FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Konami Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 735

Counsel for the Applicant/Cross-Respondent: | |

Solicitor for the Applicant/Cross-Respondent: | Griffith Hack Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondent/Cross-Claimant: | Mr RJ Webb SC with Mr HPT Bevan |

Solicitor for the Respondent/Cross-Claimant: | Thomson Geer |

Table of Corrections | |

23 July 2015 | Para [35], fourth sentence: “a designated range” amended to “the designated range” |

Para [77], first sentence: the word “and” deleted so as to read “turnover between successive occurrences” | |

Para [103], second sentence: the words “will fulfil the trigger condition” amended to read “will trigger the feature outcome” | |

Para [116], second sentence: the word “discussed” amended to “disclosed” | |

Para [134], first sentence: “consists of” amended to “includes” | |

Para [180], first sentence: “and the amount wagered in the game” and the word “that” in the second sentence deleted | |

Para [232], last sentence: the number “689” deleted so as to read “a copy of the specification filed” |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 7 days the applicant file and serve a draft minute of the orders it seeks in light of the reasons for judgment.

2. The proceeding be stood over to a date to be fixed for the making of further orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1429 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | ARISTOCRAT TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 001 660 715) Applicant |

AND: | KONAMI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 076 298 158) Respondent |

AND BETWEEn: | KONAMI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 076 298 158) Cross-Claimant |

AND: | ARISTOCRAT TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 001 660 715) Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE: | 22 July 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding the applicant (“Aristocrat”) sues the respondent (“Konami”) for infringement of selected claims of three standard patents. Konami denies infringement. It says that if any of the products which it supplies that are alleged to infringe are within any claim properly construed, then that claim is invalid and should be revoked.

2 Each of the patents in suit relates to gaming machines or, as they are referred to in the patents, “slot machines”, “poker machines”, “gaming machines” and “gaming consoles” all of which expressions are used interchangeably. These are the machines usually found in hotels, clubs and other gaming venues. The three patents in suit are:

Australian patent number 754689 (“689”) entitled “Slot machine game and system with improved jackpot feature” with an asserted priority date of 8 July 1997. Aristocrat alleges that Konami has infringed claims 1 – 4, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 37, 38 (product claims), 43, 55 and 56 (method claims). Of these, claims 1, 25 and 43 are independent claims.

Australian patent number 766341 (“341”) also entitled “Slot machine game and system with improved jackpot feature” with an asserted priority date of 8 July 1997. The 341 patent is a divisional of the 689 patent. Aristocrat alleges that Konami has infringed claims 1, 11 and 12.

Australian patent number 771847 (“847”) entitled “Gaming machine with buy feature games” with an asserted priority date of 25 August 1999. Aristocrat alleges that Konami has infringed claims 1, 19 and 56.

3 Konami is alleged to have infringed the patents in suit by (inter alia) manufacturing and supplying the following products:

Free Spin Dragons – which is alleged to infringe product claims 1 – 4, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 37 and 38, and method claims 43, 55 and 56 of the 689 patent.

Cash Carriage – which is alleged to infringe product claims 1 – 4, 16, 25, 27, 28 and 37, and method claims 43 and 55 of the 689 patent.

High Velocity Grand Prix – which is alleged to infringe product claims 1 – 4, 16, 25, 27, 28 and 37, and method claims 43 and 55 of the 689 patent. This product is also alleged to infringe method claim 1, and product claims 11 and 12 of the 341 Patent.

King’s Reward – which is alleged to infringe product claims 1 – 4, 16, 25, 27, 28 and 37 and method claims 43 and 55 of the 689 patent.

Prize Plus – which is alleged to infringe product claims 1, 19 and 56 of the 847 patent.

4 Each of these products is what is known as a feature game. A feature game is a game that can be played during the course of a main game. For example, a gaming console manufactured and sold by Konami under the name Dreaming Orcas Free Spin Dragons consists of a main game, Dreaming Orcas, and a feature game, Free Spin Dragons. It is common ground that there are no material differences between the way in which Cash Carriage, High Velocity Grand Prix, King’s Reward and Free Spin Dragons operate for the purpose of determining questions of infringement relevant to the 689 or 341 patents. In opening it was accepted by Konami that each of these four feature games operate in the same way and that the question of infringement depends upon the proper construction of the claims.

5 For the purpose of resolving questions of validity, the relevant provisions of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) are s 7, s 18(1), s 40 and the definitions of “prior art information”, “patent area” and “prior art base” as defined in Sch 1 as the Act stood immediately prior to their amendment by the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth).

THE WITNESSES

David Little

6 Mr Little was called by Aristocrat. He is an experienced designer of slot machine games. Between 1994 and 1999 he worked as a game designer for Olympic Video Gaming where he designed a number of highly successful poker machine games. In late 1999 Mr Little co-founded Gamewords International Pty Ltd. Mr Little gave evidence relevant to the common general knowledge, claim construction and infringement.

7 Mr Little’s evidence suggested that in 1997 there were material differences between the common general knowledge in Australia and in the United States. However, I am satisfied that at all relevant times the common general knowledge in Australia and in the United States was materially the same, at least in so far as it is relevant to the issues raised in this case.

Andreas de Bruin

8 Mr de Bruin was called by Konami primarily to give evidence on the issue of infringement. Mr de Bruin is an electronics engineer experienced in the maintenance and repair of poker machines. In September 1997, through his company Oztek Pty Ltd, he worked on the development of a wide area linked jackpot system which was the first of its kind in Australia. As a result of this work, Mr de Bruin acquired a detailed understanding and knowledge of different types of jackpots, the different ways in which they can be funded and triggered, and their underlying mathematics. Unlike Mr Ellis, Mr de Bruin is not a game designer.

Michael Gravenor

9 Mr Gravenor was called by Konami. He has tertiary qualifications in computer science. He has been employed by Konami since June 2011 where he is presently responsible for the development of gaming software. Mr Gravenor gave evidence as to how the Konami products work including by reference to various spreadsheets produced by Konami that was the subject of more detailed evidence from Mr Ellis and Mr de Bruin. During his brief cross-examination it was established that Mr Gravenor was not involved in the design of the Konami products. There was no challenge to the description given in his affidavits as to how the Konami products work.

John Acres

10 Mr Acres was called by Konami primarily to give evidence in relation to claim construction and validity. He is the Chief Executive Officer of Patent Investment Licensing Company Inc and Acres 4.0 Inc. His work for these companies involves the creation of promotional concepts for gaming machines and related hardware, software and mechanical structures. He also provides consulting services to the gaming industry. He has a particular interest in player motivation and specialises in player behaviour and the design of games that encourage consumers to play more. He has a degree in mathematics.

11 In 1981 Mr Acres founded a company called Electronic Data Technology which was eventually purchased by International Gaming Technology Inc. In 1985 he co-founded Mikhon Inc. While working with that company he designed a progressive jackpot system that is still in use in casinos throughout the world.

12 Mr Acres often travelled to Australia between 1994 and 1999. During his visits to Australia he provided services to Aristocrat, Crown Casino in Melbourne, and Star City in Sydney.

13 Mr Acres is an inventor or co-inventor of a number of different gaming systems including some that have been patented. He is the inventor of the invention described in Australian Patent No 686824 which Konami contends anticipates each of the relevant claims of the 689 patent. Mr Acres is also a collector of antique slot machines. His collection includes an example of the “Pace Kitty” slot machine.

Benjamin Ellis

14 Mr Ellis was called by Aristocrat primarily to give evidence in relation to the issue of infringement. He is a highly experienced game designer who worked for IGT (Australia) Pty Ltd (“IGT”) between April 1998 and December 1999. During that period he was responsible for designing slot games for use in the Australian and overseas market. This involved conceptualising the games, developing their core mathematical structures (including pay tables, reel strips, bonus attributes and volatility tables). Between January 2000 and September 2002 Mr Ellis carried out the same type of work for Next Generation Entertainment Pty Ltd.

15 Since October 2002 Mr Ellis has been the managing director of a company which he co-founded that carries on business under the name Dynamite Games and which produces a wide variety of gaming products.

16 For the purpose of giving evidence in relation to infringement issues Mr Ellis was provided with copies of the patents in suit and various confidential documents produced by Konami which describe the Konami products. Mr Ellis also attended a demonstration of the Konami products at Konami’s premises. A photographic record was made of relevant parts of that demonstration which is in evidence.

John Willis

17 Mr Willis previously held the position of Global Games Strategist at Aristocrat. He first joined the company as a “games strategist” in 1978. Between 1985 and 1996 he worked for Aristocrat as Senior Market Analyst. He took up other employment with a registered club in early 1996 before returning to work for Aristocrat as Manager of Professional Services. Between 2007 and 2009 he worked for Aristocrat as its Manager of Professional Services. In 2009 he took up the role of Global Games Strategist.

18 Mr Willis gave evidence concerning the various Aristocrat games which were described by him in his affidavit evidence as “Hyperlink Games”. This evidence was relied upon by Aristocrat as evidence of commercial success relevant to the issue of obviousness.

Judianne Kelly

19 Ms Kelly is a “gambling consultant” who gave evidence for Konami. She gave evidence relating to the publication of various trade magazines in Australia. She was not cross-examined. Her evidence is not relevant to any of the legal or factual questions required to be decided.

Mario Castellari

20 Mr Castellari gave evidence for Konami to prove that the gaming machine known as “Lightning Loot” was publicly used in Australia before the earliest asserted priority date of the 689 patent. He was not cross-examined and his evidence was not the subject of any dispute.

Principles of Construction

21 The principles of construction were not in issue except perhaps in one very narrow respect concerning the use that might be made of a number of documents upon which Konami sought to rely in support of its contention as to the meaning of the expression “trigger condition” as used in the claims.

22 The relevant principles have been summarised in many prior decisions of the Court including Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) (Jupiters) and Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 (Emmett, Greenwood and Nicholas JJ) (Multigate) and Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd v Coretell (2011) 93 IPR 188 (Bennett, Gilmour and Yates JJ) in which the Full Court referred at [63]-[69] to the principles relevant to “purposive construction”.

23 For the present purpose it is sufficient to refer to the Full Court’s summary of the relevant principles in Jupiters, which (coincidentally) also concerned a patent for a prize awarding system for electronic gaming machines. Their Honours said at [67]-[68]:

[67] There is no real dispute between the parties as to the principles of construction to be applied in this matter although there is some difference in emphasis. It suffices for present purposes to refer to the following:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 at [81] (Flexible Steel Lacing); and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; 177 ALR 460; 50 IPR 513; [2001] HCA 8 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224–5; (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485–6 (Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd); the court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd at 485–6.

[68] We may add that the area of invention with which this proceeding is concerned is a particularly narrow one. It is one in which business rivals are striving to invent around the patented inventions of others and within narrow regulatory limits. In such a context it is, in our view, important to recognise that claims made for an invention may need to be formulated narrowly to avoid invalidity. While accepting the primacy of purposive construction in interpreting patents, such a construction may well provide little by way of illumination where, as here, the inventive context is a cramped one. It is not appropriate to take a claim carefully drawn to avoid invalidity and then permit a wider “purposive” construction of it for infringement purposes: Grove Hill Pty Ltd v Great Western Corp Pty Ltd (2002) 55 IPR 257; [2002] FCAFC 183 at [311].

24 Konami placed considerable reliance upon the observations made by the Full Court in [68] of its reasons. For present purposes I regard those observations as no more than a salutary reminder that a patent specification is a unilateral document prepared in words of the patentee’s own choosing, usually on the basis of skilled advice, and with an eye to the prior art: see Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] RPC 169; (2004) 64 IPR 444 at [35] and other authorities referred to by Greenwood and Nicholas JJ in Multigate at [45].

THE PERSON SKILLED IN THE ART

25 There was a dispute between the parties as to the identity of the person skilled in the relevant art. Aristocrat contended that the person skilled in the art, or the notional skilled addressee, is a designer of electronic gaming machines. Konami characterised the relevant art somewhat more broadly, and submitted that it extended to the design of gaming systems more generally including jackpot systems and gaming machine networks.

26 The skilled addressee is a notional person who is taken to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention the subject of the patent. A person may have a practical interest in such an invention at a number of levels. He or she may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest.

27 I am satisfied that the notional skilled addressee is a person who has a practical interest in the design or construction of gaming consoles or networks of gaming consoles including associated jackpot mechanisms or systems. This will not only include game designers, but also others who design or construct jackpot mechanisms or systems. On this basis, I am satisfied that each of Mr Little, Mr Ellis, Mr de Bruin and Mr Acres is qualified to give evidence relevant to proof of the common general knowledge as it stood at the earliest asserted priority date and the construction of the patents in suit.

THE COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

28 The notion of common general knowledge was explained by Aickin J in Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (3M). His Honour said at 292:

The notion of common general knowledge itself involves the use of that which is known or used by those in the relevant trade. It forms the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade in considering the making of new products, or the making of improvements in old, and it must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge.

See also Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411 (Alphapharm) at [43]-[45].

29 The common general knowledge may include publications containing information which might not be committed to memory, but which the notional skilled addressee would refer to as a matter of course: ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizol Corporation Inc (1999) 45 IPR 577 (ICI) at [112], per Emmett J.

30 Konami contended that the common general knowledge at the earliest asserted priority date included knowledge of electronic gaming machines which:

(a) have consoles that include means, such as buttons, to allow the player to make selections and play games;

(b) have games with primary or base games;

(c) have games with secondary or bonus features;

(d) have games with triggers;

(e) have games with jackpots;

(f) have games with symbol driven jackpots;

(g) have games with progressive jackpots;

(h) have games with mystery jackpots;

(i) have games where the probability of a player winning is proportional to the size of the wager;

(j) are stand-alone machines;

(k) form part of a network.

31 Aristocrat admitted that subparas (a) to (e) and (j) and (k) were common general knowledge but not (f) to (i) or (k). In light of specific concessions made by Mr Little in cross-examination and the expert evidence more generally, I am satisfied that the matters referred to in subparas (f) and (g) and (h) and (k) were common general knowledge as at the asserted priority date.

32 With regard to subpara (i), Mr Little did not accept that at the asserted priority date there were electronic gaming machines which had games where the probability of a player winning was proportional to the size of the bet. At that time, there were no electronic gaming machines known to Mr Little in which the greater the number of credits wagered on a single line bet, the greater the probability of the player winning a prize. Although a player who wagered multiple credits on a single play line of an electronic gaming machine stood to win a larger prize, the probability of him or her winning any prize was the same for the player who wagered only one credit on the game.

33 In addressing this issue Mr Little distinguished the situation just described from situations involving so-called “multiplier” games which permitted a player to bet on more than one pay line, which had the effect of increasing the player’s chance of winning a prize in proportion to the number of play lines he or she bet on. Thus, a player who bet one credit on each of two play lines would have twice the chance of winning a prize because he or she has, in effect, placed two different wagers. In his evidence, Mr Acres referred to multiplier games as “buy a pay”, “buy a pay line” or “multi-line” games. As he explained, a player can buy additional pay lines on which a win is possible.

34 I am satisfied that the matter referred to in subpara (i) was common general knowledge at the earliest asserted priority date but only insofar as it may be said to refer to “multiplier” or “multi-line” games.

Jackpots

35 Progressive jackpots operate by accumulating contributions from turnover on machines that contribute to the building of the jackpot (ie. the prize or award). Mystery jackpots are a type of progressive jackpot. With a mystery jackpot, a lucky number is electronically selected from a designated range and held in secret. A counter is then activated starting at the lowest value of the designated range. As play ensues, a percentage of each wager is added to the count, and the new count is compared against the secretly held lucky number. If a match occurs, the player whose wager caused the match is awarded the jackpot.

36 Progressive jackpots suffer from a disadvantage due to the manner in which turnover is accumulated. This results in some people not playing the gaming machines once the jackpot is awarded until a significant amount of additional play takes place, and the turnover count has increased to a point at which they consider it more likely that they will win a large prize and therefore worthwhile to play. Once a substantial period of time had passed without a jackpot being awarded, professional gamblers will then move in and commence play and “swamp” the machines.

Cashcade

37 Cashcade is a type of mystery jackpot which accumulates contributions from turnover. It is specifically referred to in the specification as a prior art arrangement that counts turnover on all machines in the network, increments a prize value in accordance with turnover, and pays the jackpot when the count reaches a pre-determined, randomly selected number within a pre-determined range. It is also referred to in the specification as one of a number of arrangements in use in New South Wales and other jurisdictions for a considerable period of time. I am satisfied that Cashcade was common general knowledge at the earliest priority date.

38 The skilled addressee would have been aware that in Cashcade (and linked jackpot systems like it) the pre-determined number would be randomly generated by an electronic random number generator with the jackpot being awarded not on the basis of any combination of symbols on a gaming machine, but on the basis of a match between the turnover count and the random number selected from a pre-determined range (corresponding to the minimum and maximum jackpot values) by the random number generator. The skilled addressee would also be aware that the jackpot was increased incrementally based upon a percentage of the amount wagered by a player on a game, with the jackpot being awarded to the gaming machine that incremented the count to the amount corresponding to the randomly selected number within the pre-determined range.

39 In cross-examination it was suggested to Mr Acres that a problem with some of the prior art was that once the jackpot was won, the players left the machines and did not return until they had a better chance of winning a large jackpot. Mr Acres agreed, and added that this was true of all progressive jackpots. He said this problem (sometimes referred to as “swamping”), which he acknowledged affected Cashcade, was solved by another Aristocrat product called “Surprize”. I will say more about his evidence in relation to Surprize later in these reasons. For the moment it is important to note that Mr Acres accepted that, at least until the advent of Surprize, the problem of “swamping” affected all progressive jackpots.

Gaming Regulations

40 At all relevant times gaming machines have been heavily regulated, and regulatory approval is required for each game before it is released onto the market. The regulators’ requirements cover a wide variety of matters including the “theoretical minimum return to player” (“RTP”), the display of information to players, and the submission of technical and mathematical information referable to games in respect of which regulatory approval is sought.

41 The regulations published by regulators included the Australian/New Zealand Gaming Machine National Standards (“the National Standard”) identified by Mr Ellis as available in New South Wales in 1998. Mr Little was also familiar with the National Standard which he said he would have seen in 1997. The copy of the National Standard that is in evidence (Exhibit A) is designated “Revision 1.0” and is undated. The National Standard (as was acknowledged by Konami in its written submissions) was developed by participants from each of the 10 regulators in Australia and New Zealand. These include the regulators (either government departments or statutory authorities) responsible for the regulation of gaming in each of the States and Territories.

42 The history and purpose of the National Standard is explained in Chapter 1 which “introduces the standards concept, and briefly discussed [sic] the phases involved in the origin and development of these standards.” Paragraphs 1.2 to 1.8 state:

1.2 The purpose of this standard is to work towards creating one basic standard for gaming machines throughout Australia and New Zealand. Initially this will be through this document providing a set of “core” requirements aimed at being common to all jurisdictions. An interim “supplementary document” will list the sections of this document that do not yet have continuity between all participating regulators, and the focal point in the future will be to eventually merge these requirements into the core standard.

Each jurisdiction will provide an addendum to this the above [sic] setting out the additional requirements manufacturers must comply with in that jurisdiction.

1.3 It is the prerogative of each jurisdiction on the extent to which this document is adopted. Whilst it is intended for there to be no conflict between the “core” requirements and individual jurisdictional requirement, [sic] in the event of a conflict the local requirement for that jurisdiction overrides this standard.

…

1.4 The National Standards Working Party was established by the Australian and New Zealand gaming regulators on 21 March 1994. The purpose of the working party was to develop technical requirement documents to be used by each individual jurisdiction as the basis for working towards a common technical requirement for the evaluation of gaming machines.

1.5 Commonality of technical requirements reduces duplication of effort on the part of manufacturers in the design and manufacture of a gaming machine supplied into multiple jurisdictions and provides cost savings when equipment previously approved in one jurisdiction is assessed for approval in other jurisdictions.

1.6 The process for developing national standards involves consultation with equipment manufacturers.

1.7 It has not been, in bringing the document to this stage within the scope of the working party, to attempt to change the divergent industry structures that exist between some jurisdictions. These structural differences result, not only from current regulatory policy but also from the different approaches to gaming machine ownership (venue, private monopolies or duopolies and government) and the level of technology (particularly monitoring and control system technology) available when machine gaming commenced in each jurisdiction.

1.8 Whilst these structural differences exist, jurisdictional specific technical requirements are inevitable. The working party has identified these differences and the focus of the national standards process will now shift to ensuring that any difference in technical requirements between jurisdictions are for valid and unresolvable reasons.

Random Number Generators

43 At all relevant times the relevant regulations required the use of random number generators (RNG or RNGs) for the determination of game results. RNGs are used to generate random numbers. The numbers or range of numbers generated will often correspond to symbols on simulated reel strips which the player observes when playing the game. Combinations of these symbols (or numbers) will result in the award of a prize or (more likely) the loss of the wager.

44 The National Standard provides, in para 3.214, that:

The range of values produced by the RNG must be adequate to provide sufficient precision and flexibility when setting event outcome probabilities, (ie. so as to accurately achieve a desired expected return to player).

Percentage Return to Player (%RTP)

45 The percentage RTP reflects the fact that over time, on average, some total proportion of money wagered on a gaming machine is (and must be) returned to its players. The theoretical percentage RTP equals the total prizes divided by the total number of possible combinations when the quotient is expressed as a percentage. There is a very high probability that the actual percentage return to player will correspond closely with the theoretical percentage return to player. The National Standard requires that there be a statistical expectation that the actual percentage return to player be the same as the mathematically calculated percentage return to player (ie. theoretical percentage return to player).

Turnover and Average Turnover

46 Turnover is the total monetary value of wagers made. Average turnover is an average of amounts wagered over a given period. The desired average turnover for a gaming machine (or a number of gaming machines) is an average turnover expected or targeted by a gaming machine operator that is used to determine the theoretical percentage return to player, prizes and pay tables.

Double-Up

47 “Double-up” provides a player with a chance to double an amount won during a base game in return for making a further wager in the amount won. Players who win playing “double-up” win twice the amount of their original win, but if they lose, then they lose the whole of their original win.

THE 689 PATENT

The priority date

48 The earliest asserted priority date for the claims of the 689 patent is 8 July 1997. However, Konami submitted that the correct priority date is 9 September 1997. The difference between these two dates is approximately two months. By the time of final submissions it was clear that the difference between these dates was immaterial to the resolution of any matter in issue. Against that background, there is no useful purpose to be served in resolving what is a purely theoretical debate as to whether the true priority date is 8 July 1997 or 9 September 1997.

The specification

49 The specification for the 689 patent commences with a description of the field of the invention. This is said to relate to apparatus for use with a system of linked poker machines that provides an improved jackpot mechanism. This is followed by a section entitled “Background of the Invention”. Here, at p 1 line 8 to p 3 line 4, the following appears:

Many schemes have been devised in the past to induce players to play slot machines including schemes such as specifying periods during which jackpot prizes are increased or bonus jackpots paid. Other schemes involve awarding an additional prize to a first player to achieve a predetermined combination on a poker machine. These methods, while effective, add to club overheads because of the need for additional staff to ensure that the scheme is operated smoothly.

More recently, with the advent of poker machines linked through electrical networks it has been possible to automatically generate jackpot prizes on the basis of information received from the machines being played which are connected to the system and one such prior art arrangement, commonly known as “Cashcade™”, counts turnover on all machines in the network increments a prize value in accordance with the turnover and pays the jackpot prize when the count reaches some predetermined and randomly selected number. In a more recent prior art arrangement, each game played on each machine in a gaming system is allocated a randomly selected number and the prize is awarded to a machine when the game number it is allocated matches a preselected random number.

In another recent prior art arrangement, the winning machine is selected by randomly selecting a number at a point in time and decrementing the number as games played on the system are counted until the number is decremented to zero at which time the game (or associated machine) causing the final decrement is awarded the jackpot.

With some prior art combination based trigger arrangements there is a serious disadvantage in that the player betting a single token per line, is just as likely to achieve a jackpot as the player playing multiple tokens per line. This has the effect of encouraging players playing for the bonus jackpot to bet in single tokens, rather than betting multiple tokens per game.

Jackpot games have traditionally been popular in Casinos. However, in their conventional format these games have inherent limitations:

(i) Games which use specific combinations of symbols to trigger jackpots are perceived by many players as being unwinnable. The games are typically designed in such a way that the big jackpots should not be won until large amounts are accumulated. With such low frequency the jackpots are never seen to be won by most players. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many players have learnt to disregard the chance of winning the major jackpots and are realistically playing for the lesser jackpots (ie the minor and mini jackpots). The increasing popularity of small mystery jackpots with higher frequencies of occurrence tends to support this argument;

(ii) Due to the increasing demand of players for a more complex and diverse game range, conventional jackpot games with combination triggers have become superseded. However, it is extremely complex to develop a wide variety of combinations which support both a feature game and mathematically exact jackpot triggers;

(iii) Typically, it would be expected that the game return (RTP) is independent of the number of coins bet per line. With conventional progressive jackpot games though, increasing the credits bet per line creates a relative disadvantage as far as RTP is concerned. Lets say the start-up amount for a feature jackpot is $10000. A player who is playing 1 credit per line has a chance for $10000 for each credit played, whereas a player playing 5 credits per line only has a chance for $2000 for each credit played. This creates a scale of diminishing returns. The smart player who gambles for the feature jackpot only, will always cover all playlines, but will only bet 1 credit per line because the prize paid for the feature jackpot is the same irrespective of the bet. This is supported by data collected from casinos,

(iv) Typical combination triggered progressive jackpots have fixed hit rates which removes from the operator's control the ability to vary jackpot frequency.

These arrangements have been in use in the State of New South Wales and in other jurisdictions for a considerable period of time, however, as with other aspects of slot machine games, players become bored with such arrangements and new and more innovative schemes become necessary in order to stimulate player interest.

In this specification, the term “combinations” will be used to refer to the mathematical definition of a particular game. That is to say, the combinations of a game are the probabilities of each possible outcome for that game.

50 At p 3 line 6 to p 5 line 28 there is a section entitled “Summary of the Invention” which includes the following consistory statement:

According to a first aspect the present invention provides a random prize awarding feature to selectively provide a feature outcome on a gaming console, the console being arranged to offer the feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition, the console including trigger means arranged to test for a trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to credits bet per game on the console.

According to a second aspect, the present invention provides a random prize awarding system associated with a network of gaming consoles, the system being arranged to offer a feature outcome on a particular console when a trigger condition occurs as a result of a game being played on the respective console the prize awarding system including trigger means arranged to test for a trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome on the respective console when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to credits bet per game on the respective console.

According to a third aspect, the present invention provides a gaming console including a random prize awarding feature to produce a feature outcome, the gaming console being arranged to offer the feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition, the console including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to credits bet per game on the console.

51 At p 4 lines 1 to 4 the patent specification states that, preferably, the trigger condition is determined by an event having a probability related both to expected turnover between consecutive occurrences of the trigger condition on the respective console and the credits bet on the respective game.

52 At p 4 lines 5 to 11 the patent specification explains how, in a preferred embodiment, the trigger condition is determined. A random number is selected from a pre-determined range of numbers to be associated with each bought game and for each credit bet on the respective game. These numbers are allotted to the game. If any of these numbers correspond to a randomly selected number from the same pre-determined range then the trigger condition will have occurred.

53 At p 4 lines 12 to 35 of the specification a number of preferred embodiments of the invention are described. For example:

a plurality of consoles may be connected to form a network, allowing a central feature jackpot system connected to the network to provide an incrementing jackpot which increases in response to signals from the consoles connected to the network (lines 12 to 17);

the consoles may be arranged to play a first main game and the feature outcome initiated by the trigger condition is a second feature game (lines 18 to 20); and

the function of triggering a feature jackpot game may either be performed by a central feature game controller or a feature game controller within each console in the system (lines 21 to 23).

54 There then follows a detailed description of preferred embodiments of the invention by reference to three figures. Figure 1 is a diagram of a network of gaming consoles connected to a mystery jackpot controller. Figure 2 is a flow chart for a prize awarding algorithm. Figure 3 shows the example of a 5 reel by 3 row window display.

55 At p 6 line 2 to p 7 line 2 the specification describes a preferred embodiment in which jackpots (feature jackpots) are won from a feature game as follows:

In a preferred embodiment of the invention, a new jackpot trigger mechanism provides the Casino operator with a far higher degree of flexibility. Unlike conventional combination triggered jackpots, the jackpots here are won from a feature game. The feature game is triggered randomly as a function of credits bet per game. When a feature is triggered, a feature game appears. Each jackpot can only be won from this feature game. During the feature game a second set of reel strips appears and a “spin and hold” feature game commences. The feature prize score is calculated by the total of the points appearing on the centre line of all 5 reels.

Feature jackpots in this format exhibit significant differences over previous jackpot systems:

(i) A jackpot game is provided which is compatible with any existing game combination within an installation independent of the platform, denomination or type of game (eg. slot machines, cards, keno, bingo or pachinko). This will allow for the linking of combinations between game type, platform type and denomination. Using this system, jackpot games can now be developed using specific combinations for the base game which were previously unsuitable for Link Progressive Systems. These games will compete with the appeal of the latest games on the market.

(ii) There is no longer a need to develop mathematically exact combinations in the base game.

(iii) Unlike the multiplier game in combination triggered jackpot embodiments, the present invention provides a direct relationship between the number of credits bet and the probability of winning the jackpot feature game on any one bought game. Betting 10 credits per line will produce ten times as many hits into the feature game than betting 1 credit per line. This is achieved by using a jackpot trigger which is directly related to the wager bet on a respective game and the turnover, instead of using conventional combination triggers.

(iv) Jackpot hit rates can now be changed without making changes to the base game. This was previously not possible using combination triggered jackpots.

(v) The jackpot feature system can be used across a wide-area-network (WAN), local-area-network (LAN), used as a stand-alone game independent of a network or used with a mystery jackpot. Flexibility is available to change combinations at will.

56 The specification describes the preferred embodiment at p 8 line 10 to p 10 line 27 as follows:

In the preferred embodiment, a prize is always awarded in the jackpot feature game, the feature game being used to determine the size of the prize to be awarded (see step 27). The winning machine is then locked up (see step 28) and the controller awaits an indication that the prize has been paid before allowing the machine to be unlocked (see step 29). In some embodiments, the machine will not be locked up in steps 28 and 19, but instead the prize will simply be paid and the program will return to step 21. The machine then returns to step (see step 21) and commences a new game. If the trigger value does not match (see step 27) then there is no feature game awarded for that bought game and the machine returns to step (see step 22) and waits for the next game to commence.

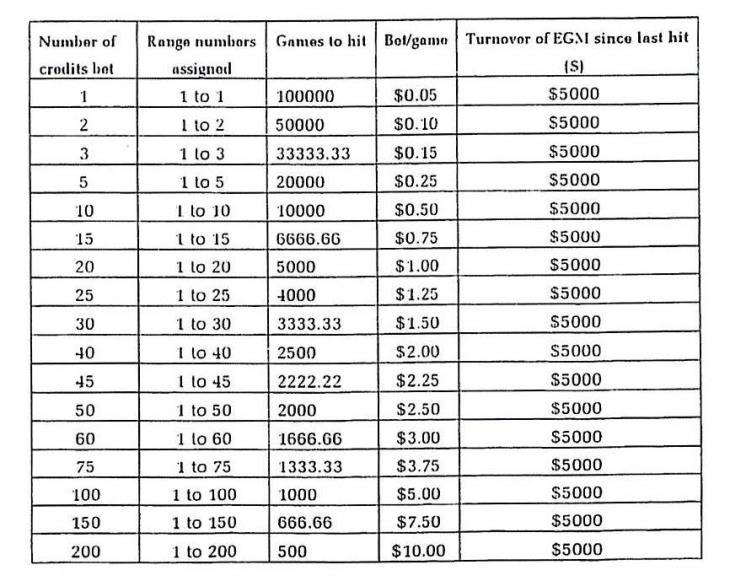

By way of example, a feature game might be triggered by an EGM every $5000 of turnover played, which is equivalent to 100,000 credits on a $0.05 machine. This is referred to as the jackpot feature game hit rate in credits. A random number is generated within a prescribed range of numbers at the EGM at the commencement of each bought game. The prescribed range of numbers is determined by the jackpot feature game hit rate which has been determined previously, from typical values of casino turnover, expected jackpot amounts and jackpot frequencies. The prescribed range in this example is therefore 1 to 100,000 and before the commencement of each bought game a random number is generated within this range.

A bet of 20 credits will result in the numbers between 1 and 20 (inclusive) being allotted to the game (note that statistically it does not matter if the numbers are randomly selected or not or allotted as a block or scattered, the probability of a feature game being awarded is unchanged). If the number 7 is produced by the random number generator, then the feature game will be triggered. If any number between 21 and 100,000 is produced by the random number generator, the feature game will not be triggered. Similarly, a bet of 200 credits will result in the numbers between 1 and 200 (inclusive) being allotted to the game. If any number between 1 and 200 is produced by the random number generator, then the feature game will be triggered. If any number between 201 and 100,000 is produced by the random number generator, the feature game will not be triggered.

The example below has been developed using example turnover data. A trigger of the second screen feature game is expected every $5000 of turnover (ie. 100000 credits on a $0.05 machine). Increasing the number of credits bet increases the chance of triggering the feature on any bought game.

Preferably, when a jackpot feature game is triggered, all players are alerted by a jackpot bell that a possible grand jackpot is about to be played for. This is done so that all players share in the experience of a jackpot win. Anecdotal evidence of players watching feature games being played in Australian casinos suggests that the drawing power of such games is immense.

Players are alerted by the jackpot bell instantaneously at any point during a game, but the feature game will not appear until the current game (including base game features) are completed.

In this embodiment the feature game appears with the new reel strips already spinning and accompanying feature game tunes playing. The player stops the reels spinning by pressing the corresponding playline buttons in order. The feature prize score is calculated by the total of the points appearing on the centre line of all 5 reels. Across the top of the screen, a sum of the scores is displayed.

The 4 feature prize meters in descending order of value are:

(i) Grand Feature Prize. A score of > 100 wins the grand feature jackpot:

(ii) Major Feature Prize. A score of 90-99 (inclusive) wins the major feature jackpot:

(iii) Minor Feature Prize. A score of 80-89 (inclusive) wins the minor feature jackpot:

(iv) Mini Feature Prize. A score of < 79 wins the mini feature jackpot.

By way of example, referring to Figure 3, a 5 reel by 3 row window is displayed. If the reels of the feature game stop on the numbers shown in Figure 3, then the progressive jackpot won is the sum of the numbers on the centre line ie. 12+10+18+13+22 = 75 which is within the range for the mini feature jackpot.

The instant the feature game is completed and the sum of scores from all 5 reels is shown, the feature jackpot screen and signs display which jackpot has been won. This celebration of the jackpot win is conducted in a traditional manner (ie. flashing displays, jackpot alarms, music etc).

57 At p 10 lines 28 to 31 it is observed that, as the time between the jackpot game awards is related to turnover, the number of jackpot games played between feature games and, hence their chance of winning, is directly related to the size of each bet on each game played.

58 The claims of the 689 patent that are alleged to be infringed fall into three groups; first, claim 1 and various dependent claims, second, claim 25 and various dependent claims, and third, claim 43 and various dependent claims:

1. A random prize awarding feature to selectively provide a feature outcome on a gaming console, the console being arranged to offer a feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition, the console including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console.

2. The prize awarding feature of claim 1, wherein the trigger condition is determined by an event having a probability related both to expected turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console and the credits bet on the respective game.

3. The prize awarding feature of claim 1 or 2, wherein the console is arranged to play a main game, during which testing for the trigger condition will occur, and the feature outcome initiated by the trigger condition is the awarding of one or more feature games.

4. The prize awarding feature of claim 3, wherein the main game is a standard game normally offered on the console and each feature game is a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize.

5. The prize awarding feature as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4, wherein the trigger condition is determined by selecting a random number from a predetermined range of numbers to be associated with each main game, and allotting to the game a set of numbers selected from the predetermined range of numbers, the size of the set of allotted numbers being related to the wager bet on the respective game, and in the event that one of the numbers allotted to the game matches the randomly selected number, indicating that the trigger condition has occurred.

6. The prize awarding feature as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4, wherein the trigger condition is determined by selecting a random number from a predetermined range of numbers to be associated with each main game, and allotting to the game a set of numbers selected from the predetermined range of numbers, the size of the set of allotted numbers being mathematically related to the wager bet on the respective game, and in the event that one of the numbers allotted to the game matches the randomly selected number, indicating that the trigger condition has occurred.

7. The prize awarding feature as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 6, wherein the trigger condition is determined by selecting a random number from a predetermined range of numbers to be associated with each main game, and allotting to the game a number in the set of numbers, the allotted number being proportional to the wager and in the event that the allotted number is greater than or equal to the randomly selected number, indicating that the trigger condition has occurred.

…

16. The prize awarding feature as claimed in any one of the preceding claims wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of winning a major prize than in the main game.

17. The prize awarding feature as claimed in claim 16, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

…

25. A gaming console including a prize awarding feature to produce a feature outcome, the console being arranged to offer the feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition and including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console.

…

27. The gaming console of claim 25 or 26, wherein the console is arranged to play a main game, during which testing for the trigger condition will occur, and the feature outcome initiated by the trigger condition is the awarding of a feature game.

28. The gaming console of claim 27, wherein the main game is a standard game normally offered on the console and the feature game is a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize.

…

37. The gaming console as claimed in any one of claims 25 to 36, wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of success than the main game.

38. The gaming console as claimed in claim 37, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

…

43. A method of awarding a prize on a gaming console, the console being arranged to offer a feature outcome when the game has achieved a trigger condition, the method including testing for the trigger condition and when the trigger condition occurs offering the feature outcome, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition on the respective console.

…

55. The method as claimed in any one of claims 43 to 54, wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of success than the main game.

56. The method as claimed in claim 55, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

(emphasis added)

59 I have reproduced claims 5, 6 and 7 even though they are not alleged to have been infringed. These claims are of some significance because they define various arrangements that are described as preferred in the body of the specification. I note that claims 6 and 7 use the phrases “mathematically related to the wager” and “proportional to the wager” respectively.

60 The three independent claims which are said to be infringed are:

claim 1 for a “random prize awarding feature”;

claim 25 for a gaming console “including a prize awarding feature”; and

claim 43 for a “method of awarding a prize”;

The Construction Issues

61 In its closing submissions Konami identified three issues of construction with respect to claim 1 of the 689 patent which may be encapsulated in the following propositions:

The “trigger condition” of the claim is not (or does not include) a “combination trigger”.

The probability that the trigger condition will occur must be directly related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition.

The “feature outcome” of the claim is the outcome of the “random prize awarding feature” which can include a jackpot.

62 Each of these propositions is disputed by Aristocrat. With respect to the first two issues, Aristocrat contends that Konami’s construction of the claim imposes an impermissible gloss upon the clear words of the claim. As to the third issue, Aristocrat contends that the term “feature outcome” should be given meaning on the basis that, when used in relation to gaming consoles as at the asserted priority date, the term “feature” is a technical term, or at least a term that should be given a special meaning, that refers to an event which typically involves some manual or automatic game play subsequent to the trigger event, and that this does not include a jackpot. I shall deal with these three construction issues in turn.

“trigger condition”

63 Konami submitted that the words of claim 1 confine the meaning of “trigger condition” to triggers which are not part of the rules of a game, ie. which are not combinations of a game on the console. According to Konami’s written submissions:

(a) the invention of the claim is a “random prize awarding feature” because the probability of the feature occurring is defined by an “event” which is not a combination of a game. The skilled addressee will read “random” as having that effect because he or she knows that, necessarily, any game on any console must produce random outcomes. In the claim, “random” signifies that the feature which is provided by the console is not part of a game on it and that the “event” which determines the trigger condition is not a part of such a game;

(b) the claim distinguishes between a console, which offers a feature, and a game on the (or a) console. The whole of the claim is concerned with the relationship between the console and the feature. The game on the console is limited to playing a role in the invention which is indicated by the single reference to it. The words of that reference are not apt to describe a trigger condition which is a result in a game;

(c) The third integer of the claim provides:

“ ... the console including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs.”

Those words indicate that the trigger condition is external to the rules of any game on the console. It accumulates with the words of the second integer to make clear that the trigger condition and the means by which it operates all function outside the rules of the game on the console. Combination triggers are not external to a game. As the definition of “combination” at 3:l shows, combinations define a game and therefore, are internal to it.

64 I do not accept Konami’s submission.

65 First, as a matter of language, the claim does not require that the event which constitutes the trigger condition not be a combination of the game. Nor do I think the presence of the word “random” indicates to the skilled addressee that it does. Secondly, the fact that the claim is concerned with a feature on a gaming console does not imply that the feature cannot be triggered by a combination trigger that is produced as part of the game play that occurs on the console. Here again, I do not think the words of the claim would indicate to the skilled addressee that a combination trigger that occurs as part of the game play in the main game cannot also constitute an event that triggers the prize awarding feature. In my opinion, none of the matters relied upon by Konami indicate that the trigger condition must be external to the main game.

66 In support of its submission Konami also referred to Mr de Bruin’s affidavit evidence. Like the Konami submission, his evidence focuses on the presence of the word “random”. However, Mr de Bruin’s evidence does not persuade me that the notional skilled addressee would interpret the expression “trigger condition” as excluding “combination based trigger conditions”. I think he was inclined to read the claim too narrowly and to pay insufficient regard to the broad language used.

67 The specification contains various references to “combination based trigger arrangements”, “combination triggers” and “typical combination triggered progressive jackpots”. The expression “trigger condition” as used in the claim and in the “Summary of the Invention” does not expressly or by implication exclude a combination based trigger condition. On the contrary, a “combination based trigger condition” is, as a matter of language, a type of “trigger condition”. In this regard, I consider that the language of claim 1 is clear.

68 In a short note handed up in the course of Konami’s closing submissions reference is made to various correspondence, a statutory declaration and other documents included in Exhibit 8 (said by counsel at the time they were tendered to be relevant to inventive step and claim construction) and to the decision of Falconer J in Furr v C D Truline (Building Products) Ltd [1985] FSR 553. This decision (in which Falconer J refused an interlocutory injunction restraining alleged patent infringement) was relied upon by Konami in support of the rather cryptic proposition that a statement made by Aristocrat’s patent attorneys in a letter to the Examiner dated 13 July 2006 was “admissible as an admission against interest by Aristocrat as to, among other things, the actions taken to secure the grant of the patent”. While I would accept that a statement in a document of this kind might constitute an admission as to the common general knowledge as at a particular date, the patent attorneys’ letter was not relied on by Konami for that purpose. I do not regard that letter, or any of the other documents referred to in Konami’s note, as constituting evidence relevant to the proper construction of any of the patents in suit: see Prestige Group (Australia) Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1990) 26 FCR 197 at 213.

relationship between probability that trigger condition will occur to desired average turnover

69 It is common ground that claim 1 expressly requires that the probability that the trigger condition will occur be related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition on the console. However, Konami submitted the probability relationship referred to must be “direct”. As to what “direct” means in this context, Konami’s submission is that the relationship must be “linear” and that this linearity must be mathematically exact.

70 In support of its submission on this issue Konami relied on the evidence of Mr de Bruin. On his reading of the specification, Mr de Bruin considered that the relationship referred to in the relevant claims had to be “direct”. By “direct” I understood him to mean that the mathematical relationship between the amount wagered on the game and the chance of winning the feature prize had to be exactly proportionate. To take an example, Mr de Bruin would say that the chance of a player winning who wagered $10.00 on a particular game should be precisely ten times that of a player who wagered only $1.00 on the game.

71 On Mr de Bruin’s interpretation of the relevant claims, a direct relationship will exist if a first player who wagers $1.00 has a 1 in 10,000 chance of winning (P = 0.0001) and if a second player who wagers $10.00 has a 10 in 10,000 chance of winning (P = 0.001). However, according to Mr de Bruin, there will be no direct relationship if a first player who wagers $1.00 has 1 in 10,000 chance of winning and a second player who wagers $10.00 has a chance that is slightly greater than 10 in 10,000 (eg. P = 0.0010001). In this regard, Mr de Bruin would read the relevant claims as requiring that there be absolute or perfect linearity in the probability of the first and second players winning the feature prize.

72 Mr de Bruin relied upon various references in the body of the specification to the “direct relationship” between the number of credits wagered and the probability of winning the feature prize in any one game. He referred, in particular, to para iii at p 6 lines 23 to 30 of the specification and the passage at p 10 lines 28 to 31. I have referred to these parts of the specification at paras [55] and [57] above.

73 Aristocrat contended that the words of the relevant claims are clear and unambiguous, and that Konami’s contention that they should be read as requiring that the probability of the trigger condition occurring be directly related to (inter alia) the credits bet on the respective game finds no support in either the body of the specification or the claims themselves.

74 I do not accept Aristocrat’s submission that the relevant words are clear and unambiguous. Reading the relevant claims literally would produce absurd outcomes which the skilled addressee would be quick to dismiss on the basis that they could never have been intended. In particular, the requirements of the relevant claims would be satisfied if there was any relationship between the probability of the trigger condition occurring and the amount wagered on the game including, for example, a relationship whereby the probability of the trigger condition occurring decreased in proportion to the amount wagered by a player on the respective game.

75 In my view, when the relevant claims are read in the context of the specification as a whole, what is described is a relationship in which the probability of a trigger condition occurring is positively correlated to desired average (or expected) turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition on the console and the amount wagered by the player on the game.

76 However, I do not accept that the relationship must be mathematically exact. There is nothing in the body of the specification to justify Mr de Bruin’s insistence that the probability relationship be exactly proportionate to desired average turnover. The skilled addressee would not expect very slight variations in the relative probabilities to produce different outcomes. I will return to this issue when considering the differences in the relative probabilities relied upon by Mr de Bruin in support of his opinion on the question of infringement.

77 In the result, I accept that the skilled addressee would understand the relevant claims to be referring to a direct relationship between the probability of the trigger condition occurring and the desired average (or expected) turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition. Beyond that, however, I think the broad language of the claims should be given effect, and not read down by importing any more specific requirement of the kind postulated by Konami, including, in particular, any requirement that the relevant relationship be absolutely or perfectly “linear”.

“feature”, “feature outcome” and “feature game”

78 Konami submitted that the “feature” of claim 1 and its dependent claims is a feature that is additional to the game on the console which will produce a “feature outcome” in the event the trigger condition is fulfilled. According to Konami, the feature may be a simple jackpot or something which involves some further interaction between the player and the console before the feature outcome is revealed, whether it be a jackpot or some other prize (eg. a free spin).

79 Aristocrat submitted that the word “feature” had at the asserted priority date a technical meaning to the following effect:

Any additional free game, free spin of certain reels, metamorphosis of the basic game rules or secondary choice necessary to complete a game (except gamble) is considered a feature.

80 This is the definition given to the term in the Glossary to the National Standard. The word “gamble” (referred to by way of exception in the definition of “feature”) is defined in the Glossary to include a game option, such as Double-Up, that may be selected following a win, which allows a player to wager his or her winnings in game play providing a higher return to player.

81 The National Standard includes requirements with respect to “features” or “feature games” at paras 4.64 to 4.72. The kinds of features that are referred to in these paragraphs include free games, re-spins, held reels, bonus prizes (where one or more bonus prizes are paid to the player during the feature sequence) and metamorphic games.

82 The nature of these “features” is largely self-explanatory. Each involves some change in the basic game play. This is also true of “metamorphic games” (another term defined in the Glossary) which a player enters from another game. The Glossary defines a “metamorphic game” as:

A game entered into from another game (where generally a higher [return to player] exists or an accumulated bonus prize results) which the player must risk money on in order to play.

83 It is clear from a reading of the National Standard as a whole that, so far as it is concerned, a jackpot is not a feature although a feature may ultimately result in the player winning a jackpot (eg. through a free spin).

84 Mr Ellis’ evidence was that the term “feature” is generally understood in the gaming industry to be an infrequent and valuable event often involving some manual or automatic game playing subsequent to the trigger event (my emphasis). According to Mr Ellis, the use of the term “feature” in the 689 patent is consistent with his own understanding of that term. In this regard, he pointed to the distinction drawn at p 4 lines 18 to 20 of the specification between a “main game” and a “feature outcome” that is a “second feature game”. That there is a distinction between a feature game and the first (or base) game is also apparent from other parts of the specification including p 5 lines 6 to 12, p 10 lines 3 to 18, and p 10 lines 32 to 33.

85 Similarly, Mr Little defined a “feature” as a change in game play occurring as a result of a combination of symbols on the console (ie. a combination trigger condition) which temporarily enhances the player’s immediate prospects of success. Like Mr Ellis, Mr Little does not regard a jackpot as a feature.

86 Mr Acres described a “feature” as any distinguishing characteristic of game operation or game play. He offered the following examples of features:

a gaming machine that features a bill or note acceptor that eliminates the need for coins;

a game that features 5 spinning reels;

a game that features a video screen;

a game that features a feature game or a secondary game.

87 It is apparent that Mr Acres understands the term to have its ordinary meaning viz. a distinctive attribute or aspect of the gaming machine, the game or the game play. It is apparent that his definition of “feature” is very broad and can also encompass physical characteristics of a gaming machine that may have no connection with game play. Mr Acres also described a “feature game” as a game or an award that is in addition to the base game and a “feature outcome” to mean the awarding of one or more feature games or prizes (my emphasis). He considers a jackpot, or a jackpot mechanism, can be a “feature” of a gaming machine on the basis that it is a distinguishing characteristic of the gaming machine and the experience it provides. In term of the claims, he considers that the award of a jackpot is a “feature outcome”.

88 The 689 specification defines a number of terms (eg. “combinations”) but does not include a definition of the term “feature”. Nor does it include any reference to the National Standard. Curiously, neither Mr Ellis nor Mr Little referred to the National Standard in their affidavit evidence.

89 Mr Ellis’ definition of the term “feature” is different to what appears in the National Standard. In his oral evidence Mr Ellis said he regards a free spin as a feature. He made the point that if a free spin is awarded (unlike a progressive jackpot) the player is required to engage in some additional game play (ie. by taking the free spin). His evidence as to what constitutes a “feature outcome” when the relevant feature is a free spin was somewhat confusing, but he seemed to think that the result of the free spin (eg. the award of a jackpot prize) would constitute, or at least be part of, the “feature outcome”.

90 Mr Little’s definition of the term “feature” is also different to what appears in the National Standard. The National Standard does not define the term by reference to any enhancement of a player’s prospects. On Mr Little’s definition, a free spin would not be a feature, or a feature outcome, because (unless there is some applicable change in the rules in the case of a free spin) the prospects of winning with a free spin do not change. However, Mr Little said that in his experience most free spins involve multipliers that do increase the player’s prospects of success.

91 The question whether the word “feature” is used in the 689 patent in a technical sense, as contended by Mr Ellis and Mr Little, or in a more general sense that reflects the ordinary meaning of the word, must be considered in light of the specification read as a whole as it would be understood by a person skilled in the art.

92 Although there is reference made in the body of the specification to feature jackpots and feature games, the only part of the body of the specification that refers to a (random prize awarding) “feature” per se is the consistory statement. Hence, the specification provides no clear guidance as to whether the term “feature” is used in any technical sense or in accordance with its ordinary meaning. However, if anything, the use of the expression “feature jackpot” tends to suggest that the term is used, at least in the context of the discussion of the prior art, in accordance with its ordinary meaning. In this regard, I note that the discussion of the prior art at p 2 lines 25 to 26 twice refers to “feature jackpot”.

93 In its submissions Konami placed considerable emphasis upon the extensive discussion in the body of the specification concerning jackpots and jackpot mechanisms including, in particular, the title of the 689 patent which refers to the invention as a “slot machine game and system with improved jackpot feature”. This was said by Konami to tell against a construction of the expression “random prize awarding feature” that excludes a jackpot or jackpot mechanism.

94 The introduction to the specification (p 1 lines 1 to 5) states that the present invention provides “an improved jackpot mechanism”. The focus of the discussion of the prior art that follows is on prior art arrangements that result in the award of jackpots. It is apparent that the invention is aimed, or purportedly aimed, at overcoming particular problems with these prior art arrangements, including, in particular, the relative disadvantage suffered by players of conventional jackpot games who wager multiple credits per game (or playline) compared to the players who wager a single credit per game or line.

95 The specification describes “a random prize awarding feature” to selectively provide a feature outcome that may result in the award of a jackpot prize. This is what I understand to be the “improved jackpot feature” of the invention referred to in the title of the patent. The jackpot prize that is awarded as a result of the random prize awarding feature will itself be a prize or “special jackpot prize” associated with a “feature game”.

96 When the specification is read as a whole, it is clear that a “feature game” as referred to in claims 3 and 4 is the award of an additional game (which game is the “feature outcome”) via which a player may then win a prize (eg. “a special jackpot prize”).

97 Thus, claim 3 when read with claim 1 requires that there be a “main game” with the “feature outcome” constituting the award of one or more feature games. Claim 4, when read with claim 1 and claim 3, requires that each “feature game” be “a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize.”

98 However, in my view it does not follow that a jackpot, or a jackpot mechanism, cannot be a feature for the purposes of claims 1 and 2. These claims are not limited to features that provide, or feature outcomes that consist of, one or more feature games. In my view the word “feature” is used in the claims in accordance with its ordinary meaning. I am therefore satisfied that a jackpot, or a jackpot mechanism, can be a random prize awarding feature, and that the award of a jackpot can be a “feature outcome” within the meaning of the claims. Thus, in the case of a simple progressive jackpot, the jackpot, or jackpot mechanism, can be a feature and the award of the jackpot can be the “feature outcome” within the meaning of claims 1 and 2.

99 I do not accept (as was suggested by Mr Acres) that any prize can be a “feature”. Although a feature game may be awarded as a prize, and a jackpot may be the outcome of a feature game, a jackpot is not a “feature game” within the meaning of claim 3 or claim 4. Nor do I consider a jackpot to be a “simplified game” within the meaning of claim 16.

Infringement

100 Konami’s principal defence to the infringement case based upon claims of the 689 patent is that:

There is no infringement because each of Konami’s games uses a combination of symbols to trigger the feature in a conventional symbol trigger way.

There is no infringement because, on any particular play of the game, the chance of triggering the feature is not directly proportional (ie. linear) to the credits wagered on the game.

101 The first of these defences must be rejected in light of my construction of the expression “trigger condition”. The second is based upon a construction of the claims that requires that there be a perfectly “linear” relationship between the probability of the trigger condition occurring and desired average turnover and/or credits bet on the respective game. For reasons previously explained, I reject Konami’s argument that absolute linearity is required.

102 Mr Ellis’ Confidential Exhibit BJE-17 (see also Exhibit C) includes the relevant probability figures for the Konami feature game “Cash Carriage”. BJE-17 is a spreadsheet that shows the amount wagered per game and the probability of the trigger event occurring. The spreadsheet shows that the probability of the trigger condition occurring increases in direct proportion to the amount wagered. The spreadsheet and Mr Ellis’ related calculations also show that for each wager that is made, the chance of the trigger condition occurring is equal to the size of the wager divided by the desired average turnover between successive trigger conditions on the console.