FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Investa Properties Pty Ltd v Nankervis (No 7) [2015] FCA 1004

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

IN RESPECT OF THE AMENDED APPLICATION FILED ON 17 OCTOBER 2013 THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Ashley Nankervis breached his fiduciary duties to the first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ACN 084 407 241, in respect of Lot 191 and Lot 170 (as defined in the attached reasons for judgment).

2. Ashley Nankervis breached his statutory obligations to the first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ACN 084 407 241, under section 182 and section 183 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in respect of Lot 170.

3. Adam Barclay breached his fiduciary duties to the second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd ACN 098 527 390, in respect of Lot 191.

4. Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 breached its fiduciary duties to the second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd ACN 098 527 390, in respect of Lot 191.

5. Otherwise:

(a) Ashley Nankervis did not breach his statutory obligations to the first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ACN 084 407 241, under section 182 and section 183 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), in respect of Lot 191;

(b) Ashley Nankervis was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties to either of the applicants in respect of the decommissioning and relocation of a sales office, formerly located on the Brentwood Site (as defined in the attached reasons for judgment);

(c) Ashley Nankervis was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties or statutory obligations to the second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd ACN 098 527 390, in respect of Lot 191 or Lot 170;

(d) Adam Barclay was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties to the second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd ACN 098 527 390, in respect of Lot 170;

(e) Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties to the second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd ACN 098 527 390, in respect of Lot 170;

(f) Adam Barclay was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties to the first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ACN 084 407 241, in respect of Lot 191 or Lot 170;

(g) Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 was not subject to, and did not breach, any fiduciary duties to the first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ACN 084 407 241, in respect of Lot 191 or Lot 170.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The cross-claim of Ashley Nankervis against Adam Barclay and Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 filed 15 November 2013 be dismissed.

2. The cross-claim of Adam Barclay against Ashley Nankervis filed 18 November 2013 be dismissed.

3. The cross-claim of Adam Barclay against Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 filed 15 December 2012 be dismissed.

4. The cross-claim of Adam Barclay against Vero Insurance Limited ABN 48 005 297 807 filed 15 December 2012 be dismissed.

5. The cross-claim of Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 against Adam Barclay filed 10 December 2012 be upheld.

6. Costs be reserved.

7. The matter be listed for further directions at 9.30 am on 21 October 2015 in respect of:

(a) remedies of the applicants under the amended application filed 17 October 2013;

(b) remedies of Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd ACN 128 863 230 in respect of its cross-claim filed 10 December 2012;

(c) costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 231 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | INVESTA PROPERTIES PTY LTD (ACN 084 407 241) First Applicant INVESTA RESIDENTIAL GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 098 527 390) Second Applicant |

AND: | ASHLEY COLIN NANKERVIS First Respondent ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY Second Respondent OLIVER HUME SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND PTY LTD (ACN 128 863 230) Fourth Respondent |

and between: | OLIVER HUME SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND PTY LTD (ACN 128 863 230) Cross-Claimant |

and: | ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY Cross-Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | ASHLEY COLIN NANKERVIS Cross-Claimant |

AND: | ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY First Cross-Respondent OLIVER HUME SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND PTY LTD (ACN 128 863 230) Second Cross-Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY Cross-Claimant |

AND: | VERO INSURANCE LIMITED (ABN 48 005 297 807) Cross-Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY Cross-Claimant |

AND: | OLIVER HUME SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND PTY LTD (ACN 128 863 230) Cross-Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | ADAM KIMBERLY BARCLAY Cross-Claimant |

AND: | ASHLEY COLIN NANKERVIS Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | COLLIER J |

DATE: | 10 SEPTEMBER 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Overview of the proceedings

1 The claims in these proceedings arise from the sale of two parcels of land in south east Queensland, namely:

"Lot 191", which formed part of a residential property development called "Brentwood" or "Brentwood Site", and which is located on Augusta Parkway at Bellbird Park, near the city of Ipswich in Queensland; and

"Lot 170" (referred to at various times as the "Fossil Site", "Brittains Road" and "The Outlook").

2 The applicants, which are companies forming part of the Investa Property Group, claim that the two properties were sold at an undervalue as a result of the actions of:

Mr Ashley Nankervis (the first respondent), a former senior employee;

Mr Adam Barclay (the second respondent), an individual real estate agent who had an involvement in the sales; and

Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd (the fourth respondent) ("Oliver Hume SEQ"), the real estate agency company of which Mr Barclay was at material times director and general manager.

3 The details of the applicants' claims against the respondents are set out in the amended application and the third version of the statement of claim, both filed on 17 October 2013. However, stated succinctly, the applicants claim that they have suffered losses in respect of the sales of Lot 170 and Lot 191 because Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay, in breach of their respective duties to the applicants, and for their own benefit, caused those properties to be sold to entities with which they were associated, at an undervalue. Any liability of Oliver Hume SEQ in these proceedings arises solely because of the actions of Mr Barclay.

4 As is already clear, several iterations of the pleadings have been filed in these proceedings. Currently before the Court are the following applications:

the amended application filed on 17 October 2013 ("amended application");

the statement of claim (version 3) filed on 17 October 2013 ("amended statement of claim");

a cross-claim brought by Mr Nankervis against Mr Barclay and Oliver Hume SEQ filed 15 November 2013;

a cross-claim brought by Mr Barclay against Mr Nankervis filed 18 November 2013;

a cross-claim brought by Mr Barclay against Oliver Hume SEQ filed 15 December 2012;

a cross-claim brought by Mr Barclay against Vero Insurance Limited ABN 48 005 297 807 filed 15 December 2012; and

a cross-claim brought by Oliver Hume SEQ against Mr Barclay filed 10 December 2012.

5 In the circumstances it is both logical and efficient to deal with the claims of the applicants against the respondents before turning to the cross-claims in this case.

6 Finally, I note that the applicants have elected to claim equitable compensation because of the sale of the relevant properties at an undervalue, rather than claiming an account of profits. To that extent, it is necessary that I should consider whether Lot 191 and Lot 170 were sold at an undervalue. An estimate of equitable compensation payable (if any), as well as any award of costs is, however, an issue for consideration following further submissions from the parties.

The parties

The Investa Group

7 The Investa Property Group owns and manages real estate in Australia. "Investa Land" is a name used to refer to the sub-group of companies which manages property developments, and includes the two applicant companies. The first applicant, Investa Properties Pty Ltd ("Investa Properties"), acted as the land development division of the Investa Property Group (and in that capacity was also known and referred to as "Investa Land"). The second applicant, Investa Residential Group Pty Ltd (formerly known as Clarendon Residential Group Pty Ltd) ("Investa Residential") is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Investa Properties and was the registered proprietor and vendor of the land forming the subject of these proceedings.

8 In the amended statement of claim, the applicants plead that for the purposes of carrying out land development, Investa Properties:

a) employed all staff of the Investa Property Group;

b) maintained offices and equipment;

c) engaged architects, planners, engineers, other professional consultants, builders and contractors;

d) provided or arranged finance for the purpose of acquiring and developing land;

e) incorporated or acquired subsidiaries for the purposes of acquiring land at its direction, holding the legal title to land on its behalf, selling land at its direction, and remitting the proceeds of sale at its direction; and

f) through its directors, officers and employees, implemented the policy decisions of Investa Property Group Holdings Pty Ltd and made all managerial level decisions relating to the acquisition, development and sale of land.

9 It is uncontentious that Investa Residential, at the direction of Investa Properties, was responsible for contracting with real estate agents in relation to the sale and marketing of the land the subject of these proceedings.

Investa Land's managers and employees

10 Investa Land's operations were managed by a Group Executive, who at times material to these proceedings was Mr Lloyd Jenkins. As Group Executive, Mr Jenkins was responsible for approving the acquisition, sale and development of land or referring decisions to the Chief Executive Officer, depending on the amount of money involved. The general managers in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia reported to Mr Jenkins as Group Executive. At various times, the Queensland general managers were Mr Mark Waters, Mr Gavin Stubbs, Mr Lloyd Jenkins (in addition to his responsibilities as Group Executive) and Mr Cameron Holt.

Ashley Nankervis

11 The first respondent, Mr Ashley Nankervis, was employed by Investa Properties from around 5 April 2006 pursuant to a written contract of employment dated on or about 8 March 2006. Initially he was employed in the role of Development Manager and later as Senior Development Manager. Mr Nankervis was responsible for the overall management of the Brentwood Site and for signing off on all relevant "stage releases" of the Brentwood Site.

12 The applicants pleaded that Mr Nankervis was employed by the first applicant in a senior role between 5 April 2006 and 26 May 2010. These dates were not disputed by Mr Nankervis.

Oliver Hume South East Queensland Pty Ltd and Adam Barclay

13 The fourth respondent, Oliver Hume SEQ, was a licensed real estate agency under the now-repealed Property Agents and Motor Dealers Act 2000 (Qld) ("PAMDA") during the relevant period.

14 The second respondent, Mr Adam Barclay, was at material times a director and employee of Oliver Hume SEQ and a licensed real estate agent under PAMDA. In 2006, Mr Barclay became Oliver Hume SEQ's general manager. In relation to both sites the subject of these proceedings, Mr Barclay was the primary contact in Oliver Hume SEQ in dealings with either or both of the applicants.

15 The roles of Oliver Hume SEQ and Mr Barclay so far as concerns the two properties were the subject of dispute. It is not in dispute that Oliver Hume SEQ was formally engaged in accordance with a "Form 22a - appointment of real estate agent" under PAMDA for a period of time in relation to the marketing and sale of Lot 191. It is equally common ground that no equivalent form was ever completed by the parties in relation to Lot 170.

The properties

Lot 191

16 Lot 191 is the smaller of the two lots of land the subject of these proceedings. It is a 1,079 square metre parcel located within the Brentwood development, being part of the Stage 2A development of the Brentwood site.

17 On or about 16 July 2009, Investa Residential appointed Oliver Hume SEQ as a real estate agent using the PAMDA Form 22a. It was an exclusive agency appointment, relating to Stage 2A (that is, Lots 173 to 215) and Stage 2B (Lots 216 to 249) of the Brentwood Site.

18 On or about 21 October 2009, a delegated authority approval submission for the development and sale of Stage 2A lots at the Brentwood Site was prepared by Mr Damian Long, and recommended by Mr Nankervis and others, in terms recommending that lots be sold at an average lot price of $194,000. Specifically, Mr Long's submission recommended a sale price of Lot 191 of $210,000, being the listed price of $225,000 less a rebate of $15,000.

19 On or about 23 December 2009, Investa Residential entered a Deed of Put and Call giving call rights to Queensland Property Centre Pty Ltd ("Queensland Property Centre") for the purchase of Lot 191 with an exercise price of $195,000. In that deed, Queensland Property Centre was described as "the grantee".

20 Materially, the Deed of Put and Call executed by Investa Residential and Queensland Property Centre permitted the Call Option to be exercised by a nominee of the grantee. This in fact occurred. By contract of sale between Investa Residential and another entity, Spencer Projects Pty Ltd ("Spencer Projects") dated 25 June 2010, Lot 191 was sold to the nominee, Spencer Projects, for a contract price of $290,000, settling on 28 June 2010.

21 It appears that Queensland Property Centre was a company under the control of Mrs Kym Barclay, the wife of Mr Adam Barclay. Further it appears that Spencer Projects was a company of which Mrs Barclay was initially the sole director and shareholder, however on the day of registration Mrs Barclay appointed her daughter, Ms Jaide Spencer Crosbie as sole director, and transferred to her all of the company's shares.

22 The applicants submitted that they only retained $190,497.14 of the settlement monies and paid $96,000 to Queensland Property Centre pursuant to the terms of the Deed of Put and Call. The main allegation of the applicants in relation to Lot 191 is that it was sold at an undervalue and without full disclosure to a company owned and controlled by Mr Barclay's wife, Mrs Barclay. The applicants' case is that the true value of Lot 191 at the time of the deed was $290,000.

23 The applicants also say that Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay took steps to subdivide Lot 191 without disclosing that they were doing so and that, as a result, a sale price was approved for the property which did not reflect its true value.

Lot 170

24 Lot 170 was the larger of the two lots, being a 7.25 hectare parcel of land situated near the western boundary of the Brentwood Site. It is not in dispute that, in its raw state, the land was steep, and could be described as challenging for developers. It was sold as an en globo site, in that although it was intended for subdivision, it was sold as a single lot.

25 On or about 20 February 2009, Investa Residential entered into a deed of Put and Call, giving rights to a company, Two Eight Two Nine Pty Ltd ("Two Eight Two Nine"), with an exercise price of $1,454,545. A formal contract of sale was entered into between these parties on 25 June 2009. The sole shareholder of Two Eight Two Nine was Mr David Tonuri.

26 The applicants' position in the amended application was that the value of Lot 170 at this time was $3 million. This position appeared to vary during the proceedings, such that the applicants claimed in the amended statement of claim that Lot 170 was worth $4 million. During the proceedings the applicants' case was that the true value of Lot 170 was $4 million.

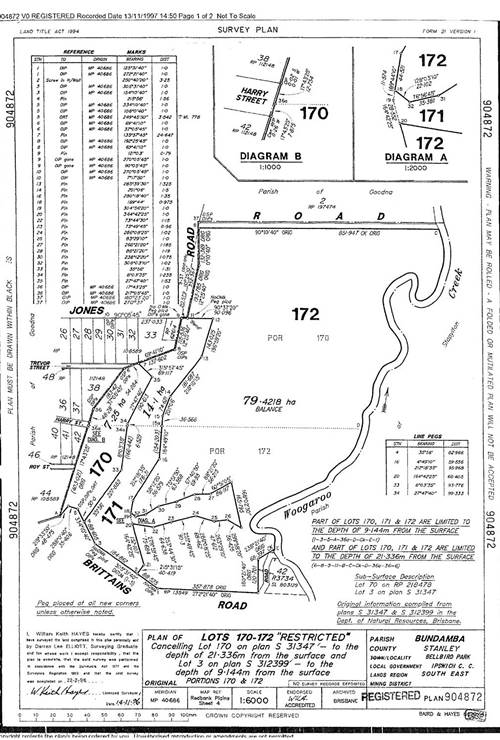

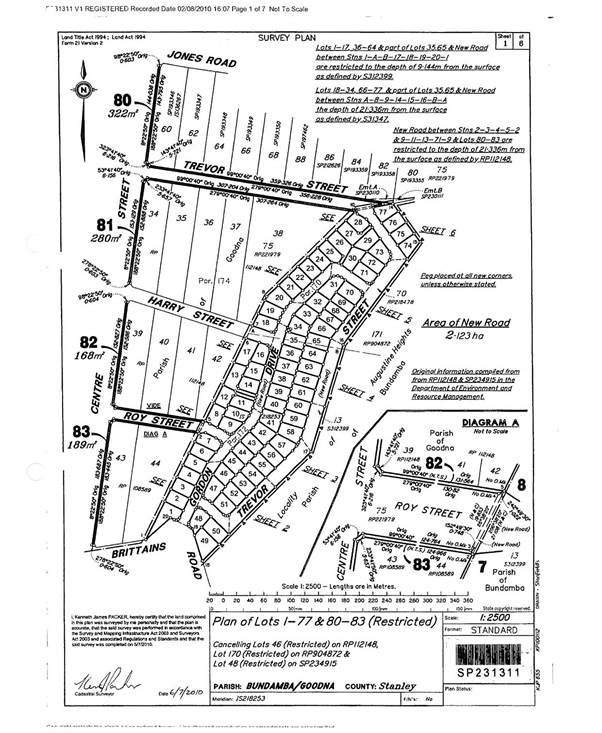

27 The applicants referred to two diagrams showing Lot 170 in its surrounding area, both before and after its subdivision.

28 The basis of the claims made by the applicants in respect of Lot 170 is that, at some time prior to 20 January 2009, Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay entered into an agreement with Mr Tonuri pursuant to which Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay would participate in and derive profits from the sale to Mr Tonuri or his nominee and the subsequent development of Lot 170. The existence of such an agreement is contested by Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay.

The sales office

29 The sales office owned by Investa Residential was located on the Brentwood Site. The applicants claim that in or around March 2010, it was removed and relocated to the site of a project owned by Mr Tonuri, at the instigation of Mr Nankervis, and that this was done without the authorisation of either applicant. The applicants claim that the cost of replacing the sales office is approximately $100,000.

30 The applicants seek relief against only Mr Nankervis in respect of the sales office.

DETAILS OF THE APPLICANTS' CLAIMS

31 The claims of the applicants against the respondents as set out in the pleadings may be summarised as follows.

As against Mr Nankervis

32 In the amended application the applicants plead:

1. Against the first respondent, Ashley Colin Nankervis

1.1. In respect of the land known as Lot 191, Brentwood Site:

(a) Mr Nankervis must account as a defaulting fiduciary to the applicants, Investa Properties and Investa Residential, for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

(b) Alternatively, Mr Nankervis must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them, for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

(c) Alternatively, Mr Nankervis must compensate Investa Properties pursuant to s 1317H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Pursuant to s 1317H(2), the damage suffered includes profits made by any person resulting from the contraventions of s 182 and 183 alleged (in paragraph 136 of the amended application), and includes the profit of $95,000 to Queensland Property Centre on completion of the sale to Spencer Projects.

1.2. In respect of the land known as Lot 170, Brentwood Site:

(a) At the election of Investa Properties or Investa Residential or both of them, Mr Nankervis must account as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties or Investa Residential or both of them for either:

(i) Any profit he or any entity that was associated with him, or that he controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine Pty Ltd, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or:

(ii) The value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $3,000,000 but Investa Residential received only $1,454,545.

(b) Alternatively, Mr Nankervis must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them, for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

(c) Alternatively, Mr Nankervis must compensate Investa Properties pursuant to s 1317H of the Corporations Act 2001. Pursuant to s 1317H(2), the damage suffered includes profits made by any person resulting from the contraventions of s 182 and 183 alleged (in paragraph 194 of the amended application).

1.3. Further, Mr Nankervis must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Residential, for the decommissioning and relocation of a sales office, formerly located on the Brentwood site.

33 In the amended statement of claim, the applicants plead further, in summary:

Investa Properties employed Mr Nankervis initially in the position of Development Manager and then in the position of Senior Development Manager (reporting to the Queensland General Manager) pursuant to a contract of employment signed by Mr Nankervis on 8 March 2006.

Mr Nankervis' duties included:

(a) preparing financial and feasibility reports and reporting to internal management, including making recommendations on relevant matters;

(b) project management including managing project negotiations and ensuring all contracts were accurately prepared and delivered in accordance with Investa Properties' obligations;

(c) managing all projects to ensure compliance with all relevant regulatory, legislative and corporate policy requirements and obligations;

(d) managing land sales including tracing of land sales on a weekly basis;

(e) managing project negotiations and ensuring the accurate preparation of contracts and liaising with and appointing contractors and planners on behalf of Investa Properties; and

(f) approving and/or recommending sales prices for lots within the Brentwood site.

By reason of the positions he held, the responsibilities he discharged, and the relationship between the applicants, Mr Nankervis was an employee of Investa Properties and owed fiduciary obligations to Investa Properties and Investa Residential.

Mr Nankervis also owed obligations to Investa Properties pursuant to s 182 and s 183 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ("the Corporations Act").

From at least 19 October 2009 to 29 October 2009 Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay were involved in taking steps to subdivide Lot 191 into two lots. This was before recommending to Investa Properties that Lot 191 be sold at $210,000 (after rebate), and without disclosing to Investa Properties or Investa Residential that he was involved in taking steps to subdivide Lot 191 into two lots.

On or about 18 December 2009 Mr Nankervis approved the sale price in respect of a Deed of Put and Call for Lot 191 to Queensland Property Centre in the amount of $195,000, being $15,000 less than the price after rebate that Investa Properties had approved on 23 October 2009. Mr Barclay's wife, Mrs Barclay, incorporated Queensland Property Centre on 21 October 2009, and for all intents and purposes, was the sole director and sole shareholder. At no time did Mr Nankervis disclose to Investa Properties or Investa Residential that Queensland Property Centre was owned and controlled by Mr Barclay's wife.

On 10 June 2010, Mrs Barclay incorporated Spencer Projects. On or about 18 June 2010, Mr Damian Long, another development manager employed by Investa, approved the sale price of Lot 191 to Spencer Projects as trustee for the Spencer Trust in the amount of $290,000. The relevant contract was executed on 25 June 2010 and the contract settled on 28 July 2010. At no time did Mr Nankervis disclose to Investa Properties or Investa Residential that Spencer Projects was owned and controlled by Mr Barclay's wife.

In respect of Lot 191, Mr Nankervis was in breach of s 182 and s 183 of the Corporations Act because, inter alia, he improperly used his position as an employee to gain an advantage for himself, or for Mr Barclay, or for companies controlled by Mr Barclay's wife in that, in the course of his duties, he obtained information including as to the potential subdivision of Lot 191, the identity of the company which had a Deed of Put and Call, and the ownership and control of Spencer Projects.

By letter of 16 July 2008, and/or by email of 27 November 2008, Mr Nankervis, acting for either Investa Properties or Investa Residential (or both of them), offered Oliver Hume SEQ the commission for the en globo sale of Lot 170. Thereafter Oliver Hume SEQ, in particular through Mr Barclay, performed numerous services in connection with the sale and marketing of Lot 170, including weekly reports provided by Mr Barclay at the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009.

On or about 22 July 2008, Ipswich City council conditionally approved an application made on behalf of Investa Properties and Investa Residential to reconfigure Lot 170 from one lot into 77 lots, and provided preliminary approval for building works to be carried out, subject to development permits in respect of any operational works being received before such works were commenced. An application was made on behalf of Investa Properties and Investa Residential on or about 11 August 2008, to obtain further development permits in respect of operational road works.

Some time before 26 November 2008, Investa Residential had entered into a contract to sell Lot 170 to Brittains Road Pty Ltd. It was apparent from the beginning of November 2008 however, that Brittains Road Pty Ltd would probably not complete the contract.

By letter of 26 November 2008 to Mr Barclay, Citimark Properties Pty Ltd ("Citimark") offered to purchase the Fossil Site for $3.7 million ("the Citimark offer").

The contract between Investa Residential and Brittains Road Pty Ltd terminated on or about 30 January 2009.

On or about 5 November 2008, CB Richard Ellis prepared a valuation report for ANZ Banking Group in respect of Lot 170, valuing it at $4 million exclusive of GST ("the CB Richard Ellis report"). A copy of this report was received by Mr Nankervis on 16 December 2008.

The CB Richard Ellis report described Lot 170 as follows:

Moderately sloping site subject to a Difficult Topography Overlay with approximately 14% of the site sloping between 20% and 25% along the eastern boundary.

Requirement for substantial retaining wall works.

Majority of lots on the eastern side of the state [sic] will require benching and a split level house design.

On or about 16 December 2008, Mr Nankervis met with Mr Daryl Walker, director of Projex North Pty Ltd ("Projex North") to discuss the redesign of Lot 170. On the same date, Mr Walker provided Mr Nankervis initial engineering advice in relation to the redesign of Lot 170, and Mr Nankervis emailed that engineering advice to Mr Barclay and Mr Tonuri. On or about 16 December 2008, Mr Nankervis received a letter from Mr Walker containing a design amendment proposal, which relevantly provided:

Assessment of the existing design with Mr Ashley Nankervis revealed that a design which provided significantly flatter allotments could be achieved by adjusting the levels of Road 2 and Road 3.

From about December 2008, Mr Nankervis was involved in submitting an amended Operational Roads Works Approval to the Ipswich City Council which sought levelling and retaining of Lot 170 to create flat lots.

At a time unknown to Investa Properties and Investa Residential, but before 20 January 2009, an agreement was entered between Messrs Nankervis, Barclay and Tonuri, pursuant to which Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay would participate in and derive profits from the sale to Mr Tonuri, or his nominee and the subsequent development of Lot 170.

On or about 6 February 2009, Mr Nankervis prepared a Delegated Authority Approval proposing the sale price for Lot 170 in the amount of $1,454,545 exclusive of GST. This recommendation was on the basis that:

The site is irregular in shape and heavily vegetated with steep topography, rising from the southeast to the northwest and is unattractive to our target market as only speciality [sic] custom built housing can be built on the site. The housing product made to accommodate steep slope of 10% to 15%. No slap on ground product will be achieved and this is compounded by the tree retention Council require and also approval limitations in association with the degree of earthworks allowed on the site, there is no ability to level the site.

The price of $1,454,545 did not reflect the potential market value of Lot 170, taking into account the CB Richard Ellis report, the design amendment proposal of Projex North, and the amended Operational Road Works Approval Application to the Ipswich City Council. It is also clear that, in light of the proposed works in respect of Lot 170, statements in Mr Nankervis' Delegated Authority Approval submission concerning:

(a) "only speciality custom built housing can be built on the site";

(b) "the housing product needs to accommodate steep slope of 10% to 15%";

(c) "no slap on ground product will be achieved"; and

(d) "there is no ability to level the site";

were incorrect.

On or about 10 February 2009, Investa Properties and Investa Residential approved the sale of Lot 170 at $1,454,545.

On or about 20 February 2009, Investa Residential and Two Eight Two Nine entered into a Deed of Put and Call in respect of Lot 170, for the sum of $1,454,545.

On a date prior to 4 March 2009, Mr Nankervis commissioned Projex North to assess the design for Lot 170, and on 6 March 2009, Mr Walker emailed Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay an engineering report for Lot 170, dated 12 January 2009, and slope analysis plans prepared by Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd ("Hyder Consulting").

On 25 June 2009, Investa Residential entered into a contract for the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine for $1,454,545. The contract was completed on 31 July 2009.

At a time when Mr Nankervis was an employee of Investa Properties, he was engaged by or performed services and duties for and on behalf of Mr Tonuri/Two Eight Two Nine, and provided information to him/it. This included:

(a) preparing financial and feasibility reports;

(b) project management including managing project negotiations;

(c) managing land sales, including tracking land sales on a periodic basis;

(d) managing project negotiations, preparing contracts and liaising with and appointing contractors and planners; and

(e) approving and/or recommending sales prices for lots.

A sales office owned by Investa Residential was located on the Brentwood Site, however in or around March 2010, it was removed and relocated to the site of a project owned by Mr Tonuri. This was done without the authorisation of Investa Properties or Investa Residential. The cost of replacing the sales office is approximately $100,000.

Mr Nankervis breached his fiduciary obligations to Investa Properties and Investa Residential and his statutory obligations under s 182 and s 183 of the Corporations Act in that he:

(a) entered into the agreement with Mr Barclay and Mr Tonuri in respect of Lot 170;

(b) made incorrect statements to Investa Properties in relation to Lot 170;

(c) recommended a sale price of $1,454,545 without taking into account or disclosing to Investa Properties or Investa Residential factors which meant the site was not as difficult to develop as he claimed;

(d) provided services to Mr Tonuri and Two Eight Two Nine; and

(e) relocated and decommissioned a sales office.

As against Mr Barclay

34 In the amended application the applicants plead:

2. As against the second respondent, Adam Kimberly Barclay:

2.1. In respect of Lot 191:

(a) Mr Barclay must account as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Residential Group for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

(b) Alternatively, Mr Barclay must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Residential for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

2.2. In respect of Lot 170:

(a) At the election of Investa Properties or Investa Residential or both of them, Mr Barclay must account as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties or Investa Residential or both of them for either:

(i) any profit that he or any entity that was associated with him, or that he controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine Pty Ltd, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or

(ii) the value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $3,000,000, but Investa Residential Group received only $1,454,545.

(b) Alternatively, Mr Barclay must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

35 In the amended statement of claim, the applicants plead further, in summary:

By reason of the arrangements entered into between Investa Residential on the one hand, and Oliver Hume SEQ on the other, and in circumstances where Mr Barclay had been the instrument of Oliver Hume SEQ in respect of the entry into those agreements, Mr Barclay had fiduciary obligations to Investa Residential while providing real estate services in relation to Lot 191. Those duties included an obligation not to assist any associated person or entity purchase Lot 191 without full disclosure to and the informed consent of Investa Residential.

From at least 19 October 2009 to 29 October 2009, Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay were involved in taking steps to subdivide Lot 191 into two lots.

When a Deed of Put and Call in respect of Lot 191 was executed by Queensland Property Centre, Mr Barclay did not disclose to Investa Residential or Investa Properties that, in effect, the sole director and sole shareholder of that company was his wife, Mrs Barclay.

At no time did Mr Barclay disclose to Investa Properties or Investa Residential that Spencer Projects was owned and controlled by his wife.

Mr Barclay had fiduciary obligations to Investa Properties and Investa Residential in relation to Lot 170, in that he was employed to perform Oliver Hume SEQ's obligations as real estate agent and was involved in a significant way in providing Oliver Hume SEQ's services to Investa Properties and Investa Residential.

Mr Barclay had a fiduciary obligation to Investa Properties and Investa Residential to tell them that Citimark had made an offer on 26 November 2008 in respect of Lot 170, and the details of the offer (in particular that the offer to purchase was for the amount of $3.7 million).

At a time when Mr Barclay was employed by Oliver Hume SEQ and providing services to Investa Properties and Investa Residential in respect of the marketing and sale of Lot 170, he was engaged by or performed services and duties for and on behalf of Mr Tonuri/Two Eight Two Nine, and provided information to him/it. This included:

(a) preparing financial and feasibility reports;

(b) project management including managing project negotiations;

(c) managing land sales, including tracking land sales on a periodic basis;

(d) managing project negotiations, preparing contracts and liaising with and appointing contractors and planners; and

(e) approving and/or recommending sales prices for lots.

Mr Barclay breached his fiduciary obligations to Investa by entering into the agreement with Mr Nankervis and Mr Tonuri in relation to Lot 170 and providing services to Mr Tonuri and/or Two Eight Two Nine.

As against Oliver Hume SEQ

36 In the amended application, the applicants plead:

3. Oliver Hume SEQ

3.1. In respect of Lot 191:

(a) Oliver Hume SEQ must account as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Residential for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

(b) Alternatively, Oliver Hume SEQ must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Residential Group for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

3.2. In respect of Lot 170:

(a) At the election of Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them, Oliver Hume SEQ must account as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them for either:

(i) any profit that it or any entity that was associated with it, or that it controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine Pty Ltd, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or

(ii) the value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $3,000,000, but Investa Residential received only $1,454,545.

(b) Alternatively, Oliver Hume SEQ must give equitable compensation, in such form and in such amount as the Court in its discretion considers just, to Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them, for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

37 In the amended statement of claim, the applicants plead further, in summary:

On or about 1 October 2008, Investa Residential entered into an agreement with Oliver Hume SEQ, being an Appointment of Real Estate Agent – Sales and Purchases (Form 22a) pursuant to PAMDA.

Mr Barclay, on behalf of Oliver Hume SEQ, signed a further agreement on or about 16 July 2009 with Investa Residential called "Appointment of Real Estate Agent – Sales and Purchases (Form 22a) pursuant to PAMDA. That agreement contained the following notice:

When performing this service, the agent must comply with the code of conduct for agents as set out in the Property Agents and Motor Dealers (Real Estate Agency Practice Code of Conduct) Regulation 2001 (Qld).

The terms of this notice were incorporated into the agreement as a contractual term. It followed that the agreement of 16 July 2009 contained an express term to the effect that, when performing the services that the agreement provided for, Oliver Hume SEQ must comply with the code of conduct for agents as set out in PAMDA (amended statement of claim para 102G).

In those agreements, Investa Residential appointed Oliver Hume SEQ as real estate agent in connection with the sales and marketing of the development of the Brentwood site.

At material times, Mr Barclay was a director and employee of Oliver Hume SEQ, and was its agent with actual or ostensible authority act for it in relation to providing real estate agent services to Investa Residential. Mr Barclay was also the signatory on behalf of Oliver Hume SEQ in relation to the agreements, the individual in charge of its business and the individual who dealt with the people at Investa Properties in relation to development and sale of land. In particular, Mr Barclay reported to Mr Nankervis and Mr Long.

Oliver Hume SEQ did not disclose to Investa Residential or Investa Properties that Lot 191 was the subject of a Deed of Put and Call in favour of Queensland Property Centre, a company controlled by Mr Barclay's wife, or that Lot 191 was sold to Spencer Projects, being another company controlled by Mr Barclay's wife. In this respect, Oliver Hume SEQ did not act with good faith, breached fiduciary obligations to Investa, and breached express and implied terms of its agreements with Investa.

Oliver Hume SEQ had fiduciary obligations to Investa Properties and Investa Residential while providing services in relation to Lot 170.

Oliver Hume SEQ had a fiduciary obligation to Investa Properties and Investa Residential to tell them that Citimark had made an offer on 26 November 2008 in respect of Lot 170, and the details of the offer (in particular that the offer to purchase was for the amount of $3.7 million).

Oliver Hume SEQ breached its fiduciary obligation to Investa Properties and Investa Residential in relation to Lot 170, as a result of Mr Barclay entering into the agreement with Mr Nankervis and Mr Tonuri in relation to Lot 170 and providing services to Mr Tonuri and/or Two Eight Two Nine.

Remedies claimed against the respondents

38 The remedies claimed by the applicants against the respondents can be summarised as follows.

Mr Nankervis

39 In respect of Lot 191:

account by Mr Nankervis as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties and Investa Residential for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale, on the basis that the value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

alternatively, compensation payable to Investa Properties pursuant to s 1317H of the Corporations Act.

40 In respect of Lot 170:

At the election of Investa Properties or Investa Residential, or both of them, Mr Nankervis must account as a defaulting fiduciary to either or both applicants for either:

o any profit he or any entity that was associated with him or that he controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or

o the value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $4 million, but Investa Residential received only $1,454,545.

Alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

Alternative, compensation payable to Investa Properties pursuant to s 1317H of the Corporations Act.

Equitable compensation for the decommissioning and relocation of the sales office.

Mr Barclay

41 In respect of Lot 191:

Account by Mr Barclay as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties and Investa Residential for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale, on the basis that the value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

Alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

42 In respect of Lot 170:

At the election of Investa Properties, or Investa Residential, or both of them, Mr Barclay must account as a defaulting fiduciary to either or both applicants for either:

o any profit he or any entity that was associated with him or that he controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or

o the value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $4 million, but Investa Residential received only $1,454,545.

Alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

Oliver Hume SEQ

43 In respect of Lot 191:

Account by Oliver Hume SEQ as a defaulting fiduciary to Investa Properties and Investa Residential for the value of Lot 191 at the time of sale, on the basis that the value of the property was $290,000, but Investa Residential received only $195,000.

Alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 191 at an undervalue.

44 In respect of Lot 170:

At the election of Investa Properties, or Investa Residential, or both of them, Oliver Hume SEQ must account as a defaulting fiduciary to either or both applicants for either:

o any profit it or any entity that was associated with it or that it controlled, made or derived from the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine, or from the development or resale of Lot 170; or

o the value of Lot 170 at the time of sale. The value of the property was $4 million, but Investa Residential received only $1,454,545.

Alternatively, equitable compensation for the sale of Lot 170 at an undervalue.

DEFENCES OF THE RESPONDENTS

45 The defences of the respondents to the claims of the applicants can be summarised as follows.

Mr Nankervis

46 Mr Nankervis relied on a second amended defence filed on 15 November 2013.

47 In summary, Mr Nankervis says as follows:

The description of his duties during the period of his employment in paragraph 5 of the amended statement of claim is incorrect.

He did not owe to Investa Properties and Investa Residential the fiduciary obligations in paragraph 16(a) of the amended statement of claim.

He denied that he was responsible for signing off on all relevant stage releases in the Brentwood site (amended statement of claim para 19(b), second amended defence para 12(c)).

He admitted that he signed the approval submission in respect of the Delegated Authority Approval proposing Lot 191 be sold for the amount of $210,000 (after rebate), but otherwise says that it was actually prepared by the development manager, Mr Long, and reviewed and revised by the Chief Financial Officer and the Group Executive before he signed it (second amended defence para 60).

He denied that he was involved in taking steps to subdivide Lot 191 into two lots as alleged in paragraphs 103(a) and 104 of the amended statement of claim.

He denied the allegation at paragraph 110 of the amended statement of claim that he had approved the sale price in respect of a Deed of Put and Call for Lot 191 to Queensland Property Centre in the amount of $195,000. Rather, at paragraphs 68(c) and 69(d) of his second amended defence, Mr Nankervis said that:

o the Sales Advice Vacant Land (referred to in the particulars) was a summary of the deed of Put and Call Option proposed to be entered into in respect of five lots in Brentwood Stages 2A and 2B;

o the document was prepared by the sales agent for the Brentwood Development;

o the proposed sale of five lots to Queensland Property Centre was a bulk sale;

o during the Global Financial Crisis, and especially during 2009, the applicants were willing to discount prices significantly to achieve bulk sales;

o the bulk sales of lots in Brentwood Stage 2A included pre-sales to Garrick Bull, DHA, Broadsword and Queensland Lifestyle Company, which are referred to in the "Contract Status Report" attached to the Approval Submission for Brentwood Stage 2A;

o discounted pricing for bulk sales was approved by the Board or the Project Control Group for the Brentwood site; and

o lot 191 was subsequently sold by Investa Residential for $290,000, well in excess of the approved net price of $210,000.

He did not know that Mr Barclay had the interest alleged by the applicants in Lot 191 arising from the Deed of Put and Call, and in any event, was not under a duty to disclose this fact to the applicants.

He had no knowledge of Spencer Projects which was not incorporated until 10 June 2010, and in any event ceased his employment with Investa Properties on 26 May 2010.

In relation to the allegations of the applicants concerning the CB Richard Ellis report prepared for ANZ Banking Group in respect of Lot 170, at paragraph 105(b) of his second amended defence, Mr Nankervis says:

o a valuation report had been prepared for the applicants by Jones Lang Lasalle, in or about June 2008, which provided an indicative assessment in the range of $2.1 million to $2.3 million;

o in or about early July 2008, after taking this valuation into consideration, the Group Executive approved disposal of Lot 170 under a "wholesale sell off" with a minimum sale price of $1.8 million with the objective of achieving a sale of the property by 31 December 2008;

o in or about early August 2008, the Group Executive approved a reduction in the minimum sale price to $1.75 million;

o in or about August 2008, the second applicant entered into a contract for sale of Lot 170 with Brittains Road Pty Ltd for $1,613,636 (excluding GST);

o the CB Richard Ellis report was prepared for the ANZ Banking Group Ltd based upon instructions, inputs and assumptions provided by Brittains Road Pty Ltd;

o on or shortly after 16 December 2008, Mr Nankervis went through the costings in the CB Richard Ellis report with Ms Nicole Prout, the applicants' Project Accountant in Queensland, and they considered that the costings were unrealistic;

o at or about the same time Mr Nankervis also received a copy of the CB Richard Ellis report from Mr Waters, who had been the Queensland General Manager until in or about November 2008 (when he was appointed Queensland Manager of Clarendon Homes) and he continued to have responsibility for the contract with Brittains Road Pty Ltd with Mr Stubbs, the new Queensland General Manager; and

o Mr Nankervis discussed the CB Richard Ellis report with Mr Waters and they were both of the opinion that it was overly optimistic in its assumptions given the market conditions.

In relation to the allegations of the applicants at paragraphs 169-173 of the amended statement of claim concerning Mr Nankervis' meeting with Mr Walker on or about 16 December 2008 to discuss the redesign of Lot 170, and Mr Nankervis' interactions with Mr Tonuri, he says at paragraph 106 of his second amended defence:

o in late 2008 and 2009 during the Global Financial Crisis, the Investa Property Group was under intense financial pressure and was attempting to sell assets wherever possible;

o in or about November 2008 it was apparent to Mr Waters and Mr Stubbs that the contract with Brittains Road Pty Ltd was unlikely to complete;

o during the period from in or about November 2008 to in or about February 2009, Mr Stubbs instructed Mr Nankervis to the effect that he should do anything and everything he could to ensure that a sale of Lot 170 was achieved;

o during November and December 2008, Mr Stubbs, Mr Long and Mr Nankervis undertook an extensive off-market campaign to find a buyer for Lot 170;

o the only sale that achievable at the times was the sale to Two Eight Two Nine for $1.6 million (including GST).

In relation to the allegations of the applicants at paragraph 174 of the amended statement of claim concerning Mr Nankervis' involvement in submitting an amended Operational Roads Work Approval to the Ipswich City Council which sought levelling and retaining of Lot 170 to create flat lots, he says at paragraph 107 of his second amended defence:

o he was involved in submitting a request for amendment of the development approval for reconfiguring one lot into 77 lots in respect of Lot 170;

o the principal purpose of the request was to address road design to meet safety concerns raised by the Ipswich City Council and compliance with the Council's Master Plan for the Brentwood Site on interface issues;

o the levelling and retaining of the site to create flatter lots was incidental but necessary to make Lot 170 more saleable;

o the person who was most interested in purchasing Lot 170 was Mr Tonuri, who told Mr Nankervis in or about November 2008 that he wanted a permit that was unconditional. The plan amendments were undertaken to obtain a permit that was unconditional;

o design changes to allow for flatter allotments were undertaken to satisfy Mr Tonuri's concern about the saleability of steep allotments;

o all of this information was known to Mr Stubbs because of his direct involvement in the marketing campaign for Lot 170 and in negotiations with Mr Tonuri, and the progress of plan amendments were reported to the Project Control Group.

In relation to allegations of the applicants at paragraph 176 of the amended statement of claim concerning the basis of Mr Nankervis' recommendation that Lot 170 be sold for $1,454,545, Mr Nankervis says at paragraph 109 of his second amended defence that he basis of the recommendation that Lot 170 be sold at that price was:

o the comparative price analysis undertaken by Jones Lang LaSalle;

o the need of Investa Properties to achieve a sale to gain revenue;

o the sale to Two Eight Two Nine was the only achievable sale at the time; and

o the proposed sale price was just below the price previously agreed by Investa Residential to sell to Brittains Road Pty Ltd and the Jones Lang LaSalle valuation obtained by Investa Residential in June 2008.

In relation to allegations of the applicants at paragraphs 186 and 187 of the amended statement of claim to the effect that Mr Nankervis was engaged by or provided services for and on behalf of Mr Tonuri or provided information to Mr Tonuri or a person or persons associated with Two Eight Two Nine, Mr Nankervis says at paragraphs 114-116 of his second amended defence that:

o Mr Tonuri worked for a bank and was not experienced in property development;

o Mr Tonuri told Mr Nankervis in early 2009 that he would need help in getting the right consultants and getting the Lot 170 project up and running, and Mr Nankervis said that he would assist Mr Tonuri if Mr Tonuri purchased Lot 170;

o Mr Nankervis was motivated to do so in order to achieve the sale, and because it was in the interests of Investa Residential for him to be involved so as to most effectively resolve the interface issues between Lot 170 and the balance of the Brentwood site and requirements of the Brentwood Master Plan, including sewer alignment, pathway connections and the road frontage works;

o he did not provide services alleged by the applicants including preparation of financial and feasibility reports, project management, land sales management and project negotiation management – rather the assistance Mr Nankervis provided to Mr Tonuri was that:

• he provided introductions to consultants and contractors;

• he attended a meeting between Mr Tonuri and a finance broker;

• he ran a feasibility model using inputs provided by Mr Tonuri; and

• the project was managed by Projex North which was engaged by Two Eight Two Nine;

o the assistance he provided to Mr Tonuri was generally given outside business hours in return for no payment, and did not conflict with his responsibilities to Investa Properties.

In relation to allegations of the applicants at paragraphs 191-193 of the amended statement of claim concerning the sales office, Mr Nankervis says at paragraphs 119-122 of his second amended defence that:

o by late 2009, when Investa Residential was pre-selling and preparing for the delivery of Stages 1D, 1E and 1F of the Brentwood site, the relevant sales office had not been used for approximately two years, had been vandalised and was in disrepair. The estimated cost of repairing and removing the sales office from the site exceeded $50,000.

o in or about December 2009, Mr Holt, the Queensland General Manager, instructed that the sales office was to be removed from the site at no cost to Investa Residential. Subsequently, in or about January or February 2010, Mr Barclay proposed to Mr Nankervis that the sales office be relocated to the Outlook Project at no cost to Investa, and Mr Nankervis agreed.

He did not profit from transactions involving either Lot 191 or Lot 170.

Mr Barclay

48 Mr Barclay relies on a defence filed on 18 November 2013. In summary, he says as follows:

Investa Properties was the relevant party at all times, not Investa Properties. At paragraph 1A(c)(ii) of his defence, Mr Barclay says:

(i) the land the subject of this proceeding was not held beneficially by Investa Residential for Investa Properties;

(ii) if funds were provided by Investa Properties to Investa Residential those funds were by way of a loan on commercial terms; and

(iii) Investa Residential was the registered owner of the subject land from any beneficial holding and was the party who contracted with real estate agents and entered into land contracts.

Further at paragraph 1B(a) of his defence, Mr Barclay says that it was Investa Residential which contracted for the purchase and sale of land within the Brentwood site, and the entity which entered into agreements with real estate agents.

In relation to the allegations of the applicants at paragraph 27 of the amended statement of claim concerning the appointment of Oliver Hume SEQ as real estate agent by Investa Residential, Mr Barclay admits that Oliver Hume SEQ agreed to conduct sales and marketing of certain lots but says further at paragraph 8 of his defence that:

o the applicants acted on their own behalf for the sale of all land at the Brentwood Site as well as negotiated or dealt with at least 10 different agencies involving more than 100 different purchasers;

o no agent was appointed for the sale of Lot 170; and

o unless an appointment is in the approved form 22a pursuant to PAMDA an appointment is ineffective.

The claim of the applicants in paragraph 102G of the amended statement of claim, that the notice on the agreement entered by the applicants and Oliver Hume SEQ on 26 July 2009 meant that there was incorporated a condition that the agent must comply with the code of conduct for agents in PAMDA, was wrong in law.

Neither he nor Oliver Hume SEQ owed obligations to Investa Residential pursuant to the provisions of PAMDA.

In relation to the claims of the applicants in paragraph 102L of the amended statement of claim that Mr Barclay owed fiduciary obligations to Investa Residential, Mr Barclay denies that such fiduciary obligations are owed.

In relation to the claim of the applicants at paragraph 107 of the amended statement of claim that he did not, at any time prior to Mr Nankervis recommending to Investa Properties the sale of Lot 191 at $210,000 (after rebate), disclose to the applicants that he was taking steps to subdivide Lot 191, Mr Barclay says at paragraph 34 of his defence that:

o he verbally informed the applicants through Mr Nankervis, who consented to and encouraged the sale;

o by email on or about 19 October 2009, Mr Barclay emailed the applicants asking whether or not there would be any issues with subdividing Lot 191, and the applicants (through Mr Nankervis) consented and encouraged the sale; and

o Mr Barclay initiated the proposal to the applicants for them to subdivide the larger lots in stage 2A and 2B of the Brentwood Site to achieve lower priced lots for sale during the Global Financial Crisis, however the applicants responded, inter alia, that they did not have the budget allowance or cash resources to carry out the subdivisions and they needed to increase cash flow by sales of existing lots.

In relation to the claim of the applicants in paragraph 108 of the amended statement of claim that the price of $210,000 for Lot 191 did not reflect its potential market value (given that it could be subdivided), Mr Barclay says at paragraph 35 of his defence that:

o the actual price paid was the market value of Lot 191 with or without the knowledge of the potential to subdivide;

o the applicants were informed of the potential to subdivide Lot 191 but declined the opportunity to do so;

o the Global Financial Crisis resulted in the applicants deciding to sell the Brentwood Site as a whole and there being less demand for larger lots;

o the applicants breached s 93 of the Valuation of Land Act 1944 (Qld) and s 81 of the Land Titles Act 1994 (Qld) by not disclosing rebates and therefore distorting the real market value of lots in the Brentwood Site and the surrounding area;

o the applicants failed to comply with regs 7(1), 11, 14 and 16 of the Property Agents and Motor Dealers (Property Developer Practice Code of Conduct) Regulations 2001 (Qld) by, inter alia, conduct whereby board list prices and list prices were artificially and misleadingly distorted, because of rebates given by the applicants in respect of lots sold;

o the applicants sold other lots greater than 900 m to their own employees at similar prices;

o Lot 190 was valued by Bank of Queensland on 2 August 2010 at $200,000 being the best comparative sale;

o in Delegated Authority Approval papers of the applicants dated 3 March 2009 the applicants authorised lots to be sold at an average of $190,000 per lot;

o market conditions were deteriorating in 2009 as a result of the Global Financial Crisis, and were affecting nearby developments operated by Stockland as well as sales rates of the Brentwood Site; and

o subdivision of Lot 191 required complex steps and associated costs.

In relation to the claim of the applicants in paragraph 111 of the amended statement of claim that the price of $195,000 for Lot 191 approved by Mr Nankervis on or about 18 December 2009 in the Deed of Put and Call was $15,000 less than the price of $210,000 approved by Investa Properties on 23 October 2009, Mr Barclay says that $195,000 was the market price, Lot 191 was sold as part of a bulk sale of other lots, the sale price of $195,000 was approved by the applicants and in any event the prices of Investa land were distorted by the applicants as a result of rebates which were not disclosed to the market.

In relation to the claim of the applicants at paragraph 120 of the amended statement of claim that Mr Barclay did not disclose to the applicants that the other party to the Deed of Put and Call was a company controlled by his wife, Mr Barclay says at paragraph 46 of his defence that he verbally informed Mr Nankervis of this fact and that Mr Nankervis encouraged these actions.

In relation to the sale price of $290,000 achieved for the sale of Lot 191 to Spencer Projects, Mr Barclay at paragraph 58 of his defence, says that the real value of Lot 191 was not $290,000, and the only reason Investa Residential achieved that sale price was because the transaction between Spencer Projects and Queensland Property Centre was a related party transaction.

In relation to the allegations of the applicants at paragraphs 162A-162G of the amended statement of claim concerning Lot 170, Mr Barclay says at paragraph 60 (inter alia):

o he undertook no activities set out in a letter of 16 July 2008 whereby Investa Residential offered Oliver Hume SEQ the commission for the en globo sale of Lot 170;

o as at 16 July 2008, Oliver Hume SEQ had not been appointed as the sales agent for any Lots within the Brentwood development;

o the applicants were actively marketing Lot 170 internally while at the same time contacting real estate agents including Oliver Hume SEQ to consider selling Lot 170;

o Brittains Road Pty Ltd was sourced as buyer internally from the marketing activities by the applicants;

o Mr Barclay undertook no marketing activities of Lot 170 on behalf of the applicants, or at all

o the email of 27 November 2008 from Mr Nankervis to Oliver Hume SEQ specifically stated that the applicants would not formalise the engagement of Oliver Hume SEQ until Oliver Hume SEQ advised. No agreement was ever formalised in fact or pursuant to PAMDA because there was no agreement to formalise;

o between 27 November 2008 and February 2009, Mr Barclay and Mr Nankervis (on behalf of the applicants) agreed that Oliver Hume SEQ would seek its commission from Two Eight Two Nine through the sales of the developed sites or vacant land sales of Lot 170 by Two Eight Two Nine. However, Oliver Hume SEQ did not receive any commission from the applicants for the sale of Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine in accordance with that agreement;

o in or about mid 2008, Mr Barclay on behalf of Oliver Hume SEQ was requested by Mr Geoff McWilliam, on behalf of Citimark, to source potential sites for development. In or about November 2008, Mr Barclay identified Lot 170 as such a site and Citimark made an offer on 26 November 2008 in respect of Lot 170, however the offer was withdrawn within several days; and

o the marketing report relied upon by the applicants in paragraph 162C of the amended statement of claim with reference to the Fossil Site was actually produced by Oliver Hume SEQ in relation to the Brentwood Site, and not Lot 170.

In relation to the offer of $1,454,545 for Lot 170, Mr Barclay says at paragraph 63 of his defence, inter alia, that at or about 10 February 2009 when the Delegated Authority Approval prepared by Mr Nankervis and signed by Mr Nankervis, Mr Stubbs (the General Manager Queensland) and Mr Jenkins (Group Executive), it was recognised that:

o the Brittains Road contract had terminated. In that contract Investa Residential had previously agreed to sell Lot 170 to Brittains Road Pty Ltd for $1,613,636 excluding GST;

o a sales and marketing campaign had been undertaken by Oliver Hume SEQ off market, at no cost to Investa;

o there was no interest in the site by corporate players and only five persons at a local level had been interested; and

o it was agreed that Oliver Hume SEQ would be acting on the buyer's behalf and not that of Investa Residential and would seek its commission from the buyer not the applicants.

He admits he provided services for and on behalf of Mr Tonuri and Two Eight Two Nine and provided information and assistance to them from August 2009.

In relation to the relocation of the sales office, at paragraph 85 of his defence, Mr Barclay denies that neither applicant authorised the relocation because Mr Nankervis agreed for it to be removed from the Brentwood site at Mr Barclay's cost. At paragraph 87 of his defence he denies that the applicants could have reused the sales office because:

o the applicants were using display homes for sales offices in subsequent stages in the Brentwood Development;

o the sales office was damaged and required extensive cash payments to improve;

o the sales office was not modern or presentable to a standard required by the applicants for their sales display;

o the applicants required increases in cash flow and saved cash flow by not having to refurbish a damaged sales office and keeping it in storage for subsequent use in subsequent stages of the Brentwood Development; and

o the applicants made the commercial decision to have the sales office removed at no cost, therefore saving approximately $50,000 in cash outlays.

Oliver Hume SEQ

49 Oliver Hume SEQ relies on a defence filed on 15 November 2013. In summary, it says as follows:

In respect of the claims of the applicants concerning the execution of contract for the sale of Lot 170, Oliver Hume SEQ says at paragraph 4 of its defence:

o an appointment of a person as a purported real estate agent is ineffective unless it is in the approved form in accordance with provisions of PAMDA, being Form 22a;

o a Form 22a was not executed by either applicants, or Mr Barclay, or Oliver Hume SEQ in relation to Lot 170; and

o this may be compared with the Form 22a prepared by Mr Barclay and executed by Investa Residential and Oliver Hume SEQ on 30 September 2008 in relation to other lots, and a subsequent Form 22a signed by Mr Nankervis on behalf of Investa Residential and Mr Barclay on behalf of Oliver Hume SEQ on 16 July 2009 in relation to Lots 173-215 and 216-249 Whipstick Boulevard in the Brentwood Development.

In relation to Mr Barclay, Oliver Hume SEQ says at paragraph 6 of its defence:

o Mr Barclay was employed on 15 March 2004 as Sales Manager, and his title changed to General Manager – Queensland Land and New Homes in September 2006;

o on 1 November 2006, Mr Barclay signed an employment contract, and subsequently on 27 August 2008 he signed another employment contract to become the General Manager – Queensland Land and New Homes for Oliver Hume SEQ. In both contracts he agreed, inter alia, that he would not engage in any private business activities or provide any commercial or professional services to a person or organisation without prior written consent of Oliver Hume SEQ;

o on 1 July 2009 AKB Qld Pty Ltd of which Mr Barclay was the sole shareholder and director became a shareholder of Oliver Hume SEQ, and was the only Queensland based shareholder of Oliver Hume SEQ at the material time;

o Mr Barclay was nominated as the officer in effective control of Oliver Hume SEQ's Corporate Licence from 2006;

o on 14 April 2011, Mr Barclay's employment with Oliver Hume SEQ was terminated and he was removed as a director;

o from 11 December 2007 to 14 April 2011 Mr Barclay was authorised by Oliver Hume SEQ to sign the following categories of documents on its behalf as the only director of Oliver Hume SEQ based in Queensland:

• PAMDA forms;

• lease agreements with a second director;

• capital expenditure up to $5,000;

• employment agreements for staff;

• consultancy agreements;

• all other agreements together with a second director; and

o other than in these respects, Mr Barclay had no actual or apparent authority to act for Oliver Hume SEQ in matters relating to the provision of real estate agent services to Investa Residential.

It denies that any agreement between it and either of the applicants contained terms imported by the notice on the Form 22a as claimed by the applicants. The contents of the Real Estate Agency Practice Code of Conduct were not terms or conditions of the contract.

It denies that any fiduciary obligation which consisted of the duties or obligations particularised at paragraphs 102J and 102L of the amended statement of claim arose as between either of the applicants and Oliver Hume SEQ.

At paragraph 22 of its defence, Oliver Hume SEQ says that it was to provide real estate agent services in accordance with the terms of the Form 22a signed on 16 July 2009 which included the sale and marketing of Lot 191, but that was all.

Oliver Hume SEQ had no knowledge concerning the entry into the Deed of Put and Call by Queensland Property Centre.

Oliver Hume SEQ had no knowledge of the steps taken by Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay to subdivide Lot 191 into two lots, and says at paragraph 41 of his defence that it that conduct was engaged in it was not undertaken with the knowledge, consent or approval of Oliver Hume SEQ. Such conduct or knowledge could not be imputed to Oliver Hume SEQ.

In relation to steps taken by Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay pursuant to the subdivision of Lot 191 pleaded by the applicants at paragraph 139 of the amended statement of claim, Oliver Hume SEQ, at paragraph 41 of its defence, denies that it breached any express or implied terms of any agreement and any fiduciary obligation.

It denies that there was any contract of engagement with the first or second applicant in relation to Lot 170 as pleaded in paragraph 162C of the amended statement of claim. Any services provided by Mr Barclay were not performed on behalf of, or with the authority of, or as agent for Oliver Hume SEQ.

It denies the claim of the applicants in paragraph 162D of the amended statement of claim that Oliver Hume SEQ was in a position of confidence in relation to Investa Properties and Investa Residential, and further denies the claims in paragraphs 162E and 162F of the amended statement of claim that it owed any fiduciary obligations in relation to Lot 170.

In relation to the claims of the applicants at paragraphs 164A-167 of the amended statement of claim, Oliver Hume SEQ says at paragraph 51 of his defence, inter alia:

o on 13 June 2008, after the preparation of an "Indicative Assessment" for the second applicant by Jones Lang LaSalle, the second applicant's business plan valued Lot 170 at $3,100,000;

o on 3 July 2008, however the State Manager of the second applicant recommended that Lot 170 be disposed of under a "wholesale sell off" with the minimum sale price to exceed $1,800,000. This recommendation was approved by Mr Maurice Felizzi, the Group Executive for the second applicant on or about 7 July 2008. That recommendation was followed up on 11 August 2008 with a further recommendation that Lot 170 be sold with the minimum price to exceed $1,750,000, which recommendation was again approved by Mr Felizzi;

o on 11 August 2008, the second applicant entered into a contract to sell Lot 170 to Brittains Road Pty Ltd for $1,775,000 (inclusive of GST). Oliver Hume SEQ was not identified in the contract as being the vendor's agent for the sale;

o on or about 19 August 2008, Mr Barclay sought a quotation from CB Richard Ellis to provide a report for Lot 170. CB Richard Ellis prepared a report, for the ANZ Banking Group, on the instruction of Brittains Road Pty Ltd, valuing the land at $4,000,000;

o by letter dated 26 November 2008 to Mr Barclay, Citimark offered to purchase Lot 170 for $3,700,000 including GST. Oliver Hume SEQ had no knowledge of this offer;

o on 27 November 2008 Mr Nankervis emailed Mr Barclay to the effect that the Brittains Road Pty Ltd contract looked precarious and that Investa Residential wanted Oliver Hume SEQ to procure a back-up sale contract for around $1,800,000, but would not formalise Oliver Hume SEQ's engagement until Mr Barclay advised them;

o by 2 December 2008 Mr Barclay had made contact with Mr Tonuri in relation to purchasing Lot 170;

o a further memorandum was prepared by Mr Nankervis to the Group Executive of Investa Residential on 28 January 2009 recommending that Lot 170 be sold for $1,600,000, followed by a Delegated Authority Approval Submission prepared by Mr Nankervis on 6 February 2009, recommending that it be sold under a "wholesale sell off" for $1,454,545 exclusive of GST;

o on 13 February 2009 Ms Prout, an employee of one of the Investa companies, wrote to Mr Andrew Murray (Legal Counsel of the Investa property group) and Mr Duncan Peacock (the Chief Financial Officer of the Investa Property Group) and stated, inter alia, that it appeared that the book value for Lot 170 was $2.976 million, and having regard to the loan amount referable to the site she had arrived at a debt of $1,361,923; and

o CB Richard Ellis prepared a report of Lot 170 on 6 May 2009 on the instructions of Mr Tonuri for mortgage security purposes, and CB Richard Ellis valued Lot 170 at $4 million.

The second applicant subsequently sold Lot 170 to Two Eight Two Nine for $1,454,545 on 25 June 2009 by a contract of sale, in which no selling agent was identified. Oliver Hume SEQ received no commission in relation to the sale of Lot 170.

Oliver Hume SEQ says at paragraph 64 of its defence that it provided no services to Mr Tonuri and/or Two Eight Two Nine.

At all material times, Mr Nankervis was the servant or agent of the applicants, and in so far as any loss was suffered by the applicants in respect of the Lot 191 contract or the Lot 170 contract it was caused by the applicants by their agent, Mr Nankervis.

RELEVANT ISSUES FOR DETERMINATION

50 At the commencement of the trial of these proceedings the parties estimated that a period less than three weeks of Court time would be required for the hearing. Despite the fact that, in my view, the questions before the Court for consideration and determination were broadly straightforward, the time allowed for the trial proved to be a significant underestimation. By the closure of the proceedings, approximately six weeks of Court time had been occupied in this matter, with the expectation that, in future, further directions will be necessary for submissions by the parties concerning compensation (if any) and costs.

51 One reason for the escalation was that both Mr Nankervis and Mr Barclay were self-represented throughout the trial, and it is clear that the conduct of a trial over multiple weeks proved challenging to them, and required considerable time over and above that which would have been required by experienced legal representatives in the conduct of their cases. In making this comment, I make no criticism of them in respect of their conduct of their cases.

52 However an additional, and in my view unfortunate, reason for the prolongation of the proceedings was that the trial was characterised at various times by an extraordinary degree of animosity between Counsel, and between certain Counsel and litigants in person. While such animosity inevitably translates into proceedings of heightened tension, a more problematic outcome is that the high standards of professional conduct and reasonable co-operation of litigants, which this Court has reasonably come to expect, was absent. Indeed there was almost nothing upon which the parties could agree, even the matters for determination by this Court on the filed pleadings.

53 A draft joint statement of issues for determination was provided by the applicants, with objection by Counsel for Oliver Hume SEQ. I note that it is Court document 261 in these proceedings. It was the subject of comment by Mr Barclay and Oliver Hume SEQ, but apparently no comment by Mr Nankervis. It is a document which is of some assistance as an aide to the Court, but little more.

54 In my view at this stage there are three key issues for determination in respect of the primary proceedings:

1. Did any of the respondents owe fiduciary, statutory or other duties to any of the applicants in respect of Lot 191, Lot 170 and/or the sales office?

2. If yes, did the conduct of any of the respondents breach those fiduciary, statutory or other duties?

3. If yes, what loss or damage is attributable to that breach of fiduciary or statutory duties in respect of Lot 191, Lot 170 and/or the sales office?

55 I now turn to consideration of these issues.

ISSUE 1: DID ANY OF THE RESPONDENTS OWE FIDUCIARY, STATUTORY OR OTHER DUTIES TO EITHER OF THE APPLICANTS IN RESPECT OF LOT 191, LOT 170 OR THE SALES OFFICE?

Did Mr Nankervis owe fiduciary duties to either of the applicants?

The applicants' submissions

56 The applicants, at paragraph 16 of their amended statement of claim, allege that:

16. By reason of the positions of Development Manager and Senior Development Manager held by Nankervis, and the responsibilities that he discharged, and the relationship between Investa Properties and Investa Residential as alleged in paragraphs 1A and 2 above, at all material times during his employment, Nankervis:

(a) had fiduciary obligations to Investa Properties and Investa Residential Group to:

(i) act in good faith and with fidelity;

(ii) avoid and disclose to Investa Properties or to Investa Residential Group all actual or perceived conflicts of interest;

(iii) act in the best interests of Investa Properties and Investa Residential Group; and

(iv) give Investa Properties and Investa Residential Group the full benefit of his knowledge and skill, and in particular, pass on to Investa Properties or to Investa Residential Group all information that he had about the marketing and sale of the properties that were the subject of his employment, that might be relevant to the marketing and sale;

(v) not profit from his position, other than by receiving remuneration in the course of his employment with Investa Properties, without full disclosure to and the informed consent of Investa Properties and Investa Residential Group; and

(vi) not assist

• any person with whom he was associated; or

• any entity in which he had an interest; or

• any person or entity from whom or from which he could expect a benefit;

to purchase any of the properties he was engaged in the marketing and sale of, without full disclosure to and the informed consent of Investa Properties and Investa Residential Group; and

(b) was an employee of Investa properties within the meaning of sections 182 and 183 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).