FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Spirit Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Mundipharma Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 658

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The parties confer as to the appropriate orders for costs and, in default of agreement, the proceedings stand over for directions on the issue of costs to 12 July 2013.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1054 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | SPIRIT PHARMACEUTICALS PTY LIMITED (ACN 109 225 747) Applicant |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS First Respondent MUNDIPHARMA PTY LTD (ACN 081 322 509) Second Respondent PURDUE PHARMA LP Third Respondent MUNDIPHARMA LABORATORIES GMBH Fourth Respondent |

JUDGE: | RARES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 July 2013 |

WHERE MADE: | SYDNEY |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The parties (except the first respondent) confer as to the appropriate orders for costs and, in default of agreement, the proceedings stand over for directions on the issue of costs to 12 July 2013.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 721 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | SPIRIT PHARMACEUTICALS PTY LIMITED (ACN 109 225 747) Applicant

|

AND: | MUNDIPHARMA PTY LIMITED (ACN 081 322 509) First Respondent PURDUE PHARMA LP Second Respondent MUNDIPHARMA LABORATORIES GMBH Third Respondent |

JUDGE: | RARES J |

DATE: | 5 July 2013 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1054 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | SPIRIT PHARMACEUTICALS PTY LIMITED (ACN 109 225 747) Applicant

|

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS First Respondent MUNDIPHARMA PTY LTD (ACN 081 322 509) Second Respondent PURDUE PHARMA LP Third Respondent MUNDIPHARMA LABORATORIES GMBH Fourth Respondent |

JUDGE: | RARES J |

DATE: | 5 July 2013 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The central issue in these two proceedings is whether an extension of the term of Australian patent number 657027 (the patent) was validly granted under s 76 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act). The patent makes claims for certain pharmaceutical formulations that are marketed under the brand name “OxyContin”. The formulations achieve a controlled release of the opioid substance, oxycodone, into a patient’s blood plasma in particular concentrations over time. Oxycodone is a well known drug used to provide pain relief. Oxycodone was first patented in Germany in 1916.

2 The validity of the extension of the patent turns on whether the formulation of OxyContin is “a pharmaceutical substance per se” within the meaning of s 70(2)(a) of the Act. Spirit Pharmaceuticals Pty Limited is preparing to market a generic product of OxyContin. Spirit contends that oxycodone is the only “pharmaceutical substance per se” disclosed in the patent and that, accordingly, the extension of the patent was invalid. Mundipharma Pty Limited is currently the registered patentee of the patent. Euro-Celtique SA, a related company of Mundipharma, obtained the extension on 10 July 2000. The patent expired on 25 November 2012. Products containing various dosages of OxyContin were first registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on 23 July 1999. That registration had been sponsored by Mundipharma. Those products are manufactured in accordance with the formulation specified in the patent.

The nature of the two proceedings

3 Spirit commenced these two proceedings challenging the efficacy of the patent to prevent it from bringing its generic to market. Relevantly, in the first proceeding (the substantive proceeding) Spirit seeks an order under s 192 of the Act to rectify the Register of Patents by removing the extension of the term of the patent until 23 July 2014 (being the effective date agreed by the parties). Mundipharma and its related companies, Mundipharma Laboratories GmbH (Mundi Laboratories) and a limited liability partnership, Purdue Pharma LP, are the respondents to the substantive proceedings. Spirit had originally also challenged the validity of the patent in the substantive proceedings. However, that contention became inutile in a practical sense once the original term had expired. That was because the time that it would take for such a challenge to be heard and determined, once the parties had been able to adduce all the evidence on which they wished to rely, would have left Spirit little, if any, opportunity in which to market its generic product were it successful in proving that the patent was invalid.

4 Spirit advanced two principal contentions in support of the rectification of the Register sought in the substantive proceedings. It argued that the term of the patent should not have been extended in 2000 because first, the patent did not disclose a pharmaceutical substance per se, within the meaning of s 70(2)(a) of the Act and, secondly, the then registered holder of the patent, Euro-Celtique, had no beneficial interest in it at the time that it applied for an extension of the term in early 2000 and therefore no legal entitlement to do so.

5 Spirit brought the second proceeding seeking relief under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (the ADJR Act) and constitutional writ relief under s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (the ADJR proceeding). It challenged two decisions of the Commissioner of Patents, the first, being the Commissioner’s acceptance on 15 March 2000 of Euro-Celtique’s application for an extension of the term of the patent under s 74(1) of the Act (the 2000 decision) and, the second, being the refusal on 19 July 2010 of the Commissioner, by her Deputy Commissioner, of Spirit’s application for the making of an entry in the Register removing the extension of the term (the 2010 decision). The Commissioner submitted to any order that Court might make except as to costs. The active respondents in the ADJR proceedings are Mundipharma, Mundi Laboratories and Purdue. Spirit has sought an extension of time under s 11 of the ADJR Act in which to challenge the 2000 decision to accept the application for the extension of the term.

6 There is considerable overlap in the issues in the two proceedings. I will first consider the substantive question that arises in each proceeding, of whether the patent was capable of having its term extended. The answer to that question depends on whether the requirements of s 70(2)(a) were satisfied. I will then consider the other issues in dispute.

The Statutory Scheme

7 The Act as in force on 27 January 1999 provided for the grant of an extension of the term of a patent in Div 2 of Pt 3 of Ch 6. Relevantly, s 70 provided as follows:

“70 Applications for extension of patent

(1) The patentee of a standard patent may apply to the Commissioner for an extension of the term of the patent if the requirements set out in subsections (2), (3) and (4) are satisfied.

(2) Either or both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

(a) one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

(b) one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

(3) Both of the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances:

(a) goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods;

(b) the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

Note: Section 65 sets out the date of a patent.

(4) The term of the patent must not have been previously extended under this Division.

(5) For the purposes of this section, the first regulatory approval date, in relation to a pharmaceutical substance, is:

(a) if no pre-TGA marketing approval was given in relation to the substance—the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods of goods that contain, or consist of, the substance …” (bold italic original emphasis, bold emphasis added)

8 The Dictionary in Sch 1 of the Act contained the following two definitions that are material in understanding s 70(2)(a):

“In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

…

pharmaceutical substance means a substance (including a mixture or compound of substances) for therapeutic use whose application (or one of whose applications) involves:

(a) a chemical interaction, or physico-chemical interaction, with a human physiological system; or

(b) action on an infectious agent, or on a toxin or other poison, in a human body;

but does not include a substance that is solely for use in in vitro diagnosis or in vitro testing.

therapeutic use means use for the purpose of:

(a) preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons; or

(b) influencing, inhibiting or modifying a physiological process in persons; or

(c) testing the susceptibility of persons to a disease or ailment.”

9 An application for an extension had to be made during the term of the patent and, relevantly here, within six months after the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods that contain, or consist of, any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(2)(a) (here 23 July 1999) (s 71(2)(a)). The Commissioner had to accept the application if satisfied that the requirements of ss 70 and 71 had been met in relation to it (s 74(1)). The Commissioner had to, and in this case did, publish a notice of the application for an extension in the Official Journal (s 72). Any person had the right to oppose the extension in accordance with the Regulations on the ground that one or more of the requirements of ss 70 and 71 were not satisfied (s 75(1)). Any opponent had a right of appeal to this Court against a decision by the Commissioner under s 75(4). Importantly, a person could oppose the grant of an extension only on the ground that one or more of the requirements of ss 70 and 71 had not been satisfied (s 75(1)). Moreover, if there were, as here, no opposition, the Commissioner had to grant the extension (s 76(1)(a)).

10 Under s 76A, a patent holder, who had been granted an extension of the term of the patent under s 76, had to lodge a return before the end of the following financial year with the Secretary of the Department setting out among other information:

“(a) details of the amount and origin of any Commonwealth funds spent in the research and development of the drug which was the subject of the application; and

...

(c) the total amount spent on each type of research and development, including pre-clinical research and clinical trials, in respect of the drug which was the subject of the application.” (emphasis added)

11 The expression used in s 76A, “the drug”, was not defined, nor was it used elsewhere in Div 2 of Pt 3 of Ch 6 or in the Act. Section 78 provided that if an extension were granted, the patentee’s exclusive rights would not be infringed by another person exploiting a pharmaceutical substance per se in particular circumstances. Relevantly s 78(1) provided:

“78 Exclusive rights of patentee are limited if extension granted

(1) If the Commissioner grants an extension of the term of a standard patent, the exclusive rights of the patentee during the term of the extension are not infringed:

(a) by a person exploiting:

(i) a pharmaceutical substance per se that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification; or

(ii) a pharmaceutical substance when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

for a purpose other than therapeutic use; or

(b) by a person exploiting any form of the invention other than:

(i) a pharmaceutical substance per se that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification; or

(ii) a pharmaceutical substance when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.” (emphasis added)

12 A patent gave the patentee, subject to the Act, the exclusive rights to exploit the invention during the term of the patent (s 13(1)). Those rights were personal property that were capable of assignment (s 13(2)) and any assignment had to be in writing signed by or on behalf of the assignor and assignee (s 14(1)). Particulars of patents in force and other prescribed particulars relating to patents had to be registered in the Register (s 187). However, the Commissioner could not receive or register notice of a trust of any kind relating to a patent or licence (s 188). Significantly, s 189 provided:

“189 Power of patentee to deal with patent

(1) A patentee may, subject only to any rights appearing in the Register to be vested in another person, deal with the patent as the absolute owner of it and give good discharges for any consideration for any such dealing.

(2) This section does not protect a person who deals with a patentee otherwise than as a purchaser in good faith for value and without notice of any fraud on the part of the patentee.

(3) Equities in relation to a patent may be enforced against the patentee except to the prejudice of a purchaser in good faith for value.” (emphasis added)

13 The Register was prima facie evidence of any particulars registered in it (s 195(1)). A person committed a criminal offence if he or she knowingly or recklessly made, or caused to be made, a false entry in the Register (s 191(a) and (b)). Next, s 192(1) and (2) provided:

“192 Orders for rectification of Register

(1) A person aggrieved by:

(a) the omission of an entry from the Register; or

(b) an entry made in the Register without sufficient cause; or

(c) an entry wrongly existing in the Register; or

(d) an error or defect in an entry in the Register;

may apply to a prescribed court for an order to rectify the Register.

(2) On hearing an application, the court may:

(a) decide any question which it is necessary or expedient to decide in connection with the rectification of the Register; and

(b) make any order it thinks fit for the rectification of the Register.”

14 The Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth), as in force when Spirit applied for the removal of the entry of the extension of the patent in 2010, under reg 10.7, relevantly provided:

“(7) If:

(a) an extension of the term of a standard patent for a pharmaceutical substance has been granted under section 76 of the Act; and

(b) the Commissioner becomes aware that the first regulatory approval date in relation to the pharmaceutical substance is earlier than:

(i) the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods that was supplied, under subregulation 6.9 (2), with the application for the extension of the term; or

(ii) the date of the first approval that was supplied, under subregulation 6.10 (2), with the application for the extension of the term;

the Commissioner must amend the relevant entry in the Register to insert the correct extension of the term of the patent.”

15 Regulation 19.1 prescribed particulars for the purposes of s 187 as relevantly:

“19.1 Particulars to be registered

(1) For subsections 187(1) and (2) of the Act … the following particulars are prescribed, that is, particulars of:

(a) an entitlement as mortgagee, licensee or otherwise to an interest in a patent;

(b) a transfer of an entitlement to a patent or licence, or to a share in a patent or licence;

(c) an extension of the term of a patent;

…

(2) A request for registration of particulars referred to in paragraph (1) (a) or (b) must be in the approved form and have with it proof to the reasonable satisfaction of the Commissioner of the entitlement of the person making the request.”

The way OxyContin works

16 Before describing the patent, I will briefly explain how OxyContin works in comparison to immediate release products.

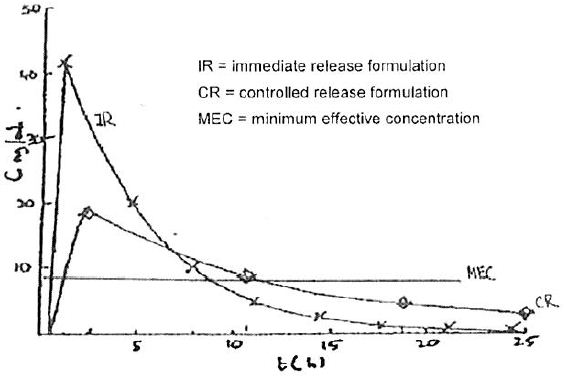

17 The first regulatory approval date for oxycodone within the meaning of s 70(3)(b) and (5) was in 1979. Oxycodone is an active pharmaceutical ingredient (or API) that relieves pain in a patient. It is a strong opioid analgesic synthesised from the alkaloid, thebaine, found in the opium poppy. It has an effect similar to that of morphine on a person to whom it is administered. It does this by attaching to nerve cell receptors in the spinal cord and the brain for a period of time. Prior to the invention of OxyContin, patients could be treated with immediate release formulations of oxycodone by another product called Endone, that had been included in the ARTG on 9 September 1991.

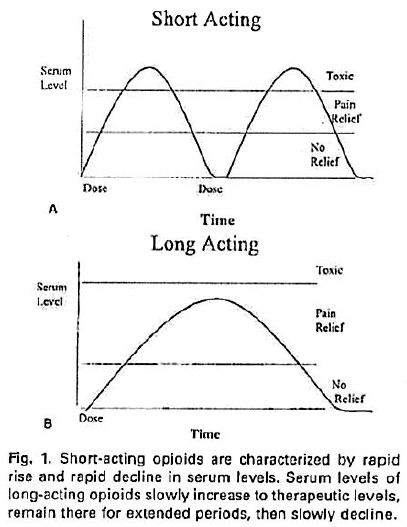

18 The controlled release of oxycodone enables doctors to manage medium to severe pain suffered by patients over time in a more effective manner than by using immediate release products. That is because, first, the fluctuation of the levels of oxycodone in the blood is reduced by the controlled release over the approximately 12 hour periods between each administration in comparison to those levels for numerous immediate release dosages over comparable total time periods. Secondly, the controlled release delivers a lower maximum level of the oxycodone into the blood plasma that gradually tapers to a higher minimum level than comparable levels achieved by multiple dosages of an immediate release product over the same period. This is because the immediate release product delivers the whole dose at once and its effect wears off more rapidly over the three or four hours until it must be administered again so that the peaks and troughs of the amount of oxycodone in the blood plasma are greater than those when OxyContin is used. This is illustrated in the following graphs. The “Short Acting” graph depicts the fluctuations of immediate release products and the “Long Acting” graph depicts the longer period of effective pain relief from the controlled release product (see Bill H McCarberg and Robert L Barkin: Long-Acting Opioids for Chronic Pain: Pharmacotherapeutic Opportunities to Enhance Compliance, Quality of Life and Analgesia (American Journal of Therapeutics (2001) 8 (3) 12 at 15)).

19 The space between the top line of the serum level scale and the line immediately below it is called the “therapeutic window”. The therapeutic window is the period of time when the blood plasma concentration of oxycodone is between the minimum and maximum concentrations for the substance to have a beneficial effect: i.e. when there is enough oxycodone in the blood plasma to provide the patient with pain relief. The lower of these levels is called the minimum effective concentration, or sometimes Cmin, and the upper level is called the maximum effective concentration, or Cmax. Dr Richard Oppenheim, one of the expert pharmaceutical witnesses, drew the following graph to compare blood concentrations achieved by immediate and controlled release doses of oxycodone recorded in table 21 forming part of example 19 of the patent:

20 Thirdly, the controlled release product is likely to be easier for both medical staff and self-treating patients to administer, being taken only twice a day and remaining, generally, at an effective level above or at Cmin until the time for the next dose. As the effect of an immediate release product wears off, the patient requires more of the product to deal with the returning sensation of pain. However, those treating him or her in hospital will not always be able to provide the next dose as soon as it is due or the patient begins experiencing pain. Patients and hospital staff can sometimes overlook the precise time required for one of six daily doses. And, of course, a controlled release product allows a patient the opportunity to sleep without four hourly interruptions to take the medicine.

21 Fluctuations in levels of oxycodone can lead patients to experience nausea and vomiting, which is more likely with immediate release dosages. However, it is usually necessary to titrate a patient using various dosages and strengths of oxycodone products to assess, first, whether he or she is adversely affected by it and, secondly, if not, the dosage strength that is sufficient to make his or her pain manageable.

The specification in the patent

22 The background of the invention sets out in the specification stated that surveys had found that a range of about eight different dosages of opioid analgesics was required to reduce pain in about 90% of patients. It recited that this wide range resulted in the titration process being particularly time and resource consuming, while the patient was without acceptable pain control for unacceptably long periods. The invention was identified as a formulation or formulations that resulted in improved delivery of oxycodone by using narrower dosage ranges and increased efficiency in pain management.

23 The background identified the objects of the invention as including relevantly the provision of:

(1) an opioid analgesic formulation for substantially improving the efficiency and quality of pain management;

(2) controlled release opioid formulations that had substantially less inter-individual variation of the dose of opioid analgesic required to control pain without unacceptable side effects.

The background asserted that those objects were attained by an invention that “is related to a solid dosage form” comprising between 10 mg and 40 mgs of oxycodone or a salt thereof (which I have called compendiously, as did the parties, “oxycodone”) in a matrix that achieved a particular dissolution rate of the oxycodone in vitro in identified circumstances and substantially independent of the level of pH. The background asserted that when used in vivo the invention resulted in the peak blood plasma level concentration of oxycodone between 2 and 4.5 hours after administration of the dosage form. Other assertions discussed the relation of the invention to particular controlled release formulations that corresponded to the various claims.

24 The detailed description section of the patent asserted that it had:

“now been surprisingly discovered that the presently claimed controlled release oxycodone formulations acceptably control pain over a substantially narrower, approximately four-fold (10 to 40 mg every 12 hours – around-the-clock dosing) in approximately 90% of patients.”

The detailed description contrasted that situation with the then existing need to administer opioid analgesics, in general, 8 times daily. It noted that another opioid analgesic, morphine, had been formulated into 12 hour controlled release formulations, known as MS Contin, which had qualitatively comparable pharmacokinetic characteristics. However, the description asserted that the dosage range for the oxycodone invention to achieve pain control for about 90% of patients was about half that of MS Contin’s. The description asserted that invention’s approximate halving of the dosage of oxycodone, as compared to other opioid analgesics, provided “for the most efficient and humane method of managing pain requiring repeated dosing”.

25 The detailed description also asserted that the peak plasma level that the invention achieved after administration of between 2 to 4.5 hours was capable of producing pain relief for at least 12 hours. The description compared that result with the usual 4 to 8 hour peak for formulations of dosages having at least a 12 hour therapeutic effect. Another advantage identified in the description was that the invention released oxycodone evenly throughout the human gastro-intestinal tract (GI tract), independently of the level of pH and so avoided “dose dumping upon oral administration”. The description then discussed the variety of manners in which the matrix for the controlled release could be formulated and prepared.

26 The specification set out 19 examples illustrating aspects of the invention, stating that these were not intended to limit the claims. Examples 1-12 set out varying methods and ingredients to prepare the matrix to provide controlled release tablets for identified dosages of oxycodone, but those 12 examples did not refer to blood plasma concentrations. Tables accompanying the examples identified in vitro dissolution rates of the oxycodone using various recognised dissolution study techniques.

The nature of the claims and their scope

27 Claims 3, 5 and 12 as made in the patent were:

“3. A controlled release oxycodone formulation for oral administration to human patients, comprising from 10 to 40 mg oxycodone or a salt thereof, said formulation providing a mean maximum plasma concentration of oxycodone from 6 to 60 ng/ml from a mean of 2 to 4.5 hours after administration, and a mean minimum plasma concentration from 3 to 30 ng/ml from a mean of 10 to 14 hours after repeated administration every 12 hours through steady-state conditions.

…

5. A solid controlled release oral dosage form, comprising

(a) oxycodone or a salt thereof in an amount from 10 to 160 mg;

(b) an effective amount of a controlled release matrix selected from the group consisting of hydrophilic polymers, hydrophobic polymers, digestible substituted or unsubstituted hydrocarbons having from 8 to 50 carbon atoms, polyalkylene glycols, and mixtures of any of the foregoing; and

(c) a suitable amount of a suitable pharmaceutical diluent, wherein said composition provides a mean maximum plasma concentration of oxycodone from 6 to 240 ng/ml from a mean of 10 to 14 hours after repeated administration every 12 hours through steady-state conditions.

…

12. A controlled release oxycodone formulation substantially as herein described with reference to any one of the Examples.” (emphasis added)

28 Each of claims 3-11 comprised a definition that included a dosage or range of dosages of oxycodone to be delivered orally contained in a matrix of excipients. Critically, that definition identified the invention as a formulation in which the matrix of excipients was intended to control the rate of release of oxycodone into the human GI tract. Once released into the GI tract, the oxycodone passes into the bloodstream and ultimately it operates on nerve receptors in the spinal column and brain so as to relieve pain. Each of claims 3-11 also referred to the formulation bringing about a maximum level (Cmax) blood plasma concentration of oxycodone in a mean time period (Tmax) after administration that would reduce to a minimum level (Cmin) concentration after another mean time period (Tmin). I need not deal with those parts of the patent specification that related to claims 1 and 2. Those claimed that the invention was a method for reducing daily dosages and the parties agreed that these were not relevant for consideration in these proceedings.

The expert evidence

29 The parties called two medical pain specialists, Professor Michael Cousins AM and Dr Charles Goucke, who gave their oral evidence concurrently. In addition, four experts in pharmacy and drug delivery, Dr Oppenheim, Dr Ian Pitman, Dr Angelo Morella and Professor Colin Pouton (the pharmacy experts) also gave concurrent oral evidence. The latter four also prepared a joint report that lucidly identified the relatively narrow area of disagreement within their expertise. That disagreement in large part overlapped with a substantive legal issue, namely the characterisation of whether the controlled release of oxycodone in the GI tract is a therapeutic use of itself (per se) or whether the only therapeutic use is the effect that oxycodone has when it reaches the nerve receptors in the spinal cord and brain.

30 The pharmacy experts said that the word “physico” in the expression “physico-chemical interaction” in par (a) of the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” was difficult to understand. However, they agreed that a chemical interaction, and, to the extent that “physico” added anything, a physico-chemical interaction was a process that had a reversible character. That is, such a process involved a transient or non-permanent interaction in contrast to one in which a permanent change occurred.

31 Thus, when ocycodene is released from OxyContin in the GI tract and passes into the blood plasma in which it then travels to the receptor cells in the spinal cord and brain, there are, at least, two interactions: one in the GI tract where the break up and release occurs, and the other at the receptor cells in the spinal cord and brain where the oxycodone interacts for a period of time before its effect wears off. After the effect wears off, the receptor cells are free to receive and interact with the next administered dose. The pharmacy experts contrasted such reversible interactions with processes in which covalent or strong chemical bonds were formed.

Spirit’s submissions as to whether OxyContin satisfied s 70(2)(a)

32 Spirit argued that none of claims 3 to 12 was for a pharmaceutical substance per se. It contended that this followed because each claim was defined by the following additional integers, namely that the formulation:

be for oral administration;

comprise certain dosages of oxycodone;

provides a Cmax of oxycodone at Tmax and a Cmin at Tmin after repeated administration every 12 hours through steady-state conditions when used by patients suffering pain.

33 Spirit argued that those integers narrowed each of claims 3 to 12 to a substance other than the simple claimed controlled release oxycodone formulation. It contended that even if the pharmaceutical substance per se were the mixture comprising the controlled release oxycodone formulation (rather than the unpatentable oxycodone), each claim was narrowed by the above additional integers because they created further limitations of that particular claim.

34 Both sides agreed that what the patent claimed was the invention of a product, not a method or process. However, Spirit argued that the notion of controlled release in the patent was defined by the result of a particular blood plasma concentration in claims 3-12. It pointed to varying integers in claims 3-11 that defined circumstances in which a result was achieved by various combinations. It contended that the skilled addressee would understand that the achievement of the result was not limited by any particular dosage or choice of excipients or their quantities in the mixture that, so Spirit asserted, Mundipharma was propounding as the pharmaceutical substance claimed in the patent for the purposes of s 70(2)(a).

Principles - Construction of the patent

35 The principles for the construction of a patent are relatively well settled. The whole of the patent must be considered for the purpose: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at 19 [31], see too 16-17 [24]-[25] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Limited v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610, 614, 616-617 per Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ. Jagot J distilled and set out many of the principles in Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No.4) [2013] FCA 162 at [230]-[235]. Here, the parties advanced differing constructions of the nature of the invention that the patent would have conveyed to a hypothetical addressee of the specification, being a non-inventive person skilled in the art before the priority date.

The case law on s 70(2)

36 The parties agreed that the precise issue of classification raised in these proceedings had not been considered in any earlier case concerning the application of s 70(2). In Boehringer Ingelheim International v Commissioner of Patents (2001) AIPC ¶91-670; [2000] FCA 1918 at [16], Heerey J held that s 70(2)(a) only permitted an extension application where “the claim is for a pharmaceutical substance as such, as opposed to a substance forming part of a method or process”. He had explained that broadly speaking there were three ways in which a claim could be made in relation to a pharmaceutical substance, namely, first, a new and inventive product alone (being the meaning his Honour found for “pharmaceutical substance per se” in s 70(2)(a)), secondly, an old or known product prepared by a new and innovative process and, thirdly, an old or known product used in a new and inventive mode of treatment (at [14]). These three possible categories may not be exhaustive, as Allsop J commented in his concurring reasons in Prejay Holdings Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (2003) 57 IPR 424 at 430 [36], but nothing turns on this question in these proceedings.

37 The Full Court affirmed Heerey J’s decision and reasoning in Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH v Commissioner of Patents (2001) 112 FCR 595 at 604 [37]. There Wilcox, Whitlam and Gyles JJ rejected a construction of s 70(2)(a) that it was sufficient for the complete specification to disclose one or more pharmaceutical substances whether as the sole element in an invention or in combination with other elements. They held that, first, such a construction would pay no regard to the expression “per se”, secondly, the second reading speech of the Minister introducing the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Bill 1997 (Cth) that inserted Div 3 of Pt 2 of the Ch 6 into the Act and the Explanatory Memorandum for that Bill referred respectively to the “development of a new drug” and to claims to “pharmaceutical substances per se, [being] … usually restricted to new and inventive substances” and, thirdly, s 78(1)(b)(ii) showed that an infringement during the extended term would only occur if a third party exploited the pharmaceutical substance per se (112 FCR at 604-605 [38]-[41]).

38 The issue in Boehringer (2001) AIPC ¶91-670 and 112 FCR 595 was whether the patent claiming a container comprising a nasal spray that contained a pharmaceutical substance, could be extended. Both Heerey J and the Full Court held that since the container was not a pharmaceutical substance, the condition in s 70(2)(a) was not satisfied. The patent there did not claim the container, but rather, as Heerey J held, it made claims for modes of treatment involving the substance (delivered into the nose using the container), but not for the substance itself (at [3]-[4], [19]). Heerey J also referred to the then current Patent Office Manual of Practice and Procedure (at [17]-[19]). He said that the Manual was both an internal guide as to the administration of the Act and was also made available to the patent attorney and legal professions. His Honour set out a considerable portion of the Manual at [18] in his reasons.

39 Here, each side sought to rely on one or more of the passages that Heerey J had set out from the Manual. However, while that extract was a helpful discussion, none of the passages relied on provides a decisive test that is appropriate to resolve the present issue.

40 In Prejay 57 IPR at 429 [23]-[25] Wilcox and Cooper JJ, with whom Allsop J agreed, said that in Boehringer 112 FCR at 605 [42] the Full Court had held that:

“… for a substance to fall within s 70(2)(a) it must itself be the subject of a claim in the relevant patent. It is not enough that the substance appears in a claim in combination with other integers or as part of the description of a method (or process) that is the subject of a claim. The policy adopted in s 70 was to confine extensions to patents that claim invention of the substance itself.

This conclusion is not negatived by the terms of s 70(2)(b) of the Act. ..., that paragraph does not require disclosure of a process. Rather, it requires the disclosure of “one or more pharmaceutical substances” that are produced by a particular process.” (emphasis added)

41 Prejay 57 IPR at 424 concerned only method claims that involved use of a particular pharmaceutical substance. The patentee had argued, unsuccessfully, that “pharmaceutical substance” as used in s 70(2)(a) with the qualifier “per se” was wide enough to incorporate both the substance and a method integer. The Full Court held that there, as in Boehringer 112 FCR 595, the substance in itself was not a thing claimed in the patent sense (57 IPR at 429 [23]-[24], 430-431 [39]-[42]). Rather, the claim was for the substance with the method integer.

42 Nonetheless, a pharmaceutical substance per se need not equate with the subject matter of the claim in patent terms, as Bennett J, with whom Middleton J agreed, held in H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151 at 202-203 [242]. Her Honour explained:

“For example, a chemical compound claimed in a patent may not have the necessary therapeutic use or enable the required physico-chemical interaction unless formulated. It is sufficient if the pharmaceutical substance is in substance disclosed in the specification and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims. At that point in the scheme of s 70, the satisfaction of s 70(2), the necessary definition of the pharmaceutical substance by reference to the patent ceases.” (emphasis added)

43 Bennett J said that the definition of pharmaceutical substance focused “on the ingredient for therapeutic use that involves the relevant type of interaction” (177 FCR at 202 [238]). In that case, her Honour concluded that the subject matter of the relevant claim in the patent was a particular molecule that had been separated, purified or isolated. She held that that molecule per se fulfilled the requirement of s 70(2)(a) because (177 FCR at 203 [244]):

“It is the molecule that “works” as a pharmaceutical substance alone, or together with other substances, in goods listed on the ARTG. These other substances may be components of a formulation or may otherwise be described as impurities, …”

44 In Pharmacia Italia SpA v Mayne Pharma Pty Ltd (2006) 69 IPR 1 at 20-21 [96]-[101], 22 [106]-[107] Weinberg J held that for the purposes of s 70(2)(a), a claim must be read sensibly, and as a whole, for the purpose of determining whether it is a claim to a pharmaceutical substance per se. He construed the claim in that case as being one to such a substance, notwithstanding that elements of the claim, as expressed, described aspects of a process. But, Weinberg J held that those aspects (69 IPR at 21 [100]-[101]):

“… simply mark out the basis upon which the new and inventive substance can be distinguished from other prior art, and enable the scope of the protection to be more accurately understood.

Patent rights, and in particular the right to an extension, are very much dependent upon the language of the claim which defines the invention. When construing a claim, in order to determine whether the requirements set out in s 70(2)(a) are satisfied, it is appropriate to have regard to the reason why any reference to process has been included in the claim as formulated. There is a difference between seeking to protect a process (which can be the subject of a patent, but cannot be the subject of an extension), and merely referring incidentally to some elements of process, that are not themselves novel, in order to better describe the new and inventive substance. Section 70(2)(a) provides that a new and inventive substance that is a “pharmaceutical substance per se” can be the subject of an extension. (emphasis added)

45 Spirit argued that Weinberg J was wrong because his Honour treated the claim as simply for a product without analysing further and enquiring whether it was for a pharmaceutical substance per se. I disagree. The passage just quoted shows that Weinberg J addressed the correct question and, arrived at the correct construction of s 70(2)(a).

Construction of s 70(2)

46 It was common ground that OxyContin was used for the purpose of alleviating pain in patients. However, the parties and the experts differed as to whether or not that purpose was achieved solely by the only active pharmaceutical ingredient in the formation, oxycodone, or by the mixture of it with excipients that resulted in its controlled release.

47 The task of statutory construction must begin with a consideration of the statutory text, here the Act: Commissioner of Taxation v Unit Trend Services Pty Ltd (2013) 297 ALR 190 at 200 [47] per French CJ, Crennan, Kiefel, Gageler and Keane JJ. Their Honours also said that context and purpose were important to the proper construction of the relevant provision. Because I consider that the text of the relevant provisions of the Act has a clear meaning, for the reasons below, it is not necessary to consider any extrinsic materials.

48 The condition specified for an extension of a patent in s 70(2)(a) required that one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance (1) be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent; and (2) fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification. The expression “pharmaceutical substance” was defined in the Dictionary in Sch 1 of the Act, but there was no definition of how the words “per se” affected its meaning as used in ss 70(2)(a) and 78.

49 I am of opinion that the expression “pharmaceutical substance” used in s 70(2)(a), read with its definition and that of “therapeutic use”, relevantly in the context of considering the nature of OxyContin, meant a substance, including a mixture, used for the purpose of alleviating an ailment (pain), one of whose applications involved a chemical interaction with a human physiological system. The definition of “therapeutic use” required that the substance (or mixture) be used “for the purpose” of alleviating pain in persons. The substance or mixture had to have at least one application that involved a chemical interaction with a human physiological system. The statutory language thus required, if s 70(2)(a) were to be satisfied, the use of the substance for the purpose of alleviating pain by being applied in a way that involved a chemical interaction with a human physiological system.

50 The requirement in s 70(2)(a), that the patent must relate to a pharmaceutical substance per se, was connected to the altered nature of the exclusive rights that the patentee acquired pursuant to s 78 under an extension of the patent. That alteration came about because s 78(1) provided that the patentee’s exclusive rights under an extension were not infringed by a person exploiting either (1) a pharmaceutical substance per se referred to in s 70(2)(a) for a purpose other than therapeutic use, or (2) any form of the invention other than such a pharmaceutical substance per se.

51 In other words, s 78(1) operated to limit effectively only for therapeutic use, the exclusive rights that an extension of a patent created in a patentee to the exploitation of the, or a, pharmaceutical substance per se comprised in the invention. The exceptions to the patentee’s exclusive rights created by s 78(1) operated to confine the extended patentee’s monopoly to the exploitation of only the, or a, pharmaceutical substance per se being, or comprised in, the invention for the purpose of therapeutic use. Thus, the condition imposed by s 70(2)(a) served the purpose of identifying the subject matter of the more limited exclusive rights which the patentee could assert in the period of the extension, as compared to the relatively greater rights that the patentee had during the original term of the patent.

52 Unlike the condition in s 70(2)(a), the condition in s 70(2)(b) permitted the making of an extension application for one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involved the use of recombinant DNA technology. Thus, s 70(2)(b) permitted one particular form of process claim involving a particular category of pharmaceutical substances, rather than being limited to a pharmaceutical substance per se as in the case of s 70(2)(a).

53 Spirit argued that s 76A assisted its proffered construction that the expression “pharmaceutical substance per se” meant only the active pharmaceutical ingredient. It contended that this followed from the use in s 76A of the expression “the drug which was the subject of the [extension] application”. I do not consider that this argument has any substance. The word “drug” was not defined in the Act. Its ordinary and natural meaning, in the context of s 76A and Div 2 of Pt 3 of Ch 6 as a whole was the pharmaceutical substance per se the subject of the extension application. The dictionary meanings of “drug” include:

a natural or synthetic substance used in the prevention or treatment of disease; a medicine; a substance that has a physiological effect on a living organism; (Oxford English Dictionary online; sense 1).

a chemical substance given with the intention of preventing or curing disease or otherwise enhancing the physical or mental welfare of humans or animals (Macquarie Dictionary online; sense 1).

54 In ordinary English, Endone and OxyContin are both “drugs”, even though oxycodone is the common active pharmaceutical ingredient used in each of their formulations. The word “drug” as used in s 76A did not narrow or elucidate the meaning of “pharmaceutical substance per se” as used elsewhere in Div 2 of Pt 3 of Ch 6 of the Act. It is likely that the two expressions referred to the same subject matter. This is reinforced by the qualification of “drug” used in s 76A that it “was the subject of the [extension] application”. This demonstrated only a circularity in the statutory language, namely that the “drug” in s 76A was whatever satisfied the condition in s 70(2)(a), namely “one or more pharmaceutical substances per se” the subject of the extension application.

The nature of claims 3 to 12

55 Broadly speaking, each of claims 3 to 12 covers a controlled release oxycodone formulation which has particular characteristics or integers described in the relevant claim. None of the claims is in terms a claim that relates to oxycodone of itself (or per se) as the subject matter of the invention. The essence of the invention is the formulation of a mixture comprising oxycodone and excipients (inactive pharmaceutical ingredients) that, on oral administration to a human patient, will achieve a controlled release of therapeutically useful (as opposed to harmful or ineffective) amounts of oxycodone into the human GI tract and thence into the blood stream for delivery to nerve cell receptors in the spinal cord and brain for the alleviation of pain over a 10 to 14 hour period, after repeated administration every 12 hours.

Claims 3 and 4

56 These two claims related to controlled release formulations of specified ranges of dosages of oxycodone (10 mg to 40 mg in claim 3 and 10 mg to 160 mg in claim 4) that met stated pharmacokinetic parameters after repeated administration every 12 hours through steady state conditions. Those parameters were mean maxima (Cmax) and minima (Cmin) plasma concentrations after 2 to 4.5 hours (Tmax) and 10 to 14 hours (Tmin) respectively of 6 to 60 ng/ml and 3 to 30 ng/ml (claim 3) and 6 to 240 ng/ml and 3 to 120 ng/ml (claim 4).

Claims 5 to 8

57 As Professor Pouton explained, claims 5 to 8 described various embodiments of controlled release formulations containing between 10 and 160 mg of oxycodone and broad classes of excipients that can be used to achieve the range of defined plasma concentrations that had been defined in claim 4. Thus, each of these four claims described an embodiment of the invention that used different excipients to achieve controlled release of oxycodone within the desired pharmacokinetic parameters. (The particular wording of claim 5 is set out at [27] above.)

Claims 9 to 11

58 These three claims described other embodiments of controlled release formulations also containing between 10 and 160 mg of oxycodone that provided a range of in vitro dissolution rates specified in the respective claims in which various percentages of the oxycodone dosage were released at identified times.

Claim 12

59 I have set out the wording of the omnibus claim 12 in [27] above. That wording raised an issue as to the limiting effect of the expression “substantially as described herein with reference to any one of the Examples” as a qualification of the controlled release oxycodone formulation. Examples 1 to 12 described various methods of manufacturing the formulation, ingredients and dissolution rates with dosages of 10, 20 and 30 mg of oxycodone. However, none of those examples contained any pharmacokinetic parameters. Examples 13 to 16 described the same pharmacokinetic parameter results achieved in clinical studies using formulations prepared in accordance with examples 2 and 3. Examples 17 to 19 described some pharmacokinetic parameter results achieved in other clinical studies using some unspecified controlled release oxycodone formulations “of the present invention” with dosages of 10, 20 and 30 mg of oxycodone.

60 I am of opinion that the expression in claim 12 “substantially as described” referred to the pharmacokinetic parameters of blood plasma concentrations for the dosage ranges of between 10 and 160 mg of oxycodone disclosed in claims 3 to 11 of the patent. Thus, claim 12 specified that an embodiment of the controlled release oxycodone formulation must at least, first, satisfy those pharmacokinetic parameters and, secondly, meet one or more of the criteria or descriptions in any of the 19 examples. In this way claim 12 confined the monopoly it described by first, requiring that the formulation achieve results within the pharmacokinetic parameters and, secondly, fall within the criteria of any one of the examples.

Consideration

61 When any of the embodiments of the formulation claimed is taken orally and ingested by a human patient it undergoes a chemical interaction within the GI tract. That interaction causes the formulation to break down in a way that gradually causes the oxycodone in the mixture to leach into the GI tract (the GI tract interaction). The oxycodone then passes out of the GI tract and into the blood plasma to be carried to the nerve cell receptors in the spinal cord and brain to relieve or alleviate the patient’s pain (the nerve interaction). The mixture of substances, being the controlled release oxycodone formulation claimed, is used for the therapeutic purpose of alleviating pain safely (having regard to the size of the dosage) over a relatively long period. The results achieved by the formulation are different to those achieved by repeated doses, over the same time period, of oxycodone in a product like Endone, that is immediately released. Indeed, a large dose of oxycodone contained in OxyContin were immediately released might be harmful to the patient, whereas its controlled release should not cause harm, but will alleviate pain over a protracted period.

62 It follows that the formulation, OxyContin, is a mixture of substances that has a “therapeutic use” within the statutory definition of that expression. That use is achieved by at least two chemical interactions in the human physiological system. The first is the GI tract interaction where the mixture gradually leaches its constituents into the GI tract. The chemicals in the GI tract gradually break down the excipients that effectively contain the oxycodone so that both the excipients and oxycodone are released from the mixture through that chemical interaction. The second is the nerve interaction that results in the alleviation of pain when the oxycodone interacts with the nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain.

63 The precise wording of claim 3 is set out at [27] above. Claims 3 and 4 cannot be characterised as claims for oxycodone per se; indeed, none of claims 3 to 12 can be so characterised. An immediate release of a dosage of oxycodone of 160 mg would have a very different effect on the patient to the effect the same dosage would have if it were released in the way claimed in the patent. That is why the claims identify a formulation that includes, but is not solely, oxycodone. The formulation achieves controlled release of the oxycodone within the various parameters.

64 The definition of “pharmaceutical substance” requires the mixture to be, relevantly, for therapeutic use (i.e. for the purpose of alleviating pain) and “whose application (or one of whose applications) involves” a chemical interaction with a human physiological system. The word “involves” in the definition relates to the application of the substance or mixture. Thus, OxyContin has two relevant applications that “involve” a chemical interaction, the GI tract interaction and the nerve interaction. The scope of claim 3 is a claim for the mixture that includes, but is not limited, to the active pharmaceutical ingredient, oxycodone. The mixture (formulation) is applied for the purpose of alleviating pain because, when ingested, it will release oxycodone gradually. Similarly, claim 4 is made for another embodiment of the pharmaceutical substance per se being a controlled release oxycodone formulation.

65 The formulation of OxyContin, an embodiment of which is in claim 3, has the status of being a pharmaceutical substance per se because it has the purpose of alleviating pain (therapeutic use) and one of the mixture’s applications involves an intended and necessary chemical interaction in the GI tract that is the subject matter of the patent. The other application also involves a later intended and necessary chemical interaction with the nerve cells.

66 In my opinion, the pharmaceutical substance per se that falls within the scope of the claims in the specification in the patent is a controlled release oxycodone formulation. It is disclosed in various embodiments in the complete specification and in the claims. The invention consists of the formulation comprising oxycodone mixed with excipients or ingredients in varying quantities within a range of pharmacokinetic parameters so that the oxycodone is gradually leached into the patient’s GI tract after it has been ingested: cf Prejay 57 IPR at 429 [23]-[24].

67 In other words, the formulation claimed in claim 3 is a mixture of substances that comprised of oxycodone and the excipients that bring about the controlled release of the active pharmaceutical ingredient. The four pharmaceutical expert witnesses agreed that OxyContin was a mixture of substances. That was because, in each formulation contemplated by claims 3 to 12, oxycodone and the excipients were interspersed but were not joined together by covalent (i.e. strong) bonds.

68 Dr Pitman, one of the pharmaceutical experts, when discussing the large lists of possible combinations of excipients in the background of the invention on pages 9 to 12 in the patent, said:

“It was also well known to me that the concentration and mix of polymers would require only routine steps to determine the optimum combination or concentration to achieve the desired release rate. In my experience this was part of the basic, day to day work of pharmaceutists before November 1991.” (emphasis added)

He gave similar evidence in relation to other excipients and the process of preparing the tablets mentioned in the claims and examples. That evidence was not contentious. I infer from it that before and at November 1991, a pharmaceutical addressee of the patent skilled in the art, when informed of the required dosage of oxycodone and the pharmacokinetic parameters disclosed in claims 3 to 11 or those used in any of the examples incorporated in claim 12, would be able to make a mixture of the oxycodone and excipients for oral administration that would achieve the relevant controlled release rate referred to in the claims. That mixture would be an embodiment of the invention of a controlled release oxycodone formulation.

69 The pharmaceutical substance per se disclosed in the specification and in substance falling within the scope of the relevant claim or claims of that specification had two essential integers: it was a mixture of first, a dosage of oxycodone within the range of 10 to 160 mg and, secondly, excipients that would bring about a controlled release of that dosage within the requisite pharmacokinetic parameters. The particular varieties of excipients in the second integer were aspects or embodiments of what was necessary to cause the relevant dosage of oxycodone in the first integer to be released within the range of the pharmacokinetic parameters.

70 Claims 3 and 4 were general claims. They did not specify or include any necessary excipients as features of the second integer. Those claims defined, in a general way, a pharmaceutical substance per se by reference to a mixture of a dosage of oxycodone within a specific range formulated in such a way that the active pharmaceutical ingredient would be released within the range of the pharmacokinetic parameters when ingested by a patient in the circumstances described in the claim. Addressees skilled in the art would be able to select the necessary excipients to make the formulation based on that information.

71 Claims 5 to 11 included narrower particular embodiments of the excipients that were to be used in the particular mixture there claimed. As Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ observed in Welch Perrin 106 CLR at 618, the common practice of those who draft claims is to begin with more general ones and then descend to ones of more and more particularity “in the hope that, if the earlier be said to be too wide, the latter will be valid and effective to catch some integers”. However, as their Honours said, there is no reason for construing the generality in one claim as if it were limited by the particularity in another. Accordingly, I am satisfied a pharmaceutical substance per se, being a controlled release oxycodone formulation, was in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance this fell within the scope respectively of claims 3 and 4 so as to come within the condition prescribed in s 70(2)(a).

72 Spirit argued that the second integer that I have identified for claims 3 and 4, was a limitation to the result as opposed to the particular ingredients and processes. That argument however does not deny that the invention was a mixture embodied in a formulation that worked within and achieved particular pharmacokinetic parameters. The pharmaceutical substance produced must simply meet those parameters as a specification of its essential formation. The skilled addressee could make the specified mixture routinely, using excipients that were well known, as Dr Pitman explained.

73 The specification or (as Spirit characterised it) the nominated result in the pharmacokinetic parameters, simply had the function of defining the necessary characteristics of whatever excipients were selected as part of the mixture to embody the formulation that would achieve the controlled release of the particular dosage of oxycodone. However, the mixtures formulated with the relevant dosages and excipients to achieve the pharmacokinetic parameters for the controlled release, as specified in claims 3 and 4, were all embodiments of the pharmaceutical substance per se, OxyContin, that met the criteria in s 70(2)(a). The same applies for formulations made in accordance with claims 5 to 12.

74 A therapeutic use of OxyContin is the controlled release delivery of its constituent active pharmaceutical ingredient over time. There is no reason to limit the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” to one therapeutic use. OxyContin works to alleviate pain over a relatively long therapeutic window as compared to an immediate release product such as Endone. The mixture, being the controlled release oxycodone formulation, achieves the purpose of alleviating pain by releasing oxycodone gradually through two chemical interactions: the GI tract and nerve cell interactions. The general class of appropriate excipients to include in a mixture to produce a formulation in claims 3 or 4 was in substance disclosed in the complete specification and fell within those claims: cf Pfizer Inc v Commissioner of Patents (2005) 141 FCR 413 at 420-421 [50], 424 [77]-[78] per Bennett J.

75 Accordingly, I am of opinion that that formulation is a pharmaceutical substance per se. The new and inventive product disclosed is a mixture of dosages of oxycodone and excipients that meets the pharmacokinetic parameters in each of claims 3 to 12 as discussed above.

Did Euro-Celtique have any right to apply for an extension under s 70(1)?

76 Euro-Celtique made the application for extension of the patent on 19 January 2000. However, on 7 December 1999, Euro-Celtique and Mundipharma Medical GmbH (Mundi Medical) executed an agreement by which Euro-Celtique assigned all of its right, title and interest in the patent to Mundi Medical for $1 (the 1999 assignment). As I will explain below, both Euro-Celtique and Mundi Medical appear to have been then, and remained at the time of the trial, companies beneficially owned and controlled by trusts held for the benefit of the Sackler family. However, nothing was done to register Mundi Medical as patentee after the 1999 assignment. Euro-Celtique remained registered as patentee when it applied for the extension of the patent about seven weeks after the 1999 assignment occurred.

77 On 28 June 2005, Euro-Celtique entered into an agreement with Purdue under which Euro-Celtique purported to assign the patent and another patent to Purdue for a consideration of $100 (the Purdue assignment). Next, on 29 June 2005, Purdue entered into an agreement to assign both the patents to Mundi Laboratories for a consideration of $100 (the 2005 Mundi assignment). On 30 June 2005, Mundi Laboratories entered into an agreement to assign the two patents to Mundipharma for the same consideration as the two previous transactions (the 2005 Mundipharma assignment). The parties to those assignments (or at least Euro-Celtique) appeared to have forgotten about the 1999 assignment under which, another company in the group, Mundi Medical, beneficially owned the patent. The three assignees under the three 2005 assignments were sequentially registered as patentee in the Register on 23 August 2005. Thus, on 23 August 2005, as the last of the sequence. Mundipharma was and remains registered as patentee.

78 After these proceedings commenced, Mundipharma, Mundi Laboratories and Purdue (the Mundi parties) gave discovery. As a consequence, Spirit’s solicitors wrote to their counterparts on 7 December 2010 drawing attention to the anomaly and apparent gap in the chain of title caused by the 1999 assignment and the inconsistent dealings in June 2005. That led to Euro-Celtique, Mundi Medical, Mundi Laboratories, Purdue and Mundipharma entering into a deed on 10 February 2011 (the 2011 deed). Under the 2011 deed, the parties acknowledged that the 2005 assignments may have been ineffective under Australian law as legal assignments of the patent because of the 1999 assignment. The deed recorded that each of Euro-Celtique, Mundi Laboratories, Mundi Medical and Purdue assigned whatever rights it had in the patent to Mundipharma.

79 Anthony Roncalli, a New York attorney, explained in affidavit evidence aspects of the relationship between Euro-Celtique, Mundi Laboratories, Mundi Medical, Purdue and Mundipharma (the Sackler entities). Mr Roncalli had acted for the Sackler families and companies they controlled since 1990, including Euro-Celtique and Mundi Medical. I infer from his evidence that those latter two companies were part of a group of companies at all times between 1999 and the time of the trial. He said that Euro-Celtique acted as a patent service agent making applications and holding patents as a service to other companies in the group. He also said that Mundi Medical acted as a distributor within the group and was assigned rights to certain territories in which the group operated. Mr Roncalli said that on a day to day basis each of himself and a United Kingdom lawyer, Christopher Mitchell, with whom he had worked closely over the years, among others, gave instructions to executives or employers of companies in the group about the execution of legal documents, including dealings in relation to patents. However, the nature of those “instructions” and the generality of Mr Roncalli’s evidence on his role does not assist in the making of any findings as to what occurred within the group immediately after the 1999 assignment in relation to the extension application.

80 Importantly, Mr Roncalli said that he instructed all the Sackler entities to execute and deliver the 2011 deed on the basis of his knowledge that its recitals were accurate.

81 Spirit tendered part of an affidavit by Philip Strassburger sworn on 28 February 2011. He made that affidavit, and it was read on behalf of Mundipharma earlier in the substantive proceedings, but not at the trial. Spirit relied on the tendered passages as an admission by Purdue. Mr Strassburger was the vice president, intellectual property counsel, of Purdue. In June 1999, he began working for Purdue as chief counsel, intellectual property. He said that he was responsible for and familiar with the files relating to the prosecution of patent applications made in Euro-Celtique’s name, including the patent in issue here. Spirit submitted that, Mr Strassburger had knowledge of Euro-Celtique’s dealings in respect of the patent but was not called at the trial by the Mundi parties who gave no explanation for his absence. It argued that his evidence would not have assisted the Mundi parties’ case.

82 Spirit did not suggest that any events subsequent to Euro-Celtique’s application for and grant of the extension were not valid and effective. Spirit only led evidence from one of its external solicitors, Georgia Marshall. She said that she had made enquiries on behalf of Spirit commencing on 6 February 2009 concerning registration of any product containing oxycodone of the Department of Health and Ageing and the TGA. At that time, the Register recorded Mundipharma as the patentee. There is no evidence that this record of the patent’s legal owner caused any person, including Spirit, to act in any way to its detriment. Moreover, Mundipharma had sponsored the inclusion of OxyContin on the ARTG in 1999, thus demonstrating a bona fide connection to the patentee. In light of the evidence, I am satisfied that Mundipharma was intended to be their beneficial owner of the patent at that time.

Spirit’s submissions as to Euro-Celtique’s right to apply for the extension

83 Spirit argued that because Euro-Celtique had assigned the patent to Mundi Medical on 7 December 1999, it could not use its status as registered patentee to apply for the extension on 19 January 2000. That result followed, it argued, for two principal reasons. First, a person who had assigned its entire beneficial interest was no longer a “patentee” within the meaning of the Act based on Sanofi v Parke Davis Pty Ltd (1983) 152 CLR 1. Secondly, Spirit contended, s 187(1) and reg 19.1(a) and (b) operated to require that the 1999 assignment and Mundi Medical’s status as both beneficial and legal owner of the patent be registered. As a corollary of this argument, Spirit contended that the scheme of the Act required the new assignee to become registered so as to preserve the purity of the Register by analogy with the position under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) as explained in Health World Ltd v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 240 CLR 590.

84 Spirit argued that Mr Roncalli’s evidence was inadmissible to the extent that it dealt with matters falling within s 7 of the Foreign Corporations (Application of Laws) Act 1989 (Cth). That section required that any question relating to, among other matters, the membership of a foreign corporation, the existence, nature or extent of any other interest in such a corporation, its internal management and proceedings and the validity of its dealings otherwise than with outsiders, must be determined by reference to the law applied by the people in the place in which the foreign corporation was incorporated (s 7(3)(b), (f), (g), (h)). The Mundi parties led no evidence of the laws applicable to corporations in Luxembourg or Switzerland, where Euro-Celtique and Mundi Medical respectively were incorporated.

Consideration

85 I reject Spirit’s arguments. First, Mason ACJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ in Sanofi 152 CLR at 7 (with Brennan J agreeing on this aspect at 18) held that the definition of “patentee” in the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) was not necessarily limited to identifying only the person who was patentee of a patent that was in force. In that case, after its patent had expired, the patentee applied for an extension on the basis that it considered it had been inadequately remunerated. Their Honours held that, reading the 1952 Act as a whole, and in particular Pt IX, which dealt with extensions, the word “patentee” had an extended meaning beyond its defined meaning so that it included the proprietor of an expired patent. They did not discuss the position of an unregistered assignment.

86 Spirit fell back on a remark by the trial judge in Re Sanofi’s Patent Extension Petition [1983] 1 VR 25 at 30. There, Fullagar J (whose decision was upheld in Sanofi 152 CLR 1) said in an obiter dictum that:

“An assignment of ‘the patent’, or of all patent rights, or of all property, carries the right to apply for prolongation, whether the assignment takes place before or after expiry of the patent in question.”

87 In that case, the previous patentee had ceased to exist in 1975 and all its property, including the patent, vested in Sanofi as a result of the equivalent of a scheme of arrangement or merger under French law. The patent expired in 1979 ([1983] 1 VR at 26). As I have explained, Sanofi [1983] 1 VR 25 and 152 CLR 1 dealt with a different factual and legal situation to that here. The Courts were dealing with the right of a person who had been registered as patentee of an expired patent to apply for its extension after its expiry. They were not dealing with a situation where, as here, a separation had occurred between legal and equitable interests in the patent at the time an application for an extension was made by the registered patentee. Nor did their Honours consider the issues raised by any analogue in the 1952 Act of the express recognition in s 189 of the 1990 Act of the validity of bona fide separate dealings in and rights in respect of legal and equitable estates in a patent. An argument similar to that advanced by Spirit in relation to a beneficial owner allowing a bare trustee to hold the trustee’s name shares in a company, where no third party’s rights were affected was debunked, with his usual elegance, by Lord Cairns LC in Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company v The Queen (1875) LR 7 HL 496 at 507-510: see too Meagher, Gummow & Lehane’s: Equity: Doctrines and Remedies (4th ed) at [8-025].

88 Secondly, the decision in Health World 240 CLR at 597 [22]-[23] does not assist Spirit’s argument. There, French CJ, Gummow, Heydon and Bell JJ remarked on the legislative scheme of the Trade Marks Act being concerned to protect the “integrity” and “purity” of the Register of Trade Marks so as “to ensure that the Register is maintained as an accurate record of remarks which perform their statutory function – to indicate the trade origins of the goods to which it is intended that they be applied” (footnote omitted). Their Honours explained that the Trade Marks Act afforded three means of ensuring that the Register was pure (examination of the application to register by the Registrar, advertising of the decision to accept and the right of a person aggrieved to apply to correct the Register: 240 CLR at 597-598 [24]-[26]). But, their Honours said that this concept of Register being “pure” was used “in a sense that no mark is to be registered unless valid, and no registration of a mark is to continue if it is not valid” (240 CLR at 598 [27]).

89 Here, the Act did not specify any time in which an assignee had to be registered as patentee. Instead, it expressly provided in s 189(1) that a patentee could deal with the patent as its absolute owner, subject only to any rights appearing in the Register to be vested in another person. The Register was prima facie evidence of any particulars registered in it by force of s 195(1). While, s 187 required particulars, including prescribed particulars, relating to a patent to be registered, reg 19.1(2) suggested that the person requesting registration of particulars had to prove its entitlement to the reasonable satisfaction of the Commissioner. And, s 191 created criminal offences for knowingly or recklessly making, or causing to be made, a false entry in the Register. Notably, no offence was created for failure to update an entry with particulars of a subsequent assignment.

90 Of course, the reason why an assignee would seek to update the Register under s 187 and reg 19.1 is not far to seek. Unless and until the assignee did so, its assignor had and continued to enjoy all the rights of being registered as patentee. Furthermore, s 189(3) expressly provided that equities in a patent could be enforced against the patentee except if to do so would prejudice a purchaser in good faith for value. That provision showed that, first, third parties, including unregistered assignees, could enforce equities in relation to the patent against the patentee and, secondly, a purchaser in good faith for value, who, ex hypothesi, was not then registered as patentee, did not lose its rights because the registered patentee created an equity against the patent.

91 The express provisions of the Act were in the teeth of Spirit’s second argument and I reject it. In addition, the Court in Health World 240 CLR at 597 [22] referred to over a century of trade marks jurisprudence beginning with Powell v Birmingham Vinegar Brewery Co Ltd [1894] AC 8 in support of the need for purity of that register. Spirit was unable to cite any case in any jurisdiction in support of its argument in relation to the Register of Patents. There was no suggestion of any intentional or deliberate conduct to mislead by any of the Sackler entities or that any person, including Spirit, had acted to its detriment as a result of the failure to register Mundi Medical as patentee after the 1999 assignment.

92 I am of opinion that Mr Roncalli could give admissible evidence of his knowledge of the sources of his instructions and authority to act on behalf of companies apparently in the Sackler family’s group, including Euro-Celtique and Mundi Medical and the other Sackler entities. I accept that Mr Strassburger had knowledge of the files relating to Euro-Celtique’s dealings in the patent. However, there is no evidence that Euro-Celtique had acted, in relation to the extension, in a way that somehow precluded it from being able to exercise its legal rights as registered patentee to apply for and obtain the extension of the patent.

93 It would be contrary to common sense to find that Euro-Celtique, as one company in a solvent corporate group, in the present circumstances, was acting in some way that was not consistent with its position as bare trustee for Mundi Medical at the time of the extension application. The three 2005 agreements and 2011 deed show that the 1999 assignment had been overlooked accidently by the Sackler entities. But there is no evidence of any improper dealing or lack of bona fides in Euro-Celtique’s conduct. Nor is there any evidence of complaints by any party affected by it. The 2011 deed ratified the earlier dealings after the Sackler entities became aware of the anomaly created by them.

94 Spirit had the onus of proving that Euro-Celtique had no right to make each application or to be granted the extension. Euro-Celtique made the extension application very shortly after the 1999 assignment. At that time when both Euro-Celtique and Mundi Medical were aware of the assignment and that neither of them had applied to enter Mundi Medical in the Register as patentee. Euro-Celtique was the legal owner of the patent and was a bare trustee of it for Mundi Medical. The application for an extension could only have benefitted the person or persons with an interest in the patent.

95 However, after the 1999 assignment, Euro-Celtique could not deal with rights in the patent contrary to Mundi Medical’s beneficial interest, but it could and, I find, did act on Mundi Medical’s behalf in applying for and obtaining the extension. And s 189 of the Act expressly provided for and contemplated that there can be separate, bona fide, legal and equitable owners of a patent. The Act provided that separate legal and equitable interests in a patent were valid and not contrary to any public policy.

96 The obvious inference here is that somehow registration of Mundi Medical as new legal owner of the patent was overlooked after the 1999 assignment was made. But, as the events in 2005 showed, neither Euro-Celtique nor Mundi Medical ever intended that Euro-Celtique could not act as legal owner from the time of the 1999 assignment in taking bona fide steps to protect and enhance the value of the patent. And the position was regularised by the 2011 deed in which Mundi Medical effectively ratified what had occurred in the inter group dealings in 2005 when its position as beneficial owner of the patent was overlooked.