Seven Network Limited v Commissioner of Taxation [2014] FCA 1411

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Applicant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

1. Each of the payments totalling $97,742,609, made by the applicant to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) pursuant to the Signal Utilisation Deed dated 30 September 2005 between the applicant and the IOC (Amounts in Dispute), is not a royalty within the meaning of paragraph 3 of Article 12 of the Agreement between Australia and Switzerland for the Avoidance of Double Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income, Australian Treaty Series 1981 No. 5.

2. The applicant is and was not liable under section 12-280 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) to withhold any amount from the Amounts in Dispute.

3. The applicant is and was not liable under section 16-30 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) to pay any penalty for failing to withhold from the Amounts in Dispute an amount as required by Division 12 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth).

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

4. The appeal in proceeding NSD 146 of 2012 be allowed.

5. The respondent’s objection decisions be set aside and be remitted to the respondent for determination according to law.

6. Proceedings NSD 146 of 2012 and NSD 148 of 2012 be listed for further directions at 9:30am on 3 February 2015 on the question of costs, including on the question of a lump sum costs order.

7. Each party have liberty to apply on three days’ notice.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 146 of 2012 NSD 148 of 2012 |

BETWEEN: | SEVEN NETWORK LIMITED Applicant |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent |

JUDGE: | BENNETT J |

DATE: | 22 DECEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

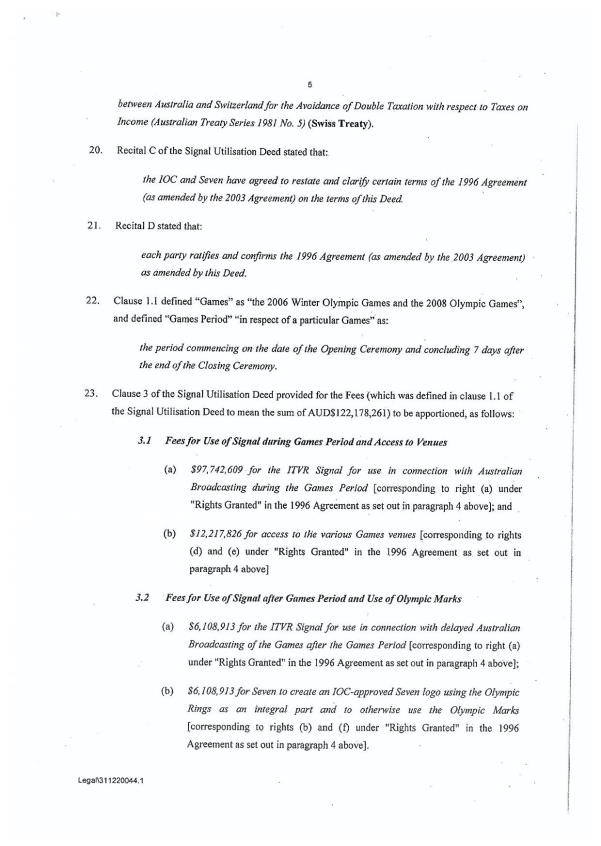

1 Seven Network Limited (Seven) made a series of payments between March 2006 and August 2008 to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for the broadcasting rights to the Olympic Games. Those payments totalled $122,178,261 (Payment). The Payment was consideration for the Signal Utilisation Deed (as defined below), including the “use” of a signal, the ITVR Signal, which was used by Seven in its live television broadcasts in Australia of the 2004, 2006 and 2008 Olympic Games (relevant Olympic Games).

2 At all material times, the IOC was a resident of Switzerland and was subject to an unlimited tax liability in Switzerland. The Commissioner of Taxation (Commissioner) contends that Seven, a resident corporation, was obliged to withhold part of the Payment on account of the IOC’s liability for withholding tax.

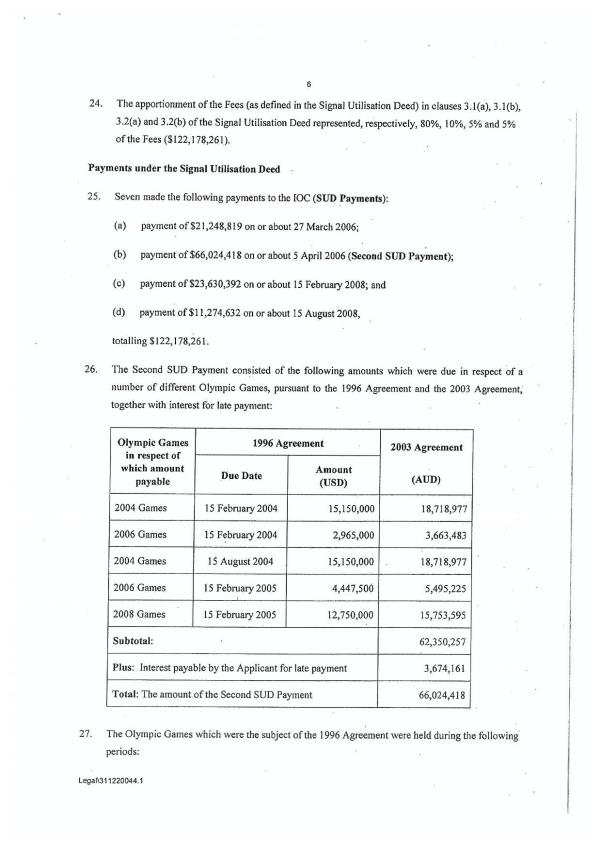

3 It is common ground that, as to 10% of the Payment, Seven was not required to withhold tax because, at least to that extent, the payments were not royalties. It is also common ground that, as to a further 10% of the Payment, Seven was required to, and did, withhold tax because, at least to that extent, the payments were royalties. The remaining 80% of the Payment, or $97,742,609, is in dispute (Amount).

4 The pleadings give rise to two substantive questions:

Whether the Payment made by Seven, to the extent that it was apportioned to the grant or use of the rights referred to in clause 3.1(a) of the deed entered into between Seven and the IOC on 30 September 2005 (Signal Utilisation Deed), was a royalty within the meaning of Agreement between Australia and Switzerland for the Avoidance of Double Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income [1981] ATS 5 (Swiss Treaty).

Whether the second payment under the Signal Utilisation Deed was as to 90% consideration for the use by Seven or its right to use certain “Broadcast Rights” within the meaning of the 1996 Agreement (as defined below): see para 13.4 of the Amended Defence filed 6 December 2012.

5 The second of these issues, arising from paragraph 13.4 of the Amended Defence, was subsequently abandoned during the course of the hearing.

6 By reason of the Swiss Treaty, specifically paragraph 3 of Article 12, and s 12-280 of Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (Taxation Administration Act), Seven’s obligation to withhold depends on whether the payment to the IOC was a “royalty”. This turns on whether the Payment was consideration for the use of, or right to use, ‘copyright or other like property or right’ within Art 12(3) of the Swiss Treaty. The relevant rate of withholding tax pursuant to Art 12(2) of the Swiss Treaty is 10%.

7 The Swiss Treaty is incorporated into Australian domestic law by virtue of s 11E of the International Tax Agreements Act 1953 (Cth) (International Tax Agreements Act). The whole of the Swiss Treaty has been enacted into domestic legislation. Their Honours noted in McDermott Industries (Aust) Pty Limited v Commissioner of Taxation (2005) 142 FCR 134 (McDermott) that the International Tax Agreements Act provides, subject to exceptions not presently relevant, that it and thus the double taxation agreements scheduled to it both prevail over provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (1936 Act) and the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (1997 Act) (at [11]). As their Honours further noted at [12], s 17A of the International Tax Agreements Act makes it clear that the provisions of s 128B of the 1936 Act, which operate domestically to impose withholding tax on royalties, are to have no operation if a provision in a double taxation agreement operates to exclude a payment that is otherwise a royalty from the royalty provisions of the treaty.

8 The definition of “royalties” as contained in the Swiss Treaty is given primacy over that in the 1936 Act by virtue of the operation of ss 4(2) and 17A(5) of the International Tax Agreements Act.

9 The Commissioner emphasises that the relevant taxpayer is the IOC, not Seven, and that the issue in the proceedings is the extent to which the Payment had the character of royalty income in the IOC’s hands, to be determined taking into account the substance, not just the form, of the transaction.

10 Assuming the IOC’s liability to pay income tax pursuant to s 128B of the 1936 Act, it is liable as a non-resident for withholding tax on royalties paid by a resident to a non-resident (ss 128B(2B) and 128B(5A)). Section 12-300 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act provides that there is no requirement to withhold from a “royalty” under s 12-280 of that Act if no withholding tax is payable.

11 On 25 October 2005, Seven made a request for a private ruling for the purposes of former Part IVAA of the Taxation Administration Act in relation to, among other things, the deductibility under s 8-1 of the 1997 Act of the Payment.

12 On 12 April 2006, the Commissioner issued a notice of private ruling to the following effect:

Seven had no obligation to withhold tax in respect of the payments under clause 3.1(b) of the Signal Utilisation Deed and those payments were accordingly deductible.

The payments made by Seven under clauses 3.2(a) and 3.2(b) of the Signal Utilisation Deed were deductible, and Seven had appropriately withheld the amount of 10% from each.

The payments made under clause 3.1(a) were “royalties” within the Swiss Treaty and Seven could not deduct them in circumstances where it had failed to withhold on account of the tax.

13 It is this latter conclusion that is the subject of these proceedings.

14 The Commissioner issued Seven with three notices of penalty dated 6 June 2007, 31 October 2008 and 23 December 2009 (Penalty Notices). Seven lodged an objection against each of the Penalty Notices.

15 The Commissioner, in his Notice of objection decision dated 2 December 2011 (Notice of Decision), concluded that the Amount is characterised as a “royalty” for the purposes of the Swiss Treaty as:

the transmission of the footage of the relevant Olympic Games “via” the ITVR Signal was the transmission of a cinematograph film; or

the transmission of the footage of the relevant Olympic Games “via” the ITVR Signal was the “use of, or the right to use, a property or right that is like a copyright”; or

the transmission of the footage of the relevant Olympic Games “via” the ITVR Signal was use of, or the right to use, motion picture films or films for use in connection with television.

16 These are not identical to the bases of the Commissioner’s submissions in these proceedings.

THE CURRENT PROCEEDINGS

17 Seven has commenced two proceedings. NSD 146 of 2012 constitutes a Part IVC appeal against the Commissioner’s Notice of Decision in relation to the Penalty Notices. In that proceeding the issue is whether the Commissioner’s decision not to remit penalties should not have been made or should have been made differently: s 14ZZO of the Taxation Administration Act. In NSD 148 of 2012, Seven seeks declarations that:

he Amount is not a “royalty” within the terms of Art 12(3) of the Swiss Treaty.

Seven is and was not liable under s 12-280 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act to withhold any amount from the Payment.

Seven is and was not liable under s 16-30 of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act for penalties for failing to withhold.

18 Seven also seeks an order setting aside the Penalty Notices.

19 Seven seeks an alternative declaration that the amount is not a royalty within the definition of that term in s 6(1) of the 1936 Act. However, as noted above, ss 4(2) and 17A(5) of the International Tax Agreements Act give primacy to the definition of “royalties” as contained in the Swiss Treaty over that in the 1936 Act. Submissions were directed to the definition of “royalties” in the Swiss Treaty and not to the definition in the 1936 Act. I shall not consider the latter further.

ARTICLE 12 OF THE SWISS TREATY

20 In McDermott, the Full Court discussed some aspects of double taxation agreements. As their Honours said at [2], the purpose of a double taxation agreement, being the avoidance of double taxation, is given effect in part by allocating exclusively to one or the other contracting state the power to tax certain classes of income. Another theme found in all double taxation agreements, their Honours said at [3], is that certain forms of income such as, relevantly royalties, will be taxed in the country of source by withholding at a rate which is set by the double taxation agreements. In the case of income by way of “royalty”, as defined, the rate of withholding tax is capped at 10% of the gross royalty. While their Honours were talking about a double taxation agreement with Singapore, the same rate applies in the present case. There is no dispute that the IOC may rely on the Swiss Treaty. There is no dispute that payments may only be taxed in Australia to the extent that they are “royalties” within Art 12(3) of the Swiss Treaty.

21 Article 12 relevantly provides:

1. Royalties arising in one of the Contracting States being royalties to which a resident of the other Contracting State is beneficially entitled, may be taxed in that other State.

2. Such royalties may be taxed in the Contracting State in which they arise, and according to the law of that State, but the tax so charged shall not exceed 10 per cent of the gross amount of the royalties.

3. The term "royalties" in this Article means payments (including credits), whether periodical or not and however described or computed, to the extent to which they are consideration for the use of, or the right to use, any copyright, patent, design or model, plan, secret formula or process, trade-mark, or other like property or right, or industrial, commercial or scientific equipment, or for the supply of scientific, technical, industrial or commercial knowledge or information, or any assistance of an ancillary and subsidiary nature furnished as a means of enabling the application or enjoyment of such knowledge or information or any other property or right to which this Article applies, or for the use of, or the right to use, motion picture films, films or video tapes for use in connection with television or tapes for use in connection with radio broadcasting, or for total or partial forbearance in respect of the use of a property or right referred to in this paragraph.

(emphasis added)

22 For the purposes of Arts 12(1) and 12(2), Switzerland is the “other” State, and Australia is the “Contracting State”. Under Art 12(5), a royalty arises in Australia resulting from a payment made by an Australian resident to a Swiss resident for the use of something in Australia. That Swiss resident may be taxed in Switzerland for the moneys so received as ordinary income or on some other basis, notwithstanding that the royalty arises in Australia. Australia is given the right to tax the same royalty by withholding at up to 10% if, when it is paid, it is a royalty as defined.

23 As the royalty arises in Australia, it is governed by Australian law and is a royalty to which the resident of Switzerland is beneficially entitled. The obligation to withhold is imposed upon Seven only if what it pays, when it pays it, is a royalty. Under s 128B of the Taxation Administration Act, the taxation is on the payment of the royalty, not the receipt of the payment. That is, the liability to deduct withholding tax is imposed upon a resident payer of a “royalty” who paid that royalty to a non-resident. In order to avoid double taxation, under Art 12(2) Australia may tax Australian royalties up to a maximum of 10%. Under Art 22 of the Swiss Treaty, where a resident of Switzerland derives income dealt with by the Swiss Treaty and which, as a result of the Swiss Treaty, may be taxed in Australia, Switzerland shall exempt such income from Swiss tax but may, in calculating tax on the remaining income of that person, apply the rate of tax which would have been applicable if the exempted income had not been so exempted.

RELEVANT AGREED FACTS

24 The parties have prepared a Statement of Agreed Facts dated 15 October 2013, a copy of which is appended to these reasons.

25 The key facts as agreed between the parties are as follows:

On or about 12 January 1996, Seven entered into an agreement with the IOC for the ‘exclusive Australia broadcast rights in respect of’ the relevant Olympic Games (1996 Agreement). The 1996 Agreement was subject to a number of amendments and restatements, including a 2003 reiteration to address concerns about AUD/USD exchange rates, among other things (2003 Agreement).

Pursuant to the 1996 Agreement, Seven agreed to pay the IOC fees in US dollars (Rights Fees), as set out in Schedule 1 to the 1996 Agreement.

Between 1 July 1997 and 30 June 2002, the IOC had a tax exempt status as it was a prescribed association for the purposes of s 50-70(c) of the 1997 Act.

On 30 September 2005, Seven and the IOC entered into the Signal Utilisation Deed.

Between 19 February 2002 and 11 February 2007, Seven Network (Operations) Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of Seven, entered into deeds for each of the relevant Olympic Games with the IOC and the relevant Organising Committee in respect of exclusive “visual broadcast rights” (Television Agreements).

The Signal Utilisation Deed

26 Clause 5 of the Signal Utilisation Deed provided that:

During the Games Period, Seven shall be the copyright owner in Australia of all depictions, transcriptions, recordings and television (visual broadcast) and audio broadcasts, or other dissemination by any means of the Games produced from ITVR Signal for the purposes of Australian Broadcasting, by or on behalf of, Seven in Australia (“Copyright”). At the end of the particular Games Period, Seven assigns to the IOC the Copyright.

(emphasis added)

27 “ITVR signal” was defined in the Signal Utilisation Deed as ‘the international television signals (picture and sound) to be produced by the host broadcaster appointed by the Organising Committee of Games events’. The parties’ experts, in their Joint Statement of Experts filed 30 July 2013 (Joint Experts’ Report) define “ITVR Signal” as ‘a signal which transmitted to Olympic Broadcaster in the IBC the Host Broadcaster’s ITV Coverage and IR Coverage for a field of play contested on a given day at the Games’.

28 The International Broadcast Centre, or IBC, is defined in the Joint Experts’ Report as ‘a building in the Host City at each Games which housed certain Host Broadcaster facilities and also each Olympic Broadcaster’s television and radio production space at the Games’.

29 “Games” was defined in clause 1.1 as ‘the 2006 Winter Olympic Games and the 2008 Olympic Games’ and “Games Period” as ‘the period commencing on the date of the Opening Ceremony and concluding 7 days after the end of the Closing Ceremony’.

30 Prior to the execution of the Signal Utilisation Deed, Seven did not own the copyright in the television broadcasts which Seven made of the Olympic Games.

31 “Fees” was defined in clause 1 of the Signal Utilisation Deed to be AUD$122,178,261, to be broken down in accordance with clause 3:

3.1 Fees for Use of Signal during Games Period and Access to Venues

The Fees are apportioned as follows:

(a) $97,742,609 for the ITVR Signal for use in connection with Australian Broadcasting during the Games Period; and

(b) $12,217,826 for access to the various Games venues

3.2 Fees for Use of Signal after Games Period and Use of Olympic Marks

The Fees are apportioned as follows:

(a) $6,108,913 for the ITVR Signal for use in connection with delayed Australian Broadcasting of the Games after the Games Period; and

(b) $6,108,913 for Seven to create an IOC-approved Seven logo using the Olympic Rings as an integral part and to otherwise use the Olympic Marks.

Payments made by Seven

32 Seven withheld amounts in respect of royalty withholding tax from each of the above payments, being the part of the Payment referable to clauses 3.2(a) and 3.2(b) of the Signal Utilisation Deed. Seven did not withhold amounts in respect of royalty tax from each of the payments referrable to clauses 3.1(a) or 3.1(b) of the Signal Utilisation Deed. As noted above, the Seven’s approach to withholding amounts from the payments made under clauses 3.1(b), 3.2(a) or 3.2(b) are not in dispute.

33 The disputed Amount of $97,742,609 corresponds to the payment made in accordance with clause 3.1(a) for the ITVR Signal for us in connection with Australian broadcasting by Seven of the defined Olympic Games during the relevant period. Nothing was withheld by Seven on account of royalty withholding tax with respect to the Amount.

The ITVR Signal

34 The expert evidence concerns the technical aspects of providing the broadcast of the relevant Olympic Games, including an explanation of the nature of the ITVR Signal.

35 Seven’s expert, Trevor Bird, is Seven’s General Manager, Group Technical Services and is a qualified electrical engineer with a specialisation in broadcast engineering. He has worked on the engineering aspects of every Seven broadcast of the Olympic Games since 1992, excluding the Nagano Olympic Winter Games in 1998 and the Sydney Olympic Summer Games in 2000. Mr Bird was responsible for all the engineering infrastructure for the relevant Olympic Games.

36 The Commissioner’s expert, Mr David Elliot, is a consultant in television engineering and media technology. He was employed by the American Broadcasting Corporation for over 30 years, holding various roles in broadcast operations and engineering, including involvement in broadcasting the 1968, 1980 and 1984 Olympic Games, and leadership roles in the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Games.

37 The Joint Experts’ Report sets out what is undisputed:

What is an ITVR Signal

1.4 The ITVR Signals as received by Seven at the Games were electromotive forces that transmitted data to some form of Receiving Device.

1.5 The ITVR Signals were always received by Seven on copper coaxial cable at the Games as an electromotive force. However the contribution system delivering the ITVR Signals from the OBC to the IBC may also have used light or radio frequency methods.

1.6 On a copper cable, the signal is transmitted via a linkage of copper atoms. Copper is a conductor which allows electron movement. The signal at one end of a copper cable causes electron movement along that cable and that electron movement manifests itself as a change in potential that forms the signal at the other end of the conductor. In the case of television signals, the data transported by this signal, such as binary numbers (in the case of a digital signal), can be converted by a receiving device into television coverage (that is, images and sounds).

1.7 There is no picture, image or sound recorded or permanently stored in the copper coaxial cable that transmits a signal. This is because a signal does not exist in isolation within a cable. If the cable is disconnected from its signal source, such as a camera, microphone or other device, there will be no signal left in the cable.

1.8 No picture, image or sound can be recorded or permanently stored in a signal. This is because a signal is not tangible and does not give physical form to an image or sound.

1.9 Visual images and sounds cannot be reproduced from an ITVR Signal, although they can be produced from an ITVR Signal with the use of a Receiving Device.

1.10 The ITVR Signals were received by Seven live (that is, in real time) in its space at the IBC. By way of a large number of cables connected to Seven’s space at the IBC, Seven could access multiple ITVR Signals (one for each field of play) simultaneously.

1.11 With the exception of the SSM Replays and Iso Record Replays, the ITV Signals received by Seven were not copies or replays of signals that had previously been recorded or otherwise permanently stored by the Host Broadcaster. In addition, IR Signals were purely live and conveyed no recorded material at all.

The ITV Signal

1.12 Each ITV Signal was a television signal. This television signal transmitted data which could be converted by a Receiving Device into the visual images and sounds comprising the Host Broadcaster’s ITV Coverage of each field of play, to Olympic Broadcasters in their spaces at the IBC.

I .13 A television signal transmits data that can be converted by a Receiving Device, such as a television, into television coverage (comprised of images and sounds). It is comprised of a video signal and audio signals, often along with ancillary data. The audio signal transmits data that can be converted into sounds which are mixed to correspond to the images transmitted by the video signal.

1.14 Video signals can be created by a television camera, which converts light energy into an electromotive force conveying a stream of data capable of being converted by a television or other device into a repeated sequence of still images on a television screen.

1.15 The television cameras used by Host Broadcasters at the Games to generate the video component of the ITV Signal were either Camera Heads (that is, self-contained field cameras or camcorders), or Camera Heads connected to a CCU. The CCU for each Camera Head was located in the OBC at each Games venue. In addition to cameras, graphics machines and audio/video recorders (servers) were used by the Host Broadcaster in the generation of a particular ITV video signal.

1.16 The Camera Heads at each of the Games venues created a digital signal by splitting the light perceived at the field of play into three separate image components of red, green and blue. Each element of each image component was then converted into a sequence of binary numbers (zeros and ones). This process is repeated each 1/50th or 1/50th of a second, (depending on the television frame rate provided by the Host Broadcaster). The Camera Head or the CCU (if used) combined the three binary number sequences into a continuous stream of data that could be constructed by the receiving device into a repeated sequence of still images, which represented the video component of the ITV Coverage of the events perceived by the camera.

1.17 Audio signals can be created by a microphone. The microphone converts sounds into an analogue audio signal that can be interpreted by an audio speaker into a reconstruction of the sounds originally perceived by the microphone.

1.18 At each Games, microphones were attached to an analogue to digital converter, which converted each analogue audio signal into a digital audio signal.

1.19 The digital audio signal output of the converter device was transmitted as a signal conveying a continuous stream of binary numbers and could be converted by a Receiving Device to replicate the sounds perceived by the microphone.

1.20 Each ITV Signal was created by the Host Broadcaster in the OBC in the following way:

(a) The video signals from the Camera Head or the CCU (if used) were transmitted to a Vision Switcher.

(b) A Graphics Device transmitted a graphics signal to the Vision Switcher, which was capable of adding graphics such as the Olympic logo and text recording World and Olympic records to the video signal. These effects were added according to directions given by the producer and director at each venue.

(c) The Host Broadcaster also operated Iso Record Devices and SSM cameras. SSM cameras were connected to a replay device at the OBC which recorded the images perceived by the SSM cameras. The operator of the Vision Switcher could switch from live video signals received from the television cameras (as described above) to replays of recordings from the Iso Record Device and SSM replay device.

(d) Each time the Host Broadcaster switched from live coverage to an Iso Record or SSM replay, the Host Broadcaster was required to denote the transition from live to replay, and from replay to live, with an Olympic Transition Sequence. Each Olympic Transition Sequence was introduced by an Olympic Transition Device connected to the Vision Switcher and which automatically inserted a pre-recorded transition sequence which would typically have been of 12 frames (1/2 second) duration. This Olympic Transition Sequence was a technique of the Host Broadcaster which allowed the viewer to easily identify when the Host Broadcaster switched from live coverage to replayed content.

(e) The output of the Vision Switcher was the video component of the ITV Signal for a field of play. This video signal was not recorded or permanently stored by or within the Vision Switcher. It was sometimes temporarily held within the Vision Switcher for approximately 1/25th of a second for the purposes of synchronisation. The portion of the ITV Signal that could be held in this way was no more than 1/25th of a second’s worth (equivalent to one frame). If the power to the vision switcher were removed, the video sign al could not be retrieved.

(f) The audio component of the ITV Signal was created by the Host Broadcaster from audio signals received from microphones it had installed at various places throughout each Games venue.

(g) The Host Broadcaster switched between or mixed the audio signals received from microphones placed throughout the venue to create an audio signal that corresponded to the video signal output of the Vision Switcher.

(h) The ITV video and audio signals were then combined to create the ITV Signal.

The IR Signal

1.21 The IR Signal was another audio signal generated by the Host Broadcaster in the OBC. Each IR Signal transmitted data that could be convened by a receiving device into the Host Broadcaster’s IR Coverage of each field of play. In contrast to the ITV audio signal, the IR Signal was a continuous coverage of sounds from each Games venue compiled for use by Olympic Broadcasters in creating radio broadcasts of the Games. It was not mixed to correspond to the ITV video signal.

The ITVR Signal

1.22 The IR Signal was embedded into the ITV Signal by the Host Broadcaster at the OBC to create the ITVR Signal.

1.23 Data capable of conversion into the ITV Coverage and IR Coverage was received by Olympic Broadcasters via the ITVR Signal. This data could be decoded and converted into visual images and sounds by appropriate equipment such as a television.

Transmission of the ITVR Signal

1.24 Each ITVR Signal was created at the venue and could be distributed at the venue or the IBC.

1.25 The Host Broadcaster transmitted each ITVR Signal over copper coaxial cable to a telecommunications carrier that accessed the ITVR Signal at a TDP within the OBC.

1.26 The telecommunications carrier transmitted the ITVR Signal from the OBC to the IBC where it was delivered to the Host Broadcaster at another TDP.

1.27 In the OBCs at the competition venues at the Games, Seven did not provide or acquire any unilateral production facilities, other than some isolated cameras and commentator audio (see Bird's first affidavit. paragraph 124(b)). Thus Seven was dependent on the capabilities of the Host Broadcaster, and distribution and reception of the ITVR Signal content.

1.28 The Host Broadcaster received the ITVR Signals at the IBC and distributed the ITVR Signals to Olympic Broadcasters’ spaces in the IBC over copper coaxial cables.

1.29 The time duration between the occurring of a Games event and the delivery of the ITVR Signals to Olympic Broadcasters within the IBC was, in most cases, virtually instantaneous. In some cases there was a delay of no more than 0.6 of a second. Where such a delay occurred, typically 0.35 of a second was attributable to the process required to encode the ITVR Signal. The remainder of the delay, typically 0.25 of a second, was attributable to the time taken to transmit the ITVR Signal from a satellite uplink facility to a satellite and back to the IBC. This process did not involve any recording or storage of the ITVR Signal.

1.30 Seven used the ITVR Signals provided to it by the Host Broadcaster as a basis to create its broadcasts to the Australian public. The ITVR Signal was not suitable for broadcast purposes in its “raw” form: it was the major ingredient in the broadcasts Seven made, along with the commentary and commercials added by Seven.

1.31 In their production facilities at the IBC, the Olympic Broadcasters almost always had their own storage devices to ensure that the broadcast is timed to the period set for release to the home audience. Other devices are present to ensure the synchronizat ion of audio and video, since the synchronization of video/video and video/audio may be disrupted by the latencies of the numerous digital devices in the stream.

Production of the TV Coverage and IR Coverage

1.32 The Olympic Broadcasters generally have some discrete facilities at the IBC where they are able to process and organize their broadcast signal for transmission to their home country. These facilities were used by Olympic Broadcasters to prepare their broadcasts, by inserting their own commentary, unilateral camera feeds, their own logos and graphics, “clips” of local interest, and sequencing and synchronizing the transmissions to their network schedule.

1.33 In addition to the ITVR Signals, the Host Broadcaster also produced a variety of generic edited features. “B-rolls” of background material as well as short features with information on the Olympic city and sites were also provided. The use of this material was at the discretion of each Olympic Broadcaster.

1.34 Seven could request, upon payment of a fee additional to the fee paid under the 1996 Agreement and/or the Signal Utilisation Deed, the following from the Host Broadcaster:

(a) its own unilateral camera or cameras to be set up at a venue;

(b) provision of commentator positions at the venue;

(c) access to archival and other recordings; and

(d) video or audio signals from specified Host Broadcaster cameras or microphones,

for delivery to Seven’s space in the IBC.

1.35 Each Olympic sports venue is unique in its layout and coverage. The Host Broadcaster’s television pre-production planning usually begins as much as two to three years ahead of the actual event with surveys and pre-production visits and planning.

1.36 Beginning months before the Games, installation of equipment and cabling begins. In some instances this may occur more than a year in advance, for example where installation is complex or access is difficult.

1.37 The production crew works together as a team, and the ITVR Coverage from each venue is the combined result of the efforts of the entire crew at that venue. While an event is active, the crew is in constant motion, switching cameras and audio, inserting and changing graphics elements, and activating and replaying audio and video captures; all at the command of the producer and director.

1.38 The ITVR Signal itself is a complex, constantly changing aggregation of video, one or more audio and multiple data channels. The audio at the Beijing Olympics was produced in Dolby 5.1 surround sound. This meant there was an active mix of right, left, centre, rear left and right, and effects audio sources with each video signal, which varied as the perspective varied with the video.

1.39 The discrete ITVR Signals from each of the venues were fed to the IBC via coaxial cable, fibre, microwave, satellite transmission, or some combination of these methods.

1.40 In a modem television plant, these signals are in digital format, encoded to an International Standard; usually one of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE), European Broadcasting Union (EBU), or International Television Union (ITU) Standards.

1.41 The sets of audio and video data in a television signal create a serial digital stream. Where the stream is High Definition television, the data is encoded at a very high rate, approximately 1.5 Gbit/sec. This requires specialized interfaces at both transmission and reception ends of the signal chain to handle the data speed.

1.42 The ITVR Signals were encoded and combined digital signals, including translation of data to a special sequence suitable for transmission, as well as such elements as the addition of forward error correcting bits and synchronization packets. While other data elements are also provided for in the data packets, such as time code and multiple audio channels, the HD stream also contains provisions for advanced metadata, or “data about the data”. This included such things as geographical references, camera angles, program titles, information about the scene, and other production values.

1.43 Unlike many other data applications (such as email transactions), with high-speed video applications each frame must be transmitted and received correctly, sincere transmission of data packets to correct a failure is not feasible where data is continuously streaming in a television application, and the result of frame errors will be instantly obvious to the viewer.

1.44 The purpose of communication is to transmit information. The information is encoded by the sender and decoded by the receiver. In the model, it does not matter whether the transmission medium is sound pressure or light waves, radio frequencies or smoke signals. The important thing is to ensure the accurate encoding/decoding of the information.

38 In addition, Mr Bird explained that while the ITVR Signal was recorded by the host broadcaster for the purpose of storage and later retrieval, the ITVR signal was “split” and so the ITVR Signal which reached its ultimate destination at the IBC for live coverage did not traverse a recording device.

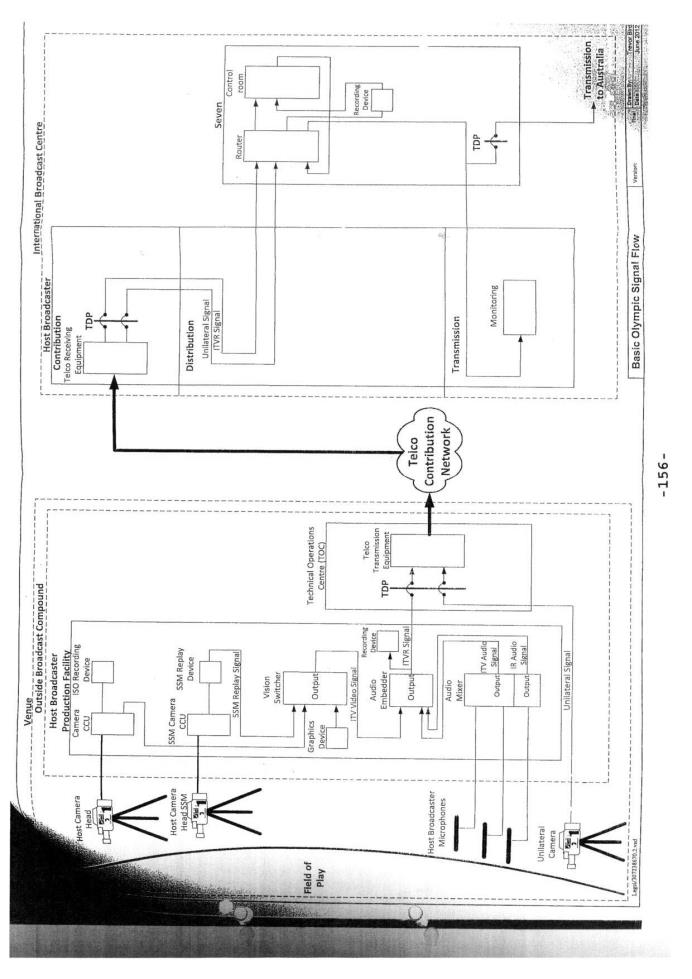

39 The following diagram has been reproduced from Mr Bird’s evidence:

40 In summary, the experts agree that:

The ITVR Signal was transmitted by the relevant host broadcaster to Seven’s master control room at the IBC.

Each ITVR Signal comprised an International Television (ITV) and International Radio Signal (IR).

The ITV and IR Signal were produced by the host broadcaster and combined and transmitted live to the IBC for distribution to each Olympic broadcaster, such as Seven.

Each Olympic broadcaster could use or alter the ITV or IR Signal as it saw fit to create its broadcast signal.

The ITVR Signal was not suitable for broadcast purposes in its “raw” form.

The ITVR Signal was the major ingredient in the broadcasts which Seven made, together with commentary, commercials, background pre-produced vignettes and short features which might be added by Seven.

Each ITVR Signal was an encoded and combined digital signal, transmitted virtually and instantaneously to each Olympic broadcaster.

The process of transmitting the ITVR Signal from the host broadcaster to each Olympic broadcaster did not involve any recording or storage of the ITVR Signal.

The ITVR Signal was received by Seven on a copper coaxial cable i.e. it was an electromotive force that transmitted data. There was no picture, image or sound recorded or permanently stored in the copper coaxial cable that transmits the signal.

No picture, image or sound can be recorded or permanently stored in a signal.

The signal is not tangible and does not give physical form to an image or sound.

Visual images and sounds cannot be reproduced from an ITVR Signal.

The ITVR Signal was a live signal and was not stored or recorded prior to being obtained (with one minor exception which is not presently relevant).

Seven and the host broadcaster could simultaneously record and store the signal as it was being transmitted, however the ITVR Signal received by Seven was not taken from this recorded version.

41 The data transported by the ITVR signal could be converted into television coverage, that is, visual images and sounds, by use of a receiving device. This means that, as transmitted and as received, the signal was a continuous stream of data, from which visual images and sounds could be seen and understood, but only by use of appropriate equipment.

42 The agreed expert evidence is that there is no technology that allows the information transmitted by the signal to be reproduced.

43 The evidence on which both parties rely is that the camera head converts light energy that can be interpreted by television into a repeated sequence of still images which the human eye interprets as if it were perceiving the moving events seen by the camera. The camera head converts an image into a digital signal by sampling a number of pixels presented to the lens and converting them into ‘a binary representation of their amplitude at that particular moment’. Each pixel is represented as a unique sequence of binary digits, representing ‘a continuous stream of data that can be reconstructed later by a television receiver into a series of still images on the television screen’ (emphasis added).

44 Although recordings were made at the IBC, they were not distributed to broadcasters such as Seven unless, for example, the broadcaster missed recording an ITVR Signal. They were a “protection copy”, or library copy, for future replay if required. They were never transmitted as live ITVR Signal to broadcasters.

45 Generally, many ITVR and unilateral signals were distributed to the broadcasters by the host broadcaster within the IBC at the same time. In most cases the delivery was virtually instantaneous. In some cases they were delivered within no more than 600 milliseconds of the activities taking place on the field of play, which is regarded as “real time”.

IS THERE COPYRIGHT IN THE ITVR SIGNAL?

46 Seven asserts, and it is not in dispute, that the question whether copyright exists in the ITVR Signal is to be decided under Australian law. Copyright is a statutory right that subsists, and is determined and characterised, in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the Act). Australian copyright law does not protect the dissemination of information per se. The Act recognises categories of subject matter that may be subject to copyright:

(a) original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works (Part III, ss 10 and 32); and

(b) subject-matter other than works (Part IV: being sound recordings (s 89), cinematograph films (s 90), television broadcasts and sound broadcasts (s 91) and published editions of works (s 92).

Relevant provisions of the Act

47 Section 85 provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a sound recording, is the exclusive right to do all or any of the following acts:

(a) to make a copy of the sound recording;

(b) to cause the recording to be heard in public;

(c) to communicate the recording to the public;

(d) to enter into a commercial rental arrangement in respect of the recording.

(2) Paragraph (1)(d) does not extend to entry into a commercial rental arrangement in respect of a sound recording if:

(a) the copy of the sound recording was purchased by a person (the record owner) before the commencement of Part 2 of the Copyright (World Trade Organization Amendments) Act 1994; and

(b) the commercial rental arrangement is entered into in the ordinary course of a business conducted by the record owner; and

(c) the record owner was conducting the same business, or another business that consisted of, or included, the making of commercial rental arrangements in respect of copies of sound recordings, when the copy was purchased.

48 Section 86 provides:

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a cinematograph film, is the exclusive right to do all or any of the following acts:

(a) to make a copy of the film;

(b) to cause the film, in so far as it consists of visual images, to be seen in public, or, in so far as it consists of sounds, to be heard in public;

(c) to communicate the film to the public.

49 Sections 85 and 86 identify the exclusive rights conferred by copyright in sound recordings (s 85) and cinematograph films (s 86). One of the former is “to make a copy of the sound recording” (s 85(1)(a)); one of the latter is “to make a copy of the film” (s 86(a)). Each category of infringing act in these categories will involve copying to produce a material embodiment where there was an anterior material embodiment.

50 Section 10(1) relevantly provides:

broadcast means a communication to the public delivered by a broadcasting service within the meaning of the Broadcasting Services Act 1992. For the purposes of the application of this definition to a service provided under a satellite BSA licence, assume that there is no conditional access system that relates to the service.

cinematograph film means the aggregate of the visual images embodied in an article or thing so as to be capable by the use of that article or thing:

(a) of being shown as a moving picture; or

(b) of being embodied in another article or thing by the use of which it can be so shown;

and includes the aggregate of the sounds embodied in a sound‑track associated with such visual images.

copy, in relation to a cinematograph film, means any article or thing in which the visual images or sounds comprising the film are embodied.

material form, in relation to a work or an adaptation of a work, includes any form (whether visible or not) of storage of the work or adaptation, or a substantial part of the work or adaptation, (whether or not the work or adaptation, or a substantial part of the work or adaptation, can be reproduced).

51 Sections 21(1), 21(1)(1A) and 21(6) relevantly provide:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a literary, dramatic or musical work shall be deemed to have been reproduced in a material form if a sound recording or cinematograph film is made of the work, and any record embodying such a recording and any copy of such a film shall be deemed to be a reproduction of the work.

(1A) For the purposes of this Act, a work is taken to have been reproduced if it is converted into or from a digital or other electronic machine‑readable form, and any article embodying the work in such a form is taken to be a reproduction of the work.

(6) For the purposes of this Act, a sound recording or cinematograph film is taken to have been copied if it is converted into or from a digital or other electronic machine-readable form, and any article embodying the recording or film in such a form is taken to be a copy of the recording or film.

Note: The reference to the conversion of a sound recording or cinematograph film into a digital or other electronic machine-readable form includes the first digitisation of the recording or film.

52 Section 24 of the Act provides:

For the purposes of this Act, sounds or visual images shall be taken to have been embodied in an article or thing if the article or thing has been so treated in relation to those sounds or visual images that those sounds or visual images are capable, with or without the aid of some other device, of being reproduced from the article or thing.

(emphasis added)

53 Section 31(1)(a)(i) of the Act provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

(a) in the case of a literary, dramatic or musical work, to do all or any of the following acts:

(i) to reproduce the work in a material form;

…

54 It can be accepted that the Act encompasses material that originates in digital form (J Lahore, Copyright and Designs, (3rd ed, 1996), (Vol 1), par [8040], pp 8066-8067).

Principles

55 The Court has relevantly considered certain aspects of what constitutes a cinematograph film within the meaning of s 10(1) of the Act in specific technological contexts. As Gibbs CJ said in Computer Edge Pty Ltd v Apple Computer Inc (1986) 161 CLR 171, the Act should be given a liberal interpretation but it is not justifiable to depart altogether from its language and principles to protect technological developments which were not contemplated, or not completely understood, when the relevant provisions were enacted. That is, “embodied” should not be given a narrow construction. This approach was approved and applied by Wilcox J in Galaxy Electronics Pty Limited v Sega Enterprises Limited and Another; Gottlieb Enterprises Limited v Sega Enterprises Limited and Another (1997) 75 FCR 8 (Galaxy), with the proviso that the definition will apply to a new technology but only if that technology satisfies the words of the definition, liberally construed. As to “embodied”, Wilcox J said that the word refers to the giving of a material or discernible form to an abstract principle or concept, which therefore means that the abstraction must pre-exist the material manifestation. In that case, the visual images in the video games in that case did exist before the game was played and were embodied in the computer program, albeit in a different form (in the minds of the games’ creators) (at 18 per Wilcox J).

56 In Sega Enterprises Ltd v Galaxy Electronics Pty Ltd (1996) 69 FCR 268 (Sega), Burchett J considered the definition of cinematograph film in s 10(1) and the amplification of that definition in s 24 which, in turn, imported a consideration of how the word “embodied” is understood. Following a discussion of the personage of Lord Chancellor in Iolanthe and the observations of Lord Cranworth LC in Jefferys v Boosey [1854] EngR 816; (1854) 4 HLC 815; 10 ER 681, Burchett J concluded that “embodied” connoted giving a creation a form in which it could be held for continued existence and use. His Honour said (at [11]):

To narrow the sense of the word so as to confine an embodiment of a visual image to something in the nature of a frame, of which the image on the screen is a reflection, would be to introduce a limiting concept not inherent in the language.

57 His Honour continued (at [12]):

A novel or poem will generally be conveyed by the medium of writing; and a film by some means of showing its visual images upon a screen. But in neither case should the medium, through some narrow interpretation, be permitted to obscure an understanding of the subject matter of copyright.

58 His Honour drew upon the primacy of the statutory language while giving effect to the obvious legislative intent, which can be one that reasonably arises from the language which Parliament has used. Justice Burchett observed at [14] that in the case of copyright in a film, legislative history ‘shows plainly that Parliament did intend to take a broad view, and not to tie the copyright to any particular technology’ (emphasis in the original). His Honour concluded that the definition of “cinematograph film”, expressed as it is in terms of the result achieved rather than the means employed, points very strongly to intention to cover new technologies which do actually achieve the same result (at [15]). His Honour observed that this view was strengthened by the terms of s 24. Consequently, his Honour found that an aggregate of visual images is just that; an aggregate of visual images irrespective of the device or apparatus utilised to produce it. Further, the definition in s 10(1) of “copy” in relation to cinematograph film means any article or thing in which the visual images or sounds comprising the film are embodied. His Honour said (at [16]):

It cannot have been intended that the word “embodied” should, in this definition have a meaning which would allow computer technology, of the kind employed in the present case, to be utilised to mimic with impunity...

(emphasis in original)

59 On appeal (being the case of Galaxy as cited in [55] above ), the Full Court (Lockhart, Wilcox and Lindgren JJ) pointed out at 11, that Galaxy imported into Australia machines containing copies of the computer program that generated the visual images and sounds constituting a particular computer game.

60 The question considered by the Full Court was whether the video games were a cinematographic film. Justice Wilcox, with whom Lockhart and Lindgren JJ agreed, characterised Burchett J’s reasoning as a rejection of the notion that an embodiment of a visual image required something in the nature of a frame, as on a reel of film, of which the image is a reflection (at 15). Justice Wilcox upheld Burchett J in Sega, and found that video games fell within the s 10 definition of “cinematographic film” as ‘the visual images that constitute the moving picture are taken to have been ‘embodied’ in the computer program because the computer program was so treated in relation to those images as to be capable of reproducing them’ (at 20). The finding was based upon the fact that visual images were present to be aggregated.

61 In Galaxy, the appellant had argued that the reference to the aggregate of the visual images:

… [was] a reference to the frames which have always been the basic element of cinematograph films [and that] it cannot be a reference to individual visual elements within a single frame because the individual images on a single frame are not capable of being shown as a moving picture.

62 The appellants in Galaxy also argued that the video games did not embody a plurality of individual frames but rather generated individual frames from moment to moment. The respondents submitted that the appellants’ characterisation contained two essential errors, in that they confused the subject matter in which copyright subsists with the physical embodiment or material form in which it is made, and that it attempted to limit the concept of cinematograph film to frames.

63 The respondent had further argued (at 16) that copyright cannot subsist until it is “made”, that is, “reduced to” some material form or “embodied in” some physical thing and that there is a distinction between the physical form in which a work or other subject matter is made and the subject matter itself. In that case, the distinction maintained was between the subject matter of a cinematograph film as an aggregate of images and sounds and the subject matter of a computer program being a set of instructions. Justice Wilcox said that, like Burchett J, he was of the view that ss 10 and 24 of the Act were intended to cover new technologies, the emphasis being on the end product rather than the means adopted. ‘Nonetheless’, his Honour said at 17, ‘the definition will apply to any particular new technology only if the technology satisfies the words of the definition, liberally read’.

64 As to the meaning of “embodied”, Wilcox J pointed out that the images in the computer games which existed in the minds of the creators in the drawings and models being made were embodied in the computer program built into the video game machine so as to be capable by the use of the program of being shown as a moving picture (at 18). The form of the embodiment was not relevant. Further (at 20), the visual images that constituted the moving picture were taken to have been embodied in the computer program because the computer program was so treated in relation to those images as to be capable of reproducing them. His Honour accepted that capability was not enough and that it was important to note the requirement of s 24 that the article or thing ‘has been so treated in relation to those sounds or visual images’ that they are capable of being reproduced in the article or thing.

65 Justice Lindgren, with whom Lockhart J also agreed, pointed out that the copyright by virtue of s 10(1) subsists in an aggregate of the visual images embodied in an article or thing and also agreed that the word “embodied” should not be understood to refer only to forms of embodiment previously known. His Honour agreed with the principle that the definition does not require that the material cannot originate in digital form and that sounds or visual images may be created by means of writing a code and being emitted as the result of their embodiment in the article or thing, rather than being created and then recorded (at 23). Justice Lindgren did not construe s 24 or any other provision of the Copyright Act to require that the “aggregate of visual images” exist as an aggregate of visual images prior to embodiment. Rather, his Honour, said the aggregate of visual images referred to is the end product which, in Galaxy, comprises the moving pictures seen as the games are played from to time. Again, however, his Honour referred to the necessity to have an aggregate of visual images.

66 The requirement that there be an article or thing in which the cinematograph film, that is the visual images or sounds comprising it, is embodied, was also adopted by Emmett J in Australian Video Retailers Association v Warner Home Video Pty Ltd (2001) 114 FCR 324 per Emmett J (Australian Video) at [63]. His Honour said that ‘there must be a point at which an article or thing can be identified in which the visual images and sounds are embodied’. His Honour concluded at [65] that the ephemeral embodiment of tiny fractions of the visual images and sounds that comprise a cinematograph film or motion picture sequentially does not constitute the making of a copy of a motion picture or cinematograph film within the meaning of s 86(a) of the Act (the right to make a copy of the film), and that the fact that over a period of time tiny parts are sequentially stored in the RAM of the DVD player or personal computer does not mean that the film is embodied in such a device.

67 In Network Ten Pty Limited v TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited (2004) 218 CLR 273 (Network Ten), the majority of the High Court (McHugh ACJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ) noted that the Spicer Committee stressed the significance of the new head of the copyright protection at that time (at 285) and noted that the concept of copyright was one which extends protection against copying and performing in public any work insofar as it is reduced to a permanent form, but has not been extended to confer such protection in relation to a ‘mere spectacle or performance which is transitory of its very nature’, as opposed to a record or film of the spectacle which would enjoy its own copyright protection. This, as the plurality in the High Court set out, was consistent with the High Court’s rejection of a submission in Victoria Racing Park and Recreation Grounds Company Limited v Taylor (1937) 58 CLR 479 that a spectacle was ‘a quasi property’ which the law would protect.

68 Turning (at 289-290) to the “subject matter” of an incorporeal and transient nature, such as that involved in the technology of broadcasting, their Honours observed that while infringement will involve reference to the technology of broadcasting, this does not mean that ‘a television broadcast’ comprehends more than ‘any use, however fleeting, of a medium of communication’. Their Honours drew an analogy with ‘the words, figures and symbols which constitute a “literary work”, such as a novel, [which] are protected not for their intrinsic character as the means of communication to readers but because of what, taken together, they convey to the comprehension of the reader’. Their Honours drew a distinction between what was capable of perception as a separate image upon television screen and what was said to be accompanying sounds as the subject matter comprehended by the phrase “a television broadcast”; that is, the medium of transmission, not the message conveyed by its use (at 290). Again (at 289), their Honours drew a distinction between a medium that is ephemeral and a transmission that is captured. If any practical use is to be made of the signal that is broadcast, it is what is captured and if necessary translated that can and will be a faithful reproduction of what the broadcaster’s signal permits. Their Honours noted that s 87 of the Act identifies the nature of copyright in the television broadcast by reference to two methods by which what is transmitted can be captured and recorded in permanent or semi-permanent form.

69 Their Honours then turned to the notion and relevance of “fixation” in the context of cinematograph film (at 295). The distinction between the incorporeal broadcast and the corporeal film was relevant and is summarised at 296: ‘… the exclusive right in respect of the ephemeral activity of broadcasting is identified by reference to fixed embodiments’.

70 The plurality of the High Court drew a distinction between “sound recording” and “cinematograph film”, which do not overlap. Both, their Honours said, differ from “television” and “sound”, turning upon the notion of “fixation” and the existence of a material embodiment, as explained by s 24. Television broadcasting involves the two elements of visual images and sounds; the distinction is between the incorporeal, ephemeral broadcast and the corporeal film or sound recording. The right in a film extends to the right to make a copy and each category of infringing act will involve copying to produce a material embodiment (the copy) where there was an anterior material embodiment, the original film or sound recording.

71 In Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment (2005) 224 CLR 193 (Stevens), the High Court (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ) considered the circumstance where a substantial part of a computer program was temporarily stored in the RAM of a play station console while the game was played. The storage was temporary because the contents of the RAM were lost if power was disconnected and were displaced as new instructions were downloaded to the RAM. Their Honours turned to the definition of material form and observed that the definition was introduced to qualify what had been the general understanding that in copyright law a material form was one which could be perceived by the senses (at [66]). Their Honours observed (at [67]) that a material form, if a form of invisible storage, must be one from which the work or a substantial part of it ‘can be reproduced’. In answer to Sony’s submission that the data stored in the RAM could be said to reproduce the computer program stored in a PlayStation game in a material form, their Honours said at [68] that the data were not in a material or corporeal form but in a non-material incorporeal form, comprising essentially electronic impulses. Essentially, their Honours noted that material form is defined in the Act as ‘material form, in relation to a work or an adaption of a work, includes any form (whether visible or not) of storage from which the work or adaptation, or a substantial part of the work or adaptation, can be reproduced’. As their Honours noted at [69], the definition does not state a test for distinguishing between the circumstances of existence in a material form and non-existence.

72 Their Honours also referred to Australian Video where Emmett J said that ‘in the ordinary course temporary storage of a substantial part of the computer program in the RAM of a DVD player will not involve a reproduction of the computer program in a material form’. Their Honours noted that in the case of the temporary storage in RAM, the portion of the game code stored in the RAM could not be extracted and reproduced without developing hardware which would enable the process to be reversed.

73 I note in passing that in Stevens, the majority of the High Court noted at [77] a discussion by Finkelstein J in the Full Court below concerning United States authorities and the meaning of the word “fixed”, observing that his Honour acknowledged that the legislative scheme in the United States is different and that the authorities there have attracted a deal of criticism. Without investigating this matter further, it does indicate that the concept of fixation may, in different jurisdictions, not be straightforward.

74 Justice McHugh made some observations at [155] relevant to the present case. His Honour considered that the games code was “embodied” in the “article or thing” of the RAM, the CPU etc, because the code was downloaded or transmitted to each of them in a way that made the code capable, ‘with the aid of, the other article or thing of reproducing the code on a television screen’. However, McHugh J was of the view that the evidence did not establish that the “aggregate of the visual images” i.e. the aggregate of computer code, that is embodied in any of the console’s “article[s] or thing[s]” at any point of time was capable of being shown as a moving picture of being embodied in another article or thing by the use of which it can be so shown within the meaning of s 10 of the Act.

75 Justice Kirby noted that the evidence that ‘specific parts of the game code’ are transmitted to and embodied in the GPU does not extend to demonstrating that the GPU stores ‘the specific parts’ so as to embody an aggregate of specific parts of the computer code. Rather, the GPU moves the code on ‘into the video at RAM so that the GPU is free to work on the next section because of course this is a continuously changing environment’ (at [160]). Thus, his Honour observed, even though the GPU may reproduce a series of game code in the video RAM and even though the net result of all reproductions is to show a moving picture, the GPU does not embody, at any given time, an ‘aggregate of the visual images’. Thus at no point in the process at which the ‘game code is downloaded into the RAM and eventually transmitted to the television is a “cinematograph film” copied into any of the PlayStation console’s, articles or things’ (at [161]).

76 The majority accepted that RAM was a “form of invisible storage” comprising essentially electronic impulses. Accordingly, for want of evidence, it was not established that a substantial part of the film was embodied in the RAM or other things. Essentially, the High Court concluded that there had been no reproduction in a material form because the portion of the game code that was stored in the RAM could not be reproduced in the ordinary course.

Submissions

77 In view of the way in which the case was argued, it is worth repeating some of the matters as to the technology on which the experts agreed:

There has been a rapid change in television technology.

The ITVR Signal received by Seven at the relevant Olympic Games were electromotive forces that transmitted data to a receiving device, such as a television, which converts the data into television coverage, which is comprised of images and sounds.

There is no image or sound recorded in the signal; there is no physical form to an image or sound.

The ITV video and audio signals were combined to create the ITV Signal. The IR signal was not mixed to correspond to the ITV video signal but was embedded into the ITV signal by the host broadcaster at the Outside Broadcast Compound (OBC) to create the ITVR Signal. The OBC is defined in the Joint Experts’ Report to be a ‘secure area, usually in close proximity to the field of play, containing the host broadcaster facilities necessary to produce the ITV Coverage and IR Coverage of the events taking place on that field of play’). Data capable of conversion into ITV coverage and IR coverage was received via the ITVR Signal. These data could be decoded and converted into visual images and sounds by appropriate equipment such as a television.

The signals are capable of being converted by a television or other device into images and sounds. Visual images and sounds can be produced from the signal by use of a receiving device but images and sounds cannot be reproduced from the ITVR Signal.

The ITVR Signal was not suitable for broadcast purposes in its raw form.

The recordings made at the IBC were outside the series, that is, outside the chain of delivery to Seven.

78 The Commissioner relies on aspects of the technology that suggest permanence or stability, or enable the signal to be utilised. As to those aspects, the experts agreed:

The ITVR Signal can be disseminated, identified and controlled.

The ITVR Signals were encoded and combined digital signals and each is a complex, constantly changing aggregation of video, one or more audio and multiple data channels in a constant signal, accompanied by metadata; data are continuously streaming.

The video signals from the camera head were transmitted to a vision switcher at which point effects could be added by the producer and director, such as the Olympic logo and text.

The output of the vision switcher was the video component of the ITV signal for a field of play. While the video signal was not recorded or permanently stored within the vision switcher, it was sometimes temporarily held, in the sense of buffered, for approximately 1/25th of a second (equivalent to one frame) for synchronisation.

79 From the Commissioner’s submissions, he asserts and relies upon the following with respect to the Act:

“Embodiment” does not require that the physical “thing” must be tangible, and extends to an aggregate of visual sounds and images capable of being shown as a moving picture irrespective of the means of embodiment. The definition of “embodiment” is not exhaustive in “embodied” may have meanings beyond that definition.

“Copy”, as defined, does not require a physical form.

The Act contemplates that subject matter or works can exist in invisible form and be stored in an invisible form of storage e.g. s 21(6) of the Act which provides that a cinematograph film will be copied if it is converted into or from a digital or other electronic readable form.

It follows that any requirement for a physical form comes from the definition of “embodiment” and the Commissioner relies on Seven’s acceptance that something can be embodied without having a material form.

“Embodiment” really means that there must be some certainty about the subject matter in the sense that it can be identified and discerned and that the aggregate of visual images and sounds must be sufficiently permanent and stable to be identified and capable of being used to be shown as a moving picture.

Section 24 of the Act does not require permanence or any duration and thus the embodiment may be transitory.

Permanence does not equate to enduring.

There is a degree of permanence that enables the ITVR Signal to be put through the vision switcher and buffer and be split.

“Material form” is not limited to a visible form of storage of the work.

“Cinematograph film” is expressed in terms of the result achieved; it can be shown as a moving picture and the means employed is not a critical factor (Sega).

From the definition of “cinematograph film” requiring only capability of use, there is no requirement that the entirety of the film be embodied at one moment, as long as the aggregate is capable of being shown as a moving picture, by means of a receiving device being the viewer’s television set. In this case, the entirety of the images and sounds representing the field of play over a given time, that is the data, are sequentially transmitted by the signal and sequentially embodied in the buffer and in movement.

80 The ITVR Signal consists of visual images and sounds which are converted digitally by the camera and the camera creates the signal. Thus, the Commissioner submits, there is no difference between the visual images and sounds and the ITVR Signal. The Commissioner accepts that the digital data stream becomes the aggregate of sounds and images in the receiving device, the television set. However, he also says that the film comes into existence ‘when it’s embodied in the ITVR Signal’ capable of being shown by use of the receiving device. That is, the Commissioner says, the embodiment is the data stream and it comes into existence when the audio and visual data packets, which represent what the camera has captured, are converted into and transmitted in the ITVR Signal, the data stream.

81 Further, the Commissioner says, although the signal was not suitable for broadcasts in its “raw” form, it was the major ingredient in the broadcasts and the fact that Seven added commercials and commentary prior to transmission does not deprive it of copyright protection.

82 Turning to whether there was reproduction in a “material form” as required by s 31(1)(a)(i) of the Act, the Commissioner points out that in Stevens the High Court concluded that RAM may constitute a “material form”, where the crucial question was whether the computer program could be reproduced from the storage in the ordinary course without additional steps such as the aid of a machine or device. He submits that there is no requirement for reproduction that a copy actually be made in the physical sense, nor is there a requirement in the Act that the cinematograph film or the article or thing in which the work is initially embodied is in tangible or physical form. He says that the ITVR Signal can be form of storage in the same way that RAM is a form of storage and that the fact that visual images or sounds are not recorded or permanently stored in the copper cable that transmits the signal does not prevent the film they comprise being copyrightable subject matter. He submits that unless the copyright attaches to the ITVR Signal, there will be “an anomaly”.

83 The Commissioner says that the whole film does not need to considered but that the sequence of images put together by the host broadcaster are subject to copyright if there is a sufficient sequence of images to be shown as a moving picture, without a requirement for duration.

84 The Commissioner does not dispute that there is no copyright in the sounds and images themselves. He points out that if a recording is made, that will not protect the underlying subject matter of what was recorded. If the recording is broadcast, there will be a broadcast copyright but not in the sounds and images or the sequence of sounds and images themselves.

85 As Seven puts its case, the images and sounds were of the live action on the field of play and it is that it is not apt to describe a fraction of a second’s worth of an image as it is moving along the wire as an aggregate of visual images; the aggregate is never embodied, never given a material form, never given a body to: it is not a cinematograph film. It is not to the point, says Seven, that the images can be shown on the television, because there has been no embodiment of the images and sounds in the signal travelling along the wire at speed. The television may produce the images but it does not and cannot reproduce them. The Payment to the IOC is, as Seven describes it, for the access to the field of play and the distribution of signals over copper coaxial cables that Seven plugs into its system and transmits to Australia.

86 In essence, Seven’s submission is that it is not apposite to call an electromotive force carried down a wire as an article or “thing”. The copies that were made “on the side” were made when the ITVR Signal was “split”. These copies made by the host broadcaster were independent of the access to the ITVR Signal that Seven paid for and received.

87 The Commissioner submits that the aggregate of images and sounds transmitted by the signal are discernible and identifiable and can be reproduced. It can be recorded and the recording can be used to reproduce sounds and images. The Commissioner accepts that while the ITVR Signal is still in the hands of the host broadcasting organisation, before it reaches Seven, there is nothing to connect it to Australian law. However, he submits that the aggregate is recorded on at least two occasions before it is transmitted to Olympic broadcasters such as Seven, although he accepts that such recording is not “in series”, so that Seven does not in fact receive the stream that has passed through the recording device. He submits that the data that represent the images are also discernible and containable and undergo a number of transformations, conversions and temporary storage. He contends that the signal itself is discernible and controllable, that it is a physical thing but is encoded.

88 As characterised by the Commissioner, the signal is split on three occasions:

When the recording takes place in the OBC;

When another recording is made in the IBC; and

When it goes to the large number of Olympic broadcasters.

89 On each occasion, the signal is split, resulting in two identical data streams of which one is recorded and the other passed to the next stage. The Commissioner says that the data and the aggregate of sounds and images transmitted by the signal must be reproduced or copied “somehow” as there are multiple copies of the same thing, but accepts that there is no evidence about how this occurs. He relies on the fact that there are two identical streams when the stream is split and a recording is made and the other stream continues through to Seven.

90 The Commissioner also relies on the buffering process, where, in the process of transmission, a piece of data was stored in a buffer one piece at a time before further transmission. It would seem that this buffering took place before the video and audio signals were combined to create the ITV Signal, which then becomes the ITVR Signal after the audio embedder.

91 The Commissioner says that the fact that the signal can be diverted and transmitted means that there is some sort of permanence about the signal, enabling it to be discerned, identified and controlled; that is is not ‘so transitory and formless that it couldn’t be replicated into these two forms, two version or two streams containing identical data’. He submits that it must have been copied or reproduced ‘in some way’ in order to be transmitted in the second stream. I reiterate my observation that the Commissioner was unable to point to any evidence in support of these submissions.

92 He then submits that this means that the sounds and images must be reproduced, or copied or cloned, with the copying taking place in a recording device. The sounds and images cannot, the Commissioner accepts, be reproduced from the ITVR Signal but they can be “produced” from the signal with a receiving device. At that point, there would be copyright in the recording and so, the Commissioner says it follows that there must be copyright in the original stream, or else there is “an anomaly”. He emphasises that the end result is the important factor, not the means, citing Galaxy in support.

93 In summary, the Commissioner’s submission is that the data were not ‘so fleeting and transitory’ that they could not be reproduced in the recording device or subsequently recorded. The submission is somewhat confusing but the Commissioner seems to accept that it is after the embedder that the aggregate of sounds and images in embodied in the ITVR Signal, that this is prior to the first splitting of the signal and it is that signal which is capable, with the aid of a receiving device, to decode the data, to be shown as a moving picture with images and sounds.

94 The Commissioner describes the technology as constituting an aggregate embodied in the ITVR Signal, with sufficient certainty and stability to be an embodiment. The aggregate is, he submits, capable of being shown as a moving picture, capable of being embodied in a receiving device and capable of being reduced to a recording in the OBC. Accordingly, the Commissioner submits, it is taken to have been embodied in an article or thing for the purpose of s 24 of the Act. Thus, the Commissioner contends, the ITVR Signal has been treated in relation to the sounds and images within s 24. Seven says that the ITVR Signal cannot be a cinematograph film or a sound recording, as each is defined in s 10 of the Act in terms of “an aggregate” of sounds or images “embodied” in a record or article or thing. Seven reinforces this submission by reference to Re Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia v Faywin Investments Pty Limited (1990) 22 FCR 461 where Bowen CJ and French J expressed the view (and Hill J did not dissent on this aspect) that copyright in a cinematograph film is a right which arises in the completed work by virtue of ss 86 and 90 of the Act and is not composed of successive copyrights that arise in the partly completed work or parts thereof (at 471-472).

95 Seven’s premise is that the only copyright that comes into existence is that which exists in Seven’s broadcast, made with the benefit of the ITVR Signal, and that there is no copyright in a signal that is not embodied in an article or thing and cannot be reproduced or reduced to material form.

96 The Commissioner submits that the reasoning of McHugh J in Stevens applies by the following logic:

The film is transmitted by the ITVR Signal in a way that makes it capable, with the aid of a receiving device, of being transmitted to the public, reproduced on a television screen or recorded.