FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bunavit Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 6

QUD 304 of 2013 | ||

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | BUNAVIT PTY LTD (ACN 144 589 613) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Bunavit Pty Ltd (ACN 144 589 613) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia in respect of the impugned conduct referred to in each of the following paragraphs of the amended statement of agreed facts annexed to these reasons, a pecuniary penalty fixed in the amount of:

para 9 - $7,000;

para 10 - $7,000;

para 13 - $7,000;

para 16(a) - $7,000;

para 16(b) -$1,000;

para 17 - $7,000;

para 18 - $1,000;

para 22 - $7,000;

para 25(a) - $7,000; and

para 25(b) - $1,000,

the total sum of $52,000 being payable within 28 days of the date of this order;

2. there be liberty to apply for an extension of time in which to pay the pecuniary penalty in order 1, or otherwise;

3. there be no order as to costs; and

4. all other orders as to costs be vacated.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DOWSETT J:

THE PROCEEDINGS

1 The applicant (“ACCC”) and the respondent (“Bunavit”) agree that during 2011 and 2012 the latter’s employees made certain oral statements to two consumers and, in so doing, contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(m) of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”). ACCC seeks declaratory and injunctive relief and the imposition of pecuniary penalties.

2 Bunavit operated as a single retail outlet (the “Store”) in Bundall, Queensland, under the trade name “Harvey Norman AV/IT Superstore Bundall”, selling electronic products and providing after-sales service. It traded pursuant to a franchise agreement with a subsidiary of Harvey Norman Holdings Ltd. I shall refer to both the parent and the subsidiary as “Harvey Norman”. Bunavit ceased trading in February 2015 and does not intend to trade in the future.

Procedural history

3 ACCC commenced these proceedings on 11 June 2013. On 19 August 2013, the matter was set down for hearing on 10 March 2014, the trial to address only the issue of contravention. The parties subsequently reached substantial agreement. The trial date was vacated. The parties filed a statement of agreed facts and joint submissions in connection with penalty. The hearing on penalty was set down for 10 March 2014. I heard the matter on that day and reserved my decision. However the publication of my reasons was subsequently deferred, pending the Full Court’s determination of proceedings arising out of the decision of the High Court in Barbaro v The Queen (2014) 253 CLR 58. The Full Court’s decision was published on 1 May 2015. However the High Court granted special leave to appeal. On 9 December 2015, the High Court upheld the appeal. See Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate; Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46.

The Facts

4 The parties have filed an amended statement of agreed facts pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). I attach it to these reasons. Whilst I generally accept the statement of facts as reliable, its utility would have been enhanced by the addition of more detail.

5 Bunavit sold a laptop computer to Ms Choyce and a desktop computer to Mr Bates. Both experienced problems with their respective computers. Each contacted the Store and spoke to unidentified sales representatives concerning their problems, seeking repair, refund or replacement. The problems were serious and prevented the operation or effective use of each computer. The sales representatives repeatedly denied any obligation on the part of Bunavit to remedy the problems.

Ms Choyce’s Complaints

6 On about 7 May 2011, Bunavit supplied Ms Choyce with a Sony laptop computer. In about mid-June 2011, Ms Choyce telephoned the Store and spoke to a sales representative concerning problems which she was having with it. In response, the sales representative told her that, in effect:

Since it is still covered by the manufacturer’s warranty you will have to go through Sony. We can’t help you. [the “first statement”]

7 At some time between June and September 2011, Ms Choyce again telephoned the Store. She spoke to a sales representative, identifying her continuing problems. That person said:

It’s still under manufacturer’s warranty. We can’t help. You have to go through Sony. [the “second statement”]

8 On or about 6 September 2011 Ms Choyce sent the laptop to Sony’s authorized service centre, Planet Tech. On the following day it was returned to her. Ms Choyce discovered that it had developed new problems. On about 7 September 2011, Ms Choyce again telephoned the Store concerning these issues. She spoke to a sales representative who said, in effect, that:

It’s still under manufacturer’s warranty. You have to go through Sony. [the “third statement”]

9 In late September or early October 2011, Ms Choyce returned the laptop to Planet Tech. On 29 November 2011 she collected it from the Store. A further problem emerged. The “DC input” was malfunctioning so that Ms Choyce could no longer charge the battery. In about December 2011, Ms Choyce again called the Store and spoke to two sales representatives concerning the DC input issue. One or other replied:

• The DC input issue is your problem. [the “fourth statement”]

• I cannot assist you further unless you want to pay for the repair. [the “fifth statement”]

10 On 20 January 2012, one of the two sales representatives telephoned Ms Choyce and said:

Harvey Norman is not willing to pay for a refund or replacement. In relation to the DC unit, Harvey Norman is not willing to pay for that either. The reason is that you did not come to us for the initial repair. [the “sixth statement”]

11 Later that day, the same sales representative again called Ms Choyce and said:

If you send the laptop back to Planet Tech to repair the DC input issue, then we will agree to pay for half of the repair costs. [the “seventh statement”]

12 Subsequently, Ms Choyce sent a letter of demand to Harvey Norman and contacted ACCC and the Queensland Office of Fair Trading. In early February 2012 Bunavit indicated that it would pay for the repair of the DC input. On 20 February 2012 Ms Choyce left the laptop at the Store for repair. She collected it on 15 March 2012.

Mr Bates’s Complaints

13 On 13 February 2011 Bunavit supplied Mr Bates with an ACER desktop computer. In April 2011, Mr Bates telephoned the Store and spoke to a sales representative concerning problems which he was experiencing. The sales representative replied:

There is nothing we can do at this stage. You have to use your warranty. Try to reformat it, and if that doesn’t work, you need to contact ACER. [the “eighth statement”]

14 On 19 May 2012, Mr Bates went to the Store. He told the manager that the computer had not worked properly since he had purchased it, and that ACER had been unable to fix it. Mr Bates left the computer at the Store for assessment. On the 22 May 2012, a sales representative telephoned Mr Bates twice. In the first call, Mr Bates asked that Bunavit replace the computer. The sales representative said:

The computer is out of warranty with ACER. It is a software problem and I don’t think the extended warranty people will deal with it. [the “ninth statement”]

15 In the second call, Mr Bates repeated his request, saying also that he had contacted the ACCC. The reply was:

Well, there’s nothing I can do until the ACCC calls me. [the “tenth statement”]

16 On or about 29 November 2012, Bunavit provided a full refund to Mr Bates.

17 Bunavit admits that the relevant sales representatives were in its employ, and that they were acting on its behalf. Hence their conduct is taken to be that of Bunavit. See s 139B(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the “CCA”). At least three sales representatives were involved in the conduct concerning Ms Choyce. Two sales representatives were involved in the conduct concerning Mr Bates.

Contraventions

18 ACCC alleges that in making these statements, Bunavit contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(m) of the ACL. Section 18 provides:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3‑1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

19 Section 29(1) relevantly provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods and services … :

…

(m) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3-2);

...

20 The distinction between misleading or deceptive conduct and a false or misleading representation may be elusive. However I accept that in many, perhaps most cases, a breach of s 29 will also constitute a breach of s 18. In effect, s 29 provides specific instances of the general rule prescribed by s 18. A breach of s 29 may attract a civil penalty. A breach of s 18 will not do so. In paras 27 – 34 of the amended statement of agreed facts the parties set out the basis upon which each of the ten statements is impugned.

21 With respect to each of the first, second and third statements, the parties agree that Bunavit represented that it would not, and had no obligation to provide a remedy for defective goods which it supplied, including Ms Choyce’s laptop when, in fact, it “could” have been obliged to provide certain remedies with respect to such goods which it had supplied, “possibly” including that laptop.

22 The parties agree that in the fourth to seventh statements Bunavit represented that:

Bunavit had no obligation to provide, and would not provide any remedies for the DC input issue raised by Ms Choyce, the goods still being under the manufacturer’s warranty;

Ms Choyce’s only option was to pay for such repairs, and Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not provide any remedy;

Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not repair the DC input, Ms Choyce not having first approached Bunavit for the initial repair; and

Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not provide any repair to Ms Choyce’s laptop, including the DC input, or was only obliged to pay half the cost of such repair.

23 In each case, the parties agree that Bunavit “could” have been obliged to provide such remedies with respect to goods which it had supplied, and “possibly” had such an obligation concerning Ms Choyce’s laptop. With respect to the seventh statement, it is agreed that Ms Choyce had, in fact, approached Bunavit requesting the initial repair.

24 The eighth, ninth and tenth statements concerned Mr Bates’ computer. The parties agree that in the eighth statement Bunavit represented that:

Bunavit had no obligation to, or would not provide any remedies whilst the computer was covered by the manufacturer’s warranty; and

Mr Bates’ only option, if reformatting did not remedy the defect, was to send the computer to the manufacturer.

25 The parties agree that these statements were false or misleading in that:

in certain circumstances, Bunavit “could” have been obliged to provide a remedy;

Bunavit “could” have been so obliged, independently of any liability in the manufacturer; and

Bunavit “possibly” had such an obligation in relation to Mr Bates’ computer.

26 The parties agree that in the ninth statement Bunavit represented that:

Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not provide any remedies in relation to problems with the software which it had supplied with the computer;

the manufacturer had no obligation to Mr Bates, given that its warranty had expired; and

the only remedies potentially available to Mr Bates were those arising out of contractual warranties so that Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not provide any remedies.

27 The parties agree that these representations were false or misleading because:

Bunavit “could”, in certain circumstances, have been obliged to provide remedies for defects in the software;

Bunavit “could” have been so obliged, independently of the manufacturer’s liability;

Bunavit “could” have been so obliged, regardless of whether any person was liable pursuant to a contractual warranty from the manufacturer or the supplier; and

Bunavit “possibly” had such an obligation in relation to Mr Bates’ computer so that Mr Bates “may” have had other contractual remedies.

28 The parties agree that in the tenth statement Bunavit represented that Bunavit had no obligation to, and would not provide any remedy in relation to Mr Bates’ computer until contacted by ACCC. Such representation was false or misleading as Bunavit “could”, in certain circumstances, have been obliged to provide a remedy, and “possibly” had such an obligation in relation to Mr Bates’ computer. Hence it seems that each of the statements is said to be false or misleading because by it, Bunavit represented that it had no obligations when it “could” (might) have had such obligations, “possibly” (perhaps) with respect to the goods in question.

FALSE OR MISLEADING STATEMENTS

29 Obviously enough, broad denials of liability by a supplier may mislead a consumer as to his or her rights. Even if such conduct does not have that effect, it may lead the consumer to conclude that persistence will involve too much trouble, with too little assurance of a satisfactory outcome. Nonetheless, the approach adopted in the agreed statement may cause considerable difficulty in day-to-day dealings between retailers and consumers. There will, from time to time, be unjustified claims for repair, replacement or refund. It would be unfair, and therefore unwise, to penalize a retailer for a bona fide denial of liability which later turns out to be wrong. That approach might lead a retailer to concede liability where none exists. Such statements will usually be oral and, on many occasions, imprecise. A denial of liability may be couched in ambiguous terms, in that it may be expressed and/or understood as relating to either the case in hand or to the general extent of the retailer’s liability. One wonders about the position of a solicitor who responds, on behalf of a retailer, to such a claim, denying liability.

30 Each statement is said to be contrary to s 29(1)(m). Hence the false or misleading statement must concern the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Div 1 of Pt 3-2). According to the statement of agreed facts, all but one of the impugned statements was false or misleading “under Parts 5-4 and 3-2 of the ACL”. The exception appears to be the representation in the sixth statement that Ms Choyce had not approached Bunavit for the initial repair. Part 3-2 prescribes a number of guarantees to be implied into acquisitions of goods by consumers as defined in the CCA. See s 4B. With that one exception all of the impugned transactions relate to such guarantees, although the relevant sections are not identified. Sections 54, 55, 56, 58, 59 and 61 are arguably relevant.

FINDINGS

31 Relying upon the amended statement of agreed facts, I find that Bunavit made ten representations in connection with the supply, or possible supply of goods or services, which representations were false or misleading and concerned the existence, exclusion or effect of any guarantee, right or remedy, in contravention of s 29(1)(m) of the ACL. In doing so, Bunavit engaged in conduct which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL.

32 I turn to the question of relief.

DECLARATIONS

33 Under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), the Court may grant declaratory relief. However the Court may decline declaratory relief where the issue is theoretical, where the dispute has ceased to be of any practical importance, or where the grant of a declaration would be of no practical use. See Meagher, Gummow & Lehane’s Equity Doctrines and Remedies (4th ed) at [19-115]. The parties submit that there is a real, and not theoretical legal controversy to be resolved. That may have been so, but it is no longer the case. The dispute has been resolved by the amended statement of agreed facts and my findings, leaving for resolution only the question of relief. The declarations are not sought to resolve the dispute, but rather to publicize its resolution. The parties submit that a declaration will:

record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

vindicate the ACCC’s claim that Bunavit has contravened the ACL;

assist the ACCC to carry out the duties conferred upon it by the CCA; and

deter other corporations from contravening the ACL.

34 In my view, the imposition of pecuniary penalties will fulfil those functions. Notwithstanding this view, I would have been more inclined to grant declaratory relief were it not for the curiosity of the alleged misconduct. I do not fully understand how a statement of opinion as to a possible obligation, a mixed question of law and fact, can be demonstrably false, misleading or deceptive simply because the relevant party “could” be obliged to provide certain remedies, or might “possibly” have had an obligation to do so. The proposition seems to assume that a statement that there is no obligation is false, misleading or deceptive if there may be such an obligation, in some unspecified circumstances, not necessarily related to the present case, or only possibly related to it.

35 It would be difficult to craft a useful and completely accurate declaration. The proposed declaration is perhaps as misleading as are the statements about which ACCC complains. A lay third party reading it, would almost certainly infer that to make any of the ten statements would necessarily involve infringement of the ACL. It is true that a declaration might discourage retailers and their employees from saying such things. However there may well be circumstances in which many, if not all of the statements could properly be made. For example:

the claimed defect may have been covered by the manufacturer’s warranty, but not be a defect for which the retailer was liable;

the problem with the DC input may have been the product of mistreatment of the appliance by the consumer;

in some circumstances, it may have been correct that the only available remedy was at the expense of the consumer;

if repair by somebody else had caused further damage, then it may have been accurate to say that there was no obligation to remedy the defect; and

the offer to pay half the cost of repair may have been a reasonable compromise rather than a misleading statement.

36 None of these circumstances may exist in the present case, but that is not the point. The value of the declaration must be in the message that it will send to others. There is no point in sending a misleading message. Further, the Court must ensure that it does not do so.

37 I should add one other comment. Notwithstanding Bunavit’s concurrence in the findings of fact and proposed orders, I am far from convinced that the alleged breaches of s 29 are necessarily breaches of s 18, although some may well be. In this regard I refer particularly to the “conditional” nature of the alleged obligations said to render the statements false or misleading. Whilst I am willing to act on Bunavit’s admissions for the purpose of imposing pecuniary penalties, I am rather more reluctant to do so where the effect may involve making a misleading statement to the public at large.

38 For these reasons, I decline to grant declaratory relief.

Injunctions

39 A final, as opposed to an interlocutory injunction will be granted only to restrain conduct which has been shown to be unlawful, or in breach of the rights of another. The parties rely on s 232 of the ACL in support of their claim to injunctive relief. Section 232(1) relates only to the breaches of the law which are there identified. They are contraventions of Chs 2, 3 and 4 of the ACL and associated breaches. Section 29(1)(m) is found in Ch 3. In granting such relief, a court must ensure that the enjoined party is clearly informed as to the prohibited conduct. The requirement for certainty is a matter of fairness. It ensures that there is a clear standard against which any alleged breach may be measured, in order to determine whether the enjoined party is in contempt of court, with the serious consequences which may follow.

40 Notwithstanding s 232(4), the considerations there identified are still relevant to whether the discretion to grant injunctive relief should be exercised. The function of s 232(4) is simply to make it clear that those factors need not be present in order to justify the grant of such relief. For present purposes, it is relevant that Bunavit ceased trading in February 2015 and has no intention of trading in the future. If that is the case, and I accept that it is, then it is unclear to me how Bunavit might, in the future, engage in any of the contravening conduct. Notwithstanding s 232(4)(a), one must question the utility of such an injunction. Concerning injunctive relief generally, I adopt the reasoning of Mortimer J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Artorios Ink Co Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 1292 at [45] – [73].

41 I am also concerned that the proposed injunction may be too wide, having regard to the impugned past conduct and the relevant law, and too vague to be readily enforceable.

42 None of the orders is expressly limited to conduct in trade or commerce. The injunction should probably be limited to conduct in retail trade. The word “customer” may, to a certain extent, limit the operation of the injunction, but the word is not defined. Use of that word probably extends the operation of the injunction to include transactions with non-consumers. Any injunction should probably distinguish between conduct which is proscribed only where the relevant transaction is with a consumer and conduct the proscription of which is not so limited.

43 The terms “manufacturer’s warranty”, “manufacturer’s contractual warranty” and “extended contractual warranty” in para 2(a)(i) are not defined. The proposed injunction would restrain Bunavit from telling a purchaser that his or her complaint fell within the manufacturer’s warranty, but was not the subject of any obligation owed by Bunavit, even if that were so. Finally the words, “does not have any obligation to provide any remedies”, would be wide enough to restrain Bunavit from advising a purchaser that particular relief was simply not available under the law, even if that were the case.

44 The difficulty probably lies in ACCC’s failure to distinguish between a general statement that Bunavit could never, under any circumstances, be liable to refund, replace or repair and a more specific statement as to its understanding of its obligations in a particular case. Although it may be possible to read the wording of the various statements, in the context in which they were made, as being of the former kind, it is much more likely that the parties would have understood them as being of the latter kind. Hence I suspect that the proposed injunction would go beyond the facts of the case.

45 The proposed order dealt with in para 2(a)(ii) shares many of those problems. Further, it deals with Bunavit’s obligations after an attempted repair by somebody else. It makes no provision for the denial of a remedy where the defect is the product of such prior repair. Similar comments apply to paras 2(a)(iii), 2(a)(iv), 2(a)(v) and 2(a)(vi). Paragraph 2(a)(iv) relates to representations as to repair. Paragraph 2(a)(v) relates to “any remedies”. Paragraph 2(a)(vi) relates to representations to the effect that there is no obligation to provide a remedy other than repair.

46 Paragraph 2(a)(vii) has similar problems. However there is a further difficulty. In my view Bunavit was offering to settle a dispute, not making a representation. Quite apart from anything else, it would not generally be desirable to restrain attempts to settle a dispute, even if one party is totally in the wrong.

47 Paragraph 2(a)(viii) is to the same effect as para 2(a)(iv), save that it is limited to software. My earlier comments apply. Further, on its face, the statement is no more than an opinion as to the likely attitude of a third party to a claim under an extended warranty. The statement says nothing expressly about Bunavit’s liability. ACCC asserts that it is implicit in the statement that Bunavit was not, itself, under any obligation to provide a remedy. It may well be that the context in which the statement was made justifies such an approach. However an injunction, not limited by such context, goes beyond the conduct which may properly be enjoined.

48 Proposed order 2(a)(ix) relates to the tenth representation. At one level it seems reasonable that a retailer, told that ACCC was involved, should suggest that further discussion be deferred until ACCC contacts it. Such an approach would avoid double-handling of the complaint, and would be consistent with the customer’s apparent wish to have the ACCC’s assistance. Further, given the history of the matter, it seems most unlikely that the statement was intended to mean, or understood to mean that Bunavit’s liability depended upon its being contacted by ACCC. In my view, the customer would probably have understood and accepted the retailer’s reasons for waiting for ACCC to make contact. I find it difficult to understand how such a statement can be said to be false or misleading.

49 Paragraphs 2(b) and 2(c) do little more than reflect the assertions made in para 2(a), although in different forms.

50 I accept that Bunavit has consented to this injunctive relief. Were the orders specific in their operation and clear in their meaning, I might well have granted such relief, notwithstanding my view that such orders are largely pointless. However Bunavit’s consent does not ensure that the proposed injunctions are as clear as is generally desirable. There are obvious difficulties in trying to restrain the use of particular words in a wide range of, largely unpredictable, circumstances. This is particularly so, given the somewhat strained meanings which have been given to the statements in question. Many of the proposed orders would limit the way in which Bunavit might respond in good faith to a doubtful complaint. Notwithstanding Bunavit’s consent to such injunctive relief, I consider that the proposed injunctive relief would restrain conduct well beyond conduct of the kind which is impugned in these proceedings. Were Bunavit to recommence trading, it is likely that there would be disagreements about the extent of the enjoined conduct. Further, as with the proposed declaratory relief, the proposed injunctive relief might well mislead third parties concerning the proper response by a retailer to a customer’s complaint.

51 For these reasons, I decline to grant injunctive relief.

Pecuniary Penalties

52 The Court may impose a pecuniary penalty for contravention of s 29(1)(m) of the ACL. Section 224(1) relevantly provides:

If a court is satisfied that a person…has contravened…a provision of Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices)…the court may order that the person pay to the Commonwealth…such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the court determines to be appropriate.

Part 3-1 contains s 29(1)(m).

53 In fixing such a penalty, the Court will usually take into account a wide range of circumstances. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL Sales Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1030 at [52], Middleton J said:

Furthermore, the case law concerning s 76E of the TPA which preceded s 224 of the ACL established a number of further factors which should be considered (relevant to this proceeding):

(1) The size of the contravening company;

(2) The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(3) Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at a lower level;

(4) Whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the legislation as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(5) Whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the applicable legislation in relation to the contravention;

(6) Whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(7) The financial position of the contravener; and

(8) Whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

54 The primary purpose to be served by the imposition of a pecuniary penalty under s 224 of the ACL is deterrence, both general and specific. In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249, the Full Court (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ) observed at [62]:

... in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business.

55 As Finkelstein J said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd [2001] FCA 383 at [13], the penalty must be at, “a level that a potentially offending corporation will see as eliminating any prospect of gain”.

Facts Pertaining to Penalty

56 Over a period of about a year, there were ten incidents involving about five staff. There is no suggestion that senior staff were involved. The contraventions were by way of oral representations. The impugned conduct, overall, shows considerable persistence in resisting any suggestion that Bunavit might have obligations concerning defective products. The evidence might not justify the conclusion that the relevant staff members were giving effect to policy laid down by their superiors. However it would support an inference that these staff members were not appropriately trained in dealing with complaints. There is no evidence suggesting that such misconduct was otherwise prevalent at the Store. However it would nonetheless be difficult to infer that the conduct was necessarily isolated. There is no evidence that the false, misleading or deceptive effect was deliberate.

57 A great number of electronic devices are purchased by consumers from retailers such as Bunavit. Consumers frequently return such devices, claiming that they are faulty, or not of an acceptable quality. A retailer should ensure that its staff members are informed about, and conduct themselves in conformity with the ACL. In the three years prior to February 2015, Bunavit staff:

attended a face-to-face consumer law training session presented by an external professional trainer engaged by Harvey Norman;

watched two DVDs, received from Harvey Norman, explaining the consumer law provisions;

watched six ACCC consumer law video presentations;

from time to time, received memoranda from Harvey Norman on various aspects of consumer law, which memoranda were read and discussed at Bunavit’s weekly staff meetings; and

have had consumer law discussions as a fixed agenda item at weekly staff meetings where staff shared their experiences with customers relating to consumer law.

58 Obviously, the training did not avoid the conduct with which this case is concerned. However it may be that at least some of the misconduct occurred prior to such training.

59 There is no evidence to suggest that Bunavit’s conduct caused loss or damage to either Ms Choyce or Mr Bates. Nonetheless such conduct undoubtedly caused great inconvenience to them.

60 Bunavit has co-operated with ACCC. At an early stage in the proceedings, it proposed a settlement meeting, following which settlement was reached. Given the possibly inadvertent nature of the misconduct, and the equivocal nature of the statements in question, more than usual weight should be accorded to such co-operation. I should add, however, that in the comparable cases to which I refer below, that level of co-operation seems to have been a common feature.

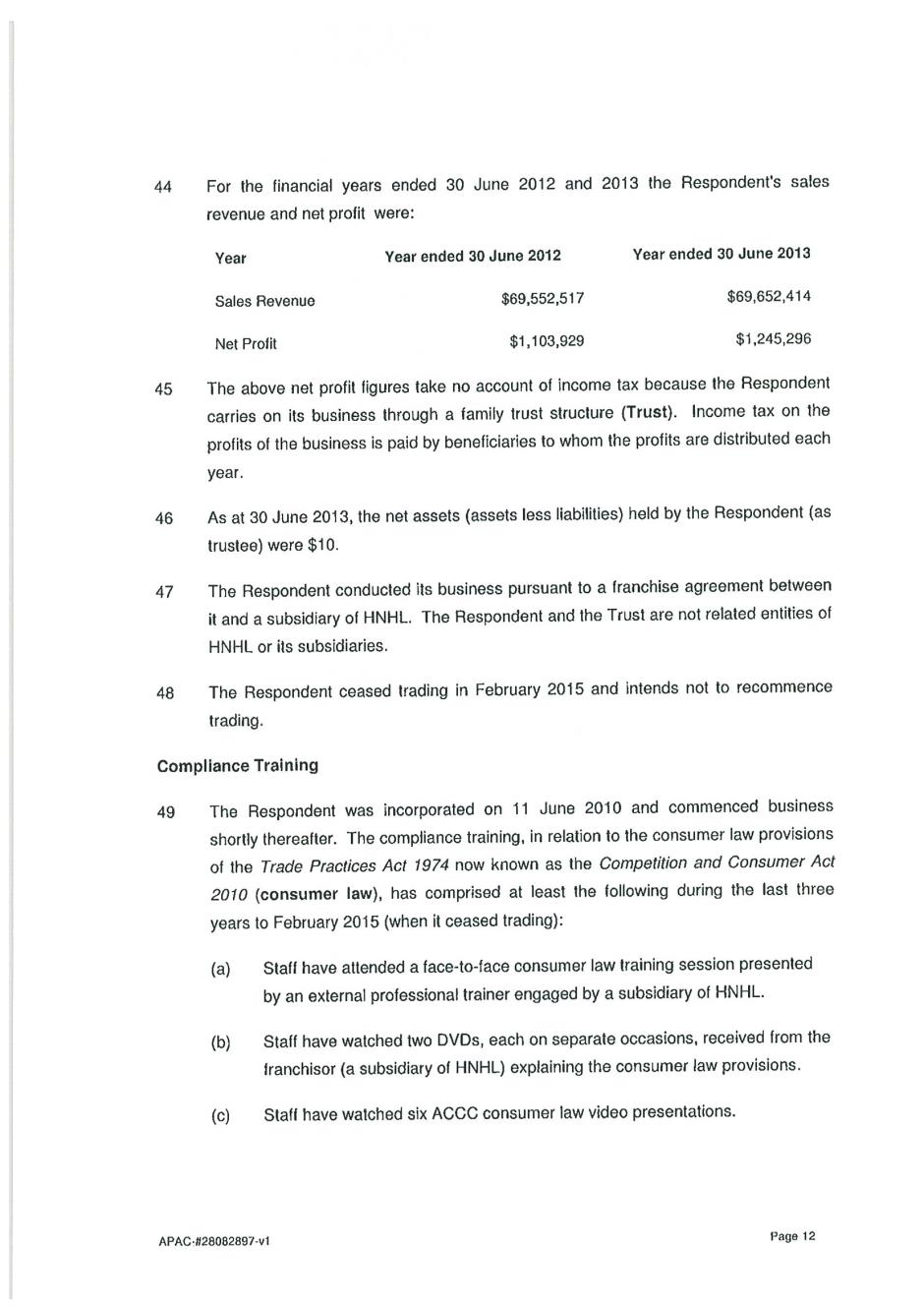

61 As at 18 November 2013, Bunavit employed 70 persons full-time, 32 persons part-time, and 45 persons on a casual basis, a total of 147 people. For the financial years ended 30 June 2012 and 2013, Bunavit’s sales revenue and net profit were:

Financial Year | July 2011 - June 2012 | July 2012 - June 2013 |

Sales Revenue | $69,552,517 | $69,652,414 |

Net Profit | $1,103,929 | $1,245,296 |

62 The net profit figures do not take into account income tax. Bunavit carried on its business through a family trust, so that the beneficiaries paid income tax on the amounts which they derived from the trust. As at 30 June 2013, Bunavit’s net assets as trustee totalled $10. Neither Bunavit nor the trust is related to Harvey Norman.

The Comparable Cases and the Appropriate Penalty

63 Pursuant to s 224 the maximum penalty for each breach committed by a corporation is $1.1 million. In most cases, it is important that in fixing a sentence or penalty, the Court keep in mind the maximum penalty. However s 224 applies to many and varied categories of proscribed conduct, and the range of circumstances which may constitute each of them is very wide. For conduct in the presently relevant categories, and involving the conduct in question, the maximum penalty is obviously of little or no relevance.

64 The parties have drawn my attention to nine cases which are said to be relevantly comparable. In each case, the Court imposed the penalty proposed by the parties. They are:

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Moonah Superstore Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1314;

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Launceston Superstore Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1315;

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Salecomp Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1316 (“Salecomp”);

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HP Superstore Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1317;

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Camavit Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1397;

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Oxteha Pty Ltd [2014] FCCA 1428 (“Oxteha”);

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Avitalb Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 222 (“Avitalb”);

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Mandurvit Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 464 (“Mandurvit”); and

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Gordon Superstore Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 452 (“Gordon”).

65 The circumstances of each of these cases bear substantial similarity to those of this case. In Avitalb at [96] Griffiths J summarized the relevant circumstances of that case and six of the other cases. Those circumstances included:

the amount of the penalty;

the number of contraventions;

the total number of staff members involved;

the involvement of senior management;

the period over which the contraventions occurred;

the sales turnover of the relevant corporation; and

its net profit.

66 In the present case Bunavit has admitted 10 contraventions. The range in the other cases varies between one and seven. In the present case the total number of staff involved appears to have been four or five. In earlier cases, the number varied between one and four. As to senior management’s involvement, in two cases, one of the staff members was a store manager. In the others there was no involvement of senior management. In this case, Mr Bates spoke to a store manager on one occasion, but there is no suggestion that a manager was directly responsible for any of the contraventions. In the present case the contraventions extended over a period of about one year. In each of the comparable cases a much shorter period was involved, save in Salecomp which involved a period of eight months. As to turnover, in the comparable cases turnover ranged between $5.6 million and $31.2 million. Net profit varied between $60,000 and $409,000. In the present case turnover for the 2011/2012 year was in excess of $69 million. A similar figure is shown for the 2012/2013 year. In the 2011/2012 year the net profit was $1,103,929. In 2012/2013 the net profit was $1,245,296. Thus it seems that the Bunavit operation was significantly larger than any of those considered in the comparable cases, and was yielding more profit, at least in dollar terms.

67 I turn to the three cases not considered by Griffiths J in Avitalb. In Oxteha a Federal Circuit Judge fixed a penalty in the amount of $26,000. The relevant conduct involved five infringements over about two weeks, by two employees. There was no suggestion that senior staff were involved. The company had a turnover of $40 million. There is no indication as to profit. In Mandurvit a penalty of $25,000 was imposed in respect of two statements, both of which occurred on one day. They were made by sales representatives, not senior management. The company’s turnover for each of the financial years ended 30 June 2012 and 30 June 2013 was in excess of $19 million, with net profits of $202,398 and $265,341 respectively. In Gordon there were five impugned statements, made over a period of two months, involving two staff members, one of whom was the store manager. The store manager spoke to the customer on four of the five occasions. The company’s sales revenue for each of the years ended 30 June 2012 and 30 June 2013 was, respectively, just under $9 million and just over $9 million, with a net profit of $136,766 in 2011/2012 and $91,581 in 2012/2013.

68 The comparison shows that in the present case:

compared to these comparable cases, there were significantly more impugned statements;

the overall conduct continued over a longer period;

more staff members were involved;

Bunavit’s turnover and profit were substantially higher than those of the other offending companies.

Unlike some of the other cases, none of Bunavit’s senior staff was involved.

69 One must be careful concerning the use of evidence about turnover and profit. The law does not usually treat, as an aggravating factor, the financial capacity of an offender. On the other hand the courts have traditionally taken into account, by way of mitigation, the hardship which a substantial penalty might inflict on a person of limited means. The size of a business undertaking in financial terms may, nonetheless, say something of relevance about its misconduct. Firstly, its financial capacity indicates its ability to adopt appropriate procedures for preventing breaches of the law, particularly breaches which may adversely affect customers. Secondly, the size of the undertaking, however it is measured, may say something about the number of people who may be adversely affected by staff misconduct, thus accentuating the need for appropriate systems and staff training.

70 Section 224(1) contemplates the Court fixing a pecuniary penalty in respect of each act or omission. I propose to adopt that approach. However I must keep in mind the possibility that some of the conduct may be part of a larger, overall course of conduct. The Court must strive to avoid double punishment. Similarly, in any case in which numerous contraventions are established, the Court must assess the overall degree of misconduct.

71 Although the figure probably has no real significance, the cases to which I have referred show a range “per contravention” of between $4,000 and $14,000. However it is likely that the total figure imposed in each case gives a better guide, based on the overall degree of misconduct.

72 In the present case the fourth and fifth statements should be treated as part of the one course of conduct. They both occurred in the one telephone conversation concerning Ms Choyce’s complaint about a problem with her DC input. The sixth and seventh statements both occurred on the same day, but probably not in the same telephone conversation. Between the two statements Bunavit’s position seems to have changed. Initially, it was not willing to pay for a refund or replacement as it claimed incorrectly, that Ms Choyce had not gone to them for the initial repair. Subsequently, Bunavit offered to pay half of the repair cost associated with the DC input issue. In any event, the two statements are sufficiently related to allow me to treat them as part of one course of conduct. In connection with Mr Bates’ complaints, it is appropriate to treat the ninth and tenth statements as being part of the same course of conduct. Both conversations occurred by telephone on 22 May. In the first conversation Mr Bates was told that the computer was out of warranty, that it was a software problem and that the “extended warranty people” would not deal with it. In the subsequent conversation the employee made the remark about waiting to hear from the ACCC.

73 The parties have agreed to a total penalty of $35,000. However, they have not explained how they have chosen that figure. The misconduct in this case is much more serious than that in any of the comparable cases. I do not consider that penalties totalling $35,000 would sufficiently reflect the seriousness of the conduct presently under consideration.

74 Setting aside the question of the overall degree of misconduct, I would be inclined to impose a penalty of $8,000 with respect to each of the first, second, third, fourth, sixth, eighth and ninth statements. I would treat the fourth and fifth statements as part of the same course of conduct, and impose a penalty of $1,000 in connection with the latter. Similarly, I would treat the seventh statement as being part of the same course of conduct as the sixth statement and impose a $1,000 penalty with respect to it. I similarly treat the tenth statement as part of the same course of conduct as the ninth statement. In fixing these penalties, I have taken into account the penalties imposed in the comparable cases to which I have referred. As most of them involved co-operation of the kind given by Bunavit, it is not necessary that I make any further allowance for it.

75 Those penalties total $59,000, that is, $8,000 for each of the seven primary offences and $1,000 for each of the three secondary offences. Having regard to the totality of the penalties imposed in the other cases to which I have referred, and considering the overall degree of misconduct, I shall reduce some of the penalties to which I have referred. With respect to each of counts 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 9, I impose a penalty of $7,000. With respect to each of counts 5, 7 and 10, I impose a penalty of $1,000. Hence with regard to each of the 10 statements referred to in paras 9 – 25 of the amended statement of agreed facts annexed to these reasons, I order that Bunavit Pty Ltd pay to the Commonwealth of Australia, a pecuniary penalty fixed in the amount of:

para 9 - $7,000;

para 10 - $7,000;

para 13 - $7,000;

para 16(a) - $7,000;

para 16(b) -$1,000;

para 17 - $7,000;

para 18 - $1,000;

para 22 - $7,000;

para 25(a) - $7,000; and

para 25(b) - $1,000.

76 I further order that Bunavit Pty Ltd pay the said total sum of $52,000 within 28 days after the delivery of these reasons. I grant liberty to apply for an extension of time in which to pay or otherwise.

COSTS

77 The parties have agreed that each should bear its own costs. I therefore make no order in that regard. I vacate all other orders as to costs.

I certify that the preceding seventy-seven (77) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Dowsett. |

Associate: