FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 113

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | PFIZER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 008 422 348) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Amended Originating Application filed by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission is dismissed.

2. The Applicant is to pay the costs of the Respondent.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 146 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | PFIZER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 008 422 348) Respondent |

JUDGE: | FLICK J |

DATE: | 25 FEBRUARY 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 13 February 2014 the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the “ACCC”) filed in this Court an Originating Application and a Statement of Claim. On 8 September 2014, the ACCC filed an Amended Originating Application and an Amended Statement of Claim. The Respondent was Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (“Pfizer”).

2 Pfizer has been a long-time participant in the supply of pharmaceutical products in Australia. It is ultimately owned by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer Inc is listed on the New York Stock Exchange and has its headquarters in New York. Pfizer researches, develops, manufactures and markets human prescription medicines as well as over-the-counter healthcare products and animal health products. Its human prescription medicines consist of:

medicines that are protected by patents; and

generic prescription medicines.

3 The pharmaceutical which assumes centre stage in the present proceeding is atorvastatin. Atorvastatin functions by blocking an enzyme in the liver which the human body uses to make cholesterol and results in lower levels of cholesterol.

4 Warner Lambert LLC was the registered owner, within the meaning of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the “Patents Act”), of the atorvastatin patent. That company has been owned by Pfizer since about 2000. The patent was in effect from 18 May 1987 to 18 May 2012. From 1988 until 2000 Warner Lambert LLC utilised the Australian patent and supplied a pharmaceutical product under the name “Lipitor atorvastatin” (“Lipitor”) to community pharmacies. From 2000 Pfizer was the exclusive supplier of Lipitor.

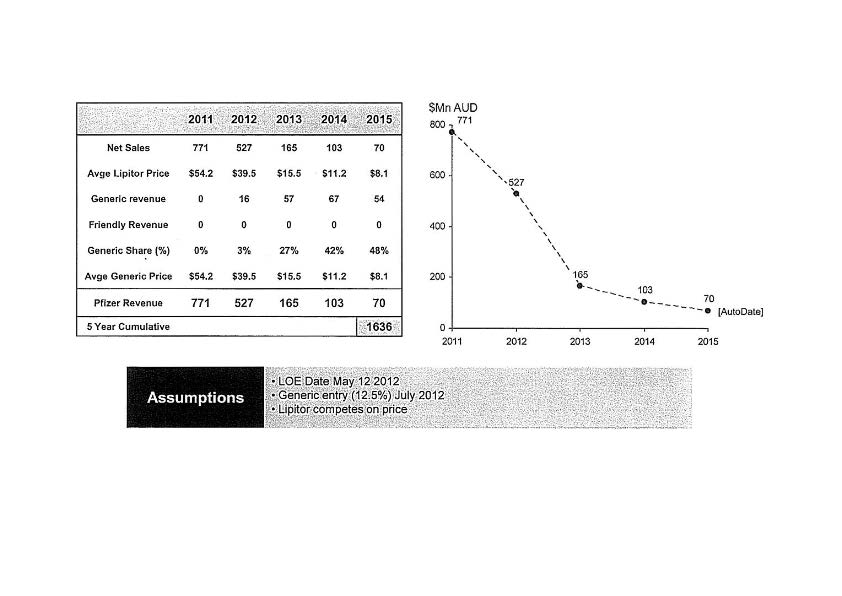

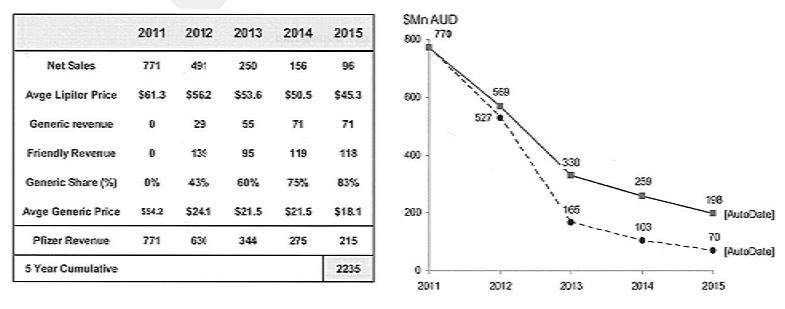

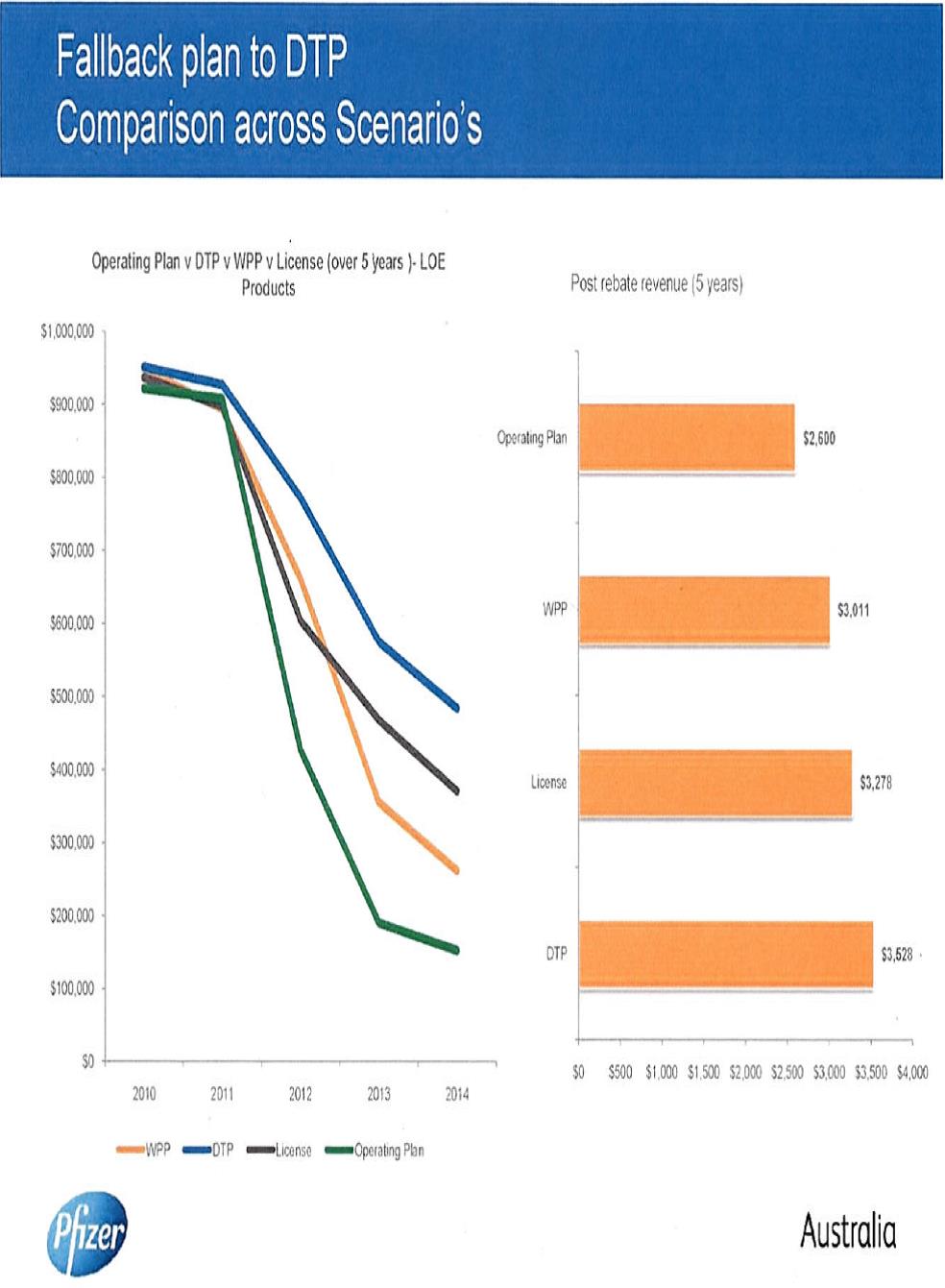

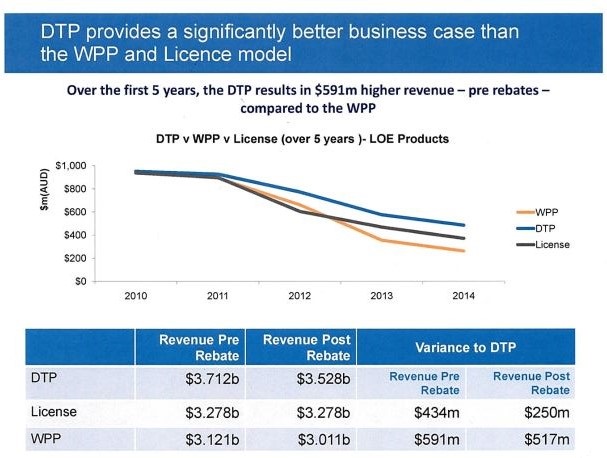

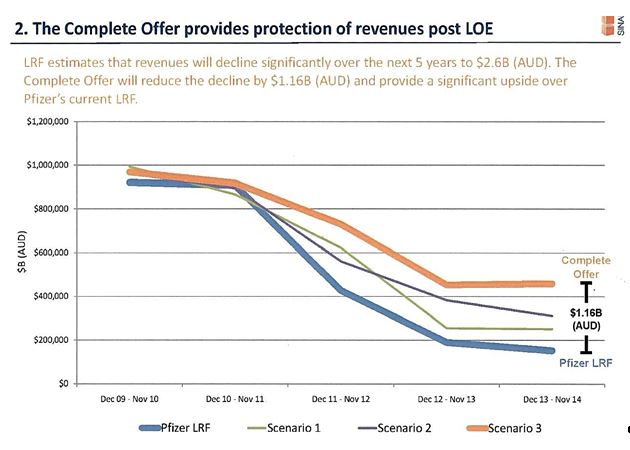

5 The patent gave Pfizer exclusive rights prior to its expiration, but other manufacturers of pharmaceutical products could manufacture and supply their own generic atorvastatin once the patent expired. Not surprisingly, there were many documents circulating within Pfizer modelling the effect of the expiration of the patent upon the revenue of Pfizer. One such document in June 2009 estimated that the value of its sales of Lipitor would fall from $771 million in 2011 to $70 million in 2015. The document revealed its projected loss of net sales and revenue and the increased impact of generic manufacturers of atorvastatin over that five year period as follows:

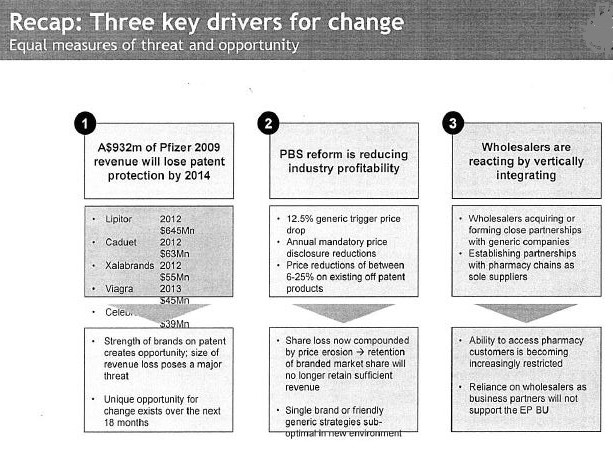

Immediately prior to the expiration of its patent, the only other supplier of atorvastatin was Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd (“Ranbaxy”). Ranbaxy was able to supply atorvastatin as from 19 February 2012 as the result of a settlement agreement arising out of unrelated proceedings. Also of concern to Pfizer was the fact that a number of patents in respect to other pharmaceutical products which it had the right to exploit were also coming to an end in the immediate future.

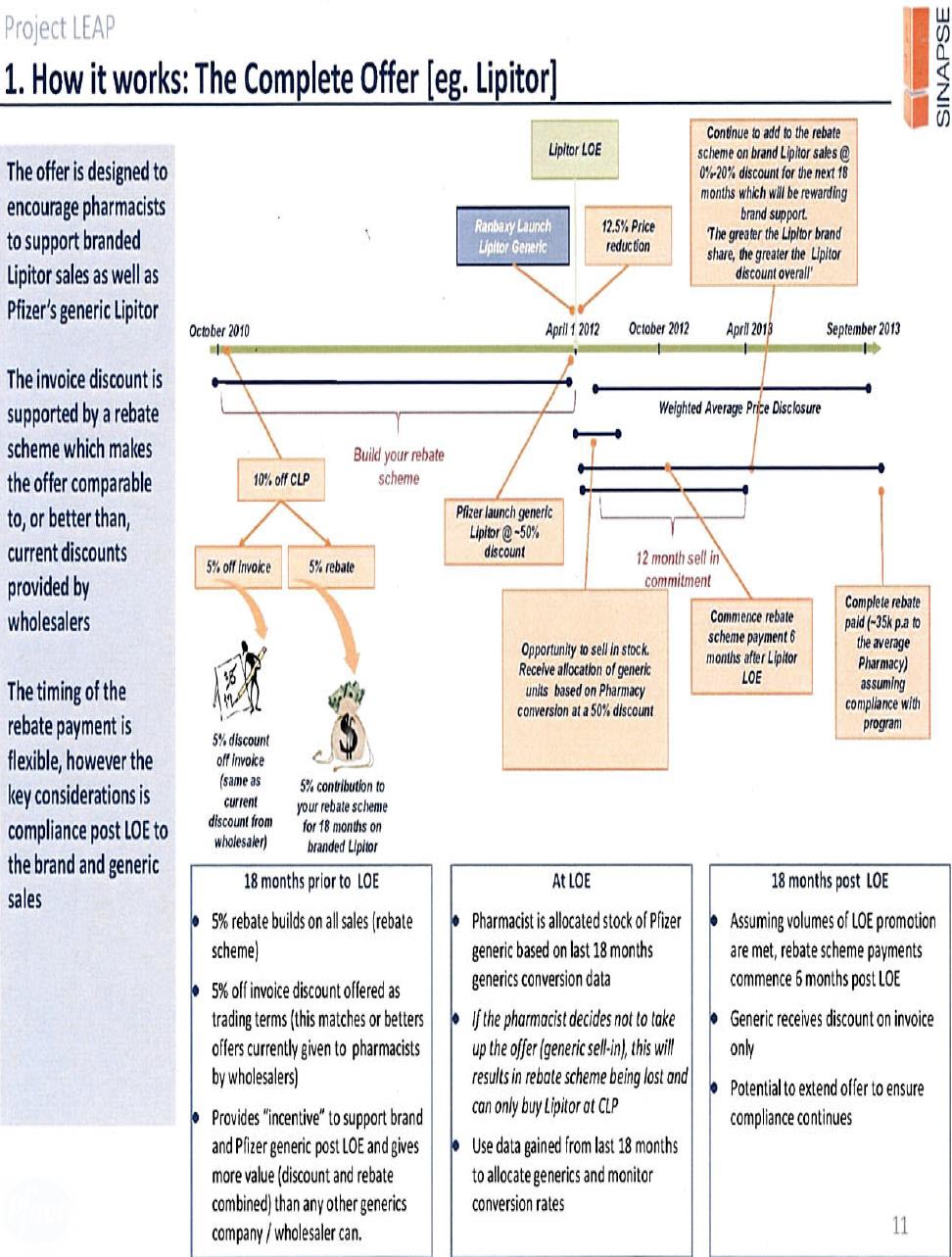

6 In anticipation of the competition it would face in 2012, Pfizer took a number of steps. In very summary form, those steps included:

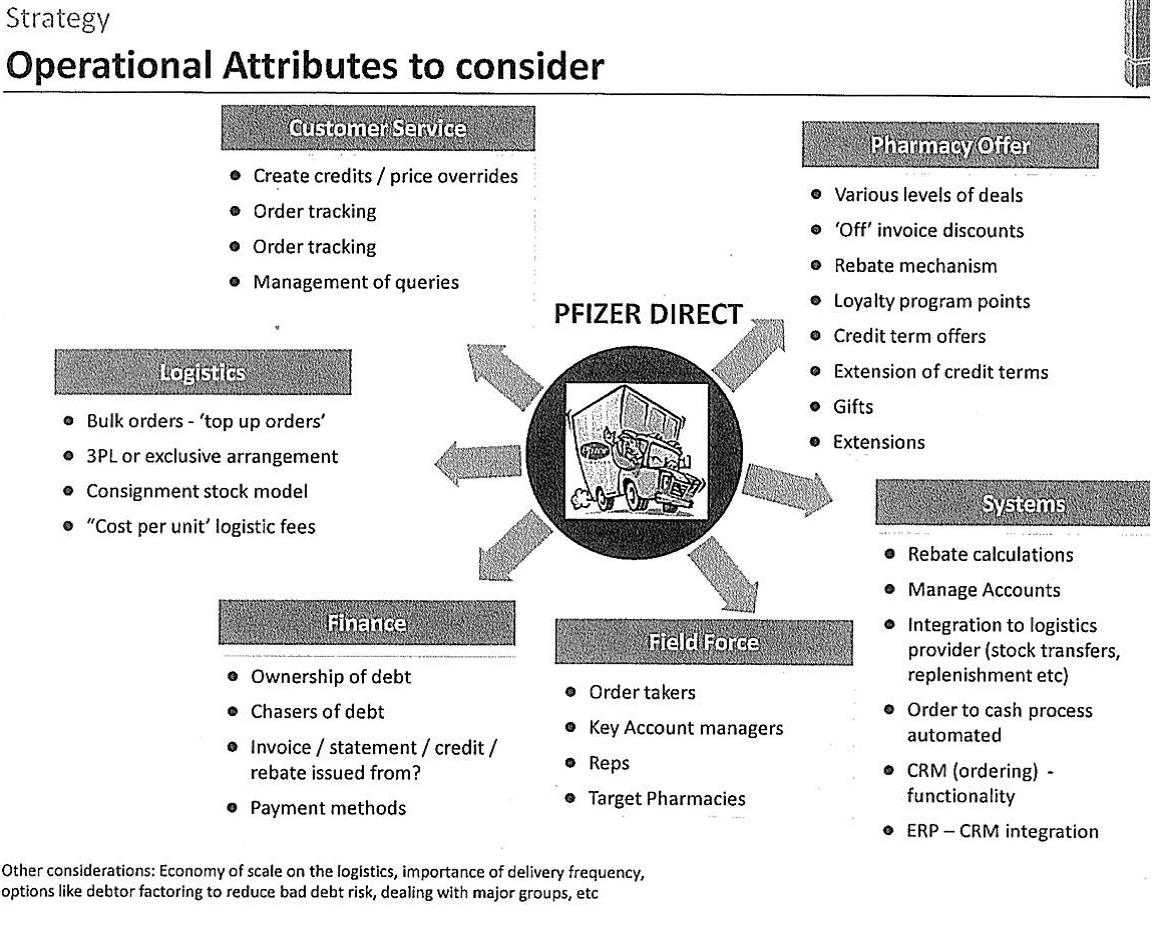

the announcement in December 2010 that it would cease supplying prescription pharmaceuticals through wholesalers and would itself commence marketing and supplying prescription pharmaceuticals exclusively direct to community pharmacies (the “Direct-to-Pharmacy Model”);

the establishment in January 2011 of an accrual funds scheme whereby funds would accrue to each community pharmacy to which it supplied prescription pharmaceuticals (the “Accrual Funds Scheme”). A percentage of the price of purchases of Pfizer pharmaceutical products was credited to an account created for each pharmacy to be rebated on terms which would be announced at a later date; and

the making of an offer in January 2012 to all, or virtually all, community pharmacies as to the terms upon which it would supply Lipitor and its own generic atorvastatin (Atorvastatin Pfizer) which, inter alia, tied the rebates that were available from the accrual fund to the quantity of Atorvastatin Pfizer that the pharmacy purchased.

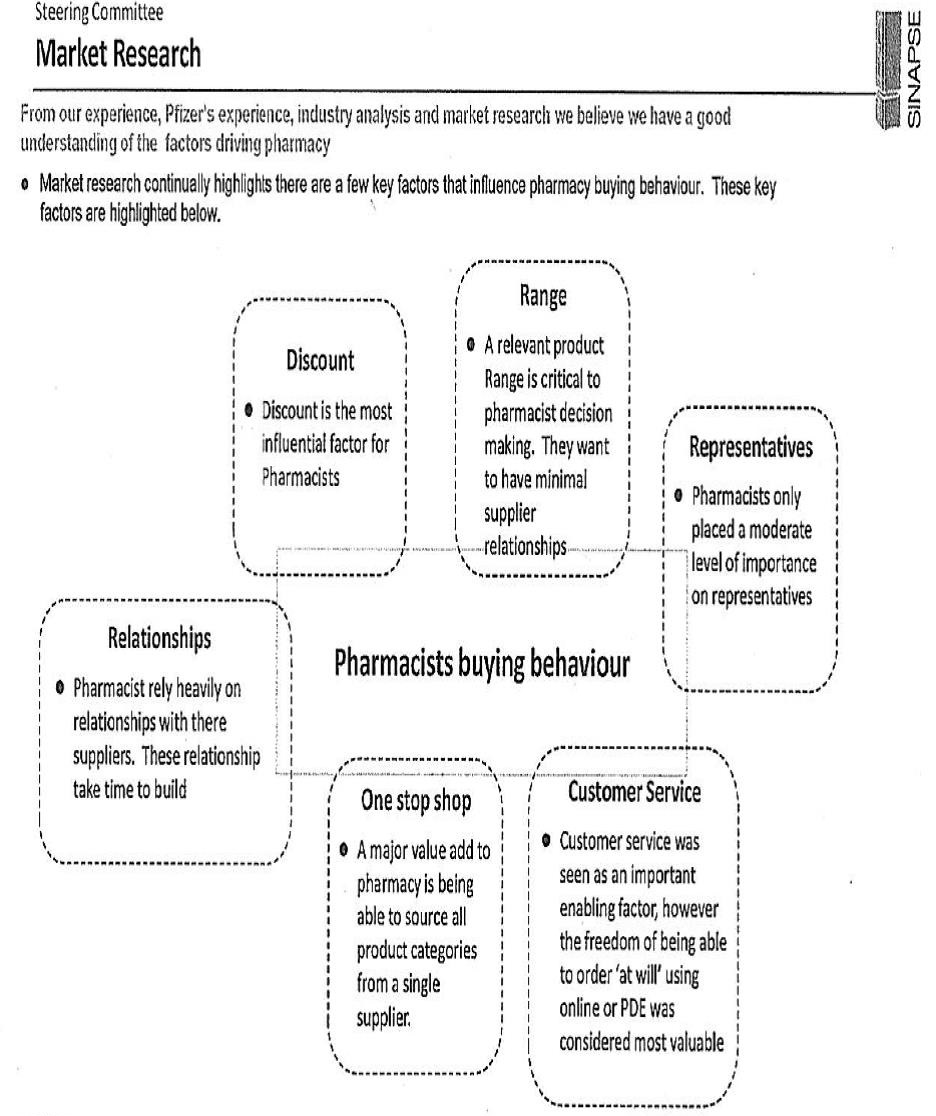

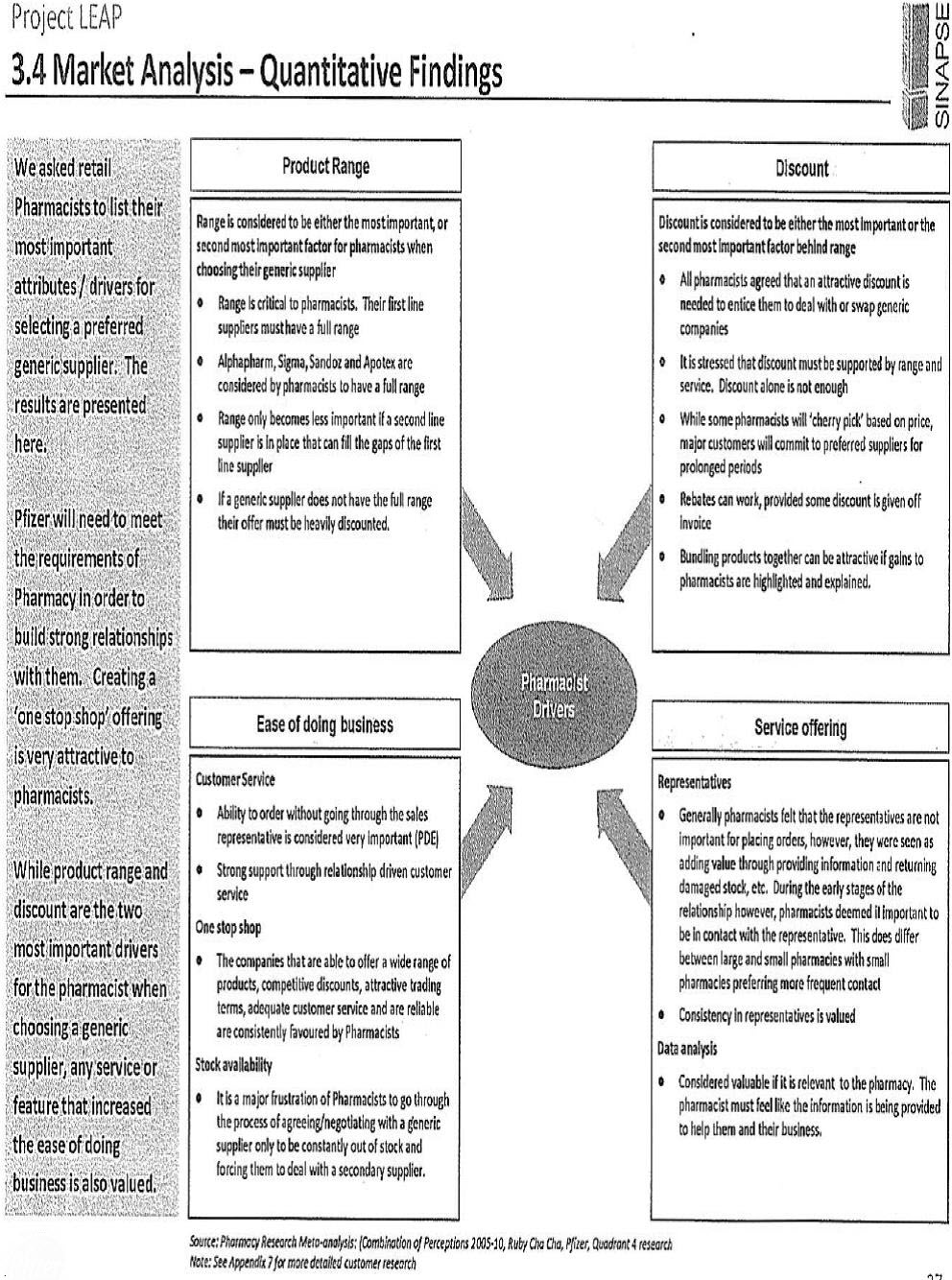

The strategy developed by Pfizer became known as “Project LEAP”. Although the emphasis placed upon protecting the “branded” product of Lipitor – as opposed to promoting Atorvastatin Pfizer – was the subject of continued consideration during the evolution of Project LEAP, a continuing concern of Pfizer throughout was the manner in which it would manage the inevitable “switching” of a patient’s use of atorvastatin from Lipitor to Atorvastatin Pfizer and from one generic version of the pharmaceutical to another. Intense competition from the generic manufacturers was inevitable; a principal concern within Pfizer was how best to manage the erosion of the revenue it enjoyed from sales of atorvastatin whilst it enjoyed exclusive rights by reason of its patent.

7 The ACCC claims that the conduct engaged in by Pfizer contravened ss 46 and 47 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the “Competition and Consumer Act”). In very summary form, the ACCC claims (inter alia) that Pfizer held a substantial degree of market power and took advantage of that power for a purpose proscribed by s 46(1)(c). The ACCC further claims that Pfizer engaged in a course of exclusive dealing pursuant to s 47(1)(d) and (e) and did so for the proscribed purpose of lessening competition. Declaratory relief is sought together with orders for the imposition of pecuniary penalties.

8 The hearing in October 2014 dealt solely with whether a contravention of the Competition and Consumer Act had occurred. Any question as to penalty was deferred.

9 That hearing took some 14 days.

10 There was, not unexpectedly, a frequently recurring debate as to the definition of the “market” in respect to which the further findings required by ss 46 and 47 were to be made. The ACCC maintained that the “market” was the Australia-wide “market” for the supply of atorvastatin to, and the acquisition of atorvastatin by, community pharmacies (the “atorvastatin market”). The Pfizer submission was that the “market” was one for the wholesale supply of pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products to community pharmacies (the “generics market”). Separate from the expected debate as to the proper characterisation of the market, however, was a further issue which fundamentally divided the parties – namely, the period of time under scrutiny for the purposes of ascertaining whether a contravention had occurred. The ACCC maintained that the period of time extended from December 2010 to at least May 2012; Pfizer maintained that the period of time had been confined by paragraphs [67] and [67A] of the Amended Statement of Claim to the period from January to May 2012.

11 It has been concluded that the ACCC definition of the relevant “market” should be accepted, namely that the “market” is the “atorvastatin market”. Pfizer’s submission that the “market”, defined in its Defence as the “Wholesale Market” – but also variously referred to as the “generics market” – is rejected. The “atorvastatin market” was the relevant “market” – irrespective of whether the inquiry is focussed on the period spanning December 2010 to at least May 2012 or that period of time between January and May 2012.

12 The fundamental division between the ACCC and Pfizer as to the period of time at which various factual inquiries were to be resolved made the balance of the fact-finding exercise in respect to both ss 46 and 47 more complex. Given this division, it has been considered prudent to make relevant findings which seek to address the principal further submissions advanced on behalf of both the ACCC and Pfizer. Within that context, it has been thus concluded that:

if the period of time to be considered is that from December 2010 through to about December 2011, Pfizer had a substantial degree of market power in the atorvastatin market and took advantage of that market power by implementing its Direct-to-Pharmacy Model, establishing the Accrual Fund Scheme but not in offering Atorvastatin Pfizer on the terms that it did;

and further concluded that:

the market power possessed by Pfizer during the period from January to May 2012 was significantly less than that which it previously enjoyed and that as from January 2012 Pfizer’s power in the atorvastatin market could no longer be described as “substantial”.

13 Whatever be the period of time properly the subject of inquiry, however, and whatever may have been the degree of market power it possessed, it has been further concluded that Pfizer did not exercise that power for a purpose proscribed by ss 46 or 47.

14 But all such findings in respect to s 46 potentially assume only secondary importance because of the manner in which the ACCC pleaded the “contraventions” of s 46 in paragraphs [67] and [67A] of the Amended Statement of Claim. Those paragraphs formed the basis of the Pfizer submission:

that the period of time the subject of inquiry in this proceeding had been confined to January to May 2012; and (more importantly)

that the manner in which the “contraventions” had been pleaded was “legally incoherent”.

The latter submission is well-founded. As pleaded, it has been further concluded that, even if the material facts pleaded in paragraphs [67] and [67A] of the Amended Statement of Claim were proved, they cannot constitute a contravention of s 46 as pleaded.

15 It was, nonetheless, considered inappropriate to resolve the ACCC’s contentions regarding the alleged contraventions of s 46 on a “pleading point”. The factual and legal issues were pursued and addressed in detail during the course of the proceeding. To a significant extent, the findings of fact which have been made as to the two periods of time contended for by the ACCC and Pfizer have really assumed lesser significance by reason of the findings made as to whether or not Pfizer was pursuing a proscribed “purpose”. But different minds may reach different conclusions both in respect to the manner in which the case was confined by paragraphs [67] and [67A] and in respect to the period of time properly the subject of inquiry. Although it is readily recognised that the present reasons for decision could have been much shorter, the course of making more findings of fact than is strictly necessary may ultimately prove to be of some future assistance to the parties.

16 However the claims advanced on behalf of the ACCC are to be approached, it is concluded that the Amended Originating Application should be dismissed with costs.

17 In explaining the reasons for reaching this conclusion it is necessary at the outset to outline both:

the terms of ss 46 and 47 and the general principles to be applied in respect to those provisions, together with other relevant statutory provisions; and

the manner in which pharmaceutical products are supplied in Australia.

It is thereafter necessary to:

set forth the manner in which Pfizer developed its strategy to respond to the looming loss of exclusivity on a number of its patented products, including Lipitor.

It is against this background:

that findings will be made in respect to both the contraventions alleged in respect to both ss 46 and 47.

The Competition and Consumer Act – Sections 46 & 47

18 The provisions of the Competition and Consumer Act which are alleged to have been contravened are ss 46 and 47. Penalties are sought pursuant to s 76.

19 There was no real dispute between the parties as to the meaning and ambit of operation of these provisions. The real dispute was whether the facts fell within these provisions. It nevertheless remains important to set forth some accepted principles in respect to each provision.

20 In respect to both ss 46 and 47 the onus lies upon the ACCC to prove the contraventions alleged: cf. John S Hayes & Associates Pty Limited v Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Limited (1994) ATPR 41-318 at 42-237 per Hill J. See also: Stirling Harbour Services Pty Ltd v Bunbury Port Authority [2000] FCA 38 at [115], (2000) ATPR 41-752 at 40,732 per French J (as his Honour then was).

Section 46 – misuse of market power

21 Section 46 provides in relevant part as follows:

Misuse of market power

(1) A corporation that has a substantial degree of power in a market shall not take advantage of that power in that or any other market for the purpose of:

(a) eliminating or substantially damaging a competitor of the corporation or of a body corporate that is related to the corporation in that or any other market;

(b) preventing the entry of a person into that or any other market; or

(c) deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct in that or any other market.

Section 46(6A) and (7) give further content to s 46(1):

(6A) In determining for the purposes of this section whether, by engaging in conduct, a corporation has taken advantage of its substantial degree of power in a market, the court may have regard to any or all of the following:

(a) whether the conduct was materially facilitated by the corporation's substantial degree of power in the market;

(b) whether the corporation engaged in the conduct in reliance on its substantial degree of power in the market;

(c) whether it is likely that the corporation would have engaged in the conduct if it did not have a substantial degree of power in the market;

(d) whether the conduct is otherwise related to the corporation's substantial degree of power in the market.

This subsection does not limit the matters to which the court may have regard.

(7) Without in any way limiting the manner in which the purpose of a person may be established for the purposes of any other provision of this Act, a corporation may be taken to have taken advantage of its power for a purpose referred to in subsection (1) notwithstanding that, after all the evidence has been considered, the existence of that purpose is ascertainable only by inference from the conduct of the corporation or of any other person or from other relevant circumstances.

Further, Section 46(3) provides:

In determining for the purposes of this section the degree of power that a body corporate or bodies corporate has or have in a market, the court shall have regard to the extent to which the conduct of the body corporate or of any of those bodies corporate in that market is constrained by the conduct of:

(a) a competitors, or potential competitors, of the body corporate or of any of those bodies corporate in that market; or

(b) persons to whom or from whom the body corporate or any of those bodies corporate supplies or acquires goods or services in that market.

Reference should also be made to s 46(3A), (3B) and (3C) which provide additional guidance on determining the degree of power in a market that a body holds.

22 The provision which assumes central relevance to the ACCC’s case is s 46(1)(c).

23 At the heart of s 46 is the need to identify the “market” under consideration.

24 It is thereafter necessary to determine whether a corporation has “power in a market”, whether that power is “substantial” and whether the corporation has taken “advantage of that power” for a proscribed “purpose”.

25 Each of these elements of s 46 has attracted its own learning.

Section 47 – exclusive dealing

26 Section 47 relevantly provides as follows:

Exclusive dealing

(1) Subject to this section, a corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in the practice of exclusive dealing.

(2) A corporation engages in the practice of exclusive dealing if the corporation:

(a) supplies, or offers to supply, goods or services;

(b) supplies, or offers to supply, goods or services at a particular price; or

(c) gives or allows, or offers to give or allow, a discount, allowance, rebate or credit in relation to the supply or proposed supply of goods or services by the corporation;

on the condition that the person to whom the corporation supplies, or offers or proposes to supply, the goods or services or, if that person is a body corporate, a body corporate related to that body corporate:

(d) will not, or will not except to a limited extent, acquire goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description, directly or indirectly from a competitor of the corporation or from a competitor of a body corporate related to the corporation;

(e) will not, or will not except to a limited extent, re-supply goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description, acquired directly or indirectly from a competitor of the corporation or from a competitor of a body corporate related to the corporation; or

(f) in the case where the corporation supplies or would supply goods or services, will not re-supply the goods or services to any person, or will not, or will not except to a limited extent, re-supply the goods or services:

(i) to particular persons or classes of persons or to persons other than particular persons or classes of persons; or

(ii) in particular places or classes of places or in places other than particular places or classes of places.

…

(10) Subsection (1) does not apply to the practice of exclusive dealing constituted by a corporation engaging in conduct of a kind referred to in subsection (2), (3), (4) or (5) or paragraph (8)(a) or (b) or (9)(a), (b) or (c) unless:

(a) the engaging by the corporation in that conduct has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition; or

(b) the engaging by the corporation in that conduct, and the engaging by the corporation, or by a body corporate related to the corporation, in other conduct of the same or a similar kind, together have or are likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition.

Section 47(13) goes on to provide the following definitions:

In this section:

(a) a reference to a condition shall be read as a reference to any condition, whether direct or indirect and whether having legal or equitable force or not, and includes a reference to a condition the existence or nature of which is ascertainable only by inference from the conduct of persons or from other relevant circumstances;

(b) a reference to competition, in relation to conduct to which a provision of this section other than subsection (8) or (9) applies, shall be read as a reference to competition in any market in which:

(i) the corporation engaging in the conduct or any body corporate related to that corporation; or

(ii) any person whose business dealings are restricted, limited or otherwise circumscribed by the conduct or, if that person is a body corporate, any body corporate related to that body corporate;

supplies or acquires, or is likely to supply or acquire, goods or services or would, but for the conduct, supply or acquire, or be likely to supply or acquire, goods or services; and

(c) a reference to competition, in relation to conduct to which subsection (8) or (9) applies, shall be read as a reference to competition in any market in which the corporation engaging in the conduct or any other corporation the business dealings of which are restricted, limited or otherwise circumscribed by the conduct, or any body corporate related to either of those corporations, supplies or acquires, or is likely to supply or acquire, goods or services or would, but for the conduct, supply or acquire, or be likely to supply or acquire, goods or services.

Section 4G further explains the meaning of the statutory concept of “lessening of competition” as follows:

Lessening of competition to include preventing or hindering competition

For the purposes of this Act, references to the lessening of competition shall be read as including references to preventing or hindering competition.

27 The provisions which are of central importance to the ACCC’s case are s 47(2)(d) and (e).

28 Section 47(1), it should be noted at the outset, “appears to have a wide application”: Parmalat Australia Pty Ltd v VIP Plastic Packaging Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 119 at [25], (2013) 210 FCR 1 at 13 per Collier J.

The market

29 It is the identification of the relevant “market” which sets the perimeters for the balance of the requirements of s 46 and which also assumes central relevance to s 47.

30 The Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the “Trade Practices Act”), when first introduced, simply defined a “market” as meaning “a market in Australia”. It was the Trade Practices Amendment Act 1977 (Cth) which inserted a form of the definition carried forward into s 4E of the Competition and Consumer Act. That provision was subsequently amended by the Trade Practices (Misuse of Trans-Tasman Market Power) Act 1990 (Cth). It now provides as follows:

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, market means a market in Australia and, when used in relation to any goods or services, includes a market for those goods or services and other goods or services that are substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, the first-mentioned goods or services.

The section does not purport to provide an exhaustive definition of the term “market” – “it merely states that a market includes goods and services substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, the goods or services under consideration”: SPAR Licensing Pty Ltd v MIS Qld Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 1116 at [42], (2012) 298 ALR 69 at 80 per Griffiths J. This decision was reversed by the Full Court but without any comment on the accuracy of the statement: SPAR Licensing Pty Ltd v MIS Qld Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 50, (2014) 314 ALR 35.

31 Given its central relevance to trade practices and consumer protection legislation, there have been repeated judicial expositions regarding the concept of a “market”. Notwithstanding the number of occasions upon which the concept has been discussed, a brief reference to some of these authorities serves as a useful reminder of the task to be undertaken by a court when resolving a question as to the definition of a “market” in any particular case.

32 Thus, for example, in an oft-cited passage, the Trade Practices Tribunal in Re Queensland Co-Operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 25 FLR 169 at 190, 8 ALR 481 at 517, said:

… We take the concept of a market to be basically a very simple idea. A market is the area of close competition between firms or, putting it a little differently, the field of rivalry between them. (If there is no close competition there is of course a monopolistic market.) Within the bounds of a market there is substitution – substitution between one product and another, and between one source of supply and another, in response to changing prices. So a market is the field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers amongst whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run, if given a sufficient price incentive. Let us suppose that the price of one supplier goes up. Then on the demand side buyers may switch their patronage from this firm's product to another, or from this geographic source of supply to another. As well, on the supply side, sellers can adjust their production plans, substituting one product for another in their output mix, or substituting one geographic source of supply for another. Whether such substitution is feasible or likely depends ultimately on customer attitudes, technology, distance, and cost and price incentives.

It is the possibilities of such substitution which set the limits upon a firm's ability to “give less and charge more”. Accordingly, in determining the outer boundaries of the market we ask a quite simple but fundamental question: If the firm were to “give less and charge more” would there be, to put the matter colloquially, much of a reaction? And if so, from whom? In the language of economics the question is this: From which products and which activities could we expect a relatively high demand or supply response to price change, i.e. a relatively high cross-elasticity of demand or cross-elasticity of supply?

See also: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2013] FCA 1206 at [554] per Dowsett J.

33 In Queensland Wire Industries Proprietary Limited v Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (1989) 167 CLR 177 at 187-188 Mason CJ and Wilson J observed:

The analysis of a s. 46 claim necessarily begins with a description of the market in which the defendant is thought to have a substantial degree of power. In identifying the relevant market, it must be borne in mind that the object is to discover the degree of the defendant’s market power. Defining the market and evaluating the degree of power in that market are part of the same process, and it is for the sake of simplicity of analysis that the two are separated. Accordingly, if the defendant is vertically integrated, the relevant market for determining degree of market power will be at the product level which is the source of that power: see the discussion of market power below. After identifying the appropriate product level, it is necessary to describe accurately the parameters of the market in which the defendant’s product competes: too narrow a description of the market will create the appearance of more market power than in fact exists; too broad a description will create the appearance of less market power than there is.

Section 4E directs that a market is to be described to include not just the defendant’s product but also those which are “substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with”, the defendant’s product. This process of defining a market by substitution involves both including products which compete with the defendant’s and excluding those which because of differentiating characteristics do not compete.

Deane J said of the concept of “market”:

The identification of relevant markets and the definition of market structures and boundaries for the purposes of determining [the case then under consideration] involves value judgments about which there is some room for legitimate differences of opinion. The economy is not divided into an identifiable number of discrete markets into one or other of which all trading activities can be neatly fitted. One overall market may overlap other markets and contain more narrowly defined markets which may, in their turn, overlap, the one with one or more others. The outer limits (including geographic confines) of a particular market are likely to be blurred: their definition will commonly involve assessment of the relative weight to be given to competing considerations in relation to questions such as the extent of product substitutability and the significance of competition between traders at different stages of distribution. While actual competition must exist and be assessed in the context of a market, a market can exist if there be the potential for close competition even though none in fact exists. A market will continue to exist even though dealings in it be temporarily dormant or suspended. Indeed, for the purposes of the Act, a market may exist for particular existing goods at a particular level if there exists a demand for (and the potential for competition between traders in) such goods at that level, notwithstanding that there is no supplier of, nor trade in, those goods at a given time — because, for example, one party is unwilling to enter any transaction at the price or on the conditions set by the other. It is, however, unnecessary to pursue that question for the purposes of the present appeal: (1989) 167 CLR at 195-196.

In the same case, Dawson J made the following observations:

Lying behind [the questions regarding a defendant’s degree of market power and what would constitute taking advantage of that market power] is the concept of the market, a concept which is sometimes dealt with in a more complex manner than is necessary. A market is an area in which the exchange of goods or services between buyer and seller is negotiated. It is sometimes referred to as the sphere within which price is determined and that serves to focus attention upon the way in which the market facilitates exchange by employing price as the mechanism to reconcile competing demands for resources … In setting the limits of a market the emphasis has historically been placed upon what is referred to as the “demand side”, but more recently the “supply side” has also come to be regarded as significant. The basic test involves the ascertainment of the cross-elasticities of both supply and demand, that is to say, the extent to which the supply of or demand for a product responds to a change in the price of another product. Cross-elasticities of supply and demand reveal the degree to which one product may be substituted for another, an important consideration in any definition of a market … : (1989) 167 CLR at 198-199.

His Honour continued:

Important as they are, elasticities and the notion of substitution provide no complete solution to the definition of a market. A question of degree is involved — at what point do different goods become closely enough linked in supply or demand to be included in the one market — which precludes any dogmatic answer … The process is an inexact one as may be illustrated by reference to the concept of a sub-market which has been employed from time to time. In Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd … the Trade Practices Tribunal observed:

“The distinction between markets and sub-markets can be merely one of degree. Sub-markets are the more narrowly defined, typically registering some discontinuity in substitution possibilities. Where the defining feature of a market is the existence of close substitutes (whether in demand or supply), the defining feature of a sub-market is the existence of still closer and more immediate substitutes. Sub-markets may be especially useful in registering the short-run effects of change; but they may be misleading if used uncritically to assess long run competitive effects.”

Too rigid an approach in defining a market is apt to lead to unrealistic results … But the existence or non-existence of sales of a product cannot conclude whether a market exists or not. It must be sufficient to constitute a market that there is a product for exchange, regardless of whether exchange or negotiation for exchange has actually taken place.

In truth, the need to define the relevant market arises only because the extent of market power cannot be assessed otherwise than by reference to a market: (1989) 167 CLR at 199-200.

34 Similarly, Wilcox J in Trade Practices Commission v Australia Meat Holdings Pty Ltd (1988) 83 ALR 299 at 317 adopted the submission which defined a “market” as follows:

“A market is the field of activity in which buyers and sellers interact, and the identification of market boundaries requires consideration of both the demand and supply side. The ideal definition of a market must take into account substitution possibilities in both consumption and production. The existence of price differentials between different products, reflecting differences in quality or other characteristics of the products, does not by itself place the products in different markets. The test of whether or not there are different markets is based on what happens (or would happen) on either the demand or the supply side in response to a change in relative price.”

35 Finally, reference should also be made to Australian Gas Light Company v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCA 1525, (2003) 137 FCR 317 at 426-427 where French J (as his Honour then was) observed:

[378] The concept of market describes, in a metaphorical way, an area or space of economic activity whose dimensions are function, product and geography. A market may be defined functionally by reference to wholesale or retail activities or a combination of both. The concept of product encompasses goods and services and, having regard to the definition of “market” in s 4E, includes the range of goods or services which are substitutable for or competitive with each other.

[379] The process of market definition was expounded in QCMA where the Tribunal defined “market” as the area of close competition between firms and observed that substitution occurs within a market between one product and another, and between one source of supply and another in response to changing prices (at 190):

So a market is the field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers amongst whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run, if given a sufficient price incentive.

In Re Tooth & Co Ltd (1979) 39 FLR 1, the Tribunal identified the task of market analysis as involving:

1. Identification of the relevant area or areas of close competition.

2. Application of the principle that competition may proceed through substitution of supply source as well as product.

3. Delineation of a market which comprehends the maximum range of business activities and the widest geographic area within which, if given a sufficient economic incentive, buyers can switch to a substantial extent from one source of supply to another and sellers can switch to a substantial extent from one production plan to another.

4. Consideration of longrun substitution possibilities rather than shortrun and transitory situations recognising that the market is the field of actual or potential rivalry between firms.

5. Selection of market boundaries as a matter of degree by identification of such a break in substitution possibilities that firms within the boundary would collectively possess substantial market power so that if operating as a cartel they could raise prices or offer lesser terms without being substantially undermined by the incursions of rivals.

6. Acceptance of the proposition that the field of substitution is not necessarily homogeneous but may contain submarkets in which competition is especially close or especially immediate. This is subject to the qualification that competitive relationships in key submarkets may have a wide effect upon the functioning of the market as a whole.

7. Identification of the market as multidimensional involving product, functional level, space and time.

Of particular importance in respect to each of these expositions of the concept of “market” are the continued references to goods or services which are “substitutable for or competitive with each other” and the focus upon the identification of a “field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers amongst whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run …”. See also: Karsh, ‘The Role of Supply Substitutability in Defining the Relevant Product Market’, (1979) 65 Virginia L Rev 129.

36 However the concept of a “market” may be defined, it must be recognised that “a market is not an artificial economic construct but rather a place, actual or nominal but recognisable not just by economists but also by its participants, be they suppliers or consumers, in which forces of supply and demand interact in the conduct of trade, a profession or commerce”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Ltd [2013] FCA 1313 at [108], (2013) 307 ALR 209 at 234 per Logan J.

37 With specific reference to the terms of s 4E, it has long been recognised that the section refers to both a market in which goods are “substitutable” and “otherwise competitive with” other goods. The “better view” as to the construction of s 4E, it has been said, “is that s 4E addresses constraints upon the supply or acquisition of the relevant goods or services” and in that context “the word ‘substitutable’ is used in a narrow sense whilst the words ‘or otherwise competitive with’ include degrees of ‘substitutability’”: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166 at [621], (2009) 182 FCR 160 at 295 per Dowsett and Lander JJ. However construed, s 4E confirms that the concept of substitution is basic to the process of market definition: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited [2014] FCA 1157 at [213] per Perram J.

A substantial degree of power in a market – s 46(1)

38 Section 46(1) places constraints on a corporation which “has a substantial degree of power in a market…”.

39 “Market power”, it has been said, “means capacity to behave in a certain way (which might include setting prices, granting or refusing supply, arranging systems of distribution), persistently, free from the constraints of competition”: Melway Publishing Pty Limited v Robert Hicks Pty Limited [2001] HCA 13 at [67], (2001) 205 CLR 1 at 27 per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

40 One of the considerations relevant to determining whether a corporation has “market power”, indeed a “primary consideration”, is whether there are “barriers to entry”: Eastern Express Pty Limited v General Newspapers Pty Limited (1992) 35 FCR 43 at 62. Lockhart and Gummow JJ there observed:

Market power is concerned with power which enables a corporation to behave independently of competition and of the competitive forces in a relevant market.

The primary consideration in determining market power must be taken to be whether there are barriers to entry into the relevant market. …

The existence of a patent is but one of the factors that may create a barrier to entry: cf. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Boral Ltd [1999] FCA 1318 at [140], (1999) 166 ALR 410 at 438 per Heerey J.

41 Although the meaning of the term “substantial” may still remain the subject of “inconclusive debate” (cf. Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2002] FCAFC 213 at [98], (2002) 118 FCR 236 at 264 per Whitlam, Sackville and Gyles JJ), the same term as used in s 45D of the Trade Practices Act was the subject of the following comments by Bowen CJ in Tillmanns Butcheries Pty Ltd v Australasian Meat Industry Employees' Union (1979) 42 FLR 331 at 338-339:

The next question is whether the conduct was engaged in for the purpose of causing substantial loss or damage to the business of Tillmanns. To constitute a contravention of s. 45D the purpose of causing substantial loss or damage must exist. …

The word “substantial” would certainly seem to require loss or damage that is more than trivial or minimal. According to one meaning of the word the loss or damage would have to be considerable … However, the word is quantitatively imprecise; it cannot be said that it requires any specific level of loss or damage. No doubt in the context in which it appears the word imports a notion of relativity, that is to say, one needs to know something of the circumstances of the business affected before one can arrive at a conclusion whether the loss or damage in question should be regarded as substantial in relation to that business.

Deane J there also observed:

The word “substantial” is not only susceptible of ambiguity: it is a word calculated to conceal a lack of precision. In the phrase “substantial loss or damage”, it can, in an appropriate context, mean real or of substance as distinct from ephemeral or nominal. It can also mean large, weighty or big. …

In the context of s. 45D (1) of the Act, the word “substantial” is used in a relative sense in that, regardless of whether it means large or weighty on the one hand or real or of substance as distinct from ephemeral or nominal on the other, it would be necessary to know something of the nature and scope of the relevant business before one could say that particular actual or potential loss or damage was substantial. As at present advised, I incline to the view that the phrase, substantial loss or damage, in s. 45D (1) includes loss or damage that is, in the circumstances, real or of substance and not insubstantial or nominal. It is, however, unnecessary that I form or express any concluded view in that regard since the ultimate conclusion which I have reached is the same regardless of which of the alternative meanings to which reference has been made is given to the word "substantial" in s. 45D (1): (1979) 42 FLR at 348.

42 A corporation does not, however, have a substantial degree of power in a market if it is unable to sustain its conduct over a reasonable period of time. Thus, for example, in Boral Besser Masonry Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 5, (2003) 215 CLR 374 at 467-468 McHugh J observed:

[287] … Firms only have a substantial degree of market power when they can persistently act in a way over a reasonable time period unconstrained by the market's forces of supply and demand. Firms that do not have “the power to raise price above cost without losing so many sales as to make the price rise unsustainable” do not have market power. Cutting prices is not evidence of market power. Any firm can do that. Market power is an economic concept and should be given its ordinary meaning. As Professors Krattenmaker, Lande and Salop point out:

“When economists use the terms ‘market power’ or ‘monopoly power,’ they usually mean the ability to price at a supracompetitive level.”

[288] Market power also includes the power to sell less in terms of quality or quantity at the same price or to sell products on terms and conditions which a firm without market power would not be able to enforce — this being an element of market power that arises in conduct other than “predatory pricing”. But market power is not equivalent to the mere cutting of prices.

A little later his Honour further observed:

[293] The concept of “market power” in s 46 shows that the section is not concerned with a one-second snapshot of economic activity. Market power can only be determined by examining what a firm is capable of doing over a reasonable time period. Whether a firm has market power — whether it has the ability to act unconstrained by competition, whether it can raise prices above competitive levels — requires an examination of the existing structure and the likely structure of the market if competitors are removed or prices rise to supra-competitive levels. Such an analysis requires an examination of the business structure and practices of the alleged offender and its competitors, their market shares and the barriers to entry (if any) into the market …: (2003) 215 CLR at 470.

Gleeson CJ and Callinan J had previously made the same point as to an ability to cut prices not necessarily being an exercise of market power as follows:

[139] … There can be circumstances in which price-cutting may be undertaken by a powerful firm, or combination of firms. But the ability to cut prices is not market power. The power lies in the ability to target an outsider without fear of competitive reprisals from an established firm, and to raise prices again later.

Before citing the observations of McHugh J at [287] and [293], Wilcox, French and Gyles JJ in Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 193 at [158], (2003) 131 FCR 529 at 568 observed:

… Market power is judged by reference to persistent rather than temporary conditions …

Purpose – ss 46(1) & 47(10)

43 Common to both ss 46(1) and 47(10) is the reference to “purpose”. Section 46(1)(c) proscribes (inter alia) a corporation taking advantage of its market power “for the purpose of deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct …”; s 47(10) provides that certain forms of exclusive dealing by a corporation are prohibited (inter alia) if the conduct “has the purpose … of substantially lessening competition”.

44 Section 4F further defines what is meant by “purpose”. That section provides as follows:

References to purpose or reason

(1) For the purposes of this Act:

(a) a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or a covenant or a proposed covenant, shall be deemed to have had, or to have, a particular purpose if:

(i) the provision was included in the contract, arrangement or understanding or is to be included in the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or the covenant was required to be given or the proposed covenant is to be required to be given, as the case may be, for that purpose or for purposes that included or include that purpose; and

(ii) that purpose was or is a substantial purpose; and

(b) a person shall be deemed to have engaged or to engage in conduct for a particular purpose or a particular reason if:

(i) the person engaged or engages in the conduct for purposes that included or include that purpose or for reasons that included or include that reason, as the case may be; and

(ii) that purpose or reason was or is a substantial purpose or reason.

(2) This section does not apply for the purposes of subsections 45D(1), 45DA(1), 45DB(1), 45E(2) and 45E(3).

45 The “purposes” referred to in ss 46(1) and 47(10) are nevertheless differently expressed and invite different inquiries.

46 In respect to both provisions, however, “purpose” is to be ascertained subjectively and not objectively: ASX Operations Pty Ltd v Pont Data Australia Pty Ltd (No 1) (1990) 27 FCR 460 at 474-475. Lockhart, Gummow and von Doussa JJ there observed:

There was no dispute that in s 46 “purpose” was to be ascertained “subjectively” rather than “objectively”. Reliance was placed by ASX and ASXO upon what was said by Toohey J in Hughes v Western Australian Cricket Association (Inc) (1986) 19 FCR 10 at 37-38 where, after reviewing the authorities, his Honour said:

“I accept the view that it is the subjective purpose of those engaging in the relevant conduct with which the court is concerned. All other considerations aside, the use in s 45(2) of ‘purpose’ and ‘effect’ tends to suggest that a subjective approach is intended by the former expression. The application of a subjective test does not exclude a consideration of the circumstances surrounding the reaching of the understanding.”

47 “Purpose” is concerned with the “intent” of the corporation engaging in the impugned conduct and is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct: Dowling v Dalgety Australia Limited (1992) 34 FCR 109 at 143. Lockhart J there referred to a number of authorities, including ASX Operations, and observed:

The determination of purpose for the purposes of s 46 is to be ascertained subjectively, in the sense of ascertaining the intent of the corporation in engaging in the relevant conduct … “Purpose” in s 46 is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct, but with purpose in the sense of motivation and reason, though, as mentioned earlier, purpose may be inferred from conduct …

The same proposition was repeated by Lockhart and Gummow JJ in Eastern Express Pty Limited v General Newspapers Pty Limited (1992) 35 FCR 43 at 66 as follows:

If a corporation has a substantial degree of power in the relevant market the question then arises whether the corporation has taken advantage of that power for one or other of the purposes proscribed by s 46(1)(a), (b) or (c). It is permissible to infer the relevant purpose under s 46: s 46(7). Further, a corporation shall be deemed to have engaged in conduct for a particular purpose if it engaged in conduct for purposes that included that purpose, and that purpose is a substantial purpose: s 4F(b). The determination of purpose for the operation of s 46 is to be ascertained subjectively, in the sense that what is to be ascertained is the intent of the corporation engaging in the relevant conduct: … “Purpose” in s 46 is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct, but with "purpose" in the sense of motivation and reason, although, as mentioned earlier, purpose may be inferred from conduct …

Lockhart J had previously observed in Dowling that purpose “will generally be inferred from the nature of the contract, the circumstances in which it was made and its likely effect”: (1992) 34 FCR at 134.

48 What needs to be proved is the actual purpose of the relevant respondent: Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 193 at [255], (2003) 131 FCR 529 at 588. Wilcox, French and Gyles JJ there went on to observe:

[256] Ascertaining the purpose for which conduct is engaged in by a party stands on quite a different footing. It would make no sense to consider that issue without paying regard to the direct and indirect evidence as to the actual intentions and purposes of the party. Of course, proof of the required purpose is not limited to direct evidence as to those purposes. Further, the court is not bound to accept such evidence. Indeed, it will normally be critically scrutinised; it is often ex post facto and self-serving. …

See also: Parmalat Australia Pty Ltd v VIP Plastic Packaging Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 119 at [28], (2013) 210 FCR 1 at 14 per Collier J.

49 More recently, the difference between “purpose” and “motive” has, perhaps, been slightly differently expressed. Gleeson CJ in News Limited v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited [2003] HCA 45 at [18], (2003) 215 CLR 563 at 573 observes:

[18] … The distinction between purpose and effect is significant. … In a case such as the present, it is the subjective purpose … that is to say, the end they had in view, that is to be determined. Purpose is to be distinguished from motive. The purpose of conduct is the end sought to be accomplished by the conduct. The motive for conduct is the reason for seeking that end. The appropriate description or characterisation of the end sought to be accomplished (purpose), as distinct from the reason for seeking that end (motive), may depend upon the legislative or other context in which the task is undertaken. …

See also: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166 at [851]-[858], (2009) 182 FCR 160 at 355-356 per Dowsett and Lander JJ.

50 One manner in which “purpose” may well be established is if a corporation exerts pressure so as to defeat a new entrant’s attempt to gain market share and a place in the market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 826, (2006) ATPR 42,123. Allsop J (as his Honour then was) there observed:

[807] There is a danger in disembodying the debate about purpose from the evidence that is available. Even if a market is workably competitive or highly competitive, the appearance of a new entrant actively engaging in the winning of market share and recognition is the working of the competitive process. The effect of a new entrant may have a detrimental effect on the business and turnover of incumbents. That, of itself, will create competitive pressures and close competition to defeat the new entrant’s attempt to gain market share and a place in the market. There may be cases where a firm acting to prevent a new entrant can explain that by a desire divorced from competition and the competitive process. If a firm has a purpose to impede or prevent the entry of a new competitor into a market lest that new entrant conduct itself competitively to wrest business from the incumbent and so damage its business, that purpose involves the process of competition. It involves preventing entry into the market and preventing a state of affairs of lost sales through additional competitive activity. Such lost sales and damage to business will, in the ordinary course call for steps, if available, in response to meet the challenge of any new entrant. The available steps may be marginal if the market is already highly competitive. To say as much, however, is only to posit even closer, or more fierce, competition. If a purpose is to prevent or impede market entry and so to prevent competitive activity, that is sufficient it seems to me to amount to a purpose directed to the competitive process. One does not need to superadd a further purpose that the success of that purpose is to affect the degree of competitive activity as opposed merely to preserving the firm’s share of revenue in a mercantilist sense. The entry of competitors is an essential attribute of the competitive process. It is the means of access for competitive trading and for pressure on incumbent firms, through their revenue and profitability, to offer more or charge less in order to retain their places in the competitive (on this hypothesis increasingly competitive) market. If the grant of new licences were seen as a competitive threat they were so seen because they were a threat to business through competitive activity. A purpose to prevent or impede such competitive activity is a purpose concerned with the process and conduct of competition: (2006) ATPR at 45,303.

51 A proscribed purpose may be made out even though a corporation maintains that it is simply seeking to “win as much business as possible”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd (No 2) [2008] FCAFC 141 at [381], (2008) 170 FCR 16 at 100 per Gyles J. The Baxter corporation was the manufacturer and supplier of sterile fluids and PD fluids. It negotiated and tendered for long-term contracts with the governments of four States and the Australian Capital Territory. It required those governments to acquire all of their sterile fluids and between 90 and 92.5% of their PD fluids from Baxter. The “bundled” prices were significantly lower than the item-by-item tender. The Commission alleged that Baxter had taken advantage of its market power in the sterile fluids market because otherwise it would not have been able, under competitive conditions, to force the States to take the bundled offer by threatening prohibitive prices for sterile fluids. The primary Judge concluded that there had not been a contravention of s 46 but that there had been a contravention of s 47. On appeal it was concluded that Baxter had a “substantial degree of power” in the Australia-wide sterile fluids market. Mansfield and Gyles JJ further concluded that Baxter’s conduct fell within s 46(1)(c). In rejecting the argument that Baxter’s conduct did not fall within s 46(1)(c), Gyles J concluded:

[381] Baxter contends that its aim was solely to win as much business as it could across the board and that its conduct was directed to achieving that result rather than harming competitors. In my view, that confuses purpose with motive. Baxter's method of winning business in the PD market was to prevent its potential competitors from competing in a meaningful way in that market because of its leverage from the substantial degree of market power it held in the sterile fluids market. The objective of maximising profit can only be achieved if there is compliance with the Act. Since Queensland Wire Industries Pty Ltd v Broken Hill Pty Company Ltd (1989) 167 CLR 177, it has been recognised that the conduct of a party with substantial power in a market may be subject to restraints to which others without power are not (see NT Power Generation Pty Ltd v Power and Water Authority (2004) 219 CLR 90 per McHugh ACJ, Gummow, Callinan and Heydon JJ at [72], [76], [85], [125] and [126]). Even if Baxter did have the purpose of winning as much business as possible, it also had the purpose of deterring or preventing others from engaging in competitive conduct in the PD market. The latter purpose was substantial (s 4F(1)(b)).

Mansfield J recited the finding of the primary Judge as to the purpose being pursued by Baxter as follows:

[179] Based upon the evidence, his Honour found that the “core … of the purpose of the bundle or tie”, or more broadly the alternative offer strategy, was to foreclose the likelihood or restrict the possibility of the Gambro or Fresenius bids for PD fluids having any realistic prospect of success. That was, he said, illustrated or reflected in the “stubbornness” of Baxter’s attitude to the request by SA for a tender for the long-term exclusive supply of sterile fluids, because a discount for exclusive supply of a volume of sterile fluids only would have exposed the Gambro and Fresenius bids for PD fluids to realistic prospects of acceptance. Baxter’s attitude was to prevent those prospects and so to protect its PD fluids revenue stream.

His Honour thereafter continued on to reach the same conclusion as that reached by Gyles J, saying:

[187] Baxter, having a substantial degree of power in the sterile fluids market, took advantage of that power by the impugned conduct. It did so to secure as much of the supply of sterile fluids and PD fluids as it could. It did so for obvious commercial reasons. In doing so, it had the purpose of shutting out Gambro and Fresenius from being able to put forward bids for the supply of PD fluids which could be accepted by the SPAs except at a significant cost penalty. The significant cost penalty existed by reason of the bundled offers, and the fact that Baxter in the sterile fluids market had a substantial degree of power, and took advantage of that power by its alternative offer strategy. Baxter did not compete separately with Gambro and Fresenius in the PD fluids market, whether by price or quality of product or service or otherwise. It sought to avoid competing with them directly by taking advantage of its market power in the sterile fluids market. Its purpose, as the primary judge found, was to deter or prevent Gambro and Fresenius from engaging in competitive conduct in the PD fluids market by shutting them out from effectively being able to compete in that market.

[188] I do not accept Baxter's alternative contention. The primary judge found, upon analysis and assessment of the evidence, that Baxter's purpose by its impugned conduct was to shut out Gambro and Fresenius from being able to effectively compete in the PD fluids market in relation to the tender invitations from the SPAs. The outcome of its alternative offer strategy shows that its purpose was fulfilled. The fact that both Gambro and Fresenius were, before the impugned conduct, its competitors in the PD fluids market and remained its competitors in that market after the impugned conduct does not mean that Baxter did not have the purpose referred to in s 46(1)(c). Nor does the fact the (sic) Gambro and Fresenius tendered in various ways for all or part of the PD fluids supply contracts available in the tendering invitations of the SPAs. Nor does the fact that, in the period of time after the impugned conduct, Gambro and Fresenius may have increased their respective market shares in the PD fluids market.

Although in dissent as to whether the conduct whether there had been a hindering of competition, Dowsett J had there also observed:

[329] Purpose, effect and likely effect are quite distinct concepts. To establish that Baxter had a proscribed purpose, it was necessary to show an actual, subjective intention. As always, purpose must be distinguished from motive, but subjective purpose must still be demonstrated. Purpose may be inferred from statements and actions in the light of common experience. In the present context, effect is to be distinguished from likely effect. The effect of conduct is its outcome as demonstrated by evidence concerning actual events. Likely effect involves a prediction as to whether particular events will flow from relevant conduct. Likely effect may vary, depending upon the time at which the prediction is made. It may be made before, at the time of, shortly after, or long after the relevant causal conduct.

An application for special leave to appeal was refused but without prejudice to the ability to institute a further application at the conclusion of the litigation: Baxter Healthcare Pty Limited v ACCC [2009] HCATrans 20.

52 Just as “purpose” must be distinguished from “motive” (as referred to by Dowsett J in Baxter), “effect” must also be distinguished from “motive”. Thus, for example, in Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 193, (2003) 131 FCR 529 at 587 Wilcox, French and Gyles JJ observed:

[249] We turn to the subject of purpose. A person may have the purpose of securing a result which it is, in fact, impossible for that person to achieve. That no doubt explains the reference to purpose, in para (a) of s 47(10) of the Act, as an alternative to effect and likely effect. The paragraph is satisfied if the relevant corporation has the requisite purpose, regardless of whether or not that purpose has been, or was or is likely to be, achieved. It may conceivably be satisfied even in a case where the court finds the purpose could never in fact have been achieved; although that finding would be relevant in determining whether to infer the proscribed purpose.

Purpose -v- taking advantage – s 46

53 Section 46(1) provides that a corporation that has a substantial degree of power in a market “shall not take advantage of that power … for the purpose of …”. And s 46(6) elaborates upon those matters to which a Court may have regard when determining whether a corporation has taken advantage of any such power.

54 These references in s 46 to “purpose” and to the “taking advantage” of power are, self-evidently, distinct elements. A corporation may pursue conduct which takes advantage of its market power without intending to injure a competitor. Caution should thus be exercised to avoid equating a finding that a corporation has taken advantage of its substantial market power with a conclusion that it did so for a purpose proscribed by s 46.

55 The overlap between “purpose” and the “taking advantage” of market power is nevertheless demonstrated by the facts in Melway Publishing Pty Limited v Robert Hicks Pty Limited [2001] HCA 13, (2001) 205 CLR 1. Melway was a publisher of a street directory in Melbourne. It held in excess of 80-90% of the retail market. For a number of years it had adopted a distribution system which divided the retail market into segments and had selected wholesale distributors allocated to defined segments. Melway decided to terminate the appointment of Robert Hicks Pty Ltd as a distributor. Robert Hicks thereafter sought to purchase 30,000-50,000 directories from Melway. Melway refused. Litigation followed. The primary Judge found for the distributor: Robert Hicks Pty Ltd (t/as Auto Fashions Australia) v Melway Publishing Pty Ltd (1998) 42 IPR 627. In doing so, his Honour concluded:

… It is only by virtue of its dominant position in the Melbourne directory market and the absence of a competitive market that Melway can afford, in a commercial sense, to withhold from supplying 30,000—50,000 directories at its usual wholesale price and terms to Auto Fashions. If Melway lacked substantial market power — in other words, if it were operating in a competitive market — it is highly unlikely that it would stand by, without any effort to compete, and allow Auto Fashions to secure its significant supply of directories from a competitor. Put another way, one would not expect to observe a refusal to supply 30,000—50,000 directories in a competitive market. Accordingly, in refusing supply Melway has taken advantage of its market power: (1998) 42 IPR at 641.

An appeal was dismissed by a majority: Melway Publishing Pty Ltd v Robert Hicks Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 664, (1999) 90 FCR 128. The appeal to the High Court was allowed: Melway Publishing Pty Limited v Robert Hicks Pty Limited [2001] HCA 13, (2001) 205 CLR 1. In setting out the facts, Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ said:

[30] In the present case, there was no suggestion of a purpose of preventing the respondent from becoming a wholesaler of street directories. It was never suggested that Melway had any concern, for example, to prevent the respondent from distributing the products of one of its competitors. What Melway intended to do, and did, was to terminate the respondent's Melway distributorship, with the necessary consequence that it would cease to be a wholesaler of Melway street directories. Melway was not the only possible source of supply of Melbourne street directories. It was the only possible source of Melway street directories, but that would have been the case if it only had 10 per cent of the market, or if it had no substantial degree of market power. Its ability to stop the respondent becoming a wholesaler of Melway directories resulted from the fact that it was Melway, and could appoint, or not appoint, distributors as it saw fit in its commercial interests.

[31] … [T]here are cases in which it is dangerous to proceed too quickly from a finding about purpose to a conclusion about taking advantage. That is especially so when, in a context such as the present, the purpose as referred to in s 46 is relatively narrow. The purpose presently in question is that of deterring a person from engaging in competitive conduct in a market. If a manufacturer supplies to a single distributor, or a limited number of distributors, then, from one point of view, turning down an application from a person who wishes to become an additional distributor will have the effect of preventing that person from engaging in competitive conduct. Purpose, in this connection, involves intention to achieve a result. Where distributorship arrangements are concerned, an intent to give a particular distributor exclusivity may constitute a very insecure basis for concluding that there had been a taking advantage of market power.

In reversing the decision of the primary Judge, their Honours held:

[57] There are a number of difficulties about that process of reasoning. First, it appears to assume that the 30,000—50,000 directories in question would be sales lost to Melway, and gained by its competitors, if Melway were operating in a competitive market and, in that context, the respondent sought supply. But the decision not to supply the respondent was made in a situation where the respondent was primarily seeking to take business away from existing distributors. A second, and related, difficulty is that the reasoning fails to address the question of the nature of the wholesale distribution arrangements, both of Melway and its competitors, that would exist in a competitive market. Why, for example, might there not be a competitive market for Melbourne street directories in which Melway and/or its rivals supplied direct to retailers, or in which each operated through an exclusive distributor, or a fixed number of distributors? In such a case, as in the present case, a refusal to supply Melway directories to a wholesaler, or to another wholesaler, might be regarded by Melway as unlikely to result in any reduction in total Melway sales. In a competitive market, a manufacturer does not necessarily increase total sales by selling to everyone who seeks wholesale supply, or lose market share by selling to only a small number of wholesalers or, for that matter, by selling all its product directly to retailers. Thirdly, the focus of the question is too narrow. It is only as a manifestation of Melway's wholesale distribution system that the anti-competitive effect of the refusal to supply the respondent can be judged. What must be asked is whether Melway's wholesale distributor system, involving, as it did, restriction of competition at the wholesale level, amounted to taking advantage of its market power.

[58] The most likely explanation of the assumption that, in a competitive market, a refusal of the respondent's application for supply would be a loss of 30,000—50,000 sales to Melway is that it was thought that s 46 required that assumption. But the hypothesis that Melway lacks a substantial degree of power in the market does not require the assumption that the distribution arrangements or practices of Melway and its competitors are such that they are all commercially obliged to supply anyone who seeks to become a wholesaler, or that, at the wholesale level in the market, there exists a state of perfect competition, or that a decision to confine supply to one or a small number of wholesalers will result in a loss of sales. The only purpose of the hypothesis is to seek to test whether Melway has taken advantage of its degree of market power. It is one thing to compare what it has done with what it might be thought it would do if it lacked that power. It is a different thing to compare what it has done with what it would do in circumstances that are completely divorced from the reality of the market.

Their Honours ultimately concluded:

[61] Bearing in mind that the refusal to supply the respondent was only a manifestation of Melway’s distributorship system, the real question was whether, without its market power, Melway could have maintained its distributorship system, or at least that part of it that gave distributors exclusive rights in relation to specified segments of the retail market.

See: Wright and Painter, ‘Recent developments in the application of s 46: Melway and Boral considered’ (2001) 21 Aust Bar Rev 105.

56 The expression “take advantage of that power” in s 46 limits the kind of connection between market power and purpose: Rural Press Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75, (2003) 216 CLR 53 at 76. Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ there observed:

[51] Conclusion on s 46. The words “take advantage of” do not extend to any kind of connection at all between market power and the prohibited purposes described in s 46(1). Those words do not encompass conduct which has the purpose of protecting market power, but has no other connection with that market power. Section 46(1) distinguishes between “taking advantage” and “purpose”. The conduct of “taking advantage of” a thing is not identical with the conduct of protecting that thing. … If a firm with market power has a purpose of protecting it, and a choice of methods by which to do so, one of which involves power distinct from the market power and one of which does not, choice of the method distinct from the market power will prevent a contravention of s 46(1) from occurring even if choice of the other method will entail it.

57 The overlap between an analysis of “purpose” and the “taking advantage” of power nevertheless remains. One of the central difficulties inherent in s 46 is well recognised, namely the tension between pursuing conduct for the legitimate commercial objective of being competitive as opposed to the proscribed objectives. Thus, for example, in Top Performance Motors Pty Ltd v IRA Berk (Queensland) Pty Ltd (1975) 5 ALR 465 at 468 Joske J observed:

So far as concerns the construction of s 46, the submission put forward on behalf of the applicant, which is in effect that to exercise a power is to take advantage of a power, is, in my opinion, not the proper construction of the section. In my view, exercise of its contractual right to terminate a contract for the genuine purpose of protecting legitimate trade and business interests is not taking advantage of a power of controlling a market within the meaning of s 46, and providing that there is this genuine purpose, that is enough, though it may be there would always be people who would not regard it as reasonable to exercise the power in the circumstances of any particular case. Unreasonable behaviour may go to show absence of bona fides, but it goes no further than this.

It was there concluded that the termination of a dealership agreement for the sale of Datsun motor vehicles on the Gold Coast in Queensland was for the genuine purpose of protecting legitimate trade and business interests and was not the taking advantage of market power for the purposes proscribed by s 46. A contrary conclusion was reached on the facts in Mark Lyons Pty Ltd v Bursill Sportsgear Pty Ltd (1987) 75 ALR 581.

58 Where conduct undertaken for legitimate commercial purposes ends and conduct undertaken for a proscribed purpose or purposes commences may be difficult to determine.

59 One test that may be applied to determine whether a corporation has taken advantage of its market power requires a comparison between what it has in fact done and what it would rationally do if it lacked substantial market power: Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75 at [52], (2003) 216 CLR 53 at 76 per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ; Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166 at [971]-[975], (2009) 182 FCR 160 at 381-382 per Dowsett and Lander JJ.

60 Further assistance as to whether a corporation has taken advantage of its market power is also provided by the following observations of Greenwood J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 909, (2013) 310 ALR 165 at 509-510:

[1899] In examining the evidence, I ask whether a profit maximising firm operating in a workably competitive market could in a commercial sense profitably engage in the conduct in question having regard to the business reasons identified by the witnesses, assuming such a firm is confronted with similar circumstances to those confronting Pozzolanic of asking itself whether it should enter into the original Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002 (and later engage in the further steps of maintaining the contract).

[1900] In answering that question, a practical judgment must be brought to bear having regard to the identified so-called legitimate or ordinary business rationale informing the decision-making of the firm in question in all the circumstances. Those similar circumstances in which a hypothetical firm might be called upon to decide the questions confronting Pozzolanic will, however, reflect a hypothetically competitive market in which all aspects or sources of Pozzolanic’s substantial degree of market power are stripped away so as to neutralise its market power. In all other respects, the hypothetical market will reflect the circumstances of the actual market: Commerce Commission v Telecom Corp of New Zealand Ltd [2011] 1 NZLR 577; [2010] NZSC 111.

[1901] … Judgments about such a firm engaging in the conduct must be made in circumstances where a profit maximising firm would need to take account of the constraints imposed by workable competition.

[1902] The question, put simply, is whether a firm profitability could have engaged in the conduct in question in the absence of a substantial degree of power in the relevant market. Because that question involves a hypothetical construct it must be answered by applying an objective test but one which takes into account the legitimate business reasons identified by the firm for engaging in the conduct.

Purpose of deterring or preventing – s 46(1)(c)

61 Section 46(1)(c), the provision of relevance to the present dispute, refers to the proscribed purpose of “deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct in that or any other market”.

62 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd (No 2) [2008] FCAFC 141, (2008) 170 FCR 16 at 82 Dowsett J said of this phrase:

[317] The words “deterring or preventing” also require attention. To “deter” is to “(r)estrain or discourage (from acting or proceeding) by fear, doubt, dislike of effort or trouble, or consideration of consequences”: see the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. The same dictionary defines the verb “prevent” as to “[s]top, hinder avoid. Forestall or thwart by previous or precautionary measures … Frustrate, defeat, make void (an expectation, plan, etc.). … Stop (something) from happening to oneself; escape or evade by timely action. … Cause to be unable to do or be something, stop (foll. by from doing, from being)”. The combined effect of the words “deterring” and “preventing” includes persuading a person to decide to withdraw from, not to enter or not to compete in a market, as well as making it difficult or impossible for that person to do so.

The co-existence of market power, conduct and proscribed purpose – s 46(1)

63 Section 46 “requires, not merely the co-existence of market power, conduct and proscribed purpose, but a connection such that the firm whose conduct is in question can be said to be taking advantage of its power”: Melway Publishing Pty Limited v Robert Hicks Pty Limited [2001] HCA 13 at [44], (2001) 205 CLR 1 at 21 per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

64 Similarly, s 47(10) relevantly provides that s 47(1) does not apply to the practice of exclusive dealing unless the engaging in that practice “has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition”.

Condition – s 47(2)

65 Section 47(2) provides that a corporation engages in the practice of exclusive dealing if it supplies or offers to supply goods or services on one or other of the “conditions” set forth in s 47(2)(d), (e) or (f).

66 The term “condition” appearing in s 47 does not require that the condition be legally binding; but it must have “attributes of compulsion and futurity”: SWB Family Credit Union Ltd v Parramatta Tourist Services Pty Ltd (1981) 48 FLR 445 at 464 per Northrop J.

67 But the mere fact that a “likely consequence” is exclusion will not be sufficient: Monroe Topple & Associates Pty Ltd v Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia [2002] FCAFC 197 at [71], (2002) 122 FCR 110 at 130 per Heerey J. There in issue was the manner in which the Institute provided training to persons who wished to become members. It was argued that the Institute had the power to affect competition in the support materials market for persons trying to become accredited as Chartered Accountants by reason of its exclusive right to enrol and assess candidates. Contraventions of ss 45, 46, 47 and 51AC of the Trade Practices Act were alleged. In rejecting the contention that there had been a contravention of s 47 and that the Institute had imposed a “condition” on the supply of its services, Heerey J concluded:

[104] The answer to this question must be in the negative, for two reasons. First, although “condition” in s 47(2) need not necessarily have legal or equitable force (see s 47(13)(a)), as Deane J said in Re Ku-ring-gai Co-operative Building Society (No 12) Ltd (1978) 36 FLR 134 at 168: