FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Eli Lilly and Company v Generic Health Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1254

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| First Applicant ELI LILLY AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 000 233 992) Second Applicant | |

AND: | GENERIC HEALTH PTY LTD (ACN 110 617 859) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT NOTES:

1. Upon the applicants, by their counsel, giving the usual undertaking as to damages, namely to:

(a) submit to such order (if any) as the Court may consider to be just for the payment of compensation, to be assessed by the Court or as it may direct, to any person, whether or not a party, adversely affected by the operation of these orders (or any continuation of them and whether with or without variation); and

(b) pay the compensation referred to in (a) to the person or persons there referred to;

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Until the determination of this proceeding or further order the respondent, whether by its servants, agents or otherwise, is restrained from, without the licence of the applicants or either of them:

(a) importing, manufacturing, supplying, offering to supply or agreeing to supply any pharmaceutical composition or formulation which includes raloxifene or any salt or solvate thereof including, without limitation, the 60mg raloxifene hydrochloride tablets registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on or about 7 June 2013 and having entry numbers 199292, 199294 and 199295 (the GH products);

(b) applying for the inclusion of the GH products on the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits; or

(c) authorising any other person to do any of the acts specified in subparas (a) or (b) above.

3. The respondent forthwith take all necessary steps to ensure that any application previously lodged by it or on its behalf for the inclusion of any of the GH products on the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits is withdrawn as soon as practicable but, in any event, by no later than 5.00pm on 27 November 2013.

4. By 12 noon on 28 November 2013 the respondent is to file and serve an affidavit sworn or affirmed by an authorised officer specifying the steps taken by the respondent for the purpose of complying with order 3 hereof.

5. Costs of the interlocutory application be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1902 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | ELI LILLY AND COMPANY First Applicant ELI LILLY AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 000 233 992) Second Applicant

|

AND: | GENERIC HEALTH PTY LTD (ACN 110 617 859) Respondent

|

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE: | 26 November 2013 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BACKGROUND

1 Before me is an application for an interlocutory injunction restraining (inter alia) the manufacture or sale of a pharmaceutical product, the active ingredient of which is raloxifene hydrochloride (raloxifene HCl). The first applicant (Lilly) is the owner of Australian Patent No 723797 (the Patent). The Patent was applied for on 20 March 1997. The earliest claimed priority date is 26 March 1996. The Patent is due to expire on 20 March 2017.

2 The second applicant (Lilly Australia) is the exclusive licensee of the Patent. Lilly Australia markets what is said to be a commercial embodiment of the invention the subject of the Patent under the brand name EVISTA. This product is a prescription only product and is indicated for the treatment of (inter alia) osteoporosis in post-menopausal women. EVISTA is registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) and it has been listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in the F1 formulary since 1 November 1999.

3 On or about 7 June 2013 the respondent obtained registration for three raloxifene HCl products (the GH products) on the ARTG. It is common ground that, unless the applicants are successful in obtaining interlocutory relief, the GH products will be listed on the PBS commencing 1 December 2013 and will be made available for sale through pharmacies in competition with EVISTA.

4 After the respondent obtained ARTG registration for the GH products, the applicants obtained orders for preliminary discovery of (inter alia) samples of the products in finished (ie. tablet) form together with samples of the bulk raloxifene HCl that is used in their manufacture. For convenience I shall refer to the first of these as the GH tablets and the second as the GH bulk.

5 On 9 September 2013, at the request of the applicants, the GH tablets and GH bulk were tested by Dr Luk in Nottingham, England. On 13 September 2013 the applicants commenced this proceeding against the respondent for infringement, or threatened infringement of claims 1, 3, 5, 8 and 9 of the Patent (the relevant claims).

6 The respondent has filed a defence denying that it has infringed, or threatens to infringe, any of the relevant claims. It has also filed a cross-claim seeking orders for the revocation of these and all other claims of the Patent. The respondent’s particulars of invalidity indicate that the respondent asserts that each of the relevant claims is invalid for lack of an inventive step and, most relevantly for present purposes, that claims 1, 8 and 9 are also invalid for lack of fair basis and lack of clarity.

THE APPLICABLE LEGAL TEST

7 There are two inquiries that must be undertaken when determining whether an applicant should be granted an interlocutory injunction. The first relates to the strength of the applicant’s claim to final relief. The second relates to the balance of convenience or, as it is sometimes expressed, the balance of the risk of doing an injustice by either granting or withholding interlocutory relief.

8 The principles to be applied in determining whether or not to grant interlocutory relief were considered by the High Court in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57, including by Gummow and Hayne JJ at [65]-[72]. Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreed at [19] with the explanation of the relevant principles in those paragraphs.

9 In O’Neill Gummow and Hayne JJ stated at [65]:

The relevant principles in Australia are those explained in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [(1968) 118 CLR 618]. This Court (Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ) said that on such applications the court addresses itself to two main inquiries and continued [(1968) 118 CLR 618 at 622-623]:

“The first is whether the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case, in the sense that if the evidence remains as it is there is a probability that at the trial of the action the plaintiff will be held entitled to relief ... The second inquiry is ... whether the inconvenience or injury which the plaintiff would be likely to suffer if an injunction were refused outweighs or is outweighed by the injury which the defendant would suffer if an injunction were granted.”

By using the phrase “prima facie case”, their Honours did not mean that the plaintiff must show that it is more probable than not that at trial the plaintiff will succeed; it is sufficient that the plaintiff show a sufficient likelihood of success to justify in the circumstances the preservation of the status quo pending the trial. That this was the sense in which the Court was referring to the notion of a prima facie case is apparent from an observation to that effect made by Kitto J in the course of argument [(1968) 118 CLR 618 at 620]. With reference to the first inquiry, the Court continued, in a statement of central importance for this appeal [(1968) 118 CLR 618 at 622]:

“How strong the probability needs to be depends, no doubt, upon the nature of the rights [the plaintiff] asserts and the practical consequences likely to flow from the order he seeks.”

10 Gummow and Hayne JJ also referred to certain observations of Lord Diplock in American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd [1975] AC 396 at 408 which their Honours criticised at [71] because they were inconsistent with Beecham and tended to:

… obscure the governing consideration that the requisite strength of the probability of ultimate success depends upon the nature of the rights asserted and the practical consequences likely to flow from the interlocutory order sought.

11 Whether an applicant for an interlocutory injunction has made out a prima facie case and whether the balance of convenience favours the grant of such relief are related questions. It will often be necessary to give close attention to the strength of a party’s case when assessing the risk of doing an injustice to either party by the granting or withholding of interlocutory relief. This is especially true if the outcome of the interlocutory application is likely to have the practical effect of determining the substance of the matter in issue or if monetary remedies, including an award of damages, or an award of compensation pursuant to the usual undertaking, are likely to be inadequate.

12 In Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 286 ALR 257 (Dowsett, Foster and Yates JJ) at [44]-[74] the Full Court considered the purpose of interlocutory relief and the principles governing the Court’s discretion to grant or withhold an interlocutory injunction. At [66] the Full Court said:

In exercising that discretion, the court is required to assess and compare the prejudice and hardship likely to be suffered by the defendant, third persons and the public generally if an injunction is granted, with that which is likely to be suffered by the plaintiff if no injunction is granted. In determining this question, the court must make an assessment of the likelihood that the final relief (if granted) will adequately compensate the plaintiff for the continuing breaches which will have occurred between the date of the interlocutory hearing and the date when final relief might be expected to be granted.

13 The Full Court also accepted (at [61]-[63]) that it is not always necessary for an applicant for an interlocutory injunction to establish that he or she will suffer irreparable harm if the injunction sought is not granted. However, whether or not the applicant will suffer irreparable harm is one of a number of matters that must ordinarily be addressed when considering the balance of convenience.

THE PATENT SPECIFICATION

14 It is apparent from a reading of the specification that the Patent relates to the use of raloxifene “in particulate form” in the preparation of formulations and compositions used in the treatment of various conditions including, relevantly, osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a condition that is characterised by a loss of bone mass often resulting in bone fracture. It is a condition that is common in post-menopausal women.

15 According to the specification at p 1, lines 9 to 11, the raloxifene of the invention (sometimes referred to in the specification, including the claims, as “formula I”) is of “a particle size range which allows enhanced bioavailability and control during the manufacturing process.” The specification also notes, at p 1, lines 35 to 36, that raloxifene is generally insoluble, and that this can affect the bioavailability of the drug. The specification then explains, at p 2, line 37 to p 3, line 2, that “any improvement in the physical characteristics of raloxifene, would potentially offer a more beneficial therapy and enhanced manufacturing capability.”

16 The specification includes, at p 2, line 3 to p 2a, line 33, a number of consistory statements which mirror the claims.

17 At p 2b, line 1 to p 3, line 31 the specification states:

It has now been found that by processing compounds of formula I, to bring their particle size within a specified narrow range, pharmaceutical compositions may be prepared which exhibit for their active ingredient both a consistent in vitro dissolution profile and in vivo bioavailability. In addition to bringing about these desired dissolution/bioavailability characteristics, the control of particle size to a narrow range has also resulted in significant improvements in manufacturing capabilities.

The mean particle size of the compounds of formula I, as set out by the invention, is less than about 25 microns, preferably between about 5 and about 20 microns. Further, the invention encompasses formula I compounds with at least 90% of the particles having a particle size of less than about 50 microns, preferably less than about 35 microns. More preferably, the mean particle size range is between about 5 and about 20 microns, with at least 90% of the particles having a size of less than about 35 microns.

It will of course be understood by those familiar with comminution process techniques that the limit set on the size of 90% or more of the particles is a limitation to further distinguish the particulate compounds of the invention from those exhibiting a broader size distribution, because of the wide variation in size encountered in all matter reduced in size by a process of comminution or particle size reduction, for example, by milling utilizing a variety of kinds of milling equipment now available, for example, hammer, pin or fluid energy mills.

The invention also provides pharmaceutical compositions comprising or formulated using the said particulate compound of the invention and one or more pharmaceutically-acceptable excipients or carriers.

18 At p 4, lines 1 to 5 the specification identifies raloxifene by its chemical name (which I need not set out) and indicates that references to raloxifene should be taken to include its salts and solvates including hydrochloride salt (HCl) which is said to be preferred.

19 At p 4, line 15 to p 5, line 8 the specification states:

Often, compounds which have poor solubility profiles can have their bioavailability enhanced by increasing the surface area of the formulated particles. The surface area generally increases per unit volume as the particle size decreases. Various techniques for grinding or milling a drug substance are well known in the art and each of these techniques are commonly used to decrease particle size and increase the surface area of the particle. It would seem reasonable that the best way to deal with any slightly soluble compound would be to mill it to the smallest size possible; however, this is not always practical or desirable. The milling process has an economic cost not only it [sic] the direct cost of the process, itself, but also with other associated factors. For example, very finely divided material presents difficulties and cost in capsule filling or tablet preparation, because the material will not flow, but becomes caked in finishing machinery. Such finishing difficulties generate nonhomogeneity in the final product, which is not acceptable for a drug substance. Additionally, the milling process, physically generates heat and pressure on the material, such conditions lead to chemical degradation of the compound, thus such milling techniques are usually kept to a minimum.

Therefore, there is always dynamic between the properties which yield the maximum bioavailability (particle surface area) and the practical limits of manufacture. The point of compromise which marks this “best solution” is unique to each situation and unique as to its determination.

20 The specification then refers to various methods for determining the size of particles. At p 5, line 14 to p 6, line 16 the specification states:

In preparing the particulate compound of the invention a compound of formula I, in its raw state, is first characterized for size using an instrument adapted to measure equivalent spherical volume diameter, that is to say a Horiba LA900 Laser Scattering Particle Size Distribution Analyzer or equivalent instrument. Typically a representative sample of a compound of formula I would be expected to comprise in its raw state particles having a mean equivalent spherical volume diameter of about 110-200 microns and with a broad size distribution.

After being characterized for size in its raw state, the raw compound is then milled, preferably using a pin mill under suitable conditions of mill rotation rate and feed rate, to bring the particle size value within the above mentioned limits according to the invention. The efficiency of the milling is checked by sampling using a Horiba LA900 Laser Scattering Particle Size Distribution Analyzer and the final particle size is checked in a similar manner. If the first pass through the mill does not produce the required size distribution, then one or more further passes are effected.

The compound of formula I in its particulate form within the above mentioned limits according to the invention may then be mixed with an excipient or carrier as necessary and, for example, compressed into tablets. Thus, for example, the particulate compound may be mixed with anhydrous lactose, lactose monohydrate, cross povidone and granulated in an aqueous dispersion of povidone and polysorbate 80. After drying and milling into granules the material can be terminally blended with magnesium stearate and compressed into tablets.

Because the particles in the raw state as well as after milling or other particle size reduction techniques are irregular in shape, it is necessary to characterize them not by measurement of an actual size such as thickness or length, but by measurement of a property of the particles which is related to the sample property possessed by a theoretical spherical particle. The particles are thus allocated an “equivalent spherical diameter”.

21 This is followed by a description of a statistical procedure which is performed to calculate a mean spherical volume diameter (referred to in other evidence as the D[4,3] measurement) which may then be compared to a sample of particles drawn from the milled raloxifene in order to determine whether the raloxifene particles are of the desired size. Since the raloxifene particles are irregularly shaped, and seldom, if ever, truly spherical, the mean spherical volume diameter (D[4,3]) provides what is necessarily a theoretical approximation of the actual mean particle size found in a given sample.

22 The specification includes a description of 25 different formulations (the Examples) all of which include raloxifene HCl as the active ingredient. Most of these formulations are for tablets, capsules and suspensions suitable for oral administration. However, there are other examples of formulations that may be administered in different ways, including an intravenous solution (Formulation 7) comprising raloxifene HCl (50 mg) and isotonic saline (1,000 ml).

23 It is apparent from the specification that the raloxifene HCl utilised in each of the Examples is said to have been sourced from bulk raloxifene HCl that has been milled to achieve the preferred particle size distribution. Thus, at p 7, lines 8 to 13 the specification states:

In all of the Examples the compound was prepared from raw form using a pin mill and consisted of particles having a mean equivalent spherical volume diameter of between about 5 and 20 microns, at least 90% of the particles having a particle size of less than about 35 microns.

24 The specification also includes a lengthy discussion of the significance of particle size on the solubility and dissolution profile of raloxifene HCl as reflected in experimental data that is reported in Tables 7, 8, 10, 11, 13 and 15. The specification suggests this data shows that superior absorption is achieved using formulations with finer particle sizes, resulting in improved bioavailability.

25 The specification states at p 22, lines 18 to 20 that “[c]ompounds of formula I, alone or in combination with another pharmaceutical agent, generally will be administered in a convenient formulation.” It also states, at p 22, lines 21 to 22, that the Examples are illustrative only and are not intended to limit the scope of the invention.

THE CLAIMS

26 There are 24 claims in total. The relevant claims are as follows:

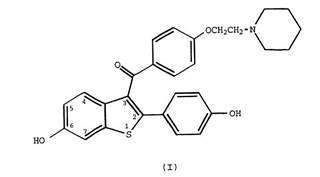

1. A compound of formula I

and pharmaceutically acceptable salts and solvates thereof, characterized in that the compound is in particulate form, said particles having a mean particle size of less than about 25 microns.

…

3. The compound of Claim 1 or 2 wherein at least about 90% of said particles have a size of less than about 50 microns.

…

5. A compound of any of Claims 1 to 4 wherein the compound of formula I is raloxifene hydrochloride.

…

8. A pharmaceutical formulation comprising or formulated using a compound as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 7 and one or more pharmaceutically acceptable carriers, diluents, or excipients.

9. A pharmaceutical composition comprising or formulated using a compound according to any one of claims 1 to 7, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or solvate thereof, in combination with one or more pharmaceutically acceptable carriers, diluents, or excipients.

…

27 The chemical structural formula referred to in claim 1 is a schematic representation of the raloxifene molecule. Hence, claim 1 is directed to a compound of raloxifene, or any pharmaceutically acceptable salt (eg. raloxifene HCl) or solvate thereof, present in the form of fine particles the average size of which is less than about 25 microns.

28 The applicants sought to establish that they had a prima facie case for final relief based upon the respondent’s infringement or threatened infringement of claims 1, 8 and 9 (in so far as they are dependent on claim 1).

SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE

29 The following three witnesses made affidavits directly relevant to the strength of each parties’ case:

Dr Luk, the applicants’ witness, is described as Chief Scientific Officer of Molecular Profiles Ltd (MPL), a company based in Nottingham. MPL provides technical services to the pharmaceutical industry including particle size analysis. Dr Luk has a Ph.D in chemistry and has many years experience as an analytical chemist. Dr Luk made five affidavits. The first affidavit was sworn on 16 September 2013, and the second to fifth affidavits were sworn on 6 November 2013. The second to fifth affidavits were received subject to an objection by the respondent which is considered later in these reasons.

Professor Polli, also the applicants’ witness, is Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy in Baltimore. He is highly qualified in the field of pharmaceuticals including, in particular, the oral absorption, formulation and biopharmaceutics of drug products. Professor Polli made one affidavit.

Professor Buckton, the respondent’s witness, is Professor of Pharmaceuticals at the University of London and Managing Director of a consulting company. Professor Buckton has many years experience in pharmaceutical processing and drug delivery systems. He made two affidavits. The first affidavit was sworn on 7 November 2013, and the second on 11 November 2013. The second affidavit was read conditionally on the basis that it would only be treated as read if the four affidavits of Dr Luk that were the subject of the respondent’s objection were admitted unconditionally.

There was no cross-examination.

DR LUK’S TEST RESULTS

30 Dr Luk was provided with a sample of the GH bulk and samples of the GH tablets. He used these for the September 2013 testing. The GH Bulk was tested in accordance with protocols the validity of which is not presently in dispute. The GH tablets were tested in accordance with extraction and analysis protocol (First Protocol) which Dr Luk prepared.

31 There were two features of the samples tested that Dr Luk attempted to measure. The first of these features was the mean particle size (D[4,3]) of the raloxifene particles found in the GH bulk and the mean particle size of the raloxifene particles extracted from the tablets. In order to measure the mean particle size of the raloxifene found in the GH tablets it was necessary for Dr Luk to perform a complex operation whereby raloxifene was extracted and separated from excipients found in the tablets. In the case of both the GH bulk and the GH tablets Dr Luk was attempting to ascertain whether the mean particle size of the raloxifene particles was less than about 25 microns. The second feature that Dr Luk attempted to measure was the percentage of raloxifene particles present in the samples that had a particle size of less than about 50 microns. In the case of both the GH bulk and the GH tablets, Dr Luk was attempting to ascertain whether at least 90% (D90) of the raloxifene particles had a mean particle size of less than about 50 microns.

32 The D[4,3] measurement is of critical significance because claims 1, and 8 and 9 (in so far as they are dependent on claim 1) require that D[4,3] be “less than about 25 microns.” The parties’ submissions concentrated on the D[4,3] measurement rather than the D90 measurement. This is understandable given that the D90 measurement is only relevant to claim 3 and other claims dependent on claim 3.

33 Dr Luk’s first round of testing, conducted in accordance with the First Protocol, indicated that the GH Bulk had a D[4,3] of approximately 29 microns. At the hearing, the applicants did not submit that the GH Bulk used in the manufacture of the GH tablets was within claim 1.

34 Dr Luk’s first round of testing suggested that the raloxifene HCl particles contained in the GH tablets had a D[4,3] of approximately 23 microns which is within the particle size range referred to in claim 1. However, Dr Luk later conceded, in response to Professor Buckton’s first affidavit, that the First Protocol was inappropriate in so far as it made use of Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) as an intermediary liquid in the extraction process.

35 Several weeks after Professor Buckton’s first affidavit was served, the applicants proposed a new protocol (the Second Protocol) for the extraction and measurement of raloxifene HCl in the GH tablets. On 29 and 30 October 2013 Dr Luk conducted further tests (as part of what seems to have involved a trial run of the Second Protocol) in the absence of Professor Buckton or any other representative of the respondent. Further testing, this time in the presence of Professor Buckton, took place on 4 and 5 November 2013.

36 The further testing by Dr Luk in accordance with the Second Protocol used a solution of Caesium Chloride (CsCl) as the density separation medium which avoided any need to use IPA. Different dispersants were also used by Dr Luk; on 4 November 2013, Dr Luk used Coulter 1A, however, the next day, he used Poloxamer 407.

37 The Second Protocol calls for the use of multiple extraction cycles which require the GH tablets that are being tested to be centrifuged and sonicated at various stages including after completion of the extraction process. According to the Second Protocol, it is only if aggregates of raloxifene HCl particles are present after extraction that further sonication should take place. The Second Protocol provides for one minute of sonication if such aggregates are present (Step 49) which is to be repeated once more if aggregates are still present (Step 51).

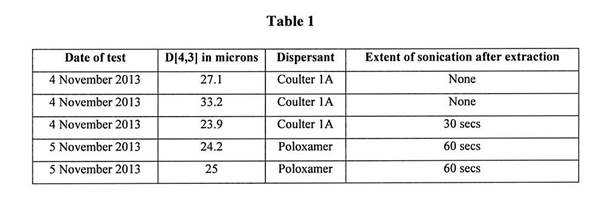

38 The results obtained by Dr Luk on 4 and 5 November 2013 may be relevantly summarised as follows:

39 Professor Buckton says that the results obtained by Dr Luk are an unreliable indication of the size of raloxifene HCl particles inside the GH tablets due to the use of centrifugation and sonication as part of the extraction process, differences in the choice of dispersant, and the use of sonication after completion of the extraction process.

40 Some of the issues raised by Professor Buckton are reflected in Table 1 above. For example, if one looks at the results using Coulter 1A, it is apparent that there is a significant variation in D[4,3] depending upon whether any post-extraction sonication was undertaken. The average of the results set out in Table 1 using Coulter 1A and no post-extraction sonication (30 microns) is substantially higher than the result obtained using Coulter 1A and 30 seconds of post-extraction sonication (24 microns).

41 Dr Luk’s evidence was that post-extraction sonication was justified due to the presence of aggregates of raloxifene HCl particles that needed to be separated before any measurement could be undertaken. He described sonication as a gentle process which, contrary to Professor Buckton’s opinion, is unlikely to affect the size of the relevant particles.

42 There is a clear conflict of opinion as between Dr Luk and Professor Buckton in relation to the reliability of Dr Luk’s D[4,3] measurements and whether Dr Luk’s tests provide acceptable scientific proof of the average size of the raloxifene HCl particles as they exist in the GH tablets. It is not possible for me to resolve this conflict of opinion for the purposes of deciding the present application.

PRINCIPLES OF CONSTRUCTION OF THE PATENT

43 The relevant principles of construction are well established and have been summarised in many previous decisions of this Court. I need only refer to several of these decisions. The first is the decision of Hely J in Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [70]-[80]; the second is the decision of the Full Court in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) at [67]. In addition to the summaries found in these decisions, I would add a reference to Lord Hoffman’s speech in Kirin Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444 at [32]-[35] where his Lordship made some important observations in relation to patent construction that have been frequently cited in judgments of this Court.

44 The following principles are of particular relevance to the proper construction of the Patent:

A patent specification is to be given a purposive construction, and must be read as a whole, in light of the common general knowledge as at the priority date, and in a practical and common sense way. It is a document written in language of the patentee’s choosing which is intended to describe an invention and define a monopoly.

If words are used in a particular way in the specification such that the draftsman attributed to those words a particular meaning, then that meaning will usually be given to those words where they appear in the claims.

There is a danger that in seeking to give a claim a purposive construction, or in seeking to read it in context, an impermissible gloss might be imposed upon the language used based upon material found in the body of the specification.

An appropriately qualified expert may give evidence on the meaning which persons skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms, and to any unusual or special meaning which such persons might give to words apart from their ordinary meaning. However, the construction of the specification and, in particular, the claims, is ultimately a matter for the Court to determine.

45 In the present case I am not construing the Patent at a trial of the proceeding, but in the context of an interlocutory application which requires an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the parties’ contentions with respect to the proper interpretation, and validity, of claims 1, 8 and 9.

THE STRENGTH OF THE APPLICANTS’ CASE

46 There are three issues that arise in relation to the proper construction of claim 1 relevant to my evaluation of the strength of the applicants’ case:

Does claim 1, 8 or 9 encompass raloxifene (or a relevant salt or solvate) that has the claimed mean particle size as it exists in a composition or formulation such as a tablet or capsule?

Is claim 1 (and therefore dependent claims 8 and 9) unclear due to the presence of the word “about”?

If claims 1, 8 and 9 encompass raloxifene (or a relevant salt or solvate) that has the claimed mean particle size as it exists in a composition or formulation such as tablet or capsule, are such claims fairly based upon the matter described in the specification?

47 The respondent submits that claim 1 is limited to a compound in bulk form which may be used to manufacture formulations or compositions in which it is the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). On this interpretation of claim 1, any measurement of D[4,3] based upon an analysis of a formulation or composition would be irrelevant except to the extent that it was evidence of the particle size of the API in bulk form.

48 The respondent submits that its construction of claim 1 is supported by the language of claim 1 and the specification as a whole. It places emphasis upon those parts of the specification which refer to the control of particle size in the context of improvements in manufacturing capabilities. It also places emphasis upon the Examples set out in the specification all of which include raloxifene HCl as the API which was milled in bulk to the preferred particle size.

49 It is clear from the specification that every size measurement made of the raloxifene HCl particles was made using the bulk. These size measurements would not necessarily be the same as those found in the compositions or formulations presented in the Examples. This is especially true of tablets that are produced through the application of compressive forces.

50 The specification does not disclose any method for determining the size of raloxifene HCl particles that may be present in tablets. The respondent submits that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine their size with any confidence, and yet this is what must be done if the applicants’ construction of claim 1 is correct.

51 On the question of construction the respondent relied upon evidence from Professor Buckton. With reference to the meaning of the phrase “in particulate form” when used to describe the compound referred to in claim 1, Professor Buckton said at para [74] of his first affidavit:

I regard this as describing the powdered API that would be used in the manufacture of a pharmaceutical composition. The reasons for this are as follows. First, the language of the claim describes it as such (“the compound is in particulate form”), and as I have mentioned, I do not regard a compressed tablet as being particulate form, it is a bonded unit dosage form, not separate particles. Secondly, in my experience, the standard practice in the industry is to measure input API size. I have never seen any one consider the notion of size in a tablet outside of patent litigation. Consequently, I believe that any formulator would regard this as referring to the size of the input API. Thirdly, I do not believe that material extracted from a tablet, for the purpose of determining the size in a tablet, can be regarded as representative of the structures that existed in the tablet – the very process of disintegration will have broken up the structure of the tablet – as such the notion of measuring what was in the tablet is not one that can be studied with any confidence. Finally, the patent specification is clear that the size is measured on input API. At no point is there any discussion of the notion that one would consider measurement of size in a tablet, nor any description of how to do so. The patent describes measuring the size of the input API and then studying the properties of the products formed from that API, which is exactly what is done in the pharmaceutical industry.

52 The applicants say that claim 1 is not limited to what Professor Buckton refers to as “input API” or, as it was described in the parties’ submissions, “bulk API”. The applicants refer to, among other things, the improved bioavailability of the described invention which the specification attributes to the smaller particle size of the API. They submit that this is an important advantage of the invention that can be obtained by the use of raloxifene in the form of particles falling within the specified range howsoever such particles are produced. They submit that it does not matter whether the milling that occurs to produce these particles takes place in the course of preparing the bulk or the tablets.

53 In further support of their contention the applicants rely upon evidence from Professor Polli. He disagrees with the views expressed by Professor Buckton on this issue. Among other things Professor Polli draws attention to the absence of any reference to “bulk” in any of the claims. He says that the term “bulk” is conventionally used to describe drug substance that contains only the relevant compound, that is to say, without any other ingredients. In his opinion, the term “compound” refers to drug substance which may exist in bulk form or in a pharmaceutical formulation or composition that might include other ingredients.

54 Professor Polli is correct to observe that the claims do not use the word “bulk” even though that term is used in the specification. However, the specification, including the claims themselves, appears to draw a distinction between, on the one hand, a “compound” and, on the other hand, a “pharmaceutical formulation” (claim 8) or “pharmaceutical composition” (claim 9) using a “compound” as claimed in claim 1.

55 The respondent submits that the applicants’ construction of claim 1 is untenable or, at least, unlikely to be accepted when the claim is read in light of the specification as a whole. I do not accept that the applicants’ construction is untenable. It seems to me that there is a reasonable argument available to the applicants that an aspect of the invention described in the specification relates to the use of fine particles of raloxifene that are within the ranges specified so as to achieve improved bioavailability. If that is an aspect of the invention described then improved bioavailability attributable to the use of particles within the specified range may be something which the skilled addressee would have readily understood could be accomplished in a variety of ways and not merely by the milling of bulk API. If the specification is to be read in that way, this would lend significant support to Professor Polli’s interpretation of the word compound as used in claim 1.

56 The respondent submits that if the construction of claim 1 relied upon by the applicants is correct then claim 1 (and its dependent claims) is likely to be invalid for lack of fair basis. It also submits that claim 1 (and its dependent claims) is likely to be invalid because it is unclear given the presence of the word “about”.

57 Claim 1, as the applicant would have it construed, is not completely lacking in textual support. As I previously mentioned, there is a consistory statement that mirrors the language of claim 1. Whether this coincidence of language is sufficient to provide the claim with fair basis, either alone or in combination with other disclosures relied upon by the applicants, is open to question. It will not do so if the consistory statement does not reflect the description of the invention apparent from a consideration of the specification as a whole: Lockwood Security Products Pty Limited v Doric Products Pty Limited (2004) 217 CLR 274 at [87]. In my opinion it is reasonably arguable that if claim 1 is construed in the manner contended for by the applicants then it will lack fair basis.

58 As to the use of the word “about” in claim 1, the question is whether the phrase “less than about 25 microns” provides a workable standard suitable to the intended use: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Limited (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 274. It is open to the Court to give to the word its ordinary meaning (ie. in this context, near, or close to) in which case I do not see why the claim would be invalid for lack of clarity.

59 Professor Buckton says that the word “about” is unclear to him and that he sees nothing in the specification to help him decide upon its meaning. However, it seems to me that there are two matters that may provide the skilled addressee with some guidance. First, some of the mean particle sizes referred to in the specification (eg. Tables 6, 9 and 14) run to one decimal place. This suggests, perhaps, that the word “about” allows for rounding of measurements. Secondly, the range of mean particle sizes for bulk raloxifene HCl after milling is 6–15 microns (Table 12). This suggests, perhaps, that the scope of the claim makes ample provision for measurement errors before one even gets to the word “about”. This might also suggest that the word “about” has been introduced not to allow for measurement error, but to allow for rounding.

60 Having concluded that the respondent has a reasonably arguable case that claim 1, if given the interpretation relied upon by the applicants, would lack fair basis, it is not necessary for me to say more in relation to lack of clarity. I am satisfied on the evidence before me that the respondent’s invalidity case, considered as a whole, is reasonably arguable though I would not put it any higher than this.

BALANCE OF CONVENIENCE

61 There was considerable evidence relied upon by both sides in relation to the balance of convenience. The affidavit evidence read by the respondent included expert evidence from an economist (Mr Houston) and an accountant (Mr Meredith) which was relied upon to demonstrate that it would be difficult to quantify the loss that would be suffered by the respondent in the event that an interlocutory injunction was “wrongly” granted, that is to say, in circumstances where it was subsequently held that the GH tablets did not infringe any of the relevant claims. Most of the respondent’s expert evidence focused on the difficulties involved in quantifying the harm that would be suffered by the respondent if it lost what was referred to in its evidence as the first mover advantage in the pharmacy market for raloxifene products.

62 Ms Buckley, the respondent’s Marketing Manager for generic medicines, identified four categories of loss, all of which are in the nature of loss of opportunity, that she says the respondent will suffer if the interlocutory injunction sought by the applicants is granted but it is later established that the GH tablets do not infringe. Her evidence was to the following effect:

As the first company (or one of a small number of companies) to supply a generic raloxifene product in Australia, the respondent would be well placed to secure orders from pharmacies for that product. It would have no competitors (other than the applicants’ authorised product) for a period of time and pharmacies would be motivated to secure a stable source of generic raloxifene as soon as possible.

Being among the first movers can lead to winning and maintaining significant market share because, once a pharmacy starts to dispense a particular generic brand, it will often be reluctant to switch to another generic brand.

Being among the first movers can create sales opportunities that the respondent would not otherwise have had because the availability of a generic raloxifene product may motivate pharmacies to deal with the respondent where they would not otherwise have done so.

Pharmacies tend to support pharmaceutical companies that have a reputation for being committed to expanding the range of generic pharmaceutical products available in Australia. The opportunity to be among the first movers in relation to a generic raloxifene product in Australia will help Generic Health to build such a reputation.

63 It is apparent from Ms Buckley’s evidence that her views as to the extent of the loss likely to be suffered by the respondent depend to a considerable extent upon the likelihood of the respondent being the first supplier, or one of the first suppliers, of generic raloxifene to pharmacies in Australia. However, whether or not the respondent would obtain any significant first mover advantage is a matter that I regard as highly doubtful.

64 Against the possibility that generic suppliers (including the respondent) might enter the market, the applicants lodged an application to list their own generic raloxifene HCl product on the PBS. It remains open to the applicants to withdraw that application at any time prior to 29 November 2013. I was informed by the applicants that in the event an interlocutory injunction is granted, they will withdraw their application for PBS listing of the generic product, but that if an interlocutory injunction is not granted, then the applicants will allow their application to proceed to listing. In that event an authorised distributor (Aspen) will commence to sell the applicants’ product as a “generic” product commencing 1 December 2013. Aspen is one of the respondent’s major competitors in the market for generic medicines.

65 Listing their own generic product on the PBS is clearly not the applicants’ preferred course but it is one that they say they will follow in order to mitigate their loss in the event that the respondent is permitted to proceed with its application to list the GH products on 1 December 2013.

66 Another supplier of generic medicines (Apotex) is presently the subject of an interlocutory injunction in favour of the applicants restraining it from (inter alia) supplying raloxifene products in Australia. Apotex is another of the respondent’s major competitors. Whether the applicants would be able to hold their interlocutory injunction against Apotex in circumstances where there would be a material change in circumstances as a result of another generic supplier (the respondent) entering the market is highly doubtful.

67 If the interlocutory relief sought by the applicants is refused, four significant consequences will follow. First, as a result of the GH products being included in the PBS on 1 December 2013, there will be an immediate 16% price reduction to the Price to Pharmacists (PTP) for EVISTA pursuant to relevant provisions of the National Health Act (1953) (Cth). Secondly, unless restrained by interlocutory injunction, it would be open to other generic suppliers who have obtained ARTG registration to obtain a PBS listing for their own raloxifene products quite quickly. This is because PBS listing occurs on a monthly basis after the first generic product has been listed. Thirdly, the applicants are likely to suffer a substantial loss of market share within 3 or 4 months of the 16% price reduction taking effect. This loss of market share may be as much as 40-60% of the relevant market. Fourthly, if an interlocutory injunction is not granted and the applicants ultimately succeed against the respondent and any other generic suppliers, it will be up to the Minister of Health to decide whether to restore EVISTA to the F1 formulary. The PTP for EVISTA will also need to be re-negotiated in the context of price reductions that will have occurred as a result of the respondent and other generic suppliers entering the market. The evidence suggests that it is unlikely the PTP for the applicants’ product will be restored to current levels even if the applicants are successful in restraining the respondent and other generic suppliers from continuing to sell their raloxifene products.

68 I accept that there will be difficulties involved in assessing the loss suffered by the respondent if it is wrongly excluded from the pharmacy market for raloxifene products in the short to medium term. On the other hand, the effect on the applicants’ market share and revenue if an interlocutory injunction is refused is also difficult to predict. If other generic suppliers (leaving aside Aspen) were to enter the market before any proceedings brought against them by the applicants were finally determined (which I consider a strong possibility) then it is likely to be very difficult to determine how the applicants’ losses, assuming that they can be quantified, should be apportioned as between the various generic suppliers. On one view, the loss of 40–60% of the applicants’ share of the pharmacy market for raloxifene products (albeit temporary) might be the direct and foreseeable result of the respondent’s entry into that market, notwithstanding that it was followed by much larger generic suppliers which also entered the market and which captured some part, or even most, of the applicants’ market share. On the other hand, the Court would most likely be invited by the respondent to apportion the losses suffered by the applicants between all generic suppliers who contributed to the applicants’ losses. This would be a difficult task. The difficulties in quantifying and apportioning the applicants’ losses would increase significantly if the raloxifene products supplied by the respondent were ultimately held to infringe, but those sold by other generic suppliers were held not to infringe.

69 There are a number of other matters relevant to the balance of convenience which I also take into account.

70 First, the Court has informed the parties that it can offer them dates for a final hearing on all liability issues in June 2014. Earlier hearing dates could be made available but, given the breadth of the respondent’s challenge to the validity of the relevant claims, I doubt that it would be feasible to hear the matter before June 2014. The parties have indicated that they can be ready for trial by then.

71 Secondly, the Patent has been in force for many years and EVISTA has been listed in the FI formulary for most of that time. The evidence suggests that the applicants’ raloxifene product, while not a “blockbuster” drug, is an important part of Lilly Australia’s inventory of originator products. The evidence also suggests, though I accept it is not at all specific, that Lilly Australia will need to shed positions in the event that the GH products achieve PBS listing and are launched onto the pharmacy market before new originator products in the latter stages of development can be brought to market by the applicants.

72 Thirdly, the evidence shows that the respondent obtained ARTG registration for the GH products on or about 7 June 2013. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I would infer that the respondent was aware of the fact that the applicants and Apotex were party to a proceeding (the Apotex proceeding) that raised the same issue of construction that arises in this proceeding. The Apotex proceeding was commenced in May 2012 but is yet to be fixed for hearing.

73 Since 15 April 2013 it was open to the respondent to commence its own proceeding for a non-infringement declaration and orders for revocation of any claims it contends are invalid and which might be seen as standing in the respondent’s way: see ss 125-127 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) as recently amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth). The relevant amendments, which took effect on 15 April 2013, have given the non-infringement declaration new life. Among other significant changes made by the recent amendments, a party may seek a non-infringement declaration and an order for revocation of any claims it alleges to be invalid, in the same proceeding.

SHOULD INTERLOCUTORY RELIEF BE GRANTED?

74 I am not satisfied on the evidence before me that the applicants have a strong case for final relief. Nor, however, would I describe the applicants’ case for final relief as weak. It suffices to say that I am satisfied that the applicants have demonstrated a “prima facie” case for final relief in the sense that that expression is to be understood in light of the relevant authorities.

75 As to the balance of convenience, I am satisfied that it favours the granting of an interlocutory injunction that will maintain the status quo until the issues in the proceeding can be determined. The willingness of the parties, especially the applicants, to make themselves ready for a final hearing in June 2014 is a matter which I have given considerable weight in reaching this conclusion.

FORM OF INTERLOCUTORY RELIEF

76 There will be an interlocutory injunction in appropriate form restraining the respondent from importing, manufacturing, supplying, offering to supply or agreeing to supply any of the GH products or any other raloxifene product, until the determination of this proceeding or further order.

77 The applicants also seek an interlocutory order (the mandatory order) requiring the respondent to take all necessary steps to withdraw all applications for inclusion of any of the GH products on the PBS. The respondent submits that the mandatory order should not be made. It submits that merely by arranging for the listing of the GH products on the PBS, the respondent would not be committing any act of infringement.

78 In the present case I am satisfied that the mandatory order should be made. It seems to me that it is sufficiently arguable that by procuring the listing of the GH products on the PBS the respondent will have exploited the claimed invention and thereby infringed the exclusive right conferred on the patentee by s 13 of the Act. I am also satisfied that the balance of convenience strongly favours the making of the mandatory order. Once it has been decided that the respondent should be restrained, until the determination of the proceeding, from supplying the GH products, there does not appear to me to be any compelling reason for permitting the respondent to proceed with its application for PBS listing.

RULING ON ADMISSIBILITY

79 I previously referred to the respondent’s objection to four of the affidavits made by Dr Luk. The respondent submits that it was denied a proper opportunity to respond to these affidavits due to their late service and the applicants’ non-compliance with directions for the filing of the affidavit evidence that was to be relied upon at this hearing. I have considered the respondent’s objection on that basis, and also as if made under s 135 of the Evidence Act 1990 (Cth).

80 The fact that Dr Luk and the applicants saw the need to conduct further tests after reading Professor Buckton’s first affidavit criticising (inter alia) the use of IPA is hardly surprising. Ordinarily, I would have expected the applicants to have relisted the matter so that they might obtain the Court’s approval for a further round of tests and a further round of affidavit evidence. In the present case, however, the respondent was given an opportunity, pursuant to directions made by me, to comment on the protocol to be followed by Dr Luk before he carried out his first round of tests. For reasons not explained by the evidence the respondent did not respond to the proposed protocol which the applicants provided to the respondent in accordance with my directions. The applicants submit that the need for them to undertake further tests, and to file the further affidavits from Dr Luk, were due, in part at least, to the respondent’s non-compliance with those directions.

81 I have had close regard to Professor Buckton’s second affidavit which, it seems to me, deals with the subsequent testing (at which he was present) and Dr Luk’s second to fifth affidavits in considerable detail. Given the nature of the application before me, I am not satisfied that the late service of Dr Luk’s four affidavits is likely to have caused the respondent any significant prejudice or unfairness. I have therefore decided that the four affidavits made by Dr Luk that were received subject to the respondent’s objection, and the second affidavit of Professor Buckton that replies to them, should be admitted unconditionally.

COSTS

82 The costs of the interlocutory application will be reserved.

I certify that the preceding eighty-two (82) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Nicholas. |

Associate: