FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Minister for the Environment v Lucky S Fishing Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 10

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| Applicant | |

| AND: | LUCKY S FISHING PTY LTD (ACN 007 933 253) Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT:

1. DECLARES that, on 2 September 2010, the respondent contravened s 354(1)(f) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) by reason of the fact that the commercial trawling activities carried out in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve by Steven John Colville (formerly the first respondent in this proceeding) in contravention of that section on that day were undertaken by him as agent of the respondent.

2. ORDERS that, pursuant to s 481 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth), the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $34,650 for the contravention of the said Act described in the Declaration made in par 1 above.

3. ORDERS by consent that the respondent pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding, such costs to be fixed pursuant to r 40.02(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 in the lump sum of $45,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | ACD 83 of 2013 |

| BETWEEN: | MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT Applicant |

| AND: | LUCKY S FISHING PTY LTD (ACN 007 933 253) Respondent |

| JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

| DATE: | 22 JANUARY 2015 |

| PLACE: | SYDNEY (HEARD IN CANBERRA) |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The Minister for the Environment, who is the applicant in this proceeding, is responsible for the administration and enforcement of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act). The Minister is supported in those functions by the Department of the Environment (Department).

2 When the Minister commenced this proceeding, he sought declarations that, on 2 September 2010, each of Steven John Colville (Mr Colville) (formerly the first respondent in this proceeding) and the respondent, Lucky S Fishing Pty Ltd (Lucky S) (formerly the second respondent in this proceeding), contravened s 354(1)(f) of the EPBC Act. It was said that Mr Colville contravened that provision by engaging in commercial trawling activities in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve and that Lucky S did so by reason of the fact that Mr Colville’s commercial trawling activities in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve had been undertaken by him as agent of Lucky S. In addition to declaratory relief, the Minister also sought a pecuniary penalty against each of the respondents.

3 On 1 August 2013, Mr Colville died. As at the date of his death, Mr Colville was an undischarged bankrupt. On 5 December 2013, the Minister applied for leave to discontinue his case against Mr Colville upon terms that there be no orders as to the costs of that case. I granted that leave on those terms on that day. On 24 January 2014, the Minister filed a Notice of Discontinuance in respect of his case against Mr Colville thereby bringing that case to an end.

4 Notwithstanding Mr Colville’s death, the Minister pressed on with his case against Lucky S.

5 The Minister filed a Statement of Claim at the same time as he filed his Originating Application.

6 The respondents promptly filed a Defence in which Mr Colville admitted all of the allegations made against him in the Statement of Claim and Lucky S admitted all of the allegations made against it in the Statement of Claim. That Defence was filed within the time limited by the Federal Court Rules 2011 for the filing of the respondents’ Defence.

7 In addition to acting expeditiously and appropriately in relation to the allegations made against them in the Minister’s Statement of Claim, both respondents fully co-operated with officers of the Department and with the Minister’s lawyers by participating in interviews which took place in late November 2010 and by making full and frank admissions as to all relevant matters. Further, both respondents co-operated fully with the Minister’s representatives and his lawyers in the preparation of a Statement of Agreed Facts (SOAF). A comprehensive and appropriate SOAF was ultimately agreed in June 2013. That document together with all exhibits referred to therein was filed and ultimately became Exhibit A at the hearing before me. These matters justify a substantial discount of the quantum of the civil penalty to be imposed on Lucky S.

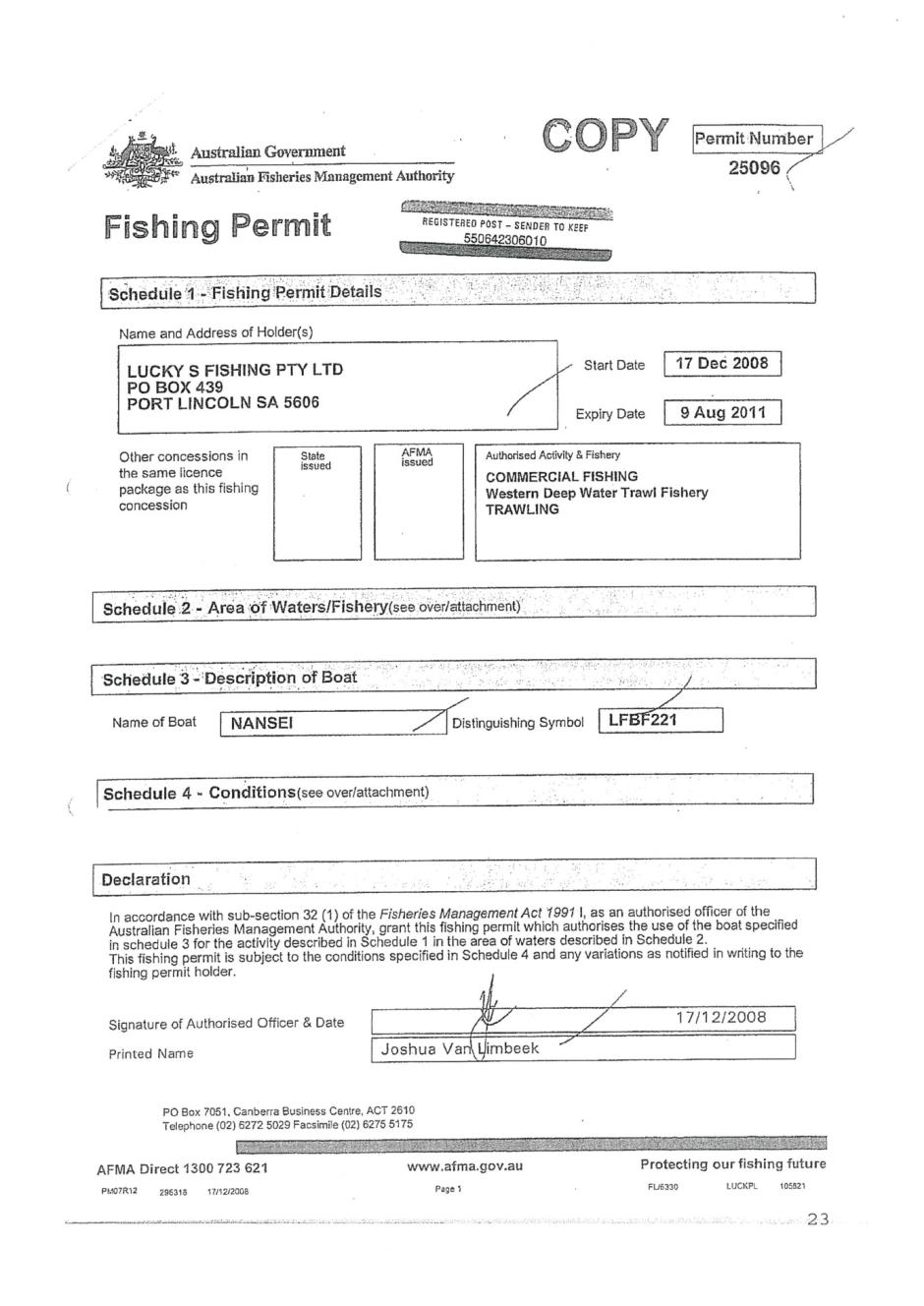

8 Under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), in a proceeding, evidence is not required to prove the existence of an agreed fact and evidence may not be adduced to contradict or qualify an agreed fact unless the Court gives leave (see s 191(2) and see also s 191(1) for the definition of agreed fact for the purposes of s 191).

9 Thus, when the matter came on for hearing, the alleged contraventions against Lucky S had been formally admitted by it and there was no dispute between the Minister and Lucky S as to the relevant facts.

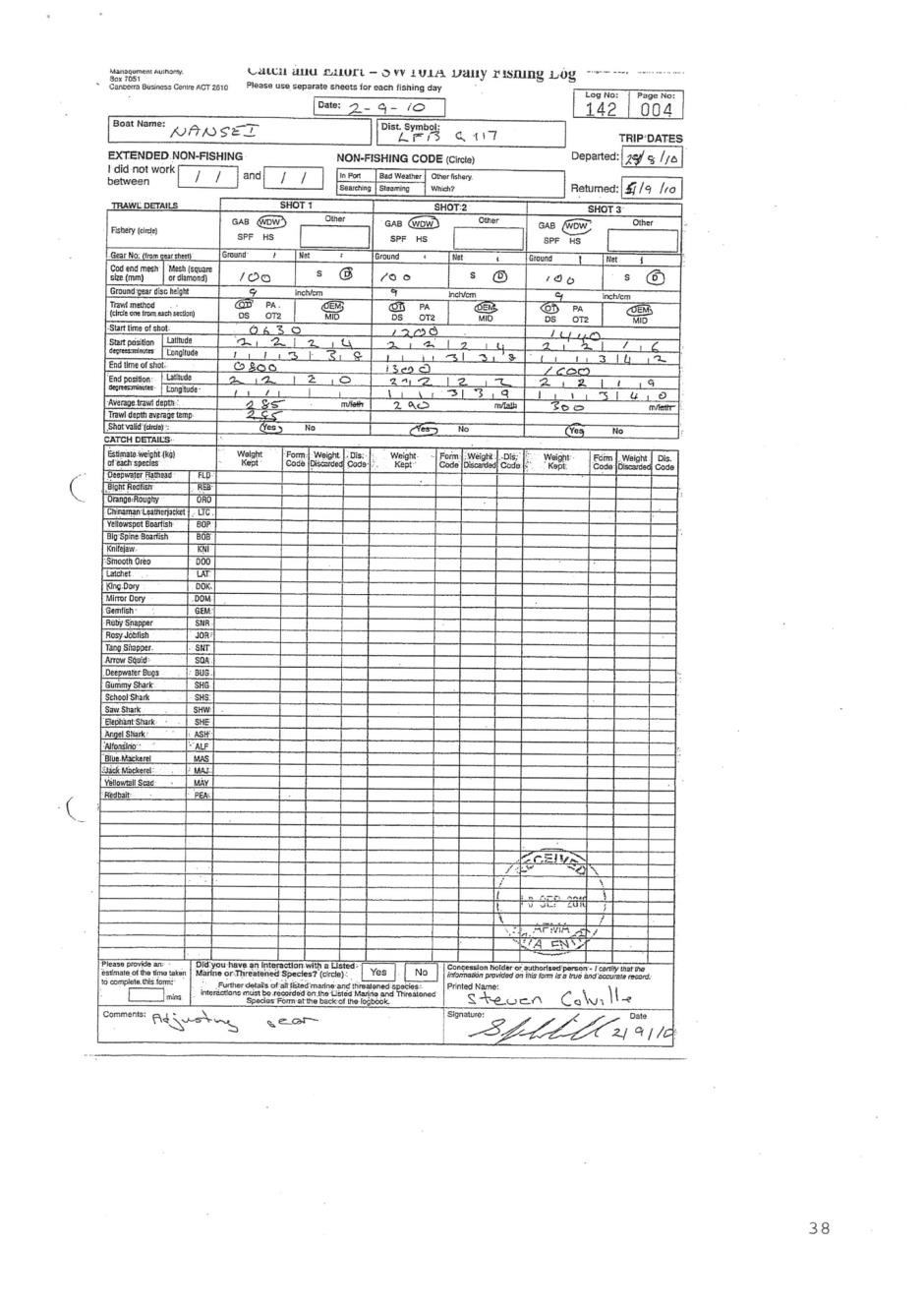

10 I have attached to these Reasons for Judgment as Attachment A the SOAF together with all exhibits referred to therein (Exhibit A). There is one typographical error in the SOAF. At par 44 of that document, the date “2 September 2012” should be “2 September 2010”.

11 There was also tendered at the hearing on behalf of Lucky S an unsigned and unverified Financial Report in respect of Lucky S for the year ended 30 June 2013 (Exhibit 1) and two character references in respect of Mr Semi Skoljarev, who is a director of Lucky S and the person who has primary responsibility for the day to day business activities of Lucky S. The two character references became Exhibits 2 and 3 respectively. Although Counsel for the Minister did not object to the tender of Exhibits 1, 2 and 3, he nonetheless submitted that the Court should pay no regard to them. In particular, he submitted that I should not use the contents of Exhibit 1 to undercut the effect of the SOAF. I accept that I cannot do that. He also submitted that character references for Mr Skoljarev were irrelevant as the entity against whom the proceeding had relevantly been brought was Lucky S, not Mr Skoljarev personally. That submission is also correct as far as it goes. However, I think that the character references flesh out and underpin to some extent the agreed fact that the contravention admitted by Lucky S was inadvertent.

12 In light of the above circumstances, at the conclusion of the hearing, the only issues which remained for me to determine were:

(a) The quantum of the pecuniary penalty to be imposed upon Lucky S; and

(b) The question of costs.

13 Lucky S did not dispute that a declaration in the form sought by the Minister should be made against it.

14 After the hearing had concluded, the Minister and Lucky S agreed on costs. They agreed that Lucky S should pay the Minister’s costs of the proceeding fixed as a lump sum pursuant to r 40.02(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 in the amount of $45,000. Accordingly, the only issue of substance remaining to be dealt with now is the quantum of the pecuniary penalty to be imposed upon Lucky S.

a Brief Synopsis of the Relevant Facts

15 I have noted at [10] above, that a complete copy of the SOAF together with all exhibits referred to therein, is Attachment A to these Reasons for Judgment. For that reason, it is not necessary to traverse the contents of the SOAF in great detail. I will, however, set out as briefly as I can some matters of fact which I consider to be significant.

16 By the time of the contraventions (2 September 2010), Mr Colville was a very experienced commercial fisherman. He was also an experienced skipper.

17 By that time, Lucky S was also a commercial fishing operation of long standing. It had focussed its attention for the most part on trawl operations in the Great Australian Bight Trawl Fishery.

18 In 1995, Lucky S acquired two Fishing Permits which allowed it to fish for Southern Bluefin Tuna in a fishery called the Western Deepwater Trawl Fishery (WDTF). At the time that it acquired those permits, Lucky S took the view that the acquisition of those permits might protect it from the introduction of a fishing quota for the WDTF. Lucky S has hardly ever operated the WDTF permits itself.

19 In about 2008, Lucky S endeavoured to sell its permits in the WDTF but was unable to secure a purchaser at that time.

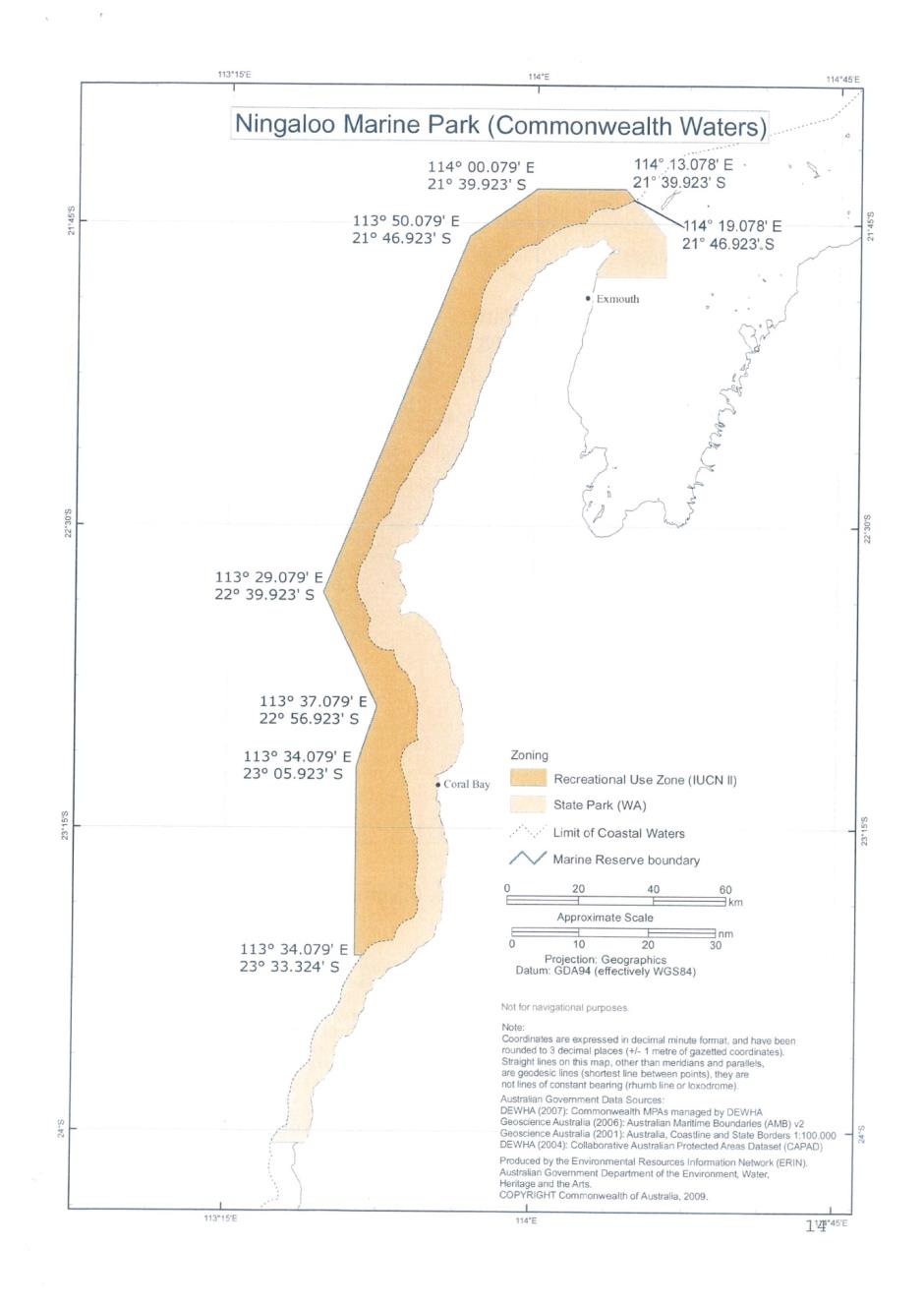

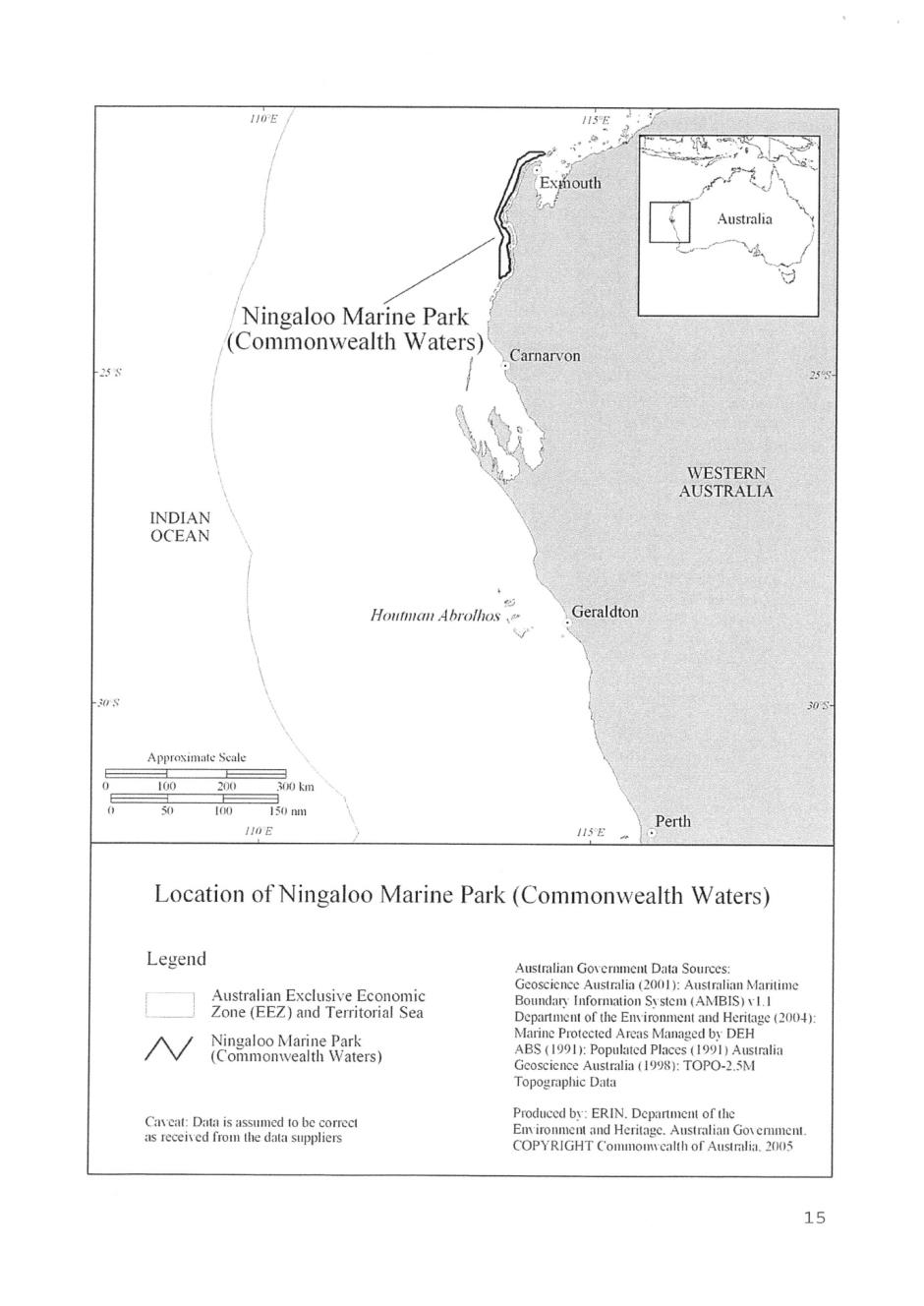

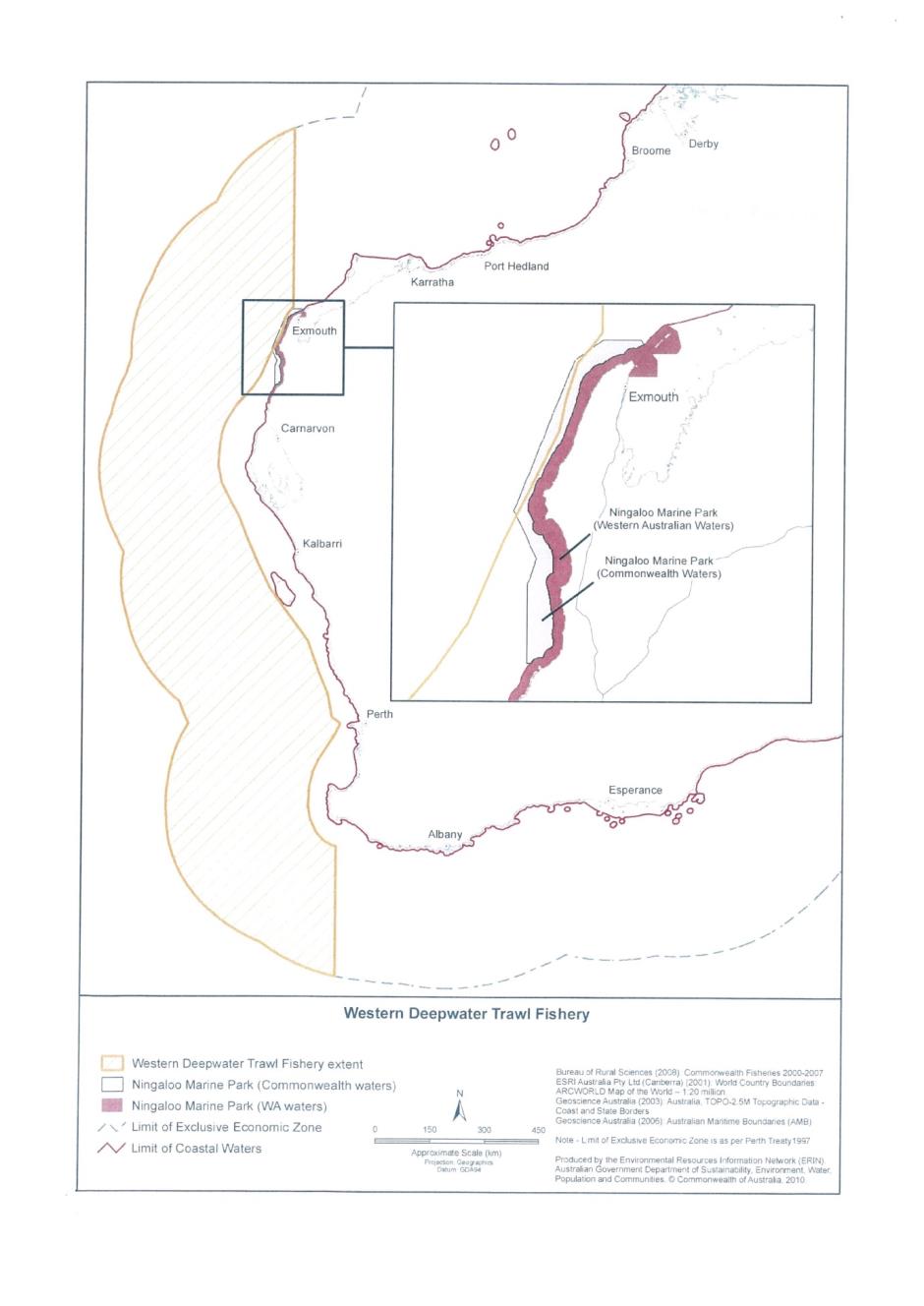

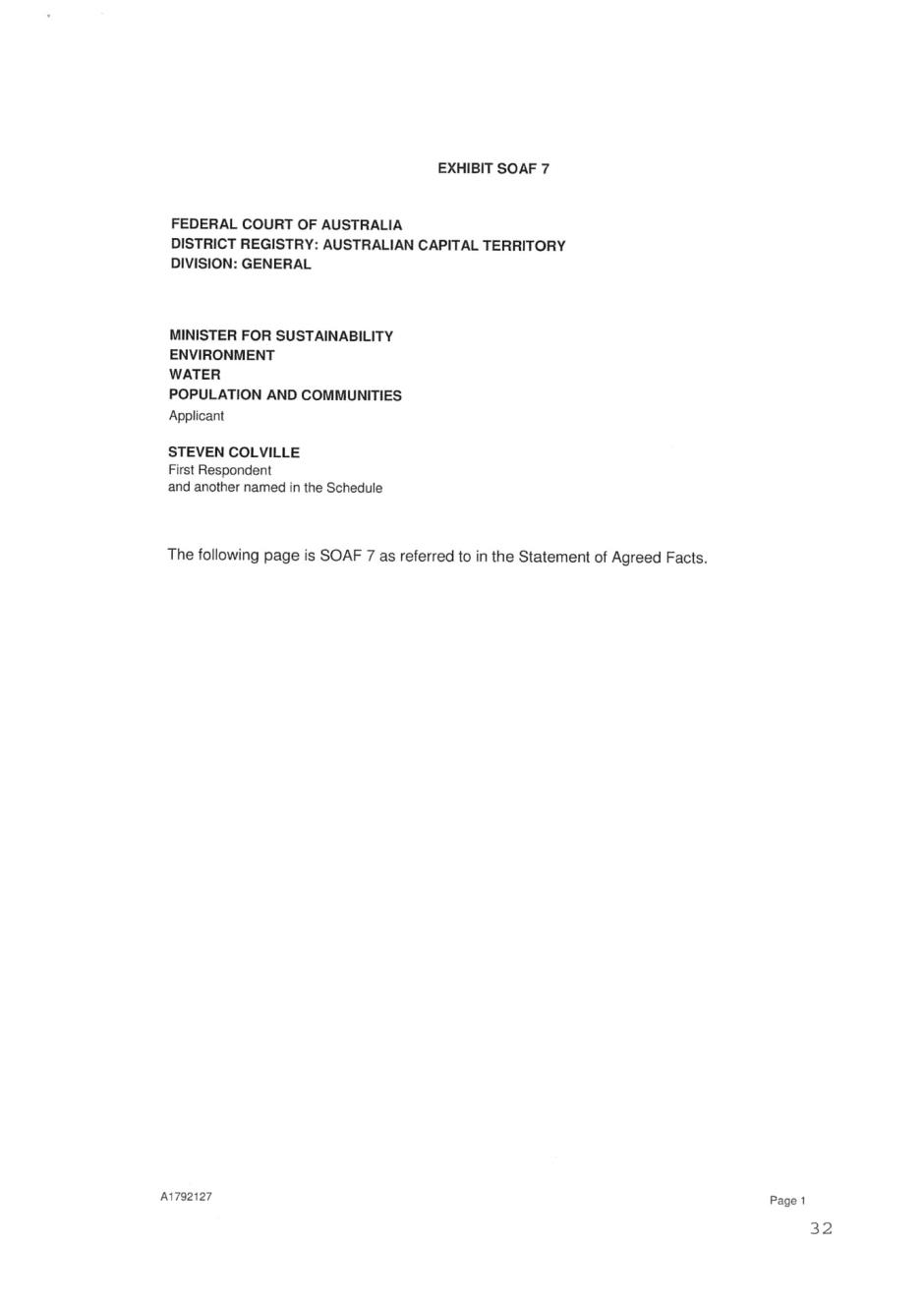

20 The Ningaloo Marine Reserve is a Commonwealth marine reserve which has been added to the World Heritage List. That Reserve is located off the coast of Western Australia approximately between Exmouth and Carnarvon. Its precise location is indicated in the maps comprising Exhibit 1 to the SOAF.

21 Commercial fishing activities have long been prohibited in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve. The special features of that Reserve which warrant such protection are set out in some detail at pars 18–26 of the SOAF.

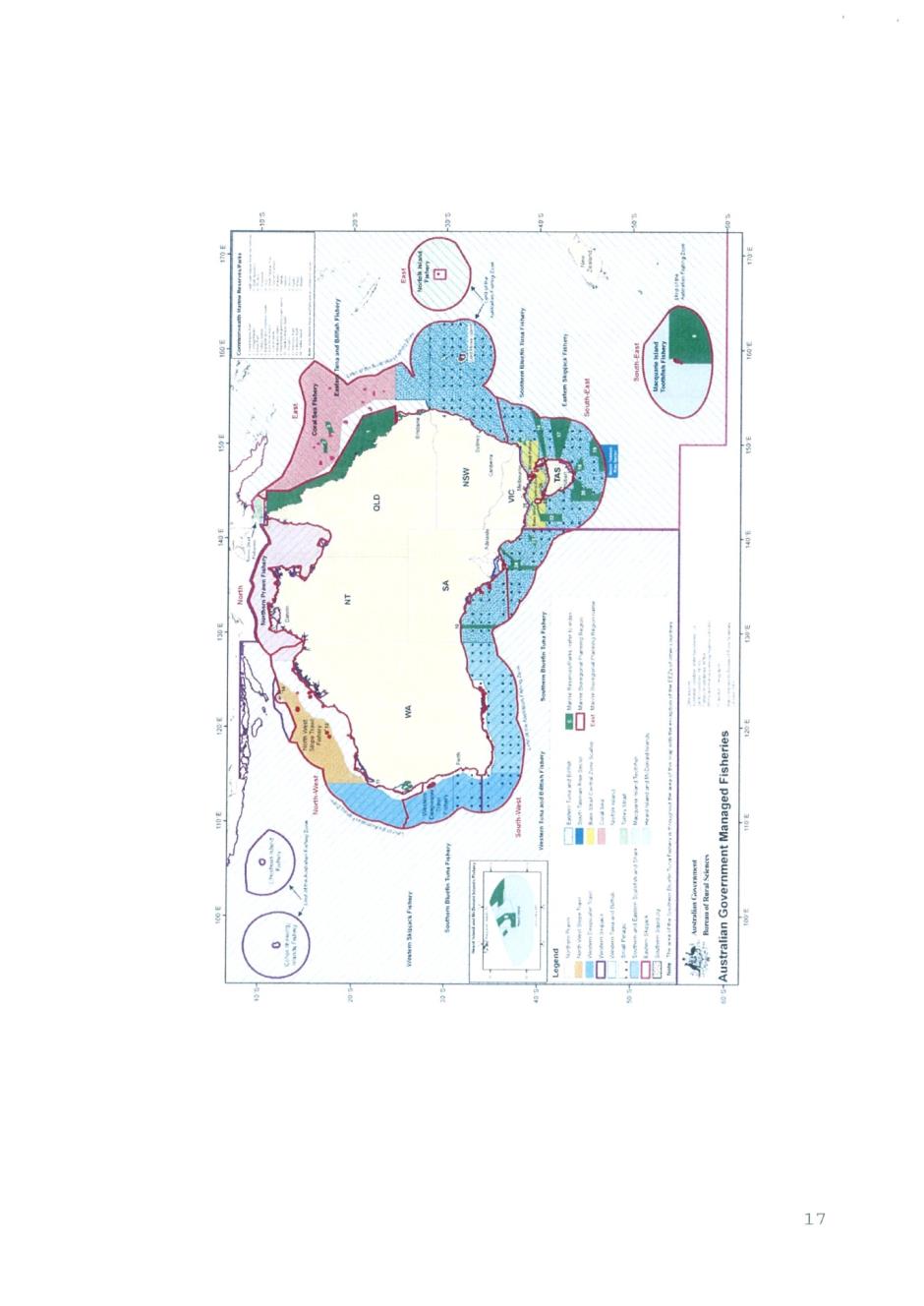

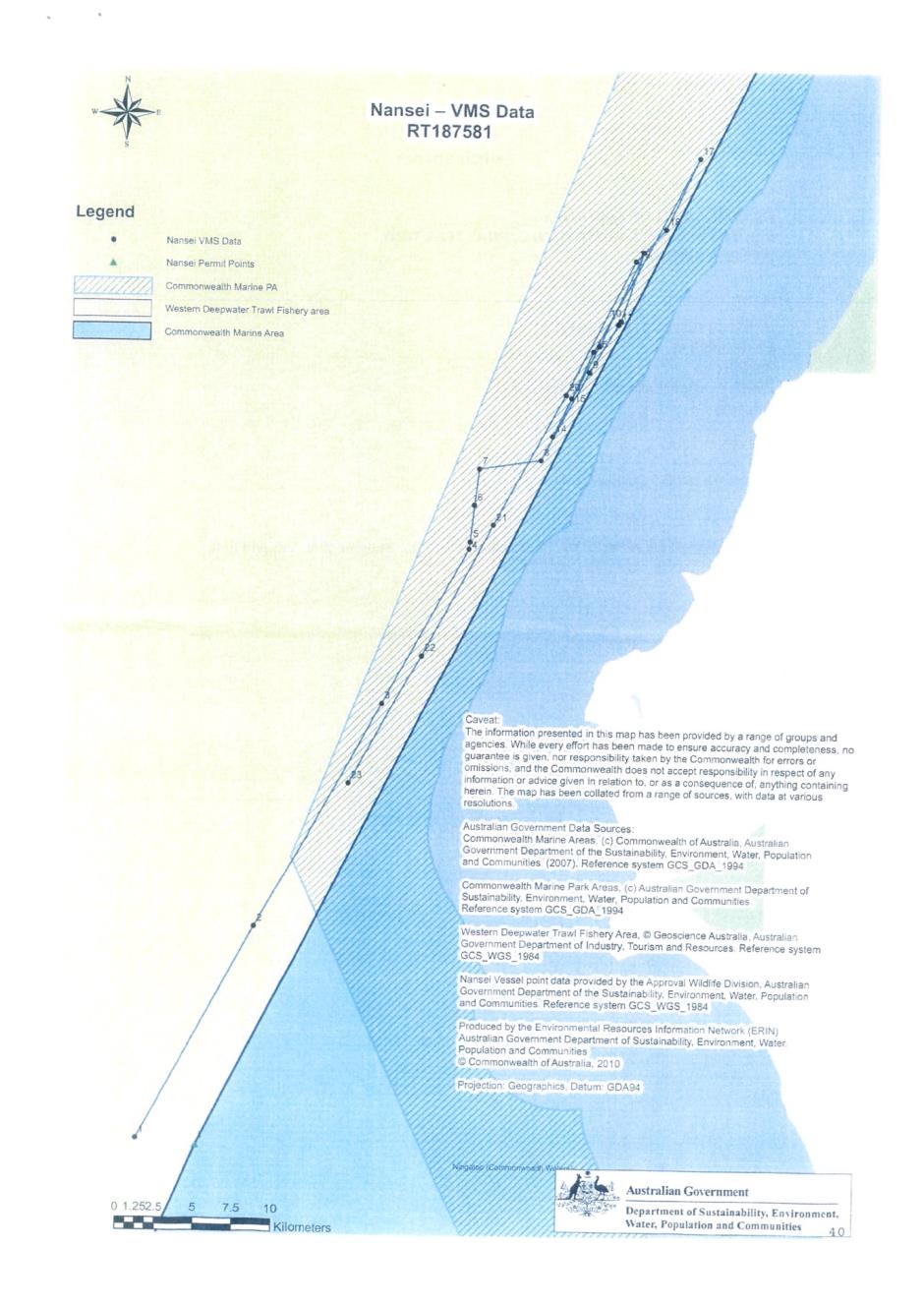

22 The WDTF is a Commonwealth fishery located off the coast of Western Australia. Its precise location is indicated in the map which is Exhibit 2 to the SOAF. That map also shows the location of other Commonwealth fisheries.

23 To a large extent, the WDTF is south of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve although there is some overlap between the Ningaloo Marine Reserve and the WDTF. The area of that overlap is relatively small.

24 Commercial fishing in Commonwealth waters is regulated through the use of designated fisheries which describe the types and locations of various fishing activities. In order to ensure efficient management and ecologically sustainable use of fishing resources, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) controls and limits commercial fishing in Commonwealth fisheries through a permit system. Permits granted by AFMA limit the number of vessels able to be used to conduct fishing activities in each fishery and make those activities subject to various conditions.

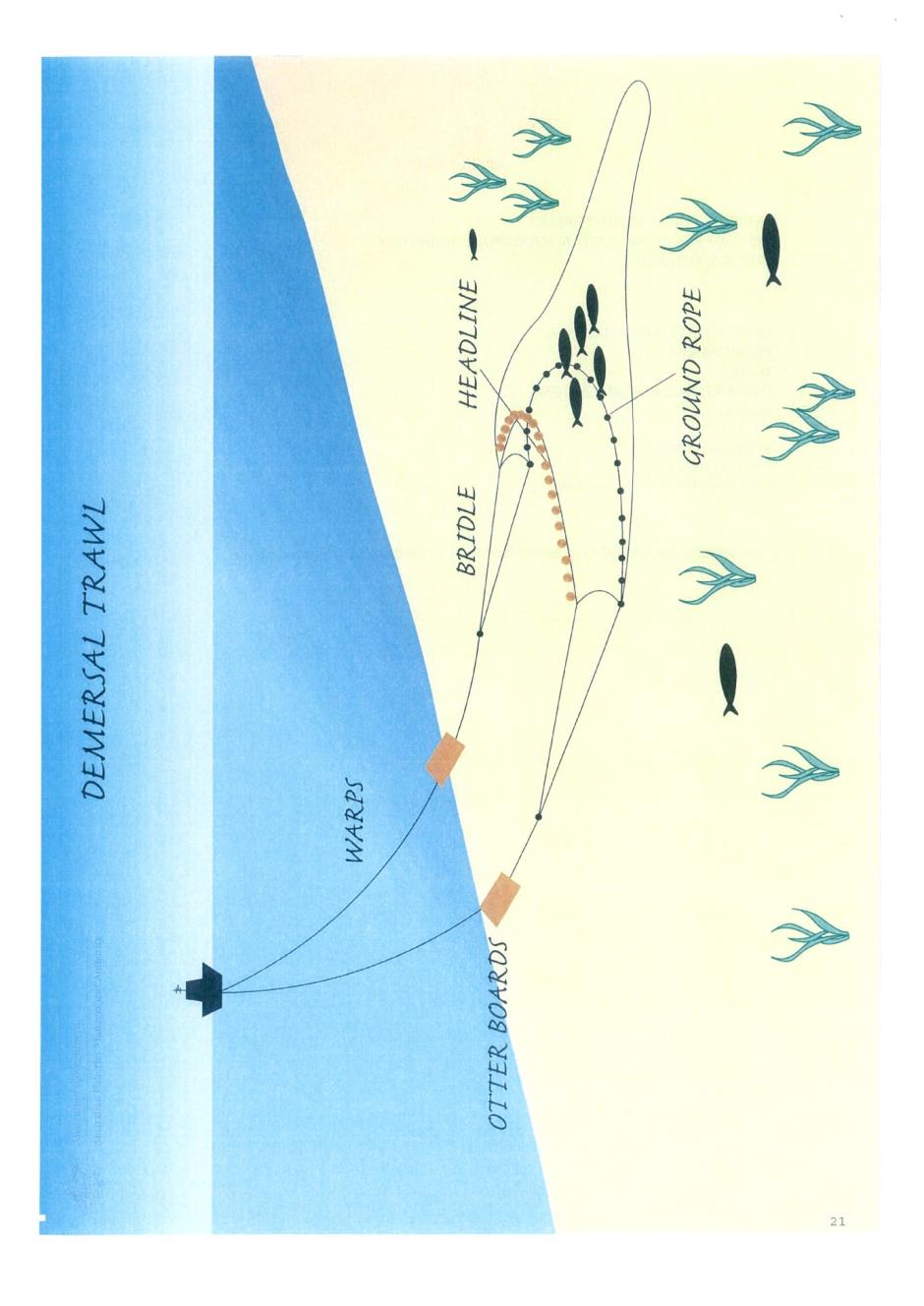

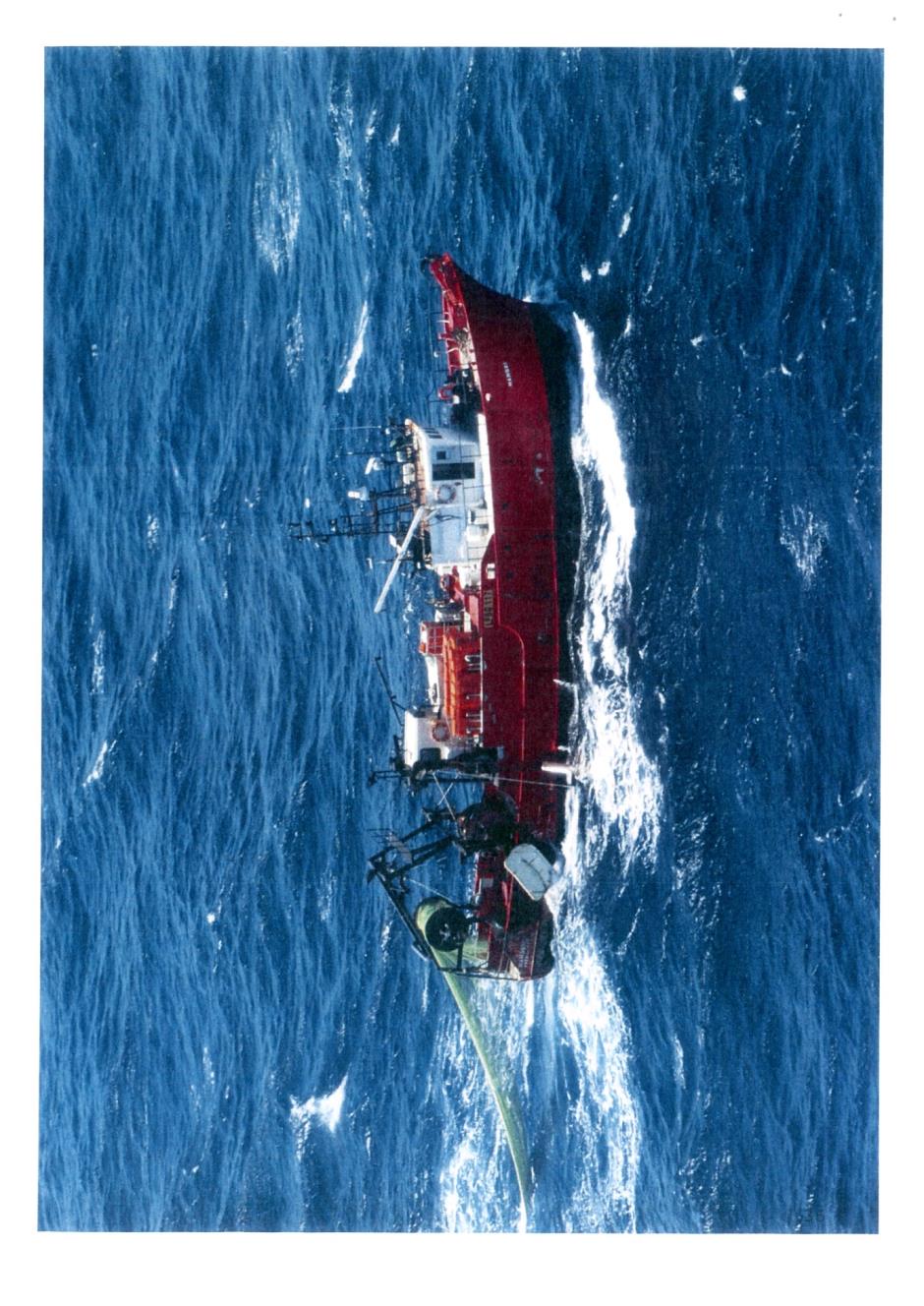

25 AFMA has controlled entry into the WDTF by issuing a total of only 11 permits. It has also imposed conditions upon the fishing activities which are allowed in the WDTF pursuant to those permits. One commercial fishing method authorised in the WDTF is known as “demersal trawling”. Demersal trawling is used to catch fish or crustaceans that live on the bottom of the ocean. It involves the net being trawled just above the sea floor. This may be contrasted with midwater trawling in which the net is pulled through the waters midway between the ocean floor and the surface. A basic illustration of a demersal trawl is included in the SOAF as Exhibit 4.

26 In about 2007, Lucky S entered into an arrangement with Morning Star Fisheries Pty Ltd (MSF) pursuant to which MSF was permitted by Lucky S to operate one of the WDTF permits which Lucky S held in order to see if MSF could develop a viable fishing operation in the WDTF. The idea was that, should matters develop as hoped, MSF might purchase the WDTF permits from Lucky S. At the time, MSF owned and operated Australian Fishing Vessel “Nansei” which was skippered by Mr Colville. MSF generally focussed its fishing operations in the southern waters of the WDTF near Perth.

27 On 17 December 2008, another fishing permit for the WDTF was issued to Lucky S under the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth) (the relevant permit). That permit authorised Lucky S to conduct commercial fishing by trawling in the WDTF using the Nansei.

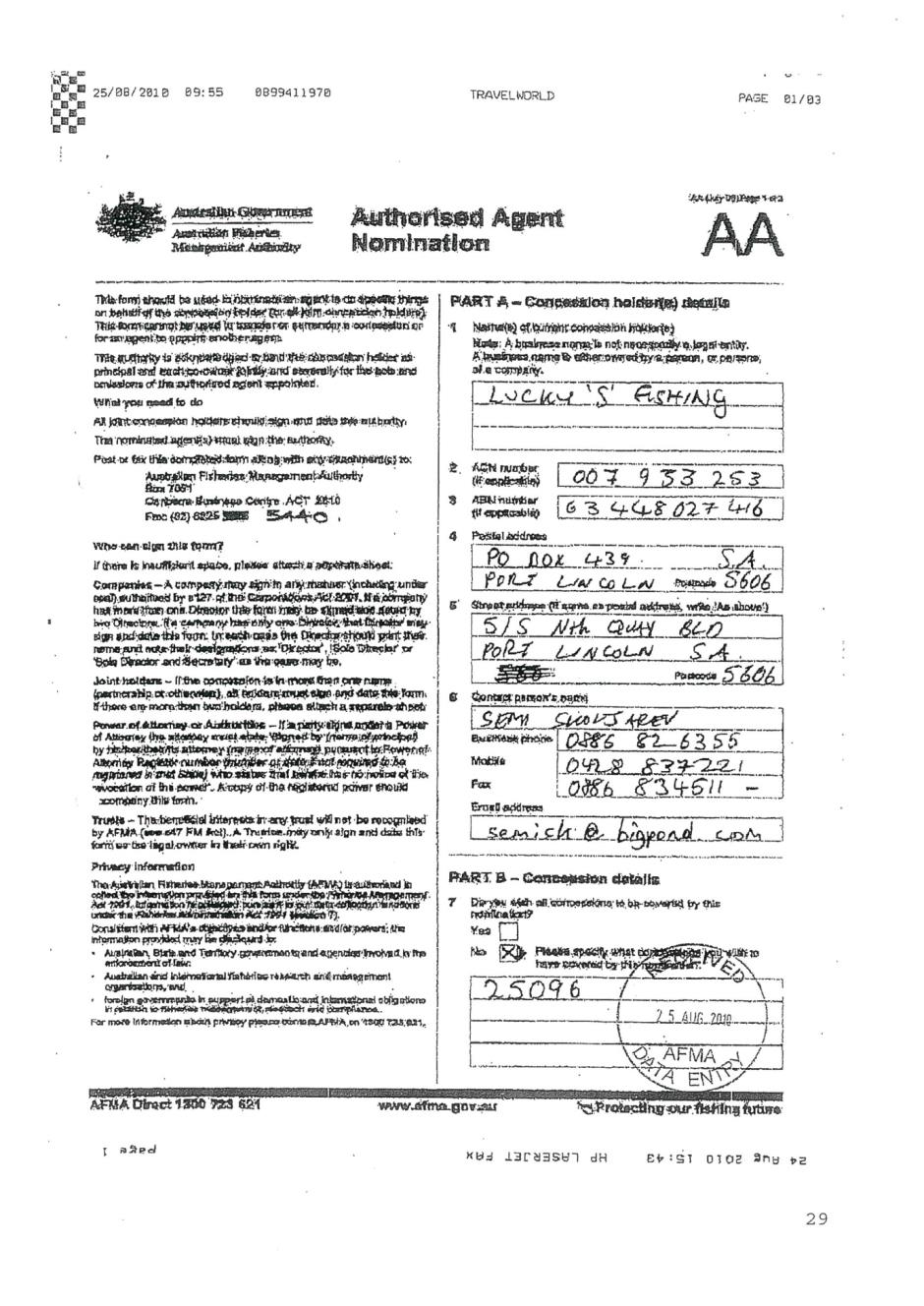

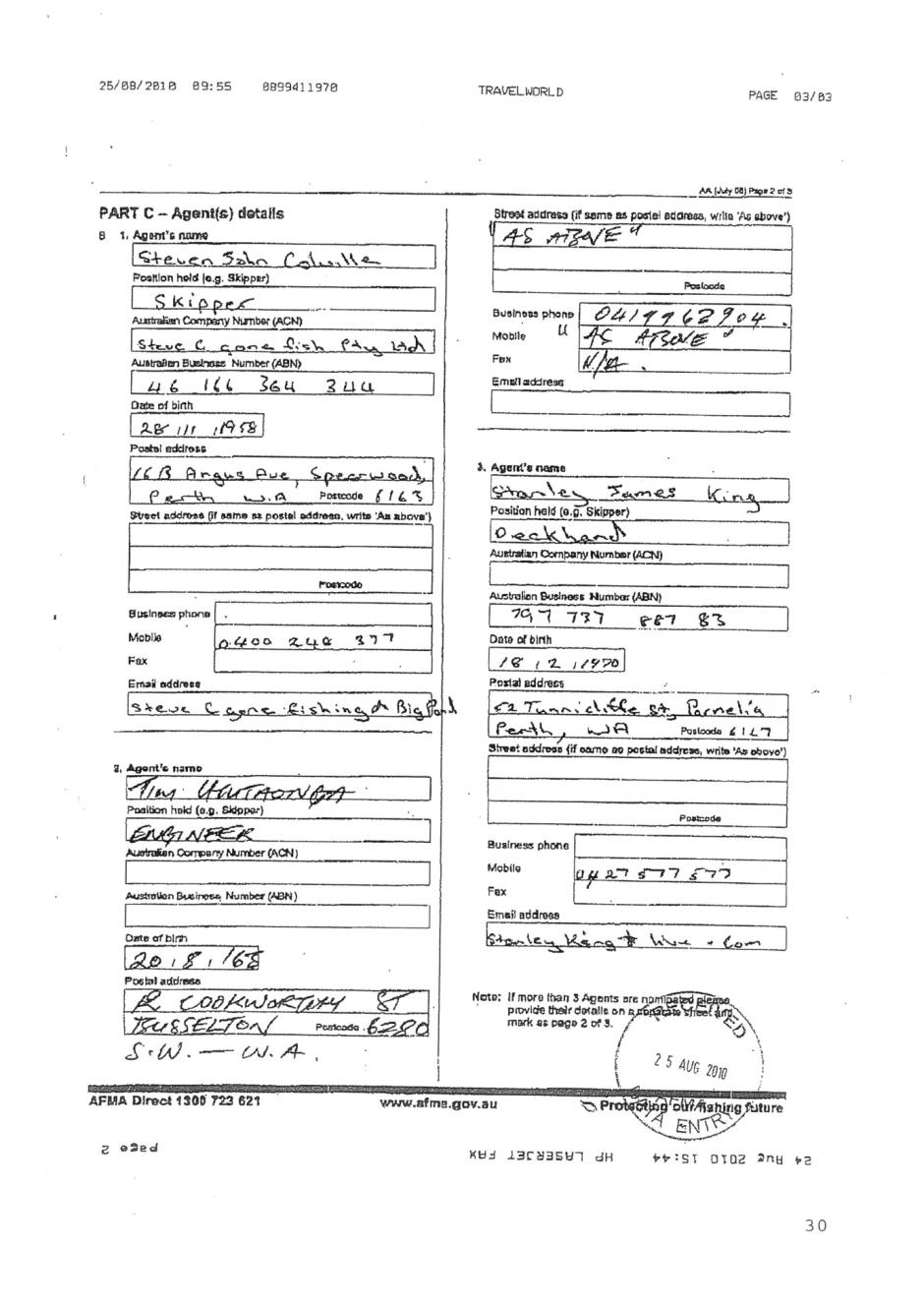

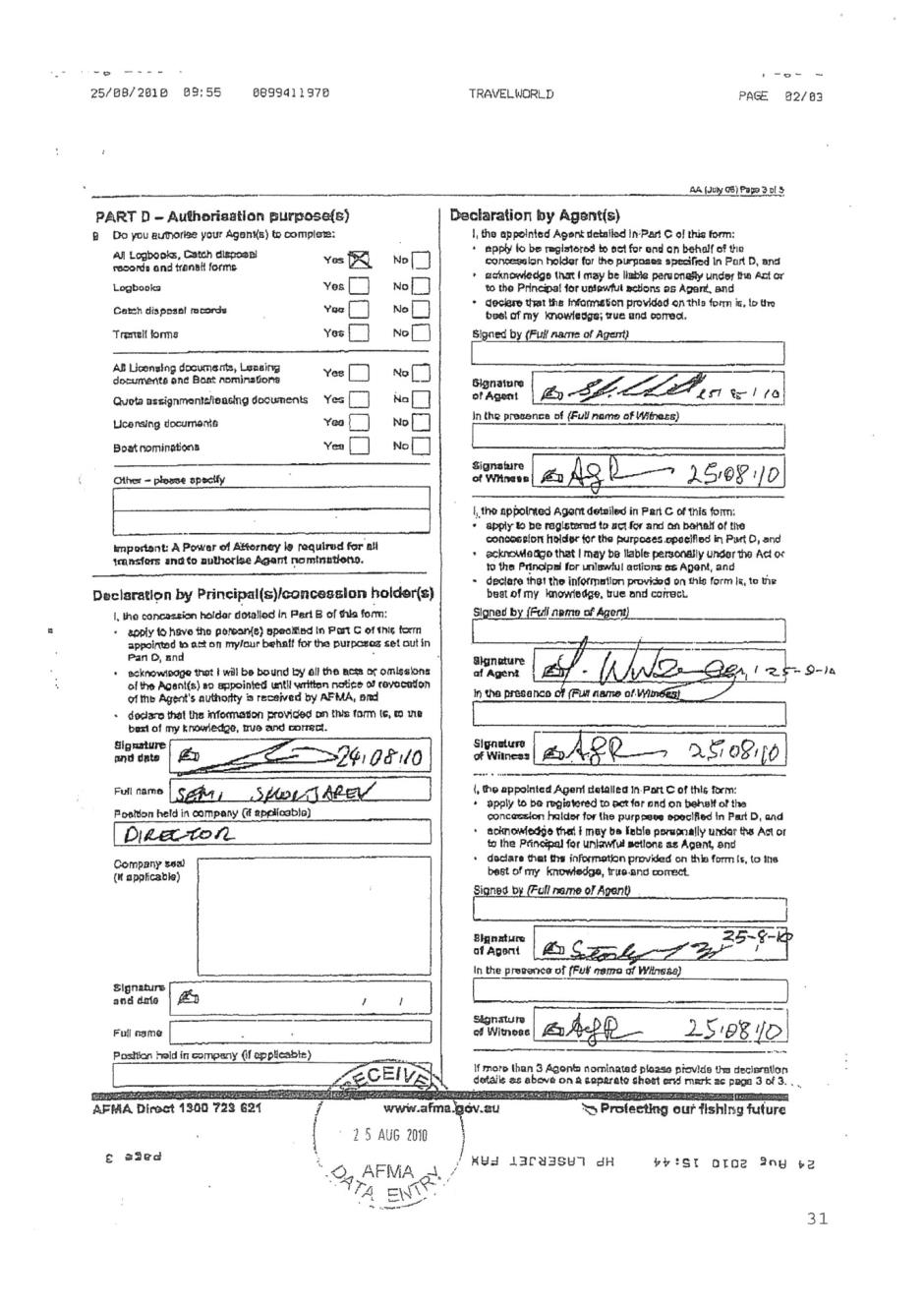

28 In the period between April and June 2010, Mr Colville was hoping to purchase the Nansei from MSF. In those circumstances, he entered into a business arrangement with Lucky S which mirrored that which MSF had entered into with Lucky S for the exploitation of the relevant permit. In order to facilitate this arrangement, Mr Colville was nominated on the permit as the agent of Lucky S. Ultimately, Mr Colville was unable to develop a sustainable fishing operation within the WDTF and consequently went bankrupt.

29 By August 2010, Mr Colville had entered into negotiations with Mr Skoljarev to purchase the relevant permit. Because Mr Colville wanted to start fishing in the WDTF immediately, he and Mr Skoljarev agreed that Mr Colville could fish under the relevant permit as an agent of Lucky S pending the finalisation of all relevant contractual arrangements.

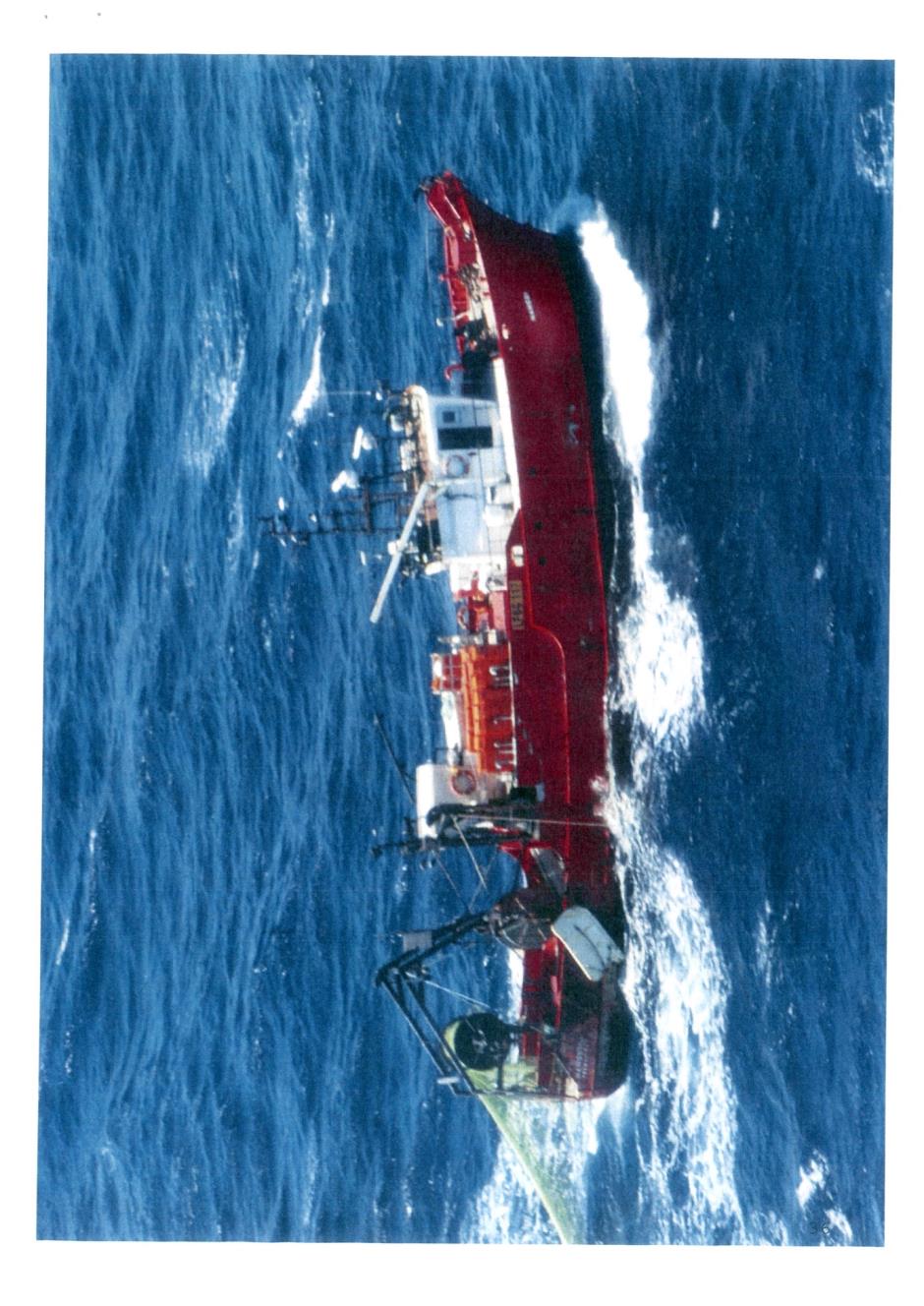

30 On 29 August 2010, Mr Colville took the Nansei out to sea to undertake commercial fishing in the WDTF. Mr Colville was the skipper of the Nansei and was in charge of the crew.

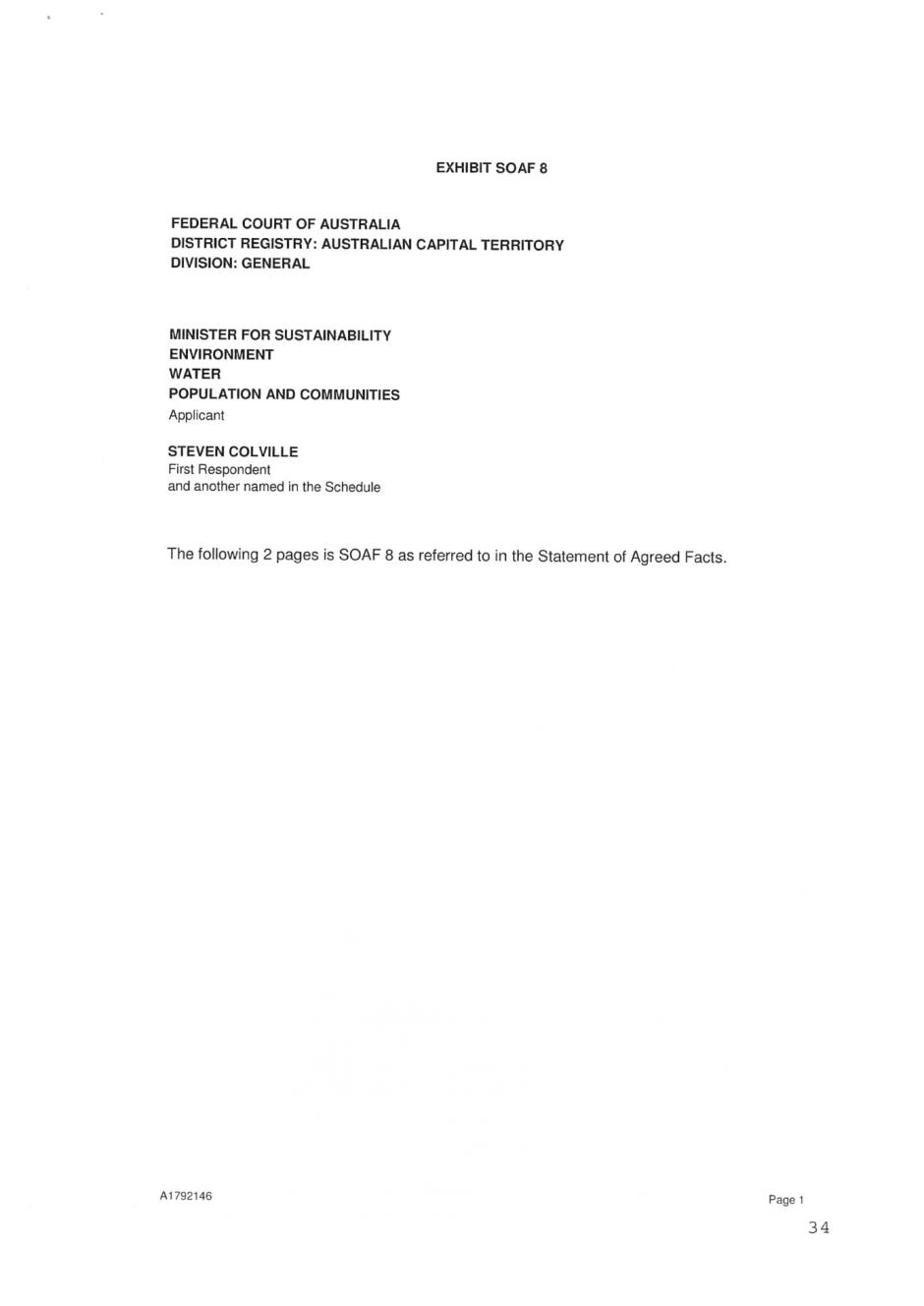

31 On 2 September 2010, the Nansei entered that part of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve which overlaps with the WDTF. During the time that the Nansei was within the Reserve, it was used to conduct commercial demersal trawling activities. Those activities were undertaken by Mr Colville with the assistance of his crew. The details of those activities are set out at pars 41–45 of the SOAF.

32 Those activities were identified by AFMA pursuant to its Vessel Monitoring System (VMS). At all relevant times the Nansei’s VMS was activated.

33 At pars 48–55 of the SOAF, the parties have set out in some detail the general harms to the Ningaloo Marine Reserve caused by commercial trawling and the harms likely to have been caused by Mr Colville’s fishing activities on 2 September 2010. It is not necessary to traverse that material in detail. However, I pause to note that, as has been agreed between the parties, commercial trawling has the potential for significant adverse impacts on the marine life of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve. This is particularly so when the trawling undertaken is demersal trawling.

34 Mr Colville was not aware that the Nansei had entered the Ningaloo Marine Reserve nor was he aware that he was undertaking commercial fishing activities in an area in which such activities were forbidden. He did not appreciate that there was an area of overlap between the WDTF and the Ningaloo Marine Reserve. Mr Colville believed that he could legally conduct commercial fishing activities within the WDTF as long as he stayed within the boundaries of the relevant permit. As is apparent from the summary which I have given, he did stay within those boundaries at all relevant times.

35 Mr Colville acknowledged that he ought to have taken steps prior to undertaking his fishing activities on 2 September 2010 in order to check and plot the boundaries of the WDTF in and around the areas in which he intended to conduct those fishing activities so as to ensure that he was conducting those activities lawfully. Although his fishing activities were undertaken for commercial purposes, namely to catch fish for sale at a profit, on the occasion in question, Mr Colville did not in fact make any profits from the contravening conduct. He caught only a very small quantity of fish and the operating costs of the trip far outweighed any sales from the fish caught.

36 It is clear that the contravention by Mr Colville was inadvertent.

37 In addition, despite his long history as a commercial fisherman, Mr Colville had not previously been found by the Court to have contravened the EPBC Act.

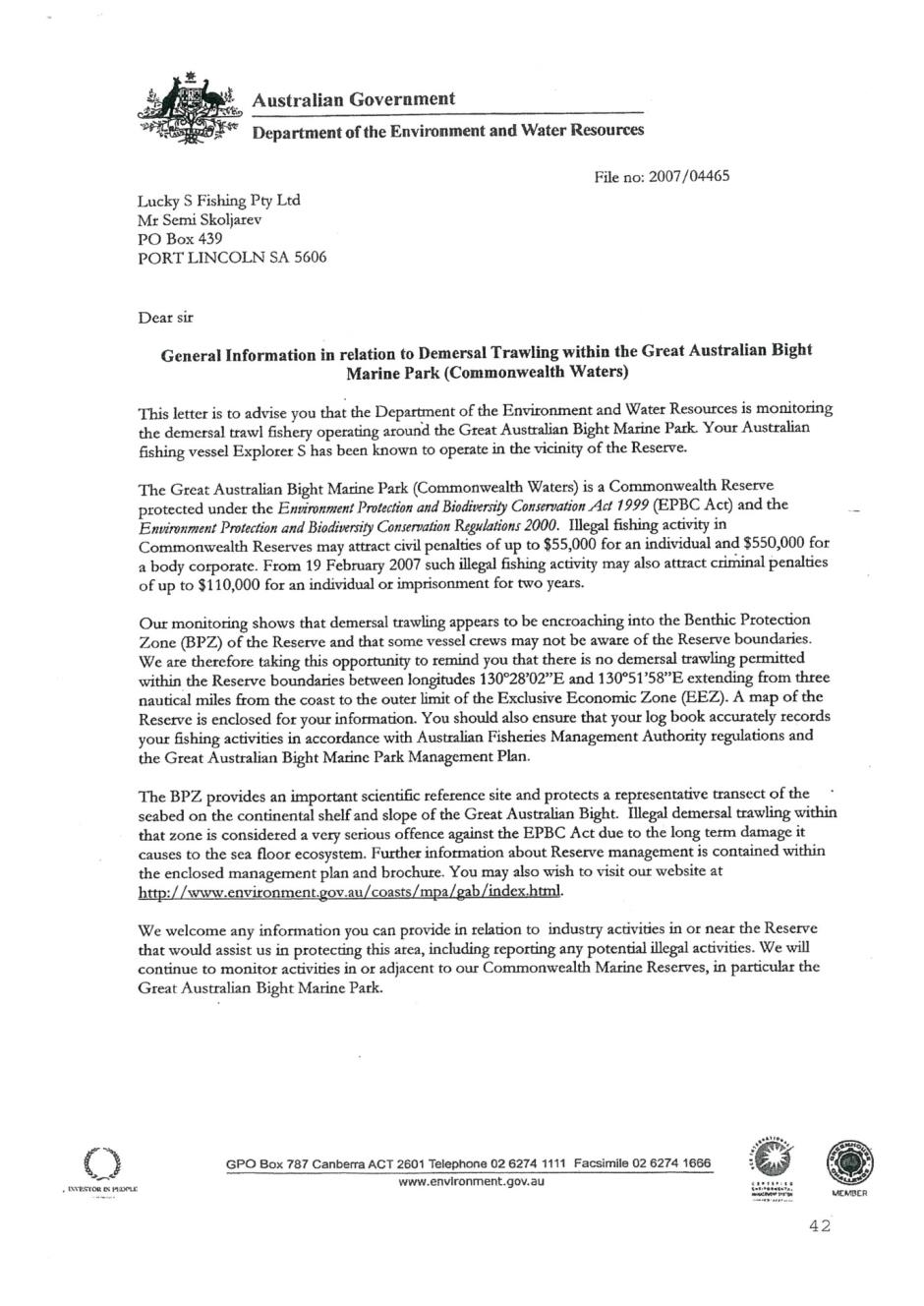

38 Mr Skoljarev was aware that Commonwealth marine parks could overlap with Commonwealth fisheries. In 2007, he had received two letters from the Department which explained the operation of the prohibitions in Commonwealth marine reserves and the potential for environmental damage through demersal trawling. Despite that correspondence, Mr Skoljarev had not checked, and was not aware, that the Ningaloo Marine Reserve in fact overlapped with the WDTF.

39 Beyond ensuring that Mr Colville had a copy of the relevant permit, Lucky S did not take any steps to ensure that Mr Colville would not fish in a Commonwealth marine reserve or otherwise contravene the EPBC Act. In particular, it did not draw to Mr Colville’s attention the circumstance that there was a small overlap between the Ningaloo Marine Reserve and the WDTF. Lucky S left the conduct of the commercial trawling in the WDTF under the relevant permit entirely to Mr Colville.

40 As was the case with Mr Colville, Lucky S did not derive any financial benefit from the contravening conduct.

Consideration

41 Under s 354(1)(f) of the EPBC Act, a person must not take an action for commercial purposes in a Commonwealth reserve except in accordance with a management plan in operation for that reserve. As at 2 September 2010 when the contraventions by Mr Colville and Lucky S took place, there was no management plan in operation for the Ningaloo Marine Reserve.

42 Commercial fishing is “an action for commercial purposes” within the meaning of s 354(1).

43 Section 481 of the EPBC Act is in the following terms:

481 Federal Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty for contravening civil penalty provision

Application for order

(1) Within 6 years of a person (the wrongdoer) contravening a civil penalty provision, the Minister may apply on behalf of the Commonwealth to the Federal Court for an order that the wrongdoer pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

Court may order wrongdoer to pay pecuniary penalty

(2) If the Court is satisfied that the wrongdoer has contravened a civil penalty provision, the Court may order the wrongdoer to pay to the Commonwealth for each contravention the pecuniary penalty that the Court determines is appropriate (but not more than the relevant amount specified for the provision).

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(3) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Act to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Conduct contravening more than one civil penalty provision

(4) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Act against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of those provisions. However, the person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

44 In s 481(3)(a) to (d), the legislature has specified four matters which are required to be taken into account by the Court in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty as part of the concept of “… all relevant matters”.

45 In the present case, particular attention needs to be given to the matters referred to in subs (3)(a) and subs (3)(c) of s 481.

46 As far as subs (3)(d) is concerned, neither Mr Colville nor Lucky S has previously been found by the Court in a proceeding under the EPBC Act to have engaged in any conduct similar to the contravening conduct identified in the present case.

47 As far as the subject matter of subs (3)(b) is concerned, it is extremely difficult to come to any firm view as to the likely damage caused by Mr Colville’s conduct. Nonetheless, it is quite likely that some damage was done to the sea floor in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve by the demersal trawling activities of Mr Colville. The agreement between the parties in this regard is to be found at pars 53–55 of the SOAF.

48 At the time of the contraventions the subject of the present proceeding, the maximum civil penalty for a contravention of s 354(1)(f) of the EPBC Act was $55,000 for an individual and $550,000 for a body corporate.

49 Section 354A of the EPBC creates certain cognate criminal offences and provides for severe maximum penalties for those offences.

50 These circumstances (among others) indicate that the protection of the environment is considered by the legislature to be a matter of high importance.

51 Section 498B(1) of the EPBC Act provides:

498B Conduct of directors, employees and agents

Bodies corporate—conduct

(1) Any conduct engaged in on behalf of a body corporate:

(a) by a director, employee or agent of the body corporate within the scope of his or her actual or apparent authority; or

(b) by any other person at the direction or with the consent or agreement (whether express or implied) of a director, employee or agent of the body corporate, where the giving of the direction, consent or agreement is within the scope of the actual or apparent authority of the director, employee or agent;

is to be taken, for the purposes of this Act, to have been engaged in also by the body corporate unless the body corporate establishes that the body corporate took reasonable precautions and exercised due diligence to avoid the conduct.

52 For the purposes of this proceeding, the parties agreed that Mr Colville was the agent of Lucky S within the meaning of that term in s 498B(1)(a) and that Mr Colville’s contravening conduct on 2 September 2010 occurred within the scope of his actual or apparent authority.

53 At 298–300 [40]–[50] of Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities v Woodley (2012) 194 LGERA 290 (Woodley), I set out the matters which I considered pertinent to the imposition of a penalty upon Mr Woodley in that case and also my understanding of the relevant principles. In those paragraphs, I said:

40. At [31] (p 372) in Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357, Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ said:

31. It follows that careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick. That having been said, in our opinion, it will rarely be, and was not appropriate for Hulme J here to look first to a maximum penalty (The maximum selected by his Honour was not, as will appear, the maximum available in respect of the principal offence) and to proceed by making a proportional deduction from it. That was to use a prescribed maximum erroneously, as neither a yardstick, nor as a basis for comparison of this case with the worst possible case.

41 In this Court, these remarks by the High Court in Markarian have been held to apply to the imposition of civil penalties (see Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith (2008) 165 FCR 560 at [108] (p 584) and Secretary, Department of Health and Ageing v Export Corp (Australia) Pty Ltd (2012) 288 ALR 702 at [49]–[50] (p 714) and at [67] (p 718)).

42 The penalties sought by the Minister in the present case are towards the low end of the available range set by the legislature (18%–27% of the maximum for Mr Woodley and 9%–13% of the maximum for Venture).

43 In his Defence, Mr Woodley submitted that the contravention was not intentional, that he and Venture both had unblemished records in respect of environmental matters, that he had co-operated with the authorities in the conduct of the litigation, that he was truly sorry for what he had done and that he had “… learnt his lesson …”. To this list of factors which count in favour of Mr Woodley and Venture must be added the following additional matters, namely:

(a) Both respondents admitted the contraventions in full. That conduct led to the production of the Agreed Statement of Facts. This co-operation on the part of Mr Woodley and Venture saved the Minister a great deal of time, effort and expense. It has also meant that there has been a considerable saving of the Court’s time.

(b) There was only one contravention. It appears to have been a “one-off” event.

(c) No lobsters were actually caught by Mr Woodley in the Sanctuary Zone or in the Reserve on the occasion in question.

(d) Both Mr Woodley and Venture are experiencing financial difficulties at the present time. The precise detail of those difficulties was not the subject of evidence beyond the documents attached to the second Defence referred to at [27] above.

44 The matters listed at [43] above were identified by Counsel for the Minister as being relevant in determining penalty and in favour of Mr Woodley and Venture. Those matters were accepted by him as being relevant to the determination of penalty.

45 In determining the appropriate penalties in this case, I intend to take into account all of the matters listed at [43] above in favour of Mr Woodley and Venture.

46 Counsel for the Minister submitted that, in addition to the four matters specified in s 481(3) of the EPBC Act, the Court has held on previous occasions that, in matters such as those with which I am presently dealing, it is appropriate to have regard to:

(a) The contravenor’s co-operation during investigations and subsequent Court proceedings;

(b) Any relevant prior “record” on the part of the contravening party;

(c) The contravenor’s business arrangements and financial circumstances; and

(d) Any remorse or contrition shown by the contravenor.

47 Counsel for the Minister emphasised that the principal object of civil penalty provisions is to ensure deterrence. In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076, which was a case dealing with s 76 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), French J said (at p 52,152):

The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

48 It was submitted on behalf of the Minister that the dictum of French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd has been applied not only in the Trade Practices context but in a wide variety of other regulatory regimes. In particular, it was submitted that the need for a penalty to have a proper deterrent effect had been emphasised in the context of the EPBC Act in a number of cases (Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities v De Bono [2012] FCA 643 at [49] and [54]; Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts v PGP Developments Pty Ltd at [16]; Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts v Rocky Lamattina & Sons Pty Ltd (2009) 258 ALR 107, (2009) 167 LGERA 219 at [46]–[47]; Minister for Environment and Heritage v Warne [2007] FCA 599 at [15]–[16]; Minister for the Environment and Heritage v Wilson [2004] FCA 6 at [7]; and Minister for the Environment and Heritage v Greentree (No 3) (2004) 136 LGERA 89 at [69]–[70] and [81]).

49 Counsel for the Minister submitted that I should approach the determination of the penalties in the present case by applying the process commonly called “instinctive synthesis”. He submitted that this process was described in Markarian as having the following attributes:

(a) There must be a weighing of all relevant factors, rather than starting from some pre-determined figure and making incremental additions or subtractions for each separate factor (Markarian at [36]–[39] (pp 373–375) (per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) and at [69]–[73] (pp 385–387) (per McHugh J)); and

(b) It is critical that the reasoning process involved in synthesising the penalty be transparent (Markarian at [36]–[39] (pp 373–375) (per the plurality) and at [84] (p 390) (per McHugh J)).

50 I think that the submissions made on behalf of the Minister which I have summarised at [46]–[49] above are correct and I accept them. I shall approach the imposition of penalties in the present case with those submissions firmly in mind.

54 I made similar observations in Clean Energy Regulator v MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 at [67]–[72].

55 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG) at 659 [65], French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ said:

General and specific deterrence must play a primary role in assessing the appropriate penalty in cases of calculated contravention of legislation where commercial profit is the driver of the contravening conduct. TPG’s campaign was conducted over approximately 13 months at a cost to TPG of $8.9 million (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (No 2) (2012) ATPR ¶42-402 at 45,596 [79]–[80]). It generated revenue of approximately $59 million, and an estimated profit of $8 million (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (No 2) (2012) ATPR ¶42-402 at 45,601 [117]–[119]). TPG’s customer base grew from 9,000 to 107,000 during this period, although it cannot be said that this was at the expense of TPG’s competitors.

56 In his dissenting judgment in TPG, Gageler J (at 662 [84]) noted the importance of deterrence when a court is considering the imposition of a civil penalty.

57 In TPG at 659 [66], the plurality endorsed statements which the Full Court had made in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249 at 265 [62]–[63] in the following terms:

The pecuniary penalty fixed by the primary judge did not exceed that which might reasonably be thought appropriate to serve as a real deterrent both to TPG and to its competitors. As was said in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the penalty for contravention of the TPA((2012) 287 ALR 249 at 265 [62]–[63]):

“must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. … [T]hose engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.”

58 The observations made by the plurality in TPG should be taken as reinforcing the importance of deterrence (both specific and general) in the Court’s consideration of the imposition of civil penalties in a case such as the present. In addition, guidance is also given by the passage which I have extracted at [57] above.

59 In the present case, the Minister sought the imposition of a civil penalty upon Lucky S of an amount in the range of $40,000 to $55,000 (being approximately 7.25%–10% of the statutory maximum for a corporation). Lucky S submitted that a penalty in the range sought by the Minister was too severe and that a penalty in the range $12,500–$27,500 would be appropriate.

60 The hearing of this proceeding took place before the High Court handed down its decision in Barbaro v The Queen (2014) 305 ALR 323. For that reason, the question of the relevance of that decision to the imposition of civil penalties under the EPBC Act was not addressed by the parties. I have not sought to obtain submissions from the parties on that question in light of the High Court’s decision in Barbaro. I do not consider that there is any need, in the present case, to address that question.

61 The Minister understandably focussed his submissions in support of the penalty range advocated by him on the need for general deterrence.

62 He submitted that demersal trawling poses a very grave risk to marine life in Commonwealth marine reserves. He also submitted that there was a need for the Court to send “… a strong message to commercial fishing businesses…” to take appropriate steps proactively in order to ensure that they do not undertake unauthorised fishing in Commonwealth marine reserves. Counsel for the Minister emphasised that the harm caused by carelessness, negligence or recklessness was just as serious as the harm caused by conscious abuse of the reserves. It was submitted that the Court should make clear to commercial fishing operations that it will not be worth their while to deliberately contravene the prohibitions on fishing in Commonwealth marine reserves.

63 It was further submitted on behalf of the Minister that the conduct on the part of Lucky S was serious although it was not the actual actor in the prohibited commercial fishing. The key feature which led to the contravention on the part of Lucky S was its failure to take any steps at all to ensure that Mr Colville did not undertake any commercial fishing activity in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve. There was no discussion between Mr Skoljarev and Mr Colville in which Mr Skoljarev drew Mr Colville’s attention to the fact that there was an area of overlap between the Ningaloo Marine Reserve and the WDTF and no discussion between those men which involved any detailed consideration of the relevant maps in order to ensure that the prohibition on fishing in the Ningaloo Marine Reserve was strictly honoured. As Counsel submitted, it would have been relatively easy for Mr Skoljarev to double check the location of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve and the boundaries of the WDTF and to have had an appropriate formal discussion with Mr Colville about the need to respect the prohibition on fishing in the Reserve. Had such steps been taken, both men would have known that there was a small area of overlap between the Reserve and the WDTF and that care needed to be taken to avoid undertaking any commercial fishing activities within the Reserve.

64 The Minister accepted that the need for specific deterrence in the present case was either non-existent or not great. Lucky S had fully co-operated with the relevant authorities and had conceded the alleged contraventions. Furthermore, it has fully co-operated in all relevant ways in the conduct of the present proceeding.

65 The Minister submitted that, although the conduct of Lucky S might properly be viewed as inadvertence, it was either negligent or reckless and should not have occurred.

66 In his initial Written Submissions, the advocate who appeared for Lucky S generally agreed with the submissions made on behalf of the Minister as to the significance of general deterrence in the imposition of a civil penalty for contraventions of the EPBC Act. In addition, he submitted that there is a danger in over-emphasising the need to send a strong message to other commercial fishing operations. He submitted that the overriding aim of the Court should be to impose an appropriate penalty in all the circumstances of the case. He also submitted that Lucky S has already suffered a significant amount of embarrassment as a result of what has occurred and that that embarrassment has operated as a very effective specific deterrence in the circumstances of the present case. The advocate who appeared for Lucky S also submitted that Lucky S had made very little profit from making available the relevant permit to Mr Colville and that, in more recent times, it had suffered significant financial problems.

67 Both parties addressed submissions directed to a comparison with other cases where civil penalties had been imposed upon commercial fishing operations under the EPBC Act. Notwithstanding this circumstance, the Minister quite correctly submitted that, in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 294–295, the Full Court had disapproved of that approach. In that case, the majority (Burchett and Kiefel JJ) said:

There are, of course, limits to the approach accepted in these cases. The Court should not leave room for any impression of weakness in its resolve to impose penalties sufficient to ensure the deterrence, not only of the parties actually before it, but also of others who might be tempted to think that contravention would pay, and detection lead merely to a compliance program for the future.

A hallmark of justice is equality before the law, and, other things being equal, corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties: Trade Practices Commission v Axive Pty Ltd (at 42,795). There should not be such an inequality as would suggest that the treatment meted out has not been even-handed: cf the criminal law case Lowe v The Queen (1984) 154 CLR 606. However, other things are rarely equal where contraventions of the Trade Practices Act are concerned. In the present case, differing circumstances, size, market power and responsibility for the contraventions, as well as other factors, complicate any attempt to compare the penalties imposed on the appellant with those imposed on the other corporations.

Another form of comparison is not appropriate. The facts of the instant case should not be compared with a particular reported case in order to derive therefrom the amount of the penalty to be fixed. Cases are authorities for matters of principle; but the penalty found to be appropriate, as a matter of fact, in the circumstances of one case cannot dictate the appropriate penalty in the different circumstances of another case. The point was well made by Spender J in Trade Practices Commission v Annand and Thompson Pty Ltd (at 48,394) when he said:

“Each case must, of course, be viewed on its own facts and facts may be infinite in their variety.”

It follows, as his Honour also said, that “[t]he quantum of penalties imposed in other cases can seldom be of very much direct assistance”.

68 In oral submissions made at the hearing, the advocate who appeared for Lucky S submitted that I should articulate “levels of culpability” which he went on to explain should be at four levels. He said that the highest level should be when the contravention is committed by the permit holder as skipper of the relevant boat because that person would be in total control of the relevant fishing operations. He said that the second level would be where the principal offender was a company which was in effect the alter ego of a controlling individual as was the case in Woodley. The third category would be where the offender is commercially connected to the principal offender in some way and has full knowledge of the contravention. He called this offender “the active situational offender”. The fourth category is the present case. He described the entity in the position of Lucky S here as “the passive situational offender”.

69 I do not think that it is helpful to approach the imposition of a civil penalty in the present case by postulating overly rigid categories of offender. The correct approach must be for the Court to have regard to all relevant matters, as required by s 481(3) of the EPBC Act, which matters include those matters adumbrated in s 481(3)(a) to (d) of that Act.

70 In the present case, when regard is paid to the nature and extent of the contravention and the circumstances in which the contravention took place (as to which see s 481(3)(a) and (c)), I consider that the conduct which constituted the contravention by Lucky S is at the lower end of the scale. Nonetheless, it seems to me that it should have taken appropriate steps to ensure that it was accurately informed of the location of the boundaries of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve so that it could then take further steps to ensure that Mr Colville was also aware of those boundaries. Had it taken those steps, it is likely that Mr Colville would not have contravened s 354(1)(f) of the EPBC Act and that Lucky S would not have been liable for his contravention. But it took no steps at all to ensure that Mr Colville did not conduct fishing operations in the Reserve. It should have made sure that Mr Colville knew precisely where he could and could not conduct commercial fishing operations by looking at the relevant maps itself and by discussing the boundaries of the Reserve and the WDTF with Mr Colville. Its nonchalant attitude to these matters left Mr Colville in a state of ignorance. Although neither Mr Colville nor Lucky S made any profit as a result of the contraventions, that outcome was not the intended outcome. Both parties intended to derive profit from Mr Colville’s fishing operations. Mr Colville hoped and expected to catch fish and to sell his catch at a profit. Lucky S hoped and expected to continue to exploit the relevant permit for its financial benefit. The contravening conduct in both cases was plainly directed to making profit. Finally, it must also be remembered that Mr Skoljarev had been reminded in 2007 to take care to ensure that Lucky S did not contravene the EPBC Act because conduct in contravention of that Act had the potential to cause significant harm to the environment. The correspondence which he received in 2007 should have put him on guard. His failure to do anything at all to brief Mr Colville in 2010 is all the more serious in light of that correspondence.

71 The protection of the Ningaloo Marine Reserve is a matter of considerable importance. The conduct undertaken by Mr Colville has most likely caused some damage to the sea floor and canyon sides in the Reserve although it is not really possible to quantify that damage.

72 It seems to me that, in all the circumstances, an appropriate penalty prior to the application of a discount for the fullest co-operation on the part of Lucky S would be in the range $44,000–$55,000 which is a range between 8% and 10% of the maximum penalty. I think that the appropriate penalty before discount for co-operation is $49,500.

73 In argument before me, Counsel for the Minister accepted that a discount for co-operation of the order of 30% was appropriate in the present case. I propose to apply such a discount.

74 When that discount is applied to the amount of $49,500, a penalty of $34,650 is arrived at.

75 For the reasons which I have explained, I propose to impose a civil penalty of $34,650 on Lucky S. It was not suggested on behalf of Lucky S that a penalty of $34,650 would be so high as to be oppressive.

76 I will also make the declaration sought by the Minister and give effect to the parties’ agreement as to costs.

77 There will be orders accordingly.

| I certify that the preceding seventy-seven (77) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Foster. |

Associate: