FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Damorgold Pty Ltd v JAI Products Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 150

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Damorgold Pty Ltd v JAI Products Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 150

CORRIGENDUM

1. In paragraph 35 at 1.7 the words “the fixed shaft” should be replaced with the words “said fixed shaft”.

2. In paragraph 59 at 24.57 the word “is” should be replaced with the word “being”.

3. In paragraph 59 at 24.58 the word “is” should be replaced with the word “being”.

4. In paragraph 60 at 25.60 the word “are” should be replaced with the word “being”.

5. In paragraph 60 at 25.61 the word “is” should be replaced with the word “being”.

6. In paragraph 87 the word “be” should be inserted between “also” and “liable”.

7. In paragraph 103 the word “Bennet” should be replaced with the word “Bennett”.

8. In paragraph 110 the word “Giles” should be replaced with the word “Gyles”.

9. In paragraph 113 the word “claim” should be replaced with the word “claimed”.

10. In paragraph 115 the word “the” should be deleted before the word “Aspirating”.

11. In paragraph 115 the word “his” should be inserted before the word “Honour”.

12. In paragraph 118 at line 1, the word “by” should be replaced with the word “from”.

13. In paragraph 118(a) the word “of” should be inserted before the word “around”.

14. In paragraph 118(b) the word “the” should be deleted after the word “to”.

15. In paragraph 118(f) the quoted word “customer’s” should be replaced with “customers’”.

16. In paragraph 123 the word “out” should be deleted after the word “pointed”.

17. In paragraph 123 the word “have” should be replaced with the word “has”.

18. In paragraph 144 the word “proximate” should be replaced with the word “approximate”.

19. In paragraph 150 the word “publically” should be replaced with the word “publicly”.

20. In paragraph 151 at line 10, the word “were” should be replaced with the word “was”.

21. In paragraph 154 the word “dis-assembled” should be replaced with the word “dis-assemble”.

22. In paragraph 155 the word “has” should be replaced with the word “was”.

23. In paragraph 168 the word “and” should be inserted before the words “two versions”.

24. In paragraph 170 the word “disclose” should be replaced with the word “discloses”.

25. In paragraph 198 the word “the” should be inserted after the word “that”.

26. In paragraph 219 the word “effection” should be replaced with the words “effect on”.

27. In paragraph 248 the words “none were” should be replaced with the words “none was”.

28. In paragraph 263(a) the word “publically” should be replaced with the word “publicly”.

29. In paragraph 263(b) the word “were” should be replaced with the word “was”.

I certify that the preceding twenty-nine (29) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Middleton. |

Associate:

Dated: 11 March 2014

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 4:00pm on 14 March 2014, the parties confer and file and serve proposed minutes of orders reflecting these reasons and including any further directions (if necessary), and in the event of disagreement, short written submissions in support of any separately proposed minutes of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1051 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | DAMORGOLD PTY LTD (ACN 051 905 705) First Applicant VERTILUX CORPORATION PTY LTD (ACN 074 643 182) Second Applicant JAI PRODUCTS PTY LTD (ACN 126 185 377) Cross-Claimant

|

AND: | JAI PRODUCTS PTY LTD (ACN 126 185 377) Respondent DAMORGOLD PTY LTD (ACN 051 905 705) First Cross-Respondent VERTILUX CORPORATION PTY LTD (ACN 074 643 182) Second Cross-Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MIDDLETON J |

DATE: | 28 February 2014 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 The applicants are, respectively, the patentee and the exclusive licensee of Australian Patent No. 760547 (‘the Patent’), for a spring assisted blind mechanism. For convenience, I will refer to the applicants as ‘Damorgold’, unless the context otherwise requires specific mention of either applicant.

2 Damorgold allege that the respondent JAI Products Pty Ltd (‘JAI’) infringed the Patent (other than claims 18 and 28) by offering for sale and selling components of a roller blind system which, when assembled as intended, would so infringe the Patent.

3 JAI counterclaims, alleging that the Patent is invalid.

4 The issues of infringement and validity were ordered to be heard and determined separately prior to any questions of pecuniary relief. An issue arose as to the exclusivity of the licence given to the second applicant by the first applicant. The parties were content to defer that issue for later determination, which may or may not remain contentious.

5 Damorgold led evidence from five witnesses:

(a) John Aspros, who worked in the window blinds industry since 1967, initially assembling products in the factory; from 1970 to 1987, as an installer of outdoor blind systems; and from 1987 to 1994, as a manufacturer of internal window furnishings and fittings including curtains, vertical blinds and roller blinds. He worked as a subcontractor for the second applicant carrying out warranty services on blinds installed in residential and office buildings. Mr Aspros’ evidence was directed to the infringement claims.

(b) Bill Hunter, who is a mechanical engineer with over 25 years’ experience. Mr Hunter gave evidence directed to the infringement claims and addressing JAI’s allegations of invalidity in response to the evidence of Dr Field (to whom I will later refer).

(c) Ross Lava, who is the Chief Executive Officer and a director of the first applicant. Amongst other things, he gave evidence of the licence of the Patent granted by the first applicant to the second applicant.

(d) Malcolm Bell, who is a partner in the firm of solicitors for Damorgold and deposed to a range of largely formal matters.

(e) Kristine van Ruiten, who is a trade marks attorney and holds a private security licence and deposed to a number of investigations she made in relation to JAI’s website.

6 JAI led evidence from five witnesses:

(a) Philip Horner, who has been a director of JAI since July 2007 and deposed to events he said took place in 1994 and 1996 in relation to a ‘spring assist’ referred to in the evidence as the RolaShades product.

(b) Bruce Field, who is a consulting engineer and until December 2010 was an associate professor at Monash University specialising in teaching and research in design graphics, and industrial innovation. Dr Field’s evidence essentially addressed JAI’s allegations of invalidity including the RolaShades product and the Toso Patent (to which I will later refer).

(c) Sandra Payne, who was formerly the office manager at JAI’s predecessor, JAI Pty Ltd and deposed to events she says took place in 1994 and 1996 in relation to the RolaShades product.

(d) Gin Wah Ang, who was involved in the Gin + Design Workshop in Singapore and gave evidence about the use of a RolaShades product in Singapore, and the receipt of a version of the RolaShades Drawing (to which I will later refer). Mr Ang knew nothing about the inner workings of the RolaShades product.

(e) Dennis Jackson, who was formerly the managing director of Faber Bentin Australia from 2005, having joined that firm as General Manager in 2004. Prior to that he was based in the UK. Mr Jackson gave evidence about what devices he says were in use outside Australia before the priority date. Mr Jackson gave evidence that mechanisms combining a spring assist with a clutch mechanism were in use by a number of European and American companies from at least 1996. Mr Jackson also gave evidence that in 2005, RolaShades Pte Ltd (a Singaporean company) (‘RolaShades’) supplied him with copies of two invoices of sales by that company of its RolaShades EzRoll. The invoices themselves have not been produced, and the RolaShades EzRoll was not able to be described.

BACKGROUND

7 In closing written submissions, Damorgold set out the background and details of the Patent, all of which were not in contention. It is convenient to refer to these matters by way of summary.

8 The Patent is entitled ‘A blind control mechanism’. The inventor was Vito Fortunato.

9 The complete application for the Patent was filed on 25 August 2000, claiming priority from provisional application No. PQ2410 made on 25 August 1999.

10 The Patent was published and became open to public inspection on 22 March 2001, and was sealed on 28 August 2003.

11 The first applicant appointed the second applicant as the licensee of the Patent with effect from 1 January 2006.

12 In or about July 2007, JAI took over the business of wholesaling window furnishing components previously carried on by JAI Pty Ltd.

13 JAI supplies its products to blind makers and wholesalers.

14 JAI’s product range includes components for roller blinds, motorised roller blinds, and motorised curtain tracks.

15 Since July 2007, the components in its roller blinds range which JAI offered for sale, sold and supplied in Australia included roller blind spring assist mechanisms or “spring assists” with model numbers SA38R, SA38L, SA45R, SA45L, SA5518R, SA5518L, SA5520R and SA5520L (‘JAI spring assists’).

16 The JAI spring assists were used in combination with “slide controls” and “blind cylinders” to form a mechanism for extending and retracting a blind. It was admitted by JAI that was the only reasonable use of JAI spring assists.

17 JAI admitted it was aware that customers who purchased JAI spring assists were likely to use them in combination with slide controls and blind cylinders to make roller blind mechanisms.

18 JAI advertised, promoted and offered for sale its range of roller blind products from a website at www.jaipl.com.au which, amongst other things, included a roller blinds “page”, a downloadable roller blind catalogue, a document entitled roller blind specifications and a downloadable roller blind “flyer”.

19 On its roller blinds “page”, JAI’s website stated JAI had designed a:

complete Roller Blind System that is robust, smooth and quiet. The Chain Mechanism is made from a high grade sun resistant Acetyl and incorporates a hardened steel wrap spring stopping mechanism. ….

Chain Mechanisms are available in 32mm, 38mm and 45mm diameter with Spring Assists for 38mm, 45mm and 55mm diameter tubes. ….

….

6 sizes of keyway tube include 32mm, 38mm thin, 38mm thick, 45 mm std, 45mm thick and 55mm. ….

20 The roller blinds “page” also included photographs of components which Mr Aspros recognised as:

(a) a pair of brackets marked 1A and 1B;

(b) a chain mechanism or side control marked 2A and associated idler marked 2B;

(c) a “spring assist” marked 3, a full length depiction of which appeared on page 7 of the roller blind catalogue; and

(d) a blind cylinder or tube marked 4.

21 From his experience in the industry, Mr Aspros also understood the reference to “spring stopping mechanism” was a reference to the winding mechanism or clutch.

22 The content of the roller blinds “flyer” is very similar to that of the roller blinds “page”.

23 The roller blinds specification consists of three charts. The first chart, headed “Tube Selection Chart” contained recommendations for the size and gauge of tube to be used for the blind cylinder according to the width and drop of the blind. So, for example, JAI recommended that a 45mm thin blind cylinder be used for a blind 2,200mm wide with a drop of 3,000mm.

24 The second chart, headed “Chain Mechanism Selection Chart”, provided recommendations for what size side control should be used. For a number of these, JAI recommended that the customer should use a spring assist with the specified side control. So for example, for blinds with a width between 1,000mm and 2,000mm with a drop between 2,700mm and 3,600mm, JAI recommended a 38mm side control with a 38mm spring assist.

25 The third chart, headed “Chain mechanism used with Adaptors & Spring Assist Selection Chart”, provided options in a number of cases where, instead of using a larger side control without a spring assist, a smaller side control was recommended, but also with an adaptor and a spring assist.

Mr Aspros deposed that the roller blinds catalogue offered for sale a roller blind system with spring assist. The spring assist system included the blind cylinders depicted on pages 1 and 2 of the catalogue, the side control and idler shown on page 3 (with three sizes) and eight types of spring assist on page 7 according to the size of blind cylinder. Other components such as brackets and chains were also listed. Accordingly, Mr Aspros concluded:

The JAI Website specifically recommends the use of spring assists for blinds of specific (larger) dimensions as is apparent from the Roller Blind Specification page.

THE PATENT

26 According to the Specification, the Patent is concerned with blinds and similar arrangements that are selectively operable between open and closed conditions, especially roller blinds.

27 The Specification broadly summarises roller blinds:

Roller blinds generally include a length of flexible material wound onto a cylinder with the roller blind operating between its open and closed conditions by rotation of the cylinder causing extension and retraction of the flexible material. Roller blinds generally include a mechanism for facilitating such operation.

28 According to the Specification, one type of such mechanisms is a “spring roller”. This type of mechanism uses a biasing spring to counterbalance the weight of the extended flexible material and a latch to stop unauthorised retraction of the material. The material can be retracted by rotating the cylinder, in an extending direction, to a position that disengages the latch, and rotating the cylinder, in a retracting direction, at a speed that will not permit the latch to reengage. This speed may be dictated by the release of the energy stored in the spring alone or as altered by manual intervention.

29 A problem with this mechanism is that it can be difficult to operate, as the specification observes:

This type of mechanism can be difficult to operate as the latch is controlled by rotation of the blind cylinder and what is a suitable speed to avoid re-engagement of the latch is variable. Furthermore the spring may retract the material at such a speed that the blind over rotates past its retracted position, which will affect the tension of the spring.

30 Another type of roller mechanism identified in the specification is the “clutch roller”:

The clutch roller includes a drive member which is operable to cause rotation of a driven member. The driven member cannot rotate unless it is rotated by the drive member. This is achieved by the driven member engaging a helical spring which grips a fixed shaft when a rotating force is applied directly to the driven member. The drive member is operable to release the grip of the helical spring and thereby cause rotation of the driven member, which is connected to the blind cylinder.

31 The Specification identifies issues with the clutch roller system:

Operation of the blind therefore requires the user to overcome the frictional resistance of the helical spring. Furthermore, the clutch roller does not include any means to counter balance the weight of the extended material. However, operation of the blind using the clutch roller mechanism is relatively accurate.

32 Accordingly, the Specification identifies objects of the invention as:

It is an object of this invention to provide a mechanism that is relatively easy to operate. It is a further object of this invention to provide such a mechanism that accommodates, at least to some extent, the weight of the extended material.

33 Two consistory clauses are set on pages 3 – 7 mirroring claims 1 and 3, and a preferred embodiment is described by reference to figures 1 and 2 (pages 7 – 12).

34 Apart from the drawings in figures 1 and 2, the Patent ends with 30 claims for a mechanism; with claims 1 and 3 being independent claims and claim 30 being an “omnibus claim”.

35 Claim 1 identifies a mechanism which is a combination of 27 integers:

36 Claim 2 adds to claim one the feature:

2.28 | said drive member is positioned between the ends of said fixed shaft |

37 Claim 3 is an independent claim for a mechanism which may be broken down into a combination of 26 features. It differs from claim 1 in that:

(a) it does not include integers 1.23 and 1.24, and

(b) includes integer 2.28.

38 Claim 4 adds to claim 3 integers 1.23 and 1.24.

39 Claim 5 adds to the claims 1, 2 and 4 the feature that:

5.29 | wherein said cylindrical surface (1.23 and 1.24) is a surface of said fixed shaft (1.3) |

40 Claim 6 adds to claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 the feature that:

6.30 | said clutch means engages directly with said cylindrical surface when in said engaged condition |

41 Claim 7 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

7.31 | said driven member extends over a substantial part of the axial length of said fixed shaft |

42 Claim 8 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

8.32 | said clutch means engages direct with both said drive member and said driven member, at least during transition from said engaged condition to said disengaged condition |

43 Claim 9 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

9.33 | said drive member is mounted on said fixed shaft; and |

9.34 | said driven member is mounted on said drive member |

44 Claim 10 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

10.35 | said drive member includes a wheel section to which a turning force can be applied |

45 Claim 11 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

11.36 | a tubular barrel section extends from one side of said wheel section away from said one extreme end of the longitudinal axis of said mechanism |

46 Claim 12 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

12.37 | a slot is formed through the wall of said tubular barrel section and extends longitudinally along said barrel section |

47 Claim 13 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

13.38 | said clutch means includes at least one helical spring surrounding said fixed shaft in substantially coaxial relationship |

13.39 | and a laterally outwardly extending finger at each end of said helical spring |

13.40 | each said finger being located between the longitudinal edges of said slot and engageable with a respective one of said edges |

48 Claim 14 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

14.41 | said driven member includes a tubular barrel portion located over the tubular barrel section of the drive member |

14.42 | and an inwardly projecting rib formed on said barrel portion extends longitudinally thereof and is located within said slot of the drive member |

49 Claim 15 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

15.43 | said rib is located between said fingers |

15.44 | and each longitudinal side of the rib is engageable with a respective one of said fingers |

50 Claim 16 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

16.45 | wherein a direct connection exists between said driven member and said [blind] cylinder |

16.46 | said direct connection being such as to cause said driven member and said [blind] cylinder to rotate in unison |

16.47 | and said spring fingers engage directly with both said drive and driven members when the drive member is rotated relative to the fixed shaft |

51 Claim 17 adds to the claims 1 to 12 the features that:

17.48 | said clutch means includes at least one helical spring surrounding said fixed shaft in a substantially coaxial relationship |

17.49 | each end of said helical spring including a laterally outwardly extending finger forming at least part of a drive connection between said drive and driven members |

52 Claim 18 adds to the preceding claims (except claim 14) the feature that:

18.50 | said at least one helical spring includes at least three said helical springs arranged end to end |

53 Claim 18 is not alleged to be infringed.

54 Claim 19 adds to the preceding claims (except claim 14) the feature that:

19.51 | said at least one helical spring constitutes the clutch means in said mechanism influencing rotation of said [blind] cylinder |

55 Claim 20 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

20.52 | said clutch means is the sole clutch means in said mechanism influencing rotation of said [blind] cylinder |

56 Claim 21 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

21.53 | said drive and driven members together with said clutch means constitute the entire assembly of parts through which manually induced drive is transmitted to said [blind] cylinder |

57 Claim 22 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

22.54 | said drive member is of unitary construction |

58 Claim 23 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

23.55 | said driven member is of unitary construction |

59 Claim 24 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

24.56 | said biasing means [spring assist] includes an elongated cylindrical spring |

24.57 | one end of said cylindrical spring being connected to said [blind] cylinder so as to be held against relative rotation |

24.58 | and the other end of said cylindrical spring being connected to said fixed shaft so as to be held against rotation relative thereto |

60 Claim 25 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

25.59 | interconnecting means provides a connection between said biasing means [spring assist] and said fixed shaft |

25.60 | opposite ends of said interconnecting means being connected to said biasing means [spring assist] and said fixed shaft respectively |

25.61 | and the connection at each said end being such as to prevent relative rotation |

61 Claim 26 adds to the preceding claims the features that:

26.62 | said interconnecting means includes a connecting member to provide a direct connection between said cylindrical spring and said fixed shaft |

26.63 | one end of the connecting member is capable of receiving and holding said other end of said cylindrical spring against rotation |

26.64 | and the other end of the connecting member extends past one end of the fixed shaft |

62 Claim 27 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

27.65 | said connecting member is of unitary construction |

63 Claim 28 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

28.66 | said connecting member is snap engaged with said fixed shaft |

64 Claim 28 is not alleged to be infringed.

65 Claim 29 adds to the preceding claims the feature that:

29.67 | said connecting member is releasably connected to said fixed shaft |

66 As noted, claim 30 is an omnibus claim to the invention as described in the Specification with reference to the accompanying drawings.

INFRINGEMENT

67 The Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’) does not provide a general definition of infringement. Rather, section 13 confers on the patentee the exclusive right to exploit the invention claimed in the Patent and to authorise others to exploit the invention.

68 The Dictionary in Sch 1 of the Act provides that:

“exploit” , in relation to an invention, includes:

(a) where the invention is a product--make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things; or

(b) where the invention is a method or process--use the method or process or do any act mentioned in paragraph (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

69 This definition of “exploit” is inclusive, and not exhaustive.

70 Damorgold have not alleged that JAI sells the whole product as claimed in its assembled form. However, Damorgold contend that, having regard to the design and nature of JAI’s products and the instructions and directions on its website, JAI has infringed each of the claims of the Patent (except claims 18 and 28):

(a) by reason of s 117 of the Act;

(b) as a joint tortfeasor at common law by directing or procuring JAI’s customers and ultimate consumers to infringe; and

(c) by authorising its customers and the ultimate consumers to exploit the Patent without the consent of Damorgold.

71 I will turn very briefly to the principles to apply relating to each of these grounds. They do not seem to be in contention between the parties. I do not consider that any of the principles to be applied have been altered by any pronouncements by the High Court in the recent case of Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 304 ALR 1; (2013) 103 IPR 217, a case decided after the reservation of my decision in this proceeding.

Section 117

72 Section 117 of the Act provides:

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

(a) if the product is capable of only one reasonable use, having regard to its nature or design--that use; or

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product--any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; or

(c) in any case--the use of the product in accordance with any instructions for the use of the product, or any inducement to use the product, given to the person by the supplier or contained in an advertisement published by or with the authority of the supplier.

73 In the present proceeding, JAI admitted it offered for sale, sold and supplied the JAI spring assists. It is also clear from its website that it offered for sale, sold and supplied all the other components necessary for a spring assist roller blind system.

74 In addition, as I have indicated, JAI admitted:

(a) the JAI spring assists were capable of only one reasonable use – namely use in combination with side controls and blind cylinders to form a mechanism for controlling the extension and retraction of a blind; and

(b) customers who purchased the JAI spring assists were and were likely to use them in combination with side controls and blind cylinders to make a mechanism for controlling the extension and retraction of a blind.

75 Prior to the trial, JAI provided to Damorgold samples of JAI’s products for a 38mm spring assisted roller blind system being:

(a) SA38L, a left handed spring assist;

(b) R210, a 38mm blind cylinder;

(c) R01 G38, a 38mm side control (drive mechanism) and idler; and

(d) R01 BK38, mounting brackets.

76 The samples supplied appeared to Mr Aspros to correspond to the corresponding parts depicted in JAI’s roller blinds catalogue.

77 According to Mr Aspros, these components were:

the components required to make up a working spring assist roller blind system, although other components are also required for a complete system, namely a blind and also a chain for the winding unit.

There is only one way for the components … to be used together.”

78 Each expert examined the samples.

79 Mr Hunter concluded that the roller blind system embodied all the integers of each of the claims in the Patent apart from claims 18 and 28. Dr Field concluded that the resulting product embodied all the integers of each of the claims in the Patent apart from claims 18, 23, 27 and 28. I note that claim 30 is also said by JAI not to infringe.

80 On the basis of the admissions of JAI and the nature and design of the JAI spring assists, the alternative requirements of each of s 117(2)(a)(b) and (c) are satisfied.

81 Therefore, on this basis, and if the Court were to accept the evidence of Mr Hunter and if the Patent is valid, JAI’s supply of JAI spring assists would infringe the Patent (apart from claims 18 and 28).

Joint tortfeasors at common law

82 The principles of joint tortfeasorship were discussed by the Full Court in Ramset Fasterners (Aust) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd (1999) 164 ALR 239; (1999) 44 IPR 481 (Burchett, Sackville and Lehane JJ).

83 In Ramset 164 ALR 239, the Court said at 258, 259 [41]:

These authorities show that liability for infringement may be established, in some circumstances, against a defendant who has not supplied a whole combination (in the case of a combination patent) or performed the relevant operation (in the case of a method patent). The necessary circumstances have been variously described: the defendant may “have made himself a party to the act of infringement”; or participated in it; or procured it; or persuaded another to infringe; or joined in a common design to do acts which in truth infringe. All these go beyond mere facilitation. They involve the taking of some step designed to produce the infringement, although further action by another or others is also required. Where a vendor sets out to make a profit by the supply of that which is patented, but omitting some link the customer can easily furnish, particularly if the customer is actually told how to furnish it and how to use the product in accordance with the patent, the court may find the vendor has “made himself a party to the [ultimate] act of infringement”. He has indeed procured it.

84 In Ramset 164 ALR 239, Ramset supplied face-lift anchors and ring clutches which were used by its customers in accordance with the patented method for a quick release hoisting attachment for tilt-up concrete panels. Ramset also provided customers and potential customers with instructions through a brochure demonstrating that infringing use. The Full Court held that the supply of the equipment with instructions demonstrating use in an infringing manner led to the conclusion that Ramset had procured the resulting infringements.

85 JAI advertised and promoted its JAI spring assists from its website as part of a range of products for making roller blind mechanisms. Those products included side controls (including drive mechanisms and idlers), and blind cylinders, as well as the other components necessary for a roller blind system, including a spring assisted system.

86 JAI’s spring assists were designed so that they would have only one reasonable use: to be assembled with other components to make an infringing mechanism. On its website, JAI also provided directions, recommendations and instructions to install the larger size roller blind systems with a spring assist.

87 In these circumstances, if the evidence of Mr Hunter is accepted and if the Patent is valid, JAI would also be liable as a joint tortfeasor by directing or procuring the use of JAI spring assists in infringing roller blind systems.

Authorisation

88 In the context of considering infringement and the authorising of third parties, ‘authorise’ has the same meaning as in copyright law: see Bristol-Myers Squibb Co v F H Faulding & Co Ltd (2000) 97 FCR 524 at 559 [97]. Therefore, to authorise includes granting or purporting to grant the right to do acts which exploit the patent: see Falcon v Famous Players Film Co [1926] 2 KB 474 per Atkin LJ affirmed in Australia by Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd (2012) 248 CLR 42, at 84-5, [126] – [127] (Gummow and Hayne JJ) and at 61, [45] – [46] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ).

89 In supplying its customers, and through them ultimate consumers, with spring assists which can only reasonably be used to make roller blind mechanisms which infringe the Patent, JAI granted, or purported to grant, its customers and ultimate consumers the right to make, and use, spring assisted roller blind mechanisms in infringement of the Patent (apart from claims 18 and 28).

90 In addition, through its roller blind specifications, JAI instructed its customers and ultimate consumers to use the JAI spring assists in that way.

91 Therefore, again if the evidence of Mr Hunter is accepted and if the Patent is valid, JAI would have infringed rights of Damorgold in the Patent by authorising infringing conduct.

INVALIDITY

92 The main contest in this proceeding related to invalidity, putting aside the omnibus claim, and the question of the infringement of claims 23 and 27. I will deal with each of these claims separately after considering invalidity.

93 In considering this main contest, the parties were not in any disagreement as the nature of the invention claimed, the principles of construction or the appropriate description of the skilled addressee.

94 I need not address the nature of the invention or the principles of construction. As to the skilled addressee, the field of the invention is the installation, manufacture and design of roller blinds and roller blind components. The skilled addressee is a person involved in the installation, manufacture and design of roller blinds and their components. Both Mr Hunter and Dr Field were witnesses who could assist the Court on construction of the Patent. Further, I would regard each as an appropriate skilled addressee.

95 I then turn to the grounds of invalidity raised by JAI.

96 JAI alleges that the Patent is invalid on effectively two grounds:

(a) the Patent is not novel;

(b) the Patent is not a manner of manufacture.

97 It was also submitted by JAI that Mr Fortunato was not the inventor. The arguments in support of this submission were effectively covered by the two grounds of invalidity mentioned above.

Novelty

98 As the complete application was filed on 25 August 2000, the Act in the form unamended by the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth) applies to determine the novelty of the patent.

99 For present purposes, s 7 of the Act in the relevant form provided:

7. (1) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of any one of the following kinds of information, each of which must be considered separately:

(a) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

(b) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art in the patent area would treat them as a single source of that information;

(c) ….

100 The term “prior art information” used in both s 7(1) and 7(3) was defined in the Dictionary in Sch 1 of the Act by reference to the “prior art base”:

“prior art base” means:

(a) in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step:

(i) information in a document, being a document publicly available anywhere in the patent area; and

(ii) information made publicly available through doing an act anywhere in the patent area; and

(iii) where the invention is the subject of a standard patent or an application for a standard patent - information in a document publicly available outside the patent area; and

(b) in relation to deciding whether an invention is or is not novel:

(i) information of a kind mentioned in paragraph (a); and

(ii) information contained in a published specification filed in respect of a complete application where:

(A) if the information is, or were to be, the subject of a claim of the specification, the claim has, or would have, a priority date earlier than that of the claim under consideration; and

(B) the specification was published on or after the priority date of the claim under consideration; and

(C) the information was contained in the specification on its filing date.

[Note: For the meaning of document see section 2B of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.]

101 It is sufficient for present purposes to treat the “patent area” as meaning Australia.

102 For the purposes of “novelty”, therefore, the prior art against which the novelty of the claimed invention is to be assessed includes any information made publicly available in a document anywhere in the world. In the case of information disclosed by doing an act, however, the act must have been done publicly in Australia.

103 The terms of s 7(1) require the prior art information to be in a single document or related documents or from doing a single act or related acts. They do not permit information in a document to be combined with information arising from doing an act, or vice versa: see the approach taken by Bennett J in Zetco Pty Ltd v Austworld Commodities Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 848 at [129].

104 The invention (as claimed in a particular claim) is taken to be novel unless it is shown to lack novelty in light of the relevant prior art.

105 The comparison required is often described as the “reverse infringement” test. That test requires that the prior art information must disclose all the essential integers of the claimed invention. Thus, in Meyers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd (1977) 137 CLR 228 at 235, Aickin J explained:

The basic test for anticipation or want of novelty is the same as that for infringement and generally one can properly ask oneself whether the alleged anticipation would, if the patent were valid, constitute an infringement ….

106 The classic test of the standard of disclosure required for a prior document to anticipate an alleged invention is that of Lord Westbury LC in Hill v Evans (1862) 4 De GF & J 288 at 300-302; 45 ER 1195 at 1199-1200; reproduced in 1A IPR 1 at 6-7:

The question then is, what must be the nature of the antecedent statement? I apprehend that the principle is correctly thus expressed: the antecedent statement must be such that a person of ordinary knowledge of the subject would at once perceive, understand, and be able practically to apply the discovery without the necessity of making further experiments and gaining further information before the invention can be made useful. If something remains to be ascertained which is necessary for the useful application of the discovery, that affords sufficient room for another valid patent. By the words of the statute of James, it is necessary for the validity of a patent that the invention should not have been known or used at the time. These words are held to mean ``not publicly known or publicly used’’. What amounts to public knowledge or public user is still to be ascertained. One of the means of imparting knowledge to the public is the publication of a book, or the recording of a specification of a patent. If, therefore, in disproving that allegation which is involved in every patent, that the invention was not previously known, appeal be made to an antecedently published book or specification, the question is, what is the nature and extent of the information thus acquired which is necessary to disprove the novelty of the subsequent patent? There is not, I think, any other general answer that can be given to this question than this: that the information as to the alleged invention given by the prior publication must, for the purposes of practical utility, be equal to that given by the subsequent patent. The invention must be shewn to have been before made known. Whatever, therefore, is essential to the invention must be read out of the prior publication. If specific details are necessary for the practical working and real utility of the alleged invention, they must be found substantially in the prior publication.

Apparent generality, or a proposition not true to its full extent, will not prejudice a subsequent statement which is limited and accurate, and gives a specific rule of practical application.

The reason is manifest, because much further information, and therefore much further discovery, are required before the real truth can be extricated and embodied in a form to serve the use of mankind. It is the difference between the ore and the refined and pure metal which is extracted from it.

Again, it is not, in my opinion, true in these cases to say, that knowledge, and the means of obtaining knowledge, are the same. There is a great difference between them. To carry me to the place at which I wish to arrive is very different from merely putting me on the road that leads to it. There may be a latent truth in the words of a former writer, not known even to the writer himself; and it would be unreasonable to say that there is no merit in discovering and unfolding it to the world.

Upon principle, therefore, I conclude that the prior knowledge of an invention to avoid a patent must be knowledge equal to that required to be given by a specification, namely, such knowledge as will enable the public to perceive the very discovery, and to carry the invention into practical use.

107 The alleged prior art information must make publicly available “each and every one of the essential integers” of each claim: see Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 91 ALR 513 at 527 – 528, 531 - 532 per Gummow J, with Jenkinson J agreeing; and Zetco [2011] FCA 848 at [93] (per Bennett J).

108 As Bennett J then went on to say in Zetco [2011] FCA 848 at [93]:

Such a disclosure may be explicit or, in certain circumstances, may amount to a sufficient disclosure of each integer to a skilled worker even though not explicit (H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151; Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 91 ALR 513). This may occur where, for example, the prior art information is a publication which does not specify an integer but the skilled reader would understand that integer to be present in the subject matter described. The same applies to what is disclosed to the person of skill in the art by a prior product. If the prior art does not expressly specify each and every essential integer of the claimed invention, the evidence must clearly establish that, to the skilled reader, each and every essential integer is included in that prior art. If the prior art relied on is an object rather than a publication, that object must incorporate all of the essential integers of the claim, as would an infringement (Meyers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd (1977) 137 CLR 228 at 235). Otherwise, it is necessary to establish that the skilled addressee would add the missing information to the combination as a matter of course and without the application of inventive ingenuity; he or she must, in effect, “see” the missing integer in the prior art object (Lundbeck at [181] and [183] per Bennett J, Middleton J agreeing). The term “enabling disclosure” may also be apposite to disclosure to the skilled addressee of an asserted prior use; the issue is whether what the skilled addressee observes on inspection is sufficient to enable him or her to comprehend the complete invention (Insta Image Pty Ltd v KD Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 78 IPR 20). A person of skill in the art examining a prior art valve may know of a component that equates to a missing integer, or the missing integer may be part of common general knowledge. However, this does not necessarily mean that the prior art discloses that missing integer and that anticipation has occurred. Such a submission misunderstands the test for anticipation. It is a matter of the disclosure of the prior art information.

109 Information will be made “publicly available” if it is accessible to a member of the public in circumstances where that person would be free in law and equity to make such use of it as they saw fit: see eg Insta Image Pty Ltd v K D Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 78 IPR 20 at [124] per Lindgren, Bennett and Logan JJ.

110 In the case of anticipation by doing an act in public, one can usually ask “what information was given” to a person skilled in the art by the use in question: see Insta Image 78 IPR 20 at [125]-[126], [151]. The question posed under the Act is whether the claimed invention has been disclosed by conduct: see Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155; 65 IPR 86 at [139] (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) and Insta Image 78 IPR 20 at [122].

111 In Insta Image 78 IPR 20 the Full Court at [124] distilled the following principles for determining whether information was publicly available before the priority date:

(a) The information must have been made available to at least one member of the public who, in that capacity, was free, in law and equity, to make use of it: PLG Research Ltd v Ardon International Ltd [1993] FSR 197 at 226 per Aldous J cited in Jupiters 65 IPR 86 at [141].

(b) It is immaterial whether or not the invention has become known to many people or a few people (Sunbeam Corporation v Morphy-Richards (Aust) Pty Ltd (1961) 180 CLR 98 at 111; 1B IPR 625 at 633 per Windeyer J). As long as it was made available to persons as members of the public, the number of those persons is not relevant. Availability to one or two people as members of the public is sufficient in the absence of any associated obligation of confidentiality: Formento Industrial SA & Biro Swan Ltd v Mentmore Manufacturing Co Ltd [1956] RPC 87 at 99-100; Re Bristol-Myers Co’s Application [1969] RPC 146 at 155 per Parker LJ.

(c) The question is not whether access to an invented product was actually availed of but whether the product was made available to the public without restraint at law or in equity: Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd (2006) 154 FCR 31; 68 IPR 511; [2006] FCAFC 91 at [98]-[103].

112 In Insta Image 78 IPR 20 the alleged prior use was of a collapsible canopy framework used at public events such as motocross races and jet ski races. The Full Court found (at [151]) that this constituted a prior public use (omitting case references):

The public was not denied access, and there was a means for the public to inspect the original. There was nothing to prevent a member of the public from going to its location at the back of the pits, and examining it sufficiently to understand its construction and its component features. There is nothing in the evidence to suggest that examination would not have revealed all of the integers of the claimed invention including the mounts and pins described in the Patent specification. The information gleaned from such an inspection would, for the purposes of practical utility, be equal to that given in the patent. An inspection would enable a person skilled in the art to put the claimed invention into practice. (citations omitted)

113 In addition, in Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited v Sarb Management Group Pty Ltd (trading as Database Consultants Australia) (No 2) (2013) 101 IPR 496, Yates J looked at the public demonstration of the product claimed to be anticipating the invention, citing Lux Traffic Controls Limited v Pike Signals Limited [1993] RPC 107 at 134, and commenting as follows:

There is a difference between circumstances where the public have an article in their possession to handle, measure and test and where they can only look at it. What is made available to the public will often differ in those circumstances. In the latter case it could be nothing material; whereas in the former the public would have had the opportunity of a complete examination.

114 In Lux Traffic Controls [1993] RPC 107 Aldous J (at 134-135) had to consider whether there was a prior public disclosure during the course of trials conducted in Somerset of a prototype traffic light controller:

...Thus what is made available to the public by a machine, such as a light control system, is that which the skilled man would, if asked to describe its construction and operation, write down having carried out an appropriate test or examination. To invalidate the patent, the description that such a man would write down must be a clear and unambiguous description of the invention claimed.

In the present case, a light system with a prototype controller was on a number of occasions made available to contractors over five months. Those contractors were free in law and equity to examine it. When doing so, they could observe the lights, test the detectors and observe when a detection had been made. They could not, upon my conclusion as to fact, have seen the control panel which had a light showing that a demand had been recorded.

If a skilled man had taken the time to test the way the lights worked, using the prototype controller, he would have seen that the system used standard lights and standard detectors....

I conclude that such an examination would be sufficient to disclose the invention of claim 1. Once the prototype controller was made available to the contractors, then all the details of the invention were also made available to them. I conclude that claim 1 lacked novelty.

115 All cases must be determined upon the evidence. For instance, in Insta Image 78 IPR 20 and Longworth v Emerton (1951) 83 CLR 539, the courts could find as a fact that the public could readily perceive and understand the invention from what was displayed. In Aspirating IP Limited v Vision Systems (2010) 88 IPR 52 at [265]-[266], [276] and [287]-[288], Besanko J rejected the display of a photograph as sufficient to constitute prior use, but his Honour found that the claimed invention lacked novelty on the basis of evidence that the witness, Dr Cole, had thoroughly explained to potential customers a way in which the device depicted in the photograph worked.

Prior Art or Conduct relied upon

116 JAI relied as conduct and prior art on:

(a) the showing of and making available for sale in Australia the RolaShades product;

(b) the publication of the 1996 catalogue and RolaShades Drawing; and

(c) the Toso Patent (European Patent Specification 0 180 832).

The RolaShades product

117 JAI led evidence from Mr Horner and Ms Payne that, in or about November 1996 (before the priority date), its predecessor, JAI Pty Ltd imported into Australia a handful of RolaShades mechanisms, assembled some of them into blinds and offered them for sale by showing the blinds and the mechanism itself to some customers in its showrooms, at the customers’ places and by inclusion in a catalogue. In addition, JAI led evidence from Mr Jackson that he had seen invoices of sales by RolaShades to some persons.

118 In particular, evidence was led from Mr Horner and Ms Payne as follows:

(a) in about November 1996, Mr Horner organised the purchase from RolaShades of around six to ten RolaShades products;

(b) The RolaShades products were delivered to JAI Pty Ltd’s showroom in Atarmon, New South Wales;

(c) Mr Horner assembled several RolaShades products into complete blinds, by inserting them into blind tubes. One of these blinds was mounted using brackets and fixed onto a shelving unit. The blind was then weighted with sand bags (to simulate a blind with heavy fabric) and used as a test or demonstration unit. The blind cylinder and the brackets were obtained from RolaShades;

(d) JAI Pty Ltd staff (including Ms Payne) were encouraged to test the durability of the RolaShades product by operating the mounted blind mechanism whenever they went past;

(e) Other mounted blinds including RolaShades products were displayed and available for sale at the showroom;

(f) During late 1996 or early 1997, when demonstrating the RolaShades product to potential customers, Mr Horner showed it both in the form of a mounted blind (in a tube) and separately (referring to exhibit R6). As Mr Horner explained:

... I would take them to my customers’ places and show them…

(Q) Show what – what you show the customers is how it works? …

(A) How it works and they like to see the component as well so I would had – I would have a blind on a board in my car and one of these separate again and say, here you are, this is what is in this blind and we would put it on their rack and we would pull it up and down and show them.

(g) The RolaShades Product was included in the 1996 catalogue;

(h) Copies of the 1996 catalogue were mailed to approximately 200 of potential Australian customers, handed to customers who visited the office, sent to agents or given out by sales representatives.

119 Damorgold do not accept the evidence led by JAI on these matters. It also submitted that even if the evidence led be accepted, it did not satisfy the requirement that information sufficient to destroy novelty has been made publicly available.

120 Damorgold submitted that the Court could not confidently find that JAI Pty Ltd did in fact display or offer for sale in Australia the RolaShades product before the priority date, or included any depiction of the product in the 1996 Catalogue.

121 Damorgold reminded the Court that where prior use of this kind is alleged, the courts require strict proof. In Nicaro 91 ALR 513, 524 – 525 Gummow J said:

It is essential that an allegation of prior public use should be strictly proved. Evidence which is uncorroborated is undoubtedly suspect and should be scrutinized with particular care. The court must be satisfied that the proof is sufficient in the circumstances, having regard to the gravity of the allegation.

122 The reasons for this are the well-recognised frailty of memory, especially of events in the distant past and the potential for accurate recollection to be contaminated by subsequent events: see Commonwealth Industrial Gases Ltd v MWA Holdings Pty Ltd (1970) 180 CLR 160 at 165 - 166 (Menzies J).

123 Damorgold pointed, quite correctly, to a number of problems with the quality of the evidence adduced by JAI. The first problem was that there was no contemporaneous documentation to support JAI’s claims. Neither Mr Horner nor JAI has produced:

(a) any sales invoice or receipt for the alleged purchase from RolaShades;

(b) any customs or other shipping documentation; or

(c) any copy of the alleged 1996 JAI catalogue in which it is claimed that the spring assist was included.

124 The second problem was that JAI had not brought forward any independent witness who could verify any of these events. No witness had been put forward:

(a) from RolaShades;

(b) from any of the 10 customers to whom Mr Horner said he displayed the assembled blind and the spring assist; or

(c) from any of the 200 or so customers to whom the 1996 catalogue was said to be shown.

125 Neither Mr Kensey nor Mr Wood, two actors in the events Mr Horner claims took place, were called by JAI.

126 Nevertheless, Mr Horner did produce a spring assist mechanism. However, it had no brand on it or any other markings which enable its source to be identified or for it to be dated with any accuracy.

127 In addition to the above failure to produce other evidence, I also accept that a number of valid complaints can be made of the evidence in fact called, and these were outlined by Damorgold.

128 First, it was submitted that Mr Horner had a direct interest in the outcome of this proceeding, as he was one of the two directors of JAI. His family trust company owned 50% of the shares in JAI. The sale of JAI’s infringing product was a part in JAI’s business of selling roller blinds which he was motivated to protect.

129 Secondly, it was submitted that Mr Horner was attempting to give evidence of events which occurred a very long time ago – approximately 15 years before his affidavit was sworn. His attempts to date the events were submitted to be plainly unreliable, as evidenced by certain inconsistencies:

(a) As at 7 March 2011, the Particulars of Invalidity 1(b) claimed the sale was “about 1994”;

(b) As at 8 March 2011, the Amended Defence 7 claimed “late 1996”;

(c) As at 23 May 2011, the Amended Particulars of Invalidity 1(b) claimed “purchased about 1994”, “promoted late 1994”, “published in a catalogue March 1995” and “displayed late 1994”;

(d) As at 20 September 2011, Mr Horner’s affidavit [10] claimed it was “purchased October 1996”; [12] it was “displayed late 1996 early 1997” and [13] included in a “catalogue 1996”;

(e) This changed in oral evidence based on his passport to returning to Australia at the end of November 1996.

130 Damorgold also attacked Mr Horner’s evidence regarding introducing a new product into its range. It submitted that the evidence that JAI Pty Ltd would go to the lengths of introducing a new product into its range, including bringing out a new catalogue, only to drop it within a few months, was highly implausible, especially as the proffered explanation based on exchange rate movements seemed to be an insignificant factor.

131 Further, the evidence that Mr Horner imported not only the RolaShades product (exhibit R6), but also that product together with all the component parts necessary to assemble it into a working blind, was introduced at a late stage (only in cross-examination), and was not accepted by his own office manager, Ms Payne.

132 I have carefully considered Mr Horner’s evidence keeping in mind the cautionary considerations raised by previous authorities. My first impression of his giving of evidence, and my subsequent review of his evidence, remain constant.

133 I accept that Mr Horner did not have a clear recollection of exactly when events occurred. To a certain extent, he reconstructed what could or might have happened from an article in a magazine about an Austrade trip, his expired passport and extrapolation from a trip to Stuttgart. All this was done to assist him to put a date upon the events he described.

134 I have had the advantage of seeing Mr Horner give his evidence at the trial. He appreciated readily that he could not remember the exact dates. He was obviously using documentation to assist, perhaps even reconstruct, the timing of the events. However, as to the events themselves, he independently recalled these happening. Mindful not to readily accept oral evidence (unsupported by documentation) as to prior public use, there is no principle of law to deny acceptance of such evidence if the court, upon hearing the witness, is convinced of its essential accuracy as to the decisive factual matters in contention.

135 Mr Horner seemed to me to be a reliable witness. He was unsure of exact dates, but was ‘aided’ by certain matters referred to above to assist his recollection. This is not unusual and was to be expected. The one thing he was certain about was the identity of the spring assist mechanism he produced, and that it was purchased and displayed prior to 1999.

136 As to the other criticisms made of Mr Horner, I make these comments.

137 The reason for dropping off the new product from the range within a few months of its introduction, was not because of the exchange rate as alluded to by Mr Horner. The real reason seemed to arise from disputation between the partners as to the introduction of the range in the first place. However, I do not consider this detracts from the other evidence Mr Horner gave as to the identity of the spring assist mechanism and the date of it display.

138 Secondly, the fact that Mr Horner introduced late into evidence that all the component parts were also imported does not detract from my view that Mr Horner was clear and definite about the two important matters – the identity of the spring assist mechanism he displayed and offered for sale in Australia, and that this occurred well before 1999.

139 Thirdly, because the relevant events occurred many years ago, I would not expect ‘independent’ witnesses in the category mentioned by Damorgold, would be either available or able to provide any useful evidence in this proceeding.

140 Therefore, despite the criticisms of Mr Horner, I accept his evidence on the two important matters of the identifying of the spring assist mechanism and the date of its display and offering for sale in Australia.

141 That is not the end of the evidence supporting these important matters. I turn to Ms Payne’s evidence. She was adamant throughout her cross-examination about the accuracy of her recollection of the spring assist mechanism and the relevant date of importation, supporting the essential facts deposed to by Mr Horner. In my view, she was a credible witness and as it transpired during cross-examination, had no desire or motive to help out her long term former employer. Again, my view of her credibility has remained constant from my first impression of her whilst giving evidence, and my subsequent review of her evidence.

142 Damorgold also made some criticisms of the evidence of Ms Payne.

143 Damorgold submitted that Ms Payne was attempting to give evidence about events 17 years in her past. She had been retired since 2000. She had not had any occasion to recall those events until asked to provide an affidavit in this proceeding in late 2012. In order to identify the product she was simply given the product and asked whether or not it was the one she had seen 17 years previously. She conceded that the product had no markings on it, as to source or date. Even if she is accepted as identifying it accurately, it was submitted that she could not prove that exhibit R6 was the actual sample she saw in 1996. Although, Ms Payne was adamant about the accuracy of her recollection, it was submitted that:

(a) Ms Payne was wrong about the date of Mr Horner’s visit to Singapore in 1994.

(b) She was more vague about Mr Horner’s 1996 visit to Singapore.

(c) Ms Payne had no clear recollection of how the alleged 1996 catalogue was prepared or withdrawn, and her evidence is a reconstruction about what would or might have happened.

144 However, like Mr Horner, Ms Payne was adamant about the identity of the spring assist mechanism (which she recognised as exhibit R6 for plausible reasons she advanced as to her particular recollection at the time) and the date being well before the year 1999. I would not expect Ms Payne to know the exact date, even in a range of six or so months. However, she was adamant, with cause in my view, as to the approximate time of the relevant importation and events upon which she was cross-examined.

145 Then there is further supporting evidence. Despite some of the vagueness and lack of detail, Mr Jackson’s evidence, and to a lesser extent Mr Ang’s evidence, partly corroborates Mr Horner’s evidence that he purchased the RolaShades product in 1996 in the manner he described. Mr Jackson’s evidence in particular at least establishes that a product like the RolaShades product was available for purchase overseas, in or around 1996 or 1997, as Mr Horner contended in his evidence.

146 Therefore, I accept the evidence of Mr Horner and Ms Payne, as detailed above.

147 I find that JAI Pty Ltd did have possession of a few RolaShades products brought into Australia before the priority date as detailed in the evidence of Mr Horner, which included the sample described by Mr Horner and Ms Payne, which is exhibit R6. I am satisfied, whilst no 1996 Catalogue is in evidence, that RolaShades product was shown in the 1996 Catalogue as it was depicted in the 1998 Catalogue (which is in evidence).

148 This is a situation, distinguished from other cases, where the original product in the form of exhibit R6, is available at the time of the hearing, and the evidence is not limited to photos of the product or witnesses’ recollection of the product. Further, the product, as Mr Hunter said, involves simple and straight forward technology.

149 Nevertheless, there is no evidence that any RolaShades product was actually sold by JAI Pty Ltd, nor that any samples were actually provided to anyone to retain. Mr Horner had samples which he showed to particular customers with a view to an eventual sale of the RolaShades product. However, at the time the RolaShades product was demonstrated to customers, it was available for sale, albeit for a short period of time.

150 The real issue in this proceeding is whether based upon the circumstances in which it occurred, the showing of the RolaShades product in Australia to some potential customers with a view to making such available to sale, amounted to making publicly available the RolaShades product.

151 The RolaShades product was mounted in blinds on display at the showroom in Atarmon, but was also shown at customers’ places of business. As Mr Horner said, the part he showed customers to explain how the product worked was similar to (if not) exhibit R6. Whilst it is not possible to ascertain all the internal componentry of the JAI spring assist without pulling it apart to understand its internal workings, this could be readily done without any damage to any part of the mechanisms. Re-assembly was easy. Whilst undoubtedly Mr Horner did not want any potential customer to “reverse engineer” the mechanism, he was offering or making available for sale the RolaShades product. I accept that he did not want any of the samples to be taken by the customers. In fact, all the samples were retained by Mr Horner and none was left with the customers. This was not to be unexpected, as Mr Horner needed the samples to show other potential customers. Nevertheless, a customer would have a general idea of the mechanism employed in the RolaShades product from observing the RolaShades product itself, specifically exhibit R6.

152 Further, and significantly, in view of Mr Horner’s commercial interest in selling the blinds, if asked by a potential customer, I find that he would have readily pulled apart the RolaShades product to demonstrate exactly how it worked. This could have been readily achieved, and re-assembly was simple. Mr Hunter dismantled Exhibit R6 with no difficulty.

153 It is important to appreciate that the potential customers of Mr Horner were entities who made blinds, and who had an interest in the working of the new product, described by Mr Horner as “a very unique product back in the day”. The RolaShades product was offered for sale in the 1996 catalogue, and if sold, would not have been subject to any restrictions on its use. Mr Horner, when showing his potential customers the samples, would appreciate that upon sale the product was capable of reverse engineering.

154 In my view, the potential customers of Mr Horner would have been free to dis-assemble exhibit R6, and would have been interested in looking at its mechanical workings. The acts of Mr Horner in displaying the RolaShades product to various customers, with a view to sale, was making the RolaShades product publicly available. There was a means for any customer to inspect the RolaShades product. The customers had an incentive to inspect and Mr Horner had an incentive to allow the customers to do so. Each customer had the opportunity to handle, view, and test the RolaShades product. An examination of the component features would have been easy, and would have revealed all the relevant integers of the claimed invention. Such an examination would have readily enabled a person skilled in the art to put the claimed invention into practice.

155 It is clear from the expert evidence of both Mr Hunter and Dr Field that the workings of the RolaShades product (including its use in a blind control mechanism) can be discerned from an inspection once dis-assembled. The person skilled in the art so inspecting the RolaShades product would observe sufficient to enable them to comprehend the complete invention. No further experimentation was required.

156 Further, the person skilled in the art would readily comprehend that the RolaShades product would be combined with the other well known roller blind components, including a chain winder mechanism and a blind cylinder.

157 It does not matter that only a few, or perhaps only one, potential customer was approached and had the opportunity to examine the RolaShades product. It does not matter that the RolaShades product was not actually dis-assembled. Each potential customer, in my view, had the opportunity of a complete examination of the internal componentry of the RolaShades product. There was no restriction placed upon any potential customer as to what he or she would do in making use of the information so obtained from an examination of the internal componentry.

158 It is of no importance that no actual sale took place. The circumstances described above constitute sufficient conduct of making the RolaShades product publicly available in Australia. That conduct of displaying and offering for sale the RolaShades product (in the circumstances described) made available the necessary information to find anticipation.

159 Mr Hunter’s evidence was that he could identify in the RolaShades product all the integers of claims 1-22, 24-26, 29 and 30.

160 Dr Field’s evidence was that the RolaShades Product had each of the integers of each of claims 1-17, 19-22, 24-26, 29 and 30.

161 Thus, on the reverse infringement test, conduct of showing the RolaShades product in the circumstances I have found to have occurred would constitute an infringement of at least claims 1-17, 19-22, 24-26, 29 and 30 of the Patent.

The 1996 Catalogue

162 I consider this aspect of the contention of JAI can be readily disposed of on the basis that there is insufficient disclosure in the 1996 Catalogue.

163 No example of the 1996 Catalogue was produced in evidence. Mr Horner and Ms Payne gave evidence of its contents by reference to the 1998 Catalogue that was in evidence. I have accepted that evidence. According to Mr Horner, the RolaShades product was shown with an “exploded” view similar to that of the “Spring Motor” product shown on page 4 of the 1998 Catalogue.

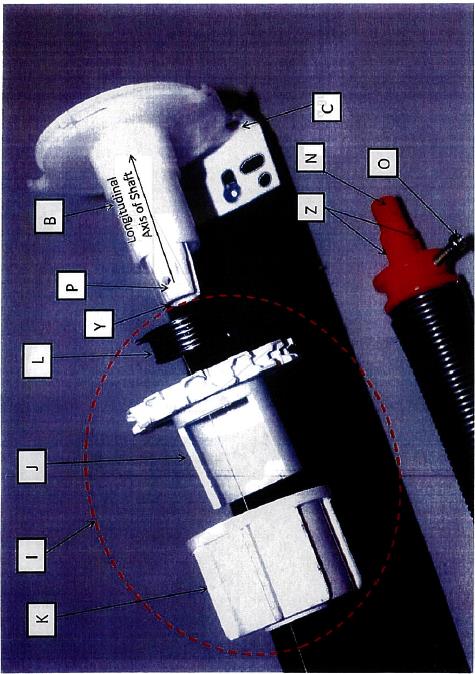

164 That representation is:

165 However, in my view there was no disclosure of any of the internal components such as depicted in figure 1 of the Patent.

166 Such evidence as there is, does not support a conclusion that all of the integers claimed in, for example, claim 1, can be seen in such an exploded view or would be understood by the person skilled in the art.

167 Therefore, there has not been sufficient disclosure by the 1996 Catalogue.

The RolaShades Drawing

168 The position is similar in connection with the RolaShades Drawing. There are four versions of RolaShades drawings before the Court, a version included in Dr Field’s written evidence, a version introduced by Mr Ang, and two versions in exhibit R-10.

169 JAI focuses upon the version referred to by Dr Field, upon which the experts specifically opined.

170 Whatever version is taken, and even if I could find that the relevant drawing is prior art information for the purposes of the novelty assessment, none of the drawings discloses sufficient information to satisfy the standard laid down in Hill v Evans and subsequent cases.

171 For example, Mr Hunter’s evidence was that it was not possible to tell what type of clutch was used or how spring assistance was utilised. In response, Dr Field agreed:

Mr. Hunter has re-stated my opinion that the RolaShades drawing alone does not explain the type of clutch used in the RolaShades product …. I agree that the mechanism by which the spring would be tensioned is not apparent from the drawing ….

However, Mr Hunter has raised the suggestion (para 11 in his affidavit) that I may have been comparing the RolaShades drawing in isolation, to the Damorgold patent. This was not my intention, and I agree with him that the RolaShades drawing does not provide sufficient information to provide more than a superficial comparison.

172 It is apparent, just by this one example, that the skilled addressee could not “at once perceive and understand and be able practically to apply the discovery without the necessity of making further experiments” and that no version of the RolaShades Drawing itself provides “clear and unmistakable directions” to carry out the claimed invention.

The Toso Patent

173 Damorgold accepted that the Toso Patent forms part of the prior art base for the purposes of the novelty assessment. Damorgold submitted, however, that it does not disclose all the essential integers of the claimed invention.

174 The Toso Patent is entitled ‘A screen locking device’. The invention claimed is for a clutch device, the essence of which is a reversible key (marked 18, depicted in figure 2 of the Toso Patent).

175 The device of the Toso Patent is intended to operate in two very different situations. In one, a large braking force is desired for a heavy blind. In this situation, the blind can be raised or lowered only by operating the chain pulley. In the other situation, however, a reduced braking force is desired so that the blind can be lowered by hand.

176 The Toso Patent identifies the problem which arose in seeking to use a ‘known device’ for both purposes: it was necessary to change the coil spring fitted to the clutch mechanism which ‘is not easy’ once the spring has been fitted.

177 The Toso Patent (at column 2:60) then describes two different configurations of blind; one for use in the first situation, the second for use in the second situation:

In the roll blind having a heavy screen without an auxiliary spring-motor, the key is set one way in which the projection is within the both crossed ends of the coil spring to give the device a large braking force and surely prevent the rotation of the screen-roll by the weight of the screen. In the case of the roll blind with an auxiliary spring-motor, the key is set the other way in which the projection is out of the both crossed ends to give the device a small braking force. The small braking force not only prevents the device from making a noise when the screen stops but also allows the screen to be directly pulled down by hand, ….

178 In the first configuration, the reversible key is inserted so that the clutch mechanism provides the desired large braking force similar to the way the clutch mechanism functions in the Patent. However, in this configuration, there is no spring motor or spring assistance.

179 In contrast, in the second ‘fundamentally different’ configuration, the key is reversed so that a lower braking force results. If that were the only change to the first configuration, however, the weight of the blind itself would lead to the blind unrolling. To counteract this, therefore, ‘an auxiliary spring motor’ must also be fitted to provide a balance to the weight of the blind.

180 In this second configuration, it is possible to pull down on the blind itself to lower the blind. In the first configuration, however, pulling down on the blind only increases the braking force applied by the clutch so that it is not possible to pull the blind down in this way.

181 Mr Hunter considered that these are the only two embodiments disclosed in the Toso Patent. He compared each of these embodiments to each of the claims. As a result, he concluded:

(a) the first embodiment (with the key engaged to create a spring clutch) does not disclose any of the claims as at the least there is no ‘biasing means’ – integers 1.8 – 1.11 and 1.21; and

(b) the second embodiment also does not disclose any of the claims at least because it does not disclose a ‘driven member’ – integers 1.14 and 1.15, 1.18 and 1.19 and 1.26.

182 Undoubtedly, the Toso Patent has many references to the reversible nature of the key:

(a) “reversibly fitted in the sleeve to set its projection either of both ways”;

(b) “when the key is set one way … when the key is set the other…”;

(c) “key is reversibly set with ease when sleeve is reversed from screen roll”;

(d) “when the projection is reversed”;

(e) “adjustment is easily performed by reversing the key fitted on the sleeve which is remove ably inserted into the screen-roll”;

(f) the key 18 is easily reversed … easily picked out of the sleeve 17 and reversibly reset in the sleeve”;

183 Mr Hunter gave evidence that ‘reversible’ meant something could be used one way and then another (eg a reversible coat) and that having changed one way, something could be changed back.

184 Mr Hunter said that changing the key over would be a relatively easy thing to do, that could be done by a blind installer.

185 Mr Hunter agreed that if the key in a blind of the second embodiment was reversed that the result would disclose all the integers of claim 1 and all the clutch integers.

186 Dr Field accepted Mr Hunter’s analysis comparing those two embodiments to the claims.

187 Dr Field also accepted that the Toso Patent described only the two embodiments identified by Mr Hunter.

188 Dr Field, however, considered that the Toso Patent disclosed the invention claimed in the Patent because he analysed the Toso Patent as though it also includes the other combinations.

189 Dr Field read the reference in column 1:31 to ‘the device’ as a reference to ‘the known device’ referred to earlier in line 15. From this Dr Field concluded that the use of ‘an auxiliary spring-motor’ in combination with the spring clutch of the ‘known device’ was also known, making reference to the 088 patent (which is in evidence).

190 The 088 patent is an earlier patent to the Toso Patent for a screen-operating device for use in a roller blind.

191 It is true that the 088 patent was for a simple spring clutch which is similar (although not identical) to the clutch shown in the Patent. However, the 088 patent does not refer to a “spring assist” or an “auxiliary spring-motor”.

192 Further, whilst Mr Hunter was aware of the use of spring motors in the different mechanism of Holland blinds, Mr Hunter said:

I am not aware of the prior use of an auxiliary spring motor to balance the weight of a screen, or in conjunction with a chain clutch. I do not agree with Dr Field that the Toso Patent teaches or even suggests, the use of what Dr Field calls “normal” clutch coil springs on heavy chain operated blinds with the option of a counter balance spring.

193 Mr Hunter was of the view that there were two different embodiments, one for each of the two different purposes.