FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] FCA 926

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

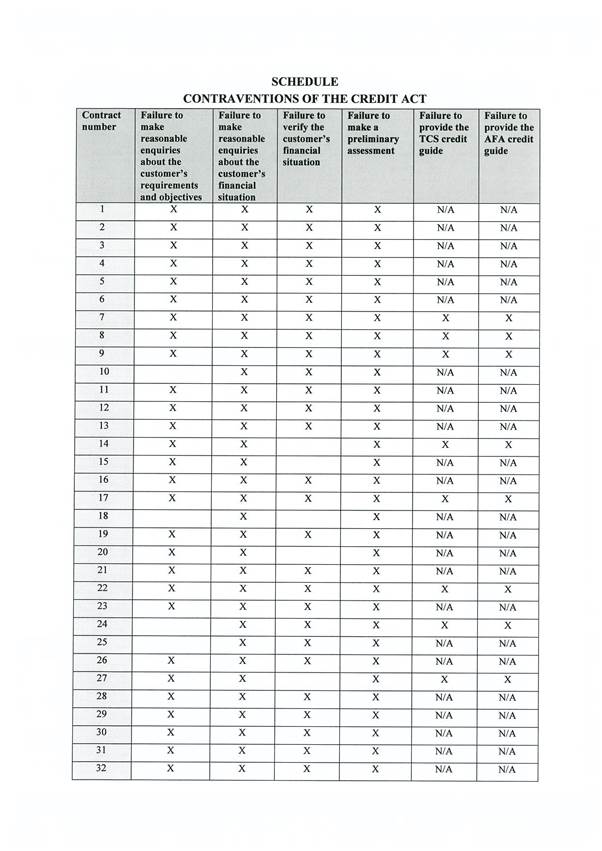

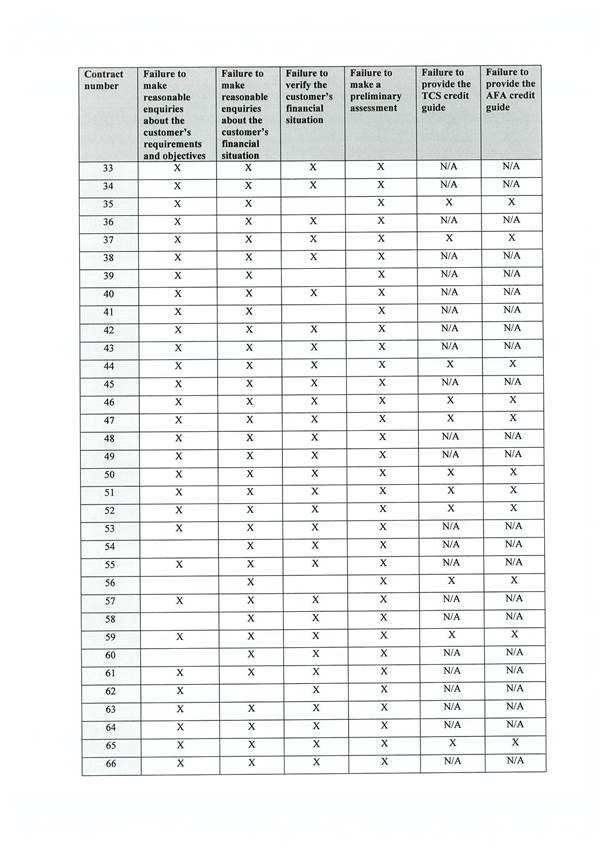

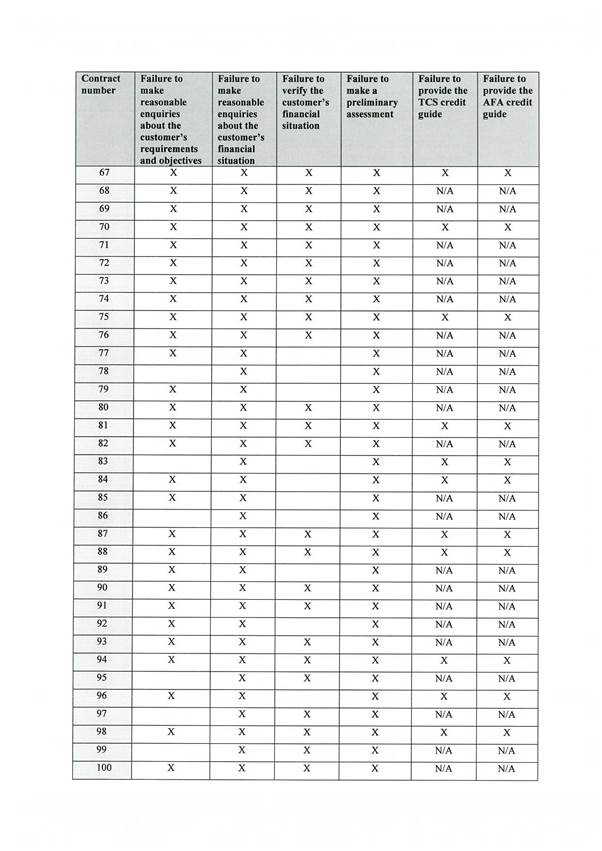

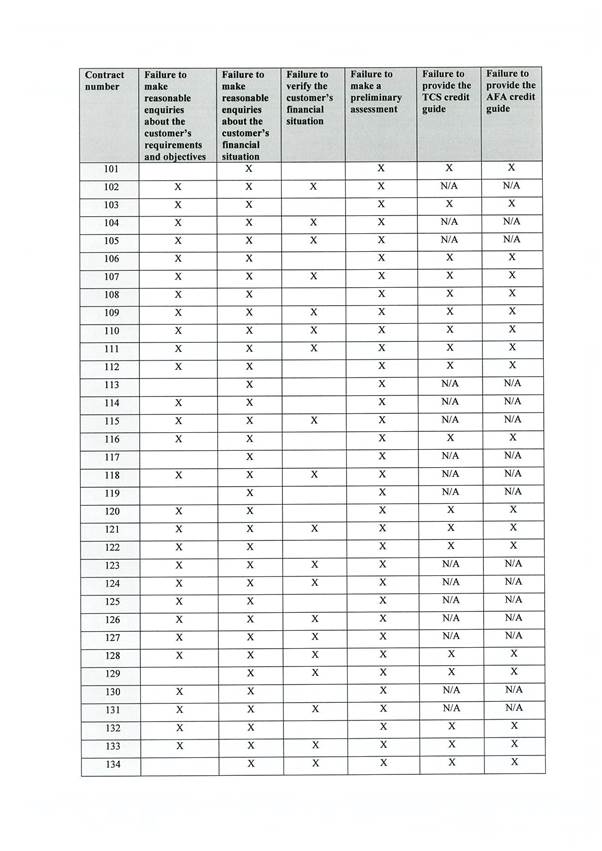

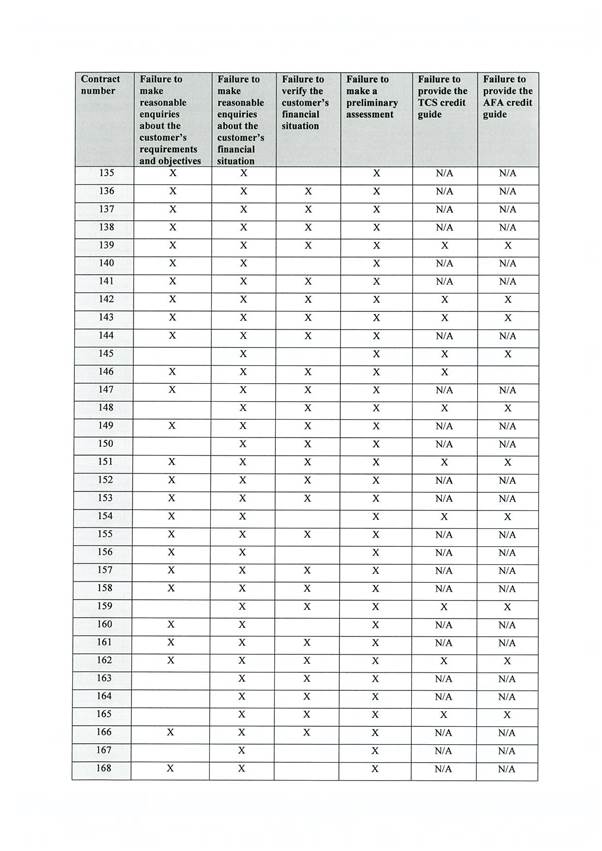

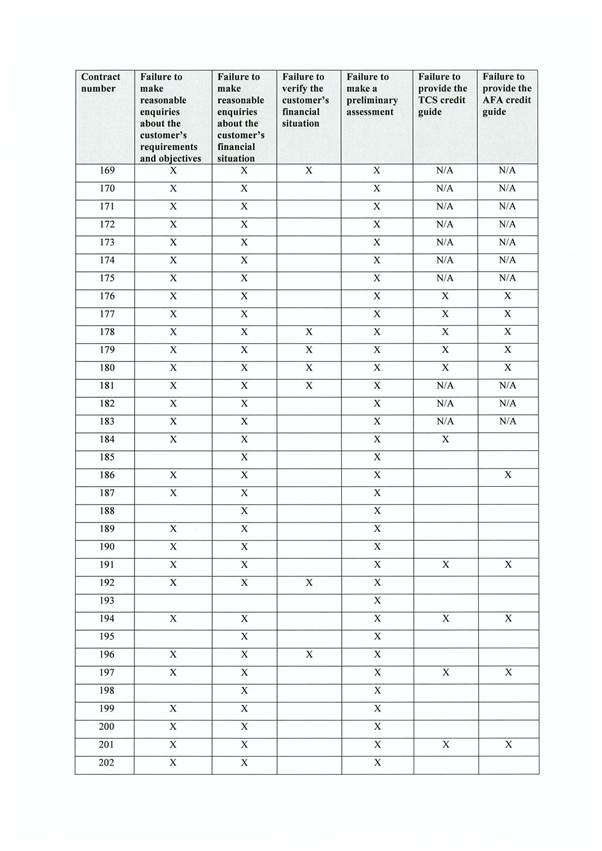

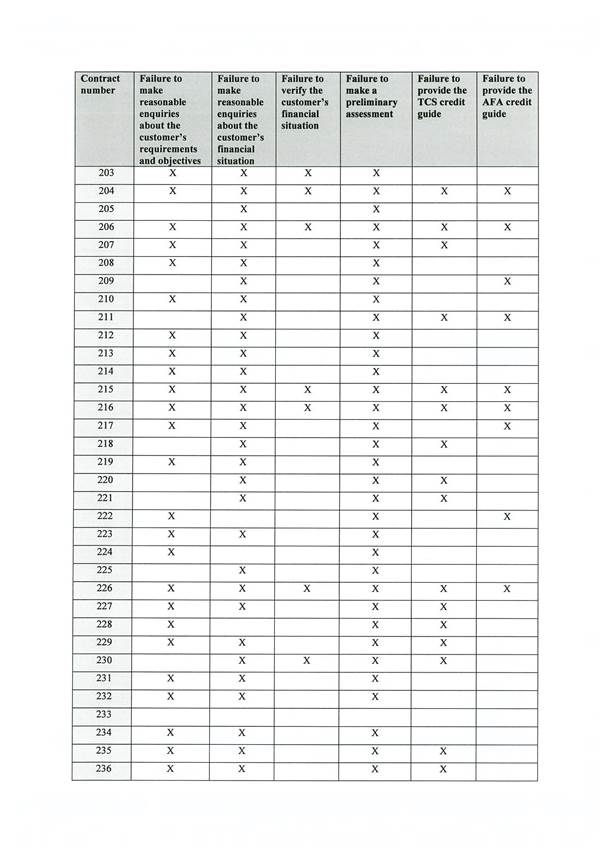

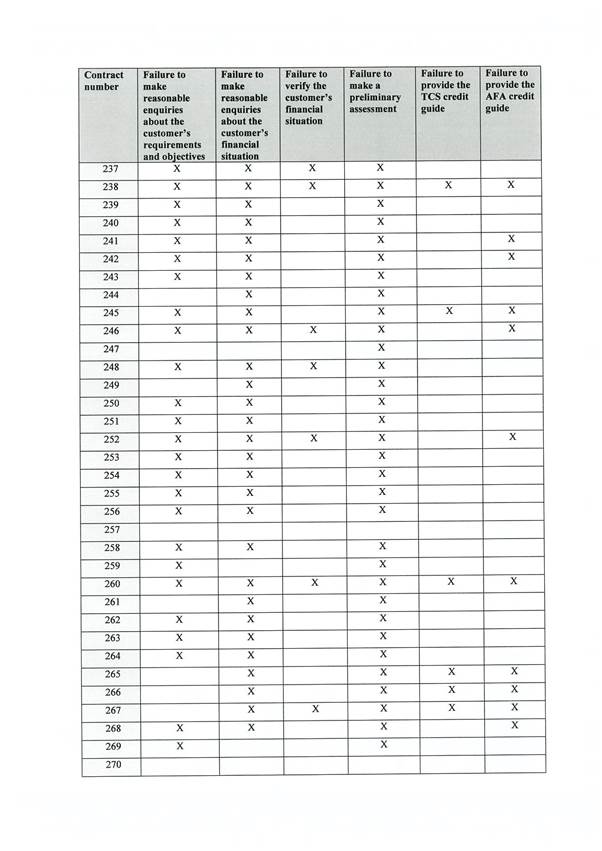

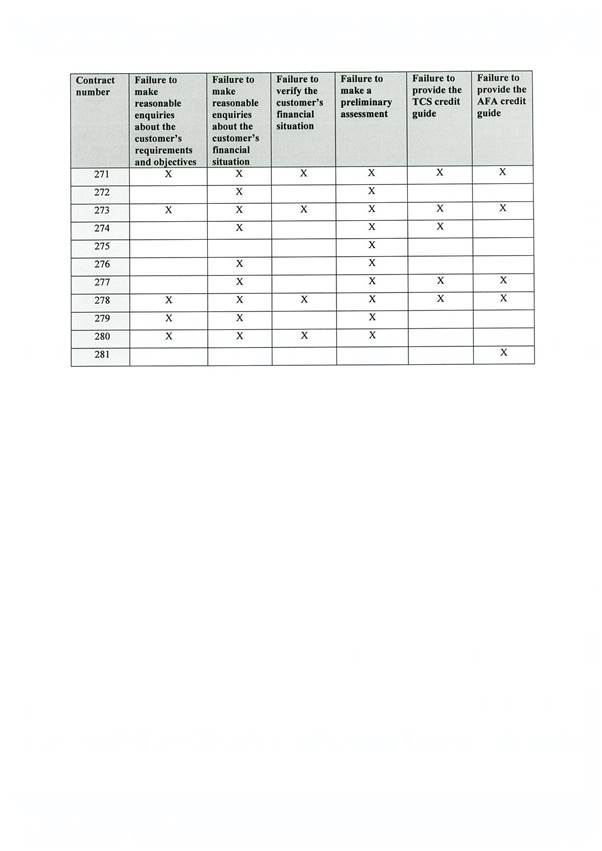

(a) "Schedule" means the Schedule attached to ASIC v The Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] FCA 926, which contains the Court’s findings in relation to each of the credit contracts the subject of allegations in the Statement of Claim. Each row of the Schedule relates to a separate credit contract, and the number in the first column of each row of the Schedule correlates to the number given to that credit contract in a table attached to the Statement of Claim, which table contains the particulars of each credit contract (including the name of the consumer who entered into the credit contract and the date of the credit contract).

OTHER MATTERS:

(a) This Order relates to numerous contraventions of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2010 (Cth) in respect of the credit contracts set out in the Schedule (references to sections are references to sections of that Act, unless otherwise stated).

(b) The Order should be read together with the reasons in ASIC v The Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] FCA 926.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

Declarations against TCS

1. Between 1 July 2010 and 17 May 2012, the First Respondent ("TCS") engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2009 (Cth) in connection with the sale of consumer credit insurance.

2. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to provide the TCS credit guide”, TCS has contravened s 113(1) by failing to give the consumer TCS’s credit guide as soon as practicable after it became apparent to TCS that it was likely to provide credit assistance to the consumer in relation to that credit contract.

3. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to provide AFA credit guide”, TCS has contravened s 126(1) by being involved in the Second Respondent (AFA) failing to give the consumer AFA’s credit guide as soon as practicable after it became apparent to AFA that it was likely to enter that credit contract with the consumer.

4. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make a preliminary assessment”, TCS has contravened:

(a) s 115(1)(c) by providing credit assistance to the consumer in respect of that credit contract without first making a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 116(1).

(b) s 128(c) by being involved in AFA entering that credit contract with the consumer without AFA first making a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 129.

5. In respect of each credit contract with an X in of the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make reasonable enquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives”, TCS has contravened:

(a) s 117(1)(a) by failing to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract before making a preliminary assessment in relation to that credit contract.

(b) s 130(1)(a) by being involved in AFA failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to that credit contract.

(c) s 115(1)(d) by providing credit assistance to the consumer in respect of that credit contract without first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to that credit contract, as required by s 117(1)(a).

(d) s 128(d) by being involved in AFA entering that credit contract with the consumer without AFA first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to that credit contract, as required by s 130(1)(a).

6. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make reasonable enquiries about the customer’s financial situation”, TCS has contravened:

(a) s 117(1)(b) by failing to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation before making a preliminary assessment in relation to that credit contract.

(b) s 130(1)(b) by being involved in AFA failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation.

(c) s 115(1)(d) by providing credit assistance to the consumer in respect of that credit contract without first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 117(1)(b).

(d) s 128(d) by being involved in AFA entering that credit contract with the consumer without AFA first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 130(1)(b).

7. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to verify the customer’s financial situation”, TCS has contravened:

(a) s 117(1)(c) by failing to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation before making a preliminary assessment in relation to that credit contract.

(b) s 130(1)(c) by being involved in AFA failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation.

(c) s 115(1)(d) by providing credit assistance to the consumer in respect of that credit contract without first taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 117(1)(c).

(d) s 128(d) by being involved in AFA entering that credit contract with the consumer without AFA first taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 130(1)(c).

Declarations against AFA

8. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to provide AFA credit guide”, AFA has contravened s 126(1) by failing to give the consumer AFA’s credit guide as soon as practicable after it became apparent to AFA that it was likely to enter that credit contract with the consumer.

9. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make a preliminary assessment”, AFA has contravened s 128(c) by entering that credit contract with the consumer without first making a preliminary assessment in accordance with s 129.

10. In respect of each credit contract with an X in of the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make reasonable enquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives”, AFA has contravened:

(a) s 130(1)(a) by failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to that credit contract.

(b) s 128(d) by entering that credit contract with the consumer without first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's requirements and objectives in relation to that credit contract, as required by s 130(1)(a).

11. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to make reasonable enquiries about the customer’s financial situation”, AFA has contravened:

(a) s 130(1)(b) by failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation.

(b) s 128(d) by entering that credit contract with the consumer without first making reasonable inquiries about the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 130(1)(b).

12. In respect of each credit contract with an X in the column of the Schedule headed “Failure to verify the customer’s financial situation”, AFA has contravened:

(a) s 130(1)(c) by failing, before making an assessment in accordance with s 129 in relation to that credit contract, to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation.

(b) s 128(d) by entering that credit contract with the consumer without first taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer's financial situation, as required by s 130(1)(c).

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 23 September 2014, the applicant file and serve any evidence upon which it seeks to rely on the penalty question.

2. On or before 14 October 2014, the second respondent file and serve any evidence upon which it seeks to rely on the penalty question.

3. On or before 4 November 2014, the applicant file and serve any evidence upon which it seeks to rely in reply on the penalty question and a written outline of the submissions it intends to make on the penalty question and on the question of the costs of the proceeding.

4. On or before 18 November 2014, the second respondent file and serve a written outline of the submissions it intends to make on the penalty question and on the question of the costs of the proceeding.

5. The matter be listed for a hearing on the penalty question on 15 December 2014.

6. Costs reserved.

7. Liberty to apply.

Dated: 26 August 2014

Schedule

Applicant Australian Securities and Investments Commission

First Respondent The Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (ACN 107 205 612)

Second Respondent: Assistive Finance Australia Pty Ltd (ACN 110 777 565)

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 958 of 2013 |

|

BETWEEN: |

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant |

|

AND: |

THE CASH STORE PTY LTD (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 107 205 612) First Respondent ASSISTIVE FINANCE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 110 777 565) Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

DAVIES J |

|

DATE: |

26 AUGUST 2014 |

|

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

|

[1] | |

|

[4] | |

|

[10] | |

|

[14] | |

|

[15] | |

|

[17] | |

|

[18] | |

|

[20] | |

|

[21] | |

|

[29] | |

|

[30] | |

|

Failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives |

[34] |

|

Failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation |

[41] |

|

[46] | |

|

[49] | |

|

[58] | |

|

[61] | |

|

[67] | |

|

[73] | |

|

[76] | |

|

[80] | |

|

[81] | |

|

[84] | |

|

[92] | |

|

[95] | |

|

[96] |

1 The first respondent (“TCS”), until it was placed into liquidation, ran a nationwide business arranging short term, low value loans, commonly known as “payday loans”, on behalf of the second respondent (“AFA”), which AFA funded. The applicant (“ASIC”) has alleged that TCS and AFA both breached their “responsible lending” obligations under Ch 3 of the National Consumer Credit Protections Act 2009 (Cth) (“the Credit Act”): AFA in relation to its activities as a “credit provider”; and TCS in relation to its activities as a “credit assistance provider”. As the relevant provisions of the Credit Act are civil penalty provisions, ASIC seeks declarations that each of the respondents has contravened those provisions, and seeks orders that they are liable to pay pecuniary penalties in respect of each contravention. ASIC has further alleged against TCS that it engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (“the ASIC Act”) in selling a consumer credit insurance policy known as the Cash Store Australian Payment Protection Plan (“CCI”). ASIC seeks declaratory relief and an order that TCS is liable for pecuniary penalties in relation to that contravention.

2 The hearing proceeded on liability only, and neither TCS nor AFA appeared. Both respondents filed notices submitting to any order that the Court may make in the proceeding. AFA, if it is found liable, wants to be heard on the question of any pecuniary penalty order and costs.

3 The contraventions are alleged to relate to the 325,756 credit contracts that TCS arranged, and AFA financed, between 1 July 2010 (when the relevant provisions of the Credit Act became operative) and 24 September 2012 (“the relevant period”). Due to the volume of contracts involved, ASIC tendered a sample of 281 contracts in order to prove the nature and extent of the breaches alleged in relation to those 325,756 credit contracts. The Court has been asked to make findings of contravention in relation to each of the 281 contracts and ASIC proposes to reserve for any penalty hearing the question of how the Court can, and should, extrapolate its findings of liability across all 325,756 contracts for the purpose of setting an appropriate penalty.

4 AFA and TCS held Australian credit licences that authorised them to engage in particular credit activities: s 35 of the Credit Act. AFA engaged in credit activities as a “credit provider”: ss 5 and 6 of the Credit Act; and TCS provided “credit assistance” to consumers: s 8 of the Credit Act.

5 AFA and TCS are not related companies but had a business arrangement under which AFA outsourced to TCS the full “servicing” of the payday loans that AFA funded. TCS described its role to ASIC, in correspondence put before the Court, as similar to that of “a mortgage manager who originates and manages loans for an arm’s length funder”.

6 During the relevant period, TCS arranged 325,756 individual credit contracts to about 52,000 customers. The loans, which were for amounts up to about $2,200, were for short-term periods between 1 and 36 days, and some of the customers had multiple or overlapping loans over the same period. TCS, until March 2012, loaned amounts up to 50% of the customer’s next scheduled net income, and from March 2012, amounts up to 35% of the customer’s next scheduled net income. Customers were asked to complete a direct debit authorisation so that the repayment, once due, would be automatically debited from the customer’s bank account.

7 From 14 August 2010 until 16 March 2012, TCS also sold CCI to its customers marketed as a “payment protection plan”. TCS sold CCI to customers in respect of 182,838 (68%) of the 268,903 credit contracts entered into in that period. TCS generally charged its customers 3.38% of the loan amount for the insurance. It collected from customers a total of $2,278,404 for the sale of the insurance, of which TCS retained $1,301,332 in commission and marketing and distribution fees. Only 110 policies resulted in a claim, and of those, only 43 received a settlement or were expected to receive a settlement. The total amount paid out on the 43 claims was $25,118.

8 In 2011 ASIC began to make inquiries of TCS regarding aspects of its business practices. In response to a non-binding suggestion from ASIC, TCS, in March 2012, temporarily ceased arranging new loans in order to conduct a review of its transaction documents and lending policies and procedures. That review led to some changes, including a new credit policy and new disclosure documents. Whilst TCS did not concede that there had been any breaches of the law, TCS acknowledged that “there was significant room for improvement”, and TCS and AFA informed ASIC that the new policies contained “much stricter tests designed to ensure that no unsuitable loans are made”. AFA also put steps into place for closer monitoring and supervision of TCS’s activities. ASIC’s case is that even with the new lending policies and procedures, TCS and AFA continued to breach their “responsible lending” obligations under the Credit Act.

9 In April 2012, ASIC commenced an investigation into the affairs of AFA and TCS pursuant to s 247 of the Credit Act, based on suspected contraventions of the Credit Act, the National Credit Code and the ASIC Act.

10 TCS provided to ASIC, in response to two notices issued by ASIC, an excel spreadsheet of the 325,756 loan contracts entered into during the relevant period. The spreadsheet recorded in respect of each contract: the branch, State, the customer name, the date the contract was entered into, the contract due date, the term of contract, the total amount of credit provided, brokerage fees, interest, the CCI amount (if any), the number of prior loans, whether the customer was on Centrelink; and the loan payment status.

11 ASIC, with the assistance of Professor Ian Gordon of the Statistical Consulting Centre at The University of Melbourne, sought to identify a statistically valid random sample of the contracts in the spreadsheet. ASIC asked Professor Gordon to identify 300 separate loan contracts, with a third from the period 1 July 2010 to 6 March 2012, a third from the period 1 January 2011 to 6 March 2012, and a third from the period 7 March 2012 to 24 September 2012. 1 July 2010 was the date that relevant provisions of the Credit Act came into effect; 1 January 2011 was the date that Ch 3 of the Credit Act came into full effect; and 6 March 2012 was selected because TCS, on or around that date, changed some of its policies and practices. ASIC then sought production from TCS of the identified loan contracts and associated documents. TCS provided the customers’ files in respect of 281 contracts and advised that it was unable to locate the customers’ files in respect of the remaining requested contracts. The files that TCS did provide frequently comprised information in respect of multiple loans including, but not limited to, the sampled loan.

12 For each of the 281 sampled contracts, ASIC reviewed the customer files that TCS provided and the information in TCS’s spreadsheet. ASIC then created its own excel spreadsheet, which was scheduled to the statement of claim. ASIC’s schedule set out the following information:

(a) the branch and State in which TCS provided the credit assistance;

(b) the customer’s name and date of birth;

(c) the loan date, contract due date, and term of the contract;

(d) the loan amount, interest, brokerage fees, total amount of credit provided to the customer after paying associated interest, fees and charges, and the repayment amount;

(e) whether the customer was on Centrelink;

(f) whether any cash card fee or pinnacle card service fee was paid;

(g) whether CCI was purchased;

(h) whether inquiries were made about the customer’s income, and whether the income was verified;

(i) whether inquiries were made about the time the customer had been employed or on Centrelink, and whether inquiries were made of the customer’s employer;

(j) whether the customer rented or owned their home, the rent or mortgage payable, the period spent at the current home address; and whether rent or mortgage liabilities had been verified;

(k) whether inquiries were made regarding the customer’s financial obligations for utilities, groceries and other expenses, and whether a TCS expenses statement was completed;

(l) whether other debt inquiries were made, and whether reasonable inquiries regarding debts were made having regard to the information available;

(m) whether the existence of any dependants was indicated;

(n) the stated purpose of the loan, if any;

(o) whether a preliminary assessment was recorded and, if so, whether rent or mortgage liabilities, utilities and other expenses were considered in the preliminary assessment;

(p) whether (if required) the TCS Credit Guide and AFA Credit Guide were provided;

(q) whether reasonable inquiries were made about the customer’s financial situation;

(r) whether reasonable inquiries were made about the customer’s requirements and objectives, and

(s) whether reasonable verification of, at a minimum, the consumer’s income and accommodation expenses was undertaken.

13 The methodology that was applied by ASIC when entering the information into the columns was as follows:

(a) Loan Date – the date the loan contract was entered into. ASIC copied this date from the TCS spreadsheet;

(b) DOB – the customer’s date of birth. ASIC entered the customer’s date of birth as shown on documents within the customer files;

(c) Contract due date – the date by which payment under the credit contract was due. ASIC copied this date from the TCS spreadsheet;

(d) Term of contract (days) – the term of the loan in days. ASIC copied this information from the TCS spreadsheet;

(e) Loan amount – total amount of credit provided to the customer (not including interest). ASIC copied this amount from the TCS spreadsheet;

(f) Interest – the amount of interest due to AFA under the loan contract. ASIC copied this amount from the TCS spreadsheet;

(g) Brokerage fees – the fees TCS charged the customer for its role as broker for AFA. ASIC copied this amount from the TCS spreadsheet;

(h) Amount of credit to consumer – the amount of credit actually paid to the customer after interest, fees and charges were deducted. ASIC ascertained this amount from its review of the contract documents and entered it into the spreadsheet;

(i) Repayment amount – the amount the customer had to repay, including interest. ASIC ascertained this amount from its review of the contract documents and entered it into the spreadsheet;

(j) Centrelink Customer – this refers to whether the customer was in receipt of Centrelink payments as their main source of income. ASIC copied this information from the TCS spreadsheet but corrected several entries which its review of the documents showed to be incorrect;

(k) Cash card fee – the amount of a fee charged for the provision of a debit card to enable the customer to access loan funds. ASIC included an amount in this column where the documents indicated the fee was charged;

(l) Pinnacle card service fee – the amount of a service fee charged to NSW customers for the provision of a debit card in lieu of broker fees. ASIC included an amount in this column where the documents indicated that the fee was charged;

(m) CCI – the amount the customer paid for CCI associated with the loan. ASIC copied this amount from the TCS spreadsheet;

(n) Income Inquiry – this column refers to whether any inquiry was made by TCS as to the customer’s income. ASIC entered a “Y” if the documents (including the loan application form, bank statement, Centrelink statement, payslip, expenses form, assessment form or any other document within the file) revealed information about the customer’s income;

(o) Verification of income – if an inquiry in respect of the customer’s income was made, this column refers to whether TCS took steps to verify the income advised by the customer. ASIC made entries as follows: “B” was entered if the income was verified by a bank statement; “C” if the income was verified by a Centrelink statement; and “P” if the income was verified by a payslip. “N” was entered if none of these documents was present or, if present, did not show the amount of income. If supporting documents showing income were more than three months older than the date of the loan contract, then “N” was entered;

(p) Time employed/on Centrelink – this refers to whether the file revealed how long the customer had been in their current job or in receipt of Centrelink payments. ASIC entered “Y” if the documents contained that information;

(q) Employer Inquiries – this refers to whether, if the customer indicated they were employed, TCS had contacted the employer to verify the customer’s income. ASIC entered “Y” if the file showed that the employer had been contacted, but not if the inquiry was made more than three months prior to the loan contract date;

(r) Renting vs owning indicated – this refers to whether the customer rented accommodation or owned their own home. ASIC entered “Y” if the documents revealed that the information had been provided by the customer;

(s) Rent payment amount – this refers to whether, if the file indicated that the customer rented accommodation, the file also indicated the amount of rent paid by the customer. ASIC entered “Y” if any document on the file (including the loan application form, expenses form, bank statement, assessment form, or a Centrelink statement which showed rent being paid by Centrepay) indicated the amount that the customer paid for rent;

(t) Mortgage payment amount – this refers to whether, if the file indicated that the customer owned a home, the amount of mortgage repayments paid by the customer was recorded. ASIC entered “Y” if any document on the file (including the loan application form, expenses form, bank statement or assessment form) indicated the amount paid by the customer for a mortgage;

(u) Period at home address – the amount of time the customer had resided at their current address. ASIC entered “Y” if the file contained this information;

(v) Rent/mortgage verification – this refers to whether TCS sought to verify the customer’s rental or mortgage payments. ASIC entered “Y” if the file included a bank statement, rental statement or other third party document that showed the amount paid for rent/mortgage;

(w) Utilities inquiries – this refers to whether an amount has been recorded on the file in respect of the customer’s utilities expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if the file contained any amount allowed for bills;

(x) Groceries inquiries – this refers to whether an amount has been recorded on the file in respect of the customer’s groceries expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if the file contained any amount allowed for groceries. “Y” was entered even if the amount appeared unreasonable (eg. $20 per month). ASIC found that it was often not possible to determine what was included in “other expenses” on an assessment form, and whether that included groceries. “Y” was entered only if it was clear that an amount for “other expenses” included groceries;

(y) Inquiries re other expenses – this refers to whether an amount has been recorded on the file in respect of the customer’s other expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if the file revealed any amount allowed for other expenses. “Y” was entered if the file contained any amounts for other expenses apart from rent/mortgage, groceries and utilities;

(z) TCS expenses statement – this refers to whether there was an expenses form on the file in relation to the loan which itemised the customer’s ongoing expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if any of the various expenses forms used by TCS over the period appeared on the file and was contemporaneous with the loan;

(aa) Other debt inquiries – this refers to whether TCS made any inquiries of the customer about the customer’s other current debts. ASIC entered “Y” if the file contained any information provided by the customer about other debts on an application form, expenses form or assessment form, but not if the only evidence was other debt repayments appearing on a bank statement, unless it appeared from the bank statement that the debt repayments had been noted, for example, by those entries having been circled;

(bb) Reasonable inquiries re debts having regard to info available – this refers to whether TCS made reasonable inquiries concerning any other debts currently owed by the customer, having regard to the information TCS had available to it, namely the information on the loan file. If the customer gave information that they had no other debts, or did not include any amounts for other debts in an application form or an expenses form, nor any amounts for “other expenses” on an assessment form, and a bank statement showed payments for other debts, ASIC entered “N” for this. Similarly, if a customer disclosed some debts but not the full extent of their debts (which was evident on a bank statement) ASIC entered “N”;

(cc) Dependants indicated – this refers to whether the file indicates that the customer had dependants. ASIC entered “Y” if the file contained this information. This was usually on the loan application form or on a Centrelink statement;

(dd) Purpose of loan stated – this refers to whether the file indicated the purpose of the loan being sought. ASIC entered “Y” if any purpose was indicated at all, but if that information appeared on the loan application form or an expenses form, only if that form was completed on the same day as, or the day before, the loan date. If the purpose for a loan, say, two weeks prior was provided, ASIC deemed this not to have been indicated for the loan in question and an “N” was entered;

(ee) Preliminary assessment recorded – this refers to whether TCS made and recorded a preliminary assessment that assessed whether the loan would not be unsuitable for the customer. ASIC entered “Y” if there was a “Credit Assessment” form on file, or any other document which considered income, expenses and the amount of the loan sought, even if the amounts entered on the form were clearly unreasonable (eg. $130 for total monthly expenses – groceries, utilities, etc – for a family of five);

(ff) Rent or mortgage on preliminary assessment – this refers to whether, if a preliminary assessment was recorded, it included the customer’s rent or mortgage repayments. ASIC entered “Y” if a figure appeared for rent or mortgage on the preliminary assessment form;

(gg) Utilities on preliminary assessment – this refers to whether, if a preliminary assessment was recorded, it included the customer’s utilities expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if a figure appeared for utilities expenses on the preliminary assessment form;

(hh) Other expenses on preliminary assessment – this refers to whether, if a preliminary assessment was recorded, it included the customer’s other expenses. ASIC entered “Y” if a figure appeared for other expenses on the preliminary assessment form;

(ii) TCS Credit Guide provided – this refers to whether TCS provided the customer with a credit guide. ASIC entered “N/A” if the loan was entered into prior to 2 October 2011 when the obligation commenced under the Act. ASIC entered “N” if no credit guide appeared on the file in the period after 2 October 2011;

(jj) AFA Credit Guide provided – this refers to whether AFA provided the customer with a Credit Guide. ASIC entered “N/A” if the loan was entered into prior to 2 October 2011 when the obligation commenced under the Act. ASIC entered “N” if no credit guide appeared on the file in the period after 2 October 2011;

(kk) Reasonable inquiries about financial situation – this refers to whether TCS or AFA made reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation. ASIC entered “Y” if each of rent/mortgage, groceries, utilities, other expenses and other debt inquiries had a “Y” entered;

(ll) Reasonable inquiries re requirements & objectives – this refers to whether TCS or AFA made reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives in obtaining the loan. ASIC entered “Y” if the purpose stated was specific enough to enable TCS reasonably to ascertain what the money was needed for. ASIC took the view that “Bills” was considered reasonable if the amount was also reasonable, with $500 as the cut-off, but that general expressions, such as “living expenses” or “personal”, were insufficient to inform TCS of the purpose and ASIC entered “N”;

(mm) Reasonable verification – this refers to whether TCS or AFA made reasonable efforts to verify:

(i) the customer’s income;

(ii) the period in which the customer had been employed or in receipt of Centrelink payments;

(iii) the customer’s employment;

(iv) whether the customer rented or owned their home;

(v) the customer’s rent or mortgage payments; and

(vi) the length of time the customer had resided at their current address.

ASIC entered “N” if the documents did not show that the items listed above had been verified.

Alleged contraventions by TCS of Pt 3-1 of the Credit Act

14 During the relevant period, TCS was required, when providing credit assistance, to comply with the requirements of ss 115, 116, 117, 118, 119 and 123 of the Credit Act and, from 2 October 2011, also with the requirements of s 113 of the Credit Act. The obligations under ss 115, 116, 117 and 123 (along with the circumstances of prescribed unsuitability in ss 118 and 119) must be understood together, and by reference to, each other.

15 Chapter 3 of the Credit Act imposes “responsible lending” obligations on credit licensees that are designed to ensure that credit licensees do not suggest, or assist a consumer to apply for, or enter into a credit contract that would be “unsuitable” for the consumer. In short compass, the “responsible lending” obligations require the credit licensee to assess whether a credit contract would be unsuitable for the consumer and proscribe the provision of credit assistance or entry into the credit contract if the contract is assessed as unsuitable for the consumer. The Credit Act provides that the credit licensee must assess the credit contract as “unsuitable” if it is likely that the consumer would not be able to repay the loan without substantial hardship or if the contract would not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives. The Credit Act also prescribes that for the purpose of making the assessment, the credit licensee must make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s objectives and requirements and financial situation, and take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation. The assessment is to be based on those inquiries.

16 The breach of any of these statutory obligations attracts a civil penalty liability.

17 Relevantly, s 115(1) provides that a licensee providing credit assistance must not provide credit assistance to a consumer by suggesting that the consumer apply, or by assisting the consumer to apply, for a credit contract with a particular credit provider, or for an increase to the credit limit unless the licensee has made, within 90 days before the day upon which credit assistance is provided to a consumer:

(a) a preliminary assessment that is in accordance with s 116(1) and covers the period proposed for the entering of the contract or the increase of the credit limit: s 115(1)(c); and

(b) the inquiries and verification in accordance with s 117: s 115(1)(d).

The same requirements apply to a licensee providing credit assistance to an existing customer remaining in a particular credit contract: s 115(2).

18 Section 116 provides that a licensee providing credit assistance must make a preliminary assessment that:

(a) specifies the period that the assessment covers; and

(b) assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered into or the credit limit is increased in that period or, if the consumer is an existing customer, if the consumer remains in the contract in that period.

19 It is implicit from the terms of s 120 that the preliminary assessment is to be recorded in writing, in that s 120 gives a consumer who has been provided credit assistance the right to obtain a written copy of the preliminary assessment from the licensee who provided credit assistance.

20 Section 117(1) relevantly requires the credit assistance provider, before making the preliminary assessment required by ss 115(1)(d) or 115(2)(d):

(a) to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract: s 117(1)(a);

(b) to make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation: s 117(1)(b); and

(c) to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation: s 117(1)(c).

Sections 118, 119 and 123 of the Credit Act

21 Sections 115, 116 and 117 must read in conjunction with, relevantly, ss 118, 119 and 123 of the Credit Act.

22 By s 118(2), the credit assistance provider must assess the credit contract, or increase in credit, as unsuitable if at the time of the preliminary assessment it is likely either that:

(a) the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship; or

(b) the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives

23 The expression “it is likely” imports as a matter of ordinary meaning “a real chance or possibility”: Marks v GIO Australia Holdings Limited (1998) 196 CLR 494 at 505 per McHugh, Hayne and Callinan JJ; Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87.

24 Furthermore, s 118 provides that for the purposes of determining whether the contract will be unsuitable, only information that satisfies both of the following paragraphs is to be to be taken into account:

(a) the information is about the consumer’s financial situation, requirements or objectives … ; and

(b) at the time of the preliminary assessment:

(i) the licensee had reason to believe that the information was true, or

(ii) the licensee would have had reason to believe that the information was true if the licensee had made the inquiries or verification under section 117.

25 In other words, the credit assistance provider must assess the credit contract as unsuitable if the credit assistance provider does not reasonably believe that the proposed credit contract will meet the consumer’s requirements and objectives or if the credit assistance provider does not reasonably believe that the consumer would have the capacity to repay the contract without substantial hardship.

26 Section 119 contains a correlative provision prescribing when a credit contract must be assessed as unsuitable for the consumer if the consumer remains in the credit contract in that period.

27 By s 123, a credit assistance provider is prohibited from providing credit assistance if the contract will be unsuitable. Subsection (2) provides that a contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if it is likely that:

(a) the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship; or

(b) the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives

28 Sections 118, 119 and 123 thus inform the content of the obligations in s 117 to “make reasonable inquiries” and “take reasonable steps to verify”. “Reasonable” inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract must be such inquiries as will be sufficient to enable the credit assistance provider to make an informed assessment as to whether the credit contract will meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives: ss 118(2)(b) and 123(2)(b). Similarly, “reasonable” inquiries about, and “reasonable” steps to verify, the consumer’s financial situation must be such inquiries and steps as will be sufficient to enable the credit assistance provider to make an informed assessment as to whether the consumer will be able to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract without substantial hardship: ss 118(2)(a) and 123(2)(a).

29 From 2 October 2011, credit assistance providers have also been required to comply with the obligations under s 113 of the Credit Act: reg 28N(5) of the National Consumer Credit Protection Regulations 2010 (Cth) (“Regulations”). Section 113 requires the provision of a credit guide “as soon as practicable” after it becomes apparent to the licensee that it is likely to provide credit assistance to the consumer.

30 The general observation can be made that prior to March 2012 (when new processes were put into place in response to ASIC’s concerns) there was a wholesale failure in process.

31 The loan application forms generally used in 2010 and 2011, if used at all, did not require any information about the customer’s expenses to be furnished on the application form other than accommodation, and an examination of the sampled contracts bears out that loan officers rarely made inquiries about expenses and rarely carried out a preliminary assessment. Of the 281 sampled contracts, 183 were entered into prior to 6 March 2012 and only five of those contracts (CN/1, CN/12, CN/53, CN/62 and CN/63) had a preliminary assessment on the file referrable to the sampled loan. It appears that as a matter of practice, credit was advanced solely or primarily on the basis of the customer’s capacity to pay the loan amount, when due, out of their next pay packet or Centrelink receipt.

32 The forms and processes did improve in 2012 but even then, of the 98 sampled loans made after 6 March 2014, there were 19 instances where there was no preliminary assessment on the file referrable to the sampled loan.

33 TCS had some sort of “safety” check process in that loan officers were provided with a checklist to tick off but the examination of the files bears out that the checklist was only occasionally completed and more often than not, all boxes would be ticked including alternate boxes (for example, both the boxes relating to the PAYG Employees and Self-Employed persons would be ticked, as in the case of CN/12), indicating that the form was treated as a mere box ticking exercise; or, in some cases, critical boxes would not be ticked (for example, none of the boxes relating to expenses would be ticked, as in the case of CN/21), indicating that the credit contract was entered into in disregard of the fact that steps required to be undertaken had not been undertaken.

Failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives

34 ASIC considered TCS to have made reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives if the file indicated the purpose for which the loan was sought and the customer’s stated purpose was specific enough to enable TCS reasonably to ascertain what the money was needed for. ASIC gave as an example that it viewed “bills” as a reasonable description if the amount was also reasonable (ASIC imposed a cut-off of $500), but viewed the descriptions of “living expenses” or “personal” as insufficient to inform TCS as to the purpose of the loan. Based on that approach, ASIC alleged that reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives, as required by ss 117(1)(a) and 115(1)(d), had not been made in relation to 227 of the sampled contracts.

35 An examination of the files of the 227 contracts in question showed that there are 196 contracts where the “purpose” for which the customer sought the loan was not filled out in the application form and there is nothing on the file to indicate that that any inquiry at all was made about the customer’s objectives or requirements in relation to the credit contract. I include in those 196 contracts, two contracts (CN/184 and CN/190) that seem to me to have been wrongly recorded by ASIC as contracts where the file indicated the purpose of the loan had been sought. As to CN/184, ASIC recorded that “shortfall” was specified on the loan application, when that application appears to relate to a subsequent loan. As to CN/190, ASIC recorded that “school fees/groceries” was specified on the loan application, when that application appears to relate to an earlier loan application for a different loan to the sampled loan. Two other contracts (CN/259 and CN/267) seem to me to have been wrongly recorded by ASIC as contracts where no purpose for the loan was provided. As to CN/259, the purpose on the application form is filled out as “lives in share house / share expenses”. As to CN/267, the purpose on an application form dated 23 May 2012 is filled out as “doctor, insulin”. That application form appears to relate to the sampled credit contract entered into on 23 April 2012 and to be misdated (as the date of next pay is stated to be 3 May 2012 and the TCS spreadsheet does not record a loan to the customer on 23 May 2012).

36 There are 28 contracts where the “purpose” for which the customer sought the loan was completed on the application form but the information provided was too general to enable the loan officers sufficiently to understand the customer’s requirements and objectives in obtaining the credit and there is nothing else on the file to indicate that that any inquiry at all was made about the customer’s objectives or requirements in relation to the credit contract. The descriptions given were:

(a) “personal” / “personal needs”: CN/39, CN/42, CN/92, CN/120, CN/240;

(b) “living” / “living expenses” / “personal – living expenses”: CN/67, CN/246, CN/248, CN/252;

(c) “monthly expenses”: CN/224;

(d) “monthly expenses – food” (when the credit amount was $907.95): CN/223;

(e) “to pay bill & live til payday”: CN/231;

(f) “bills & other” (when the credit amount was $894.50): CN/208.

(g) “lives in share house / share expenses”: CN/259;

(h) “shortfall” / “cash shortage”: CN/216, CN/253, CN/269;

(i) “travel”: CN/256, CN/262, CN/264, CN/280;

(j) “entertainment”: CN/263;

(k) “buy stuff for home”: CN/90;

(l) “shopping”: CN/214;

(m) “wedding” / “sister’s wedding”: CN/170, CN/242;

(n) “washing” (when the loan amount was $251.69): CN/79; and

(o) “buy a car” (when the credit amount was $117): CN/183.

37 I disagree with ASIC that the information provided in relation to the following three contracts was insufficient:

(a) CN/99 specified a purpose of “food” with a credit amount of $214.95. This purpose is reasonably specific and the amount of credit provided to the customer is consistent with the purpose.

(b) CN/230 specified a purpose of “work shoes” with a credit amount of $257. This purpose is reasonably specific and the amount of credit provided to the customer is consistent with the purpose.

(c) CN/274 specified a purpose of “bills” and a credit amount of $277. ASIC’s approach was to accept “bills” as a reasonable description if the amount was under $500.

38 I also consider that the information provided in respect of CN/267 was sufficient. A purpose of “doctor, insulin” with a credit amount of $164.95 is reasonably specific and the amount of credit provided to the customer is consistent with the purpose.

39 In my opinion, there was not a failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s objectives or requirements in relation to those four contracts.

40 Accordingly, having reviewed each of the 227 contracts the subject of the allegation, I am satisfied that there were 224 contracts where TCS failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives as required by ss 117(1)(a) and 115(1)(d) of the Credit Act.

Failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation

41 ASIC regarded TCS as having made reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation if TCS made inquiries about the customer’s income, and the extent of the customer’s fixed and variable expenses and other debts. Based on that approach, ASIC has alleged in relation to 268 contracts that TCS failed to determine the extent of the customer’s fixed and variable expenses and other debts and therefore, within the meaning of s 117(1)(b), failed to make reasonable inquires about the customer’s financial situation.

42 Assessing whether there is a real chance of a person being able to comply with his or her financial obligations under the contract requires, at the very least, a sufficient understanding of the person’s income and expenditure. It is axiomatic that “reasonable inquiries” about a customer’s financial situation must include inquiries about the customer’s current income and living expenses. The extent to which further information and additional inquiries may be needed in order to assess the consumer’s financial capacity to service and repay the proposed loan and determine loan suitability will be a matter of degree in each particular case.

43 A review of the files in relation to the 268 contracts in question showed that there are 26 contracts where there is nothing at all on the file to indicate that any information was provided, or any inquiry made, about the customer’s expenses in a time period referable to the sampled loan.

44 Of the remaining 242 contracts, there is some information but it was not evident from the file that the information about a customer’s expenses was complete. The information was therefore insufficient to enable a conclusion to be reached in those cases that reasonable inquiries were made about the customer’s expenses.

45 Having reviewed each of the contracts, I am satisfied that TCS in relation to 268 contracts failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation in contravention of ss 117(1)(b) and 115(1)(d).

Failure to verify the customer’s financial situation

46 ASIC took the view that there had been reasonable verification if, at a minimum, the customer’s income and rent or mortgage payments had been verified, although ASIC did not concede that only those items required verification. ASIC alleged that there were 151 contracts where there had not been reasonable verification.

47 Having reviewed the 151 contracts in question, I agree with ASIC. An examination of the files relating to those contracts showed that there was either nothing on the file to indicate that any steps were taken to seek verification of the customer’s income and/or expenses, or the supporting documentation on the file about the customer’s financial position was patently inadequate as verification.

48 Having reviewed each of the contracts, I am satisfied that TCS in relation to those 151 contracts failed to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial information in contravention of ss 117(1)(c) and 115(1)(d).

Failure to make a preliminary assessment

49 ASIC alleged that TCS failed to make the preliminary assessment required by s 116(1) of the Credit Act in respect of each of the sampled contracts on the following basis:

(a) in respect of 227 contracts, TCS failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives and therefore failed to make an adequate preliminary assessment as required by s 116(1)(b);

(b) in respect of 268 contracts, TCS failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation and therefore failed to make an adequate preliminary assessment as required by s 116(1)(b);

(c) in respect of 197 contracts, there was no preliminary assessment on the file as required by ss 116(1)(a) and 116(1)(b); and

(d) in respect of 46 of the 84 contacts where there was a preliminary assessment on the file, TCS failed to make inquiries about one or more of the customer’s rent or mortgage payments, utilities expenses or other expenses, as required by s 116(1)(b);

(e) in respect of all contracts, TCS failed to make a preliminary assessment in respect of the matters referred to in ss 118(2)(a) and/or 118(2)(b) of the Credit Act, which prescribe that the contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time of the preliminary assessment, the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship, or the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives.

50 Having reviewed each of the sampled contracts, I am satisfied that, in respect of 197 contracts, there was no preliminary assessment on the file and, accordingly, the files did not indicate that a preliminary assessment as to whether the loan would be unsuitable for the customer had been conducted.

51 Of the remaining 84 contracts where a preliminary assessment appeared on the file, 48 contracts contained preliminary assessments that were deficient. I include in these 48 contracts CN/247 and CN/259 that were incorrectly recorded by ASIC.

52 Only 36 contracts contained a preliminary assessment that considered each of rent/mortgage, utilities and other expenses. I agree with ASIC that, in respect of 31 of these contracts, TCS failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives (either because no purpose for the loan was provided or the purpose provided was plainly inadequate); and/or failed to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation (because no inquiries had been made about groceries and/or other debts).

53 There were only five contracts (CN/233, CN/247, CN/257, CN/270 and CN/281) in respect of which ASIC did not allege: a failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives; a failure to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s financial situation; a failure to verify the customer’s financial situation; a failure to undertake a (completed) preliminary assessment; or a failure to provide the TCS credit guide. Rather, ASIC alleged that each of these five contracts contravened the Credit Act because there was no consideration, in the preliminary assessment, of the objectives of the loan.

54 I do not think that CN/247 should not fall into this category of five contracts because the preliminary assessment on file appeared to me to be deficient. I am not, however, satisfied that TCS contravened the Credit Act in respect of the remaining four contracts for the reason that the amount of credit provided was, in my view, sufficiently consistent with the stated purpose to conclude that there was consideration of the requirements and objectives of the loan in the assessment that was done:

(a) CN/233 was for a credit amount of $87.00 with a stated purpose of bills;

(b) CN/257 was for a credit amount of $207.95 with a stated purpose of bills;

(c) CN/270 was for a credit amount of $47.00 with a stated purpose of groceries; and

(d) CN/281 was for a credit amount of $197.00 with a stated purpose of bills.

55 The breach of s 116 was a systemic failure in process. In a letter dated 6 March 2012, TCS made the following acknowledgement to ASIC:

Suitability screening: We will employ new methods to request, analyze and screen a customers [sic] financial situation. In the past, we have relied too much on the customers [sic] claim the loan is suitable. We understand that the regulations require us to make our own assessment of suitability. Suitability will be assessed using current bank records, current evidence of income, full disclosure of the existence of other loans, evidence of the customers uncommitted cash flow, and the family’s score using the Henderson Index as outline in the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (ISSN 1448-0530).

56 To some extent, TCS improved its practices after this date and undertook preliminary assessments with greater frequency. 79 out of the 84 contracts containing a preliminary assessment were entered into after the introduction of the new policy. However, as stated above, many of the preliminary assessments undertaken were inadequate. Further, of the 98 sampled contracts entered into after 6 March 2012, there remained 19 contracts in respect of which no preliminary assessment was undertaken despite the implementation of the new policy.

57 Having reviewed each of the contracts, I am satisfied that there were contraventions of ss 116(1) and 115(1)(c) of the Act in relation to 277 contracts.

Failure to provide the TCS credit guide

58 From 2 October 2011, TCS was required to provide a credit guide to customers as soon as it became apparent to TCS that it was likely to provide credit assistance to the consumer: s 113(1) of the Credit Act; reg 28N(5) of the Regulations. Section 113(2) sets out the requirements of such a guide and s 113(4) provides that the licensee must give the consumer the licensee’s credit guide in the manner (if any) prescribed by the Regulations. Regulation 28L deals with the manner of giving credit guides. Specifically, reg 28L(6) states that:

If a disclosure document is not given to a consumer personally, or to a person acting on the consumer’s behalf, the licensee must be reasonably satisfied that the consumer has received the disclosure document before engaging in further credit activities in relation to the consumer’s credit contract[.]

59 ASIC regarded TCS as having failed to provide the credit guide if it did not appear on the file with the documents for the sampled loan. ASIC alleged that 97 contracts fell into this category and an examination of the relevant files shows that there is no record in respect of 96 contracts that the consumer had received the disclosure document. CN/261 appears to have been wrongly included, as an examination of that file shows that the TCS credit guide appeared on the file with the documents relating to the sampled loan.

60 Having reviewed each of the contracts, I am satisfied that TCS contravened s 113(1) of the Credit Act in relation to 96 contracts.

61 I am in basic agreement with ASIC’s methodology in reviewing the sampled contracts and identifying contraventions.

62 I find that there was a systemic failure on the part of TCS to comply with its obligations under Pt 3 of the Credit Act and properly to assess whether a credit contract would be unsuitable for the consumer. There were clear deficiencies in TCS’s practices and processes, which remained even after the introduction of revised policies and procedures in March 2012. Loan officers routinely failed to make requisite inquiries and to undertake verification before arranging loans; routinely failed to inquire about purpose and objectives, and about customers’ regular expenditure and other liabilities; and, even where inquiries were made, routinely failed to verify customers’ financial position; and routinely failed to provide customers with a credit guide. Preliminary suitability assessments were either not done at all, or were not done in accordance with s 116 of the Credit Act because the inquiries and verification required to be made by s 117 were not made or were inadequate or because the assessments were deficient.

63 TCS in its 2012 credit licence annual compliance certificate signed on 30 May 2012 candidly admitted that its arrangements were deficient in various crucial respects. TCS admitted, amongst other things, that it did not have “adequate arrangements and systems in place to ensure that it complied with the conditions of its licence” and the credit legislation, and that it did not have “adequate arrangements and systems in place to maintain the competence to engage in the credit activities authorised by its licence” or “to ensure that its representatives were adequately trained and competent to engage in the credit activities authorised by its license”.

64 Despite the admissions made in that compliance certificate, on 22 October 2012 TCS contended in a letter to ASIC that it had complied with the Credit Act in all instances, stating:

There is no instance that we have identified in which staff did not comply with s 115, 117 and 118 of the [Credit] Act. In each case before making a preliminary credit assessment on behalf of [TCS] and a final assessment on behalf of [AFA], our branch associates made reasonable inquiries as to the borrower’s requirements, objectives and financial position and made a reasonable verification of that financial information. We have not identified any breach of those sections.

65 The evidence admitted to the Court in this hearing plainly contradicts that statement, demonstrating gross and systemic failures on the part of TCS to comply with the legislative requirements.

66 In summary, in respect of the sampled contracts before the Court, I find that TCS contravened the following provisions of Pt 3-1 of the Credit Act:

(a) s 113(1) in relation to 96 contracts by failing to provide the TCS credit guide to the customer;

(b) s 115(1)(c) in relation to 277 contracts by entering into a credit contract with a customer without making an assessment in accordance with s 116(1);

(c) s 115(1)(d) in relation to 224 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer’s requirements and objectives, in relation to 268 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer’s financial situation, and in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification;

(d) s 116(1) in relation to 277 contracts by failing to make an assessment in accordance with that section;

(e) s 117(1)(a) in relation to 224 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives;

(f) s 117(1)(b) in relation to 268 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about a customer's financial situation; and

(g) s 117(1)(c) in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification by a failure to take reasonable steps to verify the customer's financial situation.

Alleged Contraventions by AFA of Part 3-2 of the Credit Act

67 During the relevant period, AFA, as credit provider, was required to comply with the obligations under ss 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 in Pt 3-2 of the Credit Act, which are correlative provisions to ss 115, 116, 117, 118 and 123 in Pt 3-1 of the Credit Act. From 2 October 2011, AFA was also required to comply with the obligations under s 126 in Pt 3-2 of the Credit Act, which is correlative to s 113 in Pt 3-1 of the Credit Act: reg 28N(5) of the Regulations.

68 The breaches by TCS were also breaches by AFA as the credit provider. The fact that AFA outsourced all its functions to TCS does not exonerate it from liability for non-compliance with the Credit Act, a fact that AFA conceded to ASIC in March 2012 when it acknowledged that “outsourcing their servicing to TCS does not absolve [AFA] from complying with the law”. Additionally, the material bears out the lack of any recorded supervision of TCS by AFA. TCS, in a letter to ASIC in response to ASIC’s attempt to obtain evidence about the precise nature of the relationship between TCS and AFA, stated:

(a) Documents relating to compliance, audits/monitoring undertaken by AFA.

We have no such documents.

(b) Written directives given by AFA to TCS.

We have no such documents.

(c) Documents relating to reviews by AFA of loan contracts arranged by TCS on behalf of AFA.

We have no such documents.

(d) Correspondence (including emails) between TCS and AFA.

We have no such documents.

(e) Minutes of meetings. Documents relating to reviews by AFA of loan contracts arranged by TCS on behalf of AFA.

We have no such documents.

69 For the same reasons as TCS has been found to have contravened Pt 3-1 of the Credit Act, Pt 3-2 has been shown to have been breached by AFA in respect of the sampled contracts before the Court. Accordingly, I find that AFA contravened:

(a) s 128(c) in relation to 277 contracts by entering into a credit contract with a customer without making an assessment in accordance with s 129;

(b) s 128(d) by failing to make the inquiries and verification required in accordance with s 130, in relation to 224 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer’s requirements and objectives, in relation to 268 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer’s financial situation, and in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification;

(c) s 129 in relation to 277 contracts by failing to make an assessment in accordance with that section;

(d) s 130(1)(a) in relation to 224 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives;

(e) s 130(1)(b) in relation to 268 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about a customer’s financial situation; and

(f) s 130(1)(c) in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification by a failure to take reasonable steps to verify the customer’s financial situation.

70 From 2 October 2011, AFA was required to provide an AFA credit guide to customers: s 126 of the Credit Act; reg 28N(5) of the Regulations. ASIC alleged that AFA contravened s 126(1), a civil penalty provision, in respect of each sampled contract (within the applicable period) as it failed to give the customer a copy of its credit guide. In the alternative, ASIC alleged that AFA contravened s 126(1) in respect of 94 contracts as TCS, in its capacity as AFA’s agent, failed to provide the customer a copy of AFA’s credit guide.

71 An examination of the relevant files shows that there is no record in respect of 93 contracts that the consumer had received the disclosure document. CN/196 and CN/213 appear to have been wrongly included, as an examination of those files shows that the AFA credit guide appeared on the file with the documents relating to the sampled loan. I include in the 93 contracts CN/252 which ought to have been included by ASIC (but was not) as the AFA credit guide does not appear on the file with the documents relating to the sampled loan.

72 Having reviewed each of the contracts, I am satisfied that AFA contravened s 126(1) of the Credit Act in relation to 93 contracts.

Alleged Contraventions by TCS of Pt 3-2 of the Credit Act

73 ASIC has further alleged that TCS was knowingly concerned in, or a party to, AFA’s contraventions of civil penalty provisions in Pt 3-2 of the Credit Act and, accordingly, by s 169 of the Credit Act “is taken to have contravened” those provisions. Section 169 of the Credit Act states:

Involvement in contravention treated in same way as actual contravention.

A person who is involved in a contravention of a civil penalty provision is taken to have contravened that provision.

74 The expression “involved in” is defined in s 5 of the Credit Act as follows:

a person is involved in a contravention of a provision of legislation if, and only if, the person:

(a) has aided, abetted, counselled or procured the contravention; or

(b) has induced the contravention, whether by threats or promises or otherwise; or

(c) has been in any way, by act or omission, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in or a party to the contraventions; or

(d) has conspired with others to affect the contraction.

75 As AFA outsourced to TCS all its credit activities (other than the lending of the money), and TCS acted as AFA’s agent at all material times for the purposes of arranging the payday loan, TCS has, therefore, been directly and knowingly concerned in or a party to AFA’s contraventions of its responsible lending obligations and is liable under s 169 for those breaches. I find that TCS was “involved in” AFA’s contraventions and is thereby taken to have contravened:

(a) s 126(1) in relation to 93 contracts by failing to provide the customer the AFA credit guide;

(b) s 128(c) in relation to 277 contracts by entering into a credit contract with a customer without making an assessment in accordance with s 129;

(c) s 128(d) in relation to 224 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer’s requirements and objectives, in relation to 268 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable inquiries about a customer's financial situation, and in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification;

(d) s 129 in relation to 277 contracts by failing to make an assessment in accordance with that section;

(e) s 130(1)(a) in relation to 224 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about the customer’s requirements and objectives;

(f) s 130(1)(b) in relation to 268 contracts by failing to make reasonable inquiries about a customer’s financial situation; and

(g) s 130(1)(c) in relation to 151 contracts by failing to undertake reasonable verification by a failure to take reasonable steps to verify the customer’s financial situation.

Remedies for contraventions of the Credit Act

76 The Court may declare the contraventions pursuant to s 166 of the Credit Act and make orders pursuant to s 167 of the Credit Act that TCS and AFA each pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in such amount as the Court determines to be appropriate (subject to the maximum penalty prescribed in each civil penalty provision).

77 It is well settled that the Court has the power in circumstances such as the present to grant declaratory relief and I consider that it is appropriate to exercise that power in the present case. In Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Limited (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-438 Gibbs J enunciated the principles applicable to the award of declaratory relief as follows: the question must be “real and not a theoretical question”, the party raising the question must have “a real interest to raise it”, and there must be a proper contradictor. A public body charged with enforcing an Act has a real interest in seeking relief in respect of contravention of that Act: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Henry Kaye and National Investment Institute Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1363 (“ACCC v Kaye”) at [199] per Kenny J. In making the declarations sought, the Court both vindicates ASIC’s claim that TCS and AFA contravened the Credit Act, and provides clarity as to how comparable lending practices fit within the regulatory framework: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australian Lending Centre Pty Ltd (No 3) (2012) 213 FCR 380; [2012] FCA 43 (“ASIC v Australian Lending Centre”) at [272] per Perram J; ACCC v Kaye at [199]. Further, TCS and AFA had an interest to oppose the declaratory sought, which is sufficient to make them a proper contradictor: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378; [2012] FCAFC 56 at [30]. I am satisfied that there is utility in declaring the contraventions as the declarations will serve the public purpose of deterring similar conduct: ASIC v Australian Lending Centre at [272] per Perram J.

Unconscionable conduct: section 12CB of the ASIC Act

78 ASIC alleged that, by selling CCI to customers from 14 August 2010 to 16 March 2012, TCS engaged unconscionable conduct contrary to s 12CB of the ASIC Act.

79 During the relevant period until 31 December 2011, s 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act provided:

Unconscionable conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services to a person, engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

80 Section 12CB(2) prescribed the matters to which the Court may have regard for the purposes of determining whether a person has contravened subs (1) (see paragraph 84 below).

81 Section 12CB was repealed and replaced pursuant to schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Legislation Amendment Act 2011 (Cth) (“the Amending Act”) with effect from 1 January 2012. The new s 12CB(1) provides:

Unconscionable conduct in connection with financial services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with:

(a) the supply or possible supply of financial services to a person (other than a listed public company); or

(b) the acquisition or possible acquisition of financial services of another person (other than a listed public company);

engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

82 The new 12CC describes the matters to which the Court may have regard for the purposes of the new s 12CB. Subsections 12CC(1)(a) to (e) (set out below) replicate the matters that were contained in the repealed subs 12CB(2), and then sets out additional matters to which the Court may have regard. Section 12CC(1) provides as follows:

(a) the relative strengths of the bargaining positions of the supplier and the service recipient; and

(b) whether, as a result of conduct engaged in by the supplier, the service recipient was required to comply with conditions that were not reasonably necessary for the protection of the legitimate interests of the supplier; and

(c) whether the service recipient was able to understand any documents relating to the supply or possible supply of the financial services; and

(d) whether any undue influence or pressure was exerted on, or any unfair tactics were used against, the service recipient or a person acting on behalf of the service recipient by the supplier or a person acting on behalf of the supplier in relation to the supply or possible supply of the financial services; and

(e) the amount for which, and the circumstances under which, the service recipient could have acquired identical or equivalent financial services from a person other than the supplier; and

(f) the extent to which the supplier’s conduct towards the service recipient was consistent with the supplier’s conduct in similar transactions between the supplier and other like service recipients; and

(g) if the supplier is a corporation – the requirements of any applicable industry code (see subsection (3)); and

(h) the requirements of any other industry code (see subsection (3)), if the service recipient acted on the reasonable belief that the supplier would comply with that code; and

(i) the extent to which the supplier unreasonably failed to disclose to the service recipient:

(i) any intended conduct of the supplier that might affect the interests of the service recipient; and

(ii) any risks to the service recipient arising from the supplier’s intended conduct (being risks that the supplier should have foreseen would not be apparent to the service recipient); and

(j) if there is a contract between the supplier and the service recipient for the supply of the financial services:

(i) the extent to which the supplier was willing to negotiate the terms and conditions of the contract with the service recipient; and

(ii) the terms and conditions of the contract; and

(iii) the conduct of the supplier and the service recipient in complying with the terms and conditions of the contract; and

(iv) any conduct that the supplier or the service recipient engaged in, in connection with their commercial relationship, after they entered into the contract; and

(k) without limiting paragraph (j), whether the supplier has a contractual right to vary unilaterally a term or condition of a contract between the supplier and the service recipient for the supply of the financial services; and

(l) the extent to which the supplier and the service recipient acted in good faith.

83 Cognate provisions in other statutory contexts have been the subject of judicial determination. Those authorities make it clear that these provisions are intended to extend the concept of unconscionable conduct beyond the equitable principle to include conduct which is unconscionable within the ordinary meaning of that word: Australian Securities and Investments Commissions v National Exchange Pty Ltd (2005) 148 FCR 132 (“ASIC v National Exchange”) at [30]; Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Scully (No 3) [2012] VSC 444 (“Scully (No 3)”). For conduct to constitute “statutory unconscionability” (as opposed to general law unconscionability), it must include “a significant element of moral obloquy”: see Scully (No 3) at [26]-[31] and the authorities cited therein. Hargrave J stated that “the Court must make a value judgment as to whether to characterise the conduct with ‘the opprobrium of unconscionability’: Scully (No 3) at [31], quoting Tonto Home Loans Australia Pty Ltd v Tavares [2011] NSWCA 389 at [293]. A systemic practice directed to exploiting vulnerable consumers is capable of constituting unconscionable conduct, without the need to identify the circumstances of, or effect on, any particular consumer: ASIC v National Exchange at 140-141.

84 Notwithstanding the very limited value of the CCI to TCS customers, TCS actively encouraged its employees to overcome customers’ objections in their efforts to sell the insurance policy. In July 2011, TCS told ASIC that its policy was not to explain to borrowers the details of the insurance policy; employees were simply to advise the customer that a payment protection plan had been arranged for their benefit. It was also TCS’s practice to offer customers CCI irrespective of whether they were on Centrelink or were obtaining a loan for a very short period of time.

85 TCS employees received instruction from a document called the “Payment Protection Plan resource guide” which contained instructions on how to promote CCI to customers. For example, employees were encouraged to say “[i]t only costs 3.5% for all that coverage”. TCS acknowledged that it used this guide for training purposes. However, TCS sought to characterise its role to ASIC in selling this insurance as minimal. In a letter to ASIC dated 14 March 2012, TCS stated:

In relation to the consumer credit insurance, [TCS] is simply doing the work done by a clerk or cashier. They have been advised that no [Australian Financial Services licence] is required in these circumstances. Our activity is limited to forwarding an application form to the insurer and collecting a premium.

86 There are a number of things that can be said about that response, not the least of which is that the claim is contradicted by the resource guide itself which indicates that TCS’s involvement was much more than as an arranger. It was actively involved in marketing, promoting and selling the insurance to customers and in doing so, TCS engaged in statutory unconscionable conduct. The terms of the policies were such that insurance cover would rarely provide effective coverage for payday borrowers, as the claims rate demonstrates. Customers were charged, and TCS received, significant fees and a premium well above standard industry premium. TCS generally charged its customers a premium of 3.38% of the loan amount. The insurance provider (Accident & Health International Underwriting Pty Ltd) calculated the premium to be only 1.37% of the loan.

87 An expert’s report and expert evidence was provided by Martin Fry, an actuary, who was requested to provide an expert actuarial opinion. Mr Fry’s expert conclusion was that the TCS insurance policy as a whole represented a poor return to consumers. He also concluded that the value of TCS’s insurance policy to its customers was extremely low on any available measure, observing that 1.1% of premiums returned to TCS insurance customers as claim payments was 1/19th of the average policy value for that industry, and the loss ratio was 1.3% whereas the industry average was 25%.

88 The insurance was sold by TCS to slightly more than two thirds of its loan customers. Mr Fry summarised the TCS insurance policy coverage as follows:

|