FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 236

Table of Corrections | |

Windsurfing International Inc v Petit [1984] 2 NSWLR 196 has been added to the cases cited on the cover page. | |

8 November 2016 | The number of paragraphs on the cover page has been updated from “279” to “282”. |

8 November 2016 | In para 13, third sentence, the word “always” has been replaced with “generally”. |

8 November 2016 | In para 28, the sixth sentence commencing “An opening of this axial passage…” has been deleted. |

8 November 2016 | In para 64, fifth sentence, the word “items” has been replaced with “item”. |

8 November 2016 | In para 83, last sentence, the word “in” has been replaced with “of”. |

8 November 2016 | In para 103, third sentence, the words “of the gravity” have been deleted. |

8 November 2016 | In para 111, second sentence, the words “those of” have been inserted before the words “the parties” and the word “to” has been replaced with “in” immediately after the word “parties”. |

8 November 2016 | Three new paragraphs have been inserted at para 126. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 153 (now 156) the para cross-reference to “145” has been updated to “148”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 156 (now 159), the two para cross-references have been updated from “137” to “140”, and “139” to “142”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 170 (now 173), the first two sentences have been re-worded. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 178 (now 181), third sentence, the word “edges” has been replaced with the words “flat faces”. |

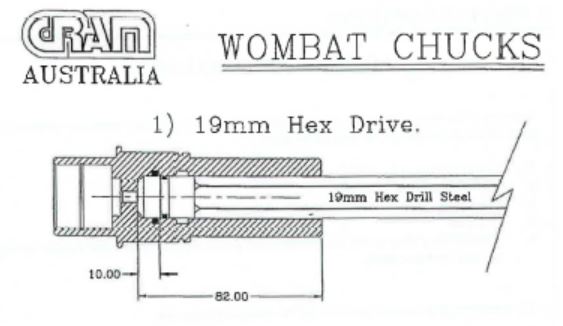

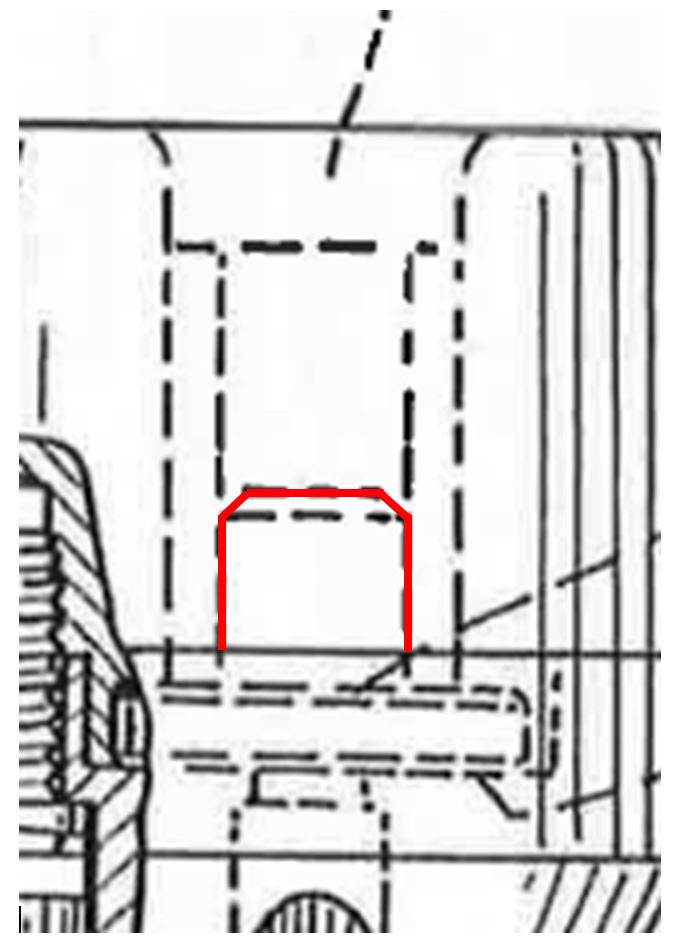

8 November 2016 | In previous para 180 (now 183), the description between the two figures has been re-worded. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 193 (now 196), the para cross-reference has been updated from “176” to “179”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 195 (now 198) the words “As I have indicated” have been deleted from the first sentence. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 216 (now 219), in the seventh sentence, the word “respect” has been replaced with “extent”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 230 (now 233) the two para cross-references have been updated from “171 and 172” to “174 and 175”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 233 (now 236), the words “Likewise, in one of his affidavits” through to “absence of this assumption” have been replaced with “Here Mr Charlton was, as I would understand him, equating usefulness with the notion of something working “well”. But the threshold of utility is not a particularly high one and, in the context of a claim for a system, if what is claimed attains the result promised by the inventor and works, it is not, in my view, fatal under s 18(1)(c) of the Act that the resulting system does not work “well”. In the case at hand, the inventors made no promise as to the efficacy of their system for improving, or even maintaining, water pressure along the drill string, and it may be that the skilled addressee would perceive in so much of the system as is claimed in Claim 1 the making of significant compromises in that department. But, as I say, utility can only be assessed by reference to what was claimed. The circumstance that a more satisfactory system might have been invented is not tantamount to a conclusion that the invention, as claimed, is not useful.” |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 234 (now 237), the first two sentences have been deleted. The words at the start of the third sentence “In such a setting” have been replaced with “For these reasons”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 247 (now 250), last sentence, the word “are” has been replaced with “were” and the word “is” has been replaced with “was”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 275 (now 278), fifth sentence, the para cross-reference has been updated from “249” to “252”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 276 (now 279), second sentence, the para cross-references have been updated from “265-266” to “268-269”. |

8 November 2016 | In previous para 278 (now 281), first sentence, the words “in so far as it relates to Claims 1-4 and 6-7,” have been inserted after the word “Patent” and the word “wholly” has been deleted. |

8 November 2016 | The certification at the end of the reasons has been updated from “279” paragraphs, to “282” paragraphs. |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Amended Originating Application be dismissed.

2. So far as it relates to Claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, Australian Patent No 744870 be revoked.

3. The parties file and serve written submissions as to costs as follows:

(a) the respondent, within 14 days;

(b) the applicants, within a further 14 days;

(c) the respondent in reply, if necessary, within a further seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JESSUP J

1 In this proceeding, the applicants, Sandvik Intellectual Property AB and Sandvik Mining and Construction Australia (Production/Supply) Pty Ltd, allege that the respondent, Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd, has infringed Claims 1-4 of Australian Patent No 744870 (“the Patent”), of which the applicants are the proprietor and the exclusive licensee in Australia respectively. They seek declarations, injunctions, orders for delivery up and damages or, at their election, an account of profits. They also allege that the respondent’s conduct of which they complain amounted to contraventions of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“the TP Act”) and of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“the ACL”), Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); and they seek corresponding remedies under those provisions.

2 The respondent cross-claims for the revocation of the Patent, in relation to Claims 1-4, 6 and 7, on grounds to which I shall refer, but which include lack of novelty, lack of inventive step, lack of utility, and failure to describe the best known method. I shall elaborate upon those grounds in due course.

THE RELEVANT FIELD OF TECHNOLOGY

3 The field of technology with which the case is concerned is what is described as extension drilling in underground mines, specifically coal mines. The description of the background technology which follows below is substantially taken from the evidence of Paul Charlton, an engineering consultant working in the mining machinery industry called by the applicants.

4 Traditionally, the structural integrity of the roofs of underground roadways in coal mines was secured by the use of timber supports. Since the 1970’s, however, bolting systems have been used for this purpose. In the presently relevant context, I need mention only roof bolting and cable bolting. Both of these systems work to prevent roofs from collapsing by clamping together the layers of sedimentary material above the void constituting the roadway.

5 Typically, a seam of coal is about 3-5 m thick. The layers of sedimentary material above the coal seam often lack internal integrity. Roof bolting involves the insertion of a series of long solid bolts into the roof of the roadway. In order to do this, it is first necessary to drill holes into the roof of appropriate diameter and length to cater for the bolts. The length of roof bolts is typically within the range 1.5-2.4 m. The lower end of the bolt will be threaded to take a nut. The bolt is inserted into the drilled hole and secured, either by a mechanical means or using adhesive. The nut is then tightened against the surface of the roof. Often there will be a metal plate or washer between the nut and the roof surface to spread the load against the roof surface. The tensioned roof bolts lock, or key, the strata material together.

6 Cable bolts are long flexible bolts, typically in the order of 4-12 m in length. They comprise a series of twisted wire strands. Cable bolts are used in the same way as roof bolts in that they are inserted into the roof of an underground roadway in a mine. Although they will typically be used at the intersections of roadways, they are also used wherever the use of standard roof bolts alone is insufficient to support the roof adequately and additional reinforcement is required.

7 The present case is concerned not with roof bolts and cable bolts as such, but with drilling systems for making the holes into which these bolts will be inserted. The case is specifically concerned with systems for making the long holes required for the insertion of cable bolts, but, since the same power source is commonly used for each, it is convenient to move next to a generic explanation of the technology which is used for drilling roof holes in mines.

8 There are two types of drilling techniques (and associated machinery and equipment) used in mining, namely, rotary percussive drilling and non-percussive rotary drilling. Rotary percussive drilling is utilised where the strata to be drilled typically has a compressive strength greater than 60 Mpa, and involves a rotating drill bit which is hit with a high frequency hammer to burst the strata. Rotary (ie non-percussive) drilling does not involve percussion, but the strata are cut away in a manner which is similar to drilling timber with a hand drill. In percussive drilling, the drilling rotation is anticlockwise. In (non-percussive) rotary drilling, the rotation is clockwise. Coal is relatively soft, thus percussive drilling is rarely required. The drilling of holes for roof bolts, rib bolts and cable bolts in coal mines is almost always done using (non-percussive) rotary drilling equipment.

9 The types of equipment used in the drilling process may be either hand-held or machine-mounted roof bolters. Hand-held roof bolters are lightweight portable units, the vast majority of which are pneumatically powered. They are relatively low-powered units operating at around 100 to 150 psi, being the realistic maximum compressed air pressure available underground due to reticulation losses. In practice, this relatively low power capacity means that the drilling power (feed force, torque and rotational speed) able to be generated is also quite low. Thus units of this kind are limited in their ability to drill quickly and efficiently. There are also hydraulically powered hand-held portable roof bolters, but such units are also low-powered. For a number of presently irrelevant reasons, over time the use of hand-held bolters has become increasingly rare.

10 There are two types of machine-mounted roof bolters, namely, stand-alone roof bolters and bolters incorporated as a part of a continuous miner. Typically stand-alone roof bolters are mounted on vehicles which run on caterpillar tracks and can be driven to position. They carry one or more bolters, or “drilling rigs”. Usually the machine is operated by one or more operators who can drive the machine and operate the roof bolter. Another type of stand-alone roof bolter is a longwall face bolter. In longwall mining it is necessary to install roof and cable bolts in the final section of the longwall, to protect that part of the roof against collapse when the longwall machinery is disassembled and removed. The longwall face bolter is a stand-alone piece of equipment, but it runs on the longwall conveyor system. Longwall face bolters typically have two hydraulic roof bolters, and are used specifically at the end of the longwall block to install roof bolts, rib bolts and cable bolts so that the longwall can be relocated.

11 In the case of a roof bolter which is incorporated into a continuous miner, the bolter itself is essentially the same as a rig found on a mobile bolter. There will normally be at least two bolters, one on each side of the machine, so that a row of bolts can be inserted into the roof across the width of the roadway roof. The bolters can be angled so that one bolt can be inserted vertically and a second inserted at an angle.

12 Machine-mounted bolters are hydraulically powered, typically with an operating pressure in the order of 3000 psi. This provides far greater torque and drilling speed compared with pneumatically-powered hand-held bolters.

13 The main components of a machine-mounted bolter are the rig itself, or mast, and the drill. For a layperson, the best starting-point is to imagine a common handyman’s electric drill, which drives through a chuck into which a drilling bit is inserted and secured. In roof bolt drilling, there is likewise a drill with a chuck, and the chuck receives the drill bit, referred to as a “rod” since it will generally be at least long enough to facilitate the drilling of a hole to receive a roof bolt of 1.5 m in length. This drill, with chuck and rod, is mounted on a mast the top portion of which, called the headplate, is pressed against the roof of the mine where the hole is to be drilled. In the drilling operation, the drill is moved upwards along the mast as the rotating drill rod cuts the required hole into the strata above.

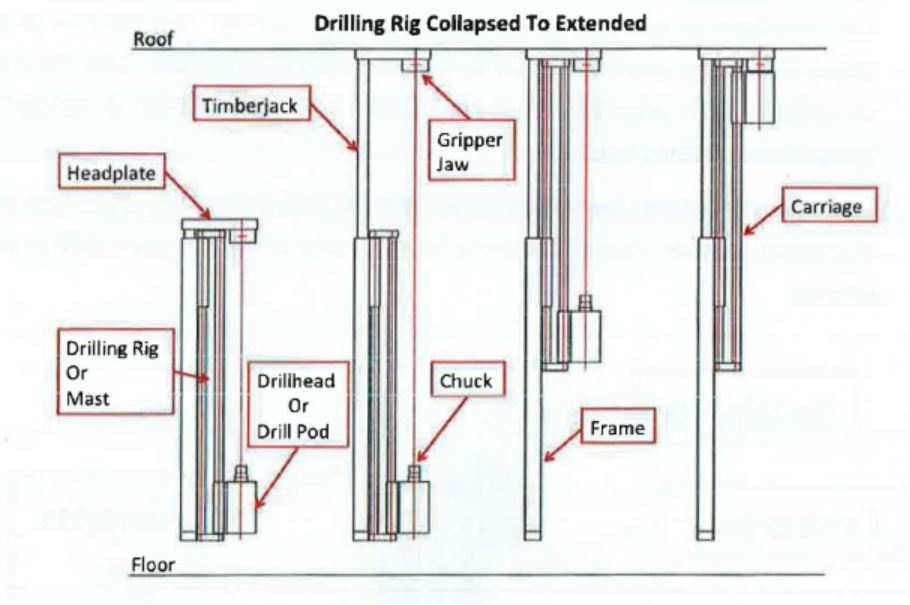

14 In his affidavit, Mr Charlton presented the following diagrammatic representation of the various stages of the drilling operation:

15 The mast is shown in its collapsed state on the left hand side with the drillhead, or drill pod, at its lowermost position. In the next stage the timberjack is raised so that the headplate makes contact with the roof. The headplate steadies the drilling rig and provides a guide for the drill rod once it has been placed in the chuck. Attached to the headplate are “gripper jaws”, the purpose of which will become clear presently but which do not perform a function in single-pass drilling. It is sufficient here to note that the drill rod will pass through these jaws. At this stage, the drill rod has been placed in the chuck, its alignment being indicated by the thin red line running between the chuck at the lower end and the jaw at the upper end. In the third stage, drilling has commenced. The drill chuck apparatus has moved about halfway up the mast. The cutting end of the drill is doing its work in the strata above. When the drill chuck apparatus reaches the underside of the headplate, the drilling process is complete (the diagram on the right-hand side), and the process is reversed. The apparatus is lowered, and the drill rod withdrawn from the roof of the mine. An operation such as that outlined here is referred to as “single-pass” drilling.

16 The drill rods used in single-pass drilling are metal, typically of either hexagonal or round section. They do not include an integral cutting/drilling tip but will be threaded at one end to accommodate the attachment of a cutting tip. The other end of the drill rod forms the drive shaft of the rod. The drive shaft of single-pass drill rods is configured to fit into and be driven by the drive chuck of the drill machine. The standard drive chuck used in hydraulically-powered bolters is the “square locking chuck”. This chuck, and complementary square drive drill rods, were developed in Australia in the mid-1980s, and have been the standard in conjunction with hydraulic roof bolters in the coal mining industry since the early 1990s.

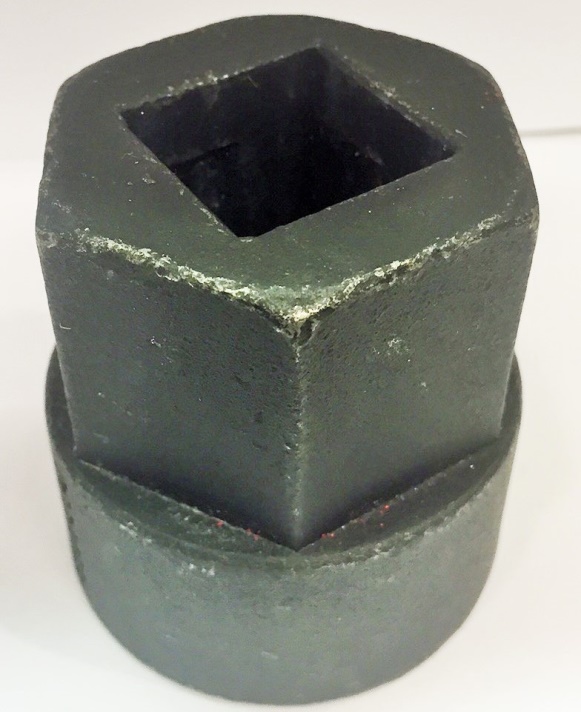

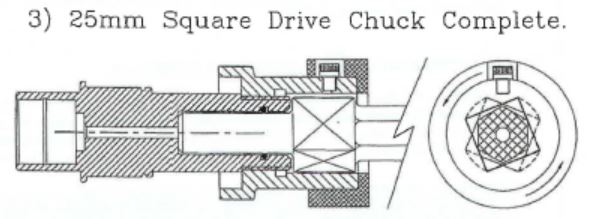

17 An example of a standard 25 mm square locking chuck is shown below, from above (left-hand photograph) and from below (right-hand photograph).

18 The chuck has an upper, a middle and a lower part. The upper part consists of a square opening (as shown on the left-hand photograph above) slightly larger than the cross section of the square section of the drill rod. The lower part consists of an internally-threaded cylindrical section (as shown on the right-hand photograph above) which screws onto the matingly threaded upper end of the driven shaft of the drill motor. The middle part (not visible in the photographs above) consists of the drive chamber of the chuck.

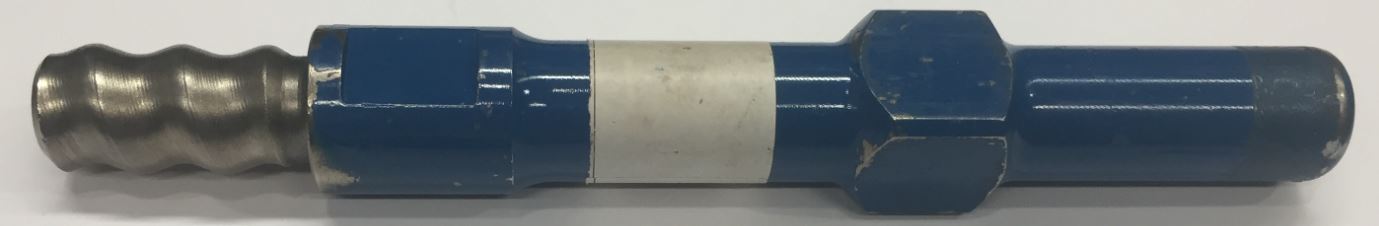

19 An example of the driven end of a single-pass drill rod of the kind used in connection with the chuck described above is shown below.

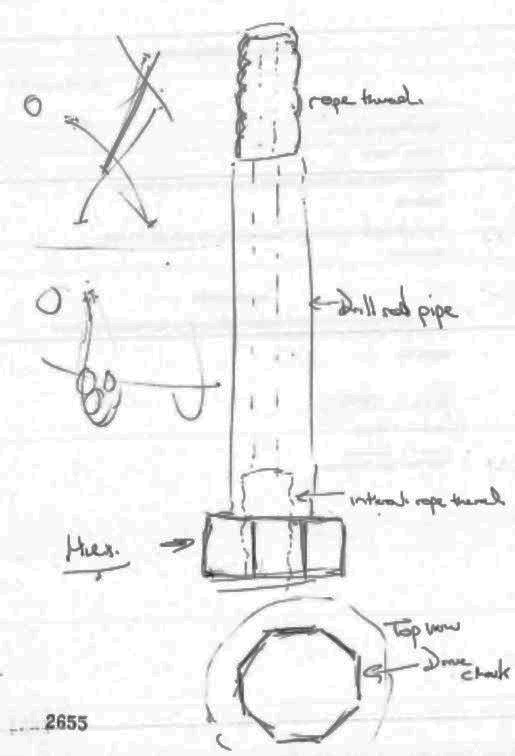

20 With the chuck installed on the drill and ready for use, the drill rod is inserted into the chuck by passing first the round section and then the flat-sided, or square, section through the hole in the upper part of the chuck, to the point where the square section lies wholly within the middle part, or drive chamber, of the chuck. The drive chamber has a series of 12 angled faces in a cross-like configuration and is slightly larger than the square section of the rod, such that the rod may rotate relative to the chamber by about 20 degrees. Once rotated relative to the chuck, the square section of the rod is no longer aligned with the opening of the chuck and is prevented from pulling out of the chuck by the lip of the chuck opening. The configuration of the chuck and the drive shaft is such that when the chuck is operating, the drill rod is locked in place and cannot come out of the chuck. This is a safety measure, as it ensures that, when the drill/chuck apparatus is lowered after the completion of drilling, it does not leave the rod dangling in the roof hole with the risk that it may fall on to operators below: the rod remains secured in the chuck until removed manually.

21 The round section at the lowermost end of the rod – below the square section – is referred to as a “spigot”. It has at least three relevant functions. First, it sits on the base of the chuck and takes the weight of the rod. Secondly, it fits into a corresponding piece in the chuck from which flushing fluid is passed into it and up the drill rod, an important subject which I do no more than introduce at this stage. Thirdly, it fits inside, and thus forms a seal with, an O-ring in that corresponding piece to prevent leakage of the flushing fluid at this point. For that purpose, self-evidently, this spigot must be circular in profile.

22 What I have said to date relates to single-pass drilling. However, where cable bolts are to be used, drill rods of the kind described above are not long enough to drill holes of the required depth. Because of limitations imposed by the height of the mine roadway, to use a single drill rod long enough to drill a hole of up to 12 m in depth would be out of the question. Thus the drill rod used is in fact a string made from round or hexagonal sections of drill rod with complementary male and female threaded ends – by convention the upper and lower ends of each rod respectively. The thread employed in the technology relevant to the present proceeding is right-hand rope thread. Individual rods come in varying lengths, typically from about 0.5 m to 2 m. The first, or uppermost, rod is adapted to receive the drill bit.

23 Ignoring for the moment the means by which the driven end of the lowermost rod communicates with the chuck, at the general level it may be said that drilling for cable bolts involves using a first drill rod with the bit attached to its uppermost end to drill into the mine strata until the length of that rod has been exhausted (in much the same way as done in single-pass drilling), then connecting a second rod between the chuck and the first drill rod, drilling again until the length of the second drill rod is used up, then connecting a third drill rod between the chuck and the second drill rod, and so on until a hole of the length required to accommodate the cable bolt intended to be used has been made. Each time a new rod is connected to its predecessor (ie the one that has been almost wholly driven into the roof strata), the drill/chuck apparatus must be lowered down the drill mast to make room for the new rod. Because the drill string consists of a series of rods built up as drilling proceeds, this technology is referred to as “extension drilling”.

24 It will be immediately apparent that, since each rod must have, at its lower end, an internal female thread adapted to receive the upper male-threaded end of the next rod, the lower end of the any one of these rods could not be fitted with a spigot arrangement of the kind commonly found on rods used in single-pass drilling, as referred to above. The expedient which, some time before the priority date, had come to be used to deal with this issue was the inclusion of an “adaptor” (or “chuck extension” as such things are sometimes called) between the chuck and the lowermost drill rod. At its lower end, such an adaptor had the same cube-and-spigot arrangement as was used on single-pass drill rods. At its upper end, it was fitted with a male thread to engage with the lowermost rod. It was an important aspect of the applicants’ case that roof bolting contractors in the coal mining industry saw this expedient as more convenient than having to change the chuck on a drilling machine each time it was necessary to undertake extension, as opposed to single-pass, drilling. Indeed, the mining experts called by both parties (one of whom was Mr Charlton) were agreed that, as a generalisation, contractors would not contemplate changing a chuck underground during the course of a roof bolting program. An example of an adaptor such as that described above is the following:

25 Using the equipment referred to, the process for extension drilling, as explained by Mr Charlton, involves the following steps:

(a) Insert a drive adaptor into the drill chuck;

(b) Attach a first extension rod (with drill bit included) to the drive adaptor;

(c) Raise the drill chuck, commence drilling and drill to the full length of the first extension rod;

(d) Cease drilling and clamp the gripper jaws onto the lower end of the first extension rod just above the coupling of that rod and the adaptor;

(e) Reverse the rotation of the chuck to uncouple the first extension rod from the adaptor;

(f) Lower the drill chuck;

(g) Attach the top of a second extension rod to the lower end of the first extension rod to create a drill string of (at this point two) extension rods;

(h) Couple the adaptor to the bottom of the second extension rod;

(i) Recommence drilling and drill to the full length of the second extension rod;

(j) Repeat steps (d) to (i), adding additional extension rods to the drill string until the desired length of hole has been drilled.

With respect to steps (d) and (e), the use to which the gripper jaws, first mentioned in para 15 above, are put should now be evident: to uncouple the first (and subsequently each lowermost) rod from the adaptor requires an unscrewing action in which the rod must be held firmly in place while the machine causes the chuck, and therefore the adaptor, to rotate in the reverse direction.

26 Once the drill hole has reached the required depth, it is necessary to remove the drill string, which now consists of a number of rods connected together. Essentially, this process requires the sequential removal of each rod from the string. This must be done in stages. First, the chuck is lowered, bringing the drill string with it. To remove the lowest extension rod from the string requires that rod to be disconnected from the rod immediately above it. The string is lowered to a point where the connection between the lowest rod and the rod above it is immediately below the gripper jaws, such that, when those jaws are engaged, they grip the lower end of the upper rod. The drill is then operated in reverse, imparting an unscrewing action upon the drill string. Because the upper rod is held firm by the gripper jaws, it will not move. Between those jaws and the drill chuck, there are now two points of threaded connection in the string, one between the adaptor and the lower rod and the second between the lower rod and the rod above it. When the direction of the rotation of the chuck is reversed, one of those connections will come unscrewed. It may be either of them. The other connection must then be unscrewed manually, using a spanner.

27 Once the lowermost drill rod has been removed in the way described, the drill/chuck/adaptor apparatus is raised again along the mast to make connection with, and to screw into, the female end of the next rod which, it will be recalled, is just below the gripper jaws. The jaws are then released, the drill/chuck/adaptor apparatus, now with the drill string attached again, is lowered until the lower end of the next rod in line appears below the gripper jaws, the jaws are engaged at that point, and the process described above commences again. And so on, until all the sections of the drill string have been removed.

28 One further common feature of extension (and, according to Mr Charlton, single-pass) drilling which should be mentioned at this stage is the means by which cuttings from the action of the drill bit are cleared away. Here it must be understood that the bit is operating in a confined space and, absent some such means, would soon become clogged with debris from its own action and would jam. Although there are some other methods employed, the most common method in Australia is flushing with water continuously pumped through an axial passage in the drill rod or rods. This is the flushing fluid to which I referred in para 21 above. The drill rods which I have been discussing above, and the adaptors used in conjunction with them, are not solid but have a pipe-like configuration, allowing for the passage of flushing water. In order to inhibit the outflow of water contained inside existing rods on the drill string at the point when the lowest connection is broken to facilitate the insertion of the next rod, some or all of the rods will be internally equipped with a non-return ball-valve arrangement.

29 While on the subject of flushing water, I should also mention a practical issue of some importance which intruded into the evidence, and the submissions, in the case. This water must be supplied to the drill string at a sufficient pressure to cause it to rise vertically, in a narrow tube, over a distance of anything up to about 12 m, and then to carry out the necessary flushing. In a system which involves so many joins, the potential for leakage, and loss of pressure, is apparent. There appears to be little practical difficulty at each male/female threaded connection between the various rods: the connection itself is sufficiently watertight to suit the purposes required. But there is a need for an effective seal at the point where a single-pass rod or an adaptor sits in the chuck. The spigot-and-O-ring arrangement to which I referred in para 21 above was the means by which this problem had been addressed both in the case of single-pass drilling, where the spigot was on the end of the drill rod itself, and in the case of extension drilling, where the spigot was part of the adaptor.

30 What I have described above represents the state of the art, and the common general knowledge, in the industry as at the priority date for the Patent, 11 June 1997.

THE PATENT

31 According to the specification:

This invention relates to an extension drilling system, and more particularly, but not exclusively, to extension drilling systems for use on a semi-automatic drilling rig and used to drill holes (bores) in subterranium [sic] mining operations such as coal mining where the structure of the roof of a tunnel is to be rendered more secure by the insertion of rock bolts into holes drilled into the roof structure.

32 The specification refers to two problems in the existing art, in the following terms:

The primary problem with conventional drill rods for extension drilling systems, when used with semi-automatic drill rigs is that, when the drill string (a series of drill rods coupled together) are to be uncoupled there are two threaded couplings between the grippers and the chuck. As the grippers are operated, and the chuck spun slowly in reverse, the threaded joint between the drive adaptor and the bottom extension rod can become uncoupled which is undesirable as distinct from the desired uncoupling between the bottom and second bottom extension rods.

A secondary problem is that the use of a drive adaptor takes up valuable boom height on the rig thus reducing the length of the extension rods that can be used.

33 The invention is then disclosed in the following terms:

According to the present invention there is provided an extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connected together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having co-operating a male and female right-hand rope threaded couplings at one end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at the other end, whereby the extension rods are connected together by coupling of the male coupling of one extension rod with the female coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods therebetween, a drive chuck of a drilling rig for driving the outside surface of a female threaded end coupling of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, selectively in either forward or and reverse directions, a set of grippers for preventing rotation of clamping an extension rod being arranged to clamp an extension rod at a location so such that only one male/female threaded coupling is provided located between the drive chuck and the set of grippers and so that with the grippers clamping the extension rod, and with the drive chuck being driven in the reverse direction, only the male/female coupling between the grippers and the drive chuck is uncoupled.

According to the present invention there is further provided an extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connectable together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at a male end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at a female end, whereby the extension rods are connectable together by coupling of the male end coupling of one extension rod with the female end coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods and wherein the external surface shape of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck of a drilling rig to drive the female end of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, and wherein the external surface shape of the extension rods between the female end and the male end is of a different and substantially uniform profile.

34 To a large extent, these passages in the specification amount to a recital of the prior art, as outlined above. Central to the applicants’ case is the proposition that they depart from the prior art to the extent that they require that the drive chuck drive “the outside surface of a female threaded end coupling of an extension rod” and that “the external surface shape of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck”. So far as may be discerned from these passages, therefore, the essence of the invention lies in the direct mechanical engagement of the chuck with the lower end of the lowermost drill rod in the string, thereby dispensing with the need for an adaptor. The “primary problem” identified in the specification is overcome because, at the stage of the removal of a rod from the string, there is now only one threaded connection between the gripper jaws and the chuck, namely, the connection between the rod being removed and the next rod above it which is held firm by the jaws. The “secondary problem” referred to is overcome in the sense that it is no longer necessary to use an adaptor. As will appear presently, however, in one of two preferred embodiments of the invention, the use of an adaptor is in fact prescribed by the specification.

35 The specification continues:

Preferably the extension rods have axial passages therethrough in communication with each other and through which flushing fluid is delivered to an associated drill bit. Preferably a non-return valve is incorporated in at least one of the extension rods to shorten the delay time in delivering flushing fluid to the drill bit before re-commencement of drilling after an extension rod is added to the extension rod string.

Preferably the extension rods are of hexagonal, cross-section or any other suitable cross-section and may be forged or welded rods which are selectively or fully heat treated.

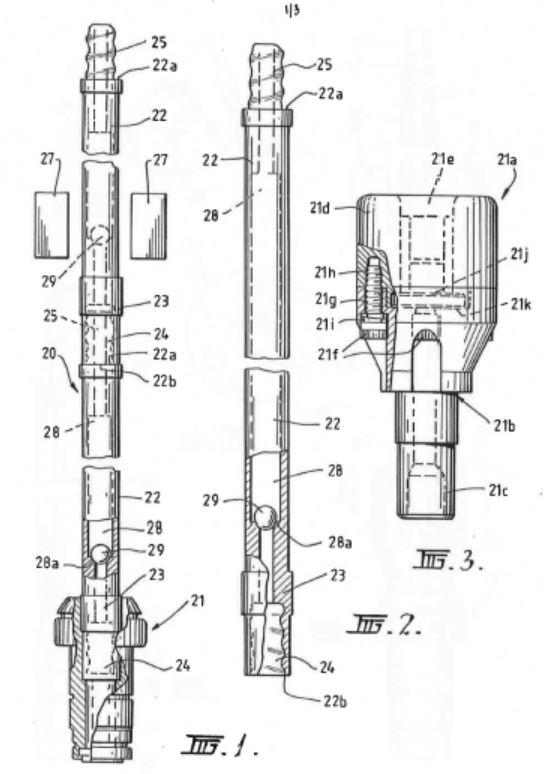

36 Under the heading, “Best Modes for Carrying out the Invention”, the specification describes two preferred embodiments. It does so by reference to diagrams, as follows:

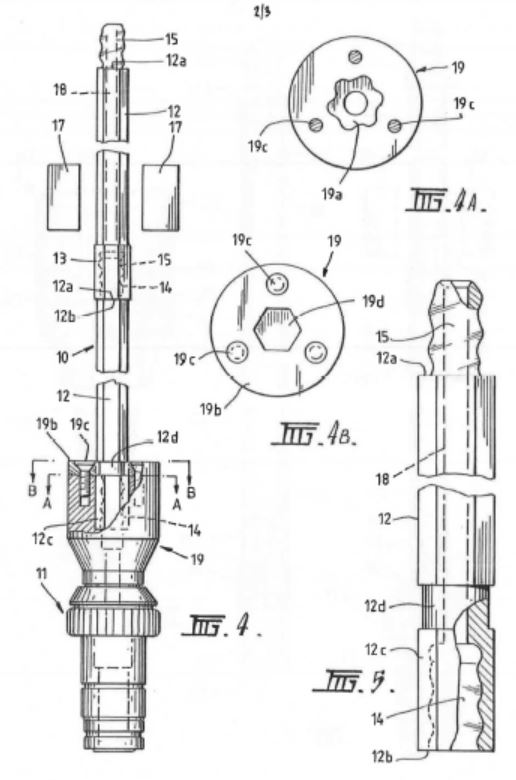

37 According to the specification, Fig 1 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension drilling system in accordance with a first preferred embodiment of the invention. Figure 2 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension rod as used in the system of Fig 1. Figure 3 is a longitudinal side elevational view, partly sectioned, of an alternative direct drive chuck for use in the extension drilling system of Figs 4-5. Figure 4 is a longitudinal side elevational view, partly sectioned, of an extension drilling system in accordance with a second preferred embodiment of the invention. Figure 4A is a cross-sectional view taken along the line A-A of Fig 4. Figure 4B is a cross-sectional view taken along the line B-B of Fig 4. Figure 5 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension drill rod as used in the system of Fig 4.

38 As thus explained in the specification, there are two preferred embodiments of the invention. The first is the subject of Figs 1 and 2, while the second is the subject of Figs 3, 4 and 5. The systems as a whole are depicted in Figs 1 and 4 respectively. The rods to be used in those systems are depicted in Figs 2 and 5 respectively. Greater detail of what is described as a chuck in Fig 4 is given in Figs 4A and 4B, the effect of which is to provide a locking mechanism similar, it seems, to that described earlier in these reasons. What is said to be “an alternative direct drive chuck”, shown in Fig 3, is in fact an adaptor, or “chuck extension”. Apparently, it is presented as an alternative to the chuck depicted in Fig 4 (that chuck itself being described elsewhere in the specification as an adaptor).

39 With reference to Figs 1 and 2, the specification states that the chuck may be “a TL2 drive chuck as manufactured by McSweeney’s, Inc of the USA”. That chuck, to which I shall refer as the “McSweeney TL2 chuck” is the same as the 25 mm square locking chuck, save that the dimensions of the square opening are 28 mm rather than 25 mm. The specification continues that the chuck, which may be the McSweeney TL2 chuck, “directly rotatably drives” a string of extension rods. The means of connection between various rods is described, but is presently uncontroversial. An axial passage is provided through the respective extension rods, it being stepped to provide a transition between larger and smaller diameter portions of the passage whereby to provide valve seats for the ball valve mechanisms.

40 The specification continues:

As illustrated in Figure 2, the external or outside surface of the female socket 24 is engaged by the drive chuck 21 for driving the string of extension rods 22. The surface of the female socket 24 that the drive chuck 21 engages therefore has a profile suitable for that engagement. Figure 2 shows that the surface which is engaged by the drive chuck 21 includes a portion of greater diameter at the position to which the lead line for the reference numeral 23 extends. Extending from the engagement position of the drive chuck 21 to the male member 25, the surface of the extension rod 22 is of a substantially uniform profile and of reduced diameter compared to the diameter at the engagement position of the drive chuck 21. Thus there is a difference in surface profile between the engagement position of the drive chuck 21 at the female socket 24 and the section of the extension rod between the female socket 24 and the male member 25.

41 It should be noted that all but the first two sentences in this passage was added by amendment on 30 August 2006. It should also be noted that, if the McSweeney TL2 chuck were to be used in the system described above by reference to Figs 1 and 2, and since it is a requirement that “the external surface shape of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck”, then, at “the position to which the lead line for the reference numeral 23 extends”, the rod would have to be of a square profile.

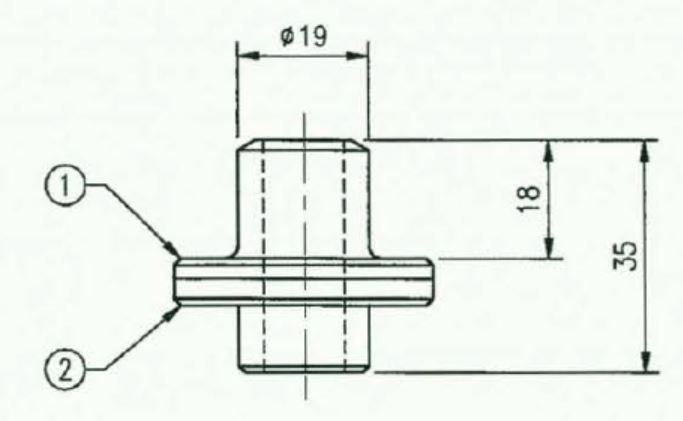

42 What the specification says about Fig 3 is as follows:

Figure 3 of the drawings shows a modified (alternative) direct drive chuck for use in the extension drilling systems of Figures 4 to 5, and is in fact the drive chuck preferred, and which is a modular assembly 21a comprising a male drive member 21b having a drive shaft 21c and coupled to a female drive member 21d with a socket 21e. The drive members are coupled by bolts 21f through holes 21g in the male drive member 21b and into threaded blind holes 21h in the female drive member 21d with interposed spring washers 21i. The male and female members may also be “dogged” together, that is Interlocked. The socket 21e receives a sealing member 21j which may be formed from polyurethane, moulded around a stainless steel washer body, and which seats on a step 21k in the end of the male drive member 21b. The modular drive chuck of this embodiment, in being formed in two separable parts, allows the drive members 21b and 21d to be interchangeable for different drive configurations, and also allows for the sealing member 21j to be replaced when worn.

43 With respect to Fig 4, it is made clear that the chuck itself, which again may be the McSweeney TL2 chuck, is the lowermost portion on the diagram, marked 11. The adaptor is the portion marked 19. After referring to the rods and the connections between them, the specification continues:

With reference to Figures 4 and 5 of the drawings, the internal detail of the chuck adaptor 19 is according to that shown in Figure 4A of the drawings and is shaped as a hexagon 19a offset by 20° of rotation. A chuck adaptor cover 19b as shown in Figure 4B is bolted to the remainder of the chuck adaptor by bolts 19c. The cover provides a hole 19d for the extension rod to fit into and which has a normal hexagonal shape. The end of the extension rod which fits into the chuck adaptor 19, and incorporating the female socket 14 which is not drivingly engaged by the chuck adaptor, has an [sic] hexagonal exterior 12c and above that a round section 12d. When the extension rod end is fitted into the chuck adaptor, the hexagon 12c on the end of the rod is aligned with the hexagonal hole 19d through the chuck adaptor cover 19b. The rod is then slid down into the chuck adaptor to its full extent, and as positive rotation is commenced the chuck adaptor rotates 20° in relation to the rod and the drive flats of the hexagonal 19a in the chuck adaptor engage against the hexagonal shaped end 12c on the rod to thus rotatably drive the rod. The round section 12d on the rod is provided so that, as the rod is rotated through 20°, the hexagon through the chuck adaptor cover 19b does not bind on the rod. As long as positive rotation is maintained in the chuck adaptor the rod cannot be removed as the two hexagons are misaligned by 20° and the rod needs to be rotated through 20° so that the corners of the hexagon 12c will clear the hexagonal hole 19d through the chuck adaptor cover 19b in order for the rod to be removed. The drive chuck as described above in providing a twist locking action between the chuck and the rod improves the safety of the drilling system because of the locking of the rod in the drive chuck whilst maintaining positive rotation.

44 The burden of this passage is to explain the means by which a rod with a female threaded lower end may form a locking engagement which the adaptor into which it is placed, but to which it is not threaded. The principle is similar to that employed in the square locking chuck, but here the engagement is between the rod and the adaptor, rather than being between the adaptor and the chuck. It is apparent, and is expressly required in this embodiment, that the lowermost section of the rod be of hexagonal profile – it is here that the driving force will be imparted to the rod by the adaptor – while, immediately above that, there must be a section which is round in profile to accommodate turning the rod through 20 degrees to bring about the intended locking effect.

45 Whether the remainder of the rod – above the round section – will also be round is the concern of the following paragraph in the specification:

In the case of both embodiments of the invention, the extension rods are of hexagonal cross-section, as previously described with reference to the embodiment of Figure 4 to 5, or of round cross-section or of any other suitable cross-sectional shape whereby they can be driven by the chuck adaptor 19 in the case of the embodiment of Figures 4 to 5 or directly by the drive chuck 21 or 21a in the embodiment of Figures 1, 2 and 3. The extension rods may be forged or welded rods which are selectively or fully heat treated.

46 The specification includes the following claims:

1. An extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connected together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at one end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at the other end, whereby the extension rods are connected together by coupling of the male coupling of one extension rod with the female coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension to rods, a drive chuck of a drilling rig for driving the outside surface of a female coupling of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, in either forward or reverse direction, a set of grippers for preventing rotation of an extension rod being arranged to clamp an extension rod at a location such that only one male/female coupling is located between the drive chuck and the set of grippers and so that with the grippers clamping the extension rod, and with the drive chuck being driven in the reverse direction, the male/female coupling between the grippers and the drive chuck is uncoupled.

2. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 1 wherein the extension rods have axial passages therethrough in communication with each other and through which flushing fluid is delivered to an associated drill bit.

3. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 2, wherein the axial passage through at least one of the drill rods incorporates a non-return valve to shorten the delay time in delivering flushing fluid to the drill bit before recommencement of drilling after a drill rod is added to the drill rod string.

4. An extension drilling system as claimed in any one of the preceding claims, wherein the extension rods are of hexagonal or round cross-section or of any other suitable cross-section whereby they can be driven by the drive chuck either directly or via an adaptor having a socket therein of similar cross-section to the extension rods.

5. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 4, wherein the co-operation between the drive chuck or the adaptor and the extension rod directly associated therewith is such that limited relative rotational movement therebetween misaligns the respective cross-sections to prevent separation of the extension rod whilst maintaining driving engagement.

6. An extension drilling system substantially as hereinbefore described with reference to figures 1 and 2, or figures 3, and 4 as modified by figure 5, of the accompanying drawings.

7. An extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connectable together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at a male end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at a female end, whereby the extension rods are connectable together by coupling of the male end coupling of one extension rod with the female end coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods and wherein the external surface of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck of a drilling rig to drive the female end of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, and wherein the external surface of the extension rods between the female end and the male end is of a different and substantially uniform profile.

NOVELTY

47 The respondent contends that the invention the subject of the Patent, so far as claimed in claims 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7, was not novel in June 1997. Here the question which arises under s 7(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) is whether the invention was not novel in the light of two kinds of prior art information relied on by the respondent, namely (1) the public use of an extension drilling system by Colrok Mining Pty Ltd (“Colrok”) at collieries in New South Wales, including Ellalong and Macquarie, between 1989 and 1994, and (2) the public use of an extension drilling system at the West Wallsend, Gretley and Wyee Mines by an entity described in the evidence (and in the respondent’s Particulars of Invalidity) only as “Wilson Mining”.

48 Darrell Geatches was the respondent’s principal witness called to provide evidence of the extension drilling system used by Colrok. He worked in the mining industry in New South Wales between 1956 and 1994. From 1976 to 1994 he was a co-owner and director of Colrok, a service contractor to the coal mining industry. He was directly involved in the day-to-day management of Colrok’s business and the provision of its services throughout that period. Because his lack of engineering qualifications was highlighted during his cross-examination by counsel for the applicants, I shall refer to the nature of his experience in the mining industry. In 1962, he started work at Newstan Colliery at Lake Macquarie, where he worked as an electrician and leading hand electrician from 1964 to 1969. During that time, he returned to technical college where he obtained his third class certificate of competency in coal mining. His employer then promoted him to Deputy in Charge - Maintenance, Production Units (with continuous miners). This role involved him overseeing a full production crew, he being primarily responsible for safety in the relevant section of the mine. His role included overseeing roof control, gas testing and shot firing. He was Deputy in Charge between 1969 and 1976.

49 In 1976, Mr Geatches left Newstan Colliery and joined Barry Webb as a co-owner and director of Colrok. Mr Webb had been a project manager for some of the larger mining companies before that time, including Allied Construction and Dravo. He had a background in metalliferous mining, which included hard rock and mineral extraction. It was Colrok’s intention to provide support services to companies carrying out stone excavation in coal mines, such as by drilling through igneous intrusions, which were very hard intrusions formed by molten stone coming up through coal steams, which had to be drilled and blasted rather than cut.

50 One of Colrok’s first contracts after he joined it involved drilling holes for roof bolts at the Liddell Colliery. Because of the presence of igneous intrusions, it was necessary to use rotary percussive drilling. Mr Geatches was in charge of overseeing that contract, and was also the site manager for the project.

51 In 1978, Colrok was contracted to undertake what was described as “long hole firing” at the Liddell Colliery. This contract involved not the drilling of holes for roof or cable bolts, but the drilling of holes running between seams, generally of about 25 m in length, for the placement of explosives in the construction of interseam storage bins. The rotary percussive drilling method was used for this project. They used a Roc 601 Airtrack drill rig supplied by Atlas Copco to drive vertical holes from the lower seam to the upper seam. The drill string was made up of rods with male threads on both ends, joined together female/female-threaded couplings. A drill rod was coupled to a “shank adapter” attached to the drive head of the drill. This adapter drove through a male rope-threaded protrusion which connected to the female/female-threaded coupling attached to the first rod.

52 Drilling was commenced and, when the lower end of that first rod was close to the roof of the mine, the rotation of the drill head was stopped, and the rod clamp (effectively what has been described above as the gripper jaw) was engaged so that it gripped the existing rod (at its lower end, near the roof) and held it in place. The drive head was then engaged in reverse, uncoupling the female/female coupling between the shank adapter and the bottom end of the rod. The male end of a second rod was then threaded into the coupling on the lower end of the first drill rod. The lower end of the second rod was then coupled to the male coupling of the shank adapter using another female/female coupling. The drilling process then resumed. Additional rods were added in the same way.

53 Once the hole was drilled to the required length, the rods had to be removed. The percussion function in the drill was used to hit the drill string to loosen the tension in the couplings. The drive head was lowered, and the rod clamp was engaged to clamp the second last rod so as to hold it in place. At this point, there were two female/female couplings between the rod clamp and the shank adapter: the first being the coupling between the shank adapter and the lowermost rod, and the second being the coupling between the lowermost rod and the one above it. The drive head was then operated in the reverse direction, uncoupling one of the two female/female couplings. The other coupling was then uncoupled manually, and the lowermost rod removed.

54 Mr Geatches and his colleagues found this to be a time-consuming process. In order to save time, they usually left one female/female coupling on one end of each male/male-threaded drill rod, and stored them as such. The result was that the drill rods were effectively like male/female-ended rods, each having a female thread at one end and a male thread at the other. Subsequent drill strings were assembled using components stored as such. This practice later led to Mr Geatches’ development of “speed rods”, which were male/female rods like this, but with right-hand rope threads (unlike the rods actually used in the long hole firing operation at the Liddell Colliery which, because percussive rotary drilling was used, were conventionally left-hand threaded). I shall refer to that development in its proper order presently.

55 After the completion of the project at Liddell Colliery, Colrok bought the Roc 601 Airtrack machine and carried out a similar project at West Wallsend Colliery creating an interseam bin.

56 In the mid-1980s, Colrok began installing cable bolts, an early instance being at the Stockton Borehole Colliery at Teralba. In Mr Geatches’ understanding, cable bolts were already then being extensively used in metalliferous mines to support main roadways, but not in coal mines. For the project at the Stockton Borehole Colliery, Colrok had to decide what equipment was best suited to drill the 55 mm diameter holes required to accommodate the cable bolts. Previously, they had drilled 29 mm holes for standard rock bolts. The seam at Stockton gave them only about 1.5-1.8 m within which to work, which meant that they had to use shorter drill rods, but many of them. They commenced by using the Roc 601 Airtrack with a rotary percussive drive head, but this was, Mr Geatches said, “quite savage on the roof strata and started to cause breaks in the roof from the hammering motion”.

57 Mr Geatches and Mr Webb decided that using a (non-percussive) rotary drive head was more likely to be successful in this situation. That required them to source suitable rotary drill rods. It was also on this project that they started to develop suitable rotary drill rig machines. Confident in the future of cable bolting in coal mines, Colrok purchased a number of additional (second-hand) drill rigs, namely, two Joy drill rigs, two Gardner Denver drill rigs and two Atlas Copco drill rigs which were generally similar to its existing Roc 601 Airtrack machine. Those rigs all included rotary percussive motors and were designed to be used on the surface for drilling downwards, rather than drilling upwards. Colrok converted some (Mr Geatches thought three) of these rigs so that they could be used underground to drill vertically into the roof. They also built new drill masts for these drill rigs, as the existing masts were too long. The new masts were fitted with drill rod clamps and feed mechanisms for chain or screw feeds (so that the drive head could be moved up and down the mast). They trialled different types of drill rods with different types of couplings, to see what rods could be coupled and uncoupled most quickly. To increase the speed of uncoupling the drill rods, Mr Geatches thought to use rope-threaded connections. He tried to source suitable drill rods with right-hand rope threads, but without success. In his evidence-in-chief, Mr Geatches said that he did find drill rods with right hand rope thread (male at both ends) available, but they were 19 mm or 20 mm only across the flats, and thus too small for driving the big rotary drill bits that were to be used for the installation of the cable bolts at Stockton. It was put to him in cross-examination that he was mistaken in his recollection that he had found these drill rods, a subject to which I shall return.

58 In the result, Messrs Geatches and Webb, and Brian Woolnough, a mining engineer at Colrok, decided to make their own set of male/female right-hand rope-threaded drill rods with a diameter of 25 mm. Mr Geatches sourced Q7 steel from Roy Gambly (now deceased) at Awaba Road in Toronto. Mr Gambly was, according to Mr Geatches, “a fine precision machinist” who did a lot of machining for Colrok. He made the ends for the new drill rods: an end with a male right-hand rope thread, and an end having a hexagonal outer profile (32 mm across the flats) with an internal female right-hand rope thread. They were made to specifications provided by Mr Geatches, although it became clear, under cross-examination, that he could not recall the actual form of the instructions which he gave to Mr Gambly. That is a subject to which I shall return in due course below. Mr Gambly made about ten sets of the drill rod ends in that first batch. Then, in Colrok’s own workshop, Murray Pearson, a leading hand fitter employed by Colrok, inserted the spigots for the ends into a section of drill pipe and welded around both ends to make the drill rods.

59 In operation, the female end of a drill rod was inserted (and here I quote from Mr Geatches’ affidavit) “directly into the drive chuck (which was in effect an adaptor) on the drill rig, which had a hexagonal shaped socket.” The chuck drove the rod by engaging with the hexagonal external surface of the female end of the drill rod. The new drill rods proved very successful. Being easy to extend and to uncouple, their use led to an increase in the speed at which rods could be inserted into and removed from a drill string. In part, this was because there was no longer the need to uncouple (ie by unscrewing) the lowermost rod from a male shank adapter when building or dissembling the drill string. These were the rods that Mr Geatches and his colleagues described as “speed rods”. In Mr Geatches’ recollection, it was in the mid to late 1980s that Colrok reached this point.

60 At some stage after Colrok had trialled its speed rods, it was visited by Kell Kellstad, the owner of a small drilling equipment and consumables company called Quarry Mining and Construction Pty Ltd (“QMC”), at its (Colrok’s) premises at Toronto. Mr Geatches showed one of the rods to Mr Kellstad, and told him that he had to start making the rods, because they worked. Because of this conversation, which he did recall, Mr Geatches thought that it may have been QMC which subsequently made the rods for Colrok. But Mr Geatches could not say positively that it was.

61 Colrok used these rods in the late 1980s at Ellalong Colliery to drill the holes required to install cable bolts for the establishment of secondary roof support in restitution work after a roof collapse on a conveyor road. Based on his own observation, Mr Geatches described the process in which they were used as follows (in which the rods are referred to as “Geatches rods”):

Step 1 A drill bit was connected to the male end of the first (top) Geatches Rod in the drill string. This was done via a drill bit adaptor. The adaptor had a female right hand rope threaded end that coupled with the right hand rope thread at the male end of the Geatches Rod. The drill bit was connected to the drill bit adaptor.

Step 2 The female end of the top Geatches Rod was placed into the drive chuck socket. It fitted snuggly into the socket, because the socket was of the same hexagonal shape and approximately the same measurement across the flats (i.e., 32 mm).

Step 3 The top Geatches Rod was drilled into the strata. This was done by feeding the drill motor and drive chuck up the drill mast with the right hand rotation and water flushing turned on.

Step 4 Once the top Geatches Rod was drilled into the strata to a point near to its female end, a pair of clamps (fixed to the drill mast) were clamped onto the external surface of the female end of the top Geatches Rod. This provided the support necessary to retain the first rod in the bore hole. The drive motor and chuck were then dropped back down the drill mast to near the ground level.

Step 5 The female end of the second Geatches Rod was placed into the drive chuck socket. The drive motor and drill chuck were raised up the drill mast so that the male end of the second Geatches Rod entered the female end of first (top) Geatches rod.

Step 6 The pair of clamps on the top Geatches Rod were released and the right hand rotation turned on to screw the male end of the second Geatches Rod into the female end.

Step 7 The drill string (i.e., the first and second Geatches Rods) was drilled into the strata by feeding the drill motor and drive chuck up the drill mast with the right hand rotation and water flushing on.

Step 8 Once the second Geatches Rod had entered the bore hole to a point near its female end, steps 4 to 7 above were repeated in order to extend the drill string. At Ellalong, the bore holes were about 8 meters [sic] deep. 6 or 7 Geatches Rods were used per hole.

Step 9 Once the last (bottom) Geatches Rod had been connected to the drill string and drilled into the strata to a point near to its female end, the drive motor and drive chuck were dropped back down the drill mast to a position above ground level. This lowered the drill string such that the last (bottom) and second last (i.e., second from the bottom) Geatches Rods were removed from the bore hole.

Step 10 The pair of clamps was engaged to grip the second last (i.e., second from the bottom) Geatches Rod at its hexagonally shaped female end.

Step 11 The drive motor was driven in reverse (left hand rotation). This broke the threaded connection between the male threaded end of the bottom Geatches Rod, and the female threaded end of the second bottom Geatches Rod. The drill motor and drive chuck were then lowered further down the drill mast and the motor disengaged from the hex drive end.

Step 12 The bottom Geatches Rod was then removed manually by the drill operator.

Step 13 The drive motor and drive chuck were raised up the drill mast and the female end of the second bottom Geatches Rod fitted into the socket of the drive chuck.

Step 14 The pair of clamps on the second bottom Geatches Rod were released.

Step 15 The drive motor and drive chuck were dropped back down the drill mast to a position above ground level. Again, this lowered the drill string. Steps 10 to 14 were then repeated until all of the Geatches Rods had been removed from the bore hole.

62 Colrok subsequently used the new drill rods made by QMC in a number of other projects, including a project at Macquarie Colliery at Teralba between 1987 and 1993. The work carried out by Colrok under that project involved the drilling of holes from inside the underground seam vertically or on an angle to create a methane drainage hole. The methane trapped in the strata would be released into the seam through the drilled holes, and would then be carried out of the mine by the return airway. The drilling at Macquarie Colliery was conducted with Colrok’s rotary drill rigs, using male/female right-hand rope-threaded drill rods, the lowermost of which was seated directly in the chuck.

63 Mr Geatches believes that, before he retired from Colrok in 1994, the drilling rods described above were also used at other projects including secondary support work at each of Wallarah Colliery, Chain Valley Colliery and Wyee Colliery, but he did not recall seeing the rods in use in those places, which he visited less frequently than Macquarie and Ellalong. It was submitted on behalf of the applicants that there was, in the circumstances, no evidence of the use of these rods other than at Ellalong and Macquarie collieries. I am prepared to proceed on that basis.

64 The applicants go further, however, and say that Mr Geatches’ evidence, to the extent that it related to the development and use of the rods described above, should not be accepted at all. They point out, correctly, that that evidence was not supported by the production of any of the chucks or drill rods used, of any contemporaneous drawings or sketches of the rods, of the specifications provided to Mr Gambly, of any photographs of the components that Mr Gambly supplied to Colrok, of any drawings, sketches or photographs of the rods that Colrok assembled from those components, or of any drawings, sketches or photographs of the components actually used at Ellalong. In a number of respects, the applicants’ use of the word “any” in these criticisms reflects the fact that it has not been established that there ever were artefacts of the kind mentioned. It was not suggested on behalf of the applicants that either Mr Geatches or the respondent had selectively opted to withhold from the eye of the court objects, photographs or drawings which might have been led in evidence. Elsewhere in his evidence, Mr Geatches made it clear that he did not regard his rods as inventive (unlike another, in some respects similar, item which he devised, and for which he applied for a patent), and he had, I would hold, no reason, before he retired from Colrok in 1994, to anticipate that a record of their development or use might later be useful in litigation. I regard the absence of the things referred to by the applicants from the evidentiary record as relevantly neutral in its impact on the task in which the court is engaged: the fact is that there is no such evidence, but that fact should not introduce an additional element of unreliability into the evidence which was led.

65 The applicants also drew attention to what they described as five “errors” in Mr Geatches’ recollection of the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first related to the following paragraph in his first affidavit:

Annexed hereto and marked “DWG-2” are photos of me and other Colrok employees working on the West Wallsend Colliery project in around 1978 and a range of other photographs of various dates showing drill rigs that drove extension drill strings directly on the external surface of square and hexagonal profile drill rods, also taken by Brian R Andrews.

This paragraph came before Mr Geatches’ first mention of the installation of cable bolts by Colrok in the mid-1980s. It came well before his first mention of the development of rods which were driven via the external surface of a female-threaded lower end. Of that paragraph, the applicants made the following submission in their written outline:

In cross-examination, however, he identified only one photograph which showed extension drill strings and this was a photograph which showed:

(iii) male/male extension rods joined together by female/female couplings; and

(iv) which engaged with the drive motor via male shank adaptor – the male shank adaptor screwing into the bottom-most female coupling and driving it on the internal surface,

not a male/female extension rod being driven on the outside surface of the female end at all.

66 A number of things may be said about this submission made on behalf of the applicants. First, the passage, “he identified only one photograph” should not be understood as implying that Mr Geatches was invited to identify any photograph which showed an extension drill string: he was taken to the photographs in the annexure and answered the questions that were put to him about them. Secondly, responding to one such question, Mr Geatches accepted that the drill string which he did identify was (using cross-examining counsel’s words) “a left-hand percussion device”. He did so readily and in a way which, to my observation, reflected a thorough command of the subject. Thirdly, to the extent that the cross-examination of Mr Geatches in these respects was intended to underline the absence from the evidence of any photographic representation of the rods that Mr Geatches and his colleagues later developed, it was legitimate and justified. What might otherwise have been the impression left by the corresponding paragraph in Mr Geatches’ affidavit as such was thereby corrected. But the additional step of building upon that cross-examination a submission that the reliability of Mr Geatches’ evidence generally was undermined because of this “error” was not, with respect to those involved, legitimately taken. Mr Geatches was not cross-examined along that axis. Self-evidently the error arose in the compilation of the annexures to the affidavit and, while Mr Geatches might legitimately be criticised for failing to check the annexures for accuracy, that was not the thrust of the cross-examination and, further, it does not, in my view, reflect adversely upon his ability to recall, and to describe, the events of which he gave evidence.

67 The second error which, according to counsel for the applicants, Mr Geatches had made in his evidence was to state that he had, in the mid to late 1980s, found 19 mm or 20 mm right-hand threaded drill rods (see para 57 above). In his affidavit, he had said that, to the best of his recollection, he had seen these rods at a supplier to the industry called “Atlas Copco”. In cross-examination, it was put to him that he must have been mistaken in this regard because Atlas Copco only sold the applicants’ products, and the applicants’ range did not include rods of this specification. In response to this, Mr Geatches enquired of counsel whether another company, called “Coromant” might have made these rods. Counsel’s response was that Coromant was owned by the applicants (or, I presume, one of them or a company in the same group). Mr Geatches’ answer to that was to say that, as he understood it, Coromant was not, in those days, a Sandvik company. And there the matter remained, until the final submissions made on behalf of the applicants, which contained the proposition, not developed orally, that Mr Geatches must have been mistaken in his understanding of when one of the applicants or a related company bought out Coromant because of what was to be found in two documents placed into the evidence for other purposes. The first was a “Sandvik Coromant” rock drilling tools catalogue produced in 1989. Because of the date of that catalogue, the name appearing on the cover cannot be regarded as inconsistent with Mr Geatches’ evidence that, in the mid-1980s or perhaps later, Coromant was not part of the Sandvik group. The second was an exhibit to one of the affidavits of Murray Clair, managing director of Nupress Tools Pty Ltd, and was described as “a set of technical drawings … provided to me by Phillips Ormonde Fitzpatrick Lawyers”. These drawings were provided to Mr Clair so that he might “comment on the threads shown in the drawings, including as to the nature of the thread, the relative ease of manufacture and whether I am aware of that thread having been used on products in the past, including mining products.” The corporate heading on the drawings was “Sandvik Coromant”, and the page to which my attention was drawn carried the date 17 February 1982. The difficulty here is that the assignment of that date to the occasion when this drawing was first done on a paper carrying that heading is not otherwise the subject of evidence. The court is being asked to make an inference, favourably to the party who tendered the document for an unrelated purpose and did not lead any evidence about the timing of the adoption of this corporate name, as a means of controverting the direct oral evidence of another witness. By the time of Mr Geatches’ cross-examination about this matter, Mr Clair had left the witness box. I do not suggest that it need have been otherwise, since the “Coromant” connection was raised only by Mr Geatches in response to questions from counsel for the applicants. But the problem for the court remains: there is no reliable evidence of when it was that one of the applicants or a related company acquired Coromant. Although the latter of these documents was put to Mr Geatches under cross-examination in connection with the purpose for which it was tendered (referred to in detail below), the significance of the corporate name and date shown on the header was not raised with him. The former document was not put to him at all.

68 In the circumstances, all I need to say is that Mr Geatches’ evidence was not undermined by this approach on the part of the applicants. He was quite firm in his recollection that he had found these small diameter right-hand rope-threaded rods; and he was convincing in the way he gave that evidence. It is, moreover, no more than part of the narrative apropos the development of the rods which are said to have anticipated the invention in suit. The real issue is whether he did build and use those rods, in relation to which the matter of Mr Geatches’ sighting of these small-diameter rods is tangential at best.

69 The third error is related to the second. It was said that Mr Geatches’ evidence about whether Colrok had used, or he had only “found”, such rods was “extremely confused”. To consider this submission, it is necessary to set out what Mr Geatches actually said on the subject. In his first affidavit, he said:

I tried to source suitable drill rods with right hand rope thread at that time, but was not able to do so from suppliers. I did find drill rods with right-hand rope thread available, but they were only 20 mm rods which were too small for driving the big rotary drill bits we needed to use for the installation of the cable bolts.

In his second affidavit, he said:

I do not have a clear recollection whether the right-hand rope-threaded rods that I found at the time (the mid-1980s) were 19 mm or 20 mm across the flats. To the best of my recollection, it was Atlas Copco who were offering these rods in right hand rope thread at the time. The rods had male connections at both ends.

At the time, we used these rods for advanced exploratory extension drilling of the dyke stone with hand held rotary percussive drills. The bore holes we made in the exploratory drilling were about 32 mm in size.

I did not regard the 19 mm or 20 mm rods to be suitable for drilling the larger (55 mm) holes we used for cable bolting. I considered them too small for attaching a 55 mm drill bit, and also too flexible to withstand the drilling thrust required to drill the larger size bore holes.

To this point, Mr Geatches had said nothing further than that he had found the 19 mm or 20 mm rods at Atlas Copco. He had not said that he had purchased any.

70 Under cross-examination on this aspect, counsel commenced by reiterating the effect of Mr Geatches’ affidavit evidence. Cross-examination continued as follows:

And you say you found them but they were too small?---Yes.

And you purchased them, you say, from Atlas Copco?---We purchased them .....

You found them but you didn’t acquire them?---Didn’t acquire them, no.

Okay. In the mid to late 1980s, what I want to put to you is that Atlas Copco didn’t offer 19 or 20 millimetre right-hand rope thread rods?---Well, it’s unfortunate a man called Ron Levitsch is not here because - - -

Well, I’m asking you what you know, Mr Geatches, not someone who’s not here?---All I know is that we did acquire rope thread rods from Atlas Copco - right-hand rope thread rods, either 20 or 19 mil, and I had used them. In fact, I probably had some at the workshop at the time.

Well, just pausing there, I thought you just told his Honour that you found them but you didn’t acquire any?---Well, I didn’t, no.

Be clear. You did not acquire any right-hand rope threaded rods?---No, I did not.

With respect to those involved, it does seem a bit rich, if I may put it that way, to accuse Mr Geatches of giving “extremely confused” evidence on this subject. The point of the cross-examination was to challenge his evidence-in-chief that he had found these rods at Atlas Copco. That was a perfectly legitimate project. It was counsel who first introduced the possibility that the rods might have been purchased and, for a moment, Mr Geatches went along with that. Some confusion undoubtedly followed. It was counsel himself who sought to clarify the position and, in my view, rightly so. Whether the rods had been acquired or only found was never the issue. Importantly, I could not, and do not, feel any heightened sense of disquiet as to the reliability of Mr Geatches’ evidence generally by reason of such minor confusion as appears from the extract from his cross-examination set out above.

71 The fourth error related to an adjustment which Mr Geatches made to the evidence to which he had sworn in his first affidavit when he came to swear his second. It concerns the matter covered in para 61 above. In his first affidavit, he swore as follows:

One of Colrok’s first uses of the male/female right hand rope thread drill rods made by [QMC] took place at Ellalong Colliery near Cessnock in the late 1980s. To the best of my recollection, this took place in about 1989.

In his second affidavit, Mr Geatches swore as follows:

Having reflected further, I cannot now recall with certainty that additional Geatches Rods were manufactured and supplied to [Colrok] by Quarry Mining. I believe it is likely that Quarry Mining supplied [Colrok] with additional Geatches Rods, because [Colrok] sourced various different rods from Quarry Mining at the time and I cannot now recall any other company who may have supplied additional Geatches Rods.

The difficulty which this submission on the part of the applicants presents is that the divergence between Mr Geatches’ two affidavits was not the subject of the cross-examination of him by their counsel. One of the consequences of litigation being framed around the sequential filing of affidavit evidence well in advance of trial is that the preparation of evidence-in-chief often lacks the focus associated with the immediacy of the hearing at which the evidence is to be presented. It is not unknown for a witness to swear a later affidavit which contains corrections to things previously said. By proceeding this way the witness does, of course, expose himself or herself to the criticism of inconsistency, and might well anticipate an uncomfortable time in the witness box. But it is another thing altogether for a party with interests opposed to those involved in calling the witness to allow the inconsistency to pass untested in cross-examination and then to submit that the witness’s evidence generally (ie not only in relation to the subject of the inconsistency) should be treated as less reliable because of the inconsistency. The witness ought at least to have had the opportunity to provide a benign explanation for it.

72 The fifth error was said to be Mr Geatches’ mistaken recollection that, at the Ellalong Colliery, Colrok’s air track machine was used only to drill 55 mm holes for cable bolts. That evidence was given under cross-examination, as was his related evidence that the drilling of holes of smaller diameter, and all single-pass drilling, was done with “hand-held bolters” (counsel’s term). It was submitted on behalf of the applicants that other evidence demonstrated that the air track machine had indeed been used for single-pass drilling and to drill 44 mm holes for the later insertion of polyurethane resin (“PUR”) for strata stabilisation (a form of extension drilling).

73 As to the former, the other evidence on which the applicants relied was given by two of the respondent’s witnesses who were concerned in the PUR process, Messrs Yates and Nielsen. I shall refer to their evidence, in a broader context, presently. The passage in the evidence of Mr Yates referred to in the applicants’ outline in their challenge to this aspect of Mr Geatches’ evidence had nothing to do with single-pass drilling. The passage in the evidence of Mr Nielsen did, but, although (as will become apparent) he took particular interest in the drill rods being used by Colrok at Ellalong, he did not in fact ever see a drilling operation being undertaken. Further, the evidence as to the use of the air track machine for single-pass drilling was led from him under cross-examination in way which suggested that counsel knew what he was talking about:

Now, at Ellalong Colrok was concerned with both single pass drilling and extension drilling, was it not?---Yes, it was.

And how many rigs did Colrok use?---At Ellalong?

Yes?---I only seen the one there.

And it was used, I take it, for both single pass drilling and extension drilling?---Correct.

The applicants were, of course, fully entitled to take that evidence at face value, but it would be another matter altogether to use it as an uncontroversial platform from which to challenge the accuracy of the evidence given, on the same subject, by Mr Geatches.