FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 651

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. This proceeding be adjourned for directions at 10.15 am on Friday 14 August 2015.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 109 of 2009 |

BETWEEN: | BRITAX CHILDCARE PTY LTD (ACN 006 773 600) Applicant INFA-SECURE PTY LTD (ACN 092 222 994) Cross-Claimant |

AND: | INFA-SECURE PTY LTD (ACN 092 222 994) Respondent BRITAX CHILDCARE PTY LTD (ACN 006 773 600) Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | MIDDLETON J |

DATE: | 30 June 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[44] | |

[45] | |

[50] | |

[53] | |

Topic 4 — “wherein the connection strap is attached to the tether strap” | [59] |

Topic 5 — “secured” (with respect) to a “head end of the back rest portion” | [63] |

[69] | |

[74] | |

[77] | |

[81] | |

[84] | |

[87] | |

[97] | |

[104] | |

[110] | |

[113] | |

Topic 16 — “tethering means for tethering the backrest portion of the child safety seat” | [117] |

[122] | |

[124] | |

[126] | |

[129] | |

Topic 18 —“substantially as illustrated” (the “flat plate” as a “major improvement”) | [133] |

[141] | |

[149] | |

[155] | |

[160] | |

[165] | |

[171] | |

[175] | |

[180] | |

[185] | |

[187] | |

[190] | |

[195] | |

[197] | |

[213] | |

[232] | |

[236] | |

[239] | |

[241] | |

[255] | |

[260] | |

[269] | |

[282] | |

[285] | |

[287] | |

[289] | |

[292] | |

[299] | |

[304] | |

[305] | |

[307] | |

[308] | |

[310] | |

[311] | |

[312] | |

[328] | |

[341] | |

[341] | |

[354] | |

[355] | |

[356] | |

[360] | |

[363] | |

[366] | |

[367] | |

[372] | |

[373] | |

[375] | |

[378] | |

[380] | |

[387] | |

[397] | |

[400] | |

Alleged anticipatory prior art (documents and specifications) | [407] |

[408] | |

[411] | |

[415] | |

[415] | |

[423] | |

[429] | |

[435] | |

[442] | |

[447] | |

[447] | |

[450] | |

[451] | |

[451] | |

[456] | |

[473] | |

[483] | |

[487] | |

[488] | |

[489] | |

[492] | |

[496] | |

[499] | |

[500] | |

[505] | |

[524] | |

[525] | |

[533] | |

[544] | |

[546] | |

[556] | |

[556] | |

[561] | |

[569] | |

[579] | |

[587] |

1 This is the fourth judgment in this proceeding. The various claims and cross-claims that have been made in this proceeding are set out in Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (2012) 290 ALR 47 (‘Construction Judgment’). I adopt the same terms and abbreviations in these reasons for judgment. I assume a familiarity by the reader of these reasons with the earlier judgments in this proceeding, particularly the Construction Judgment.

2 This judgment concerns the validity of certain claims of the Patents in suit, and an issue relating to infringement, namely whether the allegedly infringing Infa products are within the scope of certain integers of the claims of the relevant patents in suit. The parties agreed that upon delivery of these reasons, they would consider appropriate orders, including timetabling (if necessary) for the consideration and determination of any outstanding issues.

3 Between the date of the first judgment in this proceeding and the last hearing in February 2013, there was a great deal of procedural disputation between the parties. This disputation was mainly concerned with the reception of expert evidence in relation to infringement, although some aspects impacted on the validity dispute.

4 I make this preliminary observation. The parties and the expert witnesses now have had the opportunity to address the Construction Judgment, and to apply the Court’s construction of the principal terms in the context of the claims in suit. Since the Construction Judgment the Court and the parties have moved on from the specific terms and phrases chosen by the parties for interpretation by the Court at the time of the Construction Judgment. It was hoped that by delivery of the Construction Judgment the parties could resolve their dispute, but this has not occurred. Therefore, it has become necessary to revisit the construction of each patent in context, in dealing with the allegations of infringement and invalidity.

5 As I said at [280] of the Construction Judgment:

Before construing each term or phrase in issue, the following consistencies claimed by the expert witnesses should be noted. The expert witnesses assert in the joint expert report that Issues 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 represent universal points of difference between Mr Newman and Mr Hunter, which are common across the patents where these terms are used. This does not necessarily mean, however, that once a decision as to the construction of one of these “Issues” is reached, it will apply globally to each claim in suit. Each must be assessed in the context of the claim in which it appears using, if necessary, the specification of the patent to aid construction. The context must not be forgotten even though we are focussing on particular words or phrases.

6 I have already referred to some relevant principles of construction in the Construction Judgment. I stress that in further construing the claims in each patent, I have made no reference to the alleged infringing products. It is clearly impermissible to do so.

7 I make the observation that in this proceeding, Infa has taken an overly literalistic view of the terms of the claims in each patent, where such an approach is inappropriate in the context of each claim in each Patent. Whilst Britax suggested that the Court took such an approach in one instance in the Construction Judgment (in relation to the terms “ends” and “carried by”), that approach was conducted in context. I arrived at that interpretation because of the plain meaning to be given to those terms —I was not persuaded that any surprising or absurd result would arise by adopting the natural meaning of the terms “ends” or “carried by” in the context of the patents I was considering. That view stands despite an invitation by Britax to re-consider those terms.

8 Britax further submitted that Mr Hunter’s opinion as to the construction of the terms “ends” and “carried by” was correct and therefore my findings in relation to those terms in the Construction Judgment were incorrect.

9 There is no reason in principle for the Court not to correct an error made in interlocutory reasons. That said, I am not persuaded by Britax’s submissions or Mr Hunters’ evidence in relation to the construction of those terms, and I do not depart from my reasons and findings in relation to construction of those (or any other) terms in the Construction Judgment.

10 Now that the parties have had the opportunity to place before the Court submissions and evidence to deal with the principal terms referred to in the Construction Judgment in context, the most appropriate way to deal with the current dispute between the parties is to consider the various topics raised by the parties for my determination, and proceed accordingly.

11 This was what was anticipated following upon my orders and reasons in Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 1018, delivered on 17 September 2012. I will not repeat the background to those orders and reasons, which background is set out in those reasons.

12 In that decision, the Court gave reasons in support of its orders and in furtherance of the Court’s preference to receive a Further Joint Expert Report from the two experts, Mr Hunter (for Britax) and Mr Newman (for Infa). In addition, the Court made certain statements and observations (at [26-30]) about the task then envisaged for the two expert witnesses.

13 By orders dated 17 September 2012, in summary, the Court ordered that the Construction Judgment should be provided to the expert witnesses, and that those witnesses should be asked to provide further evidence by way of a Further Joint Expert Report as to the presence or absence of the claimed patent integers in the allegedly infringing Infa products. Further, the Court specifically confined the materials to be provided to the two experts and made allowance for either expert to seek additional time, materials, information or advice if that was required.

14 In furtherance of the Court’s orders, on 20 and 21 November 2012, the expert witnesses conferred in a supervised conference in the presence of Registrar Sia Lagos and the solicitors for the parties. Thereafter, the expert witnesses provided the Court with the Further Joint Expert Report.

15 As required by the Court, the Further Joint Expert Report both applied the Court’s Construction Judgment to each of the allegedly infringing Infa products and patents in suit, and provided the Court with the experts’ position as to the presence or absence of the relevant patent integers in those Infa products. In large part, the two experts were in agreement as to the presence or absence of the relevant integers in the relevant Infa products.

16 Accordingly, the position was that after provision of the Further Joint Expert Report, the only matters relating to infringement which remained for determination by the Court were those limited matters where the persons skilled in the art (the two expert witnesses in this proceeding, Messrs Hunter and Newman) were in disagreement or had some other basis for failing to arrive at an agreed position as to the presence or absence of particular patent integers in the Infa products.

17 Following the provision of the Further Joint Expert Report, a further hearing relating to the Further Joint Expert Report was to commence on 10 December 2012. It was envisaged that the two expert witnesses would be in attendance and would provide the Court with further explanation on the limited number of infringement issues upon which there was remaining disagreement as relevant to the specific Infa products.

18 On 10 December 2012, Infa handed up to the Court and to Britax documentation by way of four new tables which were contended by Infa to contain conclusions on construction and infringement that arose from the Construction Judgment. These tables contained material which put into contest some of the experts’ agreed views and conclusions relevant to infringement as set out in the Further Joint Expert Report. Infa’s Counsel advised the Court that Infa wished to cross-examine the two experts as to the matters in the four tables, including an application to treat Mr Newman as an “unfavourable witness” under s 38 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (‘Evidence Act’).

19 Britax submitted that the Court reject this new material. It submitted that Infa was seeking to make a new case under the guise of applying the Construction Judgment. Britax also contended that it had had no time to consider the extensive material set out in the four new tables and was in no position to proceed with the hearing on that day. The Court ultimately decided that Infa should be permitted to explore the issues raised by the four tables with the two experts.

20 As a consequence, on Britax’s application, the hearing was adjourned to 13 August 2013 to enable Britax to further consider the material advanced by Infa in the four tables, and on Infa’s explanation to the Court that those four tables represented its “non-infringement” position.

21 On 5 August 2013, Infa filed and served another affidavit from Mr Newman, (‘Fifth Affidavit’). It raised a number of matters of significance in the content of the Further Joint Expert Report, including matters upon which Mr Newman had changed his mind.

22 Despite the lateness of the filing and serving of the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman, the hearing set down for 13 August 2013 proceeded. It was ultimately adjourned to 17 February 2014 but not before Mr Newman was cross-examined by Britax on the circumstances surrounding the coming into existence of the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman. Mr Newman confirmed that he had no problems with the process that led to the preparation of the Further Joint Expert Report in November 2012, nor any issues with the content of the document at the time of its preparation. Nevertheless, Mr Newman did not now adopt his position as expressed in the Further Joint Expert Report.

23 Mr Newman’s problems with the Further Joint Expert Report appeared to arise following a discussion with the lawyers for the Infa on 11 December 2012, shortly after the December 2012 adjourned hearing. In his Fifth Affidavit, Mr Newman stated that on 11 December 2012 he was asked by Chrysiliou Lawyers (the lawyers representing Infa) to explain a particular statement contained in the Supplemental Report to the Further Joint Expert Report, and that as a result he re-examined all the integer tables of the Further Joint Expert Report.

24 Mr Newman’s evidence was that he had reflected upon the process of his giving of evidence in the proceeding, including his participation in the Further Joint Expert Report, and had decided that he could not maintain his position as set out in that Report. He gave various reasons for this.

25 Mr Newman had found the whole process in participating in the Further Joint Expert Report “incredibly complicated” and “confusing”. He found it difficult in determining how to interpret the Patents on their own, but also in light of the Construction Judgment. He felt confused at the time of the November 2012 conference with Mr Hunter, and had been influenced by Mr Hunter’s superior mental agility, when at a time his own mind was “in a spin”.

26 A great deal of time has been undertaken by the Court and the parties on the production and receipt of the expert evidence, including the Further Joint Expert Report in November 2012. However, the reliance on the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman by Infa caused further delay. The August 2012 hearing needed to be adjourned until 17 February 2014 to allow sufficient time for the parties to consider their position and file further material.

27 On 31 October 2013, Infa (not wholly accepting Mr Newman’s new approach) filed and served tables raising points of construction and disputing the presence of the patent integers in the Infa products.

28 When the matter came on for hearing on 17 February 2014, Britax contended that the matters and issues raised by those tables should be rejected by the Court for a number of reasons. One reason was that such matters and issues had not been considered earlier, particularly in the Further Joint Expert Report. Another reason was that to the extent the matters and issues were raised by Mr Newman in his Fifth Affidavit, these should be rejected either because they were raised by him only due to influence brought to bear upon him following the adjourned hearing in December 2012, and because in any event, Mr Hunter (whose evidence was to be preferred) did not accept Mr Newman’s position.

29 I am sympathetic with some of the observations made by Britax on the way the proceedings progressed after the introduction of the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman. Mr Newman clearly changed his mind upon reflection after the Further Joint Expert Report, and this has significantly disrupted the flow of the proceedings. It has been a substantial cause for the extensive material now before the Court.

30 However, Mr Newman (as an expert witness) was under an obligation to inform the Court of his changed position. After all, the Court should receive such expert evidence so that the Court may be fully assisted in its task. This is not to say that Mr Newman’s position must be accepted; only that it should be considered. Further, Britax and Mr Hunter were given adequate opportunity, of which they availed themselves, to address Mr Newman’s changed position as well as Infa’s subsequently filed tables.

31 I have therefore accepted the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman into evidence, to consider it along with all the other expert evidence, including significantly the Further Joint Expert Report.

32 I have also (over the objection of Infa) accepted the eighth affidavit of Mr Hunter. This affidavit was in response to the earlier material of Infa and Mr Wainohu, and is in my view responsive to that material. Infa had ample opportunity to address that affidavit, and the issues raised by the experts have been adequately ventilated between them in the presence of the Court. In the way the proceeding has progressed, it would be unfair to Britax (and Mr Hunter) not to consider his response to matters raised by Infa’s evidence in his eighth affidavit.

33 Both parties proceeded in the February 2014 hearing on the basis of the terms as construed in my Construction Judgment, as is apparent from the approach of the experts in dealing with the issues formulated for and considered by them at that hearing, and the submissions themselves. No party was disadvantaged by this approach. Each had an opportunity through their experts and legal representatives to address the construction of the integers in the context of each claim and each patent in suit and issues of invalidity.

34 Nevertheless, the above process and Mr Newman’s own self-confessed confusion, does impact on the confidence the Court can repose in Mr Newman’s evidence. I do not find that Infa’s legal representatives did anything improper. I also do not accept Britax’s submission that Mr Newman can no longer be regarded as an independent expert. Mr Newman remained independent, but was simply out of his depth in the task he was asked to perform. Mr Newman’s experience was primarily as a fitter of child safety seat products. Whilst he was a qualified motor vehicle mechanic, he was not an engineer. He has not been involved in the design, testing or manufacture of child restraint products. During the course of this proceeding, Mr Newman has had general difficulty in dealing with specific issues and has changed his views or admitted error. In contrast, Mr Hunter’s evidence involved a practical, common sense approach to the working of the relevant claims of the patents in suit, and, in the main, I have found it persuasive.

35 These reasons have taken some time to be delivered, and despite the passage the time, I have not deviated from the initial view I took as to the correct approach to adopt in this proceeding. That approach was to consider the evidence of Mr Newman including his Fifth Affidavit, but to take into account the various matters that I raise in these reasons for treating his evidence with caution. Much of the evidence and submissions before me has been in written form, and transcript has been available. In formulating these reasons I have re-visited that documentation. Neither party suggested that Mr Hunter or Mr Newman were not trying to assist the Court to the best of their ability. The principal issue with Mr Newman relates to his capacity to properly understand the patents in suit, or articulate, his position. It was in this sense that Britax submitted Mr Newman’s evidence was not credible, putting aside the issue of independence. I now have the competing expert views as to construction, infringement and validity. I must make an assessment based upon analysis of the evidence (both expert and lay), the documentary material in evidence and the submissions.

36 The position that the Court now needs to consider is as follows.

37 Subject to the two substantive reservations (as to meaning of “ends” and “carried by”), Britax otherwise accepts the agreed position relating to infringement that Mr Newman and Mr Hunter arrived at in the Further Joint Expert Report.

38 Noting that Mr Hunter has reservations with some of the findings of the Court in the Construction Judgment in relation to the interpretation of certain terms (to which I will return), and insofar as the Court may now review its earlier construction of such terms, Britax adopts the position of Mr Hunter but accepts that Mr Hunter is disagreeing with certain of the Court’s findings in the Construction Judgment (namely as to the meaning of “ends” and “carried by”).

39 As I have indicated, shortly before the August 2013 hearing, Mr Newman in his Fifth Affidavit resiled from many of the opinions he expressed in the Further Joint Expert Report. Further, Infa did not accept all the views of Mr Newman.

40 In light of this position of the parties, and in preparation for the hearing adjourned to February 2014, by orders of the Court dated 16 August 2013 the parties were required to prepare “Green and Red” tables specifying, by reference to the “Newman Tables” annexed to the Fifth Affidavit of Mr Newman and in relation to construction and infringement, what matters in the Newman Tables Infa adopted and what additional matters it relied upon (each marked green), and what matters relied upon by Infa were agreed by Britax, and if not why not, (such marked in red). Infa provided its tables, and Britax provided its response.

41 Britax adopted the report of the expert Mr Hunter who set out his views on the Infa Green Tables by his own Red Table analysis supported by his supporting narrative set out in three Addendums, each of which are annexed to the affidavit of Mr Gregory R Tye sworn 17 December 2013 and marked respectively “GRT-4”, “GRT-5”, and “GRT-6”, and each of which were referred to respectively as “Hunter Addendum-1”, “Hunter Addendum -2”, and “Hunter Addendum -3”.

42 I have not reproduced the tables referred to above, as they were of more assistance to the parties and the Court in focussing attention upon the context of the issues raised.

43 The matters canvassed by Britax and Mr Hunter insofar as they relate to infringement can be considered against the diagrammatic depictions of the various Infa product versions illustrated in Exhibit A7 (which is ‘Annexure A’ to these reasons). Some of the actual Infa products were in evidence.

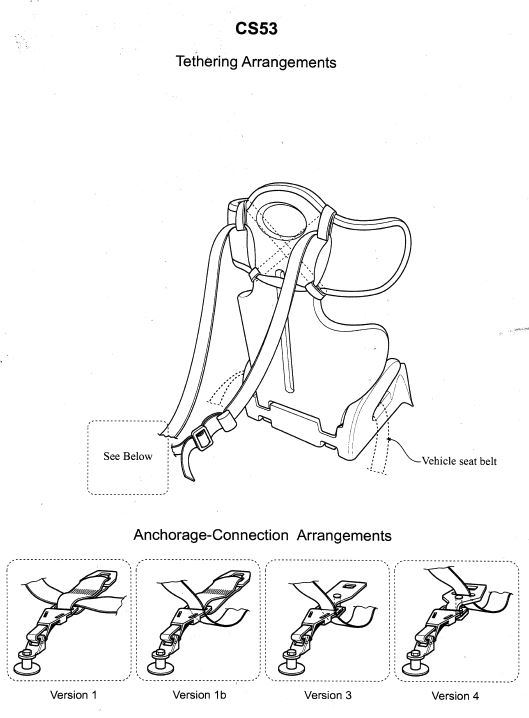

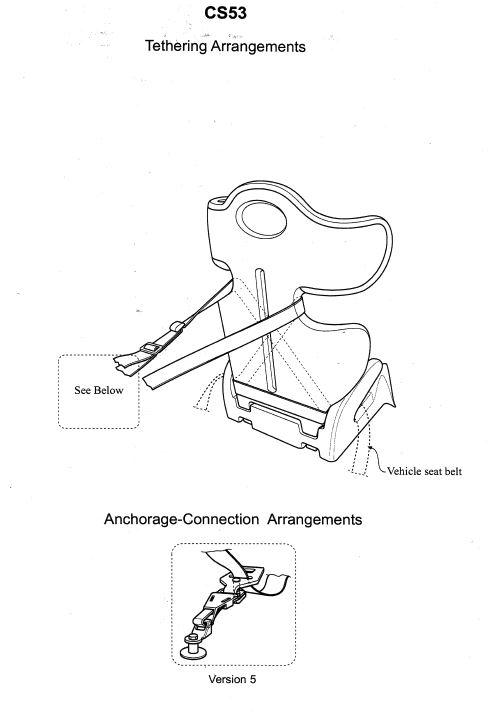

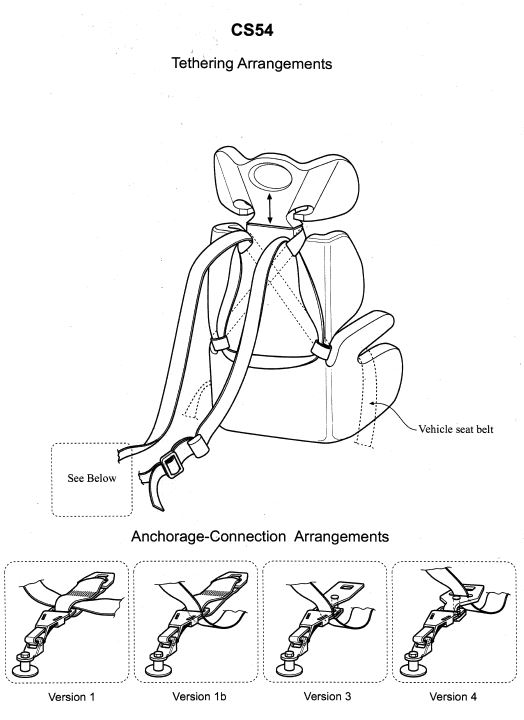

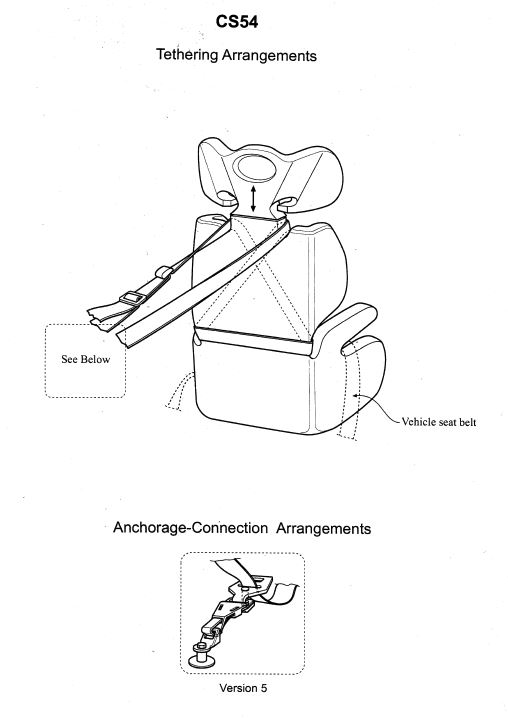

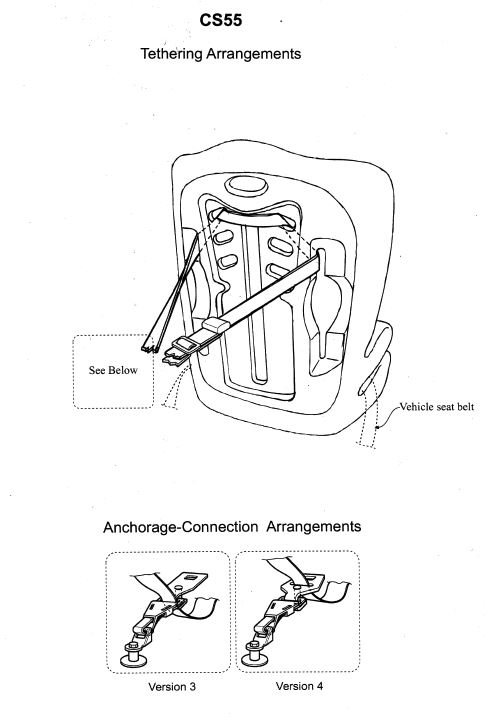

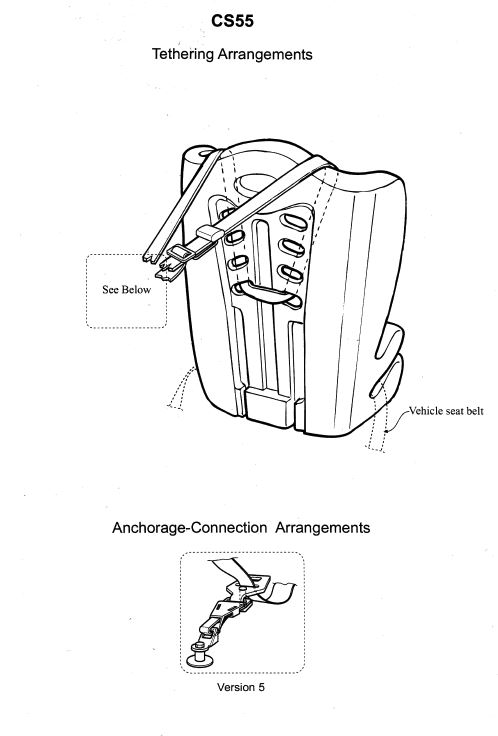

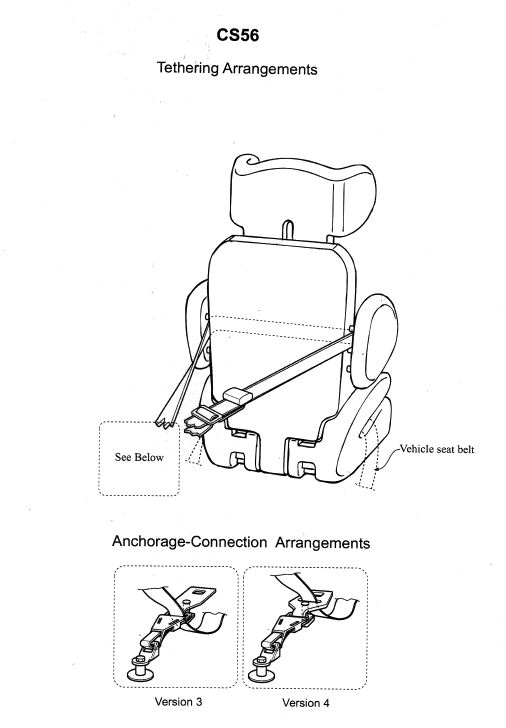

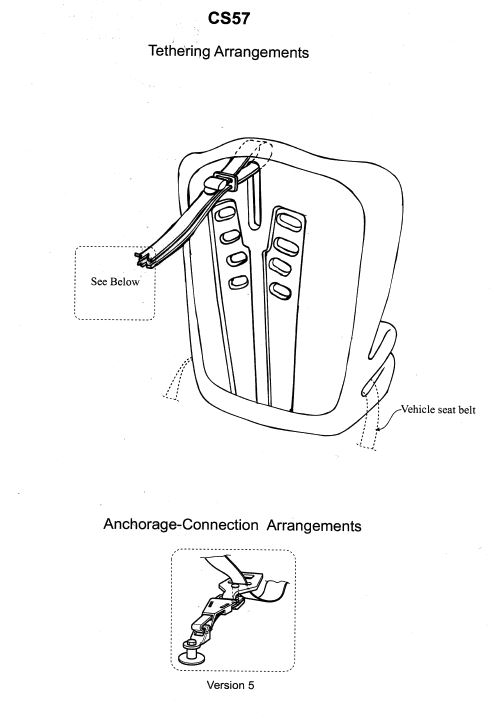

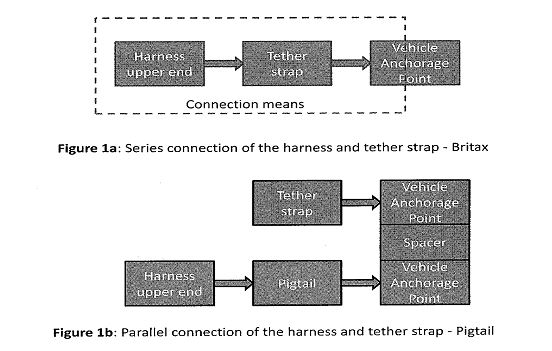

44 I will now deal with the issues before the Court concerning infringement. For the purposes of these reasons, my consideration of infringement is limited to the question of whether the allegedly infringing products fall within the scope of the relevant patent claims. To that end, the parties agreed that the issues in contention in this regard were confined to 22 discrete “topics”, and a question as to whether the Infa products fall within the omnibus claims present in the patents (which I will refer to as “topic 23”). Those topics are titled by reference to certain issues or terms as construed in my Construction Judgment. I address each of the topics in turn, and in doing so, I make reference to the Infa products which are alleged to have been infringed in relation to that topic (‘Infa Products’), the diagrams of which are contained in Annexure A. The various Infa Products are identified by their product code and version (eg “CS53” or “CS53v4”), and the “Anchorage-Connection Arrangement” version (or ‘Version’) used with that product, as depicted in Annexure A.

Topic 1 — “carried by” or “with respect to”

45 In my Construction Judgment, I distinguished between the terms “carried by”, which I found refers to a direct carrying, and “with respect to”, which may include indirect carrying: see Construction Judgment at [314] and [377]. In the context of the relevant claims, those terms refer to the tether strap which transports, moves, bears or carries the “connection strap” or “means”, and suggest an interaction between the two.

46 I construed the term “connection means” in my Construction Judgment to be a broad term not limited to a buckle (eg at [318]) and which could therefore include other components, such as a latching hook.

47 Infa submitted that the word “by” in “carried by” required the tether strap to be an “active” carrier, and the carried connection strap to be a “passive” component. It submitted that this was not so in the Infa Products, by reference to the fact that if the tether strap were to be severed, the connection strap would remain attached to (or “carried by”) the anchorage point, which would demonstrate that the tether strap was a passive component which was in fact “carried by” the connection strap.

48 However, the term “carried by” must be understood in the context of the relevant patent. For example, claim 1 of the First Patent describes “a connection strap carried by the tether strap and secured at a first end with respect to the anchorage point and having a connection means at the other end”. The object is clearly the (carried) connection strap, which is then secured. Whether the outcome of that anchoring or “securing” shifts or reverses the load bearing dynamics, so that the connection strap bears the load of the tether strap, is not relevant for the purposes of the patent.

49 This view accords with the views of both skilled addressees, Messers Hunter and Newman. As Mr Hunter opined, the unsecured connection strap is clearly carried, in the sense that its load is borne, by the tether strap. In the Further Joint Expert Report, the experts agreed (and I accept) that all Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1, 4 and 5, contain this feature, and therefore fell within the scope of the relevant “carried by” integers in claim 1 of the First, Third, Fifth and Sixth Patents, and claim 5 of the First, Third and Sixth Patents.

Topic 2 —“connection strap” or “connection plate”

50 In my Construction Judgment, I held that the term “connection strap” was broad enough to include straps of different materials (including metal or flexible webbing) in different contexts: see [311]. At [307] I detailed Mr Hunter’s accepted approach which gave the term “strap” a “broad, functional and contextual interpretation” and explained a connection strap to be an “interconnecting device which allows the harness and tether strap to be connected to the vehicle anchorage point”.

51 Infa contended that the U-shaped metal connecting component present in Infa Product Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 3, 4 and 5 is not a “strap”, but rather a “plate”. However, this distinction is unnecessary for the purposes of construing the Patent terms. As I stated in my Construction Judgment at [311], a “connection strap” may be metal. That is so in the context of a child safety seat, and regardless of whether it is characterised as a “plate”.

52 In the Further Joint Expert Report, both Messers Newman and Hunter agreed on this basis that the “connection strap” feature was present in all Infa Products which have any of the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions. All Infa Products therefore fall within the scope of the relevant “connection strap” integers in the following claims:

(a) claim 1 of the First and Sixth Patents;

(b) claim 2 of the First Patent;

(c) claim 3 of the Second and Third Patents;

(d) claim 4 of the Third Patent; and

(e) claim 5 of the First Patent.

Topic 3 — connection strap (or means) “attached” to the tether strap (or strap) “adjacent the intermediate point”

53 In my Construction Judgment at [319] I held that that term “attached” did not require “fixation”, and in its context could refer to the connection strap being slidably attached to the relevant strap. I also construed the “intermediate point” by reference to my construction of the term “ends”: at [302]. As I mentioned earlier, Mr Hunter and Britax took issue with my construction of the term “ends”, which I did not accept.

54 In the Further Joint Expert Report, Messrs Newman and Hunter agreed that the connection strap or means in all Infa Products was “slidably attached”. Nevertheless, they both concluded that integers 1.2.2 and 3.2.2 were not present in any of the Infa Products. This conclusion was drawn solely on the basis that the connection strap (or means) was not attached to the tether strap adjacent the intermediate point, as a consequence of their construction of the term “ends”, which was at odds with my finding in the Construction Judgment.

55 Infa submitted that a slidable attachment takes it out of the scope of the relevant claim, since in the unanchored child safety seat, the slidable connection could result in the connection strap sliding away from the intermediate point.

56 However, the reference to “intermediate point” in claim 2 in each of the First and Third Patents is dependent on the respective claim 1 in those patents, and relates to the term “point intermediate its ends” in that claim. In claim 1 of both patents, the attachment adjacent the intermediate point is described as occurring when the tether strap is in its anchored state: “secured with respect to the anchorage point at a point intermediate its ends” (emphasis added).

57 I agree with Mr Hunter’s observation that “[o]nce these seats are installed, the connection strap is attached adjacent the intermediate point notwithstanding the slidable connection of the connection strap with respect to the tether strap”.

58 I therefore find in applying the terms as construed in the Construction Judgment and the evidence of the experts that all Infa Products fall within the scope of those integers in claim 2 of the First and Third Patents.

Topic 4 — “wherein the connection strap is attached to the tether strap”

59 Infa contended that the presence of a “latching hook” in the Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1b and 3, means that those products do not fall within the scope of claim 2 of the First Patent. This is because the intermediate component (ie the latching hook) prevents the required “attachment” of the connection and tether straps.

60 However, there is no requirement in the claims that there must be a direct attachment. This is a different matter from the context of “carried by” as interpreted by the Court. An attachment can involve an intermediate component, as is in fact depicted in many of the preferred embodiments in the First Patent. In that patent, the attachment of the connection and tether straps is depicted (in figures 4-6) with an intermediate component.

61 As I mentioned in relation to Topic 3, the experts did not find that the Infa Products fell within the scope of integer 1.2.2 on the basis of a construction of the term “ends” which was at odds with the Construction Judgment. Importantly, neither Mr Newman nor Mr Hunter expressed any issue with the latching hook found in some of the Infa Products as taking those products beyond the scope of integer 1.2.2.

62 For those reasons I am not persuaded by Infa’s submission in relation to this topic.

Topic 5 — “secured” (with respect) to a “head end of the back rest portion”

63 In my Construction Judgment I determined that the term “secured” does not require fixation, and allows for any fastening, whether slidable or not as long as “the fastening is firm, so that it will not tear or break when used for the purpose for which it was developed”: at [299]. I adopted this construction for the Second Patent (at [333]), Third Patent (at [340]), Fourth Patent (at [356]), Fifth Patent (at [361]) and Seventh Patent (at [383]).

64 At [328] of the Construction Judgment, I found that the meaning of the term “head end of the backrest potion” depended on whether the headrest was adjustable or not. In the former, the term referred to the upper part of the back rest underneath the headrest, and in the latter, it referred to the upper part of the back rest.

65 In the Further Joint Expert Report, Messrs Newman and Hunter agreed that in all Infa Products the tether strap or tethering means was “secured to”, or “secured with respect to”, the head end of the back rest portion as claimed. Mr Newman’s position in this respect did not change in his Fifth Affidavit.

66 Infa submitted that the experts’ views in this regard narrowly considered the “secured” feature in the context of an installed seat experiencing sudden deceleration (such as a collision scenario) in which the tether straps would tighten. It submitted that this context represented a “momentary and transitory state”, and that in normal use the tether straps would not be “secured”.

67 However, I do not understand the experts to consider the term so narrowly. Once installed, the pressure of the taut tether straps on the safety seat satisfies the “secured” requirement. Considering this integer in the context of an uninstalled safety seat with the tether straps falling loosely, as Infa contended, is to fail to take a common sense approach to the patent claims, or to understand its terms in the context of the relevant integers. It is important to focus upon the word “secured” which connotes an installed state in this context.

68 I therefore do not accept that the tether strap or tethering means is not “secured” to the head end of the back rest portion, with the consequence that all Infa Products fall within the scope of the relevant integers of the following claims:

(a) claim 1 of the Second, Fourth and Fifth Patents;

(b) claim 2 of the Seventh Patent; and

(c) claim 5 of the First and Third Patents.

69 The term “adapted to” means “being capable of”. This is the ordinary meaning of the term and was as agreed between the experts.

70 The contexts in which the phrase is used relates to “a connection means arrangement adapted to co-operate with a tether strap” (integer 8.1.2), and a tether strap or child safety harness being “adapted to”:

(a) be secured to an anchorage point on a motor vehicle (see, eg, integer 1.5.7);

(b) tether the child safety seat (integer 8.1.2); and

(c) be used with a child safety seat (integer 9.1.2).

71 Infa contended that the relevant item (eg the tether strap) must itself be capable of the relevant function (eg being secured to an anchorage point) without any intermediate components. Infa also relied in this regard on my Construction Judgment where I held (at [291]) that “the tether strap includes the material which makes up the strap itself and nothing more”.

72 However, context is essential. In my view, the relevant contexts outlined above allow for the use of intermediary components which facilitate the necessary “adaption”, such as latching hooks. For example, as Mr Hunter pointed out, in the context of a tether strap adapted to be secured to an anchorage point, figure 5 of the First Patent, which appears in all of the innovation patents in suit (‘Innovation Patents’), depicts intermediate componentry.

73 Further, both experts agreed in the Further Joint Expert Report (and I accept) that all Infa Products fell within the scope of this integer in the relevant claims.

Topic 7 — “secured to” and direct connection

74 In the Further Joint Expert Report, both experts agreed that the “secured” and “secured to” features were present in all Infa Products. This position was not changed in Mr Newman’s Fifth Affidavit.

75 In line with its argument in relation to topic 6, Infa submitted that the term “secured to” requires that there be a direct connection, so that, for example, the phrase “tether strap adapted to be secured to an anchorage point” (see, eg, integer 1.5.7) negates the presence of intermediate componentry. For the reasons outlined above, I agree with the experts’ conclusion and do not find that the term means that the tether strap (for example) must be directly connected to the vehicle anchorage location without intermediate components. I further reiterate my finding in the Construction Judgment that the term “secured” simply requires firm “fastening”, the nature of which is unrestricted by that term: see [299], [333], [340], [356], [361] and [383].

76 All of the relevant Infa Products are therefore within the scope of the integers containing the terms “secured” or “secured to” in the relevant claims.

Topic 8 — harness “loops” at the “ends”

77 In the Construction Judgment (at [300]) I found that the “ends” of the tether strap are to be understood as the physical termination points of the tether strap. Some integers refer to the “strap having at least one loop at each end” (see, eg, integers 2.2.2 and 4.2.2). The depiction of such an arrangement in figures 2 and 3 of the Innovation Patents is consistent with my finding.

78 However, Infa submitted that figure 1 of each of the Innovation Patents reveals that one of the loops is not formed at the “termination point” of the strap, and instead, there is some length of strap extending back behind the padding after forming a loop. It therefore characterised this arrangement as a single strap with a loop at only one “end”.

79 As I have mentioned, the terms of the integers must be understood in a way in which makes practical sense in their context. In the particular context of the relationship between the harness and the seat belt, the reference to “ends” sensibly means the lower looped ends of the pair of shoulder straps through which the vehicle seat belt is passed. Whether or not that looped end is formed at the physical termination point of the strap, is of no consequence in this context. I agree with Mr Hunter’s view in this regard that a skilled addressee would readily understand this.

80 I note that both experts in the Further Joint Expert Report relevantly agreed that an “H” or “Protecta” harness (ie a harness which includes a pair of shoulder straps that are each connected at their lower end to the seat belt by respective loops) would fall within the scope of the relevant integers of the relevant claims. Accordingly, any Infa Product when used with such a harness would fall within the scope of those integers.

Topic 9 — “connected/attached to” and direct connection

81 In line with its argument in relation to topics 6 and 7, Infa submitted that the terms “connected to” and “attached to” require a direct connection without intermediate components. It therefore viewed all Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1, 4 and 5 (which contain components interposed between the tether strap and anchorage point), as not falling within the scope of those terms.

82 Infa’s reading in this way is at odds with the findings in my Construction Judgment, and a practically sensible reading of the patents in context. There is no basis in the patent specifications to limit such terms in the manner proposed by Infa. For the reasons outlined above, I agree with the experts’ conclusion and do not find that the terms “connected to” or “attached to” require a direct connection to the vehicle anchorage location without intermediate components.

83 In the Further Joint Expert Report, Mr Newman and Mr Hunter agreed that all Infa Products incorporated components that were relevantly attached or connected as expressed in the above terms of the patents, and therefore fell within the scope of the relevant integers of claim 3 of the Second and Fourth Patent.

84 Claim 3 of the Second and Fourth Patents refers to a connection strap or means “attached to and extending from the tether strap latching hook to which the upper ends of said shoulder straps are attached”. Infa submitted that the words “to which” are referable to the “tether strap latching hook”, and not the “connection strap [or means]”, so that they require the latching hook to be directly attached to the shoulder straps. It therefore contended that the Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1, 4 and 5, where the connection strap (or plate) is interposed between the upper ends of the shoulder strap and the latching hook are therefore not captured by those integers.

85 I do not consider there to be ambiguity in those integers, when read in the appropriate context. The syntax of the claim dictates that the correct antecedence for the integer “... to which the upper ends of said shoulder straps are attached” is the relevantly preceding “connection strap” or “connection means”. This reading is reinforced by figures 2, 4, 5 and 6 in both patents and by reference to

(a) the specification of the Second Patent which states at 8.8-10 in relation to figures 3 to 5 that:

The harness 20 is secured with respect to the vehicle through latching hook connector 26, connection strap 44, an aperture in buckle 45 and latching hook connector 43.

(Emphasis added)

(b) the specification of the Fourth Patent which states at 6.27-9 in relation to figures 3 to 5 that:

The harness 20 is secured with respect to the vehicle through latching hook connector 26, connection means comprising a connection strap 44, an aperture in buckle 45 and latching hook connector 43.

(Emphasis added.)

86 Further, in the Further Joint Expert Report, the experts agreed (and I accept) that all Infa Products fell within the scope of integers 2.3.5 and 4.3.5 of claim 3 of the Second and Fourth Patent.

Topic 11 — “harness extends from the backrest portion”

87 Claim 1 of the Fourth and Seventh Patents contains the words “wherein said harness [or ‘child safety harness’] extends from the backrest portion”: integers 4.1.11 and 7.1.11.

88 Infa contended that some Infa Products require the harness to pass over or around the headrest, not the backrest, and therefore would not fall within the scope of those integers.

89 In relation to backrests and headrests, the Infa Products contain two broad types: those without a headrest (such as CS53, CS55 and CS57) and those with a headrest (CS54 and CS56).

90 I pause to note that consistent with my findings in my Construction Judgment (at [328]), CS53, which does not have an adjustable headrest section, is not considered, for the purposes of construction of the patents, to have a separate headrest. Rather, on my construction, its non-adjustable headrest would constitute the “head end of the back rest”.

91 On all Infa Products without a headrest, the harness necessarily “extends from the backrest portion”. On those Infa Products which contain a headrest, the tethering arrangements in Annexure A clearly depict the harness extending from the backrest portion and not from the adjustable headrest.

92 Infa also submitted that integers 4.1.11 and 7.1.11 require a “positional” arrangement wherein the harness extends from the physical backrest (via, for example, apertures in the backrest itself). This was contrasted with a “directional” arrangement, whereby the harness straps simply pass the back rest (via, for example, grooves in the perimeter of the seat).

93 Although figures 3, 4 and 5 of the patents depict the harness passing through apertures in the backrest, the specification of the Fourth Patent, in relation to figures 3-5 states (at 6.21-4) that:

Although multiple pairs of apertures are shown in this preferred embodiment, it would also be possible to have the harness passed through a single aperture in the head end of the backrest portion or around grooves in the perimeter of the backrest portion.

(Emphasis added.)

94 Almost identical wording to the above paragraph is contained in the specification of the Seventh Patent: at 7.19-22. It is therefore clear from the context of those integers that the relevant patents contemplate either a “positional” or “directional” arrangement of the harness in relation to the backrest.

95 The experts agreed in the Further Joint Expert Report that all Infa Products fell within the scope of integers 4.1.11 and 7.1.11 of claim 1 of the Fourth and Seventh Patents respectively.

96 All of the relevant Infa Products are within the scope of the relevant integers for the relevant claims.

97 Claim 3 of the Third Patent refers to “a latching hook connector...attached with respect to the [tether] strap by a strap opening in the latching hook connector that allows the latching hook connector to slidably locate on the strap”. Claim 2 of the Fifth Patent refers to a “child safety seat…wherein the connection means slidably locates on the tether strap”.

98 Infa submitted that Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1, 4 and 5 are not within integer 3.3.3. Infa focussed on the directness of the latching hook connector being slidably located on the tether strap. However, there is no requirement in the Third Patent that the latching hook connector must directly slidably locate on the tether strap. In those Versions, the latching hook connector is indirectly slidably located on the tether strap via the loop or aperture in the connection strap or plate. Versions 1, 4 and 5 therefore fall within the terms of integer 3.3.3, as observed by Mr Hunter.

99 Infa also contended that Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1b and 3 are not within integer 5.2.2, since they do not include the incorporated antecedent integer 5.1.7 —“a connection means carried by the tether strap”. I have already addressed the issue of “carried by”.

100 Further, as I mentioned in topic 1, the term “connection means” is not the same as “connection strap”. The former is a broader term —“any item or thing which would perform the function of connection” and includes the latching hooks in the Fifth Patent: see Construction Judgment at [316-8] and [366]. The specification of the Fifth Patent (at 6.21-3) describes the “connection means” as “comprising a connection strap 44, an aperture in buckle 45 and latching hook connector 43”.

101 Both Infa’s Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1b and 3 have the above described “connection means”. Both include a tether strap which is slidably located through an aperture in the latching hook connector. Conversely, the latching hook connector (and thereby the “connection means”) is slidably located on the tether strap. That arrangement falls within integer 5.2.2.

102 In the Further Joint Expert Report, Messrs Newman and Hunter agreed that the latching hook connector is slidably located on the tether strap for Infa Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1, 4 and 5, and that the connection means is slidably located on the tether strap for Infa’s Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 1b and 3.

103 For the above reasons, all of the relevant Infa Products fall within the scope of the relevant integers of claims 3 and 2 of the Third and Fifth Patents respectively.

Topic 13 — “harness comprising…a pair of shoulder straps”

104 Infa appears to contend that the requirement in claim 1 of each of the Fourth and Seventh Patents that the harness comprises “a pair of shoulder straps” (emphasis added) is not present in a Protecta Harness. It contended that a Protecta Harness, which its customers are expected to use with its Infa Products, is properly characterised as a single shoulder strap with a loop to allow for connection with a seatbelt.

105 Figures 1 to 4 of the Fourth and Seventh Patents depict a Protecta Harness. I agree with Mr Hunter that it is clear from those figures that such a harness has two shoulder straps each ending in a loop through which the seat belt is connected. I also agree with both experts’ conclusion in the Further Joint Expert Report that a Protecta Harness is so characterised, and falls within the relevant integers 4.1.9 and 7.1.9 in claim 1 of the Fourth and Seventh Patents.

106 Infa submitted that the pair of shoulder straps are not relevantly “connected at their lower end to said vehicle seat belt” :integers 4.1.10 and 7.1.10.

107 The reference to “lower end” must be read in context. In the context of the Fourth and Seventh Patent specifications, the claimed reference to “lower end” means the lower looped end of the pair of shoulder straps depicted and described, through which the vehicle seat belt is passed.

108 The Fourth and Seventh Patents depict the Protecta harness in figure 1, and state that “the lower end of each shoulder strap 21 is provided with a loop 24 to receive a vehicle seat belt”: see 5.22-4 of the Fourth Patent and 6.17-9 of the Seventh Patent. Therefore, notwithstanding the presence of an adjuster, the ends of the shoulder straps in the Innovation Patents are described and depicted as having a loop as in the Infa Products when used with a Protecta harness.

109 All of the Infa Products are within the scope of the relevant integers for the relevant claims.

110 Claim 3 of the Fifth Patent refers to a connection means which “further includes at the first end a latching hook connector” (emphasis added). As I found in the Construction Judgment (at [366]) and reiterated above in relation to topic 12, the connection means of the Fifth Patent includes the latching hook. On the basis of that construction, Infa contended that the qualifying words “further includes” of claim 3, as they relate to the “connection means” of claim 1, must require an additional “latching hook connector”, which additional latching hook connector is not present in the Infa Products.

111 It is to be recalled that in accordance with the Construction Judgment (at [317] and [366]) “connection means” is “any item or thing which would perform the function of connection”. In the context of the claims of the Fifth Patent, the words “further includes” is understood to limit the connection means to one in which a latching hook connector (and not any other connector) is used for securing the tether strap to the anchorage point. In my view, based upon Mr Hunter’s evidence it would be readily understood by the skilled addressee applying a practical sensibility to the patent, that integer 5.3.2 is not calling for multiple latching hook connectors in the one “connection means”.

112 In the Further Joint Expert Report, both experts agreed that all Infa Products utilised a latching hook as part of its connection means to secure the tether strap to the anchorage point. All of the relevant Infa Products are therefore within the scope of integer 5.3.2.

113 Integer 6.2.1 (in claim 2 of the Sixth Patent) refers to “a tethering means for a child safety seat for connection to an anchorage point in a motor vehicle” (emphasis added). Infa contended that the words “for connection” in that context imply that the “tethering means” does not itself include the components necessary “for connection”. This argument is consistent with its submission that “connection” must be direct, and therefore, while it accepted that the tethering means was securable via the latching hook of the connection means, such a connection was indirect, which, it submitted, was not claimed in the patents.

114 I reiterate my earlier comments about “connection” in topics 6, 7 and 9. The term “tethering means” is broad and can include more than the tether strap itself: see Construction Judgment at [380]. I add that integer 6.2.1 contains no such requirement or limitation on the “tethering means” as contended for by Infa. The words “for connection” in that integer simply qualify the antecedent “tethering means” as having (at least) the capability of “connection to an anchorage point on a motor vehicle”.

115 In the Further Joint Expert Report, both experts agreed that claim 2 of the Sixth Patent was infringed for all Infa Products. Mr Newman’s position in this regard was unchanged in his Fifth Affidavit.

116 On the basis of Mr Hunter’s evidence, I view the purpose (and certainly the capability) of the tethering means in all Infa Products to be for connection to an anchorage point in a motor vehicle, precisely as claimed in the patent. All of the relevant Infa Products are therefore within the scope of integer 6.2.1.

Topic 16 — “tethering means for tethering the backrest portion of the child safety seat”

117 Integer 7.3.7 (in claim 3 of the Seventh Patent) refers to “a connection means which is adapted to be secured at one end to the anchorage point”. Infa raised three arguments in relation to whether the Infa Products fall within the scope of this integer.

118 First, in his Fifth Affidavit, Mr Newman deposed in relation to Infa Products which have the Anchorage-Connection Arrangement version 1, that while those products contain a connection means (which he identified, in this context, as a particular buckle), it (ie the buckle itself) is not “adapted to be secured at one end to the anchorage point”.

119 Secondly, Infa submitted that in Versions 1b and 3, the tether strap passes through an opening in the latching hook connector and are therefore not relevantly “secured…to” via a direct connection as contended in topic 7.

120 Thirdly, Infa highlighted that integer 7.3.7 is preceded by the words: “a tethering means for tethering the backrest portion of the child safety seat and adapted to be secured at one end to the anchorage point”. It therefore contended that in the context of the claim, integer 7.3.7 requires an additional separate connection means, which is not present in Versions 4 and 5.

121 I will deal with each of these arguments in turn.

122 In the Construction Judgment I found that the term “connection means” as used in the Seventh Patent is not limited to a buckle (at [318] and [384]) and can include multiple components, including for example a latching hook, connecting strap and buckle.

123 A “connection means” comprising such components is adapted to be secured at one end to the anchorage point as required by the integer of the claim, and Mr Newman was not correct to limit the “connection means” of integer 7.3.7 to a particular buckle.

124 On the basis of my construction of the term “connection means”, the latching hook present in Versions 1b and 3 could be considered a part of the “connection means”, in which case the entire connection means will be directly “secured at one end to the anchorage point”, as illustrated by Mr Hunter.

125 However, direct securement is not required, and I do not read the integer as being so limited. In this regard, I reiterate my comments above in relation to topic 7. The latching hook present in Versions 1b and 3 may be considered part of intermediate componentry which ensures the required securement.

126 The specification does not limit or preclude the sharing of components between the “tethering means” and “connection means”: see Construction Judgment at [145]. Further, the Seventh Patent specification (at 4.23-5) states that:

[t]he connecting component which is connected to the vehicle anchorage point could then be shared by both the tether strap and child safety harness. There are, of course, other ways in which a component may be shared.

127 Accordingly, a component can simultaneously constitute part of the “tethering means”, and the “connection means”. Claim 3 of the Seventh Patent includes within its scope arrangements such as Versions 4 and 5 wherein the latching hook may be characterised as “shared” between the “tethering means” and the “connection means”. In those Versions, the “connection means” is therefore “adapted to be secured at one end to the anchorage point”, as required.

128 All of the relevant Infa Products are therefore within the scope of integer 7.3.7.

129 Integer 7.3.9 refers to a connection means “having a second aperture through which the tethering means locates”. Infa contended on the basis of Mr Newman’s evidence that Infa Product Anchorage-Connection Arrangement version 1 (and presumably 1b) lacks the relevant second aperture.

130 Mr Newman’s view was based on Mr Newman’s identification of the “connection means” as a particular buckle. For reasons given in relation to topic 16, this is not correct.

131 Further, as I noted in topic 16 and in the Construction Judgment (see [384]), the “connection means” may have multiple components, including the connection strap. The connection strap in Version 1 (and 1b) contains an opening through which the tether strap passes. Therefore the “connecting means” of Version 1 (and 1b) contains the required “second aperture through which the tethering means locates”.

132 In the Further Joint Expert Report, Mr Newman and Mr Hunter agreed that claim 3 of the Seventh Patent was infringed for all Infa Products. All of the relevant Infa Products are within the scope of integer 7.3.9.

Topic 18 —“substantially as illustrated” (the “flat plate” as a “major improvement”)

133 Claims 2 and 3 of the Eighth Patent refer to an apparatus or child safety seat and harness “substantially as…illustrated in…figures [4 to 9]”. Claims 4 and 5 of that Patent similarly refer to “substantially as…illustrated in the accompanying drawings”.

134 Infa submitted that figures 6 and 7 of the Eighth Patent are substantially different to the others, in that they do not contain the flexible strap (44) and buckle (45) arrangement. Rather, figures 6 and 7 depict a “flat plate” (48) which contains its own latching hook and an aperture for the tether strap, and to which a harness latching hook is or can be connected. Mr Newman viewed the use of the “flat plate” as a “major improvement” in that the more rigid connection prevents the connection aperture for the harness from falling away or becoming difficult to locate. This was not accepted by Mr Hunter. However, as Britax correctly submitted, a difference in the figures is irrelevant for the purposes of determining whether or not a particular article infringes one or other of the figures referred to in the omnibus claim

135 Infa further contended that figures 4 and 5 depict connection points (41) and (42) which are not present in those Infa Products in which the tether strap is connected to the seat through intermediary webbing loops.

136 Both of these issues concern the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent, and are relevant to the omnibus claims issue in topic 23, to which I will return. However, I will consider the specific issue raised in relation to this topic here.

137 Britax contended that in any event, the Infa approach as to the infringement of the Eighth Patent is flawed as it ignores the embodiment depicted in figure 6 as described in the Eighth Patent. I accept this submission. Figure 6 of the Eighth Patent contemplates a metal connecting component that connects the harness and tether strap to the vehicle anchorage point. Therefore, as contended by Britax, such a single metal plate is included within the scope of figure 6 of the Eighth Patent.

138 I add that Infa Product Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 3 to 5 contain such a flat plate which is “substantially as illustrated” in figures 6 and 7, whilst Versions 1 and 1b contain an arrangement “substantially as illustrated” in figures 4, 5, 8 and 9. All Infa Products therefore fall within the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent.

139 In relation to the connection points, in my view, the purpose of the embodiment of the connection points in figures 4 and 5, is to depict the securing of the backrest via two mutually spaced connection points. I agree with Mr Hunter that all Infa Products involve “substantially” the same arrangement, regardless of whether they utilise loops or grooves on the head end of the back rest. Mr Hunter was of the view, as a person skilled in the art, that any variation in the Infa Products was minor.

140 All Infa Products therefore fall within the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent.

Topic 19 — “anchorage locations” (Tenth Patent)

141 Claims 1 and 19 of the Tenth Patent refer to the “first and second mutually spaced anchorage locations on said head end of said backrest” and describe a tether strap “with one end extending from said first anchorage location…to said second anchorage location”.

142 Infa submitted that there are more than two “anchorage locations” on many of the Infa Products, and therefore those products do not fall within this claim.

143 Infa’s submission is at odds with my Construction Judgment where I found that the meaning of “anchorage locations” did not preclude circumstances where there were more than two anchorage locations: at [402]. A product having more than two anchorage locations does not escape the scope of these claims.

144 In the words of the Construction Judgment at [401] the term “anchorage location” only requires “a location or position at which there is a contrivance (that is, a design feature) which holds fast, or gives security to, the seat and occupant in the event of sudden movement or deceleration”. Such a “contrivance” need not be an aperture, as depicted in figures 4 and 5. It can, for example, include a feature in which the tether strap “sits” in grooves in the perimeter of the seat (as in Version 5 on CS53 and CS54), or a feature wherein the tether strap passes through “loops” (as in the other Versions of CS53 and CS54).

145 In each of the Infa Products, there are at least two such “contrivances” located on the head end of the backrest “which holds fast, or gives security to, the seat and occupant in the event of sudden movement or deceleration”: Construction Judgment at [401]. The requirement that contrivance “holds fast, or gives security” does not necessarily mean that it bears any load “in the event of sudden movement or deceleration”. It simply means that the anchorage location plays a role in ensuring that the seat remains connected to the anchorage point on the vehicle. Mr Newman failed to appreciate this construction in his oral evidence before the Court on 18 February 2014, when he argued that the entire back portion of CS53v4 (for example) provided a single anchorage location, or bore the relevant load, since if the “loops” were to be cut, those “contrivances” could be rendered useless for anchorage.

146 Infa also contended that the “mutually spaced anchorage locations” are not on “said head end of said backrest” on the basis of the issues raised in topic 11. I reiterate my comments in relation to that topic, and note the Construction Judgment at [399]. Even in an uninstalled state, as Mr Hunter demonstrated with CS53v4, the relevant loops “revert to a fairly well defined point” or location on the head end of the backrest.

147 All Infa Products contain (at least) two mutually spaced anchorage locations on the “head end of said backrest” described by claims 1 and 19 of the Tenth Patent, as agreed by both experts in the Further Joint Expert Report.

148 All of the relevant Infa Products are therefore within the scope of the relevant integers for the relevant claims.

Topic 20 — “end” (Tenth Patent)

149 In relation to the same claims as detailed in topic 19 above, Infa contended that the Infa Products do not have such a feature, because in those products the physical end of the tether strap (ie where it terminates) does not “extend from” any anchorage location. Rather, it submitted, the tether straps of the Infa Products either travel in a circuit (having an adjuster in that circuit), or through other loops.

150 Infa’s submission is based on my finding of the meaning of the term “ends” in the Construction Judgment: see, eg, at [300-1]. However, that finding was in relation to the First Patent, and specifically adopted (at [340]) in relation to the Third Patent. The construction determination for any term cannot simply be transposed or applied to an asserted equivalent term outside of the context in which it was specifically contested and construed.

151 The context of claims 1 and 19 of the Tenth Patent is different to that of the First and Third Patents. The term “end” in this context is not used in the sense of the physical termination points. Rather it means the part of the tether strap which “commences” at the first anchorage location, and which tether strap then extends in a loop from that first anchorage location (through the strap opening) to a second anchorage location. The embodiments in the Tenth Patent reinforce this interpretation — neither of them depict an arrangement as contended by Infa.

152 I note that in construing the terms of a patent claim, clear language is not to be changed, and the Court must take a common sense approach so as to avoid a surprising or absurd result. Care must also be taken not to take into account the alleged infringing product in construing the claim. In arriving at the above construction of the word “end” in the Tenth Patent, I have adopted the same process of construction as with the First and Third Patents, and have applied the ordinary meaning of the word to a specific context.

153 Infa submitted that the construction of the term “end” in the context of claims 1 and 19 of the Tenth Patent, should be informed by the deliberate introduction (after the Tenth Patent was laid open for inspection on 15 February 1996) of the phrases “with one end” and “with the other end extending” and the reordering of the text of the claims. Infa submitted that in order to obtain the grant of the patent, Britax amended the claims to make express the requirement that the ends of the tether strap be its physical ends. However, in my view, that amendment does not impact upon the proper construction I have given to the Tenth Patent.

154 All of the relevant Infa Products are within the scope of the relevant integers for the relevant claims of the Tenth Patent.

Topic 21 — forward or rearward facing (Tenth Patent)

155 Claim 20 of the Tenth Patent refers to a safety seat “substantially as hereinbefore described with reference to and as illustrated in the accompanying drawings”. Infa submitted that the Infa Products are not within the scope of this omnibus claim, because figure 2 of the Tenth Patent depicts a rearward facing safety seat, which is not a feature present in the Infa Products.

156 This submission takes too literal a view of the Patent’s embodiments. The Tenth Patent is not about forward or rearward facing seats per se. It is, as Mr Hunter noted as the skilled addressee reading the Tenth Patent through the application of common sense and common general knowledge:

primarily about a split tether strap which may be used either with a forward facing seat or with a rearward facing seat, or with a seat that has the capability of being reversed to be either forward or rearward facing.

157 Further, it is only figure 2 in which a rearward facing seat is depicted; in figures 1, and 3 to 11 of the Tenth Patent, all of the seats are depicted as forward facing.

158 Mr Newman and Mr Hunter in the Further Joint Expert Report agreed that Versions 1, 1b and 3 of CS53 and CS54, and Versions 3,4 and 5 of CS55 fell within the scope of omnibus claim 20 of the Tenth Patent.

159 In my view, on the basis of Mr Hunter’s evidence, all Infa Products involve a forward facing arrangement which uses a split tether strap and are “substantially…as illustrated” (emphasis added) in figures 1 to 11 of the Tenth Patent. They therefore fall within the scope of integer 10.20.1.

160 This was not described as a “topic” identified by the parties, but it is appropriate to deal with it here as if it were.

161 Different views were expressed in the Further Joint Expert Report on the interpretation to be given to the term “body” of the connector as it appears in claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Ninth Patent.

162 In my view, the term “body” in claim 1 (integer 9.1.3) is further defined by the additional integers being “a connection means…a first aperture…and a second aperture…”: integers 9.1.4-6. The context and wording of the integers themselves indicate that conclusion. The integers following the word “body” refer to “at one end of the body” and “in the body”.

163 The experts agreed that if this interpretation is correct, Version 4 of CS53, CS54 and CS55, and Version 5 of CS53 and CS57 fall within the scope of claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Ninth Patent.

164 On the basis of my construction, the agreed position of the two experts in the Further Joint Expert Report is that the Infa Products with Versions 4 and 5 are within the scope of claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Ninth Patent. I agree with that conclusion.

165 I now turn to the omnibus claims to the extent I have not dealt with them under the foregoing specific topics.

166 I have already made observations about the omnibus claims in Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 1019 (‘Omnibus Judgment’) at [23–44]. I will not repeat them.

167 I do stress that the construction of the omnibus claims depends on the context and the precise language used. Whilst the omnibus claims in this proceeding do vary in their precise language, I proceed on the basis that the relevant reference in the omnibus claims is to the figures or drawings. However, the figures or drawings must be viewed in the context of the specification and through the eyes of the skilled addressee taking a practical approach to what the figures or drawings describe. Each claim describes something actually shown in the figures or drawings, subject to variations that a person skilled in the art would regard as minor or not substantial.

168 Where the reference is to one or more figures, which are identified, I treat this as a claim which is notionally separable into a number of claims, each of which makes reference to only one example, the scope of which is limited by reference to that specific example: see eg Williams Advanced Materials Inc v Target Technology Co LLC (2004) 63 IPR 645 at [57].

169 The omnibus claims in issue in the proceeding and which Britax asserts are infringed by the various Infa Products are:

(a) Sixth Patent — claim 4;

(b) Eighth Patent — claims 2, 3, 4 and 5; and

(c) Tenth Patent — claim 20.

170 In the Further Joint Expert Report, the experts agreed on the presence of all integers in many of the Infa Products for many of the omnibus claims. Hence, the combined construction and infringement issues had crystallised into a consideration of a confined set of Infa Products for each of the above identified claims of the Sixth, Eighth and Tenth Patents.

Sixth Patent — Omnibus claim 4

171 The Sixth Patent is concerned with various tether strap arrangements enabling connection of a harness and child safety seat to a single anchorage point on a motor vehicle. The claims describe and the figures depict various tethering means and connection arrangements. Although omnibus claim 4 is directed to a tether strap, the reference made to the drawings relates to the connection means.

172 Specifically, the claimed tether strap of claim 4 is described as:

(a) incorporating “means for connecting both the tether strap and a child safety harness used with the safety seat to an anchorage point of the vehicle”; and

(b) in a manner which is “substantially as herein described and with reference to the accompanying drawings” (that is, figures 1 to 9).

173 To establish infringement, the infringing product must contain all the essential features described and claimed. However, there is no escaping infringement by either or both of the substitution of “mechanical equivalents” which make no essential difference to the way that the invention performs; or the presence of immaterial variations to the essential features of the described and claimed invention, or as illustrated in the drawings: see, eg, Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd (1982) 41 ALR 471, 475-6.

174 As Britax contended, context is important. In the context of omnibus claim 4 of the Sixth Patent, the following aspects are all relevant:

(a) the Background of the Invention (page 2);

(b) the Summary of the Invention including the consistory clauses describing “aspects” of the invention (pages 2 - 4);

(c) the description of the embodiments of the invention depicted in the accompanying drawings (pages 4-5);

(d) the embodiments illustrated in the accompanying drawings (figures 4-9) which make clear that there are separate drawings (and embodiments) each of which must be individually considered;

(e) the descriptions of the preferred embodiment (pages 5-8); and

(f) the statement that “the invention is not limited to the embodiments disclosed” (page 8).

Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 4 and 5

175 Mr Newman gave evidence that Versions 4 and 5 were not within the scope of this omnibus claim. This was due to the absence in the drawings of the “flexibly” linked metal components, namely the latching hook and connection plate, which were present in Versions 4 and 5.

176 I consider that Mr Newman was basing his differentiation solely on his literal interpretation of the drawings. I consider this to be a narrow, and incorrect, approach. In my view, it is relevant for infringement that the relevant product function in the way described or depicted. In the context of an omnibus claim, it is relevant that the product function substantially in the way described or depicted.

177 Mr Hunter noted that figure 6 depicts an embodiment in which of the connection functions in the same way as seen in Versions 4 and 5. This is the correct approach, and I accept this evidence.

178 The connection means arrangement of Versions 4 and 5 has all of the features of the substance of the innovative concept embodied in figure 6 of the Sixth Patent. Both have a flat plate portion, an aperture (or “U”-shaped end) through which the tether strap locates, and another aperture for connection of a child safety harness. In concept, Versions 4 and 5, contain substantially the same essential components as are present in figure 6 of the Sixth Patent.

179 The separate latching hook used in Versions 4 and 5 is a variation which Mr Hunter, as a skilled addressee, viewed as “minor”, and adds no functionality or utility to the embodiment depicted in figure 6. Versions 4 and 5 therefore fall within the scope of integer 6.4.3 of claim 4 of the Sixth Patent.

Eighth Patent — Omnibus claims 2, 3, 4 and 5

180 Like the Sixth Patent, the Eighth Patent is concerned with various arrangements for connecting a child safety seat and a child safety harness to a single anchorage point on a motor vehicle. The claims describe and the figures depict various tethering means and connection arrangements. I have described these claims in topic 18 above and in the Omnibus Judgment at [34].

181 Specifically, the omnibus claims are directed either to:

(a) an “[a]pparatus to secure a child safety seat and child safety harness to a single anchorage point on a motor vehicle” (claims 2 and 5); or

(b) a “child safety seat and child safety harness adapted to be secured to a single anchorage point on a motor vehicle ...” (claims 3 and 4);

in a manner which is substantially as hereinbefore described and illustrated in:

(a) any one of figures 4 and 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 (claims 2 and 3); or

(b) the accompanying drawings (claims 4 and 5).

182 In context of omnibus claims 2, 3 4 and 5 of the Eighth Patent, the following aspects are all relevant:

(a) the Background of the Invention (page 2);

(b) the Summary of the Invention including the consistory clauses describing “aspects” of the invention (pages 2- 4);

(c) the descriptions of the embodiments of the invention depicted in the accompanying drawings (pages 4-5);

(d) the embodiments illustrated in the accompanying drawings (figures 4-9) which make clear that there are separate drawings (and embodiments), each of which must be individually considered;

(e) the description of the preferred embodiment (pages 5-8); and

(f) the specific statement (on pages 7-8) that the description in relation to the preferred embodiments:

…is not limited to the above described embodiments disclosed, but is capable of numerous rearrangements, modifications and substitutions without departing from the scope of the invention. For instance, it is not necessary that the latching hook connector and connection means be a single component but may include two or more connected components to achieve the same result. Other modifications and variations such as would be apparent to a skilled addressee are deemed within the scope of the present invention.

183 As with the Sixth Patent, I consider Mr Newman was basing his position upon too restrictive an approach to the drawings. Mr Newman failed to bring into consideration the entirety of the description in his perception of the drawings, and also failed also to see them in the context of the various aspects of the invention (pages 2-4) and the preferred embodiments.

184 Similar comments to those made in relation to the Sixth Patent apply to the features of the Eighth Patent.

Anchorage-Connection Arrangement version 1

185 Infa contended on the basis of Mr Newman’s evidence, that the interrelationship of the tether strap and the connection strap in respect to the latching hook in Version 1 is not reflected in any of the figures in the Eighth Patent. However, Mr Newman accepted that Version 1b is within the scope of the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent. In particular, Mr Newman’s concern with Version 1 is based on the perpendicular or nonlinear arrangement of the tether strap with respect to the connection strap, as opposed to the relatively linear arrangement of components depicted in the patent.

186 However, that is only an issue of orientation which does not impact upon the “substance” of the componentry described in the Patent. I accept Mr Hunter’s evidence that there is no relevant difference in function between Version 1 and the embodiments depicted in the Eighth Patent. In my view, based on Mr Hunter’s evidence, the perpendicular placement of the tether strap in Version 1 is a variation which a skilled addressee would view as minor, and adds no functionality or utility to the embodiment depicted in figures 4 to 9. Version 1 therefore falls within the scope of the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent.

Anchorage-Connection Arrangement versions 4 and 5

187 Mr Newman stated that Versions 4 and 5 were not within the scope of the omnibus claims of the Eighth Patent for the same reasons as he gave in relation to the omnibus claims of the Sixth Patent, namely that the patent embodiments do not depict the “flexibly” linked metal components found in Versions 4 and 5.

188 I reiterate my comments above in relation to the omnibus claims of Sixth Patent. The connection means arrangement of Versions 4 and 5 has all of the features of the substance of the innovative concept embodied in figure 6 of the Eighth Patent, and the additional feature is immaterial to the question of infringement for the same reasons stated above.

189 All Infa Products therefore fall within the scope of claims 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the Eighth Patent.

Tenth Patent — Omnibus claim 20