Blue Gentian LLC v Product Management Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1331

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 15 December 2014, the parties confer and file and serve proposed minutes of orders reflecting these reasons and including any further directions (if necessary) and in the event of disagreement, short written submissions in support of any separately proposed minutes of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 317 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | BLUE GENTIAN LLC First Applicant BRAND DEVELOPERS AUST PTY LTD (ACN 115 139 565) Second Applicant PRODUCT MANAGEMENT GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 131 987 034) Cross-Claimant

|

AND: | PRODUCT MANAGEMENT GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 131 987 034) Respondent BLUE GENTIAN LLC First Cross-Respondent BRAND DEVELOPERS AUST PTY LTD (ACN 115 139 565) Second Cross-Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MIDDLETON J |

DATE: | 8 DECEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This proceeding concerns a claim by the applicants, Blue Gentian LLC and Brand Developers Aust Pty Ltd (‘Brand Developers’) (unless otherwise relevant to distinguish, I shall refer to the applicants collectively as ‘Blue Gentian’) that the respondent Product Management Group Pty Ltd (‘PMG’) has infringed, or authorised the infringement of, Blue Gentian’s Australian innovation patents numbered 2012101797 (‘the First Patent’) and 2013100354 (‘the Length Patent’), both titled “Expandable and Contractible Hose” (collectively, ‘the Patents’).

2 Blue Gentian contended in particular that PMG has infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent.

3 PMG cross-claimed alleging the Patents are invalid and liable to be revoked.

4 The issues of infringement and validity were ordered to be heard and determined separately prior to any questions of pecuniary relief. There was also an issue as to whether Brand Developers has standing to bring infringement proceedings against PMG.

5 Blue Gentian relied on the evidence of Mr William Hunter, who is a qualified mechanical engineer who has worked in the area of product development and engineering design in relation to a wide range of products over the last 28 years, both within industry and as a consultant. Mr Hunter made three affidavits in this proceeding:

(a) the first, dated 25 July 2013, addressing whether there has been infringement of the First Patent (‘Mr Hunter’s First Affidavit’);

(b) the second, dated 3 September 2013, addressing whether there has been infringement of the Length Patent (‘Mr Hunter’s Second Affidavit’); and

(c) the third, dated 19 December 2013, responding to PMG’s evidence in chief on invalidity, and evidence in answer on infringement (‘Mr Hunter’s Third Affidavit’).

6 PMG relied on the evidence of Professor Steven Armfield, who is a Professor of Computational Fluid Dynamics and Head of the School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering at the University of Sydney. Professor Armfield made two affidavits in this proceeding:

(a) the first, dated 15 November 2013, responding to Mr Hunter’s First and Second Affidavits and addressing what is disclosed in the McDonald Patent (which I will later describe) (‘Professor Armfield’s First Affidavit’); and

(b) the second affidavit dated 23 January 2014 responding to Mr Hunter’s Third Affidavit (‘Professor Armfield’s Second Affidavit’).

7 PMG filed and served two affidavits (dated 14 November 2013 and 23 January 2014) of Mr Michael Elmore, a consultant, concerning whether the claims of the Patents are present in the McDonald Patent. However, PMG chose not to call Mr Elmore at the trial.

8 Lastly, there was a joint report of Professor Armfield and Messers Hunter and Elmore dated 28 January 2014 (‘the Joint Report’). In light of Mr Elmore not being called, Mr Elmore’s contribution to the Joint Report was not relied upon by the parties.

BACKGROUND

9 The First Patent and the Length Patent are related, have essentially the same text in the body of their specifications, and claim matter that is different in only a few respects. The Patents generally claim a garden hose that expands substantially in length (the First Patent) or two to six times (the Length Patent) when the water faucet it is coupled to is turned on, and which returns to its original length after use.

10 The elongation is achieved by reason of the garden hose having an elastic inner tube and an inelastic outer tube which are only attached at their ends such that, when the faucet is turned on, water pressure causes the inner tube to engorge, expanding in length and diameter to the point where it is constrained by the length and diameter of the inelastic outer tube. A “water flow restrictor” (or a “fluid flow restrictor” referred to in the claims of the First Patent) in, or attached to, the far end of the hose causes an additional increase in water pressure in the hose (compared to a hose with no such water flow restrictor).

11 When the faucet is turned off, the water drains from the garden hose, and the resulting decrease in water pressure allows the inner tube to contract. The outer tube reduces in length by catching on the rubbery surface of the inner tube and gathering tightly in folds along the length of the hose.

12 The advantages of garden hoses made in accordance with the Patents are that they have the ability to expand their length when in use without bursting, they are lightweight and easy and convenient to pack, transport and store, and do not kink in use.

13 PMG owns and operates a business supplying in Australia a garden hose marketed under and by reference to the name “Pocket Hose” (‘the Pocket Hose’). Blue Gentian alleges that PMG infringed the Patents because it imported, offered for sale or otherwise disposed of, sold or otherwise disposed of, and kept for the purpose of selling or otherwise disposing of, the Pocket Hose in Australia without the relevant licence or authority to do so, or authorised others to do so. Further, Blue Gentian alleges PMG infringed the Patents pursuant to s 117 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’).

14 PMG in turn allege that the Patents are invalid. Specifically:

(a) claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent are anticipated by US Patent 6,523,539, titled “Self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen mask” (‘the McDonald Patent’);

(b) each of the claims of each of the Patents do not involve an innovative step in light of McDonald;

(c) each of the claims of each of the Patents is not fairly based on the matter described in the respective specifications of those Patents;

(d) each of the claims of each of the Patents is not clear and succinct; and

(e) each of claim 2 and claims 3, 4 and 5 (to the extent that those claims are dependent on claim 2) of the First Patent is invalid in that the specification does not describe the invention fully within the meaning of s 40(2)(a) of the Act.

15 The final issue between the parties concerns whether Brand Developers held the exclusive licence to exploit the Patents, and can therefore bring infringement proceedings against PMG pursuant to s 120(1) of the Act, and whether the rights conferred on them by the licence agreement with Blue Gentian LLC were infringed, either directly, or pursuant to s 117 of the Act.

THE PATENTS

16 As noted above, the wording of each of the Patents is very similar and I will draw attention only to the differences which are relevant or notable.

The body of each specification

17 The field of the invention of the First Patent, which for all intents and purposes is identical to the Length Patent states:

The present invention relates to a hose for carrying fluid materials. In particular, it relates to a hose that automatically contracts to a contracted state when there is no pressurized fluid within the hose and automatically expands to an extended state when a pressurized fluid is introduced into the hose. In the contracted state the hose is relatively easy to store and easy to handle because of its relative short length and its relative light weight, and in the extended state the hose can be located to wherever the fluid is required. The hose is comprised of an elastic inner tube and a separate and distinct non-elastic outer tube positioned around the circumference of’ the inner tube and attached and connected to the inner tube only at both ends and is separated, unattached, unbonded and unconnected from the inner tube along the entire length of the hose between the first end and the second end.

18 The background section ([0002] to [0004]) describes problems encountered with garden hoses. The problems as identified relate to storage, such as the need for a reel or a container, and to tangling, kinking and the weight of the hose. The Patents state that it would be of great benefit to have a hose that is light in weight, expandable and contractible in length and kink-resistant.

19 Following a lengthy section listing numerous items of prior art hoses (the McDonald Patent is listed only in the Length Patent at [0026]), a summary of the invention starts at [0030] of the First Patent and [0031] of the Length Patent. Following the summary of the invention, the Patents set out a detailed description and several figures.

20 The invention is described as a hose comprising an inner tube inside an outer tube. The outer tube is secured to the inner tube only at the ends. The hose expands when connected to a pressurised water supply such as a water faucet. The hose can expand longitudinally, and in the case of the Length Patent, by up to about six times in length. On release of the pressurised water from the inner tube, the inner tube will contract. The inner tube could be made of rubber while the outer tube could be made of an inelastic relatively soft fabric like woven nylon, which gathers in folds about the inner tube when the inner tube is contracted.

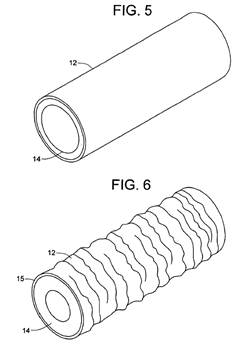

21 Figures 5 and 6 of the Patents show the invention in its unexpanded and in its expanded states:

22 In the unexpanded state, when there is no fluid pressure within the hose, the inner tube is in a relaxed condition. There are no forces being applied to expand or stretch it. In this state the outer tube is folded, compressed and tightly gathered around the outer circumference of the inner tube. When the hose is connected to a water supply and the supply is turned on, fluid pressure is applied, expanding the inner tube. The inner tube will expand laterally (also referred to as radially) and will also expand longitudinally (also referred to as axially), ie along the length of the hose. As the inner tube expands the wall thickness of the inner tube material is reduced. If the expansion is not constrained, the wall would become too thin and would likely rupture. The lateral expansion is therefore constrained by the diameter of the outer tube. The longitudinal expansion is similarly constrained by the length of the outer tube. As the water inflates the inner tube, the hose expands longitudinally and the folds of the outer tube unfurl until it is smooth (see figures 5 and 6 of the Patents, reproduced above). In this state the hose is ready to be used. The hose may also have a fluid flow restrictor, such as a nozzle or sprayer:

(a) attached to the second coupler, eg a trigger nozzle; and/or

(b) within the second coupler (which can be a narrower bore than the bore of the hose).

23 When water is allowed to flow within the hose the pressure inside will drop to some extent but there will be enough pressure remaining in the hose to keep it expanded in use.

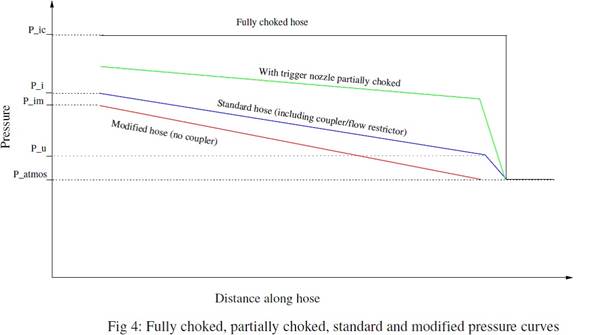

24 The Patents describe the various benefits of the invention, including:

(a) savings in weight, since it contracts without the need for metal components, and since a conventional 50 foot garden hose is said to weigh 12 lbs (5.4 kg) whereas the Patents describe a hose which “may only weigh less than 2 pounds” (0.9 kg);

(b) the hose automatically contracts when there is no pressure in the inner tube;

(c) the empty hose of the invention can be readily stored without kinking or becoming entangled as most conventional hoses do; and

(d) savings in time, because the hose contracts automatically from its expanded condition thus avoiding the need to carry or drag the hose, or the need for a hose reel, for storage.

The claims

25 The integers of the First Patent are as follows:

1.1 | A garden hose including: |

1.2 | a flexible elongated outer tube constructed from a fabric material having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow; |

1.3 | a flexible elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow, said inner tube being formed of an elastic material; |

1.4 | a first coupler secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes for coupling to a pressurized water faucet; |

1.5 | a second coupler secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes for discharging water; |

1.6 | the inner and outer tubes being unsecured to each other between first and second ends thereof; and |

1.7 | said second coupler also coupling said hose to a fluid flow restrictor or including a fluid flow restrictor so that the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said inner tube, |

1.8 | said increase in water pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby substantially increasing a length of said hose to an expanded condition and |

1.9 | said hose contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler. |

2.1 | The water hose of claim 1, wherein said inner tube and said outer tube are made from materials which will not kink when said inner and said outer tubes are in their contracted condition. |

3.1 | The water hose of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein said first coupler is a female coupler and said second coupler is a male coupler. |

4.1 | The water hose of any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the outer tube is unattached, unconnected, unbonded, and unsecured to the elastic inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube between the first end and the second end so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube when the hose expands and contracts. |

5.1 | The water hose of any one of claims 1 to 4, wherein the outer tube catches on a rubbery outer surface of the elastic inner tube and automatically becomes folded, compressed and tightly gathered around the outside circumference of the entire length of the contracted inner tube. |

26 The integers of the Length Patent are as follows:

1.1 | A garden hose including: |

1.2 | a flexible fabric material elongated outer tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow; |

1.3 | a flexible elastic material elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow; |

1.4 | a first coupler for connection to a water faucet, secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes, and |

1.5 | a second coupler for discharging water, secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes, |

1.6 | said outer and inner tubes being unattached, unconnected, unbonded, and unsecured to each other along their entire lengths between the first end and the second end so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube when the hose expands or contracts; and |

1.7 | a water flow restrictor connected to or being in the second coupler for increasing the water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said hose, |

1.8 | said increase in fluid pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby increasing a length of said hose by 2 to 6 times to an expanded condition and |

1.9 | said hose being contracted to a decreased length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler. |

2.1 | The garden hose of claim 1, wherein said garden hose is at least 10 feet long. |

3.1 | The garden hose of claim 1, wherein the hose increases in length by 4 to 6 times. |

4.1 | The garden hose of any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the first coupler is a female coupling for connection to a water faucet, and the second coupler is a male coupling for discharging water. |

5.1 | The garden hose of claim 1 wherein, when the extended elastic inner tube begins to contract from its expanded length, the unattached, unbonded, unconnected and unsecured fabric material outer tube catches on a rubbery outer surface of the inner tube material, causing the outer tube to automatically become randomly folded, compressed and tightly gathered around an outside circumference of the entire length of the contracted inner tube. |

INVALIDITY

27 There is no disagreement as to the nature of the invention claimed: the invention claimed is a garden hose.

28 Similarly, the law concerning the identification of the skilled addressee seems not in dispute: see the discussion in Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 177 ALR 231 at [70]–[72].

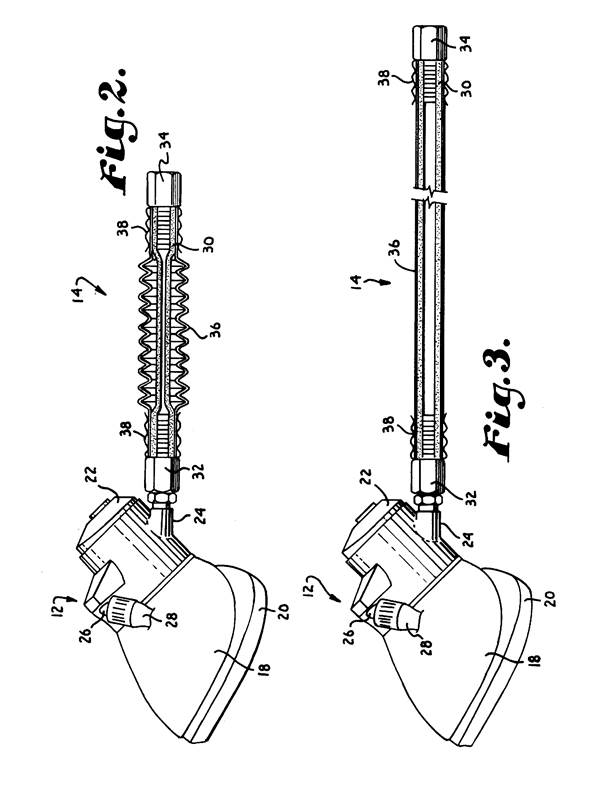

29 The field of the invention relates to:

… a hose that automatically contracts to a contracted state when there is no pressurized fluid within the hose and automatically expands to an extended state when a pressurized fluid is introduced into the hose.

30 The skilled addressee is a person with knowledge of the materials used for, and the design and manufacture of, hoses. He or she would also have an understanding of fluid mechanics. The skilled addressee may not necessarily have any specialised knowledge of garden hoses, since the general physical principles applying to garden hoses would similarly apply to all hoses. However, the skilled addressee would need to have a working knowledge of the design and manufacture of a garden hose, which is the subject matter of the claims.

31 Both Mr Hunter and Professor Armfield were witnesses who could assist the Court on the validity of the Patent and I would regard each as an appropriate skilled addressee.

32 The remaining issues concerning validity are construction, novelty and innovative step.

Construction

33 As I noted in Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (2013) 101 IPR 11 at [108], “the court should approach the task of patent construction with a generous measure of common sense”. The Full Court (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 at [67] helpfully summarised the relevant principles of construction:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law;

(ii) a specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction, and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date;

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning that the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification;

(v) the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter;

(vi) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning;

(vii) the court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time; and

(viii) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification.

(citations omitted)

34 I should also mention at this point the comments of the Full Court of this Court in Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44]:

… When determining the nature and extent of the monopoly claimed, the specification must be read as a whole. But as a whole it is made up of several parts which have different functions. The claims mark out the legal limits of the monopoly granted. The specification describes how to carry out the process claimed and the best method known to the patentee of doing that. Although the claims are construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim, by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification. If a claim is clear and unambiguous, it is not to be varied, qualified or made obscure by statements found in other parts of the document. It is legitimate, however, to refer to the rest of the specification to explain the background of the claims, to ascertain the meaning of technical terms and resolve ambiguities in the construction of the claims.

(citations omitted)

35 With these principles in mind, it is appropriate to look at the claims of the Patents and to discern the dispute between the parties in this regard.

36 As the integers of claim 1 are essentially common to the Patents, they can be construed simultaneously.

37 In the course of submissions and during the trial it became apparent that the key phrases and passages requiring construction were:

(a) a garden hose (integer 1.1 in the Patents);

(b) a coupler secured/connected to a water faucet (integer 1.4 of the Patents);

(c) a water/fluid flow restrictor causing an increase in pressure between the couplers (integer 1.7 of the Patents);

(d) said increase in water/fluid pressure (integer 1.8 of the Patents); and

(e) substantially increasing a length of said hose/increasing a length of said hose by two to six times (integer 1.8 of the Patents).

38 Of course, these phrases and passages must be considered in the context in which they appear. I should reiterate that the Patents are for a garden hose. A skilled addressee would know how a garden hose works and how it is used and this knowledge must be applied in the construction of the claims. The skilled addressee will know, as the first paragraph of the Patents indicates, that expansion is to occur when a pressurised fluid is introduced into the hose — for example, when a water tap is turned on and water enters the hose.

Garden hose

39 Whatever else is referred to in the specification, the claims all describe the invention as either a “garden hose” (claims 1 to 5 of the Length Patent, and claim 1 of the First Patent) or a “water hose” (claims 2 to 5 of the First Patent). It is clear that “water hose” is used synonymously with “garden hose” as it is described as a “water hose of claim 1” of the First Patent. The only thing capable of being the “water hose of claim 1” is the “garden hose” described in claim 1.

40 The proper construction of “garden hose” is a hose capable of being used as a garden hose and performing the functions one would ordinarily expect a garden hose to perform — for example, being attached to a water source and being suitable for watering a garden.

A coupler secured / connected to a water faucet

41 The full passages that include these terms are in integer 1.4 of claim 1 of the Patents and are as follows:

“a first coupler secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes for coupling to a pressurized water faucet” (the First Patent)

“a first coupler for connection to a water faucet, secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes” (the Length Patent)

42 Mr Hunter in his First Affidavit and in cross-examination gave evidence that a coupler is a common engineering term that refers to a component that connects two other components together. He said that it could also be made up of a number of components.

43 Professor Armfield in his First Affidavit described the hose claimed in the First Patent as having a coupler at the upstream end of the hose allowing the hose to be attached to a faucet.

44 The evidence is that a coupler is capable of being either a single component or an assembly of components that allows the hose to be attached to a faucet.

45 The claims are clear in that they speak of a coupler for coupling or connection to a water faucet. Thus, in the context of the invention, unless a component or assembly of components causes the hose to be coupled or connected to a water faucet, then it is not a coupler for our present purposes. It follows that if one was to take a singular component of the assembly, then it alone would not be a coupler as it requires other components to attach to a water faucet. On that basis, integer 1.4 should be construed as a single component or assembly of components acting in concert connecting or coupling the hose to a water faucet.

Water/fluid flow restrictor causing an increase in pressure between the couplers

46 Integer 1.7 of the Patents requires a fluid flow restrictor (the First Patent) or a water flow restrictor (the Length Patent):

which “creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said inner tube” (the First Patent); or

“for increasing the water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said hose” (the Length Patent); and

which is connected to, and/or incorporated within, the second coupler (the Length Patent).

47 I interpolate that I regard the word “creates” as meaning “causes” or “generates” — there was some debate about this, but in the context of this integer I consider the meaning to be clear. The debate was raised late in the proceedings by Professor Armfield as to the term “creates”, which he preferred to interpret as “maintains”. Professor Armfield made reference to the water pressure being created in Sydney by the Warragamba Dam which is up in the mountains, and not created by the faucet. Therefore, he considered there was just a modifying or maintaining of the water pressure in the hose. This is probably technically correct. However, it is not what is meant by the claim in the First Patent when it uses the word “creates”. In simple terms, when there is, for instance, a complete flow restrictor, the water pressure in the hose is caused or generated by, say, the use of a nozzle.

48 PMG submitted that a change in the geometry of the flow path introduced by the second coupling can also constitute a fluid flow restrictor with respect to the First Patent. The same principles apply in respect of the phrase “water flow restrictor” in the Length Patent claims. It also submitted that the integer is not capable of a sensible construction and is not fairly based on the disclosure in the specification. This is because the principles of fluid mechanics dictate that in a hose such as that described in the Patents, water pressure will either be reduced between the entry and exit points if the fluid exits at atmospheric pressure, or be constant if there is no fluid flow. Lastly, PMG submitted that the Patents do not explain how water pressure can be increased between the first and the second couplers. It submitted that the skilled addressee would understand that it is not possible to increase the pressure between these points.

49 Blue Gentian submitted that this integer means that a fluid flow restrictor must be present at the outlet end of the hose which creates an increase in the water pressure between the first and second couplers, compared with the pressure that would exist if there was no such fluid flow restrictor. It also submitted that “a ‘fluid flow restrictor’ or ‘water flow restrictor’ can only comprise a ‘change in the geometry of the flow path introduced by the second coupling’ if it also constitutes a reduction in the tube diameter that a person skilled in the art would consider provides a practical (ie, not insignificant) restriction to fluid flow”.

50 Blue Gentian submitted that the skilled addressee would consider whether the narrowing of the tube diameter caused by the flow restrictor is likely to have the practical effect of restricting the flow of the fluid in question and increasing the water pressure, and whether he or she would naturally describe it as a water or fluid flow restrictor.

51 Essentially there are two elements to the construction of this integer: the flow restrictor and the effect that it has on the water pressure within the hose.

52 It should be self-evident that the component coupled to the second downstream coupler, or the coupler itself, must restrict the flow of water. The specification is not explicit about what the flow restrictor must be and describes in [0055] of the Patents that “[a]nything that restricts the flow of fluid within the hose can be employed…”. Nozzles with “various amounts of restriction” and sprayers are offered as examples. The specification specifically contemplates that the flow restrictor may be an L-shaped nozzle with a pivoting on-off handle which operates an internal valve which permits, limits or stops the flow of water. This indicates that the specification contemplates a flow restrictor that permits various levels of flow restriction.

53 It follows that a water or fluid flow restrictor is any component coupled to or integrated within the second downstream coupler, or the downstream coupler itself, if it restricts the flow of fluid.

54 This should not be controversial. However, construction of the second element — that is, the function of the water or fluid flow restrictor — is more complex.

55 In general terms, the dispute is whether the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in pressure “from” the first coupler “to” the second coupler (PMG’s construction) or whether the increase relates to an increase in pressure as measured within the hose that is located between the first and second couplers as compared to a hose without a flow restrictor (Blue Gentian’s construction).

56 At this point it is helpful to refer to figure 4 in Appendix A of the Joint Report (reproduced below) which the experts agree is an accurate representation of the change in water pressure along the hose in various states; namely, the hose completely choked off, with a partially choked nozzle, with a standard hose (including coupler/flow restrictor), and with a modified hose (without a coupler).

57 It is undoubtedly correct and agreed between the experts, that when water is introduced into the hose there is a reduction in pressure from the upstream end of the hose to the point at which the water exits the hose. Therefore, if I was to accept PMG’s construction, the integer is a scientific nonsense. It is clear that there is no increase of pressure from the first coupler “to” the second coupler — in the three conditions of the hose where there is water flowing out of hose (that is, the hose with a partially choked nozzle, with a second coupler that restricts flow, and with no second coupler) the water pressure decreases along the length of the hose.

58 The two experts disagreed as to the interpretation to give to this integer. It is fair to say that Professor Armfield (who supported PMG’s construction) took a literal approach to the interpretative task accepting his approach led to a “scientific impossibility”.

59 However, during cross examination, Professor Armfield accepted that it was a “reasonable” use of language to describe the “increase” in pressure as shown in the difference between the red and blue lines in figure 4 of Appendix A to the Joint Report (reproduced above) as being the relevant increase created by the fluid flow restrictor.

60 In my view, Mr Hunter (who supported Blue Gentian’s construction) took a common sense approach to interpreting claim 1 in the context of it being a garden hose. Mr Hunter’s interpretation of the integer requires that the water flow restrictor causes an increase in water pressure between the two couplers, and it was this overall water pressure increase from the hose’s original condition (prior to attachment to a faucet) to its pressurised condition that had to “substantially increase” the length of the hose. I do not consider (as was submitted by PMG) that Mr Hunter changed his position as the proceeding developed. He adopted the same construction throughout, but later in his evidence simply responded to the various matters put by Professor Armfield.

61 In my view, the words in dispute, properly understood in the context of a garden hose, can be readily understood if read in this common sense way.

62 It can be seen from the above figure that while the pressure decreases along the length of the hose, it is still greater at the position of the second coupler if there was a flow restrictor than if there was not.

63 Furthermore, the distance between the couplers is the entirety of the hose. Another way of looking at “between said first coupler and said second coupler” would be to consider it as a way of describing the hose as a singular item. When looking at the above figure, generally, the water pressure within the hose with a flow restrictor is always greater than the water pressure without a flow restrictor. This construction accords with the words of the integer.

64 Presented with two constructions of an integer, where one is a scientific nonsense and the other a plausible construction, then provided the principles of construction are followed, the plausible construction should be favoured. I do not consider that by adopting Blue Gentian’s construction I am extending the patentee’s monopoly, or reading into the claims words by reference to the purpose of the monopoly. Nor am I correcting or amending the claims. With the benefit of the skilled addressee, I am interpreting the claims in a manner consistent with the wording, and in a manner which gives sense to the operation and function of a garden hose. A skilled addressee, having common general knowledge of a garden hose, its design and use, would in my view readily read claim 1 in the manner interpreted by Mr Hunter.

Said increase in water / fluid pressure

65 The next term requiring construction is “said increase in water / fluid pressure”. Integer 1.8 of the First Patent describes:

said increase in water pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby substantially increasing a length of said hose to an expanded condition

(emphasis added)

66 Integer 1.8 of the Length Patent reads in similar terms however speaks of “fluid” pressure, rather than water pressure.

67 Construction of “said increase in water pressure” turns on whether the word “said” is to be as construed as referring to the increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within inner tube created by the fluid flow restrictor alone (PMG’s construction); or whether the increase in pressure is created by the introduction of pressurised water from the faucet — that is, not limited to that increase caused by the fluid flow restrictor (Blue Gentian’s construction).

68 PMG’s construction refers back to the previous use of the words “increase in water pressure” as defined and limited by the language of the immediately preceding integer 1.7, so that the relevant “increase in water pressure” is limited to that caused by the relevant fluid flow restrictor.

69 In contrast, Blue Gentian’s construction, the word “said” refers back to the words “increase in water pressure” more generally, being the increase that results from the first coupler being connected to the “pressurized water faucet” which has been opened.

70 Looking to the evidence of the experts, Professor Armfield’s evidence in chief was that where water flows through the hose, the expansion of the hose is caused principally by the effect of “frictional losses” within the inner tube (that is, the friction between the fluid and the wall of the hose) with the flow restrictor only making a minor contribution to the expansion of the hose.

71 Mr Hunter’s evidence on the other hand was generally that it was upon the application of pressurised water from a faucet, that the frictional loss or the flow restrictor, or a combination of both, caused the lateral and longitudinal expansion of the hose.

72 I found Mr Hunter’s evidence persuasive, which evidence was confirmed by some of the evidence of Professor Armfield.

73 In cross-examination, Professor Armfield accepted that the skilled addressee would consider the effect on the hose of the overall increase in water pressure, and not just that which is contributed to by a fluid flow restrictor. He accepted that the words “expanded condition” in the claim refer to the hose once it has been expanded by having pressurised water introduced into it. He accepted that, for a dynamic system (that is, with water flowing) the expansion will be caused by both the fluid flow restrictor and the frictional losses caused by the flow of water through the hose itself, and that the skilled addressee would be aware of this. He also accepted that the final words of the claim, “said hose contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler” referred to the overall decrease in pressure as the pressure inside the hose returned to atmospheric pressure and this is the corollary of the “substantial increase” that resulted in the “expanded condition” of the hose from its initial state where the internal pressure started as atmospheric pressure.

74 In re-examination, Professor Armfield said that the decrease in water pressure mentioned in integer 1.9 is referring to the same water pressure as the phrase “the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler”—that is, the entire water pressure increase or decrease between the couplers, not just that caused by the fluid flow restrictor.

75 It is to be noted that the percentage contribution of the fluid flow restrictor to the overall increase in water pressure can vary, according to the type of fluid flow restrictor and degree of restriction it provides. Blue Gentian’s construction permits this whereas PMG’s more literal construction requires the measurement of the contribution to expansion made by a fluid flow restrictor, and the issue further arises as to what usage or flow conditions are present. This added complexity is not, in my opinion, necessary to be read into the integer.

76 Lastly, I think this argument concerning the construction of the integer is slightly distracting. The claims are for the assembly of a garden hose. There must be a fluid flow restrictor as required by the claim — being in the second coupler, and/or connected to the second coupler and it must be causative of an increase in water pressure in the hose.

77 The skilled addressee would recognise that, when there are substantial flows of water through the hose, the frictional losses within the inner tube of the hose are an additional significant cause of the increase in water pressure within the hose.

78 Thus, I construe “said increase in water / fluid pressure” to be the result of frictional loss and the presence of a flow restrictor. In other words, the phrase is not limited to the increase caused by the fluid flow restrictor.

Remaining Claims

79 Though not in dispute in relation to construction, I will briefly note claims 2 to 5 of the Patents.

80 With respect to the First Patent:

(a) Claim 2 teaches that the inner and outer tubes of the hose as described in claim 1 be made from materials that do not ‘kink’ when the hose is in the contracted state;

(b) Claim 3 teaches that the first and second couplers of the hose described in claims 1 or 2 are female and male couplers respectively;

(c) Claim 4 teaches that the outer tube of the hose described in claims 1, 2 or 3 is unattached, unconnected, unbonded and unsecured to the elastic inner tube along the length of the inner tube between the ends of the hose; and

(d) Claim 5 teaches that the hose described in claims 1, 2, 3, or 4 is one where the outer tube catches on the surface of the inner tube and automatically folds, compresses and tightly gathers around the contracted inner tube.

81 With respect to the Length Patent:

(a) Claim 2 teaches that the hose described in claim 1 is at least 10 feet long;

(b) Claim 3 teaches that the hose of claim 1 increases in length four to six times;

(c) Claim 4 teaches that the hose described in claims 1, 2 or 3 is one where the first coupler is a female coupler for connecting to a water faucet, and the second coupler is male coupler for discharging water; and

(d) Claim 5 is for current purposes the same as claim 4 and 5 of the First Patent.

Novelty

82 I now turn to novelty and the McDonald Patent.

83 Section 18(1A)(b)(i) of the Act relevantly provides that an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of an innovation patent if (among other things) the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim, is novel.

84 Section 7(1) of the Act provides, relevantly, that an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of any one of certain kinds of prior art information.

85 The basic test for novelty in Australia is the “reverse infringement” test enunciated by Aickin J in Meyers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd (1977) 137 CLR 228 at 235. This requires the prior art information to disclose all the essential integers of the claimed invention. See also Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 217 FCR 238, at [127].

86 The reverse infringement test is not applied by simply asking whether something within the prior art document would, if carried out after the grant of the patent, infringe the invention as claimed. In Flour Oxidizing Company Ltd v Carr & Co Ltd [1908] 25 RPC 428, Parker J (at 457) observed:

… where the question is solely a question of prior publication, it is not, in my opinion, enough to prove that an apparatus described in an earlier Specification could have been used to produce this or that result. It must also be shown that the Specification contains clear and unmistakable directions so to use it.

87 Once the clear and unmistakable direction is found, then, as stated in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 312 ALR 1 at [302]:

Sufficiency of disclosure is a cardinal anterior requirement in the analysis of whether a prior art document anticipates a claimed invention. It is only after the stage of assessing the sufficiency of disclosure — which involves a determination about whether a prior document has “planted the flag” as opposed to having provided merely “a signpost, however clear, upon the road” or, perhaps, something less — that the notion of reverse infringement comes into play as the final and resolving step of the required analysis. It is not the first step of the required analysis; nor is it the only step.

88 The terms in the alleged anticipatory document should be read through the eyes of the skilled addressee in the context in which these terms appear. It is a question of the disclosure to the skilled reader. As Bennett J in Zetco Pty Ltd v Austworld Commodities Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 848 (‘Zetco’) at [93] stated:

Such a disclosure may be explicit or, in certain circumstances, may amount to a sufficient disclosure of each integer to a skilled worker even though not explicit (H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151; Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 91 ALR 513). This may occur where, for example, the prior art information is a publication which does not specify an integer but the skilled reader would understand that integer to be present in the subject matter described. The same applies to what is disclosed to the person of skill in the art by a prior product. If the prior art does not expressly specify each and every essential integer of the claimed invention, the evidence must clearly establish that, to the skilled reader, each and every essential integer is included in that prior art.

89 The terms are to be given “the meaning which the person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification”: see eg H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151 at 179, [118] per Bennett J.

90 In addition, it is not sufficient for there to be implicit disclosure just because the skilled addressee would think that a feature not disclosed by the publication itself, may be a good idea: see Ramset Fasteners (Australia) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building systems Pty Ltd (1999) 164 ALR 239 at [23]-[25].

The McDonald Patent

91 The McDonald Patent is entitled “Self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen mask”.

92 The abstract of the McDonald Patent conveniently summarises the invention:

A supplemental gas assembly such as used for aircraft crews is provided which includes a mask adapted to fit over at least the nose and mouth of a wearer, together with a flexible, self-elongating hose assembly and a stowage box for receiving the mask and hose assembly; the assembly is designed so that when the mask is pulled from the box, pressurized gas passing through the hose assembly serves to inflate and axially expand the assembly to a deployed length greater than the relaxed length thereof. The assembly preferably includes an inflatable elastomeric inner tube together with an exterior sheath of woven or braided material which restricts radial expansion of the tube while permitting axial expansion thereof. In preferred forms, the deployed length of the assembly is up to three times greater than the relaxed length thereof.

93 The McDonald Patent contains three drawings of the invention, figures 2 and 3 being relevant for my purposes:

94 The McDonald Patent discloses a self-elongating hose assembly, which includes an inner, resilient, expandable inner tube secured at each end to an outer fabric sheath. The hose assembly is then connected to a mask at one end and threaded on to a gas fitting at the other. When pressurised gas is delivered into the hose, the inner tube expands longitudinally. The outer sheath inhibits the radial expansion and longitudinal elongation of the inner tube.

95 The claims of the McDonald Patent are as follows:

1. In a supplemental gas assembly including a mask adapted to fit over at least the nose and mouth of a wearer, a flexible hose operably coupled with said mask and source of supplemental gas and having a relaxed length, and a stowage box adapted to receive at least a portion of said mask and hose when the latter are not in use by said wearer, the improvement which comprises using as said hose a length-expandable hose which, when said wearer grasps said mask and pulls the mask from said box, will inflate and axially expand to a deployed length greater than said relaxed length, said length-expandable hose comprising an inflatable inner tube and an exterior sheath which restricts the radial expansion of said inner tube while allowing said axial expansion during said hose inflation.

2. The assembly of claim 1, said inner tube formed of an elastomeric material, said sheath being a woven or braided material.

3. The assembly of claim 2, said inner tube formed of an elastomeric material.

4. The assembly of claim 1, said deployed length being at least about 1.5 times said relaxed length.

5. The assembly of claim 4, said deployed length being greater than about 2 times said relaxed length.

6. A supplemental gas mask assembly comprising:

a mask body adapted to fit over at least the nose and mouth of a wearer;

an elongated hose operably coupled with said mask for supplying supplemental gas to the mask body, and having a relaxed length.

said hose being a length-expandable hose which, when supplemental gas under pressure is directed through the hose, will inflate and expand in an axial direction to a deployed length greater than said relaxed length, said length-expandable hose comprising an inflatable inner tube and an exterior sheath which restricts the radial expansion of said inner tube while allowing said axial expansion during said hose inflation.

7. The assembly of claim 6, said inner tube formed of an elastomeric material, said sheath being a woven or braided material.

8. The assembly of claim 7, said inner tube formed of a material selected from the group consisting of silicone and nitrile materials.

9. The assembly of claim 6, said deployed length being at least about 1.5 times said relaxed length.

10. The assembly of claim 9, said deployed length being greater than about 2 times said relaxed length.

11. The assembly of claim 6, the end of said hose opposite said mask body adapted for connection to a supplemental gas source.

96 It now turns to me to decide whether the McDonald Patent gives clear and unmistakeable disclosure to the skilled addressee of all the essential features of the “garden hose” Patents’ claims. PMG contends that on the basis of the disclosure in the McDonald Patent, the alleged inventions in claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent are not novel.

Claim 1 of the First Patent

97 With respect to claim 1 of the First Patent, PMG contends that the McDonald Patent discloses a hose which:

(a) can be used as “a garden hose” (integer 1.1);

(b) has a flexible elongated outer tube constructed from a fabric material, and a flexible elongated inner tube formed of an elastic material (integers 1.2 and 1.3);

(c) has “a first coupler secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes for coupling to a pressurized water faucet”, and “a second coupler secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes for discharging water” (integers 1.4 and 1.5);

(d) has “the inner and outer tubes” which are “unsecured to each other between first and second ends thereof” (integer 1.6) and;

(e) the second coupler includes a fluid flow restrictor which creates an increase in water pressure expanding the inner tube longitudinally and laterally, substantially increasing the length of the hose, and then contracting when there is a decrease in water pressure (integers 1.7–1.9).

Integer 1.1

98 Integer 1.1 in the First Patent calls for a garden hose. The invention in the McDonald Patent is plainly not a garden hose. However, PMG contends that the mechanics and behaviour of the McDonald Patent’s invention and the invention disclosed in the First Patent is essentially the same regardless of the fluid introduced into the hose. Indeed, the First Patent explicitly states that gases can be used in the hose.

99 The McDonald Patent discloses an invention containing a hose with a mask attached whereas the First Patent discloses the assembly hose alone. For the invention disclosed in the McDonald Patent to be used as a garden hose, the mask would have to be removed as conceded by Professor Armfield and as suggested in Mr Hunter’s Third Affidavit.

100 It is clear that this integer (the garden hose) is not disclosed in the McDonald Patent as the experts agree. This is enough to dispose of the claim of anticipation. The McDonald Patent describes an apparatus having a hose and a mask which would not be suitable for use as a garden hose. As Mr Hunter then said:

… I don’t make the leap that you can just automatically infer that by reading McDonald, you can get rid of the mask and have something that works for water in a garden.

Integers 1.2 and 1.3

101 Integers 1.2 and 1.3 of the First Patent describe the inner and outer tubes of the garden hose. The dimensions of the tubes are not disclosed in the First Patent, and nor are they disclosed in the McDonald Patent. The experts agree, and so do I, that these integers are disclosed in the McDonald Patent.

Integers 1.4 and 1.5

102 Integer 1.4 of the First Patent requires a first coupler secured to the first end of the inner and outer tubes for coupling to a pressurised water faucet. Integer 1.5 of the First Patent similarly requires a second coupler secured to the second end of the inner and outer tubes for discharging water.

103 Mr Hunter gave evidence in chief that the first coupler, described in the McDonald Patent as being a threaded hose fitting suitable for being threaded on to a box-mounted gas fitting, would not attach to a domestic pressurised water faucet. He conceded in cross-examination that the first coupler is performing the function of coupling the McDonald Patent hose to a pressurised fluid source. I do not think this concession detracts from his evidence in chief as the First Patent does not call for a coupler for coupling to any pressurised fluid source, but rather a water faucet. The thrust of Mr Hunter’s evidence is that the couplers disclosed in the McDonald Patent would require adaptors to perform in the same way as the couplers disclosed in the First Patent.

104 Professor Armfield accepted in his Second Affidavit that the couplers would need to be modified or attached to appropriate adaptors for the hose claimed in the McDonald Patent to function as a garden hose. In cross examination, while he stated that it might be possible that the first coupler would be able to connect to a water faucet without modifications, he later accepted that it was unlikely, and that it was likely that the couplers would need to be modified to fit to a water faucet.

105 With respect to the second coupler, as I have already noted above, the experts agree that the mask is not suited to discharging water.

106 Blue Gentian submitted that the Court cannot ignore the mask and compare the McDonald Patent invention with the claims of the First Patent as McDonald does not give clear and unmistakeable directions to make the hose without the mask attached.

107 I agree. Both expert witnesses gave evidence that if the mask was removed, and appropriate adaptors were attached to the couplers, the hose disclosed in the McDonald Patent could be used as a garden hose. However, this would require modifications (to make the McDonald Patent hose suitable for coupling to a water faucet and discharging water) which go beyond any express or implied disclosure. Integers 1.4 and 1.5 are thus not anticipated.

Integer 1.6

108 Integer 1.6 requires that the inner and outer tubes be unsecured to each other between the first and second couplers. The experts agree, and so do I, that the McDonald Patent anticipates this integer.

Integers 1.7 to 1.9

109 The essence of PMG’s submission is that the presence of a downstream coupler in the McDonald Patent hose, is sufficient to disclose to the skilled addressee that which is taught in integers 1.7 to 1.9; that is, the presence of a flow restrictor coupled to the second coupler causes an increase in pressure resulting in the expansion and elongation of the hose, and contraction when there is a decrease in pressure.

110 Blue Gentian’s submission in this regard is that the McDonald Patent does not disclose a downstream flow restrictor, and furthermore, it does not disclose an increase or decrease in water pressure.

111 As indicated above, there may be cases where prior art information does not specify an integer, but the skilled reader would understand that integer to be present: Zetco at [93].

112 Analysis is required, as to whether the skilled addressee would recognise that the McDonald Patent would include these integers, despite no such express disclosure.

113 The first element of integer 1.7 is the presence of a flow restrictor coupled (or integrated) into the second coupler.

114 Professor Armfield noted that the McDonald Patent hose fitting filling the role of downstream coupler will cause a change in geometry in the flow path which will unavoidably cause a pressure loss, and that the attachment of a fluid distribution device (such as the oxygen mask) will provide some of the intended effect of the fluid flow restrictor described in the First Patent. In cross-examination, Mr Hunter accepted that the figures in McDonald “quite likely” showed a tailpiece or extension of the threaded hose fitting, and that the tailpiece had a bore or inner tube which must be narrower than the internal dimensions of the expanded inner tube. Mr Hunter also conceded that the mask assembly could act as a flow restrictor. This would, in itself, anticipate integer 1.7.

115 It may then follow that because there is a flow restrictor coupled to or integrated into the second coupler, that integers 1.8 and 1.9 would be anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

116 However, the expansion and contraction of the hose is inextricably linked to the materials used and physical conditions of the introduction of gas or water into the hoses.

117 Integer 1.8 teaches that the increase in water pressure caused by the introduction of pressurised water to the assembly and the downstream fluid flow restrictor causes the hose to expand laterally and longitudinally substantially increasing the length of hose. Integer 1.9 teaches that the hose will contract when there is a reduction in water pressure between the couplers. Integers 1.8 and 1.9 are corollaries of one another, and should be assessed concurrently.

118 Professor Armfield stated that a skilled addressee would expect that the flow rate of water introduced into a garden hose would be around 20 litres per minute, whereas a skilled addressee would expect the flow rate of oxygen to be substantially lower. In addition, he noted that the density of oxygen is approximately one one-thousandth that of water. Mr Hunter’s evidence was similar. He noted that garden hoses typically encounter flow rates from water faucets significantly higher than that of a gas mask delivering oxygen, and they must also be able to accommodate a wide variation in pressures across different households, whilst the McDonald Patent hose would ordinarily encounter constant gas pressure. Professor Armfield accepted that the McDonald Patent did not say anything about the pressure that the hose could withstand.

119 It is unclear whether a hose made in accordance with the McDonald Patent would be capable of resisting the pressures typically experienced in a domestic water supply. Mr Hunter in his Third Affidavit explained that the outer tube of the invention disclosed in the Patents constrains the longitudinal (axial) elongation and the lateral (radial) expansion of the inner tube when pressurised water is introduced. However, the McDonald Patent teaches that the outer sheath inhibits or restricts only the radial expansion but it “permits axial elongation thereof”. There is no disclosure limiting the axial elongation of the McDonald Patent hose. Further, the McDonald Patent teaches that the outer sheath has a length two to three times the length of the inner tube, whereas the length of the deployed assembly is at least 1.5 times the relaxed length. That is the outer sheath can unfurl more than the ideal length of the deployed assembly when pressurised gas is introduced. This further indicates that the outer sheath does not necessarily constrain the elongation of the inner tube in the McDonald hose.

120 The dimensions of the hose in either the First Patent or the McDonald Patent are not disclosed in the claims. Mr Hunter in his Third Affidavit said that the hose as described in the McDonald Patent would be too short to have practical utility as a “garden hose”. Professor Armfield gave evidence that the internal diameter of a standard tube for delivering oxygen would be only millimetres wide and, though he speculated (based on figure 3 in the McDonald Patent) that the inner tube in the McDonald Patent could be 10 millimetres wide, he agreed there was no express disclosure of its diameter. He agreed that, if the tube was only millimetres wide, it would not be suitable for use as a garden hose.

121 He also suggested that the hose described in the McDonald Patent would be about 75 cm long and accepted that even if it was double that length, (ie 1.5 m long), it would plainly not be suitable for use as a garden hose unless (as he suggested) one connects a number of such hoses end to end. He accepted that that involved such a scenario not taught by the McDonald Patent.

122 The experts agree that the underlying scientific principles concerning fluid dynamics are the same and apply identically whether concerning the First Patent or the McDonald Patent. However, the inescapable reality is that the dimensions of each hose and the materials of which they are comprised are individually appropriate for the particular substances intended to be introduced into them; that is water for the hose disclosed in the First Patent, and oxygen in the McDonald Patent hose.

123 While it is true that water may be introduced into the McDonald Patent hose, the evidence is, that it would not have the requisite physical dimensions be a functional garden hose. Further, the inner hose described in the McDonald Patent is not necessarily constrained by the outer sheath which means that if pressurised water was introduced, it may expand to bursting point. Mr Hunter also observed that in any event no water, or water pressure, is disclosed in the McDonald Patent. In my opinion, it follows then that the McDonald Patent does not anticipate integers 1.8 or 1.9.

Claim 2 of the First Patent

124 Claim 2 of the First Patent teaches that the hose will not kink when contracted.

125 The McDonald Patent does not explicitly require that the hose not kink when in the contracted condition. It may be the case that it is important for the hose to be kink-resistant when in the expanded condition, because such a condition likely occurs in an aircraft emergency. However, this integer teaches that the hose not kink in the contracted condition. In any event, there is no disclosure of kink-resistance in the McDonald Patent. Consequently, claim 2 is not anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Claim 4 of the First Patent

126 Claim 4 of the First Patent discloses an assembly where the outer tube is unconnected and unsecured to the elastic inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube during expansion and contraction.

127 The experts agree, and so do I, that this assembly (when considered as an independent claim not dependent on claims 1 to 3) is anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Claim 5 of the First Patent

128 Claim 5 of the First Patent teaches that the outer tube catches on the surface of the inner tube and automatically becomes folded, compressed and tightly gathered around the length of the contracted inner tube.

129 The Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiment in the McDonald Patent states that “[a]s best seen in FIG. 2 in the relaxed condition of the assembly 14, the sheath 36 is in a gathered or shirred condition along the length of the unexpanded tube.”

130 Professor Armfield’s evidence was that claim 5 was anticipated because the McDonald Patent uses the words “gathered” and “shirred” and he speculated that it would be impossible the prevent the outer sheath from coming into contact with the inner tube in the relaxed sheath.

131 Mr Hunter did not consider that the integer was anticipated by the McDonald Patent because figure 2 of that patent showed a clearance between the inner and outer tubes in the contracted condition, and further the McDonald Patent did not disclose the outer tube catching on the surface of the inner tube in its contracted state.

132 The experts were not provided with the invention disclosed in the McDonald Patent to test this claim.

133 The disclosure in the McDonald Patent that the outer tube is gathered or shirred along the length of the unexpanded tube does not give a clear and unmistakeable direction that the outer sheath would catch on the inner tube.

134 Consequently, claim 5 of the First Patent is not anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Claim 1 of the Length Patent

135 For my present purpose, claim 1 of the First Patent is synonymous with claim 1 of the Length Patent, and I adopt my analysis above, in that regard. As such, claim 1 is not anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Claim 2 of the Length Patent

136 Claim 2 teaches that the hose be at least 10 feet long. The McDonald Patent does not disclose the length of the hose. The experts agree that claim 2, when considered as an independent claim is not disclosed in the McDonald Patent.

137 Whilst it may be possible to make a McDonald hose of any length, I do not consider there is any evidence of express or implied disclosure whereby the skilled addressee would consider making a hose at least 10 feet long on the basis of what is disclosed in the McDonald Patent.

138 As such, claim 2 of the Length Patent is not anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Claim 5 of the Length Patent

139 For my present purpose, claim 5 of the First Patent is synonymous with claim 5 of the Length Patent, and I adopt my analysis above, in that regard.

140 As such, claim 5 of the Length Patent is not anticipated by the McDonald Patent.

Conclusion in relation to novelty

141 The McDonald Patent does not anticipate the claims.

Innovative step

142 Section 18(1A)(b)(ii) of the Act relevantly provides that an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim, involves an innovative step.

143 Pursuant to section 7(4) of the Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an innovative step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would, to a person skilled in the relevant art, in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim, only vary from the prior art information in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

144 It is important to correctly identify what is being compared when assessing innovative step. On the one hand, there is the invention “as claimed”, which is not to be confused with the “advance in the art” as identified by reference to common general knowledge, nor the “key idea” of the invention, nor how the patented invention “works as an invention”: Dura-Post (Aust) Pty Ltd v Delnorth Pty Ltd (2007) 177 FCR 239 (‘Dura-Post’) at [94]–[97] per Perram J, and at [72]–[76] per Stone and Kenny JJ.

145 What the invention “as claimed” must be compared with is the relevant disclosure forming part of the prior art base (s 7(4)). As Stone and Kenny JJ explained in Dura-Post at [78]–[79] the test for lack of innovative step is a “modified novelty test”:

[79] The adoption of a modified novelty test deriving from Griffin v Isaacs (1938) 1B IPR 619 emphasises that s 7(4) requires a narrow comparison between the invention as claimed and the relevant prior disclosure, having regard to the fact that the threshold for an innovation patent is intended to be lower than for a standard patent. This latter matter finds confirmation in the Revised Explanatory Memorandum … In substance, s 7(4) deems an invention as claimed to involve an innovative step unless the invention does not differ from the relevant prior disclosure in a way that makes a substantial contribution to the working of the invention as claimed — in the sense of the device or process the subject of each claim. This is a factual inquiry. The assessment is, of course, from the perspective of a person skilled in the art, having regard to the relevant common general knowledge.

146 That in turn requires an assessment of what the McDonald Patent discloses.

147 It is to be remembered then that the threshold for an innovation patent is intended to be lower than for a standard patent.

148 For example, Gyles J in Dura-Post at first instance observed that a roadside post involved an innovative step over the “SupaFlex plastic guide post” simply because the materials were sufficiently different notwithstanding that they each had the same objective: Delnorth Pty Ltd v Dura-Post (Aust) Pty Ltd (2008) 78 IPR 463 at [63]. His Honour stated at [63] that:

As I have endeavoured to explain, the question is not whether flexible sheet steel is better than flexible PVC – it is certainly different. It cannot be seriously argued that the material sheet spring steel does not make a substantial contribution to the working of the roadside post claimed in each claim.

149 That is, even though the materials were used for the same purpose or had the same key idea, the fact that the materials were different was enough.

150 Furthermore, Yates J in Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (No 2) (2013) 101 IPR 496 (‘Vehicle Monitoring Systems’) at [246] held:

There was an additional aspect to this challenge. There was a dispute between the parties as to whether Walker discloses an apparatus adapted for subterraneous operation below the pavement surface of a parking space. In my view, Walker does not make that disclosure. The respondent submitted that, if no such disclosure is made, then the fact that the claimed apparatus is so adapted makes no substantial contribution to the way it works. For the reasons I have given when dealing with Tetsuya, I am satisfied that a substantial contribution is made by this adaptation. In any event, claim 5 is dependent on claims 2 and 4, each of which claims an apparatus with features that do make a substantial contribution to the way the invention works.

(emphasis added)

151 As to what his Honour said about Tetsuya (a prior art document) at [234]–[235]:

[234] As I have noted, the second aspect of the respondent’s challenge (relating to claim 5) is based on the disclosure in Tetsuya of a magnetic field sensor. The respondent submitted that, if a magnetic field sensor were to be used in the vehicle detector disclosed in Tetsuya, that detector could be installed subterraneously. It then submitted that such a detector, if deployed subterraneously, would not operate differently from the apparatus claimed in claim 5 of the patent.

[235] This reasoning confuses the magnetic field sensor (a component of the apparatus that is claimed) with the apparatus itself and, in so doing, ignores the question whether the adaptation of the claimed apparatus for subterraneous operation makes a substantial contribution to the working of that embodiment. In my view, it does. As the complete specification makes clear, subterraneous installation conceals the apparatus and makes it less susceptible to vandalism. On any view, this feature is a contribution to the working of the invention that is real and of substance.

(emphasis added)

152 Further, it is important to recall one more matter. Common general knowledge is the “background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade in considering the making of new products, or the making of improvements in old, and it must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge”: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 292 per Aickin J. Nevertheless, whilst common general knowledge has a role to play, it does not play the same role as when assessing obviousness in the context of an inquiry about the presence or absence of an innovative step. In the assessment of innovative step, “it is of no significance that the feature or features that distinguish the invention as claimed over the prior art represents or represent an obvious deployment of the common general knowledge if that feature or those features nevertheless make or makes a substantial contribution to the working of the invention”: Vehicle Monitoring Systems at [219].

153 In that case, Yates J also observed, in relation to the evidence of a particular witness, at [227], that:

[T]he question is not whether, absent the identified feature, the apparatus could still work effectively or whether, by other means, it could be adapted to work just as effectively. The question is whether, by this particular identified feature, a substantial contribution is made to the working of the invention as claimed.

154 I now turn to the application of these principles to the McDonald Patent and the Patents.

Claim 1 of the First Patent

155 PMG submitted that it is apparent from the expert evidence, informed by common general knowledge, that a skilled addressee would appreciate that each of the differences identified between the McDonald Patent and claim 1 make no substantial difference to the working of the alleged invention.

156 All the experts agree that the McDonald Patent does not disclose a garden hose and there is nothing in McDonald that suggests that it could be used as a garden hose or other applications generally.

157 The requirement that the hose be a garden hose is a difference that makes a substantial contribution to the working of a hose as a garden hose. That is the case whether the comparison is made with the mask and hose assembly or the hose alone disclosed in the McDonald Patent.

158 In addition, the following changes make a substantial contribution to the operation of the hose as a garden hose:

(a) changing the upstream coupler to a coupler capable of attachment to a pressurised water faucet;

(b) removing the mask; and

(c) changing the downstream coupler from one for coupling to a mask to one that is capable of coupling to a garden hose attachment.

159 Lastly, with respect to the dimensions of and materials used in the hose, the diameter of a hose for carrying gas is likely to be less than that for carrying water in a garden hose application, and the materials used are also likely to be different and may not be capable of resisting the pressures produced by a typical domestic garden tap.

160 Professor Armfield accepted that the diameter of the hose disclosed in the McDonald Patent could be thinner than that suitable for a garden hose, although he also thought it was possible that a thicker hose, such as might be suitable for a garden hose, could be used. The innovative step comparison must address whether a change in diameter makes a material contribution to the working of the invention.

161 However, putting aside any issue of the diameter, the differences between the McDonald Patent and claim 1 of the First Patent make a substantial difference to the working of the hose, and as such involve an innovative step.

Claim 2 of the First Patent

162 The kink-resistant feature when the hose is in a contracted state enables the hose to be “stored without worry of the hose kinking or becoming entangled” and “enables a user to store the hose in a very small space with no concern about having to untangle or unkink the hose when it is removed from storage and used”: First Patent at [0058].

163 There is no mention of kink-resistance in McDonald, nor disclosure of the materials used to make the inner and outer tubes. Whilst (as Professor Armfield said) there would be an expectation of resistance to kinking in the McDonald, this may not necessarily relate to the kink-resistant materials used to make the inner and outer tubes as found in the Patents. In addition, as I have already indicated, claim 2 teaches that the hose will not kink in the contracted condition.

164 A skilled addressee would appreciate the difference between claim 2 and the McDonald Patent in this regard, and the kink-resistant feature makes a substantial difference to the working of the hose.

Claim 3 of the First Patent

165 Claim 3 teaches that the upstream coupler is a female coupler and the downstream coupler is a male coupler. The McDonald Patent discloses two female couplers.

166 PMG submitted that since the choice of couplers does not affect the working of the hose, and since the fittings in the McDonald Patent provide the same facility as the couplers in the First Patent, the nature of the couplings will not make a substantial contribution to the working of the alleged invention.

167 Blue Gentian submitted that the use of a male coupler on one end of the hose and a female coupler at the other end is not disclosed in the McDonald Patent, and makes a substantial contribution to the working of the invention claimed as the feature enables the hose to act like an extension cord enabling “coupling of one hose to another”: First Patent at [0050].

168 In my view, the presence of a male coupler at one end and a female coupler at the other end enabling hoses to be coupled to each other, does make a substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

169 The skilled addressee would readily see this as a benefit of the claimed invention. The ability to couple to another hose increases the versatility of the invention and makes a substantial contribution to its working.

Claim 4 of the First Patent

170 Blue Gentian conceded that there was no relevant difference between the McDonald Patent and claim 4 when considered independently of claims 1 to 3.

Claim 5 of the First Patent