FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

BZAFI v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] FCA 771

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Appellant | |

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent REFUGEE REVIEW TRIBUNAL Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 JULY 2015 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The orders made by the Federal Circuit Court of Australia on 2 October 2014 are set aside.

3. A writ of certiorari issue directed to the second respondent, quashing its decision made on 16 July 2013.

4. A writ of mandamus issue directed to the second respondent, requiring the second respondent to determine the appellant’s application for review filed 18 December 2012 according to law.

5. The first respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal and the proceeding before the Federal Circuit Court of Australia.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 562 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | BZAFI Appellant |

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent REFUGEE REVIEW TRIBUNAL Second Respondent |

JUDGE: | RANGIAH J |

DATE: | 29 JULY 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 16 July 2013, the Refugee Review Tribunal (“the Tribunal”) affirmed a decision of a delegate of the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (“the Minister”) to refuse the appellant a Protection (Class XA) visa.

2 The appellant then applied to the Federal Circuit Court of Australia for the issue of constitutional writs directed to the Tribunal. On 2 October 2014 the primary judge dismissed the application. This is an appeal against that judgment.

3 The notice of appeal sets out three grounds of appeal, but only two are pressed. Those grounds are that the primary judge erred by failing to find that:

(a) the Tribunal had committed jurisdictional error by failing to consider relevant material, namely a document entitled “True extract from the Information Book of Negombo Police Station”;

(b) the Tribunal committed jurisdictional error by failing to consider claims or integers of claims made by the appellant that he feared serious harm on account of his membership of particular social groups consisting of:

(i) Tamils with familial links to persons suspected of associating with or supporting the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (“the LTTE”);

(ii) people who had departed Sri Lanka illegally and sought asylum.

4 For the reasons that follow, I consider that the appeal should be allowed on the first ground.

The Tribunal’s decision

5 The substance of the appellant’s application for a protection visa is that he fears persecution by the Sri Lankan authorities for reasons of his race, imputed political opinion and membership of particular social groups.

6 The appellant claims that in 2004, when he was at school, he was harassed and beaten up by Sinhalese thugs because he is Tamil. He also states that in 2007 he and his friends were detained by police overnight and accused of supporting the LTTE and that he was assaulted and sexually abused.

7 The appellant claims that he is wanted by police in Sri Lanka on suspicion of terrorist activity and that he fears that he will be detained and tortured. The appellant states that he was sharing a house in Negombo with a man who was detained by the police in January 2008 and accused of being a spy for the LTTE. The appellant and his cousin were given a message that they were to present themselves at the police station. The cousin presented himself and was detained. The appellant, fearing detention and torture, fled and went into hiding. The appellant says that his cousin and the other man are still in detention, apparently on the basis that they are suspected of involvement in a suicide bombing attack on a government minister.

8 The appellant claims that the police came to his family’s house in Negombo looking for him later in 2008. The appellant’s father was twice taken to the police station and questioned. The appellant’s father was told that he was being detained in place of his son.

9 The appellant claims that he received anonymous phone calls asking him about his knowledge of various people in the LTTE. The phone calls stopped after he changed his telephone number.

10 The appellant was able to obtain a passport in his own name and travel to India and back to Sri Lanka in 2010. In May 2012, the appellant travelled by boat to Australia.

11 In its reasons, the Tribunal indicated that it had significant concerns regarding the credibility of some aspects of the appellant’s claims. Despite its concerns, the Tribunal was prepared to accept that he had been harassed and discriminated against while he was a school student. The Tribunal found that the appellant’s claims in that regard did not amount to serious harm and was not “persecution” as defined in s 91R(1) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (“the Act”). The Tribunal accepted that the appellant was sexually abused, threatened and bashed by a police officer in 2007 and that this amounted to serious harm.

12 However, the Tribunal noted that the appellant’s claim to have a well-founded fear of persecution if he returns to Sri Lanka is based on his claim that he is wanted by the authorities and will be detained. In this regard, the Tribunal found:

81. The Tribunal accepts that the applicant’s cousin [name deleted] and his friend [name deleted] may have been detained in January 2008 on suspicion of assisting the LTTE. The Tribunal accepts that other members of [name deleted] extended family may also have been questioned. However the Tribunal does not accept that the Sri Lankan authorities continued to search for the applicant from January 2008 onwards and that he remains a person who they wish to question or detain or a person they will subject to serious harm if he returns to Sri Lanka.

13 The Tribunal reached this conclusion because it considered that the appellant’s claim that he is wanted by the police was not credible. The Tribunal reasoned that if the appellant was wanted by the police, he would not have been able to obtain a passport issued in his own name or have been able to travel to India. The Tribunal also reasoned that if he had received the threatening telephone calls as he claims, it is likely that the authorities would have been able to track him down. The Tribunal also considered that if he genuinely had a fear of serious harm, he would not have returned to Sri Lanka from India in 2010.

14 The Tribunal concluded:

95. After assessing all the evidence before it the Tribunal does not accept that the applicant is a person in whom the Sri Lankan authorities have an interest as they suspect him of being associated with the LTTE and associated with two people detained in connection with the killing of a Sri Lankan Government Minister in April 2008. This claim is central to the applicant’s claims of fearing serious harm for a Convention reason on return to Sri Lanka. As the Tribunal does not accept this claim, it follows that the Tribunal also does not accept that the authorities asked the applicant to attend the police station in January 2008; that his cousin is in jail and warned that the applicant was suspected of being connected with the LTTE and would be detained and tortured if captured; and that the authorities searched for the applicant everywhere and questioned relatives and friends about his whereabouts.

…

97. After assessing all the evidence the Tribunal finds that the applicant does not face serious harm because of imputed political opinion, or his Tamil ethnicity, or his membership of a particular social group in the reasonably foreseeable future in Sri Lanka. The Tribunal finds the applicant does not have a well-founded fear of persecution in Sri Lanka for a Convention reason and does not satisfy the refugee criterion at s.36(2)(a) of the Act.

15 The Tribunal also found that the appellant did not meet the complementary protection criterion in s 36(2)(aa) of the Act.

16 The focus of the first ground of the present appeal is on whether the Tribunal considered the document entitled “True extract from the Information Book of Negombo Police Station”. The Tribunal did refer to that document. It said:

67. Subsequent to the hearing the applicant’s representative provided a brief submission and the following documents: a letter in support of the applicant’s claim that his family is unable to return to the land they own in Jaffna; Extract from Information Book dated 3 June 2008 in support of claim that the applicant’s father was detained and questioned by the Sri Lankan authorities; letter from the applicant’s cousin [name deleted] dated 15 February 2009; letter from the Terrorism Investigation Unit and letters from the applicant’s former employers.

(Underlining added)

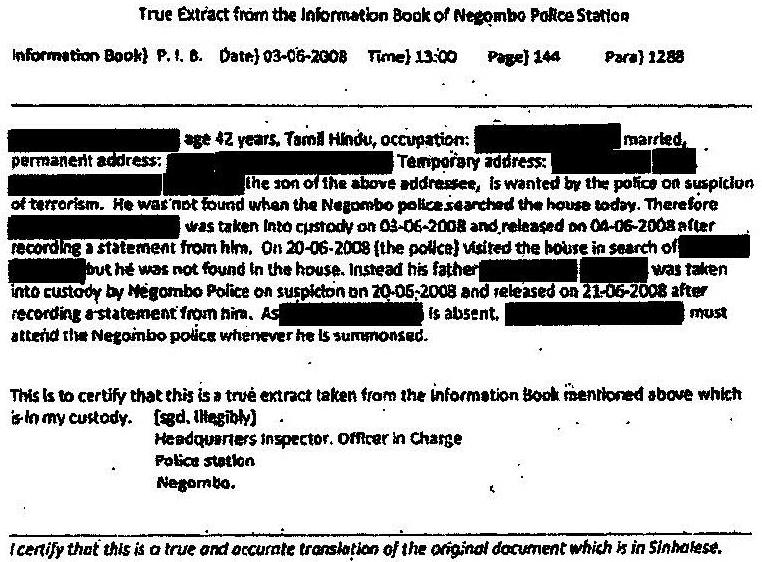

17 The English translation of the document in evidence is as follows:

18 The extract of the entry in the Information Book names the appellant and says he “is wanted by the police on suspicion of terrorism.” The extract also indicates that police had taken the appellant’s father into custody on two occasions when the appellant was not located at his father’s house. Apart from para [67], the Tribunal’s reasons do not contain any specific reference to the extract from the Information Book.

The application before the Federal Circuit Court

19 The first ground of the application before the Federal Circuit Court was essentially the same as the first ground relied on in this appeal, namely that the Tribunal had failed to consider the extract from the Information Book.

20 The primary judge concluded that the Tribunal had considered that document. His Honour noted that the Tribunal had expressly referred to the extract at para [67] of its reasons. His Honour then summarised the Tribunal’s findings on credit. His Honour continued:

37. By making those specific credit findings against the applicant – the Tribunal, in essence, dealt with the evidence/claim made by the applicant (and included as part of the Extract from the Information Book of the Negombo Police Station) – that the applicant “is wanted by the police on suspicion of terrorism”. Inherent in the credit findings made by the Tribunal is the conclusion that the Tribunal did not accept the authenticity of the “Extract” in question. If my own conclusion on that point is incorrect or unnecessary then I consider it makes no difference to my decision in this application. The applicant cannot circumvent the broad ranging credit findings made against him by the Tribunal. It is not permissible for this Court to review the merits of those credit findings.

(Emphasis in original)

21 The second ground before the primary judge was that the Tribunal had failed to consider a claim or integer of a claim made by the appellant, namely his claim to fear suffering serious harm on account of his membership of the social group consisting of Tamils with familial links to persons suspected of associating with or supporting the LTTE.

22 The primary judge held that the Tribunal was “plainly cognisant” that one of the appellant’s arguments was his claim founded on risks associated with being a Tamil with familial links to persons suspected of associating with the LTTE. His Honour indicated that this was a matter that had been dealt with in para [81] of the Tribunal’s reasons.

23 The primary judge also rejected two other grounds of the application. It is not asserted in this appeal that his Honour made any error in dealing with those grounds.

Consideration

The first ground: whether the Tribunal failed to deal with the extract from the Information Book

24 The appellant argued before the primary judge that the Tribunal had failed to consider the extract from the “Information Book of Negambo Police Station” that was placed before the Tribunal. That extract stated specifically that the appellant “is wanted by the police on suspicion of terrorism”. The primary judge considered that the Tribunal had dealt with this extract by referring to it and then making general findings adverse to the appellant’s credit. His Honour considered that “Inherent in the credit findings made by the Tribunal is the conclusion that the Tribunal did not accept the authenticity of the ‘Extract’ in question”. His Honour also concluded that if the Tribunal had failed to consider the extract from the Information Book, it would have made no difference to the Court’s decision because of the Tribunal’s adverse credit findings.

25 Two questions arise: firstly, whether the Tribunal failed to consider the extract from the Information Book; and secondly, whether any such failure amounts to jurisdictional error.

26 As to whether the Tribunal considered the extract from the Information Book, the Tribunal did refer to it at para [67] of its reasons. The only other possible reference to the extract is at para [87] where the Tribunal said it had “considered the documents submitted in support of the applicant’s claims”. However, the Tribunal went on to specifically analyse a number of documents, but did not mention the extract from the Information Book.

27 In Applicant WAEE v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs (2003) 75 ALD 630; [2003] FCAFC 184, the Full Court said at 641 [47]:

47 The inference that the Tribunal has failed to consider an issue may be drawn from its failure to expressly deal with that issue in its reasons. But that is an inference not too readily to be drawn where the reasons are otherwise comprehensive and the issue has at least been identified at some point. It may be that it is unnecessary to make a finding on a particular matter because it is subsumed in findings of greater generality or because there is a factual premise upon which a contention rests which has been rejected. Where however there is an issue raised by the evidence advanced on behalf of an applicant and contentions made by the applicant and that issue, if resolved one way, would be dispositive of the Tribunal’s review of the delegate’s decision, a failure to deal with it in the published reasons may raise a strong inference that it has been overlooked.

28 This passage is also applicable to the question of whether a piece of evidence has or has not been considered.

29 In Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v MZYTS (2013) 136 ALD 547; [2013] FCAFC 114, the Full Court said at 561 [49]:

49. The Court is entitled to take the reasons of the Tribunal as setting out the findings of fact the Tribunal itself considered material to its decision, and as reciting the evidence and other material which the Tribunal itself considered relevant to the findings it made: Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Yusuf (2001) 206 CLR 323 (Yusuf) at [10], [34], [68]. Representing as it does what the Tribunal itself considered important and material, what is present — and what is absent — from the reasons may in a given case enable a Court on review to find jurisdictional error: see Yusuf 206 CLR 323 at [10], [44], [69].

30 A central issue the Tribunal was required to deal with was whether the appellant was wanted by the police in Sri Lanka and, if so, for what reason. The extract from the Information Book was a significant document because, on its face, it was a clear statement from the police themselves that the appellant was wanted on suspicion of terrorism. In view of some of the appellant’s evidence about the ease with which he was able to obtain forged papers in Sri Lanka and ease with which officials are able to be bribed, the Tribunal was entitled to be suspicious of the extract. However, if the Tribunal found that the extract was not forged and was not obtained by bribery and contained a genuine account, it would have gone a long way towards the appellant establishing his claim.

31 The Tribunal did not make any specific finding as to whether the extract was genuine and whether its contents were true. In contrast, the Tribunal made specific findings about documents of much less significance, such as letters from employers and a letter from the appellant’s uncle.

32 In these circumstances, the absence of any specific analysis of the extract from the Information Book indicates that, beyond the existence of the extract being mentioned, it was overlooked: cf Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v MZYTS at 560 [41].

33 The primary judge’s view that it was inherent (or perhaps implicit) in the Tribunal’s credit findings that it did not accept the authenticity of the extract is not persuasive. The question of authenticity was so central to the Tribunal’s determination of the application that it would have been dealt with specifically if it had not been overlooked.

34 The Tribunal may not have realised the significance of the extract because the migration agent then representing the appellant did not alert the Tribunal to its precise significance. The migration agent sent the extract to the Tribunal after the hearing describing it as a “document in support of his statements that his father was detained and questioned by the Sri Lankan authorities”. Inexplicably, the migration agent did not describe the extract as supporting the claim that the appellant was wanted by the police. The fact that the migration agent overlooked the primary significance of the document makes it understandable that the Tribunal would also do so. However, the document was before the Tribunal and its significance to the question of whether the appellant was wanted by police was obvious.

35 The next question is whether the Tribunal fell into jurisdictional error by failing to consider the extract from the Information Book. The extract was a piece of evidence, not a claim or an integer of the claim.

36 In Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSRS (2014) 309 ALR 67; [2014] FCAFC 16, the Full Court at 78 [50] cited the following passages from the judgment of Robertson J in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZRKT (2013) 212 FCR 99; [2013] FCA 317 with approval:

[111] In my opinion there is no clear distinction in each case between claims and evidence: see SHKB v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2005] FCAFC 11 at [24]…The fundamental question must be the importance of the material to the exercise of the Tribunal’s function and thus the seriousness of any error. In my opinion the distinction between claims and evidence provides a tool of analysis but is not the discrimen itself. Further, it is important not to reason that because a failure to deal with some (insubstantial or inconsequential) evidence will, in some circumstances, not establish jurisdictional error, then a failure to deal with any (substantial and consequential) evidence will also not establish jurisdictional error.

[112] As the Full Court said in VAAD v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs at [77] whether the Tribunal is obliged to consider a document or documents will depend on the circumstances of the case and the nature of the document. In my opinion, the relevant factors in relation to (corroborative) evidence include first, the cogency of the evidentiary material and, second, the place of that material in the assessment of the applicant’s claims. To the extent that the Minister’s submissions involved the contention that it is always the case that these matters may be dealt with without reference to the Tribunal’s reasons I do not agree.

(See also Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v MZYTS at 566 [70])

37 Whether the Tribunal’s failure to consider the extract from the Information Book was jurisdictional error turns on its importance in the context of the application before the Tribunal. The Tribunal’s finding that the appellant was not wanted by the police meant that the core of his claim was rejected and he could not succeed. The extract was a significant piece of evidence. If the Tribunal accepted it as genuine and accepted its contents as being true, it would have established that he was wanted by the police, at least in 2008. I consider that the extract was of such central importance to the appellant’s application that the Tribunal fell into jurisdictional error by failing to consider it.

38 The primary judge found that even if the Tribunal had failed to consider the extract, that failure would make no difference to the outcome of the application before the Court. His Honour seems to have ruled that even if jurisdictional error were established, the Court’s discretion to grant relief would not be exercised in favour of the appellant because the Tribunal’s adverse findings as to the appellants’ credit meant that the error would not have affected the outcome of the Tribunal’s decision.

39 However, if the Tribunal had considered the extract, it is at least possible that it may have found the document to be genuine and not procured by bribery and that its contents were true. While it is possible that the matters which led the Tribunal to take an adverse view of the appellant’s credit may have influenced it to find that the document was not authentic, conversely it is possible that the document may have caused the Tribunal to consider those matters in a different light. It was not open to the Court to refuse relief in the exercise of its discretion in circumstances where the Tribunal’s jurisdictional error could possibly have deprived the appellant of a successful outcome: VAAD v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs [2005] FCAFC 117 at [83].

The second ground: whether the Tribunal failed to consider a claim or integer of a claim

40 The appellant argued before the primary judge that the Tribunal had committed jurisdictional error by failing to consider a claim or an integer of the claim made by the appellant, namely that he feared serious harm on account of his membership of a particular social group consisting of Tamils with familial links to persons suspected of associating with or supporting the LTTE.

41 In its reasons, the Tribunal noted the submissions made by the appellant’s migration agent:

40. The applicant’s representative provided a submission which argued that the applicant’s claims are consistent with known and reliable country information which indicates systematic and discriminatory targeting of persons with the applicant’s profile; that the essential and significant motivation for the harm feared by the applicant are the Convention grounds of race, imputed political opinion, and membership of particular social groups: Tamil failed asylum seekers who left the country illegally; young Tamil men suspected of supporting the LTTE; and Tamils with familial links to persons suspected of associating with the LTTE; and it is not reasonable or safe for the applicant to relocate in Sri Lanka.

(Underlining added)

42 The Tribunal accepted at para [81] that members of the appellant’s extended family may have been detained and questioned. However, the Tribunal did not accept that the Sri Lankan authorities had continued to search for the appellant and did not accept that he remained a person who the authorities wished to question or detain. Therefore, the Tribunal concluded that the appellant was not a person at risk of serious harm for any reason.

43 The appellant also sought to raise a ground that was not raised before the primary judge. It is that the Tribunal had failed to deal with his claim that he feared suffering serious harm because he belonged to a particular social group namely a group of people who departed Sri Lanka illegally and sought asylum.

44 The Tribunal did refer to this aspect of the appellant’s claim at para [40]. The Tribunal also referred to this issue at para [56] where it said:

The applicant stated that he fears that as he left Sri Lanka illegally he will not pass the airport without being arrested and questioned and checked.

45 The Tribunal at para [97] concluded that the appellant does not face serious harm as a result of “his membership of a particular social group in the reasonably foreseeable future in Sri Lanka.” This passage refers to each of the claims of membership of a particular social group that the Tribunal set out at para [40].

46 The Tribunal did consider the appellant’s claims to fear persecution by reason of membership of each of the particular social groups he nominated. I reject the appellant’s second ground that the Tribunal failed to deal with any of his claims or integers of his claims. The appellant has not demonstrated any error in this aspect of the primary judge’s reasoning.

Conclusion

47 The appellant has established the first ground of appeal. The Tribunal committed jurisdictional error by failing to consider an important piece of evidence, the extract from the Information Book. The primary judge erred by failing to find that the Tribunal had not committed jurisdictional error and by finding that, even if there was jurisdictional error, the Court’s discretion should not be exercised in favour of granting relief.

48 The appeal will be allowed and orders made setting aside the orders of the Federal Circuit Court, quashing the order of the Tribunal and requiring the Tribunal to determine the application according to law. The first respondent should pay the costs of the appeal and the proceeding in the Federal Circuit Court.

I certify that the preceding forty-eight (48) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Rangiah. |

Associate: