Adidas AG v Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd (No 3) [2013] FCA 905

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| First Applicant ADIDAS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 058 390 659 Second Applicant | |

AND: | PACIFIC BRANDS FOOTWEAR PTY LTD Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT DIRECTS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer for the purposes of agreeing on the appropriate orders to give effect to these reasons and also in relation to costs. In the event that there is no agreement within 28 days the matter will be relisted for short argument on those issues.

2. The parties have leave to contact my associate after 28 days to relist the matter if necessary.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Order 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1368 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | ADIDAS AG First Applicant ADIDAS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 058 390 659 Second Applicant

|

AND: | PACIFIC BRANDS FOOTWEAR PTY LTD Respondent

|

JUDGE: | ROBERTSON J |

DATE: | 12 September 2013 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 These proceedings, which were commenced in October 2010, concern whether or not the respondent has infringed the applicants’ registered trade marks, that is, whether the respondent has used as a trade mark a sign that is deceptively similar to the applicants’ registered trade marks in relation to goods in respect of which the trade marks are registered: see s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act). The goods in question are certain types of shoes. The proceedings do not concern the common law of passing-off or misleading or deceptive conduct under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

2 The first applicant, adidas AG (“adidas”) is the owner of the trade marks. The second applicant, adidas Australia Pty Limited (“adidas Australia”), is a subsidiary of adidas and distributes adidas products in Australia.

3 The respondent, Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd (Pacific Brands), is a company that offers shoes for sale throughout Australia. It sells some 20 million pairs of shoes each year.

4 These reasons deal with infringement and I shall give the parties the opportunity, which they sought, to make further submissions as to the appropriate form of relief in the light of my conclusions.

5 The marks alleged to be infringed are recorded in the register as follows:

Reg. No. | Trade Mark | Registered from | Endorsement | Goods in relation to which mark is registered |

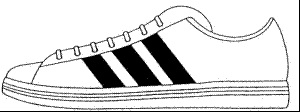

131325 |

| 13 March 1957 | The mark consists of three stripes of a colour different from that of the article of footwear to which they are applied. The three stripes extend across the article from the area of the lacing to the vicinity of the instep, an example of such mark being depicted in the representation of the mark. Evidence that user has rendered the trade mark distinctive of the applicant’s goods has been filed. | Sports shoes, special sports shoes, more particularly football boots, runners, training shoes and other sporting footwear in this class. |

924921 |

| 17 July 2002 | Trade Mark Description: The trademark consists of three stripes forming a contrast to the basic colour of the shoes; the contours of the shoe serves [sic] to show how the trademark is attached and is no component of the trademark. Provisions of subsection 41(5) applied. | Footwear, including sport shoes and casual shoes |

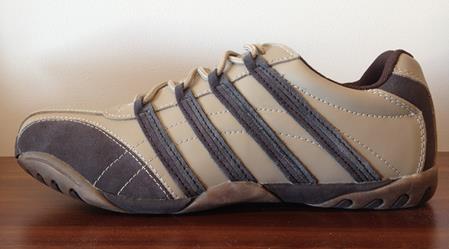

6 There follows a photograph of each of the two adidas shoes tendered.

7 The first was referred to as the Superstar Shoe - Exhibit A1.

The second adidas shoe tendered was referred to as the Copa Mundial - Exhibit B1.

The issues

8 In the originating application dated 18 October 2010, “Infringing Products” was defined as follows:

“Infringing Products” means the articles of footwear depicted in Annexures C to N to the accompanying Statement of Claim and any other articles of footwear to which either of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks or a mark substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, either of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks, has been applied without the licence of the First Applicant. This includes, without limitation, any article of footwear which bears three or four parallel stripes which are

(a) on the side of the footwear extending from the normal position of the lacing or other means of closure to a position at or near the sole of the footwear; and

(b) in a colour or colours or material which contrasts with the colour or material of the part of the footwear on which such stripes are located.

9 “3-Stripe Trade Marks” was defined to mean the trademarks I have set out above. I refer to them in these reasons as the 3-Stripe Trade Marks or the applicants’ trade marks. Annexures C to N correspond to Exhibits C to N set out below.

10 The relief claimed was as follows:

1. A declaration that the Respondent has infringed the 3-Stripe Trade Marks by supplying the footwear depicted in Annexures C to N to the accompanying Statement of Claim.

2. An order that the Respondent, whether by its servants, agents or otherwise, be permanently restrained from:

(a) manufacturing, procuring the manufacture of, importing, purchasing, selling, offering to sell, supplying, offering to supply or distributing any Infringing Products; and

(b) authorising, directing or procuring any other company or person to engage in any of the conduct sought to be restrained by sub-paragraph (a) above.

3. An order that within 7 days of making this order the Respondent delivers up to the solicitors for the Applicants on oath all Infringing Products.

4. Damages or an account of profits pursuant to the Trade Marks Act 1995.

5. Interest pursuant to section 51A of the Federal Court Act 1976 [sic].

11 The applicants maintained their claims in respect of the following shoes only:

Airborne Shoe - Exhibit E;

Boston Shoe - Exhibit G;

Apple Pie Runner - Exhibit H;

Stingray Runner - Exhibit I;

Basement Shoe - Exhibit J;

Stingray Shoe - Exhibit K;

Apple Pie Shoe - Exhibit L;

Apple Pie Pink Runner - Exhibit M;

Stingray Black Runner - Exhibit N.

12 The applicants accepted, on the first day of the trial, that by reason of accord and satisfaction or estoppel, they were not entitled to relief in respect of the Apollo Shoe - Exhibit C, the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D and the Stingray Boot - Exhibit F. Senior Counsel for the applicants said in opening submissions that the applicants intended to rely on evidence relating to these shoes only in making out their allegations that Pacific Brands intended to deceive and confuse the average consumer into thinking that the impugned shoes originated from or were connected in the course of trade with adidas.

13 The respondent Pacific Brands denied the applicants’ claims on two bases: first, the use by Pacific Brands of stripes in various styles and groupings on the shoes was not use as a trade mark within the meaning of the Act and, second, the stripes were not “deceptively similar” to the applicants’ trade marks within the meaning of s 120(1) of the Act.

14 From time to time in the course of submissions it appeared that the applicants were putting that any use of four stripes on the side of sports shoes would amount to an infringement of the adidas trade marks and the case was about “stripeness” and, in answer, that the respondent was putting that any use of four stripes on the side of sports shoes could not amount to an infringement because it was plain that four stripes were not the same as three stripes. As will appear, in my opinion, the result is not so simple.

History

15 It was in 1949 that the business of adidas and its predecessors was founded by Adi Dassler in Germany under the name “Adolf Dassler adidas Sportschuhfabrik”.

16 Since 1957, adidas has continuously supplied to customers in Australia footwear bearing its trade marks. In 2009, a large volume of footwear bearing the 3-Stripe Trade Marks was sold in Australia. I accept that footwear bearing the 3-Stripe Trade Marks has been extensively promoted through (a) posters displayed in store; (b) inserts placed inside popular sporting magazines; (c) catalogues which are distributed to customers and potential customers of adidas; (d) outdoor advertising at various locations in Australia; (e) an online catalogue since at least June 2004; and (f) sponsorship of high-profile sporting athletes and teams including David Beckham, the New Zealand All Blacks rugby union team, and many prominent Australian athletes and teams.

17 I also accept that, in addition, media photographs of athletes, many of whom are sponsored by adidas, wearing footwear which identifiably bears the 3-Stripe Trade Marks frequently appear in the sport sections of newspapers and sports magazines distributed throughout Australia. Adidas received particular publicity from the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000 which featured numerous athletes or teams wearing footwear bearing the adidas trade marks.

18 The parties agreed on the following facts, the respondent not conceding their relevance:

(a) Pacific Brands, the respondent, is the successor of the footwear business of Pacific Dunlop Ltd (“Pacific Dunlop”), including in relation to the sourcing and sale of footwear.

(b) On 7 December 1973, adidas AG and Pacific Dunlop entered into a Licence Agreement. Under the Licence Agreement, adidas granted Pacific Dunlop the exclusive right within Australia to use adidas’ trade marks and the exclusive rights to manufacture, import and distribute certain adidas products within Australia. Pacific Dunlop used the adidas trade marks and distributed adidas products in Australia pursuant to that Licence Agreement. Amendments to that agreement were made on 7 March 1975 and 3 October 1975.

(c) On 26 May 1983, adidas and Pacific Dunlop entered into two agreements: a Distribution Agreement and a License Agreement. These agreements replaced the 7 December 1973 Licence Agreement. Under the Distribution Agreement, Pacific Dunlop was appointed sole distributor of adidas products in Australia. Under the License Agreement, Pacific Dunlop was granted the exclusive right to use adidas trade marks in Australia. Pacific Dunlop distributed adidas products and used the adidas trademarks pursuant to those agreements.

(d) On 1 December 1993, adidas and Pacific Dunlop entered into a License and Distribution Agreement which replaced the 26 May 1983 License Agreement. Under the License and Distribution Agreement, Pacific Dunlop was granted the exclusive right to use adidas trade marks in Australia and had the obligation to market and distribute adidas products in Australia. On the same date, Pacific Dunlop, adidas and adidas Australia, entered into a Deed of Assignment. Under the Deed of Assignment, Pacific Dunlop assigned its rights and obligations under the License and Distribution Agreement to adidas Australia.

(e) Between 1992 and 23 May 1996, adidas Australia was a subsidiary of Pacific Dunlop which owned 51% of the shares in adidas Australia. Pacific Dunlop’s shares in adidas Australia were later acquired by adidas.

(f) Mr Paul Moore was a director of the respondent during 2006 and 2007 (until 1 October). Mr Moore was previously the General Manager of adidas Australia.

(g) Mr Russell, the General Manager of Footwear and Sport for the respondent, held various positions at adidas between July 1977 and July 1988.

19 Other facts from a chronology, which was agreed by the respondent but subject to relevance, were as follows.

20 In 2006 Pacific Brands imported and sold the Apollo Shoe and Indigo Shoe in Australia.

21 From August 2007 to 31 October 2008, Pacific Brands imported and sold the Stingray Boot in Australia.

22 In September 2008, Payless Shoes imported and sold the Boston Shoe in Australia.

23 In August 2009, Pacific Brands imported and sold the Apple Pie Runner, Stingray Runner, Basement Shoe, Apple Pie Shoe and Apple Pie Pink Runner.

24 In February 2010, Pacific Brands imported and sold the Stingray Black Runner.

25 It was also common ground that the applicants’ 3-Stripe Trade Marks were very well-known or famous in Australia. Further, it was accepted that adidas had very extensively promoted and used the 3-Stripe Trade Marks over a long period of time and had never used four stripes on its footwear.

The witnesses

26 For the applicants, Mr Gregory Kerr, the managing director, Area Pacific of adidas Australia made two affidavits, one of which was read, and gave oral evidence.

27 For the respondent, Mr Graeme Russell, General Manager of Footwear for Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd made an affidavit and gave oral evidence. Mr Colin O’Donnell, Sales Manager Men’s Hush Puppies, swore an affidavit and gave oral evidence.

28 Turning to the experts, Mr David George Briggs, principal of Galaxy Market Research Company, was called by the applicants. He made two affidavits in the proceedings and gave oral evidence. Mr David Cameron McCallum, a market research consultant, was also called by the applicants: he made an affidavit and gave oral evidence.

29 The respondent called as an expert Mr John David Sergeant who had experience as a market and social researcher. He swore an affidavit in the proceedings and gave oral evidence.

30 The applicants also called as an expert Dr Constantino Stavros, an associate professor in marketing. He made three affidavits and gave oral evidence. The respondent called Dr Stanley Glaser, a retired emeritus professor of management, who made two affidavits and gave oral evidence.

31 No evidence of actual confusion was adduced.

The expert (non-survey) evidence

32 The evidence of Dr Stavros and Dr Glaser went first to the question of the use of stripes as a trade mark and second to whether confusion with the applicants’ trade marks was likely to occur when consumers viewed the Pacific Brands shoes.

33 Dr Stavros and Dr Glaser together produced a document summarising their major areas of agreement and disagreement. They said there was broad agreement about the nature and element of brands which covered the importance of brands and their elements to consumers and the roles that these played in the market place. However there was some disagreement about specific branding in relation to the adidas and Pacific Brands shoes. This was detailed as follows.

34 Dr Stavros and Dr Glaser agreed that sport shoes in general carry markings on the sides that help to distinguish them. These markings can play various roles which are not mutually exclusive. Where they disagreed was that Dr Stavros believed that these markings are perceived by consumers as being a brand element based upon the rationale contained in response to Question 8 of Dr Stavros’ first affidavit, that question being “Are the stripe markings on the footwear depicted in annexures C - N of the statement of claim likely to be perceived by consumers as a brand or a brand element”. In particular Dr Stavros’ belief was that consumers are conditioned to view such markings as brand elements. However Dr Glaser argued that these markings may simply serve to enable the consumer to categorise the shoes’ function and did not necessarily have a brand association.

35 As to whether confusion was likely to occur when consumers viewed the Pacific Brands shoes, Dr Glaser believed that consumers would not be confused and would not attribute the source of the shoes to adidas. Dr Stavros believed that given the stripe markings that appeared on the Pacific Brands shoes it was likely a significant number of consumers may misidentify the shoes as being of adidas origin or commercially related to adidas. Dr Glaser and Dr Stavros outlined their reasons for these conclusions in their affidavits, in the case of Dr Stavros this being primarily in his third affidavit.

36 Dr Stavros and Dr Glaser agreed that defining the marketplace as one of “commodity” and “performance” shoes was unrealistic and that in practice the marketplace was more diverse.

37 There was disagreement about the role that context played in consumer decision-making processes in the present matter.

38 Dr Glaser argued that the price point, distribution network, presentation of the Pacific Brands products, target market and expectations of the customer differed from the typical adidas customer’s decision-making context. As a result he argued that those factors overrode any brand or origin of manufacture connotation which the Pacific Brands markings may have.

39 Dr Stavros argued that the consumer perspective did not extend to corporate decisions such as choice of distribution networks and price points. As a result the consumer could readily expect to encounter a shoe that resonated with their belief that markings on it would constitute a brand element in a variety of contexts and that such an interaction would not be significantly diminished by other contextual elements, such as price and location.

40 Dr Stavros and Dr Glaser agreed that outlets such as Kmart and Target carried a range of brands in various categories, some of which may be regarded as “leading” brands. Dr Glaser argued that historically consumers did not expect to see adidas shoes in outlets such as Kmart. However he acknowledged that this may change as the strategies of shoe marketing companies shift to remain more competitive. Dr Stavros argued that such outlets carry brands that consumers were familiar with and that consumers, unaware of the distribution strategies of organisations, would not be at all surprised if leading footwear brands were present in those outlets.

Use as a trade mark within the meaning of the Act

41 As to use of the stripes on the shoes as a trade mark, s 17 of the Act provided:

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used to distinguish goods or services

dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services

so dealt with or provided by any other person.

42 The word “sign” was stated in s 6 of the Act to include, unless the contrary intention appeared:

… the following or any combination of the following, namely any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent;

43 In E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144, French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ said:

[41] The concept of “use” of a trade mark which informs ss 92(4)(b), 100(1)(c) and 100(3)(a) of the Trade Marks Act must be understood in the context of s 17, which describes a trade mark as a sign used, or intended to be used, to “distinguish” the goods of one person from the goods of others.

[42] Whilst that definition contains no express reference to the requirement, to be found in s 6(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth), that a trade mark indicate “a connexion in the course of trade” between the goods and the owner, the requirement that a trade mark “distinguish” goods encompasses the orthodox understanding that one function of a trade mark is to indicate the origin of “goods to which the mark is applied”. Distinguishing goods of a registered owner from the goods of others and indicating a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the registered owner are essential characteristics of a trade mark. There is nothing in the relevant Explanatory Memorandum to suggest that s 17 was to effect any change in the orthodox understanding of the function or essential characteristics of a trade mark.

[43] In Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1996) 96 FCR 107 at 115 [19] per Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ a Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia said:

“Use ‘as a trade mark’ is use of the mark as a ‘badge of origin’ in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods … That is the concept embodied in the definition of “trade mark” in s 17 – a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else.”

That statement should be approved.

(footnotes omitted)

Heydon J at [87] agreed with the substance of these paragraphs, except with the last sentence of [42].

44 The respondent submitted that in order to succeed in an infringement proceeding, the registered trade mark owner must establish that the use of the impugned sign by the alleged infringer was use as a trade mark. That is, the impugned sign must, when considered in context, operate as a “badge of origin” – it must be used to distinguish goods dealt with by one person from like goods dealt with by someone else: Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1996) 96 FCR 107 at [19]; Aldi Ltd Stores Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185 at [22]; E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd at [43]; Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v NestlÉ Australia Ltd (2010) 272 ALR 487 at [19]; Australian Health & Nutrition Association Ltd t/as Sanitarium Health Food Co v Irrewarra Estate Pty Ltd t/as Irrewarra Sourdough (2012) 292 ALR 101 at [15]-[25]. This was the Court’s first inquiry when considering the issue of trade mark infringement. If the answer to that inquiry was no, then that was the end of the matter. It was only if the answer was yes that the Court goes on to consider the issue of whether a sign is deceptively similar to a registered trade mark: Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd (2008) 76 IPR 161 at [49] per Sundberg J.

45 In determining whether or not the sign was being used as badge of origin, the respondent submitted the context in which the impugned sign was used was “all important”: Global Brand Marketing (2008) 76 IPR 161 at [61(g)]; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185 at [22]-[23] applying Kitto J in Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422. The respondent also relied on Mayne Industries Pty Ltd v Advanced Engineering Group Pty Ltd (2008) 166 FCR 312 at [60] – [62] per Greenwood J.

46 The respondent submitted that the four stripes that were used by it were used in various styles and groupings. For example:

(a) the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D had four brightly coloured stripes of different colours which overlapped the shoe to form a lace which was secured by Velcro;

(b) the Basement Shoe - Exhibit J had two pairs of two silver stripes with a large gap between them;

(c) the Apple Pie Pink Runner - Exhibit M had two pairs of two pink stripes with a large gap between them; and

(d) the Stingray Runner - Exhibit N had four grey stripes that were wider at the top and taper to a narrower end at the bottom.

47 The respondent submitted that the context in which Pacific Brands used the stripes on its shoes included:

(a) as decorative elements;

(b) as a function indicating that the product was a sports shoe (or leisure shoe);

(c) in some cases, performing functional purposes; and

(d) the use of Pacific Brands’ registered trade marks (such as Grosby) on the shoes.

48 The respondent submitted that the context in which its Pacific Brands’ shoes were sold included:

(a) the shoes were not performance shoes sold in specialist stores;

(b) the shoes lacked high technical specification;

(c) the shoes were sold through low cost stores;

(d) generally, in smaller retailers, the shoes were sold by being stacked in boxes on the store floor arranged to indicate the size;

(e) generally in larger retailers, the shoes were sold as “hang sell” tied together with elastic or plastic;

(f) generally the shoes were sold with little or no sales assistance;

(g) the shoes were low cost “commodity” shoes;

(h) the shoes featured Pacific Brands’ registered trade marks such as “Stingray”, “Tristar”, “Apple Pie” and “Basement”; whereas

(i) in contrast, performance shoes such as adidas were typically purchased:

(i) in a setting such as a specialist footwear or department shoes;

(ii) with the assistance of a salesperson, who retrieved a pair of shoes from a storage area; and

(iii) in a setting where brand advertising and point of sale material was employed.

49 The respondent submitted that given:

(a) the widespread use of stripes on sports shoes;

(b) Dr Glaser’s evidence as to the use of the stripes on shoes;

(c) the context in which the stripes were used by Pacific Brands on the impugned shoes including:

(i) the various decorative and/or functional elements of the Pacific Brands

stripes; and

(ii) the use of other marks to distinguish the Pacific Brands shoes;

(d) the context in which Pacific Brands’ shoes were sold; and

(e) the context in which adidas shoes were sold;

the use of stripes on the shoes Exhibits E and G - N was not use as a trade mark within the meaning of the Act. The stripes on the shoes were not being used as a badge of origin to distinguish those goods from the goods of some other trader. On this fundamental threshold issue alone, the respondent contended, the proceedings should be dismissed.

50 The applicants submitted that there was no strict dichotomy between another function (such as description or decoration) and a function as a badge of origin: a particular use may serve more than one function: Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 per Lockhart J at 335; per Gummow J at 347. Further, there may still be trade mark use although another trade mark or indication of origin was used in the same packaging or advertisement: Johnson & Johnson per Gummow J at 349; Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 33 IPR 161 per Sackville J at 179, 182 and 185.

51 In relation to the latter issue, the applicants submitted, Allsop J pointed out in Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [191] that it was not to the point to say that because another part of the label was the obvious and important “brand”, that another part of the label could not act to distinguish the goods. The respondent’s reliance on its other trade marks therefore did not advance the matter very far for the respondent.

52 The applicants submitted a determination of trade mark use required an objective examination of the use in the context in which the mark appeared, in order to determine whether the sign would be perceived by the public as distinguishing the trader’s goods from those of other traders: Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2002) 190 ALR 185 at [22] per Hill J; at [76] per Lindgren J.

53 An important aspect of the context in the present case, the applicants submitted, was that, in the sports footwear category, logos serving as a badge of origin were traditionally placed on the sides of shoes between the sole and the laces as this space was visible from numerous angles. For example, in addition to adidas using its marks on the sides of its shoes, Nike generally placed its “swoosh logos” on the sides of its shoes; ASICS used a criss-cross pattern of stripes on the sides of its shoes; New Balance typically placed a stylised “N” design on its shoes; and Puma used a single, curved stripe on its shoes. The applicants’ expert, Dr Stavros, and the respondent’s expert, Dr Glaser, agreed that sport shoes in general carry markings on the sides that help to distinguish them. These markings can play various roles which were not mutually exclusive. Mr Sergeant, the respondent’s expert, also agreed that sports shoes have trade marks on their sides. In Beecham Group Plc v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (2006) 66 IPR 254 at [48], Emmett J took into account the placement of trade marks on competitors’ brands in support of a conclusion that there was use as a trade mark.

54 Given that context, the applicants submitted it was plain that, whatever decorative function the four stripe mark may also serve, consumers were accustomed to seeing the material appearing on the side of a sports shoe as functioning as a badge of origin, and would regard the four stripe marks as badges of origin accordingly. The fact that the side of sports shoes were used as a place to display trade marks was a permissible matter of context, or perhaps “trade usage” as referred to in s 219 of the Act.

55 In the applicants’ submission, the respondent sought to use the rubric of “context” to broaden the inquiry as to whether there was a use as a trade mark beyond permissible bounds. The applicants submitted that the only relevant context was the purpose and nature of the impugned use, and context relating to how the mark had been adopted or applied in relation to the goods and any relevant advertising (although there was no relevant advertising in this case). That was the approach taken in the authorities and must be logically correct. The authorities were clear. In Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v NestlÉ Australia Ltd (2010) 272 ALR 487 at [19], the Full Court summarised the relevant principles.

56 Thus, “context” was not the open-ended inquiry on “surrounding circumstances” for which the respondent contended. The reasoning of Jagot J in Australian Health and Nutrition Association Ltd v Irrewarra Estate Pty Ltd (2012) 292 ALR 101 at [27]-[31] provided, it was submitted, an orthodox and correct application of the concept of “context”.

57 The applicants submitted that the logic was also clear. It could not be the case that an examination of all the surrounding circumstances of a “typical” sale, divorced from how the mark was adopted or applied in relation to the goods, was permitted to determine whether there was use as a trade mark. Whether there was use as a trade mark could not depend on the present or “typical” circumstances of sale, which may change. Otherwise, it would have the absurd result that the answer to the question of whether a four stripe mark used on a shoe of the respondent was used as a trade mark could change on some day in the future if it came to be sold through, for example, a specialist store such as Athlete’s Foot, notwithstanding the appearance of the mark on the shoe had not changed. Also, how other shoes were sold was completely irrelevant to the question of trade mark use by the respondent. That question must be able to be answered purely by looking at how the mark had been adopted or applied in relation to the respondent’s goods.

58 The applicants did not seek to rely on the survey evidence in relation to the issue of “use as a trade mark”. The survey was relied upon solely on the question of deceptive similarity. I will consider the survey evidence in detail later in these reasons.

Consideration

59 In relation to use as a trade mark the Full Court in Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v NestlÉ Australia Ltd (2010) 272 ALR 487 at [19] summarised the relevant principles as follows, the issue being whether NestlÉ used “luscious Lips” as a trade mark:

(1) Use as a trade mark is use of the mark as a “badge of origin”, a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else: Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19]; E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [43].

(2) A mark may contain descriptive elements but still be a “badge of origin”: Johnson & Johnson Aust Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 347–8; Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 33 IPR 161; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185 at [60].

(3) The appropriate question to ask is whether the impugned words would appear to consumers as possessing the character of the brand: Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422.

(4) The purpose and nature of the impugned use is the relevant inquiry in answering the question whether the use complained of is use “as a trade mark”: Johnson & Johnson at 347 per Gummow J; Shell Co at 422.

(5) Consideration of the totality of the packaging, including the way in which the words are displayed in relation to the goods and the existence of a label of a clear and dominant brand, are relevant in determining the purpose and nature (or “context”) of the impugned words: Johnson & Johnson at FCR 347; Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182.

(6) In determining the nature and purpose of the impugned words, the court must ask what a person looking at the label would see and take from it: Anheuser-Busch at [186] and the authorities there cited.…

60 Applying these principles to a design rather than to words, the question at this stage is not whether the respondent has used a sign so as to indicate a connection between it and the applicants. Instead the question is whether the use indicates a connection between the shoes in question and the respondent.

61 I accept that the stripes on the shoes have a decorative element and that the stripes may also act to indicate that each shoe is a sports shoe but that does not mean that those elements constitute the only use of the stripes as a sign: they are not mutually exclusive.

62 As Dr Glaser accepted, the stripes were capable of functioning as an identifier. As I understood his evidence it was that the stripes did not so function by reason of the other matters of context to which he referred.

63 In my opinion, the evidence of Dr Glaser and the respondent’s submissions take too broad a view of “context”, which should have as its focus the purpose and nature of the impugned use, as submitted by the applicants.

64 The evidence was that signs as identifiers are generally placed on the side of sports footwear, where the stripes on the impugned shoes are to be found. This indicates that the decorative element of the stripes or their indication that each shoe is a sports shoe would not be dominant.

65 Dr Glaser gave evidence that stripes would not, without more, be considered by the consumer to be a trade mark. He said that in order to understand an arrangement of four stripes as something more than just decoration of a sports shoe a consumer must be conditioned to understand that the four stripes act as a cue to the source of the product. For example, he said, adidas had conditioned consumers to understand three stripes on the side of its sports shoe as a trade mark but this was not a straightforward exercise and required the successful combination of a number of measures which he then detailed. Absent those measures, Dr Glaser said, it was unlikely that a consumer would be conditioned to understand stripes on sports shoe as a cue to the origin of the product.

66 However, in my opinion, merely because a consumer may not know enough about a manufacturer or seller to associate the sign with a specific named manufacturer or seller does not mean the sign is not used to distinguish the goods from the goods of another or indicate a connection with the manufacturer or seller: see Mark Foy’s Limited v Davies Coop and Co Ltd (1956) 95 CLR 190 at 204 per Williams J with whom Dixon CJ agreed; Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 per Gummow J at 348. As I have said, it was accepted that signs as identifiers are now generally placed on the side of sports footwear. How they came to be generally so placed is not of present significance.

67 As Dr Stavros said in his evidence, the fact that a company, such as the respondent company, does not invest in promoting brand elements or does not ensure their consistent application does not necessarily lead to consumers disassociating such elements from their existing understanding of the category, which is likely to include perceptions that sport shoes feature brand symbols on them.

68 For these reasons my conclusion is that in each case the stripes on the impugned shoes were used as a trade mark: the use indicates a connection between the shoes in question and the respondent.

Deceptively similar

69 The relevant principles were stated by the applicants to be found first in Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 595, where Kitto J said:

It is not necessary, in order to find that a trade mark offends against the section, to prove that there is an actual probability of deception leading to a passing-off. While a mere possibility of confusion is not enough—for there must be a real, tangible danger of its occurring …—it is sufficient if the result of the user of the mark will be that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products come from the same source. It is enough if the ordinary person entertains a reasonable doubt.

70 In Vivo International Corp Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc (2012) 294 ALR 661 at [77] the Full Court said:

In this regard, as has been repeatedly said in the authorities the issue is not whether consumers might think that the trade marks are the same, but whether a number of persons will be caused to “wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products or closely related products and services come from the same source … [or to] wonder or be left in doubt about whether the two sets of products … come from the same source”: see Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [50].

71 In Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658, Dixon and McTiernan JJ said:

But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. … The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight.

72 The respondent relied on the statements in Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [143]-[146], where Allsop J stated the test for deceptive similarity as follows:

The question of deceptive similarity must be judged by a comparison different from the side by side comparison undertaken to assess substantial identity; the question being the likelihood of deception or confusion from a recollection or impression of the registered mark. Thus, a side by side comparison is inadequate, and too narrow a test. The comparison is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the registered mark used in a normal or fair manner that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the impugned mark as it appears in the use complained of: Shell Co of Australia v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414; Re Smith Hayden & Co Ltd’s Application (1946) 63 RPC 97; Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 128; and cf Johnson & Johnson v Kalnin (1993) 114 ALR 215 at 220; 26 IPR 435 at 440.

The proper approach to the answering of this question is laid out in judgments of high authority. First, there is what was said by Parker J (as his Lordship then was) in Re Pianotist Co Ltd’s Application (1906) 23 RPC 774 at 777 which was applied by Dixon, Williams and Kitto JJ in Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd (1952) 86 CLR 536 at 538 …

As set out in Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd (1952) 86 CLR 536 at 539, it is not sufficient that the two marks convey merely the same idea.

In Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 128–9 Gummow J said:

Where the comparison of the marks is necessary to determine whether that of the defendant is deceptively similar to the registered mark of the plaintiff, who sues for infringement, the primary comparison must be between the registered mark on the one hand and the mark as used by the defendant on the other. The comparison differs from that in a passing off action where the plaintiff points to the goodwill built up around the mark by reason of prior use and then points to the conduct of the defendant as leading to deception (or perhaps merely confusion) and consequent damage to that goodwill of the plaintiff.

…

The statement that in infringement proceedings the concern “for practical purposes” is only with the marks themselves requires some elaboration in the light of the other writings and authorities on the 1938 Act and the present Australian legislation, to which I have referred. In particular — (i) The comparison is between any normal use of the plaintiff's mark comprised within the registration and that which the defendant actually does in the advertisements or on the goods in respect of which there is the alleged infringement, but ignoring any matter added to the allegedly infringing trade mark; for this reason disclaimers are to be disregarded, price differential was considered irrelevant by Kearney J [in Polaroid Corporation v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491] and Cross J [in British Petroleum Co Ltd v European Petroleum Distributors Ltd [1968] RPC 54], his Lordship also disregarded the differences in use by the parties of colour and display panels, and his Honour discounted the differences in the respective sections of the public to whom the goods were sold. (ii) However, evidence of trade usage, in the sense discussed above, is admissible but not so as to cut across the central importance of proposition (i). (iii) In particular, in making an aural comparison of the marks, whilst ordinarily one is concerned with what appears to be the natural and ordinary pronunciation, evidence in my view is admissible that those in the trade pronounce the defendant's mark in a manner which otherwise might be thought to vary from the normal fashion. (iv) Evidence of cases of deception or confusion may be taken into account (see, for example, British Petroleum Co Ltd v European Petroleum Distributors Ltd [1968] RPC 54 at 64). (v) Although, as Australian Woollen Mills (supra) itself decides, it is not decisive, evidence is admissible that the defendant's mark was adopted with a view to “sailing close to the wind”, in the sense of the adverse finding made by the primary judge in this case.

73 Deceptive similarity is a question for the judge. In Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co Ltd v New South Wales Dairy Corporation (1990) 24 FCR 370 at 377 the Full Court said:

The roles of judge and witness were explained by Lord Evershed MR in Electrolux Ltd v Electrix Ltd (1953) 71 RPC 23 at 31. He said:

The question of infringement, the question whether one mark is likely to cause confusion with another, is a matter upon which the judge must make up his mind and which he, and he alone, must decide. He cannot, as it is said, abdicate the decision in that matter to witnesses before him.

74 The respondent also referred to Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 for the proposition that two essential principles in determining deceptive similarity were set out by Kitto J in that case at 595: (a) the registered trade mark owner must show that there is a real, tangible danger of confusion occurring, a mere possibility is not sufficient; and (b) a trade mark is likely to cause confusion if the result of its use will be that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products come from the same source.

75 It is also necessary to set out s 10 of the Act as follows:

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

76 I do not find the concept of “initial interest confusion”, “customer confusion that creates initial interest in a competitor’s product”, as exemplified in Playboy Enterprises Inc v Netscape Communication Corp 354 F 3d 1020 (9th Cir. 2004) at [2] as adding, for present purposes a useful additional tool of analysis. Further, I do not read Tivo Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 at [105] (at first instance) as involving this concept.

77 Also I do not find the concept well-known in psychology called the “just noticeable difference” (JND), being the minimum amount by which a stimulus must be changed in order to produce a noticeable difference to an average person, to be of any assistance. Contrary to the submission of the respondent, and it was not put as replacing the legal test, I am not persuaded that the concept of JND is of help to the Court in determining whether there has been deceptive similarity, that is, in considering the imperfect recollection of a trade mark by a consumer. I am referring here to the evidence of Dr Glaser who gave his opinion that, when considering the Pacific Brands use of stripes, it was his opinion that use was sufficiently different from the adidas trade marks to exceed the JND threshold. In my opinion to approach the matter in that way, at least in the circumstances of the present case, is to add unnecessary refinement to the question of deceptive similarity.

78 Applying these principles, the applicants submitted there were at least eight important matters to take into account.

79 First, in applying the test of deceptive similarity, it was “important to consider what has been described as the “the idea of the mark”, that is the idea which the mark will naturally suggest to the mind of one who sees it”: Jafferjee v Scarlett (1937) 57 CLR 115 at 121-122 per Latham CJ (with whom McTiernan J agreed). The idea of the mark was sometimes expressed as whether the allegedly infringing mark takes a “significant and distinctive element” (Effem Foods Pty Ltd v Wandella Pet Foods Pty Ltd (2006) 69 IPR 243 at [36]), or “essential feature” of the earlier trade mark (Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd (2004) 209 ALR 1 at [93]; Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 89 IPR 457 at [107]- [114]). If “the mark comes to be remembered by some feature in it which strikes the eye and fixes itself in the recollection” (Saville Perfumery Ld v June Perfect Ld (1941) 58 RPC 147 at 162), then confusion is likely to result if that feature is adopted in another trade mark.

80 Second, and related to the first point, the court will normally place significant weight on the first impression of a mark. This recognised that once a person has become familiar with two marks they were very unlikely to be confused, but at the point that a person is first exposed to the allegedly infringing mark confusion may well occur (Re Bali Brassiere Co Inc's Registered Trade Mark and Berlei Ltd's Application (1968) 118 CLR 128 at 136- 137 (first instance per Windeyer J)), and that initial confusion was sufficient to make out a case of deceptive similarity.

81 Third, as Dodds-Streeton J recently re-iterated in Tivo Inc v Vivo International Corp Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 at [105]:

It is well established that trade marks may be deceptively similar … even if confusion is unlikely to persist up to the point of, and contribute to, inducing sale.

82 Fourth, a finding of deceptive similarity cannot be avoided by showing that the public will not in fact be deceived as to the origin of the goods by the inclusion by the respondent of other material, such as its own trading names or brands, in conjunction with the impugned mark: see Caterpillar Loader Hire (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Caterpillar Tractor Co (1983) 48 ALR 511 at 513 -514 per Franki J and also Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop and Co Ltd (1956) 95 CLR 190 at 204-205 per Williams J (Dixon CJ agreeing) at 195.

83 Fifth, whilst the question of deceptive similarity is ultimately one for the court, the evidence of expert witnesses may be of assistance in determining deceptive similarity. In particular, an appropriately qualified expert may give evidence about the possibility that consumers would be misled or confused.

84 In the present case, Dr Stavros gave evidence relating to the use of brands in general and in the sports footwear market in particular, so as better to inform the Court’s comparison of the adidas trade marks and the respondent’s trade marks.

85 Sixth, the intention or design of the respondent in deliberately seeking to imitate the adidas trade marks, or at the very least to “sail close to the wind” in that regard, was relevant to the assessment of deceptive similarity.

86 Seventh, the strength or “fame” of a trade mark must be taken into account in assessing the imperfect recollection of the registered trade mark which was relevant in the deceptive similarity test.

87 Eighth, the survey evidence in the present case provided clear evidence that a significant proportion of persons would be deceived or confused.

88 I was referred to the recent decision of the Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa in Adidas AG & another v Pepkor Retail Limited (187/12) [2013] ZASCA 3 (28 February 2013). There it was held at [25] that it was immediately apparent, on first impression, that the four stripe marks on the respondent’s soccer boot and the respondent’s Boys’ ATH Leisure Shoe, the respondent’s “Hang Ten” sports shoe and the respondent’s “Girls Must Have” shoe were not similar to the first appellant’s trademarks and consequently that there was no likelihood of deception or confusion. That left the four stripe mark on the LDS Sportshoe and on the Men’s ATH Leisure Shoe which were held at [27] to infringe. However, no doubt by reason of the largely factual basis of these claims, with respect, I did not find the reasoning or conclusions to be of assistance.

89 The respondent submitted that the shoes Exhibits C through N contained four stripes in various styles and groupings. In bringing this infringement proceeding adidas was seeking to extend its monopoly over its 3-Stripe Trade Marks with respect to shoes to the use of four stripes on shoes. The wide relief sought by adidas would effect a de facto registration of a trade mark that has never been used by adidas and was not inherently adapted to distinguish adidas’ goods.

90 The shoes Exhibits C and E through N were imported by a division of Pacific Brands known as Global. Global had as its focus the commodity market, producing low specification shoes at very low prices. Such were the price point considerations and pressures resulting from low order volume that Global did not “design” shoes per se but rather selected shoes from Chinese suppliers. Small design variations on these selected shoes were sometimes possible. The shoe Exhibit D was designed and imported by a division of Pacific Brands known as Grosby. The shoe retailed at $19.95 which was at the very lowest end of Grosby’s range of typical retail prices.

91 None of the shoes Exhibits C through N remained stocked by Pacific Brands and none had been sold for several years.

92 The respondent submitted that in considering the adidas trade marks as used in a normal or fair manner (ie how those marks are used), at a minimum the following were highly relevant:

a) from visual inspection, the 3-Stripe Trade Marks were simple - three stripes in a simple parallel configuration;

b) adidas had always used three stripes and had never used four stripes;

c) adidas builds an “aspirational product” made to high standards and to meet various performance specifications to which its 3-Stripe Trade Marks were applied. In Dr Stavros’ terms, a consumer’s first encounter was to see the marks on the shoe;

d) adidas had spent very large sums of money promoting its footwear bearing the 3-Stripe Trade Marks for more than 60 years including by sponsoring extremely high profile sporting events (including the Sydney 2000 Olympics), sportsmen and celebrities, ie this was normal use of these particular marks.

93 In cross-examination Dr Stavros confirmed his view that adidas had “embedded the three stripe brand into popular culture”.

94 Similarly, the respondent submitted, in assessing the various impugned marks the subject of these proceedings as they appeared in the use complained of, at a minimum, the following were highly relevant:

a) all of the impugned shoes were shoes made of synthetic materials with no performance specification (they were commodity shoes of basic or poor quality) and this was the type and quality of shoe to which the various four stripes were applied; and

b) the shoes were not advertised and were sold in basic displays (hang sell, stacked boxes) where the stripes were often obscured.

95 During cross-examination Dr Glaser gave a succinct assessment of his opinion regarding the likelihood of confusion as follows:

where you have a company that has been working hard to establish three stripes as their mark for 60 years, the confusion, while possible, is unlikely.

96 To establish “deceptive similarity” it was not sufficient that the two marks conveyed merely the same idea: Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [145]; Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd (1952) 86 CLR 536 at 539. ‘Stripeness’ as was coined by Senior Counsel for adidas had the character of an idea. It was far too liberal an approach to the notion of recollection (even an imperfect one) relevant to the assessment of deceptive similarity.

97 In this case, the comparison will be between the adidas trade marks and the various four stripe configurations as they appear on each of the impugned shoes.

Intention

98 Much emphasis was placed by the applicants on the respondent’s intention. I consider first the legal framework and I then turn to consider, chronologically, the facts said to be relevant to this issue.

99 The applicants submitted that the classic formulation of the relevance of intention to the question of deceptive similarity was found in the following passage from Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v. FS Walton and Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 657-8:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive. Moreover, he can blame no one but himself, even if the conclusion be mistaken that his trade mark or the get-up of his goods will confuse and mislead the public.

100 I note that in that case their Honours began and ended these remarks with the following:

But the examination made of the respondent’s motives and good faith seems to us to leave the question of infringement and passing off very much in the same position as it stood in without it.

…

But the practical application of the principle may sometimes be attended with difficulty. In the present case it has caused a prolonged and expensive inquiry into the states of mind, motives and intentions of three people whose combined judgment decided that the company should adopt the trade brand and description complained of. This in turn necessitated an investigation of the steps by which the picture was obtained, considered and adopted and what was said and done by a number of persons in relation to the subject. From all this material, it appears to us that no more emerges than that though the name and mark Caesar were not sought or taken with any fraudulent intent, yet three or four people conversant with the matter saw in them too great a resemblance to those of the appellant, that their views were disregarded by the respondent, who may have thought they were erroneous, or may have thought that such a resemblance, if it existed, only added to the suitability of the mark. Incidentally the issue of intention provided an occasion for the disclosure in the witness box of much want of candour on the respondent's side. But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.

101 The applicants submitted that the first of these passages had been applied in numerous cases since, including Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 129 per Gummow J. See also Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 55 IPR 354 at [45] and [117]-[121].

102 The respondent submitted that the dicta of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills (1937) 58 CLR 641 relied on by the applicants assumed that intention had been proven. The dicta were directed at the consequences of proof of intention. Subsequent Full Federal Courts had urged the need for great caution in applying their Honours’ dicta to establish deceptive similarity. In Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185 at [34], Hill J after quoting their Honours’ dicta said:

It is clear from the report that this comment was not made only with respect to the issue of fraud, but that it went, as well, to the trade mark issue whether the use of the mark might deceive or confuse members of the public. Nevertheless, it is also clear from what was said that their Honours regarded both issues as ultimately questions of fact to be decided by the Court. Their Honours were not seeking to enunciate a principle of law. While the presumption would not be lightly rejected, if there is no reasonable probability of deception or confusion then there can be no infringement.

See also per Lindgren J at [97].

103 I note also that more recently the High Court has said in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [33]:

… it is well established by the authorities referred to by the Privy Council in Cadbury-Schweppes Pty Ltd v Pub Squash Co Ltd [1981] RPC 429 at 493-494; [1980] 2 NSWLR 851 at 861 that, where there is such a finding of intention to deceive, the court may more readily infer that the intention has been or in all probability will be effective. Nevertheless, the actual decision in that case, favourable to the defendant, is a reminder that even an imitation of one product by another does not necessarily bespeak an intention to deceive purchasers. In particular, if Campomar were to retain its registrations and put them to use on a new range of products, the use thereon of nike would not necessarily indicate an intention to deceive purchasers.

104 Against that framework, the applicants’ argument based on intention was summarised as follows:

(a) the respondent was the successor in business to a former licensee of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks, and was therefore aware of the considerable commercial success of products sold bearing the 3-Stripe Trade Marks. As an expert in the trade it could not fail to be;

(b) the sequence of the respondent’s product development, in parallel with its strategy for dealing with adidas’ complaints, demonstrated a conscious attempt to create colourable variations on the 3-Stripe Trade Marks while still retaining their essential features, apparently in an effort to maintain plausible deniability of infringement whilst still suggesting the 3-Stripe Trade Marks to consumers. Applying Australian Woollen Mills, this provided a reliable and expert opinion that consumers will be deceived or confused; and

(c) the respondent had copied other aspects of shoes bearing the 3-Stripe Trade Marks (compare Exhibit A with Exhibits E, K and L; and Exhibit B with Exhibit F) and whilst those copied elements were not themselves taken into account in the trade mark comparison - as they would be in a passing off case – nevertheless they were indicative of an intention to trade off adidas’ reputation, and from this an inference may be drawn that the intention included using the four stripe mark to convey to consumers the essential features of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks so as to deceive or confuse them into perceiving some association between the maker or seller of the respondent’s shoes and the owner of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks.

105 The respondent submitted that the applicants sought and were granted leave to file an amended statement of claim on 10 April 2013. At paragraph 55A of that amended statement of claim, the applicants alleged that Pacific Brands intended that the “trade marks” on the shoes Exhibits C through N (albeit that the applicants had since accepted Pacific Brands’ accord and satisfaction defence in relation to shoes Exhibits C, D and F) possessed sufficient resemblance to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks as to be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

106 Despite wide-ranging discovery having been made (including in relation to categories specifically directed to any documents that evinced Pacific Brands’ assumed intention), there was no contemporaneous documentary evidence of Pacific Brands deliberately manufacturing or ordering products from suppliers which were based upon adidas’ iconic 3-Stripe Trade Marks with the intention to deceive consumers or cause confusion. This was entirely consistent with the anodyne “design processes” described by Mr Russell and Mr O’Donnell.

107 The attempt by the applicants to construe the correspondence in relation to the alternate stripe configurations proposed for the Boston Shoe after adidas complained about that shoe (ie once it was in the market place as a Payless product) was chronologically flawed and could not fix an intention to Pacific Brands in relation to its “design process” generally.

108 Given that the notoriety of the 3-Stripe Trade Marks was not a matter of controversy, it was not possible to see how the prior commercial relationship could give rise to any special advantage enjoyed by Pacific Brands with respect to the use of stripes on shoes.

109 The basis for the claim of intention was the “resemblances” between certain of the applicants’ shoes and certain of Pacific Brands’ shoes. That was, on the one hand a vague allegation. On the other hand, it was a circular argument to claim that physical resemblances that give rise to deceptive similarity can be relied upon to effect the intention to deceive and confuse.

110 At the level of detail, the applicants submitted that the evidence in relation to the respondent’s product development as it emerged on discovery, particularly when considered in the light of the position which the respondent was adopting in relation to complaints made by adidas, provided the basis for an inescapable inference that the respondent was doing all it could to stay as close to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks as possible, because it perceived that strategy was to its commercial benefit.

111 The applicants contended for a Jones v Dunkel inference that the evidence of none of Mr Grover, Mr Frank Zheng or Mr Pat Maher would have helped to dispel the inferences from the course of conduct and documents referred to below. They submitted the significance of Mr Grover emerged during Mr O’Donnell’s evidence and was supported by the correspondence between the respondent and adidas’ solicitors. The strategy referred to below was evidently managed by Mr Grover.

112 The applicants submitted that the respondent’s strategy with respect to each of the shoes, Exhibits C-N, had been consistent. This had been to launch shoes with four stripes, variously articulated but with marks as close as possible to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks and, when challenged by adidas, either to say that the shoe was out of stock, or to undertake not to import and sell that particular shoe – but to refuse any broader undertaking. The subsequent design process had then been a series of very incremental changes to the articulation of the four stripes but an insistence on using them, about which the respondent offered no explanation.

113 The applicants’ submissions then turned to the design process. The matters outlined, the applicants submitted, gave rise to an inference that the intention of the employees of the respondent responsible for conceiving the design of the Indigo Shoe was to trade off the reputation of adidas in the 3-Stripe Trade Marks by causing confusion between the mark on the impugned shoes and the 3-Stripe Trade Marks. That inference could be more confidently drawn given that witnesses in the respondent’s camp, namely current or ex-employees with direct involvement in the design, were not called by the respondent to explain the position: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298.

114 The applicants concluded by submitting that the respondent had indeed fashioned the above “implement[s] or weapon[s] for the purpose of misleading potential customers”. This provides the reliable and expert opinion spoken of in Australian Woollen Mills and applied many times since.

115 The respondent submitted the assertions by adidas were untenable for a number of reasons. Properly analysed, the shoes did not represent a linear evolution. For example: (a) Apollo Shoe - Exhibit C and Indigo - Exhibit D were the first shoes in the chronology and yet could hardly be said to be the “closest” to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks. Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D had four straps of different colours. The stripes on each of these shoes performed a functional purpose, extending in the case of the Apollo Shoe to hold the laces and in the case of the Indigo Shoe to form Velcro fasteners; (b) the Stingray Boot - Exhibit F which was early in the chronology did not have equidistant stripes - the stripes were grouped into two sets of two stripes; and (c) despite adidas’ description of the Stingray Black Runner - Exhibit N as the “end point” in the alleged linear evolution due to its curved, tapering stripes, it was introduced before the interconnecting tab was introduced between stripes 2 and 3 of the Boston.

116 The first reference in the tendered documents to the “spacing out” of two pairs of two stripes occurred in correspondence dated 12 December 2007 in relation to the Boston Shoe. This was before Pacific Brands received notice of adidas’ claim in relation to the Boston Shoe (late 2008) so it could not be said to be a response to that claim.

117 The insertion of an interconnecting stripe between stripes 2 and 3 of the Boston Shoe was a commercially reasonable solution to the problem posed by having 13,000 pairs of shoes produced by a factory which Payless would not accept after receipt of complaint by adidas.

118 The applicants had repeatedly invited the court to draw inferences in relation to the attempts by Pacific Brands to “move away” from a four stripe mark which may be considered close enough to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks to elicit complaint. Adidas also alleged that Pacific Brands attempted to get as close as possible to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks. It was difficult to see how these allegations could be reconciled.

119 A more logical explanation, the respondent submitted, would appear to be as follows: (a) Pacific Brands was well aware of adidas’ 3-Stripe Trade Marks (as Pacific Brands submitted any sports shoe manufacturer in Australia would be); (b) Pacific Brands wanted to exercise its legitimate right to display stripes (including four stripes) on sports shoes which was entirely consistent with how many commodity shoes were decorated, ie stripes operated as a categorisation cue for sports shoes even if they also functioned as a trade mark for adidas (when used as the 3-Stripe Trade Marks as registered); (c) Pacific Brands proffered various undertakings in relation to a very small number of shoes (particularly when considered in the context of the millions of shoes it sold each year) between 2006 and when adidas commenced these proceeding on 18 October 2010). This was not evidence of the strategy adidas contended for but a pragmatic commercial response to episodic shoes that formed a very small part of Pacific Brands business.

120 Mr O’Donnell in cross-examination was taken to correspondence between Pacific Brands and Alleston, a manufacturer in China. That correspondence was evidence of no more than Pacific Brands assisting its client Payless to alter the Boston Shoe with the assistance of one of its manufacturers in the face of adidas’ claims of infringement and then a pragmatic response to being left with the stock Payless ordered but of which it ultimately refused to accept delivery.

121 The respondent said that the courts in applying Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 recognised that an inference may be drawn with greater confidence where a person able to put a true complexion on the facts relied on for the inference was not called in circumstances in which it was reasonable to expect him or her to be called. The rule in Jones v Dunkel did not operate to fill an evidentiary gap in the other party’s case. There was nothing in the allegations as to intention or the evidence that these individuals were “required to explain or contradict”: R v Burdett (1820) 4 B & Ald 95 at 161-2 (106 ER 873 at 898). The allegations as to intention were first pleaded in the amended statement of claim (although an earlier version of the intention pleading was provided to Pacific Brands’ solicitors on 5 April 2013). Subject to leave granted to file Dr Glaser’s 18 April 2013 affidavit, Pacific Brands’ affidavit evidence was completed on 12 July 2012.

122 As to Mr Grover, he was a current employee and officer of Pacific Brands; and was and is legal counsel for Pacific Brands. There was no evidence that indicated that Mr Grover was in any way involved in the design or selection of the impugned shoes. This was hardly surprising as he is a lawyer, not a designer, businessman or salesman. There was no evidence that Mr Grover was involved in any conduct which gives rise to any finding of intention on the part of Pacific Brands to deceive or confuse any consumers into associating the impugned shoes with Adidas. Further, Mr Grover’s views, acting in his capacity as general counsel of Pacific Brands, with respect to adidas’ allegations are set out in correspondence with adidas’ legal advisors and require no elaboration.

123 The various informal and formal undertakings given by Pacific Brands to adidas in relation to each of the shoes the subject of complaint by adidas prior to adidas commencing proceedings on 18 October 2010 (Exhibits C to N inclusive) were evidence of Pacific Brands’ decision to resolve adidas’ complaints on pragmatic, commercial terms and not an acceptance of trade mark infringement nor, as adidas contended for, evidence of Pacific Brands’ intention to “sail close to the wind”. Pacific Brands’ decision to provide such undertakings should be considered against the fact that Pacific Brands, at the relevant time, was selling many millions of shoes per annum.

124 As to Mr Frank Zheng, he was no longer an employee of Pacific Brands. There was no evidence that Mr Zheng was involved in any conduct which gave rise to any finding of intention on the part of Pacific Brands to deceive or confuse any consumers into associating the impugned shoes with adidas.

125 As to Mr Pat Maher, he was no longer an employee of Pacific Brands. There was no evidence that Mr Maher was involved in any conduct which gave rise to any finding of intention on the part of Pacific Brands to deceive or confuse any consumers into associating the impugned shoes with adidas.

126 Adidas’ late assertion of Pacific Brands’ intention to “sail close to the wind” was a desperate attempt to try and shore up its hopeless application for a permanent injunction with respect to four stripes on the sides of shoes.

127 Turning to the applicants’ case on intention, the respondent submitted that adidas’ intention case was fundamentally tied to an alleged “Respondent’s Strategy” (Strategy). The Strategy was not supported by evidence but built on assumption and inference. The emotive language deployed was an unsuccessful attempt to fill the gaps in the evidence.

128 Setting aside the logical conclusion that if there was no Strategy there was no Strategy to manage, the assertion that it was evident that Mr Grover managed the Strategy was on no view of the documents referred to made out. His involvement in relation to stripe placement was confined to providing an opinion about the insertion of a horizontal tab into the Boston shoe to deal with the fact that Pacific Brands was left with 13,000 pairs of shoes after Payless cancelled its order.

129 Pacific Brands proffered various undertakings in relation to a very small number of shoes (particularly when considered in the context of the millions of shoes it sold each year) between 2006 and when adidas commenced these proceedings on 18 October 2010. This was not evidence of the Strategy adidas contended for but a pragmatic commercial response to episodic shoes that formed a very small part of Pacific Brands’ business. There was no basis to cast Pacific Brands’ refusal to give a broad undertaking regarding four stripes in any light other than its appreciation that adidas had 3 stripe marks which do not confer rights regarding the use of four stripes generally, particularly in circumstances where Pacific Brands considered its own use of four stripes as decorative or functional and not deceptively similar to the 3-Stripe Trade Marks.

130 The insertion of the tab in the Boston Shoe was not properly characterised as “agonising over the shift from the Boston (Exhibit G) to the Apple Pie and Stingray runners (Exhibit H, Exhibit I)”. There was no design evolution occurring that accorded with any prevailing strategy. It was, at first, Pacific Brands assisting its client Payless to alter the Boston Shoe, with the assistance of one of its manufacturers, in the face of the adidas’ claims of infringement – the various options were devised to come up with something that Payless would accept, not any evidence of Pacific Brands trying to “sail close to” the 3-Stripe Marks. The correspondence then recorded a pragmatic response from Pacific Brands to being left with the stock Payless ordered but ultimately refused to accept delivery of.

131 No letter of demand was ever sent to Pacific Brands in relation to the Airborne Shoe prior to the current proceedings being commenced. A letter of demand was sent to Pacific Brands’ retailer, John’s Shoes, and upon notification of that letter, Pacific Brands assisted adidas with its enquiries. In a letter dated 16 September 2010, Pacific Brands confirmed to adidas’ legal representatives that it was the supplier of Airborne, it had not imported the shoe since about 2006 or earlier and had no intention of doing so in the future. The letter concludes “In the circumstances, I trust that we can finalise this matter on this basis”. No further correspondence was received from adidas’ legal representatives until the current proceedings were commenced on 18 October 2010. Accordingly, there was no basis for the statement that this was “in keeping with its strategy”.

132 Approaching these issues chronologically, my findings are as follows.

Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D

133 In relation to the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D there is a letter dated 8 August 2005 to the managing director of Pacific Brands (UK) Ltd referring to shoes and photographs of those shoes from which it is impossible to discern what those shoes are. The letter also refers to registered trademarks in the United Kingdom. The reply from Pacific Brands (UK) Ltd is dated 26 January 2006. The shoe in question has some similarity with the Airborne Shoe - Exhibit E as far as can be discerned from the reproductions annexed to that letter.

134 The letter evidences an agreement between Pacific Brands (UK) Ltd undertaking to cease to deal in the United Kingdom in those shoes in the photographs attached to the letter but also undertaking to cease to deal with any articles of footwear which bear three or four parallel stripes which are: on the side of the footwear extending forward from the sole to the normal position of the lacing or other means of closure; and in a colour or colours or material which contrasts with the colour or material of the part of the footwear on which such stripes are located; and each of the same, or substantially the same, width and which are either equally, or substantially equally, spaced. I note that Mr Grover became aware of this correspondence in July 2006 when it was brought to his attention by the solicitors for the applicants.

135 There is further email correspondence in November 2005 about what is now called the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D. There is a reference to legal issues in New Zealand but there is no evidence as to the strength or weakness of those legal issues or to their resolution. I regard this material as of no significance. I reach the same conclusion about the email correspondence dated 22 November 2005 and the material which reproduces an email of 23 November 2005 and an email dated 5 December 2005.

Apollo Shoe - Exhibit C and the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D

136 More immediately relevant correspondence is to be found beginning with a letter dated 13 June 2006 from the applicants’ solicitors. That letter concerned what is now referred to as the Apollo Shoe - Exhibit C and the Indigo Shoe - Exhibit D. The letter requested that Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd immediately cease supplying those goods “and any other footwear goods in relation to which any 3-stripes mark, or any mark substantially identical or deceptively similar to any 3-stripes mark is used without the licence of Adidas” and to deliver up any infringing goods et cetera.