FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 241

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

UPON the applicants by their Counsel jointly and severally undertaking:

(a) to submit to such order (if any) as the Court may consider to be just for the payment of compensation, to be assessed by the Court or as it may direct, to any person, whether or not a party, adversely affected by the operation of the interlocutory order in paragraph 1 below and the interlocutory undertakings in sub-paragraphs (d) and (e) below or any continuation (with or without variation) thereof;

(b) to pay the compensation referred to in (a) above to the person there referred to; and

(c) to notify the respondent's solicitors promptly if Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd's accounts record a net asset position of less than $20 million.

AND UPON the respondent by its Counsel undertaking:

(d) that it will not market or supply any pregabalin products to hospitals until final hearing and determination of the proceeding, and

(e) that it will keep accounts of all pregabalin sales in other channels.

1. Until the final hearing and determination of the proceeding or further order, the respondent, whether by itself, its directors, officers, employees or agents, or otherwise, be restrained from:

(a) importing, making, selling, supplying or otherwise disposing of, or offering to import, make, sell, supply or otherwise dispose of, or using or keeping for the purpose of doing any of the foregoing, in the patent area (as that term is defined in the Patents Act 1990 (Cth)) and without the licence or authority of the applicant, any of the following products:

(A) any product containing pregabalin which is indicated for “the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults” (or any substantially similar indication) with or without any other indication.

2. The respondent’s costs of and incidental to the interlocutory application be the respondent’s costs in the cause.

3. The interlocutory application otherwise be dismissed.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The respondent has informed the applicants that, while the order in paragraph 1 above is in force, it will not apply for listing of any product referred to in that order under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 199 of 2014 |

| BETWEEN: | WARNER-LAMBERT COMPANY LLC First Applicant PF PRISM CV Second Applicant PFIZER IRELAND PHARMACEUTICALS Third Applicant PFIZER ASIA PACIFIC PTE LTD Fourth Applicant PFIZER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 008 422 348 Fifth Applicant |

| AND: | APOTEX PTY LTD ACN 096 916 148 Respondent |

| JUDGE: | GRIFFITHS J |

| DATE: | 18 MARCH 2014 |

| PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 The first applicant, Warner-Lambert Company LLC (Warner-Lambert) is a member of the Pfizer group of companies. Warner-Lambert is the patentee of Australian Patent No 714980, which is entitled “Isobutylgaba and its derivatives for the treatment of pain” (the Pain Patent). In general terms, the Pain Patent relates to the use of certain compounds, relevantly including a compound called pregabalin, for the treatment of pain and in the manufacture of medicines for the treatment of pain. Claim 1 of the Pain Patent (which is the only claim relied upon by the applicants for the purposes of their interlocutory application) is to:

A method for treating pain comprising administering a therapeutically effective amount of a compound of Formula 1… [which includes pregabalin].

2 It is to be noted that the claim refers to the treatment of pain in general terms and is not limited to the treatment of any particular sub-category of pain, such as “neuropathic pain” (which, generally speaking, means pain which arises from damage to or a disorder of the nervous system).

3 The fifth applicant, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd is the exclusive licensee of the Pain Patent. One of Pfizer’s leading pharmaceutical products in Australia is a product called Lyrica, which contains pregabalin. Lyrica is the Pfizer group’s second biggest product by revenue in Australia. On 13 April 2005, Lyrica was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). The indications for Lyrica reported on the ARTG are:

(1) “for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults” (neuropathic pain indication); and

(2) “as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation” (seizure indication).

4 For many years Lyrica was not listed under the Commonwealth Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which meant that it attracted no government subsidy. It was not until March 2013 that Lyrica became eligible for such a subsidy when it was listed on the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits (SPB). Significantly the only indication for which Lyrica is listed on the SPB (as opposed to the ARTG), is for the treatment of neuropathic pain in circumstances where the condition is refractory to treatment with other drugs (i.e. Lyrica is used as a second line after treatment by other drugs has failed). This means that where pregabalin is prescribed for the treatment of pain other than neuropathic pain, the supply has to occur outside the PBS, which will involve the use of a private or non-PBS prescription and not attract any government subsidy.

5 The respondent (Apotex) is a major supplier of generic pharmaceutical products in Australia. It has obtained regulatory approval to supply a number of pharmaceutical products containing pregabalin (the Apotex Products). Those products were approved on the basis of the bioequivalence with Pfizer’s Lyrica product. Apotex’s regulatory approval was obtained in September 2012 but it only recently took steps to announce the launch of the Apotex Products on 14 March 2014.

6 When the Apotex Products were first registered on the ARTG in September 2012, the reported indications were similar to both the neuropathic pain and seizure indications for Lyrica. Significantly, the registered indications for the Apotex Products were amended on the ARTG in October 2013 so as to delete the indication relating to neuropathic pain and to retain only the seizure indication.

7 Thus the Apotex Products are currently registered on the ARTG in terms which reflect only the seizures indication for Lyrica, namely: “Pregabalin is indicated as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation”. The approved product information document relating to the Apotex Products relevantly states:

INDICATIONS

Pregabalin is indicated as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation.

8 The applicants claim that Apotex is threatening to infringe the Pain Patent and they seek final and interlocutory relief restraining such infringement. There was some urgency in the proceedings given the imminent launch date.

9 As will emerge further below, there is a twist in the proceeding in that the applicants allege an infringement of the Pain Patent and not another patent held by another company in the Pfizer group of companies (Pfizer Inc), together with North-Western University. That other patent is patent No 677008, which claims both the compound pregabalin and a “method of treating a patient having seizure disorders which includes administering to the patient an effective amount of a compound which is [a list that specifically includes pregabalin]” (the Seizure Patent). The interlocutory application seeks to restrain Apotex’s launch of four doses of the Apotex Products. Accordingly, as the respondent emphasises, the applicants rely on the Pain Patent and not the Seizure Patent in seeking to restrain Apotex launching a product whose indications are limited to seizures. It should also be noted that, for the purposes of the interlocutory application, the parties were agreed that no issue arises as to the validity of the Pain Patent.

Procedural background

10 In mid-2013, Apotex commenced proceedings in the Court seeking revocation of both the Pain Patent and the Seizure Patent (NSD 763 of 2013). By consent, the part of the proceedings which dealt with the Seizure Patent was discontinued in October 2013. The main proceedings continue in respect of the claim to revoke the Pain Patent.

11 In late November 2012, the then solicitors acting for Warner-Lambert and other Pfizer companies, wrote to Apotex and drew attention to their clients’ rights and interests in inter alia the Pain Patent and the Seizure Patent. The letter warned Apotex of the risk of a breach of ss 117(1) and 117(2)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) if it supplied a pregabalin product in Australia for use in the treatment of a patient with a seizure disorder. After an exchange of correspondence, the solicitors for Apotex wrote a letter dated 14 December 2012 in which they gave an undertaking that their client would not launch, supply or offer for supply any pregabalin product before 1 March 2013. Subsequently, on 21 December 2012, Apotex’s solicitors gave a further undertaking that Apotex would give 4 weeks’ notice to Pfizer of any intended launch of a product containing pregabalin.

12 On 14 February 2014, notice was given to the applicants of Apotex’s intention to launch some products containing pregabalin on or after Friday 14 March 2014. The applicants were told that the relevant products were indicated “as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation”. The letter also enclosed copies of early drafts of proposed letters which Apotex intended to send to pharmacies and doctors in connection with the launch of the Apotex Products.

13 On 25 February 2014, Warner-Lambert commenced the present proceedings seeking interlocutory relief. On 27 February 2014, the docket judge gave directions with a view to the interlocutory application being heard promptly, which included directions for the filing of evidence in chief and the exchange of “short” written submissions. The hearing of the interlocutory application came before me as duty judge. To accommodate the convenience of the applicants’ junior counsel, the hearing was not able to start until 11 am on Thursday, 13 March 2014. The parties filed a total of 9 affidavits, many of them of significant length and with multiple annexures. The applicants prepared what was described as an “Outline of Submissions” which totalled 39 pages. The respondent’s “Outline” totalled 18 pages. No witness was required for cross-examination.

14 At the commencement of the hearing, and without opposition, leave was given to amend the interlocutory application by joining additional companies within the Pfizer group of companies. The hearing concluded at approximately 5 pm on 13 March 2014.

15 Orders were made at 4.15 pm on 14 March 2014, which dismissed the applicants’ application for interlocutory relief in respect of the supply of products by Apotex containing pregabalin for treatment of seizures. The parties were advised then that, having regard to my commitments as duty judge, there had been insufficient time to finalise reasons for judgment and that they would be provided as soon as was practicable.

Registration and listing of pharmaceutical products

16 A pharmaceutical product may not be marketed, supplied, offered for sale, sold or distributed within Australia unless it is listed or registered on the ARTG. The registration of a pharmaceutical product must include at least one indication for the product within Australia.

17 The PBS is maintained by the Commonwealth under the National Health Act 1953 (Cth). Under the PBS, the government subsidises the costs of medicines for many medical conditions. Medicines which are eligible for such subsidisation have to be listed on the SPB.

18 Pharmacists are paid by the government for dispensing items which are on the SPB. If a medicine is not listed on the SPB a pharmacist cannot supply a prescription for that medicine under the PBS and the patient has to pay the full price for the medicine under a “private” or “non-PBS” prescription. This means that the prescription is not subsidised by the government. Whereas the PBS price is a fixed price (while allowing for concessions), the price charged for non-PBS medicines may differ across pharmacies.

19 Some medications on the SPB are subsidised only for a specific patient group or indication. If a medicine is listed on the SPB for a particular indication, and the patient’s clinical condition does not match the indication, the prescription is not eligible to be supplied on the PBS, but can still be dispensed as a private prescription.

20 An amount known as the “co-payment” is the amount which a patient pays towards the cost of their PBS medicine. From 1 January 2014, patients pay up to $36.90 for most PBS medicines or $6 if they have a concession card (that figure drops to zero once a patient’s expenditure on pharmaceutical products reaches a certain level).

21 The supply of prescription medicines to consumers is regulated by relevant state and territory poisons legislation (Poisons Legislation). This legislation interacts with and supplements Commonwealth legislation which regulates therapeutic goods. The active chemical substances in prescription drugs are listed in Schedule 4 to the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (the Poisons Standard). While a medicine has to be registered for particular indications under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (the TGA), the Poisons Standard only lists the relevant chemical substances in a drug and does not refer to the indication or uses for such substances. Accordingly, a prescription can be given for a non-ARTG registered indication, as long as the prescription is in accordance with the considerations set out in the relevant Poisons Legislation. Such prescriptions are known in the industry as “off-label” prescriptions. They can be given by a medical practitioner or any other health professional who is capable of legally issuing a prescription.

22 In most cases, medical practitioners prescribe the brand name of a prescription medicine, except in the case of hospitals where the practice is to use generic names.

23 I will now provide a broad summary of the relevant evidence adduced by the parties, while noting that, in view of the urgency of the matter, the summary will necessarily be at a higher level of generality and less comprehensive than would otherwise be the case.

Summary of the applicants’ evidence

24 A pharmacist, Dr Shane Jackson, gave evidence for the applicants in which he outlined the marketing of generic medicines. I accept that evidence, which may be summarised as follows.

25 Generic suppliers typically aim to persuade pharmacists to supply a generic product to patients who hold a prescription for the original brand of a particular medicine. Generic suppliers achieve this by providing pharmacists with a financial incentive, usually in the form of a discount or rebate. This means that if the pharmacist supplies a generic product instead of the original brand, the pharmacist will make a greater return. Provided there is no safety issue for the patient and relevant legal requirements are met, this is generally recognised by pharmacists as an acceptable and sensible business practice. Generic suppliers do not normally market their products to medical practitioners. Rather, they direct their marketing to pharmacists with a view to persuading them to substitute generic products at the pharmacy level.

26 Prescribers have a discretion as to whether to prevent brand substitution under a PBS prescription by “ticking a box” on a standard PBS prescription form which appears alongside the words “brand substitution not permitted”.

27 A pharmacist may offer a PBS listed generic substitute to a patient, and claim a PBS subsidy, if:

(a) the patient agrees to the substitution;

(b) the prescription does not prevent such substitution;

(c) the brands are identified in the SPB as interchangeable; and

(d) substitution is permitted under Poisons Legislation.

28 If a medical practitioner writes a prescription, whether PBS or non-PBS, for a particular pharmaceutical product, whether or not a particular brand is specified, and the pharmacist is aware that there is an alternative brand of the same pharmaceutical substance registered on the ARTG and available to the pharmacist, the pharmacist is entitled to supply that alternative brand. Accordingly, irrespective of any PBS requirements, a pharmacist may legally dispense and supply a generic medicine to a patient holding a private prescription for the original prescribed brand. A pharmacist may also supply a generic non-PBS medicine to a patient with a PBS prescription after consulting with the patient. That applies even if the box is ticked alongside the brand substitution statement because that box applies only to PBS prescriptions. If, however, the pharmacist substitutes a non-PBS medicine, the pharmacist is not entitled to claim a subsidy under the PBS.

29 As a matter of practice, supplying a substitute product in the manner described above makes practical sense where the non-PBS subsidised cost of the medicine is less than the PBS patient co-payment. Dr Jackson gave evidence that he was aware of cases where substitution of non-PBS products had occurred on a very large scale where discount pharmacies, such as warehouse pharmacies, advertise a private label at a heavily discounted price.

30 Dr Jackson described private-label substitution as follows. The usual combined subsidy and margin on the dispensing of an original brand to a patient under the PBS is approximately $13 per product. However, if a generic company can supply the pharmacist with a product at say $10, the pharmacist may charge the patient an amount such as $30. This means that the pharmacist increases his or her return from $13 to $20, and the patient gets a $6.90 saving. In different marketing models, discount pharmacies may offer larger or smaller discounts to patients in order to gain market share or increase their margin. The net effect is that a pharmacist can make an increased return on the sale of a generic product, as compared with the sale of an original brand. Simultaneously, however, the generic supplier achieves a sale of its product at the expense of a sale by the supplier of the original brand. There is no payment made under the PBS because the supply of the generic product occurs outside the PBS.

31 Dr Jackson also described the prescription and supply of medicines in hospitals. It is unnecessary to summarise that evidence because the respondent undertook that it would not market or supply any pregabalin products to hospitals until the main proceedings have been determined.

32 Dr Jackson explained that currently there are no generic alternatives to Lyrica. Lyrica is a prescription-only drug and is listed on Schedule 4 of the Poisons Standard. Consequently, a pharmacist may only dispense that product upon a patient presenting a prescription. As noted above, Lyrica was listed on the SPB with effect from March 2013. Previously it was only available on private prescription or through hospitals. As also noted above, Lyrica is indicated on the SPB only for the treatment of neuropathic pain. If Lyrica is prescribed to treat seizures, the prescription cannot be a PBS prescription and the pharmacist would not receive any government subsidy. Dr Jackson said that in his experience the overwhelming majority of prescriptions for Lyrica are PBS prescriptions for neuropathic pain.

33 Dr Jackson further explained that, because the Apotex Products will not be listed on the SPB, they will not be flagged there as interchangeable with Lyrica. This means that pharmacists could not legally substitute the Apotex Products for Lyrica and claim a PBS subsidy. Dr Jackson explained, however, that while a pharmacist could not legally dispense and supply the Apotex Products in substitution for Lyrica even though the Products are not on the SPB, a pharmacist is permitted to make that substitution if the pharmacist is aware that the Apotex Products are a non-PBS bioequivalent to Lyrica which is listed on the ARTG. The PBS prescription could be converted to a private prescription (presumably with the patient’s consent).

34 Likewise, if a medical practitioner wrote a private (i.e. non-PBS) prescription for Lyrica and a pharmacist is aware that there is an alternative brand of pregabalin which is registered on the ARTG and available to the pharmacist, he or she could supply that alternative brand after consulting the patient.

35 Dr Jackson also gave evidence that, in his opinion, the letters which Apotex proposes to send to prescribers and pharmacists will have no impact on potential brand substitution. This view was expressed by reference to an earlier draft of the proposed letters which contained a statement that the Apotex Products are not “presently” indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain and also that this difference between Lyrica and the Apotex Products was “not safety related”. It should be noted that the term “presently” has been omitted from the revised letters. For reasons which I explain below, I do not accept Dr Jackson’s opinion on this topic.

36 Dr Jackson also provided an affidavit in reply. He described the concept of bioequivalence in pharmaceutical products. He adopted the definition of the concept from the Guideline on the Investigations of Bioequivalence issued by the European Medicines Agency, which is in the following terms:

Two medicinal products containing the same active substance are considered bioequivalent if they are pharmaceutically equivalent or pharmaceutical alternatives and their bioavailabilities (rate and extent) after administration in the same molar dose lie within acceptable predefined limits. The limits are set to ensure comparable in vivo performance, i.e. similarity in terms of safety and efficacy.

37 Dr Jackson said that the concept of bioequivalence and similarity in terms of safety and efficacy is fundamental to the registration of generic products. He explained that for a generic product to be registered on the ARTG, it must have been demonstrated to be the bioequivalent to the originator product. Such a generic product is registered on the ARTG in the same doses and in the same dosage form, irrespective of the indication. Dr Jackson also said that, as a general proposition, Australian pharmacists are taught and know that generic medicines are approved on the basis of evidence produced to the regulator that they are bioequivalent to the registered originator product for which full efficacy and safety data has been provided.

38 Dr Jackson also said that, while in his view a private prescription for pregabalin could be given for seizures, it is more likely that it would be for other things such as off-label uses (including for pain other than neuropathic pain) or for indicated uses as approved by the TGA but which are not PBS listed uses (such as where pregabalin is prescribed as a first line treatment rather than as a treatment for pain refractory to treatment by other drugs, which is the PBS listed restriction). Dr Jackson said that if the Apotex Products were truly dispensed only for the seizure indication, there would be no commercial reason for a pharmacy to stock the Products because they would be dispensed very rarely. I do not accept that evidence, which contradicts the market estimates provided by Pfizer in support of its unsuccessful application in 2005 to have Lyrica listed on the SPB for the seizure indication. It is also inconsistent with confidential evidence adduced by Apotex in the proceeding which sets out the prices at which it proposes to offer the Apotex Products to pharmacists for the seizure indication. In my view, there is no reason to doubt the genuineness of those figures which, although only estimates, indicate that Apotex views the seizure market as significant and it aims to acquire most of that market over time.

39 Mr John Dimopoulos also gave evidence on behalf of the applicants, both in chief and in reply. Mr Dimopoulos currently holds the position of Cardiovascular and Pain Therapy Lead of Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. He gave evidence concerning the significant funds expended by Pfizer in neuropathic pain education and awareness, including in relation to telephone hotlines which provide patient support. He also gave evidence that the Pfizer group’s costs associated with bringing Lyrica to market exceeded US$1 billion. He gave confidential evidence relating to Pfizer’s approximate revenue from sales of Lyrica in Australia in each of the past three years and its budgeted revenue for 2014. He described how Pfizer spends a significant amount of money to promote the Lyrica brand to prescribers. I accept that evidence.

40 Mr Dimopoulos said that Pfizer did not promote Lyrica for the treatment of epilepsy and he said that, to the best of his knowledge, doctors - apart from some specialists - do not prescribe Lyrica for epilepsy other than in rare cases. He said that is because there are cheaper and more effective medicines which are available to treat seizures. Accordingly, Pfizer has not commercialised Lyrica for partial seizures in Australia because it would not be economically viable to do so. To support his claims, he included a confidential annexure to his first affidavit, which extracted data from what was described as a “BEACH Survey Report” for the period March 2011 to February 2013. That survey recorded Lyrica being prescribed during that period by general practitioners in relation to 319 medical conditions, none of which was epilepsy.

41 In his affidavit in reply, Mr Dimopoulos attached a further confidential annexure which recorded data concerning the prescriptions written for Lyrica by a rotating panel of 420 doctors during the 12 months ending December 2013. He said that this data revealed that prescriptions for epilepsy comprised only 0.23% of the Lyrica prescriptions written during that period.

42 As will emerge below, Apotex submitted that the Court should not accept Mr Dimopoulos’ evidence that there is no seizure market for pregabalin in Australia.

43 Mr Dimopoulos claimed that, if the Apotex Products were launched, he expected that Pfizer would quickly and significantly reduce, and eventually cease, its education and awareness campaigns concerning neuropathic pain and its promotional activities directed at Lyrica. He estimated that Pfizer would reduce its marketing spend on Lyrica by approximately 70% and that such promotion would virtually cease within six months. He said that he expected that there would also be a reduction in both patient services and staff at Pfizer Australia. He also gave evidence of other expected adverse impacts, including on Pfizer’s expenditure on research and development and its broader business.

44 Mr Dimopoulos claimed that if the Apotex Products were introduced, Pfizer Australia would suffer losses which could not be calculated with precision, but which he estimated as being in the millions or tens of millions of dollars. He said these losses would result from lost sales to Apotex and from loss of profits for sales retained by Pfizer if, as he expected to be the case, it was forced to discount Lyrica in order to compete with the Apotex Products. He said the amount of any loss was impossible to quantify because of factors such as the complexity of the market, pricing effects and the many kinds of indirect damage to Pfizer which he expected to occur. I will deal with these matters below under the topic of the balance of convenience.

45 Mr Dimopoulos also said that if Apotex was permitted to launch the Apotex Products, he expected that another generic supplier, Generic Partners, would quickly move to launch some or all of its products after first amending their ARTG registrations to limit the approved indications to partial seizures in the manner done by Apotex Products. I do not accept that evidence because, as Apotex pointed out, Generic Partners would need to first overcome the difficulties presented by the Seizure Patent.

46 As noted above, Mr Dimopoulos said that Pfizer had not commercialised Lyrica for the treatment of seizures because there are cheaper or more effective products for that purpose which are safe and readily available. He also said that Pfizer had not sought to list Lyrica on the SPB for partial seizures. This claim is incorrect. As Apotex pointed out, Pfizer sought unsuccessfully in July 2005 to obtain such a listing. The document produced by the Department of Health relating to that unsuccessful application reveals that Pfizer had claimed in support of its application that less than 10,000 patients would be treated by pregabalin by the fourth year of SPB listing, which would involve an estimated net cost to government of listing the product for that indication at less than $10 million per year by the fourth year of listing. Those estimates took into account the stated expectation that the overall anti-epileptic market was expected to grow if the product were listed for that indication. Apotex relied upon this evidence as contradicting Pfizer’s claim that there is no market for the use of pregabalin for seizures.

47 Professor Stephan Schug gave expert evidence. Professor Schug holds the Chair of Anaesthesiology at the University of Western Australia and he is also the Director of Pain Medicine at Royal Perth Hospital. He said that, in his experience, pregabalin is rarely used as an anti-seizure medication, largely because there are well established alternatives. He also said that, to the best of his knowledge, Lyrica had not been promoted by Pfizer for this indication. As Apotex pointed out, Professor Schug’s expertise is in anaesthetics and not neurology, a consideration which I accept affects the weight to be given to his evidence on this issue.

Summary of respondent’s evidence

48 Mr Jeffrey McEvoy gave evidence for the respondent. Mr McEvoy is a pharmacist and is the National Merchandise Manager, Health, for Terry White Management, which provides management services to the Terry White Chemists group of pharmacies. He gave extensive evidence concerning pharmacists’ dispensing practices, including the writing of PBS and private prescriptions. He gave evidence that while generally a pharmacist need not consider the indication for which a product has been prescribed (because that is a matter for the prescriber), in circumstances where a pharmacist is made aware that two products with the same active ingredient have been approved for different indications on the ARTG, this could raise the issue of indications in a pharmacist’s mind. Mr McEvoy also said that pharmacists are likely to be aware of the indications for which a medicine has been registered because of the extensive marketing which normally surrounds that event but that, post-launch, and absent an amended indication, there is generally no further need for a pharmacist to refer back to the ARTG listing. I accept that evidence.

49 Mr McEvoy also gave evidence that, in the context of offering an alternative bioequivalent product to a patient instead of an original brand, a pharmacist could not and would not dispense a medicine for an indication which the pharmacist knew was not approved on the ARTG for that medicine. Mr McEvoy’s evidence was to the effect that, in his view, a pharmacist would not risk his or her professional standings on registration by proceeding to dispense a substituted product which he or she knew was not approved on the ARTG for the treatment of the same condition as the product for which a prescription has been issued. I accept that evidence.

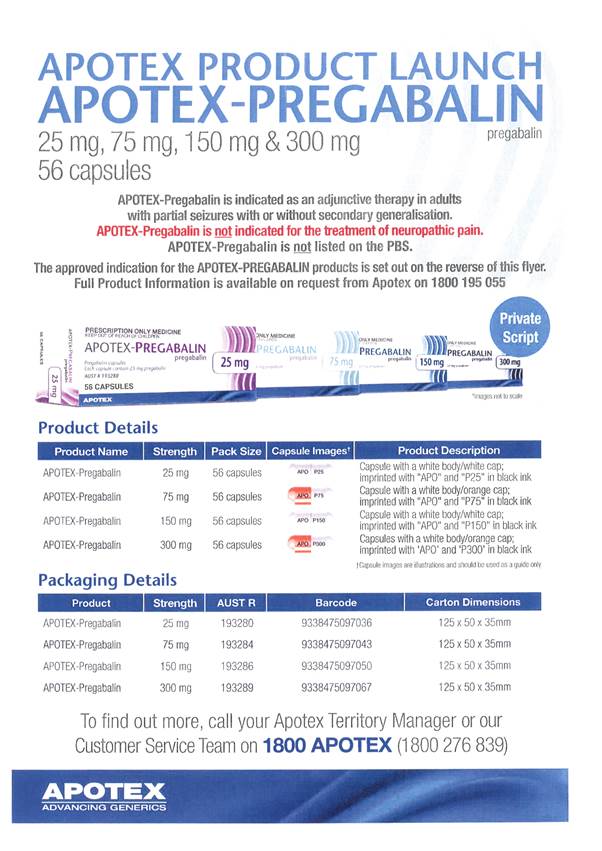

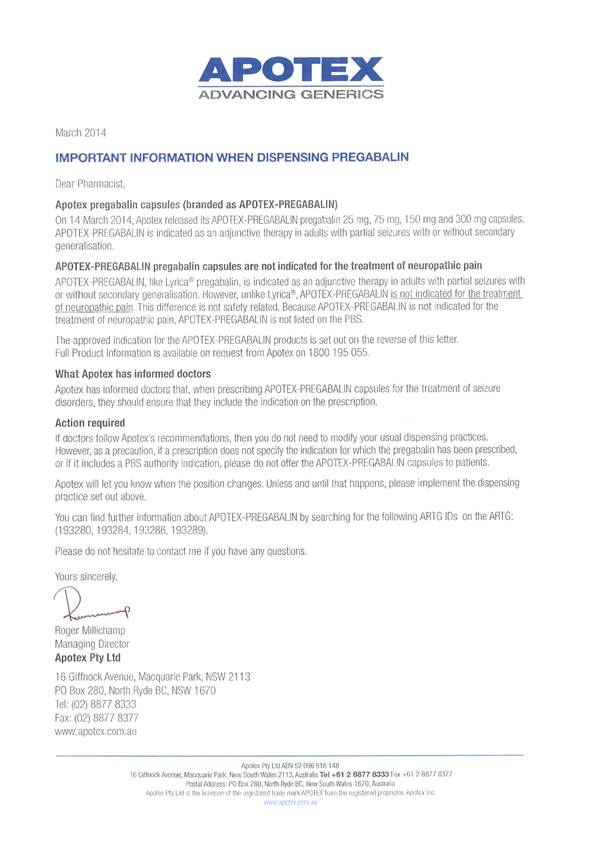

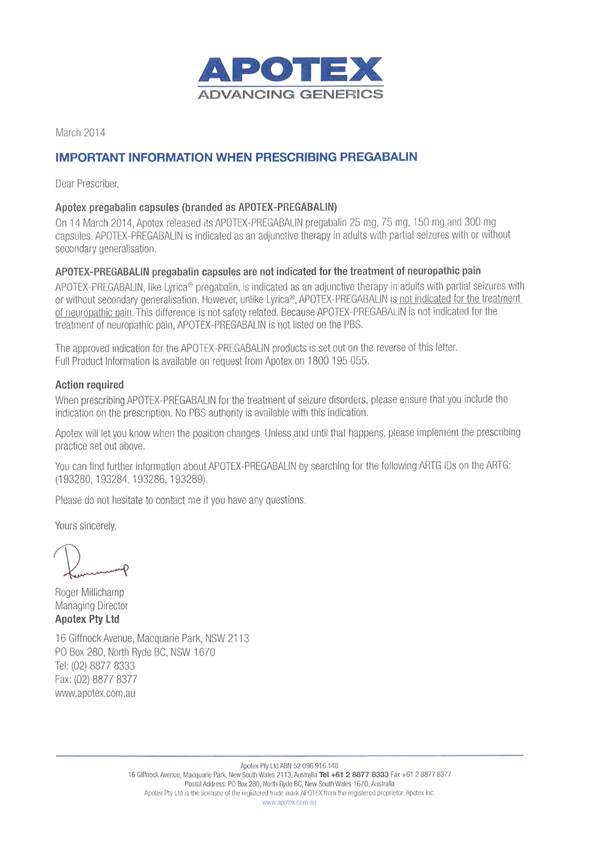

50 Evidence was also given on behalf of Apotex by Mr Roger Millichamp. He is currently Apotex’s managing director. He noted that the TGA prohibits the marketing by sponsors of therapeutic goods for any “off-label” uses. He described how Apotex had attempted to “clear the way” for marketing the Apotex Products by commencing proceedings in the Federal Court on 8 May 2013 which sought the revocation of both the Pain Patent and the Seizure Patent. He also described how the part of the proceedings relating to the Seizure Patent was discontinued by consent on confidential terms on 23 October 2013. He described how, in early August 2013, he instructed his regulatory staff to take steps to amend the product information document and approved indications for the Apotex Products to ensure that they were limited to treatment of seizures only. He described how Apotex intended to commence marketing the Apotex Products at approximately 7 pm AEST on Friday, 14 March 2014 at a national conference of pharmacists to be held on the Gold Coast.

51 Mr Millichamp described how, in preparing for that launch, Apotex had developed various promotional materials and revised letters to be sent to prescribers and pharmacists regarding the Apotex Products. As will be seen further below Apotex emphasises the statements made in those materials which highlight the limitation of the Apotex Products to the seizure indication alone. Emphasis is also placed by Apotex upon statements which appear in those materials to the effect that the Apotex Products are not listed on the PBS and, perhaps most importantly of all, that the Products are not indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

52 Set out below is a copy of an example of Apotex’s promotional materials, as well as copies of the revised letters to be sent to pharmacists and prescribers:

53 Mr Millichamp also gave evidence that he did not expect that pharmacists would substitute the Apotex Products to fill PBS prescriptions for Lyrica because there would be no profit incentive. His explanation was that Medicare data indicated that the majority of prescriptions for Lyrica processed by the PBS are for concessional patients (i.e. those who pay either $6 or nothing for their prescriptions). He agreed with Dr Jackson that private prescription supply to concessional patients did not make practical sense. He also said that it did not make sense for a prescriber to write a private prescription for Lyrica if the indication being treated was neuropathic pain because that would take the matter outside the PBS. I accept that evidence.

54 Mr Millichamp gave evidence about the advantages for Apotex in being in a “first to market position” in supplying a generic product without competition from any other generic supplier. I accept that evidence, together with his statement that Generic Partners is unable at present to offer products which are indicated for both the treatment of partial seizures and neuropathic pain. I took him to be referring to the constraints created by both the Pain Patent and the Seizure Patent.

55 I also accept Mr Millichamp’s evidence that a pharmacist or prescriber would not know of the fact of the removal of the neuropathic pain indication from the ARTG registration for the Apotex Products by merely looking at the current ARTG records. Similarly, I accept his evidence that any pharmacist or prescriber who became aware of the change in the indications would not know why the change had occurred.

56 Apotex’s solicitor, Ms Kellech Smith also gave evidence. Of particular significance to the question of the balance of convenience is her evidence regarding her experience in another set of proceedings involving Australian Patent No 597784 (the Clopidogrel Patent) and the extensive and complex damages inquiry resulting from Apotex seeking to enforce the usual undertaking as to damages in circumstances where it had been restrained by an interlocutory injunction but ultimately succeeded in its revocation application. Ms Smith estimated that there had been approximately 23 days of Court time addressing various issues in relation to the damages inquiry in that matter and she estimated that the first instance hearing would take at least six weeks. She estimated that the legal costs and disbursements incurred by Apotex to date in that damages inquiry exceeded $7 million. I accept that evidence.

57 Mr Antony Samuel gave expert evidence on the difficulties of assessing the parties’ respective damages depending on whether or not interlocutory injunctive relief was granted. Mr Samuel is a Chartered Accountant. He has been involved in numerous cases, both here in Australia and overseas, relating to compensation arising from the giving of an undertaking as to damages in intellectual property cases or assessing damages arising from patent infringements.

58 Mr Samuel gave detailed reasons in support of his conclusions that, while damages would be reasonably capable of quantification under either scenario relating to the Pain Patent, he considered that damages or an account of profits arising from patent infringement in a scenario where no interlocutory injunction is issued and the Pain Patent is ultimately found to be valid “are considerably more straightforward” than the assessment of damages arising from an undertaking as to damages” (i.e. in the scenario where an interlocutory injunction is issued and the Pain Patent is ultimately found to be invalid). As noted above, Mr Samuel was not cross-examined. I found his reasoning in support of his conclusions to be rational and convincing. His assessment is also supported by Ms Smith’s evidence concerning the complexity and expense of conducting an inquiry as to damages relating to the Clopidogrel Patent.

Relevant legal principles summarised

59 There was no dispute between the parties as to the relevant principles in determining an application for interlocutory injunctive relief in the context of a proceeding concerning an alleged infringement of a patent (no issue as to the validity of the Pain Patent was raised in the interlocutory proceedings). The relevant principles were recently described by the Full Court in GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare (UK) Ltd (2013) 103 IPR 487; [2013] FCAFC 102 at [81]:

The principles guiding the exercise of the discretion were recently described in Samsung Electronics at [44]-[74]. The relevant principles may be summarised as follows:

(a) the court's power to grant injunctive relief under either s 122 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) or s 23 of the FCA Act is expressed in very general terms, but the power to grant interlocutory relief is limited by the purpose for which it is conferred;

(b) it is relevant to take into account the specific statutory context in which interlocutory injunctive relief is sought;

(c) where the merits and the question of balance of convenience are fairly evenly balanced, there will be no injustice in requiring the party seeking interlocutory injunctive relief to demonstrate good prospects of success before imposing almost certain prejudice on the other side;

(d) where an interlocutory injunction is sought in respect of private rights, it is necessary to identify the legal or equitable rights which are to be determined at the trial and in respect of which the final relief is sought;

(e) in a case such of this, involving an application for interlocutory injunctive relief based on an infringement allegation, an assessment needs to be made of the strength of the probability of that claim succeeding at trial so as to preserve the status quo;

(f) in considering an application for an interlocutory injunction, the court must address itself to two main inquiries, namely whether the applicant has established a prima facie case in the sense explained in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd and where the balance of convenience lies;

(g) the strength of the probability of ultimate success by the applicant at trial depends upon the nature of the rights asserted and the practical consequences likely to flow from the grant of the injunction which is sought. The extent of the strength required will vary from case to case;

(h) whether or not the applicant will suffer irreparable injury or harm for which damages will not be adequate compensation is one of the matters to be addressed in the court's consideration of the balance of convenience and justice rather than as a distinct and antecedent consideration;

(i) the court should assess and compare the prejudice and hardship likely to be suffered by the respondent, third persons and the public generally if an injunction is granted, with that which is likely to be suffered by the applicant if no injunction is granted; and

(j) the question of whether there is a serious question or a prima facie case should not be considered in isolation from the balance of convenience because they involve related inquiries and the apparent strength of the parties' substantive cases will often be an important consideration to be weighed in the balance.

(Citations omitted).

60 For the purposes of this interlocutory application, the applicants confirmed that the claim of infringement rests solely on ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act. Sub-sections 117(1) and(2)(b) are in the following terms:

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

…

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product – any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use;

…

61 Both parties relied upon the High Court’s decision in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 304 ALR 1; [2013] HCA 50 (Sanofi) on the meaning and scope of that provision. The following propositions may be derived from the leading joint judgment of Crennan and Kiefel JJ on issues relating to a threatened infringement within the terms of ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act (noting that French CJ and Gageler J agreed with these parts of the joint judgment):

(a) in the context of a claim of infringement under that provision, consideration has to be given to the regulatory regime under the TGA and, in particular, to the requirements for registration or listing of therapeutic goods on the ARTG and the requirement, in the case of a restricted medicine, that the listing be accompanied by approved product information;

(b) therapeutic goods which are entered on the ARTG are taken to be “separate and distinct” from other therapeutic goods if they have a “different name”, “different indications” or “different directions for use, among other things” (see [296]);

(c) in circumstances where an item registered on the ARTG was described as being indicated for uses which specifically excluded use of a patented method identified in the claim in a patent, which exclusion was also expressed in the relevant approved product information document, that amounted to “an emphatic instruction to recipients [of the alleged infringing product] to restrict use of the product to uses other than use in accordance with the patented method identified [in the claim]” (footnotes omitted) (see [303]); and

(d) in the particular circumstances, the patentee had not shown, nor could it be inferred, that, for the purposes of s 117(2)(b), the supplier had reason to believe that the alleged infringing product would be used by recipients in accordance with the patented method, contrary to the express indications in the supplier’s approved product information document.

62 Although Hayne J was in dissent in Sanofi, his Honour also emphasised the significance of the fact that the registered indications and approved product information document expressly excluded indications which would have infringed the relevant patents in determining whether there was a threatened infringement for the purposes of s 117(2)(b), as is reflected in [170]-[172]:

Against this background of regulation, Apotex, as supplier of Apo-Leflunomide, would have reason to believe that those to whom it supplied the product would put it to the uses described in the indications with which the product was registered on the ARTG. That is, Apotex would have reason to believe that Apo-Leflunomide would be put to the use of preventing or treating either active RA or active PsA.

Apotex was not shown to have any reason to believe that Apo-Leflunomide would be put to any other use. More particularly, Apotex was not shown to have any reason to believe that Apo-Leflunomide would be put to the use of preventing or treating psoriasis not associated with manifestations of arthritic disease. The product was registered on the ARTG with an express exclusion of that indication for its use.

A person suffering active RA or active PsA may have psoriasis. Administration of an effective amount of Apo-Leflunomide to treat the active RA or active PsA would be likely to relieve the patient's psoriasis. But the Full Court was right to conclude that the claim in suit, on its proper construction, was confined to the deliberate administration of the compound to prevent or treat psoriasis. Apotex had reason to believe that Apo-Leflunomide would be put to the use of preventing or treating either active RA or active PsA, not psoriasis.

(Footnotes omitted).

63 It should be noted that, in the proceedings before me, the parties were agreed that, while the registered indications and approved product information document were highly relevant for the purposes of s 117(2)(b), they were not necessarily determinative and it might be possible to establish the requisite reason to believe by reference to other evidence or the drawing of appropriate inferences. I agree.

64 Further guidance on the scope and meaning of s 117(2)(b) is provided by the Full Court’s decision in Generic Health Pty Ltd v Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd (2013) 100 IPR 240; [2013] FCAFC 17 (Generic Health), which predates Sanofi. All members of the Court considered that the issue whether a supplier had reason to believe for the purposes of that provision involved an objective test. Emmett J stated at [35] (to similar effect see Bennett J at [103], who noted that the reason to believe must be that of the supplier and might be subjective in the sense of an actual belief or, alternatively, objective in the sense that there are reasonable grounds to believe, and see also Greenwood J at [135]):

The question is whether there were factual matters known to Generic Health that would lead a reasonable person to believe that the GH products would be put to an infringing use. It is not to the point that Generic Health, through its relevant officers, did not actually have such a belief. The question is whether there was material before the primary judge that could support a finding that a reasonable person in the position of Generic Health would have reason to hold such a belief.

Consideration

65 The first question is whether the applicants have demonstrated, by reference to the evidence as it currently stands, that they have a prima facie case that Apotex’s proposed supply of the Apotex Products will infringe the Pain Patent within the meaning of ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act. For the following reasons, I consider that the applicants have not met that threshold or, if they have, their case is a weak one.

66 For the purposes of the interlocutory hearing there was no dispute that the Apotex Products are not a staple commercial product within the meaning of s 117(2)(b). And, as noted above, no issue as to the validity of the Pain Patent arises at this stage.

67 The primary issue is whether the applicants have established a prima facie case that Apotex has the requisite reason to believe that the Apotex Products will be used in a manner which infringes the Pain Patent. In his closing address, Mr Catterns QC (who together with Mr Murray, appeared for Apotex) submitted that the applicants’ case had shifted from its early emphasis on PBS substitution to private prescriptions. He described the core question in the case as presented by the applicants as: “to what extent will there be private prescriptions outside PBS neuropathic pain refractory to other drugs but inside the [Pain Patent], that Apotex has reason to believe will be answered with its seizure product”. I understood that this description of the central issue was not disputed by Mr Macaw SC who, together with Mr Dimitriadis, appeared for the applicants. Mr Macaw also submitted that the applicants’ reliance on private prescriptions was not new.

68 The applicants contended that they have a strong prima facie case under ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act for the following primary reasons:

(a) Apotex has effectively conceded that use or supply of the Apotex Products for the treatment of pain would infringe the Pain Patent by Apotex submitting to an interlocutory injunction in relation to the neuropathic pain indication;

(b) no significance should attach to the fact that the ARTG registered indications for the Apotex Products have been narrowed so as to be confined to the seizure indication, because pharmacists are aware that the Apotex Products were previously approved for both that indication and the neuropathic pain indication on the basis of the Apotex Products’ bioequivalence with Lyrica;

(c) the evidence indicates that, as a matter of fact, the Apotex Products will be used for the treatment of pain, including neuropathic pain and that Apotex has the requisite reason to believe that this is the case. In support of this latter contention, the applicants say that there is no market in Australia for the use of pregabalin in the treatment of seizures and that Apotex must believe that the Products will be substituted for Lyrica in the treatment of pain, including neuropathic pain;

(d) the letters which Apotex proposes to send to medical practitioners and pharmacists will have no material effect in preventing such substitution because pharmacists will proceed on the basis of their knowledge of the bioequivalence of Lyrica and the Apotex Products; and

(e) Sanofi is distinguishable, not only because of the difference in the text of the relevant registered indications but also because the evidence here indicates that the seizure indication is not in fact used in practice.

69 For the following reasons, I am not persuaded on the current evidence that the applicants have established a prima facie case of infringement based on ss 117(1) and (2)(b). Alternatively, if I am wrong in that regard, I consider that their case is relatively weak.

70 First, I do not accept that, for the purposes of interlocutory application, the applicants have made good their claim that there is essentially no market in Australia for pregabalin for the seizure indication. That claim provided the foundation for their argument that the narrowing of the registered indications for the Apotex Products was merely “cosmetic” and “artificial” and that Apotex must realise that the Apotex Products will in fact be used in the treatment of pain, including the neuropathic pain indication. In my view, the applicants have failed to demonstrate that there is a serious question to be tried in circumstances where:

(a) Pfizer itself unsuccessfully applied in 2005 to have Lyrica listed on the SPB for the seizures indication which suggests that, at that time, Pfizer considered that there was or could be a seizures market for pregabalin in Australia;

(b) the confidential annexures to Mr Dimopoulos’ affidavits do not support Pfizer’s argument. As Apotex pointed out, it appears from the first of those annexures that 13.5% of the prescriptions for Lyrica were for conditions which were described as “Neurological symptom/complaint, other” and “Neurological disease, other”, which were broad enough to include epilepsy as a neurological disease or complaint, as well as seizures which may result from it. Similarly, Mr Dimopoulos’ second confidential annexure provides a figure of 12.02% of Lyrica prescriptions being for what is described as “unknown/unspecified cause morbidity”, which could include neurological diseases not falling within the Pain Patent. In my view, there is force in Apotex’s contention that the applicants failed to “disentangle” the data in the second confidential annexure;

(c) the approved product information for Lyrica goes to some lengths to describe the seizure indication and how Lyrica is indicated as an adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation. The Lyrica Consumer Medicine Information includes the following statements as to what Lyrica is used for:

Lyrica is also used to control epilepsy. Epilepsy is a condition where you have repeated seizures (fits). There are many different types of seizures, ranging from mild to severe.

Lyrica belongs to a group of medicines called anticonvulsants. These medicines are thought to work by controlling brain chemicals which send signals to nerves so that seizures do not happen

, and

(d) as noted above, I do not consider that there is any demonstrated reason to doubt the genuineness of Apotex’s own assessment that there is a viable non-PBS market for the use of pregabalin in the treatment of seizures.

71 Secondly, I also accept Apotex’s submission that the applicants have provided no evidence that shows the extent, if any, of pain indications that are outside the neuropathic pain indication but are within the claims of the Pain Patent. On the current evidence, the Court cannot reliably assess the size of the non-PBS pain market.

72 Thirdly, I consider that the Apotex promotional materials, including the revised letters to be sent to medical practitioners and pharmacists, contradict the applicants’ claim that Apotex has the requisite belief for the purposes of ss 117(1) and (2)(b). These materials give particular prominence to the fact that the Apotex Products are not indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain and are not listed on the PBS. The letters expressly state that, unlike Lyrica, the Apotex Products are not indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Moreover, prescribers will be informed that, when prescribing the Apotex Products for the treatment of seizure disorders, that indication should be shown on the prescription. And pharmacists will be informed that, if the prescription does not specify the indication for which pregabalin has been prescribed, or if it includes a PBS authority indication, they should not offer the Apotex Products to patients. It should also be noted the approved product information for the Apotex Products deals exclusively with their use for the treatment of epilepsy and seizures, not pain.

73 Relying on Dr Jackson’s evidence to the effect that the letters would have no impact on potential brand substitution, the applicants argued that the Court should find that pharmacists will not be deterred from substituting the Apotex Products based upon their knowledge of their bioequivalence with Lyrica. I do not accept that argument, which is unsupported by any evidence and is based on mere speculation and assertion. It might also be noted that, notwithstanding Apotex’s willingness to delete from those materials the reference to the differences in indications not being “safety related” (see [35] above), the applicants opposed any such amendment on the basis that it would be misleading.

74 The critical issue for the purposes of ss 117(1) and (2)(b) is whether the applicants have established a prima facie case that Apotex has the requisite reason to believe. In my opinion, the contents of the promotional materials and proposed letters, when coupled with the narrowed ARTG registered indication and approved product information, provide strong evidence which is inconsistent with the applicants’ claims. The in principle significance of such “emphatic instructions” was emphasised in Sanofi at [304] per Crennan and Kiefel JJ in the context of s 117(2)(b). In my opinion, in this particular context, any general knowledge which pharmacists have about the bioequivalence of the relevant products will not be sufficient to displace such express and emphatic statements. The position might be different if there was evidence indicating that, despite those materials, Apotex was taking steps to encourage substitution of the Apotex Products in circumstances which would infringe the Pain Patent. But that is not the case at present.

75 In my view, the circumstances here are different from those which were the subject of Jagot J’s observations in Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No 3) (2012) 95 IPR 581; [2012] FCA 265 at [20], upon which the applicants relied. Her Honour said there:

[T]he additional instructions and undertakings proposed by Apotex also do not persuade me to reach a conclusion different from that Rares J reached and, indeed, I reached in Watson Pharma. Again, Apotex has not pointed to any evidence suggesting any therapeutic efficacy or safety issue with the prescription of Apotex's generic rosuvastatin product to treat HeFH. It is obvious that Apotex's generic rosuvastatin product will be equally capable of treating HeFH as Astra's product, Crestor. Apotex's entire scheme of proposed instructions to doctors, pharmacists and patients is founded on the apparent but in evidentiary terms unsupported belief that doctors, pharmacists and patients will be willing to overlook the scientific reality (that Apotex's generic rosuvastatin product will be equally capable of treating HeFH as Astra's product, Crestor) and in so far as their own price incentives might be concerned wholly disregard those incentives for the purpose only of ensuring that Apotex has no reason to believe that its product might be used to infringe one of Astra's patents. I do not accept that the scheme is practical or likely to be efficacious. In any event, in so far as reasonably practicable, doctors and pharmacists should not be burdened by court-mandated instructions from a pharmaceutical company that have no therapeutic efficacy or safety purpose and which are intended to do nothing other than to aid the pharmaceutical company to avoid an alleged patent infringement pending the final resolution of disputed issues between the parties. This is a strong reason not to accept the scheme of undertakings Apotex proposes…

76 It should be noted that those observations at the interlocutory stage were directed to “court-mandated instructions” and not voluntary steps taken by the generic supplier as is the case here. Moreover, it is also relevant to take into account her Honour’s subsequent statements on this topic in Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No 4) [2013] FCA 162 at [517], in which her Honour emphasised an applicant’s burden of proof:

… As to s 117(2)(b), I remain of the view that “doctors and pharmacists should not be burdened by court-mandated instructions from a pharmaceutical company that have no therapeutic efficacy or safety purpose and which are intended to do nothing other than to aid the pharmaceutical company to avoid an alleged patent infringement” (Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No 3) (2012) 95 IPR 581; [2012] FCA 265 at [20]). But this is a policy view and the question is not whether the generic parties have proved that their (sic) will be no infringement, but whether AZ has proved that, in the face of the product information, a generic rosuvastatin product will be used by some person to treat HeFH. In the case of Apotex and Watson that inference cannot be drawn given the terms of their product information.

77 If I am wrong in concluding that the applicants have failed to establish a prima facie case, I would nevertheless describe their case based on ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act as weak. The weakness of the case is also relevant to the balance of convenience (see Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 286 ALR 257; [2011] FCAFC 156 at [59] (Samsung)). In my view, the balance of convenience favours Apotex in any event. In particular, I accept and prefer Mr Samuel’s evidence that an assessment of the applicants’ damages in the event that Apotex is not restrained and the applicants ultimately succeed in establishing infringement of the Pain Patent, will be more straightforward than the alternative scenario of assessing Apotex’s damages if it is restrained and later seeks to enforce the undertaking as to damages if the applicants fail. As Mr Samuel pointed out, the difficulties of estimating Apotex’s compensation arising from an undertaking as to damages relate to such matters as:

(a) having to estimate lost profits on the Apotex Products during and after the period of restraint despite the absence of any trading or accounting records during the period of restraint;

(b) difficulties in determining Apotex’s hypothetical market share absent an interlocutory injunction and the rate at which that market share would be achieved, which assessment will be subject to assumptions, lay evidence and possibly expert evidence and may be further complicated if additional competitors emerge at a later stage;

(c) similar difficulties will complicate the assessment of Apotex’s hypothetical price; and

(d) Apotex’s loss period could extend far beyond the period in which it is prevented from supplying the Apotex Products due to the time period it is likely to take for the hypothetical price and market share to equal its future actual price and market share once it enters the market.

78 I also accept and prefer Mr Samuel’s expert evidence that determining the quantum of compensation for the applicants is likely to be less complex in circumstances where that assessment would rely predominantly on:

(a) the actual volume of infringing sales made by Apotex (which should be capable of being substantially determined from its accounting and trading records);

(b) the actual profit levels achieved by the relevant applicant companies prior to the Apotex Products entering the market (which should also be capable of being determined from those companies’ trading and accounting records); and

(c) an assessment of the prices which would have been charged by the relevant applicant companies absent infringement (which should be capable of reasonable estimation from price trends prior to infringement).

79 I prefer Mr Samuel’s evidence on this topic to that of Mr Dimopoulos. Mr Dimopoulos said that the quantification of the applicants’ losses if Apotex was not restrained were not easily quantifiable because of the difficulty of knowing the various uses to which the Apotex Products will be put, the likelihood that other generic suppliers would follow Apotex into the market and the likelihood of Pfizer curtailing and ceasing its educational and promotional activities for Lyrica. In my view, while there may be some practical difficulties in identifying the uses to which the Apotex Products are put, they are not likely to be insurmountable nor of a magnitude which warrants significant weight. For the reasons given above, I do not accept the claim that other generic suppliers will copy Apotex, having regard to the Seizure Patent. Finally, for reasons which I will develop further below, I do not consider that much weight should be given to the claims that Pfizer will reduce and then terminate its promotional activities for Lyrica.

80 I also accept and prefer Mr Samuel’s evidence that, relatively speaking, an account of profits would be the easiest amount to quantify with precision as it would rely predominantly on the actual volume of infringing sales made by Apotex and the actual profit levels achieved by Apotex (both of which should be readily determined from the company’s accounting and trading records). Apotex has undertaken to keep relevant accounts.

81 I have not been persuaded by the applicants that they will suffer irreparable harm if Apotex is not restrained and the applicants succeed in defending the validity of the Pain Patent and establish infringement. As matters currently stand, Pfizer holds a monopoly position in the supply of pregabalin. If the applicants ultimately succeed in establishing patent infringement, it can be assumed that any sales of the Apotex Products in the interim would have been made by the applicants if a restraint had been in place.

82 I accept that the proposed trade of Apotex in supplying the Apotex Products is new, while the trade of the applicants in Lyrica is old and established and still growing. That is a matter which is given particular weight in some cases, including Pharmacia Italia S.p.A v Interpharma Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 397; [2005] FCA 1675 at [52]. But I do not consider that it is a factor which warrants much weight in this case, particularly having regard to the weakness of the applicants’ case based on ss 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Act and the currently available evidence.

83 I do not accept the applicants’ contention that there has been any relevant delay on the part of Apotex. In particular, I do not regard the circumstances here as attracting the observations made by the Full Court in Samsung at [194] concerning a generic product supplier who chooses to wait until there is insufficient time between notifying the patentee of its intentions and the launch date of its generic product. As noted above, Apotex honoured the undertaking it gave to the applicants’ former solicitor that they would be given four weeks’ notice of the launch date. And while it is true that internal steps were taken by Apotex as early as August 2013, and without informing Pfizer, to amend the approved product information document and ARTG registered indications so as to limit the Apotex Products to the seizure indication only, I do not consider that this constituted inappropriate conduct which should weigh upon the Court’s discretion.

84 Furthermore, this is a case where Apotex has sought to “clear the way”, having regard to the proceedings commenced by it last year in respect of both the relevant patents, which resulted in an agreement between the parties to discontinue the challenge to the Seizure Patent. Nor do I consider that any particular significance should attach to the fact that Apotex has submitted to an interlocutory injunction in relation to the Apotex Products with the amended neuropathic pain indication.

85 Finally, the many matters raised by Mr Dimopoulos in support of the applicants’ claims regarding the balance of convenience turn on the likelihood that the Apotex Products will be used in a manner which infringes the Pain Patent. For reasons given above, I do not accept that the applicants’ evidence in this interlocutory proceeding provides an adequate foundation for Mr Dimopoulos’ concerns.

86 Insofar as public interest considerations are relevant, I consider that they favour Apotex’s position. Restraining the supply of the Apotex Products will deprive seizure patients of a choice of products and at a potentially cheaper price. I accept that it is in the public interest that Pfizer continue to undertake the education and patient support programs of the sort described above to assist medical practitioners and patients in relation to neuropathic pain. On the basis of the currently available evidence, however, I do not accept that the applicants have established a sufficient and objective evidentiary basis to justify the concerns expressed by Mr Dimopoulos relating to these matters.

87 For these reasons, I made the orders on 14 March 2014 which, for completeness, are also set out at the beginning of these reasons for judgement.

| I certify that the preceding eighty-seven (87) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Griffiths. |

Associate: