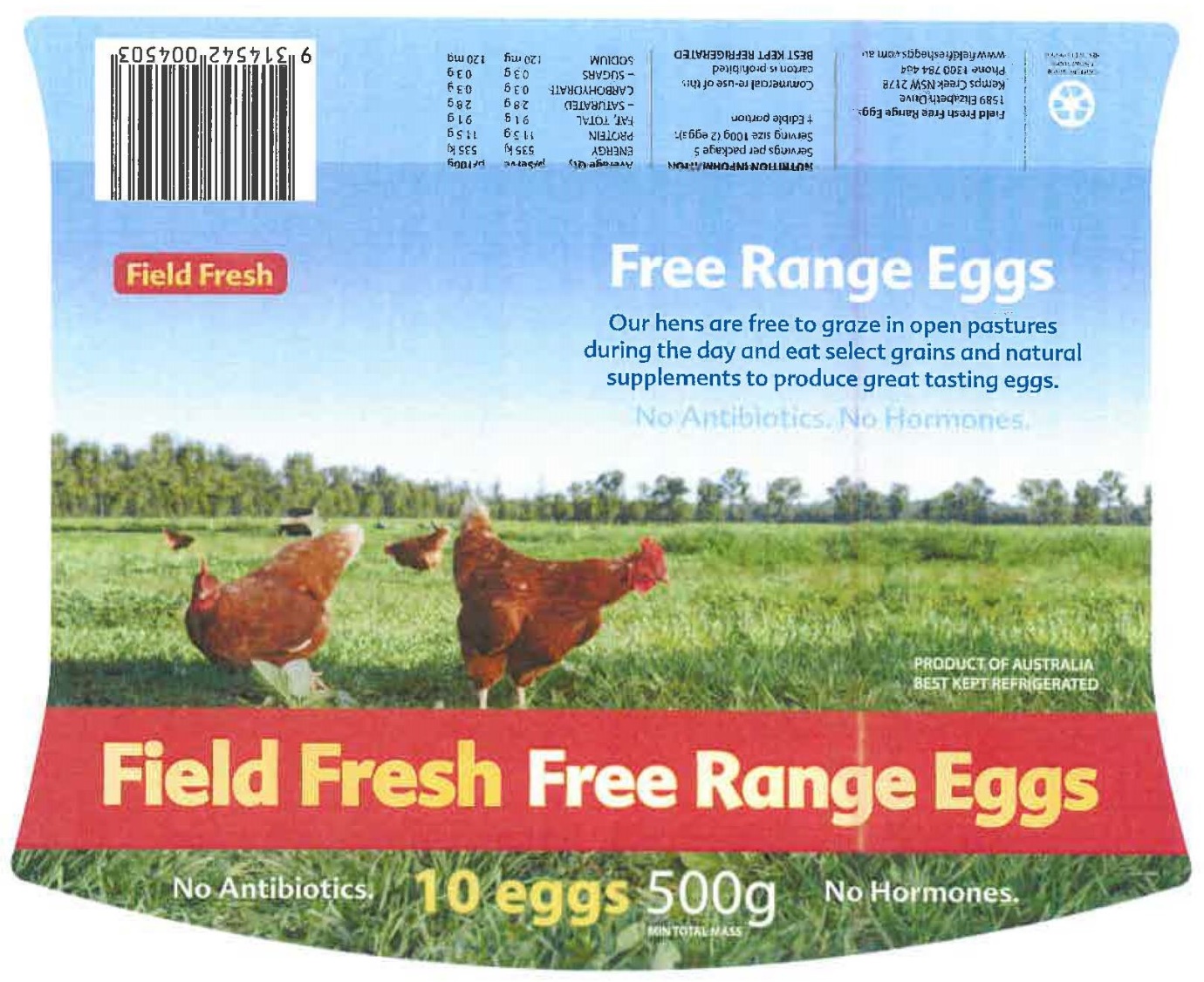

26 From 2012 until 2014, the eggs from the hens at Hutchinson and Sepos farms that I have described were packaged and sold by FREF as “free range”. FREF charged retailers a premium over the price that would have been charged if those same eggs were labelled as “cage” or “barn laid”. However, the full premium for eggs sold under the Ecoeggs brand was also attributable to the patented Omega 3 enriched feed given to hens which laid eggs marketed under the Ecoeggs brand.

27 FREF made representations that its eggs were free range in various ways. These were by representations published on:

(1) free range egg cartons;

(2) the Ecoeggs website;

(3) the Field Fresh website;

(4) the Port Stephens website;

(5) the Ecoeggs Facebook account;

(6) the Ecoeggs Twitter account; and

(7) the Ecoeggs print advertisement.

28 Each of these representations is considered below in turn.

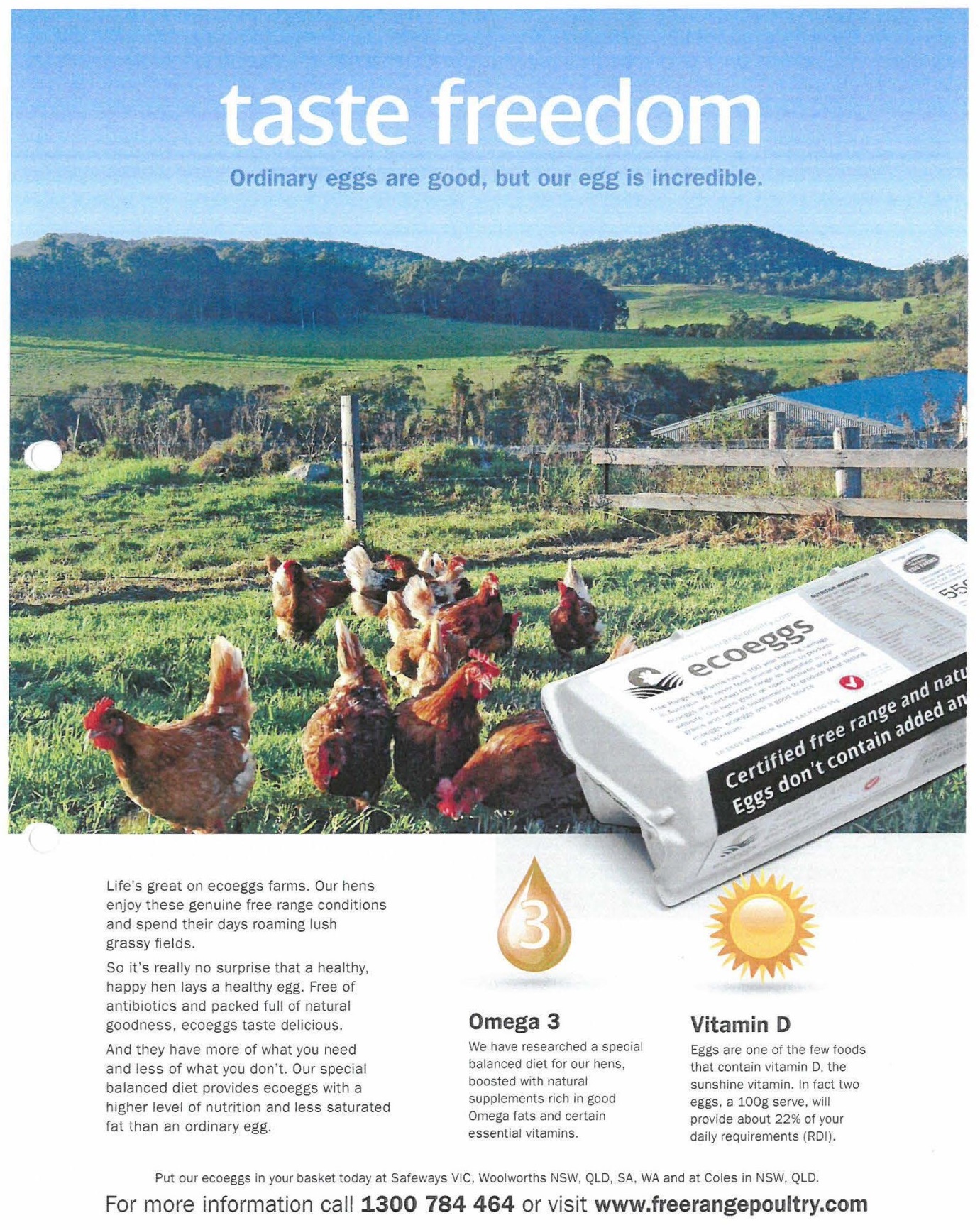

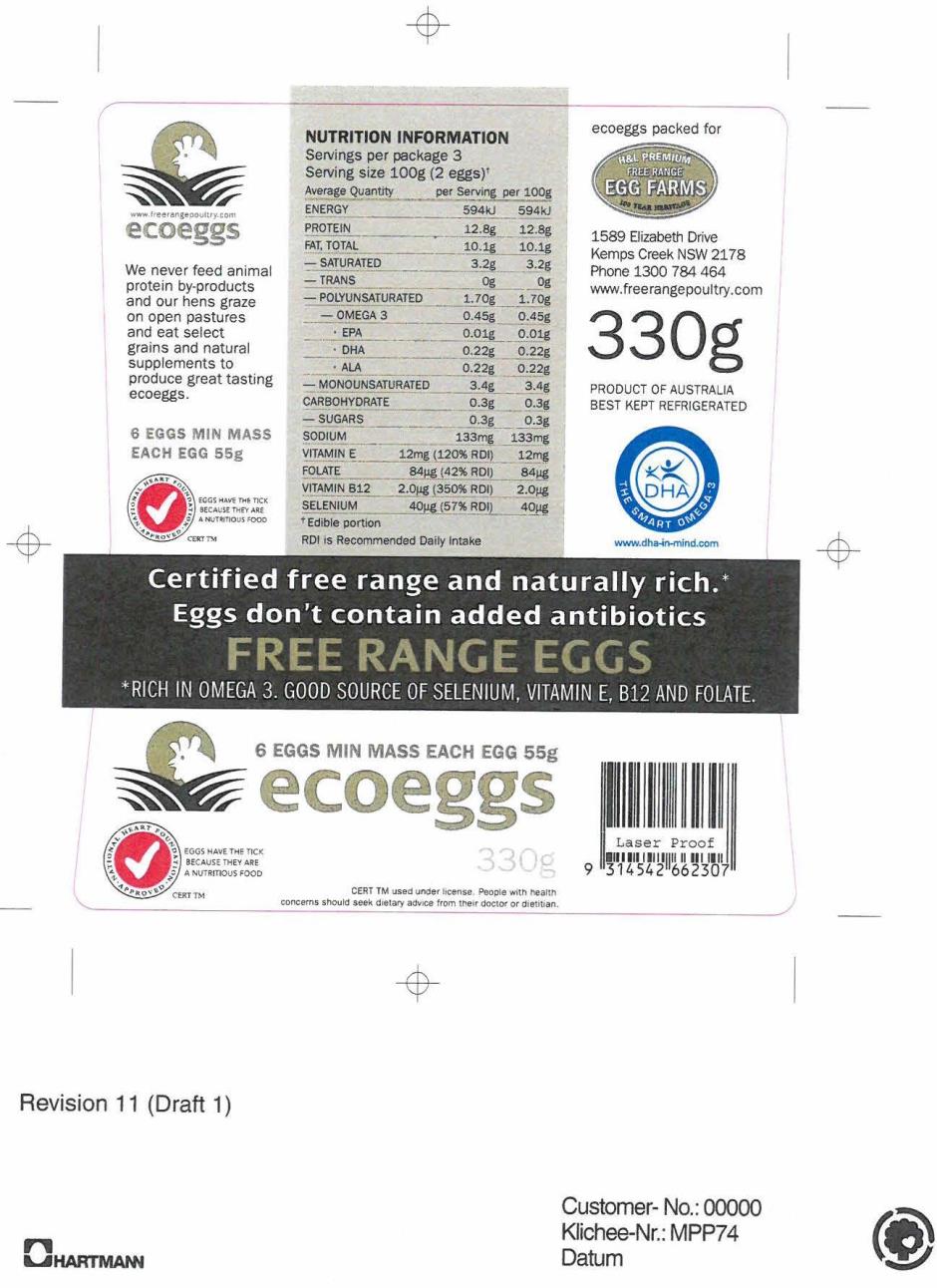

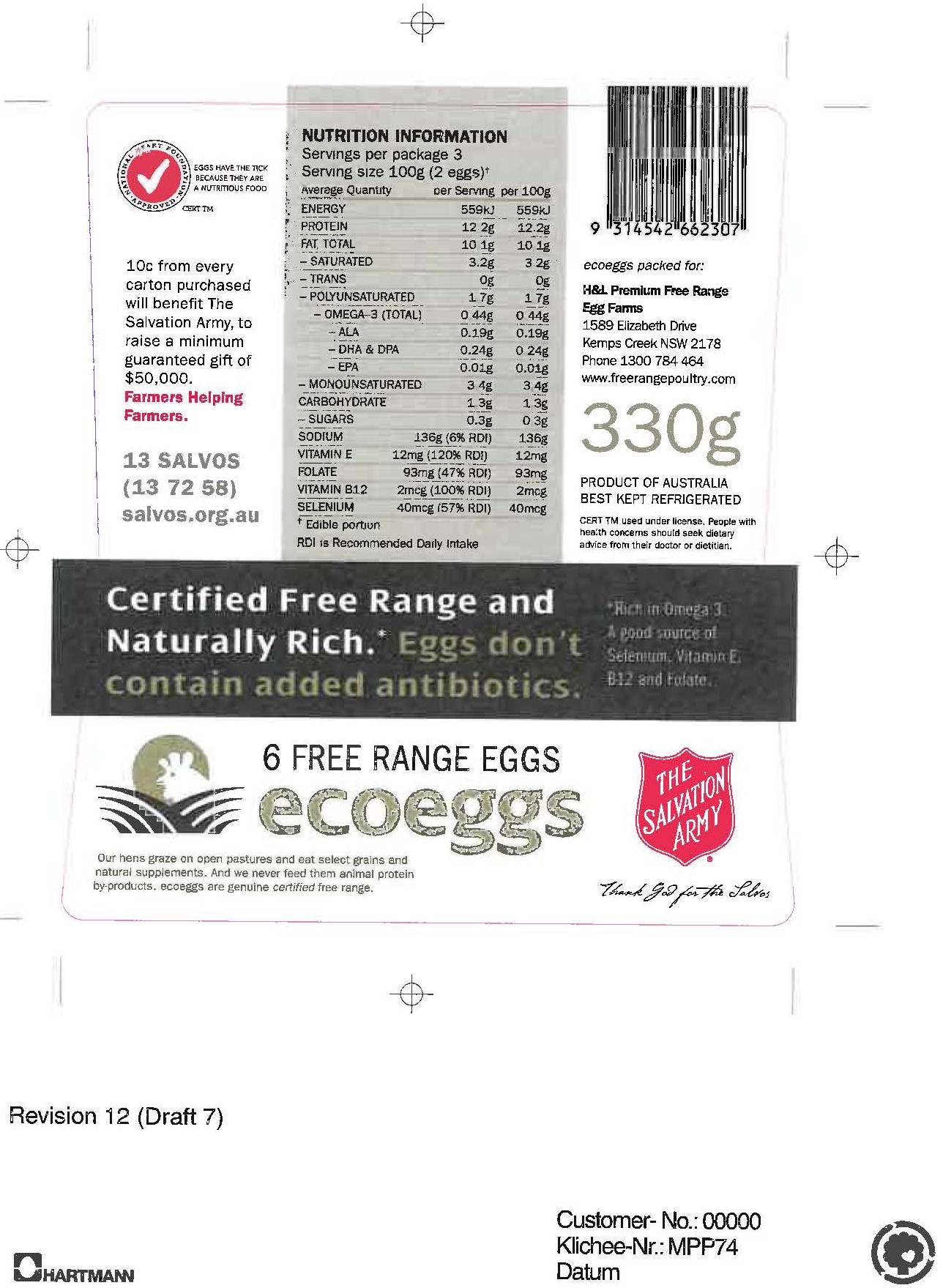

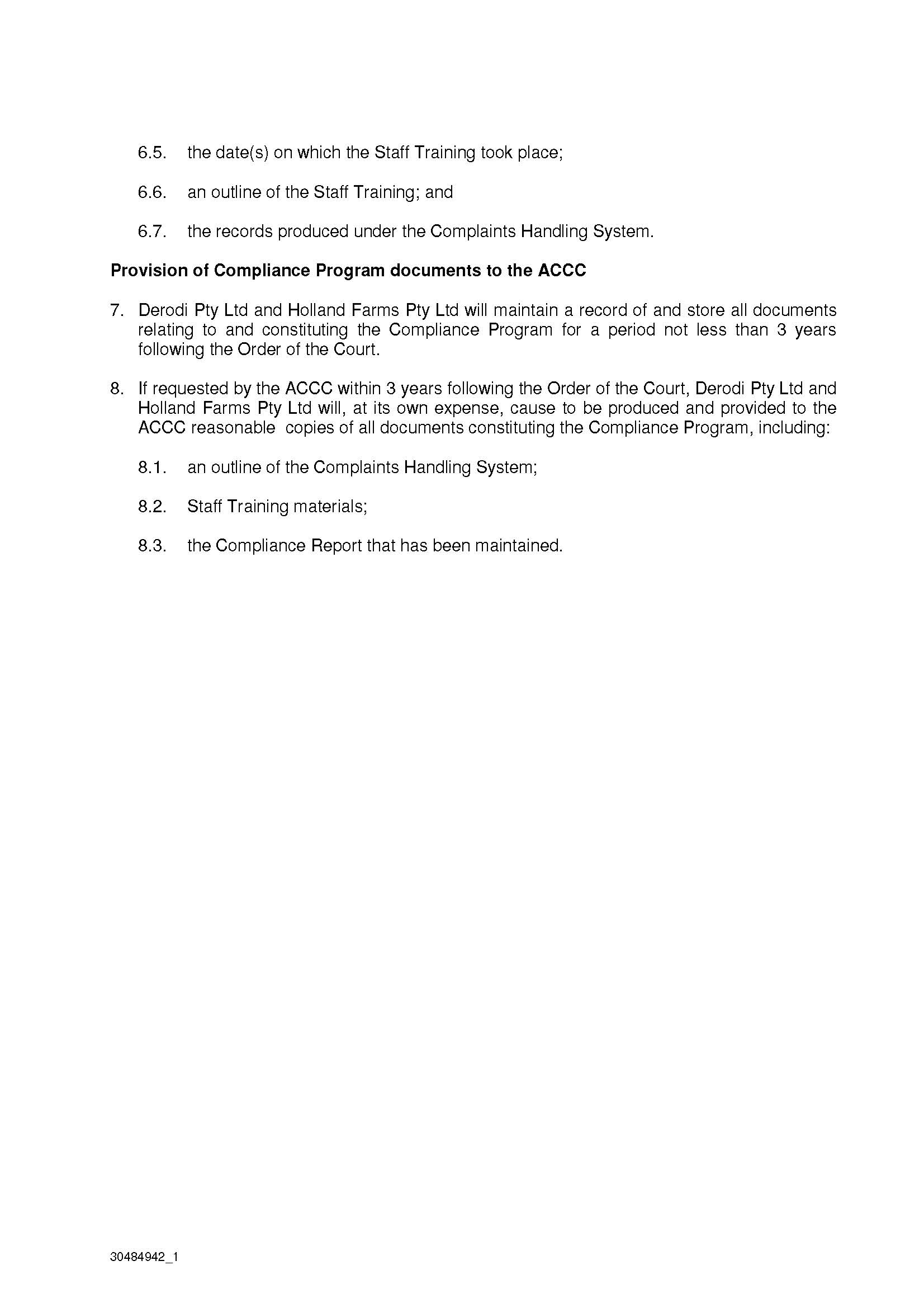

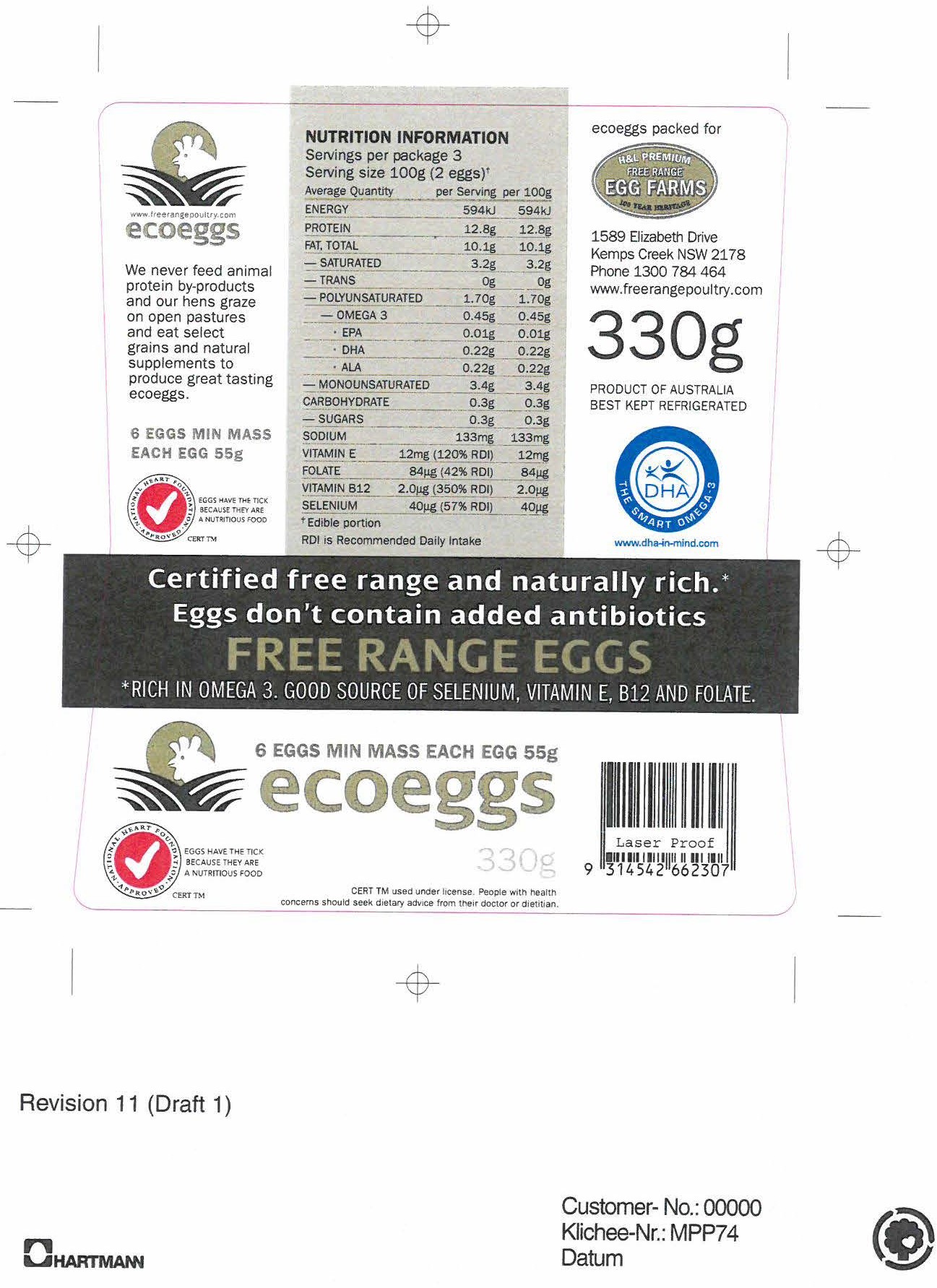

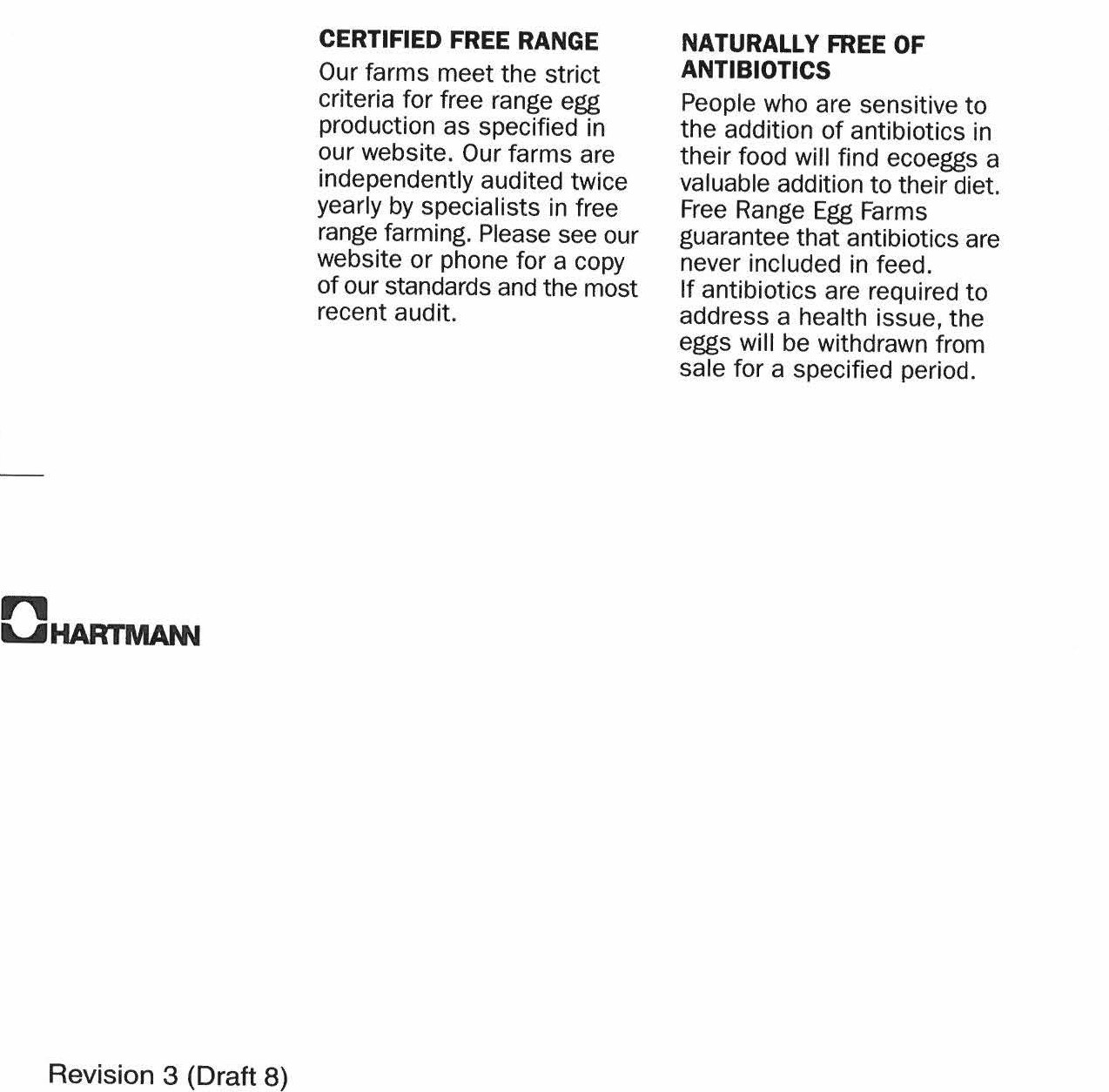

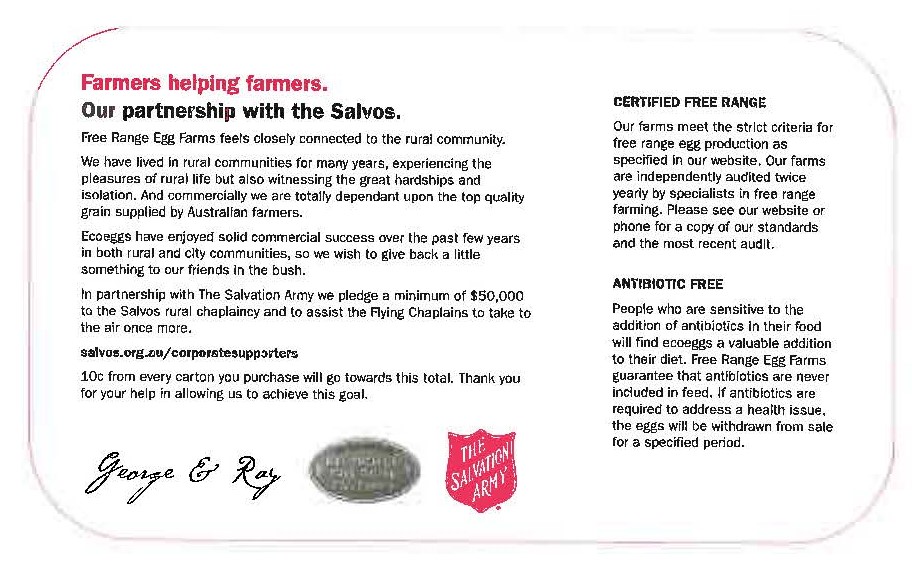

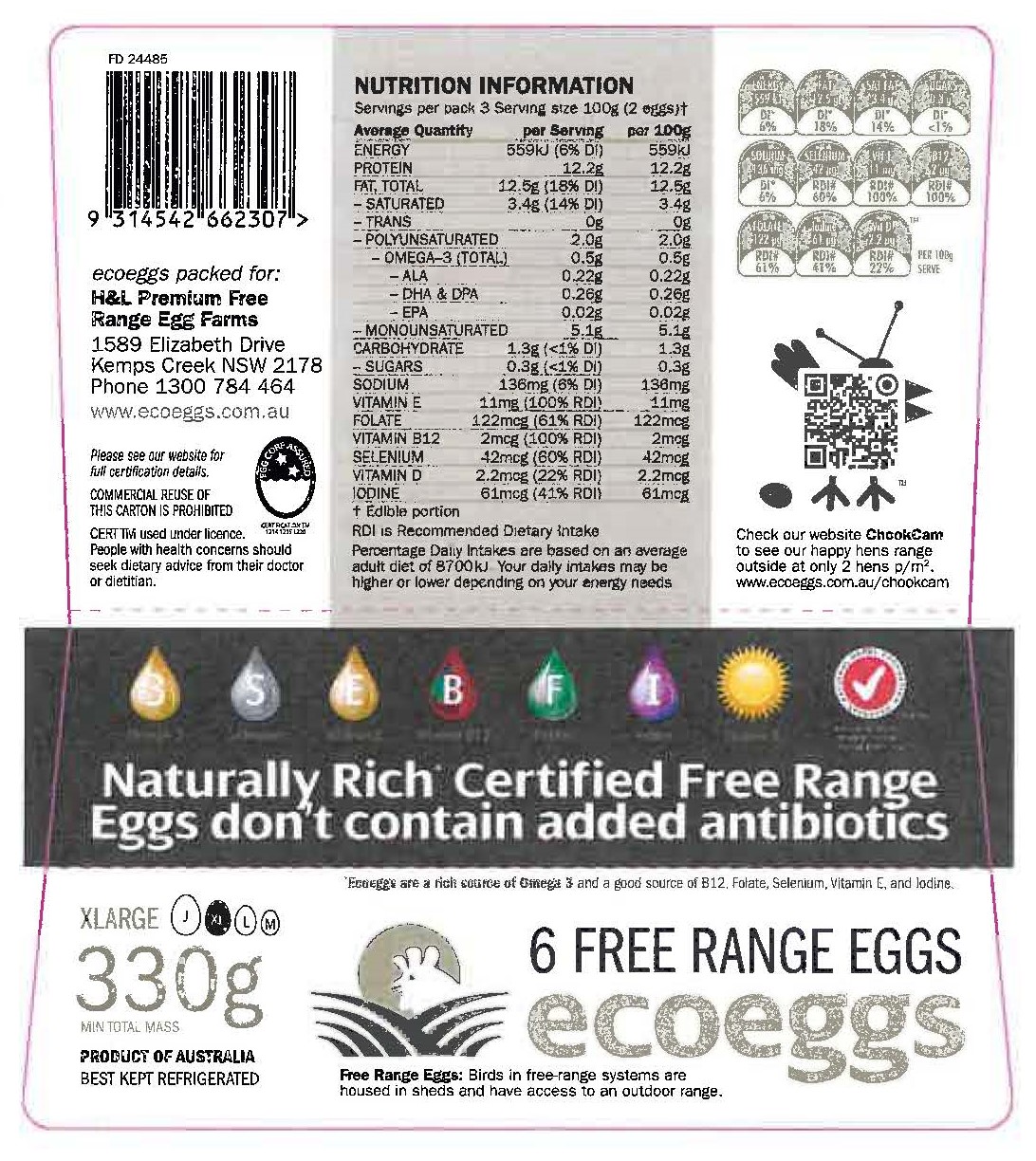

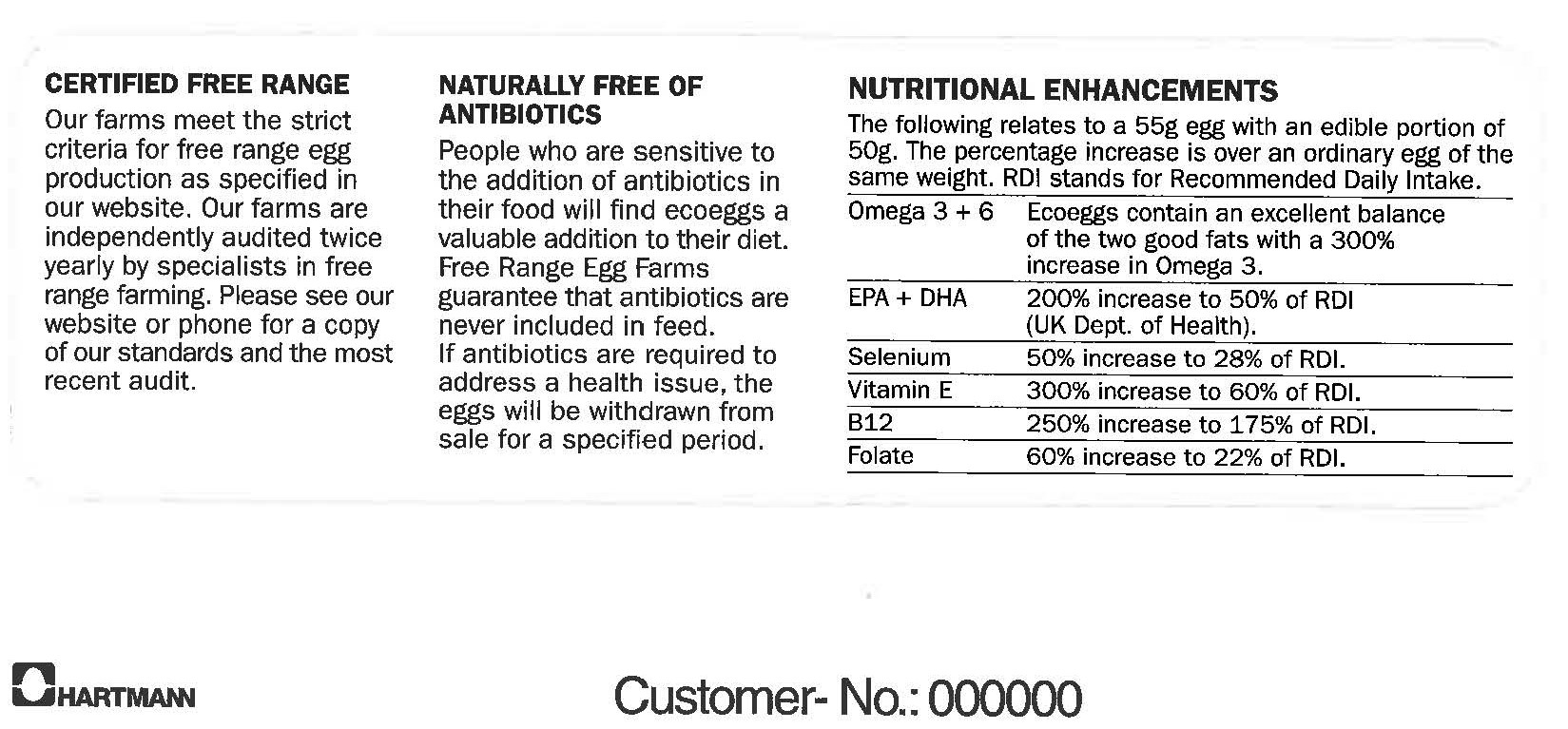

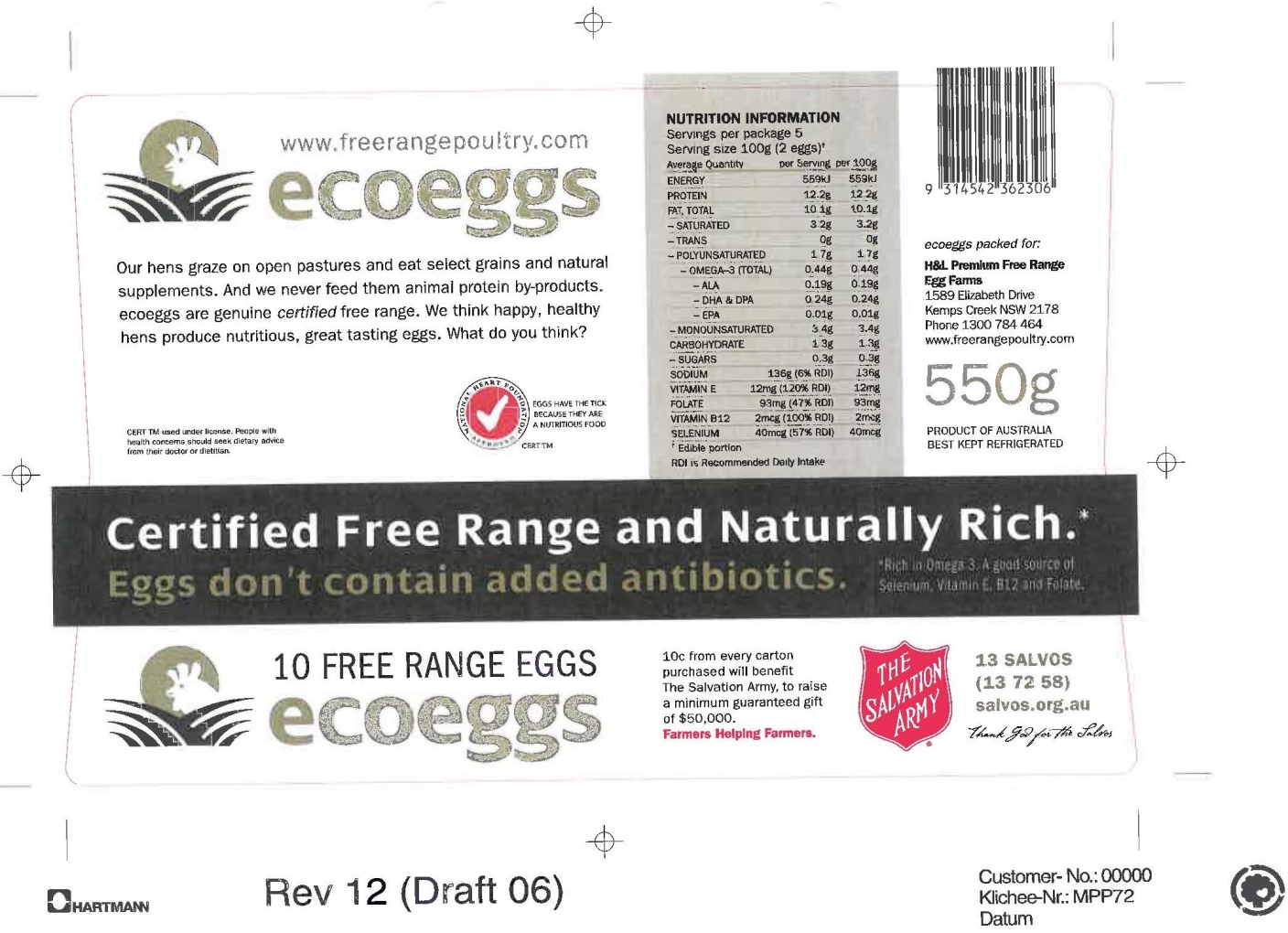

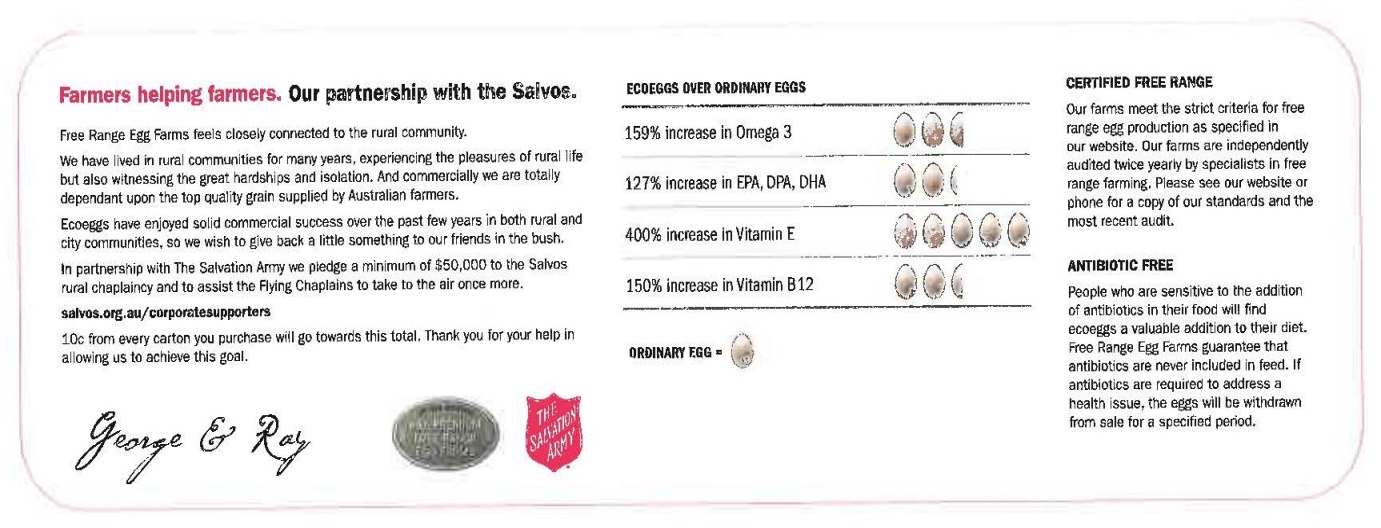

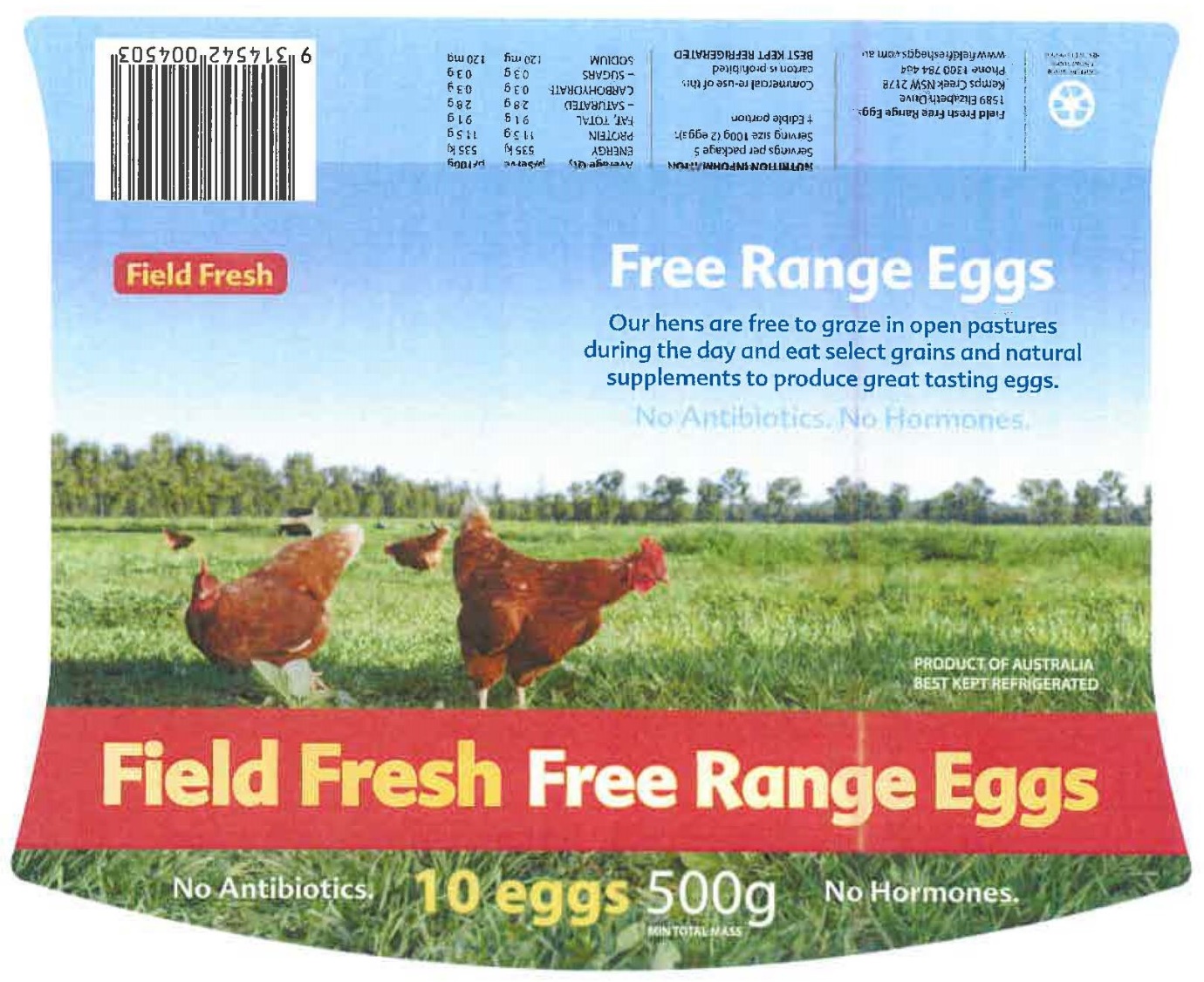

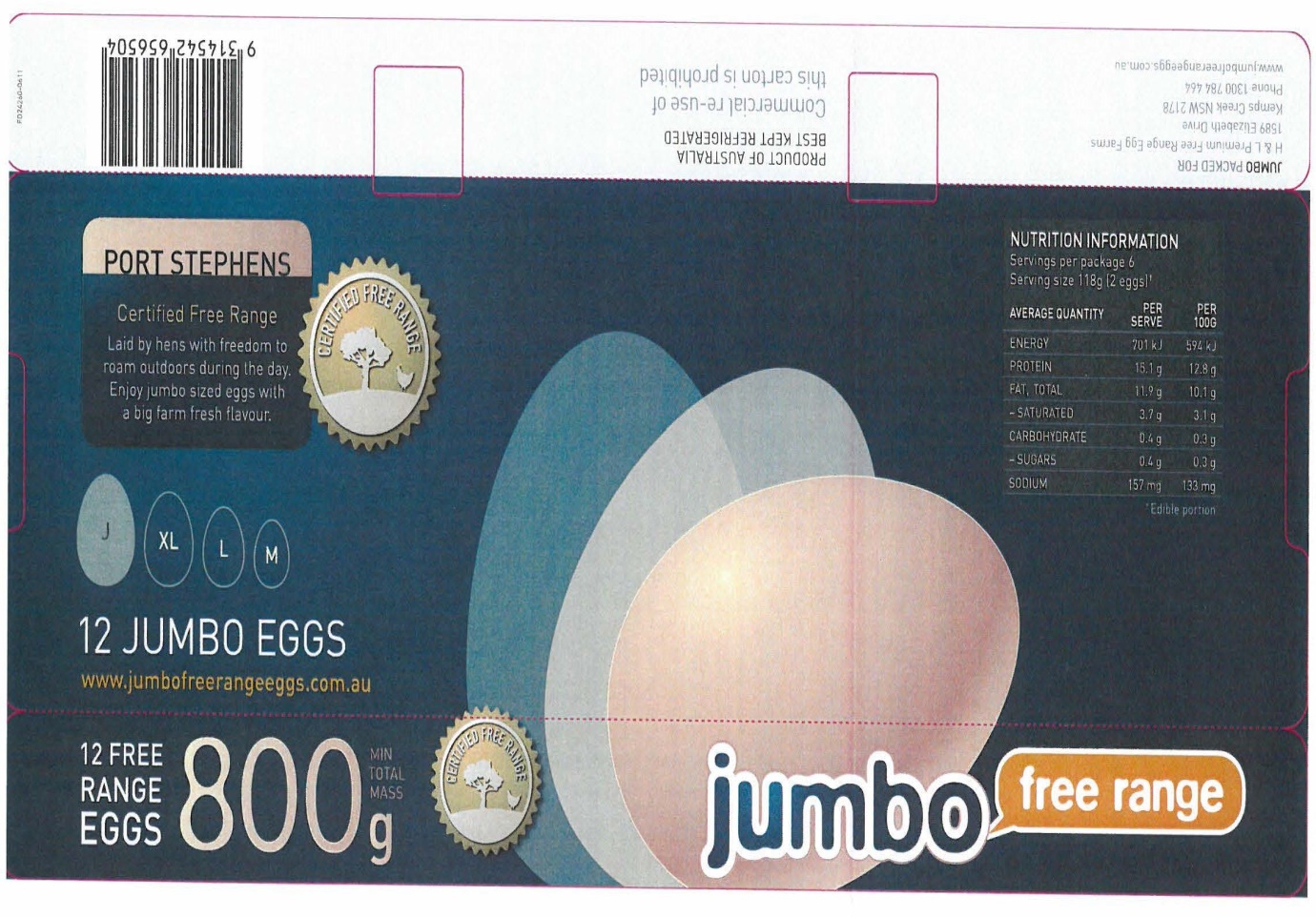

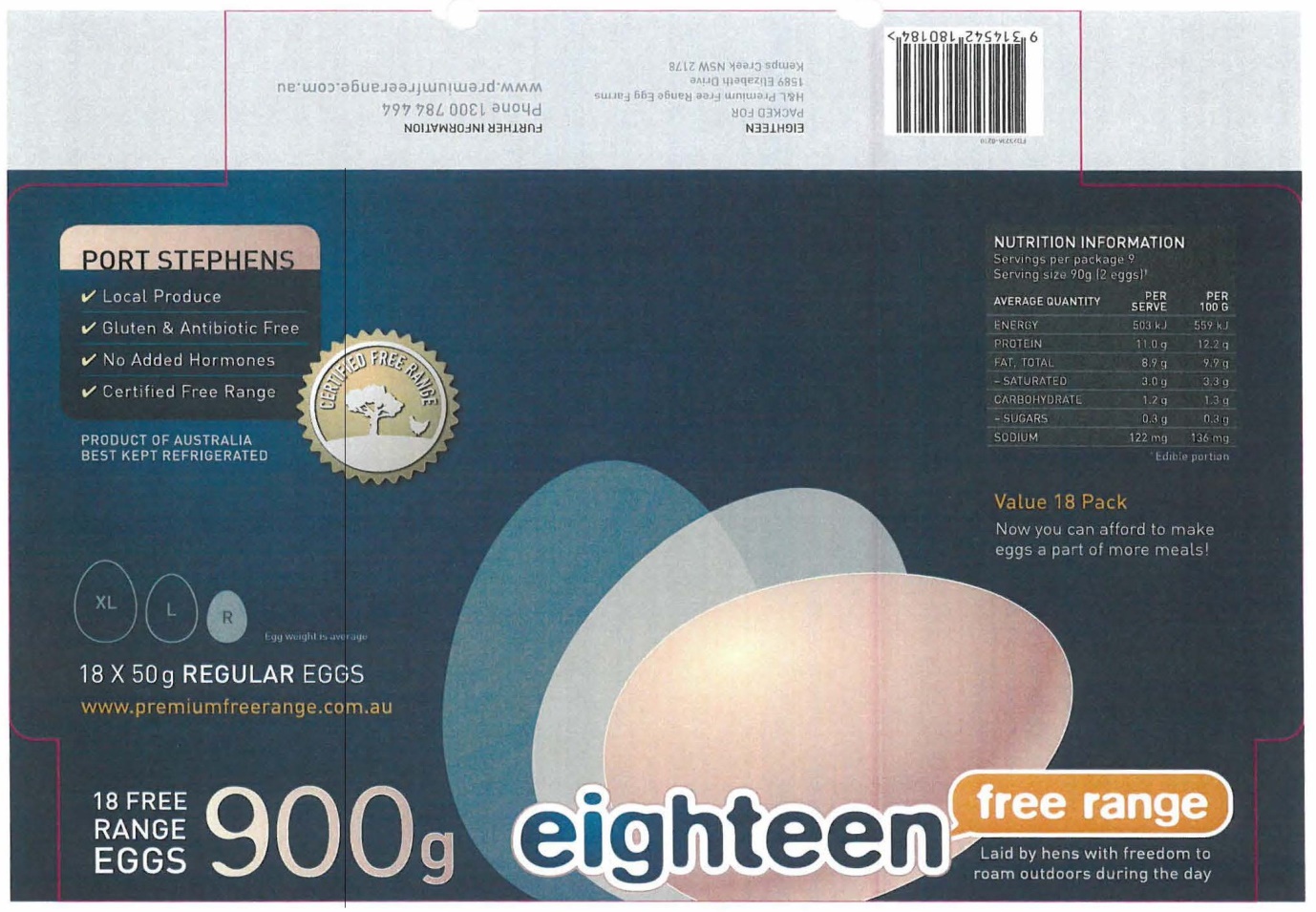

29 Over the 2012 to 2014 period, FREF supplied eggs from the Sepos Farm Barn 5 and the Hutchinson Farm in cardboard cartons that included those labelled “free range” as follows (Free Range Egg Cartons):

(1) until 31 December 2012, in the cartons displayed at Annexure 1 and Annexure 4 to these reasons;

(2) from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2013, in the cartons displayed at Annexure 2 and Annexure 5 and Annexure 7 to these reasons; and

(3) from 1 January 2013 to 2 December 2014, in the cartons displayed at Annexures 3, 6, and 8 to 11 to these reasons.

30 From at least 17 March 2009 until 2 December 2014, FREF advertised its eggs at www.ecoeggs.com.au (Ecoeggs Website). At various times during the period of contraventions (2012 until the end of 2014), the Ecoeggs Website made many representations which were intended to convey that the FREF eggs were free range. The website included an image of a chicken against a background of sky and field, overlayed with the words, “taste freedom” and an image of a hen in a grassy field. Periodically a live remote camera would be shown of an outdoor range when the hens did have access to the range. There was footage of a grassy field overlayed with the words “only 2 hens per square [metre]”. Accompanying descriptions included: “the video shows our happy hens coming out in the morning, dust bathing, running around” and “thanks to our live ChookCam you can clearly see the hens enjoying their outside time, digging, dust bathing and running around”.

31 Although the representations after 11 June 2013 were less extreme, at various times the verbal representations (ie representations in words) included:

(1) “ecoeggs are genuine certified free range eggs”;

(2) “our free range hens graze on open pastures”;

(3) “our farms more than satisfy the most exacting requirements for certification as an approved free range layer farm under independent specifications”;

(4) “are you really buying ecoeggs free range? Each ecoegg is stamped for authenticity which gives you the confidence that you are buying our certified free range eggs”;

(5) “certified, genuine free range eggs”;

(6) “all our ecoeggs farms provide. ... an average maximum of 2 hens [per square metre] outside range area during the day”;

(7) “typically around 50% of our hens will be outside at any one time so this is effectively around 1 hen [per square metre] range area outside”;

(8) “ecoeggs are produced by hens thriving on lush improved pastures”;

(9) “ecoeggs are free-range – genuine and certified”;

(10) “resident hens spend the day roaming pastures in search of seeds and insects”;

(11) “free to move between the range and barn as they please, Ecoegg [sic] farm hens live a life far removed from their caged or barn kept cousins”; and

(12) “[w]e intend to continue to promote genuine free range eggs on a commercial scale with welfare standards superior to our larger competitors”.

32 From at least February 2009 to 2 December 2014, FREF advertised and promoted eggs sold in the Field Fresh carton shown at Annexure 9 to these reasons by publishing a website at http://www.fieldfresheggs.com.au (Field Fresh Website).

33 Until late 2014, the Field Fresh Website displayed an image of the carton at Annexure 9 and an image of three hens against a background of a grassy field and sky with the following words:

(1) “our hens have daily access to our outdoor range, providing opportunity to flap their wings, dust bath and run around”;

(2) “open skies”; and

(3) “free range eggs”.

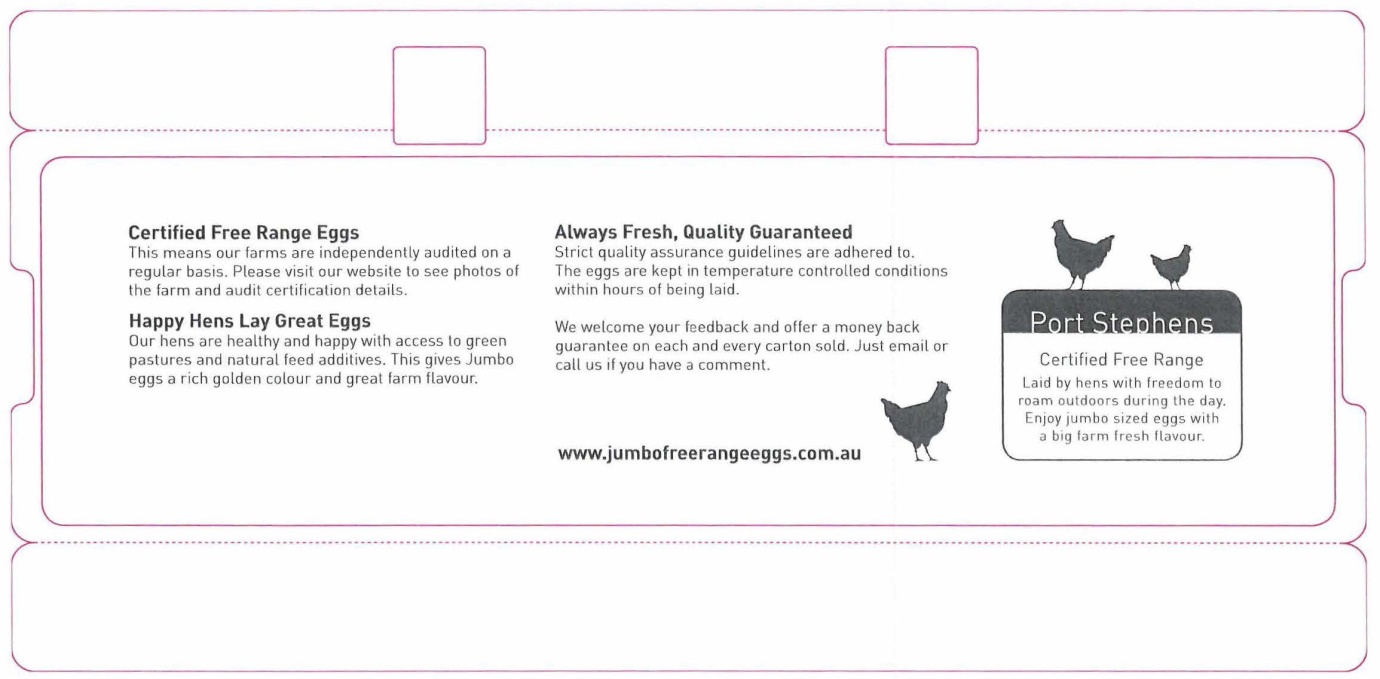

34 From at least May 2013 to 2 December 2014, FREF advertised and promoted eggs sold in the Port Stephens cartons shown in Annexures 10 and 11 to these reasons by publishing a website at http://www.portstephenseggs.com.au/ (Port Stephens Website).

35 Until 2 December 2014, the Port Stephens Website displayed images of each of the Port Stephens cartons and hens in a grassy field and foraging in dirt with the following words:

(1) “genuine free range”;

(2) “our hens are healthy and happy with access to green pastures” (until 20 October 2014);

(3) “our farms more than satisfy the requirements for certification as an approved free range layer farm” (until 3 December 2014); and

(4) “by day [the hens] can range, across open fields in a natural way” (until 20 October 2014).

36 From 8 February 2011 to 2 December 2014, FREF advertised and promoted, and continue to advertise and promote, eggs sold in the Ecoeggs cartons (shown at Annexures 1 to 6 of these reasons) by operating a Facebook account under the name “Ecoeggs Free Range Eggs”.

37 For much of the relevant three year period (2012 to 2014) the Ecoeggs Facebook account displayed a Facebook post that included an image of approximately 10 hens in a grassy field with the caption “happy hens roaming free at one of our Ecoeggs Farms at Booral”. Over much of that period, the Ecoeggs Facebook account posted statements that:

(1) “our farms are certified free range”;

(2) “our hens graze on open pastures”;

(3) “Ecoeggs Free Range Eggs”;

(4) “Ecoeggs are free range - genuine and certified. Resident hens spend the day roaming lush green pastures in search of seeds and insects”;

(5) an image of Ecoeggs cartons and two hens in long grass with the caption “the hens enjoying some grass & sun”; and

(6) “we have been running on average a range density of 2 hens per square meter [sic]”.

38 One post on the Facebook account was:

What a free range farm looks like

We suspect that most people don’t really relate to the facts and figures being put forward by different groups. So we put together a quick video from one of our farms. The video shows our happy hens coming out in the morning, dust bathing, running around…

39 Another read:

We have the new camera installed and have been testing it over the last few days. Very pleased to report it seems to be working flawlessly. Luckily we did not tell the hens how long they have been offline! They’ve been out there prancing around thinking they were still on camera…

40 From at least 20 February 2011 until October 2014, FREF advertised and promoted eggs sold in the Ecoeggs cartons by operating a Twitter account under the name “Ecoeggs”. From at least 4 April 2011, the Ecoeggs Twitter account displayed the words “free range”.

41 In March and April 2013, FREF advertised and promoted free range eggs by a print advertisement in Prevention Magazine (Ecoeggs Print Advertisement). That advertisement is at Annexure 12 to these reasons. The Ecoeggs Print Advertisement displayed an image of hens in a grassy field with the Ecoeggs carton (at Annexure 6 to these reasons). It also contained the following words:

(1) “taste freedom”; and

(2) “our hens enjoy these genuine free range conditions and spend their days roaming lush grassy fields”.

The reasons why FREF’s representations were misleading

42 FREF admits that it contravened three different provisions of the Australian Consumer Law in the period of nearly three years from 1 January 2012 until 2 December 2014.

43 First, it engaged in conduct in trade or commerce that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law.

44 Secondly, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, and in the promotion of the supply of goods, it made misleading representations that the goods were of a particular quality, or have had a particular history, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law.

45 Thirdly, it engaged in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of the goods, in contravention of s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law.

46 Each of these admissions should be accepted. As FREF correctly conceded, in relation to each of the seven media I have described above (the egg cartons, the three websites, the Facebook account, the Twitter account, and the print advertisement), FREF made a representation as to the quality of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons, their nature, history, and characteristics. That representation was that the eggs supplied in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced:

(1) by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day (where an “ordinary day” is every day other than a day when on the open ranges weather conditions endangered the safety or health of the laying hens or predators were present or the laying hens were being medicated); and

(2) by laying hens most of which moved about freely on an open range on most days.

47 Contrary to this representation, during the relevant three years from 2012 until 2014, at Barn 5 of the Sepos Farm and Hutchinson Farm from which the eggs were derived, the laying hens were only able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day in the circumstances I have described. Those circumstances also meant that most of them were not able to move around freely on most days. Those circumstances included:

(1) flock size;

(2) dimensions of the barns in which laying hens were housed;

(3) size, placement and operation of the physical openings to the open range; and

(4) size, physical appearance and condition of the outdoor range.

48 FREF’s admission should therefore be accepted that the representation at [46]:

(1) was a false or misleading representation as to the quality of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons;

(2) was a false or misleading representation that the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons had a particular history;

(3) was liable to mislead the public as to the nature of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons; and

(4) was a representation as to the characteristics of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons.

49 The ACCC and FREF jointly propose five categories of orders:

(1) declarations pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth);

(2) payment by FREF (ie by Derodi and Holland jointly) of a pecuniary penalty in the total amount of $300,000 pursuant to s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law;

(3) publication orders pursuant to ss 246 and 247 of the Australian Consumer Law;

(4) an order pursuant to s 246 of the Australian Consumer Law providing for a compliance program for FREF; and

(5) an order that FREF (ie Derodi and Holland jointly) pay the ACCC’s costs of this proceeding fixed in the amount of $35,000.

The nature of the orders as consent orders

50 All of the orders sought by the ACCC are proposed with the consent of Derodi and Holland. In deciding whether to make orders that have been proposed with the consent of all parties, the Court must be satisfied that it has the power to make the proposed orders, and that the orders are appropriate: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc and Others [1999] FCA 18; (1999) 161 ALR 79, 80 [1], 86 [17]-[18] (French J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Virgin Mobile Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 1548 [1] (French J).

51 Although the Court should review proposed consent orders as to penalty carefully, there is a well-recognised public interest in the settlement of cases: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285, 291 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ); Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 90 ALJR 113, 127-128 [57]-[59] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ). As French J said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc and Others (1999) 161 ALR 79, 86 [18]:

The court has a responsibility to be satisfied that what is proposed is not contrary to the public interest and is at least consistent with it. ... Consideration of the public interest, however, must also weigh the desirability of non-litigious resolution of enforcement proceedings.

52 Four categories of the orders present little difficulty. They can easily be seen to be appropriate. The fifth category, the pecuniary penalty, is less immediately apparent. It is necessary to set out in some detail my process of reasoning which has assisted me to reach the conclusion that the proposed penalty is an appropriate penalty.

Pecuniary penalty considerations

53 Section 224(1) of the Australian Consumer Law permits the Court to impose a pecuniary penalty on a person who has contravened, or has been knowingly concerned in a contravention of a provision of Part 3-1 of the Australian Consumer Law (which includes ss 29 and 33). The Court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalties in respect of “each act or omission” as the Court determines to be appropriate. However, relevantly to the overlapping breaches in this case of ss 29(1) and 33, the Australian Consumer Law provides in s 224(4)(b) that where the same conduct contravenes two or more provisions, a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of the same conduct.

54 The principles concerning the approach to be taken to pecuniary penalties, including the factors to be considered and the central underlying importance of deterrence, are very well known. I discussed many of them in detail recently in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44 [122]-[137], [159]-[160], [175]-[176]. I rely on those remarks without repeating them.

55 An important consideration is the maximum penalty. The maximum penalty for a corporation is $1.1 million for each contravention: see s 224(3) of the Australian Consumer Law. In this case, numerous contraventions can be identified by Derodi and Holland. Although this would strictly permit an enormous maximum to the possible penalty, the award of a penalty must be made by reference to principles of proportionality with the contravening conduct. These principles are commonly described as one limb of the totality principle. One aspect of this limb of the totality principle, or (on another view) a matter closely related to it, is that a court will consider the number of courses of conduct involved in the process of assessing a pecuniary penalty.

56 In this case, the parties submitted that FREF’s conduct should be treated as a single course of conduct. The number of courses of conduct involved in multiple contraventions often depends upon the level of generality with which the contraventions are approached. Here, the parties have proceeded on the basis that the representations involved the same subject matter and had broadly the same content. The parties adopted this approach in their pleadings, their admissions, their statement of agreed facts, and their joint submissions. I am content to do the same.

57 Far less obviously correct is what appears to have been the assumption of the parties that Derodi and Holland should be treated as a single entity. Although they were both trading as a partnership (FREF), they are separate corporations. However, I proceed on the basis that the two companies should be treated as though they were a single entity in circumstances in which (i) the actual maximum penalty is many multiples of $1.1 million, (ii) the financial affairs of the two companies appear to be treated and accounted for jointly, (iii) the size of the respondents for the purposes of assessing penalty has been assumed by the parties to be based on the size of FREF, (iv) any penalty imposed upon one of the corporations would directly affect the other, (v) as senior counsel for Derodi and Holland observed, the same approach was taken in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 5) [2013] FCA 1109; [2013] ATPR 42-450, and (vi) the parties have proceeded on this basis.

58 I turn then to consideration of each of the relevant factors to the assessment of the pecuniary penalty in this case.

The nature and scale of the contraventions

59 The contravening conduct in this case was significant. It occurred over nearly a three year period from 2012 to the end of 2014. It involved a widely consumed food, and concerned representations upon which consumers were heavily reliant. The eggs were supplied in New South Wales, Victoria, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. They constituted approximately 2.36% of the Australian free range egg market and approximately 33% of the eggs FREF marketed as free range. At almost every place (on websites, Facebook, Twitter, and print advertisements) where a consumer might attempt to verify those representations, FREF repeated them.

60 FREF accepts that the dominant “free range” message was conveyed in relation to its Ecoeggs brand. That brand constitutes approximately 35% of FREF’s sales. The contravening conduct in relation to Ecoeggs was often the most prominently stated attribute of the goods being offered for sale, and was a dominant factor in achieving the price premium.

Loss to consumers and competitors

61 The loss and damage suffered by consumers and competitors of FREF cannot be quantified but it exists and is likely to be significant.

62 The loss to consumers includes the price premium they paid to acquire eggs because they thought the eggs were free range, when those eggs were not. That premium is substantial. The loss to competitors is the loss of sales to those consumers who would have switched to the competitors’ free range eggs if the customer had known the misleading nature of FREF’s representations.

63 The amount of the price premium for free range eggs varied from time to time between retailers and between FREF’s products. The approximate premium for free range labelled eggs over “barn laid” or “cage free” eggs was between 50 cents and $3.88 per dozen. However, the price premium in respect of the Ecoeggs brand was not based solely on the free range characteristics of the eggs, but also the patented additive to the feed given to the chickens which resulted in the eggs containing increased levels of Omega 3, Vitamin E, B12, Vitamin D, folate, iodine, selenium and superior O3 to O6 ratio levels.

Size of the contravening company

64 FREF has been engaged in the business of marketing and selling eggs as “free range” since November 2002. The two companies that comprise FREF are substantial companies. They are very profitable. FREF sought to maintain confidentiality of its accounts although senior counsel properly accepted that there might be a need for the Court to refer to FREF’s profits or sales figures. However, in circumstances in which the parties have not provided details of its accounts beyond 2012 nor broken up the profit according to the proportion of contravening products, there is little benefit in revealing FREF’s profitability. It suffices to say that between 2012 and 2014, the proportion of eggs supplied from Hutchinson Farm and Barn 5 of Sepos Farm constituted approximately 2.36% of the Australian free range egg market and that FREF might, on one view, have profited as much from the contraventions as the contravening party in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pirovic Enterprises Pty Ltd (No 2) [2014] FCA 1028; [2014] ATPR 42-483.

65 Neither Derodi nor Holland have previously been found by a court to have contravened any provision of the Australian Consumer Law or to have engaged in similar conduct to that described in these reasons.

Cooperation with the ACCC and contrition

66 FREF did not make any admissions that it had engaged in wrongdoing during the investigative phase and litigation phase prior to November 2015. However, since that time FREF co-operated with the ACCC to settle the liability aspect of the proceeding, and also agreed to all of the proposed remedial orders with the ACCC. FREF’s cooperation has saved the community the cost and burden of litigating a fully contested trial on liability.

67 FREF’s cooperation, and its steps taken in compliance, are evidence of its genuine contrition.

68 During the relevant period from 2012 to 2014, FREF did not have a compliance program to assist it to ensure that it met its obligations under the Australian Consumer Law. However, on 1 August 2014, before this proceeding commenced, Derodi implemented a compliance program in relation to FREF’s marketing, retailing, and operations on all of the farms from which FREF procures eggs. Its compliance program has been implemented by:

(1) appointing a Senior Compliance Manager to oversee the regulatory control and discipline for non-company owned operators, marketing, cost-saving and strategic aspects of the FREF business;

(2) holding regular compliance meetings between senior managers of FREF; and

(3) engaging a Farm Development Supervisor on a full-time basis who has responsibility for bird welfare and general farm productivity performance.

69 At the hearing of this matter, Derodi and Holland specifically relied upon evidence from the Farm Manager of Sepos Farm concerning steps which have now been taken to ensure compliance. The few paragraphs of the Farm Manager’s evidence which were read at the hearing included the following:

Presently, four sheds have winches on them that are used to open the popholes by hand. The popholes on the remaining shed are on a timer which opens them automatically. ... The popholes are opened at approximately 11.00am each day and close at approximately 9.00pm at night. This is done because most hens lay their eggs in the morning

…

Over the past few years, during the Relevant Period, we have doubled the number of popholes on the Farm.

…

Over the past 12 months, I have worked with FREF in relation to a number of FREF’s initiatives to further improve the Farm. Some of these improvements include:

(a) increasing the number of pop holes in each of the sheds

(b) installing automatic winches to allow for the popholes in each shed to be opened and closed automatically according to a set timer

(c) cutting additional drains on the range areas so that the range may dry quicker and the hens can be let out sooner after rainfall

(d) arranging for a dedicated Farm Development supervisor by the name of Mario Gauchi, to keep an eye on the health and welfare of the hens and the productivity of the Farm.

Involvement of senior management

70 FREF’s senior management engaged in the contravening conduct. From 2012 until 2014, the Farming Manager, Mr Scott:

(1) conducted inspections of Sepos Farm and Hutchinson Farm, usually weekly;

(2) provided written reports in relation to his inspections of Sepos Farm and Hutchinson Farm to Mr Leach and Mr Holland; and

(3) notified Mr Leach and Mr Holland in his written reports of his concerns that at various times the birds in some barns were not free ranging, and that he did not at all times consider that the eggs were “free range”.

71 Despite this, Derodi and Holland, through their directors and senior managers, did not take sufficient steps to prevent the contravening conduct.

The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended

72 As I explained in the introduction to these reasons, the words “free range” are now very well known. They are not puffery like “the best goods” or the “finest clothing”. They involve a representation with real content which, in this case, was coupled with powerful pictorial and verbal imagery. The directors of Derodi or Holland must have been fully aware of the significant import and power of their representations. Initially, evidence was filed that showed that Derodi was also aware in 2013 of the CHOICE “Shonky Award”. But the ACCC did not read that evidence. As I have explained, FREF was informed by Mr Scott during the relevant period (2012 to 2014) that the hens were not free ranging at certain times.

73 The ACCC did not plead a case that FREF acted intentionally. No such suggestion was made. Although such a finding might have been open, and possibly even easily reached, in the absence of any pleading, any submission, and any contested evidence I proceed on the basis that the contraventions were no more than careless failures in circumstances involving a want of sufficient compliance measures.

74 There was also no attempt made to contradict the evidence from FREF that in marketing and promoting its eggs as “free range” it had regard to whether the farming conditions were consistent with the practices of some of its free range competitors. Nor did the ACCC contradict FREF’s explanation that at various times when the hens were confined this was for reasons including the construction of a dam and weather conditions.

Previous penalty decisions in the poultry industry

75 It is always necessary to take great care in the process of considering comparative cases for the purposes of assessing a penalty. Although the rule of law dictates that like cases should be treated alike, it is rare in this area that cases will be materially alike. As Burchett and Kiefel JJ said in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285, 295, a “hallmark of justice is equality before the law, and, other things being equal, corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties”. Their Honours also emphasised that “[t]here should not be such an inequality as would suggest that the treatment meted out has not been even-handed”. However, their Honours went on to say that different circumstances mean that “other things are rarely equal where contraventions of the Trade Practices Act are concerned”. In circumstances of materially different facts and where the issue involves the imposition of a penalty where there is no single “correct” penalty, there is not often much benefit in having regard to previous decisions other than to establish a range (which, of course, is not binding) to assist in framing the reasoning process.

76 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams [2015] FCA 1016, I summarised the penalty decisions in cases involving misleading “free range” representations. It is unnecessary in this case to repeat that summary. The cases included Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CI & Co Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1511; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bruhn [2012] FCA 959; [2012] ATPR 42-414; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 19; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 5) [2013] FCA 1109; [2013] ATPR 42-450; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Luv-a-Duck Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1136; [2013] ATPR 42-455; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pepe’s Ducks Ltd [2013] FCA 570; [2013] ATPR 42-441; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pirovic Enterprises Pty Ltd (No 2) [2014] FCA 1028; [2014] ATPR 42-483.

77 The penalties in those cases range dramatically from a combined $50,000 penalty on two individuals to joint pecuniary penalties of $400,000 imposed on two of Australia’s largest chicken meat companies. Although a range is emerging slowly, the considerably different circumstances do not yet reveal a clear range. Further, as I explained in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams, there may be reason to consider that the penalties being awarded in this area are inadequate for general deterrence.

78 Perhaps the most comparable cases here are Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pirovic Enterprises Pty Ltd (No 2) where a joint submission of a pecuniary penalty of $300,000 was accepted by the Court, and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams, where I imposed a penalty of $250,000. The limited information before me in this case suggests that FREF could be a more profitable enterprise than either Pirovic Enterprises or RL Adams. However, as I have explained, a direct comparison of one or two cases involving numerous different factors is rarely, if ever, useful.

Conclusion and appropriate orders

79 First, declarations of contravention in the form sought by the parties are appropriate under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). The declarations will record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the ACCC’s claim, inform consumers of the contravening conduct and assist to deter other corporations from contravening the Australian Consumer Law: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v The Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; [2007] ATPR 42-140 [6] (Nicholson J).

80 Secondly, as to penalty, the parties submit that, having regard to the importance of deterrence and the application of the penalty factors, a penalty of $300,000 is an appropriate penalty for FREF’s conduct. The penalty represents a significant proportion of FREF’s equity base. I am satisfied that it will be an adequate specific deterrent. I am less satisfied that the penalty will be sufficient to operate as a general deterrent but in the absence of any industry evidence or submissions on general deterrence I do not conclude that $300,000 is an inadequate general deterrent. However, I retain the same concerns that I expressed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams at [53]-[55].

81 In Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 90 ALJR 113, 126 [48], French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ reiterated that although the Court is not bound by the figure suggested by the parties, the Court can ask “whether their proposal can be accepted as fixing an appropriate amount”. Since there is no such thing as the appropriate amount, it is possible (as in this case) that although a court might have imposed a different penalty, the court will still be satisfied that the proposed penalty is an appropriate amount. Indeed, as the joint judgment in the Fair Work case explained, it is “highly desirable in practice” for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty (128 [58]).

82 After careful consideration of all the material before the Court, I am satisfied that a pecuniary penalty of $300,000 is an appropriate pecuniary penalty to be imposed upon Derodi and Holland, with their liability to ensure payment of that single penalty to be joint and several.

83 Thirdly, as to the compliance orders, it is appropriate to order under s 246 of the Australian Consumer Law that the respondents establish and implement a compliance program to assist in ensuring that they avoid future contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law. The compliance program required by the orders is linked to the relevant contravening conduct. Many aspects of the program have already been implemented and appear to be operating effectively.

84 Fourthly, the corrective advertising orders sought are appropriate under s 246(2)(d) of the Australian Consumer Law. They serve to alert affected consumers to the fact of the contraventions: Janssen Pharmaceutical Pty Ltd v Pfizer Pty Ltd [1986] ATPR 40-654; (1985) 6 IPR 227, 237. This level of notification is appropriate because FREF relies on promotional material on the Free Range Egg Cartons, the FREF websites, the Ecoeggs Facebook account and the Ecoeggs Twitter account to sell its products. The proposed notifications also serve further to educate the industry about the requirements of the Australian Consumer Law.

I certify that the preceding eighty-four (84) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Edelman. |

Associate:

Ecoeggs Print Advertisement