FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

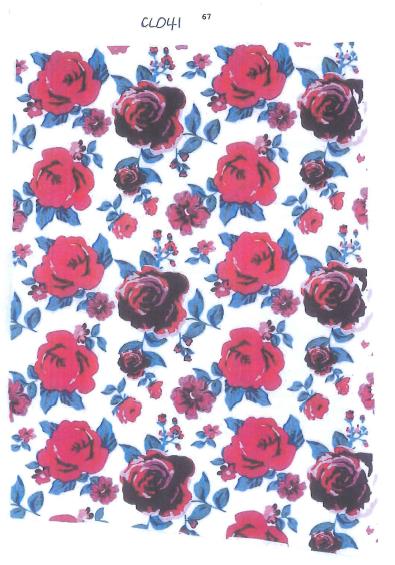

Seafolly Pty Limited v Fewstone Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 321

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| SEAFOLLY PTY LIMITED (ACN 001 537 748) Applicant | |

| AND: | FEWSTONE PTY LTD (ACN 010 496 465) Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

1. The respondent has infringed or authorised the infringement of the applicant's copyright in the copyright works identified in paragraphs 8, 11 and 13 of the reasons for judgment given by Justice Dodds-Streeton on 1 April 2014 (Copyright Works).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The respondent pay the applicant damages in the sum of $250,333.06.

3. The respondent whether by itself, its directors, employees, servants, agents or any of them be restrained from:

(a) reproducing or substantially reproducing the Copyright Works or authorising such conduct;

(b) manufacturing, importing for sale, selling, or by way of trade, offering and exposing for sale, or exhibiting in public:

(i) items manufactured from the fabric used to manufacture the Respondent’s Garments (as defined in paragraph 15 of the third further amended fast track statement); and

(ii) the Respondent’s Garments;

(c) advertising, marketing and promoting:

(i) items manufactured from the fabric used to manufacture the Respondent’s Garments; and

(ii) the Respondent’s Garments; and

(d) disposing of possession of:

(i) the Respondent’s Garments; and

(ii) the materials used to create the Respondent’s Garments

other than in accordance with order 5 below;

4. Order 3 be stayed until 4 pm on 8 April 2014.

5. The respondent whether by itself, its directors, employees, servants, agents or howsoever deliver up to the applicant:

(a) any materials bearing reproductions of the design on the fabric used to manufacture the Respondent's Garments or any remaining stock of such fabric; and

(b) any remaining stock of the Respondent's Garments

in its possession, custody or control and by 4pm on 15 April 2014 verify on affidavit its compliance with this order.

6. Costs of the proceeding be reserved.

7. The matter be listed for directions at a time convenient to the Court and the parties after 18 April 2014.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 488 of 2012 |

| BETWEEN: | SEAFOLLY PTY LIMITED (ACN 001 537 748) Applicant |

| AND: | FEWSTONE PTY LTD (ACN 010 496 465) Respondent |

| JUDGE: | DODDS-STREETON J |

| DATE: | 1 APRIL 2014 |

| PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 In this proceeding, the applicant, Seafolly Pty Limited (“Seafolly”), which designs, manufactures and sells swimwear and beachwear, alleges that the respondent, Fewstone Pty Ltd (“Fewstone”) trading as City Beach Australia (“City Beach”), which also designs, manufactures and sells swimwear and beachwear, has infringed Seafolly’s copyright in three artistic works. The works in question are the following, which Seafolly used in the manufacture of its swimwear:

(a) the English Rose artwork;

(b) the Covent Garden artwork; and

(c) the Senorita artwork.

2 Seafolly alleges that it owns the copyright in each of the above artworks pursuant to an assignment from a designer, Longina Phillips Designs Pty Ltd (“Longina”), or as author.

3 Seafolly alleges that a substantial part of each of its above artworks was, contrary to ss 14, 31(1)(b)(i) and 36 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the Copyright Act”), reproduced without its licence in a material form by a corresponding print or embroidery used to manufacture various City Beach beachwear garments. In particular, Seafolly alleges that:

(a) City Beach’s Fiesta Rosette print (and identical Fiesta Rosario print) (collectively, “the Rosette print”) on the fabric used to produce various City Beach beachwear garments reproduced in a material form a substantial part of Seafolly’s English Rose artwork.

(b) City Beach’s Fiesta Sienna print (“the Sienna print”) on the fabric used to produce various City Beach beachwear garments reproduced in a material form a substantial part of Seafolly’s Covent Garden artwork.

(c) City Beach’s Richelle embroidery on the fabric used to produce various City Beach beachwear garments reproduced in a material form a substantial part of Seafolly’s Senorita artwork.

4 Seafolly alleges that City Beach’s reproduction of a substantial part of each of its copyright works was not the result of independent creation but was due to copying of the Seafolly artworks from Seafolly garments which, as City Beach conceded, it purchased and used to instruct its designers.

5 Seafolly alleges that City Beach also infringed its copyright pursuant to ss 14, 37 and 38 of the Copyright Act by directing the manufacture in China of garments imprinted with or incorporating the Rosette, Sienna and Richelle artworks, which City Beach imported and sold in Australia with actual or constructive knowledge that the making of the article would have constituted an infringement of Seafolly’s copyright had it been made in Australia by the importer.

6 Seafolly sought remedies including compensatory damages, damages for damage to its reputation, additional damages, declarations, injunctions and orders for delivery up.

7 It is convenient to set out photocopies of Seafolly’s artworks and the corresponding City Beach prints or embroidery which allegedly infringed Seafolly’s copyright.

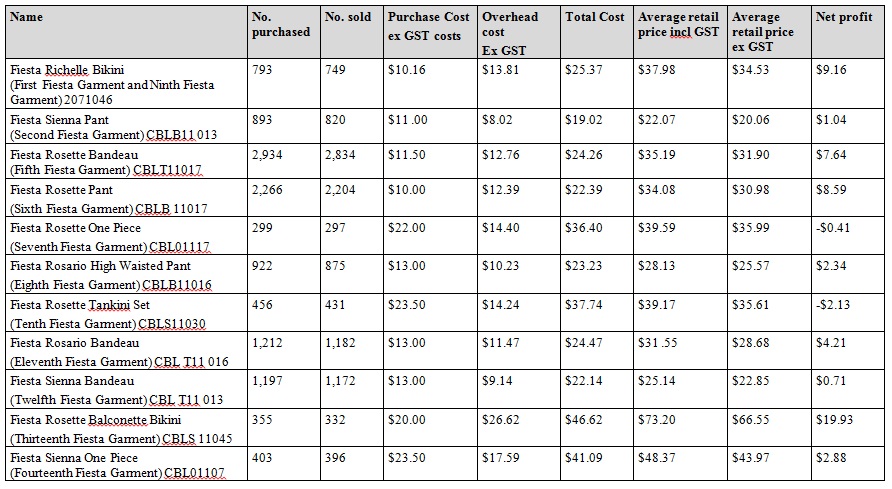

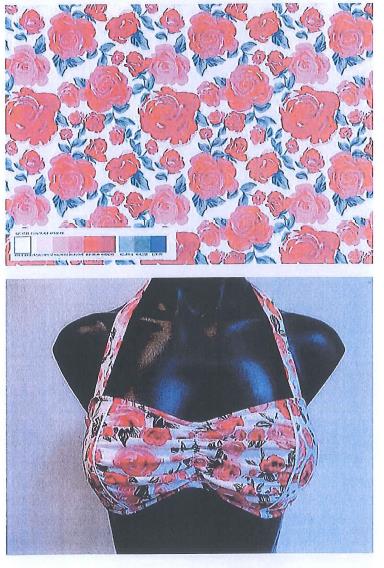

Seafolly’s English Rose artwork

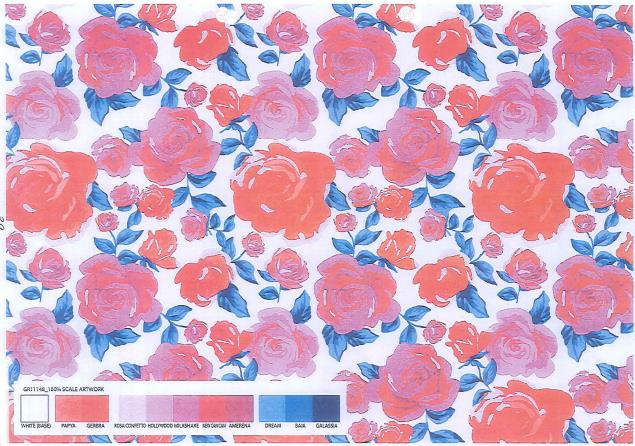

8 The English Rose artwork in white and black colour ways are set out below:

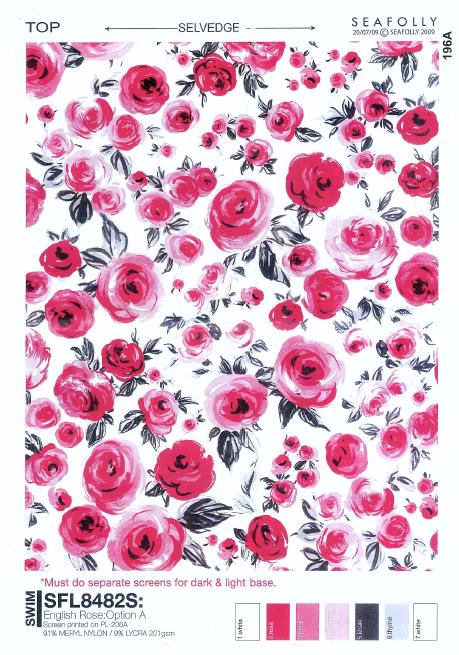

City Beach’s Rosette print

9 Paper representations of the strike-offs of fabric bearing City Beach’s Rosette print (in white and black colour ways) and copies of the print production sheets, both produced in late June 2011, appear below:

10 Paper representations of the strike-offs of fabric bearing City Beach’s Rosette print produced in November 2011 appear below:

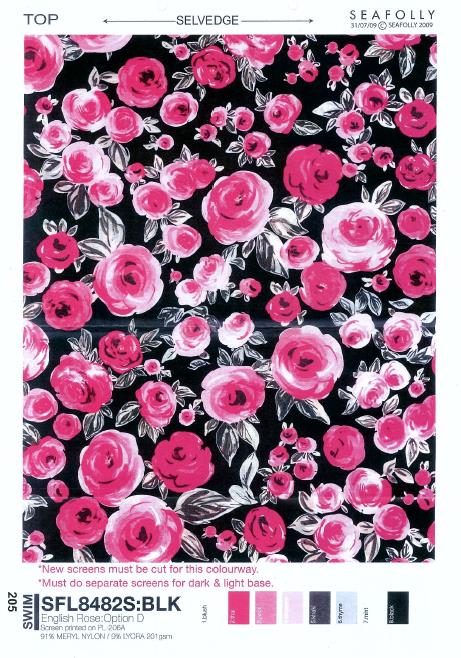

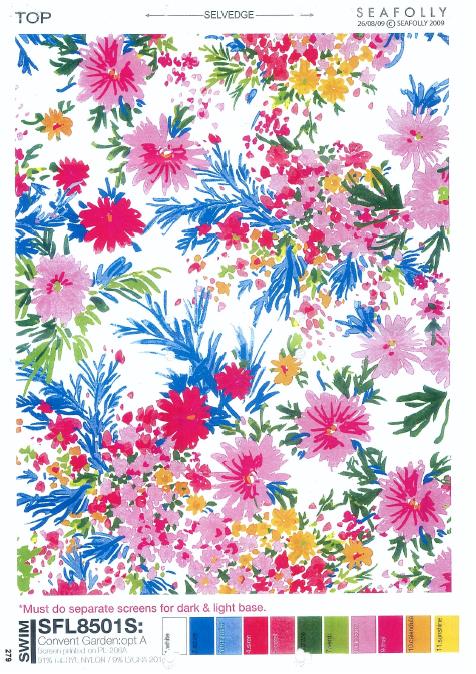

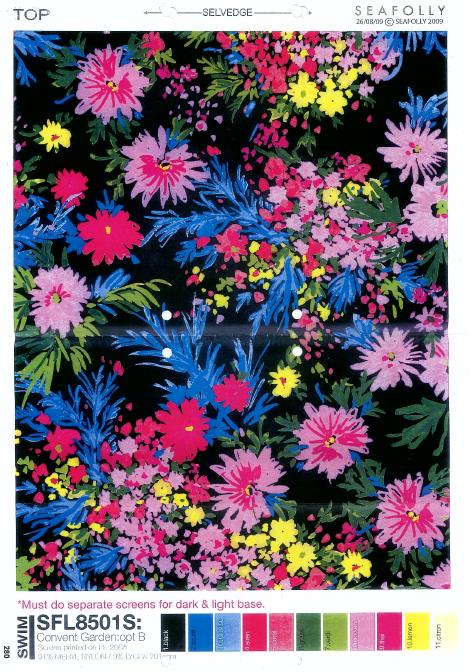

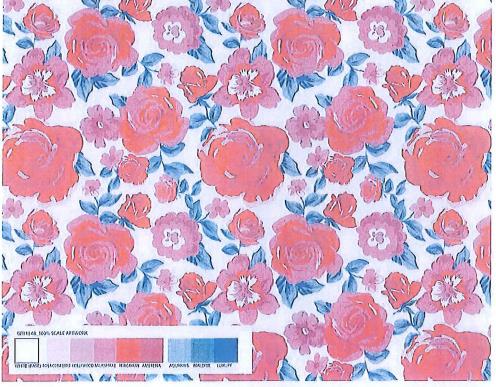

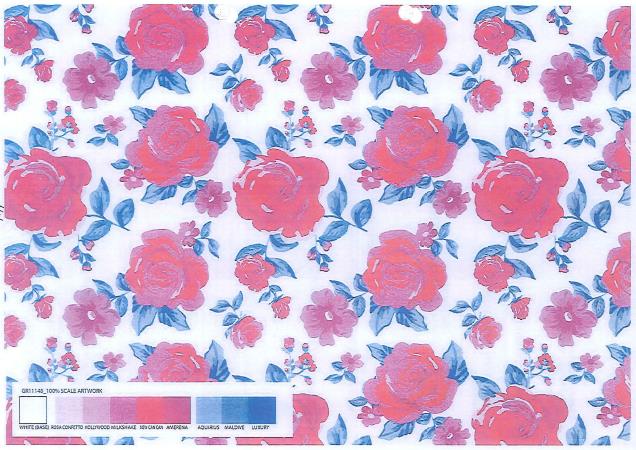

Seafolly’s Covent Garden artwork

11 Seafolly’s final Covent Garden artwork in white and black colour ways is set out below:

City Beach’s Sienna print

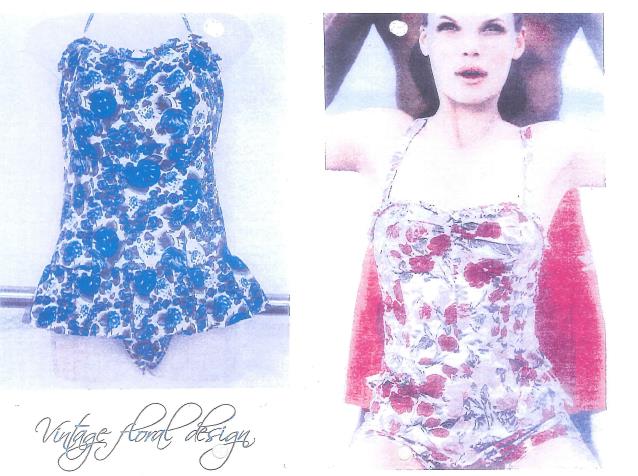

12 Paper representations of the strike-offs of City Beach’s Sienna print appear below:

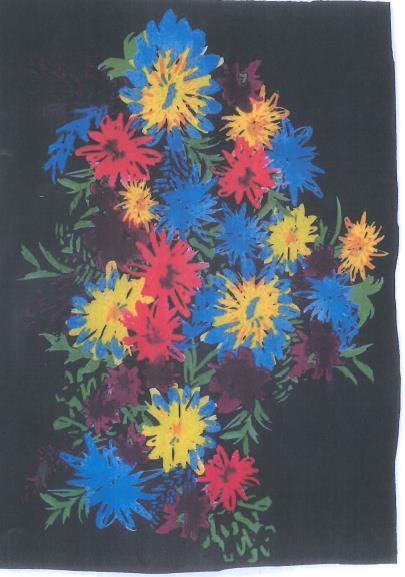

Seafolly’s Senorita artwork

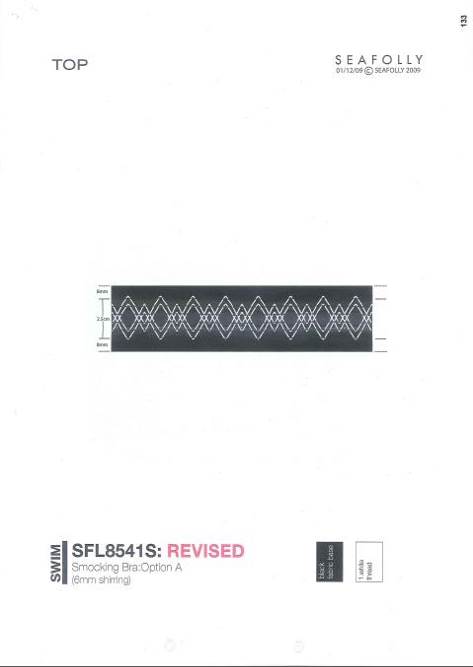

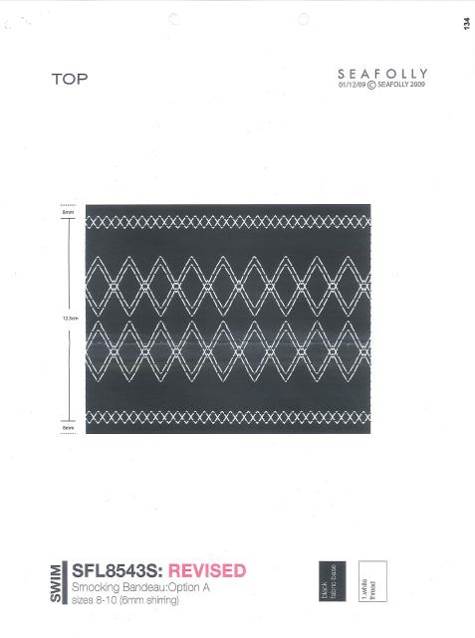

13 Seafolly’s final Senorita artwork is set out below, being the final drawings of the embroidery design:

City Beach’s Fiesta Richelle embroidery

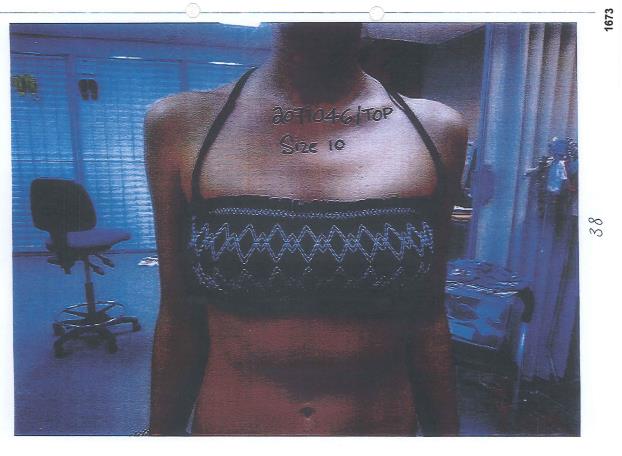

14 Winnie Bon, who was employed by City Beach and gave evidence on its behalf, deposed that the following picture showed the Richelle embroidery on a bandeau-shaped garment as approved by City Beach:

The parties’ principal submissions

15 Seafolly alleged that the substantial part of each of its artworks reproduced by City Beach were as follows:

32. The substantial part of the English Rose print that is reproduced in the Fiesta Rosette print comprises collectively the following:

(a) the use of impressionistic and non-pictorial roses;

(b) the use of leaves surrounding the roses and sprouting from the rose head;

(c) the majority of the leaves around the roses do not have stems;

(d) the use of a motif of clustered smaller roses and big roses being placed next to each other;

(e) the shading of the roses to create depth;

(f) the balancing of the background with the roses;

(g) the use of bigger roses and smaller roses;

(h) the colour palette being the use of pink roses with green leaves on a white or black background;

(i) the use of distinct edging on the highlights for the roses between the dark prink [sic] and the light pink;

(j) the roses do not overlap;

(k) the use of a similar number of leaves around the rose head; and

(l) the proportionality of leaves to flowers to background.

33. The substantial part of the Covent Garden print that is reproduced in the Fiesta Sienna print comprises collectively the following:

(a) the use of impressionistic and non-pictorial flowers;

(b) the use of the same types of flowers;

(c) the use of fronds;

(d) the use of fronds in blue;

(e) the pictorial line appearance of the flowers;

(f) the use of a different colour or shade of colour within each flower;

(g) the use of different sized flowers;

(h) the use of popping yellows;

(i) the use of different colours within the flowers to create depth;

(j) the visible background of the base colour through the flowers, leaves and fronds;

(k) the colour palette; and

(l) the colour palette on a white or black background.

34. The substantial part of the Senorita Artwork that is reproduced in the Fiesta Richelle garment comprises collectively the following:

(a) 4 discernible horizontal lines of diamond with the top and bottom being the same and the two middle lines being the same;

(b) the top and bottom lines of diamonds are smaller than the middle lines of diamonds;

(c) the second and third rows are adjacent diamond motifs made up of double stitching with a big diamond, little diamond sequence;

(d) the relative spacing between the two middle lines and the two border lines; and

(e) the degree of contrast between the stitching colour and fabric colour.

16 City Beach did not deny the subsistence, or Seafolly’s ownership of, copyright in the English Rose or Covent Garden artworks.

17 City Beach did not admit the subsistence of copyright in the Senorita artwork. It contended that the Senorita artwork was not original in the relevant sense of originating with Seafolly’s employees or designers, and was a commonplace design inevitably produced by the type of industrial sewing machine used to manufacture both the garments bearing the Senorita artwork and the garments bearing City Beach’s Richelle embroidery. If, contrary to that submission, copyright subsisted in the Senorita artwork, City Beach conceded that Seafolly owned it.

18 City Beach did not deny that its buyers and design subcontractor, 2Chillies Pty Ltd (“2Chillies”), had access to all three Seafolly artworks (which were imprinted on Seafolly garments purchased by City Beach and photographs of which were accessed by City Beach on the internet). City Beach conceded that it used the Seafolly garments bearing the relevant Seafolly artworks as “inspiration” to create the three corresponding City Beach prints.

19 City Beach admitted that it manufactured, imported for sale, sold or, by way of trade, offered for sale or exhibited, the garments bearing the allegedly infringing prints, and authorised that conduct.

20 City Beach nevertheless denied that it had infringed Seafolly’s copyright, contending that there was no sufficient objective similarity between the Seafolly artworks and the prints used in City Beach’s garments. Further, City Beach denied that any parts taken from the Seafolly artworks were substantial in the relevant sense.

21 City Beach submitted, in that context, that Seafolly’s artworks appeared from a crowded field of prior art, and hence, while there was (at least in the case of the English Rose and Covent Garden artworks) sufficient originality for the subsistence of copyright, that which was reproduced in the City Beach prints was not original and hence, not substantial. City Beach submitted that any originality of the Seafolly artistic works was limited to their collocation of features which were, in themselves, unoriginal, commonplace and derived from the “prior art” which Seafolly itself consulted and used for inspiration in accordance with the routine practice of the fashion industry. Accordingly, when abstracted from the collocation, any individual elements taken from the Seafolly works were unoriginal and hence unprotected.

22 Alternatively, City Beach submitted that it had, at most, taken the unprotectable idea or underlying concept of the Seafolly copyright works, rather than their form of expression. It also submitted that it had derived elements of the Rosette print and, in particular, the Sienna print from other sources.

23 City Beach further contended, in that context, that because the exclusive rights of the owner of the copyright in an artistic work do not (in contrast to copyright in literary, dramatic and musical works) include the right of adaptation, it followed that the adaptation of artistic works did not constitute an infringement. From that, in City Beach’s submission, it followed that infringement of an artistic work required an exact or faithful reproduction of a substantial part of the artistic work.

24 In relation to the Senorita artwork only, City Beach relied on the defence under s 77 of the Copyright Act, contending that the smocking embroidery used in Seafolly’s garment (bearing the Senorita artwork) was a corresponding design within the meaning of s 74 of the Copyright Act.

25 City Beach denied that it ought reasonably to have known that Seafolly was the owner of copyright in the Seafolly artworks or that its acts of commercial exploitation of its garments, if done in Australia, would have been an infringement of Seafolly’s copyright in the Seafolly artworks.

26 City Beach also submitted that the works in suit were not sufficiently identified. While some witnesses expressed uncertainty as to which of several versions of particular prints was the final version, I was satisfied that the works in suit were sufficiently identified above at paragraphs 8, 11 and 13.

witnesses

Seafolly’s witnesses

27 Seafolly relied on the following affidavits from lay witnesses, who were cross-examined by City Beach:

(a) the first affidavit of Anthony Frank Halas affirmed on 21 February 2013, as amended on 12 June 2013, and Mr Halas’s second affidavit affirmed on 17 May 2013;

(b) the affidavit of Genelle Walkom affirmed on 30 October 2012, as amended on 11 June 2013;

(c) the affidavit of Madelena Antao affirmed on 30 October 2012;

(d) the affidavit of Alyssa Coundouris affirmed on 30 October 2012, as amended on 12 June 2013;

(e) the affidavit of Malis So affirmed on 30 October 2012;

(f) the affidavit of Shannon Cheung affirmed on the 22 November 2012;

(g) the affidavit of Katrina Dean affirmed on the 30 October 2012; and

(h) the affidavit of Zhang Jun affirmed on 30 October 2012.

28 Seafolly tendered and relied on the following affidavits of lay witnesses who were not cross-examined:

(a) the affidavit of Lynn Tramonte, a product development manager employed by the applicant, affirmed 14 February 2013;

(b) the affidavit of Rebecca Kerr, the creative director of Longina for over 14 years, affirmed on 30 October 2012;

(c) the first affidavit of Jonathan Ariel Feder, lawyer for the applicant, affirmed on 7 February 2013, as amended on 12 June 2013 and Mr Feder’s second affidavit affirmed on 17 May 2013; and

(d) the affidavit of Savannah Hardingham, lawyer for the applicant, affirmed on 7 February 2013; and

29 Mr Halas is Seafolly’s chief executive officer. Mr Halas was a careful and direct witness, who made sensible and appropriate concessions.

30 Ms Walkom is and was employed by Seafolly as, since 1983, its head fashion designer and creative director of design. Ms Walkom was a clear, sensible and firm witness. She was responsive and made concessions where appropriate.

31 Ms Antao was employed by the applicant since 2010, and at the time of the trial was its creative director of graphic design manager. She was previously, and at the time that the relevant garments were created, the applicant’s graphic design manager and reported to Ms Walkom. Ms Antao was a straightforward and credible witness.

32 Ms Coundouris was employed by Seafolly from June 2009 to 2011 as a junior graphic designer and reported to Ms Antao. Ms Coundouris was a responsive and credible witness.

33 Ms So was employed by Seafolly since 2006 as a graphic designer and reported to Ms Antao and Ms Walkom. Ms So was a credible witness, although her responses were not particularly confident.

34 Ms Cheung was employed by Longina from 2007 or 2008 as a designer. Ms Cheung was an honest and responsive witness with firm views of her own.

35 Ms Dean was employed by Longina since 2008 as a designer. Ms Dean was a straightforward and sensible witness.

36 Mr Zhang has been employed by Longina as a textile designer for about 19 years. Mr Zhang spoke very limited English and gave evidence by video link from Hong Kong with the assistance of an interpreter. Mr Zhang was a responsive and credible witness.

37 Seafolly relied on the expert evidence of Patrick William Snelling, the Program Director of Textile Design in the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT University. Mr Snelling affirmed two affidavits on 4 February 2013 and 28 May 2013 respectively, and was cross-examined by the respondent.

38 Mr Snelling was a firm, sensible and conscientious expert witness who provided assistance to the Court. While the respondent contended, based, inter alia, on Mr Snelling’s correction of errors in his first affidavit, that his views were not his own, I was satisfied that Mr Snelling satisfactorily explained his corrections and was an honest witness who presented his own opinions.

39 Seafolly also subpoenaed the following officers or design employees of 2Chillies, who gave evidence viva voce and were cross-examined by City Beach:

(a) Matthew Nielsen. Mr Nielsen was the director of 2Chillies until about March 2013 after which he did some work as part of the exit process. He was a credible and responsive witness.

(b) Suzanne Bobsien-Christie, who was employed by 2Chillies as its head of design. Ms Bobsien-Christie was a reserved witness whose recollection was limited.

(c) Rachel Love, a freelance graphic artist working for 2Chillies under a contract. Ms Love presented as a credible witness.

(d) Susie Musso-Smith who was employed by 2Chillies as a designer and production coordinator. Ms Musso-Smith was generally a credible and responsive witness although somewhat unclear or evasive at points.

(e) Briana Thompson (formerly Croughan), who was employed by 2Chillies as a graphics designer. Ms Thompson was a credible and responsive witness.

City Beach’s witnesses

40 City Beach relied on affidavits from the following lay witnesses, who were cross-examined by the applicant:

(a) the first affidavit of Karyn Michelle Knobel sworn on 8 November 2012, as amended on 14 June 2013 and Ms Knobel’s second affidavit of Ms Knobel sworn on 12 April 2013;

(b) the affidavit of Paige Michelle Hanger sworn on 29 October 2012;

(c) the first affidavit of Chloe Leigh Dunlop sworn on 19 October 2012, as amended on 17 June 2013 and Ms Dunlop’s second affidavit affirmed on 24 April 2013; and

(d) the affidavit of Winnie Vei Ling Bon sworn on 8 November 2012.

41 The respondent tendered and relied on the following affidavits of lay witnesses who were not cross-examined:

(a) the affidavit of Michael Wilson, the respondent’s chief financial officer and a qualified accountant, sworn 1 May 2013 and Mr Wilson’ second affidavit sworn 17 June 2013; and

(b) the affidavit of Krista Jean Mahoney, lawyer for the respondent, sworn 12 April 2013.

42 Ms Knobel was a senior buyer who has been employed by City Beach in that position since early 2004 (and was employed by City Beach in more junior buyer roles from July 2000). Ms Knobel was not an impressive or reliable witness. She was frequently defensive, obstructive and non-responsive. She was not forthcoming or frank and was slow to make appropriate concessions. She frequently avoided answering the questions put to her. At times, her evidence was implausible and her recall of events was selective.

43 Ms Hanger was, at the time of the trial, employed by City Beach as a buyer (and had held that position since August 2011). Between March 2010 and August 2011 Ms Hanger reported to Ms Knobel. Ms Hanger was a reasonably direct witness.

44 Ms Dunlop was employed by City Beach as a trainee buyer and had held that position since September 2010. As at the date of the trial Ms Dunlop was no longer employed by City Beach. Ms Dunlop was not an impressive or reliable witness. Her evidence was unconvincing. She was reluctant to made appropriate concessions and was, at times, evasive.

45 Ms Bon was employed by City Beach at various periods and in various positions. From 2008 to 2012, she was employed as a production coordinator for ladies’ garments in Malaysia. In that position, she coordinated denim garments and swimwear production by receiving instructions from the City Beach buyers and liaising with manufacturers and their agents in China. She presented as a credible, albeit reserved, witness, who was prepared to make appropriate concessions.

46 The respondent relied on the following affidavits from expert witnesses, who were cross-examined by the applicant:

(a) The affidavit of Dean McGregor Brough, the Bachelor of Creative Industries course coordinator and lecturer (fashion) at Queensland University of Technology, sworn 23 April 2013. Mr Brough was, although unable to respond directly to some questions, a credible and knowledgeable expert witness.

(b) The affidavit of Robert Lewis McLaurin, the NSW sales manager for Capron Carter Australia Pty Ltd, sworn 16 April 2013. Mr McLaurin was a credible and knowledgeable expert witness.

(c) The affidavit of Jessica Thurecht, a swimwear and textiles designer, affirmed on 24 April 2013. Ms Thurecht was called by the respondent as an expert witness. She acknowledged that she had previously worked for 2Chillies as an employee and, after her employment ceased, as a contractor, who had peripheral involvement in the development of the Rosette print. She was a credible witness who appeared disinterested despite her prior connection with 2Chillies.

Background facts and evidence

Seafolly

47 Seafolly is an Australian company which, since 1975, has conducted business as a designer, manufacturer, wholesaler and retailer of fashion swimwear and swimwear accessories for women, girls and boys.

48 Seafolly sells its garments through various retailers in Australia in over 500 multi-brand stores (including major department stores), in Seafolly concept boutiques, factory outlets and through a website located at www.seafolly.com.au.

49 Seafolly also sells products in 1755 retail outlets overseas, where it also maintains offices.

50 Seafolly’s chief executive officer is Anthony Halas, who has held that position since 1998. Seafolly employs over 350 people and maintains a design team of 33 people, including both graphic and garment designers, at its Sydney head office.

51 The following members of the Seafolly design team were involved in work and exchanges relevant to this case:

(a) Ms Walkom;

(b) Ms Antao;

(c) Ms Coundouris; and

(d) Ms So.

52 Although it has an “in house” design team, Seafolly also engages an external design company, Longina, to design fabrics for Seafolly according to its instructions.

53 The following designers employed by Longina were involved in work and exchanges relevant to this case:

(a) Ms Kerr;

(b) Ms Cheung;

(c) Ms Dean; and

(d) Mr Zhang.

City Beach

54 The respondent, City Beach, was established in 1985 and maintains its head office in Brisbane. It conducts business as a designer, manufacturer and retailer of clothing including beachwear, surfwear, shoes, sports equipment and accessories for men, women and children.

55 City Beach sells its goods, including clothing, through a chain of City Beach retail stores in Australia. It has 60 City Beach stores spread throughout Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It also sells its goods, including clothing, through its website http://www.citybeach.com.au.

56 City Beach retains a number of personnel as buyers. The City Beach buyers and production personnel involved in work and exchange relevant to this case were:

(a) Ms Knobel;

(b) Ms Hanger;

(c) Ms Dunlop; and

(d) Ms Bon.

57 City Beach had from time to time engaged a design company, 2Chillies, to assist in designing prints and shapes for garments to be sold by City Beach. Matt Neilson was an owner and director of 2Chillies until March 2011. The following 2Chillies designers were involved in work and exchanges relevant to this case:

(a) Ms Bobsien-Christie;

(b) Ms Musso-Smith;

(c) Ms Thompson; and

(d) Ms Love.

The creation of Seafolly’s 2010 range

Seafolly’s English Rose artwork

58 In or about June or July 2009, Seafolly’s design employees began preparations to design its summer 2010 range of garments.

59 In July 2009, Ms Walkom and Ms Antao briefed Longina to create various fabric print designs including a fifties look vintage style rose print which became known as the English Rose print.

60 Ms Walkom and Ms Antao provided Longina with the following two photographs of bathing suits printed with rose designs as part of the brief to indicate what Ms Walkom wished to achieve:

61 During the course of July 2009, a large number of email exchanges occurred between the Seafolly design staff (principally Ms Walkom and Ms Antao) and staff at Longina (principally Ms Cheung and Ms Kerr), in which Longina staff sent draft rose designs they had prepared requesting feedback and Seafolly design staff responded with comments and instructions on how to revise, modify and change the draft designs.

62 Ms Dean, a designer at Longina, was provided with the two photographs set out above at paragraph 60 and created pencil sketches (which were not retained) for original rose designs on 7 July 2009. She forwarded her sketches and the two photographs to another Longina employee, a textile designer Zhang Jun. Ms Dean stated that she also provided the two photographs to indicate style and technique for the roses’ leaves and stems and to provide Mr Zhang with “inspiration and direction”.

63 Ms Cheung of Longina also provided Ms Dean’s pencil sketches to Mr Zhang, together with the examples of rose designs forwarded by Ms Walkom (set out at paragraph 60 above), and requested him to hand paint some rose elements for use in the design.

64 Mr Zhang recalled receiving the photographs but not the sketches. He spent three hours creating a hand painted work depicting roses. Mr Zhang’s work showed clusters of roses arranged on a white background, including groups of large full blown roses of similar size, some of which had long stems and leaves, while others were open roses viewed from overhead with sketchy leaves, together with clusters of smaller roses of varied sizes grouped together, with leaves at the base and few stems.

65 In cross-examination, Mr Zhang stated that he knew that he was not expected to copy the photographs but to use his creative skills to paint roses inspired by the photographs.

66 Mr Zhang explained that while he adopted the same style as the photograph showing dark pink roses, he created a painting with different layers and more varieties and layers of colours. While the leaves were similar, in that they were a loose painterly style, on the photographs the leaves were mainly single and separated, whereas in his painting the leaves were connected to the flowers. The photograph also included some flower buds.

67 On about 14 July 2009, Mr Zhang provided his painting to Ms Cheung, who scanned it and created the initial layout of the design using the rose motifs in the painting, to make them suitable for fabric. She sent a copy of the file to Ms Walkom. Ms Cheung testified that she moved some of the roses around and added some more closed, rather than open, roses, after receiving instructions from Ms Walkom. She also reduced some stems and added some more roses, after receiving instructions from Malis So (on behalf of Ms Walkom), who, on 15 July 2009 emailed her with a printout indicating where changes should be made. When all the changes had been made, Ms Cheung forwarded the completed design to Ms Walkom.

68 On 20 July 2009, Ms Walkom received and approved the final version of the English Rose artwork in both “pink on white” and “blue on white” colours (the latter was never used). On 31 July 2009, Ms Walkom also received and approved the final English Rose artwork in a “pink on black” colour concept.

69 By a deed made on 23 July 2009, Seafolly purchased the English Rose artwork from Longina and took an assignment of the copyright in the artwork (as shown in two drawings attached to the deed depicting the English Rose artwork in a “pink on white” colour concept, a “pink on black” colour concept and the hand painted rose motifs).

70 Fabrics printed with the English Rose artwork were subsequently used to manufacture a number of different swimwear garments for Seafolly’s 2010 summer range.

Seafolly’s Covent Garden artwork

71 On 25 August 2009, Seafolly purchased from Longina an original artwork for a fabric design known as the Covent Garden artwork in two colour concepts and took an assignment of the copyright in the Covent Garden artwork from Longina.

72 On or about 25 August 2009, Ms Walkom requested Ms So to put the Covent Garden artwork into a “repeat” and to alter the colours to match Seafolly’s planned colour palette for the new season.

73 On or about 26 August 2009, Ms So showed Ms Walkom a version of the Covent Garden artwork in a black colour concept (which incorporated the changes Ms Walkom had requested) together with a modified white colour concept version.

74 Ms Walkom approved both versions of the Covent Garden artwork. Subsequently, she received “strike offs” of fabric from the printer featuring the Covent Garden artwork, from which sample garments were made and approved by Ms Walkom. Fabric printed with the Covent Garden artwork was produced.

75 Seafolly then used fabric bearing the Covent Garden artwork to manufacture various styles of swimwear for its 2010 summer range.

Seafolly’s Senorita artwork

76 At some time prior to September 2009, Ms Walkom decided that she wanted to “manufacture garments from a fabric with smocking and featuring an embroidery design”.

77 In about September 2009, Ms Walkom and Ms Antao sourced examples of smocking from a fabric manufacturer in China to provide an indication of the type of smocking that the fabric manufacturer could achieve. The samples were not manufactured on lycra, the fabric used to create Seafolly’s swimwear. Ms Walkom stated that the samples included some small and large diamond patterns. She did not agree, however, that smocking was regularly, or even commonly, of a diagonal zigzag or diamond pattern.

78 Ms Walkom told Ms Antao that she wanted “an embroidery design created which could be printed on fabric with smocking that could then be used to manufacture swimwear bras and pants”. She wished to find out what the manufacturer could do, and to work around the constraints.

79 In September or early October 2009, Ms Antao briefed Ms Coundouris to develop an embroidery design to be used on fabric with smocking. Ms Antao provided Ms Coundouris with samples of smocking on fabric that she had received from the manufacturer in China.

80 In cross-examination, Ms Antao stated:

Ms Coundouris’ task was to actually design a brand new design. We had no starting point for the design … Other than the concept of – that you could embroider onto shirring so that was an initial new concept, something that the factories had developed, and then Ms Coundouris’ job was to create our own design of the embroidered aspect of this. So the shirring aspect is one part of it but the embroider [sic] is the part that we developed. We didn’t develop the shirring.

81 Ms Coundouris, who had no previous experience in creating embroidery designs for use on fabric with smocking, liaised with Seafolly’s pattern maker, Michelle Bremer, to work out how many lines of shirring would be included in each garment style. Ms Coundouris regarded shirring as the elasticised threading stitched in horizontal lines across, and thus gathering, the fabric, onto which the embroidery stitching must catch. In designing the embroidery, it was therefore necessary to know how many shirred lines the fabric would contain. Ms Coundouris stated that smocking was completely new to her and that she did not know how the smocking samples were produced. Nevertheless, she understood that her design would be attached to the shirred line or folded fabric.

82 Between about 8 September and 1 December 2009, Ms Coundouris created various embroidery designs for use on fabric with smocking, which she showed to Ms Antao and Ms Walkom for approval.

83 Ms Walkom and Ms Antao each deposed to the “significant trial and error in the process as the smocking fabric was difficult to work with”.

84 On or about 9 October 2009, Ms Coundouris created diamond embroidery designs for use on fabric with smocking, which Ms Walkom approved.

85 Ms Coundouris’ designs were sent to Seafolly’s garment manufacturer in China, which subsequently supplied samples of the designs applied to fabric with shirring for approval.

86 After receiving the samples, Ms Antao asked Ms Coundouris to make changes in order to simplify the design.

87 Ms Coundouris incorporated the requested changes into a new version of the artwork, which Ms Walkom approved. The designs as altered were sent to Seafolly’s garment manufacturer in China, which subsequently provided further samples.

88 Ms Coundouris could not recall how many times different versions of the designs were sent to the manufacturer or how many times Ms Antao asked her to make changes. Ms Antao deposed that she and Ms Walkom instructed Ms Coundouris to “keep simplifying the embroidery designs”.

89 On or about 1 December 2009, Ms Coundouris completed her final embroidery design (the Senorita artwork).

90 On or about 1 December 2009, Ms Walkom approved the final embroidery artwork and the final “colourways”. The artwork then was sent to Seafolly’s manufacturer.

91 On or about 18 December 2009, Ms Walkom and Ms Antao received samples of swimwear containing the embroidery artwork. As the double rows of stitching on the swimwear bra looked “too busy”, Ms Walkom and Ms Antao decided to reduce them to a single line.

92 Accordingly, Ms Walkom asked Ms Antao to arrange for further bra samples in which the embroidery was reduced to a single row. Ms Antao marked up photographs of the bra sample with that instruction.

93 Ms Walkom subsequently received the bra samples incorporating the requested change and approved the garments for production.

94 The final design was named “Senorita” and Seafolly swimwear styles featuring the Senorita artwork were released in Seafolly’s summer 2010 range.

The creation of City Beach’s 2011 range

95 Ms Knobel, a senior buyer with City Beach, was chiefly responsible on a day-to-day basis for selecting the styles and “stories” or prints for City Beach’s 2011 range. While the ultimate authority lay with City Beach’s director, Mel Hicks, Ms Knobel was the effective decision-maker.

96 Ms Knobel, in cross-examination, acknowledged that City Beach had purchased a Covent Garden garment, an English Rose garment and a Senorita garment. Ms Knobel either made the purchases herself or instructed someone to do so in the course of her research. Ms Knobel’s affidavits nevertheless made no reference to the purchase of Seafolly garments.

97 City Beach had from time to time engaged 2Chillies, a design company, to prepare designs. On 13 January 2011, Ms Knobel met Mr Nielsen, a director of 2Chillies, at City Beach’s head office to discuss ideas for City Beach’s ladies’ swimwear range for the 2011/2012 summer season, including “water colour floral prints”, “white based floral prints” and “rose floral prints”. At the end of the meeting, Ms Knobel gave Mr Nielsen photographs of different bikinis in the market for inspiration. One of the photographs showed a Seafolly Covent Garden garment.

98 On 17 January 2011, Ms Knobel followed up with an email to Mr Nielsen stating that she had attached “swim samples” and that the “prints can be another talking point when I see more of what you guys have come up with so far…”. The email attached three pictures of bikini garments, one of which was a photograph of a Seafolly English Rose garment (a bikini top). Ms Knobel deposed that this email was not a request for 2Chillies to design any specific print. She deposed that:

My intention, in sending the photographs, was to provide 2Chillies with a better idea of the look or style of the prints that City Beach wanted developed.

99 She identified the use of “floral prints” and “rose prints” as a “popular trend” at that time.

100 Later that day, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen asking him to “come up with a [b]ikini along the lines of the Sierra range that 2Chillies did”. The Sierra range was a line of swimwear successfully sold by City Beach in 2009-2010, bearing a print known as Sierra, which was purchased from its designer, 2Chillies. Ms Knobel attached pictures of a dress (the City Beach border print dress), which City Beach had purchased from a Sydney supplier and sold in multiples during 2010-2011. She considered that the border print dress resembled the Sierra print, particularly in that they were both border (or placement) prints in which the print does not cover the entire garment.

101 On or about 18 January 2011, Ms Knobel telephoned Mr Nielsen. She deposed that she told him that City Beach wanted 2Chillies to develop various prints for a “swimmer”, including a “rose floral print”. She advised him that the attachments to her email dated 17 January 2011, which included a photograph of Seafolly’s English Rose garment (bikini top), were part of City Beach’s “inspiration for developing a rose floral print”.

102 On 19 January 2011, Ms Dunlop emailed Mr Nielsen and stated “please find attached more print direction. ROSE PRINT – Versions of this print with white base”. Ms Dunlop attached a scanned copy of a swatch from dress, which had a black background filled with tightly packed multi-coloured roses (the City Beach rose print dress).

103 On 20 January 2011, Ms Dunlop emailed Mr Nielsen. She asked 2Chillies to draw up designs for a number of prints, including:

SIERRA UPDATE

Please update this print and draw up in 2 colourways

Black base – Frill front bandeau and frill pant

White base – Frill front bandeau and frill pant

…

ROSE PRINT

Please draw up versions of this print with white base.

Styling to be bandeau shape with contrast bagged out tie at CF and tie side pant with contrast bagged out ties at each side.

104 Ms Dunlop attached a number of pictures, including a photograph of a swatch from the City Beach rose print dress and two photographs of the City Beach border print dress. Ms Dunlop deposed that City Beach wanted 2Chillies to create “the rose print based on the swatch but with a white background”. Ms Dunlop deposed that the colours in the City Beach border print dress were to be used in updating the Sierra print.

105 Mr Nielsen responded to Ms Dunlop’s email confirming that 2Chillies would draw up the requested designs.

106 On 24 January 2011 at 10.55 am, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen (copying in Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger) stating that City Beach proposed to order a number of swimwear separates, including:

7. Rose Print – Bandeau – (New print based off [the] City Beach [rose print] dress)

…

11. Sierra Update – (New Print refer to [the City Beach border print] dress) White Base with multi colours -

12. Sierra update – (New print refer to [the City Beach border print] dress) Black Base with multi colours – White frill

107 Ms Knobel attached to her email a number of photographs, including a photograph of a swatch from the City Beach rose print dress and a photograph of the City Beach border print dress.

108 At 11.29 am, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen with the subject line “attached is just another print reference for a sierra update – similar to [the City Beach border print] dress”. The email attached a photograph of the Seafolly Covent Garden bikini top.

109 At 11.34 am, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen instructions about the shapes of the bikini sets. She attached a number of photographs of bikinis and dresses, including two pictures of Seafolly English Rose bikini tops.

110 At 11.45 am, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen with the subject line “SHAPE REFERENCES – FOR NEW PRINTS”. She stated “[p]lease see attached NEW SHAPE options … these are for Fiesta prints only”. She attached photographs of various garments, including photographs of a Seafolly Covent Garden bikini top and a Seafolly English Rose bikini top.

111 At 2.05 pm, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen and stated:

In reference to the white base multi floral Set we are doing... please see the attached City beach dress.

This has been one of our best sellers so we would like to translate this print into a set.

This dress is direct out of China, so we have no problems copying this print.

…

Top shape is to be a bandeau.

112 Ms Knobel attached a picture of a dress she described as the “Soho Floral dress” and a photograph of a Seafolly English Rose bikini top. Ms Knobel deposed that she attached the photograph of the English Rose garment in order to reinforce to Mr Nielsen that she wanted the bikini to be a bandeau shape.

The Sienna print

113 On 31 January 2011, Ms Musso-Smith of 2Chillies emailed Ms Knobel, Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger, seeking clarification of Ms Knobel’s request that 2Chillies prepare an updated Sierra print. Ms Musso-Smith attached a photograph of a Seafolly Covent Garden garment and a photograph of the City Beach border print dress. Ms Musso-Smith stated:

In your pictures attached; the artwork on the bikini top is not a ‘border’ print like the previous season’s SIERRA print used to be.

Does this mean you DO NOT want a ‘border’ print?

OR are you just referring to these pictures as an indication of the type of flower and colours you want to use?

Could you please provide added information before we proceed with developing the artwork so we are sure we are doing the right thing for you?

114 Ms Hanger responded:

Karyn [Knobel] would still like a border print. The two pictures she provided were just for direction with flowers and colour.

115 In her affidavit Ms Hanger asserted that when she used the word “direction” she meant that 2Chillies should use the prints, including Seafolly’s Covent Garden print as inspiration. In cross-examination, however, she agreed that, at Ms Knobel’s direction, she provided the two pictures for “direction, flowers and colours”.

116 Ms Musso-Smith confirmed that City Beach would commence work on the artwork for the updated Sierra print. She understood that City Beach required “a border print” and that the pictures indicated the required “direction of the flowers and colours”.

117 Ms Knobel deposed that, on or about 31 January 2011, she advised Ms Musso-Smith by telephone that the Seafolly Covent Garden print “was only to be used as inspiration for the types of colours (being bright, vibrant colours)” to be used in the updated Sierra print.

118 Ms Knobel initially denied that she instructed Ms Musso-Smith to use the Seafolly Covent Garden garment as inspiration for the flowers and colours as well. She ultimately conceded, however, that the photographs of both the Seafolly Covent Garden garment and the City Beach border print dress were intended to provide inspiration for the “type of flowers and colours” and testified that by type she meant “different shapes of flowers”.

119 Ms Thompson, then a designer at 2Chillies, was asked to update the Sierra print and was given a photograph of the City Beach border print dress and a photograph of a Seafolly Covent Garden bikini top. She testified that her instructions were to produce a border print, like the Sierra print, and to use the two pictures “for the style of the actual shapes of the flowers, and the style of artwork” and colour.

120 Ms Thompson testified that she tried to use the City Beach dress for “inspiration in terms of the flower shapes” and “obviously trying to steer away from the Seafolly one … Because it’s Seafolly”. She painted the flowers using watercolours on paper and then altered the colours, making them more vibrant, on a computer in Photoshop, before turning the print into a border print. At trial, she acknowledged obvious similarities between her design and the Covent Garden garment although, at the time, she had not thought there was a problem.

121 On 1 February 2011, Ms Musso-Smith sent Ms Knobel, Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger an email with the subject line “updated version of the ‘SIERRA’ print”. She attached drawings featuring artwork for the print prepared by 2Chillies in white and black colour ways. Ms Musso-Smith stated:

In reply to your request for an updated version of ‘SIERRA’ Print ...

We have developed this print referring to the picture you sent us and using similar flowers and colours …

122 On 3 February 2011, Ms Knobel emailed Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger instructing them to “go ahead” with orders for the Sienna print in black and white colour ways.

123 On 10 February 2011, Ms Hanger emailed Ms Musso-Smith with the subject line “sierra update” and stated “[t]his colour way of the Sierra update is confirmed”. The print was subsequently referred to as the Sienna print. Ms Musso-Smith responded to Ms Hanger, confirming the style numbers for the Sienna print bandeau top and pant.

124 On 11 February 2011, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Knobel, Ms Hanger and Ms Dunlop and attached final drawings for approval for the Sienna print bandeau and pant in black and white colour ways.

125 On 10 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Knobel, Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger regarding the “Sienna white one-piece” stating that 2Chillies had drawn the design as an “all-over print” rather than a border print for the one-piece garment and attaching relevant artwork.

126 On 12 May 2011, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Knobel, Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger advising that 2Chillies had posted a number of strike-offs to City Beach, including garments bearing the Sienna print in black and in white and requesting feedback.

127 On 13 May 2011, Ms Dunlop emailed Ms Musso-Smith, Ms Knobel and Ms Hanger approving the Sienna print in black and white colour ways.

128 On 18 May 2011, Ms Dunlop emailed Ms Musso-Smith providing comments on the strike-off samples. Ms Dunlop advised that the bandeau in the Sienna print in the white colour way was approved. She asked 2Chillies re- position the Sienna print on the pant so that it featured more of the print.

The Rosette print

129 On 11 February 2011, Ms Musso-Smith also sent Ms Knobel, Ms Hanger and Ms Dunlop a summary of styles City Beach had ordered from 2Chillies thus far, and all pending styles. She also sought confirmation of the shape of the rose print bikinis.

130 Ms Thompson completed 2Chillies’ first attempt at the “rose print” City Beach had requested, inspired by the print used for the City Beach rose print dress.

131 Ms Knobel rejected Ms Thompson’s attempt at a rose print as “ugly”.

132 On 21 February 2011, on Ms Knobel’s direction, Ms Hanger emailed Ms Musso-Smith attaching, inter alia, photographs of a Seafolly English Rose bikini top and a black based multi-colour rose “Forever 21” bikini pant. Ms Hanger stated:

Can you please change the attached print to be as per attached pictures.

Please see the below comments.

• Please make the roses the same sizes as per the attached white base seafolly picture attached we want some bigger roses and some small roses.

• Please use the same colour tones of the attached bikini pant with the black base.

• We don’t not want the white/grey flower in this print please just choose another pink tone that would sit well in this print.

133 Ms Hanger deposed that Ms Knobel directed her to provide the photograph of the Seafolly English Rose garment to 2Chillies in order to indicate the “sort of roses” that City Beach wanted 2Chillies to design. In cross-examination, Ms Hanger agreed that by “design” she meant:

… the whole design of the print, the spacing between the flowers, the colours of the flowers, the shape of the flowers, the size of the flowers, the leaves … [a]nything to do with the design …

134 She testified that it was easiest and most effective to provide 2Chillies with visual, as opposed to verbal, direction and inspiration.

135 Ms Knobel conceded in cross-examination that, at this point in time, City Beach provided only two photographs to 2Chillies for “inspiration” in relation to the Rosette print, one of which was the photograph of the Seafolly English Rose bikini top.

136 On 22 February 2011, Ms Musso-Smith replied that City Beach’s instructions were “noted and clear”.

137 On 25 February 2011, Ms Musso-Smith sent Ms Dunlop, Ms Knobel, Ms Hanger and another an email containing the following “ROSE PRINT as requested” (the “first Rosette print”):

138 Ms Love, a freelance designer at 2Chillies, designed the first Rosette print. She was given a photograph of a Seafolly English Rose garment and photograph of a Forever 21 bikini pant. She was instructed “to create a print that had that feel” and she “probably” had regard more to the Seafolly English Rose garment. She stated that her instructions were “[t]o have a look and feel like the Seafolly one”. While she could not recall her further details of instructions, Ms Love stated “generally when we were given – like pictures for inspiration, that was usually what the client would want, that feeling – that feeling in the print, but I can’t recall if they were the exact words, but it definitely wasn’t ‘for inspiration’”.

139 Ms Love testified that while she designed the first Rosette print, Ms Thompson made the changes requested by City Beach and produced the subsequent versions of the print. Ms Love observed that there were “many changes” to the print and “we did try to make it more different, but it did keep getting changed close back to the Seafolly one … [we were trying to make it] more original”.

140 Ms Dunlop emailed Ms Musso-Smith instructing her to change the colours of the roses (shades of pink to replace the orange shades) and leaves (green rather than blue) in the print and to make the leaves 10% smaller.

141 Ms Musso-Smith subsequently sent Ms Dunlop the reworked print (the “second Rosette print”).

142 On 28 February 2011, Ms Knobel ordered swimwear garments bearing a print known as “Strawberries and Cream” from 2Chillies.

143 On 2 March 2011, a series of emails were exchanged between Ms Knobel and persons at 2Chillies.

144 At 11.58 am, Ms Knobel emailed Mr Nielsen (copying in Ms Musso-Smith and others) pictures from Seafolly’s website, including pictures of Seafolly’s English Rose and Covent Garden garments with the subject line “ROSE FLORAL IDEAS – calling you regarding this now …”. Ms Knobel deposed that her email concerned “a new rose floral print” rather than the Rosette print. The email attached eight photographs of women in bikinis, a number of which Ms Knobel knew to be Seafolly English Rose and Covent Garden garments. She testified that she had found the photographs on the internet, and possibly on Seafolly’s website.

145 At 2.02 pm, Ms Knobel sent Ms Musso-Smith an email with four photographs of bikini tops or pants, including a photograph of a Seafolly English Rose bikini top with the subject line “ROSE PRINT SEPS – please call me …”. Ms Knobel deposed that the email referred to the shape or three dimensional elements of the garments and not to the artwork.

146 Ms Knobel deposed that, later that same day, she instructed Ms Musso-Smith to change “the colours of the rose floral print … so that the roses contained within had more pink shades and the leaves green”.

147 On 3 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith advised Ms Knobel by email that if her requested changes were made, the new rose print 2Chillies was designing would so closely resemble 2Chillies existing “Strawberries and Cream” print that City Beach might simply prefer to purchase it from 2Chillies range, rather than proceeding with its new requests. The email asked if City Beach still wished to proceed with its requests in the white colour way. The email attached the following requests, two of which referred to a “rose print similar to Seafolly print (pictured below)” and displayed photographs of Seafolly English Rose bikini tops.

148 Ms Musso-Smith acknowledged that in describing the “first request” as the creation of a print “similar to” Seafolly’s English Rose garment, she understood that City Beach wanted “a rose print, something similar to Seafolly, or in other words, inspired by Seafolly”. She understood that City Beach’s “third request” was for “that same print again, the rose print, similar to the Seafolly print, … two colour ways, white and black, and then the shape is as the picture below, but adding piping to the seams”.

149 Ms Knobel asserted that she saw Ms Musso-Smith’s email as relating to the shape of the garment, not the print. If that were so, however, the reference to the Strawberries and Cream print is inexplicable.

150 Ms Knobel deposed that she spoke to Ms Musso-Smith later that day and confirmed that 2Chillies was to draw up the shapes, not the print, of the separate styles set out in Ms Musso-Smith’s email. Ms Musso-Smith then emailed Ms Knobel, referring to their conversation and confirmed that “we’re still going ahead with all of this (that is, the three requests), thanks for clarifying this”.

151 Ms Knobel advised Mr Nielsen that City Beach did not wish to use 2Chillies’ Strawberries and Cream print because it wanted to develop its own rose floral print.

152 On 4 March 2011, Ms Knobel received the five emails from Ms Musso-Smith sent Ms Knobel five emails attaching drawings of bikinis with rose prints prepared by Ms Thompson and seeking approvals.

153 Ms Knobel deposed that these emails all related to shape, not print, as City Beach was yet to approve the print.

154 Later that day, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Thompson and stated in relation to “2. CB TANKINI SET REQUEST” referring to a “Seafolly knock off – ROSE PRINT” as follows:

PRINT:

Seafolly knock off – ROSE PRINT

BLACK C/WAY ONLY (no white cway)

SHAPE:

155 In cross-examination, Ms Musso-Smith explained her reference to “a Seafolly knock off” as “loosely talking internally where instead of using the correct code number … I’m just giving it a description which is what that is, but that’s not to say that … is accurate”

156 On 7 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith forwarded an email chain, including the email extracted above between Ms Musso-Smith and Ms Thompson, to Ms Knobel, Ms Dunlop and Ms Hanger seeking confirmation for production. Ms Knobel deposed that she did not know why the print was described as the “Seafolly knock off”, as City Beach’s intention was to create an original print.

157 Within the 2Chillies design team, concern was building because the rose print they were designing at City Beach’s behest appeared to resemble the Seafolly English Rose print. On 7 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Mr Nielsen stating:

Here is the picture of the City Beach artwork and the 2nd picture is the Seafolly Print.

As I mentioned, the styles are not the same – it’s just the artwork.

158 Ms Musso-Smith raised her concern with Mr Nielsen on the instructions of Ms Bobsien-Christie, the head of the design team, who, as she confirmed at trial, “felt that [the Rosette print] looked like the Seafolly print … it looked close to the Seafolly print”.

159 Later that day, Mr Nielsen forwarded Ms Musso-Smith’s email to Ms Knobel and Ms Dunlop and asked City Beach to accept responsibility if the new rose print were too close to Seafolly’s print. Mr Nielsen’s email stated:

Given the print below is close to that of seafolly , I would like your confirmation that you accept the responsibility for the design should seafolly react to it.

160 Mr Nielsen testified:

My concerns were that … if any reference was to be made to a Seafolly garment or a [sic] …attempted variation or version of a Seafolly garment were to be made, that I wasn’t prepared to accept responsibility for or liability for that particular print that was being done. And therefore, I expressed my concerns to City Beach about that and requested that Karyn [Knobel] and/or the owner of City Beach accept and acknowledge responsibility should they wish to take that path.

…

[M]y concern arose from the beginning were a reference was made to a Seafolly garment and being asked to create something similar to a Seafolly garment to me just flagged an issue …

161 When Ms Dunlop raised the issue with Mel Hicks, one of City Beach’s directors, he refused to accept responsibility, stating that City Beach did not want a print resembling Seafolly’s print and that he wanted the print used by City Beach to be a different print.

162 Later again that same day, Ms Knobel emailed Ms Musso-Smith stating:

Mel will not be signing anything, we would like to amend the print. I would like to keep the courings [sic] the same but they [sic] shape of the flowers can change. Chloe [Dunlop] will call you regarding this now.

163 Ms Dunlop also told Ms Musso-Smith that City Beach would not take responsibility for the print and asked her to rework it to look “less like the Seafolly print”.

164 In March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith asked Ms Thurecht, who was employed by 2Chillies, whether the Rosette print should include other design elements. Ms Thurecht suggested the inclusion of tiny rose buds or “baby’s breath” flowers.

165 On 8 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith sent Ms Dunlop a third version of the Rosette print, stating that the print had been “re-worked so it looks ‘less’ like the Seafolly print but the concept and colours are still the same.” She included the following drawing of the reworked print (the “third Rosette print”):

166 According to Ms Musso-Smith, the third version was achieved by removing some roses and adding two obviously different types of flowers and some rosebuds.

167 Ms Thompson testified that the changes were made “[j]ust to try and differentiate [the print] from a white based rose print which could possibly be interpreted as looking like Seafolly[’s] [print]”.

168 Both Ms Knobel and Ms Dunlop initially deposed that City Beach had wanted to develop a rose floral print containing both roses and other types of flowers. In cross-examination, however, Ms Knobel conceded that it was 2Chillies’ idea, not City Beach’s, to insert a flower other than a rose into the Fiesta Rosette print. Later she testified that “I couldn’t tell you” whether or not the idea came from 2Chillies.

169 Ms Dunlop ultimately conceded that City Beach’s objective was to produce a rose print, not a floral print with roses, and that it was 2Chillies’ idea to include flowers other than roses.

170 On 11 March 2011, Ms Dunlop sent Ms Musso-Smith (copying in Ms Thompson and others) comments on the “re-worked rose print” (the third Rosette print extracted above at paragraph 165). She included a marked up a copy of the print indicating that 2Chillies should remove two of the three newly inserted flowers (included to differentiate the print from Seafolly’s print) and replace them with the “original roses”.

171 On receiving Ms Dunlop’s instructions, Ms Thompson “had to remove a lot of the different flowers that I just placed in and replaced them back with the roses, except for one of the flowers”. Ms Thompson found the design process “very frustrating … [b]ecause we were trying to make it different and not so similar, and I felt like we were reverting back to what we had started with”.

172 Ms Musso-Smith also thought that Ms Dunlop’s instructions would lead to the print “reverting back to the original design bar one small flower”.

173 On 14 March 2011, at 9.34 am, Ms Musso-Smith responded to Ms Dunlop, advising that her requested changes would mean “basically reverting back to the original artwork – other than the one small, new flower”. She requested City Beach to accept responsibility for the design.

174 Ms Dunlop responded at 9.51 am (copying in Ms Knobel and Mr Nielsen) stating that she would again discuss the matter with Mr Hicks.

175 At 9.53 am Mr Nielsen responded to Ms Dunlop’s email and stated: “We are happy with the print. It shouldn’t be an issue”. There was some uncertainty about which version of the print Mr Nielsen was “happy with”. He was not copied into Ms Dunlop’s email requesting changes to the third version of the Rosette print which had included the changes to distance it from Seafolly. Rather, he was copied into Ms Musso-Smith’s response, which although it included Ms Dunlop’s email in the chain, did not include her marked up attachment illustrating the changes she required (and did include a picture of the third Rosette print, which contained the new types of flowers inserted by 2Chillies).

176 Mr Nielsen could not specifically recall which version of the print he was referring to in his email, but testified that 2Chillies felt that the third version of the Rosette print was “very different” from the Seafolly print. I conclude that Mr Nielsen’s email was referring to the third version of the Rosette print. Mr Nielsen testified that he no longer made any demands for indemnities after that time because:

I was happy with what I had seen, that if that was what was in fact going to go through to production that I believed that it shouldn’t be an issue. And given the nature of City Beach, I assumed that they were not going to put anything in writing. However, I had voiced my concerns pretty strongly about where we were positioned.

177 Ms Dunlop deposed that, based on Mr Nielsen’s email, she was satisfied that the third Rosette print, but as reworked in accordance with her instructions, was “sufficiently different” from Seafolly’s English Rose print. In cross-examination, she first testified that she believed Mr Nielsen was referring to her request for amendments and the reworked print incorporating those amendments (which she had yet to receive). She conceded, however, that she may have been mistaken.

178 At 3.14 pm on 14 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Dunlop and others a fourth version of the Rosette print which included small rose buds and more white space to differentiate it from the Seafolly print. Ms Musso-Smith stated:

Please see the ROSE PRINT artwork re-worked again.. we have added little rose buds to this to make it different but its [sic] still in the pretty rose theme. We have also added some more white space to the background. We think this is different enough now from the Seafolly, what do you think? Do you like it?

179 The email attached the following print:

180 Ms Musso-Smith also forwarded the following chain of emails between 2Chillies employees, which demonstrated that 2Chillies staff remained concerned about the similarity of their design to Seafolly’s English Rose print.

(1) At 10.36 am, Ms Thompson emailed Ms Musso-Smith a further attempt at the Rosette print, which was not in evidence.

(2) At 11.17 am, Ms Musso-Smith forwarded Ms Thompson’s email internally (to unknown recipients) and stated:

Before I send this new artwork to [City Beach], do you both agree this is different enough from the Seafolly print?

Can you have another look because I would hate to offer it to them and then we decide it is still too close… .

To me it still looks quite similar but I could be wrong?

(3) At 12.09 pm, Ms Thompson emailed Mr Nielsen, Ms Musso-Smith and copied Ms Bobsien-Christie, in response to Ms Musso-Smith’s email at 11.17 am, with another version of the Rosette print (not in evidence) and stated:

I have removed the flowers they asked to be removed and have spaced it out to be different from Seafolly and more like one of Jo’s new samples. I have asked Suz [Bobsien-Christie] to have a look and she and I both are still concerned in the similarity to Seafolly’s original rose print.

(4) At 12.16 pm, Ms Musso-Smith responded and stated:

I like the added space in the background however I think it still looks like Seafolly…… unfortunately. Maybe we should add the little, tiny, tiny rose buds/baby’s breath in a bunch into the print like Jess suggested. I think that would change it enough and it is still keeping it in the ‘rose’ theme. Other than that I am out if [sic] ideas of what to do with this.

(5) At 3.01 pm, Ms Thompson emailed Ms Musso-Smith, copying to Ms Bobsien-Christie, a fourth version of the Rosette print and stated “Ok what do you think of this one……..I’m all out of ideas….”.

181 In cross-examination Ms Dunlop conceded that she no longer believed that 2Chillies was happy with the print.

182 Ms Thompson testified that when concerns were raised about City Beach’s requested amendments to the third Rosette print, she reworked the print to create a fourth version. She testified that in the fourth version, “we’ve taken out some of the roses from the print and added in a different shaped flower to make it less of a rose print and more of a floral”. She testified that she “tried to … space it out a little bit more so there’s a lot more white space showing, not so many flowers everywhere [and] then add in some little tiny rosebuds so it’s cute”.

183 At 4.28 pm on 14 March 2011, Ms Dunlop emailed Ms Musso-Smith (and others) requiring that the distinguishing small roses be removed and the spacing change be reversed. The email stated:

The little rose buds are cute but now it is too spacey.

Can they please make it closer together or add one more flower to the repeat?

184 Ms Thompson recalled being told “to change [the print] back”.

185 Ms Musso-Smith found it “frustrating” as the change suggested by Ms Dunlop would cause the design to revert to its original form which was concerningly similar to the Seafolly English Rose print. She testified that 2Chillies had added more space into the print in order to “make it different from Seafolly” but City Beach rejected the change.

186 At 10.38 am on 15 March 2011, Ms Musso-Smith forwarded Ms Dunlop the “NEW ROSE PRINT – re worked” and a chain of emails between herself and Ms Thompson.

187 At 10.43 am, Ms Dunlop asked Ms Musso-Smith for “the new rose-ish prints”.

188 At 10.48 am, Ms Musso-Smith emailed Ms Dunlop warning her that if she made the changes Ms Dunlop required, the design would revert to its original state which had caused concern. Ms Musso-Smith enclosed a picture of an Abercrombie & Fitch print, explaining that it had given 2Chillies the idea of adding “more white space” in the background and stated “[l]et me know how you would like to proceed – its fine to make your changes but again as I mentioned, design are convinced by doing that it [sic] we’ll end up back at square one”.

189 At 4.30 pm, Ms Dunlop sent Ms Knobel a drawing of the fourth version of the Rosette print and a photograph of the Abercrombie & Fitch bikini. Contrary to her initial denials at trial, in the email she made clear that she was aware of 2Chillies’ unease about the Rosette print’s resemblance to Seafolly’s English Rose print.

2chillies is still wigging out about this rose print being too close to seafollys.

The attached is a revised draw up. They have got the ‘inspiration’ from an Abercrombie Bikini that was bought in LA last week.

(emphasis in original)

190 At 5.20 pm, Ms Dunlop again emailed Ms Knobel some images informing her that 2Chillies’ concern that the resemblance to Seafolly was not addressed. She explained that the images included:

The original, the reworked with the crazy flowers and the latest draw up with the white background. In the folder there is also the Abercrombie sample and a photo of the original Folly sample. (I don’t even want to mention the brand name anymore) I feel like I am going to get shot.

191 At 11.54 am on 16 March 2011, Ms Dunlop instructed Ms Musso-Smith by email to include one of the larger non-rose flowers from the third version of the Rosette print in the fourth version.

192 Ms Musso-Smith reworked the fourth version of the Rosette print in accordance with Ms Dunlop’s instructions and emailed it to her. This was the final version of the Rosette print.

193 At 3.00 pm, Ms Dunlop emailed Ms Knobel the final version of the Rosette print with the subject line “NEWEST ROSE PRINT! – THINK THIS COULD BE IT!”. At 3.01 pm, she responded to Ms Musso-Smith with a “smiling face” device.

194 In further exchanges that afternoon, Ms Knobel asked Ms Dunlop whether she liked the added non-rose flower, which Ms Dunlop stated “makes it very different from Seafolly”.

195 On 17 March 2011, Ms Knobel asked Ms Dunlop whether she would like anything else, as otherwise “we’ll just approve this”.

196 On 24 March 2011, Ms Dunlop informed Ms Musso-Smith that final version of the Rosette print (shown below) was confirmed.

197 In late June 2011, 2Chillies sent City Beach strikes off bearing the final version of the Rosette print with black and white backgrounds.

198 In early July 2011, Ms Musso-Smith and Ms Dunlop exchanged comments about the shapes of the garments and the colours. Ms Dunlop was concerned about the “maroon” colours in the roses but Ms Musso-Smith advised that:

The girls in design … LOVED it … When asking them finally about the ‘purply’ colour in the print, they all said NO they like it and wouldn’t change anything.

199 On 4 July 2011, Ms Thurecht, in response to a query from Ms Dunlop, stated:

You can’t see the purple when it’s made up at all and the purple does suit the cooler greens in the print … If it was me I would probably change the purple.

200 On 5 July 2011, Ms Dunlop asked Ms Musso-Smith “to change the colours of the roses which were more maroon and purple so that the shades used were more pink and red”. Ms Musso-Smith did so and sent Ms Dunlop an updated final version of the Rosette print with the requested colour changes.

201 On 7 July 2011, Ms Dunlop confirmed to Ms Musso-Smith that City Beach would proceed with “the Rose print as per the original strike-off and samples that [City Beach had] received”. Ms Dunlop deposed that she was referring to the strike-offs set out at paragraph 197. She could not recall why she changed her instructions.

202 In July 2011, City Beach commenced buying and selling garments bearing the final version of the Rosette print.

203 In or about November 2011, City Beach ordered new styles of bikini separates and sets bearing the Rosette print. 2Chillies prepared further strike-offs with a print that had “more purple colours” than the earlier production. Ms Dunlop and Mr Nielsen exchanged emails regarding the colour differences. City Beach then produced garments using a new printer with a better quality fabric print. As there were no garments bearing the Rosette print in store at that time, Ms Dunlop thought that the slight difference in colouring arising from the new printer would not be noticeable.

The Richelle embroidery

204 In late January, Ms Knobel instructed Ms Bon to “coordinate the production of samples of a bandeau and a pant which were to feature a shirred pattern”.

205 Accordingly, on 28 January 2011, Ms Bon emailed Welon (China) Ltd (“Welon”), a Chinese company that, amongst other things, develops clothing, photographs of a Seafolly Senorita one-piece swimsuit accompanied by a handwritten instruction to use the top row of the embroidery for a pant. Ms Bon requested a sample of a bandeau and pant featuring a shirred pattern and smocking.

206 Ms Bon instructed Welon to develop a “bandeau with shirred pattern” and a “tie sides pants with shirred pattern”. The bandeau shape was to be “as per the” original sent and the pant was to have “a line of the shirred detail as per the Top above, on the top of the pant”. For both the bandeau and the pant, she instructed “[a]ll pattern details to stay the same as original and also the colour of the surface thread – off white”.

207 Ms Bon arranged for a one-piece Seafolly Senorita swimsuit to be delivered to Welon.

208 Ms Knobel acknowledged that she “probably” herself purchased at least one of Seafolly’s Senorita garments or arranged for someone else at City Beach to purchase it. Ms Knobel then gave the Senorita garment to Ms Bon. Ms Knobel denied, however, that she provided Ms Bon with the Senorita garment so that Ms Bon could instruct Welon to copy the embroidery.

209 In cross-examination, Ms Bon stated that she asked Welon to make the sample “as close as possible to what the original looks like with the shirring idea” and agreed that her original instructions were “to copy the shirring in the [Seafolly] garment”. Ms Bon agreed that the only reference she gave to Welon (China) Ltd for the stitching was the Seafolly Senorita garment itself.

210 On 18 March 2011, after receiving from Welon samples of a bandeau and pant featuring the Richelle embroidery, Ms Bon sent Welon comments. She attached photographs of the samples and a photograph of a Seafolly Senorita garment with handwritten instructions, including to use the top row of the embroidery on the Senorita garment for the pant.

211 In cross-examination Ms Bon agreed that the only instruction she gave Welon in relation to the pattern was to reduce the size of the pattern, which should otherwise remain the same. She conceded that her intention at this stage was to copy the Seafolly Senorita garment’s stitching.

212 Sometime around May 2011, Welon provided Ms Bon with new and amended samples of a bandeau and pant featuring the Richelle embroidery. Ms Bon conceded Welon copied the Seafolly stitching. The size of the pattern was reduced by squeezing the zigzagging so that it crossed over a little more on the shirt pattern. Ms Bon stated that it was Welon’s idea to use small and large diamonds.

213 After some further amendments to the bandeau and pant which were unrelated to the stitching, Ms Bon consulted with Ms Knobel and approved the Richelle embroidery samples for manufacture.

City Beach’s sale of garments with the relevant prints

214 Mr Wilson deposed that by 29 April 2013, City Beach had sold:

(1) 749 units of the Richelle garments;

(2) 2,388 units of Sienna garments; and

(3) 8,155 units of the Rosette garments.

The Relevant legislation and legal principles

215 Section 10 of the Copyright Act defines “artistic work” as:

(a) a painting, sculpture, drawing, engraving or photograph, whether the work is of artistic quality or not;

(b) a building or a model of a building, whether the building or model is of artistic quality or not; or

(c) a work of artistic craftsmanship whether or not mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b);

but does not include a circuit layout within the meaning of the Circuit Layouts Act 1989.

216 Section 10 of the Copyright Act defines “drawing” to include a “diagram, map, chart or plan”.

217 Subject to the respondent’s submission that copyright did not subsist in the Senorita artwork discussed below, it was not disputed that each of Seafolly’s English Rose, Covent Garden and Senorita artworks constituted an artistic work within the meaning of s 10(a) of the Copyright Act.

218 The Copyright Act confers a number of exclusive rights on the owner of copyright in works and other subject-matters.

219 Section 31(1)(b) of the Copyright Act relevantly provides that:

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

…

(b) in the case of an artistic work, to do all or any of the following acts:

(i) to reproduce the work in a material form;

(ii) to publish the work;

(iii) to communicate the work to the public; …

220 Section 36(1) of the Copyright Act provides:

36 Infringement by doing acts comprised in the copyright

(1) Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

221 Section 14(1) of the Copyright Act provides:

14 Acts done in relation to substantial part of work or other subject-matter deemed to be done in relation to the whole

(1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

(a) a reference to the doing of an act in relation to a work or other subject-matter shall be read as including a reference to the doing of that act in relation to a substantial part of the work or other subject-matter; and

(b) a reference to a reproduction, adaptation or copy of a work shall be read as including a reference to a reproduction, adaptation or copy of a substantial part of the work, as the case may be.

222 Accordingly, by the combined effect of ss 36(1) and 14(1) of the Copyright Act, the applicant had the exclusive right to reproduce in a material form a substantial part of the English Rose and Covent Garden artworks and (subject to the subsistence of copyright) the Senorita artwork. It was not contended that the respondent had the applicant’s licence or authority to do any of the acts comprised in its copyright.

223 In contrast to the exclusive rights which, by s 31(1)(a), comprise the copyright in literary, dramatic and musical works, the exclusive rights which, by s 31(1)(b), comprise the copyright in artistic works, do not include the right to make an adaptation.

224 The respondent contended that, from the omission of the exclusive right to make an adaptation, it followed that the adaptation of an artistic work was not the exclusive province of the copyright owner but was free to all. Accordingly, the infringement of an artistic work required a strict, faithful and exact reproduction, as anything short of that would simply constitute an adaptation which the copyright owner was not entitled to restrain.

225 In my opinion, that submission, for which no specific authority was identified, is contrary to well-established principles.