FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (No 2) [2016] FCA 168

TASMANIAN ABORIGINAL CENTRE INCORPORATED Applicant | |

AND: | SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT First Respondent DIRECTOR, PARKS AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The opening to recreational vehicles of tracks numbered 501, 503 and 601 in the Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape (WTACL) by the respondents pursuant to regulations 18 and 33 of the National Parks and Reserved Land Regulations 2009 (Tas), and the management of those tracks and the surrounding areas by:

(a) constructing new sections of track;

(b) spreading gravel;

(c) laying rubber matting; and

(d) installing culverts, fencing or track markers,

is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values, being indigenous heritage values, of the WTACL contrary to s 15B(4) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory injunction granted by Kerr J on 23 December 2014 be discharged.

2. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding, including any reserved costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MORTIMER J:

1 This proceeding concerns the proposed opening of three tracks to recreational vehicles in an area known as the Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape (WTACL). This area is a coastal strip of land approximately 2 kilometres wide located on the northern part of the west coast of Tasmania. It was designated as a “National Heritage place” on 7 February 2013 by a Ministerial declaration made under s 324JJ of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act).

2 Each of those tracks is also wholly located within the Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area (APCA), parts of which overlap with the WTACL. The APCA forms part of the Tarkine Wilderness Area and is a declared reserve under the Nature Conservation Act 2002 (Tas). The Tarkine is named after the Tarkinener, a community of Aboriginal people who were the traditional owners and inhabitants of the area around Sandy Cape. The Tarkine itself, a much larger area of 439,000 hectares, was listed on the National Estate Register on 24 September 2002, although this listing gives it no specific protection under the EPBC Act.

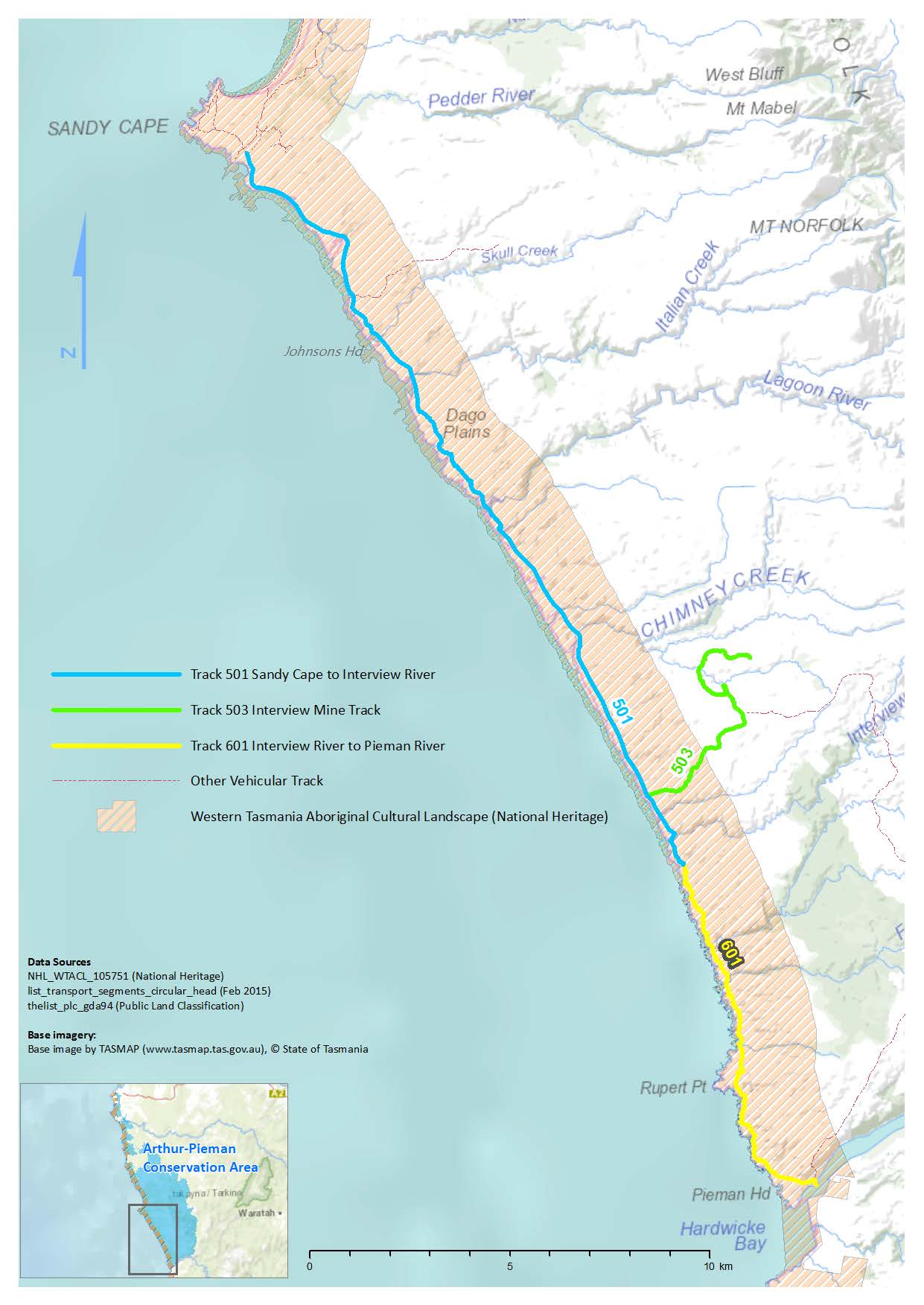

3 Tracks in the APCA are assigned numbers by the Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. The three tracks which are the subject of this proceeding are:

• part of track 501. Track 501 extends from Sandy Cape to the Interview River Track. The section in issue is a section from Sea Devil Rivulet to Interview River;

• track 503 – the Interview Mine Track;

• track 601 – the Interview River to Pieman River Track.

4 A map showing the three tracks and their location within the WTACL, the APCA and the Tarkine is Annexure A to these reasons for judgment.

5 The applicant submits, and the respondents do not contest, that track 503 may only be accessed via the part of track 501 which is proposed to be opened. Tracks 501 and 601 are accessible from areas to the north of the area in dispute.

6 There is no dispute that there are a number of known specific Aboriginal heritage sites on or in the immediate vicinity of tracks 501 and 601. Indeed, the presence of sites of significance to Aboriginal people, and the significance to the national heritage of Australia of the landscape of the WTACL as a whole, is why the area was declared under the EPBC Act, and it is also one of the reasons why the area forms part of the APCA.

7 The applicant, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated, seeks declaratory relief and injunctions under the EPBC Act restraining the respondents from engaging in conduct said to be associated with the proposed opening of the three tracks to recreational vehicles. No challenge to the applicant’s standing was made and I accept the applicant has standing under the Act to bring the application. The applicant contends the respondents’ conduct, in the opening and management of the tracks, will have a significant impact on the national heritage values protected by the 2013 Ministerial declaration.

8 At trial the office of the first and second respondents was occupied by the same natural person, Mr John Whittington, named in his different capacities as the Secretary of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and the Environment (the first respondent) and as the Director of the Parks and Wildlife Service (the second respondent). In his capacity as Secretary, Mr Whittington is responsible for the management of the Department, including the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service as a division of the Department. In his capacity as Director of Parks and Wildlife, Mr Whittington is the managing authority for the APCA under the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002 (Tas). Unless the context requires otherwise, I shall refer to Mr Whittington as “the respondents”.

9 The proceeding was defended by the respondents principally on two questions of statutory construction concerning the statutory concept of “action” in the EPBC Act. Their primary contention was that the respondents’ conduct was within the terms of s 524 of the Act and therefore not an “action” for the purposes of the Act at all. Their secondary contention was that the applicant had not identified any conduct which could be described as an “action” within the meaning of s 523 of the Act. In the alternative to those legal contentions, the respondents’ case was that if the tracks are opened and the protections provided by the EPBC Act otherwise apply, there will be no significant impact on the national heritage values protected by the declaration under the EPBC Act, because the values protected are not affected by the proposed action, and because of the safeguarding and protective measures which are intended to be put in place.

10 For the reasons that follow, I have found the applicant is entitled to relief.

The decision of Kerr J and the interlocutory injunction

11 This proceeding was commenced by way of an originating application dated 19 December 2014 and was listed urgently before Kerr J on 22 December 2014, because the materials filed with the application foreshadowed the possible imminent reopening of the three tracks: Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Inc v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment [2014] FCA 1443. His Honour granted an interlocutory injunction pending the trial and determination of the application. That injunction has remained in place until judgment.

12 On 23 February 2015 I made orders listing the matter for trial commencing on 31 August 2015 in Hobart for a period of five days. The applicant filed an amended statement of claim on 1 May 2015 and the respondents filed an amended defence on 28 May 2015. These amendments did not necessitate any change to the trial date. However, on 4 August 2015, just over a week before the applicant was due to file an outline of its submissions ahead of the trial, the respondents filed an interlocutory application seeking leave to file a further amended defence. The basis for the interlocutory application was what was described as a “pleading error”. The respondents had pleaded in several paragraphs of their amended defence that they did not admit certain allegations made by the applicant. Rule 16.07(2) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) provided that they would be taken to have admitted those allegations having not specifically denied them. This included certain allegations made by the applicant about the impact of the respondents’ action. The respondents contended they had not intended their pleading to have this consequence and sought to amend their pleading to express accurately which allegations they admitted and which they denied.

13 The applicant opposed the interlocutory application, but on 14 August 2015 I allowed it and gave short oral reasons for my decision. I also ordered that the respondents pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to the interlocutory application, costs thrown away by reason of the amendments, and costs of any further expert evidence responsive to the further amended defence. The respondents filed their further amended defence on 14 August 2015, necessitating the vacation of the 31 August 2015 trial date. A new timetable was set down for the filing of submissions and further evidence and the matter proceeded to trial over four days in Hobart commencing on 12 October 2015. The respondents accepted it was a consequence of their application to amend and the resultant delay that the injunction granted by Kerr J would continue for a longer period than might otherwise have been the case.

14 Prior to trial, the applicant filed an application pursuant to s 53 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) for a view to take place as part of this proceeding. The applicant proposed that the Court travel by helicopter from Hobart to the WTACL and APCA, accompanied by legal practitioners and persons nominated by each of the parties. The respondents did not oppose the proposal for a view. After some arrangements were confirmed, the application was granted, on the basis that my associate would prepare a note of the view to be settled and agreed between the parties, and which would then be admitted into evidence together with a detailed itinerary.

15 Accordingly, on 13 October 2015 the Court conducted a view at the WTACL and the APCA. The Court was accompanied by counsel and solicitors for both parties as well as persons nominated by both parties, including Mr Caleb Pedder, a witness for the applicant with archaeological expertise and who is familiar with the area viewed. No transcript was taken on the view, but Mr Pedder subsequently gave some oral evidence about the sites, tracks and landscapes the Court was shown during the view.

16 In accordance with my orders, a note was prepared of the sites shown to the Court (with GPS coordinates where appropriate), together with a schedule of photographs taken on the view, a detailed itinerary and maps of the area viewed. Those documents were all tendered by consent. The following description is taken from the note of the view as tendered.

17 The Court and the parties’ representatives and witnesses travelled from Hobart in a convoy of two helicopters landing at the mouth of the Interview River and then at Dago Plains, in both cases landing close to midden sites located near track 501. At those landing points, the Court was shown midden sites including a range of shellfish, bone fragments and stone artefacts, as well as what appeared to be vehicle tracks running close by or in some cases directly over the midden sites. En route to and from the landing points, the helicopters flew over tracks 601 and 503, including areas of track braiding where vehicles had deviated from the track, and a Parks and Wildlife sign at Sea Devil Rivulet indicating the point from which track 501 was closed.

18 The parties’ accepted, and it is the case that, in accordance with s 54 of the Evidence Act, I am able to draw any reasonable inference from what I have seen, heard or otherwise noticed during the view. Where I do so, I indicate my reliance on the view.

RELEVANT LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS AND LEGAL PRINCIPLES

The general legislative scheme and relevant concepts

19 The parts of the EPBC Act relevant in this proceeding operate on conduct identified by the term “action”. That term is central to the resolution of the issues in this proceeding, just as it is central to the regulatory scheme of the Act.

20 By a series of prohibitions, coupled with a permission regime as well as exclusions and exemptions to the prohibitions, the Act seeks first to prohibit and second to regulate conduct which has, or is likely to have, a “significant impact” on subject matter protected by the Act. The regulatory scheme includes civil penalty and criminal provisions, as well as remedial orders and injunctive relief.

21 The subject matter protected by the Act can be found in Part 3. The overarching description of that subject matter is “matters of national environmental significance”. Those matters are then divided into nine specific categories (Subdivisions A – FB), together with a category the content of which may be filled by regulatory prescription (see Subdivision G).

22 The protected subject matter includes matters falling under headings such as “World Heritage”, “National Heritage”, “Wetlands of international importance” and “Listed threatened species and communities”. The protections themselves are directed variously at persons, constitutional corporations, persons engaged in trade or commerce between Australia and another country or between Australian States and Territories, conduct occurring in Commonwealth areas, and conduct that is likely to have a significant impact on subject matter in respect of which Australia has obligations under international agreements including the Biodiversity Convention: see, eg, s 15B. As Kenny J explained in Secretary, Department of Sustainability and Environment (Vic) v Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (Cth) [2013] FCA 1299; 209 FCR 215 at [123]-[125], this structure is intended to ensure that the protections in the Act are supported by at least one, and preferably multiple, heads of power under the Constitution.

23 The structure of each of the subject matter prohibitions is substantially the same. I extract s 15B, which is the relevant prohibition, at [36] below. Between each of the nine specific categories, the subject matter protected varies widely and I return to the importance of identifying exactly what is protected at several points in these reasons.

24 The permission regime comprises a somewhat complex approvals process (see Chapter 4) and a series of exemptions from that approvals process (see Part 4). The prohibitions in respect of each protected subject matter will not operate if a Chapter 4 approval has been obtained and any conditions adhered to. Nor will they operate if one of the exemptions in Part 4 applies.

25 Conduct which contravenes these civil penalty or criminal provisions not only has the consequences for which those provisions provide, that conduct also becomes, by the operation of s 67 of the Act, a “controlled action”. This is reflected in a further general prohibition in the Act, found in s 67A:

A person must not take a controlled action unless an approval of the taking of the action by the person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of the relevant provision of Part 3.

Note: A person can be restrained from contravening this section by an injunction under section 475.

26 Thus, although the prohibitions may result in a civil penalty or in criminal liability, or in the grant of injunctions, another consequence of the successful invocation of one of the prohibitions in Part 3 may be that it will trigger an application for approval under Chapter 4. In other words, the taking of an impugned action may eventually occur, if approval is granted under Chapter 4, although there may be a variety of conditions imposed: see Part 9. Of course, a grant of approval is far from inevitable under the scheme and depends fundamentally on the assessment of the impact of a proposed action.

27 Each of the prohibitions in Part 3, and the controlled action prohibition in s 67A, provides a basis for the grant of injunctions under s 475, to which I now turn.

28 Under s 475 of the Act, this Court has the power to grant an injunction restraining conduct constituting an offence (for example, s 15C(8)) or a contravention (for example, s 15B(4) and s 67A) of the Act. Section 475 relevantly provides:

Applications for injunctions

(1) If a person has engaged, engages or proposes to engage in conduct consisting of an act or omission that constitutes an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations:

(a) the Minister; or

(b) an interested person (other than an unincorporated organisation); or

(c) a person acting on behalf of an unincorporated organisation that is an interested person;

may apply to the Federal Court for an injunction.

Prohibitory injunctions

(2) If a person has engaged, is engaging or is proposing to engage in conduct constituting an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations, the Court may grant an injunction restraining the person from engaging in the conduct.

Additional orders with prohibitory injunctions

(3) If the court grants an injunction restraining a person from engaging in conduct and in the Court’s opinion it is desirable to do so, the Court may make an order requiring the person to do something (including repair or mitigate damage to the environment).

…

29 The applicant initially sought final relief under s 475, although in light of the respondents’ concession, to which I refer at [299] below, it accepts that declaratory relief would be sufficient.

30 As I have noted, the statutory concept of “action” in the Act is critical to the determination of this proceeding, and to the reach of the Act. The word is not defined in the Act. Section 523 sets out five kinds of conduct which the Act expressly includes in the statutory concept:

(1) Subject to this Subdivision, action includes:

(a) a project; and

(b) a development; and

(c) an undertaking; and

(d) an activity or series of activities; and

(e) an alteration of any of the things mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d).

31 Section 524, on which the respondents rely in this proceeding, then provides that certain things are excluded from the concept of “action”:

(1) This section applies to a decision by each of the following kinds of person (government body):

(a) the Commonwealth;

(b) a Commonwealth agency;

(c) a State;

(d) a self-governing Territory;

(e) an agency of a State or self-governing Territory;

(f) an authority established by a law applying in a Territory that is not a self-governing Territory.

(2) A decision by a government body to grant a governmental authorisation (however described) for another person to take an action is not an action.

(3) To avoid doubt, a decision by the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency to grant a governmental authorisation under one of the following Acts is not an action:

(a) the Customs Act 1901;

(b) the Export Control Act 1982;

(c) the Export Finance and Insurance Corporation Act 1991;

(d) the Fisheries Management Act 1991;

(e) the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975;

(f) the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006;

(g) the Quarantine Act 1908;

(h) the Competition and Consumer Act 2010.

This subsection does not limit this section.

32 By crafting an exclusion around a decision of a particular kind, the scheme contemplates, it would seem to me, that a decision may otherwise be within the statutory concept of action. However, not all decisions will be actions, as the Full Court made clear in Esposito v Commonwealth [2015] FCAFC 160 at [97]-[110]. In that case, the Court held that neither a rezoning decision nor the enactment of the legislation on which it was based were an “action” for the purposes of s 523 of the Act. At [103] the Court held:

Returning then to s 523 of the EPBC Act, we do not accept, and it was not suggested that we should, that an exercise of State legislative power which does not relate to any development in particular and which merely empowers a Council to grant its approval to future developments thereby engaging s 76A can be described as a project, development, undertaking or activity or series of activities within the meaning of s 523. Nor, should we say for completeness, do we accept that the Council’s role as a ‘consent authority’, or its obligation to prepare a draft planning instrument for the Minister, leads to any different outcome.

33 The final critical statutory concept in the Act, insofar as the contested issues in this proceeding are concerned, is the concept of “impact”. It is the subject of an almost impenetrable definition in s 527E:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an event or circumstance is an impact of an action taken by a person if:

(a) the event or circumstance is a direct consequence of the action; or

(b) for an event or circumstance that is an indirect consequence of the action—subject to subsection (2), the action is a substantial cause of that event or circumstance.

(2) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(b), if:

(a) a person (the primary person) takes an action (the primary action); and

(b) as a consequence of the primary action, another person (the secondary person) takes another action (the secondary action); and

(c) the secondary action is not taken at the direction or request of the primary person; and

(d) an event or circumstance is a consequence of the secondary action;

then that event or circumstance is an impact of the primary action only if:

(e) the primary action facilitates, to a major extent, the secondary action; and

(f) the secondary action is:

(i) within the contemplation of the primary person; or

(ii) a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the primary action; and

(g) the event or circumstance is:

(i) within the contemplation of the primary person; or

(ii) a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the secondary action.

34 Even if there is an “impact”, for the prohibitions to operate it must be a significant impact. The adjective “significant” is not defined, but there is an established understanding in the authorities of the threshold that adjective imposes. I set out those authorities at [240] below.

The protection of “National Heritage places”

35 The categories of matters of national environmental significance have expanded since the enactment of the EPBC Act in 1999. The subject matter of this proceeding is an example. The category of “National Heritage place” was added to the Act by the Environment and Heritage Legislation Amendment Act (No. 1) 2003 (Cth). In his second reading speech, the Minister for the Environment and Heritage stated:

The National Heritage List creates opportunities to remember, celebrate and conserve places that recall significant themes in Australian history. We should respect and value the development of our industries by recognising and protecting early mining, industrial and pastoral sites. Our national historic built heritage includes places that give an insight into the development of our own sense of Australian identity and our sense of place and, as such, should be recognised and protected for their national heritage significance. Natural heritage places that may be considered by the Australian Heritage Council include those that tell the story of our continent’s natural diversity and ancient past.

The bill moves forward in the protection of the heritage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous cultural heritage exists throughout Australia and all aspects of the landscape may be important to Indigenous people as part of their heritage. The effective protection and conservation of this heritage is important in maintaining the identity, health and wellbeing of Indigenous people. This bill provides new opportunities for developing agreed strategies to protect Indigenous heritage places after consultation and discussion with traditional owners on management arrangements. The rights and interests of Indigenous people in their heritage arise from their spirituality, customary law, original ownership, custodianship, developing Indigenous traditions and recent history.

36 The relevant prohibitions are contained in s 15B of the Act, which provides:

15B Requirement for approval of activities with a significant impact on a National Heritage place

(1) A constitutional corporation, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency must not take an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage place.

Civil Penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(2) A person must not, for the purposes of trade or commerce:

(a) between Australia and another country; or

(b) between 2 States; or

(c) between a State and Territory; or

(d) between 2 Territories;

take an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage place.

Civil Penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(3) A person must not take an action in:

(a) a Commonwealth area; or

(b) a Territory; that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage place.

Civil Penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(4) A person must not take an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values, to the extent that they are indigenous heritage values, of a National Heritage place.

Civil Penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Note: For indigenous heritage value, see section 528.

(5) A person must not take an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage place in an area in respect of which Australia has obligations under Article 8 of the Biodiversity Convention.

Civil Penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(6) Subsection (5) only applies to actions whose prohibition is appropriate and adapted to give effect to Australia’s obligations under Article 8 of the Biodiversity Convention. (However, that subsection may not apply to certain actions because of subsection (8).)

(8) Subsections (1) to (5) (inclusive) do not apply to an action if:

(a) an approval of the taking of the action by the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth agency, Commonwealth or person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(b) Part 4 lets the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth agency, Commonwealth or person take the action without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(c) there is in force a decision of the Minister under Division 2 of Part 7 that this section is not a controlling provision for the action and, if the decision was made because the Minister believed the action would be taken in a manner specified in the notice of the decision under section 77, the action is taken in that manner; or

(d) the action is an action described in subsection 160(2) (which describes actions whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process).

37 Although a National Heritage “place” appears, at first impression, to be the subject matter of the Act’s protection, taking into account the text of other provisions and reading s 15B as a whole, it is apparent what is being protected is not simply a “place”, but the “values” of that place which warranted the place’s inclusion on the National Heritage List. That this is so should also be apparent from the use of the term “heritage”, which is a term directing attention to, again, what a “place” stand for, signifies or embodies. Part of the “heritage” of a place may relate to historical events, to activities undertaken by people in a place but it can also involve ideas, aspirations, beliefs and practices. The broader subject matter protected is also apparent from the terms of s 324C, which I set out below: a “place” can, under this legislative scheme, only become a National Heritage place if, in the responsible Minister’s opinion, it embodies particular “values”.

38 A “National Heritage place” is a place recorded in the National Heritage List, in accordance with the process set out in Part 15 of the Act. Section 324C describes the National Heritage List. It provides:

(1) The Minister must keep a written record of places and their heritage values in accordance with this Subdivision and Subdivisions BA, BB and BC. The record is called the National Heritage List.

(2) A place may be included in the National Heritage List only if:

(a) the place is within the Australian jurisdiction; and

(b) the Minister is satisfied that the place has one or more National Heritage values (subject to the provisions in Subdivision BB about the emergency process).

(3) A place that is included in the National Heritage List is called a National Heritage place.

(4) The National Heritage List is not a legislative instrument.

39 What can constitute a “place” for the purposes of this subject matter protection is dealt with, inclusively rather than exhaustively, by the definition of “place” in s 528. “Place” includes:

(a) a location, area or region or a number of locations, areas or regions; and

(b) a building or other structure, or group of buildings or other structures (which may include equipment, furniture, fittings and articles associated or connected with the building or structure, or group of buildings or structures); and

(c) in relation to the protection, maintenance, preservation or improvement of a place—the immediate surroundings of a thing in paragraph (a) or (b).

40 The inclusion of a place on the National Heritage List is a function conferred on the responsible Minister pursuant to s 324JJ of the Act. There is a process set out in Subdivision BA of Div 1A of Part 15 which leads up to this determination. Places may be nominated and nominations are given to the Australian Heritage Council (see ss 324J and 324JA). The Council then provides the Minster with a list of places it considers should be assessed (see ss 324JB, 324JC and 325JD). After other steps not presently relevant, the Council then provides a written assessment of the places on the finalised list and gives those assessments to the Minster (see ss 324JH and 324JI). The Council’s assessment is made against specified “National Heritage criteria”, which I set out at [42] below.

41 The Minister then determines, pursuant to s 324JJ, whether or not an assessed place will be included on the National Heritage List. The determination turns on the Minister’s satisfaction that the place has one or more National Heritage values, the content of those values being those set out in s 324D, read with the applicable regulations, to which I return below. In forming her or his satisfaction, the Minister is required to have regard to the Council’s assessment and any public comments (see s 324JJ(5)). Since it is central to this proceeding, I set out the whole of s 324JJ:

Minister to decide whether or not to include place

(1) After receiving from the Australian Heritage Council an assessment under section 324JH whether a place (the assessed place) meets any of the National Heritage criteria, the Minister must:

(a) by instrument published in the Gazette, include in the National Heritage List:

(i) the assessed place or a part of the assessed place; and

(ii) the National Heritage values of the assessed place, or that part of the assessed place, that are specified in the instrument; or

(b) in writing, decide not to include the assessed place in the National Heritage List.

Note: The Minister may include a place in the National Heritage List only if the Minister is satisfied that the place has one or more National Heritage values (see subsection 324C(2)).

(2) Subject to subsection (3), the Minister must comply with subsection (1) within 90 business days after the day on which the Minister receives the assessment.

(3) The Minister may, in writing, extend or further extend the period for complying with subsection (1).

(4) Particulars of an extension or further extension under subsection (3) must be published on the internet and in any other way required by the regulations.

(5) For the purpose of deciding what action to take under subsection (1) in relation to the assessed place:

(a) the Minister must have regard to:

(i) the Australian Heritage Council’s assessment whether the assessed place meets any of the National Heritage criteria; and

(ii) the comments (if any), a copy of which were given to the Minister under subsection 324JH(1) with the assessment; and

(b) the Minister may seek, and have regard to, information or advice from any source.

Additional requirements if Minister decides to include place

(6) If the Minister includes the assessed place, or a part of the assessed place (the listed part of the assessed place), in the National Heritage List, he or she must, within a reasonable time:

(a) take all practicable steps to:

(i) identify each person who is an owner or occupier of all or part of the assessed place; and

(ii) advise each person identified that the assessed place, or the listed part of the assessed place, has been included in the National Heritage List; and

(b) if the assessed place:

(i) was nominated; or

(ii) was included in a place that was nominated; or

(iii) includes a place that was nominated;

by a person in response to a notice under subsection 324J(1)—advise the person that the assessed place, or the listed part of the assessed place, has been included in the National Heritage List; and

(c) publish a copy of the instrument referred to in paragraph (1)(a) on the internet; and

(d) publish a copy or summary of that instrument in accordance with any other requirements specified in the regulations.

(7) If the Minister is satisfied that there are likely to be at least 50 persons referred to in subparagraph (6)(a)(i), the Minister may satisfy the requirements of paragraph (6)(a) in relation to those persons by including the advice referred to in that paragraph in one or more of the following:

(a) advertisements in a newspaper, or newspapers, circulating in the area in which the assessed place is located;

(b) letters addressed to “The owner or occupier” and left at all the premises that are wholly or partly within the assessed place;

(c) displays in public buildings at or near the assessed place.

Additional requirements if Minister decides not to include place

(8) If the Minister decides not to include the assessed place in the National Heritage List, the Minister must, within 10 business days after making the decision:

(a) publish the decision on the internet; and

(b) if the assessed place:

(i) was nominated; or

(ii) was included in a place that was nominated; or

(iii) includes a place that was nominated;

by a person in response to a notice under subsection 324J(1)—advise the person of the decision, and of the reasons for the decision.

Note: Subsection (8) applies in a case where the Minister decides that none of the assessed place is to be included in the National Heritage List.

42 Section 324D specifies what needs to exist for a place to have a “National Heritage value”. It should be noted that as between the specified “value” and the relevant criterion, or criteria, sub-section (1) contemplates some kind of causal relationship. It should also be noted that the scheme requires the particular value or values identified for a place to be specified in the entry in the National Heritage List for that place. It is this specification, or inclusion, which in my opinion controls the assessment of significant impact for the purposes of s 15B(4). Section 324D provides:

(1) A place has a National Heritage value if and only if the place meets one of the criteria (the National Heritage criteria) prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this section. The National Heritage value of the place is the place’s heritage value that causes the place to meet the criterion.

(2) The National Heritage values of a National Heritage place are the National Heritage values of the place included in the National Heritage List for the place.

(3) The regulations must prescribe criteria for the following:

(a) natural heritage values of places;

(b) indigenous heritage values of places;

(c) historic heritage values of places.

The regulations may prescribe criteria for other heritage values of places.

(4) To avoid doubt, a criterion prescribed by the regulations may relate to one or more of the following:

(a) natural heritage values of places;

(b) indigenous heritage values of places;

(c) historic heritage values of places;

(d) other heritage values of places.

43 Thus, three specific kinds of heritage values are contemplated as relevant for protection of a place: natural, indigenous and historic. A further more open “other” category exists, although its existence and use is more discretionary, as the differences between “must” and “may” in s 324D(3) indicate.

44 The term “heritage value” is in turn defined under s 528:

heritage value of a place includes the place’s natural and cultural environment having aesthetic, historic, scientific or social significance, or other significance, for current and future generations of Australians.

45 The term “indigenous heritage value” is given a particular meaning. Section 528 defines “indigenous heritage value” as follows:

indigenous heritage value of a place means a heritage value of the place that is of significance to indigenous persons in accordance with their practices, observances, customs, traditions, beliefs or history.

46 It can be seen that while s 324D uses the plural “values”, the two definitions use the singular “value”. No party submitted that anything turned on the difference and I agree with the parties’ approach.

47 The fact that each of the statutory terms “heritage values” and “indigenous heritage values” are both defined could lead, in their use and application, to some circularity and confusion. Construed in context, it seems to me that the latter being a more specific defined term than the former, its statutory definition should be applied as it is expressed, without an overlay of the more general defined term “heritage value”. Accordingly, I consider (for reasons more fully set out below) that it is the “indigenous heritage values” of the WTACL which control the assessment of significant impact, for the purpose of the actions as alleged by the applicant.

48 The current criteria for a Ministerial declaration are set out at reg 10.01A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth). Discerning a rational and clear construction and operation of this regulation is not easy. Regulation 10.01A provides:

(1) For section 324D of the Act, subregulation (2) prescribes the National Heritage criteria for the following:

(a) natural heritage values of places;

(b) indigenous heritage values of places;

(c) historic heritage values of places.

(2) The National Heritage criteria for a place are any or all of the following:

(a) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

(b) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

(c) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

(d) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of:

(i) a class of Australia’s natural or cultural places; or

(ii) a class of Australia’s natural or cultural environments;

(e) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics valued by a community or cultural group;

(f) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period;

(g) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons;

(h) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Australia’s natural or cultural history;

(i) the place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance as part of indigenous tradition.

(3) For subregulation (2), the cultural aspect of a criterion means the indigenous cultural aspect, the non-indigenous cultural aspect, or both.

49 It is apparent that sub-reg 10.01A(2) does not expressly link each criterion with one, or more than one, of the three national heritage values listed in paragraph (1). Thus, each criterion might, depending on the place concerned, operate against more than one value, or against different values for different places. Thus, criterion 2(c) – the place’s potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia’s natural or cultural history – might be used to identify a place’s historic value, or indigenous value. Even criterion 2(i) could, in my opinion, lead to a place being identified as having historic value, not only indigenous value although the latter might occur more often.

50 There is also nothing in the way the scheme is structured to prevent the Minister identifying a place as having (for example) both historic and indigenous values; or natural and indigenous values, to take but two possible combinations.

51 In this case, as I set out in more detail below, the WTACL was found by the Minister to meet the first criterion of sub-reg 10.01A(2) – sub-reg (a). That is: “outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place’s importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history”. This is what the Minister specified in the left hand column of his declaration (see Gazette Notice S 24 of 2013, Schedule, 4).

52 However, in the right hand column of the declaration is the second part of the exercise under this aspect of the legislative scheme. This is the part where the Minister must make the causal link between the characteristic of this area as a place of outstanding heritage value to the nation because of its importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history on the one hand, and one or more of the three values set out in s 324D(3) on the other. The obligation to do so arises from the terms of s 324JJ(1)(a)(ii).

53 Here, the Minister chose to identify indigenous heritage values as the causal link. How that choice is revealed by the evidence requires a little explanation. The conclusion derives from reading, together, the Ministerial declaration and the Briefing Note to the Minister, which were in evidence before me. The declaration itself states that the Minister is satisfied the WTACL “has the National Heritage values” specified in the Schedule. In the Schedule, in the right hand column under the heading “Value” is a three paragraph statement which I have reproduced at [95] in these reasons. That description is wholly concerned with the importance of the WTACL as an expression of the way of life of the Aboriginal people who inhabited the area for the last several thousand years, but it does not expressly employ the statutory term “indigenous heritage values”. However, on the decision page of the Ministerial Briefing Note, the Minister was given five options in terms of specifying the values for which the WTACL (only, the Minister decided) should be listed. The Minister circled that he “Agreed” to “Aboriginal Values”, and the map attached to the Briefing Note shows a hatched area co-extensive with the WTACL, which in the legend on the map is described as “Aboriginal values”.

54 That is, it is the indigenous heritage values of the WTACL which in the Minister’s opinion cause it to have importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history. That is, applying the definition of indigenous heritage values as I have set out at [45] above, the Minister determined that the cause (or reason) for the WTACL having the importance it does is its significance to indigenous persons in accordance with their practices, observances, customs, traditions, beliefs or history. The submissions of both the applicant and the respondents were premised on an acceptance that this was the choice made by the Minister.

THE IMPUGNED ACTION AND THE RESPONDENTS’ CASE

55 The applicant impugns both on a collective and an individual basis three interrelated phases of what it says is conduct proposed to be undertaken by the respondents. Those phases are described in the applicant’s outline of submissions:

(a) designation of parts of the APCA in accordance with regulations 18 and 33 of the National Parks and Reserved Land Regulations (Tas) 2009 to remove the prohibition on recreational vehicles being driven on the tracks, subject to certain conditions (Designation Phase);

(b) works in and around the tracks such as spreading gravel, placing rubber matting over Aboriginal cultural heritage sites and constructing new sections of track (Works Phase);

(c) selling permits to individual drivers to drive on the tracks, collecting fees, attaching and removing GPS devices for recreational vehicles, collecting and refunding bonds (Operating Phase).

56 Those phases are set out (in slightly different order) at paragraph 7 of the applicant’s amended statement of claim, where the proposed conduct is described:

The Respondents have engaged in, or propose to engage in conduct, namely:

a. the Second Respondent, as managing authority of the APCA, designating parts of the APCA as a “designated vehicle area” in accordance with Regulations 18 and 33 of the National Parks and Reserved Land Regulations 2009 (Tas).

i. Such designation will provide for recreational vehicles to be driven on the tracks and/or any newly constructed tracks or sections of track in the WTACL;

ii. Conditions attached to the designation include:

1. a fee being levied on each driver;

2. each driver attaching a GPS device to their vehicle; and

3. a Recreational Driver - Special Pass being issued to each driver.

b. carrying out actions to implement conditions attached to the designation in relation to individual drivers by:

i. offering to the public for purchase a Recreational Driver - Special Pass for the Pieman River Track (south of Sea Devil Rivulet to the Pieman River) and Interview Mine Track;

ii. collecting $50 per driver for each pass sold;

iii. ensuring a GPS device is fitted to the vehicle to be driven by each person who purchases a Recreational Driver – Special Pass;

iv. collecting a $100 bond for the GPS device from the person who purchases a Recreational Driver – Special Vehicle Pass;

v. removing the GPS device form the vehicle;

vi. refunding the bond to the person who purchased the Recreational Driver – Special Pass.

c. carrying out, or directing their employees, officers, agents or representatives to carry out works in the WTACL in and around the tracks for the purposes of facilitating recreational vehicles to be driven on the tracks by:

i. constructing new sections of track;

ii. spreading gravel over Aboriginal cultural heritage; and/or

iii. placing rubber matting over Aboriginal cultural heritage with star pickets or other means of fastening the rubber matting in place;

iv. installing culverts, fencing or track markers;

v. carrying out rehabilitation works; and/or

vi. other works as directed by the Respondents.

57 The applicant impugns the whole of that proposed conduct, on the basis that collectively these phases constitute a project or a series of activities within the meaning of s 523, and is therefore a single “action” under the Act. Further, the applicant also separately impugns each of the designation (with its conditions), the works phase and the operating phase as constituting individually an “action” under the Act.

58 The applicant then contends that whether considered individually or collectively, the proposed action will have a significant impact on the indigenous values of the WTACL.

59 The respondents contend that the applicant’s case fails in respect of each element required under s 15B(4), being the requirements that there be an “action”, that there be an impact on National Heritage values in so far as they are indigenous heritage values, and that the impact be significant.

60 The parties worked cooperatively prior to trial to agree as much of the factual basis for the proceeding as possible, and an agreed statement of facts was admitted into evidence pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act. No evidence was filed on behalf of the respondents. The absence of any evidence from the respondents, and limited cross examination of the applicant’s witnesses, meant that most of the factual foundation for the applicant’s claims was not the subject of positive challenge.

61 The applicant called a number of witnesses, both expert and lay. Each lay witness had given evidence by way of affidavit, and there were reports filed by the expert witnesses.

62 Objection was taken to the affidavits and reports of two witnesses from whom the applicant proposed to lead expert evidence: namely, Mr Henry Turnbull and Dr Susan McIntyre-Tamwoy. Mr Turnbull’s report related to the physical consequences of vehicles driving in the relevant areas, while Dr McIntyre-Tamwoy’s report related to methodologies for assessing the impact of a proposal on indigenous heritage values.

63 The basis for both objections was twofold. First, that the reports failed to identify or assumed the facts upon which the opinions in them were based and second, that the reports were not based on specialised knowledge. I ruled that the expert evidence proposed to be given by each of Mr Turnbull and Dr McIntyre-Tamwoy was inadmissible. In the case of Mr Turnbull, I was not satisfied that he had the necessary specialised knowledge to express opinions concerning the construction of bypass tracks or the physical consequences of driving recreational vehicles in the relevant areas. In the case of Dr McIntyre-Tamwoy, while I accepted that she had the expertise set out in her report, I was not satisfied that her opinions on the assessment of heritage significance for the purposes of management and administrative decision-making was relevant to the issues in the proceeding.

Applicant’s witnesses not called for cross-examination

64 Mr Mansell is Chair of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania and a member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. He gave evidence, in his personal capacity, regarding a visit he made to the WTACL and the importance of the area to Aboriginal people in Tasmania.

65 Mr Hughes worked as an Aboriginal Heritage Officer at the Tasmanian Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (TALSC) for more than 20 years. He is also member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community and gave evidence regarding the cultural value of the WTACL to his community, as well as the various trips he has taken to the area.

66 Mr Edwards is employed by the applicant as a land management supervisor and is a member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. His evidence focused on his personal and cultural connection with the WTACL and surrounding areas, which was originally established during trips to the area with his family when Mr Edwards was a child.

67 Mr Mansell is a member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community and gave evidence regarding a visit he made to the WTACL and surrounding areas in 2013, including his observations regarding the importance of the area as a source of knowledge about the Aboriginal people who lived in the area over many generations.

68 Mr Sainty is a member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community and Deputy Regional Director of the Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet in Hobart, as well as Chair of the Interim Aboriginal Heritage Council. He previously worked as a ranger and spent time in the APCA and the area that is now the WTACL. Mr Sainty gave evidence regarding the cultural and historical connections that the artefacts and environment in the WTACL provide to him and other Aboriginal people in Tasmania.

69 Ms Sainty is a Senior Project Officer, Culture and Curriculum at the Tasmanian Department of Education. She also works as a consultant in respect of Aboriginal languages and is a member of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. She and Mr Rocky Sainty are married. She gave evidence regarding the cultural value of the WTACL to her and other Aboriginal people, and the impact of opening the area to vehicles on that value.

70 Mr Harwin holds tertiary qualifications in surveying and has conducted research into GPS and other techniques for fine-scale mapping. He filed an expert report on behalf of the applicant regarding the accuracy of GPS data that would be used to monitor vehicles in the WTACL if the respondents were to open the area to recreational drivers.

Applicant’s witnesses who gave oral evidence

71 Ms Sculthorpe is the Chief Executive Officer of the applicant. Ms Sculthorpe affirmed an affidavit in the proceeding on 19 December 2014. Ms Sculthorpe’s evidence related to the history and objectives of the applicant, the Tasmanian Government’s proposal to open the WTACL to off-road vehicles, and the applicant’s response to that proposal.

72 I found Ms Sculthorpe to be a careful witness. Although she did not appear to me to have a detailed personal knowledge of the WTACL, based on her previous experience in dealing with Aboriginal heritage issues in Tasmania she did have clear ideas about what might be necessary for harm minimisation, and how effective that might be.

73 Mr Thompson is employed as an education worker at the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre. He identifies as Aboriginal. Mr Thompson filed two affidavits in the proceeding, the first sworn on 19 December 2014 and the second sworn on 11 June 2014. Mr Thompson’s first affidavit was filed in support of the applicant’s application for an interim injunction. It describes a visit he made to the APCA during which he spoke to Parks and Wildlife staff about how the area was to be managed. It was Mr Thompson’s evidence that he observed the impact of four wheel drive tracks in the reserve. Annexed to Mr Thompson’s affidavit are photographs that were taken at that time. Mr Thompson’s second affidavit identifies the WTACL and surrounding areas as important to him, his identity and his heritage.

74 Mr Thompson’s evidence was given in an informal way, but I found him a reliable witness, although his evidence often lacked detail. The main relevance of his evidence to the contentious issues in this case were the conversations he described having with officers of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, concerning the reopening of the three tracks.

75 Mr Huys has 22 years’ experience as a consultant archaeologist and is the Director of CHMA Pty Ltd, a company that specialises in the assessment and management of Aboriginal and historic heritage. Mr Huys has considerable experience in conducting Aboriginal heritage assessments in Tasmania. The applicant tendered without objection an expert report of Mr Huys dated 26 May 2015. In his expert report, Mr Huys relied on a 2010 report prepared by CMHA Pty Ltd after being engaged by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service to undertake an Aboriginal heritage assessment and develop an Aboriginal Heritage Management Plan for identified vehicle tracks within the APCA. Mr Huys was the principal archaeologist on the project. The 2010 report included but was not limited to surveys of tracks 501 and 601. Track 503 was not part of the 2010 report. The 2010 report collated the findings of the surveys undertaken by CHMA Pty Ltd and identified cultural sites on tracks 601 and 501.

76 Mr Huys was an impressive witness, both in terms of his experience and command of relevant material and in terms of his preparedness to place reasonable limits on what he could say.

77 Dr Stone is an archaeologist and geomorphologist. Dr Stone appeared via video link from Sydney on the second day of the hearing. The applicant tendered an expert report of Dr Stone dated 12 June 2015. Dr Stone’s expert evidence related to the impact of driving vehicles in dunes and dune fields, middens and other Aboriginal heritage sites.

78 Dr Stone was a careful and reliable witness. Although he has not actually been to the WTACL, his depth of experience as an archaeologist specialising in the management of Aboriginal cultural heritage led to what I accept was justified confidence in the opinions he expressed about the presence, and importance, of middens and other Aboriginal heritage in the relevant areas and the impact of the respondents’ proposed conduct.

79 Professor Ryan is a Research Professor at the Centre for the History of Violence at the University of Newcastle, Australia. In 1976, Ms Ryan completed a PhD on the history of Tasmanian Aborigines and has since become a world authority on the subject.

80 The applicant tendered an expert report of Professor Ryan filed in the proceeding on 12 June 2015. Dr Ryan’s evidence included information on the history of European colonisation in Tasmania and the impact on Tasmanian Aborigines. Dr Ryan’s evidence also addressed the significance of sites and landscapes containing evidence of Tasmanian Aboriginal life prior to colonisation, including the area between the Pieman River and Sandy Cape.

81 Professor Ryan was obviously well-qualified and experienced. She was in charge of her material and gave careful answers. Her evidence was almost entirely dependent on G.A. Robinson’s diaries, which is unsurprising since there are so few written historical sources concerning European observations of Aboriginal people living in the APCA. I explain at [90] and [146] below who G.A. Robinson was, and why his travels in the APCA came to feature in the evidence given in this proceeding.

82 Despite her obvious expertise and knowledge, I do not consider Professor Ryan’s opinions to be of much relevance to the issues the Court must determine in this case. I understood the purpose of her evidence was to rebut the reliance the respondents asked the Court to place on the diaries of G.A. Robinson, in terms of making findings about where hut depressions and seal hides were located within the WTACL. For reasons which I explain in more detail below, that approach involves a misunderstanding of the task of assessing whether there is a likely contravention of s 15B(4), because it focuses on particular and isolated surviving manifestations of the way of life of Aboriginal people in the entire landscape which is the WTACL.

83 Mr Pedder swore two affidavits in the proceeding, the first on 10 June 2015 and the second on 15 October 2015. Mr Pedder is member of the Aboriginal community and has worked in the cultural heritage field for many years, including as manager of TALSC and in the Indigenous Heritage Section of the Commonwealth Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

84 Mr Pedder was a sincere, honest and helpful witness. His opinions were genuinely held and felt, and he was not given to exaggeration, but his views about the protection of Aboriginal heritage are strong. He is entitled to them given his experience, and to the extent they are relevant to the matters I must determine, I have relied on them.

85 In the following part of my reasons, I set out the factual findings I make about the WTACL, the proposal to open the tracks, the proposed mitigation and protective measures and their likely effectiveness, and the evidence about the nature and extent of Aboriginal sites in the WTACL and its surrounds – the latter issue arising because of the emphasis the respondents submit is to be placed on where hut depression sites, as opposed to middens, occur in the WTACL.

The regime for the protection of indigenous values and heritage in the area

86 The Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area comprises some 100,135 hectares in the north-west of Tasmania. The APCA was initially established as the Arthur-Pieman Protected Area under the Crown Lands Act 1976 (Tas) in 1982 and declared a conservation area (a type of reserved land) on 30 April 1999 under the Nature Conservation Act 2002 (Tas).

87 The part of the APCA relevant to this proceeding is located along the coast between Sandy Cape and Pieman River, as shown in the map at Annexure A to this judgment.

88 The APCA is managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service under the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002 (Tas), which sets out the management objectives for the APCA. In January 2002, the Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area Management Plan 2002 (prepared pursuant to Pt IV of the predecessor National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970 (Tas)) took effect, and that Plan is in evidence before me. In accordance with s 23 of the then National Parks and Wildlife Act and its current equivalent s 30 of the National Parks and Reserves Management Act, the respondents (holding office as the managing authority for the reserve) are required to manage the APCA for the purpose of giving effect to the Plan.

89 The summary part of the Plan relevantly records that:

The reserve provides protection to an extraordinary richness of Aboriginal cultural heritage, to highly significant and diverse ecosystems, and to spectacular coastal landscapes and wilderness values.

The conservation area has been described as ‘... one of the world’s great archaeological regions’ (Richards & Richards in Harries 1992) on account of its Aboriginal heritage values.

…

The reserve will be managed to protect values, while providing for a range of activities. The major management initiatives for the reserve are summarised below.

• Far greater emphasis will be placed upon careful management and interpretation of the reserve’s Aboriginal heritage values.

…

• The use of off-road recreation vehicles in the reserve will continue, but with careful regulation and emphasis on the education of users about low impact use.

…

90 Section 3.5 of the Plan sets out the Aboriginal values of the Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area. It states:

European knowledge of human history in the Arthur–Pieman area, prior to contact, is restricted to a combination of historical records and archaeological investigation of the sites created by thousands of years of Aboriginal occupation and use. There is now evidence which shows that Aboriginal people have lived in Tasmania continuously from at least 37,000 years ago, spanning at least the last two ice-ages.

Jones (1974) describes a North-West Tribe that occupied the coast between Table Cape and Cape Grim and down the west coast to Macquarie Harbour. The Tribe comprised nine or ten bands, with three of those bands the Peerapper, the Manegin and Tarkinener occupying sections of the coast in the Arthur– Pieman region (Ryan 1996). The people comprising the bands were semisedentary, living for long periods of the year in semi-permanent coastal settlements, but moving seasonally to exploit a large range of coastal and inland resources (Collett et al. 1998). Both archaeological surveys and ethnographic evidence suggest that the local Aboriginal populations were numerous. In addition the groups of huts observed by Robinson (Plomley 1966) at West Point and elsewhere show that several ‘villages’ of a dozen or so huts existed in the area. The conservation area can be considered an Aboriginal landscape where no doubt many of the landforms and plant communities were altered, managed and maintained through past Aboriginal land management practices.

Post-contact, competition for resources very quickly brought the North-West Tribe and white invaders into direct conflict. The first conflicts were with sealers, and then with pastoral interests, chiefly the Van Diemens Land Company. Aboriginal deaths and massacres were reported. G.A. Robinson, acting on behalf of the colonial administration, first as a ‘conciliator’ then as a ‘captor’ (Ryan 1996) made several visits to the Arthur-Pieman between 1830 and 1834. During his last visit in 1834, Robinson removed the last officially recognised Aborigines of the North-West Tribe from their traditional land. According to Ryan, Robinson:

on 6 March set off to find the two remaining families. He crossed the Arthur River again, camping at Sundown Point. The next morning the mission Aborigines set off, and on 14 March found one family near the Arthur River. On 7 April they found the other family at Sandy Cape.

There is now a significant Aboriginal community living in the north-west. They, and indeed the entire Tasmanian Aboriginal community, have a strong association with the Arthur–Pieman Conservation Area. The coastal zone of the conservation area contains a richness of Aboriginal sites and landscapes that make this area unique and important to the Aboriginal community.

Scientific interest in the richness of cultural heritage material is also high. The Arthur–Pieman has been described as ‘...one of the world’s great archaeological regions’ by the Australian Heritage Commission (Richards & Richards in Harries 1992). Extensive parts of the Arthur–Pieman Conservation Area are listed on the Register of the National Estate (see Map 7) because of Aboriginal heritage values including:

• Bluff Hill Point;

• the Greenes Creek area;

• the Interview Art Site;

• the Nelson Bay area;

• the Norfolk Range, particularly the Sandy Cape and Johnsons Head area;

• the Ordnance Point area;

• the Temma coastal area.

Aboriginal sites are numerous and extensive. Sites include innumerable middens, artefact scatters and hut depressions, several art sites including rare examples of rock engravings, and ceremonial stone arrangements.

Aboriginal heritage objects are all protected by the Aboriginal Relics Act 1975.

91 The Plan required a new system for the management of recreational vehicles to be established and operational within 12 months, and shown to be effective within three years. The Plan further records as the first of several “General Prescriptions to apply for the life of the plan”:

• Use or construction of access routes and infrastructure which adversely impacts on Aboriginal sites is prohibited.

92 In 2010 (that is, prior to any determination under s 324JJ of the EPBC Act), Cultural Heritage Management Australia (CHMA) was engaged by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service to undertake an Aboriginal heritage assessment and to develop an Aboriginal Heritage Management Plan in respect of vehicle tracks in the APCA. Mr Huys was the principal archaeologist on this project and the author of the CHMA report. The report is dated 18 December 2010 and entitled “An Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment of Designated Vehicle Tracks within the Arthur Pieman Conservation Area”. The report was in evidence in this proceeding. The first section of the report is marked “Draft”, but Mr Huys explained in oral evidence that this was the form in which he submitted the report to Parks and Wildlife and that he understood the report would subsequently have been finalised. The respondents did not contend that a final version existed, nor that this version was incomplete, inaccurate or unreliable in any way. The report records at least 94 identified vehicle tracks that traverse the APCA.

93 The CHMA report notes that the natural environment in the APCA was such that it was in a constant state of flux and change, including because of regular tidal storm surges and periodic flooding. In addition, there are in the APCA a series of extensive mobile dune systems which are regularly deflated and recreated, and because of that movement Aboriginal sites in those areas are periodically exposed to the surface and then reburied through the movement of sand deposits. In some instances, the report stated, these natural impacts had been accelerated by human activity, most particularly through the erosion and associated destabilisation caused by vehicle and stock activity. Each of those matters was confirmed and adopted by Mr Huys in his expert report in this proceeding.

94 According to the schedule to the Minister’s declaration (made on 7 February 2013), the WTACL is an area of about 21,000 hectares, considerably smaller than the APCA.

95 The schedule to the Ministerial declaration describes the indigenous heritage value of the area in the following terms:

During the late Holocene Aboriginal people on the west coast of Tasmania and the southwestern coast of Victoria developed a specialised and more sedentary way of life based on a strikingly low level of coastal fishing and dependence on seals, shellfish and land mammals (Lourandos 1968; Bowdler and Lourandos 1982).

This way of life is represented by Aboriginal shell middens which lack the remains of bony fish, but contain ‘hut depressions’ which sometimes form semi-sedentary villages. Nearby some of these villages are circular pits in cobble beaches which the Aboriginal community believes are seal hunting hides (David Collett pers. comm.; Stockton and Rodgers 1979; Cane 1980; AHDB RNE Place ID 12060).

The Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape has the greatest number, diversity and density of Aboriginal hut depressions in Australia. The hut depressions together with seal hunting hides and middens lacking fish bones on the Tarkine coast (Legge 1929:325; Pulleine 1929:311-312; Hiatt 1967:191; Jones 1974:133; Bowdler 1974:18-19; Lourandos 1970: Appendix 6; Stockton and Rodgers 1979; Ranson 1980; Stockton 1984b:61; Collett et al 1998a and 1998b) are a remarkable expression of the specialised and more sedentary Aboriginal way of life.

96 After this description there is a hyperlink or cross reference to the recommendation of the Australian Heritage Council in relation to the WTACL. That recommendation stated:

Indigenous heritage values - above threshold

Specialised way of life:

While not claimed by the nominator, the Tarkine contains a suite of specialised coastal sites on the west coast that include large and complex multi layered shell middens containing well preserved depressions which are the remains of dome-shaped Aboriginal huts. These sites represent the best evidence of an Aboriginal economic adaptation which included the development of a semi-sedentary way of life with people moving seasonally up and down the north west coast of Tasmania. This way of life began approximately 1 900 years ago and lasted until the 1830s (Jones 1978:25).

From the late 1960s through to the 1980s, archaeological research demonstrated that the coasts of western Tasmania and southwest Victoria were areas where a specialised and more sedentary Aboriginal way of life developed during the late Holocene. The semi-sedentary Aboriginal way of life was based on a strikingly low level of coastal fishing and a dependence on seals, shellfish and land mammals of the region (Lourandos 1968; Bowdler and Lourandos 1982). Both these areas have ethnographic evidence that documents the presence of Aboriginal huts in the early 1830s (Plomley 1966; 1991, Mitchell 1988:14). The ethnographic records also reveal that huts were not only commonly found in coastal environments, but also found inland (Bowdler and Lourandos 1982:126; Plomley 1966 and 1991; Hiatt 1968b:191).

Seal Point, located on the Cape Otway coastline in southwest Victoria, is the only known published record of Aboriginal hut depressions on the mainland (Lourandos 1968). The midden at Seal Point contains the remains of 13 circular hut depressions clustered on a hillock with another set approximately 200m west (Mitchell 1988:13). The depressions themselves were approximately 2 metres in diameter and 20 centimetres in depth and date from about 1 450 years ago up until the 1830s (Lourandos 1968:85; Mitchell 1988:13).

Unlike southwest Victoria, the west coast of Tasmania has no less than 40 hut depression sites exhibiting considerable diversity in the number of hut depressions at each site (Jones 1947:133; Bowdler 1974:18-19; Legge 1929:325; Lourandos 1970: Appendix 6; Pulleine 1929:311-312; Ranson 1980; Collett et al 1998a and 1998b; Prince 1990 and 1992; Caleb Pedder pers. comm.) as well as inland (Hiatt 1967:191; Stockton 1984b:61).

The Tarkine area has the highest density of known hut sites on the west coast with just under half of the recorded sites occurring between the Pieman River and West Point. This includes West Point (five sets of depressions including a village of nine huts and three single huts), Rebecca Creek (village of eight huts), Pollys Bay North (village of seven huts with one outlier to the south), Bluff Hill Point (at least one hut), Couta Rocks (two huts), Ordnance Point (three huts), Nettley Bay (one hut), Brooks Creek (village of nine huts), Temma (village of three huts), Gannet point (village of seven huts), Mainwaring River (at least one hut), Sundown Point (one hut) (Legge 1928; Reber 1965; Lourandos 1968; Stockton 1971; Jones 1974; Ranson 1978; Ranson 1980; Stockton 1982; Stockton 1984a; Stockton 1984b; Collett et al l998a; Collett et al 1998b ). This diversity is greater than is found in southwest Victoria where only one site with hut depressions has been identified (Lourandos 1968).

A group of shell middens at West Point (at the northern end of the Tarkine) includes the best examples of these large, complex shell middens which contain the remains of 100s of seals, 10 000s of shellfish and to a lesser extent terrestrial mammals which were hunted in the hinterland just behind the foredunes. The main West Point shell midden is exceptional in terms of its size, measuring 90 metres long, 40 metres wide and 2.7 metres deep. It is densely packed with shells and animal bones with its total volume being estimated at 1 500 m3 (Jones 1981:7/88). The midden is some six metres above the general lay of the land giving a commanding all round view of the coast and surrounding hinterland (Jones 1981:7/88). At its highest point there is a cluster of nine hut depressions in the upper portion of the midden which date to less than 1 330±80 years BP (Jones 1971:609 in Stockton 1984a:9, 28). The depressions are circular, measuring approximately four metres in diameter and half a meter in depth (Jones 1981:7/88).

Based upon the analysis of the excavated archaeological remains from a hut depression at West Point, Jones concluded that the hut depressions were the remnants of a semi-sedentary ‘village’ (Jones 1981:7/88-9). The village was established approximately 1 900 years ago next to an elephant seal (Mirounga leonina) colony located on the varied littoral rocky embayments below the midden (Jones 1981:7/88). Based upon the large number of seal bones found in the midden, the elephant seals were a rich resource and a major component of the Aboriginal people’s diet in terms of gross energy (65% of the calories) (Jones 1981:7/88). The midden surrounding the hut depression at Sundown Point also contained a substantial number of fur seal bones (Stockton 1982:135). The Aboriginal community believes that the depressions in cobble banks were used as seal hunting hides (David Collett pers. comm.). Often these hunting hides are located in cobble beaches near seal colonies such as those at West Point and Bluff Hill Point (Stockton and Rodgers 1979; Cane 1980; AHBD RNE Place ID 12060).

Analysis of the faunal remains from the West Point midden indicates that mainly young calves were killed; indicating that between 1 900 and 1 300 years ago Aboriginal people inhabited the area in summer when young seals are being weaned. Calculations of the food energy derived from the quantity of shell and bone remains, 40 Aboriginal people could have inhabited the huts permanently, spending up to four months of every year for 500 years at West Point midden (Jones 1981:7/88-9). Sometime after 1 300 years ago the archaeological evidence indicates that the West Point midden was no longer used by Aboriginal people as they moved away from hunting seals (Jones 1981:7/88). Huts, however, continued to be built and used elsewhere in the Tarkine with a focus on gathering shellfish and the hunting of fur seals (Ranson 1978:156; Stockton 1982:135).

The extensive suite of shell middens along the north west coast reflect the specialised way of life developed by Aboriginal people in the late Holocene as they travelled up and down the coastline hunting seals, other land mammals and gathering shellfish. In particular, the apparent absence of fish bones, the presence of marine and terrestrial animal bones in some middens, when taken in conjunction with the hut sites, are an important expression of this specialised way of life.

The suite of Aboriginal shell middens, hut depressions sites and seal hunting hides in the Tarkine best represent a specialised and more sedentary Aboriginal way of life that developed on the coasts of west Tasmania and southwest Victoria during the late Holocene, based on a strikingly low level of coastal fishing and dependence on seals, shellfish and land mammals.

97 The correlation, even down to the language used, between the Council’s recommendation and the Ministerial declaration is apparent. I infer that the Minister placed significant reliance on the terms of the Council’s recommendation in making his decision.

98 In evidence which I accept and rely upon, Mr Huys explained how the WTACL represents a “specialised and sedentary way of life” for Aboriginal people not found in many other places in Australia.