Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2015] FCA 210

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: | BRISBANE |

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

1. Native title does not exist in relation to any part of the land or waters in the Determination Area, as described in the Schedule.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. There be no order as to costs.

SCHEDULE

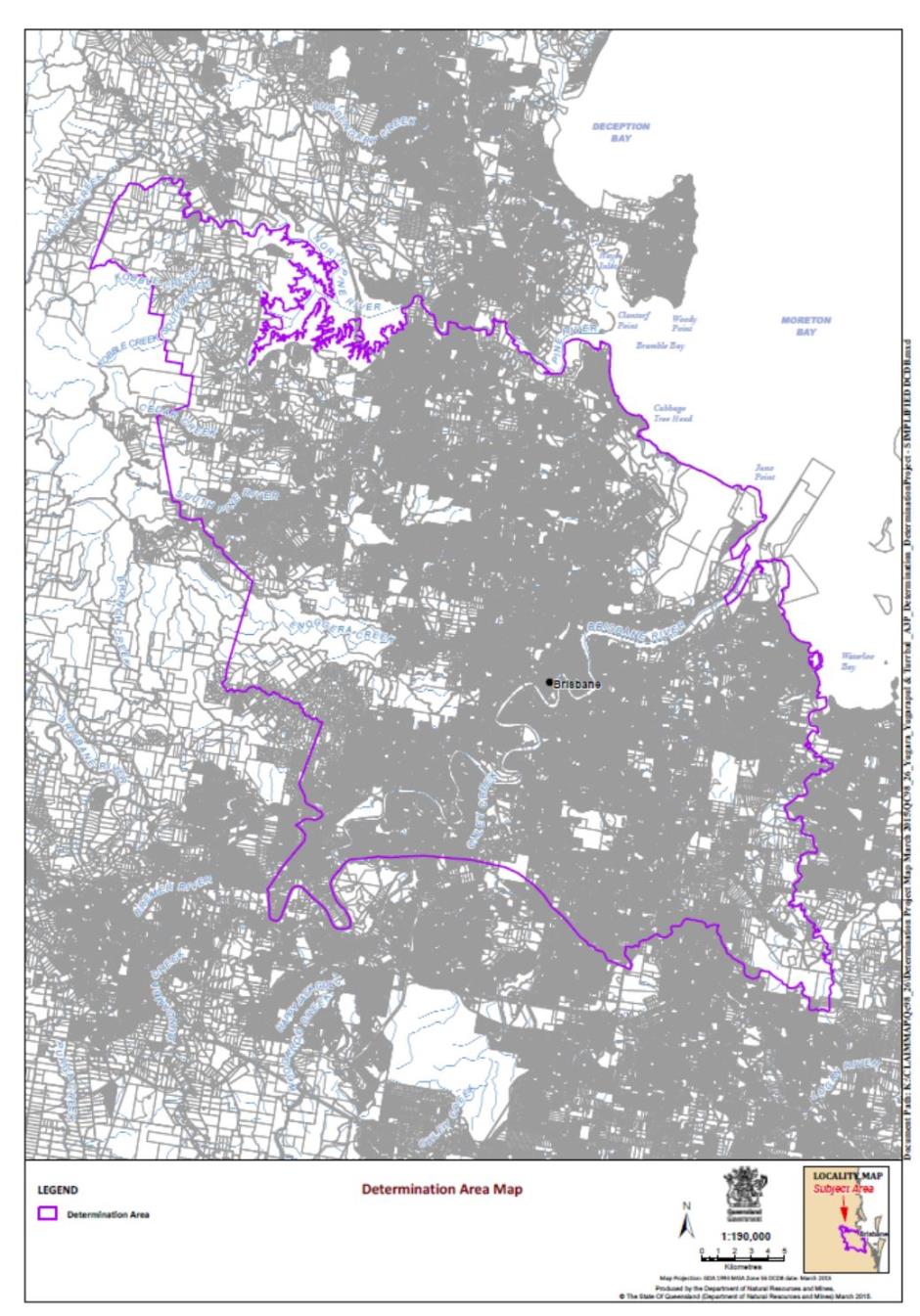

The Determination Area comprises all of the land and waters within the external boundary described in Part 1 below and depicted on the map in Part 2 below.

Part 1 – External boundary

Commencing at the intersection of the High Water Mark of Bramble Bay and the southern bank of the mouth of Pine River and extending generally south easterly along that High Water Mark to the mouth of the Brisbane River; then generally southerly and generally south westerly along the northern bank of that river and the northern bank of Boggy Creek to Latitude 27.394846° South; then southerly to the easternmost corner of Lot 1214 on SL12152; then generally north easterly and generally southerly along western and eastern boundaries of Lot 853 on SL5251 to its south easternmost corner, being a point on the northern bank of the Brisbane River; then generally south westerly along the northern bank of that river to Latitude 27.420958° South; then south easterly to the southern bank of the Brisbane River at Longitude 153.136796° East; then generally north easterly and south easterly along the bank of that river and the southern bank of the Boat Passage between Whyte and Fishermans Islands to the High Water Mark of Moreton Bay; then generally southerly again along that high water mark to the centreline of Tingalpa Creek; then generally southerly along the centreline of that creek to its intersection with the southern boundary of Lot 106 on NPW538; then southerly to a point on the Logan River Catchment boundary at Longitude 153.199606° East; then generally westerly along that catchment boundary to Longitude 153.052006° East; then generally north westerly passing through the following coordinate points.

Longitude° East | Latitude° South |

153.050942 | 27.609753 |

153.046571 | 27.606780 |

153.040801 | 27.600486 |

153.036255 | 270595940 |

153.029087 | 27.590170 |

153.024366 | 27.584051 |

153.018072 | 27.578281 |

153.008455 | 27.571986 |

153.000587 | 27.568839 |

152.979955 | 27.564818 |

152.965443 | 27.563769 |

152.950931 | 27.562545 |

152.930300 | 27.563419 |

152.922432 | 27.563069 |

152.913689 | 27.564118 |

152.906086 | 27.564592 |

152.903498 | 27.565635 |

Then south westerly to the centreline of the Brisbane River at Latitude 27.567622° South; then generally southerly, generally north westerly, generally south westerly and generally northerly along the centreline of that river to a point west of the northern boundary of Myora Street (Mogill) at Latitude 27.580622° South; then easterly to the north westernmost point of Myora Street (Mogill); then north easterly to the intersection of the centre lines of Witty Road and Matfield Street (Moggill); then north easterly to the intersection of the centrelines of Kangaroo Gully Road and Sugars Road (Anstead); then generally northerly and generally north westerly along the centreline of Kangaroo Gully Road to the centreline of Mount Grosby Road; then generally easterly and generally north westerly along the centreline of that road and the centreline of Boyle Road (Pullenvale) to the centreline of O'Brien Road (Pullenvale); then generally north westerly along the centreline of that road to its northernmost point; then north easterly to the intersection of the centrelines of Haven Road and Upper Brookfield Road (Upper Brookfield); then generally westerly along the centreline of Upper Brookfield Road to the centreline of Gillies Road (Upper Brookfield); then generally northerly along the centre line of that road to its northernmost point; then north easterly to a point on the centreline of Wohlsen Road (Wights Mountain), at Latitude 27.412936° South; then north westerly to the southernmost point on the centreline of Hulcombe Road (Highvale) at Longitude 152.828665° East; then generally north westerly along the centreline of that road, to the centreline of Ryder Road; then generally north westerly and generally north along the centreline of that road to the centreline of Mount Glorious Road (Highvale); then generally westerly, generally northerly and generally north westerly along the centreline of that road to Latitude 27.365761° South; then north northwest to a point on the centreline of Cedar Creek Road (Cedar Creek) at Longitude 152.787733° East; then north easterly to the easternmost south eastern corner of Lot 104 on NPW751 (formerly Lot 104 NPW654) (D'Aguilar National Park); then generally northerly and generally westerly along boundaries of that lot to the easternmost south eastern corner of Lot 809 on NPW751 (formerly Lot 809 on AP6239) (D'Aguilar National Park); then northerly, generally north westerly and generally westerly along boundaries of that lot to the eastern boundary of Lot 131 on SP209729; then north easterly to the intersection of the centre lines of Myles Road and Rowe Road (Laceys Creek); then generally north easterly and generally easterly along the centre line of Rowe Road to the centreline of Laceys Creek road; then generally easterly along the centreline of that road to a western bank of the North Pine River; then generally southerly, generally south easterly, generally easterly, generally south westerly and again easterly along the southern bank of that river, the High Water Mark of Lake Samsonvale, again southern banks of the North Pine River and southern banks of the Pine River back to the commencement point.

Part 2 – Map of Determination Area

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 586 of 2011 QUD 6196 of 1998 |

BETWEEN: | DESMOND SANDY, RUTH JAMES and PEARL SANDY ON BEHALF OF THE YUGARA/YUGARAPUL PEOPLE First Applicants CONNIE ISAACS and MAROOCHY BARAMBAH ON BEHALF OF THE TURRBAL PEOPLE Second Applicants |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND First Respondent BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL Second Respondent MORETON BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL Third Respondent REDLAND CITY COUNCIL Fourth Respondent TELSTRA CORPORATION Fifth Respondent GARRY MURPHY Sixth Respondent BRISBANE PORT HOLDINGS PTY LTD Seventh Respondent EDDIE RUSKA Eighth Respondent LOGAN CITY COUNCIL Ninth Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Eleventh Respondent THE SHELL COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LTD (ACN 004 610 459) Twelfth Respondent INCITEC FERTILIZERS LTD Thirteenth Respondent MOONIE PIPELINE COMPANY PTY LTD Fourteenth Respondent CENTOR AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Fifteenth Respondent QUEENSLAND SOUTH NATIVE TITLE SERVICES Sixteenth Respondent |

JUDGE: | JESSUP J |

DATE: | 16 MARCH 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 27 January 2015, I answered the first of two questions reserved for separate determination in this proceeding: Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland [2015] FCA 15. If any party then proposed to submit that orders should be made for the determination of the proceeding as a whole, I required that party to file and serve a minute of the orders sought, and a memorandum in support of the making of such orders. The first respondent, the State of Queensland ("the State"), did so. On 11 February 2015, the court received submissions in line with the State's memorandum and submissions from other parties on the subject of the orders which should now be made, and took other procedural steps to which I refer below.

2 Queensland South Native Title Services ("QSNTS") applied to be joined as a party to the proceeding, for the limited purpose of making submissions as to the appropriate form of the final orders to be made. There was no opposition to that application, and I granted it.

3 The first applicants, Desmond Sandy, Ruth James and Pearl Sandy on behalf of the Yugara/Yugarapul people ("the Yugara applicants") sought a stay of the orders which I made on 27 January 2015, and a stay of the proceeding generally, on the ground that they proposed to appeal against those orders. It is clear, however, that the orders were interlocutory, that leave to appeal would be required, and that any application for such leave would have been out of time: Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), r 35.13(a). In recognition of the fact that the judgment of 27 January 2015, although interlocutory, amounted to a final disposition of the issues of substance in the proceeding, I ordered that time for the making of any application for leave to appeal be extended to the 21st day after the delivery of final judgment in the proceeding. The making of such an order having been foreshadowed, the Yugara applicants accepted that the need for a stay of the orders of 27 January 2015, and of the proceeding generally, fell away.

4 In the alternative, it was submitted on behalf of the Yugara applicants that the court should not move to a final determination of the proceeding, but should allow them to re-open their case for the purpose of leading evidence additional to that upon which they had relied in the proceeding to date. It was not suggested that this was evidence which, with the diligence expected of litigants in the conventional conduct of a case, might not have been collected, and led, in the proceeding which led to the court's judgment of 27 January 2015. So far as I can see, the point was no more than that, with more time at their disposal, the Yugara applicants would expect now to be able to lead evidence that would be more helpful to them. This submission must be rejected. The proceeding to date has involved a final hearing on the merits, in which the Yugara applicants had, and exercised, the full participation rights of any party. There is nothing before the court that would justify taking the exceptional – and, it must be said, remarkable – step of allowing them to re-open their case on no better ground than that, with more time at their disposal, they might be able to find more evidence that would support their claim.

5 Similar submissions were made by the second applicant, Maroochy Barambah on behalf of the Turrbal people. Insofar as she should be understood as applying for a stay pending appeal, in the light of the extension of time to which I have referred above, Ms Barambah too accepted that a stay was unnecessary. She also sought an order that, to the extent that the judgment of 27 January 2015 related to herself, it be stayed for six months "for the purpose of enabling the second applicant to consult with its [sic] extended kins with a view to re-formulating a wider society native title application". Although no submissions were made specifically in support of an order in these terms, it is apparent that Ms Barambah's application for it contemplates the formulation and conduct of a new case. That is, quite clearly, no proper ground for the court to stay the operation of orders which finally disposed of the application which Ms Barambah did make.

6 It was submitted on behalf of the State that, Question (a) referred to in the orders made on 30 October 2013 having been answered in the way that it was on 27 January 2015, the court should now proceed to make a determination under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ("the Act") that native title does not exist in relation to land and waters in the claim area. In response, QSNTS submitted that, in the procedural setting of the present case, the court had no power to make such a negative native title determination. It is convenient to turn next to a consideration of that submission.

7 QSNTS accepted that the court did have the power to make a negative native title determination. By s 13(1) of the Act:

An application may be made to the Federal Court under Part 3 [of the Act] … for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title ….

A "determination of native title" is, by s 225 –

… a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area … of land or waters and, if it does exist ….

It is the "whether or not" aspect of s 225 that makes it clear that a negative native title determination is within the range of outcomes contemplated by the Act.

8 Section 61(1) of the Act is central to the submission which QSNTS makes:

(1) The following table sets out applications that may be made under this Division to the Federal Court and the persons who may make each of those applications:

Applications | ||

Kind of application | Application | Persons who may make application |

Native title determination application | Application, as mentioned in subsection 13(1), for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title. | (1) A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed, provided the person or persons are also included in the native title claim group; or Note 1: The person or persons will be the applicant: see subsection (2) of this section. Note 2: Section 251B states what it means for a person or persons to be authorised by all the persons in the native title claim group. (2) A person who holds a non-native title interest in relation to the whole of the area in relation to which the determination is sought; or (3) The Commonwealth Minister; or (4) The State Minister or the Territory Minister, if the determination is sought in relation to an area within the jurisdictional limits of the State or Territory concerned. |

Revised native title determination application | Application, as mentioned in subsection 13(1), for revocation or variation of an approved determination of native title, on the grounds set out in subsection 13(5). | (1) The registered native title body corporate; or (2) The Commonwealth Minister; or (3) The State Minister or the Territory Minister, if the determination is sought in relation to an area within the jurisdictional limits of the State or Territory concerned; or (4) The Native Title Registrar. |

Compensation application | Application under subsection 50(2) for a determination of compensation. | (1) The registered native title body corporate (if any); or (2) A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the compensation claim group) who claim to be entitled to the compensation, provided the person or persons are also included in the compensation claim group. Note 1: The person or persons will be the applicant: see subsection (2) of this section. Note 2: Section 251B states what it means for a person or persons to be authorised by all the persons in the compensation claim group. |

9 In the submission of QSNTS, a negative native title determination must have been the subject of an application under s 13 of the Act. In this submission, reliance was placed principally on the judgment of the Full Court in Commonwealth of Australia v Clifton (2007) 164 FCR 355. In that appeal from a single Judge of the court, the question was –

… whether the Federal Court may make a determination of native title in favour of a person who has not made a native title determination application under s 61 of the Act in relation to the area in question but who is a respondent to such an application brought on behalf of a claimant group which does not include him.

(164 FCR at 356 [1]) As is implicit in the question so formulated, the respondent referred to had sought the making, in favour of himself and those with whom he was associated, of a positive native title determination. The primary Judge had held that, on a proper construction of the Act, he could not proceed in this way.

10 The Full Court emphasised the procedure by which the Act required native title applications to be made. Their Honours said (164 FCR at 358-359 [20]):

Section 62 of the Act requires a claimant application (ie a native title determination application that a native title claim group has authorised to be made (see s 253)) to be accompanied by an affidavit sworn by the applicant which, in effect, verifies the claim including that the applicant is authorised by all persons in the native title claim group to make the application and to deal with the matter arising in relation to it (see ss 61(2), 62(1)(a)(iv) and 253). The affidavit must also provide details of the area covered by the application (s 62(2)(a)), details and results of all searches carried out on behalf of the claim group to determine the existence of any non-native title rights and interests (s 62(2)(c)) and a general description of the factual basis on which it is asserted that the native title rights and interests claimed exist (s 62(2)(e)). Section 62(3) requires a comparable affidavit to accompany a compensation application.

Their Honours said (164 FCR at 359-360 [24]):

If an application under s 61 of the Act is filed, the Registrar of the Federal Court must, as soon as practicable, give the Native Title Registrar a copy of the application and any affidavit that accompanies the application (s 63). The Native Title Registrar is required to comply with the requirements of s 66 of the Act which concern the giving of notice of the application. Notice must be given to any State or Territory within whose jurisdictional limits the claim area falls; to any representative bodies for the area covered by the application; to any registered native title claimant, registered native title body corporate or any representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander body, in relation to any of the area; to the Commonwealth Minister; to any local government body for the area and to any other person whose interests may be affected by a determination in relation to the application. We interpolate that no equivalent obligation is imposed on the Native Title Registrar or any other person to give notice of any claim advanced, whether by cross-claim or otherwise, by a respondent or respondents to a s 61 application. Section 64 authorises the amendment of applications that reduce the area covered by the application (s 64(1A) but proscribes any amendment to include any area of land or waters not covered by the original application except by the combination of applications (s 64(1) and (2)).

11 Their Honours held that s 61(1) of the Act had two purposes:

The first is to identify the applications that may be made under Div 1 of Pt 3 of the Act. The second is to identify the person or persons who may invoke the jurisdiction of the Court by making one of the three kinds of application with which the section is concerned; that is, to identify those who have standing to make those applications.

(164 FCR at 364 [42]) They added (164 FCR at 364 [43]) that the requirement of s 213(1) that a determination of native title be made in accordance with the procedures in the Act made it necessary to identify the procedures in the Act that governed the making of a determination of native title, and to determine which of those procedures the legislature intended to be critical to a valid exercise of the jurisdiction of the court.

12 Their Honours referred to Pt 4 of the Act, which governed the way the court was to exercise its jurisdiction to hear and determine native title applications, and said, "[i]mportantly, unless the court orders to the contrary after taking into account the matters identified in s 86B(4), every application under s 61 must be referred … for mediation" (164 FCR at 364 [45]).

13 The core of the reasoning of the Full Court was in the following passage in their Honours' reasons (164 FCR at 365-366 [52]-[53]):

In our view, it is unlikely almost to the point of being fanciful that the legislature intended that standing to institute a proceeding claiming a determination of native title should be strictly limited to persons authorised by the relevant native title claim group but that standing effectively to counter-claim for identical relief should be unlimited by any requirement for authorisation. This unlikelihood is the more apparent when one considers the numerous obligations placed on the Native Title Registrar to give notice of a native title determination application. Assuming the submissions of the Commonwealth and Mr McKenzie to be correct, other parties to the proceeding could advance comparable claims without any requirement arising for these statutory requirements and obligations to be met.

We also think it unlikely that the legislature intended that while all applications under s 61 should, in other than the limited circumstances specified in s 86B(3), be referred to the Tribunal for mediation, applications of the same character could be advanced by way of counter-claim and the mediation process thereby possibly avoided.

14 In the submission made on behalf of QSNTS a significant feature of the table in s 61(1) of the Act is the inclusion of provision for native title determination applications to be made by persons other than those who, under item (1) in the first compartment of the table, claim to be the holders of native title. In the present case, it was submitted, the State could have made an application conformably with item (4). If the respondent in Clifton was told that he ought to have made an application of a kind contemplated by s 61(1), there was no reason why the same advice ought not to be given to someone who held a non-native title interest in the land, to the Commonwealth or to the State.

15 I do not accept the QSNTS submission. There is nothing in the reasons of the Full Court in Clifton to indicate that the particular question now in issue was under consideration to any extent. In the circumstances, I do not think that Clifton should be regarded as authority for anything beyond the matter covered by the question identified at the outset of their Honours' reasons (see para 9 above). Furthermore, the reasoning in Clifton does not require me, by a process of extension, to answer a corresponding question, this time relating to the position occupied by the State, in the negative. In other words, Clifton is to be distinguished.

16 The fundamental premise by reference to which the court should address the QSNTS submission is that applications for determinations of native title have been made. That is to say, the court has before it applications for determinations of whether or not native title exists. Those applications have been duly made conformably with item (1) in s 61(1), and have been through the statutory procedures to which their Honours referred in Clifton. That either or both of those applications might result in a determination that native title does not exist strikes me as an inescapable possibility under the statutory scheme. Even without the submission of any respondent, the Act contemplates the making of such a determination as within the range of possible outcomes.

17 It is one thing to deny that, without the authorisation, publication and other procedures required by the Act, someone who is merely a respondent to the application of another group may advance a claim that native title exists. It would be, in my view, another thing altogether to hold it to be beyond the power of the court to rule that native title did not exist in the area in question because no-one had made a formal application in that regard. There is neither inconvenience nor injustice in taking the view, as I do, that such a holding would be wrong.

18 Upon the making of an application for a native title determination, it becomes a matter of public record that the person or group concerned claims to hold the native title concerned; and the area to which the claim relates is likewise a matter of public record. It is not a matter of public record that some other person also claims to be the holder of native title in relation to the same land. If what was unsuccessfully proposed in Clifton became the practice, one would have the possibility of rights, and right-holders, being recognised without the claims concerned ever having become a matter of public record. By contrast, when any application for a determination of native title is made, it is a matter of public record that the person or group concerned may, at the end of the proceeding, be recognised as the holder or holders of native title. By the terms of s 225, it is also a matter of public record that the proceeding may result in the making of a determination that native title does not exist in relation to the land concerned.

19 For the reasons I have given, I hold that the court does have power to make a determination that native title does not exist in relation to the claim area in the present case.

20 It was next submitted on behalf of QSNTS that the court should not, in the circumstances that have arisen, exercise that power. There were six propositions – effectively grounds – subtended from that submission.

21 First, it was submitted that the State had accepted that it should be inferred, from what was known of aboriginal life and society at and after the earliest days of white contact, that the claim area was then occupied by aboriginal people who were united by their acknowledgement and observance of a body of laws and customs. It was said that the two applicant groups accepted the same inference. These things are true, of course, but they go no further than to provide a broad background against which the matter of present concern must be resolved.

22 Secondly, it was submitted that the evidence before the court had failed to disclose "one way or the other" the native title rights of any groups other than the Yugara or the Turrbal. That also may be accepted so far as it goes, but, to the extent that this submission implies that there are other groups holding native title in relation to the land and waters of the claim area, it must be regarded as tendentious at best. A more accurate statement would be to say that there was no suggestion in the evidence of the existence of any group – Yugara, Turrbal or otherwise – which held rights and interests of this kind. Neither, of course, was there any basis in the evidence to find that the normative system of laws and customs which inferentially existed at sovereignty within, and beyond, the claim area had continued substantially uninterrupted to the present time.

23 The original Turrbal application, involving an area which encompassed, and went beyond, the claim area, was made on 30 September 1998 and was notified to the public under s 66(3)(d) of the Act on 13 December 2000. It would, on my view, be both unrealistic and discordant with the statutory scheme were the court not to recognise the reality of the opportunity which the "other groups" referred to in the QSNTS submission subsequently had to make their own claims, or at least to make their presence known as respondents to the existing claims. Save for one respondent to whose circumstances I shall come later, the Yugara people were the only group to avail themselves of this opportunity. In the circumstances, I am not prepared to infer, on a no more solid basis than the confinement of the existing proceedings to the Turrbal and Yugara applications, that there are, in probability, other groups which would have potentially viable claims in relation to the claim area.

24 Thirdly, it was submitted that the court "merely concluded" that the Yugara and the Turrbal people were not entitled to a native title determination, "and did not embark upon on a consideration of who is, or might be, entitled to the benefit of such a determination"; and had not "determined that the pre-sovereignty normative system of laws and customs has not continued in the relevant area". The second aspect of this submission must be rejected. The court did determine that the pre-sovereignty normative system of laws and customs had not continued in the relevant area. It is true that that determination was made upon the evidence in the case, and that the evidence was called by the Yugara and Turrbal applicants. But the question to which that evidence was addressed, and the answer which it yielded, were concerned with the continuity of society as such, rather than with the rights and interests of the applicant groups, or of either of them.

25 In other respects, this aspect of the QSNTS submission goes little further than to re-formulate the grounds with which I have already dealt. Of course the court did not embark upon a consideration of who, other than the applicants, might be entitled to the benefit of a positive native title determination. The applicants were the only parties before the court who claimed the making of such a determination. If there were, at the appropriate stage in the proceeding, others who had an interest in having a determination made in their favour, they must be taken to have known that the proceeding was on foot, and to have had the opportunity to bring their claims forward.

26 Fourthly, it was submitted by QSNTS that alternative claimant applications were "conceivable" in that the evidence disclosed "the possible existence of other traditional societies at sovereignty" in the claim area. In support of this aspect of its submission, counsel for QSNTS read the affidavit of Keven James Smith sworn on 4 February 2015. In that affidavit, Mr Smith said:

Since mid-2010 QSNTS has been undertaking a significant native title research project in part of South East Queensland which includes the Claim Area. That research project, which is known as the South East Regional Research Project or SERRP, is being undertaken under the s. 203BJ(b) NTA function. That research has involved QSNTS deploying internal research staff, contracting 2 external consultant anthropologists, Dr Anthony Redmond and Dr Kevin Mayo and an external consultant historian, Dr Fiona Skyring. I expect that the research will finally be concluded with the delivery of Dr Anthony Redmond's final report in April this year. Indications from the research so far suggest that credible evidence exists to support native title determination applications within the research area, including potentially in relation to the land and waters within the claim area. That is not to say that QSNTS has an intention to immediately advise potential claim groups that a claim or claim [sic] ought to be authorised in the short term, the ultimate development and authorisation of a claim or claims arising out of the research project will require a significant amount of discussion and explanation with and among potential native title holders in the research area.

The whole of the land and waters claimed by Turrbal People and Yugara Yugarapul People fall within the area covered by the SERRP. Until the SERRP is completed, it is not possible for QSNTS to identify what, if any, people may hold native title within the area. Work previously undertaken by QSNTS as part of the SERRP influenced QSNTS's decision not to support the claim groups in these matters.

27 The SERRP research project has been relevant in interlocutory applications made on two previous occasions in this proceeding. First, on 29 November 2012, the State applied unsuccessfully to have the hearing of the applicants' claims deferred until after the results of the research were known. And secondly, on 18 October 2013 the State applied, again unsuccessfully, for a report by Dr Anthony Redmond entitled "Comments on the Yagarabal [sic] and Turrbal claim areas and claimant groups", and for a report by Dr Kevin Mayo entitled "Preliminary Genealogical Report for South-East Region Research Project (SERRP)", apparently dealing with matters that arose in the course of the SERRP research project, to be admitted into evidence.

28 It is now put on behalf of QSNTS (which was not itself a party to either of those interlocutory applications) that the final report from the research project is expected to be to hand in April of this year, and is likely to present credible evidence to support native title determination applications within an area which "potentially" includes the claim area. That is to say, save for the fact that the information potentially soon to hand will be final in nature, rather than provisional as was the situation, apparently, in November 2012 and October 2013, what is now being proposed is the very course which the court rejected on those occasions. Without re-traversing the discretionary considerations which moved the court to reject that course previously, there was, quite clearly, a public interest in bringing this long-running proceeding to trial. In cases of this nature, evidentiary perfection will rarely be achievable, and there must be a point at which, subject to compliance with the requirements of procedural fairness, the parties are required to conduct their cases in court.

29 Neither of the applicant groups sought the deferral of the trial to await the outcome of the SERRP research. Both opposed the State's application in October 2013. They were content to have the case proceed on the evidence which had been filed in accordance with the court's directions. The State now presses for the making of a negative native title determination, and submits that the imminence of the delivery of Dr Redmond's final report is no proper ground for not doing so.

30 I appreciate that it is not the interests of the applicants which must now be considered, since they have both run and lost their cases. Rather, it is the possibility that Dr Redmond's report, when delivered, will disclose the existence of other groups who may have viable native title claims that informs the position put to the court by QSNTS. As against that, there is a persuasive argument that it is now too late for such a position to be advanced in this proceeding, even in a setting in which the making of a negative native title determination is under contemplation. There would be, in my view, something odd about a system which permitted successive native title applications to be made with respect to the same area of land on the ground that more information had come to hand, and in which the only persons who could not benefit would be those who had taken the trouble to bring their cases forward in a timely way (ie, because the claims determined in those cases would be res judicata).

31 QSNTS clearly knew of the existence of this proceeding, and inferentially knew the broad nature of the applications made in November 2012 and October 2013. As it seems to me, the prosecution of the present proceeding to a conclusion, involving the making of a determination of native title as defined in the absence of any assistance from, or intervention based on, the outcome of the SERRP research was necessarily implicit in the rulings which the court made on those occasions. There is a strong public interest in the finality of litigation and, as every litigant knows, parties generally have no alternative but to marshal their evidence within the time frames which the court permits for the purpose. As I have mentioned above, oftentimes that will mean that perfection is not achieved. In the view I take, however, if I now act as proposed by QSNTS, save only for the fact that the Turrbal and Yugara applicants, alone of all potential claimant groups, will be disqualified from relying on the new material, the rulings of November 2012 and October 2013 might as well never have been made.

32 My conclusion on this aspect, therefore, is that the imminent delivery of Dr Redmond's final report does not make a positive contribution to the QSNTS case that a negative native title determination should not be made.

33 Fifthly, it was submitted by QSNTS that there is evidence that a group other than the applicants "might have a realistic claim". This is just an elaboration on the fourth point, and has been sufficiently canvassed in what I have said above.

34 Sixthly, it was submitted by QSNTS, rather boldly in the circumstances, that the applicants and the State were the only parties "that played an active part in the substantive proceedings", that the applicants "did not have the assistance of legal representation", and that, therefore, "the court did not have the assistance of anyone advocating for a potential third group as being potential native title holders". Indeed. If there were a third group, actually or potentially, or if there were "anyone advocating" for such a group, the time is now well past for them, or for him or her, to advance a justiciable claim.

35 For the above reasons, I reject the grounds advanced by QSNTS for declining to conclude the current proceeding by the making of a negative native title determination.

36 Like QSNTS, the eighth respondent Eddie Ruska submits that the Turrbal and Yugara applications should be dismissed, and that a negative native title determination should not be made. Unlike QSNTS, however, Mr Ruska has been a respondent in the proceeding since 15 December 2011. It seems that his purpose of becoming a respondent was to resist the applicants' claims by demonstrating that he was himself the holder of native title in the claim area. But, on 26 February 2013, Mr Ruska filed a notice stating that he did not wish to take an active part in the proceeding (the notice actually stated that he did wish to take an active part, but it was intended to state, and was understood by its recipients as stating, that he did not wish to take an active part). Consistently with that notice, Mr Ruska filed no evidence upon which he would rely at trial. He did not appear on the trial of the proceeding. Then, on 1 April 2014 when the court sat again in circumstances to which I referred in paras 236-240 of my reasons of 27 January 2015, Mr Ruska appeared by his solicitor and sought to tender an affidavit which he had affirmed on 1 May 2012 for the purposes of an interlocutory proceeding in the case. The affidavit set out what he knew about his ancestry, and details of his relationship with some of his forebears. That tender was rejected.

37 Mr Ruska now relies on that same affidavit – affirmed on 1 May 2012 – in support of his opposition to the making of a negative native title determination. He does so, as it seems to me, no longer by way of opposition to the applicants' claims (which have been resolved adversely to them), but by way of foreshadowing an occasion in the future when his own claim will be before the court. But his solicitor has made it quite clear that he does not have the resources to make, or to prosecute, a native title application on his own. Rather, he proposes to throw in his lot, as it were, with QSNTS, and submits that the court should do as QSNTS submits and withhold the making of a negative native title determination pending the release of Dr Redmond's report in April.

38 Aside from the QSNTS position with which I have dealt, the position adopted by Mr Ruska involves the proposition that a person who has grounds for a belief, and does believe, that he holds native title in relation to an area of land or waters may participate by way of non-active respondency to the claim of another group over that land and those waters, may decline to make his own application and have it joined with the existing one, and may then, after the existing case is resolved unfavourably for the applicants in it, make his own application for recognition of native title. For someone to be permitted to proceed in that way would, in my view, bring the administration of native title claims in the court into disrepute. There is, in my view, a strong public interest in having every known claim over a defined area brought forward for adjudication in the one proceeding. The Yugara applicants very sensibly, and responsibly, recognised that principle, notwithstanding that they too were self-evidently stretched for resources in the conduct of their case. Had Mr Ruska wanted to make a native title claim in relation to the claim area, he should have done so.

39 This is not a theoretical, or purely technical, objection to the way that Mr Ruska has proceeded. So far as I can see, one of the apical ancestors upon whom he would rely – the main one, it seems – is Kerwalli, to whom I referred in paras 290-292 of my reasons of 27 January 2015. That ancestor was mentioned in Mr Ruska's affidavit of 1 May 2012. The position is, therefore, that, while a respondent in the case, Mr Ruska sat by and allowed the relevance of Kerwalli to the existence of native title in the claim area to be litigated by the active parties, and now wants the option of commencing his own claim based upon the circumstances of this same man, and upon his connection to him. The potential which such a procedure would present for inconsistent outcomes scarcely requires emphasis.

40 For the above reasons, I take the view that Mr Ruska's situation adds nothing to the grounds upon which the State's application for the making of a negative native title determination might be resisted.

41 For more than 16 years now, there has been, in the files of the court, an application for a native title determination in relation to the claim area. Those who resist the outcome proposed by the State implicitly contend that this proceeding should be concluded without the making of any determination of native title. That is not a situation which a court exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth should find attractive.

42 For the above reasons, I propose to make final orders in the terms proposed by the State.

I certify that the preceding forty-two (42) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Jessup. |

Associate: