FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams Pty Ltd

[2015] FCA 1016

Table of Corrections | |

24 September 2015 | The terms of Annexures 2 and 3 were amended. |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | RL ADAMS PTY LTD (ACN 093 556 613) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. A declaration that the Respondent, from 31 December 2013 to 6 October 2014:

(a) by supplying for sale or causing to be supplied for sale eggs produced by laying hens and packaged in cartons sold under the brand names Mountain Range Eggs and Drakes Free Range Eggs, depicted in Annexure 1 (Free Range Egg Cartons); and

(b) by advertising and promoting the eggs sold in the Free Range Egg Cartons by publishing, or causing to be published, the following website: www.fresheggs.com.au (Mountain Range Eggs Website),

in each instance represented to consumers that in the period from 31 December 2013 to 6 October 2014, the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced:

(c) by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day (where an ordinary day is every day other than a day when the weather conditions on the open range endangered the safety or health of the laying hens, predators were present or the laying hens were being medicated); and

(d) by laying hens most of which moved about freely on an open range on most days,

(Free Range Representation),

when, in fact, the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced by laying hens all of which were unable to, and did not, move about freely on an open range in the period from 31 December 2013 to 6 October 2014, and the Respondent, thereby, in trade or commerce:

(e) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); and

(f) in connection with the supply or possible supply of eggs, and the promotion of the supply of the eggs, made misleading representations that the eggs were of a particular quality, or had a particular history in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law; and

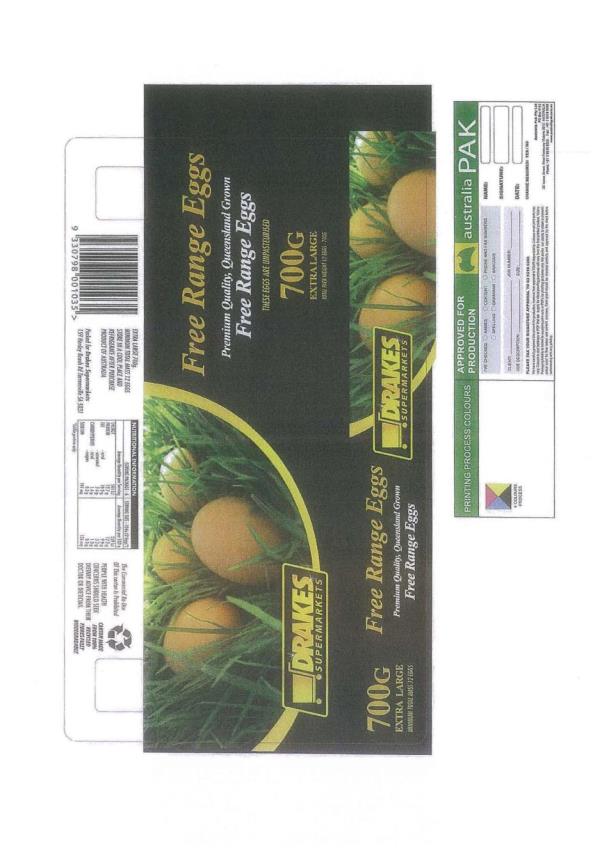

(g) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of the eggs, in contravention of s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law.

Pecuniary penalty

2. An order that the Respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law in the sum of $250,000.

Publication orders

3. Orders that the Respondent, at its own expense:

(a) within 14 days of the date of this order, and for a period of 90 days, publish on the Mountain Range Eggs homepage, accessible at the URL www.fresheggs.com.au, a notice in the terms and form of Annexure 2 to this Order (Website Notice) and ensure that:

(i) the Website Notice is accessible via a ‘click-through’ icon on the Mountain Range Eggs Website homepage and each of the internal webpages;

(ii) the ‘click-through’ icon contains the words “click here – False and Misleading Conduct by RL Adams – Notice Ordered by the Federal Court of Australia” and be in a text which is:

(A) no less than 15-point in Times New Roman font;

(B) black typeface on a white background;

(C) centred unless otherwise stated;

(D) in bold; and

(E) at the top of each homepage and internal webpage; and

(iii) the Website Notice is displayed as a ‘pop up’ window that occupies the entire webpage.

(b) within 21 days of the date of this order, publish a corrective advertisement, in the form of Annexure 3 to this Order, in each of the major metropolitan newspapers in each State or Territory in which the Respondent supplies or causes to be supplied for sale the Free Range Egg Cartons, and further, ensure that each advertisement is:

(i) at least 15cm by 15cm in size;

(ii) in a text which is Arial font and which is:

(A) for the headline, no less than 14-point and bolded; and

(B) for the remaining text, no less than 10-point, and

(iii) be placed within the first 10 pages of each of the newspapers.

Compliance order

4. An order that the Respondent, at its own expense:

(a) within 3 months of the date of this order, establish an Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program which meets the requirements set out in Annexure 4; and

(b) maintain and administer the Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program for a period of 3 years from the date on which it is established.

Costs

5. An order that the Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of the proceeding fixed in the sum of $25,000.

6. The originating application is otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE 1

ANNEXURE 2

ANNEXURE 3

ANNEXURE 4

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 672 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | RL ADAMS PTY LTD (ACN 093 556 613) Respondent |

JUDGE: | EDELMAN J |

DATE: | 11 september 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This penalty hearing is yet another case concerning false, and misleading or deceptive conduct concerning “free range” animals. Sellers of products such as chicken, duck, or eggs obtain a premium price by representing their products to be derived from animals that live or lived “free range”. The agreed facts in this case reveal that this premium is substantial in the case of chicken eggs. One possible reason why consumers pay a substantial premium may be a belief that the sellers of these products have treated the animals more ethically than would be the case if the animals had not lived with a reasonable freedom to roam. Unfortunately, cases in which “free range” representations are falsely made do not appear to be abating.

2 In a 2010 decision of this Court, the respondents (CI & Co Pty Ltd and Mr Pisano and Ms Pisano) made representations that the eggs that they supplied were “free range” when the eggs had been produced by caged hens. No pecuniary penalty was sought and none was imposed upon the company, but penalties of $30,000 and $20,000 were imposed on Mr and Ms Pisano: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CI & Co Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1511.

3 In 2012, a penalty of $100,000 was imposed by consent and at the suggestion of the parties upon a company (La Ionica) that produced retail posters entitled “Health Farm Poster” that said that its chickens were “free to roam in large open sheds – NO CAGES”. The chickens were raised or grown exclusively in a shed or barn: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 19.

4 Again in 2012, pecuniary penalties were imposed upon an individual, Ms Bruhn, for misdescribing cage eggs as “free range”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bruhn [2012] FCA 959; [2012] ATPR 42-414.

5 In 2013, joint pecuniary penalties of $400,000 were imposed on two of Australia’s largest chicken meat companies who produce chicken products branded “Steggles”. The companies had falsely represented that all Steggles chickens are grain fed and free to roam in large barns: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 5) [2013] FCA 1109; [2013] ATPR 42-450.

6 Again in 2013, a pecuniary penalty of $360,000 was imposed, by consent and at the suggestion of the parties, upon the unfortunately named Luv-a-Duck Pty Ltd including for false or misleading representations that the duck meat products it offered for sale were from ducks that spent at least a substantial amount of their time outdoors: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Luv-A-Duck Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1136; [2013] ATPR 42-455.

7 Yet again in 2013, a pecuniary penalty of $375,000 was imposed upon Pepe’s Ducks Ltd, by consent and at the suggestion of the parties, including for false representations, over a period of 8 years, by statements that the duck meat products that it sold were “Open Range” or “Grown Nature’s Way”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pepe’s Ducks Ltd [2013] FCA 570; [2013] ATPR 42-441.

8 In September 2014, a penalty of $300,000 was imposed, by consent and at the suggestion of the parties, upon Pirovic Enterprises Pty Ltd for misleading or deceptive conduct by advertising “Pirovic Free Range Eggs” and falsely representing over two years that its hens moved around freely. That case involved an enterprise with approximately 1% of the free range egg sales in New South Wales and annual profits of around $380,000 for free range egg sales: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pirovic Enterprises Pty Ltd (No 2) [2014] FCA 1028; [2014] ATPR 42-483.

9 This case is yet another example of an Australian company which has made false “free range” representations. RL Adams is an Australian company which produces and sells chicken eggs from Wingrave Farm in Queensland. It described its eggs as “free range”. From 31 December 2013 until October 2014, RL Adams’ “free range” representations were false and misleading.

10 Under the Australian Consumer Law, the maximum penalty for a single instance of infringing conduct is $1.1 million for a body corporate and $220,000 for a natural person. It was common ground on this application, based on authority of this Court, that the course of conduct committed by RL Adams should be treated as though it were a single contravention. For reasons concerning the totality principle, and in the absence of any submission to the contrary, I have accepted that submission. However, it should not be assumed that a series of related infringements will always be treated as a single contravention. General deterrence is an important consideration in the imposition of pecuniary penalties. Against the pattern of the published decisions described above, it may be that these “free range” cases illustrate that general deterrence is not having sufficient effect.

11 The circumstances of this case involve significant mitigating factors, particularly the near-complete co-operation by RL Adams with the Commission and its admission of responsibility, for the reasons I explain below, I consider that the appropriate orders are declarations, publication orders, an order for a compliance program, and a pecuniary penalty of $250,000.

The agreed facts

RL Adams’ business

12 On 11 December 2014, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the Commission) commenced proceedings against RL Adams. It sought declarations, and other relief, that RL Adams had engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(a) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

13 Subsequently, the Commission and RL Adams agreed a statement of facts for the purposes of this penalty hearing under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). This discussion draws from those agreed facts.

14 Around 31 December 2013, RL Adams commenced the business of producing and selling chicken eggs. RL Adams’ eggs were marketed and sold to retailers, who on-sold the eggs to consumers, as “free range” eggs.

15 RL Adams operated its business from two premises: (i) 24 Tummaville Road, Pittsworth, Queensland; and (ii) Lot 3121 at Oakey-Pittsworth Road, Springside, Queensland (Wingrave Farm). RL Adams operated its egg farm at Wingrave Farm. Approximately 83% of the eggs it marketed as “free range” from its premises at Wingrave Farm.

16 RL Adams’ eggs were labelled, and marketed to consumers, as “free range”. This labelling sought to differentiate RL Adams’ “free range” eggs from other eggs that were labelled as “cage”, which are eggs produced by laying hens housed in cages. The labelling also sought to differentiate its eggs from eggs that were labelled as “barn laid”, which are eggs produced by laying hens confined to barns.

17 During the December 2013 to October 2014 period, RL Adams sold eggs labelled as “free range” to consumers based in Queensland, the Northern Territory, and New South Wales. Its eggs comprised 0.2% of “free range” egg market share in Australia.

RL Adams’ egg cartons

18 From 31 December 2013 to 6 October 2014, RL Adams supplied for sale eggs produced by laying hens from Wingrave Farm. The eggs were packaged in cardboard cartons that included the following labels:

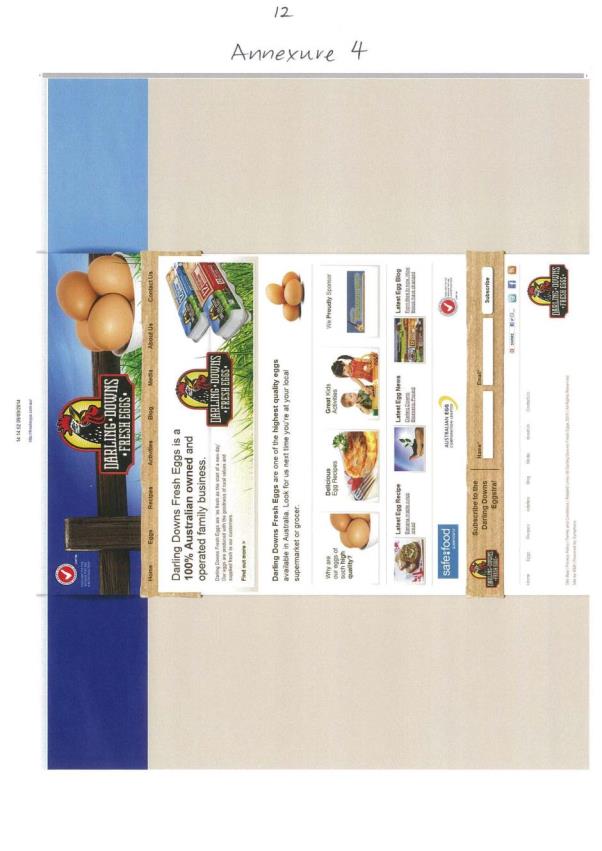

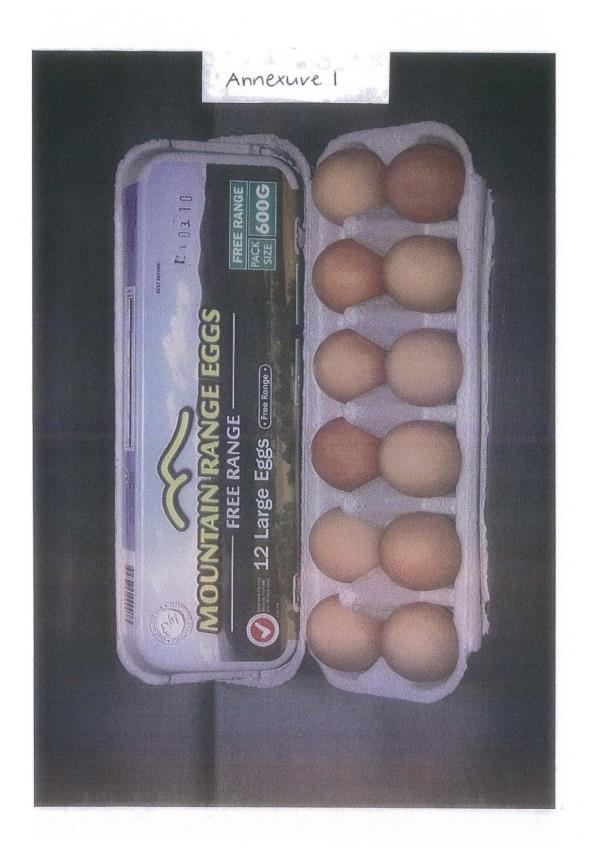

(1) Mountain Range Eggs Free Range Eggs 600g (Mountain Range Eggs 600g Carton), an image of which is Annexure 1 to the Orders;

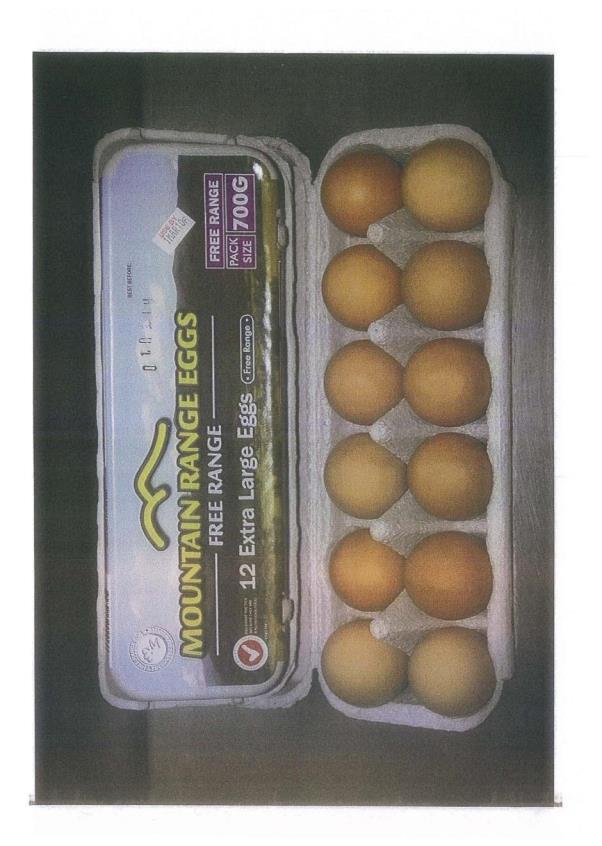

(2) Mountain Range Eggs Free Range Eggs 700g (Mountain Range Eggs 700g Carton), an image of which is Annexure 1 to the Orders; and

(3) Drakes Supermarkets Free Range Eggs 700g (Drakes Eggs 700g Carton), an image of which is Annexure 1 to the Orders.

19 These are collectively referred to as the Free Range Egg Cartons.

20 As can be seen in the Annexures to the Orders made, the Mountain Range Eggs 600g Carton and the Mountain Range Eggs 700g Carton displayed on the outside cover the words “free range” in three different places and displayed an image of a flat open range in front of a mountain range.

21 The Drakes Eggs 700g Carton displayed on the outside cover the words “free range eggs” in four different places and two images of eggs resting outside in green grass.

RL Adams’ Mountain Range Eggs Website

22 From 31 December 2013 to 6 October 2014, RL Adams advertised and promoted, and continues to advertise and promote, eggs sold in the Mountain Range Cartons by publishing the following website: www.fresheggs.com.au (Mountain Range Eggs Website), a copy of the relevant page is Annexure 1 to these reasons.

23 From at least May 2010, the Mountain Range Eggs Website displayed an image of two hens outdoors and the following words:

(1) “Mountain Range Eggs are produced by hens running freely on the farm during the day and housed at night to protect them from predators”;

(2) “Our free eggs [sic] are produced by free range farmers and are available in dozen packs”;

(3) “Free Range Eggs are produced by a production method where by [sic] the birds are free to roam the farm and are housed in barns at night to protect them from predators. Our Mountain Range is produced on free range farms. Important facts to note about free range production are:

(a) “The hens are free to range, forage and dust bathe. They are also protected from inclement weather with shedding which provides night time shelter, perches, feed, water and secluded comfortable egg layer boxes.

(b) The free range system incorporates natural poultry keeping methods. It is land based to ensure that the hens are happy, healthy and free and limited stocking density per acre is to provide both land and environmental sustainability.”

Contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law by RL Adams

24 The contraventions described below occurred between 31 December 2013 and 6 October 2014.

25 The Commission submitted, and RL Adams accepted, that it had made false and misleading representations by supplying the Free Range Egg Cartons and publishing the Mountain Range Eggs Website. Those “Free Range Representations” were based on the words and images on the Free Range Egg Cartons and Mountain Range Egg Website and included in the Annexure to these reasons, were that the eggs supplied in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced:

(1) by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day (where an “ordinary day” is every day other than a day when on the open range weather conditions endangered the safety of the laying hens or predators were present or the laying hens were being medicated); and

(2) by laying hens most of which moved about freely on an open range on most days.

26 The Free Range Representations concerned the quality, history, nature, and characteristics of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons.

27 Between 31 December 2013 and October 2014, Wingrave Farm had two barns (Barn 1 and Barn 2). Those barns housed laying hens that produced eggs which RL Adams marketed and sold as “free range”.

28 From 31 December 2013, the hens were housed in Barn 1. Barn 1 operated with two openings through roller doors.

29 From March 2014, the hens were housed in Barn 2. Barn 2 operated with three openings through roller doors.

30 The openings in Barn 1 and Barn 2 were elevated off the outdoor range adjacent to the barns. There were no fences around each barn and no ramps installed to permit the laying hens inside the barns to use the outdoor range. The roller doors were kept shut at all times so that none of the laying hens were able to, nor did they, access the outdoor range adjacent to Barn 1 and Barn 2.

31 The effect of the use of Barn 1 and Barn 2 was that the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons were produced by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were unable to, and did not, move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day from 31 December 2013 until 6 October 2014 (in relation to Barn 1) and from March 2014 until 6 October 2014 (in relation to Barn 2).

32 Unlike a case such as Pirovic Enterprises, there was no evidence in this case of the precise circumstances which falsified the representation. In other words, although the hens in Barns 1 and 2 were not “free range”, there was no evidence of the extent to which the hens could “range” within the barns. In Pirovic Enterprises there was evidence that from January 2012 to March 2013, within one of the barns, there were between 3,439 and 4,814 birds per metre width of opening, although the evidence was led in that case due to dispute about whether the hens could realistically use exits from the barns.

33 It is properly, and correctly, admitted by RL Adams that the Free Range Representations were false or misleading representations as to the quality and history of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons and that the representations were liable to mislead the public as to the nature and characteristics of the eggs contained in the Free Range Egg Cartons.

34 I find that RL Adams committed the following contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law because it:

(1) engaged in conduct in trade or commerce that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18;

(2) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, and the promotion of the supply of goods, made misleading representations that the goods were of a particular quality, or had a particular history in contravention of s 29(1)(a); and

(3) engaged in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of any goods, in contravention of s 33.

Penalty considerations and the range of penalties

35 Under s 224(3) of the Australian Consumer Law, the pecuniary penalty is not to exceed $1.1 million for each act or omission concerning ss 29(1)(a) and 33 (both of which are contained in Part 3-1).

36 Both the Commission and RL Adams submitted that the contraventions in this case should be treated as a single course of conduct and subject to a single penalty. There is authority to support that submission as a general practice, although it is not a rule of law: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Rural Press Ltd [2001] FCA 1065; [2001] ATPR 41–833 [19] (Mansfield J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 559; (2002) 190 ALR 169, 179-180 [38] (Finkelstein J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CI & Co Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1511 [27] (North J).

37 The authorities above do not require that a series of contraventions, involving different acts, be treated as a single course of conduct. Rather, the approach to be taken is based upon the principle of totality which requires that the total penalty for related offences should not exceed that which is proper for the entire contravening conduct. In the circumstances of this case, I consider that the totality principle should apply and the contraventions treated as a single instance of contravening conduct. These circumstances include that the conduct involved a series of very closely related contraventions, over approximately 9 months (which is considerably shorter than some other cases), that this was the first occurrence of these contraventions which occurred from the time that RL Adams commenced operation, and the early admission of responsibility by RL Adams coupled with its assistance to the Commission.

38 Although I have applied the totality principle in this case, and although both parties effectively submitted that it should be applied, there are some considerations pointing against application of the principle in a manner which would treat the pecuniary penalty contraventions by RL Adams as if they were a single act. Those considerations include the difference between the representations on Free Range Egg Cartons and those on the Mountain Range Egg Website, in the context of the need for general deterrence.

39 Section 224(2) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

40 There will be very few facts that are not included within the breadth of these matters. For instance, the “circumstances” in which the act takes place includes circumstances which precede the act as well as those which are contemporaneous to it.

41 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; (2011) 282 ALR 246, 250-251 [11], Perram J described a number of matters which could be taken into account under the equivalent provision to s 224. That list was referred to without demur on appeal: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249, 258 [37] (the Court). It has also been relied upon on numerous occasions although, as senior counsel for the Commission accurately submitted, lists of factors only serve as general guidance:

(1) the size of the contravening company;

(2) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(3) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at some lower level;

(4) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act (or the new Australian Competition and Consumer Law) as evidenced by educational programmes and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(5) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention;

(6) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(7) the financial position of the contravener; and

(8) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

42 To these factors can be added:

(9) whether the contravening company made a profit from the contraventions;

(10) the extent of the profit made by the contravening company; and

(11) whether the contravening company engaged in the conduct with an intention to profit from it.

43 Factors (9) to (11) are important for reasons of both general and specific deterrence. The need for deterrence is iterated, and reiterated, constantly in pecuniary penalty cases. This highlights the importance of deterrence in Australian case law in this area. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640, 659 [66], French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ in quoted from the Full Court of the Federal Court that a penalty “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. ... [T]hose engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.” See also Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076, 51,152 (French J).

44 The current state of Australian law after the decision of the High Court of Australia in Barbaro v The Queen [2014] HCA 2; (2014) 253 CLR 58 arises from the decision in Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCAFC 59. In that case the Full Court of the Federal Court held that the decision in Barbaro applies to civil penalty cases and that (at [239]) “[t]he impermissible expression of an opinion as to the amount of the penalty reflects a well-established limitation upon the ambit of a party’s right to make submissions”.

45 Unfortunately, RL Adams made a submission that it was willing to submit to a pecuniary penalty of $250,000. Senior counsel for the Commission correctly submitted that such a submission is directly inconsistent with the reasoning in CFMEU. The Commission’s submission is correct. There is no foundation in the CFMEU decision for a submission to be made of the nature that was made by RL Adams.

46 Counsel for RL Adams sought to draw support from [241] of the CFMEU decision. He submitted that this paragraph permitted RL Adams to make submissions about a “significant” penalty. In that paragraph the Full Court said:

As to an agreed penalty, we have previously indicated that any admission of liability may be a relevant consideration in sentencing or imposing a pecuniary penalty. Willingness to submit to the imposition of a substantial penalty may also be relevant in that way. However, even if the offender nominates a substantial figure as the penalty to which it will submit, the Court must still fix the appropriate penalty, taking into account such contrition as well as all other relevant considerations. As we have said, any such agreement is no more than an expression of a shared opinion, and therefore inadmissible. As we have also said, the amount of the agreed penalty may simply reflect the point at which each party considers that it is in its interest to agree. In either case, the agreed amount offers no assistance in fixing the amount of the appropriate penalty. (Italics in original, bold emphasis added).

47 Two points should be made about this paragraph.

48 First, the word “significant” is not used. The Full Court refers to a “substantial” penalty. This is a penalty which has more than an insubstantial effect.

49 Secondly, there is a difference between accepting the imposition of a substantial penalty and undertaking to pay it, which is evidence of contrition, and the nomination of the amount of that penalty. Nothing in the decision in CFMEU, nor the passage quoted above (which includes the qualification “Even if”) suggests that a respondent can legitimately nominate the amount of a penalty to which it would be prepared to submit. The submission by RL Adams about the amount of the penalty to which it was prepared to submit should not have been made.

50 However, the Full Court in CFMEU did accept, at [252], that “the development of a consistent approach to the fixing of pecuniary penalties necessitates reference to prior decisions”. In a criminal sentencing approach this reference to prior decisions is sometimes described as identification of a “range” of sentences. Counsel for both parties properly made reference to a number of cases, including some of the cases discussed in the introduction to these reasons.

51 With contraventions of the nature of those in this case, the breadth and variety of the many factors involved in an assessment of pecuniary penalties has the effect that any range of penalties derived from previous cases can only ever be stated in very broad terms. Indeed, the well-established term “range” can sometimes be misleading. It might be more accurate to say that an assessment of the general run of cases, including the cases mentioned in the introduction to these reasons, has so far revealed that penalties for contraventions by corporations have varied from $100,000 to $400,000.

52 Two points should be made about this general run of cases.

53 First, the penalties in the general run of cases can be of limited utility when descending to the particular circumstances of a case in a context such as this where the facts can differ greatly and where there is not yet a significant volume of cases to establish a general run. For instance, in one case involving a significant penalty, the respondents (in Turi Foods (No 5)) were Australia’s largest chicken meat producers and made no admission of responsibility. In another, the conduct (in Pepe’s Ducks Ltd) occurred over a period of 8 years by a company that supplied 40% of the Australian market, selling 80,000 ducks a week. If the view were reached that the penalties in these cases were now inadequate to establish general deterrence then the penalties in the general run of cases could shift substantially.

54 There may be a basis for a future submission that the penalties in Turi Foods (No 5) and Pepe’s Ducks Ltd (which was an agreed penalty) are no longer adequate as guides for general deterrence. There does appear, at first blush, to be a disproportionately large number of penalty decisions concerning “free range” representations in recent years particularly in circumstances in which, as senior counsel for the Commission submitted, contraventions of this nature are not easily investigated. However, counsel for RL Adams submitted, and I accept, that any such conclusion would depend upon some degree of analysis, and possibly statistical analysis, of past contravening. No such submissions were made in this case.

55 On my assessment of the published decisions concerning “free range” type representations, although I consider that there may be doubt that the penalties imposed in those cases remain an adequate general deterrent, on the information before me and in the absence of any evidence or submissions on this point I will not treat those cases, and the general run of cases to date, as revealing any inadequacy for general deterrence such that it might now be manifestly inadequate for penalties to be imposed such as those awarded in some of the previous cases I have mentioned: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chopra [2015] FCA 539 [52]-[53].

56 The suggestion that particular submissions concerning general deterrence might be made is not to suggest, contrary to CFMEU, that parties should make submissions concerning any particular amount of penalty or any range of penalties. General deterrence is, on the authorities, an extremely relevant concern. It is appropriate that submissions be made about factors with which the Court is concerned. Senior counsel for the Commission made careful and helpful submissions about general deterrence generally.

57 Secondly, some of the cases from which the general run of penalties can be assessed involved orders about the amount of the penalty which reflect those proposed by agreement of the parties. In CFMEU, the Full Court said at [238] that “where a penalty has been fixed in that way, the decision may not be treated as helpful in future cases, save to the extent that it indicates a position adopted by a regulator to which it should be held in later cases”.

58 I turn then to my reasoning concerning several of the central considerations in relation to penalty.

Size of RL Adams, its financial position and profits made by its representations

59 RL Adams obtained a premium price compared with “barn laid” eggs by selling eggs labelled as “free range”. That premium per dozen eggs was approximately 54 cents.

60 Over the financial years ending 30 June 2013 and 30 June 2014, RL Adams’ financial results from the sale of all its eggs (labelled as “cage” and “free range”) were as follows including turnover from eggs obtained from other producers:

Eggs labelled “cage” | Eggs labelled “free range” | |

Annual turnover (RL Adams eggs) | $ 7,633,043 | $11,982,701 |

Gross profit | $ 3,851,330 | $ 5,148,892 |

Annual turnover (other producers) | $ 717,753 (30 June 2013) | |

Annual turnover (RL Adams & others) | $1,173,500 (30 June 2014) |

61 During the 31 December 2013 to October 2014 period, RL Adams obtained the following in relation to its eggs labelled as “free range” from Wingrave Farm:

Total turnover | $ 1,009,202 |

Gross profit | $ 349,281 |

Gross profit margin (sales less cost of goods sold) | 35% |

Additional gross profit margin from “free range” label | 30% |

The gross profit if eggs sold as “free range” had been sold as “barn laid” | $ 247,083 |

62 RL Adams’ overall expenditure was not reduced by selling eggs labelled as “free range”. There was no agreed fact, nor any evidence, concerning the relative levels of demand for “barn laid” or “free range eggs”. Hence, the only conclusion that can be drawn from the last figure in the paragraph above is that the additional gross profit that would have been obtained if those eggs that had been labelled “barn laid” had been sold as “free range” was $102,198.

63 The profit made by RL Adams was at the expense of purchasers. However, the representations also caused unquantifiable losses to other sellers of free range eggs.

Co-operation with the Commission and admission of culpability

64 On 15 September 2014, Commission investigators attended Wingrave Farm. An employee of RL Adams provided the investigators with access to the premises to inspect Wingrave Farm. The employee followed the Commission investigators throughout the inspection, and co-operated by answering all questions as to the confinement of the laying hens and the reasons for this.

65 In the course of the ACCC’s investigation about the contraventions, RL Adams disclosed all relevant information including, but not limited to:

(1) financial information;

(2) advertising and promotional activities;

(3) egg production and sales;

(4) biosecurity measures; and

(5) “free range” farming conditions and rearing practices.

66 After the ACCC commenced these proceedings, RL Adams sought advice about its position and filed a defence, defended the proceedings to preserve its interest while investigations were being conducted and advice was being sought, and after obtaining necessary legal advice, admitted it contravened the Australian Consumer Law and agreed to settle the proceedings with the Commission on 30 June 2015.

67 RL Adams’ co-operation, and acceptance of responsibility, has saved the Commission, the court, the witnesses who would have given evidence, and the community the cost and burden of litigating a fully contested trial, although both parties have incurred legal costs in this proceeding.

RL Adams did not intentionally infringe the Australian Consumer Law

68 It is an agreed fact, and accepted to be true, that RL Adams told the Commission that between 16 October 2013 and 29 November 2013 RL Adams had received advice from the Commonwealth Department of Agriculture about an outbreak of H7 highly pathogenic avian influenza in a farm of laying hens located near Young, New South Wales. From November 2013 RL Adams was advised by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (Qld) about outbreaks of Infectious Laryngotracheitis in Central Queensland, South Burnett, Maleny and the Darling Downs.

69 RL Adams also told the Commission that the confinement of the free range laying hens was informed by biosecurity conditions at the time. It is also accepted that RL Adams genuinely believed this to be the case.

70 At all times during the December 2013 to October 2014 period, RL Adams also believed that it was complying with the Primary Industries Standing Committee's Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals-Domestic Poultry (41th edition, SCARM Report 83, 2002).

71 As counsel for RL Adams properly accepted, these matters do not detract from the intentional nature of RL Adams’ conduct. In marketing its eggs, RL Adams did not have regard to questions to which it should have had regard, including whether the eggs supplied in the Free Range Egg Cartons and which it knew had been described as “free range” were produced:

(1) by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that the laying hens were able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day (which it knew was not the case); and/or

(2) by laying hens most of which moved about freely on an open range on most days.

72 In other words, RL Adams knew that it had made the Free Range Representations, and it knew that its hens were not free range. As counsel for RL Adams properly accepted, the considerations in [68]-[70] above, however, illustrate the motive for RL Adams’ conduct.

73 I also accept that although RL Adams’ conduct was intentional in the sense I have described at [71], RL Adams did not intentionally set out to contravene the Australian Consumer Law when it commenced its operations in December 2013 and until the contraventions ceased in October 2014: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 399 [48] – [49] (White J).

74 On about 30 October 2014, RL Adams also modified the contents of the Mountain Range Eggs Website to include the following additional statements:

Mountain Range Eggs are produced from farms that abide by the Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals (MCOP).

In accordance with this welfare code and in the event of adverse weather or serious outbreaks of disease our free range hens, under these conditions, may temporarily remain within the protection of the barn. When these adverse conditions subside our hens will be free to roam again.

75 On about 16 December 2014, RL Adams further modified the contents of the pages of the Mountain Range Eggs Website, so that they included the following statements:

Free Range Eggs are produced by a production method where by the birds are free to roam a range area and are housed in barns at night to protect them from disease and predators. Important facts to note about free range production are:

The hens are free to range. They are also protected from disease and inclement weather with shedding which provides night time shelter, feed, water and secluded comfortable egg layer boxes.

The free range system incorporates natural poultry keeping methods. It is land based to ensure that the hens are happy, healthy and limited stocking density per acre is to provide both land and environmental sustainability.

First contraventions

76 RL Adams has not previously been found by a court to have contravened any provision of the Australian Consumer Law or to have engaged in similar conduct to that alleged in this proceeding.

Extent of the contraventions

77 During the December 2013 to October 2014 period the contravening conduct referred to above was directed to consumers and retailers. RL Adams supplied eggs labelled as free range to approximately 63 retailers located in Queensland, New South Wales and the Northern Territory.

78 The loss and damage suffered by consumers cannot be quantified but will include the price premium paid by consumers to acquire eggs they thought were produced by laying hens that were farmed in conditions so that most of the laying hens were able to, and did, move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day. As I have explained, that was not the case.

Lack of a compliance program

79 During the December 2013 to October 2014 period, RL Adams did not have a compliance program to assist it to meet its obligations under the Australian Consumer Law. It is common ground that it now has such a programme.

RL Adams acted through senior management

80 During the December 2013 to October 2014 period, RL Adams acted through its senior management.

Conclusions and orders

81 I commence with my conclusions in relation to the appropriate pecuniary penalty.

82 The assessment of a pecuniary penalty is a discretionary judgment involving instinctive synthesis in the sense of a need to take “account of all of the relevant factors and to arrive at a single result which takes due account of them all”: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357, 374 [37] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ); Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at 611-612 [74]- [76] (Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ).

83 In the circumstances of all of the factors I have described, and in the context of a maximum penalty for a single act or omission of $1.1 million, I consider that the appropriate penalty is $250,000. In particular, the most significant influencing factors which mitigate the severity of the penalty are RL Adams’ early admission of responsibility and its very substantial co-operation with the Commission in relation to this first contravention. As a broad summary, other relevant matters include the non-deliberate nature of its conduct (including the reasons for RL Adams placing its hens in barns), the relatively small size of its operation compared with some other producers, the profits from its infringing conduct being made over 9 months and being around $100,000 (if all “free range” eggs had been sold as “barn laid” eggs). As I have explained, my assessment that this penalty is appropriate is based on the limited material, and limited submissions, that I have before me concerning general deterrence. Although the submissions made in this case by counsel for the Commission were otherwise impeccable, in future cases, and subject to the state of the Australian authority concerning the appropriate boundary of submissions, it may be appropriate for more substantial submissions to be made concerning general deterrence and the totality principle.

84 I had reached a preliminary conclusion that this amount was appropriate before reading the reply submission from RL Adams. As I have explained, those reply submissions impermissibly suggested a penalty of $250,000. On the current state of the law that submission should not have been made. In oral submissions counsel for RL Adams submitted that the intention behind his submission was that RL Adams express contrition by agreeing to submit to the imposition of a penalty that is at the “high” end. I do not consider that this penalty is “high”. Indeed, it had appeared to me, and still does appear to me, that it was both appropriate and the most reasonable penalty in all the circumstances. However, I do accept that a submission of a willingness to pay a substantial penalty is evidence of contrition.

85 This case may illustrate reasons for the concern expressed in Barbaro (in a criminal context) and CFMEU about counsel making submissions that a particular penalty that should be imposed. Although I have disregarded the relevant paragraph from RL Adams’ submissions, a lay observer might have (incorrectly) reached the conclusion that I would not have been prepared to reduce the penalty below that assessment if I had thought that a lower penalty were appropriate. Perhaps even worse, a lay observer might also (incorrectly) have surmised that RL Adams had been ordered to pay only the penalty that it considered to be the price of its infringing conduct. It would, however, have been improper of me to depart from my view about the appropriate penalty simply because that submission had been made by RL Adams.

86 Apart from penalty, the parties both proposed that declarations be made declaring the infringements that had occurred. The parties also sought publication orders concerning the contraventions. Both types of order are appropriate.

87 In relation to the proposed declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), this case involved a real question in which the Commission had an interest, and as to which RL Adams was in the position of a proper contradictor: Forster v Jododex Aust Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421, 437-438 (Gibbs J). It is in the public interest that the declaration be made as it serves to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the Commission’s claim, inform consumers of the contravening conduct of RL Adams and deter other corporations from contravention: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v The Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; [2007] ATPR 42-140 [6] (Nicholson J). The form of the declarations, and the annexures to it, are appropriate.

88 The parties also proposed that compliance orders be made under s 246 of the Australian Consumer Law requiring RL Adams to establish and implement a training program to assist it in ensuring that it avoids future contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law. Although RL Adams now has in place a compliance program, it is appropriate that the order be made in terms which links the training required to the relevant conduct, focusing on the provisions of Part 2-1 and Part 3-1 of the Australian Consumer Law.

89 The Commission sought an injunction which has the broad effect of restraining RL Adams for a period of 3 years from using the words “free range” on its products when that is not the case. The injunction sought was as follows:

An injunction restraining the Respondent, whether by itself, or its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, in connection with the supply of eggs in trade or commerce from making any representation, including by using the words “free range”, on any packaging, website or other promotional material that the eggs it sells are produced:

(a) by laying hens that are farmed in conditions so that the laying hens are able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day; and

(b) by laying hens most of which move about freely on an open range on most days,

when that is not the case

90 There is power to grant such an injunction by s 232(4) of the Australian Consumer Law. That section confers that power in circumstances including (i) whether or not it appears to the court that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in conduct of a kind referred to in that subsection, (ii) whether or not the person has previously engaged in conduct of that kind, and (iii) whether or not there is an imminent danger of substantial damage to any other person if the person engages in conduct of that kind. See also, in circumstances comparable to this case, Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v G O Drew Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1246; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bruhn [2012] FCA 959; [2012] ATPR 42-414.

91 RL Adams submitted that there is no basis for the order of an injunction. In particular, RL Adams submitted that there is no utility in imposing an injunction because it does nothing more than restrain RL Adams from breaching the Australian Consumer Law. RL Adams also submitted that the Australian Consumer Law does not contemplate an injunction being ordered in the ordinary course in the face of statutory sanctions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 146; (2007) 161 FCR 513, 542-543 [108] (the Court).

92 I do not accept that the injunction in the proposed form is inutile in either of these senses. As senior counsel for the Commission submitted, there is utility in an injunction which provides a “lasting result” from proceedings and avoids further issues about whether RL Adams will continue to comply with the Australian Consumer Law. Senior counsel for the Commission submitted that there may be concern about what is currently meant by the second paragraph of RL Adams’ website advertisement set out above at [74]. The injunction as framed is intended to have the effect of avoiding future controversy.

93 On balance, however, I do not consider that my discretion should be exercised to order such an injunction.

94 The primary reason why I decline to exercise my discretion to order an injunction is that I do not consider that there is any likelihood that RL Adams would repeat its contraventions. If it did the penalties would be severe. Its contraventions occurred at the commencement of its operations. It admitted the contraventions at an early stage, co-operated substantially with the Commission, and has put in place compliance programs which will continue in a directed fashion.

95 A secondary reason why I decline to exercise my discretion to order an injunction in the terms sought is that there is potential (and I put the matter no higher than that) for there to be dispute about the terms of the injunction. Initially, this reason appeared to me to be quite significant. However, after reply submissions from senior counsel for the Commission, I do not consider it to be as significant.

96 Counsel for RL Adams submitted that although it was accepted that a contravention had occurred on the facts of this case and that there was clarity in declaring a contravention in this case, there might be other circumstances in which there is uncertainty about what is meant by “most” hens or “most days”. I accept that there is uncertainty in these terms and that this militates against the grant of an injunction. But, on the basis of the submissions made this morning, it currently appears to me that this uncertainty arises only at the penumbra and not at the core. The basis for my findings of contravention and declarations, which is accepted by the parties, is that the hens were not able to move around freely on an open range on an ordinary day and did not do so on most days. As senior counsel for the Commission submitted, the Court need not be concerned by an extreme case where the Commission brings an action for contempt based upon a circumstance involving “lazy hens” who have the opportunity to range freely but choose not to do so. Nevertheless, there remains some merit in this concern in that the effect of an injunction in the terms described would move the penumbral circumstances of uncertainty from being issues to be resolved in a case brought for a contravention to an issue to be resolved in a case brought for contempt.

97 Finally, it is appropriate that RL Adams pay the Commission’s costs of this proceeding fixed in the sum of $25,000.

I certify that the preceding ninety seven (97) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Edelman. |

Associate:

Annexure 1