FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Coca-Cola Company v PepsiCo Inc (No 2) [2014] FCA 1287

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| Applicant | |

AND: | First Respondent PEPSICO AUSTRALIA HOLDINGS PTY LIMITED ACN 079 719 743 Second Respondent SCHWEPPES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 004 243 994 Third Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant’s application be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 876 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | THE COCA‑COLA COMPANY Applicant

|

AND: | PEPSICO INC First Respondent PEPSICO AUSTRALIA HOLDINGS PTY LIMITED ACN 079 719 743 Second Respondent SCHWEPPES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 004 243 994 Third Respondent

|

JUDGE: | BESANKO J |

DATE: | 28 november 2014 |

PLACE: | ADELAIDE via video link to melbourne |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 This is an application by The Coca-Cola Company (“TCCC”) for declarations, injunctions, damages, and other relief against PepsiCo Inc (“PepsiCo”), PepsiCo Australia Holdings Pty Limited (“PepsiCo Australia”), and Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd (“Schweppes”). A judge of this Court ordered that issues of liability be tried prior to, and separately from, issues of quantum. For the reasons that follow, TCCC’s application should be dismissed.

2 TCCC, which is incorporated according to the laws of the United States of America, and its licensees are the worldwide manufacturers of the well-known Coca-Cola beverages. TCCC sells these beverages in glass bottles, plastic bottles, and cans. TCCC’s glass bottle is well-known and is referred to by TCCC and in the market as the “Contour Bottle”. It is common ground that the Coca-Cola beverage has been widely sold in a variety of glass Contour Bottles since 1938 and that the trade marks “COCA-COLA” and “COKE” are well-known in Australia in relation to non-alcoholic beverages.

3 PepsiCo is incorporated according to the laws of the United States and it is the ultimate holding company of PepsiCo Australia, a company incorporated according to the laws of Australia. Schweppes is also incorporated according to the laws of Australia and it manufactures and sells PepsiCo’s products in Australia. It is common ground that PepsiCo and PepsiCo Australia have both directed or procured, and had close involvement in, Schweppes’ manufacture and sale of the Pepsi products. Furthermore, it is common ground that PepsiCo, PepsiCo Australia, and Schweppes, and each of them have, in the course of trade in Australia, dealt with or provided their existing PEPSI® and PEPSI MAX® branded cola beverages in a 300 ml glass bottle, and that the trade marks “PEPSI®” and “PEPSI MAX®” are well-known in Australia in relation to non-alcoholic beverages. Finally, it is common ground that PEPSI® and PEPSI MAX® branded cola beverages, as sold in the 300 ml Pepsi glass bottle, are non-alcoholic beverages falling within class 32 under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) and the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth).

4 TCCC owns four registered trade marks under the Trade Marks Act which are in issue in this proceeding. The details of the marks are as follows.

5 First, TCCC is and has been at all material times the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark No. 63697 (“TM 63697”), which has been registered with effect from 24 April 1937 in class 32 in respect of “Beverages and syrups for the manufacture of such beverages”. The trade mark consists of the following sign:

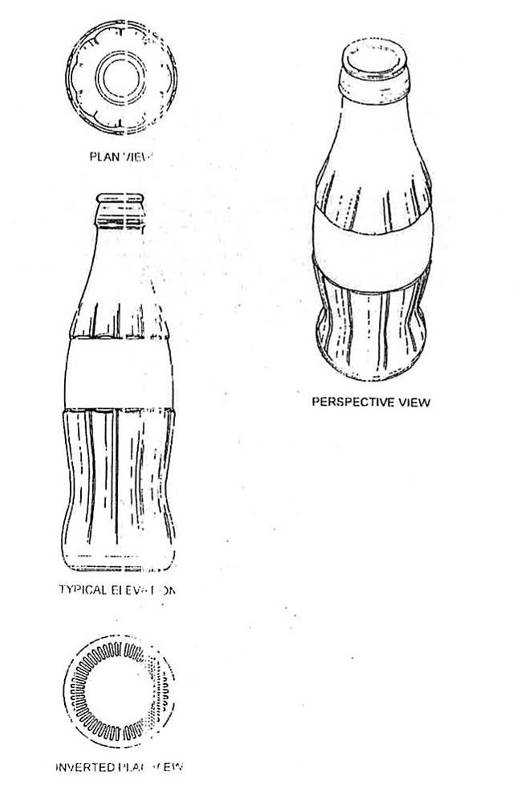

6 Secondly, TCCC is and has been at all material times the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark No. 767355 (“TM 767355”), which has been registered with effect from 14 July 1998 in class 32 in respect of “Beverages in class 32 excluding beers but including non-alcoholic drinks and beverages, mineral and aerated waters; soda water, dry ginger ale, tonic water, lemon squash, bitter lemon, lemonade, orangeade; fruit juices, fruit juice drinks and beverages containing fruit juice and fruit juice flavouring, including mineral and aerated water containing fruit juice or fruit juice flavouring; sports drinks including electrolyte replacement beverages for sports; dietetic and low calorie forms of all the foregoing goods; carbonated and non-carbonated soft drinks and concentrates for making same including beverages in containers; concentrates, syrups, powders and other preparations and substances for making all the foregoing goods”. The trade mark consists of the shape of a bottle as shown in the following representations:

7 Thirdly, TCCC is and has been at all material times the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark No. 1160893 (“TM 1160893”), which has been registered with effect from 12 February 2007 in class 32 in respect of “Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices”. The trade mark consists of the following sign:

8 Finally, TCCC is and has been at all material times the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark No. 1160894 (“TM 1160894”), which has been registered with effect from 12 February 2007 in class 32 in respect of “Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices”. The trade mark consists of the following sign:

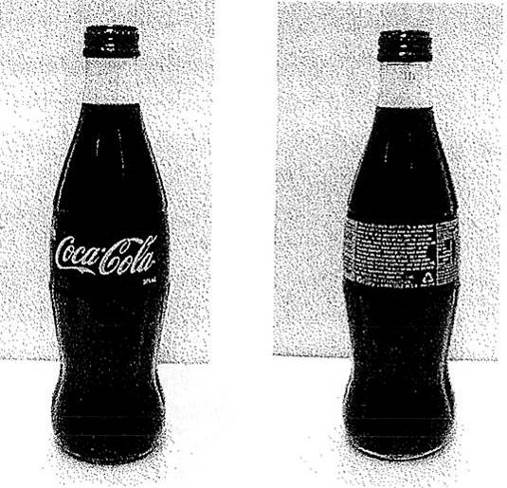

9 TCCC claims that each of the four trade marks comprise depictions of the Contour Bottle. TCCC claims that its Contour Bottle has a characteristic shape and silhouette, which it describes as a pinch in the bottom portion of the bottle, a relatively wide portion of the bottle above the pinch, and tapering of the bottle from the wider portion up to the neck of the bottle. Photographs of the Contour Bottle as shown in the Statement of Claim are as follows:

The Contour Bottle shown in the photograph contains the regular Coca-Cola beverage. There are other forms of the beverage which have reduced sugar or no sugar. The Contour Bottle containing the regular beverage is sold with a red cap or top, whereas the reduced or no sugar variations have different coloured caps or tops, including, with respect to the no sugar variant, a black coloured cap or top. The words “Coca-Cola” on the bottle are written in what is known as the Spencerian script.

10 TCCC claims that, in its advertising and marketing of the Coca-Cola beverage, it has made extensive and repeated use of the Contour Bottle or the silhouette of the Contour Bottle.

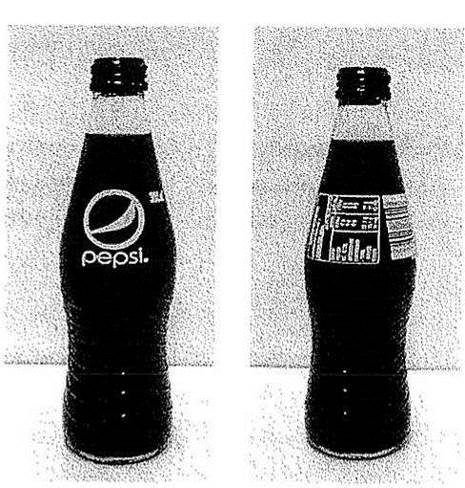

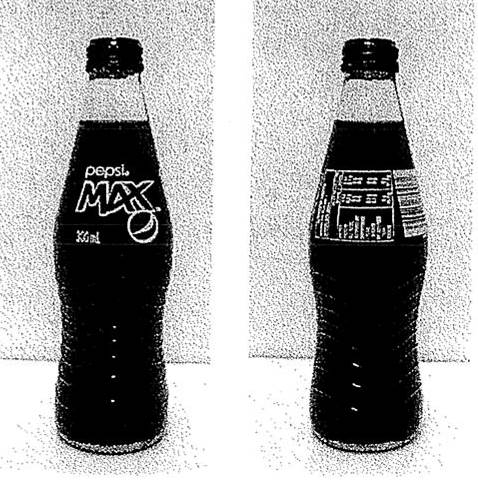

11 TCCC claims that the respondents have, in the course of trade in Australia, dealt with or provided cola beverage products in glass bottles which have a pinch in the bottom portion of the bottle, a relatively wide portion of the bottle above the pinch, and a tapering of the bottle from the wider portion up to the neck of the bottle. Photographs of the alleged infringing bottle as shown in the Statement of Claim are as follows:

The respondents refer to their bottle as the “Carolina Bottle”, and I will also use that description. The respondents also produce regular and reduced or no sugar beverages. The Carolina Bottle shown in the top two photographs contain the regular beverage. The bottle has a blue cap or top. The circular mark above the word “pepsi” contains the colours red, white, and blue, and was referred to as the “globe device”. The Carolina Bottle shown in the bottom two photographs contains one of the sugar variations of the Pepsi beverage and it has a black cap or top.

12 Various colour photographs of the Contour Bottle and the Carolina Bottle containing the regular beverages were put before the Court. Unfortunately, these photographs did not include a comparison of the bottles of the same height (i.e., Contour Bottle 330 ml and Carolina Bottle 300 ml). Nevertheless, the following photograph will give the reader a general idea of the colouring of each bottle:

13 TCCC alleges three causes of action against the respondents. First, it alleges that the Carolina Bottle infringes one or more of its four trade marks within s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act. On the evidence, and as the case was argued, the question of trade mark infringement raises two issues. The first issue is whether the respondents have used the shape of their Carolina Bottle or, in the alternative, that part of the shape of the bottle which comprises the outline or silhouette, as a trade mark within the meaning of ss 17 and 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act. The second issue only arises if the answer to the first issue is in the affirmative. It is whether the shape of the Carolina Bottle, or, in the alternative, the outline or silhouette of the bottle, is deceptively similar to one or more of TCCC’s four trade marks.

14 The second and third causes of action which TCCC alleges against the respondents are the tort of passing off and contraventions of ss 52 and 53(c) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). TCCC commenced this proceeding on 14 October 2010. That was before the commencement of item 7 in Schedule 7 of the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 2) 2010 (Cth) and, therefore, the Trade Practices Act continues to apply to this proceeding. However, TCCC’s application for injunctions is taken to be proceedings for an injunction under s 232 of the Australian Consumer Law (Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)). TCCC claims that it had developed in Australia substantial goodwill and a valuable reputation in the Contour Bottle and in the signs comprising the four trade marks. It claims that its business and goods have become “widely and favourably known and identified in the minds of consumers throughout Australia by reference to the Contour Bottle and the signs” comprising the four trade marks. TCCC claims that members of the public in Australia expect to be dealing with it, or persons authorised or approved by or otherwise associated with it, when they are offered for sale the Pepsi beverages in the Carolina Bottle. TCCC claims that the offering for sale and sale of the Pepsi beverages in the Carolina Bottle constitutes the passing off of the Pepsi beverages as products of TCCC or licensed by TCCC. Furthermore, it claims that such acts constitute a contravention of s 52 and a contravention of s 53(c) of the Trade Practices Act.

WITNESSES

15 TCCC adduced evidence from six witnesses.

16 Ms Lynette Davis is the Group Manager of Marketing Strategy and Insights at Coca-Cola South Pacific Pty Ltd (“CCSP”). CCSP is a wholly-owned subsidiary of TCCC and it is authorised by TCCC to manage the marketing, advertising, and sales promotion of products sold under the various trade marks owned by TCCC in the South Pacific region, including Australia. Ms Merle Le is the Manager – Shopper Merchandising and Marketing in the Customer and Commercial Department of CCSP. Ms Davis and Ms Le gave evidence about the history of TCCC and the Contour Bottle, the advertising and promotion of the Contour Bottle, and the trade channels through which it is sold. The respondents did not criticise the evidence of either Ms Davis or Ms Le. They were straightforward witnesses and I accept their evidence.

17 Ms Kristine Van Ruiten is a private investigator. She produced a number of photographs of bottles and cans displayed in fridges, coolers, and on shelves in different retail outlets. Her affidavit was tendered and she was not required for cross-examination by the respondents. Ms Rachel Peterson is a legal practitioner. She deposed to the circumstances in which TCCC and CCSP became aware of the fact that the Carolina Bottle was being offered for sale and sold in Australia. Her affidavit was tendered and she was not required for cross-examination. I accept the evidence of Ms Van Ruiten and Ms Peterson.

18 Dr Brian Gibbs is Principal Fellow in Marketing and Behavioural Science at the Melbourne Business School of the University of Melbourne. He swore two affidavits dated 16 July 2013 and 13 January 2014 respectively. Dr Gibbs gave expert evidence directed to the conclusions that a consumer would draw from the Carolina Bottle and its relationship to the Contour Bottle and TCCC. It was primarily relevant to the causes of action for passing off and contraventions of the Trade Practices Act. The respondents objected to the receipt of Dr Gibbs’ main report, but I overruled that objection for reasons set out below. Dr Gibbs’ evidence was confusing and unhelpful and, for reasons set out below, I give it no weight, except where it accords with evidence which I do accept.

19 Mr Barry Crone is an industrial designer with over 40 years’ experience in industrial design. He gave expert evidence about the matters that a designer would take into account in designing a bottle, the significant design features of the Contour Bottle and the extent to which those features are reflected in TCCC’s trade marks, and the similarities and differences between the Contour Bottle and the Carolina Bottle. He was a straightforward witness who expressed his opinions clearly. However, for reasons set out below, I do not accept a number of his opinions.

20 The respondents adduced evidence from eight witnesses.

21 Mr Robert Cumming is employed by PepsiCo Australia as Beverages Technical Manager. He gave evidence relating to the introduction of the Carolina Bottle into the Australian market. He was a straightforward witness and I accept his evidence. Mr Gary So is a Senior Brand Director of PepsiCo Global Beverages Group, which is part of PepsiCo. He gave evidence about the Pepsi business, its use of trade marks, and its advertising campaigns and sponsorship deals. In cross-examination, he was, at times, very cautious and not inclined to concede anything. However, as it happened, his evidence was, for the most part, uncontroversial and I accept it.

22 Mr Robert Le Bras-Brown was an employee of PepsiCo between June 2003 and November 2010. He gave evidence by video link from the United States. At the time of the events to which his evidence related, he was Director, Packaging Innovation and Development of PepsiCo International, and he played an important role in the design of the Carolina Bottle. It was suggested to him that, in designing the Carolina Bottle, PepsiCo had adopted the contoured shape of the Contour Bottle. I have considered his evidence very carefully. For reasons I will give, I have accepted the substance of his evidence. Mr Bradley Van Dijk is the Managing Director of PepsiCo Australia and New Zealand Beverages at PepsiCo Australia. He gave evidence about the Pepsi business in Australia, the PepsiCo products, and the outlets in which they are sold. He was a straightforward witness and I accept his evidence.

23 Ms Jennifer Evans is the Consumer Affairs Manager at PepsiCo Australia. She gave evidence about whether there had been any complaints made about the Carolina Bottle to PepsiCo Australia. Her affidavit was tendered and she was not required for cross-examination by TCCC. The same occurred in relation to Ms Sarah Vo, who is the Consumer and Quality Relations Manager at Schweppes. She gave evidence about whether there had been any complaints made about the Carolina Bottle to Schweppes. I accept the evidence of Ms Evans and Ms Vo.

24 Professor Jill Klein is a Professor of Marketing at the Melbourne Business School, Melbourne University. She gave expert evidence which commented on the opinions of Dr Gibbs. She was a straightforward witness and her evidence was clear and concise. For the most part, I accept her opinions. Mr William Hunter conducts his own consultancy business involving engineering designs, assistance in product development, and advice as an engineering design expert. His evidence included comments on the opinions expressed by Mr Crone. He was a straightforward witness. I do not accept everything he said, but I do accept the majority of the opinions he expressed.

TCCC AND THE CONTOUR BOTTLE

25 As I have said, TCCC’s case is that it has developed substantial goodwill and reputation in the Contour Bottle in Australia and in the signs which are the trade marks. Furthermore, its case is that, in Australia, its business and goods have become widely and favourably known and identified in the minds of consumers by reference to the Contour Bottle. It adduced evidence, primarily from Ms Davis and Ms Le, to establish a factual basis for those propositions.

26 In 1886, Mr J S Pemberton, a pharmacist, created a syrup beverage in Atlanta in the United States. The name “Coca-Cola” was chosen for the beverage and a Spencerian script adopted for use in advertising of the beverage. In 1892, TCCC was incorporated in Georgia in the United States. In 1916, TCCC adopted the Contour Bottle for its Coca-Cola beverage and, at about that time, it was patented in the United States.

27 From 1916, when TCCC adopted the Contour Bottle as the standard bottle for the Coca-Cola beverage and until 1955, throughout the world the 6½ ounce Contour Bottle was the only container used for the sale of the Coca-Cola beverage. In 1955, TCCC introduced larger sized Contour Bottles for the Coca-Cola beverage. In 1993, TCCC introduced into the market in the United States a 20 ounce PET bottle which was based on the Contour Bottle. PET refers to polyethylene terephthalate, which is a material commonly used for plastic beverage bottles, particularly for carbonated soft drinks.

28 In Australia, the Coca-Cola beverage has been sold in the Contour Bottle since 1937. In late 1937, TCCC commenced small scale bottling of the Coca-Cola beverage in Australia in North Sydney. In 1938, the first Coca-Cola bottling plant was set up in Waterloo in Sydney, where the 6½ ounce Contour Bottle was produced. In 1939, additional bottling operations were set up in South Melbourne, in Brisbane and in Adelaide. A further bottling plant was established in Perth during the Second World War. Over time, TCCC granted franchises in the major capital cities and in Newcastle, New South Wales. From 1963, the Coca-Cola beverage was sold in cans as well as bottles.

29 The Contour Bottle came in various sizes, including the 6½ ounce bottle and a 10 ounce bottle. In the 1970s, a 1 litre bottle was introduced. Other sizes to be produced have included a 237 ml bottle and a 185 ml bottle. For a short time, there was even an aluminium bottle based on the Contour Bottle.

30 The Coca-Cola beverages in the Contour Bottle are currently available in Australia in the following sizes: 175 ml, 250 ml, 330 ml, and 385 ml. Each of these bottles has been in continuous use from at least a date Ms Davis was able to identify by reference to archival material available to her (175 ml since 2006, 250 ml since 2003, 330 ml since 2001, and 385 ml since 2006).

31 In 1983, the Diet Coke beverage, which contains artificial sweeteners rather than sugar, was introduced into Australia. It is also sold in 175 ml, 250 ml, 330 ml, and 385 ml Contour Bottles. In January 2006, the Coke Zero beverage, which is a low kilojoule variety of the Coca-Cola beverage that contains no sugar, was introduced into Australia. It is also sold in 175 ml (2006 – 2009), 250 ml, 330 ml, and 385 ml Contour Bottles.

32 The Coca-Cola beverages in PET bottles, which TCCC claims were based on the Contour Bottle, are sold in Australia in the following sizes: 300 ml, 390 ml, 450 ml, 600 ml, 1.25 litre, 1.5 litre, and 2 litre.

33 The dominant colours of the regular Coca-Cola beverage are red and white, the dominant colours of the Diet Coke beverage are silver and white, and the dominant colours of the Coke Zero beverage are black and white.

34 At the present time, TCCC uses four primary trade marks to promote the Coca-Cola beverages. These are the word marks COCA-COLA and COKE, the Contour Bottle, and a ribbon device displayed on PET bottles and cans containing the Coca-Cola beverages. The Coca-Cola beverages are sold in three principal forms, being the traditional or regular formulation and two lower calorie formulations. The lower calorie formulations are promoted under the trade marks DIET COKE (known as COKE LIGHT in some markets) and COKE ZERO.

35 It is convenient at this point to mention that TCCC’s “Brand Identity and Design Standards” set out “Defining Elements” and “Supporting Elements” of the Contour Bottle. There are six Defining Elements and they are as follows:

(1) Contoured Shoulder;

(2) Flutes;

(3) Scalloped Transitions;

(4) Pinch Waist;

(5) Champagne Base; and

(6) Overall Proportions (silhouette) (relationship of elements to each other, from base to pinch waist to label area to shoulder).

36 Ms Davis said, and I accept, that, except for a relatively rare case where the bottle is sold in a plastic sleeve masking those features, the Contour Bottle always has the above features.

37 Between the years 2008 to 2012, approximately 40% of the carbonated soft drink market in Australia was comprised of Coca-Cola beverages and, in the same period, the market share of Pepsi for its cola products (Pepsi and Pepsi Max combined) was between about 10 to 12%.

38 The Coca-Cola beverages in the Contour Bottle have been sold in Australia in significant volumes. The Coca-Cola beverages in the Contour Bottle are sold through a variety of trade channels and Ms Davis provided the following estimates of the percentage of all Contour Bottles sold through each channel: the convenience and petroleum channel (10%), the grocery channel (15%), the immediate consumption channel (35%), and the hotels, restaurants and cafes channel (“HORECA”) (30%).

39 I have already referred to the role of CCSP. Coca-Cola Amatil (Aust) Pty Ltd, a subsidiary of Coca-Cola Amatil Limited, is currently the exclusive Australian bottler for TCCC in Australia.

40 From time to time, Coca-Cola Amatil (Aust) Pty Ltd, with the approval of TCCC, produces and sells in Australia what it calls “Limited Edition” or “Commemorative” Contour Bottles. For the 2003 Rugby World Cup, a 330 ml Contour Bottle in limited edition packs was produced and sold. As part of a Christmas 2006 promotion, two 330 ml Contour Bottles in four packs were produced and sold. For the 2008 Rugby League State of Origin Grand Final, two 385 ml Contour Bottles were produced and sold in Queensland and New South Wales exclusively in Caltex stores. Finally, in 2008, and as part of a promotion of the Rugby League team Saint George Illawarra, a special Contour Bottle, available only to consumers who signed up as members of the club in 2008, was produced and sold.

41 Coca-Cola products are heavily advertised in Australia. CCSP and Coca-Cola Amatil (Aust) Pty Ltd work together in formulating these advertising campaigns. CCSP conducts approximately five to six national advertising campaigns each year and each campaign can cost between $3 and $5 million and, on occasions, more than that.

42 These advertising campaigns focus on the Coca-Cola brand and its symbols, which include the Spencerian script, the Contour Bottle, the colour red, and the dynamic ribbon device, and they also focus on an association of the Coca-Cola brand with ideas of good times, happiness, fun, family, and friends.

43 Ms Davis gave evidence of various advertising campaigns which she said were examples of the type of campaigns which had been conducted.

44 In 2005, CCSP conducted an extensive advertising campaign in Australia to launch a new flavour of the Coca-Cola beverage known as “Coke Lime”. The campaign included outdoor advertising, television, radio and on-line advertising, as well as prominent in-store point of sale advertising and product placement. A black silhouette of a bottle (among other colours) was used during this campaign. In some of the material, it seems to accord fairly closely with TM 1160894, but in other material it seems to have a different cap shape or, more importantly, a different contour shape.

45 The “Coke Side of Life” campaign was conducted between 2006 and 2008 and the campaign involved outdoor advertising on billboards, on the back of buses, on vending machines, on vehicles, in and around stores, on television, on-line, in magazines, and in cinemas. In addition, there was advertising signage at railway stations. The image of the Contour Bottle was a prominent part of this campaign. I do not need to refer to all of the material produced by Ms Davis. It shows that key features of the Coke Side of Life campaign were the Contour Bottle, the Spencerian script, and the colour red. The expenditure on the campaign was very substantial and, by way of example, Ms Davis said that approximately $3.2 million was spent on advertising in the three month period from January to March 2007.

46 CCSP has conducted other campaigns in Australia of a similar nature to the Coke Side of Life campaign. The Contour Bottle is a prominent feature of the advertising in these campaigns. They include the “Open Happiness” campaign in 2009 and campaigns during Christmas, Easter, the summer holiday period (for example, the “Summer of Us” campaign for the summer of 2007/2008), and the football seasons for the Australian Football League (“AFL”) and the National Rugby League (“NRL”).

47 Ms Davis accepted that, with some exceptions, it was not until the “Open Summer” campaign in 2009/2010 that a silhouette image of the Contour Bottle appeared without any writing on it or other features. The exceptions were the Coke Lime campaign in 2005, an AFL football shaped as a Contour Bottle in 2005, and cans produced as part of the Summer of Us campaign in early 2008. Ms Davis said that in 2009 there was a directive from the headquarters of TCCC to the effect that the unadorned silhouette was to be emphasised in advertising. The significance of the date upon which the unadorned outline or silhouette of the Contour Bottle was emphasised in advertising will become clear when I come to deal with TCCC’s passing off and Trade Practices Act claims.

48 Ms Le provided further evidence of CCSP’s approach to the marketing of Coca-Cola beverages. It is very sophisticated. Ms Le said that CCSP divides the path to purchase of a consumer into four zones – the proximity zone, the transition zone, the impulse zone, and the destination zone – and formulates an advertising strategy for each zone. The proximity zone is about 600 m from a retail outlet, and the destination zone is at the primary beverage location within a store and is either a shelf or a refrigerator where the products are available for purchase. Packaging is a key component in TCCC’s communication to customers at the destination zone, and, furthermore, distinctive TCCC packaging often appears in the transition zone and the impulse zone so as to “resonate” with products available at the destination zone.

49 Ms Le confirmed Ms Davis’ evidence that TCCC uses four primary trade marks to promote the Coca-Cola beverages in Australia (and throughout the world) and they are the word marks COCA-COLA and COKE, the Contour Bottle, and the dynamic ribbon device.

50 Ms Le said, and I accept, that the Contour Bottle, being a glass bottle, is the premium packaging for the Coca-Cola beverages in Australia. That was accepted by all of the witnesses who were asked to comment on the issue.

51 Ms Le gave evidence of the trade channels through which the Coca-Cola beverages, whether in the Contour Bottle or otherwise, are sold. Her categories were the same as Ms Davis, except that she added a fifth category of quick service restaurants. She also referred to a vending channel (i.e., vending machines). She said that examples of the outlets in the convenience and petroleum channel are convenience stores, such as 7-Eleven stores, and petroleum outlets, such as those operated by BP and Shell. Examples of the grocery channel are supermarkets, such as Coles, Woolworths, and independent supermarkets, as well as large retail stores, such as K-Mart and Big W. Examples of the outlets in immediate consumption channel are corner stores and milk bars, fish and chip shops, pizza, and takeaway chicken outlets. She said that the HORECA channel included bistros, coffee shops, hotels, and restaurants, and quick service restaurants included chains such as McDonalds and Hungry Jacks. The Coca-Cola beverages in the Contour Bottle are principally sold through the convenience and petroleum channel, the immediate consumption channel, and the HORECA channel.

52 The Coca-Cola beverages are currently sold in the Contour Bottle in sizes which are designed to be consumed immediately or soon after purchase. Coca-Cola beverages sold in the Contour Bottle are typically refrigerated. They are kept in refrigerators or open air coolers. The refrigerators are enclosed, or at least partly enclosed.

53 Again, like Ms Davis, Ms Le gave evidence of advertising campaigns involving the use of the Contour Bottle as follows: Ruby League State of Origin series between Queensland and New South Wales (mid 2009); “Open Summer” campaign (summer 2009/2010); Easter campaign (Easter 2010); FIFA World Cup (April 2010); and AFL and NRL Final Series (winter/spring 2010).

54 Ms Le described an incident in late 2010 or early 2011 when she saw one of the respondents’ products on display in a refrigerator. Initially, she mistakenly believed it was a Coca-Cola beverage in the Contour Bottle until she was close enough to see the blue cap on the bottle. At that point, she realised that it was not a Coca-Cola beverage.

55 The evidence of Ms Davis and Ms Le dealt with two important matters in terms of the issues in this case.

56 The first matter is relevant to the context in which the Contour Bottle is offered for sale and sold. Ms Davis offered some percentage estimates with respect to the trade channels through which the Contour Bottle is sold. The evidence was fairly general and I do not think I can, or indeed need to, make a finding in precise terms. I find that substantial sales of the Contour Bottle are effected in circumstances where a consumer selects the beverage that he or she wants from a refrigerator or open air cooler.

57 The second matter relates to TCCC’s advertising of the Contour Bottle and this is relevant to TCCC’s reputation in the Contour Bottle. Due to the issues in this case, in examining the evidence of TCCC’s advertising, I considered the circumstances in which the whole of the Contour Bottle was shown, including, for example, the vertical fluting, and circumstances where only the outline or silhouette of the Contour Bottle was shown. I also considered the extent to which the Contour Bottle, either its whole shape or only its outline or silhouette, appeared with other signs such as word marks, and the extent to which the Contour Bottle, or only its outline or silhouette, was the prominent feature in the advertisement.

58 Furthermore, in considering this evidence, there is another issue to be borne in mind. There is a dispute between the parties as to the date upon which TCCC’s reputation in the Contour Bottle is to be assessed. The respondents submitted that the relevant date is August 2007 and that TCCC’s advertising after this date is irrelevant. TCCC submitted that the relevant date is February 2009 and that I can take into account TCCC’s advertising up until that date. I deal later in these reasons with the issue of the correct date.

59 The Contour Bottle with all its features, including, for example, the vertical fluting, was featured in TCCC’s Australian advertising prior to August 2007, together with the word marks, Spencerian script, and the colour red. Some of the advertising prior to August 2007 involved other signs, but with only the outline or silhouette of the Contour Bottle. Prior to August 2007, the circumstances in which the outline or silhouette of the Contour Bottle dominated the advertising were isolated and fairly rare. The most notable occasion upon which this occurred was the “Coke Lime” campaign in 2005 and, even in the case of that campaign, a somewhat imprecise silhouette of the Contour Bottle was used. Circumstances where only the outline or silhouette of the Contour Bottle was used, such as with the AFL football, were so rare that I do not think that they can form a basis for any conclusion. In 2009, TCCC decided to emphasise the unadorned silhouette in its advertising and issued a directive to that effect. I am not able to detect any significant change in TCCC’s advertising between August 2007 and February 2009, and, as I will explain later in these reasons, I do not think TCCC’s reputation in the Contour Bottle is any different as between those two dates.

60 Ms Van Ruiten was asked by TCCC to make investigations into single serve non-alcoholic carbonated beverages in Australia. She was instructed to investigate the range of different bottles in which such beverages were packaged and to purchase a broad sample of such products, having particular regard to bottles made from glass and bottles having a waisted or tapered side wall section. She carried out those instructions in February 2013 and purchased 17 bottles (plus the respondents’ Pepsi Max beverage), and these 17 bottles were referred to in evidence as the “third party” bottles. Three of these bottles may be described as having waists, although they are different in shape and degree. Those bottles are the Lucozade, Schweppes and PET bottles. However, other than the Schweppes bottle, which was on the market before August 2007, there was no evidence before me as to when the third party bottles first came onto the market.

61 The respondents put in evidence a number of other bottles and I will refer to these as the “additional bottles”. All of these additional bottles clearly had waists of one sort or another. However, the evidence went no further than establishing that three of these bottles – a Mount Franklin bottle, a H2Go bottle, and a Mizone bottle – were on the market in August 2007.

62 I think the evidence establishes that, apart from the Contour Bottle, there were at least four, perhaps six, bottles with waists of varying degrees on the Australian market in August 2007. It follows that the fact that the Contour Bottle had a waist was not a unique feature in August 2007. In addition, as the respondents submitted, I think that the fact that the additional bottles have waists illustrates the legitimate desire of manufacturers and traders to use that feature otherwise than as a trade mark in the same way as widespread use of a descriptive word might indicate that it is not being used as a trade mark.

63 Ms Van Ruiten was also instructed to photograph the manner in which single serve non-alcoholic carbonated beverages were displayed for sale in refrigerators within retail outlets such as convenience stores or food service outlets. She carried out her instructions in May 2013 and 26 photographs were tendered in evidence. In a number of cases, the beverages are kept in enclosed refrigerators with glass doors or in open coolers. In other cases, the beverages are displayed on open shelves.

64 Ms Peterson is employed by CCSP as the Business Unit Counsel. She is responsible for overseeing and managing legal issues which arise as a result of the marketing, advertising, and promotion of products by CCSP under the TCCC trade marks in the South Pacific region. CCSP monitors the market in Australia for potential breaches of TCCC’s trade mark rights. Employees of both CCSP and Coca-Cola Amatil (Aust) Pty Ltd are given a certain level of training and instruction about TCCC’s trade marks. In November 2009, it was brought to Ms Peterson’s attention that a Pepsi RAW Bottle might have been displayed for sale in Melbourne. The Pepsi RAW Bottle was a bottle sold in England which was the equivalent of the Carolina Bottle. In January and February 2010, Ms Peterson became aware that the Carolina Bottle was being offered for sale and sold in Australia. TCCC commenced this proceeding on 14 October 2010.

THE RESPONDENTS and The Carolina Bottle

65 In a number of respects, the early history of the Pepsi beverage is similar to the early history of the Coca-Cola beverage.

66 In the 1890s, Mr C Bradham, a pharmacist in New Bern in North Carolina, invented the recipe for Pepsi-Cola. The Pepsi-Cola beverage was sold under the trade mark PEPSI-COLA from 1898 and under the trade mark PEPSI from 1911. The company’s trade marks now also include the word marks PEPSI LIGHT, PEPSI MAX, PEPSI TWIST, DIET PEPSI, and PEPSI NEXT, and a variety of device or brand marks.

67 In 1931, the predecessor to PepsiCo was formed under the name Pepsi-Cola Company and, in 1965, the company name was changed to its present name.

68 From 1958, PepsiCo used a glass bottle known as the “Swirl” glass bottle. Photographs of the Swirl glass bottle are shown below (at [82]). By December 1968, PepsiCo had obtained trade mark registration in the United States in relation to the shape of the Swirl glass bottle. By May 2004, PepsiCo had obtained trade mark registration in the United States in relation to the shape of the Swirl PET bottle. Mr So agreed in his evidence that PepsiCo believed, and continues to believe, that the Swirl glass bottle design and the Swirl PET bottle design are distinctive of it and its products.

69 In 1993, Pepsi Max was released as a low-kilojoule, sugar-free cola alternative to Diet Pepsi or Pepsi Light.

70 Since 2005, PepsiCo and its bottlers in at least 30 countries worldwide have launched and sold Pepsi soft drinks in glass bottles which are the same or closely similar to, in terms of shape, the Carolina Bottle which is the bottle sold in Australia.

71 PepsiCo is a worldwide distributor of soft drinks and snack products. The company, and its wholly-owned subsidiaries and affiliates, is one of the two largest soft drink companies in the world. The other company is TCCC. PepsiCo is the largest seller of salted snack products in the world. The PEPSI mark has been used consistently over the years. By contrast, the Pepsi logo has changed over the years.

72 The word marks PEPSI and PEPSI MAX have been registered as trade marks in a number of jurisdictions throughout the world and they have an international reputation. PepsiCo engages in intensive advertising campaigns in Australia for its Pepsi beverages.

73 Pepsi beverages in the Carolina Bottle are sold through similar channels as Coca-Cola beverages. Mr Van Dijk identified substantial sales through the grocery channel and the petrol and convenience channel. He also referred to substantial sales through the HORECA channel. He said that Pepsi beverages are also sold through the on-premise and licensed on-premise channel, the impulse channel, and the quick service restaurants channel.

74 Pepsi beverages are sold in PET bottles and in cans of various sizes, as well as being sold in the 300 ml glass bottle. They are sold as a single item or as multi-packs.

75 Schweppes supplies some of its trade customers with a refrigerator for the purpose of stocking Schweppes and Pepsi products. These refrigerators often have Schweppes or Pepsi branding on them.

76 Sales of the Pepsi beverages in the Carolina Bottle have been very low compared with sales of the Pepsi beverages in PET bottles or cans. There has been some trade advertising of the Carolina Bottle, but no large-scale advertising campaigns directed to consumers. As might be anticipated, the respondents’ marketing is, like TCCC’s, very sophisticated.

77 It is necessary to address the design process for the Carolina Bottle. This issue is relevant because TCCC submits that, in designing the Carolina Bottle, PepsiCo and PepsiCo Australia had an intention to deceive and that, insofar as this is a borderline case with respect to any of TCCC’s claims, an intention to deceive tips the scales in its favour. The precise submission made by TCCC is that the respondents should be taken to have been aware of the risk of confusion by reason of its Carolina Bottle and decided to take that risk. I discuss the relevant legal principles later in these reasons.

78 The Carolina Bottle was designed in the United States for world-wide purposes and Mr Le Bras-Brown played an important role in that process. The Carolina Bottle was first introduced into the Australian market in August 2007. Mr Cumming played a part in the process whereby that occurred. When I refer to the Carolina Bottle in this context, I ignore (as did the parties) minor differences which might be due to an individual bottler’s constraints or needs.

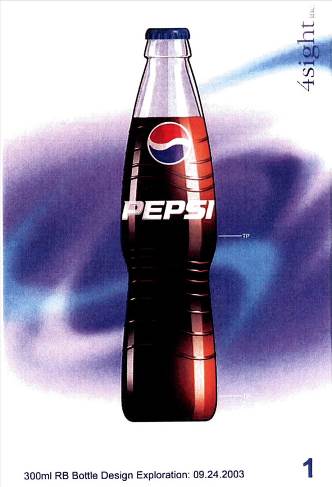

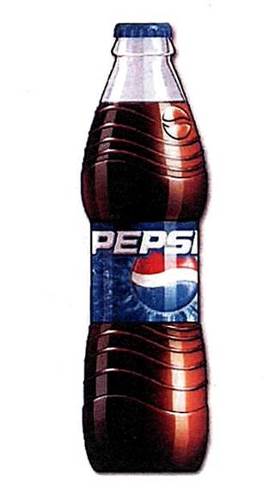

79 Mr Le Bras-Brown joined PepsiCo in June 2003. Before June 2003, PepsiCo commenced a project in the United States which was known within the company as the “Carolina project”. The project involved the formulation of a design of its PET bottles to a design called the “Carolina PET”. To assist in that process, PepsiCo engaged a New York design firm known as 4sight inc (“4sight”). The actual design process which resulted in the Carolina PET had been completed before June 2003. The first PET bottle with the Carolina design was a 2 litre bottle, but there followed a range of both smaller and larger sized PET bottles. An image of the Carolina PET Bottle appears below.

80 The principal design features of the Carolina PET were, first, a series of undulating horizontal wavy lines which appear above and below the label and, secondly, a significant “drawing in” of the bottle in its middle. The horizontal wavy lines were considered to be a feature which assisted in ensuring the bottle retained its shape and resisted a process called creep. Creep is a condition where a bottle takes on a rounded shape because of internal pressure. In addition, the horizontal wavy lines were considered to convey the image of Pepsi expanding by the use of sinusoidal pattern where the waves expand logarithmically. The “drawn in” middle of the bottle meant that the bottle was easier to grip and, therefore, it was easier to pour the contents.

81 The next stage of what was now known within PepsiCo as the Carolina project was the design and development of two glass bottles, one a returnable glass bottle (“RGB”) and the other a non-returnable glass bottle (“NRGB”), to complement the Carolina PET. Mr Le Bras-Brown was directed to lead this stage. His design brief was to produce a design for a bottle which was an “ownable” and a proprietary design for PepsiCo. The bottle was to have an exciting look and feel that matched or complemented the existing Carolina PET bottle. Mr Le Bras-Brown said that he wanted to take the undulating horizontal wave feature and translate it to glass. He wanted to design a bottle that was uniquely Pepsi and was an iconic bottle that the public would identify as “the Pepsi bottle”.

82 Mr Le Bras-Brown’s understanding was that, from at least the 1980s, PepsiCo’s glass bottle was called the “Swirl Bottle”. A key design feature of the Swirl Bottle was twisted diagonal fluting which was described by Mr Le Bras-Brown as like a Corinthian pillar that had been twisted in the middle. He said that the Swirl Bottle had a shoulder that led into a drawn in mid-section and then a pronounced heel at the bottom of the bottle. Although the images are not particularly good, I set out below a picture (left) showing the PepsiCo Swirl glass bottle on the left of other bottles and cups. Another image of the Swirl Bottle is shown on the right.

83 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that the design of a glass bottle which is to carry a carbonated soft drink is subject to constraints, and that those constraints differ according to whether the glass bottle is to be produced as a RGB or as a NRGB. A RGB is made of relatively thick glass and the bottles are collected by PepsiCo, or one of its subsidiaries, and are reused after a process of cleaning. A NRGB is made of relatively thin glass and is not collected for reuse.

84 Both types of glass bottle must be capable of being used on a bottle production line. A RGB must be capable of being collected after use, stored, and refilled. This means there are greater design constraints in the case of a RGB. The design of a RGB must accommodate an existing bottle float (i.e., the collection of bottles being used and reused), which may be very valuable and which may include up to six prior versions of the company’s glass bottle. To accommodate the existing bottle float, the designer of a bottle must have regard to the height, fill height, and diameter of existing bottles, and the likely “touch” points on the production line between the existing bottles and any proposed new bottle. For example, it is important that the touch points remain the same so that the old and new bottles can continue to be processed, washed, bottled, and stored together in the bottling plant. It is important not to place any decorative features at the touch points because they can be damaged. A bottle must also have a sufficiently low centre of gravity so that it is not easily knocked over.

85 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that there is more freedom for designers in the case of the NRGB, which are only used once. Nevertheless, there are still some constraints and they result from the dimensions of the bottling line and the size of crates and coolers.

86 The firm 4sight assisted Mr Le Bras-Brown and his team in the design of the Carolina Bottle, both the RGB and the NRGB. In broad terms, the process was that 4sight provided concept drawings to Mr Le Bras-Brown and his team, who then ruled out those concepts which they considered inappropriate and with respect to the balance, sought the comments of PepsiCo’s marketing department. Drawings of preferred designs were then forwarded to 4sight, who were required to ensure that the drawings were volumetrically accurate. Once a design was selected, it was to be sent to a glass supplier in a pilot market for its views and the preparation of final engineering drawings.

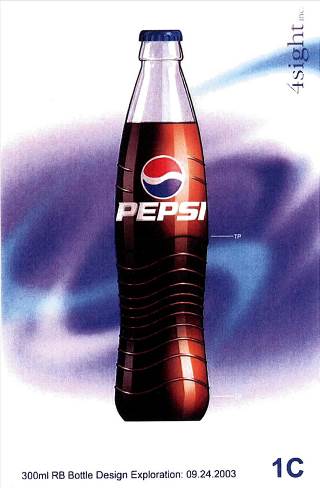

87 In October 2003, the preferred designs for the Carolina RGB were those designated by 4sight as “1” (300ml RB Bottle Design Exploration: 09.24.2003) and “1C” (300ml RB Bottle Design Exploration: 09.24.2003). Images of those designs are as follows:

It can be seen from these images that both of these designs have a rounded shoulder and that Design 1 has a pronounced bulge above the waist of the bottle.

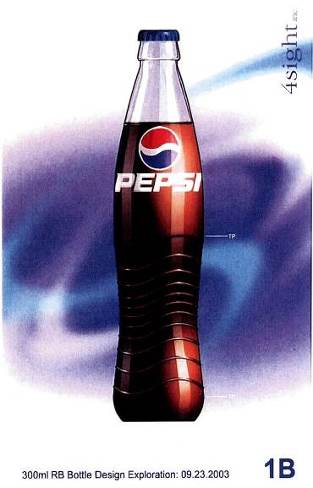

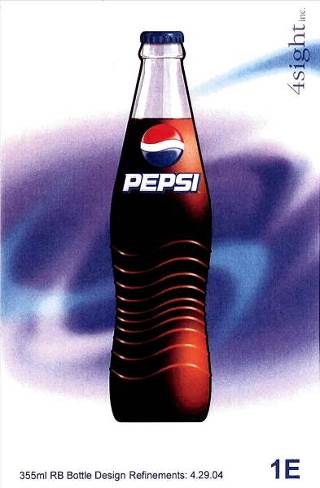

88 As it happened, the final choice came down to a choice between those designs designated by 4sight as “1B” (300ml RB Bottle Design Exploration: 09.23.2003) and “IE” (355ml RB Bottle Design Refinements: 4.29.04). Images of those designs are as follows:

89 The principal difference between Design 1B and Design 1E is the shape of the shoulder of the bottle, with Design 1E being more conical and Design 1B being more similar to the silhouette of the Swirl Bottle.

90 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that he considered that one advantage of Design 1E was that it had a straight tapered shoulder and that facilitated tactiphane labelling. Tactiphane is a form of clear paper which is made using cellophane cells. The advantage of tactiphane labelling is that it gives a no label look, but in fact it can be washed off the bottle when it is returned to the bottlers. This is an advantage for bottlers because it makes the bottle generic in a labelling sense. Mr Le Bras-Brown was very keen that there should be a shoulder on the Carolina RGB that could be used for ACL labelling and also tactiphane technology, where available.

91 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that he and his team chose Design 1E over Design 1B for both aesthetic and practical reasons. They considered Design 1E to be better looking, more attractive and contemporary than Design 1B, and, with the tapered shoulder, it provided maximum flexibility with labelling options. The final decision was made by a group of people within PepsiCo, some from the design section and some from the marketing section.

92 Mr Le Bras-Brown agreed in cross-examination that he had not provided any explanation as to why the “pronounced bulge design” (shown in Design 1 and similar images with slight variations) had been rejected.

93 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that he was aware of the Contour Bottle and that he “designed away” from that bottle because he wanted PepsiCo to have its own distinctive bottle and because he did not want to become embroiled in disputes with TCCC.

94 As far as the NRGB was concerned, the design ultimately selected was similar to the Carolina PET, but that design was only appropriate for jurisdictions where the “belly band” paper label was viable. That did not include Australia and, in this country, the design for the NRGB was the same as the design for the RGB. An image of the NRGB for countries where the belt band paper label was viable is as follows:

95 Mr Le Bras-Brown said that the above design for the NRGB achieved the objective of complementing the Carolina PET design, but the RGB was not able to take those features. His evidence was that, nevertheless, both types of bottle had the “Carolina family look dominated by the waves that were in the bottle”.

96 Mr Le Bras-Brown agreed that the Carolina RGB is not a generic bottle and that it is distinctive and was intended by PepsiCo to be distinctive.

97 PepsiCo made design applications throughout the world in relation to Design 1E and there are two Australian registered designs for that design.

98 There were features of Mr Le Bras-Brown’s evidence which caused me to scrutinise it carefully. First, he gave a good deal of evidence about design constraints and I have summarised that evidence. However, for the most part, that evidence was not linked to particular design choices made by Mr Le Bras-Brown. Secondly, he accepted in cross-examination that he had not given any evidence explaining when and why the “pronounced bulge” design was rejected. It might, however, be inferred from some earlier evidence Mr Le Bras-Brown gave that the “pronounced bulge” design was rejected because it was too “top heavy”. Thirdly, to my mind, it is undoubtedly the case that the Carolina Bottle is, in overall appearance, closer to the Contour Bottle than either the Swirl glass bottle or the NRGB where the belly band label is used. Despite these matters, I do not think that Mr Le Bras-Brown had an intention to deceive or an intention to copy the Contour Bottle. All of the designs he considered had a contoured shape. All of the design images show the bottles clearly marked with the word “Pepsi” and the globe device, and Mr Le Bras-Brown would have been aware that this is how they were displayed for sale. All of the design images also clearly show the horizontal waves and this was an important design feature and it was a link with the Carolina PET. I accept Mr Le Bras-Brown’s evidence that labelling flexibility was the reason he chose the Design 1E over Design 1B. Mr Le Bras-Brown was asked whether other labelling on the NRGB designed for the belly band labelling was feasible. He said ACL labelling was not possible and that tactiphane labelling would be very expensive. ACL labelling refers to applied ceramic labelling, where a permanent ink label is fired onto glass using silk screening. Mr Le Bras-Brown’s evidence about the difficulty with ACL labelling is supported by a contemporaneous email he wrote to other employees of PepsiCo on 16 August 2005. In cross-examination, Mr Hunter said that both forms of labelling would be possible, although he did not seem to have a deep knowledge of tactiphane labelling. I am not satisfied that I should reject Mr Le Bras-Brown on the basis of the very brief and, to some extent, undeveloped evidence of Mr Hunter in cross-examination. Whether Mr Le Bras-Brown was, without realising it, affected in some way by the attractive features of the Contour Bottle, I cannot say. I can say that I am not satisfied that he had an intention to deceive or cause confusion, or an intention to copy the Contour Bottle.

99 I turn now to the introduction of the Carolina Bottle into the Australian market. Prior to the introduction of the Carolina Bottle, the Pepsi beverages were sold in the Swirl bottle and that was a NRGB.

100 Until 2006, the Pepsi beverages were also sold in a PET Swirl or “Global Swirl” bottle. Sometime in 2006, PepsiCo Australia changed from the Global Swirl PET Bottle to the Carolina PET Bottle.

101 In the same year, PepsiCo Australia and Schweppes began considering the introduction of the Carolina Bottle into Australia. That was prompted by what was happening internationally and by the fact that, at that time, the moulds for the existing glass bottle design were wearing out and would soon need replacing.

102 On 24 August 2006, Mr Cumming wrote to Mr Le Bras-Brown asking for drawings and examples of the different options for the Carolina Bottle, non-returnable, and with a capacity of 300/390 ml. Mr Cumming advised Mr Le Bras-Brown that he was considering adhesive labelling or ACL printed artwork. Mr Le Bras-Brown sent Mr Cumming some drawings the next day. Those drawings showed two options, one appropriate for a paper label around the middle of the bottle, and the other was the design for the Carolina Bottle. Mr Cumming favoured the design for the Carolina Bottle because, unlike the first option, it did not involve the extra costs associated with a special label, and because he considered that it had a more conventional shape. He considered that it looked similar to the Schweppes 300 ml glass bottle. That was of some significance because the 300 ml Pepsi and Pepsi Max beverages would ordinarily be offered for sale as part of the Schweppes 300 ml glass range.

103 Ultimately, it was the marketing department of PepsiCo Australia, in consultation with Schweppes, that made the decision to adopt the Carolina Bottle.

104 As I have said, I accept Mr Cumming’s evidence and I do not think that there was any intention to deceive or cause confusion or copy the Contour Bottle on his part. Nor could it be said (as TCCC put in its written submissions) that he knowingly took a risk that consumers would be confused by the Carolina Bottle.

105 In August 2007, the Carolina Bottle for Pepsi beverages was launched in Australia. In 2008, PepsiCo Australia and Schweppes experienced a problem with the glass manufacturer and they decided to change to a new manufacturer. That had two consequences. First, it led to some very minor modifications to the design of the bottle. Secondly, it resulted in the respondents selling the Pepsi beverages in Australia in a generic bottle, rather than the Carolina Bottle, between May 2008 and February 2009. They resumed selling the Pepsi beverages in the Carolina Bottle after February 2009.

106 PepsiCo Australia and Schweppes changed manufacturers again in late 2013 and again there were some very minor changes to the design of the Carolina Bottle.

107 PepsiCo has not applied to register the Carolina Bottle shape as a trade mark in the United States or any other jurisdiction.

108 In Germany, PepsiCo released a 200 ml Carolina Bottle in April 2009 and a 330 ml Carolina Bottle in May 2010. In July 2010, TCCC sent PepsiCo’s German subsidiary a cease and desist letter. TCCC launched proceedings alleging infringement of certain of TCCC’s registered Community and German trade marks, but was unsuccessful at first instance. TCCC has appealed, but the appeal has not yet been heard.

109 In New Zealand, PepsiCo released beverages in the Carolina Bottle in 2009. TCCC commenced proceedings against PepsiCo and Frucor Soft Drinks Ltd alleging trade mark infringement, passing off, and breaches of the Fair Trading Act 1986 (NZ) in relation to the sale of Pepsi beverages. Again it was unsuccessful at first instance (Coca-Cola Co v Frucor Soft Drinks Ltd and Another (2013) 104 IPR 432; [2013] NZHC 3282). TCCC had lodged an appeal.

110 TCCC has not complained about PepsiCo’s use of the Carolina Bottle in any other jurisdiction.

111 Ms Evans’ duties include supervising and overseeing the operation of the Consumer Information Centre at PepsiCo Australia and reporting details of complaints and feedback to the management of the company. She has access to PepsiCo Australia’s books and records in relation to complaints and feedback received in the ordinary course of business. Her evidence establishes, and I find, that PepsiCo Australia has no record of having received any complaints or feedback regarding the shape of the Carolina Bottle, or any similarities between it and any other product.

112 Ms Vo’s evidence establishes that, as exclusive bottler of PepsiCo’s products in Australia, Schweppes also handles any complaints or feedback regarding those products, and that Schweppes has a fairly sophisticated system for recording complaints and feedback from consumers and for bringing those complaints or that feedback to the attention of the appropriate person within Schweppes. Her evidence establishes that no complaint about the shape of the Carolina Bottle, or any similarities or confusion between it and any other product, has been recorded by Schweppes.

The EXPERT Evidence

Matters of Design

113 Mr Crone is an industrial designer who has practised in the field of industrial design for over 40 years. He is the Managing Director of UNO Australia Pty Ltd, which is a design consultancy firm based in Melbourne. The firm provides design services in branding, packaging and visual communication, product design and engineering, and interior design for “retail and exhibitions”.

114 Mr Crone outlined the process a designer would follow in the ordinary case in designing packaging for a client. It is not necessary for me to set out the details. One point which Mr Crone made in the course of giving his evidence, and which is contentious, is that consumers recognise colour and shape before they recognise symbols and words.

115 Mr Crone identified various features of the Contour Bottle and expressed the opinion that the most significant aspect of the appearance and packaging of the Contour Bottle was the low waisted contour shape as seen in profile, that is, the silhouette of the bottle. He expressed the opinion that the overall shape of the Contour Bottle is a major contributor to the easy recognition of the product. In considering a bottle where ACL labelling is used and the words appear in the Spencerian script, Mr Crone said that the dominant colour was the dark brown colour of the contents of the bottle. Mr Crone said that the labelling (i.e., the Spencerian script) and the decoration flutes were also important design features of the Contour Bottle, but would be noticed after the overall low waisted contour shape and dark brown colour. The type and colour of the cap or top was also an important design feature.

116 Mr Crone expressed the opinion that, from a design perspective, the signs constituting TCCC’s four trade marks reflect as their single most recognisable element the overall low waisted contoured shape with its proportions.

117 Mr Crone was provided with the third party bottles purchased by Ms Van Ruiten. He examined these bottles and concluded that the Contour Bottle was of a significantly different appearance and that those third party bottles were all substantially different for one reason or another. He said that only three of the third party bottles – the Lucozade Bottle, the Schweppes Bottle, and the V PET Bottle – had a waist of some sort. However, for reasons he gave in evidence, he expressed the view that that is where the degree of resemblance with the Contour Bottle ends.

118 In cross-examination, Mr Crone agreed that the Lucozade bottle had a “lowish” waist, “somewhat”, and a “somewhat” contoured shape. He agreed that the Schweppes Bottle and the V PET Bottle had waists and, in the case of the former, a minor contour. He was shown the additional bottles and he agreed that a number of them had waists. Mr Crone acknowledged that, whilst some of the third party bottles were similar in colour to the Contour Bottle due to the colour of the glass or the contents of the bottle, they differ significantly in other respects due to the colour of the labelling or the shape of the bottles.

119 Mr Crone expressed the opinion that the most significant element of the appearance of the Carolina Bottle from a design perspective is the overall contour shape highlighted by the low waisted shape with its thinnest diameter located in the lower section of the bottle as seen in profile. Other significant design features are the ACL labelling and the surface decoration with a wave design, although he considers that “these form part of the slower rational response from the consumer”.

120 Mr Crone said that the colour of the caps used for the Carolina Bottle – blue for regular and black for the sugar-free variety – were also a significant feature.

121 Mr Crone identified the following similarities between the Contour Bottle and the Carolina Bottle: the overall silhouette profile (which included the low waisted contour shape), the ACL labelling, and the dark brown colour of the bottles, that being a result of their contents. He also noted that the same cap colour is used for the sugar-free varieties. He identified the following differences between the two bottles: the Contour Bottle has a slightly curved neck area, the Coca-Cola logo, and vertical surface decoration, whereas the Carolina Bottle has an almost straight sided top neck area, the Pepsi logo, and the horizontal wave decoration. The colour of the caps was different in the case of the regular beverage. He considered that the similarities were significant from a design perspective because, in his opinion, colour and shape are the features of design that will be recognised by consumers upon first seeing the products in the market place. He expressed the opinion that the overall impression is similar because the “silhouette shape is broadly the same with what I regard as only a slight difference in the top of the bottle”.

122 As far as TCCC’s four trade marks were concerned, after identifying certain differences, Mr Crone expressed the opinion that an overall impression of similarity based on the shape of the silhouette persisted and that the similarity was stronger in the case of TM 1160893 and TM 1160894 because of the absence of surface decorations in the case of those trade marks. Mr Crone produced a number of overlays which enable one to make a visual comparison between the outline or silhouette of the Carolina Bottle and the Contour Bottle and each of the TCCC’s four trade marks.

123 Mr Crone was also asked by TCCC to review a file which had been provided to him and which was described by those instructing him as “Pepsi Design File”. He drew two conclusions from his review of that file. First, he said that the design directions at the outset of the project, which were to design a bottle which would distinguish the Pepsi brand from its competitors, including TCCC, were not followed. Secondly, there were no appearance attributes of the Carolina Bottle which constituted a family resemblance with the Carolina PET bottles apart from the surface decoration (i.e., the horizontal waves).

124 Mr Crone also expressed the opinions that a family resemblance between the Carolina Bottle and the Carolina PET Bottle could have been achieved, and that the Carolina Bottle did not draw on the heritage of the earlier Pepsi Swirl Bottles.

125 Mr Hunter is a design consultant who has qualifications in mechanical engineering. He has extensive experience in packaging designs, including the design of bottles and other containers for beverages and other liquids.

126 Mr Hunter disagreed with Mr Crone about the importance of colour and shape as a visual cue for product differentiation. He considered that label graphics and, in particular, branded logos, are the most important features in terms of enabling a consumer to differentiate and locate a package on a shelf. Furthermore, Mr Hunter did not agree with Mr Crone that surface texture was necessarily a less important visual cue than colour and shape.

127 Mr Hunter identified a number of design constraints in the case of a glass container for a carbonated beverage. First, he said that the container must necessarily be of a round shape and that, at what he called the geometry transition points (i.e., shape changes, such as those from the body of the bottle to the shoulders, and the shoulders to the neck of the bottle), gentle radiusing or curvature of the shape must be applied to avoid stress concentration. Secondly, he said that merchandising or marketing requirements may affect the shape of a bottle. For example, a bottle will have to fit into existing refrigeration units, or, for marketing purposes, the bottle will need to be of a certain volume. Thirdly, he said that carbonated beverage containers must be designed to be filled at very high speeds, which means, ordinarily at least, that the diameter of the bottle at the base of the shoulder must be the same as the diameter of the bottle near its base in order to prevent the bottle from tipping over. Fourthly, he said that there are design limitations associated with placing a label or texture on the bottle. Fifthly, he said that there are design constraints resulting from the type of closure (i.e., a crown seal or a screw top) to be used. Finally, Mr Hunter said that ergonomics, such as the ability to hold the bottle while consuming its contents, are relevant to design.

128 Mr Hunter said that he did not agree with Mr Crone that there is anything distinctive about the dark brown contents of the Contour Bottle or the labelling information on the back of the Contour Bottle because those features are common to other bottles.

129 Mr Hunter did not agree with Mr Crone that the low waist of the Contour Bottle is the most significant feature of its appearance. He thinks that it is distinctive in its appearance as the result of a unique combination of a number of features which it is not possible to separate out. Those features are the low waist in the body area (i.e., the minimum of the pinched waist is in the lower third of the body), the serpentine shaped neck (i.e., a curved transition from a concave shape to a convex shape), the vertical fluting in the body and neck of the bottle, the recessed convex curved label area in the shoulder of the bottle which is not fluted, and the usage of the distinctive Coca-Cola cursive script logo in the label area. Mr Hunter said that the Spencerian script logo is one of the world’s most recognisable visual symbols.

130 Mr Hunter did not agree with the suggestion that the provision of a waist “per se” was a unique feature of the Contour Bottle and he expressed the opinion that the provision of a waist to provide an ergonomic benefit in terms of holding a bottle had been used in other carbonated beverage products for a long time. He referred to one of PepsiCo’s early bottles, the “Peanut Bottle”, which had a waist. However, as TCCC pointed out, there is no evidence that the Peanut Bottle was ever sold in Australia. Mr Hunter also said that the Pepsi Swirl Bottle also had a waist.

131 Mr Hunter expressed the opinion that most of the features previously identified as distinctive features of the Contour Bottle were features of the trade marks. There are exceptions to that opinion, in that, for example, the vertical fluting is not shown in TM 1160893 and TM 1160894.

132 Mr Hunter reviewed the third party bottles identified by Mr Crone. He expressed the opinion that none of them have the five features of the Contour Bottle (see [129]) which he says in combination produce its distinctive appearance. He noted that three of the bottles – the Lucozade Bottle, the Schweppes Bottle, and the V PET Bottle – have waists.

133 Mr Hunter expressed the opinion that the most prominent and unique design feature of the Carolina Bottle, other than the Pepsi brand and logo itself, is the horizontal wave feature, which he described as a surface texturing of raised ridges or bumps located in the mid-portion of the bottle.

134 Mr Hunter could discern only one similarity between the Contour Bottle and the Carolina Bottle, and that was that they each have waists in the body of the bottle. He said that the waist in the Carolina Bottle is not a low waist like the waist of the Contour Bottle, and he considered the waist in the Carolina Bottle less “pinched”.

135 The design evidence was helpful in educating me as to the relevant design considerations in the case. However, beyond that I do not find it of great assistance in resolving the issues in this case. I prefer Mr Hunter’s evidence over that of Mr Crone, largely because, once I had been educated on what to look for, Mr Hunter’s evidence accords with my own views of the relevant issues (see Cat Media Pty Ltd v Optic-Healthcare Pty Ltd (2003) ATPR 41-933; [2003] FCA 133 at 46,937 per Branson J).

136 I should identify some particular opinions of each witness which I accept, and others that I do not accept.

137 With respect to Mr Crone’s evidence that consumers recognise colour and shape before they recognise symbols and words, I accept that evidence as to colour, but not as to shape. In the case of cola products, I accept that the colour of the labelling or writing on the bottle or caps can be a very important visual cue. I am not satisfied that the same can be said of shape. It seems to me that it will depend on the circumstances. For example, the words “Coca-Cola” in Spencerian script may be recognised as an image well before the stage at which they can be read.

138 I accept Mr Hunter’s evidence in preference to that of Mr Crone as to the significant features of the Contour Bottle and of each of TCCC’s four trade marks. It accords with my own opinion on these matters. Furthermore, it accords with TCCC’s Brand Identity and Design Standards (see [35] above).

139 Mr Crone’s overlays were helpful in showing the similarities and differences in the outlines and silhouettes of the Contour Bottle and TCCC’s four trade marks on the one hand, and the Carolina Bottle on the other. However, lining them up by reference to the top of the bottle or mark, or by reference to the bottom of the bottle or mark, seemed to produce different results and they do not give one a clear appreciation of what is seen by the naked eye, that is, that the waist of the Carolina Bottle appears to be higher up the bottle and of a more gently curving nature than the apparently lower pinched waist of the Contour Bottle. Furthermore, in view of the relevant legal principles which are discussed below, their use is limited.

140 I accept Mr Hunter’s evidence in preference to that of Mr Crone as to the weight to be accorded to the similarities and differences between on the one hand, the Contour bottle and TCCC’s four trade marks and, on the other, the Carolina Bottle.

141 With respect to Mr Crone’s evidence as to the design process for the Carolina Bottle, I have already set out my findings in relation to that matter based on the direct evidence of Mr Le Bras-Brown and Mr Cumming.

142 I have a reservation about one aspect of Mr Hunter’s evidence and that relates to his emphasis on the waist of the Pepsi Swirl glass bottle. I think that he overemphasised the waist on that bottle and that it is really a much less significant waist than the waist of the Carolina Bottle. I do not think his evidence about the distinctive features of TM 63697 differs in any material respect from the features identified by the Full Court in Coca-Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 (“Coca-Cola v All-Fect Distributors”) (see [233] below).

Matters of Consumer Behaviour

143 Dr Gibbs is a behavioural scientist and his main report is an annexure to his affidavit sworn on 16 July 2013. In his second affidavit sworn on 13 January 2014, Dr Gibbs responds to the opinions expressed by Professor Klein.

144 Dr Gibbs’ expertise is in the field of behavioural science and marketing. He has a Bachelor of Science degree in biopsychology from the University of British Colombia, a Master’s degree in cognitive psychology from the same university, and a PhD in behavioural science and marketing from the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago. Since the early 1990s, he has conducted an independent research-based consulting practice, and he states that, since 2009, he has conducted all of his work, including his academic research and university teaching, under the “auspices of his consultancy, Behavioural Science Insights”. Dr Gibbs has been a faculty member in the Melbourne Business School at the University of Melbourne since 2003 where he is Principal Fellow in Marketing and Behavioural Science and he holds the title of Associate Professor. Further details of his qualifications and experience are set out in his report.

145 Professor Klein is Professor of Marketing at the Melbourne Business School at the Melbourne University, and she has held that position since 2009. From 2012 to 2013, she was also Associate Dean of the full-time Master of Business at the Melbourne Business School. Professor Klein has a Degree of Bachelor Arts, Majoring in Psychology, from the University of South Florida, a Degree of Master of Science, Majoring in Counselling Psychology, from the State University of New York-Albany, and a PhD in Social Psychology from the University of Michigan. In her current position, Professor Klein gives lectures in decision-making and marketing management, and she has previously given lectures in consumer behaviour, advertising and marketing communications, and marketing research. Further details of her qualifications and experience are set out in her affidavit.

146 The respondents submitted that I should reject the tender of Dr Gibbs’ main report. They did not submit that Dr Gibbs’ evidence did not constitute a relevant field of expertise, or that Dr Gibbs lacked the expertise to express the opinions he set out in his report and affidavit (ss 76(1) and 79 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth); Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 55 IPR 354; [2002] FCAFC 157 (“Sydneywide Distributors v Red Bull Australia”); Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (2007) 159 FCR 397). Rather, their principal contention was that Dr Gibbs’ report was of no assistance to the Court because his starting point was the same as his finishing point. They relied on two related contentions in support of their principal contention.

147 I overruled the respondents’ objection to Dr Gibbs’ report and it was received into evidence. My reasons for that decision follow.

148 The respondents submitted that Dr Gibbs started his analysis by assuming, or acting on the basis, that TCCC’s Contour Bottle and the respondents’ Carolina Bottle were similar because both had a contoured shape. They argued that it was implicit in this starting point that consumers were likely to be misled by the similarity in shape between the two bottles. The respondents submitted that that was in fact Dr Gibbs’ conclusion, that is to say, that consumers were likely to be misled by the similarity in shape between the two bottles.

149 The respondents pointed to the title of Dr Gibbs’ report, “Marketplace Consequences of the Packaging of Pepsi in a Contour Bottle like Coke’s: The Perspective from Behavioural Science and Marketing”, in support of their contention. They also pointed to the description of Section G of Dr Gibbs’ report, “Analytical Framework: Behavioural Consequences of Attribute Overlap Across Brands”, and the fact that, in the first paragraph of that section, Dr Gibbs stated that his premise was that Pepsi has adopted a bottle similar to TCCC’s Contour Bottle.

150 The two related contentions upon which the respondents relied were as follows. First, they submitted that, if Dr Gibbs held the view that the two bottles were similar because of their contoured shape, that view was no more than Dr Gibbs’ lay opinion and it was not based on any expertise he had or any empirical evidence made available to him. The respondents submitted that the field work Dr Gibbs did in relation to two of the questions he was asked to consider was very limited and of no consequence. Secondly, they submitted that Dr Gibbs’ report was extremely confusing. For example, in his affidavit in reply, he states that Section F of his report, which is entitled “Some Key Foundational Concepts”, and Section G, to which I have already referred, did not themselves express his expert opinions on the issues in the proceeding, or should not be treated as if they were conclusions about specific issues in the case. The respondents submitted that, despite that statement, there were paragraphs in those sections in which Dr Gibbs does express opinions on specific issues in the case. They identified those paragraphs in the course of submissions.

151 I decided that the matters which the respondents raised went to the weight to be given to Dr Gibbs’ report, and not to its admissibility. Although it is not until well into his report, Dr Gibbs does set out the reasons for his view that the two bottles are similar because of their contoured shape (paragraph 78). Although he relies, in part, on his own view as to the similarities in the appearance of the two bottles, he also purports to rely on expertise he claims he has in the field of sensory psychology. It is true that his opinions are not based on empirical evidence by way of surveys or tests, but that fact is not fatal to admissibility (Australian Postal Corporation v Digital Post Australia Ltd (2013) 105 IPR 1; [2013] FCAFC 153 (“Australian Postal Corporation”) at 9, [28]). It is also true that there is a level of confusion associated with Sections F and G of Dr Gibbs’ report (and other sections for that matter), but those sections are not incomprehensible, and the matters the respondents identified were relevant to weight, and not admissibility.

152 I turn now to summarise briefly Dr Gibbs’ report and his affidavit in response to Professor Klein’s affidavit.