FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Health Services Union v Jackson (No 5) [2015] FCA 1467

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Applicant | |

AND: | Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | KATHERINE JACKSON Cross-Claimant |

AND: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Cross-Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent pay the applicant $554,215.67 by way of judgment interest.

2. Pursuant to r 40.02(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) the respondent pay the applicant’s costs by way of a lump sum order fixed at $356,500.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

FAIR WORK DIVISION | NSD 1501 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | ROBERT ELLIOTT Applicant |

AND: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Cross-Claimant |

AND: | ROBERT ELLIOTT First Cross-Respondent |

MICHAEL WILLIAMSON Second Cross-Respondent | |

KATHERINE JACKSON Third Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | TRACEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 DECEMBER 2015 |

WHERE MADE: | MELBOURNE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

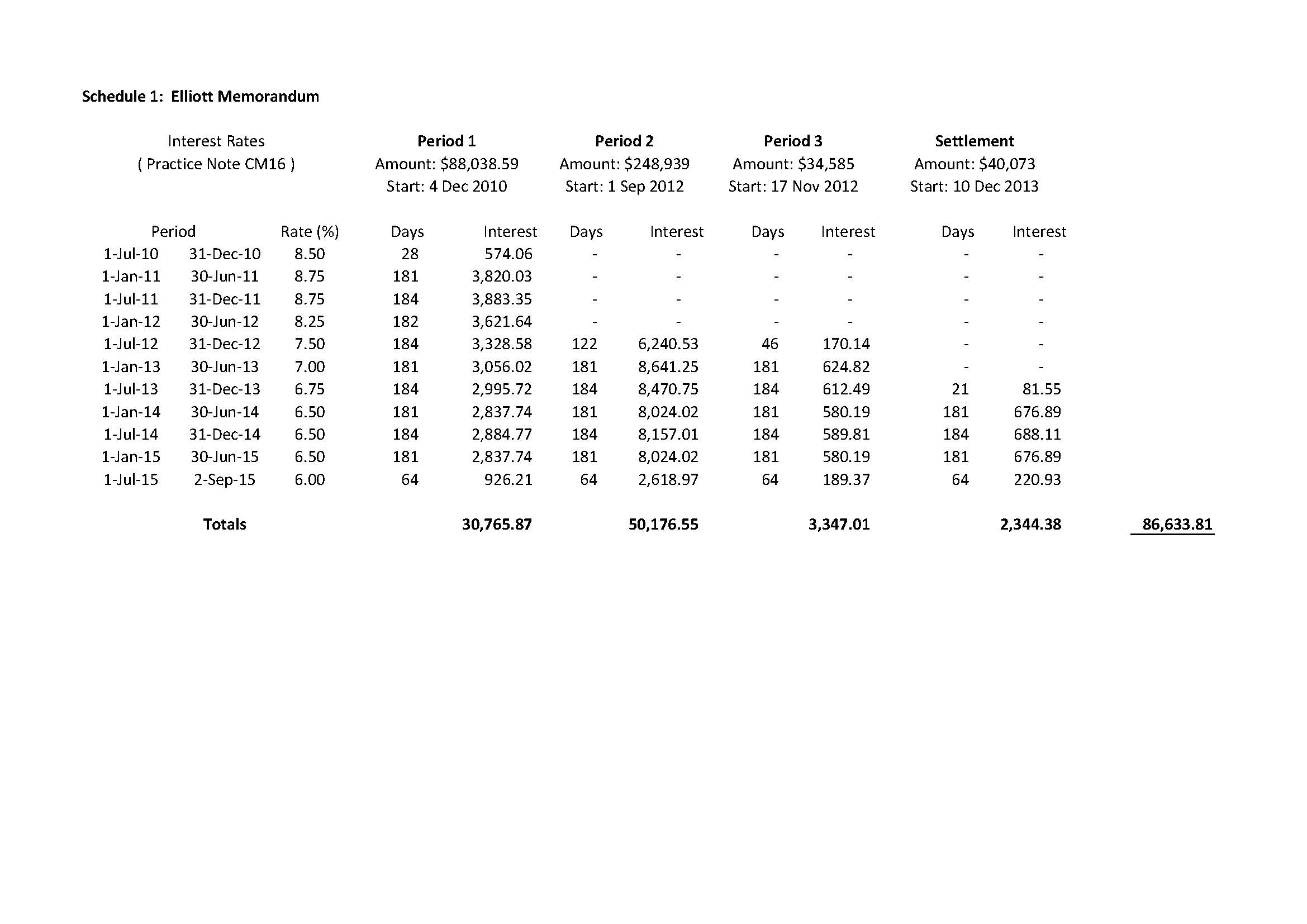

1. The third cross-respondent pay the respondent/cross-claimant $86,633.81 by way of judgment interest.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

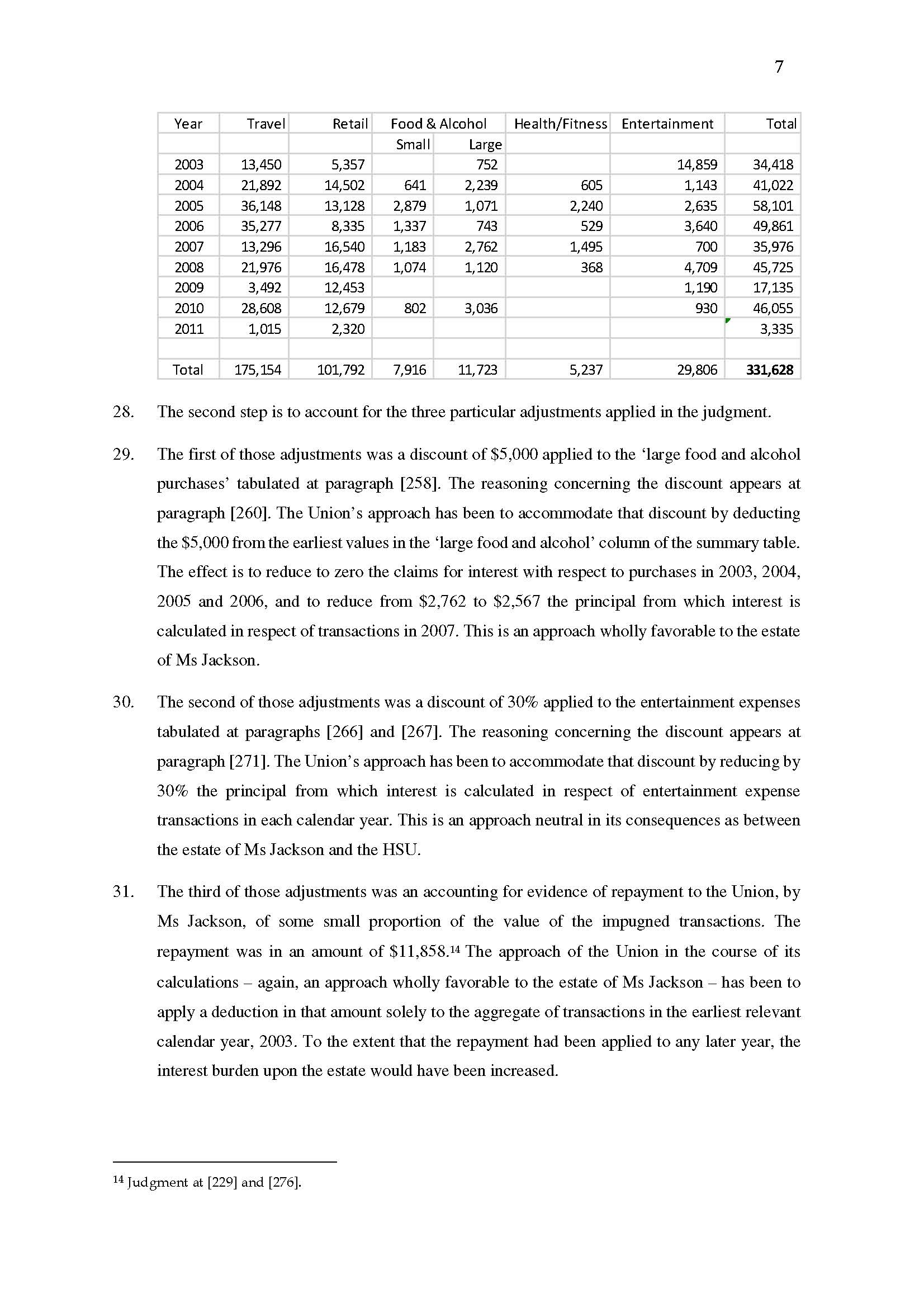

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

FAIR WORK DIVISION | VID 1042 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Applicant |

AND: | KATHERINE JACKSON Respondent |

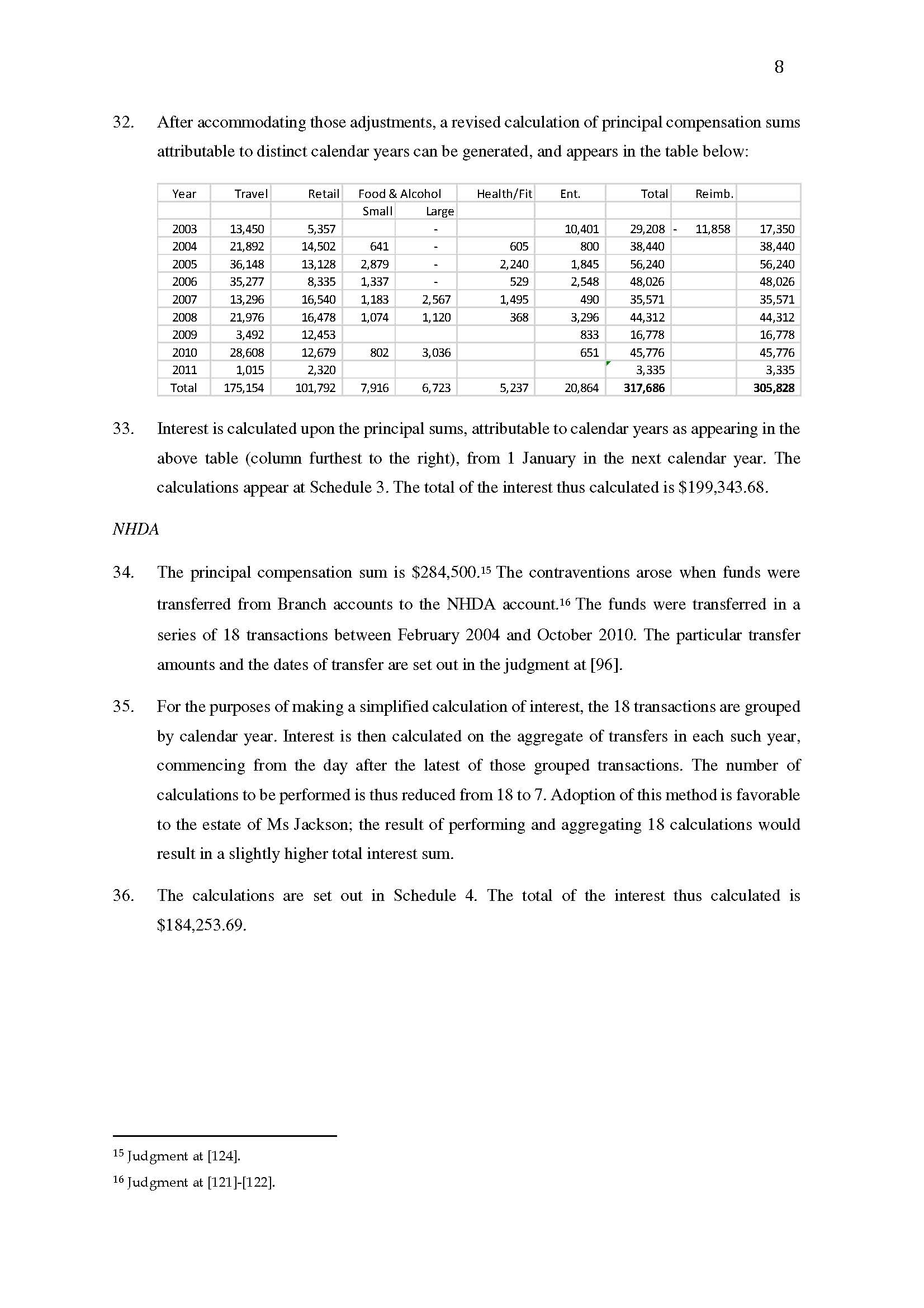

AND BETWEEN: | KATHERINE JACKSON Cross-Claimant |

AND: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Cross-Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

FAIR WORK DIVISION | NSD 1501 of 2013 |

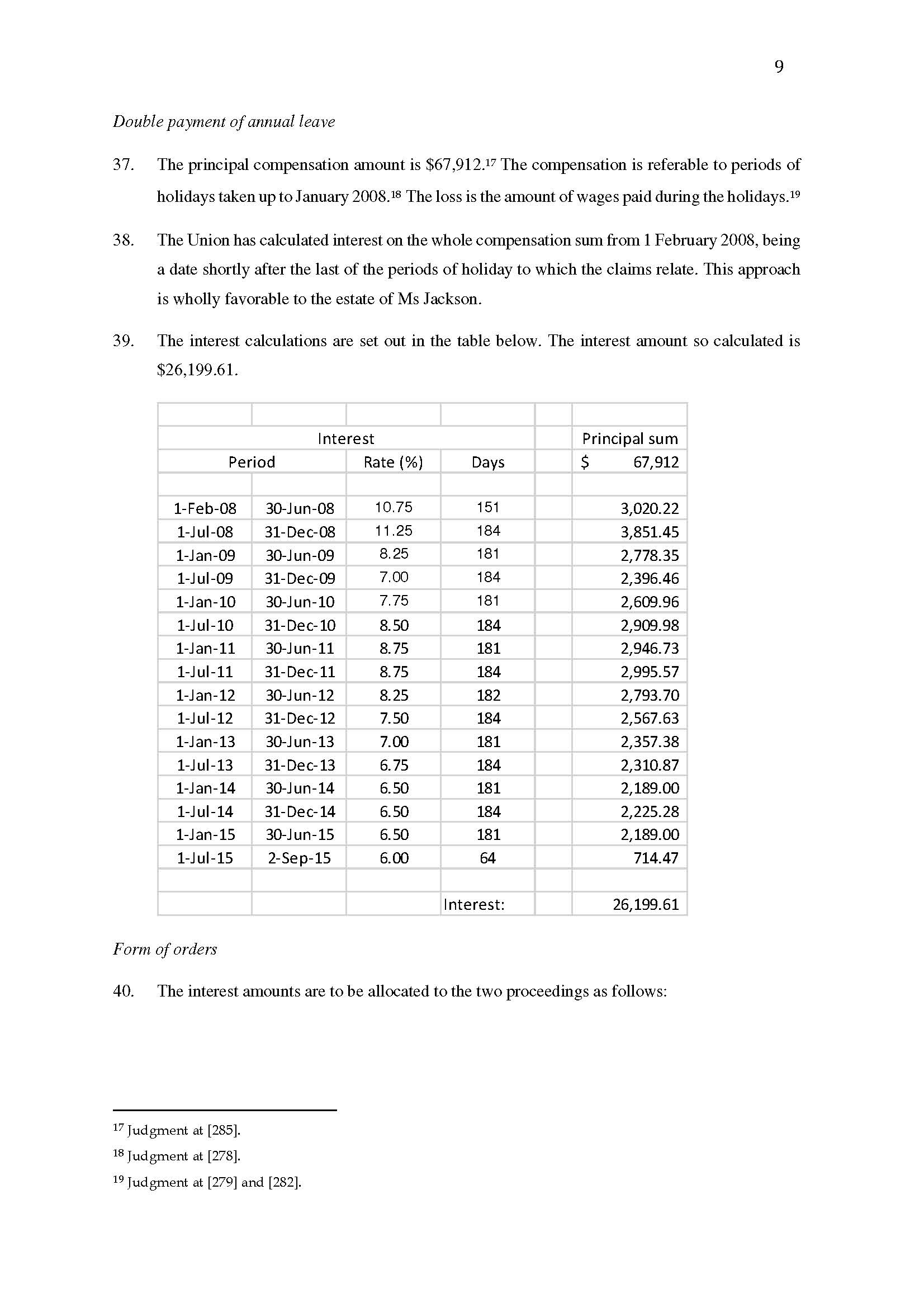

BETWEEN: | ROBERT ELLIOTT Applicant |

AND: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | HEALTH SERVICES UNION Cross-Claimant |

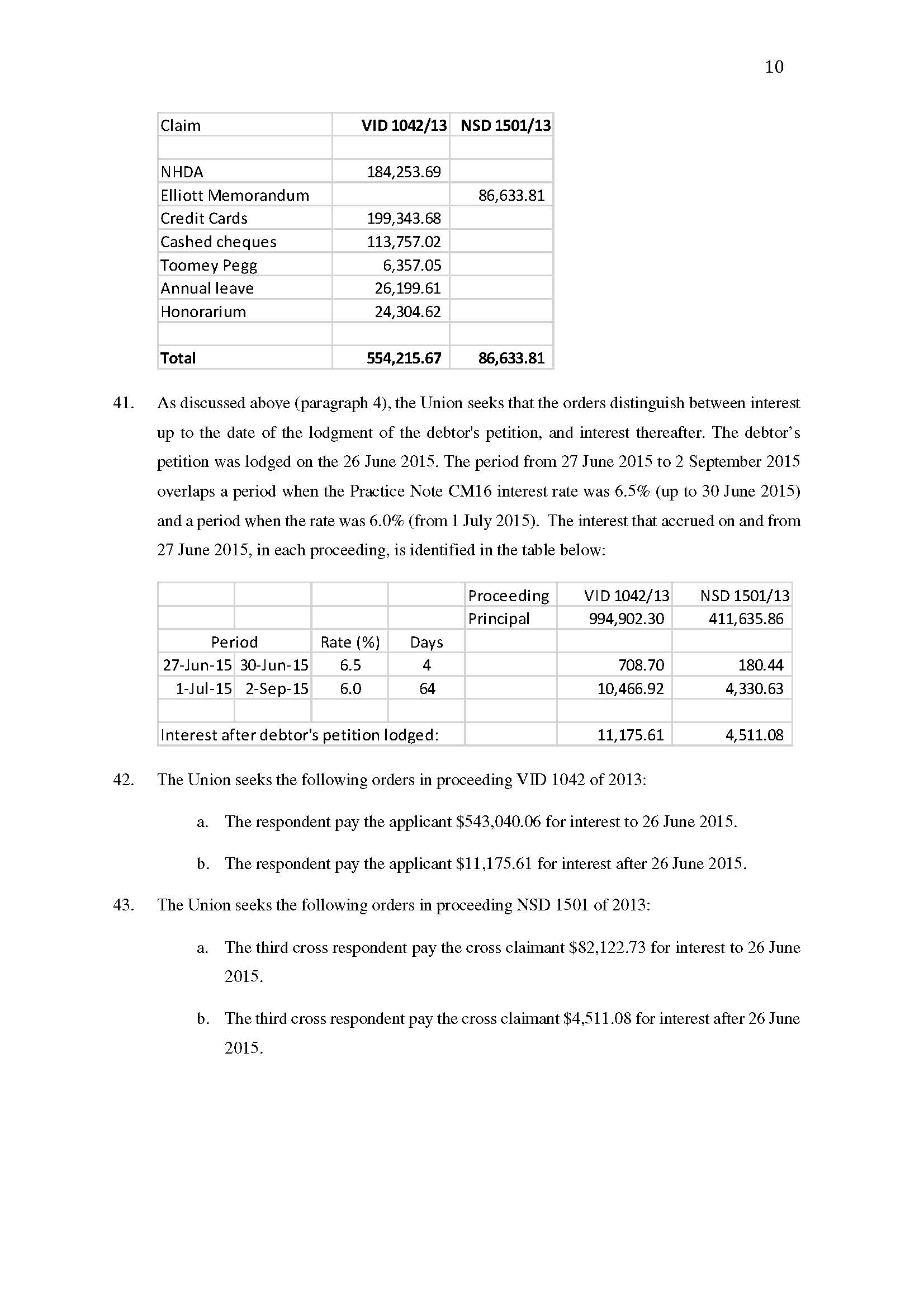

AND: | ROBERT ELLIOTT First Cross-Respondent |

MICHAEL WILLIAMSON Second Cross-Respondent | |

KATHERINE JACKSON Third Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | TRACEY J |

DATE: | 22 DECEMBER 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 19 August 2015 I made orders requiring Ms Jackson to pay various sums to the Health Services Union (“the Union”) by way of compensation for damage suffered by it which was caused by various contraventions by her of legislative requirements and as money had and received by her for the use of the Union: see Health Services Union v Jackson (No 4) [2015] FCA 865. I further ordered that, if the Union sought any further amounts by way of costs and interest, it should file written submissions. It did so on 2 September 2015. It filed supplementary submissions on 4 November 2015.

2 The Union has sought the following orders:

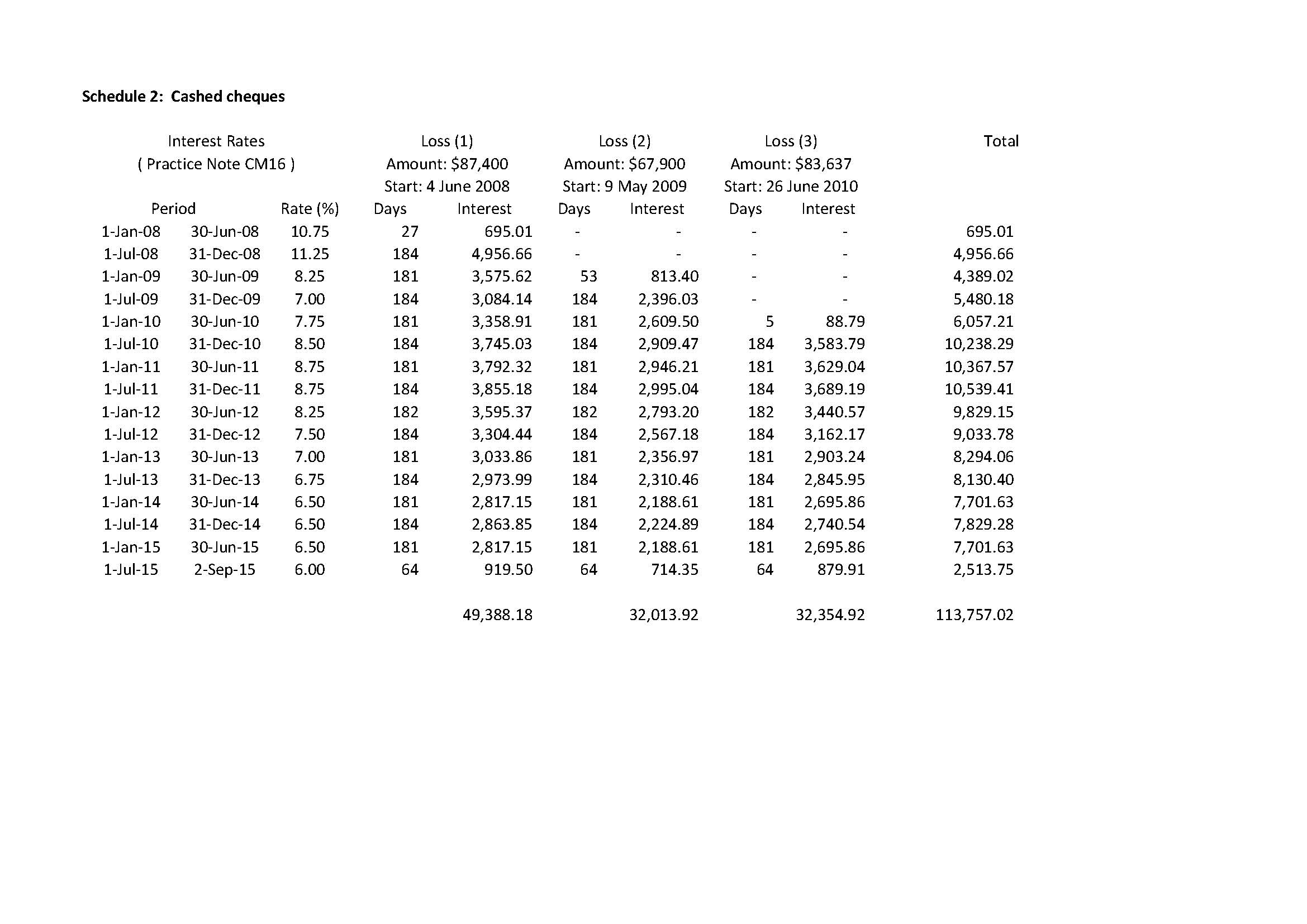

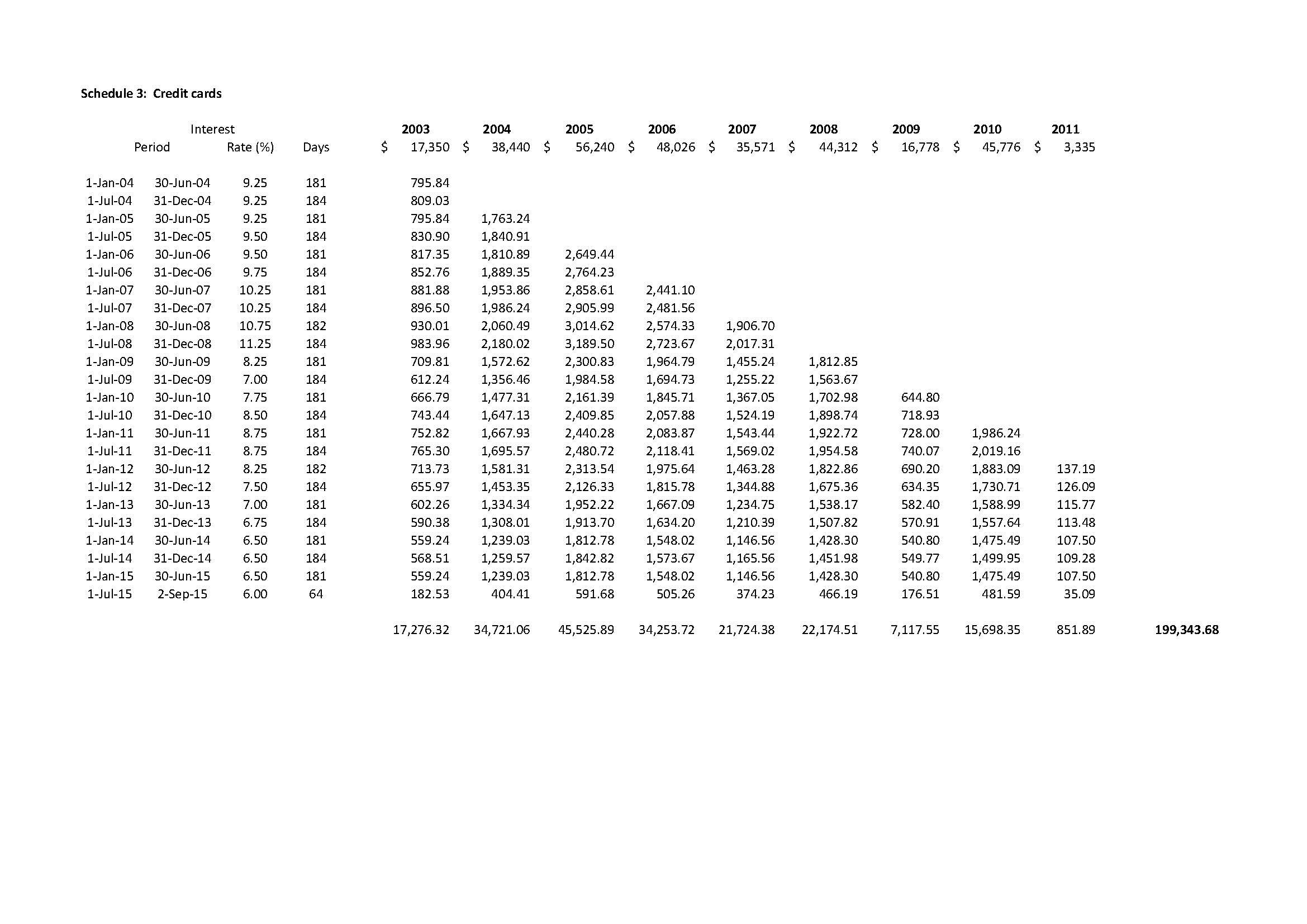

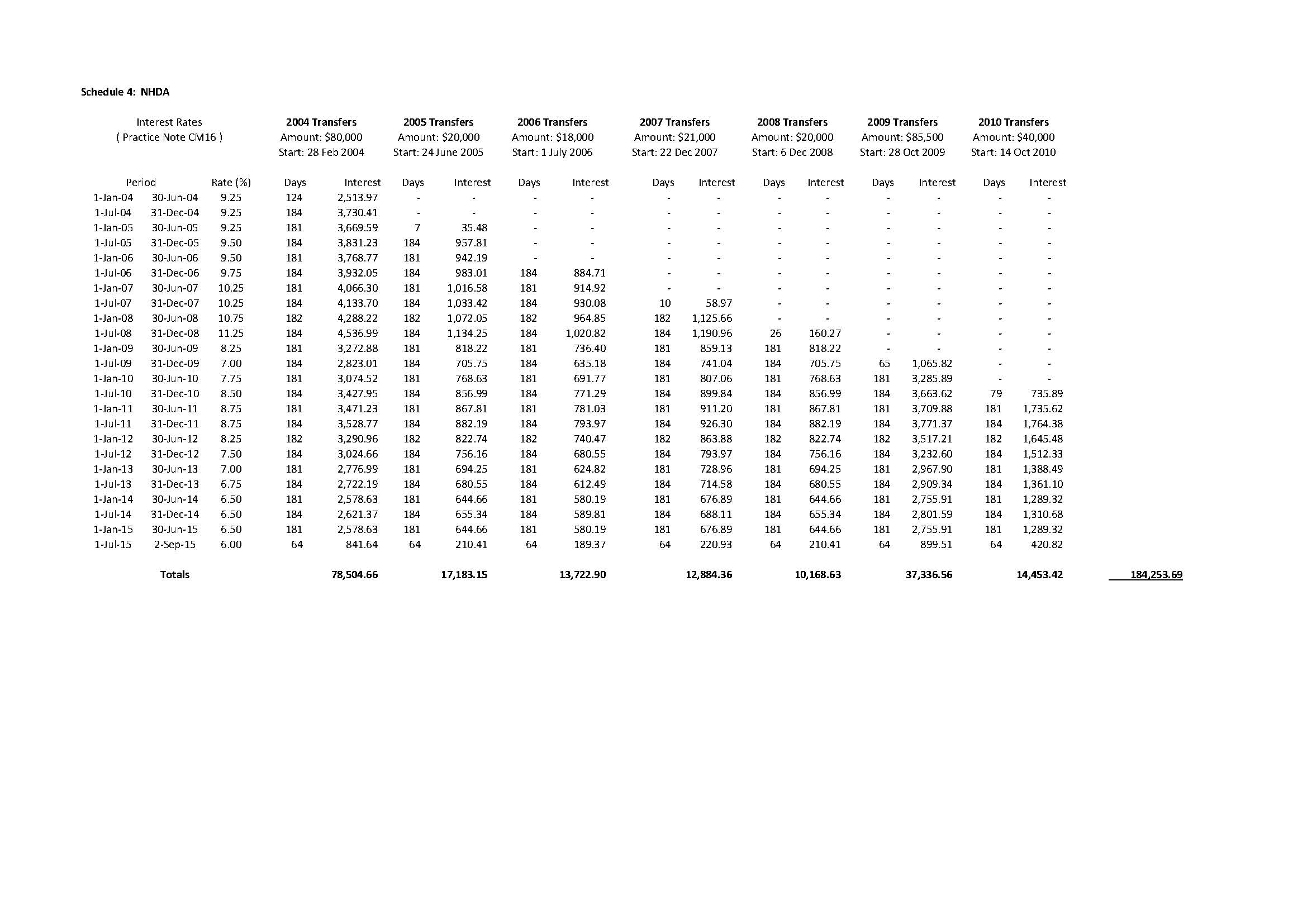

Pre-judgment interest of $554,215.67 in the Victorian proceeding and $86,633.81 in the New South Wales proceeding.

Costs of $506,800 in the Victorian proceeding and $53,200 in the New South Wales proceeding.

3 The Union has asked the Court, when making any orders for interest and costs, to distinguish between amounts awarded in respect of the periods before and after 26 June 2015. It was on this day that Ms Jackson lodged a debtor’s petition under the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (“the Bankruptcy Act”). The Court was informed that issues may arise, in the administration of her estate or in other proceedings, which would require such a distinction to be made. Lest such issues arise, I will distinguish, in my reasons, between the relevant periods before and after Ms Jackson’s bankruptcy.

4 The Union’s written submissions were served on Ms Jackson. She has not filed any answering submissions. Her trustee in bankruptcy has advised the Court that, unless it is proposing to make any orders against him, he does not wish to be heard on the issues of interest and costs.

PRE-JUDGMENT INTEREST

5 Section 51A(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (“the FCA Act”) relevantly provides that:

“(1) In any proceedings, for the recovery of any money (including any debt or damages or the value of any goods) in respect of a cause of action that arises after the commencement of this section, the Court or a Judge shall, upon application, unless good cause is shown to the contrary, either:

(a) order that there be included in the sum for which judgment is given interest at such rate as the Court or the Judge, as the case may be, thinks fit on the whole or any part of the money for the whole or any part of the period between the date when the cause of action arose and the date as of which judgment is entered; or

(b) …”

6 This provision does not authorise the awarding of interest upon interest: see s 51A(2)(a).

7 Section 51A is “designed to compensate a successful applicant for the fact that he or she has been kept out of his or her due monetary entitlements … while his or her claims are made, litigated and determined”: see Kazar v Kargarian (2011) 197 FCR 113 at 136 (Foster J). If an order is sought under the section it will be made “unless good cause is shown to the contrary.” No such “good cause” has been demonstrated in these proceedings.

8 The Court has a broad discretion, under s 51A, “to award interest at such rate or rates as it thinks fit for such period or periods as it thinks fit on the whole or on part of the monetary award”: Kazar at 136. The Court’s Practice Note CM 16 advises litigants that they should expect that the Court will have regard to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s cash rate plus 4% (adjusted at six monthly intervals on 1 January and 1 July each year) when calculating interest to be paid under s 51A(1)(a).

9 I consider that it is appropriate to adopt these rates in calculating pre-judgment interest in the present proceedings.

10 The Union has undertaken the calculations using the guidance provided by Practice Note CM 16. It has also made a series of adjustments which are wholly favourable to Ms Jackson’s interests in order to take account of reductions in compensation claimed and the periods to which the deductions are attributable.

11 The Union’s calculations and the methodology it employed are explained in its written submissions. A copy of the relevant part of the submissions is Attachment A. These calculations support the claims made for pre-judgment interest in each proceeding and I accept them.

12 The orders sought in each proceeding will be made.

13 Of the $554,215.67 to be awarded in the Victorian proceeding, $543,040.06 is attributable to the period up to 26 June 2015 and $11,175.61 to the period between 27 June and 2 September 2015.

14 Of the $86,633.81 awarded in the New South Wales proceeding, $82,122.73 is attributable to the period up to 26 June 2015 and $4,511.08 to the period between 27 June and 2 September 2015.

COSTS

15 The Union has applied for a lump sum costs order to be made in each proceeding.

Can a costs order be made?

16 An issue arises immediately as to whether or not the Court has power to accede to this application.

17 The Union’s consolidated statement of claim raised seven broad claims. All, save one, alleged contraventions of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) (“the FWRO Act”), the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“the Corporations Act”) and the common law. Each of these causes of action were founded on the same factual substratum. The remaining claim, that relating to overpayment of wages, was upheld on equitable grounds but I would have also found liability for contraventions of both the FWRO Act and the Corporations Act.

18 Section 43 of the FCA Act confers on the Court a broad and unfettered discretion to award costs in proceedings coming before it. The power is subject to certain express qualifications which include the provisions of s 570 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (“the FW Act”). The broad power is not, however, expressly qualified by reference to either the FWRO Act or the Corporations Act.

19 These two Acts do, however, contain provisions touching on the scope for successful parties to obtain costs orders.

20 Section 329(1) of the FWRO Act provides that:

“A person who is a party to a proceeding (including an appeal) in a matter arising under this Act must not be ordered to pay costs incurred by any other party to the proceeding unless the person instituted the proceeding vexatiously or without reasonable cause.”

21 Section 1335(2) of the Corporations Act provides that:

“The costs of any proceeding before a court under this Act are to be borne by such party to the proceeding as the court, in its discretion, directs.”

22 The Union submitted that, in the circumstances of the present proceedings, s 329(1) of the FWRO Act did not operate to prevent the Court from making the costs orders which it sought. This was because the proceedings involved matters which arose under another Commonwealth Act which contained no constraint on the awarding of costs and at common law.

23 The Union relied on two Full Court decisions of this Court. They were Bahonko v Sterjov (2008) 166 FCR 415 and Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (No 2) (2013) 209 FCR 464.

24 In Bahonko two applications had been consolidated. In the first the applicant alleged, pursuant to s 170CP(1) of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (“the WR Act”), contraventions by the respondents of other provisions of that Act. The second was an application, brought pursuant to s 46PO(1) of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (“the HREOC Act”), in which she alleged unlawful discrimination against her under the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

25 Section 170CS(1) of the WR Act constrained the power of the Court to award costs in proceedings brought under s 170CP. It provided that:

“Subject to this section, a party to a proceeding under section 170CP must not be ordered to pay costs incurred by any other party to the proceeding unless the court hearing the matter is satisfied that the first-mentioned party:

“(a) instituted the proceeding vexatiously or without reasonable cause; or

(b) caused the costs to be incurred by that other party because of an unreasonable act or omission of the first-mentioned party in connection with the conduct of the proceeding.”

26 There were no similar costs constraints in the HREOC Act.

27 The Full Court held that the trial judge had not erred when he apportioned costs between the two causes of action and awarded the successful respondents half of the costs which they had incurred. The Full Court explained its reasons (at 424-5) as follows:

“The question whether costs with respect to separate federal claims within the original jurisdiction of the Court are affected by the restrictions on the award of costs appearing in the WR Act has not received prior attention by a Full Court. In Seven Network 148 FCR 145 it was held that separate federal proceedings are not shielded from costs by s 347 of the WR Act (now s 824) notwithstanding earlier decisions of the Court to the effect that common law causes of action heard together with claims under the WR Act were so protected (see eg Maritime Union of Australia v Geraldton Port Authority (No 2) (2000) 94 IR 404 at [61]-[70] and the cases there referred to). Seven Network 148 FCR 145 was followed by the primary judge in the decision under appeal and in McDonald v Parnell Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] 164 FCA 2086.

A separate federal claim does not come before the Court in its ‘accrued’ or ‘associated’ jurisdiction. It stands on its own, even if for convenience it is consolidated with other claims within the Court's jurisdiction for the purpose of hearing. The ordinary principles concerning costs apply in the absence of a statutory restriction applying to those proceedings. Such a restriction does not, in our view, arise from the administrative act of consolidating separate federal proceedings for hearing.

In any event, so far as the present case is concerned we see no room for argument about the point. So far as s 170CS(1) of the WR Act (as it then was — see now s 666) is concerned, what was restricted was an award of costs in ‘a proceeding under section 170CP’ (now s 663). No protection was given by s 170CS(1) to proceedings under the HREOC Act. Although it may be accepted that after consolidation the proceedings were, as the trial judge said, ‘wholly undifferentiated’ that did not mean that the HREOC Act proceedings had become completely subsumed within the WR Act proceedings or vice versa. The extent to which that might happen in any particular proceedings would require assessment according to the circumstances of an individual case.

In the present case the trial judge took the view that ‘justice would be done’ and that true costs with respect to the HREOC Act claims would be reflected if half of the costs incurred subsequent to consolidation were awarded. Unless there was a legal bar to such a course that part of the primary judge's award of costs involved the exercise of a judicial discretion. No basis has been offered to interfere with it. The only contention advanced by the appellant was that the award of costs was contrary to the WR Act. We reject that contention.”

28 Bahonko was followed by a second Full Court in the CFMEU case. In this case claims had been made under both the WR Act and the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Act 2005 (Cth) (“the BCII Act”). Section 824 of the WR Act provided that:

“(1) A party to a proceeding (including an appeal) in a matter arising under this Act (other than an application under section 663) must not be ordered to pay costs incurred by any other party to the proceeding unless the first-mentioned party instituted the proceeding vexatiously or without reasonable cause.

(2) Despite subsection (1), if a court hearing a proceeding (including an appeal) in a matter arising under this Act (other than an application under section 663) is satisfied that a party to the proceeding has, by an unreasonable act or omission, caused another party to the proceeding to incur costs in connection with the proceeding, the court may order the first-mentioned party to pay some or all of those costs.

(3) In subsections (1) and (2):

costs includes all legal and professional costs and disbursements and expenses of witnesses.”

29 As can be seen s 824(1) is in substantially the same terms as s 329(1) of the FWRO Act. The latter Act does not, however, contain a qualification of the kind which is found in s 824(2). As a result the proscription is not modified so as to allow an award of costs having regard to the conduct of the proceeding after it has been instituted.

30 One of the issues which fell to be determined by the Full Court was whether s 824 of the WR Act operated to prevent the award of costs against the unsuccessful respondent. The Full Court, following Bahonko, held that, in a case in which a common substratum of facts gives rise to causes of action under two Acts, one of which contains a proscription on the award of costs and the other which contains no such constraint, “the equality of the statutory regimes [and] the principle of their harmonious operation” requires that the claims made under the Act which permitted the awards of costs “should be treated as constituting one half of the proceeding”: see at 485. The “harmonious operation” principle, to which the Full Court referred, was a principle of statutory construction. The principle required that two or more pieces of legislation, having the same constitutional or legislative source, should be read, where possible, in a way which avoids conflict and enables them to operate concordantly (see at 484).

31 The Full Court reached these conclusions having undertaken an extensive review of authorities, both in Full Courts and first instance, in this Court. As the Full Court noted in Melbourne Stadiums Limited v Sautner (2015) 229 FCR 221 at 253:

“This review disclosed conflicting lines of authority. One line held that, in a proceeding in which claims were made under the Workplace Relations Act and its predecessors and also under other Commonwealth legislation or at common law, s 824 and its predecessors operated to prevent any award of costs in that proceeding. The alternative line of authority held that it was possible to treat causes of action based on the Workplace Relations Act separately from any other claims. The costs restriction applied to the former but not the latter.”

It is also relevant, for present purposes, to note that, in some of these authorities, causes of action were pleaded under both the WR Act and State legislation and common law. In some of these cases, in which it had been held that s 824 or its forerunners did not preclude the awarding of costs, an apportionment had been made having regard to factors such as the amount of hearing time allocated to factual issues which did not bear on any claim made under the WR Act.

32 This is not the occasion to seek to reconcile (if this is possible) the many conflicting decisions on the construction and application of s 824 and its predecessors. Sitting as a single judge I consider myself to be bound by the most recent and considered judgment of the Full Court, that being the decision in CFMEU. That decision is directly on point given that it involved causes of action, pursued in reliance on provisions of two Acts of the Commonwealth Parliament, which were based on the same substratum of facts. The present is such a case. Save as to one of its claims, the HSU has relied on causes of action under both the FWRO Act and the Corporations Act. Section 329(1) of the former Act precludes the Court from awarding costs in matters arising under the FWRO Act subject to certain irrelevant exceptions. The latter Act however confers on the Court a discretion to award costs in any proceeding brought under it. The other claim was for money had and received. The time taken to deal with this matter was relatively short and added little to the length of the hearing. As a result I do not consider that any particular allowance should be made for it.

33 Subject to some matters, to which I will shortly turn, the appropriate order in the present proceedings is that Ms Jackson pay one half of any lump sum which the Court considers should be awarded to the Union and would be awarded to it but for s 329 of the FWRO Act.

34 The Union sought to submit that CFMEU stood for a broader proposition, one which left the wide discretion, conferred by s 43 of the FCA Act effectively undisturbed, save that “the expression of the legislative will” in s 329 was to be taken into account in the exercise of the discretion. As a result the Court could, in an appropriate case, award a successful party its costs in a proceeding in which contraventions of the FWRO Act had been pleaded and established, notwithstanding the provisions of s 329(1).

35 I do not accept these submissions. The Full Court in CFMEU was concerned to ensure that two Commonwealth Acts were read and applied harmoniously. In order to do this it was necessary, not merely to bring into account, but to give effect to the statutory proscription, contained in one of the Acts, against the awarding of costs. The award of full or substantial costs would have accorded paramountcy to one Act over the other rather than promote their concordant operation.

The Calderbank offer

36 On 26 March 2015 the Union made an offer to Ms Jackson to settle the proceedings. The Union offered to compromise its claims in both proceedings (including claims for compensation, interest and costs) upon payment, by Ms Jackson, of $1,250,000. If Ms Jackson accepted the offer, the Union proposed that the proceedings be discontinued with no order as to costs. The offer was made in writing and was open for 14 days. It was made three days after Ms Jackson had filed her amended defence. The Union foreshadowed an application for indemnity costs in the event that its offer was not accepted. The offer was not accepted.

37 In the principal judgment, delivered on 19 August 2015, orders were made that Ms Jackson pay the Union a total of $1,406,538, exclusive of interest.

38 The Union contends that the offer it made in March was reasonable and that Ms Jackson’s failure to accept it was unreasonable. It submits that it should be awarded costs on an indemnity basis for costs and disbursements incurred after 26 March 2015.

39 The offer was a Calderbank offer.

40 It was expressed to have been made “in accordance with the principles enunciated in Calderbank v Calderbank [1975] 3 All ER 333”. Such an offer has the potential to cause costs to be awarded on an indemnity basis. It has long been accepted that costs will ordinarily follow the event and that a successful litigant will receive costs in the absence of special circumstances which justify the making of some other order: see Ruddock v Vadarlis (No 2) (2001) 115 FCR 229 at 234 (per Black CJ and French J). The “ordinary rule” recognises that a successful party would have incurred costs in prosecuting or defending the proceeding and is entitled to be compensated. Such compensation will normally be paid on a party-party basis.

41 A departure from the ordinary position that costs follow the event may be warranted where there has been an unreasonable rejection of a Calderbank offer. The departure may involve the award of indemnity costs to the offeror.

42 In Calderbank the Court of Appeal held that the successful party who had been awarded £10,000 should only have his costs up to the point at which he had rejected an offer from the other party which exceeded in value that which had been obtained by the order of the Court. Thereafter the unsuccessful party was to have her costs paid by the successful party.

43 The decision in Calderbank gave effect to the policy that the parties to litigation should seriously consider, and not lightly reject, offers made by another party with a view to compromising their dispute and avoiding a trial or the continuation of a trial: see Alpine Hardwoods (Aust) Pty Ltd v Hardys Pty Ltd (No 2) (2002) 190 ALR 121 at 125 (Weinberg J).

44 In later cases the Calderbank principles were developed. As a result of these developments the position now is that, depending on the circumstances of the case, an unreasonable refusal of a Calderbank offer may justify the award of costs on an indemnity basis from the date of rejection: see Black v Lipovac (1998) 217 ALR 386 at 432-3.

45 Any Calderbank offer must be “couched in such terms as enable the offeree to make a carefully considered comparison between the offer made and the ultimate relief it is seeking in all its aspects”: see Dr Martens Australia Pty Ltd v Figgins Holdings Pty Ltd (No 2) [2000] FCA 602 at [24] (per Goldberg J). Where a Calderbank offer includes a provision relating to costs it is necessary for the offeror to isolate “the term as to costs in a way which is clear and capable of proper assessment independently of the principal claim …”: see Perry v Comcare (2006) 150 FCR 319 at 334 (Greenwood J). Offers which are expressed to be “inclusive of costs” or “all-up” may be insufficiently precise: see, for example, Smallacombe v Lockyer Investment Company Pty Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 97 at 102 (Spender J) where his Honour was concerned that “all-up” offers would “tend against lean litigation” because such offers would have the tendency “over time, [to] reward the firm whose costs were ‘padded’ although still recoverable on a party and party basis, and [would] disadvantage those firms who conducted litigation with tight efficiency.” On the other hand an offer which proposes that each party bear its own costs or that a particular sum be paid “plus costs” have been accepted as proper offers: see, for example, Cutts v Head [1984] Ch 290 at 299 (Oliver LJ); Alpine Hardwoods at 125.

46 Once a viable offer is made and it is not accepted by the offeree, the offeror who seeks indemnity costs bears the onus of establishing that the offeree’s refusal or non-acceptance was unreasonable or imprudent. The reasonableness of the refusal or non-acceptance must be determined in the light of the circumstances that existed at the time that the rejection or failure to accept occurred.

47 In GEC Marconi Systems Pty Ltd v BHP Information Technology Pty Ltd (2003) 201 ALR 55 at 63-4 Finn J said that:

“The reasonableness of the rejection of an offer is to be considered in light of the circumstances which existed at the time of the rejection. And, relevant in that consideration are the terms of the offer and the circumstances of the litigation, ‘including the time at which the offer is made and the understanding of the parties as to the strengths and weaknesses of their respective cases’.”

48 The authorities support the proposition that restraint is to be exercised in awarding costs on an indemnity basis. In particular, such orders should not be made for a punitive purpose. In Hamod v New South Wales (2002) 188 ALR 659 at 665 Gray J (with whom other members of the Court agreed) cautioned that:

“Indemnity costs are not designed to punish a party for persisting with a case that turns out to fail. They are not awarded as a means of deterring litigants from putting forward arguments that might be attended by uncertainty. Rather, they serve the purpose of compensating a party fully for costs incurred, as a normal costs order could not be expected to do, when the court takes the view that it was unreasonable for the party against whom the order is made to have subjected the innocent party to the expenditure of costs.”

49 The offer made by the Union to Ms Jackson was, in my view, a reasonable offer. It was made, having regard to the then latest iteration of Ms Jackson’s defence, and the basis for it was fully explained in the letter containing the offer. The Union drew Ms Jackson’s attention to the manifest deficiencies in her defence. The sum proposed was less than the amount sought by way of compensation and no account was made for judgment interest. Had Ms Jackson accepted the offer each party would have borne its own costs. In all the circumstances her failure to accept it was unreasonable.

50 The offer was expressed to be open for 14 days, that is, until 9 April 2015. Ms Jackson was entitled to have the benefit of this period within which to consider her position and make an informed response to the offer. While the Union is entitled to an order that its costs be paid on an indemnity basis they should only be so paid on and after 9 April 2015. It will be necessary to return to this matter when fixing the quantum of costs to be paid.

Should a lump sum order be made?

51 The power to award lump or gross sum costs is intended, in appropriate cases, to avoid the expense, delay and aggravation involved in the taxation of costs and challenges to such taxation: see Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2007] FCA 2059 (Sackville J); Harrison v Schipp (2002) 54 NSWLR 738 at 742 (Giles JA); Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd (No 3) [2014] FCA 949 at [33] (Murphy J). Although it has been said that this power is particularly suited to “complex litigation”, the rule is not so confined. The power is available “whenever the circumstances warrant its exercise”: see Harrison at 742; Sony Entertainment Australia Limited v Smith (2005) 215 ALR 788 at 812 (Jacobson J).

52 The present proceeding can, fairly, be characterised as complex. The proceedings took almost two years to come to trial. This was because there were no fewer than 19 interlocutory applications and directions hearings. Among the matters which had to be dealt with were numerous defaults on the part of Ms Jackson, the making of additional claims by the Union when further information came to hand and applications for adjournments. As already noted the Union relied on seven broad claims and multiple causes of action. The hearing continued over three days.

53 On the eve of the trial Ms Jackson filed a debtor’s petition under s 55 of the Bankruptcy Act. Her debtor’s petition and an affidavit sworn by her disclosed nett assets of the order of $300,000.

54 Given that this sum is wholly inadequate to meet the compensation orders already made by the Court, an issue arises as to whether the Union should have to bear the costs of taxation before it has the benefit of an order that it be paid an ascertainable sum by way of costs.

55 A costs consultant, engaged by the Union, advised that:

It would take approximately 105-125 hours to prepare a bill of costs in taxable form. This would take approximately 11 weeks to complete.

If half of the items in the bill of costs gave rise to objections, the bill would take approximately five days to tax.

The cost to the Union of drawing a bill of costs would be between $33,495 and $39,875.

The total cost to the Union, if a fully contested taxation occurred, would be between $55,935 and $62,315.

56 The Union would have little, if any, prospect of recovering any of this money. Any taxation would have to involve Ms Jackson’s trustee, assuming that he had sufficient funds available to him to participate.

57 In these circumstances I do not consider that the Union should be put to any further expense in relation to the proceedings. A lump sum costs order is appropriate and should be made.

What amount should be ordered?

58 The Union sought a lump sum costs order of $560,000. This figure was proposed having regard to the sums which the Union was likely, in the opinion of an experienced litigation solicitor, to have recovered on taxation on a party and party basis and on an indemnity basis.

59 In calculating lump sum costs the Court does not proceed as if it were undertaking taxation. The authorities which guide the estimation process were summarised by Finn J in Ginos Engineers Pty Ltd v Autodesk Australia Pty Ltd (2008) 249 ALR 371 at 377:

“22 Rules of court such as r 21.02(2)(a) of the FMC Rules and O 62 r 4(2)(c) of the Federal Court Rules, which empower a court to order a gross amount in costs instead of an amount determined after taxation, are well accepted as being directed to the avoidance of expense, delay and the protraction of litigation, whether the case be a complex or a simple one: see Beach Petroleum NL v Johnson (No 2) (1995) 57 FCR 119 at 120 ; 135 ALR 160 at 162 (Beach Petroleum NL); Australasian Performing Rights Assn Ltd v Marlin [1999] FCA 1006; Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd v Ninox Television Ltd [2006] FCA 1046 (Nine Films & Television); see generally on fixing of costs by courts, G E Dal Pont, Law of Costs, Butterworths, Sydney, 2003, para [15.14] and following and R Quick and D J Garnsworthy, Quick on Costs, looseleaf, LBC Information Services, Sydney, para [6.20].

23 It is inconsistent both with the terms of r 21.02(2)(a) and to the clear objective in making a lump sum order that the costs in issue be subjected to the detailed scrutiny often applied in taxations: Leary v Leary [1987] 1 All ER 261 at 265; Dal Pont, 2003, paras [15.17] and [15.19]. In specifying a lump sum, it is well accepted that it is appropriate to apply a ‘much broader brush’ than would be applied on a taxation: see Sony Entertainment (Australia) Ltd v Smith (2005) 215 ALR 788 ; 64 IPR 18 ; [2005] FCA 228 at [196]-[200] (Sony Entertainment). Nonetheless, the discretion to make a lump sum order, no less than the general discretion to order costs, must be exercised judicially and in accordance with principle. In particular in making a lump sum estimate the approach of the court should be ‘logical, fair and reasonable’: Beach Petroleum NL at CLR 123; ALR 164; Nine Films & Television at [8].

24 It is not uncommon, particularly, but not only, in intellectual property cases, for the court to take as its starting point the evidence of the charges for professional costs incurred and disbursements made by the lawyers of the party awarded costs -- and this irrespective of whether the costs are to be estimated on an indemnity basis: compare Beach Petroleum NL at CLR 120; ALR 162; or on a party and party basis: compare Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Miyamoto [2003] FCA 812 at [29] and following. That figure is then characteristically adjusted to take account of the acceptability of the charges made, the conduct of the proceeding, the measure of success on issues and so on, to produce a sum which as a matter of judgment is neither overcompensatory nor prejudicial to the successful party. Consistent with the broad brush approach, that adjustment ordinarily is effected through the application of a discount to the figure accepted by the court on the available evidence as appropriately reflecting actual professional costs charged and disbursements made. The case law evidences wide variations in the percentages of discount sought and/or applied to reflect the exigencies of the matter in question: compare Sony Entertainment, 60%; Beach Petroleum NL, 39%, Nine Films & Television, 23%. What is clear is that a lump sum award may be in an amount that is greater or smaller than would have been the taxed costs payable: see Dal Pont, 2003, para [15.20].”

60 The Court strives to achieve an outcome that is “logical, fair and reasonable”. This will require avoidance of overestimation of recoverable costs on the one hand and avoiding “underestimating the appropriate amount, for example by applying an arbitrary discount to the amounts claimed” on the other: Seven Network at [25].

61 The Union’s solicitor has deposed that its costs, in prosecuting the proceedings, amounted to $1,096,925.89 (including GST). Of this sum $534,508.32 (excluding GST) was incurred prior to 26 March 2015 and $466,891.16 (excluding GST) was incurred thereafter.

62 The calculation of the lump sum figure sought by the Union was based on the evidence of the experienced litigation solicitor who gave evidence as follows:

“21 Based on my experience as a legal practitioner it is likely that a successful party in a Federal Court proceeding will recover in the range of:

(a) 50-60% of its costs if an order is made on a party and party basis; and

(b) 70-80% of its costs if an order is made on an indemnity basis.

22 If the lower end of the above percentages are applied to costs of this proceeding the Union would be entitled to:

(a) $267,254.16 for its costs up to and including 26 March 2015 (being 50% of $534,508.32); and

(b) $326,823.81 for its costs from 27 March 2015 to the date of final orders (being 70% of $466,891.16).”

63 As Finn J held in Ginos Engineers, the normal starting point for the calculation of a lump sum compensation order is the actual professional costs charged to a successful client. A discount is then to be applied. The discount is to be fixed having regard to a range of considerations, including those identified by his Honour. The Court will strive to avoid overcompensation of the successful party. The figure produced by the discount may, in a given case, be greater or less than the figure which the evidence suggests might be awarded on taxation.

64 In the circumstances of the present case, including the substantial success of the Union in both proceedings and the conservative estimates made of the amounts of costs likely to be recoverable on taxation, I consider that a discount of 35% is appropriate. In fixing this figure I have had regard to the need to reduce the period during which indemnity costs are properly claimable by 14 days and extending the period during which party and party costs would be payable by the same number of days.

65 Applying the discount which I consider to be appropriate the resultant figure is $713,001. For the reasons which I have already given I consider that the decision of the Full Court in CFMEU requires that only half of that figure can be awarded having regard to the proscription in s 329(1) of the FWRO Act. As a result I consider that a lump sum costs order of $356,500 should be made in favour of the Union. It will be convenient to make that order in the Victorian proceeding and to make no order in the New South Wales proceeding which was heard in conjunction with it.

66 The proportion of total costs incurred after the lodgement of the debtor’s petition was 10.11%. Of the $356,500 to be awarded, $320,457.85 is attributable to the period up to 26 June 2015 and $36,042.15 to the period between 27 June and 2 September 2015.

I certify that the preceding sixty-six (66) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Tracey. |

Associate:

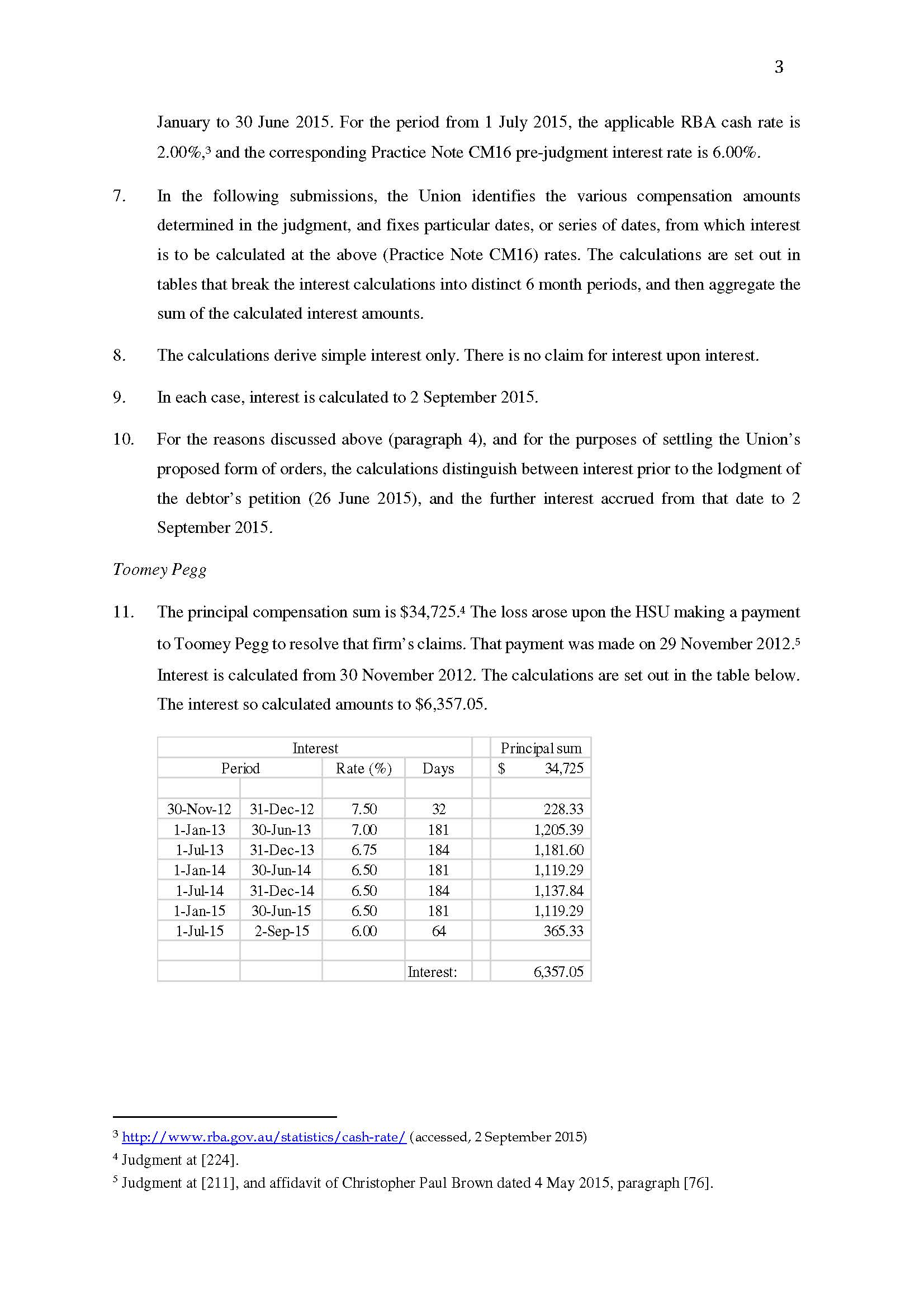

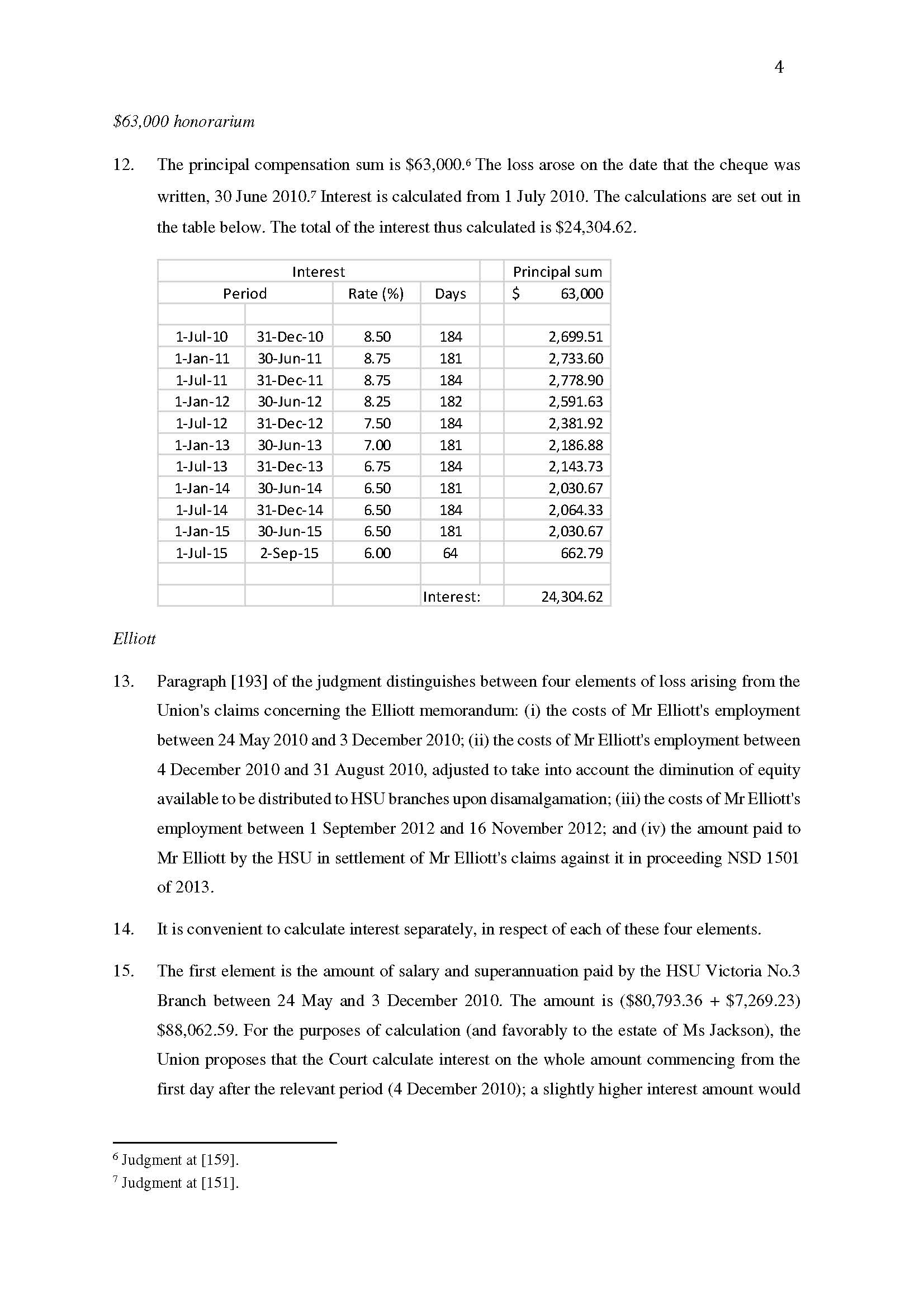

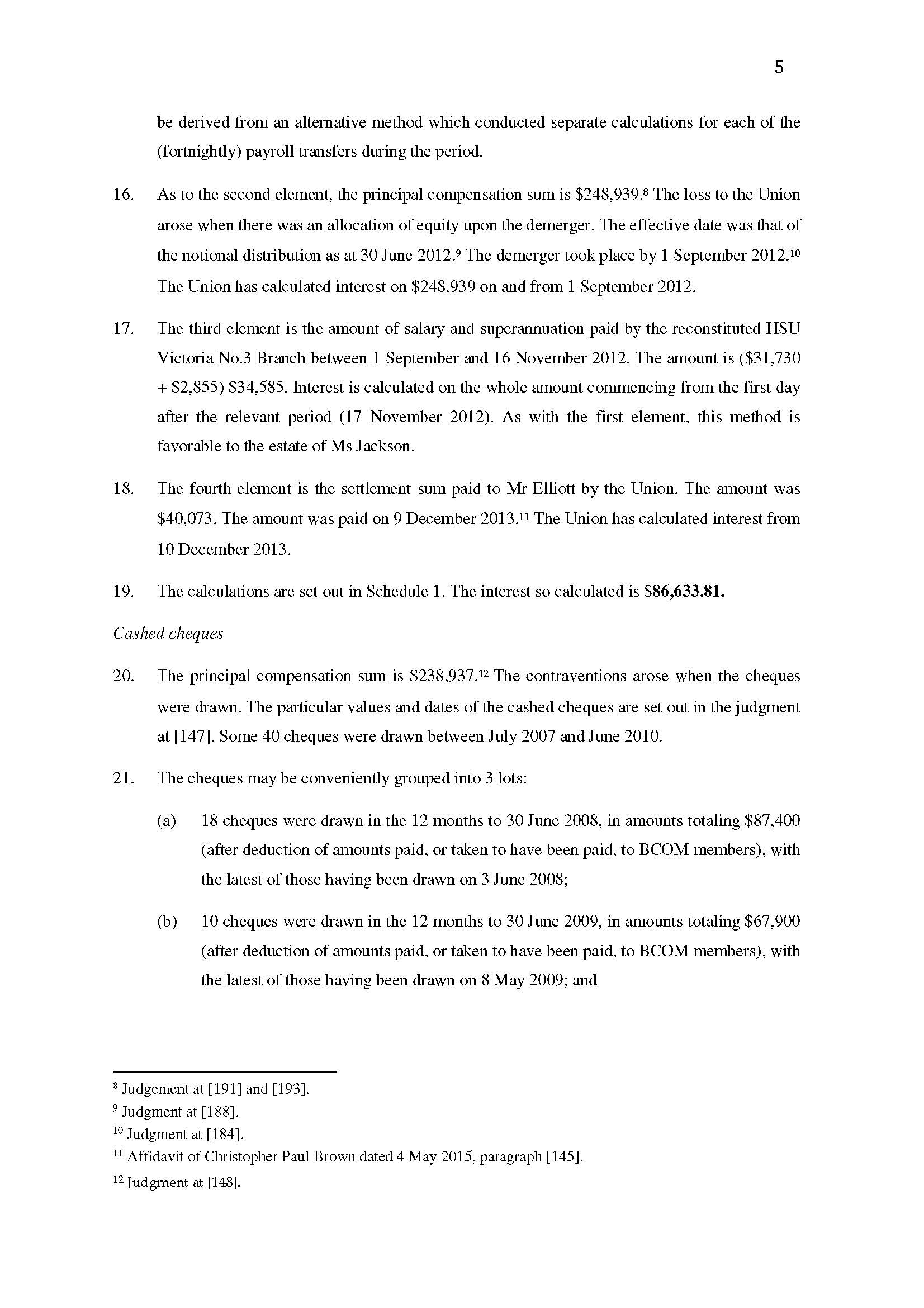

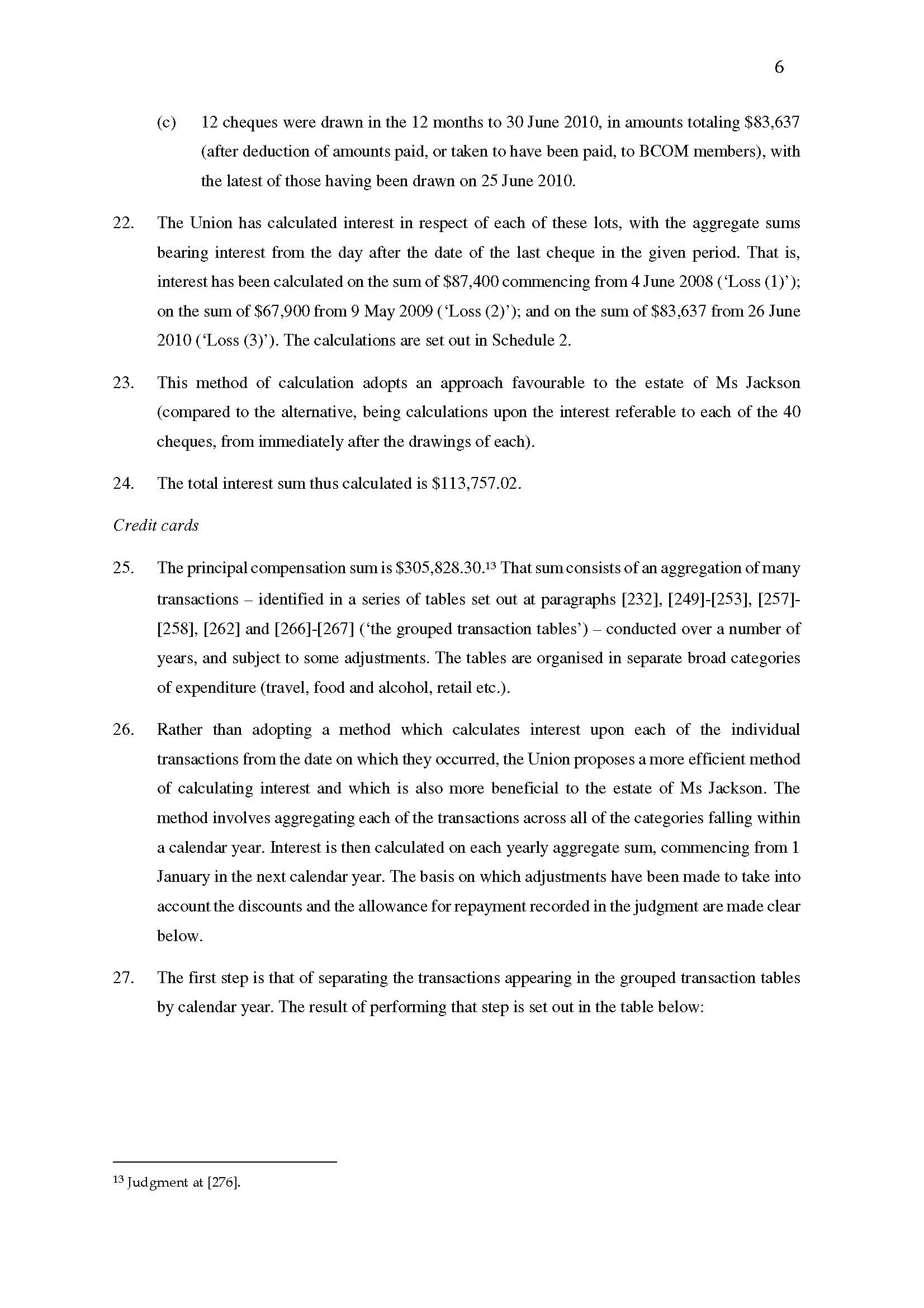

ATTACHMENT A