FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Midland Hwy Pty Ltd (administrators appointed); in the matter of Midland Hwy Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) [2015] FCA 1360

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

IN THE MATTER OF MIDLAND HWY PTY LTD (ACN 153 096 069) (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED)

DATE OF ORDER: | 3 December 2015 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Under s 447A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), Part 5.3A of the Act shall operate in relation to Midland Hwy Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (Midland) so that:

(a) the resolution of creditors of Midland at a meeting on 21 October 2015 that Midland execute a deed of company arrangement be set aside ab initio and that Part 5.3A have operation as though that creditors’ resolution failed to pass at that meeting;

(b) the administration of Midland come to an end;

(c) Midland be wound up;

(d) Nicholas Martin and Craig Crosbie be appointed as liquidators of Midland with all relevant statutory powers given to liquidators under the Act.

2. ASIC’s costs of and incidental to its application be costs in the winding up of Midland, but otherwise there be no order as to costs.

3. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 668 of 2015 |

IN THE MATTER OF MIDLAND HWY PTY LTD (ACN 153 096 069) (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED)

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff |

AND: | MIDLAND HWY PTY LTD (ACN 153 096 069) (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) First Defendant BILKURRA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD (ACN 097 182 182) Second Defendant |

JUDGE: | BEACH J |

DATE: | 3 December 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 21 October 2015, a resolution was passed at the second meeting of creditors of Midland Hwy Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (Midland) that it execute a deed of company arrangement (DOCA) embodying a proposal propounded by Bilkurra Investments Pty Ltd (Bilkurra).

2 ASIC has sought orders pursuant to s 447A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) setting aside that resolution and winding up Midland. Such orders are not opposed by Midland and its administrators, but they are opposed by Bilkurra.

3 ASIC has relied on various affidavits of Rosemaree Prendergast sworn on 23 October 2015, 29 October 2015 and 10 November 2015. The second Prendergast affidavit also annexes three further affidavits filed in other proceedings. I have given ASIC leave to rely upon such affidavits in the present application. Bilkurra has relied upon an affidavit of Ian Stephens, its director, affirmed on 30 October 2015; Mr Stephens was cross-examined.

4 ASIC’s application has arisen in the following circumstances:

(a) ASIC has investigated a “land banking” scheme known as Hermitage Bendigo. Midland was the former developer of Hermitage Bendigo, the current developer of which is Bilkurra. A typical land banking scheme is a real estate investment scheme involving the acquisition of large blocks of land by the promoter of the scheme, often in undeveloped rural areas, who then offers portions of such land to retail investors. The land banking company promotes the investment with representations of high potential returns if the land is rezoned and redeveloped. Investors may purchase a lot in the land or acquire an option to purchase such a lot, usually in and from an unregistered plan of subdivision.

(b) In the present case approximately 700 retail investors entered into option deeds with Midland in order to participate and invest in Hermitage Bendigo in circumstances where apparently misleading representations were made to them. Midland raised approximately $24 million from such investors. That sum, initially held in the trust account of Evans Ellis Lawyers (EEL), was paid by EEL to Project Management (Aust) Pty Ltd (PMA), an entity controlled by Michael Grochowski. Bilkurra was the owner of the land the subject of the scheme at the time the option deeds were entered into. In fact it is still the owner of the relevant land. Midland has subsequently purportedly assigned its rights under the option deeds to Bilkurra. There is an issue as to the effectiveness of such assignments; in any event, as the assignments were not novations, they could not effect an assignment of Midland’s liabilities to such retail investors. ASIC has contended that the purported assignments were void or voidable by reason of the following matters:

(i) Midland’s contractual right of assignment was conditional upon the provision of ten days’ notice to investors; notice in that time frame was apparently not provided;

(ii) Midland was insolvent at the time of the relevant transaction. Further, Midland purported to assign its rights under the option deeds for no or no significant consideration and without recovering the $1.4 million it had previously paid in respect of the relevant land;

(iii) Further, the assignment of Midland’s rights was effected by Grochowski (acting for Midland pursuant to a power of attorney and as a de facto director) and EEL. There were various conflicts of interest involved. Arguably, the transaction was in breach of trust or fiduciary duty.

(c) Further, the retail investors being the option holders have claims against Midland for misleading misrepresentations in relation to the promotion of the investment by or on behalf of Midland.

(d) Further, the administrators’ investigations have disclosed a number of issues requiring further investigation and potential recovery proceedings, including $22.3 million in payments made by Midland that are likely to be voidable transactions and recoverable on the application of a liquidator if one is appointed.

(e) Further, the DOCA proposed by Bilkurra and advocated for by EEL provides no real commercial benefit to creditors (in particular option holders) of Midland and is insufficiently certain in respect of the rights of such creditors. Moreover, Bilkurra has represented to investors that entry into the DOCA was required to preserve their interest in the Hermitage Bendigo development in circumstances where Bilkurra’s financial position was uncertain. In any event, the DOCA was not the only means by which Bilkurra could enter into arrangements with investors directly so as to purportedly “preserve their interest”.

(f) Finally, Midland is insolvent and ought to be wound up to enable a liquidator to conduct the necessary investigations and deal fairly with all creditors. Midland is without funds to repay the $24 million in option fees owing to option holders as creditors of Midland.

5 In summary, ASIC has asserted that the present case is one of serious misconduct by Midland, Bilkurra, EEL, Benjamin Skinner, a partner of EEL, Grochowski and other related entities and individuals involving some $24 million received from retail investors and now missing. It asserts that there are serious questions that require a full investigation by an independent insolvency practitioner, i.e. a liquidator. It asserts that claims on behalf of Midland against third parties, which will ultimately be for the benefit of the investors, need to be pursued. Contrastingly, it submits that the DOCA propounded by Bilkurra eliminates the prospect of such steps occurring and in effect at least impedes a full investigation and recovery proceedings against the relevant entities and individuals involved. Generally, ASIC contends that it is in the public interest for the DOCA resolution to be set aside and for Midland to be wound up.

6 This matter came on for hearing before me on 30 October 2015. On that occasion, it was necessary to make an order in the following terms to suspend the operation of s 444B:

Pursuant to s 447A(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), until the hearing and determination of ASIC’s originating process dated 23 October 2015, Pt 5.3A of the Act is to operate as though the obligations of the administrators of Midland Hwy Pty Ltd under s 444B(5) of the Act do not operate.

7 In summary, I propose to grant ASIC’s application and to make an order under s 447A of the Act that Part 5.3A of the Act operate in relation to Midland so that:

(a) the resolution of creditors of Midland at a meeting on 21 October 2015 that Midland execute a deed of company arrangement be set aside ab initio and Part 5.3A have operation as though the creditors’ resolution failed to pass at that meeting;

(b) the administration of Midland come to an end;

(c) Midland be wound up; and

(d) Nicholas Martin and Craig Crosbie be appointed as liquidators of Midland with the powers given to liquidators specified in the Act.

8 I should note for completeness that in the alternative to the order referred to in [7(c)], I would have in any event been prepared to make orders in the following terms:

(a) First, under s 459P(1)(f) that ASIC have leave to apply for Midland to be wound up in insolvency;

(b) Second, under s 459A that Midland be wound up in insolvency.

9 The principal reasons for my determination are the following:

(a) First, Midland is insolvent. It has little in the way of assets but has substantial liabilities to the retail investors and third parties. Midland has no operating business. It appears to be a shell.

(b) Second, Midland has been used for shadowy purposes. Substantial transactions and money flows involving Midland ranging from $22.3 million to $24 million require full investigation. Such an investigation is more appropriately carried out by a liquidator rather than by ASIC. A liquidator will have a specific focus and appears likely to be funded by ASIC. Moreover, if action is to be taken in relation to any voidable transactions and their recovery, that would be done on the application of the liquidator (not ASIC) under s 588FF of the Act.

(c) Third, Bilkurra, the proponent of the DOCA, is substantially implicated in the transactions that in my view require full investigation, as are persons and entities associated therewith. Such persons and entities have an interest contrary to ASIC’s or any liquidator’s investigation and any proceedings that may be brought by a liquidator seeking to recover moneys or assets in relation to such voidable transactions. Bilkurra’s opposition to ASIC’s present application is to be seen in that light.

(d) Fourth, the proposal propounded by Bilkurra to the creditors of Midland is embryonic. Moreover, Bilkurra’s capacity to implement the same is doubtful. Indeed, Bilkurra’s own financial state is dubious to say the least.

(e) Fifth, it is doubtful whether the creditors of Midland who are the retail investors and option holders would receive any substantial benefit from the DOCA. Further, misleading representations were made to such creditors prior to their vote on the relevant resolution in order to procure their vote.

(f) Sixth, and generally, it is in the public interest that the administration of Midland come to an end and that Midland be wound up.

bilkurra, midland and $24 million of investors’ funds

10 Bilkurra was incorporated in 2001. From 2001 to 2011, Bilkurra was controlled inter alia by John Wood. Bilkurra was the registered proprietor of a parcel of land being lots 1 and 2, Midland Highway, Bagshot in Victoria (the land). Bilkurra had purchased the land in 2001 from John Wood.

11 Midland was incorporated on 7 September 2011. Although John Wood was the named sole director of Midland, Grochowski appears to have been the de facto or shadow director and the real controller of Midland. Subsequently, an “Appointment of Director Agreement” was entered into between John Wood, Grochowski and Midland which provided the following:

• John Wood is to be the registered director (to be paid a consulting fee).

• John Wood does “not have authority to act for or create or assume any responsibility or obligation on behalf of Midland HWY other than as authorised in writing by Michael (Mr Grochowski)”.

• Mr Grochowski [to have] a General Power of Attorney [for Midland].

• Mr Grochowski to hold John Wood’s Resignation of Director form and Company Resolution pending the removal of John Wood for whatever reason.

12 This arrangement was unusual to say the least. Grochowski was the real controller of Midland but remained in the shadows. He did not give evidence before me.

13 It appears that a power of attorney was also executed in favour of Grochowski on 7 May 2012 granted by Midland; I should also say that another undated power of attorney had also been executed in favour of Grochowski by Midland. In mid-2012, Grochowski was banned by ASIC from providing any financial services for a period of four years.

14 On 18 October 2011, Bilkurra agreed to sell the land to PMA, a company controlled by Grochowski. But on 10 November 2011, PMA nominated Midland as the purchaser of the land. Thereafter, between late 2011 and 19 June 2012, Midland paid $1.4 million to Bilkurra as part payment for the land, but Midland has never been the owner of the land. The sale contract(s) have apparently now been cancelled. Midland has not recovered any part of the $1.4 million.

15 In late 2011, Midland commenced selling option deeds and off-the-plan land sale contracts for parcels of the land. On 14 December 2011, PMA was appointed project manager for Midland. In 2012 and 2013, Property Direct (International) Pty Ltd (trading as 21st Century Property Direct) (Property Direct) sold options to purchase lots in the proposed development to external investors on behalf of Midland. The development, now known as Hermitage Bendigo, was marketed as “Acacia Banks”. Property Direct provided “marketing and promotional services” for Midland. Examples of the marketing and promotional material used by Property Direct on behalf of Midland included the following statements:

(a) “a ‘never seen before’ property investment opportunity that enables you to secure prime land for a measly, tiny fraction of what others could ever negotiate”;

(b) “a fool-proof plan to grab seven properties over twelve years worth potentially millions of dollars — without relying on the banks or unmanageable payments”;

(c) “potential to make $1.25m in return in 10 years time with the buy and hold strategy, or 125% return in two years if you want to sell out and cash it out early. Feel at ease, safe and secure with our no-risk exit strategy”.

16 Investors who were sold options by Property Direct entered into option deeds with Midland. The option deeds provided that Midland was not required to use the option fees to fund the development (cl 10.2) and that Midland was free to use such funds as it saw fit for any purpose whatsoever (cl 5.2). Clause 15.3 provided that if the contract(s) for the sale of the land were not completed for any reason, each option deed would come to an end and the option fees would be refunded within 120 days. Clause 17.4(c) provided that Midland may assign its rights and obligations under the option deeds provided that written notice thereof was given to the option holders within ten business days of the assignment. I will return to the provisions of clauses 15.3 and 17.4(c) later.

17 Midland received $24 million from option holders pursuant to such option deeds, $1.15 million from off-the-plan sales (held in EEL trust accounts) and bank guarantees of $433,000. At the least, the $24 million is now “missing” in the sense that its dispersal into the hands of third parties and use requires a full investigation (see the diagram I have set out at [50] below).

(a) Purported assignment of Midland’s rights under the option deeds and transfer of shares in Bilkurra to Greater Bendigo

18 In mid–2013, a number of agreements were entered into by the relevant parties including a deed of option to purchase shares, a deed of cancellation, a deed of assignment and a project management agreement. Apparently, the purpose of these transactions was to substitute Midland with Bilkurra as the developer of the land.

19 On 28 June 2013, Greater Bendigo Consolidated Pty Ltd (Greater Bendigo) was given an option to acquire all of the shares in Bilkurra pursuant to a share option deed executed by Bilkurra, Midland, PMA, Greater Bendigo and the shareholders of Bilkurra (namely, Chintri-Woodlands Estate Development Pty Ltd, Leong Kok Sau, John Wood Nominees Pty Ltd and Panorama TTT Pty Ltd). Greater Bendigo was incorporated on 11 June 2013 as a special purpose vehicle to acquire the Bilkurra shares. It appears that this related to a series of transactions under which it was contemplated that Bilkurra would then not complete the transfer of land to Midland but that Bilkurra would be substituted as the developer of the land.

20 Greater Bendigo agreed to pay to the former shareholders of Bilkurra $5.4 million for the Bilkurra shares if the option was exercised. The option was exercised by Greater Bendigo and such shares were transferred on 24 December 2013. EEL acted for Greater Bendigo. Skinner, a partner of EEL, became the sole director of Bilkurra at that time. I should say that throughout this time, EEL also acted for Midland. EEL was also the solicitor for Bilkurra and still so acts. Further, Skinner was a director between 11 June 2013 to 1 October 2014 of Greater Bendigo.

21 Generally, Skinner is, or was, a director of various companies with which Midland had dealings including regarding the land. Some of these dealings may constitute voidable transactions or be the subject of recovery proceedings at the hands of a liquidator. Mr Stephens has now replaced Skinner as a director of a number of these companies, including Bilkurra and Greater Bendigo.

22 Under the share option deed, Bilkurra also agreed to cancel the contract(s) of sale of the land with PMA (with Midland the nominee). As part of this transaction, and surprisingly, Midland agreed to pay a cancellation fee of $600,000 to Bilkurra in accordance with the deed of cancellation (cl 6 of the share option deed). I say surprisingly in light of the fact that the cancellation was being done for the benefit of and at the initiative of other entities and individuals. Clause 6 provided that Midland’s interest in the land was to be cancelled but the option deeds and contracts of sale it had entered into with third parties (the retail investors) remained valid and enforceable. Pursuant to clause 13 of the share option deed, the parties agreed that Midland would assign its rights, interests, benefits, obligations and liabilities in respect of the option deeds and contracts of sale entered into with the retail investors to Bilkurra by way of a deed of assignment. I should say at this point that in my view such an assignment was not validly effected. Further, the share option deed provided for a project management agreement to be entered into between Bilkurra and Greater Bendigo. Such an agreement was entered into on 28 June 2013 and provided that Bilkurra granted Greater Bendigo the exclusive right to develop and manage the project.

23 On 28 June 2013, a deed of release and cancellation (contemplated by the share option deed) was executed by Bilkurra, Midland and PMA by which the contract(s) for the sale of the land from Bilkurra to PMA (and its nominee, Midland) were cancelled. In addition to the $1.4 million it had already paid, Midland was required to pay the $600,000 cancellation fee referred to earlier as directed by Bilkurra. Midland paid $400,000 to PMA and $200,000 to John Wood. By reason of the cancellation of the sale of the land by Bilkurra ultimately to Midland, Midland thereby became liable under the option deeds to repay the $24 million that it had received from option holders. Accordingly as at the date of the second creditors’ meeting of Midland, the option holders were present creditors of Midland for that amount.

24 On 28 June 2013, a deed of assignment and consent (contemplated by the share option deed) was executed by Bilkurra and Midland. In consideration of Midland paying the cancellation fee to Bilkurra and Bilkurra terminating the contract(s) of sale, Midland purported to assign to Bilkurra all of Midland’s rights, interests, benefits, obligations and liabilities in respect of the option deeds and off-the-plan sale contracts and Bilkurra accepted that it would be liable to perform such deeds and contracts. Midland also agreed to provide written notice to the option holders and off-the-plan purchasers of the assignment within ten business days of the date of the assignment deed. The intention of these arrangements was that Bilkurra would assume all the rights and obligations of Midland in relation to the project, including stepping into the shoes of Midland with respect to the option deeds and off-the-plan sale contracts. As I say, the assignment in my view was not properly effected. In any event it did not act as a novation so Midland’s liabilities to the option holders remained with Midland.

25 On 24 December 2013, there was a deed of variation amending the share option deed allowing, inter alia, Greater Bendigo to borrow money and pledge Bilkurra’s land as security for the loan for Greater Bendigo to pay to the former shareholders of Bilkurra. John Wood purportedly signed this deed of variation. The deed of variation was also executed by Skinner on behalf of both Bilkurra and General Bendigo.

(b) Events following the death of Midland’s sole director and shareholder

26 On 28 July 2014, the sole director and shareholder of Midland, John Wood, died. Nevertheless, Grochowski appears to have continued to run Midland as a shadow/de facto director after this time or under the relevant power of attorney.

27 On 14 May 2015, John Wood’s son, Russell Wood, became aware that his father was the sole director and shareholder of Midland. Russell Wood, as the executor of his father’s estate, took steps to be appointed as Midland’s director on 26 May 2015. He then sought access to Midland’s books and records from EEL and Grochowski. Notwithstanding their previous central involvement in the affairs of Midland, neither EEL (Skinner) nor Grochowski provided any of Midland’s records or information to Russell Wood. It is somewhat surprising that EEL and Skinner should have so acted.

(c) The administration of Midland

28 On 2 July 2015, Midland, on the initiative of Russell Wood, appointed Craig Crosbie and Nicholas Martin of PPB Advisory as joint and several administrators of Midland. At the first meeting of creditors of Midland on 14 July 2015, Skinner of EEL attended and proposed a resolution replacing Mr Crosbie and Mr Martin as administrators with David Anthony Ross and Richard Albarran of Hall Chadwick. That resolution was carried.

29 In late July 2015, ASIC applied to this Court to remove the administrators appointed at the behest of Skinner and to reappoint Mr Martin and Mr Crosbie. ASIC’s application was made in circumstances where:

(a) Grochowski together with his solicitors EEL and Skinner had orchestrated the replacement of administrators appointed by Midland with those with whom EEL had had an existing relationship.

(b) ASIC had identified a number of matters to be investigated including:

(i) claims that Midland may have had against Grochowski, EEL, Skinner and other entities and individuals;

(ii) whether EEL’s and Bilkurra’s claims as creditors of Midland were valid, either at all or having regard to the set off of claims Midland may have had against them;

(iii) claims that investors may have had against Midland and third parties.

(c) Grochowski and EEL had proposed on behalf of Bilkurra a DOCA to be voted upon at the second meeting of creditors. ASIC held concerns that if the DOCA was approved, the prospect of the DOCA proponents’ conduct being investigated, including as to the misuse of $24 million of investor funds, would be significantly impaired.

30 On 4 August 2015, Mr Ross and Mr Albarran resigned as administrators of Midland. On 5 August 2015 Mr Crosbie and Mr Martin were reappointed as administrators by an order of this Court. An order was also made adjourning the second meeting of creditors of Midland to a date no later than 7 October 2015, which date I further extended until 21 October 2015. Mr Crosbie and Mr Martin then sought to arrange the second meeting of creditors. Prior to the second meeting, Bilkurra indicated that it would propose at that meeting that Midland enter into a DOCA. I will elaborate later on the DOCA proposal propounded by Bilkurra and its evolution.

31 On 14 October 2015, the administrators of Midland circulated a report in which they expressed the view that the DOCA proposed by Bilkurra was unfairly prejudicial to creditors. The administrators recommended that liquidators be appointed to Midland to, inter alia, pursue voidable transactions of up to $22.3 million as well as other potential claims of Midland against third party entities and individuals. The administrators recommended that the creditors of Midland not vote in favour of the DOCA proposed by Bilkurra.

32 The administrators reported that option fees from the retail investors of approximately $24 million had been paid into an EEL trust account and then transferred into “Project Bank Accounts” purportedly of Midland on Grochowski’s instructions to EEL. Grochowski, via PMA of which he was the sole director, controlled the Project Bank Accounts, and authorised payment of the $24 million out of such accounts. The administrators stated that Grochowski appears to have authorised and applied the proceeds of the option fees to the following suspect and voidable transactions:

(a) $9.6 million for activities unrelated to the development of the land including:

(i) $7.2 million to companies of which Skinner at the relevant time was the sole director, specifically $2.055 million to Brookfield Riverside Pty Ltd, $4.768 million to Foscari Holdings Pty Ltd and $351,000 to Gillies Road Pty Ltd. No explanation for such payments was provided to the administrators by Skinner despite requests made of Skinner. After such payments were made, Skinner was replaced by Mr Stephens as sole director of each company. Skinner or Evans Ellis Management Pty Ltd was the sole shareholder of the recipient of the payments. Shareholdings were recorded as “not beneficially owned” indicating that the shares were held for another undisclosed party.

(ii) $2 million to, or as directed by, Bilkurra as part payment of the purchase price ($1.4 million) and as a cancellation fee ($600,000) in respect of the contract(s) for the sale of land, despite Midland not receiving any benefit for such payments.

(iii) $420,000 for land adjacent to the land the subject of the development. Investment Mutual Holdings Pty Ltd was purportedly nominated as the purchaser and is now the registered proprietor of such land. Midland appears not to have received any benefit from such a payment.

(b) $7.3 million in “commissions” paid to Property Choice (30% of the option fees). No explanation or justification was provided to the administrators for such large payments.

(c) $4.6 million to PMA for project management fees. Grochowski engaged PMA as project manager for Midland at terms and rates determined by him under a project management agreement executed by John Wood and Grochowski effective from 14 December 2011.

33 The administrators were also aware of $761,000 of investors’ funds having been paid from an EEL trust account which also required investigation.

34 Only $1.7 million (7%) of the option fees received from third party investors appears to have been used for works necessary for obtaining a planning permit for the proposed plans of subdivision or otherwise progressing the development of the land. $22.3 million is either unaccounted for or has been siphoned off in questionable circumstances.

35 On 16 October 2015, Bilkurra through Mr Stephens as its director wrote to option holders addressed as “Dear Valued Customers” and made various statements including to the following effect:

(a) First, if option holders voted in favour of the DOCA, they would maintain all their rights and benefits in the options with the “total effect” of securing investors’ options in the Hermitage Bendigo development;

(b) Second, if option holders voted to put Midland into liquidation “you will not have any option contract relationship with Bilkurra and … will lose your Option in the Hermitage development” and “it is unlikely, in our opinion, that you will recover any of the monies paid in Option Fees”; and

(c) Third, it was in the option holders’ best interests to vote in favour of the DOCA.

36 Correspondence was also circulated to the option holders on 16 October 2015 by a senior property consultant of Property Direct attaching an email from the firm that had acted for “the majority of option holders”. That correspondence also made representations about the DOCA and stated that “it appears that for the development to proceed, you need to vote in favour of the DOCA”.

37 Although Bilkurra at one stage sought to suggest otherwise, the option holders are present creditors of Midland for at least $24 million. Such a liquidated sum is owing by reason of the operation of cl 15.3 of each option deed. Moreover, they are creditors for unliquidated sums in respect of damages claims for misleading representations made by Midland or on its behalf prior to the relevant investments being made. Further, Bilkurra has sought to take the benefit of such option holders being creditors to carry the vote in favour of the DOCA it propounded at the second creditors’ meeting of Midland.

38 At the second meeting of creditors of Midland held on 21 October 2015:

(a) The administrators expressed concern as to whether the communications referred to in [35] and [36] above accurately summarised the considerations relevant to the exercise of the option holders’ rights. In my view such communications were misleading and distorted and calculated to induce a favourable vote for the DOCA proposal propounded by an entity and its backers that in my view require full investigation.

(b) Mr Martin summarised the administrators’ investigations as follows:

Midland received in round figures about $24 million in option proceeds, the option fee proceeds. …

The $24 million of option fees received by the [EEL] trust account were paid to a company called Project Management Australia. Project Management Australia is directed by Michael Grochowski. We’ve also formed the view that Michael Grochowski was a shadow director of the company Midland Highway because he exercised the control, he ran the business and he ran the business not just in effect but also pursuant to a director agreement, which we’ve sighted, which says, in essence, that John Wood gives all responsibilities to Michael Grochowski and Michael Grochowski is the only person authorised to exercise control over the company’s business. …

Midland Highway, its option holders made payments for option deeds into the [EEL] trust account. [EEL] then disbursed those moneys to PMA, Project Management Australia, generally on the instructions of Michael Grochowski. Those $24 million have been disbursed very broadly as follows: $7.3 million has been paid to a company Property Choice for commissions, we understand. We haven’t seen the source documentation, we have seen invoices. In addition, at least $4.6 million has been paid to Project Management Australia for project management fees.

Anywhere between eight and nine million dollars has been paid to companies which don’t appear to have any interest in the land development. So in round figures around $22 million of the $24 million has been paid, other than for the specific land development. …

All the option moneys have been disbursed. Approximately or up to a maximum of $1.7 million appears to have been spent on consultants that appear to be relevant to the development. The balance of moneys, $22.3 million, has been spent other than as was intended. Because of that and various other issues, it’s our recommendation that the company’s creditors should resolve that the company be wound up …

(c) Mr Martin recommended that the creditors resolve to wind up Midland and stated:

[I]f the company is liquidated, if you choose to put the company into liquidation, there is nothing to stop option holders making direct approaches to Bilkurra. Midland, the company, is insolvent. …

[A] liquidator will look at $22 million worth of voidable transactions and other potential claims, including $7 million paid out for the purchasers or paid to Foscari and others, it will look at $7 million paid in commissions, it will look at $4.6 million paid to project managers — question whether that’s a commercial transaction.

If creditors resolve a deed of company arrangement, which is entirely at their discretion, creditors have lost the right to rely upon a liquidator to investigate those transactions and potentially recover.

(d) Mr Stephens, on behalf of Bilkurra, spoke in favour of the DOCA in the following terms:

[O]ur understanding of the deed that was put in place between Bilkurra Investments and Midland Highway in early 2014 are that we understood that all the rights and obligations of the option holders have been passed across to Bilkurra. It’s Bilkurra’s intention to continue with developing the site. ...

So what our proposal is is to reinforce what was put in place or what we believed was put in place in early 2014 and therefore go ahead with the deed of company arrangement which will allow the assignment of those rights and obligations to Bilkurra.

(e) No assurances were provided as to Bilkurra’s ability to finance the future development of Hermitage Bendigo or option holders’ rights against Bilkurra.

(f) The resolution to enter into the DOCA proposed by Bilkurra was passed. It is necessary to elaborate on the DOCA proposal as it evolved before, during and after the second meeting of creditors (see at [40] et seq. below).

39 Finally, I also note that the administrators’ report also indicated that Midland had not lodged tax returns or BAS statements after mid-2012 and that Grochowski had deleted accounting records for Midland up to 30 June 2012 previously maintained by PMA. Further, as Bilkurra accepted, Midland had not traded for the two years prior to the administrators’ appointment and it was “effectively a dormant company with no assets” (see the Stephens’ affidavit at [16]).

(d) Differences in the DOCA proposals

Pre-meeting proposal

40 Prior to the creditors’ meeting on 21 October 2015, Bilkurra put forward a DOCA proposal in the following terms:

(a) Midland would remove the caveat lodged by it over the land on execution of the DOCA (cl 4.1);

(b) Bilkurra would contribute $300,000 to a DOCA fund (cl 5.2);

(c) Bilkurra would discharge, by payment or other agreed arrangement, trade creditors known prior to the DOCA being executed (cl 6.1(a));

(d) unknown trade creditors’ claims would be subject to the DOCA fund (cl 6.1(b));

(e) Bilkurra agreed to enter into a deed poll to confirm its intention to perform the obligations of Midland under the option deeds and to “improve the overall commercial position of [an] Option Holder” (cl 7.1);

(f) Bilkurra could as it deemed fit and reasonable vary any term of the option deed “in the interests of option holders” (cl 7.2).

Creditors’ meeting proposal

41 The minutes of the creditors’ meeting of 21 October 2015 record discussion of “key terms of the DOCA proposal, which broadly reconcile with the EEL letter and DOCA proposal dated 12 October 2015, and which were reproduced on the whiteboard for all creditors to review”. The terms recorded on the whiteboard, which formed the proposal voted on by the creditors present at the meeting or by proxy, were as follows:

• BK to assume Midland’s obligations to option holders and OTP purchasers; and those creditors (being OHs and OTP purchasers) not to prove under the DOCA. And option holders to release Midland

• BK to pay stamp duty on behalf of option holders at the point when it becomes payable (settlement of contract & sale after exercise of the option)

• Deed fund of $300,000 payable within 30 days of DOCA execution to be applied in accordance with priority provisions of Corporations Act 2001

• Trade creditors (being other than OHs and OTP purchasers) to prove in deed fund (NB insufficient funds to pay anything to creditors)

• Withdrawal of caveat on execution of DOCA

• BK will be obliged to enter into deeds of novation with each option holder and OTP purchasers

• Control of company reverts to company director upon DOCA’s effectuation

42 The DOCA proposed at the creditors’ meeting differed relevantly from the initial DOCA proposal as follows:

(a) Under the proposal voted on at the creditors’ meeting, all “trade creditors (being creditors other than option holders and off-the-plan purchasers)” were to prove in the DOCA fund. Under the original proposal, Bilkurra proposed to separately pay or make some arrangement with known trade creditors outside the DOCA fund.

(b) Under the proposal voted on at the creditors’ meeting, Bilkurra would “assume” Midland’s obligations to option holders and off-the-plan purchasers. The minutes record that this was to be by way of novation. Under the original proposal, Bilkurra was to enter into a deed poll to confirm its intention to perform the obligations of Midland under the option deeds.

Post-meeting revised proposal

43 After the creditors’ meeting, a revised DOCA proposal was put forward by Bilkurra (see Mr Stephens’ affidavit). The document entitled “Revised DOCA Proposal Terms” stated as follows:

1. Bilkurra will assume all of Midland Hwy’s obligations to Option Holders and off-the-plan purchasers, whereupon each of the Option Holders will release Midland Hwy of any claim.

2. Bilkurra to pay the stamp duty on behalf of the Option Holders at the point when stamp duty becomes payable upon settlement of the subsequent off-the-plan contracts of sale.

3. Bilkurra will contribute to the Deed Fund a total sum of $1 million payable within 30 days of the DOCA execution, and, any trade creditors (that is, not including Option Holders) will be able to prove in the Deed Fund.

4. The Bendigo Caveat will be withdrawn upon execution of the DOCA Proposal.

5. Bilkurra will do all things necessary to novate each Option Holder and Off-the-Plan Purchaser in accordance with the terms and conditions of the respective Option Deed and/or Off-the-plan Contract of Sale.

6. The control of Midland Hwy reverts to company director upon the DOCA’s effectuation.

44 The post-meeting revised proposal differed from the meeting proposal as follows:

(a) The amount that Bilkurra proposed to contribute to the “deed fund” was $1 million (increased from $300,000 in previous proposals); and

(b) The reference to option holders was altered slightly: “trade creditors (that is, not including option holders) will be able to prove in the deed”.

45 I note that the administrators consider that the sum of $1 million would be insufficient to provide a return to creditors of 100 cents in the dollar.

46 I should note at this point that, strictly, the DOCA now sought to be entered into differs in relevant respects from the proposed DOCA voted on by the creditors. But I do note that the proposed changes do not seem to be further adverse to the creditors’ interests. Nevertheless, this may provide a further discretionary reason why the present creditors’ resolution should not be permitted to be implemented. But at most, this point would only entail that a new vote be taken rather than that there be a liquidation. I say at most as given that the changes are not further adverse to creditors, not even a new vote may be necessary. An order under s 447A could be made altering Part 5.3A in its application to Midland such that the previous resolution could be taken as providing the foundation for the modified DOCA if I was otherwise satisfied, which I am not, that the creditors’ resolution should not be set aside.

(e) Voting at the creditors’ meeting

47 The attachment to the minutes of the creditors’ meeting identified 176 voters present or represented at the meeting, of which 145 were represented by Ms Suen of EEL. The outcome of the voting at the meeting was recorded in the minutes of the meeting. Mr Stephens’ evidence is that 168 creditors who were option holders were admitted to vote. The resolution was carried by 170 votes; approximately 97% of such votes were submitted on behalf of option holders, 2% on behalf of off-the-plan purchasers and 1% on behalf of trade creditors of Midland. As I have said, there were about 700 option holders.

48 As I have indicated earlier, there is little doubt that Bilkurra and persons associated with the suspect transactions communicated with option holders prior to the creditors’ meeting for the purposes of corralling their votes and obtaining proxies. This was apparently done in the following and in my view misleading fashion, as deposed to by Ms Prendergast in her affidavit of 23 October 2015 at [17] and [18]:

17. On 19 October 2015, I received two emails from Nicholas Martin, one of the PPB Administrators, which forwarded the following email communications:

(a) An email from Chris Freeman (support@chrisfreeman.com.au) sent on Friday, 16 October 2015 at 16:23:15 (Freeman Email). The addressees are not specified. Mr Freeman states in his email to see the attached Proxy and also an email from Colin Adno. The email then states:

“To allow the development to proceed, complete the attached proxy form (You MUST: tick the general proxy box and sign on page 2 where it prompts) and email back to support@chrisfreeman.com.au and/or freya.southwell@eelaw.com.au

Email from Colin Adno:

Given the fact that I have not been briefed to advise on this matter, I cannot offer you specific advice.

Having said this, it appears that for the development to proceed, you need to vote in favour of the DOCA.

If you cannot vote in person, you should appoint Evans Ellis or Bilkurra to be your proxy.

See attached Proxy for your information – complete sign and email it to freya.southwell@eelaw.com.au”

(b) An email from info@hermitagebendigo.com.au dated 16 October 2015 which attached a letter from Ian Edward Stephens, Director of Bilkurra addressed to “Dear Valued Customers” dated 16 October 2015 (Hermitage Bendigo Email). The Hermitage Bendigo Email urged investors in the Hermitage Bendigo development to vote in favour of the Bilkurra Deed Proposal at the second meeting of creditors. The letter includes:

(i) A statement to the effect that if option holders voted in favour of the DOCA, they would maintain all their rights and benefits in the option, with the “total effect” of securing investors’ options in the Hermitage development;

(ii) Statements that if option holders voted to put Midland into liquidation, “you will not have any option contract relationship with Bilkurra and … will lose your Option in the Hermitage development” and “it is unlikely, in our opinion, that you will recover any of the monies paid in Option Fees”; and

(iii) the following statement:

We ask that you act in your best interests and protect your Option in the Hermitage development by voting in the Deed of Company Arrangement proposed by Bilkurra Investments Pty Ltd.

The letter also includes a guide on how to vote at the meeting and/or to appoint Josephine Suen of Evans Ellis Lawyers, Bilkurra’s solicitor, as their proxy to vote at the Second Meeting of Creditors.

18. In relation to the above email communications, I note that:

(a) Chris Freeman was a Senior Property Consultant at 21st Century Property and 21st Century Property Direct, and sold options in the Hermitage Bendigo development.

(b) In relation to Colin Adno, the PPB Administrators state on page 33 of the Report to Creditors that:

The invoices from Property Choice show a commission of $12,500 (including GST) was charged for each Option Deed, with payment required to be made to Colin Adno & Associates Pty Ltd Law Practice Trust Account. Colin Adno is also the sole director of Summit Property and Business lawyers Pty Ltd trading as Summit Law which acts for the majority of Option Holders and Purchasers. Based on searches, both law firms operate from the same address and with the same telephone numbers.

A Liquidator, should the creditors resolve to wind up the Company at the Second Meeting, may investigate the potential conflict for Mr Adno.

Mr Adno is listed in Appendix I (page 88 and 90 of the appendices) of the Report to Creditors as a person the liquidator may consider examining.

(c) Mr Ian Stephens is the current director of Bilkurra. On page 30 of the Report to Creditors, the PPB Administrators consider that approximately $2m paid to Bilkurra may constitute voidable transactions. Mr Stephens is listed in Appendix I (page 87–88 and 93 of the appendices) of the Report to Creditors as a person the liquidator may consider examining.

Such communications were misleading in relation to option holders’ rights and the effect of entry into the DOCA on such rights.

49 Before me, Bilkurra has placed much store in the fact that the option holders have voted overwhelmingly in favour of the DOCA proposal. But as to this:

(a) First, only a modest percentage of the total option holders voted.

(b) Second, their votes were corralled in questionable circumstances with questionable statements made by persons and entities, who had an interest in avoiding investigation and the liquidation of Midland, in order to procure a favourable vote.

(c) Third, the option holders as retail investors were vulnerable and susceptible to that questionable behaviour.

(f) Entities and transactions to be investigated

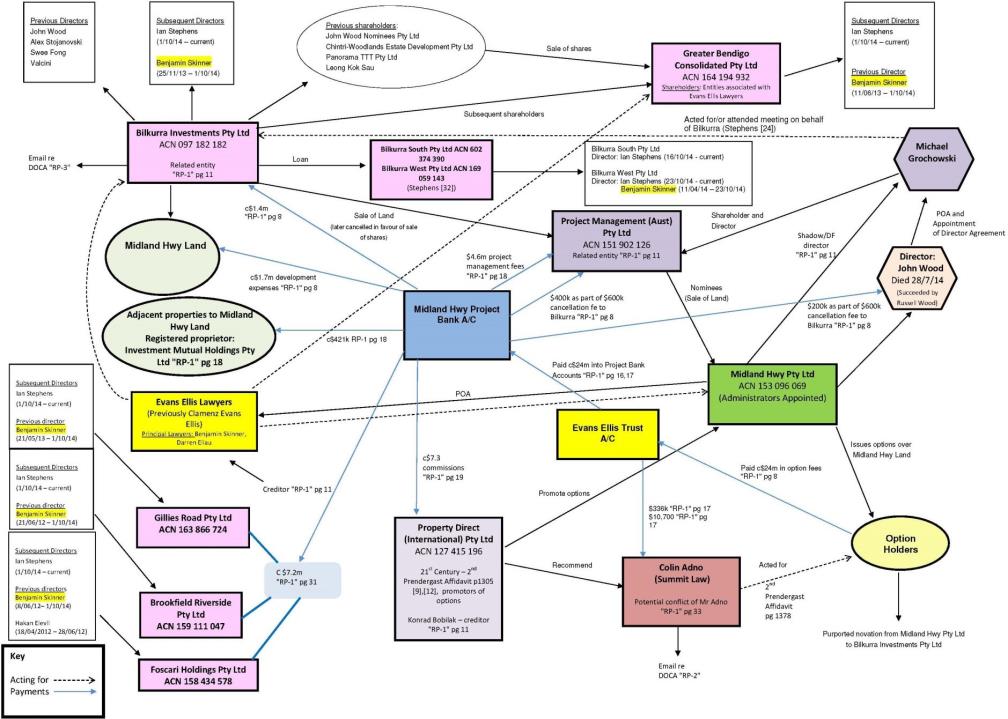

50 The following diagram usefully sets out the entities and transactions that will require investigation. The web of entities and transactions is complex. Any investigation and associated recovery proceedings will involve complexity of a type that a liquidator is best placed to carry out.

(g) Financial affairs of Bilkurra

51 Mr Stephens is an accountant and has been a director of Bilkurra for over a year. In cross-examination, he stated that Bilkurra had the financial standing to complete the development of the land. I do not accept that evidence.

52 First, no financial statements of Bilkurra have been produced in evidence.

53 Second, Mr Stephens stated that he was currently “reconstructing” all of Bilkurra’s financial records to ensure their accuracy. Bilkurra last prepared financial statements and income tax returns for the year ending June 2012. Mr Stephens also stated that the books and records of other associated companies of which he took over as director from Skinner in or around September 2014, were in the same parlous state as Bilkurra’s books and records. The absence of financial records does not give one any confidence in Bilkurra’s state of affairs. Moreover, Mr Stephens has had over a year to rectify this, but has apparently achieved little in this respect.

54 Third, in terms of Bilkurra’s assets, the land (as is) had been independently valued in April 2015 at a gross value of around $16 million. The balance of Bilkurra’s bank account (held by PMA) was less than $100,000. Bilkurra had also loaned funds to Bilkurra South Pty Ltd and Bilkurra West Pty Ltd, its wholly owned subsidiaries incorporated for the purpose of acquiring lots adjoining the land which compromises the Bendigo development.

55 Fourth, Mr Stephens stated that Bilkurra had trade creditors of not more than $10,000 and also had a liability of approximately $6.4 million to the first registered mortgagee of the land. Bilkurra had received a notice of default pursuant to the mortgage which stated that “[t]he Mortgagor [Bilkurra and Foscari] has defaulted in the performance of its obligations and covenants under the Loan Agreement … in that it has failed to pay the Principal Sum of $3,500,000.00 pursuant to Tranche 1 and $2,465,000.00 pursuant to Tranche 2 by the Due Date”. Mr Stephens asserted that the reason for the default was that the previous funder did not want to be involved in the project because of the amount of adverse publicity. Such an assertion was not supported by any independent evidence. Mr Stephens said that Bilkurra had “borrowed” money from “NWC Finance” to repay the debt but it had not yet been refinanced due to the caveat over the land. Again, this was assertion.

56 Fifth, Mr Stephens stated that Bilkurra was finalising negotiations for a joint venture arrangement with “a large Australian developer” who had agreed to fund 100% of the development costs until completion. Mr Stephens stated that the total development cost would be approximately $65 million and that the profit would be in the order of $65 million. But all that was produced in evidence before me was an unexecuted draft joint venture deed.

57 In relation to the draft joint venture deed and what appears from its face, the following may be noted:

(a) There were three joint venturers referred to being Bilkurra (as to 50%), Heritage Property Finance Pty Ltd (Heritage) (as to 25%) and a company that I shall refer to as X Pty Ltd (as to 25%).

(b) The draft deed provided for a company that I shall refer to as Y Pty Ltd to hold the assets of the joint venture and to act as the developer of the project, as agent for the joint venturers. Y Pty Ltd would also appoint a project manager.

(c) The joint venturers agreed to make capital contributions to the project. The initial project funding amount was $14 million. Heritage and X Pty Ltd were to make the initial capital contributions in equal shares up to the $14 million. Bilkurra’s contribution was, apparently, the land. Additional capital contributions were also contemplated.

(d) The draft deed also provided that Y Pty Ltd would obtain debt facilities to fund the project, secured by a mortgage over the land. Mr Stephens said in evidence that, nevertheless, the vast majority of the funding would not come from debt funding but “profits that the project makes along the way”.

58 Generally, Mr Stephens said that the developer entity, a special purpose vehicle to be incorporated by or on behalf of the (as yet unformed) joint venture committee, would obtain finance for the development from the joint venture partners in the amount of $14 million and would also hold the land. He said that the vast majority of the funding would not come from debt funding but from the profits that the project progressively made. Mr Stephens stated that Bilkurra would not have to fund any of the development from its own resources as it was providing the land. However, I note that the deed provided that in the event that the initial capital contributions exceeded the project funding amount, the venturers must contribute additional capital. “Venturers” was defined to mean the three parties to the deed. Mr Stephens stated that this was a fall-back clause that was unlikely to be required because the $14 million would be sufficient to commence the development and the ongoing profits from the staggered development and sale of the 1700 lots would be rolled back into the development to fund its progress.

59 As to the development, Bilkurra asserts that it has made significant progress in undertaking the development including:

(a) preparing and lodging an endorsed development plan in respect of the land;

(b) dealing with and obtaining relevant authority approvals;

(c) liaising with third party objectors in respect of the development plan and town planning permits;

(d) engaging consultants to undertake studies and reports including traffic studies, cultural and heritage assessment reports, civil engineering studies, flora, fauna and biodiversity reports, community needs reports and assessments, landscaping reports and town planning reports;

(e) obtaining planning permits for plans of consolidations and plans of subdivisions of “super” lots;

(f) preparing architectural housing designs and 3D renders of streetscapes and housing designs;

(g) commencing tender discussions with local builders for the construction and real estate agents to launch retail sales in respect of the development.

60 All of this may be so. But in my view none of this detracts from my conclusions set out earlier and at [62] below concerning the financial position of Bilkurra.

61 Finally on this aspect, Bilkurra has said that it is now “standing behind” all of Midland’s debts. But clearly, it is neither able to nor purporting to discharge Midland’s debts to the option holders.

62 A number of conclusions may be drawn from this unsatisfactory evidence adduced by Bilkurra:

(a) First, Bilkurra’s financial affairs including its records and accounts provide little if any confidence in being able to draw favourable conclusions as to its financial health or its capacity to implement and complete the development of the land. Mr Stephens asserted that Bilkurra is solvent. I very much doubt this on any traditional measure, save that it can be accepted that it has positive net tangible assets.

(b) Second, and relatedly, Bilkurra has little in the way of liquid or current assets. There was a suggestion in the evidence that Bilkurra could draw upon a bank account held in another name, although the balance was “very low” and “less than $100,000”.

(c) Third, and relatedly, no evidence has been provided to me to demonstrate that Bilkurra has any or any adequate working capital. Moreover, no information has been provided showing any surplus of current assets over current liabilities.

(d) Fourth, and relatedly, the evidence demonstrates that Bilkurra has positive net tangible assets, being essentially the land whose value exceeds the level of liability under the registered mortgage. But relevantly, Bilkurra is in default under the relevant mortgage, with the principal and interest having been called up. Moreover, the capacity to refinance is unclear in the light of Midland’s caveat over the land and other matters, although Mr Stephens suggested in evidence, without any supporting documents, that refinancing had been agreed to be provided by NWC Finance.

(e) Fifth, there is no executed joint venture agreement currently in place for the development of the land. Moreover, the draft form provided to me indicated that third party finance may be needed outside the joint venturers’ capital contributions in order to fund the development. Mr Stephens unconvincingly sought to assert that “a large Australian developer [had] agreed to fund 100 per cent of the development costs” and also that the development would largely be self-funding at least after the initial capital contributions were made. This was bare assertion not supported by any probative evidence; the same can be said for the assertions in [34] and [35] of his affidavit. Moreover, there was no binding or even conditional agreement with the “large Australian developer”. Certainly, none was adduced in evidence.

63 In summary, I have little confidence in reaching any conclusion that Bilkurra could properly carry through the transactions contemplated by the DOCA, let alone inject value into the development of the land (or indeed complete that development) in a way that might provide real value to the investors. Mr Leslie Glick QC, counsel for Bilkurra, submitted that I should refuse ASIC’s application and allow the DOCA to be executed. He said that if the DOCA was executed and later not complied with by Bilkurra, then the DOCA could be terminated and nothing was lost. His beguiling submission was that a “wait and see” approach should be adopted. I do not consider that approach to be appropriate. There is a real doubt to say the least that Bilkurra can carry through the relevant transactions. Moreover, the various other transactions that I have referred to earlier, including Bilkurra’s involvement therein, need to be fully investigated with any recovery action (if appropriate) taken sooner rather than later by a liquidator of Midland.

some uncontroversial principles

64 Section 447A of the Act provides that the Court may make such order as it thinks appropriate about how Part 5.3A is to operate in relation to a particular company.

65 Section 447A provides the Court with power to terminate the administration and to order a winding up in the public interest. In Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Woodings (1995) 16 ACSR 266 at 279, Wallwork J said:

I am satisfied that s 447A gives power to the court to order a winding up of the company in the public interest in a case such as this. Such a power is not inconsistent with the provisions in Pt 5.3A, and in the light of the decided cases which are referred to in these reasons, it is in the public interest that the company be wound up and not be allowed to be further manipulated by Mr Morris or his associates.

66 In the case of a prima facie insolvent company, it may be appropriate to order its winding up, particularly where a proposed DOCA will not restore the company to financial health, potentially has the purpose or effect of quarantining third parties from investigation and recovery proceedings, and has little realistic tangible upside for all creditors. It is against the public interest to allow such a company to operate in the market place.

67 The Court’s power under s 447A is to be exercised having regard to, inter alia, the interests of the creditors as a whole and the public interest. But in an unusual case, the public interest may override the creditors’ interests and favour liquidation.

68 The public interest includes considerations of commercial morality and the interests of the public at large (Bidald Consulting Pty Ltd v Miles Special Builders Pty Ltd (2005) 226 ALR 510 at [287] per Campbell J). Where there has been misconduct in the affairs of a company requiring appropriate investigation by a liquidator and appropriate recovery proceedings being considered and undertaken, it is detrimental to commercial morality to prevent or hinder such steps through the device of a DOCA propounded by entities and individuals who ought be the subject of investigation and the target of such proceedings. A winding up will be beneficial from a public interest perspective where investigations and recovery proceedings are likely to be funded and the investigations and appropriate recovery proceedings could realistically lead to the relevant persons who have engaged in the suspect transactions being brought to account: Public Trustee (Qld) v Octaviar Ltd (subject to a deed of company arrangement) (2009) 73 ACSR 139 at [182] per McMurdo J.

69 More specifically and of direct relevance to the present context, the Court has power under s 447A to set aside a resolution to enter into a DOCA and to order the winding up of the company. In exercising such a power, the Court can apply by analogy any one or more of the principles applicable to s 445D. In other words, if a DOCA if entered into pursuant to the relevant resolution could be terminated under s 445D, then by analogy in the scenario where a DOCA has not yet been executed pursuant to that resolution, s 447A can be used to prevent the DOCA from being entered into. But none of this is to deny or limit the broader ambit of s 447A. Section 447A can be used to make the orders sought by ASIC, whether or not any element of s 445D could be hypothetically or contingently invoked, although I accept that s 445D(1)(g) is broad and on one view unconstrained, save by its context and s 435A generally, such that this proposition may only be of theoretical interest. But it is correct to say that even if none of the elements of s 445D could be satisfied, the orders sought could still be made under s 447A. But let me address s 445D for a moment.

70 The Court may set aside a DOCA pursuant to s 445D even where creditors may be better off under the DOCA than with a liquidation: Bidald Consulting Pty Ltd v Miles Special Builders Pty Ltd at [286] to [291] per Campbell J. It may do so in the public interest.

71 Where the relevant company is not trading and there is no likelihood of its resuming its former business, the public interest in placing the company in the hands of a liquidator may prevail over the interests of creditors (see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Storm Financial Ltd (recs and mgrs apptd) (admin apptd) (2009) 71 ACSR 81 at [69] and [71] per Logan J).

72 In QBI Corporation Pty Ltd v Plantation Rise Pty Ltd (admins apptd) (recs and mgrs apptd) (2010) 77 ACSR 573 a DOCA was set aside where there was no continuing business preserved and the structure designed and enshrined in the DOCA was to allow and facilitate the director of the company and third parties who were susceptible to voidable transactions to be protected from relevant action.

73 Generally, the breadth of s 445D(1)(g) is such that in a particular case the public interest can justify the termination of a DOCA even where it is not established that this would necessarily be in the creditors’ interests.

74 Finally, in any event, the preclusion of an effective investigation by a liquidator into relevant transactions and the opportunity for greater returns may render a DOCA contrary to the creditors’ interests overall (see Canadian Solar v ACN 138 535 832 Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 783 at [37] per Perry J).

Application of principles

75 In my view, the creditors’ resolution should be set aside or otherwise treated such that it ought not be acted upon. If a DOCA had been entered into in conformity with that resolution, it would have been liable to have been set aside under s 445D(1)(f) and (g) of the Act at the least, both as to the existence of the triggers and the appropriate exercise of discretion. In conformity with the above principles, I see no good reason why the orders sought by ASIC should not be made. Midland should be placed in liquidation.

76 First, Midland is insolvent. Moreover, it is a corporation that has been used and controlled by shadowy figures and entities. It has little if any assets and substantial liabilities to third parties including the option holders. Bilkurra has contended that Midland has not been “stripped” and that it is not a “failed company”. As Bilkurra described it, Midland “is simply a company that is no longer of use due to a standard corporate restructure”. In my view, this significantly understates Midland’s position and its involvement in the relevant transactions. In any event, it is not in dispute that Midland has no financial substance.

77 Second, on any view, the implementation of the proposed DOCA will not restore Midland to a position where it is able to trade. It will still remain in substance a shell corporation. It is not in the public interest to allow such a corporation to continue in existence to the detriment of future creditors and other persons dealing with Midland.

78 Third, there are transactions involving substantial sums that require full investigation and, if appropriate, the institution of recovery proceedings. That is appropriately done by a liquidator, rather than ASIC. A liquidator will have the necessary role and focus to carry out the necessary investigations. If necessary, ASIC may finance that task (see the Prendergast affidavit sworn 23 October 2015 at [23] to [25]). Moreover, it is not ASIC’s role or obligation to undertake the detailed investigation required and even if it were, a liquidator is best placed to do this. Further, it is for a liquidator to take the necessary recovery proceedings (e.g. s 588FF) rather than ASIC. Moreover, a liquidator does not need to establish a contravention of the Act for the purposes of s 588FF proceedings. Further, if any DOCA was to be allowed to proceed, the same may operate directly or indirectly as an inappropriate release of Midland’s claims against entities and persons against which a liquidator might otherwise take recovery proceedings. Moreover, under the DOCA, option holders will lose their rights to make a claim against Midland, although it is accepted that such claims may be of little value at present.

79 I accept that it is not the role of the administrators (or indeed any liquidator) to pursue a wide ranging inquiry into the public interest or commercial morality of Midland’s behaviour or in relation to the consideration of the DOCA. Rather, such a role is assigned to ASIC, the ATO and other public authorities invested with the powers and responsibilities of law enforcement (cf Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Wellnora Pty Ltd (2007) 163 FCR 232 at [210] per Lindgren J). Rather, the administrators’ focus is that provided by s 438A in the context of s 435A. So, the administrators’ focus, indeed that of a liquidator, is to consider Midland and its creditors. But none of that is inconsistent with the administrators’ recommendation and the objective step of liquidation to properly facilitate and initiate a full investigation and any necessary recovery proceedings against third parties, which a liquidator is best placed to pursue.

80 Fourth, it seems to me that the primary purpose or effect of the DOCA is to limit if not hinder a full investigation of various entities and persons, including Bilkurra, in relation to the shadowy transactions described earlier and ultimately to quarantine them from potential recovery proceedings by a liquidator.

81 Fifth, the propounder of the DOCA, Bilkurra, is of questionable financial standing. I doubt that it has the capacity to carry through the transactions contemplated by the DOCA, let alone the development of the land. I found Mr Stephens’ evidence to be quite unsatisfactory. Bilkurra has also asserted that it will assume Midland’s liabilities to the option holders (if they have not already been assumed), but as ASIC points out, this is not an obligation that it can afford or necessarily discharge.

82 Sixth, in my view, the option holders will receive little if any tangible benefit under the DOCA. Moreover, Bilkurra can separately treat with the option holders even if the DOCA is not entered into and Midland placed in liquidation.

83 It is appropriate to elaborate further.

84 The DOCA does not bind Bilkurra to carry out the development for the benefit of the investors in Midland. In any event, having regard to the highly uncertain apparent financial position of Bilkurra, one could not be confident that it will do so.

85 Bilkurra has asserted that a number of advantages flow to the option holders if the DOCA is entered into.

86 First, it is said that the “option deeds will be preserved”, whatever that means. But they will be preserved anyway absent the DOCA and are currently enforceable against Midland.

87 Second, it is said that the “option holders will have a direct relationship with the registered proprietor of the land, which is already infinitely better than maintaining a relationship with a company such as [Midland], which has little to no assets”. But that can occur anyway absent the DOCA and even if Midland is wound up. Bilkurra can enter into separate arrangements with the option holders in any event.

88 Third, it is said that the option holders will be “able to realise their investments in the Bendigo development”. But there is nothing in the DOCA proposal that provides for or entails such a consequence or that it has any tangible commercial reality. Moreover, there is nothing concerning Bilkurra’s financial position or status that would give me or the option holders any confidence that the project will proceed to completion. Moreover, the project appears to now be in the hands of entities and persons implicated in the very transactions under which $24 million of option holders’ funds have been siphoned off in shadowy circumstances and through the use of phantom like corporate structures. It is counterintuitive to suggest that Bilkurra’s “trust us” approach could have even an air of verisimilitude, let alone any reality.

89 Fourth, I accept that some trade creditors may be advantaged under the DOCA proposal, but that is all, other than of course the entities and individuals who may benefit from investigations and recovery proceedings being hindered if not thwarted if the DOCA was entered into.

90 Bilkurra has asserted that a number of disadvantages flow to the option holders if Midland goes into liquidation.

91 First, it is said that the option deeds and option holders’ rights against Midland will be valueless. I agree that this is a real risk, but then there is the potential for recovery proceedings to be taken by a liquidator that may reinject value back into Midland and hence to the option holders’ claims as creditors. I accept though that to some extent this is a matter of speculation.

92 But there are realistic possibilities. One example relates to what the administrators have asserted under cl 6.4 of the share option deed. There are other possibilities. For example, for all I know, a liquidator may take the position that:

(a) The contract(s) of sale of the land to ultimately Midland was not lawfully cancelled in 2013 or that such cancellation and the other 2013 transactions should be set aside;

(b) Midland has paid all or part of the purchase price for the land and may still have an equitable interest therein for at least the purchase moneys paid if not more;

(c) The net equity in the land of about $10 million ($16 million less the amount owing under the registered mortgage) may be charged with Midland’s equitable interest.

93 A liquidator might be quite entitled to pursue various questions. Why was the contract(s) cancelled? After all Midland had received $24 million from investors. It had the wherewithal to complete the purchase. Why did it have to pay a cancellation fee? It does not appear that cancellation was in Midland’s interests. But if cancellation was to occur, why were the purchase moneys not repaid by Bilkurra?

94 Generally, Midland received $24 million from retail investors to be used ultimately for the purchase and development of the land. The $24 million is missing in the sense explained earlier. Yet Bilkurra has the land, and other entities and individuals have received and had the benefit of most of the $24 million. Midland now has nothing. The investors have nothing. All of this demands a proper investigation by a liquidator and appropriate recovery proceedings.

95 Second, it is said that the option holders will have no direct rights in the project. I accept this, unless Bilkurra separately treats with them. But then their money seems to have been lost in any event. Further, whether the project would be completed is problematic in any event.

96 Third, and relatedly, it is said that the option holders will crystallise their losses and lose any taxation or other benefits arising from entry into the option deeds. I accept that actual or potential theoretical downside. But it is to some extent ameliorated by the potentiality for recoveries at the behest of a liquidator.

97 Fourth, Bilkurra has said that creditors voted in favour of the DOCA. It has also said that no additional information of substance has been provided to or by ASIC that was not provided by the administrators to the creditors for their consideration at the second creditors’ meeting. But none of these points can carry the day. In the present case, the creditors’ interests do not trump the public interest. Moreover, the retail investors in one sense were a vulnerable class and their votes were procured and corralled by Bilkurra and its backers in questionable circumstances.

98 In summary, the DOCA is not in the interests of creditors. Further, it may be unfairly prejudicial to or unfairly discriminatory against at least some of Midland’s creditors for the DOCA to be entered into and implemented, including as between trade creditors on the one hand and the option holders or priority creditors on the other hand. Moreover, I agree with the administrators in the views that they expressed in their report at pp 39 to 42 in relation to the imprecision and unsatisfactory aspects of the DOCA proposal, although I do accept that the position concerning trade creditors has now been addressed through modifications and an increase in the proposed DOCA fund.

99 Further, and as I have indicated, Bilkurra provided a misleading picture to the creditors prior to the second creditors’ meeting for the purposes of seeking to procure their votes. In such circumstances, if the DOCA had been entered into, s 445D(1)(a) may also have been triggered.

100 Further, and for the reasons already indicated, even if creditors overall would be better off under the DOCA than a liquidation (a matter which is at the very least disputable, given that Bilkurra’s financial capacity to undertake the development is uncertain), the DOCA should not be allowed to be entered into. The public interest requires the winding up of Midland. It would be contrary to the public interest, including considerations of commercial morality and the interests of the public at large, to permit Part 5.3A of the Act to be utilised in order to avoid an investigation and to thwart appropriate recovery action, particularly where there is no intention for any part of the business of Midland to be salvaged.

Conclusion

101 In my view, the orders sought by ASIC should be made.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and one (101) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate: