FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1263

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | JETSTAR AIRWAYS PTY LIMITED (ACN 069 720 243) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 30 November 2015, the applicant serve upon the respondent and lodge with the Associate to Foster J a draft of the declarations, injunctions and other orders which it considers appropriately reflect the decisions explained in Reasons for Judgment published this day by Foster J (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1263).

2. By 7 December 2015, the respondent inform the applicant and the Associate to Foster J whether the respondent agrees that the declarations, injunctions and orders proposed by the applicant accurately and adequately reflect Reasons for Judgment of Foster J published this day (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1263).

3. The question of costs be reserved.

4. Each party have liberty to apply on three (3) days’ notice or on such shorter notice as a Judge might allow.

5. The proceeding be adjourned to a date to be fixed after 7 December 2015 for the purpose of making final orders and determining the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 616 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | VIRGIN AUSTRALIA AIRLINES PTY LTD (ACN 090 670 965) Respondent |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 NOVEMBER 2015 |

WHERE MADE: | SYDNEY |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 30 November 2015, the applicant serve upon the respondent and lodge with the Associate to Foster J a draft of the declarations, injunctions and other orders which it considers appropriately reflect the decisions explained in Reasons for Judgment published this day by Foster J (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1263).

2. By 7 December 2015, the respondent inform the applicant and the Associate to Foster J whether the respondent agrees that the declarations, injunctions and orders proposed by the applicant accurately and adequately reflect Reasons for Judgment of Foster J published this day (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1263).

3. The question of costs be reserved.

4. Each party have liberty to apply on three (3) days’ notice or on such shorter notice as a Judge might allow.

5. The proceeding be adjourned to a date to be fixed after 7 December 2015 for the purpose of making final orders and determining the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 615 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | JETSTAR AIRWAYS PTY LIMITED (ACN 069 720 243) Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 616 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | VIRGIN AUSTRALIA AIRLINES PTY LTD (ACN 090 670 965) Respondent |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE: | 17 NOVEMBER 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 Jetstar Airways Pty Limited (Jetstar) and Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd (Virgin) are the two largest low-cost passenger airlines operating passenger flights within Australia and between Australia and certain destinations overseas. Together they have a very substantial share of the relevant market for the provision of passenger carriage services by air.

2 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), in its capacity as the regulator under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA), has brought a proceeding against each of Jetstar and Virgin alleging against both corporations that, in connection with the promotion and sale of fares for airline passenger travel, both airlines engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive. The airlines also stand accused of making false representations in connection with the sale of such travel services.

3 The statutory provisions relied upon by the ACCC are ss 18(1), 29(1)(i) and 29(1)(m) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). The ACL is Sch 2 to the CCA.

4 The ACCC seeks declarations, injunctions, corrective advertising and pecuniary penalties. It also seeks the costs of both sets of proceedings. As far as its claims for relief are concerned, the ACCC relies upon ss 224, 232 and 246(2)(d) of the ACL. It also relies upon s 21 and s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

5 The proceeding against Jetstar and the proceeding against Virgin were heard at the same time although much of the evidence in each case was not common. At the initial trials, only the ACCC’s claims for declarations and injunctions are to be determined. Its claims for corrective advertising orders and pecuniary penalties are, if necessary, to be dealt with subsequently.

6 The contraventions alleged against Jetstar concern past conduct on its part being conduct engaged in by it in 2013 and 2014. Jetstar has subsequently modified its behaviour. Nonetheless, the allegations made by the ACCC against Jetstar have ongoing significance because they raise for the Court’s consideration the limits of certain promotional and advertising techniques adopted by businesses which use the internet and mobile phone networks to promote and sell their products and services.

7 The contraventions alleged against Virgin relate to conduct by Virgin in 2014. The evidence before me suggests that that conduct is continuing.

8 The ACCC’s complaint is that both Jetstar and Virgin advertised and promoted airfares for sale at a prominent headline price without adequately disclosing to potential customers that they would be required to pay a booking and service fee for payments made using one or more popular and commonly used payment methods including paying by widely accepted debit cards and credit cards. It was submitted by the ACCC that, in practice, while it was possible to avoid paying this booking and service fee, most customers, in fact, paid the fee in respect of most transactions.

9 The ACCC argued that the technique deployed by both airlines was to require each online or mobile customer to enter a carefully constructed staged booking process throughout which information was disclosed on a progressive basis. As a result of this series of progressive disclosures, the headline price was, bit by bit, qualified and increased until the final, larger price for the particular airfare was arrived at. The ACCC submitted that the overall effect of this process was that the most attractive feature of the promotion viz the headline price was initially and thereafter repeatedly emphasised while those aspects of the likely transaction (including the existence of the booking and service fee) were de-emphasised in comparison and only disclosed piecemeal and late in the process.

10 The ACCC submitted that the vice in this type of conduct was aptly described by Tracey J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AirAsia Berhad Company [2012] FCA 1413 where his Honour said (at [31]) in relation to conduct proscribed by s 48 of the ACL:

I accept that it is necessary to have regard to the entire booking process and to the fact that, having completed it, a consumer would have become aware of the full price to be paid before committing him or herself to a purchase. It is also relevant that, on Page 2, the potential customer was advised that the fares there quoted excluded taxes and fees. These considerations do not, however, weigh heavily in mitigation. The principal vice to which s 48 is directed is the seductive effect of a quoted price which is lower than the actual amount which the consumer will have to pay in order to receive the relevant service. Unless the full price is prominently displayed the consumer may well be attracted to a transaction which he or she would not otherwise have found to be appealing and grudgingly pay the additional imposts rather than go to the trouble of withdrawing from the transaction and looking elsewhere. The company which is seeking to attract business in contravention of s 48 will also obtain an advantage over competitors who are compliant. The relevant errant conduct continued over many months and had the potential to influence thousands of bookings.

11 The ACCC accepted that the existence of the booking and service fee and the terms upon which it would be levied were ultimately disclosed in every case before the customer entered into any binding legal obligation to purchase and pay for a seat on any particular flight. Nonetheless, it contended that all of the impugned conduct in the present proceedings was in that class of case sometimes described as the seduction of consumers into the seller’s “web of negotiation” or “marketing web”, which conduct is capable of contravening s 18 and s 29 of the ACL even though the customer is apprised of the truth before the purchase transaction is completed. In support of these latter propositions, the ACCC drew the Court’s attention to 652–655 ([39] and [45]–[50]) in the joint judgment of French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG) and the cases cited in those paragraphs.

12 The ACCC urged a two-step analysis upon the Court. This analysis requires the Court to answer two questions, namely:

(a) Which of the representations pleaded in the Fast Track Statements (if any) were conveyed by the airlines’ conduct? and

(b) At the time each such representation was made, was the representation misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, or false?

13 The ACCC submitted that, if the second of those questions is answered “yes”, it does not matter that the representation was later corrected. In other words, it was the ACCC’s case that, if, by their conduct, the airlines represented at the outset or near the beginning of the booking process that seats on a number of particular flights could be purchased for a specific price in such a way as also to convey at the same time that there would be no additional fees and charges imposed on the customer simply because of the method of payment chosen by the customer, then the airlines contravened the ACL notwithstanding that the booking and service fee was later comprehensively and accurately disclosed before the transaction was completed.

14 It is apparent from the above synopsis of the ACCC’s case against the airlines that the first integer of that case is that by their conduct, the two airlines made the pleaded representations. Thus, the ACCC’s case against both Jetstar and Virgin depends upon the Court finding that each of them made the representations alleged. If the Court concludes that no representations in the terms relied upon by the ACCC were made by the airlines, then the ACCC’s case will fail. It is only if, upon analysis, the Court finds that the airlines made the representations as alleged or, at least, one or more of them, that it will be necessary to consider whether certain qualifying statements operated to overcome the impact of those representations and thereby corrected the false impression created by them (see, for example, the judgment of McLure P in Bayswater Car Rental Pty Ltd v Department of Employment and Consumer Protection [2008] WASCA 43).

15 In certain circumstances, it may be that, because corrective or qualifying material is published prominently and in proximity to the allegedly false representations, no false representation was made in the first place. Whether that is so in any given case will depend upon all of the circumstances of the particular case.

16 Jetstar and Virgin argued that their conduct did not convey the representations which the ACCC suggested were conveyed by that conduct and that, even if it did, they did not contravene the ACL because adequate disclosure of the existence and terms of the booking and service fee was made before any binding legal obligation was entered into between them and the customer.

17 In order to determine on which side of the line these cases fall, it will be necessary to examine the airlines’ conduct in some detail. Before doing so, I propose to discuss the relevant legal principles. These principles will apply to both cases.

The Relevant Law

The Relevant Statutory Provisions

18 Section 18 and s 29 of the ACL are in the following terms:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3–1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

Note: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5–3.

…

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

(c) make a false or misleading representation that goods are new; or

(d) make a false or misleading representation that a particular person has agreed to acquire goods or services; or

(e) make a false or misleading representation that purports to be a testimonial by any person relating to goods or services; or

(f) make a false or misleading representation concerning:

(i) a testimonial by any person; or

(ii) a representation that purports to be such a testimonial;

relating to goods or services; or

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation; or

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services; or

(j) make a false or misleading representation concerning the availability of facilities for the repair of goods or of spare parts for goods; or

(k) make a false or misleading representation concerning the place of origin of goods; or

(l) make a false or misleading representation concerning the need for any goods or services; or

(m) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3–2); or

(n) make a false or misleading representation concerning a requirement to pay for a contractual right that:

(i) is wholly or partly equivalent to any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3–2); and

(ii) a person has under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory (other than an unwritten law).

Note 1: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

Note 2: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5–3.

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation of a kind referred to in subsection (1)(e) or (f), the representation is taken to be misleading unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the representation is not misleading; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the representation is not misleading.

19 The conduct proscribed by s 18(1) of the ACL is the same conduct as was forbidden by s 52(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA).

20 Further, subsections 29(1)(i) and 29(1)(m) are, in substance, in the same terms as s 53(e) and s 53(g) of the TPA respectively.

21 The jurisprudence developed in respect of those TPA provisions continues to apply in respect of the equivalent provisions under the ACL.

The Relevant Case Law

22 A representation is misleading if it leads or is likely to lead the person or persons to whom it is made into error (Miller and Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 357 at 368 [15]). That is to say, there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the persons exposed to it (TPG at 651–652 [39]). There is no meaningful difference between the phrases “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” as used in s 18(1) of the ACL and “false or misleading” as used in s 29(1)(i) and s 29(1)(m) of the ACL (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73 at 81 [40] per Allsop CJ).

23 As the Full Court (French, Heerey and Lindgren JJ) said in SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 169 ALR 1 (SAP) at 14 [51]:

… The characterisation of conduct as “misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive” involves a judgment of a notional cause and effect relationship between the conduct and the putative consumer’s state of mind. Implicit in that judgment is a selection process which can reject some causal connections, which, although theoretically open, are too tenuous or impose responsibility otherwise than in accordance with the policy of the legislation. In some cases there will be a selection process analogous to that which arises under s 82 of the TP Act in a determination of whether or not a claimed loss was caused by a contravention: State Government Insurance Corp at FCR 562.

24 A representation is likely to mislead or deceive if it may be expected to or has a capacity or tendency to mislead or deceive. In such a case, likelihood means a real and not remote chance or possibility of having that effect (Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87 per Bowen CJ, Lockhart and Fitzgerald JJ).

25 Whether an advertisement is misleading is a question of fact to be decided having regard to all of the circumstances of the particular case (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2004) 208 ALR 459 (ACCC v Telstra) at 475 [49] per Gyles J). The Court must form a view as to what message would be conveyed to the target audience (ACCC v Telstra at 475 [49]).

26 At par 18 of its Written Submission in Chief dated 26 November 2014, the ACCC summarised the relevant principles in relation to the publication of advertisements as follows (footnotes omitted):

The relevant principles may be conveniently summarised as follows:

18.1. When considering an advertisement through the eyes of a reasonable consumer, the court must take into account that “an advertisement published to the world at large is designed and calculated to be seen and read by a wide range of persons”, especially in the case of internet advertisements;

18.2. The range of persons will include the shrewd and the ingenuous, the educated and the uneducated, the experienced and inexperienced in commercial transactions; it will include the astute, the informed, those who are sceptical and read the small print, those who are intelligent and those who are well informed, and it will also cover many who do not possess those characteristics and those who are less informed and those with average intelligence;

18.3. the question whether or not an advertisement is misleading is to be tested by the effect on a person, not particularly intelligent or well informed, but perhaps of somewhat less than average intelligence and background knowledge;

18.4. the court is not entitled to assume that the reader “will be able to supply for himself or herself omitted facts or to resolve ambiguities”, and an advertisement may be misleading even though it fails to deceive more wary readers.

27 I think that the ACCC’s summary which I have extracted at [26] above is an accurate summary of some of the relevant principles. I accept that summary as far as it goes.

28 In the present case, the impugned conduct comprises:

(a) Advertisements;

(b) Promotional activity;

(c) The presentation of certain webpages and the structure and layout of an online booking flow or process; and

(d) The presentation of pages on the airlines’ mobile sites and the structure and layout of the mobile sites’ booking flow or process.

29 Some of the conduct which is criticised is not properly characterised as the publication of advertisements. However, whatever label is placed upon the conduct, it is necessary for the Court, when endeavouring to assess the conduct against the statutory prohibitions, to identify the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct (Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 199 per Gibbs CJ). It is the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of that class who must be considered (Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 (Google) at 443 [7] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ) and Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 (Nike) at 85 [102]–[103] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ). The extremely stupid, the unusually gullible and those whose reactions are extreme or fanciful would not be included. The question is whether a not insignificant number of those persons are likely to have been led into error by the conduct as a matter of inference (Global One Mobile Entertainment Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 134; [2012] ATPR 42-419 at [108] per Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ).

30 The ACCC submitted that, in the present case, the relevant class of consumers was the public at large.

31 While it is true that the airlines’ websites were accessible to all members of the public who had access to the internet, it seems to me that the relevant class of consumers here comprised those members of the public who were interested from time to time in purchasing passage for a particular journey from a low cost airline.

32 The ACCC contended that, without disclosing the existence of the booking and service fee and the terms upon which that fee would be required to be paid, both airlines were likely to mislead reasonable or ordinary members of the class which I have described at [31] above into thinking (erroneously) that fares were available at the prices published on the airlines’ websites regardless of which of the available payment methods was chosen by the consumer in any given case.

33 A critical element in the ACCC’s argument is the proposition that, by the conduct of each airline, a dominant message was conveyed. The ACCC characterised the means by which that dominant message was conveyed as a “representation”. The ACCC said that the substance of the representation must be discerned by considering it in context. That context includes the medium in which the presentation is expressed (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1177 (ACCC v Singtel Optus) at [5] per Perram J). I agree that the alleged contravening conduct must be assessed in context. Whether the present cases should be regarded as falling within the “dominant message” category of cases is a matter of contest. The airlines submitted that the “dominant message” analysis was not apt in the present cases because, unlike advertisements, where the consumer’s mind is engaged only fleetingly with the subject matter, the potential purchaser of a cheap air fare will focus carefully on the booking process and tarry at particular points in that process for as long as may be necessary for that purchaser to satisfy himself that he has secured the best available deal. They submitted (correctly) that whether the “dominant message” analysis is apt is essentially a question of fact.

34 In Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 199, Deane and Fitzgerald JJ said:

It is, in the circumstances, unnecessary that we form or express any concluded view on the question whether it is a principle of the law of passing-off that deception must continue, or be likely to continue, to the “point of sale”. As a matter of principle and of logic, it is difficult to see why it should be. For the purposes of the present appeal, it suffices to say that, even if such a limitation should be recognized in the law of passing-off, we see no ground for importing it into the provisions of s 52 of the Act. In our view, it is sufficient to enliven s 52 that the conduct, in the circumstances, answers the statutory description, that is to say, that it is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. It is unnecessary to go further and establish that any actual or potential consumer has taken or is likely to take any positive step in consequence of the misleading or deception. That is not to say that evidence of actual misleading or deception at the point of sale and of steps taken in consequence thereof is not likely to be both relevant and important on the question whether the relevant conduct in fact answers the statutory description and as to the relief, if any, which should be granted.

(See also SAP at 14 [51] per French, Heerey and Lindgren JJ where the Full Court held that conduct may be misleading if it leads a consumer into error even though the true position is disclosed before the transaction is concluded.)

35 At 654–656 [47]–[52] in TPG, French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ said:

47 This case is in stark contrast to Puxu in three respects. First, TPG’s target audience did not consist of potential purchasers focused on the subject matter of their purchase in the calm of the showroom to which they had come with a substantial purchase in mind. Here, the advertisements were an unbidden intrusion on the consciousness of the target audience. The intrusion will not always be welcome. The very function of the advertisements was to arrest the attention of the target audience. But while the attention of the audience might have been arrested, it cannot have been expected to pay close attention to the advertisement; certainly not the attention focused on viewing and listening to the advertisements by the judges obliged to scrutinise them for the purposes of these proceedings. In such circumstances, the Full Court rightly recognised that “many persons will only absorb the general thrust” [TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 210 FCR 277 at 289 [103]]. That being so, the attention given to the advertisement by an ordinary and reasonable person may well be “perfunctory”, without being equated with a failure on the part of the members of the target audience to take reasonable care of their own interests.

48 Secondly, the Full Court did not recognise that the tendency of the advertisements to mislead was to be determined, not by asking whether they were apt to induce consumers to enter into contracts with TPG, but by asking whether they were apt to bring them into negotiation with TPG rather than with one of its competitors on the basis of an erroneous belief engendered by the general thrust of TPG’s message.

49 It might be said, as TPG did, that consumers, acting reasonably in their own interest, could be expected to obtain a clear understanding of their rights and obligations before signing up with TPG; but to say that is to confuse the question whether the consumer has suffered loss with the anterior question as to whether the advertisement, viewed as a whole, has a tendency to lead a consumer into error. Thus, in Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [(2009) 238 CLR 304 at 318 [24]; [2009] HCA 25] French CJ noted that the question of characterisation as to whether conduct is misleading is “logically anterior to the question whether a person has suffered loss or damage thereby”. French CJ observed that characterisation of conduct “generally requires consideration of whether the impugned conduct viewed as a whole has a tendency to lead a person into error” [Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 319 [25]]. As observed earlier in these reasons, questions of carelessness by consumers in viewing advertisements may be relevant to that question of characterisation.

50 It has long been recognised that a contravention of s 52 of the TPA may occur, not only when a contract has been concluded under the influence of a misleading advertisement, but also at the point where members of the target audience have been enticed into “the marketing web” by an erroneous belief engendered by an advertiser, even if the consumer may come to appreciate the true position before a transaction is concluded [Trade Practices Commission v Optus Communications Pty Ltd (1996) 64 FCR 326 at 338-339; SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 169 ALR 1 at 14 [51]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia (2003) 133 FCR 149 at 171-172 [47]. See also Bridge Stockbrokers Ltd v Bridges (1984) 4 FCR 460 at 475]. That those consumers who signed up for TPG's package of services could be expected to understand fully the nature of their obligations to TPG by the time they actually became its customers is no answer to the question whether the advertisements were misleading.

51 Thirdly, this is not a case where the tendency of TPG’s advertisements to lead consumers into error arose because the target audience might be disposed, independently of TPG's conduct, to attend closely to some words of the advertisement and ignore the balance. The tendency of TPG's advertisements to lead consumers into error arose because the advertisements themselves selected some words for emphasis and relegated the balance to relative obscurity. To acknowledge, as the Full Court did [TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 210 FCR 277 at 289 [103]], that “many persons will only absorb the general thrust” is to recognise the effectiveness of the selective presentation of information by TPG. The Full Court erred in failing to appreciate the implication of that finding.

52 It was common ground that when a court is concerned to ascertain the mental impression created by a number of representations conveyed by one communication, it is wrong to attempt to analyse the separate effect of each representation [Arnison v Smith (1889) 41 Ch D 348 at 369; Gould v Vaggelas (1984) 157 CLR 215 at 252; [1985] HCA 68; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199, 210-211]. But in this case, the advertisements were presented to accentuate the attractive aspect of TPG’s invitation relative to the conditions which were less attractive to potential customers. That consumers might absorb only the general thrust or dominant message was not a consequence of selective attention or an unexpected want of sceptical vigilance on their part; rather, it was an unremarkable consequence of TPG’s advertising strategy. In these circumstances, the primary judge was correct to attribute significance to the “dominant message” presented by TPG’s advertisements.

36 In ACCC v Telstra, at 478 [58], Gyles J said:

One aspect of this branch of the law which can be regarded as settled by authority is that advertising which is misleading is caught by the Act even if the effect of it is, or is likely to be, dispelled prior to any transaction being effected.

(See also Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1 (Cassidy) at 11 [17] per Mansfield J and at 18–19 [43] per Stone J.)

37 To similar effect were the following remarks made by Perram J in ACCC v Singtel Optus at [26]:

Nor, contrary to Optus’ submissions, is the misleading nature of the advertisement reduced by the statements Optus makes, or seeks to have made on its behalf, at the point of sale. As I have explained above, when dealing with the objections to the evidence, it is an error to ask whether consumers who purchased the product were misled. This is for practical reasons set out above – the capacity of the advertisement to induce people to begin dealing with Optus (rather than others) without necessarily closing the transaction – and also for the textual reason that s 52 simply does not contain any limitation about what it is that consumers must be misled into doing to contravene the prohibition. Accepting in Optus’ favour that some kinds of statements were made to consumers through the sales process and website this does not undo, in this case, the plainly misleading and deceptive nature of the advertisement. In that regard, I have found the evidence about the traffic across the website of little utility. For completeness, I reject also Optus’ contention, based on its survey evidence, that the time taken by consumers to make broadband purchasing decisions and their reliance upon on-line and other forms of research means that the advertisement should not be seen as being misleading. This is largely for the reasons already given – it gives no weight to the initial inducement the advertisement provides to head down the path with Optus and puts at nil the negative consequences for consumers and competitors alike of that form of enticement. Of course it is true that the purchase of a broadband plan is a substantial purchase rather than an impulse purchase although even that fact was kept in fairly small print at the bottom of the page. But even so, this is not sufficient to overcome the very misleading nature of the principal message.

38 The ACCC submitted that, where a price is advertised on the home page of a website and there is no disclosure of additional fees which have the effect of increasing the price until the consumer has been drawn into the website and commenced the booking process, the belated disclosure cannot negate or correct the effect of the otherwise misleading price representation on the home page. The ACCC claimed that this submission was supported by the observations of Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Nonchalant Pty Ltd (In Liq) [2013] FCA 605 at [34]–[35]. I think that the remarks which her Honour made at those paragraphs related specifically to the case with which her Honour was then dealing. Of course, her Honour’s observations may be apt to be applied in other cases. Whether that is so will depend upon the particular facts and circumstances of each case. However, I do not think that a principle of general application as wide as the ACCC’s submission can be extracted from the authorities.

39 In the case where a headline representation is sought to be qualified by other material, the qualifying material must be sufficiently prominent to prevent the headline representation from being misleading. The degree of prominence required will vary with the potential for the primary statement to be misleading (Cassidy at 17–18 [37]–[41] per Stone J). The overall impression created by the representation must be assessed.

40 In considering the impact of headline representations with qualifying information for the purposes of the New Zealand statutory provisions which correspond with s 18 and s 21 of the ACL, the New Zealand Court of Appeal in Godfrey Hirst NZ Ltd v Cavalier Bremworth Ltd (2014) 3 NZLR 611 (Godfrey Hirst) at 627–628 [59] held that:

In considering whether headline representations such as these breach ss 9 and 13(i) of the Act the following principles should guide a court:

(a) Overall impression: it is the “dominant message” or “general thrust” of the advertisement that is of crucial importance [ACCC v TPG, above n 46, at [45], [51] and [52]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Signature Security Group Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 3, (2003) ATPR 41–908 at [28] [ACCC v Signature Security].

(b) Wrong only to analyse separate effect of each representation: as a corollary from (a), when assessing the mental impression on consumers created by a number of representations in a single advertisement, it is insufficient only to analyse the separate effect of each representation [ACCC v TPG, above n 46, at [52], citing Arnison v Smith (1889) 41 Ch D 348 (CA) at 369; Gould v Vaggelas [1985] HCA 75, (1985) 157 CLR 215 at 252; Puxu (High Court), above n 17, at 199 and 210–11]. The overall impression cannot be assessed by analysing each separate representation in isolation.

(c) Qualifying information sufficiently prominent?: whether headline representations are misleading or deceptive depends on whether the qualifications to them have been sufficiently drawn to the attention of targeted consumers [ACCC v Signature Security, above n 67, at [25]]. This includes consideration of:

(i) the proximity of the qualifying information [ACCC v Signature Security, above n 67, at [26], citing George Weston Foods Ltd, above n 30, at [46]];

(ii) the prominence of the qualifying information [ACCC v Signature Security, above n 67, at [27]; National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investment Commission [2004] FCAFC 90, (2004) 49 ACSR 369 at [51]–[52] [National Exchange v ASIC]] and

(iii) whether the qualifying information is sufficiently instructive to nullify the risk that the headline claim might mislead or deceive [Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy [2003] FCAFC 289, (2003) ATPR 41-971 at [35]–[41]; Energizer NZ Ltd, above n 10, at [81]].

(d) Glaring disparity: where the disparity between the headline representation and the information qualifying it is great, it is necessary for the maker of the statement to draw the consumer’s attention to the true position in the clearest possible way [National Exchange v ASIC, above n 71, at [55], [58] and [62]; ACCC v Signature Security, above n 67, at [27]].

(e) Tendency to lure consumers into error: applying principles (a) to (d), the question for the court is whether the advertisement viewed as a whole has a tendency to entice consumers into “the marketing web” by an erroneous belief engendered by the advertiser, even if the consumer may come to appreciate the true position before a transaction is concluded [ACCC v TPG, above n 46, at [50], citing Trade Practices Commission v Optus Communications Pty Ltd (1996) 64 FCR 326 (FCA) at 338–9; SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1821, (1999) 169 ALR 1 at [51]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2003] FCA 1129, (2003) 133 FCR 149 at [47]; and Bridge Stockbrokers Ltd v Bridges (1984) 4 FCR 460 (FCAFC) at 475]. Enticing consumers into “the marketing web” includes, for example, attracting them into premises selling the advertiser’s product. Once a prospective customer has entered, he or she will often be more likely to buy. The misleading advertising would then have contributed to any sale. It must follow that rival traders would also have been prejudiced, although protecting them is not the aim of ss 9 and 13 [Trust Bank Auckland v ASB Ltd [1989] 3 NZLR 385 (CA) at 389; Commerce Commission v Noel Leeming Ltd HC Christchurch AP196/96, 21 August 1996 at 4–5; Zennith Publishing Ltd v Commerce Commission HC Auckland AP139/98, 20 November 1998 at 11–12; Taco Company of Australia Inc, above n 6, at 197–199; Commerce Commission v ABC Motor Group [2005] DCR 262 (DC) at [10]. That consumers could be expected to understand fully the limitations of the warranties by the time they actually purchased a carpet is no answer to the question whether the advertisement was misleading.

41 I find this distillation of appropriate guidelines most helpful. I intend to consider the present cases with these guidelines in mind.

Jetstar’s Conduct

Some General Introductory Remarks

42 The conduct of Jetstar relied upon by the ACCC as constituting contraventions of the ACL took place in connection with the use by Jetstar of three separate forms of communication, namely the Jetstar website located at the URL http://www.jetstar.com/au/en/home (Jetstar website), the Jetstar mobile site located at https://mobile.jetstar.com/ (Jetstar mobile site) and common-form emails sent to persons who subscribed to an email mailing list described as the “Jetmail” list (Jetmail).

43 The case propounded by the ACCC requires the Court to make findings as to the contents of certain communications made by Jetstar over those three media. The Court is also required to make findings as to the process by which consumers navigate the Jetstar website and the Jetstar mobile site.

44 All of these findings are properly characterised as findings as to the primary facts. The evidence as to the primary facts was not in dispute.

45 It was also the ACCC’s case, as pleaded and conducted at trial, that by making certain statements on its website, on its mobile site and in emails sent by Jetmail, in the circumstances in which those statements were made, Jetstar made certain representations to the public at large about the price of the air passenger services which it was offering to provide which were untrue and, for that reason, misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive potential purchasers of those services. The ACCC contended that, by its conduct, Jetstar represented that the price as initially disclosed by Jetstar was a firm price regardless of the method of payment ultimately used by the customer and that that representation was false because, in the case of payments made by widely available credit cards, debit cards and PayPal, a booking and service fee was payable in the amount of $8.50 per passenger per flight for domestic flights and $12.50 per passenger per flight for international flights. Further, the ACCC argued that, by its conduct, Jetstar also represented that the provision of passenger carriage services by air as offered by it was not subject to a condition which would alter the price of those services depending upon the payment method used and that that representation was false.

46 It was accepted by the ACCC that the requirement to pay the booking and service fee was disclosed at some point in the process prior to any particular transaction being entered into. In some cases, that requirement was disclosed more than once during the booking process.

47 The ACCC contended that the disclosures made by Jetstar during the booking process were not sufficient to negate the impact of the falsity of the representations as to price made early in that booking process and that, in effect, consumers were being drawn into a “web of negotiation” by the headline representations as to price which representations were false at the time when they were made.

48 The characterisation of Jetstar’s conduct urged upon the Court by the ACCC was not accepted by Jetstar. Jetstar argued at trial that it did not make the representations which the ACCC suggested should be teased out of Jetstar’s conduct and that, in any event, the disclosures made by it as to the nature and quantum of the booking and service fee were sufficient to dispel any misunderstandings on the part of some consumers concerning that fee.

The Primary Facts

49 In this section of these Reasons, I set out my findings as to the primary facts.

Jetstar Website Conduct

50 The ACCC chose to prove the primary facts relating to the Jetstar website by tendering in evidence a number of video captures taken by officers of the ACCC or consultants to it. On a number of occasions, an officer or consultant of the ACCC went to the Jetstar website and navigated that website in order to simulate the booking process that would be undertaken by a prospective customer of Jetstar who wished to make an online flight booking and, while moving through that process, took a video capture of all of the screens or webpages that presented themselves during that process. In this way, the Court was provided with evidence of:

(a) The configuration and layout of the website at the particular dates referred to in the Amended Fast Track Statement filed on 24 November 2014 in the Jetstar proceeding (Jetstar AFTS);

(b) The precise format of each screen or webpage presented to the consumer at each stage of the process including where relevant links, hyperlinks, font size and print colours; and

(c) A clear exposition of the steps involved in making an online booking via the Jetstar website.

51 I am satisfied that the video captures tendered in evidence by the ACCC provide a comprehensive, accurate and fair depiction of the online booking process using the Jetstar website at each of the times referred to in the Jetstar AFTS.

52 I shall now address the specific contraventions alleged against Jetstar by reason of its conduct in configuring its website in the manner in which it did as at the specific dates referred to in the Jetstar AFTS.

First Alleged Contravention (14 May 2013)

53 The first website contravention alleged against Jetstar relates to its conduct on 14 May 2013. The relevant allegations are made in pars 14 and 15 of the Jetstar AFTS. The evidence of the primary facts is found in the video capture of the booking process recorded on the DVD which is Ex JFC-1 to the affidavit of John Frederick Cream affirmed on 17 June 2014. At the time when he affirmed that affidavit, Mr Cream was the ACCC’s Assistant Director, Enforcement Group – Queensland.

54 The booking process revealed by Ex JFC-1 was as follows:

(a) A potential customer would go to the home page on the Jetstar website. Once the customer had the home page on the screen, the customer would see near the top of the home page a number of links displayed across the page. One such link or banner of interest was the banner on the far left of the page called “Flights”. Associated with that banner and already displayed immediately under it was a rectangular box headed “Book flights”. There was an opportunity to use the links provided in that box to navigate to the next webpage (“Select Flights”). Other links were provided under the headings “Planning & booking” and “What we offer”;

(b) Also on the home page, commencing at approximately one third of the way down that page, various “Hot Fares” were listed. These fares were shown as relating to specifically identified journeys and were always expressed as “From” a particular dollar figure. They were generally displayed in bold and large font. The dollar figure was in orange and the text in dark blue;

(c) In a rectangular box to the immediate right of the “Book flights” box, a number of special offers would appear in a rotating display;

(d) Once at the home page, the customer would be taken to the webpage entitled “Select Flights”. Generally, the customer would be taken to that webpage by inserting certain details of the desired flight into the rectangular box on the home page headed “Book flights” and by then clicking his mouse cursor on the link “Search for flights”. The details entered by the customer in the box on the home page were the origin and destination of the desired flights, the date of each flight and the number of adults and children (including infants) who would be travelling. Once those details were entered, the customer would click on the icon “Search for flights”. The customer would then be taken to the “Select Flights” webpage;

(e) Once at the “Select Flights” webpage, the customer would then be required to choose the most desired flights (forward and return) from a number of specific flights listed on that webpage which met the original criteria inserted into the box on the home page and which had seats available on them as at the date of the relevant inquiry. On the “Select Flights” webpage, there was specified against each identified flight a dollar figure under a heading in a box:

Starter

Economy cabin

What is included?

Each dollar figure listed on this webpage signified the fare for the particular flight to which it related and had a blank circle next to it (called a “radio button”) upon which the customer might choose to click his mouse cursor. If the customer clicked on any radio button, two things would happen more or less simultaneously. The first thing which would happen was that a side panel entitled “Booking Summary” would appear on the right-hand side of the screen. The first item in that side panel was headed “Total AUD” and showed the fare which the customer had chosen by clicking on the radio button adjacent to the particular fare. That fare was expressed as a specific dollar figure not as “from” a specific dollar figure. If, for example, the customer chose a flight which showed a dollar figure next to it of $139, the fare that would be shown in the Booking Summary side panel was that figure or that figure multiplied by the number of persons travelling. Under the heading “Fees & taxes”, $0.00 appeared. This made clear that “Fees & taxes” were included in the fare displayed in the Booking Summary side panel under the heading “Total AUD”. The other thing that would happen when a customer clicked on any radio button was that three vertical rectangular boxes would come onto the screen. Two of those boxes contained a list of extra services. One box contained a description of the services provided as part of the Starter fare. The Starter fare was the most basic (and thus the cheapest) fare on offer. The services provided as part of the Starter fare were the seat on the aircraft and the right to bring on board a small piece of cabin luggage. Each of the other two boxes contained a list of bundled services that might be provided by Jetstar at the election of the customer in each case for an extra payment in each case (Value Bundles). One or other of these Value Bundles might be added to the booking at this stage at the election of the customer.

On the “Select Flights” webpage as at 14 May 2013, there was a note under the table of available flights in the following terms:

Prices quoted are per adult passenger, in AUD and include airfare related surcharges, fees and taxes. Unless otherwise stated, fares are non refundable, limited changes are permitted charges apply. Starter fares include 10kg carry-on baggage. Additional fees apply for checked in baggage, which will be available for purchase on the next page. Adding checked baggage after booking costs more at the airport, over the phone and on our web site. 7kg per item cabin baggage limit applies on Qantas flights.

The same process would occur when the customer selected his return flight.

After the customer had made his choices in respect of each flight (including choices of extras in accordance with the Value Bundles offered), those choices would then be reflected in the Booking Summary side panel on the “Select Flights” webpage. As a minimum, the price shown for the Starter fare for each chosen flight would populate that Booking Summary side panel. In addition, any selected bundled extras would be included.

The total price for the chosen fares reflected in the Booking Summary side panel would also be prominently displayed outside the Booking Summary side panel at the bottom of this webpage in large coloured font immediately above the “Continue” link;

(f) The customer would then be directed to the webpage headed “Passengers”. On that page, the customer was required to enter the name, address and contact details of each passenger who was to travel on that booking. After that task was completed, the Booking Summary side panel would reflect all of the information inserted as a result of the choices made by the customer up to that point. However, the Booking Summary side panel would reflect only information of that kind. As at this point in the booking process, it would contain no reference to the booking and service fee. The Booking Summary side panel by now also would include a reference to “Additional Extras” which were to be addressed in detail by a later webpage. No amount for those items would be included at this stage. In addition, at the point when the customer left the “Passengers” webpage, the Booking Summary side panel would be populated with details of the customer’s baggage choice if that customer chose to pay for the right to check in his baggage;

(g) The customer would then be directed to the webpage headed “Seats”. On that webpage, the customer would be invited to indicate his seating preferences. The Booking Summary side panel would then expand as necessary so as to include the cost of seating choices (if any) made by the customer. Baggage and seating choices would appear under a heading “Optional Extras”;

(h) The customer would then be directed to the “Extras” webpage. On this webpage the customer would be offered a number of additional services not already covered by the choices offered earlier (travel insurance, hotels, rent-a-cars and other activities). If any of those “Extras” were selected, they would be added to the items listed in the Booking Summary side panel and the costs thereof factored into the specified cascading list of charges set out in that Booking Summary side panel. They would all appear under the heading “Additional Extras” and be individually itemised;

(i) The customer would then be directed to the “Payment” webpage. It is at this point in the booking process, for the very first time, that the customer would be apprised of the existence and quantum of the booking and service fee. When the customer left the “Extras” webpage, there was added to the Booking Summary side panel as the very last entry before the total an item:

Booking and Service Fee

$0.00

So, when the Booking Summary side panel first appeared on the “Payment” webpage, that item was already shown in that side panel although no amount would be specified until the customer had moved through all but the last step required to be taken on the “Payment” webpage;

(j) On this webpage, under a heading in bold font: “How would you like to pay?”, the following text appeared:

Please select a payment method below. Please note that payment cannot be split between different payment methods except for voucher and credit card; and voucher and POLi in Australia and New Zealand, for Jetstar Airways (JQ) and Jetstar Asia (3K) bookings in AUD or NZD.

We charge a Booking and Service Fee for some bookings completed online. The options below indicate whether a booking and service fee applies. Jetstar waives this Booking and Service Fee for all bookings paid for using a Jetstar MasterCard, Jetstar Platinum MasterCard, Jetstar Vouchers and some other forms of payment (as indicated below). We actively encourage our customers to pay using one of the payment methods for which no Booking and Service Fee applies.

As I have already mentioned, when the customer was first taken to the “Payment” webpage, the Booking Summary side panel had added to it as the very last item prior to the total the following text:

Booking and Service Fee |

$0.00 |

In the centre of the “Payment” webpage, the customer was given the option of paying for the booking which the customer desired by credit card, PayPal, POLi or Jetstar vouchers. Those options were presented to the customer in a series of horizontal rectangular boxes cascading down the webpage which were labelled appropriately. Immediately next to and to the right of each specific option and within the relevant horizontal rectangular box, a note appeared. For payment by credit card, the note was:

Pay with a Credit Card (Booking and Service Fee applies except for Jetstar MasterCard).

The note next to the PayPal option was in the following terms:

Pay via PayPal (Booking and Service Fee applies).

(k) The note next to the POLi and Jetstar vouchers method of payment simply stated that no booking and service fee was payable if either of those methods of payment was chosen. If the customer chose to pay by credit card other than Jetstar MasterCard, the customer was again reminded as soon as the customer hovered over the appropriate credit card’s icon that a booking and service fee was payable. In this way and at this point in the process, the customer would be told that, for each of the methods of payment where a booking and service fee was payable, the booking and service fee was AUD $17 per passenger per booking. This was the first occasion in the entire booking process when the quantum of the booking and service fee was disclosed.

55 I set out below an example of a completed Booking Summary which is generally in the form in which it would have existed immediately before payment:

The Second to Fifth Contraventions (February to June 2014)

56 Before specifically addressing these alleged contraventions, I note that, in July 2013, representatives of Jetstar met with officers of the ACCC in order to discuss concerns that the ACCC had raised with Jetstar about the disclosure of the booking and service fee on the Jetstar website. After that meeting, Jetstar made a number of changes to its website in an endeavour to address the ACCC’s concerns. Those changes were notified to the ACCC in September 2013 and implemented at about the same time.

57 In substance, the changes made by Jetstar to its website in September 2013 added additional text to its website at various points in the booking process. Notwithstanding these changes voluntarily effected by Jetstar, the ACCC took the view that the manner in which Jetstar addressed the booking and service fee on its website remained misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive consumers. The ACCC also considered that, even after these changes were made to the Jetstar website, Jetstar was continuing to make false statements about the cost of flights offered by it on its website.

58 For these reasons, the ACCC recorded a series of additional video captures. These captures were made on 21 February 2014, 13 March 2014, 14 March 2014, 19–21 May 2014 and on 2 June 2014. These captures comprise the evidentiary foundation for the second to fifth contraventions of the ACL specified by the ACCC in the Jetstar AFTS (pars 16 to 26 of the Jetstar AFTS).

59 I propose to deal with the second alleged contravention in a little detail and with the third, fourth and fifth alleged contraventions more briefly since the ACCC’s case in respect of each of these latter three contraventions essentially mirrors its case in respect of the second contravention.

60 The video captures tendered in evidence as to the configuration and layout of the Jetstar website on 21 February 2014 were recorded by Skye TianTian Wu on that day. Ms Wu had been retained by the ACCC as a consultant specifically to navigate the Jetstar website and to create the necessary video captures. Those captures were recorded on a DVD which became Exhibit Ex STW-5 to Ms Wu’s affidavit affirmed on 23 June 2014.

61 Ms Wu also created and recorded video captures from the Jetstar website on 13 March 2014 and on 14 March 2014. In addition, she recorded a video capture of the Jetstar mobile site on 21 March 2014. I shall return to that video capture later in these Reasons.

62 All of the video captures referred to at [61] above were recorded on Ex STW-5.

63 The contraventions which allegedly took place on 21 February 2014 in connection with the Jetstar website concern a Jetstar promotion described as the “Up in the air” sale.

64 That promotion was drawn to the attention of consumers in a horizontal rectangular box placed prominently on the home page of the Jetstar website. On the occasion when Ms Wu navigated the Jetstar website on 21 February 2014, the sale being advertised in the rectangular box to which I have referred was a one way flight from Brisbane to Melbourne (Tullamarine) for $79 on selected travel dates, checked baggage not included. The promotion itself was advertised in large print. At the bottom of the rectangular box but within the box there was a statement to the effect that conditions applied to the promotional sale.

65 If a consumer wished to ascertain the terms and conditions of the advertised promotional sale and endeavour to book a flight which was the subject of that sale, the consumer would navigate to the “Sales & special offers” webpage on the Jetstar website. This could be done by clicking on the “Special offers” link on the home page or by clicking on text at the bottom of the rectangular box at the top right-hand side of the home page (“^One-way, checked baggage not included. Selected travel dates and conditions apply”). On the “Sales & special offers” webpage, there was a long list of potential destinations and travel periods available through the “Up in the air” promotion. On that page, the title to the page “Sales & special offers” appears near the top of the webpage in large bold print. Underneath that title there were boxes for the consumer to insert the point of origin, destination, travel dates and promotional offer type in order to activate an inquiry through the website as to available dates. If a potential customer took that step, the list of flights which would then appear on this page would be reduced in number because the list would reflect the customer’s desired travel choices. Immediately under those boxes, the following text appears:

*Please note only departure and arrival points that are on sale or part of a special offer are shown in list.

Fares quoted are one way and only available online. Checked baggage [this is in orange colour print] is not included with Starter fares^ but may be added for a fee. Starter and Business fares are non-refundable. Starter Max and Business Max fares are refundable for a fee. All sale and special offer fares available until sale ends or sale or special offer is sold out. Please make sure you read the important information about sale and special offer fares [the last eight words are also in orange colour print].

66 Underneath the text which I have extracted at [65] above, a list of potential flights was set out. Underneath that list there was another reference to “Important information about sale & special offer fares”, also in orange print.

67 Underneath that text there appeared two photographs and some associated text. Underneath that, the following text appeared:

^Carry-on baggage limits [in orange print], including size restrictions, will be strictly applied. Passengers with more than the applicable carry-on baggage allowance will need to check in baggage [‘check in baggage’ in orange print], and charges will apply.

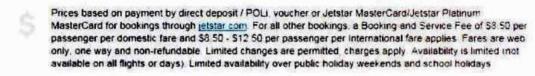

*Prices based on payment by direct deposit/POLi, voucher, Jetstar MasterCard or Jetstar Platinum MasterCard for bookings through Jetstar.com. For all other bookings, a Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger per domestic fare and $8.50–$12.50 per passenger per international fare applies. $32–$42 extra per passenger, per fare for bookings through telephone 131 538.

Fares are web only, one-way, Starter and Business fares are non-refundable. Limited changes are permitted, charges apply. Availability is limited (not available on all flights or days). Limited availability on public holiday weekends and school holidays. All travel on Jetstar is subject to the Jetstar Conditions of Carriage [‘Jetstar Conditions of Carriage’ in orange print].

Before you book your international flight, and before you travel, check current Government travel advisories on www.smartraveller.gov.au [‘www.smartraveller. gov.au’ in orange print].

To book, search in the relevant travel period and note that non-sale & special offer fares will also appear. Some sale & special offer routes may have very limited availability at lower fares.

68 The orange print above the list of available flights and immediately under the list of available flights constituted a link which, if clicked upon, would take the consumer to the text at the bottom of the same page under the heading “Important information about sale & special offer fares”.

69 The true position about the booking and service fee was therefore able to be ascertained by a consumer who either clicked on the links to which I have referred or who in any event read the terms and conditions under the heading “Important information about sale & special offer fares”.

70 The headline price shown in the last column across the page in the list of flights is in orange colour bold print.

71 In addition to the matters to which I have already referred, if a consumer were to click his mouse cursor on the entries in the column referable to the list of flights entitled “Sale or offer type”, he would be taken to another part of the website headed “Important Information”. The information to which the consumer would be taken, had that pathway been chosen, was in the following terms:

Important Information

Please refer to the sale and special offer table for travel dates. Prices based on payment by direct deposit/POLi or voucher for bookings through Jetstar.com. For all other bookings, a Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger per fare applies.

Fares quoted are one way and non refundable. Limited changes are permitted, charges apply. Limited availability, not available all flights or days. All travel on Jetstar is subject to the Jetstar Conditions of Carriage [‘Jetstar Conditions of Carriage’ in orange print].

Starter fares do not include checked baggage. For an additional $14.50–$45 per passenger, per fare you can choose between 15kg to 40kg checked baggage. Carry-on baggage limits [‘Carry-on baggage limits’ in orange print], including size restrictions, will be strictly applied. Passengers with more than the applicable carry-on baggage allowance will need to check in baggage [‘check in baggage’ in orange print].

72 If the potential customer clicked his mouse cursor on the words “Find Flights” (which is in black print and bold print) he would be taken to another part of the website which briefly and in summary form recorded the details of the desired flight. The consumer would then be taken to the “Select Flights” webpage which substantially mirrored the same webpage as at May 2013.

73 The ACCC accepted that Jetstar had accurately disclosed the existence and quantum of the booking and service fee on the “Sales & special offers” page to those consumers who managed to be taken to the relevant disclosures. However, the ACCC made the following observations about that webpage:

(a) Each row of the list of flights table ends with a “Find Flights” hyperlink which, once clicked, allowed travel dates to be selected and directed the consumer to the next page. For many customers, the booking flow was likely to entail the consumer scrolling through the table of fares to the desired flight and ending with the consumer clicking the “Find Flights” link at the end of the row showing the desired flight and fare. The point here being made is that many consumers would never naturally navigate to the text of the disclosures made on the “Sales & special offers” page or to the disclosure made on the other part of the website to which one would be taken if one clicked on the hyperlink under the heading “Sale or offer type”.

(b) Most consumers would be unlikely to hit upon the disclosure made on the second half of the “Sales & special offers” webpage because that disclosure did not manifest itself on the screen while the consumer was scrolling down the list of available flights and would not be seen if the consumer moved directly from that list to the “Find Flights” webpage.

(c) The links to the “Important Information” disclosed on the “Sales & special offers” page and in the linked box set out at [65]–[67] above were not sufficiently prominently displayed on the “Sales & special offers” webpage and thus would not have been seen as material to which the consumer should necessarily navigate.

74 When a potential customer of Jetstar arrived at the “Select Flights” webpage on 21 February 2014, the potential customer was required to select the desired travel dates by use of the date chart displayed on that webpage. When the customer’s mouse cursor hovered over a date in the chart, or when a date was actually selected, a small pop up box was immediately displayed showing the fare in large white text standing out from an orange background. The chart was designed to identify the cheapest flight in the timeframe and the price range of that flight. Underneath each chart displayed on the first part of this webpage, the following text appears:

Fares displayed are Starter fares with carry on baggage only. All prices are quoted per person in AUD, exclusive of any applicable infant fees. Prices include all airfare-related fees and taxes. Please check fare types and other conditions on the next page.

75 Once the flight details have been selected, the side panels on the right hand side of the date charts show in large text the price of the fare. The fare is described as a dollar figure per adult passenger.

76 By this stage of the booking flow, the consumer will have browsed the destinations available as part of the “Up in the air” promotion, selected a destination with a travel period convenient to the consumer, compared the fares in the date charts with the fares available on other dates and settled upon particular dates of travel offering the desired fare.

77 At the foot of this webpage, there was a booking summary headed “Quick Summary” which simply adverted to the dollar fare and nothing else.

78 In order to complete a booking pursuant to the promotional sale advertisement, the consumer was then required to confirm his flight details by moving to the next component of the “Select Flights” webpage. When the consumer clicked his mouse cursor on the selected flight on this webpage, an alert box immediately popped up entitled “Important booking information”. That box appeared immediately adjacent to and to the right of the selected fare. This alert box had a black background with white print. There was a red triangle with an exclamation mark and a red band across the black box. The contents of that pop up box were as follows:

A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger, per domestic flight and $8.50–$12.50 per passenger, per international flight applies in some circumstances .

Some products and services throughout our booking process have been pre-selected for your convenience .

79 The same pop up box was revealed when the customer confirmed his returning flight.

80 If a user hovered his cursor over the icon in the black box headed “Important booking information” immediately adjacent to the “1. Select departing flight” table, text describing the Booking and Service Fee appeared in the following terms:

For bookings in Australian Dollars, no Booking and Service Fee applies for bookings made using direct deposit/POLi, voucher or Jetstar MasterCard/Jetstar Platinum MasterCard. A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger, per domestic flight … applies for all other bookings …

81 If a user hovered his cursor over the icon in the black box headed “Important booking information” immediately adjacent to the “2. Select returning flight” table, text describing the Booking and Service Fee appeared in the following terms:

For bookings in Australian Dollars, no Booking and Service Fee applies for bookings made using direct deposit/POLi, voucher or Jetstar MasterCard/Jetstar Platinum MasterCard. A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger, per domestic flight … applies for all other bookings …

82 The following text appeared below the “1. Select departing flight” table on the “Select Flights” webpage:

For bookings in Australian Dollars no Booking and Service Fee applies for bookings made using direct deposit/POLi, voucher or Jetstar MasterCard/Jetstar Platinum MasterCard. A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger, per domestic flights … applies for all other bookings …

83 The same text appeared below the “2. Select returning flight” table.

84 Thereafter, the booking process followed much the same pathways as the standard pathways applied to non-promotional sales of flights which I have described earlier in these Reasons.

85 Thus, after the flight selections of the consumer were confirmed, the consumer was taken to the “Payments” webpage via the “Additional Extras” webpage. On that webpage, the following disclosures were made:

(a) Under the heading “How would you like to pay?”, the following text appears:

Please select a payment method below. Please note that payment cannot be split between different payment methods except for voucher and credit card, and voucher and POLi in Australia and New Zealand, for Jetstar Airways (JQ) and Jetstar Asia (3K) bookings in AUD or NZD.

For bookings in Australian Dollars no Booking and Service Fee applies for bookings made using direct deposit/POLi, voucher or Jetstar MasterCard/Jetstar Platinum MasterCard. A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50 per passenger, per domestic flight … applies for all other bookings … We actively encourage our customers to pay using one of the payment methods for which no Booking and Service Fee applies.

(b) In the table of payment methods, text appears next to each payment method indicating when a booking and service fee applied as follows:

(a) Next to “Credit Card” – text stating: “Pay with a Credit Card (Booking and Service Fee applies, except for Jetstar MasterCard)”; and

(b) Next to “PayPal” – text stating “Pay via PayPal (Booking and Service Fee applies)”.

(c) If the mouse cursor was hovered over and/or the user clicked on a credit card icon, text appeared indicating if a booking and service fee applied and any applicable amount in the following manner:

(a) The “Jetstar MasterCard” icon – text stating “There is no booking and service fee with a Jetstar MasterCard”;

(b) The “Visa” icon – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for Visa Credit Cards”;

(c) The “MasterCard” icon – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for MasterCard Credit Cards”;

(d) The “Diner’s Club International” icon – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for Diner’s Club”;

(e) The “American Express” icon – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for American Express Cards”; and

(f) The “UATP” icon – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for UATP Credit Cards”.

(d) Once two credit card numbers were entered into the credit card number field, text appeared indicating if a booking and service fee applied, as follows:

(a) Visa – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for Visa Credit Cards”;

(b) MasterCard – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for MasterCard Credit Cards”;

(c) Diner’s Club International – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for Diner’s Club”; and

(d) American Express – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for American Express Cards”;

(e) UATP – text stating “AUD $17.00 per passenger per booking applies for UATP Credit Cards”.

(e) After the sixth credit card number was entered, the Booking Summary side panel was automatically updated to include the amount of any applicable booking and service fee.

(f) If a customer chose to pay by Jetstar MasterCard, once two credit card numbers were entered, text appeared indicating that a booking and service fee applies. After six credit card numbers were entered (sufficient to identify the card as a Jetstar MasterCard), the text changed to “There is no booking and service fee with a Jetstar MasterCard”.

(g) Once PayPal was selected as the payment method, text appeared stating “Booking and Service Fee: $17.00 per passenger per booking”.

86 A customer might also navigate to a webpage entitled “Fees and charges” by clicking on the “Planning & booking” banner on the Jetstar home page and then on the “Fees and charges” webpage which is listed under the general heading “Fares”. If a customer were to find the “Fees and charges” webpage, the customer would find reference to the booking and service fee together with the following text:

Jetstar charges a Booking and Service fee for some bookings completed online. For bookings made in Australian Dollars (AUD), Jetstar waives this Booking and Service Fee for all bookings paid for using Jetstar MasterCard, Jetstar Platinum MasterCard, Jetstar Vouchers, POLi and Direct Deposit (Direct Deposit is available up to 14 days prior to departure only). A Booking and Service Fee of $8.50AUD per passenger per domestic fare and $8.50–$12.50 per passenger per international fare applies for bookings completed with any other payment type. We actively encourage our customers to complete their bookings using one of the payment methods for which no Booking and Service Fee applies. For more information, see Payment Methods.

87 A similar state of affairs obtained in respect of a further webpage entitled “Payment methods”. A consumer would find that webpage by clicking his mouse cursor on the “Planning & booking” link displayed at the top of the screen at various points in the process and then navigating to the “Payment methods” webpage. In the event that a consumer did navigate to that page, the following disclosures were apparent:

(a) Under the heading “Credit, debit and charge cards”, the following text appeared:

Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Diners Club and UATP cards are accepted, including credit cards, debit cards and charge cards. A Booking and Service Fee will apply. If you pay with a Jetstar MasterCard of Jetstar Platinum MasterCard you’ll avoid the Booking and Service Fee. …

See the Fees & Charges page for more details on the Booking and Service fee.

(b) Under the heading “PayPal”, the following text appeared: