FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell [2015] FCA 1110

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

COMITÉ INTERPROFESSIONNEL DU VIN DE CHAMPAGNE Applicant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 October 2015 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant within 14 days of the date hereof file and serve proposed minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons including on costs and for the further conduct of the matter, together with written submissions (limited to five pages).

2. The respondent within 14 days of the receipt of the applicant’s proposed minutes of orders and submissions file and serve her proposed minutes of orders, together with written submissions (limited to five pages).

3. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1373 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | COMITÉ INTERPROFESSIONNEL DU VIN DE CHAMPAGNE Applicant |

AND: | RACHEL JAYNE POWELL Respondent |

JUDGE: | BEACH J |

DATE: | 20 october 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (CIVC) represents the interests of growers, producers, negociants and merchants of Champagne wines.

2 Rachel Jayne Powell provides wine education services, including event management and consulting services focused on wine. She promotes herself and wines under her title and alter ego Champagne Jayne.

3 The CIVC alleges that by the way Ms Powell has promoted herself and used the name Champagne, she has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct and made false representations in contravention of ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL). It further alleges that by the way she has used the name Champagne, Ms Powell has advertised wines under a false or misleading description in contravention of ss 40C and 40E of the Australian Grape and Wine Authority Act 2013 (Cth) (AGWA Act).

4 This proceeding is not a trade mark case in which the CIVC is relying on any statutory rights that have been infringed. Moreover, it is not a passing off case.

5 It is also important to emphasise other features about what this case is not. In particular:

(a) It is not about preventing Ms Powell from calling herself Champagne Jayne, although initially the CIVC put a broader case.

(b) It is not about preventing Ms Powell from referring to or using the name Champagne, providing that it is done in a non-misleading way.

(c) It is not about the CIVC asserting a monopoly in the use of the word Champagne. It has no such monopoly.

(d) It is not about preventing Ms Powell from educating the public or consumers about the attributes of Champagne wines or sparkling wines or differences or similarities between them or preventing Ms Powell from promoting Champagne wines or sparkling wines as such, providing that it is done in a non-misleading way. In these reasons, “Champagne wines” is a reference to wines produced in the Champagne region of France, made in accordance with French laws and entitled to bear the name Champagne and “sparkling wines” is a reference to all non-Champagne sparkling wines.

6 Essentially the CIVC’s case has three limbs.

7 First, that Ms Powell engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct by representing that she had an affiliation with the Champagne sector (the sector represented by the CIVC) that she did not have. In summary, I have rejected this case, save for one aspect dealing with Ms Powell’s use of the title “ambassador”; but that issue seems now to have been rectified such that I am unlikely to grant a remedy.

8 Second, that Ms Powell engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in her use, reference to and promotion of sparkling wines in the context of also referring to or using the name Champagne. I have accepted the CIVC’s case on this aspect in relation to some of Ms Powell’s use of social media.

9 Ms Powell’s use of social media in the promotion and provision of her services and related activities under the name “Champagne Jayne” has been likely to mislead or deceive consumers in terms of her promotion of, and reference to, sparkling wines.

10 That conduct has been carried out in the setting where she has:

(a) used her description “Champagne Jayne” to self-promote and to promote the provision of her services;

(b) used and referred to connections with producers of Champagne wines and more generally the Champagne industry;

(c) used the glamour, Frenchness and accoutrements otherwise associated with Champagne wines and the name Champagne.

11 In that setting she has in the same context referred to and promoted both Champagne wines and sparkling wines or referred to and promoted sparkling wines separately without making it clear that they were not Champagne wines.

12 Such conduct was likely to mislead or deceive actual or potential consumers of Champagne wines or sparkling wines in contravention of s 18 (but not s 29) of the ACL. There are different classes of consumer to consider, namely:

(a) First, those persons who did not know the difference between such wines. For those persons, her conduct fed into and reinforced, or was likely to have fed into and reinforced, their misconception that there was no difference (i.e. a sparkling wine could be considered to be a Champagne wine even if it did not come from the French region and was not produced with the required method).

(b) Second, those persons who knew the difference, namely that Champagne wine had to be produced from the French region using the precise method. Such persons would not have been misled or deceived by her conduct.

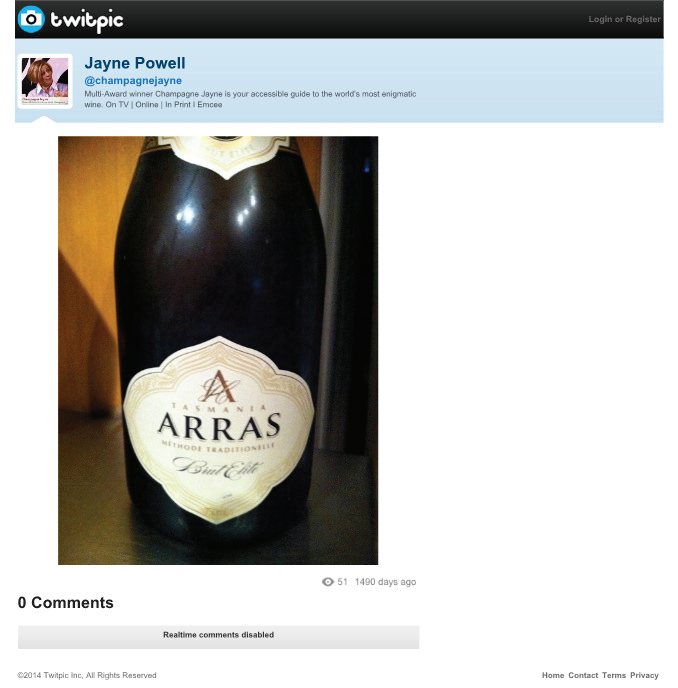

(c) Third, those persons who had a vague or unclear appreciation of the difference. Such persons may have been misled or deceived by Ms Powell into thinking that she was referring to Champagne wine when she extolled the virtues of sparkling wine such as Arras sparkling wine (produced in Tasmania) without making it clear that it was not Champagne.

13 Third, I have rejected the CIVC’s case concerning the alleged contraventions of ss 40C and 40E of the AGWA Act.

14 Before proceeding further, it is appropriate to record several matters dealing with how the trial progressed. The trial proceeded in two phases. After opening addresses and all evidence, the parties requested that I adjourn the matter for some months and to make a further reference to mediation. I acceded to that request and made the reference. Earlier this year and before the mediation, a request for pro bono assistance was made by Ms Powell. I made a reference under r 4.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) given the complexity and the significance of the issues. The mediation was unsuccessful. Final addresses then took place at a reconvened hearing. I am grateful for the assistance given by pro bono counsel. I should also note that during the currency of this litigation Ms Powell has been under no interlocutory injunction and has been free to pursue whatever course she perceived appropriate. Finally, the parties have requested that I postpone all questions of relief until after they have considered these reasons.

15 For convenience, these reasons are divided into the following sections:

The parties ([16] to [40]);

Champagne — background ([41] to [90]);

Appellations of origin ([91] to [99]);

The name Champagne in Australia ([100] to [113]);

CIVC’s activities in Australia ([114] to [123]);

Ms Powell’s business ([124] to [130]);

Social media ([131] to [142]);

How has Ms Powell promoted herself? ([143] to [163]);

Relationship with Arras ([164] to [166]);

Applicable legal principles: ACL ([167] to [184]);

What is the relevant class? ([185] to [199]);

Represented affiliation and ambassadorship ([200] to [216]);

Consumers and their understanding of “Champagne” ([217] to [229]);

Conduct in relation to sparkling wines ([230] to [275]);

Alleged contraventions of the AGWA Act ([276] to [330]);

Conclusion ([331] to [338]).

The parties

The CIVC

16 The CIVC is a statutory corporation of the Republic of France. In English, the name of the CIVC is the “Interprofessional Committee of Champagne Wine”. In France, the term “interprofession” is used in the wine sector to describe an association of growers, producers, merchants (or negociants) connected with particular wines or groups of wines. The CIVC is the interprofessional association for all growers, producers and negociants of Champagne wines and merchants who deal in Champagne wines.

17 Before 1900, there were a number of associations in the Champagne region which were involved in the protection of the name Champagne both in France and overseas. There were also a number of groups of growers and producers/merchants who took collective measures to fight against a phylloxera epidemic at that time and to replant the Champagne vineyards.

18 In the 1930s, a Champagne Wine Publicity and Defence Committee was established. This Committee was made up of representatives of vignerons and producers.

19 In 1935, a number of vineyard owners and other business operators involved in the trade in Champagne wines established a committee known as the Comité de Châlons, which was constituted by an equal number of representatives of vignerons on the one hand and producers and merchants on the other hand. This committee’s role was to regulate the Champagne market and to deal with production surpluses and shortfalls which could cause major fluctuations in grape prices. This committee was the predecessor of the CIVC.

20 The CIVC was created as an interprofession under French law on 12 April 1941 (1941 Law). The 1941 Law conferred on the CIVC “personalité civile” (legal personality). Accordingly, the CIVC is a legal entity. It is entitled to sue in its corporate name. It represents all growers, producers and negociants who deal in any Champagne wines for various purposes, including instituting and defending Court proceedings in France or abroad. In the proceeding before me, no issue has been taken concerning its separate legal personality and status and the recognition thereof under Australian law. Moreover, no issue has been taken concerning its standing and entitlement to pursue the statutory remedies sought in the present case.

21 The CIVC is based in Epernay and represents the professionals from the Champagne region. It was created to give those persons it represents a forum to meet, discuss and resolve issues and to address common problems. It was also created to facilitate joint marketing and promotion of the wines of the Champagne region. Further, the protection of the intellectual property in the name Champagne is also a part of the work done by the CIVC. There are currently over 110 full-time employees of the CIVC.

22 The CIVC’s functions are set out in the 1941 Law (as amended). There are also a number of regulations (known in French as “arrêté ministériel”) that deal with the functions and operations of the CIVC such as the Arrêté Ministériel of 20 July 1946 and the Arrêté Ministériel of 20 February 1986.

23 Article 8 of the 1941 Law (as amended) charged the CIVC with the functions of inter alia:

(a) contributing to the organisation of production and ensuring improved co-ordination of the market releases of products;

(b) organising and regulating the relationship between the various professions within the Champagne sector;

(c) improving operation of the market by establishing the rules for placing products in reserve and/or the staggered release of products;

(d) contributing to the quality and traceability of grapes, musts and wines;

(e) encouraging the sustainable development of wine growing, environmental protection and rational redevelopment of vineyards;

(f) deciding whether to issue professional accreditations; and

(g) undertaking information, communication, development, protection and defence campaigns in favour of the pre-determined Champagne registered appellations of origin.

24 Taking these prescribed functions into account, the activities of the CIVC have included:

(a) undertaking studies concerning the production and commercialisation of Champagne wines;

(b) playing a consultative role to public authorities in questions relating to regional viticultural and vinicultural matters;

(c) providing technical and practical assistance to growers, wine makers and negociants necessary to improve the vines and the quality of Champagne wines;

(d) developing the reputation of and the demand for Champagne wines in France and internationally; and

(e) undertaking legal steps to protect or defend the interests of those persons whom the CIVC represents, and particularly the name Champagne.

25 Pursuant to the 1941 Law, the CIVC has the power to make regulations relating to the Champagne trade which have the force of law.

26 All the vignerons of the Champagne area (which number about 15,000) and all “maisons de Champagne” (Champagne traders) (numbering 300 or thereabouts) are required by law to subscribe to the CIVC. The CIVC is funded by compulsory charges or levies, as provided for by Article 14 of the 1941 Law (and the regulations as referred to in that Article).

27 In terms of the CIVC’s management structure, pursuant to Articles 3, 4 and 5 of the 1941 Law, the CIVC consists of an Executive Committee and a Permanent Committee, the members of which are appointed by the French Minister of Agriculture.

28 The Executive Committee is the decision making arm of the CIVC. In accordance with Article 4 of the 1941 Law, the Executive Committee consists of twelve persons, six of whom represent growers and six of whom represent producers/merchants.

29 The Executive Committee meets five or six times each year and reports to the Permanent Committee.

30 The Permanent Committee consists of two members who are nominated by the Minister of Agriculture. One is the Chairman of the Vignerons Syndicate and the other is the Chairman of the Negociants/Merchants Union. These two delegates, known as presidents, are responsible for setting the strategy of the CIVC.

31 The day-to-day activities of the CIVC are supervised by its Board of Directors. Presently, the members of the Board of Directors are the General Director of the CIVC and the Directors of the following sections of the CIVC: Finance, Technical, Communication and Legal and Economic.

32 Decisions of the CIVC are given the power of law by being incorporated into a French law including a decree or regulation.

33 The CIVC’s work also has an international dimension. In particular, the CIVC has sought to protect the name Champagne (and the goodwill associated with it) and to promote the interests of the Champagne sector in many countries around the world. Much of this work is carried out through Champagne Bureaus that are funded and operated by the CIVC. Presently, the CIVC operates such Bureaus in Australia, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, China, Spain, the United States of America, India, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Russia and Switzerland. I will elaborate on this later.

34 The CIVC has taken action in many instances for the tort of passing off in relation to the alleged misuse of the name Champagne; see for example J Bollinger v Costa Brava Wine Co Ltd [1960] 1 Ch 262, J Bollinger v Costa Brava Wine Co Ltd (No 2) [1961] 1 All ER 561 and Wineworths Group Ltd v Comite Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne [1992] 2 NZLR 327. The CIVC has also previously taken action in Australia asserting a claim for misleading or deceptive conduct concerning the use of the name Champagne by a local distributor of Spanish Champagne (see Comite Interprofessionel du Vin de Champagne v NL Burton Pty Ltd (1981) 38 ALR 664 (and on appeal, unreported, on 2 July 1982)). Proceedings have also been taken by producers of Champagne asserting the tort of passing off; see Taittinger SA v Allbev Ltd [1993] FSR 641 and HP Bulmer Ltd and Showerings Ltd v J Bollinger SA [1978] RPC 79.

Ms Powell

35 In May 2003, Ms Powell launched her own Sydney-based wine education and entertainment events consultancy. At that time, she adopted her apparently long-time personal nickname, “Champagne Jayne”. It could be described as her “stage” name.

36 Subsequently, Ms Powell has been engaged in the following types of activities:

(a) posting articles and reviews in relation to wine on her website located at the domain name www.champagnejayne.com (the Website);

(b) posting content in relation to wine on social media (Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and Vine);

(c) appearing at and conducting wine related events (tastings, lunches, dinners, corporate functions and the like).

All of these activities are and have been conducted by Ms Powell under the name Champagne Jayne. On 4 November 2009, Ms Powell registered that name as a business name pursuant to the then Business Names Act 2002 (NSW).

37 During 2009 to 2011, Ms Powell wrote a book called “Champagnes, Behind the Bubbles”, which won the Gourmand 2011 Best French Wine Book (Australia) Award at the Gourmand World Wine Book Awards in Paris.

38 In February 2012, Ms Powell won an award as Harpers Champagne Educator of the Year by Harpers Champagne Summit Awards in London.

39 In early September 2012, in France, Ms Powell was conferred the honour and title “Dame Chevalier” by the Ordre des Coteaux de Champagne (OCC). The title is not one conferred by the French State. The OCC is an independent and separate legal entity with no legal connection to the CIVC.

40 Ms Powell is and has been a knowledgeable commentator and supporter of the Champagne sector and its products. But she has also shown an interest in and promoted sparkling wines whilst at the same time using her name and persona Champagne Jayne and in the context of other references to the name Champagne and Champagne wines. I will return to the detail of this later as it is that behaviour that is central to the CIVC’s concerns in the present case.

Champagne — background

41 What follows in this section is an uncontroversial description of several background matters. It is drawn from the material in evidence, facts of which I have taken judicial notice and inferences drawn from both, separately and collectively.

(a) The Champagne region

42 The Champagne production area lies about 150km to the east of Paris, consisting of 34,000 hectares of vineyards spread across 319 villages (crus), which have the right to make Champagne, of which 17 rank as “Grands Crus” and 44 rank as “Premiers Crus”. There are four main growing regions: The Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, Côte des Blancs and Côte des Bar. The main cities are Reims and Epernay.

43 The Champagne region lies at the northernmost limit of feasible vine cultivation for Western Europe. The limit is a function of temperature and available sunshine. The average annual temperature is just 11°C. The mean number of sunshine hours per year is 1,680, which is impoverished by Australian standards. Vineyards are planted at altitudes of 90 to 300m, predominantly on south, east and southeast facing slopes to maximise the available sunshine.

44 The subsoil in the Champagne region is mostly limestone. Such terrain provides good drainage.

45 Essentially, three grape varieties are used: Pinot noir, Meunier and Chardonnay; Arbanne, Petit Meslier, Pinot blanc and Pinot gris are used sparingly. Since the phylloxera epidemic in the late 19th century, vine stocks have been obtained from grafting together French and American vines. Phylloxera vastatrix destroys the root system of vines; in the Champagne region, vines are now grafted onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks. The regulations for vine spacing specify a maximum inter-row spacing of 1.5m and an intra-row spacing of 0.90 to 1.5m. The average planting density is about 8,000 plants per hectare.

(b) Photosynthesis and sugar content

46 For wine and ultimately Champagne wine production there must be a minimum level of sugar (glucose and fructose) in the grape. The potential alcoholic content for the wine produced from the grape is a function of its initial sugar content. Of course, one can enhance the natural sugar content of the grape by later addition of sugar i.e. sucrose (cane sugar or beet sugar) to the juice produced from the grape (chaptalisation) or the wine produced from the juice (dosage).

47 For a wine to claim a particular appellation, it must have a minimum alcoholic degree. Accordingly, the grapes used must have the required sugar content. Accordingly, the grapes must have adequately ripened to the necessary level and in the right conditions.

48 What conditions or process determines sugar content? Photosynthesis.

49 Photosynthetic production of the vine depends on the light energy received by the leaves, on temperature and on water availability in the soil. Oxygenic photosynthesis is the mechanism (as opposed to the anoxygenic mechanism). There are two types of reactions that take place.

50 First, there are the “light reactions” that consist of electron and proton transfer reactions. Photons excite the electronic state of antenna pigment molecules in chlorophyll. The electronic excited state is transferred over the pigment molecules as excitons. Some excitons are trapped by a “reaction centre” protein which the pigment molecules are anchored to. The trapped excitons provide the energy for the primary photochemical reaction of photosynthesis. The energy kickstarts a series of rapid electron transfer reactions, ultimately causing the removal of electrons from H2O and the release of O2. The transfer of electrons from water molecules then produces the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Ultimately, most of the light energy is stored as a form of chemical free energy (redox free energy) in NADPH. Further, aspects of the electron transfer reactions concentrate protons in a complex membrane system (consisting of protein complexes, electron carriers and lipid molecules) and create an electric field involving a “proton gradient” across the membrane. This enhances the electrochemical potential of the protons. The energy “stored” in such potential is then used to ultimately produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In summary to this point, light energy has been converted to chemical energy stored in NADPH and ATP. And as part of this process, O2 has been produced (hence an oxygenic mechanism).

51 Second, there are the “non-light reactions” which use the chemical energy produced from the “light reactions”. Atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into the organic carbon by the biochemical conversion of CO2 to a carbohydrate (and ultimately various types of sugars). Reduction of carbon occurs. The energy for this reduction is provided by the energy rich molecules that are produced from the “light reactions”, being ATP and NADPH which provide the source for chemical bond energy. This achieves the required re-arrangement of covalent bonds between carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. This carbon reduction mechanism can occur in the dark. It is known as the Calvin cycle. Various sugars are produced, which are then used for:

the growth of the branches and their components;

the root system;

energy for the metabolism of the system as a whole;

relevantly for present purposes, storage within the grape in the form of glucose and fructose.

52 As I say, this photosynthetic production depends on the light energy received, on temperature and on water availability in the soil. Because of the environmental conditions of the Champagne region, being predominately its coolness and reduced sunshine, the amount of sugar content and the rate of ripening of the grapes may be more problematic than for other regions. Accordingly, drier wines are generally produced, although the sugar content can later be enhanced if desired.

(c) How to make Champagne

Step 1 — Pressing

53 The first step is pressing the grapes that have been harvested. Champagne presses range in capacity from 2,000 to 12,000kg of whole grapes. They are mechanical and computer controlled horizontal presses, having replaced manually operated vertical basket presses.

54 The production of the white wine from the grapes (two thirds of the harvest of which are in fact black-skinned) requires adherence to five principles: pressing immediately after picking; whole cluster pressing; a gentle, gradual increase in pressure; low juice extraction; and fractionation, where the clearer and purer juices are drawn off at the beginning of pressing and separated from those produced at the end.

55 Juice extraction is limited to 25.5 hectolitres per 4,000kg marc; the “marc” is a unit of measurement for a press-load of grapes. The extraction process separates the first pressing juice (cuvée) of 20.5 hectolitres; the expression “cuvée” is also used to describe a precise blend of several base wines. Then the second pressing juice (taille) of five hectolitres is extracted. The cuvée is the purest juice of the pulp, rich in sugar, tartaric acid and malic acid. Cuvée musts (grape juice) are said to produce wines with finesse, subtle aromas, a refreshing palette and good aging potential. Contrastingly, taille musts have a lower acid content and higher mineral content. They produce more intense aromatic wines that are fruitier in youth than those made from cuvée, but less age-worthy due to the lower acid content.

56 Before proceeding further, I should also say that one way to make rosé Champagne wine is via maceration at this point. Grape solids are soaked in their juice to allow the red pigment (anthocyanins) to dissolve into the juice prior to fermentation (99% of all grape juice of whatever colour grape skin is clear-grayish in colour). Destemmed black-skinned grapes are left to macerate in a tank for some 24 to 72 hours to achieve the desired colour. The other way to make rosé Champagne is to add red wine to the blend of base wines at the assemblage stage (see step 4).

Step 2 — Clarification (débourbage)

57 The extracted juice is treated with sulphites, which act as a dual-function preservative. Their antiseptic properties inhibit the growth of bacteria. Their antioxidant actions safeguard the physicochemical properties of the wines ultimately produced.

58 Settling or clarification (débourbage) of the juice is then allowed to occur prior to fermentation. In the first few hours the juice is cloudy. This is, in part, due to enzymes that are naturally present in the juice. There are also particles suspended in the juice including particles of grape skin and seed. After 12 to 24 hours, the clear juice is drawn off; most of the flocculated matter will have formed a sediment at the bottom.

59 The clear juice is then further clarified by fining. A suitable agent is added that takes advantage of the adsorption properties of the agent to remove the remaining particles in suspension.

60 The clarified musts are then transferred to the fermenting vats for the first stage of fermentation.

Step 3 — Primary fermentation

61 To produce Champagne wines there are two fermentation stages. Let me discuss the first of these.

62 The primary fermentation process mostly occurs in thermostatically controlled stainless-steel vats. Fermentation now rarely takes place using oak casks or tuns.

63 There are various additions made to the juice.

64 First, sugar may be added to raise its degree of potential alcohol so that the wine produced ultimately contains a minimum alcohol level of around 11%; this is known as chaptalisation.

65 Second, various yeasts (unicellular microorganisms) are added, either in liquid form or as a dried active yeast. This produces controlled fermentation. Simply described, the yeasts metabolise the sugar in the juice, producing CO2 and ethyl alcohol (ethanol). Further, longer hydrocarbon chain alcohols than ethanol and esters (a chemical produced by an acid reacting with alcohol) are also produced that have a major effect on aroma and flavour. When all or most of the sugar in the juice has been transformed into alcohol, “wine” may be said to be produced. The CO2 produced would normally bubble out of solution, but later in the process of making Champagne wine, CO2 is “trapped”.

66 The process takes about a fortnight. Because the reaction is exothermic, it has to be controlled to ensure that temperatures do not rise above about 20°C; above such levels, fermentation may be chemically countermanded.

67 After this fermentation process, what is described as malolactic “fermentation” may take place where malic acid is broken down into lactic acid; this is not, however, strictly a fermentation. The idea is to convert the sharp malic acidity to the softer lactic acidity. I should say that the primary natural acid in grapes (and the wine) is tartaric acid, with malic acid the second most abundant. Generally, acidity is important for two reasons. First, it is the “backbone” of the wine; acidity contributes to a wine’s aging ability. Second, there is the question of taste. The sour taste of acidity is said to be a counterpoint to the sweet taste from the sugar and, less so, consequent alcohol.

Step 4 — Assemblage

68 After fermentation, the blending of different wines, known as assemblage, then takes place.

69 The wines (base wines) may be blended from different varieties of grapes, different vineyards and different vintages depending upon the type of Champagne wine sought to be produced. Many base wines (up to hundreds), which at this stage are only still wines (vin clair), may be blended. This is an art. The size, diversity and history of the Champagne region (including the stores of reserve base wines) is conducive to maximal choice and creativity on a scale that is unlikely to be available elsewhere.

70 Decisions are required as to whether to produce vintage Champagne wines (wines from the same year grape harvest) or non-vintage (blending wines from different grape harvest years).

71 Once blending is completed, the wine must be stabilised. This is done by chilling. The aim is to crystallise any tartaric salts (tartrate crystals) and then to remove them. The idea is to prevent crystallisation of such salts in the bottled Champagne wine as it affects appearance. Depending on the method used, stabilisation may take place up to a week.

Step 5 — Bottling (tirage)

72 Just before bottling, a solution known as “liqueur de tirage” is added. This is a mixture of still wine with cane or beet sugar. Also added is some further yeast. This solution is designed to induce the second stage fermentation within the bottle. Additives are also used to assist in the “remuage” process (riddling) described in step 6. Bentonite is used to make the sediment produced in the bottle heavier; this encourages it to slide down the neck of the bottle towards and near the cork.

73 Bottling then takes place. The bottles used are of strong glass to withstand the high pressure. At room temperature, the pressure inside a finished bottle may be up to six atmospheres (one atmosphere equals 14.7 pounds per square inch) predominantly produced from, inter alia, the partial pressure of CO2 within the bottle. Bottles may range from a standard size to a Magnum (two bottles), Jeroboam (four bottles), Methuselah (eight bottles), Balthazar (16 bottles) or a Nebuchadnezzar (20 bottles).

74 Once the bottles are filled, they are hermetically sealed (but not completely) with a stopper (bidule) held in place by a crown cap. The bottles are then transferred to a cellar and then stacked “sur lattes” (horizontally). Inside the bottles for the next six to eight weeks, the wine undergoes a second fermentation. Again, yeasts metabolise the further added sugar to produce ethanol and CO2.

75 A principal feature of Champagne wine production is this second stage fermentation process within the bottle. Moreover, it must occur within the same bottle which is then sold as the Champagne wine.

76 The bottled wines spend a minimum of 15 months maturing in the cellar. In part, this is to allow maturation on the lees. Once all sugars added by the liqueur de tirage have been consumed, the yeast cells are broken down and destroyed by a chemical process known as autolysis. The lees are the deposits of spent and broken down yeast cells left over after the second fermentation stage. It is said that the lees are nourishing and function as a natural antioxidant. It is said that this period of aging on the lees is important to the creation of Champagne wine’s character. The chemicals released by autolysis interact with the wine, importing what has been described as flavour, complexity and textural finesse.

77 In addition to this process, a small and slow amount of oxidation is allowed to occur. As the stopper does not give a seal that is perfectly air tight, minute amounts of oxygen are able to enter the bottle permitting some oxidation. Further, a small amount of CO2 also escapes.

78 Together, it is said that the two processes of autolysis and slow oxidation beneficially and slowly transform a young wine into a mature wine.

Step 6 — Riddling (remuage)

79 Towards the end of the resting period, the bottles are rotated. This loosens the deposit left by the second fermentation stage and allows it to collect in the neck of the bottle near the stopper. But for that to occur the bottles need to be progressively tilted neck down, driving the sediment into the neck by gravity. Once riddling has been completed, the bottles are ready for disgorgement.

Step 7 — Disgorgement and dosage

80 After riddling, one is left with sediment that has collected in the necks of the bottles which requires removal (disgorgement).

81 The neck of each bottle is plunged into a refrigerating solution at –27°C. This causes a frozen plug to form at the neck containing, inter alia, the sediment. The cap is quickly removed, and the frozen plug is expelled (under the internal pressure built up in the bottle). The process takes place quickly to minimise loss of wine and loss of pressure.

82 Dosage then occurs. A small quantity of liqueur is added (liqueur d’expédition or liqueur de dosage). This is a mixture of cane sugar and wine, either the same wine as in the bottle or a reserve wine. Dosage makes up the lost volume from disgorgement, but it also has another function. The quantity of sugar added determines the type of wine depending upon the position along the desired spectrum from Extra Brut (0 to 6 grams of sugar/litre) to Doux (more than 50 grams of sugar/litre).

Step 8 — Final corking

83 After dosage, the bottle is immediately (and finally) corked. The cork is squeezed into the neck of the bottle and covered with a protective metal cap (capsule), which is then held in place with a wire cage (muselet). The bottle is then shaken vigorously so that the dosage liqueur marries with the wine. Labelling then occurs, including wrapping the cork and muselet with foil down to the neck-band.

(d) Sparkling wine (non-Champagne)

84 It is appropriate to make some brief observations about sparkling wine.

85 First, by definition, it is not produced in the Champagne region. Accordingly, the grapes produced will not have the characteristics produced by the influence of factors that flow from what the French have termed the terroir, being the identity and character of a particular place in terms of soil, topography and climate. The concept of terroir can be looked at in a macro sense (region) or a micro sense (differences between vineyards).

86 Second, sparkling wines may not be produced from Champagne’s three grape varieties. Rather, the grape varieties used may be high yield and lower flavoured (apparently) varieties such as Chenin blanc, Colombard, Trebbiano, Semillon and the like. Moreover, even if Champagne variety grapes are used, differences will still flow because of differences in terroir, differences in growing and ripening techniques and different harvesting techniques.

87 Third, as I have said, the art of assemblage (blending of base wines) in the Champagne region, given its sheer size, diversity and history, permits of much greater scope and display of expertise, if not artistry, than in smaller, less diverse and newer regions.

88 Fourth, many sparkling wines are produced where the second stage fermentation does not occur within a bottle, let alone the same bottle that is ultimately sold as sparkling wine.

89 Fifth, even putting all these differences to one side, in terms of any one or more of the production steps 1 to 8 described earlier (assuming that they have been used to produce the sparkling wine):

(a) different time periods may be used;

(b) different yeasts and other additives may be used;

(c) different types of equipment may be used;

(d) there may be different levels of skill and experience of the personnel involved;

(e) different quality controls may be used.

90 One can only confidently say about sparkling wine that it is wine made from grapes identified on the label with the stipulated alcoholic content, which wine contains dissolved carbonic gas kept bottled under pressure. No other method or quality indicia is necessarily indicated by the expression “sparkling wine”, whatever the labelling superlatives or use of French like terms, get up or other accoutrements. No party or evidence suggested otherwise. That is, of course, to say nothing about the taste or quality of a particular sparkling wine and whether such taste or quality is comparable to Champagne wine.

APPELLATIONS OF ORIGIN

91 In addition to being a region in France, the name Champagne is also a French controlled appellation of origin (AOC) relating to wines produced within a defined part of the Champagne region and in accordance with strict controls imposed under French law. Prior to the creation of AOCs, the name Champagne was protected as an appellation of origin (AO).

92 The concept of AOs has a long history in France. Geographical names have long been used in France to designate (among other products) wines which have particular characteristics and qualities. The particular characteristics and qualities of such wines reflect both the selection of areas which were suitable for growing particular grape varieties and the development of local viticulture, harvesting and wine-making practices, which have been adhered to in those areas by long standing custom.

93 The concept of an AO was first enacted into French law in the 1905 general trade descriptions law (as amended by a 1908 law). The current definition of an AO under French law is:

An appellation of origin is the name of a country, a region or a locality which is used to designate a product which originates there and the qualities or characteristics of which are derived from its geographical environment, including factors both natural and human.

94 This definition dates back to 1966, although it now forms part of the French Consumer Code, an overarching French law that brings together various consumer protection provisions.

95 Consistently with the use of geographical names, an AO is more than a mere indication of source. It incorporates the notion of the interaction between natural factors (for example, micro-climate and soil formation) and human factors (for example, wine-making techniques).

96 In 1935, AOCs were created under French law as a new category of AOs. The AOC for the name Champagne was created in 1936.

97 The requirements associated with the use of AOCs are more rigorous than the requirements associated with the use of AOs. In order to lawfully bear an AOC, the wine must not only originate from the delimited region, but must comply with detailed regulations (including limitations as to grape varieties, viticulture and wine-making).

98 The terms AO and AOC (and some of the concepts which they represent) are not part of Australian law. However, Part VIB of the AGWA Act contains a regime for the protection of “geographical indications” for wine. In s 4(1) of the AGWA Act, the term “geographical indication” is defined as “an indication that identifies the goods as originating in a country, or in a region or locality in that country, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the goods is essentially attributable to their geographic origin”.

99 The name Champagne is, and has since 1994 been, a registered geographical indication under the AGWA Act and its earlier forms.

the name Champagne in Australia

100 As I have said, the term Champagne wines describes wines produced in the Champagne region of France, made in accordance with French laws and entitled under those laws to bear the name Champagne. The wines Arras, Digby, Jansz, Nyetimber, Rococo, Blason de Bourgogne, Elstree, Gusbourne and Asti Spumante are only sparkling wines.

101 In Australia in and prior to September 2011 the name Champagne was used by a number of Australian producers to label and market their sparkling wines. Such a usage was well publicised and is supported or can be inferred from the following examples:

(a) In “Champagne – how and when to serve it” in Bride, Autumn 1983, the author stated:

“The Argyle Function Centre, which caters for weddings in Sydney, says the difference between French champagne and the Australian product is about $13 a bottle, and there are eight glasses in every bottle”

(b) Diane Holuigue stated in The Epicurean November–December 1984 (referring to the Vin de Champagne awards):

“Supported by all the importers of French champagne (interestingly, this is one of the few countries in the world where we writers must add the word “French” since to the rest of the world champagne is French by definition)…”

(c) The use of the term “French champagne” by James Halliday in The National Times (December 1980) and National Times Financial Weekly (31 May 1984);

(d) The use of the term “French champagne” by Mary Machen in The Tasmanian Mail, 3 June 1985:

“When Holly hosts a dinner at home, guests can be assured that the accompanying wine will be French Champagne – and only the best of vintages”.

(e) In The Epicurean September–October 1984 the author stated:

“Australians seem always to have loved champagne, but our current love relationship with it is surely unprecedented. We’ll probably be buying it at the rate of a million bottles a year by next year. And that’s the real thing … the French stuff!”

(f) In the Canberra Times, 3 May 2000, Susan Parsons wrote:

“The centre in Sydney is dedicated to furthering knowledge and understanding of genuine champagne”.

(g) In “The Australian Wine Educator” – Spring–Summer 2000–01, the role of the CIVC to protect the good name and reputation of the wines of the region was explained by reference to the following history:

“During the 18th and 19th Centuries the fame of the wines of Champagne spread through France and England, then Switzerland and Germany, and eventually to Australia, the United States and other parts of the world. As the reputation of the wines increased, the name itself began to be appropriated by wine producers in other regions of France and other parts of the world to describe their own sparkling wines”.

(h) In the April 2002 article by Kate McIntyre entitled “Champagne comes from France”, the author began:

“Enough. I’ve had it. I’m sick of being the Champagne Nazi. When I go to a restaurant and ask for a glass of Champagne, why do people insist on offering me Australian sparkling wine as an alternative? Sure it can be very good – terrific, in fact, but that’s not what I asked for. I asked for Champagne, from Champagne. In France”.

(i) In “With Bubbly Breakfasts; Stay in Touch This Week” in the Sydney Morning Herald on 31 August 2009, Sean Nicholls and Emily Dunn stated:

“The event, organised by the Champagne Bureau, a Sydney outfit that promotes the real French stuff to the bubbly‐loving Australian public …”

102 In Australia, the general use of the name Champagne as it had been applied to sparkling wines had ceased by September 2011 as part of the phase out in Australia of a range of European geographical indications.

103 The phase out was the result of bilateral negotiations between Australia and the European Union in relation to trade in wine. It was initiated by the Agreement between Australia and the European Community on Trade in Wine (1994 Agreement), which entered into force on 1 March 1994. The 1994 Agreement was given statutory force under Australian law by the Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation Amendment Act 1993 (Cth) which amended the Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation Act 1980 (Cth). Under Title II, Articles 6(1), 7 and Annex II of the 1994 Agreement, Australia agreed to protect a range of European geographical indications, including Champagne. However, under Title II, Articles 8(1) and 9 of the 1994 Agreement, the phase out of the use of the name Champagne in Australia as a description for Australian wine was subject to a transitional period to be agreed.

104 Such a phase out was finalised by a further Agreement between Australia and the European Community on Trade in Wine, which entered into force on 1 September 2010 (the 2010 Agreement); the 1994 Agreement was terminated on 1 September 2010. Under Title II, Articles 12(1), 13 and Annex II of the 2010 Agreement, Australia again agreed to protect a range of European geographical indications, including Champagne. Under Title II, Article 15 of the 2010 Agreement, the protection of the Champagne geographical indication was subject to the proviso that it would not prevent the use in Australia of the name Champagne in the description and presentation of an Australian wine prior to 1 September 2011. Accordingly, on and after 1 September 2011, the name Champagne could not be used for Australian wines, including sparkling wines.

105 The prohibition on the use of the name Champagne in the description and presentation of wines which were not Champagne wines under Australian law is now set out in Part VIB of the AGWA Act.

106 It is accepted by the parties that the name Champagne means, and has for many years meant, to at least some members of the public in Australia:

(a) the Champagne region of France; and

(b) wines produced from the Champagne region using the grape varieties and methods of cultivation and vinification, and complying with the standards, composition and specifications required for Champagne wines.

107 But Ms Powell has gone further. She contended that the meaning referred to in [106(b)] is “overwhelmingly” the meaning that most members of the public would attach to Champagne. But in cross-examination Ms Powell gave evidence which supports the proposition that the name Champagne is used by some Australians to refer to any sparkling wine. Ms Powell said:

Some people do know that champagne can only come from Champagne, and they will only drink champagne, and some people — especially in Australia — call everything champagne.

108 At a later part of her cross-examination, Ms Powell confirmed her earlier evidence:

Well, what you said yesterday is — I will read it to you?---Thank you.

Page 163, line 15:

Some people do know that champagne can only come from Champagne, and they will only drink champagne, and some people — especially in Australia — call everything champagne.

Do you recall giving that evidence?---Well, you’ve just read it to me; it must be right.

Yes, well, that is - - -?---Yes.

- - - your understanding of the position, isn’t it?---Unfortunately, yes.

109 Other aspects of Ms Powell’s evidence demonstrate this broader use of the name Champagne. Ms Powell was cross-examined about an early brochure used in connection with her WineWorks International business which included a section titled “Champagne + Food Pairing”. Under that heading, the following appeared:

Strawberries

This is a classic for romantic occasions, but it only works with very sweet sparklers! Try this with Asti Spumanti from Italy, or Pommery Pop.

Ms Powell sought to downplay the reference to an Italian wine in this document as a “regrettable oversight”. Although she did not write this section of the brochure, nevertheless this is an indication of how the name Champagne has been used and understood by some people in Australia, and Ms Powell’s knowledge of that fact.

110 Further, as I have said, the name Champagne was used by a considerable number of producers on labels of, and in marketing materials for, Australian wines. Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, examples of commercially available Australian wines labelled and described as Champagne were: KILLAWARRA, MINCHINBURY, SEAVIEW, SEPPELT GREAT WESTERN and WOLF BLASS. For example, the 1999 publication titled The Professional Australian Wine Guide contained an image of a MINCHINBURY CHAMPAGNE label and stated: “Generic styles. A style of wine which may be a single variety or a blend of grape varieties, taking its name from an existing European region or style of wine. Examples include Champagne wine (taken from the French region) and Port (taken from the Portuguese fortified wine). These generic styles are becoming increasingly obsolete”.

111 Ms Powell also referred to the definition of “champagne” in the 6th ed of the Macquarie Dictionary (published in 2013) which she asserted captured the position in Australia being:

1. a sparkling white wine produced in the wine region of Champagne, France.

2. (in unofficial use) a similar wine produced elsewhere.

3. the non‐sparkling (still) dry white table wine produced in the region of Champagne.

4. a very pale yellow or cream colour.

–adjective

5. having the colour of champagne.

6. of or relating to any event or activity made special by the serving of champagne: champagne flight; champagne breakfast.

7. up-market; luxury: champagne holiday.

Usage: A number of wine names refer to districts (e.g. Champagne in France, Chianti in Italy) but have come to be used for similar wines produced outside these districts. In deference to the original districts, Australian winemakers have dropped these names in favour of varietal names, or invented names such as fumé blanc, particularly after the Australian–European Community Agreement on Trade in Wine (2008). Nevertheless, a word like champagne is so widely known in English that it is likely to persist in common usage, whatever appears on bottles.

112 For completeness, I should note that despite the historical informal use of the name Champagne in Australia in connection with Australian wines, Australia has long been a significant market for Champagne wines properly so called. Between 2001 and 2013, each year an average of more than 3,000,000 bottles of Champagne wines were exported to Australia. During that period, Australia has been one of the top ten markets for Champagne wines internationally.

113 In summary, the evidence well supports the following inferences:

(a) First, prior to September 2011, in the context of descriptions for wines, the name Champagne was applied in Australia to Champagne wines properly so called and sparkling wines.

(b) Second, and consistently with the first proposition, a significant proportion of Australian actual and potential consumers of either or both of Champagne wines and sparkling wines prior to September 2011 would have been likely to understand or believe that the name Champagne could be applied to either.

(c) Third, a significant proportion of Australian actual and potential consumers of either or both of Champagne wines and sparkling wines prior to September 2011 would have been likely to understand the correct attribution and reference applying to the name Champagne.

(d) Fourth, prior to September 2011, there would have been a significant proportion of Australian actual and potential consumers who would have been unclear one way or the other. The proportion of consumers in this category in all likelihood would have been greater than in each of the other two categories.

(e) Fifth, after September 2011, the percentages of consumers in each of classes (b) and (d) would in all likelihood have diminished with the percentage of consumers in class (c) correspondingly increasing. This would in all likelihood have been caused, inter alia, by the phase out described earlier and also partly as a result of the CIVC’s activities described below. But no quantitative measure or precision to these propositions is available or could practicably be calculated.

CIVC’s activities in australia

114 The CIVC has for several decades done a significant amount of work in Australia to publicise and promote the name Champagne in connection with Champagne wines and the Champagne AOC. Further, in light of the phase out of the use of the name Champagne in relation to sparkling wines, a significant focus of the work done by the CIVC in Australia has been the rehabilitation of that name to ensure that it was applied only to the Champagne sector. As I have said, the present case is not a passing off case. But the activity of the CIVC in Australia, to the extent that it has raised awareness of Champagne wines and how the name Champagne should be understood by consumers in Australia, is not irrelevant contextual material as to how consumers might now understand the name Champagne.

115 The following is an example of such work.

116 First, since 2000, the CIVC has taken action to prevent the misuse of the name Champagne in Australia.

117 Second, the CIVC has also established a Champagne Bureau in Australia to assist with its work to develop the reputation of, and protect, the name Champagne. The Australian Champagne Bureau (previously known as the Champagne Information Centre) (the Bureau) was established in 1971. The Bureau is, and has always been, funded by the CIVC. The Bureau has extensively publicised and promoted the name Champagne in Australia in connection with Champagne wines and the Champagne AOC by promotional activities including tastings, dinners, training courses and seminars and by the distribution of promotional and educational materials (such as tasting guides).

118 Third, one of the main promotional activities undertaken by the Bureau is the Vin de Champagne Award which was first held in 1974. The Award is held every two years and receives a significant amount of publicity in the general media. It has the following characteristics:

(a) It is a prestigious award;

(b) Originally it was open only to wine professionals, but a non‐professional category and student category was later introduced;

(c) Entrants must answer a series of technical questions in relation to Champagne wines, the Champagne AOC and the Champagne region of France;

(d) A number of previous winners have gone on to have careers in the wine industry both in Australia and internationally.

119 Fourth, the Bureau has conducted dozens of promotional and educational events in Australia, including tastings, dinners, training courses and seminars. For example:

(a) 25 September 2008 – Champagne master class conducted by Daniel Lorson at Regency Hotel School for lecturing staff and international students in Cordon Bleu and International Hotel School Classes;

(b) 28 September 2008 – Champagne dinner in Pemberton with local winemakers;

(c) 12 December 2008 – Champagne tasting for the Oenophiles wine group;

(d) 22 August 2011 – Champagne Bureau 2011 Trade Tasting: “Wine & food media, retail trade, sommeliers, wine educators, food and beverage managers of major hotels and fine wine buyers attended throughout the day”;

(e) 21 May 2011 – Friends of Champagne tasting – WA friends of Champagne;

(f) 2011: “To help sort the Moet from the Mumm, the Champagne Bureau runs master classes every two years”;

(g) 2012 Vogue Living Champagne Dinners: “These prestigious dinners are a highlight on our annual calendar and offer the opportunity for lovers of Champagne to enjoy their favourite style of wine alongside fine produce, prepared by some of Australia’s top chefs”;

(h) 2013 National Master Class Series: “To provide a forum for Champagne enthusiasts, trade and media across Australia to taste and discuss a selection of vintage, non-vintage and other styles of Champagne wines”.

120 Fifth, the Bureau’s website was set up in 2006 as a promotional tool for Champagne wines; there is no evidence as to the amount of traffic to that website.

121 Sixth, the Bureau’s Facebook page has been active since 2010. The posts primarily concern the above promotional activities, namely, the Vin de Champagne Award, the Vogue Living Dinners and Champagne Master Classes. But there is no evidence as to the amount of traffic to the Bureau’s Facebook page from 2010 to 2014. However, 674 “likes” of the page are recorded as at 20 October 2014, although there is no breakdown. It is not clear whether the people who have “liked” the page are the Bureau’s employees, entrants to the Vin de Champagne Awards, wine & food media, retail trade, sommeliers, wine educators, lovers of Champagne or ordinary Australian consumers.

122 Seventh, the Bureau’s Instagram page has been active since 2014. The posts primarily replicate images from the Bureau’s Facebook page. But no evidence has been supplied about the amount of traffic to the Bureau’s Instagram page for 2014. However, 249 “followers” of the page were recorded as at 21 October 2014, although there is no breakdown of these followers.

123 In summary, the CIVC’s activities through the Bureau in Australia are likely to have had some educational effect in Australia concerning the proper use of the name Champagne as it applies to wines. I have taken this into account in drawing the inferences and conclusions set out in [113] above and [217] to [229] below.

Ms Powell’s business

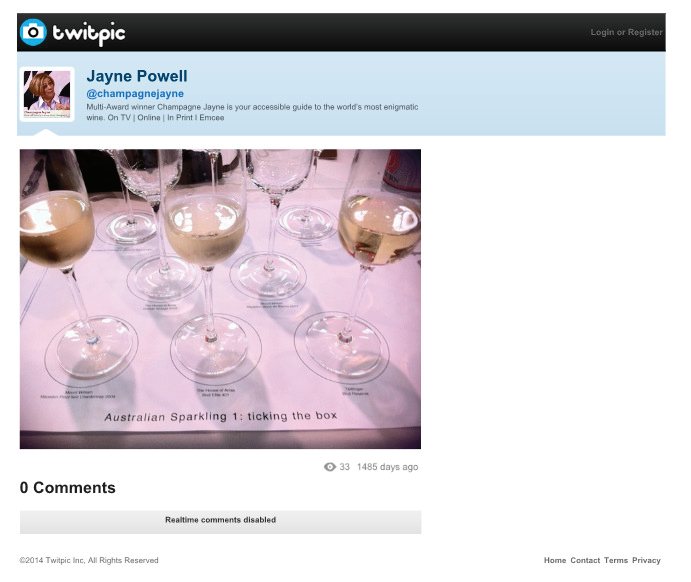

124 Ms Powell’s Champagne Jayne business is directed to the promotion of herself and Champagne wines. But about 10% of her activities in the Champagne Jayne business relate to sparkling wines. In using the term “business”, I am referring to her activities in creating her persona “Champagne Jayne” and then under that label and persona providing services such as entertainer services, public speaking services, event management services and master of ceremony services for a fee. Such services also include from time to time reference to and use of Champagne wines and sparkling wines. Indeed, from time to time she has promoted sparkling wines such as Arras, although I accept that she has not received a separate fee from a wine producer to promote its products. She may, however, have received free product from a producer to use in providing her services and may have had some of her expenses paid for.

125 In 2009, Ms Powell:

(a) registered the business name CHAMPAGNE JAYNE (Business Name);

(b) established the Website;

(c) established the Twitter account @champagnejayne (Twitter Account); and

(d) established the CHAMPAGNEJAYNE Facebook Page (Facebook Page).

126 In 2010, Ms Powell established the CHAMPAGNEJAYNETV YouTube website (YouTube Website).

127 In 2013, Ms Powell established:

(a) the champagnejayne Instagram account (Instagram Account); and

(b) the Champagne Jayne Vine account (Vine Account).

128 On 31 January 2012, Ms Powell applied to register the words CHAMPAGNE JAYNE as a trade mark in respect of “Entertainer services; public speaking services; author services being the writing of texts (other than publicity texts); event management services (organisation of educational, entertainment, sporting or cultural events); master of ceremonies services”. The CIVC has opposed this trade mark application. The opposition has not yet been set down for hearing before the Registrar of Trade Marks.

129 Generally, Ms Powell has used the Business Name, the Website (including blogging thereon), the Twitter Account, the Facebook Page, the YouTube Website, the Instagram Account and the Vine Account to operate the Champagne Jayne business. Ms Powell was equivocal as to whether she used Instagram and Vine for her business but I have little doubt that her use of such tools also facilitated her business.

130 Before proceeding further, it is appropriate to make some general observations concerning social media.

SOCIAL MEDIA

131 “Social media” is the contemporary phrase used to describe modern digital methods of communication having extensive reach and popularity; the forms of social media and the features thereof are continuously evolving. It is appropriate to give a general description of Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and Vine before elaborating on Ms Powell’s use of such tools to promote herself and her services.

(a) Twitter

132 Twitter is an online network for individuals and businesses to instantaneously post short written messages, photos, videos or links on their personalised profile pages. Individual Twitter pages are identified by a username preceded by the “@” symbol and contain a short “bio” description about the author. Posts are called “Tweets” and are limited to no more than 140 characters. A “hashtag” may be included in a Tweet, being the symbol “#” followed by a keyword or phrase, to assign a particular topic to that Tweet and to ensure that the Tweet appears in that topic’s Twitter feed (that is, Twitter page). Users can search for a particular “hashtag” or “@username” on the Twitter site and thereby see all Tweets containing that hashtag or mentioning that username. Tweets are visible to the public by default but can be restricted to certain “followers”.

133 Followers are those who have signed up to Twitter and who have chosen to subscribe to other users’ Twitter profiles so that the other users’ Tweets are immediately displayed and continuously updated in real-time on the follower’s homepage. The homepage, which is in substance a stream of information, is also known as a “timeline”. Users can choose to receive “push notifications”, i.e. messages to their mobile device, each time there is any activity on their timelines. Each Twitter profile contains a visible list of the followers of that page. Followers can reply to or comment on a Tweet, which begins a cascading conversation of Tweets. But a Tweet reply that begins with “@username” of the person being replied to is only seen on the sender’s public profile and the home timeline of the recipient if he follows the sender and those who follow both the sender and recipient. A Tweet that contains “@username” anywhere in it will be displayed on the sender’s profile and the home timeline of the recipient if he follows the sender and any followers of the sender. Followers can also share other users’ Tweets with their own followers on their profiles with or without their own comments. The act of sharing another’s Tweet, that is, forwarding it on, is known as “retweeting”. Followers can also “favourite” a Tweet if they endorse or approve of it which is recorded by a star symbol below the Tweet and is listed in the “favourites” tab on the follower’s profile. A Tweet can be deleted from a Twitter page by its author which in turn deletes any retweets of that Tweet. But deleting a Tweet does not erase retweets with additional comments, copies of the Tweet that are not retweets and any external copy of the Tweet not on the Twitter website.

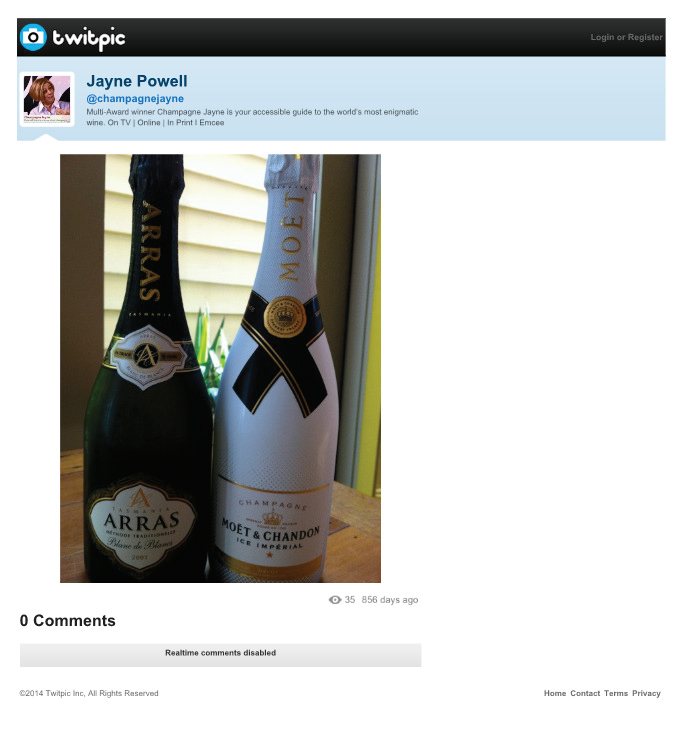

134 Ms Powell created her Champagne Jayne Twitter account under the name “Jayne Powell: @champagnejayne” in March 2009. Her account profile contains the description “Multi-Award winner Champagne Jayne is your accessible guide to the world’s most enigmatic wine”. It lists her location as “UK, France, Australia”. As at 2 November 2014, Ms Powell had Tweeted approximately 21,000 times, including links to around 2,500 images and videos. Ms Powell frequently Tweets about Champagne wines and publishes links to her articles, videos hosted on her blog (www.champagnejayne.com), highlights of her visits to the Champagne region, her Champagne experiences at various restaurants and events around the world as well as other personal social matters unrelated to wine. As at 9 December 2014 there were around 3,420 followers of the Champagne Jayne Twitter account.

(b) Facebook

135 Facebook is an online social networking tool that allows users to create either personal profiles or business pages in order to connect and communicate with other people. Users can post messages (short messages are often described as “status updates”), photos, videos or links on their Facebook pages that are generally accessible, and can be interacted with, by the public subject to any privacy settings that the page creator has put in place. If privacy settings have been activated on a Facebook profile, only certain people approved by the profile creator are able to view or interact with the posts on that profile. Facebook users can leave comments on posts or “like” posts by clicking a “thumbs up” icon beneath the post. The comment or “like” is visible to visitors to the page on which the post appears and the page of the person leaving the comment or clicking “like”. Posts can also be shared among Facebook users. An individual can connect with another person on Facebook via a “friend request” which, if accepted, adds that individual to the other’s personal profile, allowing access to posts that appear on that profile depending on privacy settings. When a user “likes” a particular Facebook page by clicking the “like” icon, that conveys a positive opinion of the page and adds the page to the list of “likes” that appears on the user’s profile. “Liking”, or subscribing to, a page also results in posts from that page being automatically displayed in the “news feed” of the person who liked the page, which is a continuously updating list of posts on a user’s homepage from that person’s “friends” and pages that he is following. Only the total number of “likes” that a page has received can be seen on that page; the identity of those who have liked the page may be discernible by the author of the page. A notification is also received by a user whenever there is activity on their Facebook profile or page, for example, a comment is made on their post or someone chooses to “like” their page.

136 Ms Powell started her Champagne Jayne Facebook page in November 2009. It contains the description “[d]edicated to increasing your understanding and enjoyment of champagne”. As at 2 November 2014, there were approximately 500 Facebook users who had “liked” the Champagne Jayne Facebook page and who accordingly received on their news feed any posts uploaded to the Champagne Jayne page. Ms Powell uses the Champagne Jayne page to publish blogs, images, articles and news about Champagne wines and occasionally sparkling wine. These are viewable by the public.

(c) YouTube

137 YouTube is a website that allows visitors to upload, watch and share videos. Generally videos are viewable by the public but privacy settings can be put in place by the content creator. Videos can be found by either searching the entire website or accessing a specific “channel” which is a YouTube accountholder’s page that features videos that they have created and contains a short description of the creator. Users of YouTube can subscribe to particular channels for free which automatically updates that channel’s video content onto the user’s subscription feed. The number of subscribers to a channel appears on that channel’s homepage. Videos and channels that are recommended viewing by YouTube also appear on a user’s homepage. Audience members can engage with each other and the video’s creator on YouTube by leaving public comments (and replies thereto) on videos, clicking the “like” or “dislike” icon beneath videos and sharing videos via other social media portals. Video owners have the right to remove comments that have been placed on their videos. The total number of times each video has been viewed also appears next to the video. A similar website, Vimeo, is another vehicle for online video sharing.

138 In January 2010, Ms Powell created a YouTube channel under the name “ChampagneJayneTV” on which she posts educational videos about Champagne wine appreciation, video blogs and highlights from Champagne events. As at 2 November 2014, there were 72 subscribers to the Champagne Jayne channel and there had been more than 25,000 views of the videos posted thereon. Ms Powell has also published similar material on her Vimeo channel.

(d) Instagram

139 Instagram is an online social network on which photographs and videos can be uploaded to an account page via the Instagram mobile app, using a range of filter effects and accompanied by captions, and shared by the creator via multiple other platforms including Twitter and Facebook. Hashtags can be incorporated within a post in order to make that post easily searchable and visible on the Instagram page for that particular hashtag. Instagram profiles include a biography of the creator (the “Instagrammer”) and are viewable either by the public or, if the account is set to private, by the account followers only. Users can choose to “follow” or subscribe to particular Instagram accounts. When this occurs, the photos or videos posted by the person followed will automatically appear in the follower’s homepage feed (unless the page followed has been made private in which case the creator must first approve the “follower request”). The number of followers of an Instagram page is displayed at the top of that page. Anyone can “like” or comment on a public post, which then becomes visible to other visitors to the profile page on which the post appears.

140 In March 2013, Ms Powell created an Instagram account under the username “champagnejayne”. As at 2 November 2014, there were approximately 130 followers of the Champagne Jayne Instagram account. Ms Powell said that by August 2014 she had posted nearly 1000 images, the majority of which referred to Champagne wines and approximately 20 of which concerned sparkling wine.

(e) Vine

141 Vine is a website on which users can watch, create and share “looping” (that is, constantly repeating) video clips of up to six seconds in length. The videos are recorded or uploaded using the Vine phone device app. Captions, including hashtags, can be posted with the video to ensure broader exposure. Users can create their own public or private profile page, follow other users (known as “favouriting”) so that the other users’ videos appear in their home feed, “like” and comment on videos posted, and share videos (known as a “revine”) to their own followers or other social networks. Each video will also display any comments, “likes”, the number of “revines” and the number of times the video has been viewed. Channels can also be created in a manner similar to that available on YouTube.

142 Ms Powell created a Vine account in January 2013 under the name Champagne Jayne. As at 2 November 2014, there were approximately 86 followers of the Champagne Jayne Vine. Between January 2013 and March 2014, Ms Powell posted approximately 87 videos to her Vine account.

How has Ms Powell promoted herself?

143 In order to place Ms Powell’s conduct in context, it is appropriate to set out further details as to how Ms Powell has presented the Champagne Jayne business to the public. Extracts from Ms Powell’s email sign-off, the Website, the Twitter Account, the Facebook Page, the YouTube Website, the Instagram Account and the Vine Account show how Ms Powell has presented the Champagne Jayne business. It is well apparent that Ms Powell and the Champagne Jayne business have been consistently introduced under and by reference to the name Champagne. Generally, Ms Powell and the Champagne Jayne business have been promoted in a way that emphasises “Frenchness” and more generally all of the advantageous accoutrements that are associated with the name Champagne.

144 The CIVC has contended that Ms Powell has intentionally adopted trade indicia which call upon and use the goodwill associated with the name Champagne. The CIVC has also contended that Ms Powell has in an informal sense traded off the favourable reputation associated with the name Champagne. I agree. But it should be stressed, as I have said at the outset, that this is not a passing off case. The principal question is whether her conduct has misled or deceived or been likely to have misled or deceived Australian consumers or a class thereof. One can appreciate the perspective of the CIVC and what it perceives to be behaviour on the part of Ms Powell arrogating to herself some of the benefits of the goodwill created by a highly professional, dedicated and skilled industry of the Champagne region. That industry has produced a product that consumers have enjoyed the world over from a region that has shown great resilience not only in terms of growing conditions but also under waves of human tragedy associated with its geographical location. But none of that is the real issue. The important question for present purposes is how Ms Powell has conducted and represented herself to Australian consumers or a class thereof and used the persona of her alter ego.

145 The forms of social media used by Ms Powell have been presented to the public as emanating from Champagne Jayne. Further, the various introductions to Ms Powell’s Facebook Page, Twitter Account and Instagram Account all give prominence to and emphasise Champagne. Persons who access such pages in all likelihood would expect content relating to Champagne. Moreover, for those persons who have greater familiarity with Ms Powell’s activities and services, those expectations would be stronger and more reinforced as compared with those who had no such familiarity. It should be noted that Ms Powell’s social media postings could be viewed on the internet by any member of the Australian public.

Email signature

146 Ms Powell has used the following email signature:

Jayne Powell

Editor, www.champagnejayne.com

e: cj@champagnejayne.com

w: www.champagnejayne.com

t: www.twitter.com/champagnejayne

s: Champagne Jayne Powell

Harpers 2012 Champagne Educator of the Year

Gourmand 2011 Author Best French Wine Book (Aus)

Dame Chevalier de L’Ordre des Coteaux de Champagne

Website

147 Ms Powell has presented herself to the public in the following way on the Website:

Broadcaster/Presenter/Educator/Entertainer/MC

Your Chance To Book One of Champagne’s Greatest Independent Ambassadors

Known throughout the global wine industry simply as “Champagne Jayne”, award winning champagne journalist, educator, market builder and Champagne Dame Jayne Powell is a respected international media commentator, independent reviewer and expert in champagne.

…

About the author

I fell in love with Champagne on my first student visit to France aged 15 after watching way too many Bond movies. I’m passionate about showing people just how much fun they can have connecting with Champagne and ensuring this iconic symbol of luxury is accessible to all. I don’t promote houses or brands. I promote knowledge and enjoyment which enables people to uncork more business and pleasure in life. I hope to share a scintillating sensory journey with you soon.

Cheers!

Champagne Jayne

148 The bold text “Your Chance To Book One of Champagne’s Greatest Independent Ambassadors” on the Website has been replaced (at a time unknown) with the text “Multi-Award Winner Champagne Jayne enriches your champagne experience”.

149 The embedded video commences with Ms Powell speaking in French (saying “Hello and welcome to the website champagnejayne.com.”). In the video, Ms Powell speaks exclusively about Champagne wines (there is no mention of sparkling wines) and the video contains introductions to Ms Powell by members of well-known Champagne families (Taittinger and Krug). During the video, Ms Powell refers to her book which relates to Champagne wines. Ms Powell also refers to herself as “… the proud owner of an Ordre des Coteaux de Champagne medal – so I’m officially a Champagne Dame”.

150 In other parts of the Website, Ms Powell has presented herself as:

(a) “Australia’s Champagne Day Ambassador”;

(b) “… a global ambassador for Champagne …”;

(c) “… renowned independent champagne evangelist Dame Chevalier Jayne Powell (aka Champagne Jayne) …”;

(d) “Dame Chevalier Jayne Powell”;

(e) “… real life Champagne Dame …”; and

(f) “… Champagne Dame (Dame Chevalier) Jayne Powell …”.

On at least one occasion, Ms Powell has also published content on the Website which incorporates the logo of the CIVC, which suggests to readers that Ms Powell has an association with the CIVC.

151 Ms Powell has also permitted herself to be described in similar terms in publications by third parties. For example, the profile of Ms Powell published on the website of Saxton (an agency for public speakers that represents Ms Powell) describes her in the following terms:

… acknowledged “go to” expert in champagne, Jayne’s palette remains a “free agent”, unrestricted by any brand allegiance. A fluent speaker in French, Jayne is also considered a friend to family members of many champagne houses in France and a great ambassador for champagne internationally.

Twitter Account

152 The Twitter Account has the following brief introduction (which is able to be viewed at twitter.com/champagnejayne):

Facebook Page

153 The Facebook Page has the following brief introduction (which is able to be viewed at https://www.facebook.com/pages/CHAMPAGNEJAYNE/170537879380):

Dedicated to increasing your understanding and enjoyment of champagne - find out more at www.champagnejayne.com or follow @champagnejayne

Description

…

BY CHAMPAGNE JAYNE

- 2012 Champagne Educator of the Year (Harpers)

- 2011 Author Best French Wine Book (Gourmand)

- Honoured as a real ‘Champagne Dame’ (Dame Chevalier de L’Ordre des Coteaux de Champagne)

YouTube Website

154 The homepage of the YouTube Website also features the video referred to in [147] to [149] alongside the following text (which can be viewed at “www.youtube.com / user / CHAMPAGNEJAYNETV”):

Who is Champagne Jayne

728 views 1 year ago