FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fairlight.au Pty Ltd v Peter Vogel Instruments Pty Ltd (No 2) [2014] FCA 1037

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. Costs of the application be costs in the cause.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 784 of 2012 |

BETWEEN: | FAIRLIGHT.AU PTY LTD (ACN 104 307 888) Applicant |

AND: AND BETWEEN: and: | PETER VOGEL INSTRUMENTS PTY LTD (ACN 140 173 397) First Respondent PETER VOGEL Second Respondent PETER VOGEL INSTRUMENTS PTY LTD (ACN 140 173 397) Cross-Claimant FAIRLIGHT.AU PTY LTD (ACN 104 307 888) First Cross-Respondent KFT INVESTMENTS PTY LTD (ACN 005 144 945) Second Cross-Respondent |

JUDGE: | EDMONDS J |

DATE: | 26 SEPTEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 This is an interlocutory application filed 31 July 2014 by the applicant/first cross-respondent (“Fairlight”) and the second cross-respondent (“KFT”) seeking orders that the first respondent/cross-claimant (“PVI”) or, in the alternative, its shareholders, provide security for costs as follows:

1. The First Respondent provide security for the Applicant/First Cross-Respondent’s costs of the First Respondent’s Cross-Claim in the sum of $356,250.00.

2. The First Respondent provide security for the Second Cross-Respondent’s costs of the First Respondent’s Cross-Claim in the sum of $97,500.00.

3. In the alternative, the shareholders of the First Respondent provide security for the Applicant/First Cross-respondent’s costs of the First Respondent’s Cross-Claim in the sum of $356,250.00.

4. In the alternative, the shareholders of the First Respondent provide security for the Second Cross-Respondent’s costs of the First Respondent’s Cross-Claim in the sum of $97,500.00.

5. The First Respondent pay the Applicant and Second Cross-Respondent’s costs of this application.

6. Such other orders as the Court sees fit.

2 On 12 August 2014, Fairlight and KFT, correctly in my view, abandoned the alternative orders sought in paras 3 and 4 of the interlocutory application against the shareholders of PVI. I ordered that Fairlight and KFT pay the costs of that day of two of the shareholders who, by their solicitor, appeared on the hearing.

The Evidence

3 The balance of the interlocutory application returned before me on 21 August 2014. Fairlight and KFT read and relied on three affidavits in support; the affidavit of Sven Burchartz sworn 31 July 2014 (read 12 August 2014) (Ex A); the affidavit of Jennifer Kate Rozea affirmed 11 August 2014 (read 12 August 2014) (Ex B); and a second affidavit of Ms Rozea affirmed 20 August 2014 (read 21 August 2014) (Ex C).

4 PVI read (on 12 August 2014) and relied on paras 10 and 11 of, and annexure PSV278 to, the affidavit of Peter Samuel Vogel affirmed 7 August 2014 (Ex 2); read (on 21 August 2014) and relied on the affidavit of Mr Vogel affirmed 19 August 2014 (Ex 3); and read (on 21 August 2014) and relied on the affidavit of Stuart Duncan Ross affirmed on 19 August 2014 (Ex 4), opposing the balance of the interlocutory application.

5 Mr Burchartz was required for cross-examination as were Messrs Vogel and Ross.

6 At paras 11–13 of Ex A, Mr Burchartz deposed:

11. The total estimated costs of the proceeding are as follows:

(a) Fairlight - $475,000.00.

(b) KFT - $150,000.00.

12. If Fairlight is successful in defending the cross claim and costs are awarded in Fairlight’s favour on a party/party basis, a conservative estimate is that Fairlight will recover about 65% of its actual costs which is $356,250.00.

13. If KFT is successful in defending the cross claim and costs are awarded in KFT’s favour on a party/party basis, a conservative estimate is that KFT will recover about 65% of its actual costs which is $97,500.00.

7 In chief, Mr Burchartz corrected the figure in para 12; $356,250 was not 65% of $475,000, but 75%; the correct figure, being 65% of $475,000, was $308,750.

8 The principal difficulty I have with Ex A is that it is clear that the figure in para 11(a), which is predicated upon and developed from those in paras 8(a) and 9(a), is Mr Burchartz’s “total estimated costs of the proceeding”, not just defending the cross-claim. In other words, it includes costs incurred to date and estimated future costs of Fairlight’s claim against PVI and Mr Vogel, whereas the orders sought in the interlocutory application are confined to defending the cross-claim. I therefore find Mr Burchartz’s estimate, so far as Fairlight is concerned, of no assistance at all.

9 In cross-examination, Mr Burchartz conceded that while the interlocutory application seeking security for costs was “perhaps not” brought “very late”, it was “certainly later in the proceeding than would otherwise often be the case” (T13/29–32). Mr Burchartz also conceded that as early as 29 January 2013 he was of the view that PVI was impecunious (T13/34–45).

10 The two principal shareholders of PVI are Messrs Vogel and Ross. Exhibit 3 disclosed that Mr Vogel had an excess of liabilities over assets of over $320,000; that he could not borrow money due to this state of affairs and his insufficiency of income. He was not challenged on any of this in cross-examination. If he is not impecunious, his financial position could only be described as parlous. Any surety he gave for third party debt would be worthless and he has no cash resources available to meet anything outside the vicissitudes of ordinary living.

11 The position disclosed by Ex 4 for Mr Ross is no better. His evidence was that his liabilities exceeded his assets by more than $74,000. Again he was not challenged on this in cross-examination. In the case of both Mr Vogel and Mr Ross, senior counsel for Fairlight and KFT accepted “on the evidence that there’s limited funds” (T40/21).

Fairlight and KFT’s Case

12 Fairlight and KFT’s substantive argument in support of the orders sought for PVI to provide security for their costs of defending PVI’s cross-claim is that while PVI’s cross-claim as initially framed arose out of the same matters as Fairlight’s claim and in that sense was substantially defensive, it has evolved so that PVI is now the real aggressor; it has, in substance, become a “plaintiff”. PVI’s cross-claim alleges breach of contract, breaches of statutory fair trading provisions, copyright infringement as well as statutory unconscionability. Further, it has joined Fairlight’s parent company, KFT, to the proceeding.

13 According to Fairlight and KFT, PVI’s cross-claim has also evolved in monetary terms from one which PVI would have been prepared to settle for the $200,000 it paid to Fairlight to a series of claims exceeding $3.2 million.

14 Fairlight and KFT referred me to the observations of Hislop J in Bank of Western Australia v Daleport [2010] NSWSC 1207 at [16], where his Honour said:

In my opinion, the cross claim arises out of the same matters as the claim. However, it extends beyond being purely defensive and seeks to claim substantial damages far exceeding any alleged liability to the plaintiff. That claim will involve the plaintiff incurring costs which it would not have incurred had the cross claim been confined to matters relating to the defence of the plaintiff’s claim. The first defendant has become, in substance, a plaintiff to the extent of the damages claimed by it and is, to that extent, susceptible to an order for security for costs. …

PVI’s Response

15 PVI submitted that it is not the attacker; that this is a dispute over a single contract. Fairlight says PVI breached the contract by using Fairlight’s trade mark in unauthorised ways, which gave it the right to terminate and refuse to supply any further goods or services. PVI says that Fairlight repudiated the contract and breached it by its (admitted) refusal to supply.

16 On 29 May 2013, Fairlight’s solicitors wrote:

Your cross claim deals with substantially the same issues as our client’s claim. In the case of Sydmar Pty Ltd v Statewise Developments Pty Ltd [1987] ALR 289 (at 300), an application for security for costs failed due to this reason.

17 Since that assertion in May 2013 the cross-claim has been amended to include a claim of unconscionable conduct and recently to include a prayer for an order of specific performance. PVI submitted that these amendments relate to points of law and do not change the substantive issues in dispute.

18 The claims against PVI are breach of contract, trade mark infringement, misleading conduct, and passing off. The cross-claim is purely defensive to all these, except for the copyright breach, which relates to the contract, since the contract provided that the software developed would belong to PVI and Fairlight has since admitted copying it.

19 The unconscionable conduct amendment relates to the way in which the contract was breached and the litigation conducted. Joining KFT does not raise any new issues, it just joins them as joint tortfeasor in the copyright infringement originally pleaded and being involved in the unconscionable conduct.

20 The position today is therefore still as it was on 29 May 2013.

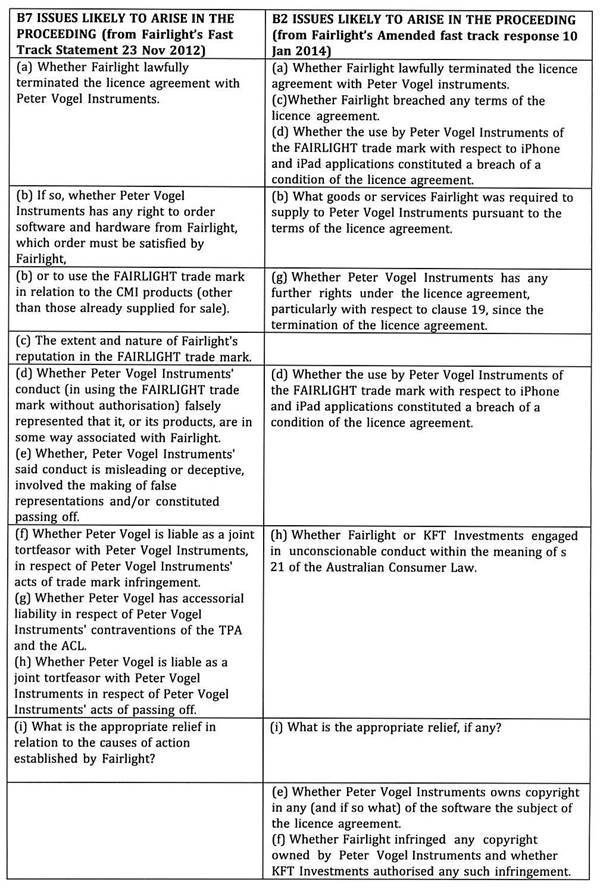

21 To illustrate its contentions, PVI prepared the following table which it incorporated in its outline of submissions:

22 According to PVI, the only issue raised in the cross-claim which has no counterpart in the claim is the issue of Fairlight’s infringement of PVI’s copyright in the software. However, this will take very little time at trial because the contract provides that the copyright transferred to PVI on payment (which is not disputed) and Fairlight concedes that they copied PVI’s software.

23 The foregoing analysis clearly demonstrates that Mr Burchartz’s assertion that “by far the bulk” of discovery, evidence and time at trial “will be spent dealing with PVI’s cross claim” is not supported by the pleadings now before the Court.

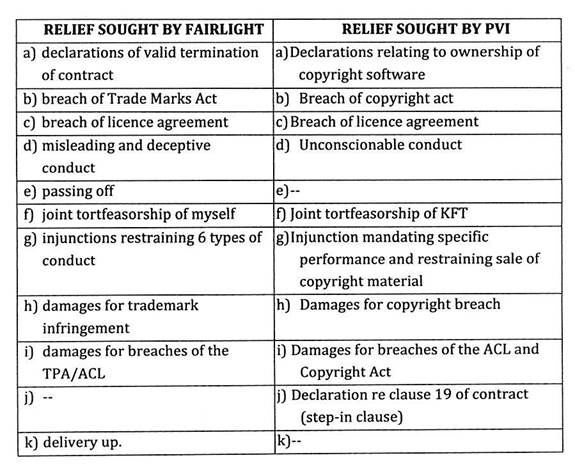

24 Senior counsel for the cross-respondents says that “Fairlight’s claim is for an injunction to prevent use of the trade mark and for a relatively limited claim for damages for breach of its trade mark”. This is also not correct. Fairlight seeks a range of remedies of similar scope to those sought by PVI:

25 The mere fact that the quantum of damages claimed by PVI against Fairlight and KFT is dramatically larger than the claim in the other direction is no indicator that PVI is the aggressor. The imbalance naturally arises from the fact that the basis on which the action has been brought against PVI gives rise to little or no damage, while the consequence of the wrongful termination has caused massive financial loss to PVI.

26 The relevant consideration is not the amount of damages on each side, it is the amount of preparatory and trial time that will be devoted to the issues raised by each side, as confirmed in Bank of Western Australia which Fairlight and KFT have cited.

27 Fairlight and KFT cite Bank of Western Australia in support of their assertion that “Peter Vogel Instruments’ claim is not just defensive. It extends beyond being defensive and prosecutes a substantial claim far exceeding Fairlight’s claim in both damages sought and the breadth of factual and legal issues”. In Bank of Western Australia, the claim was for $14.5 million and the cross-claim for $87 million. Security was ordered, not because of the disparity of damages claimed, but because the cross-claim “will involve the plaintiff incurring costs which it would not have incurred had the cross-claim been confined to matters relating to the defence of the plaintiff’s claim”.

Consideration and Analysis

28 Apart from a couple of matters which I will return to below, I think there is considerable force in PVI’s contention that its amended fast track cross-claim filed 9 December 2013 deals with substantially the same issues as Fairlight’s fast track statement filed 26 November 2012. The core issue between Fairlight and PVI is whether Fairlight was entitled to terminate its contract with PVI for the latter’s alleged unauthorised use of Fairlight’s trade mark; if it was, that will be the end of PVI’s case apart from, perhaps, its copyright infringement claim; if it was not lawfully terminated, then the correlative issue will be whether Fairlight repudiated its contract with PVI by refusing to perform the contract in accordance with its terms. From PVI’s point of view, vis-À-vis Fairlight, that is totally defensive and I include in that, PVI’s reliance on the unconscionable conduct claim against Fairlight.

29 Senior counsel for Fairlight pressed upon me the terms of para 16 of the amended fast track cross-claim filed 9 December 2013 as having nothing to do with Fairlight’s fast track statement, but I do not think that is correct. Paragraph 16 of the amended fast track cross-claim does allege failure on the part of Fairlight to deliver software to PVI, which was incomplete and not of a standard which allowed for the full and defect-free use of the CMI products by PVI or customers of PVI, and while it alleges that this is in breach of s 19 of the Sale of Goods Act 1923 (NSW), the principal allegation is that it is in breach of the contract. I do not view that as otherwise than defensive; it certainly does not render PVI, vis-À-vis Fairlight, susceptible to an order for security for costs. The order sought in para 1 of the interlocutory application is therefore dismissed.

30 The two issues which are not dealt with in Fairlight’s fast track statement but which are raised in the amended fast track cross-claim are the unconscionable conduct and the copyright infringement claims and the fact that they are alleged against KFT as well as Fairlight. Together, they are totally new and, vis-À-vis KFT substantively put PVI in the position of a plaintiff and render it susceptible to an order for security for costs. I therefore propose to consider whether in all the relevant circumstances of the present case, such an order should be made and, if so, its form and amount.

31 There are a number of circumstances of the present case which are relevant to the exercise of the Court’s discretion as to whether or not PVI should be ordered to provide KFT with security for its costs in defending PVI’s cross-claim. The starting point or premise upon which these circumstances are to be considered is that PVI is impecunious. That is common ground. Fairlight/KFT and their legal representatives have been aware of this from as early as January 2013.

32 PVI asserts that its impecuniosity is entirely attributable to the conduct of Fairlight/KFT. In summary, it asserts:

(1) By the end of 2011, PVI had paid Fairlight the full $200,000 consideration for the development of the CMI-30A even though not all the software had been completed.

(2) In January 2012, PVI ordered CC-1 cards from Fairlight. These are critical component of the CMI-30A and Fairlight is the only source. These were never delivered.

(3) On 13 April 2012, Steve Kepper, general manager of KFT, instructed Fairlight to stop all work on the CMI-30A and not to supply the CC-1 cards PVI required.

(4) It was not until 22 May 2012 that Mr Vogel discovered that Fairlight had been so instructed.

(5) Fairlight continued to refuse to perform the contract, bringing PVI’s business to a halt and destroying its ability to earn income from selling CMI-30As.

(6) PVI’s business was completely predicated on profits from sale of CMI-30As, which would be used to fund development of further products.

(7) As a result of Fairlight/KFT’s conduct, PVI has been unable to build and sell its CMI-30A product or undertake any future product developments.

33 Senior counsel for Fairlight/KFT refuted this assertion. He said that this was a case where the impecuniosity “of Fairlight [sic] began from its inception. It was underfunded to begin with – under-capitalised. And what really, Mr Vogel and his company hope is that by trading they will, in fact, improve their position and will eventually be able to turn around the company. It just so happens it didn’t occur. But it’s not to say that it’s all Fairlight’s fault”.

34 PVI’s impecuniosity may not be entirely attributable to the conduct of Fairlight/KFT, but I find that Fairlight’s termination of the contract with PVI after PVI had paid Fairlight the full $200,000 for the development of the CMI-30A even though not all the software had been completed greatly contributed to that state of impecuniosity.

35 Undoubtedly, there has been delay on the part of KFT in bringing its application that PVI provide security for KFT’s costs in defending the cross-claim. It should have been brought at the end of last year when PVI was granted leave to amend its cross-claim and join KFT. Fairlight/KFT sought to explain the delay by saying that Fairlight in particular and now KFT could not reasonably have anticipated the way the cross-claim would evolve and the breadth of the claims being pursued by PVI or the magnitude of the costs to be incurred in defending the cross-claim. That may explain away the effluxion of 12 months from the time a cross-claim was first brought in December 2012 and its amendment and joinder of KFT in December 2013, but it does not explain the delay since that latter time.

36 PVI further submitted that if it were required to provide security for KFT’s costs in defending the cross-claim, this would stultify the proceeding.

37 A company that seeks to resist an order for security on the basis that an order would stultify the proceeding bears the onus of demonstrating not just that it lacks the resources to meet any order, but also that those standing behind the company and who will benefit from the litigation lack the resources to provide the company with security. See, Bell Wholesale Co Ltd v Gates Export Corporation (1984) 2 FCR 1 at 4; Ariss v Express Interiors Pty Ltd (in liq) [1996] 2 VR 507 at 510.

38 Having regard to the unchallenged evidence of Mr Vogel (Ex 3) and Mr Ross (Ex 4) as to their financial means (see [10] and [11] above), PVI has clearly demonstrated that not only it, but its two major shareholders, holding between then 77% of PVI’s issued capital, lack the resources to provide KFT with security.

Conclusion

39 Having regard to the circumstances outlined in [31] to [38] above, I have come to the view that I should exercise my discretion by declining KFT’s application for PVI to provide security for KFT’s costs of defending PVI’s cross-claim.

40 Costs of the application should be costs in the cause.

I certify that the preceding forty (40) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Edmonds. |

Associate: