FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Wilmink as Trustee for the Bangarra Trust v Westpac Banking Corporation [2014] FCA 872

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

KEVIN WILMINK AS TRUSTEE FOR THE BANGARRA TRUST First Applicant PETER PAALVAST AS TRUSTEE FOR THE BANGARRA TRUST Second Applicant |

|

AND: |

WESTPAC BANKING CORPORATION ABN 33 007 457 141 Respondent |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs of the proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

NSD 2580 of 2013 |

|

BETWEEN: |

KEVIN WILMINK AS TRUSTEE FOR THE BANGARRA TRUST First Applicant PETER PAALVAST AS TRUSTEE FOR THE BANGARRA TRUST Second Applicant |

|

AND: |

WESTPAC BANKING CORPORATION ABN 33 007 457 141 Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

BENNETT J |

|

DATE: |

19 AUGUST 2014 |

|

PLACE: |

SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

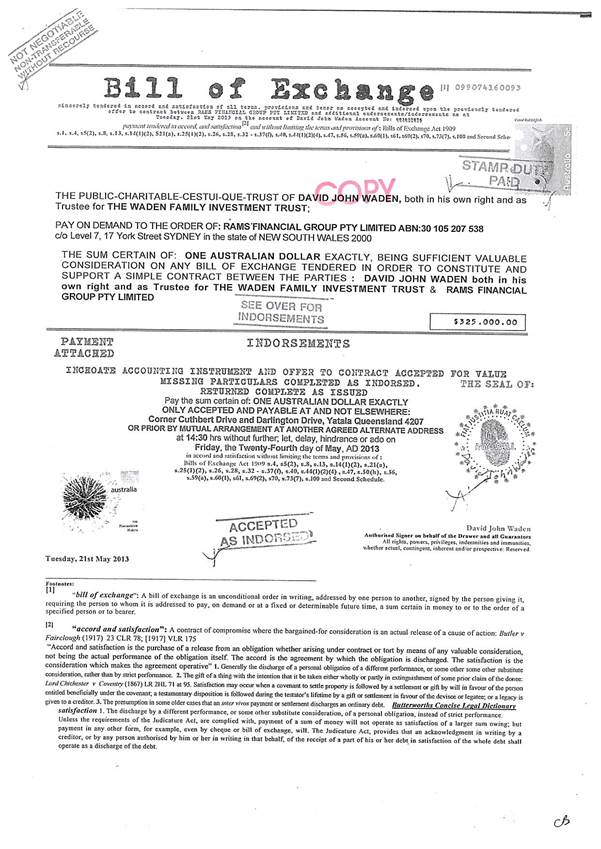

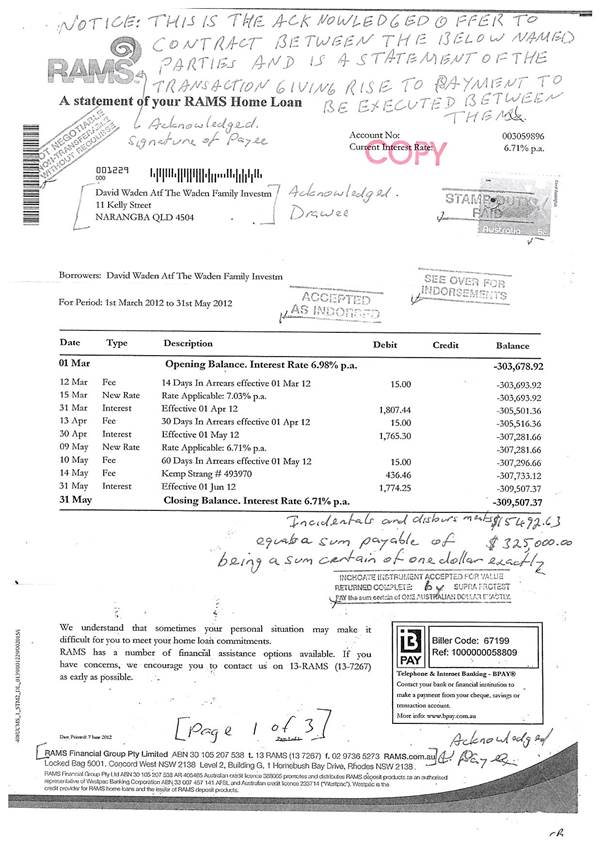

1 On 10 September 2008, David John Waden as trustee for the Waden Family Investment Trust (the Trust) entered into a Loan Agreement with RAMS Financial Group Pty Ltd (RAMS), in the sum of $289,672.00. The mortgage was secured over a property at 4 Strauss Court, Burpengary, QLD (the Property). Mr Waden, in his personal capacity, provided additional security for the entire amount of the loan by way of Guarantee and Indemnity in favour of the respondent, Westpac. RAMS is a wholly owned subsidiary of Westpac.

2 On 23 April 2012, Westpac issued default notices to Mr Waden (both in his personal capacity and in his capacity as trustee for the Trust).

3 On 4 September 2012, Westpac commenced proceedings in the District Court of Queensland (the District Court) seeking judgment for the amount of $313,563.55 being the amount of the debt plus interest, and possession of the Property. On 28 May 2013, Mr Waden filed two defences (both as trustee of the Trust and in his personal capacity), each of which read, in its entirety: ‘On 21 May 2013, I paid to the plaintiff the sum of $325,000 by Registered Post which was the amount claimed in the statement of claim plus incidentals’.

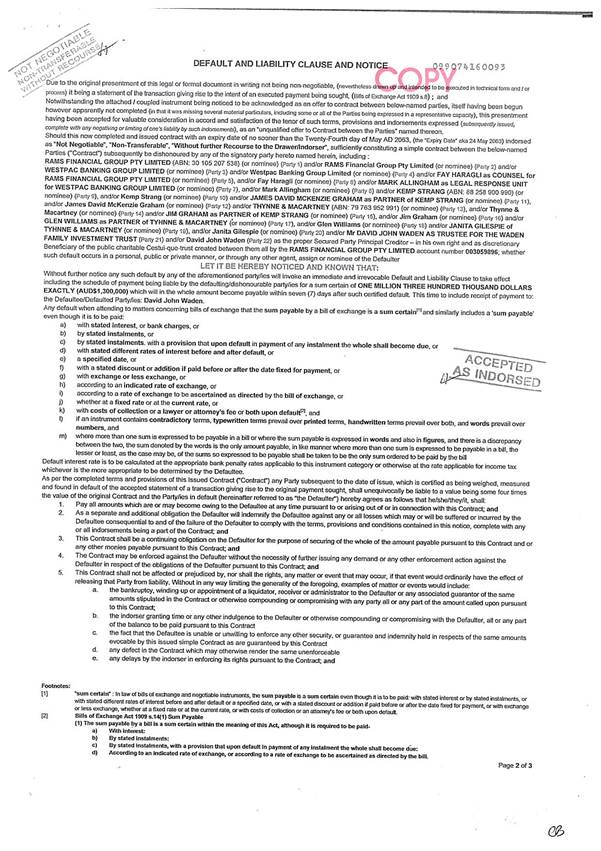

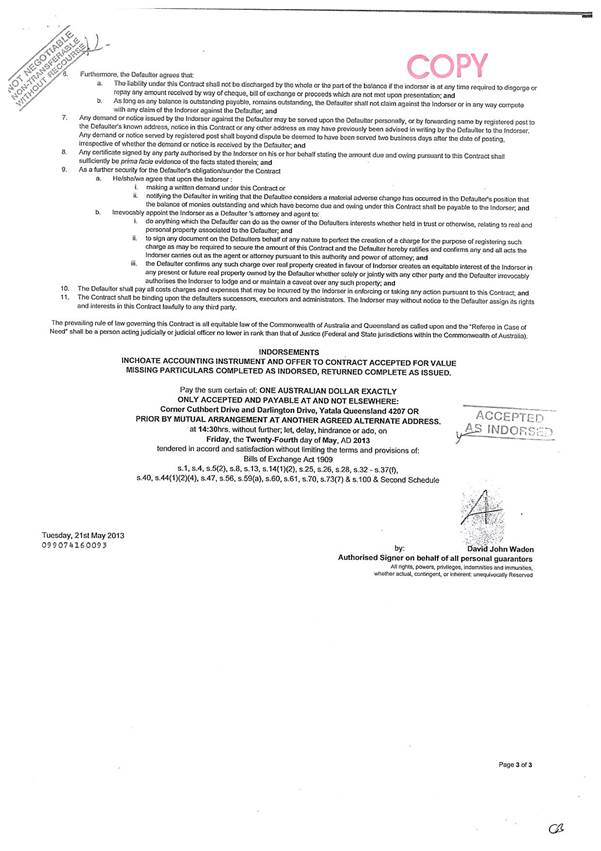

4 Mr Waden, at the hearing in the District Court, explained that he had paid the $325,000 by way of a “bill of exchange” (the Bill). On the front page of the Bill, Mr Waden appeared to direct himself (both in his own right and as trustee for the Trust) to pay RAMS the amount of one Australian dollar. The Bill further provided that the sum of $1 could only be accepted at the corner of Cuthbert Drive and Darlington Drive, Yatala, Queensland at 1430 hours on Friday, 24 May 2013, or ‘by prior mutual agreement at another agreed alternate address’. Annexed to the Bill was a home loan statement issued by RAMS to Mr Waden for the period 1 March 2012 – 31 May 2012 (the Loan Statement). A copy of the Bill with the Loan Statement is attached to these reasons.

5 Relevantly for the present case, the Bill also contained a “Default and Liability Clause and Notice” (the Default Clause), which provided that, in the event of default, the amount of $1,300,000 would become payable by Westpac within seven days of the default.

6 On 13 December 2013, Westpac was awarded summary judgment in the District Court proceedings in the amount of $345,748.08, possession of the Property and costs. An application for a stay of the judgment was dismissed on 24 January 2014. Westpac says, and it does not appear to be in dispute, that there is no evidence of any appeal having been lodged.

7 The applicants have now commenced proceedings in this Court alleging default by Westpac and seeking damages in the amount of $1,3000,000, plus interest and costs, or, in the alternative, orders that Westpac pay the applicants $975,000, discharge the mortgage over the Property and indemnify the defendants in the District Court proceedings against any further claim.

THE DISTRICT COURT PROCEEDINGS

8 The matter was argued before Clare DCJ in the District Court on 13 December 2013.

9 At the hearing, Mr Waden explained his defence to her Honour in the following terms:

DEFENDANT: The original defence was that the debt was already paid but that was charged…

HER HONOUR: You say that you have proof that the debt was paid?

DEFENDANT: Yes, I do.

HER HONOUR: All right. How was it paid?

DEFENDANT: It was paid by a bill of exchange.

…

HER HONOUR: What do you mean by that?

DEFENDANT: Well, a bill of exchange is deemed to be as good as cash. So it was tendered for payment earlier on in the year…

…

HER HONOUR: So you say you paid $325,000 to the bank?

DEFENDANT: That’s right. And the bank was given the opportunity if there was any deficiency or if they weren’t happy with it to return it and give it back to me and they didn’t. They’ve kept it. They’ve kept the consideration and ---

HER HONOUR: All right. Just – where have those – have those funds transferred to the bank?

DEFENDANT: No, it’s the same as, for example, if I wrote out a personal cheque and gave it to somebody and they’ve neglected or failed to walk down to the branch and deposit it into the branch – then has payment deemed to be made.

…

HER HONOUR: Just tell me where the money is. Where is the $325,000?

DEFENDANT: Well, it’s written on the document.

…

HER HONOUR: --- that you think you’re doing other than what seems to be fashionable with people who don’t pay loans and that is to write down on a piece of paper an amount of money and say there you go, that’s a promissory note or that’s a bill of exchange without a – a bill of exchange requires the other side to be in prior agreement for the acceptance of it. Do you have agreement – did you have the prior agreement of the bank to receive that amount – that payment in that way?

DEFENDANT: The agreement came from the bank’s lack of dispute or protest or non-acceptance or whatever if you like.

…

HER HONOUR: Did you get agreement from the bank before you gave it to them?

DEFENDANT: No, I did not get an agreement with the bank before I gave it to them. Correct, your Honour.

10 Her Honour delivered an ex tempore judgment in the matter, finding that:

At its highest, a bill of exchange or promissory note is a claim to pay or a promise to pay a specified amount. The loan agreement and the guarantee both contain undertakings to repay the loan. A promissory note or a bill of exchange to that effect in fact would not add anything to the contractual liabilities of Mr Waden and cannot amount to a repayment. The loan agreement provided for repayment by direct debit, a direct credit bank transfer, cheque or cash. It recognised that RAMS might authorise other means of payment. The uncontradicted evidence is that RAMS did not authorise payment in some other way, and that Mr Waden concedes that he received no prior authority to pay in other way [sic], and in any way other than that specified in the agreements.

Instead, he relies upon a failure of the bank to reject what was proffered – what he says was proffered as the bill of exchange. The bank, for its part, denies receipt. Mr Waden says that he has some confirmation of the bank receiving a letter from him. In any event, as I have said, the bill of the exchange, like the – what he describes as the bill of exchange does not amount to payment. The grace period under the default notice expired in June. Under clause 2 of the loan agreement, by virtue of failure to rectify the default, the entire amount of the loan became due and the bank was entitled to possession of the property. Mr Waden does not dispute that he gave the written guarantee.

…

The matter has already been adjourned from the 22nd of November to today, the 13th of December. The only matter raised in defence is the claim of a bill of exchange. I inquired of Ms [sic] Waden of his prospects of making good the default, and whilst he has said that a colleague may have funds available to him, he was vague about it and went on to say he would not press for it.

…

It is well settled that if any – if a defendant has some real prospect of resisting the claim, the matter must go to trial. Mr Waden has not challenged the validity of the loan agreement, the guarantee, or their enforceability. Sadly, he does not appear to have any prospects of meeting the debt. The loss of his house is distressing, but the application is the commercial and legal consequences [sic] of the failure to pay. The bank is entitled to get upon its security the mortgage property. It is entitled to possession of the Burpengary address by virtue of section 78 of Property Law Act and the loan agreement.

11 As noted above, Westpac was awarded summary judgment in those proceedings in the amount of $345,748.08, possession of the Property and costs.

APPLICANTS’ SUBMISSIONS

12 The applicants submit that the Waden debt had been extinguished as a matter of law and equity. The applicants say that, as the debt had been extinguished, Westpac acted in abuse of process in seeking to enforce the mortgage in the District Court.

13 The applicants put their case in the following terms:

he Loan Statement issued by RAMS to Mr Waden and/or the Trust constituted a written Demand for Payment.

Upon receiving this “Demand for Payment”, Mr Waden had an ‘unalienable right, pursuant to both s 21(a) and s 36(5) of the Bills of Exchange Act 1909 (Cth) (the Act) to negative or limit his personal liability’.

Section 25(1) of the Act permits ‘inchoate’ documents to be ‘filled up’ and completed by indorsement. According to the applicants, s 25(1) has a broader application to documents beyond bills of exchange.

Mr Waden acted in accordance with the Act in seeking to ‘negative or limit his personal liability’ by bargaining or negotiating the ‘inchoate instrument’ to a lesser value.

As the Loan Statement was ‘inchoate’, s 25(1) permitted the ‘Receiver’ to include a Default Clause.

Before the completed Loan Statement was coupled to the bill of exchange, it was transferred from Drawer (Mr Waden) to Drawee (the Waden Trust), and endorsed as being ‘not negotiable’, ‘non-transferable’ and ‘without recourse to drawer or drawee’.

When the Trust indorsed the bill of exchange and affixed it to the Loan Statement with $1, this constituted valuable consideration sufficient to support a simple contract.

The ‘now more complete instrument’ complete with the issued bill of exchange was then ‘perfected’ and issued to the first transferee (being the Bangarra Trust of which the applicants are trustees).

he bill of exchange required ‘presentment’ in accordance with s 50(2)(a) of the Act.

Westpac did not appear at the appointed time and venue for presentment.

14 The applicants submit that s 50(1) of the Act ‘totally answers what the proper outcome of today’s proceedings must be’.

15 The applicants say that ‘the clear consequence’ of those facts is that any debt allegedly owed to Westpac is discharged and further that the Default Clause in the Bill is enlivened, the terms of which direct the award of damages ‘of a quantum fourfold that of the amount originally sued for’, plus disbursements and costs, ‘in circumstances where the bargained for Consideration had been provided’.

RESPONDENT’S SUBMISSIONS

16 Westpac submits that the Loan Statement was not a demand. Even if the Loan Statement was a demand, it says that ss 21(a) and 36(5), and ss 25(1) and (2) of the Act have no application to the Loan Statement because it does not satisfy the requirements for a bill of exchange under s 8(1) of the Act, nor was it delivered in order that it may be converted to a bill of exchange.

17 Westpac also submits that the issue has already been determined in the District Court and that Mr Waden is estopped from asserting that that his debt to Westpac was discharged by the Bill. Westpac submits that the applicants, having apparently been assigned Mr Waden’s rights, are privies.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS

18 A bill of exchange is defined in s 8(1) of the Act as:

… an unconditional order in writing, addressed by one person to another, signed by the person giving it, requiring the person to whom it is addressed to pay on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time, a sum certain in money to or to the order of a specified person, or to bearer.

19 Conversely, under s 8(2) of the Act, an instrument which does not comply with the conditions stipulated in s 8(1) is not a bill of exchange.

20 The applicants rely on ss 21(a) and 36(5) of the Act in support of their assertion that Mr Waden was entitled to seek to negotiate the Loan Statement. Section 21(a) provides that: ‘the drawer of a bill, and any indorser, may insert therein an express stipulation … negativing or limiting his or her own liability to the holder’, while s 36(5) reads that: ‘where any person is under obligation to indorse a bill in a representative capacity, he or she may indorse the bill in such terms as to negative personal liability’.

21 The applicants also point to ss 25(1) and (2) as the basis upon which Mr Waden sought to convert the Loan Agreement to a bill of exchange. Subsections 25(1) and (2) provide:

(1) Where a simple signature on a blank stamped paper stamped with an impress duty stamp is delivered by the signer in order that it may be converted into a bill, it operates as a prima facie authority to fill it up as a complete bill for any amount the stamp will cover, using the signature for that of the drawer or the acceptor or an indorser.

(2) And in like manner when a bill is wanting in any material particular, the person in possession of it has a prima facie authority to fill up the omission in any way he or she thinks fit.

22 Section 50(1) provides:

(1) Subject to the provisions of this Act, a bill must be duly presented for payment. If it be not so presented, the drawer and indorsers shall be discharged.

23 The “presentment” mechanism is discussed in s 50(2):

(2) A bill is duly presented for payment which is presented in accordance with the following rules:

(a) Where the bill is not payable on demand, presentment must be made on the day it falls due.

(b) Where the bill is payable on demand, then, subject to the provisions of this Act, presentment must be made within a reasonable time after its issue, in order to render the drawer liable, and within a reasonable time after its indorsement, in order to render the indorser liable.

In determining what is a reasonable time, regard shall be had to the nature of the bill, the usage of trade with regard to similar bills, and the facts of the particular case.

(c) Presentment must be made by the holder or by some person authorized to receive payment on his or her behalf, at a reasonable hour on a business day, at the proper place as defined in this section, either to the person designated by the bill as payer, or to some person authorized to pay or refuse payment on his or her behalf, if with the exercise of reasonable diligence such person can there be found.

(d) A bill is presented at the proper place:

(i) where a place of payment is specified in the bill and the bill is there presented;

(ii) where no place of payment is specified, but the address of the drawee or acceptor is given in the bill, and the bill is there presented;

(iii) where no place of payment is specified and no address given, and the bill is presented at the drawee’s or acceptor’s place of business if known, and if not at his or her ordinary residence if known;

(iv) in any other case, if presented to the drawee or acceptor wherever he or she can be found, or if presented at his or her last known place of business or residence.

(e) Where a bill is presented at the proper place, and after the exercise of reasonable diligence no person authorized to pay or refuse payment can be found there, no further presentment to the drawee or acceptor is required.

(f) Where a bill is drawn upon or accepted by two or more persons who are not partners, and no place of payment is specified, presentment must be made to them all.

(g) Where the drawee or acceptor of a bill is dead, and no place of payment is specified, presentment must be made to a personal representative, if such there be, and with the exercise of reasonable diligence he or she can be found.

(h) Where authorized by agreement or usage, a presentment through the post office is sufficient.

CONSIDERATION

24 In summary, the applicants appear to assert that:

The Loan Statement was a demand;

Mr Waden had a right under ss 21(a) and 36(5) of the Act to seek to limit his personal liability by negotiating the demand to a lesser value;

Section 25(1) of the Act applied because the Loan Statement was an incomplete instrument;

When the Loan Statement was fixed to the Bill and given to RAMS it was perfected and the debt owed to Westpac renegotiated;

This renegotiated debt owed to Westpac was discharged by reason of s 50(1) of the Act because Westpac failed to appear at the time and place stipulated in the Bill;

The failure to appear also triggered the Default and Liability clause such that Westpac became liable to pay Mr Waden the amount of $1,300,000; and

Mr Waden has assigned his rights to the applicants.

25 Westpac submits that the Loan Statement was not a demand, but it has not developed this submission any further.

26 Westpac also submits that ultimately it does not matter whether or not the Loan Statement was a demand, as the Loan Statement is not a bill of exchange. The Loan Statement has the appearance of a statement that one might receive from a financial institution. It is on a RAMS letterhead and addressed to Mr Waden. The Loan Statement details the balance of the loan, and fees and interest payments on the loan during the relevant period. Critically for the applicants’ case, the Loan Statement is not signed (despite assertions by the applicants that the RAMS letterhead constitutes a signature) and, while noting that the account in arrears, it contains no ‘unconditional order’ that the arrears amounts be paid on demand.

27 The Loan Statement does not satisfy the conditions of s 8(1) of the Act. Accordingly, it is not a bill of exchange (s 8(2)).

28 The applicants submit that even if the Loan Statement was not a bill of exchange, it was an ‘inchoate’ document under s 25 of the Act and therefore could be ‘fill[ed] up’ and converted into a bill of exchange. However, having regard to the requirements of s 25, it is clear that the Loan Statement is not a ‘simple signature on a blank stamped paper’ and it is not ‘stamped with an impress duty stamp’, apart from an Australian 5 cent stamp which either Mr Waden or the applicants appear to have affixed themselves. Therefore the Loan Statement is not an ‘inchoate instrument’ under s 25 and was not able to be ‘fill[ed] up’ and thereby converted to a bill of exchange.

29 Section 50 deals with the presentation of bills of exchange. I am of the view that the Loan Statement was not a bill of exchange under s 8(1) of the Act and, further, was incapable of conversion to a bill of exchange under s 25. Given that the Loan Statement was not and could never be a bill of exchange, s 50(1) could have no application.

30 The above arguments appear to have been previously considered in Bertola v Australian and New Zealand Banking Corporation [2014] FCA 609 (Bertola) and Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Sproule [2012] FMCA 1188 (Sproule), each of which dealt with facts and issues significantly similar to the present case. The applicants submit that these cases were wrongly decided.

31 In Sproule, a debtor (Mr Sproule) attempted to use a bill of exchange to satisfy a debt to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). Judge Lloyd-Jones rejected Mr Sproule’s argument that a bill of exchange with a face value of $1 could be used to satisfy his debt to the ATO, noting (at [23]) that:

… logic as to why the [Deputy Commissioner of Taxation] would accept that document is completely unexplained …

32 Judge Lloyd-Jones concluded (at [24]) that:

The basic concept and mechanism of this financial instrument appears to be totally misunderstood or misconceived … The use of a bill of exchange proposed by Mr Sproule is either a complete misunderstanding of the use of the instrument or some cynical ploy to avoid the debt. In the absence of any logical explanation of how Mr Sproule intends to resolve his indebtedness to the ATO this whole approach for this form of settlement is misconceived and should be dismissed.

(emphasis added)

33 Similarly in Bertola, Barker J considered the question on submissions advanced by Mr Paalvast, one of the applicants in this proceeding. His Honour rejected the submissions as ‘not only hopeless but nonsense’ and dismissed the application. The same observations could well apply to this case.

34 In any event, it was an essential step in the reasoning in the District Court Proceedings that a bill of exchange was not a method of payment permitted by the Loan Agreement. Thus, this issue has already been decided by a court on a final basis and the parties are bound by that decision by reason of issue estoppel: Port of Melbourne Authority v Anshun Pty Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 589 at 597 per Gibbs CJ, Mason and Aickin JJ. I accept Westpac’s submission that the applicants, through the purported assignment, are privies and are therefore similarly estopped (see Ramsay v Pigram (1968) 118 CLR 271 at 279 per Barwick CJ).

35 Additionally, given that substantially similar arguments have been advanced and determined in Sproule and Bertola, it may be that the present proceedings also constitute an abuse of process, even if issue estoppel strictly so-called is unavailable. The High Court in Walton v Gardiner (1993) 177 CLR 373 held (at 393 per Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ) that:

… proceedings before a court should be stayed as an abuse of process if, notwithstanding that the circumstances do not give rise to an estoppel, their continuance would be unjustifiably vexatious and oppressive for the reason that it is sought to litigate anew a case which has already been disposed of by earlier proceedings.

(citations omitted)

36 This principle has been held to apply to proceedings dealing with identical facts put in a different legal context, namely, an action against a new defendant: Abriel & Ors v Bennett [2003] NSWSC 368 per Adams J citing Rippon v Chilcotin Pty Limited & Ors [2001] NSWCA 142 per Handley JA (with whom Mason P and Heydon JA agreed).

CONCLUSION

37 The Act does not apply. The applicants’ reliance on the Act and their attempt to convert a “run of the mill” bank statement into a bill of exchange is at best, misguided; at worst, disingenuous. Further, Mr Waden and the applicants are bound by issue estoppel.

38 The application is dismissed with costs.

|

I certify that the preceding thirty-eight (38) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Bennett. |

Associate:

19 August 2014