FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier [2013] FCA 1426

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier [2013] FCA 1426

CORRIGENDUM

1. The original medium neutral citation “Apotex Pty Ltd v Servier Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1426” on the cover page was incorrect and has been replaced with “Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier [2013] FCA 1426”.

2. In paragraph [50] “Prof Evans is” has been replaced with “Until he was recently appointed Provost, Prof Evans was”.

3. In paragraphs [49], [60], [75], [107], [183], and [213] “Bryn” has been replaced with “Byrn” wherever occurring.

4. In paragraph [87] “bytylamine” has been replaced with “butylamine”.

5. In paragraph [109] “burylamine” has been replaced with “butylamine”.

6. “Aequous” has been replaced with “aqueous” wherever occurring.

7. In paragraph [146] “which had a molecular weight of 44.15 mmol” has been replaced with “(44.15 mmol)” and “which had a molecular weight of 41.94 mmol” has been replaced with “(41.94 mmol)”.

8. In paragraph [148] “paramaters” has been replaced with “parameters”.

9. In paragraph [150] “The salt break” in the third sentence has been replaced with “The method”.

10. In paragraph [151] “with a molecular weight of 32.56 mmol” has been replaced with “(32.56 mmol)” and “with the same molecular weight” has been replaced with “(32.56 mmol)”.

11. In paragraphs [181] and [182] “Illonois” has been replaced with “Illinois”.

12. In paragraph [181] “Fireball” has been replaced with “Firebelt”.

13. In paragraph [186] “vaguaries” has been replaced with “vagaries”.

14. In paragraph [240] “hygroscopity” has been replaced with “hygroscopicity”.

15. In paragraph [250] “germaine” has been replaced with “germane”.

16. In paragraph [268] “dessicant” has been replaced with “desiccant”.

17. In paragraph [289] “Coverysl” has been replaced with “Coversyl”.

|

I certify that the preceding seventeen (17) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Rares. |

Associate:

Dated: 10 April 2014

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

APOTEX PTY LTD ACN 096 916 148 Applicant | |

|

AND: |

First Respondent SERVIER LABORATORIES (AUST) PTY LTD Second Respondent |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and prepare draft orders, including as to costs, to give effect to the reasons for judgment published today and in the event that the parties are unable to agree on such orders:

(a) on or before 31 January 2014, the applicant file and serve its draft orders, any further evidence and written submissions limited to 10 pages;

(b) on or before 10 February 2014, the respondents file and serve their draft orders, any further evidence and written submissions limited to 10 pages.

2. The proceedings stand over to 14 February 2014 for directions or the making of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

NSD 51 of 2012 |

|

BETWEEN: |

APOTEX PTY LTD ACN 096 916 148 Applicant |

|

AND: |

LES LABORATOIRES SERVIER First Respondent SERVIER LABORATORIES (AUST) PTY LTD Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

RARES J |

|

DATE: |

24 DECEMBER 2013 |

|

PLACE: |

SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 These proceedings concern the validity of Australian patent AU 2003200700 (the patent) which has the priority date of 18 April 2002. The patent makes claims for an invention of a new salt of the compound perindopril, called perindopril arginine. Perindopril, itself, had been patented much earlier. Perindopril is used to lower blood pressure in patients with high blood pressure (or hypertension).

2 Les Laboratoires Servier is the registered proprietor of the patent and its wholly owned subsidiary, Servier Laboratoires (Aust) Pty Ltd, is the exclusive licensee (collectively Servier). There is no relevant need to distinguish between those two companies in these reasons.

3 Servier had an earlier patent for the salt known as perindopril erbumine (an abbreviation for perindopril tert-butylamine). Between 1992 and 2006 Servier marketed that compound in Australia and internationally in a tablet form known under the brand name Coversyl. Commercially, Coversyl has been a very successful drug product for Servier. When the earlier patent expired, Servier began to market its new tablets containing perindopril arginine under the Coversyl brand name. At the same time Apotex Pty Ltd began marketing a generic version of perindopril erbumine.

4 Apotex brought these proceedings to challenge the validity of the patent because it wishes to enter the market with a generic version of perindopril arginine. It claimed that the patent should be revoked on six grounds. Broadly, those grounds are that, based on s 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) (as in force at 18 April 2002):

the invention was not a patentable invention on the bases that :

(1) it was not novel when compared to the prior art base, because one or both of two earlier patents had claimed the invention of a method for synthesis of perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts (s 7(1), 138(3)(b)) (the novelty issue); or

(2) it lacked an inventive step because it would have been obvious to a person skilled in the art, in light of the existing common general knowledge to try making a salt of perindopril with arginine (ss 7(2), 138(3)(b)) (the inventive step issue);

the claims in the patent were not fairly based on the matter described in the specification (ss 40(3), 138(3)(f)) (the fair basis issue);

the patent did not describe the best method known to Servier of performing the invention (ss 40(2)(a), 138(3)(f)) (the best method issue);

the patent had been obtained by false suggestions or misrepresentations (s 138(3)(d)) (the false suggestion issues).

5 I will describe first, some of the relevant pharmaceutical concepts, secondly, the legislative scheme, thirdly, the patent, and fourthly, each issue in turn together with its factual matrix and the parties’ arguments on that issue. I think that this will aid understanding of the separate factual and legal questions pertinent to each issue.

6 Perindopril is an amino acid that is commonly prescribed to lower a patient’s blood pressure. It acts as an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. It is usually administered in small dosage tablets taken once each day. The tablets comprise of a compound consisting of a salt form of perindopril, which is its active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), and excipients. The salt may dissociate into its ionic components when it is added to an aqueous medium. Such a reaction can occur in the human stomach. The salt is converted in the patient’s body by hydrolysis into the biologically active compound, perindoprilat. The hydrolysis results from the perindopril molecule reacting with water to produce the perindoprilat and ethanol.

7 A salt is a compound that contains ionic components, one of which, called a cation, is positively charged, and another, called an anion, which is negatively charged. The cation lacks one or more electrons while the anion has one or more extra electrons. The cation is attracted to the anion and an electrostatic interaction occurs between them so that they form an ionic bond in which the charges are in equilibrium. A salt of an organic molecule consists of the ion of the organic molecule and a counter-ion from the reagent, relevantly here, an acid or base with which it reacts. Typically, the acid is defined as a proton donor (being positively charged) and the base as a proton acceptor (being negatively charged).

8 When a pharmaceutical salt is formed, a proton, being a hydrogen ion, transfers from the acid to the base. This results in an ionic pair consisting of both a cation and an anion. The general salt forming equilibrium reaction can be summarised as follows, where B is the base, HA is the acid or proton donor, BH+ is the cation, A– is the anion and the salt is comprised of both the cation and anion:

B + HA ⇌ BH+ + A–

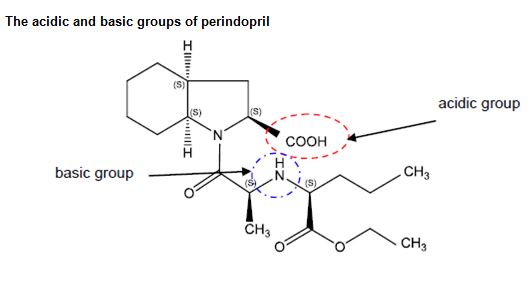

9 Perindopril is known as a zwitterion because it can form a salt with a counter-ion that is either an acid or a base. That is because perindopril contains both an acidic (carboxylic acid) group that can lose a proton to form a salt with a base and a basic (amine) group that can gain a proton to form salts with an acid. Perindopril may also be crystallised in a non-salt form if both its acidic and basic groups interact with each other. The acidic and basic groups of perindopril are shown on the figure below:

10 The effectiveness of a drug can be affected by its physicochemical properties. Those physicochemical properties can be altered and, possibly, optimised by the creation of one or more salt forms of the drug substance. Typically, the solid state properties of salts of a drug substance will differ from those of the substance itself: i.e. when it is in its free acid or free base form. Those properties can ultimately affect the biological and pharmacokinetic profile of the drug substance.

11 Salts can be used to improve the properties of a drug substance in a number of ways, including improving solubility, tailoring and adapting the drug to the therapeutic use and pharmaceutical dosage form, modifying, if need be, the drug’s pharmacokinetic properties (i.e. the body’s absorption, distribution, metabolisation and excretion of the drugs), improving or preserving the drug’s chemical and/or physical stability, and facilitating or enhancing its industrial processing.

12 An API is formulated with excipients into a tablet or composition. The excipients are inactive compounds that usually contribute to the drug delivery profile, or way and time in which the drug substance will arrive at the place in the patient’s body where it is effective. Thus, excipients can cause the drug substance to be released immediately, gradually at or during a particular time period after the patient takes the tablet. In addition, the formulation of the tablet and the process by which it is made can affect the shelf-life of the drug product.

13 Tablets are made by mixing their ingredients as intimately and evenly as possible and then compressing these in a die in a tablet press. The evenness of the mixture of the API with the excipients is a critical part of the process to produce tablets. The three main methods of tablet production are:

• wet granulation: the ingredients are mixed with water or another solvent, granulated, dried and compressed into tables;

• dry granulation: the granulation occurs without addition of water or another solvent;

• direct compression: the ingredients are mixed and directly compressed into tablets without a granulation step.

14 Thus the creation of a salt of a drug substance can be an important means to bring it to market as a medically and commercially useful product.

15 The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is the Australian regulator with the responsibility for medicines and the administration of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth). The TGA publishes and applies regulatory guidelines for drugs or prescription medicines that are based, to a large extent, on international standards. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) is the international body responsible for establishing a unified global regulatory rÉgime. It recommends harmonised guidelines that can be adopted by local regulators. The European Medicines Agency (EMEA) is the European regulator and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the regulator in the United States of America. In general, the TGA does not directly adopt ICH guidelines. Rather, the TGA commonly adopts the guidelines published by the EMEA that, in turn, adopt those of the ICH.

16 The TGA, or other regulator, assesses a shelf-life and appropriate storage conditions for a pharmaceutical substance when it has been developed to the point that it is ready for commercial sale. This is necessary because the API or the tablet or other composition in which the API is administered to the patient may be susceptible to degradation or deterioration over time or in particular temperatures or other storage conditions. That is, the pharmaceutical product, in the form it is to be sold, may or may not be stable.

17 There are two aspects of the stability of both drug substance and a drug product that the regulator, and no doubt a manufacturer, must address, namely its chemical and physical stability. Chemical stability concerns whether the chemical content of the drug substance itself remains constant or degrades. Physical stability concerns changes to the physical form of the product (e.g. whether the form is, or varies to, polymorphic, solvate or hydrate) or its appearance and to its handling or storage. Ideally, the drug substance and product should remain chemically and physically unchanged for many years under typical ambient storage conditions.

18 Tests to evaluate which of the number of counter-ions are appropriate for further testing as a suitable salification (salt making) agent are called salt-screens. One element considered in salt-screening is the stability of the salt produced. Stability of a salt is important in considering its effect on the shelf-life of any developed product utilising the salt. This consideration is important in assessing the commercial viability of any product that utilises the salt. In general, the longer the shelf-life of a drug product the greater the manufacturer’s flexibility to deal with unused or unsold but older or dated stock. The ICH Stability Guideline defines shelf-life of a pharmaceutical product as:

“The time period during which a drug product is expected to remain within the approved shelf-life specification, provided that it is stored under the conditions defined on the container label.”

19 An expiry, or use-by date, is the usual means of stating the shelf-life of a commercial pharmaceutical product. However, a retest date, as opposed to an expiry date, is sometimes given for an API. That is because the API will usually remain under the control of the drug manufacturer which will need to retest the API at, or after, the given date in order to see if it remains well within specifications and so is suitable to use in manufacturing a drug product. The ICH Stability Guideline defines “retest period” as:

“The period of time during which the drug substance [API] is expected to remain within its specification and, therefore, can be used in the manufacture of a given drug product, provided that the drug substance has been stored under the defined conditions.”

20 Drug manufacturers must undertake extensive stability testing of each of an API and a drug product to satisfy a regulator of the appropriateness of its particular given shelf-life. Ordinarily, the regulator will only approve a shelf-life for a drug product on the basis of extensive testing of the stability performance of its dosage form, as packaged, in particular controlled conditions, including conditions of identified temperature and humidity. This is replicated in Australia in the TGA Stability Guideline that requires testing of the exact formulation and final packaging intended for the marketing of the drug product in this country.

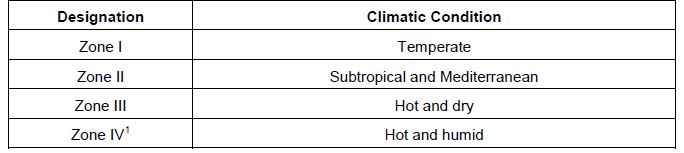

21 From 1996 until October 2005, the ICH recognised the following four climatic zones in the table below for its requirements for pharmaceutical products:

22 Australia is in zones III and IV while Europe is in zones I and II. Therapeutic goods Order No 69: General requirements for labels for medicines provides for the standard permitted storage temperatures for pharmaceutical products as:

“(a) Store below -18°C (Deep freeze);

(b) Store below -5°C (Freeze);

(c) Store below 8°C (Refrigerate);

(d) Store at 2°C to 8°C (Refrigerate. Do not freeze.);

(e) Store below 25°C; and

(f) Store below 30°C.”

23 While the TGA can approve a different storage temperature for a pharmaceutical product, in general 30°C was, relevantly, the maximum storage temperature for pharmaceutical products marketed in Australia.

24 Packaging can play a significant role in the approval of a shelf-life for a pharmaceutical product. Packaging has two principal purposes in the pharmaceutical industry, namely presentational and functional. Packaging enables, first, the product to be presented to and identifiable by users (such as pharmacists, doctors and patients) and to convey product information, including as to storage and shelf-life, evidence of no prior tampering or use and features to make the product visually or tactilely attractive. Secondly, packaging can serve a number of functions, some of which can overlap. These functions include providing a convenient and reliable way of dispensing a consistent dose, child proofing, a means of maximising shelf-life by protecting the product from humidity and or air, as well as protecting it during transport, warehousing or other storage.

25 The sponsor (or proponent) of a pharmaceutical product, such as each of the parties to these proceedings, must provide the regulator, as part of the marketing approval process, with details of the packaging in which the product is proposed to be marketed. Such products are typically marketed in bottles or blister packs. Since before 2002, bottles used for pharmaceutical products have been made of glass or a plastic, such as high density polyethylene (HDPE). A desiccant will often be placed in a bottle if the drug product can absorb water from the atmosphere or the air in the bottle.

26 Blister packs can consist of (1) a sheet of polymer formed into a series of wells into which individual tablets are placed and (2) a sheet of aluminium foil, the edges of the abutting side of which has a coating of heat-seal lacquer, placed over the open wells containing the tablets. Then, usually for less than a second, the two sheets are pressed together and heated to between 140°C and 160°C to enable the lacquer to bond. This type of packaging is known as aluminium/PVC or PVC/Alu. However, if the application of heat may affect the drug product, it is possible to use lacquer that can adhere at a lower temperature or a more expensive pressure sensitive adhesive.

27 A second form of blister packaging, known as Alu/Alu can be made using aluminium laminate as the welled base and aluminium lidding foil. These are sealed using a heat seal lacquer in the same way as aluminium/PVC blisters are.

28 A third form of blister packing, known as tropicalised packaging, consists of a aluminium/PVC blister overwrapped with an aluminium foil bag that contains a desiccant. Servier used tropicalised packaging for its perindopril erbumine Coversyl products that it sold in Australia at all relevant times.

29 The parties agreed that the relevant provisions of the Patents Act were those as in force when Servier filed the provisional specification for the patent in France on 18 April 2002 (which did not mention hydrates at all) and when the complete specification was filed here on 27 February 2003. The Act remained unamended between 1 April 2002 and 4 July 2003. I have used that version of the Act in these reasons.

30 Any person could apply for an order revoking the patent (s 138(1)). Critically, s 138(3) provided:

“(3) After hearing the application, the court may, by order, revoke the patent, either wholly or so far as it relates to a claim, on one or more of the following grounds, but on no other ground:

…

(b) that the invention is not a patentable invention;

(d) that the patent was obtained by fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation;

…

(f) that the specification does not comply with subsection 40(2) or (3).”

31 Apotex raised two issues under s 18(1)(b) in support of the ground in s 138(3)(b), namely novelty and inventive step. Those issues were governed by ss 18(1)(b) and 7(2), which for present purposes provided:

“18 Patentable inventions

Patentable inventions for the purposes of a standard patent

(1) Subject to subsection (2), an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of a standard patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

…

(b) when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim:

(i) is novel; and

(ii) involves an inventive step;

7 Novelty and inventive step

Novelty

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of any one of the following kinds of information, each of which must be considered separately:

(a) prior art information … made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

…

Inventive step

(2) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim …”

The Dictionary in Sch 1 of the Act relevantly provided:

“prior art base means:

(a) in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step or an innovative step:

(i) information in a document that is publicly available, whether in or out of the patent area; and

(ii) information made publicly available through doing an act, whether in or out of the patent area.”

32 Apotex also raised two issues under s 40(2)(a) and (3), namely whether the specification described any, or the best, method known to the patentee of performing the invention and whether the claims in relation to hydrates of perindopril arginine were fairly based on the matter described in the specification. Relevantly, s 40 provided:

“40 Specifications

(1) A provisional specification must describe the invention.

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention;

…

(3) The claim or claims must be clear and succinct and fairly based on the matter described in the specification.”

33 The Commissioner of Patents had to accept a patent request and a complete specification relating to an application for a standard patent (such as the patent in issue) if she were satisfied that the invention, so far as claimed, satisfied the criteria in s 18(1)(b) and she considered that there was no other lawful, unresolved ground of objection to the request and specification (s 49(1)). Any person could oppose the grant, relevantly, on the grounds that the invention was not a patentable invention or the specification filed in respect of the complete application did not comply with s 40(2) or (3) (s 59).

The patent

34 The specification in the patent began by stating that the invention related to a new salt of perindopril and pharmaceutical compositions containing it. The specification stated that perindopril had previously been described in a European patent (EP 0 049 658) that had mentioned, as was usual, that compounds of the invention might be presented in the form of addition salts with a pharmaceutically acceptable, mineral or organic, base or acid. It stated that the compounds described in the European patent were in a non-salt form and “primarily, when addition salts with a pharmaceutically acceptable base or acid are mentioned by way of example, the sodium salt or the maleate are given” (p 1 lines 12-14). The specification continued:

“In the development of that product, however, it has proved very difficult to find a pharmaceutically acceptable salt having not only good bioavailability but also adequate stability to be suitable for the preparation and storage of pharmaceutical compositions.” (p 1 lines 15-17)

35 The specification noted that the non-salt form had been studied, as well as the maleate and the sodium salt, and that in the course of temperature and humidity stability studies these had been found not to be suitable because the sodium salt was immediately converted into an oil on contact with the atmosphere and the non-salt form and maleate degraded rapidly under higher temperature conditions. The specification continued:

“The tert-butylamine salt was thus alone in exhibiting the best stability compared to the other forms studied. However, in view of the intrinsic fragility of perindopril, the tert-butylamine salt has not been capable of providing a complete solution to the problems of the product’s stability to heat and humidity. Indeed, for marketing, tablets of perindopril tert-butylamine salt must, in certain countries, be protected with additional packaging measures. Moreover, even for temperate-climate countries, that instability has made it impossible to obtain a shelf-life of more than 2 years for the tablets. Finally, for marketing of the tablets, they have to be marked “to be stored at a temperature less than or equal to 30 degrees”.

These constraints are, of course, onerous especially in terms of organisation and cost, and it has appeared especially useful to try to develop a new perindopril salt in order to reduce the constraints due to the tert-butylamine salt.” (p 1 line 23-p 2 line 9)

36 The specification then said that numerous salts had been studied and that those customarily used in the pharmaceutical sector had proved to be unusable and continued:

“On the other hand, and in surprising manner, it has been found that the arginine salt of perindopril, besides being new, has entirely unexpected advantages over all the other salts studied and, more especially, over the tert-butylamine salt of perindopril.” (p 2 lines 12-14)

37 The specification then said that the present invention related to the arginine salt, its hydrates and also to the pharmaceutical compositions comprising it. It identified the preferential form of the salt as being natural arginine (L-arginine) and said that the pharmaceutical compositions according to the invention comprised the arginine salt together with one or more, non-toxic, pharmaceutically acceptable and appropriate excipients. The specification then identified a variety of possible pharmaceutical compositions and various administration and dosage methods. It stated that the pharmaceutical compositions according to the invention would preferably be immediate release tablets and that the useful dosage varied according to the age and weight of the patient, the nature and severity of the disorder and to the administration route (p 2 line 15, p 3 line 5).

38 The specification identified the amount of arginine salt contained in the compositions according to the invention, including the preferred quantities between 1 to 10 mg and that those compositions were of use in the treatment of hypertension and heart failure. It continued:

“The basic characteristics of this salt are very great stability to heat and to humidity compared to the tert-butylamine salt.

Long-term stability studies carried out under very precise temperature and humidity conditions have yielded the results indicated in the Table hereinbelow.

In that study, perindopril was assayed by inverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography using, as eluant, an aqueous phase (comprising sodium heptane-sulphonate, and the pH of which is 2) and acetonitrile (67/33). Detection of the product was carried out by UV (215 nm).

The study was carried out using immediate-release tablets containing either 2.4 mg of the arginine salt of perindopril or 2.0 mg of the tert-butylamine salt of perindopril (each of the two tablets containing 1.7 mg of perindopril). The tablets were assayed 6 months after the start of storage of the tablets at different temperatures and different relative humidities (% R.H.).

The arginine salt used in this study is the L-arginine salt. It has been prepared according to a classical method of salification of organic chemistry.

|

Conditions 6 months |

tert-Butylamine salt of perindopril Percentage remaining(%) |

Arginine salt of perindopril Percentage remaining (%) |

|

25°C 60% R.H. |

101.0 |

99.5 |

|

30 °C 60% R.H. |

94.4 |

98.1 |

|

40°C 75% R.H. |

67.2 |

98.6 |

The results presented in the Table above show extremely clearly the very great stability of the arginine salt compared to the tert-butylamine salt. Indeed, after 6 months, practically no degradation of the arginine salt has taken place whereas the tert-butylamine salt exhibits a degradation rate of approximately 33%.” (p 3 line 9-p 4 line 5)

39 The specification then asserted that the results were entirely unexpected and could not have been deduced from or suggested by the teaching of the literature on the product and concluded by stating:

“The results allow us to consider less onerous constraints with respect to the packaging of the pharmaceutical compositions and also to obtain a shelf-life of at least three years for our pharmaceutical compositions.” (p 4 lines 8-10)

40 The patent asserted 11 claims defining the invention but, as noted above, only the following five are relevant:

“1. The arginine salt of perindopril and its hydrates.

2. Pharmaceutical composition comprising, as active ingredient, the arginine salt of perindopril and its hydrates, in combination with one or more pharmaceutically acceptable excipients.

3. Pharmaceutical composition according to claim 2, characterised in that it is presented in the form of an immediate-release tablet.

4. Pharmaceutical composition according to either claim 2 or claim 3, characterised in that it contains from 0.2 to 10 mg of the arginine salt of perindopril.

…

6. A method of treatment or prophylaxis of hypertension and heart failure comprising administering to a patient in need of such treatment or prophylaxis an efficacious amount of the arginine salt of perindopril and its hydrates of claim 1, or a pharmaceutical composition as claimed in any one of claims 2 to 4.”

41 Claims 8-11 referred to descriptions of the invention in “the Examples”, but there were no examples set out in the patent and so those claims could not be sustainable.

Some general background

42 In late 2006 Servier ceased to supply perindopril erbumine tablets under the Coversyl brand name and began selling perindopril arginine tablets under it instead. The perindopril arginine tablets are made by wet granulation and then packaged in HDPE bottles with a desiccant. They have a TGA approved shelf-life of three years when marked “store below 30°C”.

43 Also in late 2006, Apotex began selling its perindopril erbumine tablets. Those are made by direct compression, marketed in Alu/Alu (or cold form foil) packaging and initially had a TGA approved shelf-life of two years when marked “store below 25°C”. Pharmacists can substitute Apotex’ perindopril erbumine tablets for patients who present prescriptions for Servier’s perindopril arginine tablets under the National Health Act 1953 (Cth). In 2007, the TGA approved a longer shelf-life of three years for Apotex’ perindopril erbumine tablets when marked “store below 25°C”.

44 In January 2012, Apotex informed Servier that it had applied to the TGA for registration of generic perindopril arginine products on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme once they were approved by the TGA. Apotex commenced these proceedings on 16 January 2012. Servier obtained an interlocutory injunction in March 2012 restraining Apotex from selling perindopril arginine effectively until final judgment. Apotex did not oppose that course. Apotex accepts that if claims 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 of the patent are valid, it would infringe them. Servier does not seek relief on the basis of any apprehended infringement of claims 5 and 7 on the basis that Apotex does not allege that those two claims are independently invalid. The parties did not present argument about the detail of how the individual claims may be infringed, no doubt because of Apotex’ concession that if its invalidity arguments fail, unless further restrained, it will infringe the patent by going to market with its new generic.

45 The parties called six experts in chemistry with expertise in pharmaceutical matters. There was no issue that each of these experts was appropriately qualified. I found their evidence of considerable assistance. I will very briefly summarise their qualifications which, however, are much more extensive and impressive than is necessary to record in these reasons.

46 Apotex relied on Dr Peter Spargo, Dr Desmond Williams and Associate Professor Michael Perkins. Dr Spargo is currently a consultant. He had worked in the field of chemistry research and development in the pharmaceutical industry seeking to develop new chemical entity therapeutic agents since he began his career working for Pfizer Ltd in the United Kingdom in 1988. He had particular experience and expertise in solid form (including salt and polymorph) selection.

47 Dr Williams is currently the program director, pharmaceutical science in the School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences and supported researcher in the Sansom Institute for Health Research at the University of South Australia. He is also a registered pharmacist and chartered chemist. His experience included pharmaceutics (i.e. the formulation of drug substances, such as APIs, into drug products suitable for, and adapted to, effective delivery to the intended site within the human body). He had worked for a number of large pharmaceutical companies and had considerable experience in dealing with regulators, including the TGA, and has been a member of the pharmaceutical subcommittee of the TGA’s Advisory Committee on Prescription Medicines since 2005.

48 Prof Perkins is currently an Associate Professor in the School of Chemical and Physical Sciences at Flinders University, South Australia. His experience is broadly in organic chemistry and natural product chemistry, with particular expertise in synthetic organic chemistry, including the discovery, action and metabolism of drugs.

49 Servier relied on Professor Stephen Byrn, Professor Alan Evans and Dr Angelo Morella. Prof Byrn has had an academic career at Purdue University, Indiana in the United States of America since 1972, becoming a Professor of Medicinal Chemistry in 1981 and being head of the Department of Industrial and Physical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy and Pharmacal Sciences there between 1994 and 2009. He is an accomplished scientific author, having written a text book and many peer-reviewed journal articles. He co-founded a teaching program for sustainable medicines in Africa that seeks to address the lack of accessibility to high quality medicines there. In 1991, he co-founded SSCI Inc (an acronym for “Solid State Chemical Information”) and was its study director till 2006 when it was taken over by Aptuit Inc. He has since then been a consultant to SSCI. From 1993, SSCI has been both a professional development provider of educational services in the pharmaceutical industry and a commercial provider of contract research including formulation development, salt and polymorph screening on potential drug candidates and existing drugs. By 2006, SSCI employed over 100 persons. Prof Byrn had conducted, supervised or controlled over 100 salt-screens and over 200 polymorph screens as at April 2002.

50 Until he was recently appointed Provost, Prof Evans was Professor of Pharmaceutics at the University of South Australia and currently its Pro-Vice Chancellor and Vice President, Division of Health Sciences. He was head of that university’s School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences from 2004 to 2009. His primary research specialty is pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics. He also worked as a retail pharmacist for seven years to 1989. He has been involved in consulting for the pharmaceutical industry, in particular in comparative bioavailability studies between different salts in the development of pharmaceutical compounds.

51 Dr Morella is currently a drug delivery and pharmaceutical consultant. He had worked from 1985 to 2012 with FH Faulding and Company Limited and with Mayne Pharma International, following its takeover of Faulding, in various roles relating to drug development, his final position there being General Manager R & D. He is a named inventor on over 100 patents. He had responsibilities at Faulding and Mayne that required him to be aware, in general terms, of formulation and packaging requirements for countries, including those in ICH climate zones III and IV, to which his employers exported drug products.

52 The experts prepared two joint reports and gave their oral evidence concurrently. The joint reports were very helpful in distilling a number of matters that were either agreed by all relevant experts or on which they disagreed. The concurrent evidence lasted for four and a half days and allowed each expert to articulate the substantive points on which he was in agreement or at issue with any of his colleagues. This greatly assisted in identifying the real issues.

53 At the trial Apotex relied on the disclosure of perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts in two Australian patents published before 18 April 2002, that being the agreed priority date of the claims under s 43(2)(a). Those were:

Australian patent 200124847 entitled “Method for synthesis of perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts” that had a journal publication date of 1 November 2001 (the synthesis patent);

Australian patent 2001276418 entitled “A crystalline form of perindopril tert-butylamine salt” that had a journal publication date of 14 February 2002 (the crystalline form patent).

54 The synthesis patent claimed a process for the industrial synthesis of formulae of “perindopril and pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof”. Its specification noted that perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts “and more especially the tert-butylamine salt thereof, have valuable pharmacological properties”. That specification also referred the capacity for one formula to be “converted, if desired, into a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, such as the tert-butylamine salt”.

55 The crystalline form patent claimed a new Α crystalline form of the compound formula for the tert-butylamine salt and also a process for its preparation as well as compositions containing it. The specification again recited that “Perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts, and more especially its tert-butylamine salt, have valuable pharmacological properties”. It went on to say that perindopril, “its preparation and its use in therapeutics have been described in European Patent specification EP 0 049 658”.

56 Critically, neither the synthesis nor the crystalline form patents mentioned any specific salt of perindopril other than the tert-butylamine salt, except in the generalised unspecific references to “pharmaceutically acceptable salts”. That is, nothing in those two patents taught the skilled addressee, or the lay reader, what salts of perindopril, other than perindopril erbumine, were pharmaceutically acceptable or anything about them. They did not suggest that any such salt had been made, far less identify what it might be. Nothing in either of those patents referred to arginine at all, let alone, its potential to create a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of perindopril. On the other hand, both patents left open and unconfined their disclosures that perindopril’s pharmaceutically acceptable salts (whatever they might be in addition to the tert-butylamine salt) had pharmacological uses.

57 The parties agreed that the common general knowledge in Australia prior to 18 April 2002, included the existence of perindopril erbumine and Coversyl, and that perindopril erbumine was the API in Coversyl, each of perindopril (and Coversyl containing it) was used as an ACE inhibitor, being an active ingredient in pharmaceuticals for the treatment of heart failure and hypertension.

58 In addition, Apotex contended that a skilled addressee would have been aware, as part of the common general knowledge, of a reference source for counter-ions that could be used to create a pharmaceutically acceptable salt. That source was a paper by Stephen M Berge, Lyle D Bighley and Donald C Monkhouse entitled “Pharmaceutical Salts” published in the January 1977 edition of the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences (the Berge paper).

59 The Berge paper surveyed literature over the preceding 25 years and identified from that exercise potentially useful counter-ions with which to make pharmaceutical salts. It then divided the results into three tables which were subdivided into anions (acids) and cations (bases) and listed the percentage of the instances of use of each substance. Tables I and II of the Berge paper listed all counter-ions used to make salts of organic compounds that were commercially marketed up to 1974. Table I comprised all counter-ions that had been used in products approved by the FDA, while Table II comprised counter-ions that had been used in products marketed in other countries, but had not been approved by the FDA. The paper explained that its authors had considered only salts of organic compounds in Tables I and II because most drugs were organic substances. Table III comprised other counter-ions that had been “reported to be potentially useful [scil: to form] pharmaceutical salts”. Arginine was listed, with lysine, in Table III. Both of those substances were amino acids that occur naturally in the human DNA. The Berge paper listed well over 100 counter-ions that could provide a relatively discrete source of reference for persons skilled in the art of creating salts if they were aware of that publication.

60 Both Dr Spargo, an Englishman, and Prof Byrn, an American, were aware of the Berge paper. Of the Australian witnesses, Dr Evans was aware of the information concerning FDA approved commercially marketed salts in Table I of the Berge paper, but not its source. His awareness came from his familiarity with the pharmacy textbook: Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy (19th ed). Dr Morella was also aware of the Berge paper but, like Prof Byrn, both in their work, did not use counter-ions that were not on Table I because those substances had not created salts that the FDA had approved. Prof Perkins did not recall being aware of the Berge paper prior to 2002 and I am not satisfied that he was aware of it. Dr Williams was aware of the Berge paper from his doctoral studies in Kansas in 1979. The experts agreed in their first joint report that it is not possible to predict whether a salt-screen would make a crystalline salt and what properties any such solid would have.

61 Apotex argued that the prior art before the priority date of the patent in suit consisted of, first, the disclosures in the synthesis and crystalline form patents, that there were other, albeit unidentified pharmaceutically acceptable salts of perindopril in addition to the tert-butylamine salt and, secondly, the common general knowledge that arginine was a counter-ion listed in the Berge paper as a substance that could be used to make a pharmaceutically acceptable salt form. Apotex submitted that the Berge paper disclosed a finite range of candidate counter-ions that the person skilled in the art would be aware of as part of common general knowledge in Australia before the priority date. Thus, it contended, such a person having read either or both of the disclosures about perindopril and its pharmaceutically acceptable salts in the synthesis and or crystalline form patents, would understand that matter to refer to the limited number of counter-ions that can be used to form salts listed in the Berge paper as including arginine. For that reason, so the argument ran, the two earlier patents anticipated all pharmaceutically acceptable salts including the arginine salt in the patent in suit.

62 Apotex contended that if the skilled addressee initially did not read either of the two prior art patents as revealing the arginine salt as a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of perindopril, he or she would have arrived at that conclusion using the Berge paper as part of the addressee’s common general knowledge. That paper was the only item of common general knowledge on which Apotex relied in aid of its challenge based on the patent’s lack of novelty. In essence, Apotex’ argument was that the skilled addressee on reading either or both of the synthesis or crystalline form patents, and using common general knowledge derived from the Berge paper’s list of potential counter-ions, would understand that patent to contain a direction to make, at least, the arginine salt and so infringe a claim or claims in that patent.

(b) Who is the skilled addressee?

63 In my opinion, for the purposes of these proceedings, the hypothetical person skilled in the art or, the skilled addressee, was a non-inventive chemist with scientific qualifications working in a drug development context whose routine work involved the formulation and making of salts for use in pharmaceutical products.

64 It is likely that such a person would have worked in a team. Such a person would be conversant with the principles and general practicalities of salt making and salt selection as well as the methods of pharmaceutical tablet formulation and composition. The perspective of “a person skilled in the relevant art” was that of a hypothetical non-inventive worker in the field who was equipped with the common general knowledge in Australia (being the patent area) before the priority date of 18 April 2002: Lockwood Security Products Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [No 2] (2004) 235 CLR at 197 [56]. Relevantly, the evidence did not demonstrate that the common general knowledge at that date differed from the position at 27 February 2003.

(c) Consideration

65 An invention is presumed to be novel unless, relevantly here, when compared separately to each piece of prior art information made publicly available in a single document (here each of the synthesis and crystalline form patents), the comparison would demonstrate to a skilled addressee that the invention had been disclosed in that earlier information (s 7(1)(a)).

66 The skilled addressee’s consideration of the prior art for the purposes of s 7(1) can be at two levels, the first that simply takes account of what information the prior art conveyed to him or her; the second, that is aided by his or her use of what was “common general knowledge” in Australia at the relevant time (here 27 February 2003), in the sense of that expression as explained by Aickin J, with whom Barwick CJ, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ agreed in Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 292 and 295, namely (see at 292):

“The notion of common general knowledge itself involves the use of that which is known or used by those in the relevant trade. It forms the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade in considering the making of new products, or the making of improvements in old, and it must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge.” (emphasis added)

67 There is nothing in either of the synthesis or crystalline form patents beyond the words “pharmaceutically acceptable salts” that deals with the creation or use of any possible salt of perindopril, other than the tert-butylamine salt, in connection with the claims. In the first joint experts report, Prof Perkins and Drs Spargo and Williams said:

“One would have an expectation to form one or more crystalline salts, which could be subjected to further testing with regard to their suitability as pharmaceutical salts.”

68 Profs Byrn, Evans and Perkins, and Drs Morella, Spargo and Williams agreed that there was no certainty that any counter-ion would produce a salt, or, if it did, what its properties and suitability would be. They accepted, as the Berge paper itself noted, that “choosing the appropriate salt, however, can be a very difficult task, since each salt imparts unique properties to the parent compound” (emphasis added). And they all agreed that one would need to do one or more salt-screens and undertake a process of trial and error in order to ascertain what particular counter-ion or counter-ions would yield, first, a salt and secondly, one that was pharmaceutically acceptable. The experts all accepted the correctness of the Berge paper’s statement that:

“Furthermore, even after many salts of the same basic agent have been prepared, no efficient screening techniques exist to facilitate selection of the salt most likely to exhibit the desired pharmacokinetic, solubility, and formulation profiles.”

69 Each of the parties’ arguments on novelty had a logical tension. Servier contended that the two patents that Apotex asserted were anticipations of perindopril arginine did not give any instruction as to that substance’s formulation and so it was outside their claims. Apotex argued that Servier would have sued, for infringement of those two patents, anyone who created any new pharmaceutically acceptable salt, such as the arginine salt, because such a salt was within the claims in each of those patents.

70 It is necessary that the prior art (here one or both earlier patents) disclose an invention that, if performed, would necessarily infringe the patent in suit: H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151 at 194 [189] per Bennett J, with whom Middleton J agreed. Her Honour added (at 194 [189]-[190]):

“Once the very subject matter of the invention has been disclosed, the person skilled in the art is assumed to be willing to make trial and error experiments to get it to work ... where the prior publication is of the subsequently claimed invention, that is sufficient. Where the prior disclosure falls short of a complete disclosure, the question of the sufficiency of that disclosure arises. It is there that consideration must be given to the quality of a disclosure to the skilled addressee armed with common general knowledge … the Court, armed with the evidence of the skilled addressee as to terms of art and the nature and extent of the disclosure in the prior art document, must determine whether the prior disclosure is sufficient to enable the skilled addressee to perceive, understand and, where appropriate, apply the prior disclosure necessarily to obtain the invention.” (emphasis added)

71 The invention will be disclosed to a skilled addressee by the prior art provided that any trial and error experimentation needed is a standard or ordinary procedure or something that is part of common general knowledge as a practical means of performing the invention: Lundbeck 177 FCR at 190 [173]. However, if all the prior art does is to describe the earlier invention without disclosing the effective means by which it could be produced, it will not anticipate a subsequent invention: Olin Corporation v Super Cartridge Co Pty Ltd (1977) 180 CLR 236 at 261 per Stephen and Mason JJ, Barwick CJ agreeing on this point at 239. For an anticipation of a subsequent discovery, the prior art, coupled if need be with common general knowledge, must disclose to the skilled addressee “a practicable mode of producing the result which is the effect of the subsequent discovery”: Olin Corporation 180 CLR at 261. And as Bennett J observed in Lundbeck 177 FCR at 192 [181]:

“If the prior art discloses some but not all integers of a claimed patent to a product, such as a combination, there is anticipation if the skilled addressee would add the missing information as a matter of course and without the application of inventive ingenuity or undue experimentation (Nicaro [Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990)] 91 ALR [513] at 530-531).”

72 In ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v The Lubrizol Corporation Inc (2000) 106 FCR 173 at 230 [51] Lee, Heerey and Lehane JJ applied the “flag metaphor” used by Sachs, Buckley and Orr LJJ in General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485-486 to illustrate the concept of anticipation. Their Lordships said:

“To anticipate the patentee's claim the prior publication must contain clear and unmistakable directions to do what the patentee claims to have invented: Flour Oxidizing Co Ltd v Carr & Co. Ltd. (1908) 25 RPC 428 at 457, line 34, approved in BTH Co Ltd v Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Co Ltd (1928) 45 RPC 1 at 24, line 1). A signpost, however clear, upon the road to the patentee's invention will not suffice. The prior inventor must be clearly shown to have planted his flag at the precise destination before the patentee.”

73 The Full Court in Lubrizol 106 FCR at 230 [51] added that anticipation was not proved if the skilled addressee had to rummage through the prior inventor’s flag locker to find a flag there that could have been (but was not) planted.

74 I am of opinion that the synthesis and crystalline patents, when read by a skilled addressee and using common general knowledge, that included the Berge paper, did not anticipate the invention of the arginine salt claimed by the patent in suit. Those patents contained no directions whatever as to the production of any salt, other than the tert-butylamine one, in the catch-all words “pharmaceutically acceptable salts”. The Berge paper told the skilled addressee that the FDA had approved salts made from the counter-ions listed in Table I. That paper said that counter-ions listed in Table III, such as arginine, had been reported to be “potentially useful” in creating pharmaceutical salt forms. At best, if the Berge paper were common general knowledge of a skilled addressee, it gave arginine as an ambiguous signpost, obscured by its status in Table III, upon the road to the invention of the arginine salt.

75 Ordinary trial and error experimentation would have involved using counter-ions in Table I of the Berge paper for the reasons that Prof Byrn and Drs Evans and Morella gave in the first joint experts report for not trying arginine. Indeed, Dr Williams said that as “there are no obvious precedents, then arginine would not have been high on the list of options to try”. Ordinary trial and error experimentation does not extend to prolonged research, inquiry or experiment: cf TA Blanco White, Patents for Inventions (4th ed: 1974) Stevens & Sons: London) at [4-504]; see too (5th ed: 1983) at [4-504]. All the experts agreed that they would not try arginine in a first salt-screen to make a new perindopril salt. The unpredictability of successfully making a salt with any counter-ion, let alone one that is pharmaceutically acceptable, requires a person skilled in the art to engage in a selection process. Inventions are born of insights that make actual things that, beforehand, were potentially possible, albeit sometimes highly unlikely. As Prof Byrn, whose business had involved salt making, explained, if the first salt-screen or screens using counter-ions in Table I failed, and if the skilled addressee had additional time and money, he or she might go to Tables II or III in the Berge paper but would not be likely to try arginine.

76 The necessity to choose the appropriate counter-ion or ions to make a pharmaceutically acceptable salt and the absence of either any, let alone a clear, description of the arginine salt or any instructions on how to make it, satisfy me that there was no disclosure in the anodine wording of the synthesis or crystalline form patents (even if read in light of the Berge paper): Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis (2009) 82 IPR 416 at 439-440 [136]-[139] per Bennett and Middleton JJ. Here, the skilled reader of either of those patents could not predict that any particular acid or base, and especially arginine, used as a counter-ion for perindopril, would result in a pharmaceutically acceptable salt. Gyles J, as the trial judge, expressed the test graphically in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis (2008) 78 IPR 485 at 525 [91]:

“Anticipation is deadly but requires the accuracy of a sniper, not the firing of a 12 gauge shotgun.”

77 The expression “pharmaceutically acceptable salts” used in the two prior art patents lacked any substantive precision. The first joint expert report explained that it is not possible to predict with certainty what both the outcome of any salt-screen process and the properties of any particular salt produced will be. The two prior art patents did not give any hint of what, if any, pharmaceutically acceptable salts existed other than perindopril erbumine.

78 Leaving aside the tert-butylamine salt, those patents did not describe how to make any other salt that would have the characteristic of pharmaceutical acceptability or provide any examples of such a salt. They “taught” the reader nothing about any pharmaceutically acceptable salt of perindopril other than perindopril erbumine.

79 Apotex correctly argued that the prior art merely needed to disclose, not teach, the invention: Lundbeck 177 FCR at 192 [178]. However, the prior art (in light of common general knowledge) must really disclose the invention. Here, the “disclosure” was of unspecified “pharmaceutically acceptable salts of perindopril”, and the prior art gave no direction how to perform that invention. In a real sense that phrase was devoid of content in that context, even with knowledge of the Berge paper. Table III of the Berge paper merely identified arginine as “potentially useful”, as opposed to a substance that ordinary trial and error experiments would involve in salt-screens. I am not satisfied that a skilled addressee would be able to perceive, understand and apply the disclosure relied on by Apotex in either of the two earlier patents, in light of common general knowledge including the Berge paper necessarily to obtain the invention: Lundbeck 177 FCR at 194 [190]. The quality of the “disclosure” relied on by Apotex was insufficient to amount to a disclosure of the invention of perindopril arginine. The skilled addressee would have had to engage in much more than ordinary trial and error experimentation to think of, or produce, the arginine salt. He or she would not have seen any flag to try arginine as a counter-ion in the two earlier patents that Apotex relied on as anticipations and the common general knowledge.

80 In any event, I am not satisfied that the Berge paper was common general knowledge of the ordinary skilled addressee or had been generally accepted and assimilated by the class of skilled addressees in Australia as at 27 February 2003: Lockwood [No 2] 235 CLR at 197 [55]-[56] per Gummow, Hayne, Callinan, Heydon and Crennan JJ; Minnesota Mining 144 CLR at 292; Alphapharm 217 CLR at 426-427 [31]. In Lubrizol 106 FCR at 232 [57] the Full Court acted on the findings of the trial judge, Emmett J, that common general knowledge was the technical background to the hypothetical skilled worker in the relevant art. Emmett J said that it was not limited to material that might be memorised and retained in the front of that worker’s mind but included material in the field in which he or she worked that the worker “knows exists and to which he [or she] would refer as a matter of course”. Here two of the four Australian experts, Dr Evans and Prof Perkins, were unaware of the Berge paper while Dr Williams knew of it adventitiously because, while studying in Kansas, his thesis supervisor drew it to his attention. As a result of his lack of awareness, Prof Perkins could not have taught his university students about the Berge paper before he knew of its existence as a result of his involvement in these proceedings.

81 Dr Spargo and Prof Byrn were the most experienced salt-makers of the expert witnesses. However, because each of them did not live or work in Australia prior to 27 February 2003 their knowledge of the Berge paper does not establish any state of relevant common general knowledge in this country, as was required by ss 7(1)(a) and 18(1)(b)(i): Minnesota Mining 144 CLR at 292, 295.

82 Accordingly, I am not satisfied that Apotex has established that the invention of perindopril arginine was not novel in light of either of the two prior art patents for the purposes of s 7(1)(a) of the Act. Apotex did not prove that, even when read with common general knowledge of the Berge paper, that either the synthesis or the crystalline form patents disclosed the arginine salt at all or as a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of perindopril. Nor did it prove that the Berge paper was common general knowledge in Australia at 27 February 2003.

(a) Principles

83 The word “obvious” in s 7(2) of the Act means “very plain”. It is a question of fact whether an invention is “obvious”. However, that assessment involves a question of degree and this often will be by no means easy: Lockwood [No 2] 235 CLR at 195 [51]. The parties agreed that no question arises under s 7(3) in these proceedings. In Aktiebolaget HÄssle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411 at 427-433 [33]-[53] Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ discussed the law in respect of obviousness and the requirement of an inventive step as it had developed up to the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) (the 1952 Act). Subsequently, the Court said that that discussion was relevant and applicable to the current Act: Lockwood [No 2] 235 CLR at 193 [46]. The Court observed that (at 195 [52]):

“obviousness and inventiveness are antitheses and the question is always “is the step taken over the prior art an ‘obvious step’ or ‘an inventive step’?” ... A “scintilla of invention” remains sufficient in Australian law to support the validity of a patent.” (citations omitted, emphasis added)

84 There is no unique approach to ascertaining whether any invention claimed involves “an inventive step” for the purposes of s 18(1)(b)(ii). Sometimes, the question of whether an invention is obvious when compared to the prior art base, in light of common general knowledge, can be approached by a “problem and solution” analysis. But, this has its limitations, as the Court explained in Lockwood [No 2] 235 CLR at 200-201 [65]-[66]. They held that such an approach could be unfair to an inventor of a simple solution adding (at [65]):

“… especially as a small amount of ingenuity can sustain a patent in Australia. Ingenuity may lie in an idea for overcoming a practical difficulty in circumstances where a difficulty with a product consisting of a known set of integers is common general knowledge. This is a narrow but critical point if, as here, the circumstances are that no skilled person in the art called to give evidence had thought of a general idea or general method of solving a known difficulty with respect to a known product, as at the priority date.” (citations omitted, emphasis added)

85 The Court cautioned against treating a specification that described a problem and solution as a conclusive admission by the patentee. That was because the patentee makes such statements from the vantage point of knowing the solution. Their Honours said that statements of this type must be weighed with any evidence given by persons skilled in the art of their perception, before the priority date, of any problem: i.e. before those witnesses had been exposed to the solution contained in, or provided by, the invention (235 CLR at 211 [105]). The concept of whether a step is inventive (235 CLR at 213-214 [111]):

“… will turn on what a person skilled in the relevant art, possessed with that person's knowledge, would have regarded, at the time, as technically possible in terms of mechanics, and also as practical. That is the sense in which an idea can involve an inventive insight about a known product. A court cannot substitute its own deduction or proposition for that objective touchstone, except in the rarest of circumstances, such as where an expressly admitted matter of common general knowledge is the precise matter in respect of which a monopoly is claimed. Even if an idea of combining integers, which individually may be considered mere design choices, is simple, its simplicity does not necessarily make it obvious. Older cases concerning simple mechanical combinations illustrate this point. Common general knowledge has negative as well as positive aspects. Practical and technical issues can affect the means by which a concept may be implemented in respect of an already known vendible product, and scepticism can inhibit recognition of the utility of applying a concept or idea to a known set of integers. These are matters within the knowledge of relevant witnesses.” (citations omitted, emphasis added)

86 Thus, the practical considerations that a person skilled in the art would take into account in seeking to address a problem may affect the characterisation of a step as inventive or not. In Alphapharm 212 CLR at 432-433 [50]-[53] Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ discussed the difference between what a person skilled in the relevant art, in light of common general knowledge, might do to lead to the alleged invention by way of a series of steps or experiments that were routine as opposed to doing something that amounted to an inventive step. They drew on what Aickin J had said, with the agreement of Gibbs ACJ, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ, in The Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (1981) 148 CLR 262 at 280-281 and 286. Aickin J referred to evidence of what the inventor did, for example by way of experiment, as one means of establishing or negating the involvement of an inventive step. He said (212 CLR at 432-433 [51]):

“It might show that the experiments devised for the purpose were part of an inventive step. Alternatively it might show that the experiments were of a routine character which the uninventive worker in the field would try as a matter of course. The latter could be relevant though not decisive in every case. It may be that the perception of the true nature of the problem was the inventive step which, once taken, revealed that straightforward experiments will provide the solution. It will always be necessary to distinguish between experiments leading to an invention and subsequent experiments for checking and testing the product or process the subject of the invention. The latter would not be material to obviousness but might be material to the question of utility.” (original emphasis)

Aickin J also said (148 CLR at 286):

“It is still correct to say that a valid patent may be obtained for something stumbled upon by accident, remembered from a dream or imported from abroad, if it otherwise satisfies the requirements of the legislation. What is important is that the patent itself should involve an inventive step, whether or not it was consciously taken by the patentee and whether or not it appeared obvious to the patentee himself. The test is whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not.” (emphasis added)

87 Thus, steps that lead to the alleged invention that a hypothetical non-inventive worker in the field would have taken as a matter of routine negate the involvement of an inventive step. That is because steps of a routine character that the worker would try as a matter of course would demonstrate obviousness: Alphapharm 212 CLR at 433 [52]. In the modern context of large pharmaceutical companies, the correct approach is to ask a question along the lines of that described as the reformulated “Cripps question” (which was in an early example of the use of a written submission by Stafford Cripps KC of counsel, as Sargant LJ explained in Sharp & Dohme Inc v Boots Pure Drug Company (1928) 45 RPC 153 at 176 and see at 173 per Lord Hanworth MR; cf Blanco White, op cit at [4-211]): (I have adapted and added emphasis to this question below.)

“Would the notional research group at the relevant date, in all the circumstances, (including a knowledge of all relevant prior art and of the facts of the nature and success of the existing drug or formulation [here, the tert-butylamine salt of perindopril] be led directly, as a matter of course, to try the new or substituted drug or formulation [here, the arginine salt] in substitution in the expectation that it might well produce a useful alternative to or a better drug than [perindopril erbumine] or a body useful for any other purpose?”

88 If a hypothetical formulator or skilled addressee must pursue a complex, detailed and laborious course of action, involving a good deal of trial and error, dead ends and retracing of steps, he or she will not have taken routine steps leading to an invention as a matter of course: Alphapharm 212 CLR at 436 [58]. There Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ accepted what Maugham J had said in In re IG Farbenindustrie AG’s Patents (1930) 47 RPC 289 at 322 that mere verification was not invention. They approved his analogy advertising to the capture of the citadel in the passage below. The latter case concerned a selection patent i.e. one where, like here, a putative inventor selects, from one or more candidate substances or compounds, something to use as a substitute or derivative for an earlier component or ingredient of an original compound. There can be many possible candidates for such combinations (47 RPC at 321). His Lordship propounded a corollary to the Cripps’ question, namely, that if for practical purposes it is not obvious to skilled chemists, in the state of chemical knowledge existing at the (priority) date, that the selected components possess a special property then there is, or may be, a sufficient “inventive step” to support the patent. He said that in this respect the workings of the inventor’s mind were not usually material. Rather, the Court was “concerned, so far as subject-matter is concerned, only with the results. The invention must, of course, add something of a substantial character to existing knowledge; but the Courts do not inquire into the way in which the conquest achieved. If the language of metaphor may be used, the citadel may be captured either by a brilliant coup-de-main or by a slow and laborious approach by sap and mine according to the rules of the art; the reward is the same.

89 It is not appropriate to analyse whether a claimed invention, at least in the cases of selection or combination patents, involves an inventive step on the basis that it will not if the selected answer was “worth a try” or “obvious to try” or resulted from an exercise in trying out various known possibilities until a correct solution emerged: Alphapharm 212 CLR at 441-443 [72]-[76], [78]. Secondary evidence such as commercial success, the satisfaction of a long felt but unsolved want or need and the failure of others to find a solution to the problem is also relevant, but not necessarily determinative, of the question whether the invention is obvious: Lockwood [No 2] 235 CLR at 215-216 [115]-[116], [119].

90 The purpose of considering the prior art base, in assessing whether the invention involves an inventive step, is to look forward to see from it what a skilled addressee “is likely to have done when faced with a similar problem which the patentee claims to have solved with the invention” (235 CLR at 218 [127]). Each claim in a patent must be examined independently of the others in assessing whether an alleged invention involves an inventive step. Also in addressing the “jury” question of whether the claimed invention involves an inventive step, a judge must be very careful to avoid the wisdom of hindsight: Alphapharm 212 CLR at 443 [78].

91 The specification in the arginine patent described perindopril as being intrinsically fragile (p 1 line 24). It noted that perindopril and its non-salt compounds had previously been described in European patent EPO 049 658 (the compound patent) and that this had given examples of addition salts, with a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, that had both good bioavailability and adequate stability to be suitable for the preparation and storage of pharmaceutical compositions. The specification identified the earlier conclusion that perindopril erbumine had adequate qualities for the development of the product and was currently being marketed (p 1 lines 12-17). Then the specification explained that the tert-butylamine salt had not been capable of providing a complete solution to the problems of the product’s stability to heat and humidity. That was because of the constraints that required perindopril erbumine to use additional and more costly packaging, and that limited its shelf-life (p 1 line 24-p 2 line 7).

92 A substance is hygroscopic if it physically absorbs water. It may do so without changing its chemical structure. In that case, the substance will gain weight, being a reflection of the amount of water absorbed, thus affecting its physical stability. On the other hand, if the substance is hygroscopic and reacts with water so that its chemical structure changes, it also will gain weight but will not be chemically stable.

93 Apotex and Servier are at odds over what was the starting point identified in the specification identified for the purpose of evaluating, under s 7(2) of the Act, whether the invention involved an inventive step. Apotex said that the skilled addressee would have proceeded, as the patent explained, namely by immediately considering whether a new salt could be developed to meet the issues created by the problems with perindopril erbumine’s stability to heat and humidity. Thus, Apotex’ expert witnesses (Drs Spargo, Williams and Prof Perkins) were instructed to address what they would do, as Dr Spargo explained: “… if I was tasked with developing a new salt of perindopril which was more stable to heat and humidity than the tert-butylamine salt of perindopril.” Servier contended that the skilled addressee would see the starting point, or problem, as addressing the problems with the more general issues of perindopril’s stability to heat and humidity, including those problems experienced with the tert-butylamine salt. I will consider the correct characterisation of what the skilled addressee would have taken as the starting point later in these reasons.

94 I do not accept as reliable Prof Perkins’ evidence that, prior to the priority date, he would have considered using arginine as a counter-ion to make a salt with perindopril. His discussions with Apotex’ lawyers prompted his thought process, that led to his including arginine in his considerations. Servier did not suggest that that prompting occurred in any improper way. Rather, Prof Perkins’ cross-examination revealed how his identification of arginine as a potential counter-ion in his affidavit came about as:

“ASSOC PROF PERKINS: It was a natural progression of the discussions of the basic basicity and acidity strengths of the various functional groups and the ideas behind salt formation.

MR BANNON: And the natural progression, the progression of the discussions was prompted by the lawyers, I take it?

ASSOC PROF PERKINS: The series of questions were set by the lawyers, yes.”

95 I did not find of assistance his evidence as to how the skilled addressee, prior to 18 April 2002, would have approached dealing with making improvements to perindopril erbumine or creating a new salt. That is because I think that he approached the issue affected by the apparently accidental prompting and, once having thought of arginine in this context he, not unnaturally, continued to be influenced by this. Prof Perkins did not do any research into what information a skilled addressee may have found about salt forms that were used in other ACE inhibitors at or before 18 April 2002. He accepted that the results he could have discovered in such research may have led him down one research path rather than others. Moreover, Prof Perkins accepted that he had no expertise in 2002 as to whether a salt was suitable in a pharmaceutical context.

96 Only Prof Evans, Drs Morella and Spargo were familiar in 2002 with the pain relief substance, ibuprofen. It was marketed in a lysine salt formulation. Prof Evans had written his thesis on that substance and was aware that some research was being conducted at around that time as to whether the active moiety could also make a salt with arginine to speed up its absorption in patients. He said that this was illustrative of how the choice of the counter-ion could have pharmacokinetic and or pharmacological effects on the active moiety that would require appropriate studies to satisfy regulatory authorities as to the properties of the API. I am not satisfied that ibuprofen or its formulation as a salt with lysine, or any research involving it in salt formulation with arginine, was general common knowledge at the priority date.

97 The person skilled in the art would have recognised that perindopril erbumine was unstable in higher temperatures and humidity levels, as the experts agreed. They all suggested, in no particular order, that a number of options could be explored including development of more stable forms of perindopril such as new salts, polymorphs (i.e. crystal structures, solvates or complexes, reformulating perindopril erbumine compositions using a range of excipients or new formulations, improving the packaging or tablet manufacturing processes, developing derivatives of perindoprilat, including new prodrugs or analogues, or changing the chemical structure of the active moiety, for example, by identifying another “pril” with a more stable chemical structure than the compounds based on the active moiety, being perindoprilat.

98 As Prof Byrn said, there were at least five methods of crystallisation that a person skilled in the art could use and these involved potentially many different variables such as the choice of one or more solvents, heating rate, maximum temperature, whether, and how long, to cool the mixture, the time allowed for crystals to form, type of crystallisation vessel, its surface volume and the mixing rate, to name only some. Each variable can affect the result.