Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 909

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION |

THE COURT MAKES THE FOLLOWING INTERIM DECLARATIONS:

1. Entry into the Original Millmerran Contract by Pozzolanic Enterprises Pty Ltd (“Pozzolanic”), Pozzolanic Industries Limited and Millmerran Power Partners dated 30 September 2002 does not engage a contravention of s 46 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the “Act”).

2. Entry into the Amended Millmerran Contract on 28 July 2004 does not engage a contravention of s 46 of the Act.

3. The conduct in relation to the second election to proceed by electing in March and April 2005 to deploy the capital for the purpose of installing processing facilities at Millmerran does not engage a contravention of s 46 of the Act.

4. Entry into the Original Millmerran Contract engages a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act on the part of Pozzolanic and a contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act on the part of Pozzolanic and Queensland Cement Limited (“QCL”).

5. To the extent that the identified provisions of the Original Millmerran Contract had the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the relevant market upon inclusion of the pleaded provisions in making the contract, that effect or likely effect became dissipated by the end of 2003 with the result that any effect or likely effect upon competition was then attributable to the compromised quality of the Millmerran flyash rather than the effect or likely effect of the identified provisions.

6. Entry into the Amended Millmerran Contract engages a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii), as a substantial purpose, among other purposes, of entry into the amended provisions and the continuing affirmation of the Original Millmerran Contract provisions, as amended, was to prevent a rival of Pozzolanic and Cement Australia Pty Ltd from securing access to Millmerran unprocessed flyash and to prevent a rival from entering the South East Queensland concrete grade flyash with processed Millmerran flyash.

7. The conduct in relation to the second election to proceed in March and April 2005 does not engage a contravention of s 45 of the Act.

8. Entry into the Fly Ash Agreement between Tarong Energy Corporation Limited (“TEC”) and Pozzolanic of 26 February 2003 engages a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act on the part of Pozzolanic and a contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act on the part of QCL.

9. Pozzolanic and Cement Australia contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the pleaded provisions of the Fly Ash Agreement between TEC and Pozzolanic of 26 February 2003 in relation to both the Tarong Power Station and the Tarong North Power Station.

10. Entry into the arrangements by Pozzolanic and Cement Australia to construct a classifier at the Tarong North Power Station does not engage a contravention of s 45 of the Act.

11. Pozzolanic and QCL contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the pleaded provisions of the Swanbank Contract of 1993 as amended by the letter of 9 September 1998 and the subject of the Agreement of 30 September 1998, in the period, relevantly for these proceedings, from the beginning of 2001 to 31 May 2003.

12. Pozzolanic and Cement Australia contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the pleaded provisions of the Swanbank Contract of 1993 as amended by the letter of 9 September 1998 and the subject of the Agreement of 30 September 1998, in the period, relevantly for these proceedings, from 1 June 2003 to 31 December 2004 and then from 31 December 2004 until 30 June 2005.

13. Pozzolanic and Cement Australia contravened s 45(2)(a)(ii) by entering into the extension arrangements until 30 June 2005 in relation to the Swanbank Contract.

14. The contentions that Mr Leon was knowingly concerned in particular contraventions of the Act are not made out.

15. The contention that Mr White was knowingly concerned in a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) and s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act in relation to aspects of the Swanbank contractual arrangements is made out.

16. The contention that Mr White was otherwise knowingly concerned in contraventions of the Act is not made out.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are directed to prepare and submit formal orders for the consideration of the Court.

2. The costs of the proceeding are reserved.

3. The parties consider the extent to which any information contained in the reasons for judgment is confidential to a party or otherwise falls within orders for the preservation of confidentiality.

4. The parties are directed to confer concerning the matters at Order 3 with a view to enabling the matter to be re-listed to hear submissions concerning the question of the extent to which the reasons for judgment ought to be redacted or orders for confidentiality otherwise be addressed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

| QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 295 of 2008 |

| BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

| AND: | CEMENT AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 104 053 474 First Respondent CEMENT AUSTRALIA HOLDINGS PTY LTD ACN 001 085 561 Second Respondent CEMENT AUSTRALIA (QUEENSLAND) PTY LTD FORMERLY QUEENSLAND CEMENT LTD ACN 009 658 520 Third Respondent POZZOLANIC ENTERPRISES PTY LTD ACN 010 367 898 Fourth Respondent POZZOLANIC INDUSTRIES PTY LTD ACN 010 608 947 Fifth Respondent CHRISTOPHER GUY LEON Sixth Respondent CHRISTOPHER STEPHEN WHITE Seventh Respondent |

| JUDGE: | GREENWOOD J |

| DATE: | 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 |

| PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PART 1

1.1 Introduction

1 This proceeding concerns material known as flyash, its composition, where and how it is first produced and how it might be accessed and treated or further processed at the primary production site (on-site) and how it might be stored, transferred and handled on-site or off-site at points of intermediate storage. It concerns the contracts and arrangements for the acquisition of flyash from and by firms, and the contracts and arrangements for the supply of a particular kind, standard or quality of flyash and the field of actual and potential sellers and buyers of flyash of that kind, standard or quality.

2 It concerns whether there is a market for flyash, and if so, how the product is properly understood and defined by those actually or potentially engaged in rivalry for the product in a relevant market, whether there is a functionally separate market for the acquisition of raw or unprocessed flyash loosely described for present purposes as simply an upstream product market, and a functionally separate market for the sale of flyash of a particular kind, standard or quality exhibiting particular characteristics, loosely defined for present purposes as a downstream product market.

3 It concerns questions of how the market is, or markets are, to be defined in a practical applied sense having regard to the evidence of participants actually engaged (or potentially engaged or seeking to be engaged) in transactions probative of a field of rivalry exhibiting close competition and the economic principles to be applied in answering that question aided, where relevant, by expert economic evidence.

4 It concerns, having engaged in the process of market definition as a tool for determining whether a relevant respondent corporation enjoys market power (having regard to the particular factors actually in play including potential, but real, threats of entry informing whether the corporation is free from constraint in setting prices or dictating the terms of trade), whether that corporation has a substantial degree of power in a relevant market, and whether the corporation has taken advantage of that substantial degree of market power in taking an impugned conduct step such as entering into a particular contract for the acquisition of flyash on particular terms, conditioned by particular contextual circumstances. As the respondents observe at para 14.14 of their closing submissions in the quoted passage in the reasons of Heerey and Sackville JJ in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (2003) 129 FCR 339 (“Safeway”) at [303] (in turn relying on the observations in Boral Besser Masonry Ltd (now Boral Masonry Ltd) v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (“Boral v ACCC”) (2003) 215 CLR 374 at [140]), the question of market power is approached, consistent with s 46(3) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the “Act”) by examining the “actual conduct of the alleged contravener in the market over the whole of the relevant period”.

5 The question of “taking advantage” also requires, before reaching the point of answering the question of whether one or more of the statutorily proscribed purposes subsisted, an examination of “not only what the firm did, but why the firm did it” [emphasis added] (Safeway at [329] and the quoted authorities). Having understood why the firm did what it did, an objective question then arises of whether such a firm so acting, in similar circumstances, in a hypothetical world in which such a firm did not enjoy a substantial degree of power in the relevant market, could have engaged in the impugned conduct step. In determining this question of whether there is a business rationale for the impugned conduct which explains conduct as other than as the expression of the use of market power, the respondents contend that these observations in Safeway are apt to mislead, as an analysis of the business rationale is directed to not only the actual matters considered by the decision-makers on the facts, but also, those matters (the full field or portfolio of business rationales) which could have been taken into account by a firm in the actual circumstances of the relevant firm or a firm in a hypothetically contestable market.

6 The proceeding thus concerns the resolution of that matter, an examination of whether any of the statutorily proscribed purposes under s 46(1) subsisted and whether the contended contraventions of s 46 are made out.

7 It also concerns questions of whether particular respondents made contracts or arrangements containing identified provisions which firstly, had the purpose of substantially lessening competition; secondly, had the effect of substantially lessening competition; or thirdly, would be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition, for the purposes of s 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act, and whether a respondent corporation gave effect to an identified provision of particular contracts or arrangements where that identified provision (or one or more provisions taken together) has the purpose or has, or is likely to have, the effect of substantially lessening competition for the purposes of s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act. It concerns questions of how the identified provisions came to be included in the relevant contracts or arrangements and which actuating individuals held a particular purpose or purposes. It concerns assessments of the purpose, effect or likely effect of particular provisions of a contract or arrangement either alone or together with other identified provisions in that contract or arrangement, or in conjunction with other identified provisions of other contracts or arrangements.

8 In the alternative to s 45(2), contended contraventions of s 47 are said to have been made out.

9 Other respondents (corporations and individuals) are said to have caused a respondent to engage in a contravention of the Act and to have been knowingly concerned in the contraventions of others, or to have aided, abetted or counselled or procured the contraventions of others.

10 It is, of course, necessary to give precise content to the Commission’s claims.

11 The proceeding comprehends six primary and separate contended conduct contraventions (in effect, six separate cases over a primary period from 2001 to 31 December 2006) by one or more of the respondents together with a seventh case based upon the contention that the individual respondents were knowingly concerned in particular conduct contraventions of the relevant corporate respondents, and contentions are also made against particular corporate respondents inter se of being knowingly concerned in the contraventions of other corporate respondents. It involves many sitting days, a large number of documents, much affidavit and oral evidence, many spreadsheets of costs data and very extensive and detailed written submissions (1,132 heavily footnoted pages) and lengthy oral submissions. Having regard to the calculus of factors relevant to each of the integers engaged by ss 46, 45(2)(a)(ii), 45(2)(b)(ii) and 47, it seems to me important to identify the content of each of the contended contraventions by reference to the precise way in which the Commission has pleaded each case by reference to the Third Further Amended Statement of Claim (the “3FASOC”). This is particularly so as, for all practical purposes, every element within the calculus of factors relevant to each of the contended contraventions in each cluster of events. Moreover, it seems to me important to examine the contended conduct contraventions essentially, although not wholly, in a linear way by assessing the incremental aggregation of relevant factors present at the point on the continuum when each contravention is said to have occurred (whether exercising power, making contracts containing particular provisions or giving effect to them). Nevertheless, it is important to understand, for example, what were the features of the field of actual or potential rivalry on 30 September 2002 when the third respondent, Cement Australia (Queensland) Pty Ltd (“QCL”) and the fourth respondent, Pozzolanic Enterprises Pty Ltd (“Pozzolanic”), is said to have enjoyed a substantial degree of power in a relevant market, and what factors extant at that conduct event (or potentially engaged) determine whether QCL did something that used or took advantage of that market power, rather than doing something which is other than the expression of market power?

12 The six separate and primary contended conduct contraventions by one or more of the respondents engage these events:

1. entry into the Original Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002;

2. entry into the Tarong Contract on 26 February 2003;

3. arrangements relating to an amendment in July 2004 to the Millmerran Contract giving rise to the Amended Millmerran Contract and what is called the “first election to proceed” with the Millmerran Contract;

4. entry into the Swanbank Contracts and Arrangements extending the terms of the Swanbank extension up to 31 December 2006;

5. entry into arrangements in March and April 2005 consisting of an approval of capital expenditure for the installation of a classifier at Millmerran under the terms of the Amended Millmerran Contract, described as the Millmerran Second Election to Proceed;

6. entry into arrangements in 2005 and, more particularly, in 2006 for the installation of a classifier at Tarong North, the installation and commissioning of that plant and consequent removal of reject flyash from the classifier into the Tarong North silo.

13 I will set out in some detail the essential pleaded facts and contentions of the Commission going to each of these events and the factors in issue. Before doing so, it is convenient to note that these reasons are arranged in the following way:

SCHEDULE OF CROSS-REFERENCES

| PART | HEADING | PAGES | PARAGRAPHS |

| PART 1 | Introduction and identification of the elements of each of the claims made by the Commission; Schedule of Cross-References | 1-51 | [1] to [187] |

| PART 2 | A brief summary of the respondents’ contentions in answer | 51-56 | [188] and [189] (and sub-parts) |

| PART 3 | Flyash and aspects of the evidence of Dr Nairn | 56-73 | [190] to [253] |

| PART 4 | The respondents and other relevant ownership entities; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Blackford; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Clarke; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Arto and Mr Maycock | 73-89 | [254] to [322] |

| PART 5 | Tarong and Tarong North Power Stations; The evidence of Mr Huskisson; the contractual history; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Collingwood; Production volumes and contended constraints on production of concrete grade flyash at Tarong and Tarong North; Mr Druitt’s evidence; The Tarong facilities; The production constraints at Tarong; The Tarong North facilities; The production constraints at Tarong North; Bottlenecks; The production records; Aspects of Ms Boman’s spreadsheets; The criticisms of Mr Druitt’s evidence; A comparison of Mr Druitt’s evidence with the sales and production data; | 90-154 | [323] to [622] |

| PART 6 | Swanbank Power Station; The contractual history; Mr Christy’s evidence; | 154-170 | [623] to [698] |

| PART 7 | Variability of the Swanbank flyash and aspects of the evidence of Mr Blackburn | 171-180 | [699] to [713] |

| PART 8 | Millmerran Power Station; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Hunt; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Gamble | 180-196 | [714] to [780] |

| PART 9 | Gladstone Power Station | 196-205 | [781] to [821] |

| PART 10 | Callide B and Callide C | 205-207 | [822] to [832] |

| PART 11 | Stanwell Power Station | 207-208 | [833] and [834] |

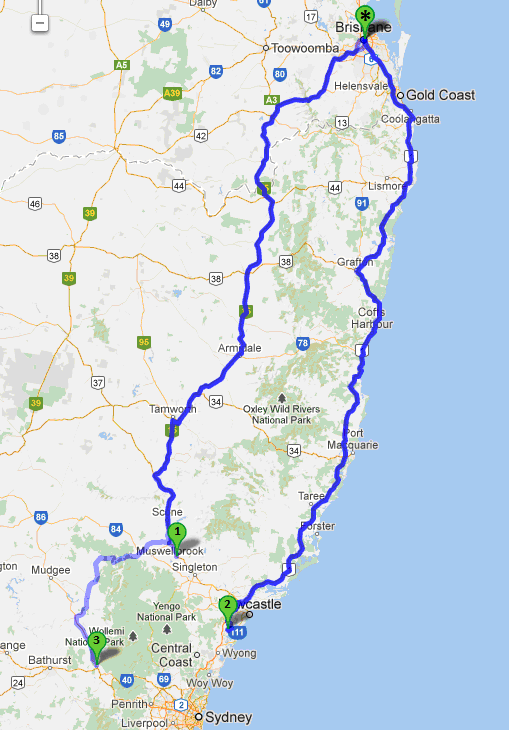

| PART 12 | Flyash Australia Pty Ltd and the New South Wales Power Stations; Aspects of the evidence of Mr Clarke | 208-223 | [835] to [902] |

| PART 13 | Sunstate Cement Ltd and the evidence of Mr Ward | 223-229 | [903] to [928] |

| PART 14 | The relevant terms of the Millmerran Ash Purchase Agreement | 229-239 | [929] and [930] |

| PART 15 | The relevant terms of the Tarong Energy Fly Ash Agreement | 238-245 | [931] |

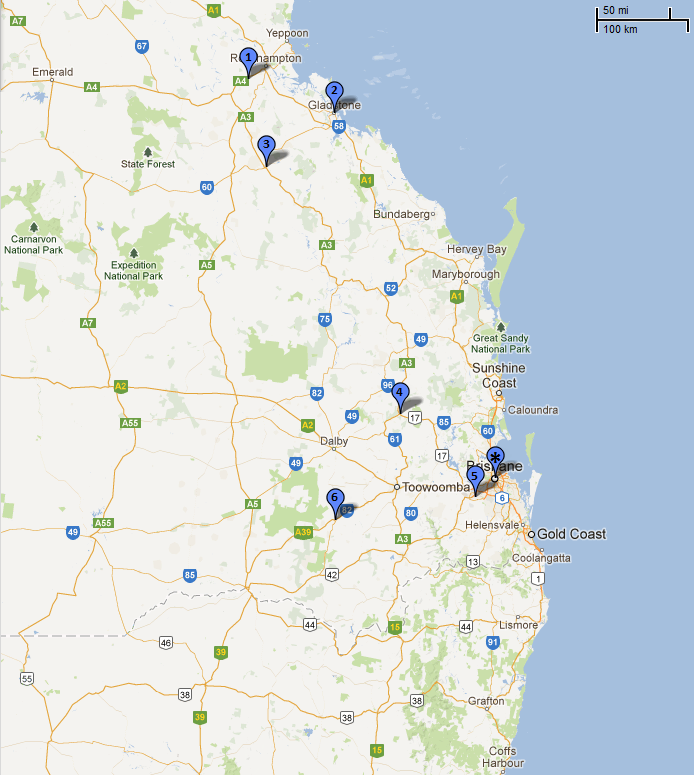

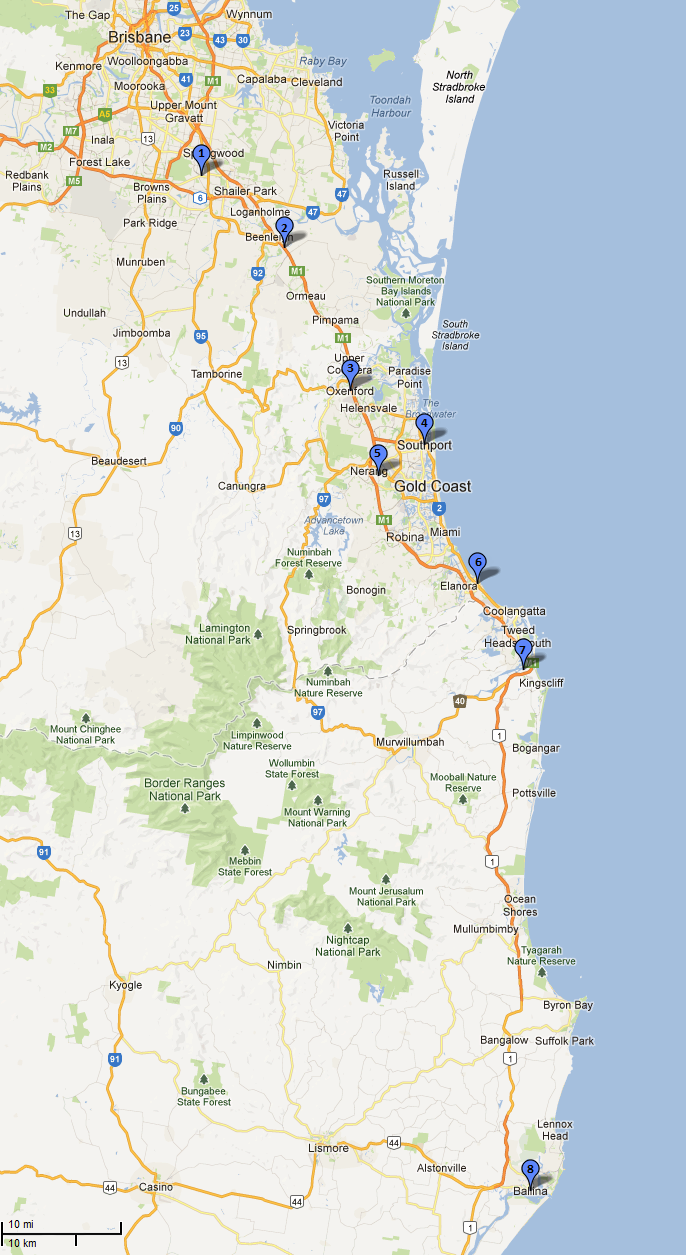

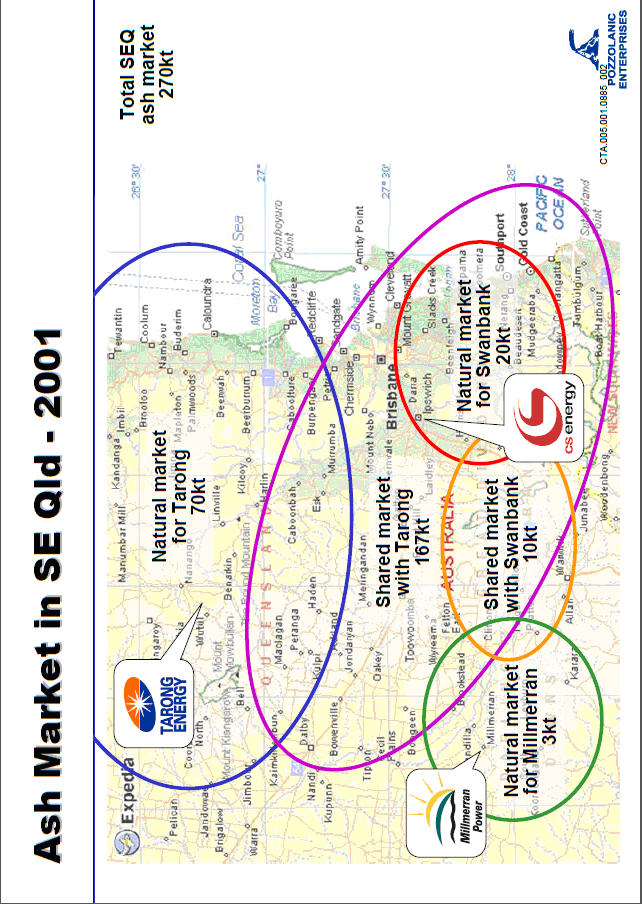

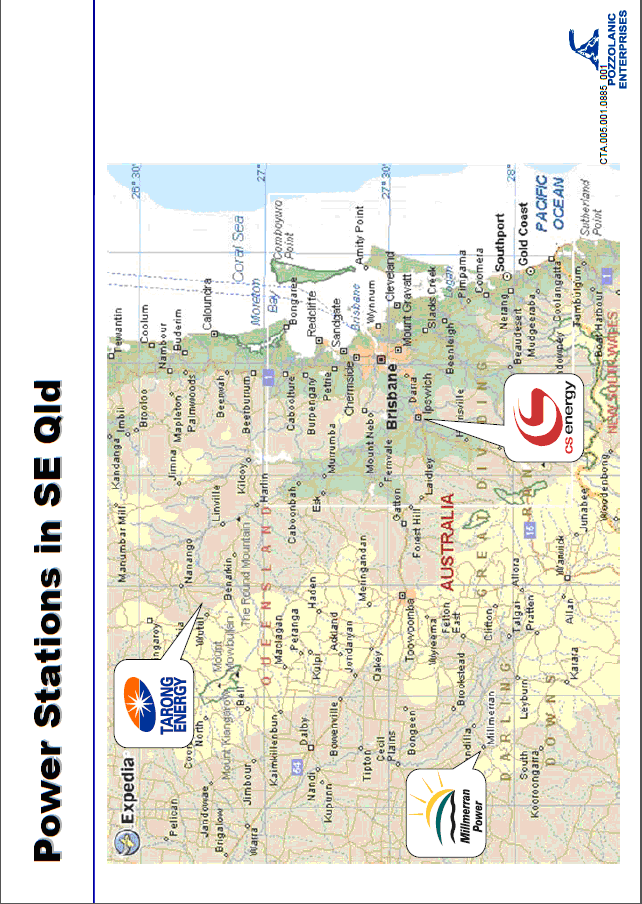

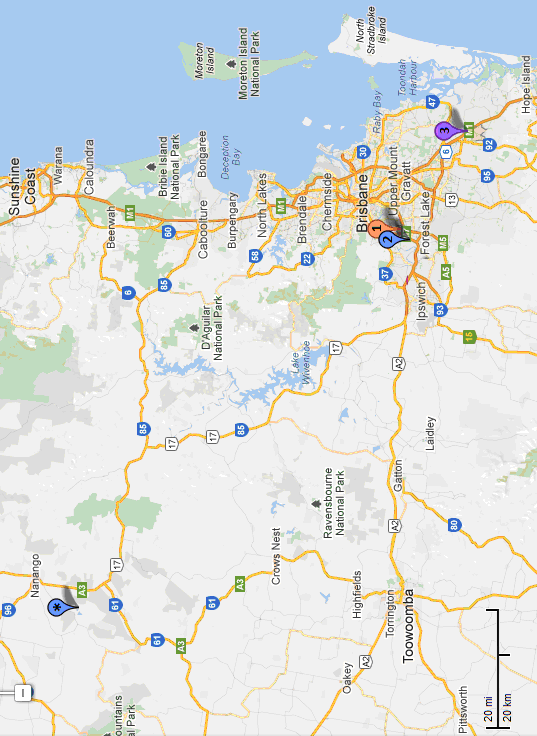

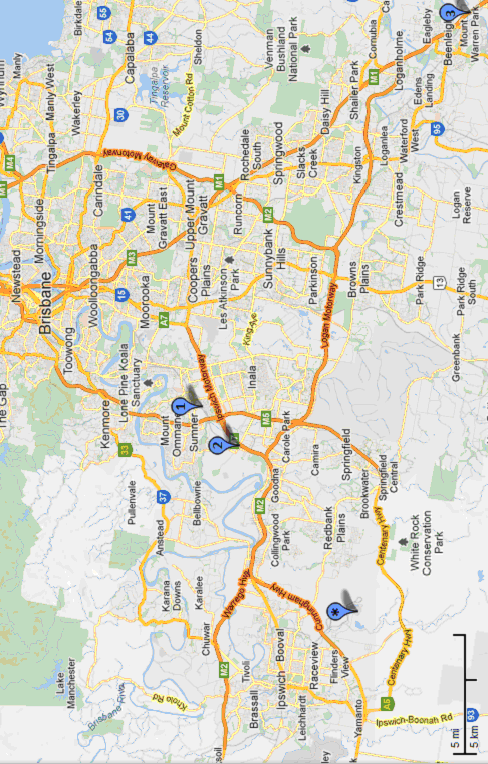

| PART 16 | Illustrative Maps (Annexed at “A” to “G”) | 246 | [932] to [938] |

| PART 17 | The organising principles to be applied in identifying relevant markets and determining whether a corporation has a substantial degree of power in a relevant market | 246-260 | [939] to [983] |

| PART 18 | Descriptions and references adopted by one or more of the respondent companies concerning the market within which the relevant actors perceived they were operating; Mr O’Callaghan’s views; The March 2001 Ash Report; Pozzolanic’s description of itself and the market in which it operates contained in the EOI submitted to TEC; The supporting Capability Statement; FAA’s views; Adelaide Brighton’s views; Pozzolanic’s Presentation to TEC in support of the EOI; The TEC tender process; The QCL 14 November 2001 Board meeting and the 2002 QCL Group Consolidated Budget; The propositions put by Pozzolanic to Millmerran as part of that tender process; Transpacific’s view; Pozzolanic’s view of the ash market; Mr Wilson and Mr Ridoutt’s Presentation to MOC; FAA’s view put to MOC; Pozzolanic’s assessment of its market position in the Business Plan analysis of 9 November 2001; Mr Ridoutt’s email of 26 September 2003; Pozzolanic’s tender to TEC; Mr Hunt’s assessment of the tenders; Mr Arto’s assessment of the market and market dynamics with major buyers; Mr Arto’s characterisation of the geographic market; Mr Maycock’s macro view; Mr Wilson’s briefing email of 4 March 2002; The Ash Market in SEQ Board paper of March 2002; Mr Klose’s email of 2 April 2002; The January/February 2002 Board Report; The Ash Market in SEQ September 2002 Board paper | 261-306 | [984] to [1146] |

| PART 19 | Logistics, transport costs, direct delivery to customer’s batching plant from the power station, indirect delivery through intermediate storage to the customer’s batching plant and the evidence of Ms Deborah Reich; The logistics task and its functions; Ms Reich’s references to categories of cost; Ms Reich’s further assessment of categories of transport costs; Ms Reich’s references to a logistics costs model; Ms Reich’s data in relation to average transport costs to particular customers from particular sites; Intermediate storage and direct delivery; Gladstone movements into South East Queensland; Stock-outs; The contingency plan; The spreadsheet data in relation to “actual chargeback costs” and “intermediate delivery costs” | 306-344 | [1147] to [1301] |

| PART 20 | Direct delivery of flyash and particular pricing transactions; Pricing, margins and production costs; Price increases notified by QCL in its delivered pricing; Pricing, revenue, EBIT and OPAT statistics; Further considerations | 344-362 | [1302] to [1362] |

| PART 21 | Other participant evidence: Nucon Pty Ltd; Aspects of Mr Neumann’s evidence | 362-375 | [1363] to [1425] |

| PART 22 | Aspects of the evidence of Mr Michael Cooper | 375-408 | [1426] to [1576] |

| PART 23 | Wagner Investments Pty Ltd | 408-417 | [1577] to [1621] |

| PART 24 | Transpacific Industries Pty Ltd | 417-426 | [1622] to [1671] |

| PART 25 | Independent Flyash Brokers Pty Ltd and the evidence of Mr Alan Forbes | 426-442 | [1672] to [1734] |

| PART 26 | The Neilsen Group of Companies and the evidence of Mr Panuccio | 442-445 | [1735] to [1748] |

| PART 27 | The Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads and the evidence of Mr Vanderstaay | 446-449 | [1749] to [1761] |

| PART 28 | Market Definition; Consideration of aspects of the expert evidence of Mr Houston and Professor Hay; The upstream market and the downstream market | 449-468 | [1762] to [1834] |

| PART 29 | Market Power; Considerations going to the question of whether a substantial degree of power in a relevant market subsisted in any party; Consideration of the aspects of uncertainty discussed by Professor Hay; Consideration of the principles to be applied; Consideration of s 46(3) | 468-490 | [1835] to [1893] |

| PART 30 | Taking advantage of market power, the organising principles and related considerations | 490-497 | [1894] to [1913] |

| PART 31 | Professor Hay’s opinion evidence concerning the “legitimate business reasons” going to the question of whether a party took advantage of any subsisting substantial degree of market power | 497-504 | [1914] to [1946] |

| PART 32 | An analysis of the value of the bids for the Millmerran and Tarong Contracts and aspects of the chronology of the bidding; Aspects of the events leading up to execution of the Millmerran Contract Aspects of the events leading up to execution of the Tarong Contract | 504-518 | [1947] to [2002] |

| PART 33 | The evidence of Mr Philippe Arto; The consideration of Mr Arto’s affidavit evidence and his oral evidence | 518-579 | [2003] to [2248] |

| PART 34 | The assessment of Mr Arto’s evidence | 579-593 | [2249] to [2303] |

| PART 35 | The evidence of Mr Maycock | 593-626 | [2304] to [2397] |

| PART 36 | The assessment of Mr Maycock’s evidence | 626-632 | [2398] to [2416] |

| PART 37 | Entry into the Amended Millmerran Contract; The relevant events; A consideration of the evidence of Mr Clarke, Mr Zeitlyn and Ms Collins; Market power at June 2004; Findings | 633-722 | [2417] to [2694] |

| PART 38 | The second election to proceed at Millmerran and issues in relation to Tarong and Tarong North; The factual matters; Assessment of the evidence and the documents; Assessment of the evidence of Mr White; The Commission’s contentions in relation to the second election to proceed | 722-776 | [2695] to [2863] |

| PART 39 | The installation of a classifier at Tarong North and further aspects of the evidence of Mr White | 776-810 | [2864] to [2951] |

| PART 40 | The Jones v Dunkel principles to be applied both generally and in relation to specific aspects relating to Part 38 and otherwise | 810-814 | [2952] to 2964] |

| PART 41 | Conclusions in relation to the second election to proceed at Millmerran | 814-824 | [2965] to [2997] |

| PART 42 | The organising principles in relation to s 45 | 824-831 | [2998] to [2016] |

| PART 43 | Section 45 and the inclusions of the provisions in the Original Millmerran Contract; An assessment of the events giving rise to the inclusion of the particular provisions in issue; Consideration of aspects of Professor Hay’s evidence concerning the effect or likely effect of entry into the contract containing the provisions in issue | 831-867 | [3017] to [3069] |

| PART 44 | Conclusions as to s 45 in relation to purpose of the Millmerran provisions | 867-875 | [3070] to [3088] |

| PART 45 | Section 45 and entry into the Tarong Contract of 26 February 2003; An assessment of the events giving rise to the inclusion of the particular provisions in issue | 875-889 | [3089] to [3136] |

| PART 46 | Conclusions in relation to s 45, on purpose concerning the Fly Ash Agreement of 26 February 2003 between Pozzolanic and TEC | 889-895 | [3137] to [3154] |

| PART 47 | Conclusions in relation to s 45, as to effects and likely effects, concerning the Pozzolanic and TEC Agreement of 26 February 2003 | 895-904 | [3155] to [3183] |

| PART 48 | Further Millmerran events | 904-913 | [3184] to [3214] |

| PART 49 | Swanbank considerations | 913-917 | [3215] to [3230] |

| PART 50 | The ultimate conclusions | 918-929 | [3231] to [3277] |

1.2 The facts and contentions as pleaded by the Commission

1.2.1 Flyash, products and markets

1.2.1.01 Flyash

14 Flyash is a fine powder formed from the mineral matter in coal and is a by-product of the combustion of black coal.

15 Flyash is defined by an Australian Standard 3582.1-1998 (“AS 3582.1”) as the “solid material extracted from the flue gases of a boiler fired with pulverised coal” and does not include ash that drops to the bottom of the boiler (“bottom ash”). Flyash is produced by coal-fired electricity generating power stations combusting pulverised coal (to create steam to drive turbines that generate electricity). It consists of particles that are generally less than 100 microns in size. When of suitable quality, flyash is able to be used as a partial substitute for cement in the making of concrete.

1.2.1.02 Fineness

16 AS 3582.1 defines the “fineness” of flyash as the percentage by mass of flyash passing through a 45 micron sieve. AS 3582.1 provides for four grades of flyash suitable for use as cementitious material in concrete and mortar. Those grades are Fine Grade flyash in which a minimum of 75% by mass of the flyash particles pass a 45 micron sieve; Medium Grade having a fineness of 65%-75% so passing; Coarse Grade having a fineness of 55%-65% so passing and Special Grade having a minimum fineness of 75% and a particular “relative strength” quality. Each of these grades of fineness, under the Standard, possess qualities other than the degree of fineness.

17 Flyash that meets the requirements of AS 3582.1 (particularly as either Fine, Medium or Coarse Grade flyash) is “concrete-grade flyash” (para 27). Fine grade flyash is flyash that possesses 75% fineness as a minimum degree of fineness (para 27A).

1.2.1.03 Collection

18 The combustion of coal at a coal-fired power station liberates exhaust gases (flue gas) in which flyash particles are suspended. The flue gas passes through devices, either electrostatic precipitators or fabric filters (baghouses) or a combination of both, which separate particulate matter including flyash from the exhaust gas stream. The separated flyash is collected in hoppers. If not removed from the hoppers (by transfer to sale or storage), it must be disposed of as waste material.

19 Flyash collected in hoppers is “unprocessed flyash” although in its unprocessed state so collected, the particle size may be such that some of it is “concrete-grade flyash” (ie, within one of the grades within AS 3582.1) “and, or alternatively, fine grade fly ash” (paras 28, 29). Throughout the pleading, the Commission asserts the existence of a product (apart from unprocessed flyash) described as concrete-grade flyash or alternatively a separate product described as fine grade flyash. For ease of reference, I will sometimes describe concrete-grade flyash as “cgfa” and fine grade flyash as “fgfa”.

1.2.1.04 Classification

20 Plant or equipment used to separate flyash particles into flyash of higher levels of fineness (then called “processed flyash”), as distinct from unprocessed flyash as collected in hoppers, is called a “classifier”. Unprocessed flyash that is not cgfa (or alternatively fgfa) but which is suitable for processing in a classifier, can be processed to produce cgfa or fgfa.

1.2.1.05 Sources

21 As to the unprocessed flyash market, flyash is produced at four power stations all located in a geographic area called south-east Queensland: Swanbank which has operated since the 1960s and is immediately proximate to Brisbane (near Ipswich); Tarong which has produced flyash since 1984 and is located 180 kilometres north-west of Brisbane; Millmerran which has produced flyash since 2002 and is located 206 kilometres west of Brisbane; and Tarong North which has produced flyash since 2003 and is located adjacent to the Tarong Power Station. These distances seem to be the expression of “direct line” distances.

1.2.1.06 SEQ region and an unprocessed flyash market

22 The Commission pleads that at all material times there has been demand, by suppliers of concrete-grade flyash (or fine grade flyash) operating in south-east Queensland and areas of north-east New South Wales adjacent to the Queensland border (an area described as “the SEQ region”), for the acquisition (and corresponding supply) of unprocessed flyash so as to produce concrete-grade flyash or fine grade flyash (para 34). By reason of the geographic distances and transport costs involved, unprocessed flyash produced or supplied in places outside the SEQ region was not, in the period of the conduct in question, economically substitutable for unprocessed flyash produced or supplied in the SEQ region (para 35).

23 There was, in the period of the conduct in question, a market for the supply and acquisition of unprocessed flyash in the SEQ region, described as the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market (para 36).

1.2.1.07 Functional partial substitutes

24 Concrete-grade flyash (or alternatively fgfa) may replace between approximately 20% to 30% of cement by weight in the manufacture of concrete but is not otherwise a substitute for cement in producing concrete. Although ground granulated blast furnace slag (“slag”) is a functional substitute for cgfa (or alternatively fgfa), its availability in Queensland in the relevant conduct period, was too limited to be an economic substitute for either version of the product. In the relevant conduct period, there was demand in the SEQ region for the supply of cgfa or fgfa to customers who used cgfa (or fgfa) in the production of pre-mix concrete and concrete products (“concrete producers”) and to on-sellers or intermediaries re-supplying either cgfa or fgfa (para 40). In the relevant conduct period, by reason of the geographic distances and transport costs involved, cgfa produced or supplied in places other than the SEQ region was not an economic substitute for cgfa produced or supplied in the SEQ region. Alternatively, as to fgfa, the same proposition prevailed (para 43).

1.2.1.08 The SEQ cgfa market or SEQ fgfa market

25 In the relevant conduct period there was a market for the supply of cgfa in the SEQ region described as the SEQ Concrete-grade Flyash Market (“SEQ cgfa market”) or alternatively a market for the supply of fgfa described as the SEQ Fine Grade Flyash Market (“SEQ fgfa market”).

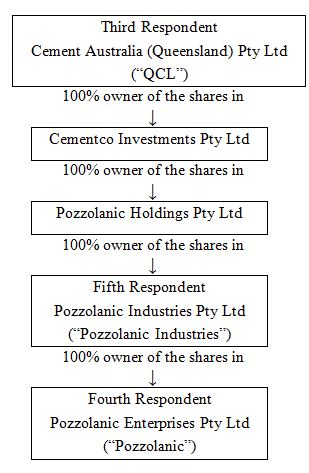

1.2.2 The share ownership structure of some of the respondents up to 30 May 2003

26 Until 30 May 2003, the issued share ownership structure of some of the respondent corporations (all trading corporations) was this:

27 Although not expressly pleaded, QCL was ultimately owned and controlled by an entity described as Holcim Ltd, a multi-national cement company and the interests described at [26] represent the Holcim interests as at 30 May 2003.

28 Until 30 May 2003, QCL engaged in the business of supplying cgfa in the SEQ cgfa market (or supplying fgfa in the SEQ fgfa market). It also supplied cement to customers in the SEQ region; had an established customer base for cgfa (or fgfa) and cement; was the supplier of cgfa (or fgfa) to all major customers in the SEQ cgfa market (or the SEQ fgfa market); was the only supplier in those markets of cgfa (or fgfa) sourced from power stations in the SEQ region; supplied cgfa (or fgfa) on only a delivered basis for a product price per tonne including delivery; and offered volume discounts for combined purchases of cement and cgfa (or fgfa).

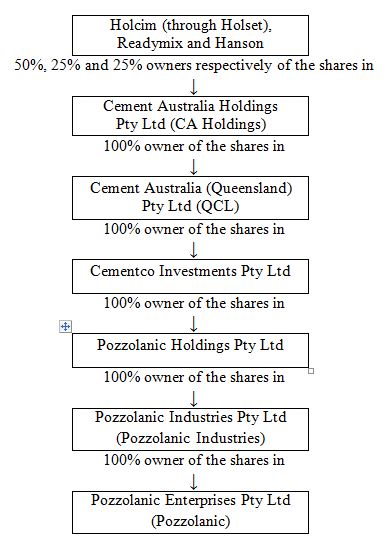

29 From 31 May 2003, a particular set of arrangements, documented by a suite of agreements, was put in place between the Holcim partners (and the entities in that ownership chain) and entities described for present purposes as the Readymix partner (Rinker) and entities described as the Hanson partner (Hanson), which had the result that 100% of the shares in QCL would be held by an entity called Cement Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (the second respondent, formerly known as Australian Cement Holdings Pty Ltd) and the shares in that entity would be held by the Holcim, Readymix and Hanson interests 50%, 25% and 25% respectively. These pleaded arrangements, to be further mentioned shortly, concern the conduct allegations in the period after about 1 June 2003.

1.2.3 The first contended conduct contravention of entry into the Original Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002 and related contextual circumstances

30 In the period up to the signing of (ie. entry into) the Original Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002 by Pozzolanic as buyer, by its holding company Pozzolanic Industries as guarantor, and by Millmerran Power Partners (“MPP”) for the power station (the first contended conduct contravention), Pozzolanic had entered into contracts, arrangements or understandings for the acquisition from power stations in the SEQ region of cgfa (or fgfa) produced “directly” by those power stations, or by Pozzolanic “through classification of unprocessed flyash” produced by those power stations. Pozzolanic supplied cgfa (or fgfa) in the SEQ cgfa market (or the alternative SEQ fgfa market) to QCL or to the customers of QCL (and continued to do so until about 1 June 2003) (para 47).

1.2.3.01 Swanbank

31 As to Swanbank (as one of those sources in the period, for the moment, up to 30 September 2002), Pozzolanic in 1993 entered into a contract with the owner for the purchase and removal of flyash from Swanbank for a five year period commencing on 1 January 1994 which was extended on 30 September 1998 for four years from 1 January 1999 to 31 December 2002, and otherwise varied. Under the 1998 variation, Pozzolanic had the first option to purchase and remove flyash from Swanbank; the owner would not supply third parties but would refer third party requests to Pozzolanic; Pozzolanic would not unreasonably refuse to supply third parties subject to an “adverse affect” test (upon Pozzolanic) and Pozzolanic would have an option to extend the contract from 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2004 should it purchase at least 48,000 tonnes of flyash over 12 consecutive months during the period 1 January 1999 to 31 December 2002. On 11 July 2002, Pozzolanic exercised the option to extend the contract to 31 December 2004 (paras 63 to 68).

1.2.3.02 Tarong

32 As to Tarong, as the other of those SEQ regional sources up to 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic had acquired unprocessed flyash on a first rights basis under a contract with the owner dated 6 December 2000 and had installed, on site, a classifier, storage silos, weighbridge and other infrastructure necessary to process and take flyash (para 82).

33 By 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic and the owner of Tarong had been, since at least May 2002, engaged in a process of drafting a contract ultimately signed by the parties on 26 February 2003 giving Pozzolanic the right to acquire from Tarong all concrete-grade flyash extracted by Pozzolanic from Tarong on particular royalty terms adopting a payment structure that gave volume discounts to Pozzolanic for taking larger volumes of flyash from Tarong (paras 74.3.1, 83 and 84). By 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic and QCL “knew that Pozzolanic was likely to conclude a contract with [Tarong] giving Pozzolanic the rights to acquire flyash from [Tarong]” (para 74.3.2) [emphasis added] and “knew that it was likely that any contract … giving Pozzolanic the rights to access flyash from [Tarong] would include [the royalty payment structure]” (para 74.3.3) [emphasis added]. By 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic and QCL intended Tarong to be their principal source of cgfa (or fgfa) and were pursuing a contract with Millmerran, in addition to, and not as an alternative to, Tarong (para 74.3.4).

34 Between 2001 and 30 September 2002 (as to that part of the conduct period relevant to the contended first conduct contravention) Pozzolanic had the benefit of supply contracts for unprocessed flyash from Swanbank (extended on 11 July 2002 to 31 December 2004) and Tarong (together with an engaged process of drafting a new contract for a further five years) under which Pozzolanic was entitled to acquire “all or virtually all of the concrete-grade flyash [or fgfa] that was available in the SEQ region” (para 48).

35 Between early 2002 and 30 September 2002 (focusing for the moment on the period in 2002 up to 30 September 2002 within the pleaded period of 2002 to 2006) small quantities of cgfa (or fgfa) were acquired from Bayswater Power Station in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales and transported by road for use in the SEQ region (para 42.1). Between 2001 and 30 September 2002 (again focusing on the first conduct period), no person other than Pozzolanic had a contract to acquire unprocessed flyash from Swanbank or Tarong (para 49).

1.2.3.03 Factors confronting an entrant

36 In the period up to 30 September 2002 (and thereafter as pleaded), a person seeking to carry on business as a supplier of cgfa (or fgfa) required an agreement with a power station operator for ongoing and consistent access to unprocessed flyash; investment in very particular plant and equipment at, or proximate to, a power station; substantial capital investment in a classifier, where unprocessed flyash required processing; alternatively, supply of cgfa from an on-seller intermediary; supply agreements with buyers (concrete producers); and, a logistics and distribution network if supply was to be on a delivered basis (paras 45 and 45A). In this period (and up to 31 December 2006), operators of power stations in the SEQ region preferred to have a single entity engaging in on-site classification of flyash at their power station (para 46).

1.2.3.04 Pozzolanic and QCL’s distribution and storage system

37 Up to June 2003 (and thus up to 30 September 2002), Pozzolanic and QCL operated a “distribution and storage system” for cgfa (or fgfa) which maximised the amount of flyash potentially available to Pozzolanic at Swanbank and Tarong. That system took account of production variables at power stations (such as unit operation levels, generating loads and coal source); Pozzolanic and QCL’s established common distribution and logistics network to supply cement and cgfa (or fgfa) on a delivered basis to end-users at concrete batching plants; the use of pneumatic pressurized tankers capable of delivering either cement or cgfa (or fgfa) although not mixed; daily collection and delivery to customers thus minimizing the use of intermediate storage capacity; the absence of any adaptable rival distribution network; Pozzolanic’s “exclusive or first rights [in effect]” to its daily requirements of unprocessed flyash at each power station; and Pozzolanic’s limited additional investment in on-site and off-site storage capacity at or near power stations (para 56).

38 By reason of this distribution and storage system operated by Pozzolanic together with QCL, Pozzolanic’s actual daily requirements for unprocessed flyash were potentially significantly higher than its average daily needs, calculated over a year, for unprocessed flyash and the amount of remaining unprocessed flyash potentially available from the power station to an alternative purchaser could vary substantially from day to day.

1.2.3.05 Other high barriers to entry

39 Up to 30 September 2002 (and pleaded as enduring factors to December 2006), apart from incumbency and the features of Pozzolanic and QCL’s distribution and storage system, there were high barriers to entry into the SEQ cgfa market (or the fgfa market) due, first, to Pozzolanic’s contracts with power stations; second, Pozzolanic’s capacity to produce “substantially more [cgfa], or alternatively, [fgfa] than demand in the SEQ region”; third, the substantially large volumes of unprocessed flyash in excess of that required to meet the demand for cgfa (or fgfa); and, fourth, the high costs of transporting cgfa (or fgfa) from locations outside the SEQ region into the SEQ region (paras 51, 52, 58.1 to 58.4).

40 Up to June 2003 (and thus up to 30 September 2002), QCL faced only limited competition in the supply of cgfa (or fgfa) in the SEQ region. It was the only supplier in the SEQ region of cgfa (or fgfa) sourced from power stations in the SEQ region. It was able to sell cgfa (or fgfa) at “prices largely free from the constraint of competition” in the supply of such products (paras 59.1, 59.2 and 59.3). In this period, QCL faced less commercial risk than its potential competitors of being unable to sell cgfa (or fgfa) it acquired (through its ultimately 100% owned subsidiary, Pozzolanic) from power stations in the SEQ region (para 59.4). By reason of these matters (at paras 59.1 to 59.4), QCL “was commercially able to fund its 100% owned subsidiary Pozzolanic to offer higher prices to power stations in the SEQ region for unprocessed flyash than any competitor or potential competitor of Pozzolanic for such acquisition” (para 59.5).

1.2.3.06 QCL’s substantial degree of market power

41 By reason of the wholly owned status of Pozzolanic; and the requirements a person wishing to carry on business as a supplier of cgfa (or fgfa) would need to meet described at [36]; and the preference of power station operators to have a single on-site entity carrying on classification activity; and the factors described at [30] to [40], QCL in the period up to June 2003 (and thus in the period up to 30 September 2002), had a substantial degree of power in the SEQ Concrete-grade Flyash Market or, alternatively, the SEQ Fine Grade Flyash Market (paras 62.1, 9, 45 to 53, 56 to 59). So too did Pozzolanic by operation of s 46(2) of the Act (para 62.1).

1.2.3.07 The relevant provisions of the Original Millmerran Contract

42 On 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic, Pozzolanic Industries and MPP entered into the Original Millmerran Contract allowing Pozzolanic to take flyash from Millmerran. The particular terms of relevance identified by the Commission are these.

70.1 pursuant to clause 10.1, the contract had a term of seven years from 30 September 2002;

70.2 pursuant to clauses 6.1, 6.2 and 7, Pozzolanic would pay MPP a minimum of $1,323,500 per annum indexed to CPI (“guaranteed minimum payment”);

70.3 pursuant to clause 5.1, MPP was obliged to make available to Pozzolanic a minimum of 135,000 tonnes of concrete-grade flyash per annum (“guaranteed minimum quantity”);

70.4 pursuant to clause 6.3, Pozzolanic would pay MPP $10.10 per tonne for every tonne of concrete-grade flyash it took in excess of 135,000 tonnes;

70.5 pursuant to clause 2.1, Pozzolanic was obliged to undertake testing of the quality of flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station;

70.6 pursuant to clause 2.1, Pozzolanic was obliged to determine whether flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station met the requirements of AS 3582.1 for concrete-grade flyash and met the “Fly Ash Critical Limits” defined in Schedule 2 of the contract (“Acceptable Range”);

70.7 pursuant to clause 2.2, Pozzolanic was obliged to notify MPP within a certain period of time as to whether flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station met the requirements of Acceptable Range;

70.8 pursuant to clause 2.3, if Pozzolanic notified MPP that flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station did not meet the requirements of Acceptable Range, MPP was entitled to have the flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station independently tested to determine whether it met the requirements of Acceptable Range;

70.9 pursuant to clause 2.6, if MPP accepted Pozzolanic’s determination that flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station did not meet the requirements of Acceptable Range or independent verification demonstrated that flyash produced by Millmerran Power Station did not meet the requirements of Acceptable Range, either party was entitled to terminate the contract within 14 days of the acceptance of the determination or independent verification;

70.10 subject to the determination that the flyash met the requirements of Acceptable Range, pursuant to clause 3, Pozzolanic was obliged to construct facilities capable of enabling it to take delivery of flyash (“flyash facilities”) at Millmerran Power Station that would be ready for operation by 1 May 2004 in performance of the contract;

70.11 pursuant to clause 40.12(b), Pozzolanic had the right to assign its rights under the contract with the written consent of MPP, which could not be unreasonably withheld;

70.12 pursuant to clause 26.4, Pozzolanic could terminate the contract after 31 December 2006 upon 60 days notice and payment of a termination payment;

70.13 pursuant to clause 35.1, Pozzolanic Industries was the guarantor of Pozzolanic.

43 By reason of a particular arrangement, Pozzolanic effectively increased, in October 2002, its monthly payments to Millmerran by $900,000 over 72 months ($12,500 per month) for the purposes of the Agreement (para 71).

1.2.3.08 QCL’s causative and controlling conduct

44 Pozzolanic’s entry into the Original Millmerran Contract was caused by QCL, as QCL funded the cost of entry, and managed and controlled Pozzolanic (para 72).

1.2.3.09 The substantial purposes for Pozzolanic’s entry and QCL causing Pozzolanic’s entry into the Original Millmerran Contract

45 A substantial purpose of Pozzolanic in entering into the contract, and of QCL in causing Pozzolanic to enter, was: (a) to prevent any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from Millmerran; (b) to prevent any person entering into the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market as an acquirer of unprocessed flyash; (c) to deter or prevent persons from engaging in competitive conduct in the SEQ unprocessed flyash market; (d) to prevent any other person from supplying cgfa in the SEQ cgfa market (or, alternatively, supplying fgfa into the SEQ fgfa market); (e) to prevent any person entering into the SEQ cgfa market (or, alternatively, the SEQ fgfa market); and, (f) to deter or prevent persons from engaging in competitive conduct in the SEQ cgfa market (or the SEQ fgfa market) (para 73).

46 The Commission pleads that on 30 September 2002, Pozzolanic did not need flyash from Millmerran to meet the demand of QCL’s actual or potential customers (para 74.1) for cgfa or fgfa. Also, at 30 September 2002, the supply of unprocessed flyash available to Pozzolanic from other SEQ region power stations (Swanbank and Tarong) and the volume of cgfa (or fgfa) that “could potentially be generated from that supply”, each year, substantially exceeded the demand for cgfa from customers in the SEQ cgfa market (or fgfa in the SEQ fgfa market) as at 30 September 2002, and substantially exceeded the forecast demand during the term of the Millmerran Contract (para 74.2).

47 At 30 September 2002, “Pozzolanic and QCL” did not wish to use, and had no commercial reason to use, flyash obtained from Millmerran in preference to Tarong flyash, for these reasons: first, Pozzolanic and Tarong had been in a state of negotiation since at least May 2002 for a contract giving Pozzolanic the rights to acquire flyash from Tarong; second, Pozzolanic and QCL “knew that Pozzolanic was likely to conclude a contract with [Tarong] giving Pozzolanic [those rights]”; third, Pozzolanic and QCL knew that it was likely that any such contract would include a royalty payment structure that gave volume discounts to Pozzolanic for taking larger volumes of flyash from Tarong; and, fourth, Pozzolanic and QCL intended Tarong to be their principal source of cgfa or fgfa and “were pursuing the [Millmerran] contract in addition to, and not as an alternative to, the [Tarong] contract”.

48 At 30 September 2002, neither QCL nor Pozzolanic had identified any demand (actual or potential) for cgfa in the SEQ cgfa market (or fgfa in the SEQ fgfa market) that QCL was not able to supply sourced from Swanbank or Tarong (para 74.4). Neither company had identified “any commercial need” for entering into the Millmerran Contract (para 74.5), and QCL “would not have caused, and would not have had any commercial reason to cause” Pozzolanic to enter into the contract if QCL did not have a substantial degree of power in the SEQ cgfa market (or the SEQ fgfa market) (para 74.6).

1.2.3.10 QCL takes advantage of its substantial degree of market power

49 The conclusionary assertion at para 75 is that by causing Pozzolanic to enter into the Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002, QCL took advantage of its substantial degree of power in the SEQ cgfa market (or, alternatively, the SEQ fgfa market), for the pleaded proscribed purposes at [45].

1.2.3.11 The identified provisions and the “substantial purposes” of “those provisions”

50 Apart from the contended s 46 contravention by QCL, by causing Pozzolanic to enter into the Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002, the Commission identifies eight clauses of the Millmerran Contract (clauses 10.1, 6.1, 6.2, 7, 5.1, 6.3, 3 and 26.4, that is, those clauses pleaded at 70.1, 70.2, 70.3, 70.4, 70.10 and 70.12 and recited (among others) at [42]) which have, as a substantial purpose, first, the purpose of preventing any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from Millmerran; second, the purpose of hindering or preventing any other person from supplying cgfa in the SEQ cgfa market (or its alternative product in the alternative product market); third, the purpose of substantially lessening, hindering or preventing competition in the SEQ unprocessed flyash market; and fourth, the purpose of substantially lessening, hindering or preventing competition in the SEQ cgfa market (or the alternative SEQ fgfa market) (para 77).

51 The first of these substantial purposes (of preventing the acquisition of unprocessed flyash) is said to be grounded upon the factors of: (a) depriving a potential entrant into the cgfa market of an agreement for ongoing access to unprocessed flyash for classification or a market proximate source of ongoing quantities of cgfa from another cgfa supplier (with a corresponding contention in relation to access to unprocessed flyash for classification or a proximate source of fine grade flyash); (b) the likelihood of Millmerran being practically unwilling or unable to enter into an agreement with any other person allowing ongoing access to unprocessed flyash by reason of Pozzolanic’s guaranteed minimum quantity entitlement; (c) piecemeal or irregular supply of unprocessed flyash to another person (seeking to carry on business as a cgfa supplier) would be uncommercial for that other person; (d) Pozzolanic’s ability to terminate the contract on 60 days notice after 31 December 2006 created a “strong incentive for [Millmerran] not to supply flyash to a third party” as that event might give rise to termination (and the end of the minimum royalty payment); and (e) “Pozzolanic and MPP knew of [each of the above matters]” (para 77.15).

52 The second substantial purpose (of preventing others from supplying cgfa or fgfa in the pleaded markets) is also grounded on these same five factors, and also, (f) the unavailability of alternative sources of unprocessed flyash out of Swanbank by reason of Pozzolanic’s extension of the Swanbank contract to 31 December 2004 on 11 July 2002, and (g) “the likely contract between [Tarong] and Pozzolanic” (para 77.2).

53 The third substantial purpose is also grounded upon the five factors at [51].

54 The fourth substantial purpose is grounded upon the five factors at [51] and the two further factors at [52].

1.2.3.12 The effect or likely effect of the identified provisions in the Original Millmerran Contract

55 At para 78, the Commission contends that the effect, or likely effect, of cl 5.1 of the Millmerran Contract (the guaranteed minimum quantity clause of 135,000 tonnes per annum) either on its own or taken together with one or more of the clauses pleaded at para 70 ([42]) was:

78.1 to prevent any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from [Millmerran];

78.2 further or alternatively, to hinder or prevent any other person from supplying concrete-grade flyash in the SEQ Concrete-grade Flyash Market [or fgfa in the SEQ fgfa market];

78.3 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market;

78.4 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ Concrete-grade Flyash Market [or fgfa in the SEQ fgfa market].

56 The first effect or likely effect is said to be grounded upon the outworking of the first three factors described at [51]. The second effect or likely effect is said to be grounded upon those three factors plus factors (f) and (g) described at [52]. The third effect or likely effect is based upon the first three factors described at [51] and the fourth effect or likely effect is based upon the first three factors at [51] and factors (f) and (g) described at [52].

1.2.3.13 QCL “gives effect” to the identified provisions

57 The Commission contends that by funding Pozzolanic’s entry into the Millmerran Contract on 30 September 2002, QCL gave effect to the provisions of that contract at clauses 10.1, 6.1, 6.2, 7, 5.1, 6.3, 3 and 26.4 (being those pleaded at 70.1, 70.2, 70.3, 70.4, 70.10 and 70.12) where those provisions had the pleaded purposes ([50] to [54]), and by themselves or together with one or more of the provisions of the contract pleaded in para 70, had the effect or likely effect set out at [55] and [56].

1.2.3.14 Pozzolanic “gives effect” to provisions of the Original Millmerran Contract

58 The Commission also contends that in the period 30 September 2002 until July 2004, by not taking any Millmerran flyash for commercial use (or installing facilities) and by making the annual guaranteed minimum payments of $1,323,500 (indexed to CPI), Pozzolanic gave effect to “provisions of the Original Millmerran Contract” (paras 79, 156.4).

1.2.3.15 The alternative s 47 point

59 The Commission also contends, in the alternative to the purpose and effect or likely effect contentions, that, by entering into the Millmerran Contract (and varying the price terms and making the annual guaranteed minimum payment of $1,323,500) for the purposes earlier described, or alternatively, having the effect or likely effects earlier described, Pozzolanic “offered to acquire unprocessed flyash from Millmerran power station from MPP at a particular price, on the condition that MPP not supply unprocessed flyash from Millmerran power station to another person” (para 81) [emphasis added].

1.2.3.16 The first conduct contraventions summarised by reference to paras 156, 155 and 157

60 As to the first conduct contravention relating to entry into the Millmerran Contract (and the identified provisions) the Commission says this.

61 First, Pozzolanic contravened s 46 of the Act by entering into the Millmerran Contract.

62 Second, in the alternative to that proposition, Pozzolanic was “knowingly concerned” in, or party to, and aided, abetted, counselled or procured (which I will describe simply as “in the relevant statutory sense”), QCL’s contravention of s 46, as pleaded, by reason of the conduct described at [41] to [49].

63 Third, Pozzolanic contravened s 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by entering into the Millmerran Contract having regard to the identified provisions at [50] (and [42]) where those provisions had the substantial purposes described at [50], based on the factors described at [51] to [54], and where, the contract contained cl 5.1 (in the context of any one or all of the para 70 clauses ([42])) and the effect or likely effect of those provisions was that described at [55] and [56].

64 Fourth, Pozzolanic contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) by giving effect to provisions of the Millmerran Contract by the conduct described at [58].

65 Fifth, in the alternative to the third and fourth propositions, Pozzolanic contravened s 47 by reason of the conduct said to give rise to those earlier contraventions (and having regard to [59]).

66 Sixth, QCL contravened s 46 by causing Pozzolanic to enter into the Millmerran Contract (having regard to the factors described at [41] to [49]).

67 Seventh, in the alternative to the sixth proposition, QCL was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contravention of s 46 (as earlier described at [42] to [48]).

68 Eighth, QCL was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act or, alternatively, Pozzolanic’s contravention of s 47 of the Act as earlier described.

69 Ninth, QCL contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) by giving effect to the provisions of the Millmerran Contract (at paras 70.1, 70.2, 70.3, 70.4, 70.10 and 70.12) by reason of the conduct of funding Pozzolanic’s entry into the contract in circumstances where the provisions had the purpose, effect or likely effect as described at [50] to [56], or, in the alternative, was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii), by reason of the conduct described at [58] or, alternatively, s 47 by reason of the conduct described at [59].

70 Tenth, Pozzolanic Industries was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contraventions of s 46 or, alternatively, QCL’s contraventions of s 46 as described at [62].

71 Eleventh, in the alternative to the tenth proposition, Pozzolanic Industries was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contraventions of s 47 as earlier described at [59].

1.2.4 The second contended conduct contravention relating to entry into the Tarong Contract on 26 February 2003

72 The Commission’s general alternative contention throughout as to a separate product described as fgfa and a separate market described as the SEQ fgfa market is now readily apparent. In the course of describing the remaining contended conduct contraventions, I will not necessarily repeat each contention framed in the alternative way by reference to fgfa and the SEQ fgfa market. The Commission puts its case throughout, on that alternative basis. The respondents take issue with such an approach both on the facts and as a question of method.

1.2.4.01 The Tarong Contract

73 On 26 February 2003, Pozzolanic and Tarong’s owner, Tarong Energy Corporation (“TEC”), entered into a contract (the “Tarong Contract”) allowing Pozzolanic to take flyash from Tarong Power Station for five years from 1 March 2003 (cl 2). TEC agreed to sell and Pozzolanic agreed to buy “all concrete-grade flyash extracted by Pozzolanic from the Tarong Power Station” (cl 3.1). Pozzolanic would pay annual amounts (indexed to CPI) which decreased according to increases in the volume of flyash removed commencing at $2.6M per annum if less than 50,000 tonnes of flyash was removed and decreasing to $2.1M per annum if 450,000 tonnes or more of flyash was removed each year (cl 12). Under the contract, Pozzolanic would also be entitled to take flyash produced by Tarong North Power Station (adjacent to Tarong) on this basis: as soon as possible after 1 March 2003 Pozzolanic was to determine whether Tarong North flyash was “suitable for use [with] portland cement” (cl 4.4); if it was, Pozzolanic would be required to install a classifier (cl 4.4); if not suitable, or if no classifier was installed, that circumstance would not give rise to any right to a reduction in the amount payable to TEC for Tarong flyash (cl 8.3); the owner would approve a point at Tarong North for Pozzolanic to take possession of flyash (cl 4.4); and, by reference to the definitions of “Ash Disposal System” and “Ash Transfer Points”, the owner agreed to sell, and Pozzolanic agreed to buy, all concrete-grade flyash extracted by Pozzolanic at Tarong North (cls 3.1 and 1.1): para 84.

74 Pozzolanic had the right to terminate the contract on giving 12 months notice to TEC after September 2004 (cl 17.1): para 84.6.

1.2.4.02 Other SEQ region power stations

75 By 26 February 2003, Pozzolanic had entered into the Original Millmerran Contract. It had also extended the Swanbank Contract until 31 December 2004. No other power station in the SEQ unprocessed flyash market was supplying or willing to supply unprocessed flyash to any person other than Pozzolanic: para 85.

1.2.4.03 The substantial purpose of the identified provisions

76 A substantial purpose of cls 2, 3.1, 12 and 17.1 (para 86) of the Tarong Contract was:

86.1 to prevent any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from [Tarong Power Station]

86.2 to hinder or prevent any other person from supplying concrete-grade flyash in the SEQ [cgfa market]

86.3 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market

86.4 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ [cgfa market]

77 The first substantial purpose is said to be grounded upon the factors of: (a) depriving a potential entrant into the cgfa market of an agreement for ongoing access to unprocessed flyash for classification or a proximate source of ongoing quantities of cgfa from another supplier of cgfa; (b) the likelihood that TEC would be practically unwilling or unable to enter into an agreement with any other person allowing ongoing access to unprocessed flyash by reason of the requirement to sell to Pozzolanic all cgfa that Pozzolanic could extract; (c) piecemeal or irregular supply of unprocessed flyash from Tarong to another person seeking to carry on business as a cgfa supplier would be uncommercial for that other person; (d) Pozzolanic’s ability to terminate the Tarong Contract on 12 months notice after September 2004 operated as a strong incentive for TEC not to supply flyash to a third party; and, (e) Pozzolanic and TEC knew each of the above four matters.

78 The second substantial purpose is also grounded upon the five factors at [77] and also, (f), the unavailability of alternative sources of unprocessed flyash as a consequence of the extension of the Swanbank Contract and Arrangements on 11 July 2002 to 31 December 2004; the Original Millmerran Contract of 30 September 2002; and the Tarong Contract of 26 February 2003.

79 The third substantial purpose is also grounded upon the five factors at [77]. The fourth substantial purpose is grounded upon the five factors at [77] and the further factor (f) described at [78].

1.2.4.04 The effect or likely effect

80 The effect, or likely effect, of cls 2, 3.1, 12 and 17.1 either by themselves or together with (or alternatively to) one or more of the other provisions of the Tarong Contract pleaded at para 84 ([73] and [74]) (the other pleaded provisions being cls 4.4, 8.3 and 1.1), or together with (or alternatively to) one or more of the provisions of the Swanbank Contract as extended to 31 December 2004, and one or more provisions of the Original Millmerran Contract (pleaded at para 70 and set out at [42]) was:

87.4 to prevent any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from [Tarong Power Station]

87.5 [to] hinder or prevent any other person from supplying concrete-grade flyash in the SEQ [Concrete-grade Flyash Market]

87.6 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market

87.7 [to] substantially lessen, hinder or prevent competition in the SEQ Concrete-grade Flyash Market

81 Like the earlier formulations, the first effect or likely effect is said to be grounded upon the factors of: (a) depriving a potential entrant into the cgfa market of an agreement for ongoing access to unprocessed flyash for classification or a (market) proximate source of ongoing quantities of cgfa from another supplier of cgfa (with the corresponding fgfa contention) having regard to the para 45 factors (described at [36]): para 87.4.1; (b) the likelihood, having regard to the preference of power station operators in South East Queensland from 2002 to December 2006 to have a single entity undertaking on-site classification (para 46) and Pozzolanic’s distribution and storage system (paras 56 and 57), that TEC would be practically unable or unwilling to enter into an agreement with any other person allowing ongoing access to unprocessed flyash by reason of TEC’s requirement to provide Pozzolanic with “the first rights to all unprocessed flyash”: para 87.4.2; and (c) piecemeal or irregular supply of unprocessed flyash from Tarong by TEC to another person seeking to carry on business as a supplier of cgfa or fgfa would be uncommercial for that person: para 87.4.3.

82 The second effect or likely effect is based on the three factors described at [81] and also, (d), the unavailability of alternative sources of unprocessed flyash in the South East Queensland region due to the extension of the Swanbank Contract on 11 July 2002 to 31 December 2004 and the Original Millmerran Contract of 30 September 2002: paras 87.5.1, 87.5.2.

83 The third effect or likely effect is based on the factors described at [81]: para 87.6.

84 The fourth effect or likely effect is based on the factors described at [81] and the further factor (d) described at [82]: para 87.7.

1.2.4.05 QCL funds entry and performance by Pozzolanic

85 From March 2003, Pozzolanic acquired flyash from Tarong under the terms of the Tarong Contract. The Commission pleads that QCL, by funding Pozzolanic’s entry into the Tarong Contract, gave effect to cls 2, 3.1, 12 and 17.1, where those clauses had the substantial purposes described at [76] by reference to the factors described at [77] to [79] and had, by themselves, or together with one or more of cls 4.4, 8.3 and 1.1, the effect or likely effect described at [80] by reference to the factors at [81] to [84]: para 89.

86 The Commission also contends by its pleading that QCL (up to June 2003), by funding Pozzolanic’s performance of the Tarong Contract, gave effect to cls 2, 3.1, 12 and 17.1 in circumstances where the clauses had the purposes or had the effect or likely effect as described: para 90.

1.2.4.06 The s 47 point

87 In the alternative to the substantial purposes, effects or likely effects case, the Commission contends that Pozzolanic’s conduct, funded by QCL, of entry into the Tarong Contract on 26 February 2003, on the terms pleaded (cls 2, 3.1, 12, 17.1, 4.4, 8.3 and 1.1), and Pozzolanic’s acquisition of flyash from March 2003 on those terms was conduct which had the same purposes described at [76] based on the factors at [77] to [79] or had the effect or likely effect as described at [80] based on the factors at [81] to [84], and thus involved Pozzolanic acquiring or offering to acquire unprocessed flyash from Tarong (TEC) “at a particular price, on the condition that TEC not supply unprocessed flyash from Tarong Power Station to another person” in contravention of s 47 of the Act [emphasis added].

1.2.4.07 The second conduct contraventions summarised by reference to paras 156, 155 and 154

88 These considerations are said to give rise to a contravention by Pozzolanic first, of s 45(2)(a)(ii) by entry into the Tarong Contract; second, a contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) by giving effect to the provisions of that contract by acquiring flyash from March 2003 under the pleaded terms (cls 2, 3.1, 12, 17, 4.4, 8.3, 1.1); and third, in the alternative to proposition 1 and 2, a contravention of s 47.

89 QCL is said, first, to have been knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) or s 47 by reason of the circumstances earlier described; second, to have contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) by giving effect to the identified provisions by funding Pozzolanic’s entry and subsequent performance of the contract up to 1 June 2003; and third, in the alternative to the second proposition, QCL was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contraventions of s 45(2)(b)(ii) or alternatively s 47.

90 Cement Australia is said to have first, contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) by giving effect to the provisions of the Tarong Contract by the conduct earlier described, second, in the alternative to the first proposition, was knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense of Pozzolanic’s contraventions of s 45(2)(b)(ii), and third, in the alternative to the third proposition, contravened s 47 by being knowingly concerned in the relevant statutory sense in Pozzolanic’s contraventions of s 45(2)(a)(ii).

1.2.5 The Holcim, Readymix Cement and Hanson Australia arrangements

91 On 31 May 2003, a Framework Agreement was entered into between a number of corporations reflecting the interests of Holcim, Readymix Cement and Hanson Australia that provided for the establishment of a partnership between these groups. The partnership would undertake the business of logistics, distribution and sales and marketing for cementitious products. A “Corporate Group” would be established with the second respondent Cement Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (“CA Holdings”) as the holding company. The first respondent, Cement Australia Pty Ltd would manage the day-to-day operations of the partnership and, as agent for the partnership, manage the Corporate Group.

92 On 31 May 2003, a Management Agreement was entered into between 23 companies in the CA Holdings Group of companies (including QCL, Pozzolanic and Pozzolanic Industries) and Cement Australia as agent for the partnership by which Cement Australia was engaged to provide management and consultancy services. On 31 May 2003, Cement Australia (for the partnership) and CA Holdings entered into a Cementitious Products Acquisition Agreement (the “CPA Agreement”) under which Cement Australia, as agent for the partnership, would purchase, and the CA Holdings Group of companies would sell, to Cement Australia all of the cementitious products (including flyash) produced by CA Holdings Group entities.

93 CA Holdings and its related entities would not sell cementitious products to any person other than Cement Australia without Cement Australia’s prior written consent and cementitious products would be supplied at cost plus 10%. The CPA Agreement was varied by a Terms Sheet of 27 September 2005.

94 The Commission contends that from 31 May 2003, Cement Australia managed the day-to-day operations of the CA Holdings Group of companies; Cement Australia and CA Holdings each had the sixth respondent, Mr Christopher Leon, as their Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director; the Board of Directors of Cement Australia was the same Board as the CA Holdings Board; CA Holdings oversaw the operation of Pozzolanic; and from 31 May 2003 Pozzolanic, under the new arrangements, supplied its product to Cement Australia rather than QCL (which, to that date, had been supplied with flyash by Pozzolanic).

1.2.6 The third contended conduct contraventions concerning the Amended Millmerran Contract (ie. the first election to proceed)

1.2.6.01 The variation and the 28 July 2004 letter

95 On 28 July 2004, MPP sent a letter to Pozzolanic and Pozzolanic Industries to evidence an agreement of the parties to amend the Original Millmerran Contract. On a particular date, Ms Sandra Collins on behalf of Pozzolanic and Mr Simon Lennon on behalf of Pozzolanic Industries, signed the 28 July 2004 letter. Pursuant to the 28 July 2004 letter, MPP and Pozzolanic varied the Original Millmerran Contract to provide that Pozzolanic was required to notify MPP by 31 July 2004 whether Millmerran flyash fell within the “Acceptable Range” for cgfa and could be “practically and economically converted” into cgfa (the cl 2.2 variation): para 94.1.

96 The date by which Pozzolanic was required to construct plant, on site, was varied from 1 May 2004 to 1 May 2005 (the cl 3.3 variation): para 94.2.

97 By cl 4, after construction of plant on site, Pozzolanic or MPP would be entitled to terminate the contract having regard to the following conjunction of things: Pozzolanic determines that Millmerran flyash does not meet Acceptable Range limits and cannot be practically and economically converted into cgfa; Pozzolanic gives notice to MPP of that position; MPP accepts that determination (or an independent determination is made to that effect) and, Pozzolanic gives notice of termination within 14 days of MPP’s acceptance. Upon those events, termination would take effect six months after the date of notice with only pro-rata payment of the lump sum payable under the contract to that date (unless termination occurred in 2005): paras 94.3, 94.4.

98 The term of the contract was varied to eight years (cl 42.1) and under cl 26.4, Pozzolanic could terminate the contract on 60 days notice after 13 December 2007 rather than 31 December 2006: paras 94.5 and 94.6.

1.2.6.02 The 30 July 2004 letter

99 On 30 July 2004, Pozzolanic wrote to MPP saying that Millmerran flyash did not meet Acceptable Range limits; Pozzolanic had not determined whether Millmerran flyash could be practically and economically converted into cgfa; Pozzolanic was willing to proceed with the Amended Millmerran Contract as if Millmerran flyash fell within the Acceptable Range limits and proceed as if Millmerran flyash could be practically and economically converted to cgfa.

1.2.6.03 Pozzolanic’s contended waiver

100 Thus, Pozzolanic is said to have waived its right to terminate the Amended Millmerran Contract and became bound to install a classifier at Millmerran by 1 May 2005 and pay $1,323,500 per year (indexed to CPI) until 30 September 2010 subject to these things: if Pozzolanic installed a classifier, made an adverse determination concerning Millmerran flyash, gave Millmerran notice of it, and Millmerran accepted the determination (or an independent determination), and Pozzolanic then gave notice of termination to MPP within time, the contract would terminate six months later with the pro-rata adjustment provision taking effect.

1.2.6.04 The Commission’s pleaded contentions

101 The Commission says this.

102 First, the 30 July 2004 letter, by itself or taken together with the amending of the Millmerran Contract by the 28 July 2004 letter, constituted an election (ie. conduct) by Pozzolanic to proceed with the Amended Millmerran Contract rather than terminate it, para 97.

103 Second, Pozzolanic’s entry into the Amended Millmerran Contract and election to proceed was conduct caused by Cement Australia, as first, Cement Australia was to fund the costs of the Amended Millmerran Contract; second, Pozzolanic would not have incurred the cost of the Amended Millmerran Contract or have elected to go on with it without Cement Australia’s “support and funding”; third, Cement Australia controlled CA Holdings and Pozzolanic; fourth, Cement Australia, through Mr Leon, approved entry into the Amended Millmerran Contract and the election to go on with it; fifth, Pozzolanic entered into the Amended Millmerran Contract “at the direction and with the consent of Leon” (and also Mr Shaun Clarke, Cement Australia’s General Manager, Sales and Distribution); and, sixth, Pozzolanic “was required by Cement Australia” to “secure” Millmerran Power Station (as a source of flyash) (para 98).

104 Third, Cement Australia caused Pozzolanic to enter into the Amended Millmerran Contract and engage in the conduct of electing to go on with it for these substantial purposes:

99.1 preventing any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from [Millmerran];

99.2 preventing the entry of any person into the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market as an acquirer of unprocessed flyash;

99.3 deterring or preventing persons from engaging in competitive conduct in the SEQ Unprocessed Flyash Market;

99.4 preventing any other person from supplying [cgfa] in the [SEQ cgfa market];

99.5 preventing the entry of any person into the [SEQ cgfa market]; and

99.6 deterring or preventing any person from engaging in competitive conduct in the [SEQ cgfa market].

105 Fourth, at 28 July 2004, Cement Australia did not need Millmerran flyash to meet actual or potential demand from customers for cgfa, and the supply (and volume) of unprocessed flyash available to Pozzolanic from SEQ region power stations under contract substantially exceeded the demand for cgfa from customers in the SEQ cgfa market at that date and substantially exceeded the forecast demand for the term of the Amended Millmerran Contract: para 100.2.

106 Fifth, at 28 Jul 2004, neither Cement Australia nor Pozzolanic had identified any demand for cgfa that was not able to be met with cgfa out of Tarong and Swanbank and nor had either company identified any commercial need for making the election to proceed: para 100.3.

107 Sixth, Cement Australia “would not have caused, and would not have had any commercial reason to cause, Pozzolanic to enter into the Amended Millmerran Contract and make the first election to proceed if it did not have a substantial degree of power in the [SEQ cgfa market]” [emphasis added]: para 100.6.

1.2.6.05 Cement Australia “takes advantage”

108 Thus, Cement Australia, it is said, by causing Pozzolanic to enter into the Amended Millmerran Contract and make the first election to proceed with it, took advantage of its substantial degree of market power in the SEQ cgfa market (or the SEQ fgfa market): para 101.

1.2.6.06 The substantial purpose of the identified provisions

109 A substantial purpose of the provisions pleaded in para 70 (see [42]) and cls 2.2, 3.3, 4, 42.1 and 26.4 (the amended provisions, para 94: [95] to [98]), was:

102.1 to prevent any other person from acquiring unprocessed flyash from [Millmerran]