FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 234

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

First Applicant JACK GANCE Second Applicant | |

|

AND: |

DIRECT CHEMIST OUTLET PTY LTD (ACN 123 831 210) First Respondent IAN TAUMAN Second Respondent |

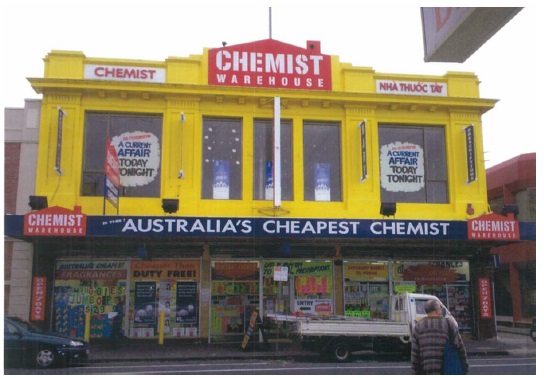

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4.00 pm on 27 March 2015, the parties confer and file and serve a joint minute of orders reflecting these reasons (including as to costs), or in the event of disagreement, a separate minute of order with short written submissions in support thereof.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 781 of 2013 |

|

BETWEEN: |

MARIO VERROCCHI First Applicant JACK GANCE Second Applicant |

|

AND: |

DIRECT CHEMIST OUTLET PTY LTD (ACN 123 831 210) First Respondent IAN TAUMAN Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

MIDDLETON J |

|

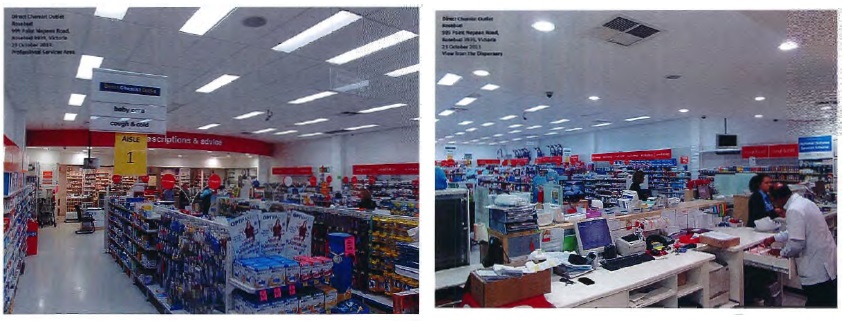

DATE: |

17 MARCH 2015 |

|

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding the Applicants, Mr Mario Verrocchi and Mr Jack Gance, primarily bring claims for breach of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (‘the TPA’) and s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (‘the ACL’) being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘the CCA’), and claims for trade mark infringement, against the Respondents, Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd (‘DCO’) and Mr Ian Tauman.

2 Specifically, the Applicants (trading as Chemist Warehouse) primarily allege that since 26 May 2006:

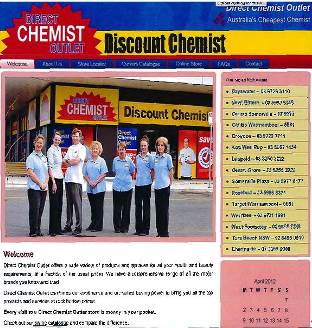

(a) the Respondents have adopted a get-up for their stores, catalogues and website, in association with the descriptive and non-distinctive name “Direct Chemist Outlet” which has caused and is likely to cause consumers to believe that the Respondents’ pharmacies are either those of the Applicants, or are associated or affiliated with the Applicants’ pharmacy chain;

(b) the Respondents have failed to take any step to adequately distinguish themselves from the Applicants’ business, and have intentionally copied various visual attributes of the Applicants’ marketing and business so as to further consumers’ misconception;

(c) as a result of the Respondents’ conduct, consumers have been or are likely to have been misled or deceived and subject to false representations that, when the consumers receive a DCO catalogue, attend a DCO store, or visit the DCO website, they are either engaged in dealing with Chemist Warehouse or a pharmacy associated with that chain; and

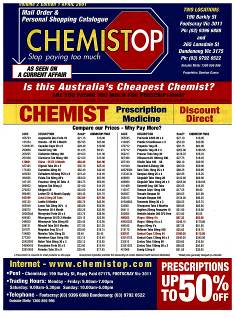

(d) the Respondents have infringed the Applicants’ registered trade mark which contains the slogan “Is this Australia’s Cheapest Chemist?”.

3 Other claims are brought by the Applicants pursuant to provisions of the TPA and CCA, and passing off, but the primary basis of the claims of the Applicants is as set out above.

4 In the circumstances of this proceeding, the reliance by the Applicants on s 53 of the TPA and s 29 of the ACL, and the tort of passing off, add nothing to the basis on which the Applicants could obtain relief. My findings in relation to s 52 of the TPA and s 18 of the ACL will equally determine the claims under the other statutory provisions and in relation to the passing off claim.

5 This proceeding primarily raises issues concerned with the trade indicia of retail stores (in conjunction with the use of catalogues, advertising materials and websites) and the extent to which one trader may effectively obtain a form of de facto monopoly over such indicia.

6 At the outset I make some observations.

7 First, I accept that branding, as a concept, is of great importance and significance in a business model. Where colour is used as a key branding element, it is not to be regarded as a trivial or insignificant component of the brand concept. Consumers will often quickly register the colour or colours used in branding, and will often retain a conscious or subconscious recognition and association of a colour or colours with a particular brand. From the business’s perspective, any visual impact of its branding (including colour) is often intentional and important.

8 In this proceeding, the competing parties make heavy use of colour in the branding and promotion of their stores. However, as the Applicants correctly contended, it is important not to “over-intellectualize the likely analysis of the consumer” in undertaking the relevant legal assessment of the possible consumer responses to the branding of competitors. Further, I am mindful that the relevant consumer’s likely analysis would not involve the viewing and side-by-side comparison of all the photographs put into evidence in this proceeding; rather the consumer’s analysis will be governed by an overall impression of colours in combination with other branding features, including the relevant (and dominant) logo in situ.

9 While colours are generally useful in branding for ornamentation or decoration, some colours are known to perform a specific marketing function. For example, the colour yellow provides high visibility, and is therefore used in street and roadwork signs. When used on storefronts, it can similarly attract attention to the store. Justice Mansfield in Philmac Pty Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks (2002) 126 FCR 525 noted at [54] that:

…a trader might legitimately choose a colour for its practical utility. That is, the colour may be a feature of a product that serves to improve the functionality or durability of the product. The function of visibility is, for example, served by the colour yellow; heat absorption by the colour black; light reflection by the colour white; military camouflage by a combination of khaki, brown and green. …

10 The external get-up of Chemist Warehouse is, as submitted by the Applicants, “highly prominent, loud and garish and prone to be noticed by potential consumers… especially in the context of the busy high street and shopping centre environments in which the stores trade”.

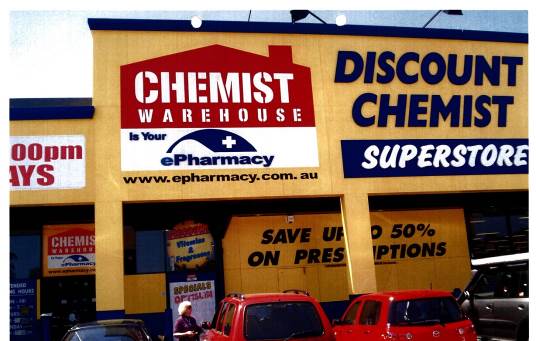

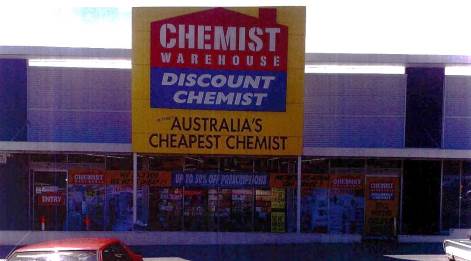

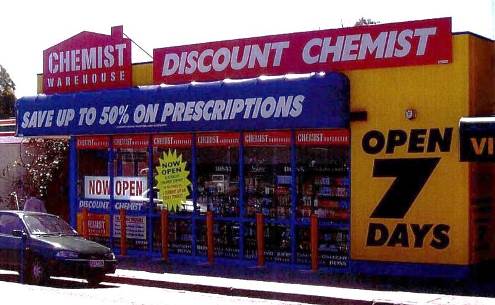

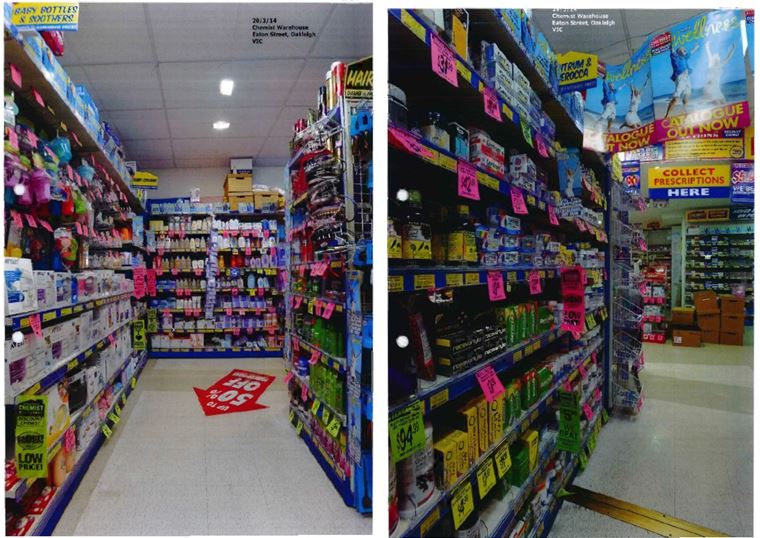

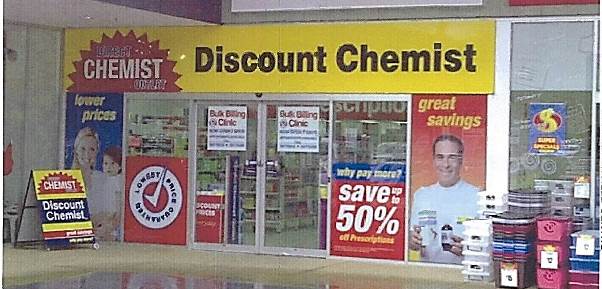

11 Examples of predominantly yellow storefronts include the following:

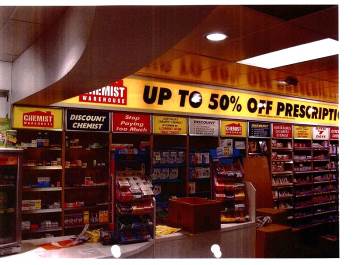

12 The colour yellow can also be used to denote a value proposition. A number of discount retailers (including discount chemists) use that colour as part of their storefront and many retailers use yellow to promote sales. The prominent, loud and garish use of yellow imparts the look and feel of “cheapness”, or heavily discounted goods or services. One such example is shown below:

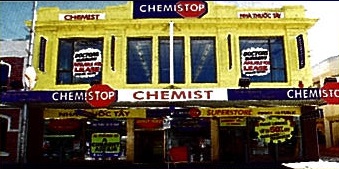

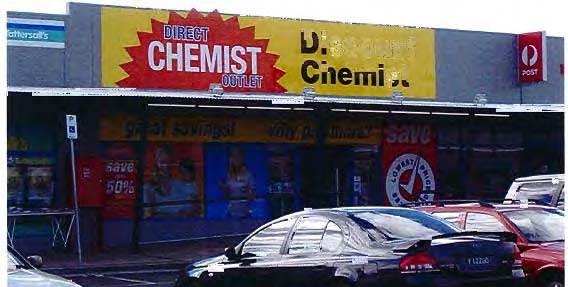

13 Examples of discount chemists which employ a predominant use of yellow on their storefronts include the following:

14 The Applicants contended that the Respondents do not need to use yellow to operate a successful discount chemist. While this may be true, the Respondents may wish to use this colour to take advantage of the two attributes mentioned above, namely visibility and the discount value proposition, which are both understandably desirable attributes for any discount store, including a chemist.

15 Secondly, during the hearing an inspection was undertaken of certain stores the subject of this proceeding in order to assist the Court in understanding the evidence and the photographic evidence in particular. Section 54 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) enables the court to draw any reasonable inference from what is seen during an inspection, but the parties agreed that the object of the inspection was as I have just indicated. During the inspection I observed that, as is common experience, a customer’s perception of the look or get-up of a store depends on the direction from which one approaches or views a store. For example, passing a store in a car, or from across the road, gives a quite different impression from that when one views a store from close up, or approaches a store (say, from an adjacent store) and therefore only sees the windows and entrance, and not the parts of the building near the roof-line.

16 Thirdly, it is important to recall that confusion of consumers or potential consumers is not enough to establish liability under the TPA or the ACL. A consumer may recognise a similarity in the range of colours used by both the Applicants and Respondents in their branding, the extent of which will depend on the particular consumer’s familiarity with Applicants’ or the Respondents’ stores, catalogues or websites. Further, most retail catalogues (whether for pharmacies or otherwise) have essentially common features, and are produced to show the breadth of product range and to solicit customers (in the case of discount chemists, by drawing attention to low priced or discounted items offered for sale). There is no distinctive consistency of appearance in either of the parties’ catalogues. Further, the websites of the parties are quite different, and the appearance of the Applicants’ website varied substantially over time. The main focus of this proceeding is upon the stores, and their external get-up in particular. Admittedly, reference is made in the Chemist Warehouse catalogues and website to the Chemist Warehouse stores, but not by reference to the whole of the get-up of the Chemist Warehouse store as relied upon by the Applicants.

17 Fourthly, the Respondents undoubtedly copied many of the ideas and concepts of the Applicants, including some elements of the get-up and aspects of store display. While the Respondents liked and used aspects of the Applicants’ marketing concept, I have reached the view that they did not do so with an intention to mislead or deceive consumers, or to pass off their stores as those of (or associated with) the Applicants, nor did they adopt those elements uniformly. Further, the Respondents in my view sufficiently distinguished their chemists from those of the Applicants.

18 Fifthly, if not for my ultimate finding in this proceeding, it may have been necessary to make findings as to the reputation of Chemist Warehouse on a geographical or territorial basis. The existence or strength of any reputation that Chemist Warehouse had at a particular point in time would inevitably vary between geographical areas, as it commenced operation and promotion in certain areas much later than when it first commenced operating using the get-up relied upon in this proceeding.

19 If I were to consider this using a geographical analysis, the Applicants would still need to establish that it was the Respondents’ actions that caused any likelihood of deception within each geographic area. This may mean that if the Applicants had set up a store in a particular area already (or previously) occupied by a DCO store, then the Applicants may not rightly complain of any “confusion” in that area being caused by the Respondents. The Applicants did not adduce any specific evidence directed to establishing reputation on a geographical basis.

20 Further, if a geographical approach was taken, the Court may have needed to restrict relief to particular areas, or to modify the relief granted. The Court would require evidence of the current position at the date of trial, so as to determine the appropriate injunctive relief to grant in order to be fair to each party and to avoid stifling lawful competition. After all, injunctive relief should be limited to what is necessary in the circumstances of the particular case: see, eg, Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 (‘Campomar’) at [111].

21 Submissions were also put before the Court on the question of determining the relevant date of the commencement of the impugned conduct where a respondent gradually expands its business into new districts or geographic area in which an applicant operates. In addition to the reasoning of Yates J in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 275 ALR 526 (‘Optical 88’), the Applicants made reference to some observations of Allsop J (as he then was) in Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd v Q & Q Global Enterprise (2004) 61 IPR 98 at [125] and of Moore J in Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd v Gymboree Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 166 at [129].

22 The Applicants’ “primary submission” was that the date for assessing conduct should be 26 May 2006, when the impugned conduct began. However, the Applicants submitted that it may be more appropriate to consider the reputation of the Applicants as at the date that the Respondents commenced business in a new area, given the localised nature of the pharmacy operators and marketing.

23 The Applicants in their submissions (seemingly in the alternate) also invited the Court to take a geographical approach and treat the relevant date for assessing the Applicants’ reputation as at the opening of each DCO store, unless the new DCO store opened relatively close to an existing store.

24 However, if the Applicants and Respondents were concurrently trading and building independent reputations in separate areas, it may have been the case that it was not the Respondents’ conduct that was misleading or deceptive at that later time.

25 For example, the Lalor DCO store opened in 2014, well after 26 May 2006. Both parties had advanced their own reputations by that time. What is the Court to conclude is the position of the competing parties in that particular area and at that particular time? It is to be recalled that since 26 May 2006 both businesses involved in this proceeding have increased their respective exposure to the relevant consumers by opening many new stores. There has been co-existence in the market place for approximately eight years prior to litigation commencing. Further, stores have opened in numerous locations, and Chemist Warehouse stores have opened in close proximity to existing DCO stores (as in the case of the Warrnambool store, for example).

26 In any event, on the basis of the view I have reached that DCO stores adequately distinguish themselves from Chemist Warehouse stores so as not to mislead consumers, even if one took the later date in Lalor (for example), this would not result in liability attaching to the Respondents. The relevant consumers in Lalor (for example) would not be misled as they would appreciate the difference between the two pharmacy outlets. There is also evidence to suggest that in the years between 26 May 2006 and 2014, the Applicants made even more prominent use of the Chemist Warehouse logo so as to distinguish itself from DCO.

27 I have come to the view that in this proceeding, even if the Court was to take a geographical approach as suggested by the Applicants, and assess Chemist Warehouse’s reputation in each particular area as at the date on which a DCO store opened in that area, the result would not be any different.

28 Sixthly, the Applicants did not seek to rely upon any trade mark for the overall get-up of their stores, or the branding of their catalogues or website. Instead, the Applicants rely upon their claims of misleading or deceptive conduct to obtain relief restraining the Respondents from adopting a get-up (and colour scheme in particular) for their stores, catalogues and website.

29 Seventhly, as the Applicants accept, this is not a proceeding concerned with a single colour (yellow), but the use of a palette of three primary colours (yellow, blue and red), in combination with a red logo with white text, and the use of descriptive discount slogans.

30 In the context of the misleading or deceptive conduct claim (and passing off), the Applicants rely in part on the relevant consumers having come to recognise or appreciate that those particular visual branding devices have become associated with the Applicants’ business.

31 Normally the trade indicia of the stores would need to be somehow distinctive so that consumers would come to associate them with the Chemist Warehouse business — if it were the same or similar as other retail outlets it is difficult to see how the relevant consumers could come to associate the trade indicia with a particular trader.

32 In this proceeding, the evidence discloses insufficient uniformity in the visual branding devices relied upon by the Applicants to support a claim for misleading or deceptive conduct against the Respondents. There is no sufficiently common identity in the design and layout to give rise to an unusual or distinctive store get-up (or catalogue or website design) associated with the Applicants. In addition, the Respondents have sufficiently distinguished the trade indicia of their stores, so that the logo, colours and physical appearance of their stores, catalogues and website, would not mislead or deceive, or be likely to mislead or deceive, the relevant consumers.

33 I make one specific comment on the Applicants’ reliance on the cumulative reputational effect of the get-up of the stores, catalogues and website. There was no actual or intended uniformity between these three forms of promotion by the Applicants; the use of colour, font and layout differs materially between them. The one constant was the Chemist Warehouse logo, which was a uniform and primary focus in all forms of promotion. No Chemist Warehouse store would have been opened without the prominent use of the vibrant red logo, which includes the words “Chemist Warehouse”, and it was this logo which communicated the Applicants’ brand to the relevant consumers.

34 Finally, if I had found that the exteriors of Chemist Warehouse and DCO stores were sufficiently similar, the difference in their interiors would not mitigate the Respondents’ liability. However, it may have been relevant as to the relief the Court would grant to the Applicants.

35 Whilst a consumer may intend to visit a particular pharmacy, he or she is ultimately concerned with purchasing a particular product, and possibly at a discounted price. Once inside the discount pharmacy, even if the consumer discovers that he or she was misled as to the brand by the exterior get-up, the consumer is likely to proceed to purchase the desired product.

36 As will be apparent, I have reached the view that the interiors of the parties’ stores are sufficiently different, to the extent that consumers would not be misled or deceived on the basis pleaded by the Applicants in this proceeding. Nevertheless, if the Respondents had misled consumers only by their storefront get-up, I would have concluded that such customers would have already been enticed into the “marketing web” of the Respondents.

37 Having made these observations, I now briefly outline the relief sought by the Applicants.

38 The Applicants seek orders restraining the Respondents from using a get-up on stores, catalogues and websites in the conduct of their discount pharmacy business which is deceptively similar or substantially identical to the Applicants’ stores, catalogues and websites. More particularly, the Applicants towards the end of the hearing sought orders in the following form:

Each of the Respondents, whether by themselves, their employees, servants, agents, representatives, licensees or otherwise be restrained from:

(a) displaying an external get up on any pharmacy that is substantially identical, or deceptively similar, to the external get up of either of the Chemist Warehouse pharmacies depicted in Annexure A;

(b) publishing or distributing catalogues for any pharmacy displaying a get up that is substantially identical, or deceptively similar, to any of the Chemist Warehouse catalogues depicted in Annexure B; or

(c) publishing a website displaying a get up that is substantially identical, or deceptively similar, to the Chemist Warehouse website depicted in Annexure C;

(d) otherwise marketing a pharmacy with a get up predominantly comprising the background colours red, yellow and blue and a red logo with white writing.

(e) using a sign that is substantially identical, or deceptively similar, to Australian Registered Trade Mark No 1195650, including a sign comprising the words “Who is? Australia’s Cheapest Chemist”, as a trade mark in respect of any:

(i) retailing, online retailing or mail ordering services, relating to pharmacies;

(ii) medical, hygienic or beauty care services, relating to pharmacies and being pharmacy advisory and pharmacy dispensary services.

…

39 The Annexures referred to above included examples of Chemist Warehouse stores, catalogues and website.

40 There are some difficulties with that form of order in this proceeding. This is because the evidence in this proceeding shows that, for example in relation to the storefronts, their appearance since 26 May 2006 has not constituted a uniform appearance that could be said to comprise the get-up of the Applicants at any relevant date. At best there was some consistency in the use of bright and primary colours (including yellow), and the “Chemist Warehouse” logo. The various DCO stores also lacked a sufficiently consistent appearance, so that it would be difficult to precisely identify which DCO stores were deceptively similar to the two storefront examples annexed to the Applicants’ proposed orders, assuming those examples were indeed the “best” depiction of the Applicants’ storefront get-up. Similar issues arise in relation to the catalogues and the website.

41 Just as goods of different manufacturers may innocuously bear some resemblance to each other, so too will retail stores and the use of colours that have a functional element. Where such a legitimate resemblance occurs, then marks, labels and other unique branding will be significant in distinguishing competitors. Whilst there is no evidence in this proceeding on this topic, I perceive that consumers are alive to imitation and, if important to their own purchase decision, will seek out the distinguishing branding. In the discount chemist context, the consumer is likely to be interested in obtaining a cheaper item than at traditional chemists. This is not to say a consumer may not be concerned about the particular brand of discount chemist from which he or she purchases, or its associations with other businesses; but, the consumer is primarily concerned with the price or discount.

42 In making the above comment, I am mindful that it is sufficient if some form of association or connection is conveyed by the impugned conduct, although the precise form of association or connection may not be able to be articulated or identified: see, eg, Telstra Corp Ltd v Royal Sun Alliance Insurance Australia Ltd (2003) 57 IPR 453 at [76] and see generally Pacific Dunlop Ltd v Hogan (1989) 23 FCR 553 (‘Pacific Dunlop’).

43 Finally, the Applicants sought damages for loss caused by the Respondents’ conduct.

44 The Respondents, by cross claim challenge the validity of the Applicants’ trade mark pursuant to s 88 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (‘the TM Act’).

45 I ordered that issues of liability and quantum were to be heard separately. These reasons are solely concerned with liability.

THE APPLICANTS

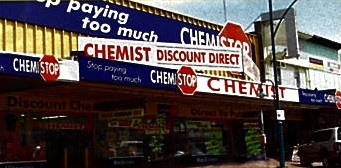

46 Messrs Verrocchi and Gance are both registered pharmacists. Together with Messrs Samuel and Damien Gance they began developing their discount pharmacy concept from late 1999 and launched their first discount pharmacy store called “Chemi Stop” in Footscray, Victoria on 15 June 2000. The name “Chemi Stop” was subsequently changed to “Chemist Warehouse” in 2002.

47 The Applicants license the use of the Chemist Warehouse trade marks, get-up, slogans and associated intellectual property rights to each of the proprietors of retail pharmacies that trade under the name “Chemist Warehouse” across Australia.

48 As at 31 January 2014, there were over 250 Chemist Warehouse stores across all states and territories in Australia. As at March 2014, the Applicants had a proprietary interest, either as sole traders, together with one another or in partnership, with other pharmacists, in 68 of those pharmacies.

THE RESPONDENTS

49 DCO was formed on 7 February 2007 and Mr Tauman is a director and secretary of DCO.

50 Mr Tauman licenses the right to use the name and trade marks incorporating the words “Direct Chemist Outlet” to each of the pharmacies within the DCO group. He also assists the stores with operations as necessary but ultimately the operation of each store is a matter for the individual proprietors or pharmacist in charge.

51 DCO is responsible for marketing, merchandising and category management of the DCO pharmacies. The stores are operated by the licensees who are responsible for human resources, general buying and operation of the store.

52 The first DCO store opened in Werribee on or around 26 May 2006, and as at 28 April 2014, there were 24 stores in Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales.

The WITNESSES

53 The Applicants called evidence from the following principal witnesses:

(a) Mr Mario Verrocchi;

(b) Mr Damien Gance, the nephew of Mr Jack Gance, and proprietor of five Chemist Warehouse stores, and Group Commercial Manager of the Chemist Warehouse group;

(c) Mr Theo Kassahun, a former Retail Manager at Mount Waverley DCO;

(d) Ms Ashlen Arevyan, a former Dispensary Technician at Mount Waverley DCO; and

(e) Mr Ian Carroll, a sign writer who had been retained by Chemist Warehouse to paint signage on its stores.

54 The Respondents called evidence from the following principal witnesses:

(a) Mr Ian Tauman; and

(b) Ms Jenna Rohr, Group Co-ordinator of DCO.

LEGAL PRINCIPLES

The ACL / TPA

55 Section 52 of the TPA, now s 18 of Sch 2 of the CCA provides that a corporation or person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

56 As I have indicated, these provisions are the primary focus of the claims of the Applicants, although they did place reliance on other provisions in their pleadings. Nevertheless, in view of the approach I have taken, it is convenient to focus on the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions mentioned above.

57 Whilst there is a great deal of practical coincidence between the tort of passing off and contravention of the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions, the two claims have distinct premises. The former is designed to protect the goodwill or reputation of traders and the latter is designed to protect consumers. Nonetheless, the Applicants acknowledge that if they fail to establish a breach of the TPA or ACL, they will also fail to establish passing off.

General principles - misleading or deceptive conduct provisions

58 There is no dispute that the principles applicable to s 52 of the TPA and s 18 of the ACL are the same. The applicable principles relevant to a case regarding the alleged taking of the trade indicia (including a trading name) of a trade rival are set out in S & I Publishing Pty Ltd v Australian Surf Life Saver Pty Ltd (1998) 88 FCR 354; (‘S & I Publishing’) at FCR 362–3 per Hill, Nicholson and Emmett JJ, adopting with approval what Hill J said in Equity Access Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1989) 16 IPR 431 at 440-441. The relevant principles were restated in S & I Publishing as follows:

1. There will be no contravention of s 52 unless the error or misconception which occurs results from the conduct of the corporation and not from other circumstances for which the corporation is not responsible.

2. Conduct will be misleading and deceptive if it leads into error.

3. Conduct will be likely to mislead or deceive if there is a “real or not remote chance or possibility” of misleading or deceiving regardless of whether it is less or more than 50 per cent.

4. Conduct causing confusion or uncertainty in the sense that members of the public might have cause to wonder whether the two products or services might have come from the same source is not necessarily misleading and deceptive conduct.

5. In a case such as the present, an applicant must establish that it has acquired the relevant reputation in the name or get-up such that the name or get-up has become distinctive of the applicant’s business or products.

6. Conduct may be misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive notwithstanding that the corporation said to engage in that conduct acted honestly and reasonably and did not intend to mislead or deceive. Logically, a finding that conduct had been intentionally engaged upon will be irrelevant in determining whether that conduct is misleading or deceptive. It may perhaps be imagined that conduct engaged upon with the intent to mislead or deceive may fail in its purpose and not be found misleading or deceptive. Nevertheless, where the intention to mislead or deceive is found, it logically would be likely that a court would more easily find that the conduct was misleading or deceptive.

7. In many cases it will be necessary to consider the class of persons to whom the representation was directed...

8. There is no proposition of law to the effect that intervention from erroneous assumption between conduct and misconception destroys the necessary chain of causation with the consequence that the conduct cannot be regarded as likely to mislead or deceive.

9. The test of whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive is an objective one for the court to determine. It is ultimately a question of fact.

(citations omitted)

59 Justice Greenwood (with whom Tracey J agreed) in Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 280 ALR 639 (‘Bodum’) identified other principles to be applied under s 52 of the TPA in the context of a trade indicia (as opposed to a trade name) case, as follows (from [202]-[209]):

[202] …[A] rival trader is entitled to enter the market and copy precisely the product of another and seek to take some of its market share (in the absence of any infringement of a formal intellectual property right), so long as the rival does not mislead or deceive the public or pretend, by conduct, that its goods are the goods of another…

[203] Whether impugned conduct conveys the making of a representation is a question of fact to be determined having regard to all the contextual circumstances within which something was said or done. When that assessment is being made in the context of conduct said to involve representations to the public at large (or a section of the public) such as prospective retail buyers of a product sold by a respondent rival trader, s 52 must be regarded as contemplating the effect of the impugned conduct on reasonable members of the class of prospective buyers or ordinary members of that class…[S]o far as the remarks relate to deception:

The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what … deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men [and women] considered in the mass affords the standard.

[emphasis added]

[204] In order to test whether a misconception has arisen or might arise among members of the relevant cohort by reason of the impugned conduct, the inquiry is to be made notionally of the hypothetical individual excluding “assumptions by persons whose reactions are extreme or fanciful”…The question is “whether the misconceptions, or deceptions, alleged to arise, or to be likely to arise, are properly to be attributable to the ordinary and reasonable members of the class of prospective purchasers”…The issue is not whether the impugned conduct simply causes confusion or wonderment but whether the conduct is or is likely to mislead or deceive.

[205 …In determining whether a contravention of s 52 has occurred, the focus of the inquiry is whether a not insignificant number within the class or cohort have been misled or deceived or are likely to be misled or deceived by the respondent’s alleged conduct, whether in fact or by inference...

…

[210] In assessing the character of the conduct in question, against the background of all of the contextual circumstances, conduct which misleads a consumer such that he or she opens negotiations or invites approaches under some mistaken impression of a trader’s connection or affiliation with another, may be engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct even if the true position emerges before the transaction is concluded.

(citations omitted and emphasis in original)

60 In SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 169 ALR 1; (1999) 48 IPR 593 at [51], French, Heerey and Lindgren JJ reiterated that misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce is not limited to conduct which induces or is likely to induce entry into a transaction but may include an inducement to open negotiations or invite approaches, even if the true position emerges before the transaction is concluded.

61 Further, in ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640, the High Court noted that:

[50] It has long been recognised that a contravention of s 52 of the TPA may occur, not only when a contract has been concluded under the influence of a misleading advertisement, but also at the point where members of the target audience have been enticed into “the marketing web” by an erroneous belief engendered by an advertiser, even if the consumer may come to appreciate the true position before a transaction is concluded.

(footnotes omitted)

62 In considering whether consumers are likely to be misled or deceived, it is necessary to consider what was said and done against the background of all surrounding circumstances. These include:

(a) the strength of the applicant’s reputation, and the extent of distribution of its products;

(b) the strength of the respondent’s reputation, and the extent to which the respondent has undertaken any advertising of its product;

(c) the nature and extent of the differences between the products, including whether the products are directly competing;

(d) the circumstances in which the products are offered to the public; and

(e) whether the respondent has copied the applicant’s product or has intentionally adopted prominent features and characteristics of the applicant’s product.

63 The present case involves the adoption of trade indicia, rather than a trading name. Australian courts have recognised that a trader may establish a reputation in trade indicia other than names and logos, which may be protected without registration as a trade mark: Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (2007) 159 FCR 397 (‘the Cadbury Appeal’) at [97].

64 As I have said, colour schemes may play an important role in the marketing of a product or service.

65 In Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd v Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd (2001) 53 IPR 481 (‘Red Bull’) the respondents were found to have engaged in passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct by importing and selling a new energy drink which adopted the so-called “total imagery” of the applicants’ Red Bull energy drink (apart from its name). In so finding, Conti J held (at [55]) that:

…Colour schemes also constitute brand elements, colour being one of the most significant components of the get-up that attracts consumer attention, and being a central method of communication which can become part of a corporate supplier’s signature; instances cited by Dr Beaton include Kodak’s use of gold, black and red, Cadbury’s purple and Shell’s yellow and red. Ms Strachan responded that such entities have been using those respective colours over decades, and have operated in markets involving few competitors, and in the case of Shell for instance, the connection is not just the yellow colour but a yellow shell graphic; Dr Beaton rejoined that once attention is attracted to a product, the colour with which it is associated continues to have an effect in enhancing the way consumers comprehend and elaborate brand meaning in their minds; he cited advertising research to the effect that colour is central to brand recognition, and posited that achievement of recognition correlates strongly with probability of purchase; while he would accept that advertisement or package recognition does not necessarily cause propensity to purchase, the published research he cites constitutes important empirical observation which sheds light on the value of maximising the communication power of printed material, such as advertising and packaging.

66 Justice Conti recognised that the reputation may be distinct from the trading name associated with it. In Red Bull his Honour held (at [61]) that “Colour and colour combinations, particularly of cans such as those of the 250 ml size here involved, tends to attract attention before brand names embossed thereon”. Justice Conti determined (at [65]) that:

…Particularly in such product contexts, sufficient similarities of get-up may conceivably relate to elements of colour, shape and size, and thus to the existence of passing off, irrespective of the use by the competitor of a different brand name.

67 Further, there is no need to identify an exclusive reputation.

68 The Full Court in the Cadbury Appeal held that, for the purposes of the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions, there is no requirement that the applicant establish an exclusive reputation. The Full Court said at [97]–[99]:

[97] Both in the context of Part V of the Trade Practices Act and the common law tort of passing off, trade indicia other than names and logos can become associated with a particular trader, such that a use by another trader could give rise to misleading or deceptive conduct or passing off. If particular branding elements used by a trader have been identified in a special way with that trader in the minds of the members of the public, there may be misleading or deceptive conduct by reason of the appropriation of those particular branding elements by another trader.

[98] There is an overlap between causes of action arising under Part V of the Trade Practices Act and the common law tort of passing off. However, the causes of action have distinct origins and the purposes and interests that both bodies of law primarily protect are contrasting. Passing off protects a right of property in business or goodwill whereas Part V is concerned with consumer protection. Part V is not restricted by common law principles relating to passing off and provides wider protection than passing off.

[99] Whether or not there is a requirement for some exclusive reputation as an element in the common law tort of passing off, there is no such requirement in relation to Part V of the Trade Practices Act. The question is not whether an applicant has shown a sufficient reputation in a particular get-up or name. The question is whether the use of the particular get-up or name by an alleged wrongdoer in relation to his product is likely to mislead or deceive persons familiar with the claimant’s product to believe that the two products are associated, having regard to the state of the knowledge of consumers in Australia of the claimant’s product.

69 Once a trader has established that it has developed a secondary reputation in its trade indicia, the adoption of those indicia by another trader will be misleading or deceptive unless the rival trader can show that it has adequately distinguished its goods or services.

70 In Reckitt & Colman, Lord Oliver articulated the relevant test (at 15):

In the end, the question comes down not to whether the respondents are entitled to a monopoly in the sale of lemon juice in natural-size lemon-shaped containers but whether the appellants, in deliberately adopting, out of all the many possible shapes of container, a container having the most immediately striking feature of the respondents’ get-up, have taken sufficient steps to distinguish their product from that of the respondents. As Romer LJ observed in Payton & Co v Snelling, Lampard & Co (1900) 17 RPC 48 at 56:

When one person has used certain leading features, though common to the trade, if another person is going to put goods on the market, having the same leading features, he should take extra care by the distinguishing features he is going to put on his goods, to see that the goods can be really distinguished...

71 A similar approach was adopted by Burchett J (Hill and Branson JJ agreeing) in Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 90 at [42], who held that “in view of the similarity” of the products in that case, “it was incumbent upon…[the respondent] to distinguish” its product from the extant rival product.

72 In Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Apand Pty Ltd (1993) 46 FCR 152, Burchett J at first instance held (at 164) that once a trader has adopted a get-up closely resembling that of another trader’s product, even if it acted honestly in doing so, that trader “came under an obligation to take particular care to ensure that its product was adequately distinguished from that of the applicant”. Justice Burchett made this assessment on the basis of an objective examination of the conduct: at 165.

73 In Bodum, the majority found (at [197]) that a secondary reputation existed in the shape and features of Bodum’s coffee plunger, independently of the Bodum trade mark. Further, they found (at [196]) that as to the distinctiveness of those features, there was no evidence to suggest that the features of the Bodum coffee plunger were simply generic — there were many different styles of coffee makers. The majority concluded (at [189]) that consumers who retained a recognition of the trade mark and distinctive features of the Bodum coffee plunger were:

prima facie likely to think that a product exhibiting those features is a Bodum Chambord Coffee Plunger unless something about the rival product tells the consumer — “You are not looking at a Bodum Chambord Coffee Plunger here” — which goes to the question of labelling and the differentiation factors applicable to the rival product. The absence of the Bodum mark or name from the rival product, exhibiting the Bodum features of significant secondary distinction, does not diminish the attractive force of the secondary reputation in the features associated with the particular trader/manufacturer. The reputation for the shape and distinction of the Bodum Chambord Coffee Plunger does not dissolve in the absence of the trade mark.

74 The majority stated (at [198]) that the “real question to be determined” in that case was whether the respondent had “done enough having regard to all the relevant differentiation factors to distinguish its rival product from the Bodum product”.

75 In Bodum, the majority considered that the use by the respondent, of the brand name “Euroline” was not adequate to dispel the error caused by the adoption of Bodum’s other trade indicia (the shape of the coffee plunger). The majority held that:

(a) The name “Euroline” was “not distinctive and at …[the relevant date] was very likely to be regarded as an abbreviated description of a product having a provenance as a product within a line of European products”: at [236].

(b) The adoption of a “non-distinctive and descriptive trade mark” was “not sufficient to distinguish the rival product from the distinctive product sought to be copied”: at [244].

(c) It is an “error of principle to simply put cases such as Red Bull… to one side as purely ‘impulse purchase’ cases…”: at [262].

76 In Red Bull, Conti J held that the respondents had engaged in passing off by importing and selling a new energy drink which adopted the get-up (the red and blue on silver colouring of the cans — a case, like here, involving a combination of colour features) of the applicants’ Red Bull energy drink, even though the respondents’ energy drink was clearly labelled “LiveWire”. That decision was unanimously upheld on appeal in Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 55 IPR 354, even though Weinberg and Dowsett JJ noted (at 107) that “the respective names of the products and the prominence with which they are displayed” created “significant differences in appearance”. In concluding that the different brand names were insufficient to prevent passing off or misleading or deceptive conduct in Red Bull, Conti J noted (at [69]) that:

Even in the situation where both brand names were to be discernible at the point of sale to the potential customer, there would also be the “Ms Carswell” kind of customer, who might think that both products emanated from the same manufacturing stable, for all sorts of reasons, logical or otherwise.

77 It is important to appreciate that Red Bull was ultimately decided on the facts as found by the trial judge, and in particular the consistent application of a colour scheme and get-up. This is not the factual position in this proceeding.

78 It is not necessary for consumers to assume that the services are from the same source. It is sufficient if consumers believe that there is some connection or association between the services, or the persons who provide them: see H P Bulmer Ltd v J Bollinger SA [1978] RPC 79 (at 117 per Goff LJ) (approved by Beaumont J in Pacific Dunlop at 580).

79 Where the alleged misrepresentation is made to the public or a section of it (as opposed to identified individuals), the focus of the inquiry is whether a not insignificant number of persons within the relevant class of the public have been misled or deceived or are likely to be misled or deceived by the respondent’s alleged conduct, whether in fact or by inference: see Hansen Beverage Co v Bickfords (Aust) Pty Ltd (2008) 171 FCR 579 at [46] per Tamberlin J and at [66] per Siopis J.

80 There has been debate as to whether the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions require a “not insignificant number” of the relevant class, or a “significant” or “substantial” number of persons within the relevant class, to be misled or deceived (or be likely to be misled or deceived). As Yates J observed in Optical 88, the prevailing line of authority expresses the test in terms of “significant” or “substantial”, however his Honour shared my view that any perceived difference in approach is really a matter of expression and not of quantitative substance: at [341].

81 In circumstances such as in this proceeding, where a representation is made at large to a class (members of the public who are current or prospective purchasers of pharmacy products), the relevant assessment involves isolating a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable representative member of that class: see Campomar at [103]. In Campomar, the High Court stated (at [102]) that

[i]t is in these cases of representations to the public…that there enter the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers. Although a class of consumers may be expected to include a wide range of persons, in isolating the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of that class, there is an objective attribution of certain characteristics.

(footnotes omitted)

82 Likewise in Madden v Seafolly Pty Ltd (2014) 313 ALR 1, the Full Court stated at [77] that:

[o]n…occasions, such as here, there will be very many persons in the class of addressees with their own disparate, distinct characteristics so that it is not practicable or possible to analyse individual circumstances. In such cases, the court must identify the characteristics of the ordinary reasonable person in the class of addressees and assess the issue by reference to how that hypothetical person would have understood the publication, document or conduct…

83 I have already made some observations on the relevant date for assessing the alleged contraventions in this proceeding. However, I make the following further comments. The relevant date for assessing whether a respondent’s conduct amounts to a passing off is the date that the respondent’s conduct commenced in Australia. Although a court may consider evidence after that date for the purpose of determining what, if any, relief should be awarded, it may not do so in relation to liability.

84 Regarding the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions, the authority is to the same effect. The relevant date for assessing whether a respondent’s conduct contravenes the provisions, and thus, the relevant date for assessing (to the extent necessary) the reputation of the applicant, is the date the impugned conduct commenced. There may well be an issue of determining on the facts when the “impugned conduct” commenced, particularly if the conduct involves a number of different elements that substantially change over time.

85 Justice Yates explained the relevant and correct principles in Optical 88. In that case (at [53]), the businesses of the applicant and the respondents were “broadly described as the retail sale and supply of optical goods and accessories, and of optometry services”. The respondents used various iterations of the impugned name “Optical 88” in English and in Chinese characters on three stores, business cards and promotional materials starting on different dates from August 1993 to 2003. The respondents’ first store opened at Campsie, a suburb south-west of Sydney’s CBD, a second store opened in November 1993 at Chatswood on the North Shore of Sydney and a third store in July 1995 in Eastwood, a northern suburb of Sydney. Campsie is approximately a 20 km drive from each of Chatswood and Eastwood and the latter are about a 12 km drive from each other.

86 The applicant in Optical 88 referred to Gummow J’s observation in Thai World Import & Export Co Ltd v Shuey Shing Pty Ltd (1989) 17 IPR 289 (‘Thai World’) that reputation might become relevant at a date later than when the respondent commenced its conduct where the applicant left the market and then sought to re-enter. The applicant contended that the converse was also true — if its reputation strengthened, the date should be assessed later than the commencement of the respondent’s conduct.

87 Justice Yates held at [333]–[334]:

[333] In my view the applicant’s proposition cannot be derived (or even discerned) from the proposition discussed by Gummow J in Thai World. If, in the present case, the applicant can establish that, as at the date of commencement of the impugned conduct (August 1993), it had a sufficient reputation to sustain its claim that the first respondent has contravened s 52 of the Trade Practices Act, it does not need to rely on any intervening strengthening of that reputation in the period before the commencement of proceedings, although any strengthening of its reputation may be a matter that is relevant to the question of relief. If, on the other hand, the applicant cannot establish that, as at the date of commencement of the impugned conduct, it had a sufficient reputation to sustain its claim, I cannot see how any after-acquired reputation can assist it in the face of what would otherwise have been the legitimate commencement and continued conduct of the first respondent’s business.

[334] For the purposes of this aspect of the applicant’s claims, I propose to consider the first respondent’s impugned conduct at the time it commenced in August 1993. In my view this approach accords with both principle and established authority.

(citations omitted)

88 I now make some comments as to the principles of law relevant to where (as in this proceeding) there is evidence of copying.

89 A subjective intention to deceive or misrepresent is not a required element to establish passing off or contravention of the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions. Nevertheless, proof of deliberate borrowing of the features or get-up of a rival’s product provides “evidential value” in the sense that, if trade indicia are adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for that purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse: see Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 (‘Australian Woollen Mills’) at 657 per Dixon and McTiernan JJ.

90 In Australian Woollen Mills at 657, Dixon and McTiernan JJ expressed this principle as follows:

…The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive….

91 More recently the High Court in Campomar at [33] held:

… it is well established by the authorities referred to by the Privy Council … that, where there is such a finding of intention to deceive, the court may more readily infer that the intention has been or in all probability will be effective. Nevertheless, the actual decision in that case, favourable to the defendant, is a reminder that even an imitation of one product by another does not necessarily bespeak an intention to deceive purchasers. In particular, if Campomar were to retain its registrations and put them to use on a new range of products, the use thereon of NIKE would not necessarily indicate an intention to deceive purchasers.

92 In addition to the qualification set out above by the High Court, “even a deliberate copy of a rival’s get-up in order to deceive is just one piece of evidence to be assessed with other relevant evidence”: see Vendor Advocacy Australia Pty Ltd v Seitanidis (2013) 103 IPR 1 at [200], citing Windsor Smith Pty Ltd v Dr Martens Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 286 at [33] and REA Group Ltd v Real Estate 1 Ltd (2013) 102 IPR 1 at [212].

93 Then there is the issue of specific evidence of consumers or of those who have been misled. Even if evidence is given by a person that he or she was misled, this would not be conclusive and may be of limited utility.

94 As French J said in State Government Insurance Corporation v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales (1991) 28 FCR 511 at 529:

…Generally speaking in cases of alleged misleading or deceptive conduct which is analogous to passing-off, evidence from consumers that they have been misled by the impugned conduct is of limited utility. It has no statistical significance and the court cannot draw inferences from it that any section or fraction of the population will have similar reactions. But if the inference is open, independently of such testimonial evidence, that the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then it may be that the evidence of consumers that they have been misled can strengthen that inference. …

95 As Franki J said in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (‘Taco Bell’) at 202:

…[E]vidence that some person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself conclusively establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. The court must determine that question for itself. The test is objective.

(Citations omitted)

96 The relevant enquiry is by reference to a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class, and the test is objective.

97 Finally, in deciding whether a respondent’s conduct breached the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions it is necessary to inquire why any proven misconception has arisen: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 (‘Hornsby’) at 228 per Stephen J with Jacobs J agreeing; Taco Bell at 203 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ. In cases regarding the alleged taking of a competitor’s trade indicia it is necessary to understand whether (or to what extent) any misconception suffered by consumers arises through the respondent’s use of common or descriptive trade indicia.

98 As Lord Simonds said in Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd [1946] 63 RPC 39 at 43:

So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be.…[W]here a trader adopts words in common use for his trade name, some risk of confusion is inevitable. But that risk must be run unless the first user is allowed unfairly to monopolise the words. The Court will accept comparatively small differences as sufficient to avert confusion. A greater degree of discrimination may fairly be expected from the public where a trade name consists wholly or in part of words descriptive of the articles to be sold or the services to be rendered.

99 In Hornsby, Sydney Building Information Centre had been trading under that name for more than 20 years, and Stephen J accepted that there been some instances of confusion with the newly named Hornsby Building Information Centre. In an often quoted passage his Honour said at 229-230:

There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name. Because it is descriptive it is equally applicable to any business of a like kind, its very descriptiveness ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business and hence its application to other like businesses will not ordinarily mislead the public. In cases of passing off, where it is the wrongful appropriation of the reputation of another or that of his goods that is in question, a plaintiff which uses descriptive words in its trade name will find that quite small differences in a competitor’s trade name will render the latter immune from action. …The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.

If this be so in the case of passing off actions the case of s 52(1), concerned only with the interests of third parties, is a fortiori. To allow this section of the Trade Practices Act to be used as an instrument for the creation of any monopoly in descriptive names would be to mock the manifest intent of the legislation. Given that a name is no more than merely descriptive of a particular type of business, its use by others who carry on that same type of business does not deceive or mislead as to the nature of the business described….

(Citations omitted and emphasis added)

100 I observe that in this proceeding, as I have remarked earlier, the colours used by the Applicants had a practical and functional role. The colour yellow was accepted as being attention-grabbing. It has a general connotation of cheapness, good value or discount, and not just in the retail pharmacy industry. It is readily apparent that other traders would want to, and do, use this colour (and the other primary colours used by the parties in this proceeding) as part of their branding elements. There is nothing novel, unusual or unexpected in the way in which the Applicants used colour, nor in their advertising phrases and slogans. This is relevant to the consideration of whether the Respondents’ conduct was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.

Trade mark

Validity

101 Section 88 of the TM Act allows for a trade mark registration to be cancelled amended or limited, including on the basis of grounds that could have been raised in opposition to the application for registration of that mark. The TM Act further provides that registration “may be opposed on any of the grounds on which an application for the registration of a trade mark may be rejected…”: s 57. It follows that s 88 is read, in the present context, together with s 41 of the TM Act. Section 41 provides for the rejection of a trade mark application on the grounds that it is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of other persons, as required by s 17 of the TM Act.

102 Section 41 at the relevant time provided that:

Trade mark not distinguishing applicant’s goods or services

(1) An application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if the trade mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered (the designated goods or services) from the goods or services of other persons.

(2) A trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons only if either subsection (3) or (4) applies to the trade mark.

(3) This subsection applies to a trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(b) the applicant has not used the trade mark before the filing date in respect of the application to such an extent that the trade mark does in fact distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant.

(4) Then, if the Registrar is still unable to decide the question, the following provisions apply.

(5) If the Registrar finds that the trade mark is to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons but is unable to decide, on that basis alone, that the trade mark is capable of so distinguishing the designated goods or services:

(a) the Registrar is to consider whether, because of the combined effect of the following:

(i) the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services;

(ii) the use, or intended use, of the trade mark by the applicant;

(iii) any other circumstances;

the trade mark does or will distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant; and

(b) if the Registrar is then satisfied that the trade mark does or will so distinguish the designated goods or services—the trade mark is taken to be capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(c) if the Registrar is not satisfied that the trade mark does or will so distinguish the designated goods or services—the trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of other persons.

(6) If the Registrar finds that the trade mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons, the following provisions apply:

(a) if the applicant establishes that, because of the extent to which the applicant has used the trade mark before the filing date in respect of the application, it does distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant—the trade mark is taken to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons;

(b) in any other case—the trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons.

(Notes omitted)

103 The proper test for assessing the inherent capacity of the registered trade mark to distinguish the designated services for the purposes of s 41(3) still remains that articulated by Kitto J in Clark Equipment Co v Registrar of Trade Marks (1964) 111 CLR 511. The High Court in Cantarella Bros Pty Limited v Modena Trading Pty Limited [2014] HCA 48 at [59] recently endorsed this test, and in so doing made the following observations:

The principles settled by this Court (and the United Kingdom authorities found in this Court to be persuasive) require that a foreign word be examined from the point of view of the possible impairment of the rights of honest traders and from the point of view of the public. It is the “ordinary signification” of the word, in Australia, to persons who will purchase, consume or trade in the goods which permits a conclusion to be drawn as to whether the word contains a “direct reference” to the relevant goods (prima facie not registrable) or makes a “covert and skilful allusion” to the relevant goods (prima facie registrable). When the “other traders” test from [Registrar of Trade Marks v W & G Du Cros Ltd [1913] AC 624 (‘Du Cros’)]… is applied to a word (other than a geographical name or a surname), the test refers to the legitimate desire of other traders to use a word which is directly descriptive in respect of the same or similar goods. The test does not encompass the desire of other traders to use words which in relation to the goods are allusive or metaphorical. In relation to a word mark, English or foreign, “inherent adaption to distinguish” requires examination of the word itself, in the context of its proposed application to particular goods in Australia.

104 Consideration needs to be given as to the degree of inherent adaptability to distinguish so as to determine whether sections 41(3), 41(5) or 41(6) of the TM Act apply and then, consideration needs to be given to any use made prior to the filing date of the registered mark.

105 The inherent adaptability of a trade mark is ascertained by consideration of the mark in the context of nominal use. This test was formulated by Kitto J in Clark Equipment at 514, where his Honour described the test as follows:

...the question whether a mark is adapted to distinguish [is to] be tested by reference to the likelihood that other persons, trading in goods of the relevant kind and being actuated only by proper motives — in the exercise, that is to say, of the common right of the public to make honest use of words forming part of the common heritage, for the sake of the signification which they ordinarily possess — will think of the word and want to use it in connexion with similar goods in any manner which would infringe a registered trade mark granted in respect of it.

106 Justice Kitto, in Clark Equipment at 514, also referred to Lord Parker of Waddington in Du Cros at 635, where his Honour quoted his Lordship as follows:

The applicant’s chance of success in this respect [ie in distinguishing his goods by means of the mark, apart from the effects of registration] must, I think, largely depend upon whether other traders are likely, in the ordinary course of their businesses and without any improper motive, to desire to use the same mark, or some mark nearly resembling it, upon or in connexion with their own goods...

107 This test does not require that any other trader has actually used the relevant sign previously. The inquiry, as applied in this proceeding, is into what other chemists might legitimately wish to do in the course of their business. This test is applied at the priority date of the application.

108 The potential infringement of a registered mark through the use of substantially identical or deceptively similar trade marks by any other trader is a relevant consideration. The Court is required to consider whether other traders would wish to use substantially identical or deceptively similar words. This was discussed expressly by Stone J in Kenman Kandy Australia Pty Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks (2002) 122 FCR 494 (‘Kenman Kandy’):

[161] ... That question must be answered bearing in mind that infringement would include using as a trade mark in relation to confectionary, not only the bug shape but also any “sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to” the bug shape: s120 of the 1995 Act.

Infringement

109 Section 120 of the TM Act provides:

120 When is a registered trade mark infringed?

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(b) services that are closely related to registered goods; or

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

(3) A person infringes a registered trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is well known in Australia; and

(b) the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(i) goods (unrelated goods) that are not of the same description as that of the goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered (registered goods) or are not closely related to services in respect of which the trade mark is registered (registered services); or

(ii) services (unrelated services) that are not of the same description as that of the registered services or are not closely related to registered goods; and

(c) because the trade mark is well known, the sign would be likely to be taken as indicating a connection between the unrelated goods or services and the registered owner of the trade mark; and

(d) for that reason, the interests of the registered owner are likely to be adversely affected.

(4) In deciding, for the purposes of paragraph (3)(a), whether a trade mark is well known in Australia, one must take account of the extent to which the trade mark is known within the relevant sector of the public, whether as a result of the promotion of the trade mark or for any other reason.

110 The question of trade mark infringement requires a comparison to be made between the registered trade mark and the impugned sign. In The Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407, Windeyer J (at 414) said with respect to “substantial identity”:

In considering whether marks are substantially identical they should, I think, be compared side by side, their similarities and differences noted and the importance of these assessed having regard to the essential features of the registered mark and the total impression of resemblance or dissimilarity that emerges from the comparison….

111 As to “deceptive similarity”, s 10 of the TM Act provides that “a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.” In relation to “deceptive similarity”, Windeyer J said (at CLR 415):

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from ... [the impugned mark].

112 In Australian Woollen Mills, Dixon and McTiernan JJ (at 658) observed with respect to “deceptive similarity”:

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning may play an important part. The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight…

113 Furthermore, the test is not one of actual deception or confusion but the likelihood of deception or confusion occurring by reason of the use of the mark. In Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 Kitto J at 595 explained:

It is not necessary, in order to find that a trade mark offends against the section, to prove that there is an actual probability of deception leading to a passing-off. While a mere possibility of confusion is not enough — for there must be a real, tangible danger of its occurring — it is sufficient if the result of the user of the mark will be that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products come from the same source. It is enough if the ordinary person entertains a reasonable doubt…

(citations omitted)

CONSIDERATION

Chemist Warehouse

The history of Chemist Warehouse

114 Mr Verrocchi has been a registered pharmacist for over 34 years and Mr Jack Gance has been a registered pharmacist for over 40 years.

115 The Applicants and Mr Sam Gance have owned pharmacy businesses in partnership with one another and other pharmacists for over 32 years, trading under and by reference to various names including “Chemist Warehouse”, “My Chemist”, “Amcal”, “Gance Chemist”, “Verrocchi Chemist”, as well as other names.

116 In or around 1997, the Applicants, Mr Sam Gance and his late wife Ms Lydia Gance had, between them, approximately 30 pharmacies in Victoria, about half of which traded under the “Amcal” banner. In or about mid-1997 they collectively decided to end their relationship with Amcal and create their own new banner group for their pharmacy stores called “My Chemist”. My Chemist stores, like Amcal, were traditional community pharmacies that typically traded from retail premises that were approximately 200 m2 in size, and were either located within shopping centres or on high streets.

117 Between 1997 and late 1999, there were approximately 40 My Chemist stores in Victoria and one in Adelaide. These stores were owned either alone or in partnership by the Applicants, Sam and Lydia Gance, Mr Verrocchi’s twin brothers Adrian and Marcello, and some others.

118 In late 1999, the Applicants and Mr Sam Gance identified a business opportunity to establish large format discount retail pharmacies in Australia. There were a number of factors which led them to pursue this.

119 First, prior to this time, as far as they were aware, there were no chains of large format discount pharmacies in Australia. There were signs at the time that “big box” discount retail formats would be successful in Australia. Specifically, they discussed how the retail hardware industry was being revolutionised by Bunnings Warehouse which had quickly overtaken the market share of established local hardware stores such as Mitre 10. They also identified a similar trend emerging with consumer electrical retailers. Large discount stores such as JB Hi-Fi were quickly winning market share at the expense of long standing electrical retailers such as Brashs and Billy Guyatts, which ultimately closed down. The Applicants and Mr Sam Gance were also attracted to the rental advantages of operating in large premises outside shopping centres.

120 Secondly, at about this time (in late 1999), Mr Sam Gance’s son (and the second Applicant’s nephew) Mr Damien Gance was about to be registered as a pharmacist in Victoria. Mr Sam Gance spoke to the Applicants about Mr Damien Gance joining their network of My Chemist family owned businesses. The Applicants and Mr Sam Gance could not own any more pharmacies as they had reached their regulatory ownership limit. They subsequently met Mr Damien Gance in early 2000. Mr Verrocchi and Mr Sam Gance told Mr Damien Gance about their idea to establish a new large format retail “category killer” store in the pharmacy industry like Bunnings Warehouse had done in the retail hardware industry. Mr Damien Gance expressed interest in joining the Applicants and in early 2000, together they further developed the large format discount pharmacy concept.

121 The Applicants and Mr Sam Gance initially discussed names for the new business concept and decided that the name “Chemist Warehouse” would be a good fit.

122 In or about March 2000, Mr Sam Gance, in consultation with the Applicants and Mr Damien Gance engaged a creative media agency to develop a name and logo designs for the discount pharmacy concept business. Mr Sam Gance informed the agency that “Chemist Warehouse” was their preferred name.

123 In March 2000, the Applicants first registered the business name “Chemist Warehouse” in Victoria and have since that time been the owners of that registered business name.

124 The creative agency’s preferred business name was “Chemi Stop”. In or about late April 2000, it presented logos designed for Chemi Stop which adopted a traffic theme with red stop signs and the use of traffic colours including red, yellow as well as blue and white and a tag line “Stop Paying Too Much”.

125 The next day, Messrs Damien and Sam Gance discussed potential business names at a meeting with the Applicants. The Applicants both preferred the name Chemist Warehouse but proceeded with Chemi Stop because the .com and .com.au domain names for Chemist Warehouse were unavailable at the time, whereas they were available for Chemi Stop.