RPL Central Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2013] FCA 871

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 30, “208” has been replaced with “218” |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

RPL CENTRAL PTY LTD (ACN 136 181 989) Applicant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and file a jointly prepared minute of order (including as to costs) giving effect to these reasons for judgment by 4:00 pm on 13 September 2013, or, if the parties cannot agree, each file and serve such a minute of order by this time.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 817 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | RPL CENTRAL PTY LTD (ACN 136 181 989) Applicant |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS Respondent |

JUDGE: | MIDDLETON J |

DATE: | 30 August 2013 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 The principal question for determination in this appeal is whether the invention that is the subject of Australian Innovation Patent No. 2009100601 (entitled “Method and System for Automated Collection of Evidence of Skills and Knowledge”) (‘Patent’) is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’).

2 The procedural history of this appeal has no significance, other than insofar as this proceeding is an appeal from a decision by the Commissioner of Patents (‘Commissioner’) to the effect that none of the claims of the invention constitute a manner of manufacture (but that they are novel and inventive). This proceeding initially involved another party who was opposing the grant of the Patent. That party withdrew from this proceeding shortly after its commencement. The Commissioner was then substituted as respondent to the proceeding.

3 It is convenient to commence by setting out how the invention works, as described in the Patent.

THE CLAIMED INVENTION

4 Broadly, the claimed invention relates to the assessment of the competency or qualifications of individuals with respect to recognised standards. The Patent specification sets out the background to the invention. For convenience, I reproduce the key elements of that material here.

Background

5 By way of specific example, the specification refers to the system for Recognition of Prior Learning (‘RPL’) within the Australian Vocational Education and Training (‘VET’) sector. However, despite being particularly well-suited to achieving improvements within this system, the specification states that the invention is not necessarily limited to this application.

6 Currently in Australia, a prospective student can complete a training course at a Registered Training Organisation (‘RTO’) or a College of Technical and Further Education (‘TAFE’) in order to gain a nationally accredited Unit of Competency certificate, diploma or advanced diploma qualification. It is also possible, although less common, for an individual to request that an RTO or TAFE assess their current competency relative to the requirements of such a training course, so as to determine whether they are entitled to obtain the qualification without participating in the course. This is known as the “RPL process”.

7 In order to complete the RPL assessment, a training organisation (eg an RTO or TAFE) assesses evidence of an individual’s competency to determine whether they are able to meet the requirements, skills, knowledge or other expectations of a person who has completed the equivalent training course, or who has gained relevant practical experience in the workforce. If so, the individual may be awarded the equivalent qualification, or Statement of Attainment, by the training organisation.

8 However, for individuals there are a number of barriers to access to the RPL processes within the existing VET system. One is that there is no single point of access to RPL in Australia. This is because a training organisation, such as an RTO or TAFE, is only legally entitled to issue a qualification or Statement of Attainment if that organisation has been approved to deliver and assess the corresponding training course or unit and this is specified in the scope of its registration. Since there are currently in excess of 3,500 qualifications and 34,000 units in the Australian VET sector, any individual training organisation may only be able to offer and assess a very small subset of these qualifications or units. Consequently, it is said to be difficult for an individual to identify a particular qualification to which they may be entitled under an RPL program, along with an institution or organisation that is able to perform the required RPL assessment.

9 Further, the specification notes that the primary business function of RTOs and TAFEs is the provision of education or training – not the evaluation of the existing competencies of prospective students. As such, it is said that RPL is viewed by such institutions largely as an occasional and inconvenient occurrence. The onus is on a prospective student to seek out a relevant provider, and to negotiate their own way to recognition of their existing competencies via the RPL processes.

10 Accordingly, an objective of the invention is to provide an improvement to the existing situation through technological means. In particular, the invention recognises the need for an automated tool that can facilitate the centralised collection of assessment information from individuals, and provide improved access to RPL processes independently of the particular organisation (eg the RTO or TAFE) that is chosen to issue a corresponding qualification or Statement of Attainment.

The description of the invention

11 The specification states that embodiments of the claimed invention are advantageously able to automate the process of converting assessable criteria, possibly relating to many thousands or tens of thousands of training courses and units, into a more convenient “question and answer” format that is then able to guide an individual through the information gathering process. The responses of an individual to the automatically-generated questions may be collated and, for example, stored in a database. From there, they may be provided (with or without further processing) to a relevant training organisation for the purposes of assessing the individual’s competency relative to the recognised qualification standard.

12 For an individual user, the embodiments of the claimed invention provide a single entry point from which they are able to identify or select specific relevant qualifications and units, provide information and evidence relevant to existing competencies, and initiate a recognition process, in a manner that is independent of the institution that is ultimately selected to perform the assessment or to issue a qualification.

13 The specification notes that within the context of the Australian VET sector, the recognised qualification standard may include one or more so-called ‘Units of Competency’ registered with the Australian National Training Information Service (NTIS) or its equivalent at some future time, and associated with formal qualifications, such as a Certificate, Diploma or Advanced Diploma. In this context, the “assessable criteria” may include elements of competency or performance criteria that are associated with the Units of Competency.

14 In what is described in the specification as “a particularly preferred embodiment”, the steps of presenting the automatically-generated questions to the individual and receiving a corresponding series of responses are performed via an automated computer interface, such as a web-based interface or a standalone computer interface. A web-based approach is said to be particularly advantageous, as it provides for easy centralised access to assessment, independent of the geographical location of either the individual requesting assessment, or the training organisation or institution ultimately selected to perform the assessment. Preferably, the computer interface enables the individual user to provide a text-based response or to upload supporting documentation in response to each automatically-generated question.

15 Preferred embodiments of the invention are described in the specification by reference to a number of accompanying drawings:

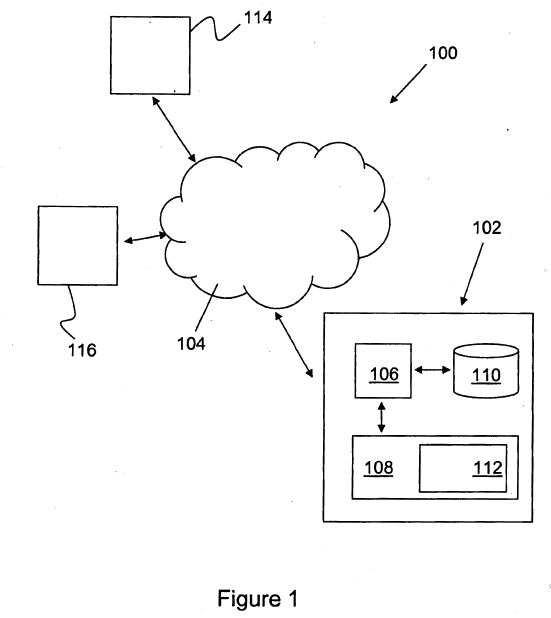

(a) Figure 1, which illustrates “an exemplary system embodying the present invention”;

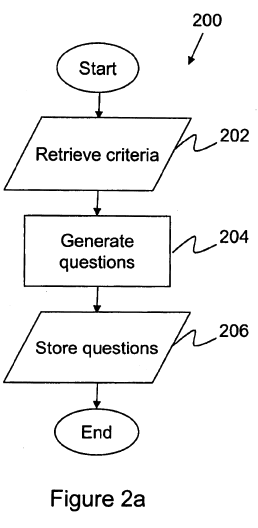

(b) Figure 2a, which is a flowchart illustrating “a preferred method of generating questions from assessable criteria according to the invention”;

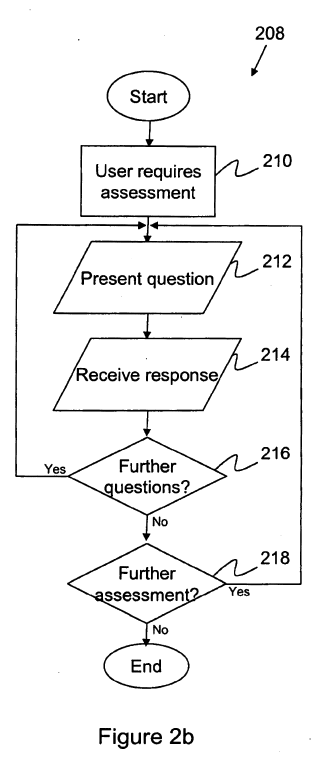

(c) Figure 2b, which is a flowchart illustrating the gathering of information “from an individual according to a preferred embodiment of the invention”;

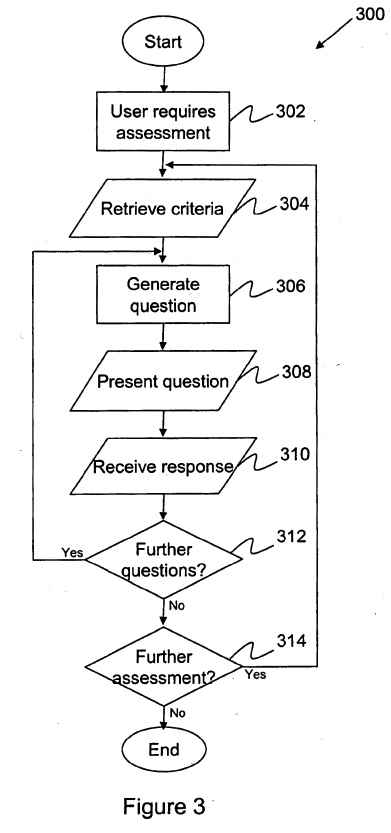

(d) Figure 3, which is a flowchart illustrating “an alternative method for generating questions and gathering information according to an embodiment of the invention”;

(e) Figure 4, which illustrates an “example of assessable criteria”;

(f) Figure 5, which schematically depicts an “exemplary user interface for gathering information from a user”; and

(g) Figure 6, which is a flowchart illustrating “a method of performing an assessment of competency utilising an embodiment of the invention”.

16 Figure 1 of the Patent illustrates “an exemplary system 100 within which the present invention may be embodied”. It is convenient to reproduce that figure here.

17 The system (globally denoted by the label ‘100’) includes a server computer (denoted by the box labelled ‘102’) known as the “assessment server”, which is configured to gather information relevant to an assessment of an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard. In the preferred embodiment, the assessment server is configured to gather information for use in an RPL process within the Australian VET sector. The assessment server is connected to the internet (denoted by the shape labelled ‘104’) in what is described in the specification as a conventional manner, in order to enable remote access by users and to provide the assessment server with access to related online resources.

18 The assessment server includes at least one processor (denoted by the box labelled ‘106’), which is associated with random access memory (or ‘RAM’, denoted by the box labelled ‘108’), used for containing program instructions and transient data related to the operation of the services provided by the assessment server. The RAM contains a body of program instructions (denoted by the box labelled ‘112’) implementing a method of gathering information relevant to the assessment of a user’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard. Additionally, this body of program instructions also includes instructions for providing a web-based interface to the assessment service, enabling users to remotely access the service from any client computer executing conventional web browser software.

19 The processor is also operatively associated with a further storage device (denoted by the shape labelled ‘110’) such as a hard disk drive, which is used for long-term storage of program components and data relating to recognised qualification standards, as well as information gathered from users.

20 The system also includes a remote server computer (denoted by the box labelled ‘114’) which is accessible via the internet, and which contains information relating to recognised qualification standards. In the preferred embodiment, the server is a web server operated by or on behalf of the NTIS (‘NTIS server’), which provides information pertaining to recognised qualification standards in the form of the aforementioned Units of Competency that are registered with the NTIS. Each Unit of Competency is associated with a number of assessable criteria, in the form of elements of competency and related performance criteria. The assessment server is therefore able to retrieve information regarding the elements of competency and performance criteria via the internet from the NTIS server.

21 Nationally accredited Units of Competency registered with the NTIS generally comprise a number of elements of competency, each of which are associated with a number of performance criteria. For example, an element of competency for a particular unit relating to aged care may be to “demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector”. A specific performance criterion associated with this element may be that “all work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers”. The specification states that, as is appropriate for criteria associated with accredited training programs, the elements of competency and performance criteria are generally outcome-orientated. As such, they are not particularly “user friendly” from the perspective of an individual attempting to navigate their own way toward formal recognition of their existing competencies.

22 The specification states that in accordance with embodiments of the invention, it is therefore desirable to convert the elements of competency and associated performance criteria into a more user-friendly form. The invention does this by leading an individual user through a series of questions designed to gather information relevant to the assessment of their competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, ie one or more Units of Competency. When provided via a computer interface, such a step-by-step, form-based implementation is commonly known as a “wizard”. It is further considered desirable, in accordance with embodiments of the present invention, to automate the process of wizard generation to the greatest extent possible, in view of the large number of qualifications and units currently registered in the Australian VET sector. The manual generation of corresponding wizards is therefore said to be impractical.

23 A function of the assessment server is therefore to convert the elements of competency and performance criteria into a suitable “question and answer” form.

24 To this end, the specification sets out how the outcome-oriented elements of competency and performance criteria may be converted into corresponding questions for inclusion in the wizard. In a preferred embodiment, the statement corresponding with the element of competency relating to aged care (previously noted) may be converted into the question: “Generally speaking and based upon your prior experience and education, how do you feel you can demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector?”. Similarly, the statement associated with the corresponding performance criterion may be converted into the question: “How can you show evidence that all work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers?”. User responses to these questions may include text-based responses and supporting documentation, which may be, for example, uploaded to the assessment server. Supporting documentation may consist of electronic text documents (including scanned paper documents), images, or audio-visual or other multimedia documents.

25 The next figure described in the specification is Figure 2a, which comprises a flowchart illustrating a method of generating questions from assessable criteria (ie elements of competency and performance criteria) according to the preferred embodiment.

26 At the step designated ‘202’, the assessment server already referred to in the context of the discussion of Figure 1 retrieves assessable criteria from the NTIS server. At the step designated ‘204’, each of the assessable criteria is processed in order to generate a corresponding set of user-friendly questions (that may be incorporated into a wizard format). At the step designated ‘206’, the resulting questions are stored (for example, on the storage device previously mentioned in the context of Figure 1).

27 In the particular embodiment represented by this figure, it is envisaged that the complete set of assessable criteria associated with a particular qualification standard (ie Unit of Competency) is retrieved and processed in order to generate the corresponding questions in advance of an individual user seeking corresponding assessment.

28 However, the specification makes clear that alternative implementations are possible, including but not limited to the alternative set out in Figure 3, in which questions are generated from the assessable criteria upon demand (described further below).

29 Figure 2b follows on from Figure 2a, and comprises a flowchart illustrating the subsequent gathering of information from an individual using the questions stored at step 206 illustrated in Figure 2a.

30 At the step designated ‘210’, a user accesses the assessment server via the internet using their computer. Having identified a particular Unit of Competency in relation to which assessment is desired, at the step in this figure designated ‘212’, the user is presented with the first question, to which a response is provided at the step designated ‘214’. In accordance with the “decision step” designated ‘216’, while there are further questions associated with the Unit of Competency, steps 212 and 214 are repeated. At the step designated ‘218’, the user may request further assessment (for example in relation to a different Unit of Competency), or choose to terminate the process.

31 As previously indicated, Figure 3 is a flowchart illustrating an alternative method for generating questions and gathering information from an individual relevant to an assessment of that individual’s competency, relative to a recognised qualification standard. The method represented by this flowchart differs from that depicted in Figures 2a and 2b in that questions are generated and presented to the user on demand, rather than being generated and stored in advance for later presentation.

32 In Figure 3, at the step designated ‘302’, a user desiring an assessment of competency accesses the assessment server via the internet from a user computer (in the same manner as depicted in Figures 2a and 2b). Once the user has identified a relevant Unit of Competency, the assessment server proceeds to generate and present questions to the user based upon the assessable criteria (consisting of the elements of competency and performance criteria associated with the Unit of Competency).

33 At the step designated ‘304’, one or more assessable criteria are retrieved. At the step designated ‘306’, a question is generated based upon the first retrieved criterion. At the step designated ‘308’, the question is presented to the user, and a response is received at the step designated ‘310’. If it is determined at the step designated ‘312’ that there are further criteria to be assessed, then steps 306, 308 and 310 are repeated until no criteria remain. At the so-called “decision step” designated ‘314’, if the user wishes to provide information relevant to a further assessment in relation to one or more additional Units of Competency, then the method returns to step 304. Otherwise, the process terminates. User responses (including text-based responses to questions and uploaded supporting documentation) may be stored by the assessment server within the storage device.

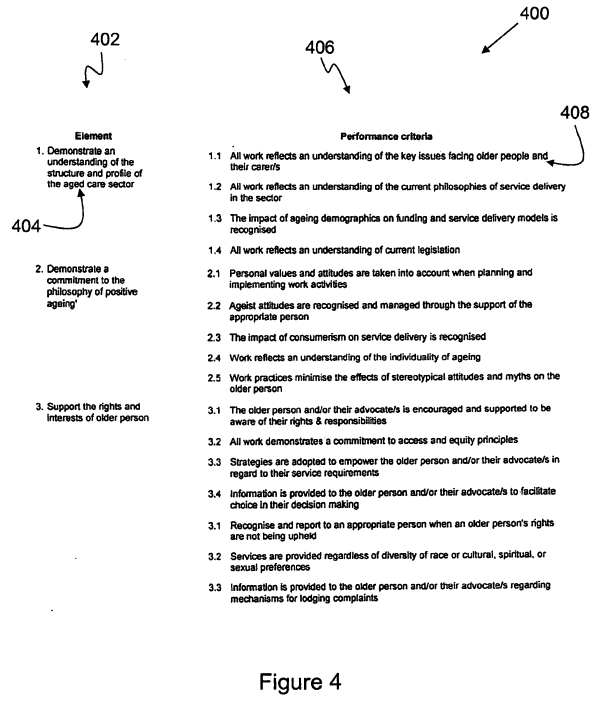

34 Figure 4 contains an excerpt from the assessable criteria, ie elements of competency and performance criteria associated with a particular Unit of Competency. The Unit of Competency includes a number of elements of competency, listed in the column designated ‘402’. Associated with each element of competency there is a corresponding group of performance criteria, listed in the column designated ‘406’. For example, one element of competency is “Demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector” (designated ‘404’ in Figure 4). The associated performance criteria (designated ‘408’) include “All work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers”; and “All work reflects an understanding of the current philosophies of service delivery in the sector”.

35 The specification notes that within the Australian context, the elements of competency and performance criteria are presently made available for download from the NTIS server, which is accessible via the URL http://www.ntis.gov.au. The NTIS server provides a search facility for identifying and accessing Units of Competency. Accordingly, in the context of the invention, the assessment server is able to identify and download the assessable criteria associated with any desired Unit of Competency.

36 Figure 5 illustrates the first three question and response forms of a wizard that may be automatically generated (in accordance with an embodiment of the invention) from the assessable criteria illustrated in Figure 4.

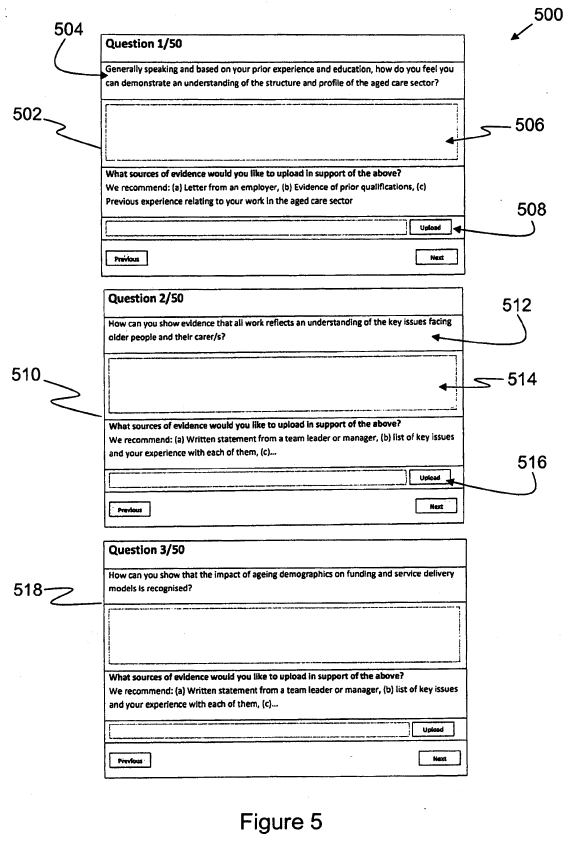

37 The first wizard form (designated ‘502’) presents the first automatically generated question based upon the first element of competency (designated ‘504’), which consists of the text, “Generally speaking and based on your prior experience and education, how do you feel you can demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector?”. A text box (designated ‘506’) is provided, into which the user may enter a text-based response to the question. In addition, the wizard form designated ‘502’ recommends that the user provide evidence supporting the response, such as a letter from an employer (facilitated by the upload facility designated ‘508’, which enables users to specify files stored on their local computer to be transferred to the assessment server as part of their response to the question).

38 The second wizard form (designated ‘510’) presents a question designated ‘512’ based upon the first of the performance criteria set out in Figure 4, being: “How can you show evidence that all work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers?”. Again, a text field (designated ‘514’) is provided for the user to enter a text-based response to this question. This wizard form also recommends providing evidence in support (for example, in the form of a written statement from a team leader or manager), and again, an upload facility (designated ‘516’) is provided to enable the user to specify documents stored on their local computer to be transferred to the assessment server. The third wizard form (designated ‘518’) has a similar form (and therefore need not be considered further).

39 The specification notes that more sophisticated templates and text processing may be employed within the scope of the invention. For example, questions may be formed based upon the identification of particular keywords or concepts appearing within the individual assessable criteria, or additional contextual information may be employed in the formulation of questions. Some processing may involve a degree of human expert input – for example, in reviewing or amending questions automatically generated using a fully computer-implemented process.

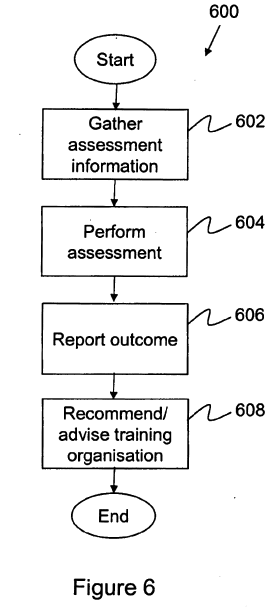

40 The specification states that while the invention is primarily concerned with the gathering of information relevant to the assessment of an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, it is an objective of embodiments of the invention to facilitate improvements in the overall RPL process. One possible manner in which this objective may be achieved is illustrated in Figure 6.

41 In the process exemplified in this flowchart, assessment information is gathered from an individual at the step designated ‘602’, utilising an embodiment of the invention. The assessment server may retain stored information regarding particular training organisations (eg RTOs and TAFEs) that provide training in particular units within the scope of their registration. This information may be retrieved from other sources, such as the NTIS server. Accordingly, the assessment server is able to identify one or more training organisations that are competent to provide RPL in relation to the units in respect of which the individual user has provided assessment information. The assessment server may therefore advise the user of the identified training organisations, or facilitate the submission of the assessment information to a relevant training organisation for RPL purposes.

42 At the step designated ‘604’, an RPL assessment is performed by a relevant training organisation. At the step designated ‘606’, the outcome of the assessment is reported. The reporting may be an ‘off-line’ process, for example, via direct interaction between the individual and the relevant training organisation, or it may be facilitated via the assessment server. The specification suggests that the assessment server may provide a single central point of contact between individuals and training organisations, thereby providing a valuable service to all parties. Individuals are provided with a service which simplifies the identification of relevant Units of Competency, and the gathering of associated assessment information to enable RPL to be performed. Training organisations are relieved of much of the administrative cost associated with performing RPL. By the time the training organisation is contacted, the relevant Unit of Competency has already been identified, and required information associated with each of the assessable criteria has already been gathered and packaged in a form enabling an efficient assessment in relation to the RPL process.

43 Further, at the step designated ‘608’, the assessment server may be configured to recommend or advise the individual user of one or more relevant training organisations able to provide appropriate RPL and training services. For example, if – following an RPL assessment – a training organisation finds that the individual is not qualified to receive a qualification or Statement of Attainment, the individual may be offered the option to attain the relevant qualification by attending a training course offered by the training organisation. In this way, the specification states, the services provided by the assessment server may also contribute to the core business of training organisations.

44 In summary, embodiments of the invention facilitate improvements in existing RPL processes, by enabling the automated generation of a wizard or similar user interface to perform the administrative work necessary to gather evidence from a prospective candidate which is relevant to any qualification or unit offered across a wide range of training organisations. In various embodiments, the invention facilitates the assessment of the competencies of individuals, the issuing of qualifications, and the proactive recommendation of suitable pathways, including relevant courses of further training, based upon the identified competencies of individual users. Although the specification primarily focuses on ‘online’ implementation of these functions, it notes that alternative mechanisms for presenting automatically generated questions and receiving responses (such as presentation in a form suitable for ‘offline’ completion, like PDF files) may also be employed.

The claims

45 The specification concludes with five claims, of which only claims 1 and 5 are independent. Claims 1 to 4 expressly require as an essential feature the operation of the method on a computer processor. Claim 5 – a claim to a system – embodies a physical system capable of the requisite operation. Claims 2 to 4 depend on claim 1, and narrow it by adding further integers. RPL submitted that analysis of the invention is most aptly considered by reference to the broadest claims (namely, claims 1 and 5) and their express wording. It was further submitted that if claim 1 does not fulfil the relevant requirements, then the Court would need to go on and also consider the subsidiary claims 2 to 4. Accordingly, at this point I set out only claims 1 and 5 in full.

46 Claim 1 relates to a method of gathering evidence for the purpose of assessing an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, which includes the following steps:

(a) a computer retrieving via the internet from a remotely-located server a plurality of assessable criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard, said criteria including one or more elements of competency, each of which is associated with one or more performance criteria;

(b) the computer processing the plurality of assessable criteria to generate automatically a corresponding plurality of questions relating to the competency of an individual to satisfy each of the elements of competency and performance criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard;

(c) an assessment server presenting the automatically-generated questions via the internet to a computer of an individual requiring assessment; and

(d) receiving from the individual via their computer a series of responses to the automatically-generated questions, the responses including evidence of the individual’s skills, knowledge and experience in relation to each of the elements of competency and performance criteria, wherein at least one said response includes the individual specifying one or more files on their computer which are transferred to the assessment server.

47 Claim 5 relates to a system for gathering evidence for the purpose of assessing an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, such system including:

(a) at least one server computer having a microprocessor, an associated memory or storage device, and a network interface providing access to the internet;

(b) the memory or storage device including a data store which contains a plurality of questions relating to the competency of the individual to satisfy each of a plurality of assessable criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard, said criteria including one or more elements of competency, each of which is associated with one or more performance criteria, wherein the assessable criteria are retrieved via the internet from a remotely-located server and the questions have been automatically-generated by computerised processing of said elements of competency and performance criteria; and

(c) the memory or storage device further including instructions executable by the microprocessor such that the server computer is operable to:

(i) present the questions via the internet to a computer of an individual user;

(ii) receive from the individual user via their computer a series of responses to the questions, such responses including evidence of the individual’s skills, knowledge and experience in relation to each of the elements of competency and performance criteria, wherein at least one said response includes the individual specifying one or more files stored on the individual’s computer for transfer to the server computer; and

(iii) store the responses of the individual user within the associated memory or storage device.

PRELIMINARY ISSUE

48 In her submissions, the Commissioner set out a number of authorities detailing the parameters of her role in appeals of this kind. It is not necessary to exhaustively reproduce those submissions here. Rather, it is sufficient to note the following.

49 As a general rule, an administrative decision-maker should not take an active role in an appeal against their decision, in the sense of seeking to present a substantive argument on appeal in support of their decision: R v Australian Broadcasting Tribunal; ex parte Hardiman (1980) 144 CLR 13 at 35-36.

50 In Merck & Co Inc v Sankyo Co Ltd (1992) 23 IPR 415, Lockhart J considered the right of the Commissioner to appear and be heard pursuant to r 3 of O 54B of the Federal Court Rules 1979 (Cth) (as were then in force), s 149 of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) and s 159 of the Act. His Honour noted that the comments of the High Court in Hardiman (1980) 144 CLR 13 are “a salutary reminder that there are difficulties in allowing the commissioner to pursue an active role in the conduct of… an appeal to the court from his own decision or direction (r 3 or s 159) or from his own determination (r 3)” (at 417-418). His Honour further observed (at 418):

The commissioner should be heard fully on questions concerning his powers and procedures. His role should be limited when the parties to the proceeding are before the court and each pursues an active role. His role would then be akin to an amicus curiae. But if a party does not appear or does not argue his case before the court, the commissioner should, speaking generally, be allowed more latitude by the court with respect to the issues which he wishes to address and the extent to which he seeks to present a case. Ultimately it is for the court to control the proceeding before it.

51 The role assumed by the Commissioner in an appeal to this Court is influenced by the public interest in ensuring that patent applications that would be clearly invalid if ultimately granted are not put on the register. Justice Emmett described this public interest at 66 [46] in F Hoffman-La Roche AG v New England Biolabs Inc (2000) 99 FCR 56 in the following manner:

There is of course a very significant public interest in ensuring that patents which could not be valid should not be permitted to go on to the register. There is a public interest in ensuring that monopoly is afforded only to patents that are valid. Further, there is a public interest in ensuring that no applicant for a patent should be put in a position to make threats of infringement in respect of a patent that would clearly be revoked in revocation proceedings.

52 On this basis and having regard to the fact that the Commissioner is now the only party before the Court as a contradictor, I accept that it is appropriate for the Commissioner to take the active role that she has adopted to date, which has included making substantive submissions on whether the invention in question is properly a manner of manufacture.

RELEVANT LEGAL PRINCIPLES – MANNER OF MANUFACTURE

53 Whether the claimed invention constitutes a manner of manufacture is the principal issue regarding the validity of the Patent that falls for determination in this proceeding. The invention that is the subject of the Patent has otherwise been found to be novel and inventive.

54 The basic requirements of patentability are set out in s 18 of the Act. Section 18(1A)(a) relevantly provides that an invention is patentable for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (Imp) (‘Statute of Monopolies’). This is a threshold requirement for patentability, “capable of solution upon a study of the specification itself” (CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 at 291 (‘CCOM’), citing Compagnies Reunies des Glaces et Verres Speciaux du Nord de la France Application (1931) 48 RPC 185 at 188).

55 ‘Invention’ is defined in the Dictionary contained in Schedule 1 to the Act as “any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention”.

56 Section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies provides that the declarations of invalidity contained in the preceding provisions of that Act:

shall not extend to any [letters patent] and Graunte of Privilege… hereafter to be made of the sole working or makinge of any manner of new Manufactures within this Realme, to the true and first Inventor and Inventors of such Manufactures, which others at the tyme of makinge such [letters patent] and Graunte shall not use, soe as alsoe they be not contrary to the Lawe nor mischievous to the State, by raising prices of Comodities at home, or hurt of Trade, or generallie inconvenient...

57 The Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia in CCOM chronicled the development of this ground of invalidity in patent law in a passage that merits repetition (at 290):

the phrase “any manner of new manufactures” [the phrase that appears in s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies] has been interpreted over time in such a way as to contain within it distinct principles or doctrines concerned with patentability: Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd v Ramset Fasteners (Australia) Pty Ltd (1993) 26 IPR 171 at 188-190, per Hill J. They include the necessity for a manner of manufacture itself, for novelty, and for inventiveness. Objections such as lack of utility may have been derived from the prohibition upon manufactures which are “generally inconvenient”. Others, such as obtaining by false suggestion, derived from the general law attending the writ of scire facias to recall Crown grants and the Chancery jurisdiction in respect of fraudulent grants: Prestige Group (Australia) Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1990) 26 FCR 197 at 213-219. The essential point is that the grounds of revocation were capable of development by the common law and did so develop: American Cyanamid Co (Dann’s) Patent [1971] RPC 425 at 435-436 (Lord Reid), 448-449 (Lord Wilberforce).

Particular grounds of invalidity, derived from the case law, were added to the modern statutes. Lack of inventiveness, as distinguished from anticipation, obtained a distinct statutory recognition only in this century and, in Australia, in the 1952 Act: R D Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd (1989) 25 FCR 565 at 573-584, 591-602. As this development continued, the phrase “manner of new manufactures” came to represent the residuum of the central concept with which NRDC was concerned, namely what the High Court called the relevant concept of invention. It should be noted that in NRDC (at 262) the High Court, which was dealing with the 1952 Act, spoke of the concept of patent law ultimately traceable to the use in 1623 of the words “manner of manufacture” and spoke of novelty and inventive step as distinct matters.

This distinction is now made clear by the use of the expression “manner of manufacture” in s 18 of the 1990 Act. The structure of s 18(1) emphasises that the grounds of novelty, inventive step, utility and secret use are each excised from any general body of case law which previously developed the phrase from 1623 “manner of new manufactures”. The point is made particularly clear by the reference in par (a) of the subsection to “manner of manufacture” rather than to “manner of new manufactures”.

58 Considerable jurisprudence has developed over time to identify the boundaries between inventions falling within the concept of manner of manufacture, and those falling outside it. This development of the law is ongoing, and is often prompted by developments in technology – for example, the advent of computers. However, courts have long determined that some subject matter is not capable of supporting an application for grant of a patent.

59 For example, Sir Robert Finlay AG in the case of Re Cooper’s Application for a Patent (1901) 19 RPC 53 (cited with approval in Grant v Commissioner of Patents (2006) 154 FCR 62 at 66 (‘Grant’)) noted at 54 that a patent cannot be granted in respect of:

a mere scheme or plan – a plan for becoming rich; a plan for the better Government of a State; a plan for the efficient conduct of business. The subject with reference to which you must apply for a Patent must be one which results in a material product of some substantial character. The Specification must show how some such material product is to be realised or effected by the alleged invention.

60 Historically, mere working directions and methods also fell outside the concept of manner of manufacture. The same is true for directions as to how to operate a known article or machine or to carry out a known process so as to produce an old result, even though they may be a different and more efficient method of doing things (Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 113 FCR 110 at 133 [106] (‘Catuity’)). Cases in which patents have been refused on this basis include Rolls-Royce Ltd’s Application [1963] RPC 251 (a method of operating an aircraft engine in such a way as to reduce noise during take off), Re Brown (1899) 5 ALR 81 (an improved method of preventing the fraudulent re-use of sales book dockets), Commissioner of Patents v Lee (1913) 16 CLR 138 (improved methods for charcoal burning), Neilson v The Minister of Public Works for NSW (1914) 18 CLR 423 (improved methods for utilising an existing mechanism of septic tank purification), and Rogers v Commissioner of Patents (1910) 10 CLR 701 (method for felling trees using fire): see Catuity at 133 [106].

61 Also historically rejected were patents for “methods of calculation and theoretical schemes, plans and arrangements” (Catuity at 133 [107]), such as:

a stellar chart for ascertaining the position of an aircraft in flight (Re an Application for a Patent by Kelvin & Hughes Ltd (1954) 71 RPC 103);

a plan relating to the layout of contiguous houses in a row or terrace so as to address the disadvantages typically associated with building houses in such a manner, namely, that they “do not as a rule add to the adornment of a town”, and “they offer but comparatively little privacy, the tenants “being exposed to the eyes of the neighbours on either side”“ (Re an Application for a Patent by ESP (1944) 62 RPC 87);

an arrangement of buoys for navigational purposes (Re an Application for a Patent by W (1914) 31 RPC 141); and

a system of business (the implementation of which involved the use of a printed envelope with a particular arrangement of words: Re Johnson’s Application for a Patent (1902) 19 RPC 56).

See Catuity at 133 [107]; and Grant at 67 [16].

62 The same can be said for processes of mathematical operations, and “printed sheets, cards, tickets or the like which are mere records of intelligence” (see CCOM at 292, citing the comments of Professor James Lahore in his article “Computers and the Law: The Protection of Intellectual Property” (1978) 9 Federal Law Review 15).

63 Against the background of these decisions and the reasons provided in them, the decision of the High Court in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252 (‘NRDC’) provides the principles for determining what constitutes a manner of manufacture.

64 Justice Nicholas in Cancer Voices Australia v Myriad Genetics Inc (2013) 99 IPR 567 at 582-583 summarised the reception of NRDC as follows:

The case was described by Barwick CJ in Joos v Commissioner of Patents (1972) 126 CLR 611 at 616 ; [1972–73] ALR 831 at 833 ; 1A IPR 172 at 174 as a “watershed” in this area of law, and in Grain Pool of Western Australia v Commonwealth (2000) 202 CLR 479 ; 170 ALR 111 ; 46 IPR 515 ; [2000] HCA 14 at [45] (Grain Pool) Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ referred to it as a “celebrated judgment”. As the Full Court (Spender, Gummow and Heerey JJ) explained in CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 at 289; 122 ALR 417 at 444–5; 28 IPR 481 at 508–9:

In Australia, when the 1952 Act was replaced by the 1990 Act, the new British legislation was not followed. There was in s 18(2) an express exclusion from patentable inventions of human beings and biological processes for their generation. Beyond that the legislature left the matter, in terms of s 18(1)(a), to rest with the concept of manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, as developed by the courts, notably in the NRDC case. This was a matter of deliberate legislative choice.

65 Three claims were in issue in NRDC, all of which were method claims relating to eradication of weeds from crop areas containing leguminous fodder crops by application of a known herbicide (which had not previously been known to be effective to treat the particular weeds identified in the claims). In that case, the Commissioner rejected the patent sought, principally on the bases that (a) it merely claimed a new use of a known substance; and (b) there was no manner of manufacture because the use of the composition did not result in a “vendible product”.

66 The High Court in NRDC articulated the “central question” in the manner of manufacture inquiry as being whether the process claimed falls within the category of inventions to which, by definition, the application of the Act is confined (at 268). The High Court noted the fact that ‘invention’ is legislatively defined by reference to the “established ambit of s 6” of the Statute of Monopolies, and stated that (at 269):

[t]he inquiry which the definition demands is an inquiry into the scope of the permissible subject matter of letters patent and grants of privilege protected by the section. It is an inquiry not into the meaning of a word so much as into the breadth of the concept which the law has developed by its consideration of the text and purpose of the Statute of Monopolies… The word “manufacture” finds a place in the present Act, not as a word intended to reduce a question of patentability to a question of verbal interpretation, but simply as the general title found in the Statute of Monopolies for the whole category under which all grants of patents which may be made in accordance with the developed principles of patent law are to be subsumed.

67 The High Court continued:

It is therefore a mistake, and a mistake likely to lead to an incorrect conclusion, to treat the question whether a given process or product is within the definition as if that question could be restated in the form: “Is this a manner (or kind) of manufacture?” It is a mistake which tends to limit one’s thinking by reference to the idea of making tangible goods by hand or by machine, because “manufacture” as a word of everyday speech generally conveys the idea. The right question is: “Is this a proper subject of letters patent according to the principles which have been developed for the application of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies?”

(Emphasis added)

68 This latter question was said to be very different to the former. The High Court noted that a widening conception of the notion of “manufacture” has been a characteristic of the growth of patent law, and it is clear that it encompasses both a process and a product (at 269-270). However, their Honours noted that one unresolved question was “whether it is enough that a process produces a useful result or whether it is necessary that some physical thing is either brought into existence or so affected as the better to serve man’s purposes”.

69 After reviewing a number of United Kingdom and Australian authorities, the High Court stated that (at 271):

[t]he truth is that any attempt to state the ambit of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies by precisely defining “manufacture” is bound to fail. The purpose of s 6, it must be remembered, was to allow the use of the prerogative to encourage national development in a field which already, in 1623, was seen to be excitingly unpredictable. To attempt to place upon the idea the fetters of an exact verbal formula could never have been sound. It would be unsound to the point of folly to attempt to do so now, when science has made such advances that the concrete applications of the notion which were familiar in 1623 can be seen to provide only the more obvious, not to say the more primitive, illustrations of the broad sweep of the concept.

70 The High Court then cited with approval the case of Re an Application for a Patent by GEC (1943) 60 RPC 1. The High Court noted that in that case, Morton J (as his Honour then was) had simultaneously disclaimed any intention of laying down “any hard and fast rule applicable to all cases” and “put forward a proposition which, if literally applied, would have a narrowing effect on the law and indeed has already been found to stand as much in need as the statute itself of a generous interpretation” (NRDC at 271). Justice Morton’s proposition was that a method or process will be a manner of manufacture if it:

(a) results in the production of some vendible product; or

(b) improves or restores to its former condition a vendible product; or

(c) has the effect of preserving from deterioration some vendible product to which it is applied.

71 The High Court then considered a number of United Kingdom authorities dealing with this test. In doing so, the Court referred to Re Virginia-Carolina Chemical Corporation’s Application (1958) RPC 35 at 36, and noted that to fall within the limits of patentability prescribed by the Statute of Monopolies, a process must be one that offers some advantage which is material, in the sense that it belongs to a useful art as distinct from a fine art – namely, its value to the country must be in the field of economic endeavour (at 275).

72 In considering the meaning of the expression “vendible product” as used in the Morton J test, the High Court referred to Re an Application for a Patent by Henry Barnato Rantzen (1947) 64 RPC 63, and suggested that the expression lays “proper emphasis upon the trading or industrial character of the processes intended to be comprehended by the Acts – namely, their “industrial or commercial or trading character”” (at 275).

73 In considering that what is meant by a “product” in relation to a process is only “something in which the new and useful effect may be observed”, the High Court in NRDC stated that (at 276):

[s]ufficient authority has been cited to show that the “something” need not be a “thing” in the sense of an article; it may be any physical phenomenon in which the effect, be it creation or merely alteration, may be observed: a building (for example), a tract or stratum of land, an explosion, an electrical oscillation. It is, we think, only by understanding the word “product” as covering every end produced, and treating the word “vendible” as pointing only to the requirement of utility in practical affairs, that the language of Morton J’s “rule” may be accepted as wide enough to convey the broad idea which the long line of decisions on the subject has shown to be comprehended by the Statute.

74 The High Court concluded that (at 277):

the view which we think is correct in the present case is that the method the subject of the relevant claims has as its end result an artificial effect falling squarely within the true concept of what must be produced by a process if it is to be held patentable. This view is, we think, required by a sound understanding of the lines along which patent law has developed and necessarily must develop in a modern society. The effect produced by the appellant’s method exhibits the two essential qualities upon which “product” and “vendible” seem designed to insist. It is a “product” because it consists in an artificially created state of affairs, discernible by observing over a period the growth of weeds and crops respectively on sown land on which the method has been put into practice. And the significance of the product is economic; for it provides a remarkable advantage, indeed to the lay mind a sensational advantage, for one of the most elemental activities by which man has served his material needs, the cultivation of the soil for the production of its fruits. Recognition that the relevance of the process is to this economic activity old as it is, need not be inhibited by any fear of inconsistency with the claim to novelty which the specification plainly makes. The method cannot be classed as a variant of ancient procedures. It is additional to the cultivation. It achieves a separate result, and the result possesses its own economic utility consisting in an important improvement in the conditions in which the crop is to grow, whereby it is afforded a better opportunity to flourish and yield a good harvest.

75 Finally, in rejecting the Commissioner’s contention that agricultural or horticultural processes are, by reason of their nature, outside the limits of patentable inventions, the High Court commented (at 278):

It must often happen in a sphere of human endeavour as old as that of primary production that a newly-devised procedure amounts to nothing more than an analogous application of age-old techniques; and where that is the case, want of novelty is a fatal objection to a patent. It may be conceded, moreover, that if there were nothing that could properly be called a “product” of the process, even an ingenious new departure would be outside the limits of patentability.

76 These comments were remarkably prescient. In fact, since NRDC was decided, the advent of computer technology has prompted an elaboration of the concept of methods as patentable inventions (see Grant at 67 [17], citing Catuity at 135-136 [118]-[122]).

77 To this end, in 1991, Burchett J delivered judgment in International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1991) 33 FCR 218 (‘IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218’). The invention in that case was described as a method and apparatus for producing a curve image on computer graphics displays. It was objected that claim 1 (which provided for a method of producing a visual representation of a curve image from a set of control points which define the curve, and which are input for each dimension and a number of intervals to the curve to be computed, said method comprising a number of defined steps) did not define a manner of manufacture. Rather, the claim was said to recite a mathematical algorithm, which it then “wholly pre-empted”.

78 In that case, Burchett J emphasised “useful effect” as being important to distinguish between the discovery of a principle of science and the making of an invention (at 224). His Honour applied NRDC, and in doing so, referred to the decision of the Patents Appeal Tribunal in Burroughs Corporation (Perkins’) Application [1974] RPC 147 (‘Burroughs’). Burroughs involved a method of transmitting data over a communication link between a central computer and “slave computers” connected to it. In that case, Graham J (delivering the decision of the Tribunal) referred to the proposition that “claims for a method of operating a computer could not be a manner of new manufacture within the Act since the end product of the method was ‘merely intellectual information’ which does not fall within the meaning of ‘product’ as defined by Morton J” (at 154).

79 Justice Burchett extracted Graham J’s conclusion on this point, to the effect that (at 225 in IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218, citing Burroughs [1974] RPC 147 at 158 and 160-161):

it is not enough to take a narrow and confined look at the ‘product’ produced by a method. Of course, if a method is regarded purely as the conception of an idea, it can always be said that the product of such a method is merely intellectual information. If, however, in practice the method results in a new machine or process or an old machine giving a new and improved result, that fact should in our view be regarded as the ‘product’ or the result of using the method, and cannot be disregarded in considering whether the method is patentable or not.

…

[W]e consider the correct conclusion in the present case is as follows: If a claim, whatever words are used, namely, whether the claim is for example for ‘a method of transmitting data .. .’, ‘a method of controlling a system of computers’ or ‘a method of operating or programming a computer .. .’, is clearly directed to a method involving the use of apparatus modified or programmed to operate in a new way, as the present claims are, it should be accepted ... Claims in this form in truth meet Mr Aldous’ argument that there must be an artificial end product or effect before a method can be patentable. Whether the argument is right or not, there is in fact such an effect in this case.

It is plain that the question of patentability must in every case be considered on the facts before a conclusion can be reached as to whether the claim covers a mere idea or method, or is more than that and results in fact in some improved or modified apparatus, or an old apparatus operating in a novel way, with consequent economic importance or advantages in the field of the useful as opposed to the fme arts.

…

It also follows from what we have said, though this is not strictly necessary for the purposes of our decision, that in our view computer programmes which have the effect of controlling computers to operate in a particular way, where such programmes are embodied in physical form, are proper subject matter for letters patent.

80 Justice Burchett noted that it was not suggested that there was anything new about the mathematics of the invention in the case before him – rather, what was new was the application of the selected mathematical methods to computers (and in particular, the production by computer of the desired curve). His Honour found that (at 226):

[t]his is said to involve steps which are foreign to the normal use of computers and, for that reason, to be inventive. The production of an improved curve image is a commercially useful effect in computer graphics.

81 His Honour considered that such a finding was not precluded by the United States authorities regarding the pre-emption of algorithms relied on in argument before him. His Honour emphasised that the patent was not sought over a mere mathematical formula – rather, the formula was applied to achieve an end, which was the production of the improved curve image. The method of producing such a result by computer was, his Honour held, entitled to patent law protection (at 226).

82 In 1994, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia delivered judgment in CCOM. The invention in that case concerned a character word processor for the storage and retrieval of Chinese language characters. It used a particular method of characterisation of character strokes, applied to an apparatus in such a way that the operation of a keyboard would enable the selection (through a computer) of the appropriate Chinese characters required for word processing in that language. The primary judge held that the invention was not a manner of manufacture.

83 In undertaking the manner of manufacture inquiry, the Full Court characterised their task as one requiring the application of concepts “which have evolved, and are still evolving, in accordance with the classic decision in the NRDC case” (at 289). In such an inquiry, a decision is required as to “what properly and currently falls within the scope of the patent system” (at 291). Insofar as “manufacture” suggests a “vendible product”, the Full Court held that this is to be understood as “covering every end produced or artificially created state of affairs which is of utility in practical affairs and whose significance thus is economic” (at 291).

84 The Full Court in that case specifically addressed the challenges posed to the law of intellectual property by the advent and development of computer technology. They noted that one response to computer technology has been to make provision for it in copyright law – but this response has been subject to criticism on a number of bases, for example, on the basis that functionality is not a proper object of copyright protection (see further CCOM at 291-292).

85 The Full Court then reviewed a number of publications and United Kingdom authorities on point (about which more will be said in due course), and noted the trend in other jurisdictions (not replicated in Australia) to exclude computer programs from patent protection (at 292-293). For example, the Full Court discussed a number of English cases that were decided after NRDC, but before the enactment of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) (which, unlike the patent law legislation in Australia, expressly excluded business methods and computer programs from the ambit of patentability). The Full Court opined that “there is significant guidance to be obtained from the course of decisions in Britain before the new legislation with the application in this field of the principles expounded in the NRDC case” (at 293).

86 One of these cases was Burroughs [1974] RPC 147, which, as previously noted, was considered and approved by Burchett J in IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218. Another was International Business Machines Corporation’s Application [1980] FSR 564 (‘IBM [1980] FSR 564’), which concerned a computer program intended to automatically calculate the selling price of shares by comparing buying and selling orders. The Patents Appeal Tribunal acknowledged that a completely standard computer made and sold by IBM could be programmed to perform the invention (to this end, I note that IBM submitted in opposition to the validity of the patent in that case that “even on the assumption that the idea is new and not obvious it does not become a manner of manufacture if you do no more than call in the aid of an ordinary computer to do the work for you”: at 568). But ultimately the Tribunal held that what was claimed by the patent was a manner of manufacture, in the sense that it was a method involving the operation or control of a computer such that it was programmed in a particular way to operate in accordance with the inventor’s method. It was held that the invention involved more than mere intellectual information (in contrast to those cases where a patent was sought over an algorithm alone, as discussed in IBM [1980] FSR 564 at 572).

87 The Full Court in CCOM rejected the submission that all that had been done in respect of the invention in issue was to select “a desirable characteristic of a computer program, the ability to search, in the manner described, a data base of the type described, and “to claim all computers present and future possessing that characteristic”” (at 294). The Court concluded (at 294-295):

That submission should not be accepted. It may be that such a claim lacks novelty, is obvious, or lacks utility, or there is a failure to comply with one or other of the limbs of s 40 because, for example, the invention is not fully described or the claim is not clear and succinct. But if such hurdles all are surmounted, then in our opinion in a case such as the present there does not remain an independent ground of objection as to patentability, within the sense of s 18(1)(a) of the 1990 Act.

88 The invention in CCOM was held to be a manner of manufacture in the sense articulated by NRDC – namely, a mode or manner of achieving an end result which is an artificially created state of affairs of utility in the field of economic endeavour (at 295). The relevant field of economic endeavour in CCOM was held to be the use of word processing to assemble text in Chinese language characters. The end result achieved was held to be the retrieval of graphic representations of desired characters, for assembly of text. And finally, the mode or manner of achieving this (which was said to provide particular utility in achieving the end result) was held to be the storage of data as to Chinese characters analysed by stroke-type categories, for search including “flagging” (and “unflagging”) and selection by reference thereto.

89 Subsequently, in 2001, Heerey J delivered judgment in Catuity. The invention in issue was a process and device for the operation of smart cards (being cards containing a microprocessor or chip with the capacity to store and receive information) in connection with traders’ loyalty programs, which enable traders to promote goods or services by offering rewards to consumers based on prior transactions. The invention incorporated the ability to dynamically store each merchant’s loyalty program in a separate record of a file called the “Behaviour file”, which process occurs at a point of sale terminal the first time that a cardholder uses the card at that merchant’s store. In contrast to the prior art, behaviour information and points for merchants never visited by the cardholder were not added to the card. It was said that this approach allowed chip cards with a small memory capacity to be used with thousands of merchants, each operating their own loyalty program.

90 The respondents in that case submitted that working directions and methods of doing things – of which the invention was said to be an example, using well-known integers including a chip card, the memory space of such a card, and various computer programs to operate familiar kinds of loyalty and incentive schemes for customers – fall outside the concept of manner of manufacture.

91 They sought to distinguish both IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218 and CCOM on the basis that in each of those cases, there was “a physically observable effect that met the manner of manufacture requirement: the screen curve in International Business Machines and the retrieval to graphical representations of desired characters for the assembly of text in CCOM” (at 133 [108]). The respondents also relied on the High Court’s decision in Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Ltd (1959) 102 CLR 232, where it was said at 249 that:

[m]any valid patents are for new uses of old things. But it is not an inventive idea for which a monopoly can be claimed to take a substance which is known and used for the making of various articles, and make out of it an article for which its known properties make it suitable, although it has not in fact been used to make that article before.

92 In his reasons for judgment, Heerey J referred to Burroughs [1974] RPC 147 and IBM [1980] FSR 564 as being “of particular importance for present purposes” (at 135-136 [118]). His Honour also considered analogous United States case law; notably, the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in State Street Bank & Trust Co v Signature Financial Group (1998) 149 F.3d 1368 (‘State Street’). That case – to which I will return in due course – involved a patent for a data processing system for the implementation of an investment structure involving the pooling of assets of mutual funds in an investment portfolio organised as a partnership. In the course of considering State Street, Heerey J noted previous United States authorities (to which Burchett J also adverted in IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218) which held that mathematical algorithms are not patentable subject matter to the extent that they are merely abstract ideas. However, his Honour ultimately endorsed the conclusion reached by the Court of Appeals in State Street, that (at 137):

the transformation of data representing discrete dollar amounts by a machine through a series of mathematical calculations into a final share price constituted a practical application of a mathematical algorithm formula and calculation because it produced “a useful, concrete and tangible result” in the form of a final share price momentarily fixed for recording and reporting purposes.

93 As will be observed later, the test considered appropriate in State Street was later disavowed in the decision of Re Bilski 545 F.3d 943 (Fed. Cir. 2008)). However, I do not consider that this affects his Honour’s decision.

94 In Catuity, his Honour concluded that the invention in question produced an artificially created state of affairs, in that “cards can be issued making available to consumers many different loyalty programs of different traders as well as different programs offered by the same trader”, instantaneously and at each relevant retail outlet (at 137 [127]). Accordingly the invention involved more than just an abstract idea, or method of calculation, and such a result was held to be beneficial in a field of economic endeavour – namely, retail trading (at 137 [127]). It is convenient to set out his Honour’s concluding words in full (at 137-138 [128]-[130]):

What is disclosed by the Patent is not a business method, in the sense of a particular method or scheme for carrying on a business - for example, a manufacturer appointing wholesalers to deal with particular categories of retailers rather than all retailers in particular geographical areas, or Henry Ford’s idea of stipulating that suppliers deliver goods in packing cases with timbers of particular dimensions which could then be used for floorboards in the Model T. Rather, the Patent is for a method and a device, involving components such as smart cards and POS terminals, in a business; and not just one business but an infinite range of retail businesses. CCOM and the English decisions referred to therein are in my opinion indistinguishable. The respondents’ argument for distinguishing CCOM - the supposed lack of “physically observable effect” - turns on an expression not found in CCOM itself. Nor does such a concept form part of the Full Court’s reasoning. In any event, to the extent that “physically observable effect” is required (and I do not accept that this is necessarily so) it is to be found in the writing of new information to the Behaviour file and the printing of the coupon.

The State Street decision is persuasive. It may be true, as the respondents argue, that United States patent law has a different historical source owing little or nothing to the Statute of Monopolies. The Constitution of the United States, Art 1, s 8, cl 8 confers power on Congress “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”. But the social needs the law has to serve in that country are the same as in ours. In both countries, in similar commercial and technological environments, the law has to strike a balance between, on the one hand, the encouragement of true innovation by the grant of monopoly and, on the other, freedom of competition.

As to the Microcell point, it cannot amount to the mere new use of a known article in a manner for which the known properties of that article make it suitable to have devised a particular method of processing data using a chip card, the properties of which (particularly its limited memory space) presented difficulties which were overcome only after much time and effort.

(Emphasis in original)

95 In 2006, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia delivered their decision in Grant. In that case, the Deputy Commissioner of Patents had revoked an innovation patent claiming a method of asset protection consisting of actions of financial and legal consequence that utilised a trust, a gift, a loan and security. Claim 1 of the patent was as follows (at 64[3]):

1. an asset protection method for protecting an asset owned by an owner, the

method comprising the steps of:

(a) establishing a trust having a trustee,

(b) the owner making a gift of a sum of money to the trust,

(c) the trustee making a loan of said sum of money from the trust to the owner, and

(d) the trustee securing the loan by taking a charge for said sum of money over the asset.

96 The primary judge upheld the Deputy Commissioner’s decision to revoke the patent. This decision was in turn upheld by the Full Court on appeal.

97 In doing so, the Full Court applied NRDC and the decisions following that case that have already been considered in these reasons for judgment (including the United Kingdom decisions of Burroughs [1974] RPC 147 and IBM [1980] FSR 564 considered by Burchett J in IBM (1991) 33 FCR 218 and the Full Court in CCOM). The Full Court summarised the United Kingdom decisions as follows (at 67 [18]):

In the United Kingdom, Graham and Whitford JJ considered claims for computer programs. In Burroughs Corp (Perkins) Application [1973] FSR 439 and International Business Machines Corporation’s Application [1980] FSR 564 their Lordships distinguished claims to a business scheme or intellectual information as the product of the conception of an idea, which are not patentable, from claims to methods which in practice (and whatever words are used in the claim) result in a new machine or process or an old machine giving a new and improved result which, applying NRDC, are patentable. The distinction drawn was between mere intellectual information and a method that affected the operation of an apparatus in a physical form. When the method is practiced in a way that is embodied in a physical form it is a manner of manufacture. There must be more than “a mere method or mere idea or mere desideratum” (Burroughs Corp Application at 160). Their Lordships declined to decide whether it was necessary that there be an artificial end product or effect. If this does exist it is patentable because the method affects the operation of the apparatus.

98 The Full Court also referred to various United States authorities on point to which I will later return, noting that (at 68-69 [24]):

While the development of US patent law is derived from the Constitution of the United States rather than the Statute of Monopolies, as Heerey J observed at [129] [in Catuity], the policy behind the two provisions is the same. In both jurisdictions, the courts have confirmed that a broad approach to subject matter should be taken in order to adapt to new technologies and inventions but that does not mean that there are no restrictions on what is properly patentable.

99 The Full Court noted the High Court’s emphasis in NRDC on the need for adaptability of patent law to cover technological developments, and stated (at 70 [29]):

In NRDC the High Court looked to the application of the claimed method. That is similar to the approach of courts in the United States. A product of a method is something in which a new and useful effect may be observed. For claimed computer programs, the courts looked to the application of the program to produce a practical and useful result, so that more than “intellectual information” was involved… The underlying principle, developed from the Statute of Monopolies, that business, commercial and financial schemes, which are “intellectual information” are not themselves properly the subject of letters patent, was maintained.

100 Ultimately the Full Court in Grant held that the method of the patent sought by Mr Grant did not produce any artificial state of affairs, “in the sense of a concrete, tangible, physical or observable effect” (at 70 [30]). On this basis, it was held to be different from the invention in Catuity, “which was a method involving components such as smart cards and point of sale terminals, and produced tangible results in the writing of new information to the Behaviour file and the printing of the coupon”. The Full Court noted that although it did not produce a physically observable end result (in the sense of a tangible product), the invention in Catuity involved “an application of an inventive method where part of the invention was the application and operation of the method in a physical device”, and accordingly, an artificial state of affairs in accordance with NRDC was produced.

101 By contrast, it was held that at best, Mr Grant’s method resulted only in “an abstract, intangible situation”. In concluding that for reasons “related to its operation and effect”, Mr Grant’s alleged invention did not involve a manner of manufacture, the Full Court stated (at 70-71 [32]):

A physical effect in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation is required. In NRDC, an artificial effect was physically created on the land. In Catuity and CCOM as in State Street and AT&T, there was a component that was physically affected or a change in state or information in a part of a machine. These can all be regarded as physical effects. By contrast, the alleged invention is a mere scheme, an abstract idea, mere intellectual information, which has never been held to be patentable, despite the existence of such schemes over many years of the development of the principles that apply to manner of manufacture. There is no physical consequence at all.

102 A further question in Grant was whether, notwithstanding this conclusion, the alleged invention lay in a “realm of human endeavour outside those in which patents may be granted” (at 71 [33]). The Full Court pointed to the fine arts as an example of such an area, and noted that (at 71 [34]):

The interpretation and application of the law would not be considered as having, in the words of NRDC, an industrial or commercial or trading character, although without doubt it is an area of economic importance (as are the fine arts). The practice of the law requires, amongst other things, ingenuity and imagination which may produce new kinds of transactions or litigation arguments which could well warrant the description of discoveries. But they are not inventions. Legal advices, schemes, arguments and the like are not a manner of manufacture.

103 But the Full Court did not accept that the realm of human endeavour in which patents may be granted can be defined positively as that of “science and technology”, observing (at 71 [38]):

We are not sure that this is correct. One thing that stands out from NRDC is the emphasis that their Honours put on the unpredictability of the advances of human ingenuity. What is or is not to be described as science or technology may present difficult questions now, let alone in a future which is as excitingly unpredictable now as it was in 1623 or 1959, if not more so. We think that to erect a requirement that an alleged invention be within the area of science and technology would be to risk the very kind of rigidity which the High Court warned against.

104 In any event, the Full Court determined that the scheme proposed by Mr Grant represented a new use of known products (being a trust, a gift, a loan and security) with known properties, where these properties make the products suitable for that new use – something which is not the proper subject of letters patent (at 71-72 [39]).

105 Before proceeding further, it is useful to make some general observations on these authorities and the principles to be applied in the manner of manufacture inquiry.

106 It must always be remembered that any attempt to set forth any prescriptive requirements for what is a “manner of manufacture” would be impermissible on the approach taken by the High Court in NRDC. To deny patentability to any class of invention (whether tangible or intangible) which would otherwise come within the principles developed by the courts over centuries would be to fail to follow the core teaching of NRDC.

107 The NRDC approach is one of flexibility, to allow for “excitingly unpredictable” and emerging inventions to be patentable. Whilst historically patents related to engineering, industry and applied science, the scope of patentable subject matter has expanded beyond these traditional areas.